Dakshana Foundation: The Infinite ROI Machine

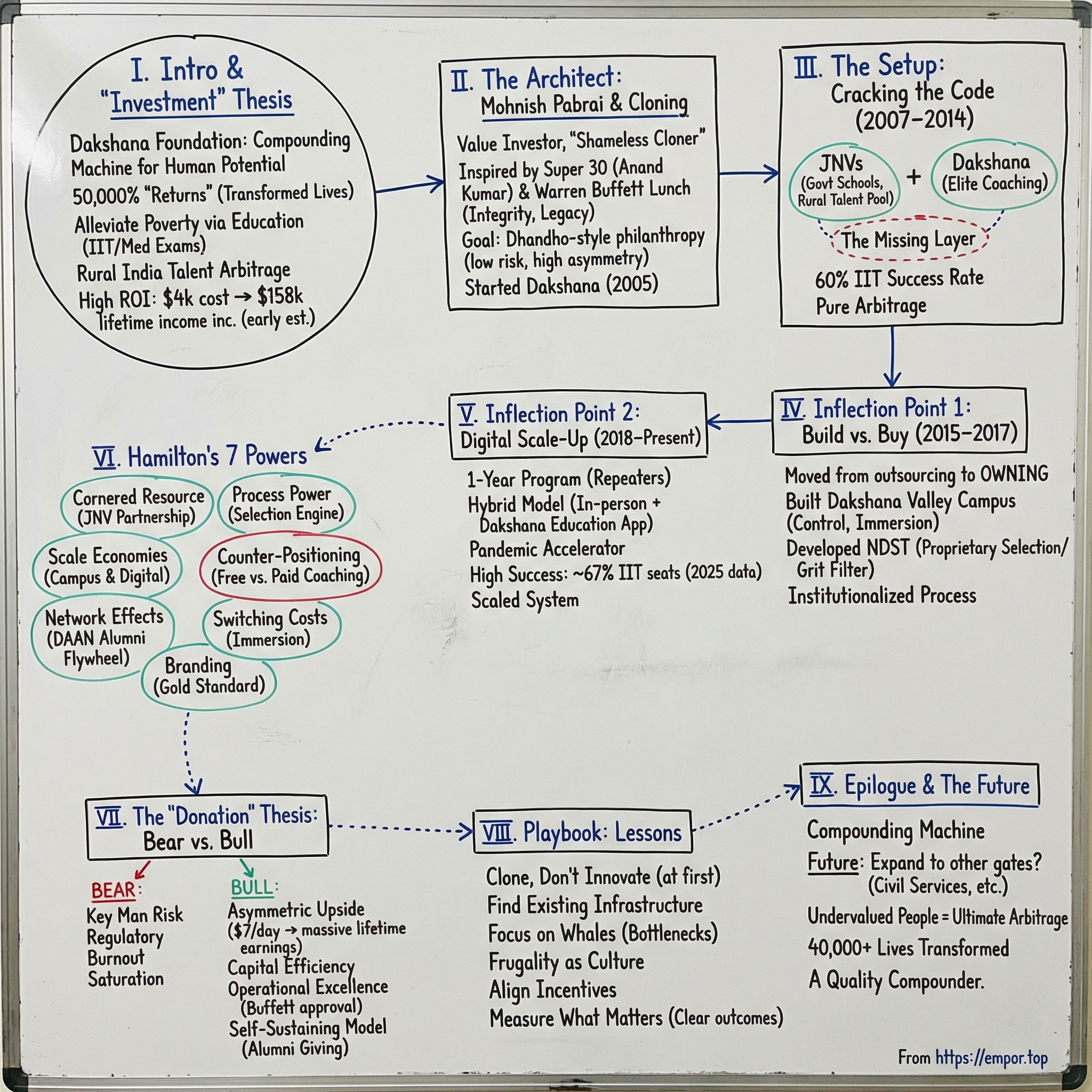

I. Introduction & The "Investment" Thesis

Imagine an “investment” that doesn’t return 10% or 100%, but something closer to 50,000% on capital deployed.

Not in crypto. Not in a moonshot startup. In human potential—systematically unlocked through ruthless selection and intense training.

That’s the operating reality of the Dakshana Foundation. It takes the discipline you’d expect from an elite value investor and applies it to one of the hardest, most stubborn problems on Earth: intergenerational poverty.

If we treated Dakshana like a publicly traded company—call it $DAKSHANA on an imaginary social-impact exchange—it might be one of the most capital-efficient “poverty alleviation engines” ever built. The mission is straightforward: alleviate poverty through education. The method is equally clear: find brilliant, impoverished teenagers—predominantly from rural India—and coach them, for one to two years, to crack India’s top entrance exams for engineering (IIT) and medicine.

The economics are what make you sit up. Early on, Mohnish Pabrai estimated that spending about $4,000 per student could increase that student’s lifetime income by an average of $158,000—nearly a 40x return on a single bet. And Dakshana kept getting more efficient. By 2016, the fully loaded cost per Dakshana Scholar was $3,066.

But even that framing undersells what’s really happening. The transformation isn’t incremental; it’s discontinuous.

Picture a bright kid from a remote village—the child of a farmer earning perhaps $500 a year—who somehow manages to break through the wall of the IIT-JEE, one of the most brutally competitive exams in the world. They go from being invisible to the economy to being recruited into it at the highest level. One cohort went on to receive an average annual salary package of Rs 26.27 lakh—roughly $30,000 a year as a starting point. In a single generation, that can mean a 60x jump over what their parents earned.

So the core question of this story is simple: what if we analyze Dakshana not as a charity trying to raise money, but as a capital allocation engine—obsessed with maximizing social returns per dollar?

That mindset isn’t accidental. Dakshana was built by a value investor who learned directly from Warren Buffett’s worldview: the best returns often come from overlooked assets trading far below intrinsic value, paired with the patience and discipline to concentrate resources where they matter.

And nowhere is the mispricing more obvious than rural India.

Dakshana’s focus is the roughly 970 million people living across India’s 638,000 villages—communities that make up about 72% of the country’s population, yet are largely left out of the country’s economic growth. At the IITs, fewer than 5% of students come from impoverished rural backgrounds.

Talent is everywhere. Opportunity is not.

That gap—the spread between where ability exists and where investment flows—is the ultimate market inefficiency. Dakshana exists to arbitrage it. And the returns are showing up in the only place that matters: the lives on the other side of the trade.

II. The Architect: Mohnish Pabrai & The Art of Cloning

To understand Dakshana, you have to understand the person who built it. Mohnish Pabrai isn’t a typical philanthropist. He’s a value investor at heart—and, by his own proud admission, a “shameless cloner”: someone who studies what works, copies it aggressively, and iterates until the model performs.

Pabrai is an Indian-American businessman, investor, and philanthropist. He was born in Bombay (now Mumbai), India, on June 12, 1964, and grew up in a middle-class family where education mattered and money was often tight. His father ran businesses, failed more than once, and kept going anyway. That resilience left a mark. It taught Mohnish that endurance and discipline aren’t motivational posters; they’re the only durable advantages most people ever get.

He came to the U.S. with ambition and an obsession with how businesses actually work. He worked at Tellabs from 1986 to 1991, first in high-speed data networking and later in international marketing and sales through its international subsidiary. Then, in 1991, he did the most value-investor thing imaginable: he took a small pile of personal capital and made a concentrated bet on himself.

He started an IT consulting and systems integration firm, TransTech, Inc., with about $30,000 from his 401(k) and $70,000 of credit card debt. In 2000, he sold the company to Kurt Salmon Associates for $20 million.

That exit—an enormous return on a very scrappy starting base—funded what had become his real fascination: value investing in the tradition of Benjamin Graham, Warren Buffett, and Charlie Munger. In 1999, he founded the Pabrai Investment Funds, modeled after the Buffett Partnerships. By 2018, those funds had returned 1,204% from 2000, compared to 159% for the S&P 500.

But the moment that matters most for our story didn’t come from a 10-K or a stock screen. It came from a lunch.

In June 2007, Pabrai and Guy Spier won a charity auction for lunch with Warren Buffett, paying $650,100 to the Glide Foundation, which helps the homeless and impoverished get back on their feet. In investing circles, that lunch has become legend—people love to imagine the secret stock tip or the hidden market prophecy.

That’s not what Pabrai got.

The conversation quickly turned to something more fundamental: integrity, incentives, and the difficulty of doing the right thing when it’s unconventional. Buffett emphasized the importance of living by an internal yardstick—making decisions based on what you believe is right, not what gets applause. And he spoke, as he so often does, about giving his fortune away.

Pabrai didn’t leave with a ticker symbol. He left with a framework for legacy.

And because he is Mohnish Pabrai, he didn’t want to just write checks. He wanted to bring the same discipline he used in investing—efficiency, focus, and ROI—to philanthropy. If he was going to deploy capital, he wanted it deployed like capital, with the highest social return per dollar.

The spark came when he read about Anand Kumar and his Super 30 program in Bihar. Kumar, a mathematics educator born on January 1, 1973, started Super 30 in Patna in 2002. The model was audaciously simple: select 30 talented students each year from economically underprivileged families and train them intensely for the IIT entrance exams.

It worked. By 2018, 422 out of 510 Super 30 students had made it into the IITs, and Discovery Channel featured the program in a documentary.

So Pabrai flew to Patna to see it for himself. Picture the contrast: a man who had paid $650,000 for lunch with Warren Buffett walking through the narrow lanes of one of India’s poorest states to find a small building where teenagers were grinding through physics and chemistry without reliable electricity.

He saw something brilliant—and something fragile.

The execution was heroic. The results were undeniable. But the model depended on a singular human engine. Anand Kumar was the system. You couldn’t scale that by writing a bigger check. You couldn’t manufacture another Anand Kumar on demand. Kumar himself had secured admission to Cambridge but couldn’t attend after his father died and finances collapsed; he began teaching mathematics in 1992. His life story was precisely what made him exceptional—and precisely why the model was hard to replicate.

Pabrai’s conclusion was classic Pabrai: if you can’t clone the person, clone the underlying machine.

He went back to first principles and to his own playbook. In The Dhandho Investor, he describes “Dhandho” (pronounced dhun-doe) as endeavors that create wealth—built around low-risk, high-uncertainty bets with asymmetric upside. The tagline says it all: Heads, I win; tails, I don’t lose much.

So what would a Dhandho-style philanthropic bet look like? Something with limited downside, massive potential upside, and a repeatable process—not a one-off act of generosity.

In 2005, Pabrai and his wife, Harina Kapoor, started the Dakshana Foundation. “Dakshana” is a Sanskrit word associated with giving—a gift or offering. The mission was simple and blunt: alleviate poverty. The lever was education. And the commitment was real: they aimed to recycle most of their wealth back into society, starting with giving back about 2%, or roughly $1 million a year.

Pabrai had found his next big bet.

III. The Setup: Cracking the Code (2007–2014)

Once Pabrai had the “what” — take raw talent and turn it into an IIT admit — he needed the “how.” Not a heroic, one-off effort like Super 30, but a system. And the breakthrough came from a hidden asset sitting in plain sight inside India’s government school system: the Jawahar Navodaya Vidyalayas, or JNVs.

JNVs are central government-run schools built for exactly the kind of student Dakshana cared about: bright kids from rural India, often from socially and economically disadvantaged families, who simply don’t have access to accelerated learning and exam coaching. They’re fully residential, co-ed, affiliated with CBSE, and run from Class VI through Class XII. The Ministry of Education funds them, and for the first three years, they’re free for students.

And the scale is enormous. As of December 31, 2022, there were 661 JNVs with roughly 2.88 lakh students enrolled — and about 87% of them were from rural areas.

But the most important part wasn’t the buildings. It was the filter.

The JNV selection process is ruthlessly meritocratic. A student can attempt the entrance test only once, in Class V. In 2021, over 24 lakh students sat for the exam, and just over 47,000 were selected — about a 2% acceptance rate. In other words, long before Dakshana ever showed up, the Government of India had already done the hardest, most expensive work in the whole pipeline: identifying the smartest rural kids at national scale, and putting them in stable, high-quality boarding schools.

The JNVs had the hardware: infrastructure, food, dorms, and a solid academic base. They even had strong outcomes on the standard metrics — in 2022, they ranked at the top among CBSE schools, with pass percentages of 99.71% in 10th grade and 98.93% in 12th.

What they didn’t have was the software.

The IIT-JEE had become its own sport. Regular school curriculum wasn’t enough. To compete, students needed specialized training, top-tier faculty, and relentless practice — the kind of coaching that had evolved into a massive for-profit industry.

And that industry wasn’t built for rural families. Allen’s two-year IIT-JEE coaching fees can range from ₹3.5 lakh to over ₹5 lakh. FIITJEE can run around ₹1.3 to ₹2.8 lakh per year, depending on the program and city. Converted to dollars, it’s thousands per year — completely out of reach for families earning something like $500 annually. The coaching hubs were also in urban centers, especially places like Kota, where students with means could relocate for two years and treat preparation like a full-time job.

That gap — ability without access — was the mispricing. And JNVs made it tradable.

Dakshana’s key insight was that it didn’t need to build a parallel universe of schools and dorms. The government had already built it. Dakshana just had to insert the missing layer: elite coaching, delivered inside the JNV ecosystem.

This is the logic that made Dakshana feel less like a traditional charity and more like a capital allocation hack. Customer acquisition cost was effectively zero. The “customers” — the scholars — were already identified, already enrolled, already housed, and already studying. Dakshana could focus its dollars on the single thing that moved the outcome: high-quality preparation for India’s toughest entrance exams.

Dakshana Scholars are selected from Jawahar Navodaya Vidyalayas and other government schools across India, based on academic performance and Dakshana’s own testing process. After Class 10 or Class 12, they receive specialized coaching to target elite outcomes.

Over time, this partnership model showed what it could look like in practice. Dakshana’s two-year coaching program currently operates at two JNV campuses: JNV Bengaluru Urban (Karnataka) and JNV Pune (Maharashtra). The first Dakshana-Navodaya Centre of Excellence began at JNV Bengaluru Urban in 2016 — positioned as a flagship example of a private-public partnership between Dakshana and the Government of India.

But back in the 2007–2014 window, the story was simpler: does the machine work?

The early cohorts delivered the proof of concept. Since Dakshana began operations in 2007, the IITs have accepted more than 1,539 Dakshana Scholars out of a total of 2,575 — about a 60% success rate.

Sit with that for a second. IIT admissions are famously brutal, with acceptance rates often discussed around 1% overall. Dakshana was taking kids who were almost never represented at the IITs — rural, low-income, no access to premium coaching — and getting roughly six out of ten across the finish line.

That’s why Dakshana’s true north metric was never “students served.” It was wealth created per dollar invested.

When a student from a farming family earning around $500 a year breaks into an IIT, they enter a labor market where an IIT engineer’s typical starting salary is often cited in the range of ₹8 to ₹15 lakh per year — roughly $10,000 to $18,000 as a starting point, with a trajectory that can go much higher. That one outcome can permanently change a family’s economic future in a way that almost nothing else can.

So the math started to look almost unfair. Spend a few thousand dollars on a scholar. Create hundreds of thousands of dollars in additional lifetime earnings. Lift an entire household — sometimes an entire extended family — onto a different economic plane. And unlike most philanthropy, the result was clean and measurable: either the student got into IIT or they didn’t.

For a value investor trained to hunt for assets priced far below intrinsic value, this was the purest form of arbitrage: rural genius, systematically overlooked, waiting to be unlocked.

IV. Inflection Point 1: The Build vs. Buy Decision (2015–2017)

By the mid-2010s, Dakshana had proven the model worked. The question wasn’t whether rural talent could win. It was whether Dakshana could scale without losing the thing that made it work in the first place: quality.

In the early years, Dakshana leaned on third-party coaching partners to teach inside JNV campuses. On paper, it was elegant: stay lean, outsource the messy parts, focus on selection and funding. In reality, it introduced a familiar scaling problem. The incentives weren’t perfectly aligned. Quality control was hard. And the cost structure wasn’t where a value investor would want it.

So Pabrai faced a decision that every organization hits eventually: remain asset-light—basically a check writer coordinating vendors—or become an operator and take control of the core product.

The value-investor instinct here is almost automatic. If you’ve found something truly extraordinary, you don’t outsource the engine. You own it.

That’s how Dakshana made its big “build” bet. In 2014, it purchased a 109-acre property in Ananda Valley, India, to develop what would become Dakshana Valley. While Dakshana continued running coaching across seven locations throughout India, this campus became the foundation’s purpose-built home base. It accepted 250 scholars in 2017, and when fully built out, it is planned to accommodate more than 2,000 scholars.

Dakshana Valley sits at Kadus Village in Maharashtra, about 60 kilometers from Pune. The campus stretches across a valley surrounded by hills, with five lakes, in a zero-pollution area. It’s beautiful, yes—but the beauty isn’t the point. The point is control.

This wasn’t just “a campus.” It was designed like a focus machine. Total immersion. Faculty living on-site. No distractions. The idea was simple: if these kids were going to go toe-to-toe with India’s best-prepared students, Dakshana had to give them an environment engineered for one thing—work.

We own the 109-acre Dakshana Valley campus free and clear. The cost basis of Dakshana Valley and all improvements is over $14 million. With over $41 million in assets and virtually no liabilities, Dakshana is in the best financial shape it has ever been.

As operations ramped, the numbers started to reflect the strategy. At the time, Dakshana Valley could house 414 boys and 192 girls, with plans to expand capacity to 2,600 scholars. Owning the campus also unlocked classic scale economies: as more beds get filled and facilities get used more intensively, the cost per scholar comes down. A fixed-cost base becomes an advantage—as long as you can keep it utilized.

At the same time, Dakshana built what might be its most underrated asset: its own selection engine.

The foundation developed a proprietary exam called the NDST, the National Dakshana Selection Test. Dakshana Scholars—gifted students from Jawahar Navodaya Vidyalayas and other government schools—were selected for intensive coaching after Class 10 and Class 12 based on their academic record and NDST performance.

The NDST wasn’t just an IQ filter. It was a grit filter. Dakshana wasn’t looking for students who could do well on one test; it was looking for students who could survive the grind—thousands of hours of focused preparation, day after day, with no shortcuts.

In other words, Dakshana was no longer just running a program. It was building an institution: owned infrastructure, in-house faculty, and a proprietary selection mechanism that let it control every critical step of the pipeline—from identifying talent to converting it into IIT and medical admissions.

V. Inflection Point 2: The Digital Scale-Up & The One-Year Program (2018–Present)

The two-year JNV program worked—but it left a painful amount of talent on the table.

Every year, there were students who did everything right, finished Class 12, took their shot at IIT or medical entrance exams, and missed by a hair. Not because they weren’t capable, but because they didn’t have enough runway. These “repeaters” were a huge, underpriced pool: proven academic ability, proven work ethic, and one more year could change the outcome.

Dakshana’s answer was the 1-year coaching program at Dakshana Valley near Pune, designed for brilliant but impoverished students from government and government-aided schools after Class 12 (Science). The structure is simple and brutal in the best way: one year of focused preparation, with experienced faculty, and with food and accommodation covered so the student can do the one thing their family could never afford to buy them—time.

By Dakshana’s own reporting, scholars in this 1-year program have produced strong results in JEE Advanced since 2015, and in NEET since 2017.

Strategically, this changed the game. The foundation was no longer limited to the two-year pipeline inside the JNV network. It could now pull from a far wider set of government schools—expanding its addressable market overnight.

Then COVID-19 hit, and what could have been an existential threat became an accelerant.

As lockdowns shut campuses and sent students back to their villages, Dakshana didn’t stop. It leaned into digital delivery—shipping tablets and building out the infrastructure to keep classes going remotely. Out of that scramble came a real product: Dakshana Education, an online testing and learning platform where students can attend live classes, access video content and study material, and keep progressing even when the physical classroom disappears.

The pandemic forced all of Indian education to confront the digital divide. For Dakshana, it also revealed a powerful scaling law: once great teaching is captured on video and delivered through an app, distribution gets cheap. Really cheap. The marginal cost of reaching the next student starts to collapse.

What emerged was a hybrid model: in-person intensity where it matters, and digital lectures and testing that can be broadcast across geographies. The best of both worlds—high control, but now with leverage.

The outcomes have stayed startling. Dakshana reported that in the JEE Advanced 2025 results, 329 of 489 scholars—about 67%—secured IIT seats. Using 2024 data, it also reported 428 scholars, or 88%, qualifying for IIT+NIT.

Put that next to the national baseline—where the odds are often framed around 1%—and the contrast becomes almost absurd. These are students from some of India’s poorest villages, competing against urban peers who have spent years in premium coaching ecosystems, and winning at industrial scale.

Since beginning operations in 2007, Dakshana says it has inducted more than 9,000 students. More than 3,700 scholars have cracked JEE Advanced and secured IIT admissions, while many others cleared AIEEE or JEE Main and went on to institutions like the NITs and other leading engineering and science colleges. In their summary, the headline is simple: roughly one in two Dakshana Scholars has cracked the IIT entrance examination.

At this point, Dakshana isn’t a clever program anymore. It’s a scaled system: multiple campuses, thousands of scholars, and—most importantly—an alumni base large enough to begin compounding the mission forward.

VI. Hamilton's 7 Powers & Strategic Analysis

If Dakshana were a for-profit business, how would it look through Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers lens—the framework for identifying durable competitive advantage?

Cornered Resource: Dakshana’s relationship with the JNV network is the kind of asset you can’t just buy. The foundation has spent nearly two decades building credibility inside a government system that doesn’t easily open itself to outside players. The partnership has become a real proof point for what private-public collaboration between Dakshana and the Government of India can produce. And the practical result is a moat: no other private organization has comparable access to India’s pipeline of academically gifted rural students.

Process Power: The selection system is the crown jewel. Dakshana Scholars come from Jawahar Navodaya Vidyalayas and other government schools across India, chosen for intensive coaching after Class 10 and Class 12 based on academic performance and Dakshana’s proprietary testing. But the real magic isn’t just picking “smart.” It’s picking “smart plus relentless.” Over thousands of students, Dakshana has built institutional knowledge about who can handle the grind—day after day, for a year or two—without breaking.

Scale Economies: Owning its campus and running its own programs has helped keep costs low, and the economics get better as utilization rises. Dakshana reported overhead per scholar of $416, and a bundled per-scholar cost (direct costs, overhead, and construction) of $2,736. As more beds and classrooms get used, fixed costs spread thinner. And on the digital side, the scaling is even more extreme: once the platform and content exist, adding another student is close to zero marginal cost.

Counter-Positioning: This is where Dakshana becomes almost impossible for incumbents to copy. Traditional coaching centers like Allen in Kota charge ₹3.5 lakh to over ₹5 lakh for a two-year program—thousands of dollars a year. Dakshana charges nothing. But the real wedge is that you can’t pay your way in. Admission is earned through ability and need. That eliminates the selection bias baked into for-profit coaching, where families with money can purchase a shot for almost any student. Commercial incumbents can’t “respond” by going free without destroying their own business model, because tuition is the business.

Network Effects: The alumni flywheel is real, and it’s getting stronger. Formally launched in June 2011, the Dakshana Alumni Network (DAAN) includes scholars who received coaching and are now in college or working. Every scholar becomes a DAAN member after appearing for the IIT or medical entrance exam. DAAN exists first to help its own members succeed through college and early career—and that community also supports Dakshana’s mission. By 2023, DAAN was reported as 7,271+ strong. Early scholars are now at places like Google, Microsoft, Amazon, and Goldman Sachs. They mentor. They volunteer. They donate back. The long-term compounding story is simple: the beneficiary of aid today becomes the donor tomorrow.

Switching Costs: Not in the classic enterprise-software sense, but there’s an analog. Once a student is accepted into Dakshana, leaving carries an enormous opportunity cost. The program is built around total immersion, and walking away means giving up a rare, concentrated shot at a life-changing outcome.

Branding: Inside the JNV ecosystem, Dakshana has become the gold standard. Results have turned into reputation, and reputation turns into deal flow: more top students want in than Dakshana can accept. In a talent-driven system, that kind of brand isn’t marketing—it’s another moat.

VII. The "Donation" Thesis: Bear vs. Bull

Every investment thesis deserves a real bear case. Dakshana is extraordinary, but it isn’t magic. If $DAKSHANA were a stock, here’s what the downside and upside would look like.

The Bear Case

Key Man Risk: Dakshana is inseparable from the worldview of Mohnish and Harina Pabrai. The endowment funds are managed by Mohnish Pabrai and invested in equities in a highly concentrated way. That’s been a feature, not a bug—but it also means succession planning matters. Founder-led organizations can stumble when the founder steps back, especially when capital allocation and culture are both part of the “product.”

Regulatory Risk: Dakshana’s model leans heavily on the continued health and accessibility of the JNV ecosystem—and on the stability of India’s entrance-exam structure. Changes in education policy, reforms to JEE or NEET, or shifting government attitudes toward private-public partnerships could materially disrupt how Dakshana operates. These exams are politically sensitive, and the rules of the game can change.

The Burnout Factor: The intensity is the point. Dakshana is built around immersion, repetition, and pressure-tested performance. But these are teenagers, many carrying enormous family expectations on their shoulders. As mental health awareness has risen across Indian education, Dakshana has had to adapt its approach to student wellbeing—and it will need to keep doing so if it wants the machine to stay sustainable.

Market Saturation: There’s a long-term macro question: if pathways into elite engineering become more accessible—through Dakshana and others—does the earnings premium of an IIT degree compress? If exclusivity declines, the purely financial “multiple” on the intervention could come down, even if the social value remains high.

The Bull Case

Asymmetric Upside: The pitch is simple: fully support a scholar for about $7 a day—around $210 a month for 12 months, or roughly $2,500 a year. You can make it recurring and be billed monthly during the sponsorship period. In exchange, you’re backing a student whose lifetime earnings can rise by hundreds of thousands of dollars. In impact terms, it’s the cleanest kind of bet: small, capped cost; potentially massive upside.

And the prize at the end is real. In 2024, the Class of 2024 at IIT Kanpur received 989 job offers, including 22 overseas offers, in the first round of placements. The cohort reported an average annual salary package of Rs 26.27 lakh. At the extreme end of the distribution, the highest IIT placement package in 2024–25 reached ₹3.67 crore at IIT Bombay.

Capital Efficiency: Dakshana states that outside donor funds are used only for the direct Dakshana Scholar program, and that foundation overhead expenses are not paid from these funds. The promise is straightforward: money in goes to scholars, not bureaucracy.

Operational Excellence: Dakshana has been run with an operator mindset. Its management team didn’t come up through the not-for-profit world; they came from business, or from long careers in the Education & Training sector. The intent is to run Dakshana like a business, not a charity.

And there’s a seal of approval that’s hard to beat. Buffett wrote: I remain incredibly impressed by what you have done, are doing and will do at Dakshana. It is simply terrific – far more impressive than what business titans, investment gurus and famous politicians ever accomplish. I'm glad my annual report doesn't get compared to the Dakshana annual report. It's an honour even to be quoted in it.

Self-Sustaining Model: The endgame is compounding. As the alumni base matures and more graduates reach stable, high-earning careers, Dakshana can become increasingly funded by the people it helped—turning the program into a flywheel that pays its own forward.

KPIs to Track

If you’re evaluating Dakshana’s ongoing performance, three metrics matter most:

-

IIT Conversion Rate: The percentage of Dakshana scholars who secure IIT admission. This is the core output that drives most of the measurable, life-changing economic impact.

-

Cost per Successful Outcome: Total expenditure divided by the number of scholars admitted to IITs. This captures both operational efficiency and how well the selection engine is working.

-

Alumni Giving Rate: The percentage of employed alumni contributing back to Dakshana. This is the leading indicator for whether the compounding engine is becoming self-sustaining.

VIII. Playbook: Lessons for Builders & Investors

So what do you take from Dakshana if you’re building a company, running a foundation, or allocating capital?

Clone, Don’t Innovate (At First): Pabrai didn’t invent the idea of coaching underprivileged kids for IIT. He borrowed a proven template—Super 30—then did what great operators do: he systematized it, tightened the feedback loops, and scaled it. The lesson is deceptively simple: starting with a working model beats starting with a blank sheet. In Dhandho terms, you stack the odds by copying what’s already validated and then improving the machine.

Find the Existing Infrastructure: Dakshana didn’t waste years and capital rebuilding what already existed. The government had already solved the hardest parts at scale—finding rural talent, housing students, and earning the trust of families. Dakshana slotted in the missing piece: elite exam preparation. For builders, this is the play: find a platform that already works and add the one capability that changes the outcome.

Focus on the Whales: Dakshana isn’t trying to fix every problem in a student’s life. It’s optimizing for one decisive bottleneck: cracking the exam that unlocks the whole trajectory. It’s not “holistic.” It’s targeted. And that focus is the reason the ROI looks so outsized.

Frugality as Culture: Dakshana Valley’s calm, low-distraction environment isn’t a luxury; it’s part of the product. The campus is built to reduce noise—literal and metaphorical—so scholars can do deep work. And the foundation keeps costs low through disciplined operations, including rainwater recycling and solar power. It’s not just thrift. It’s teaching: resources are scarce, so you allocate them like they matter.

Align Incentives Relentlessly: The student wants the seat. The family needs the breakthrough. The foundation is built around that one mission. When incentives line up this cleanly, you don’t need elaborate motivation systems—you get extraordinary effort because the outcome is existential.

Measure What Matters: A lot of charity drifts into vague reporting because the outputs are hard to define. Dakshana’s isn’t. Either a scholar clears the entrance exam or they don’t. That clarity forces accountability, makes iteration easier, and gives donors something rare in the social sector: a scoreboard everyone can agree on.

IX. Epilogue & The Future

So what comes next for Dakshana?

It has already proven the core bet: take brilliant, underserved rural students, give them world-class preparation for IIT-JEE, and the results follow. The obvious question is whether the same machine can be pointed at other gates that control social mobility in India—civil services, law, or medicine beyond the NEET pathway.

Because the underlying insight isn’t “IIT is special.” It’s that India’s government school system is full of extraordinary hidden talent, and that the missing piece is often specialized coaching—delivered with intensity, accountability, and at a cost structure that makes commercial alternatives look absurd.

So far, Pabrai has secured investments totalling ₹130 crore for his foundation, transforming nearly 40,000 lives forever.

Mohnish Pabrai likes to say he’s a “shameless cloner” with no original ideas. But with Dakshana, he has created something that feels genuinely new: a systematic poverty-eradication engine, run with the cold-eyed discipline of a value investor allocating capital toward human potential.

The proof is in the foundation’s annual letters. They read less like charity updates and more like owner-operator memos: a relentless focus on outcomes, clear accounting of what worked and what didn’t, and a level of transparency that would embarrass most public companies.

If $DAKSHANA traded on a social-impact exchange, it would screen like a classic quality compounder: a defensible moat, unusually strong management, efficient capital allocation, and an enormous runway.

And the dividend isn’t paid in cash. It’s paid in outcomes you can picture: the child of a farmer who becomes a software engineer at Google; the first doctor from a village that has never sent anyone to medical school; the slow, steady expansion of opportunity across rural India—one admission letter at a time.

If you’re trying to deploy philanthropic capital with maximum leverage, Dakshana has become the benchmark: a proven model, disciplined execution, and a scoreboard that doesn’t let anyone hide.

Because the ultimate arbitrage isn’t finding undervalued stocks.

It’s finding undervalued people.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music