CoreCivic Inc.: The Private Prison Paradox

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

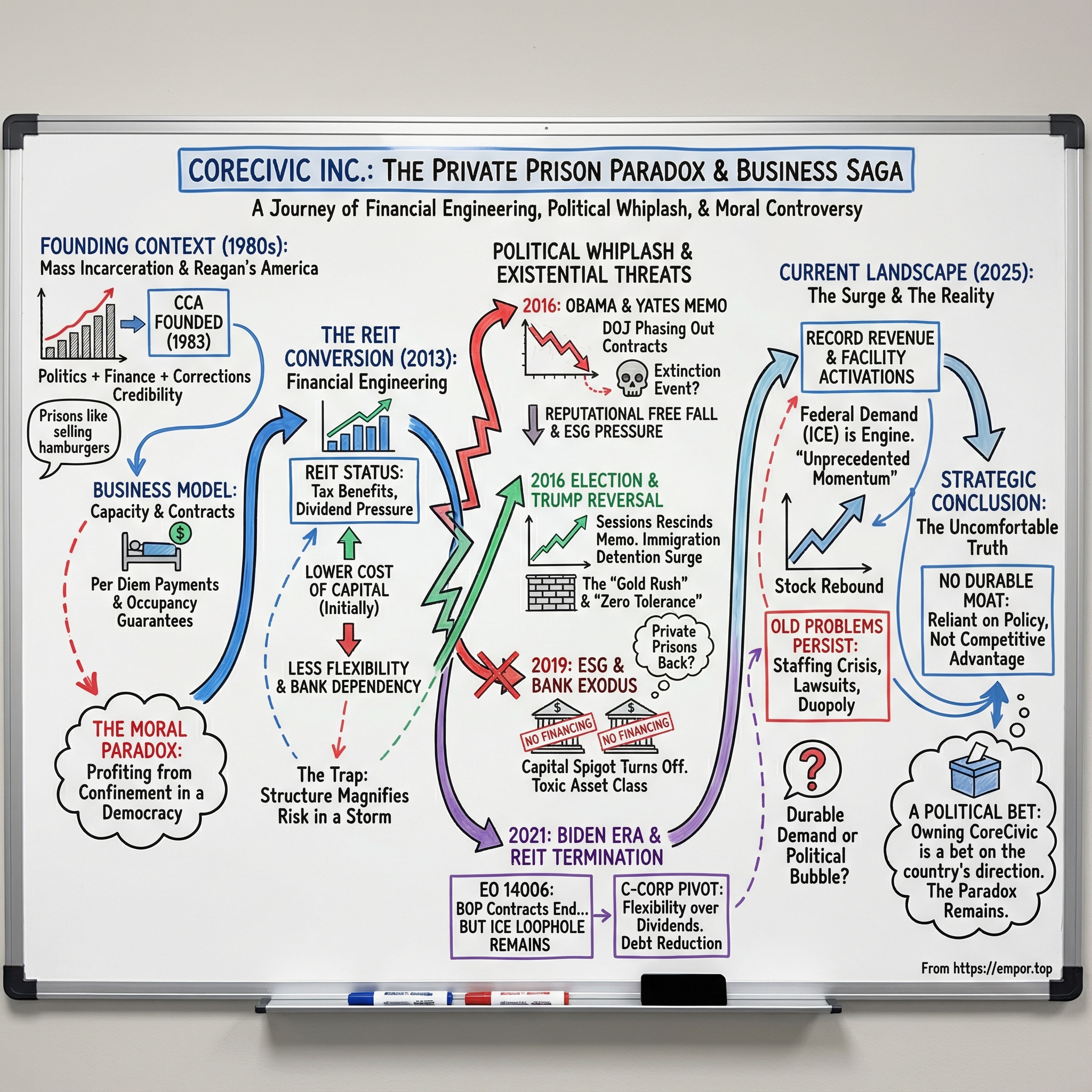

Picture this: it’s 2016. You’re an institutional investor watching a Bloomberg screen as Corrections Corporation of America drops 35% in a single day. The Obama administration has just signaled the beginning of the end for federal private prison contracts, and whatever you thought you owned suddenly looks unownable.

Now jump forward four months. Election night hits, and that same stock more than doubles essentially overnight. Same company, same assets, same business. Different political weather.

That’s CoreCivic: one of the most politically volatile, morally contested, and strategically revealing companies in American public markets.

In 2024, CoreCivic reported about $2 billion in revenue and $68.9 million in net income. It’s one of the largest for-profit prison, jail, and detention contractors in the United States, and the country’s largest owner of partnership correctional, detention, and residential reentry facilities. But the corporate description doesn’t capture the thing you can’t ignore: this is a business built around human confinement. It earns billions by housing people the government wants detained, but often can’t—or won’t—house on its own.

That leads to the central paradox, and it’s both simple and unsettling: how does a company profit from incarceration in a democracy? How does it live in the tension between shareholder returns and the moral gravity of depriving people of liberty? And for investors, the practical version of the question is even sharper: can a business this dependent on politics ever be a sound long-term bet?

As of Q3 2025, CoreCivic reported revenue up 18.1% year-over-year, driven by what it called building momentum and active facility activations. Management described the moment as “unprecedented,” pointing to a strong close to 2024 and what it sees as accelerating demand from federal, state, and local partners. The whiplash is the point: today’s optimism comes after years of existential threats, reputational free fall, and financial engineering that, at times, looked like a lifeline—and at other times looked like a trap.

This story matters right now because the forces around CoreCivic are pulling in opposite directions. Criminal justice reform advocates continue pushing to end private prisons. ESG investors have largely exited. And yet immigration enforcement demand has surged back, filling beds and driving revenue. CoreCivic sits at the crossroads of America’s loudest arguments: immigration, mass incarceration, racial justice, the privatization of public services, and whether some markets should exist at all.

So here’s where we’re going. We’ll trace how this company was born, how it scaled, how it nearly broke, and how it reinvented itself—more than once. We’ll look at the financial structure decisions that powered growth and later became liabilities. We’ll pressure-test the business using real strategic frameworks: does CoreCivic have any durable edge, or is it simply a contractor living on borrowed political time? And we’ll confront the uncomfortable truth at the center of it all: owning CoreCivic isn’t just a bet on fundamentals. It’s a bet on the direction of the country.

II. The Founding Context: Mass Incarceration & Reagan's America

To understand CoreCivic, you have to start with the world that made it possible. The early 1980s weren’t just a change in crime policy; they were a structural shift in how America chose to punish. And that shift created a new kind of customer: governments that suddenly needed prison beds the way cities need water—immediately, continuously, and at scale.

Incarceration began climbing sharply in the 1980s, driven by the War on Drugs and a new era of strict sentencing. What started with President Nixon’s “war on drugs” expanded dramatically under President Reagan. Mandatory minimums shrank judicial discretion. Three-strikes laws kept people locked up for decades. Prison populations swelled, and the pressure didn’t ease for years. By 2013, the federal prison population had grown by roughly 800% from 1980 levels.

States found themselves in a trap. They were building prisons as fast as they could, then filling them faster than they could pour concrete. Capital budgets couldn’t keep up. Operating costs ballooned. And politicians who’d campaigned on being “tough on crime” ran into an uncomfortable operational detail: toughness is expensive.

That’s the gap entrepreneurs stepped into.

Corrections Corporation of America was founded in Nashville, Tennessee, on January 28, 1983, by Thomas W. Beasley, Robert Crants, and T. Don Hutto. The team was not an accident. Beasley was chairman of the Tennessee Republican Party, Crants was a CFO at a Nashville real estate company, and Hutto was president-elect of the American Correctional Association. Politics, finance, and corrections credibility—packaged together from day one.

The company’s early orbit mattered, too. Maurice Sigler, former chairman of the U.S. Board of Parole, served on the board. The initial investment came from Jack C. Massey, the co-founder of Hospital Corporation of America. Vanderbilt University Law School—where Beasley earned his JD—was also an early investor before the IPO. The founders secured $500,000 in initial funding from the Massey Burch Investment Group, backed by Massey, specifically to tackle overcrowding through for-profit operations.

The Hospital Corporation of America comparison wasn’t subtle; it was the blueprint. If healthcare could be privatized, scaled, and made highly profitable, why not corrections? Beasley and his partners framed prison operations like any other service business. In 1988, Beasley was quoted saying prisons could be sold “like you were selling cars, or real estate, or hamburgers.”

CCA’s early focus wasn’t just state prisons. The company pursued a joint venture with the Federal Bureau of Prisons and the Immigration and Naturalization Service to house detained immigrants, and in January 1984 it opened its first facility in Texas inside an old motel complex. It’s widely recognized as the first privately operated correctional institution in the United States.

The sales pitch to government buyers was almost too clean.

CCA could build faster because it wasn’t bound by public procurement. It could operate cheaper because it wasn’t tied to civil service rules. And the political magic trick was that it could do it off the government’s balance sheet: the capital spend sat with CCA, not the state. Elected officials could expand capacity without visibly raising taxes or issuing new public debt.

Even so, the early years weren’t a straight line to success. CCA went public on NASDAQ in 1986 at $9 per share, raising $18 million to fund growth. The stock quickly fell, sliding to $3 the following year. The company kept going anyway, and in October 1987 it landed its first state-level contract.

None of this happens without the broader mood of the era. Privatization wasn’t a fringe idea in Reagan’s America; it was the prevailing logic. If airlines, utilities, and telecom could be pushed toward market models, why would prisons be treated as sacred ground? The deeper question—whether incarceration is so fundamentally governmental that it shouldn’t be outsourced—was barely asked at the time.

And that’s the first key insight for investors: CoreCivic wasn’t born from a timeless market need. It was born from a specific political moment, with a specific ideological tailwind. Its survival depends not only on crime rates or cost per bed, but on whether there remains enough political consensus that outsourcing incarceration is acceptable.

As we’ll see, that consensus never stopped shifting.

III. The REIT Conversion & Financial Engineering

If the 1980s created CCA and the 1990s proved the model could scale, then 2012 and 2013 marked its boldest act of financial engineering—one that would later look less like a masterstroke and more like a loaded wager.

By the early 2010s, the company had become a corrections giant. CCA was the nation’s largest owner and operator of partnership correctional and detention facilities and one of the largest prison operators in the United States, behind only the federal government and three states. It operated 67 facilities, including 47 it owned, with a total design capacity of roughly 92,000 beds across 20 states and the District of Columbia.

But the easy growth was fading. Margins were under pressure. And the company needed a way to boost shareholder returns without necessarily building its way into even more controversy.

The answer, it decided, was three letters: REIT.

In May 2012, CCA announced it was assessing the feasibility of converting into a Real Estate Investment Trust. The official language was classic boardroom prudence: the company was evaluating how best to allocate capital resources and deliver long-term value to stockholders. The real strategic move was simpler: change what kind of company Wall Street thought this was.

The pitch was elegantly reductive. Prisons are buildings. Buildings are real estate. Real estate throws off predictable cash flow. And REITs are designed to hold real estate and pass most of the income straight through to shareholders.

CCA launched what it called the “REIT Project” to evaluate the potential benefits of a structure that could increase long-term shareholder value, create a more tax-efficient setup with higher cash flow, and potentially lower the cost of capital—while still keeping access to funding for future growth.

In December 2012, the board unanimously authorized the company to elect REIT status for the taxable year starting January 1, 2013. The decision came after CCA received a favorable IRS Private Letter Ruling and completed an internal reorganization to make the structure work.

The upside was immediate and obvious. A REIT can deduct dividends paid to shareholders from its corporate taxable income. In practice, that means the tax burden shifts away from the company and onto investors receiving dividends. CCA expected a one-time income tax benefit in 2013 of $115 million to $135 million, tied to reversing certain deferred tax liabilities.

Just as important, the REIT label promised a different investor base. REIT investors tend to like stable, dividend-heavy cash flow. If CCA could be valued like a real estate company that happened to lease and manage specialized facilities, rather than a prison company that happened to own land and concrete, it might win more patient shareholders—and potentially cheaper capital.

But this structure came with a hard constraint: to keep REIT status, the company generally had to pay out at least 90% of its tax-basis net income as dividends every year. That’s great if you want to force discipline and reward shareholders. It’s much less great if you want flexibility—to retain earnings, build a cash buffer, or deleverage when conditions turn.

And conditions turning mattered more here than in almost any other “real estate” category.

CCA and GEO Group both used REIT structures that exempted them from corporate income taxes, and that tax advantage helped fuel industry expansion. But REIT rules also meant a lot of cash went out the door to shareholders—money that otherwise might have sat on the balance sheet as a cushion.

That created a quiet dependency: if you’re required to pay out so much of what you earn, and you still want to grow—or even just stay resilient—you need outside financing. Short-term loans. Lines of credit. Bank relationships. Wall Street, in other words, becomes less a partner and more a choke point.

In the early years, it worked. From 2013 through 2015, CoreCivic—still called CCA—generated steady cash flows and paid reliable dividends. Politically, the era still carried the inertia of decades of tough-on-crime policy, with the 1994 Clinton crime bill setting the tone. There was little appetite in either party for looking “soft,” and the business benefitted from that stability.

But the deal had a dark symmetry. The same mechanics that amplified returns in calm waters would magnify danger in a storm.

Mandatory payouts meant less cushion. Reliance on lenders meant financing could disappear precisely when reputational pressure spiked. And calling the business “real estate” didn’t change the underlying truth: these weren’t apartments or warehouses. They were incarceration facilities, and their revenue depended on government policy and public tolerance.

The REIT conversion is the cleanest example of a lesson CoreCivic keeps teaching the market: financial engineering can improve the spreadsheet, but it can’t change what the business is. When politics shifts, the structure doesn’t protect you—it can trap you.

IV. The Business Model Deep Dive

To understand how CoreCivic makes money, you have to strip away the positioning and look at the mechanics. At its core, this is a capacity business: beds, staffing, and contracts. But it’s also a relationship business, because the customers aren’t consumers. They’re governments. And there aren’t many of them.

CoreCivic operates under federal, state, and county contracts using three basic structures. First, it owns and runs facilities itself. Second, it runs facilities that the government owns under manage-only contracts. Third, it leases some of its facilities to third parties for government use.

That first model—ownership—is the one with the most leverage. As of 2023, CoreCivic operated 43 prisons and jails, 39 of which it owned, with capacity for about 65,000 beds. That makes it the largest private owner of prisons and jails in the U.S., including immigration detention facilities. Economically, owning a facility isn’t just an operations business; it’s also a real estate business. Managing government-owned facilities, by contrast, is closer to a pure service contract: lower upside, but also less capital at risk.

Most of the revenue comes in a form that’s both intuitive and loaded: per diem payments. Governments pay a daily rate for each person housed. That rate varies by facility and contract terms—security level, medical care provisions, population requirements, and sometimes occupancy guarantees.

The math is simple. More people detained means more revenue. And that’s the uncomfortable part critics keep coming back to: a model where growth can align with more incarceration. CoreCivic has acknowledged this policy dependence directly. In a 2014 report, it warned that demand could decline with “relaxation of enforcement efforts,” more lenient sentencing and parole standards, or the decriminalization of certain conduct.

If you’re looking for the biggest risk in the business, you don’t have to dig far: customer concentration. In 2023, CoreCivic generated 52% of its annual revenue from federal prison and immigration authorities—primarily U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the U.S. Marshals Service, and the Federal Bureau of Prisons. The rest came mostly from state and local agencies. When more than half your revenue ultimately traces back to Washington, your real exposure isn’t competition. It’s elections.

Then there’s the contractual feature that has done as much reputational damage as anything else: occupancy guarantees. Many private prison contracts require governments to keep beds filled—often around 90%—or pay penalties anyway. Advocacy group In the Public Interest reviewed 62 contracts covering 77 county and state-level facilities and found that 65% included occupancy requirements between 80% and 100%, with many around 90%.

One example comes from Florida’s Bay Correctional Facility, where the contract clause states: “Regardless of the number of inmates incarcerated at the Facility, CONTRACTOR is guaranteed an amount equal to 90% occupancy times the 90% Per Diem Rate subject to legislative appropriations.”

The critique is straightforward, and hard to shake. As the study’s authors put it: “These contract clauses incentivize keeping prison beds filled,” which can run directly against state goals of reducing prison populations and increasing rehabilitation.

On the cost side, the business is dominated by labor. In 2024, salaries and benefits made up about 63% of CoreCivic’s operating expenses. Corrections officers are the largest line item, and staffing isn’t just a financial variable—it determines safety, quality, and whether the company can meet contract requirements at all.

As of December 31, 2024, CoreCivic employed 11,649 full- and part-time workers across its correctional, detention, and residential reentry facilities. That includes correctional officers earning an average starting wage of $23.23 per hour, plus support roles in healthcare, food services, and facility operations. In 2024, the company received more than 94,000 job applications and spent $7.2 million on recruitment and training initiatives.

Operationally, CoreCivic leans on standardization and speed. One of its most consequential tactics is building “spec” facilities—designed and developed before a specific contract is in hand—so it can move fast when governments suddenly need capacity. It’s risky, because a facility without a contract is an expensive empty asset. But when demand spikes, having beds ready can be the difference between winning the deal and watching it go to someone else.

So why do governments keep using private prisons, even as the controversy grows louder? The answer is less ideological than it sounds: capital constraints, budget flexibility, and speed. Building a prison takes huge upfront spending, political approvals, and years of lead time. Private operators can finance construction themselves and turn what would’ve been a big, visible capital project into an operating expense. In practical terms, officials can expand capacity without issuing new public debt or raising taxes in a way voters immediately feel.

The investor takeaway is stark. CoreCivic’s fundamentals don’t hinge on typical market forces. They hinge on policy choices: incarceration and sentencing, immigration enforcement, and the budget pressures of government agencies. Those are political variables. And in this business, politics isn’t background noise. It’s the operating system.

V. The Obama-Era Inflection Point

The morning of August 18, 2016 started like a normal day for CoreCivic investors. By the afternoon, the thesis had shattered.

Deputy Attorney General Sally Yates issued a memo to the acting director of the Bureau of Prisons with a blunt directive: as private prison contracts came up for renewal, the Bureau should decline to renew them or sharply reduce their scope. “This is the first step in the process of reducing—and ultimately ending—our use of privately operated prisons.”

Yates didn’t frame it as politics. She framed it as performance. Private prisons, she wrote, “compare poorly to our own Bureau facilities,” citing a 2016 report by the Justice Department’s inspector general. The audit looked at 14 privately operated prisons and concluded they “simply do not provide the same level of correctional services, programs, and resources” as publicly run facilities. On safety, it was even more damning: the private facilities “incurred more safety and security incidents per capita than comparable Bureau of Prisons institutions.”

Wall Street heard one thing: the biggest customer was walking away.

The selloff was immediate and violent. By mid-afternoon, both major private prison stocks were down close to 40%, with trading halted repeatedly as volatility spiked and sell orders flooded in.

This wasn’t just bad press. It felt like an extinction event. The federal government was CoreCivic’s largest single customer, and the memo wasn’t only about revenue—it threatened legitimacy. If the Bureau of Prisons was saying, in writing, that private operators were worse on quality and safety, it wasn’t hard to imagine states following the same template.

And the memo landed on dry tinder.

That same year, journalist Shane Bauer went undercover as a guard at Winn Correctional Center in Louisiana, a facility run by Corrections Corporation of America. His Mother Jones reporting described rampant violence, inadequate medical and mental healthcare, and staff training that didn’t come close to what the job demanded. He later expanded the story in his 2018 book, American Prison.

There were legal blows, too. In May 2016, the company was found in contempt of court for failing to comply with an order related to the Idaho State Correctional Institution. The allegation was simple and ugly: to increase profits, the facility was staffed too thin, and false staffing reports were submitted to make it look compliant.

So by late 2016, the bear case wasn’t a debate—it was a narrative with momentum.

Mass incarceration had plateaued and started to decline for the first time in decades. Bipartisan criminal justice reform—rare alignment between liberals focused on racial justice and conservatives focused on costs—was no longer theoretical. Private prisons had scaled to meet a prison population that had exploded between 1980 and 2013. But now that population was shrinking, including at the federal level, where it fell from about 220,000 in 2013 to roughly 195,000 by 2016.

The divestment movement accelerated. Public pension funds, university endowments, and banks began re-evaluating relationships with the industry. ESG pressure stopped being a niche concern and started to look like a structural problem: fewer willing lenders, fewer patient shareholders, and a rising reputational tax on anyone who stayed.

Then the presidential campaign poured gasoline on it. Hillary Clinton publicly called for ending private prisons in a debate, and the stocks sank further, hitting their lowest levels since the Great Recession.

Inside the company, the response was a blend of pushback and repositioning. Management talked about quality improvements. It highlighted reentry programming. It floated a pivot toward community corrections and treatment services. But investors weren’t buying a reinvention story—they were pricing a business that looked politically doomed.

What the market missed—what almost everyone missed—was that American politics was about to snap in the opposite direction. The “dying business model” narrative assumed criminal justice reform would continue on a steady path.

It wouldn’t.

VI. The Trump Reversal & Immigration Detention Surge

The night of November 8, 2016 delivered one of the sharpest reversals CoreCivic investors would ever see. As Donald Trump’s Electoral College victory came into focus, the market instantly rewrote the company’s future.

CoreCivic’s stock jumped from roughly $14 a share to just over $20 the next day. Hours earlier, the dominant narrative had been “the DOJ is phasing this out.” By the morning after the election, the narrative flipped to “private prisons are back.”

And it wasn’t just CoreCivic. The two giants of the category—CoreCivic and GEO Group—both surged as investors priced in a friendlier Washington. The logic wasn’t subtle: Trump had campaigned on cracking down on illegal immigration and being tougher on crime. If that rhetoric became policy, detention demand would rise—and the companies that already owned beds would be first in line.

The confirmation arrived fast. In February 2017, Attorney General Jeff Sessions rescinded the Obama-era guidance that had directed the Bureau of Prisons to wind down private prison contracts. In his memo, Sessions argued the prior directive had “changed long-standing policy and practice” and “impaired the Bureau’s ability to meet the future needs of the federal correctional system.” He ordered the Bureau to return to its previous approach.

But the bigger story of the Trump years wasn’t the Bureau of Prisons. It was immigration detention.

The administration’s “zero tolerance” posture and expanded enforcement created a surge in demand for detention capacity. During the Trump administration, the federal immigration detention system expanded by more than 50%, a move that, according to the ACLU, overwhelmingly benefited private prison companies. The detained population reached a peak of about 55,000 people in 2019.

Financially, this was a renaissance. Reputationally, it was gasoline on a fire.

Family separations at the border triggered national outrage. Images of detained children saturated the news. And CoreCivic—already controversial—was now tied in the public mind to one of the most emotionally charged episodes in modern American politics.

That’s when the next threat stopped being theoretical: capital.

The ESG divestment movement escalated from reputational pressure to a direct business constraint. In 2019, six major banks—JPMorgan Chase, Wells Fargo, Bank of America, SunTrust, BNP Paribas, and Fifth Third Bancorp—publicly committed to no longer providing new financing to the private prison industry. According to reporting at the time, CoreCivic and GEO Group collectively stood to lose the bulk of their private financing—about $1.9 billion—as those lenders stepped away.

Large institutional investors followed. In 2019, the California Public Employees’ Retirement System voted to divest from CoreCivic and GEO Group, withdrawing $10.8 million. Advocates like Emily Claire Goldman of Educators for Migrant Justice pushed the issue, arguing that public retirement savings were funding the same companies at the center of the migrant detention abuse crisis.

For CoreCivic, the banking pullback was uniquely dangerous because of the structure it had chosen. As a REIT, the company had been engineered to send cash out to shareholders. That works when credit is plentiful. It becomes a problem when lenders decide they want nothing to do with your industry. By the end of 2016, just four of those megabanks had about $2.6 billion in lines of credit and loans tied up in CoreCivic and GEO Group. If that spigot turned off, expansion didn’t just get harder—it started to look impossible.

The company tried to manage the blow with messaging and positioning. Just before the election, on October 28, 2016, CCA announced it was rebranding as CoreCivic, describing itself as a “diversified, government solutions” provider spanning corrections, detention, and expanded reentry services. It was a bid to sound less like a prison company and more like an infrastructure-and-services contractor.

Then COVID-19 hit. Prisons and detention centers became hotspots for transmission. Lawsuits mounted. Scrutiny intensified, and CoreCivic facilities repeatedly appeared in headlines tied to outbreaks and allegations of inadequate medical response.

By 2020, the company was caught in a tightening vise: a REIT structure that limited flexibility, major banks walking away, deepening brand toxicity, and another election that could swing federal policy again. The business model that looked revived in 2017 was, once again, back on unstable ground.

Something had to give.

VII. The Biden Era & REIT Termination

When Joe Biden took office in January 2021, private prisons were back in the crosshairs. But what followed wasn’t the clean shutdown activists wanted or the total reprieve investors hoped for. It was something messier: a headline-grabbing crackdown paired with a loophole big enough to keep the industry’s most important engine running.

On January 26, 2021, Biden signed Executive Order 14006, titled Reforming Our Incarceration System to Eliminate the Use of Privately Operated Criminal Detention Facilities. The directive told the Department of Justice not to renew existing contracts with privately operated criminal detention facilities.

The rationale echoed what had been building for years. A 2016 Justice Department report had found that private prisons experienced high rates of assault, use-of-force incidents, and lockdowns. In a press briefing, Biden framed the order as “the first step to stop corporations from profiting off of incarceration that is less humane and less safe.”

In 2016, that kind of signal had detonated the stocks. This time, the market barely flinched. Investors had learned to read the fine print.

Because the executive order didn’t touch Immigration and Customs Enforcement. ICE sits inside the Department of Homeland Security, not the DOJ, so its detention contracts weren’t covered. That mattered enormously. More than 25,000 people were held in ICE detention as of early August 2021, and about 80% of ICE detention beds were still owned or managed by for-profit firms. ICE contracts made up 28% of 2020 revenue for both GEO Group and CoreCivic.

This was the critical loophole. The Bureau of Prisons business was already shrinking. ICE remained the center of gravity.

DOJ still moved. After the order, the Bureau of Prisons terminated all of its contracts with privately managed prisons and transferred incarcerated people to other bureau facilities. The impact was largely limited to the Bureau of Prisons and the U.S. Marshals Service. CoreCivic indicated it had four USMS contracts set to expire in 2021 and likely not renew, plus only one Bureau of Prisons contract.

But the most consequential shift in this period didn’t come from the White House. It came from CoreCivic.

On August 5, 2020, the company announced that its board had unanimously approved a plan to revoke its REIT election and return to being a taxable C corporation, effective January 1, 2021. The company had been a REIT from January 1, 2013 through December 31, 2020. Starting in 2021, it would no longer be a REIT for federal tax purposes.

The logic was blunt: the REIT structure was no longer helping—it was boxing them in. As a REIT, CoreCivic was built to shovel cash out the door through dividends. That looked shareholder-friendly when capital was cheap and banks were willing partners. It looked dangerous when lenders and large institutions began treating the entire sector as toxic.

CoreCivic said it believed money previously consumed by interest on borrowed funds as a REIT could be better used to serve investors across its securities and support the long-term interests of the company, its government partners, taxpayers, and the people in its care. The plan was to reduce debt first, then return capital later.

So the board discontinued the quarterly dividend and shifted the priority to debt reduction, targeting a total leverage ratio of 2.25x to 2.75x. After hitting that, the company expected to direct a substantial portion of free cash flow back to shareholders, potentially through share repurchases and future dividends.

This wasn’t happening in a vacuum. CoreCivic, based in Brentwood, derived nearly 90% of its revenue from the 43 correctional facilities it owned and the seven others it managed. It also ran residential reentry facilities with more than 5,000 beds and held a commercial real estate portfolio totaling 3.3 million square feet. Yet despite all those tangible assets, its shares were down more than 50% in 2020 and had lost more than two-thirds of their value since spring 2017.

CEO Damon Hininger summarized the problem in plain terms: “At the market prices we have experienced for our debt and equity securities, capital has become increasingly expensive.”

And that’s the tell. The REIT conversion had been sold as a way to lower the cost of capital. The REIT exit was an admission that, in this industry, the cost of capital can spike for reasons that have nothing to do with interest rates and everything to do with politics and reputation.

CoreCivic also expected to raise cash by selling “non-core” properties—anticipating $150 million—so that money could be redeployed into what it viewed as more profitable opportunities.

The Biden years, then, settled into an uneasy equilibrium. Federal prison contracts wound down, as promised. But immigration detention remained a durable demand source, and the federal detention population grew under Biden.

By the end of Biden’s term, CoreCivic had stabilized, paid down debt, and reset its corporate structure for flexibility. It had weathered another existential moment—and remained, as ever, a company waiting for the next political swing.

VIII. Current Landscape & Recent Developments

As 2025 drew to a close, CoreCivic found itself in a place that would’ve seemed almost impossible during the bleak stretches of 2016 and 2020: winning new contracts, reactivating idle facilities, and talking openly about record revenue.

In Q3 2025, the company reported total revenue up 18.1% year-over-year, which it attributed to “building momentum” and a wave of facility activations. The surge was heavily federal. Revenue from federal partners rose 28%, driven primarily by ICE—where revenue jumped 54.6%.

That shift shows up starkly in the quarterly comparison. CoreCivic reported ICE revenue of $215.9 million in Q3 2025, up from $139.7 million in Q3 2024. In other words, immigration enforcement had become the engine again. In the third quarter, federal partners—primarily ICE and the U.S. Marshals Service—accounted for 55% of CoreCivic’s total revenue.

CoreCivic didn’t just benefit from higher demand; it moved to meet it. The company announced new contract awards for four facilities that it expected could generate about $320 million in annual revenue once stabilized. It also secured two new ICE contracts enabling the use of 3,593 beds, with anticipated combined annual revenue of nearly $200 million.

And CoreCivic signaled it could go much further. The company said it had informed ICE it could make roughly 30,000 additional beds available—about 13,400 of them spread across nine currently empty corrections and detention facilities, with the remainder coming from adding beds to facilities already operating.

The market reacted the way it always does when Washington turns into a tailwind. “Since Trump’s reelection in November, CoreCivic’s stock has risen in price by 56% and Geo’s by 73%. ‘It’s the gold rush,’” said one professor who studies private prisons.

CEO Damon Hininger leaned into the moment. “Our business is perfectly aligned with the demands of this moment. We are in an unprecedented environment with rapid increases in federal detention populations nationwide and a continuing need for solutions,” he said.

At the same time, the company began preparing for a new chapter at the top. CoreCivic’s board appointed Patrick D. Swindle as President and Chief Executive Officer effective January 1, 2026, after naming him President and Chief Operating Officer on January 1, 2025. He will succeed Damon T. Hininger, who has served as CEO since August 17, 2009.

Hininger’s tenure has been unusually long—and unusually emblematic of the company itself. He joined Corrections Corporation of America as a correctional officer at the Leavenworth Detention Center in Kansas in 1992. In 1994, he became a training manager at the Central Arizona Detention Center, and by 1995 he had moved to corporate headquarters in Nashville. Fourteen years later, he took the CEO seat—and held it through the Obama crackdown, the Trump rebound, COVID, the banking exodus, and the decision to walk away from REIT status.

By 2025, management was framing the year as a breakout. CoreCivic forecast $2.5 billion in revenue and more than $450 million in annual run-rate EBITDA—both records for the organization if achieved.

But the old problems didn’t disappear just because demand returned.

From 2022 through 2024, Tennessee fined CoreCivic more than $29.5 million for inadequate staffing at four facilities. At Trousdale Turner Correctional Center, turnover reached 188% in 2023. Understaffing was cited in a lawsuit related to an inmate’s death and in a civil rights investigation by the U.S. Department of Justice.

The staffing story has long shadowed the sector. A 2017 DOJ report cited correctional officer vacancies as high as 23%. One former guard at a CoreCivic facility described repeated assaults that sent him to the emergency room three times. And when Leavenworth sued CoreCivic, the complaint opened with a federal judge’s description of the prison: “The only way I could describe it frankly, what’s going on at CoreCivic right now is it’s an absolute hell hole.”

Meanwhile, the competitive picture has hardened into something close to a duopoly. The GEO Group had a larger market capitalization—about $3.81 billion versus CoreCivic’s $2.37 billion. GEO has said private companies supply 90% of ICE’s detention beds, and that GEO operates 42% of those facilities.

So for investors, the question in late 2025 wasn’t whether business was good. It clearly was. The question was whether this was durable demand—or just another politically driven boom that could snap back, hard, with the next electoral swing.

IX. Business Model Analysis & Strategic Frameworks

We’ve walked the timeline: the founding tailwinds, the REIT experiment, the federal whiplash, the banking freeze, and the latest demand surge. Now comes the part where we stop narrating and start stress-testing. If you run CoreCivic through classic strategy frameworks, the picture that comes back is clear—and not especially comforting if you’re looking for a durable moat.

Porter's Five Forces

Threat of New Entrants: LOW — Starting a private corrections company at scale is brutally hard. You need licensing, accreditation, and government approvals. You need massive capital to build or acquire facilities. And you need a tolerance for reputational blowback that very few boards, lenders, or executives would sign up for today. The result is what you’d expect: no meaningful new entrant has shown up in decades, and the major players have decades-long relationships with government buyers.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW — The biggest input is labor, and in most CoreCivic facilities, corrections officers aren’t unionized. Wages matter, but the company isn’t hostage to a single supplier the way airlines are hostage to aircraft makers, or chip companies are hostage to fabs. Construction, food service, medical supplies, and maintenance are also largely commodity-like. There’s pain in staffing, but not classic supplier lock-in.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: HIGH — This is the weak point, and it’s foundational. CoreCivic’s customers are governments: federal agencies, states, and counties. They are concentrated, politically exposed, and perfectly capable of bringing the work in-house if they decide to. Contracts get rebid. Priorities change with elections. And when a buyer like the Department of Justice decides it’s done—as it signaled in 2016—CoreCivic can’t negotiate its way out of the headline.

Threat of Substitutes: MEDIUM-HIGH — The substitute isn’t another vendor. It’s the government choosing not to outsource, or choosing not to incarcerate as much in the first place. Public prisons and jails are the default option. Reform efforts can reduce demand for beds. And alternatives like diversion programs, community supervision, and electronic monitoring can shrink the need for detention capacity entirely. The industry’s interest in monitoring and “alternatives to incarceration” is, in part, a hedge against that reality.

Competitive Rivalry: MEDIUM — On paper, this looks like a cozy market: basically a duopoly with GEO Group, plus smaller players like Management & Training Corporation in certain niches. But rivalry doesn’t disappear just because there are few competitors—because the biggest competitor is always an option: the government doing it itself. When contracts come up for renewal, pricing and performance are suddenly everything, and the stakes are existential facility by facility.

Hamilton's Seven Powers

Scale Economies: MODERATE — There are real benefits to spreading headquarters overhead, procurement, training, and compliance across dozens of facilities. But prisons are still local, operationally and politically. A bed in Tennessee doesn’t solve a capacity crunch in California. Scale helps, but it doesn’t turn the business into a flywheel.

Network Effects: NONE — There’s no network dynamic here. One more facility doesn’t make the rest more valuable in the way another node makes a marketplace or payments network stronger.

Counter-Positioning: HISTORICALLY YES, NOW NO — In the early decades, CoreCivic’s pitch had bite: faster builds, flexible capacity, and an operating model governments weren’t set up to replicate quickly. Over time, governments adapted, and the private sector’s “we can do what you can’t” advantage narrowed. Today, the differentiator is less about unique capability and more about who already has beds ready when a crisis hits.

Switching Costs: MODERATE — Switching is inconvenient. Transitioning a facility requires staffing, operational handoffs, and coordination under public scrutiny. But the last decade has shown that when the politics demand it, governments will swallow disruption and switch anyway. Operational friction exists; it just isn’t decisive.

Branding: NEGATIVE POWER — The brand doesn’t confer trust—it attracts scrutiny. “Private prison” is a loaded phrase, and CoreCivic’s rebrand was itself a tacit admission that the old identity had become toxic. There’s no consumer demand to cultivate here. Brand recognition mostly functions as a targeting system for activists, politicians, and headline writers.

Cornered Resource: WEAK — The closest thing CoreCivic has to a cornered resource is its existing footprint: facilities in specific jurisdictions, plus established contracting relationships. That matters. But it’s not permanent. Buildings age. Contracts end. Relationships reset with elections. And if the political will and capital ever align, new public construction can erase geographic advantage.

Process Power: MODERATE — There’s real institutional know-how in operating secure facilities: hiring pipelines, training, procedures, compliance systems, and decades of operational learning. That’s a capability. The problem is that it’s teachable. When governments are motivated—and funded—they can build comparable competence.

The Brutal Reality

Put it all together and you get a tough conclusion: CoreCivic doesn’t have much in the way of durable competitive advantage. It isn’t protected by network effects, branding, switching costs, or hard-to-replicate technology. It survives on a mix of execution, existing capacity, and the simple fact that governments often need beds faster than they can create them.

That’s why the “moat,” such as it is, looks more like two things that aren’t really moats at all: budget constraints and bureaucratic inertia. Those can be powerful. They can also vanish under the right political conditions.

This is where the investor debate gets slippery. Value investors can point to cash flow and depressed multiples and argue the market is overpricing risk. But in a business this tied to elections and public legitimacy, the discount might not be irrational—it might be the product.

So the cleanest way to frame CoreCivic strategically is not as a traditional business bet. It’s a political bet. The key variable isn’t whether management can run facilities efficiently. It’s whether the United States continues to choose, year after year, to outsource meaningful detention capacity to the private sector. And no spreadsheet can underwrite that with confidence.

X. The Playbook: Lessons for Founders & Investors

CoreCivic’s forty-year history is full of lessons for business builders and investors—just not the kind you usually want to copy-paste.

On Government Contracting: CoreCivic is the purest form of the government-contracting tradeoff. When the political winds are behind you, federal contracts can look like the promised land: multi-year agreements with creditworthy counterparties who virtually never default. But that stability is paired with a unique kind of concentration risk. When policy changes, CoreCivic can’t “find new customers.” There is no commercial market for prison services. Government is the customer, full stop. If you’re building a business that depends on government demand, you’re not just underwriting execution risk—you’re underwriting binary political risk.

When Your Business Model Becomes Controversial: The 2016 rebrand from Corrections Corporation of America to CoreCivic captured a common instinct: change the name, soften the edges, emphasize adjacent services. But you can’t rename your way out of what you do. The company poured effort into language about “reentry services” and “government solutions,” yet the core product in the public mind remained detention. Activists didn’t buy it. Many investors didn’t either.

The ESG Reckoning: CoreCivic ran into ESG-style pressure before “ESG” became a standard label. The 2019 bank pullback showed how social and political pressure can translate directly into higher financing costs and fewer options. That mattered because both CoreCivic and GEO Group have historically relied on loans and credit lines to finance facilities and maintain flexibility. The takeaway is uncomfortable but practical: if you operate in a controversial category, assume parts of the financial system may eventually refuse to fund you—and build a balance sheet that doesn’t require constant external goodwill.

Financial Engineering Limits: The REIT conversion looked smart when it boosted shareholder returns through tax efficiency and dividends. But it couldn’t insulate the company from the underlying risk: the business itself became politically contested. When scrutiny and lender divestment accelerated, the REIT model’s mandatory distributions limited CoreCivic’s ability to retain cash at the moment it needed resilience most. The company operated as a REIT from January 1, 2013 through December 31, 2020, then terminated the structure and returned to being a taxable C corporation. Financial structure can improve outcomes in calm conditions; it can’t fix a premise the market decides is unacceptable.

Bipartisan Risk: One of the most dangerous places to sit in American politics is the position where both parties can turn on you, just for different reasons. Private prisons draw sustained hostility from progressives focused on mass incarceration and immigration detention. But they also face periodic conservative skepticism around cost, accountability, and the optics of profiting from incarceration. Unlike defense contractors, which tend to enjoy durable bipartisan support, or renewables, which have clear partisan champions, private prisons have no reliably safe political home.

The Diversification Challenge: CoreCivic has repeatedly promised diversification into reentry services, community corrections, and related real estate solutions. It made that ambition real with acquisitions, including Avalon Correctional Services Inc, Correctional Management Inc, and four facilities formerly owned by Community Education Centers Inc between 2015 and 2016, and later Rehabilitation Services Inc in 2019. But the center of gravity never truly moved. Detention remains the overwhelming majority of revenue. When your assets and operating capabilities are purpose-built for one controversial use case, “diversification” is harder than it sounds.

Regulatory Capture vs. Democratic Accountability: CoreCivic and its peers have long been active in politics—donating, lobbying, and advocating for policies that sustain demand. The industry has spent millions of dollars doing it; CCA alone spent $17.4 million in lobbying from 2002 through 2012. But this playbook has limits. When public opinion swings hard—as it did around immigration detention and the broader critique of mass incarceration—political spending can’t fully reverse the cultural direction of travel.

When Cash Flow Isn’t Enough: Here’s the investor punchline. CoreCivic can generate consistent cash. The balance sheet can be manageable. The operations can be run professionally. And still, large parts of the institutional market want nothing to do with the equity for non-financial reasons. At the same time, the stock still ends up inside portfolios that claim ESG principles, largely because index funds hold it by default. That’s how you wind up with Vanguard and BlackRock owning significant stakes through index products—around 15% and 12% in both prison companies. The result is a strange kind of public-market limbo: a stock that can look cheap on paper, but stays cheap because the discount may be structural, not temporary—the anatomy of a value trap.

XI. Bull vs. Bear Case

The Bull Case

The bull thesis on CoreCivic rests on a few big, stubborn realities:

Immigration enforcement doesn’t go away. Even when administrations change tone, the system still needs capacity. Biden’s executive order targeted DOJ contracts, but it didn’t touch ICE because ICE sits inside the Department of Homeland Security. The detained population hit its high-water mark under Trump, fell during the pandemic, then began climbing again under Biden. If you believe immigration dysfunction is durable—and politically bipartisan in practice—then you believe beds will stay in demand no matter who wins elections.

State business also provides a second leg. Some states remain willing, even eager, to outsource capacity. CoreCivic, for example, won a new management contract tied to Montana, with 120 Montana inmates arriving at the 2,672-bed Tallahatchie County Correctional Facility. Additional Montana inmates were also transferred to the 1,896-bed Saguaro Correctional Facility in Arizona under an existing contract. It’s not glamorous, but it’s diversification away from a single federal decision-maker.

Then there’s the value angle. CoreCivic trades at a discount to its own history despite producing steady cash. Post-REIT, the company has more flexibility to manage its capital structure, do smaller acquisitions, and pivot where it can. And it has said it plans to accelerate its share repurchase program—basically signaling that if the market won’t re-rate the stock, management will use cash flow to retire shares.

Finally, the capacity constraint is real. Governments don’t build prisons quickly. New facilities require legislative approvals, bond financing, public hearings, lawsuits, years of construction—the whole machinery of democracy. Private operators can move faster, especially when they already own idle capacity. CoreCivic has told ICE it can make roughly 30,000 additional beds available.

Layer on top of that the company’s message that quality is improving—more reentry programming, educational services, and recidivism reduction—and you get the bullish storyline: this is an unpopular company in a market that still needs the service. And right now, demand is rising. With management forecasting $2.5 billion in revenue and more than $450 million in annual run-rate EBITDA, 2025 and 2026 were shaping up to be record years if the activation pipeline held.

The Bear Case

The bear case starts with the long view: incarceration isn’t on an endless upward trajectory anymore. The decades-long expansion has slowed, and reform coalitions don’t live in only one party. Even red states have periodically rethought how much incarceration they can afford, and whether it delivers outcomes that justify the cost.

Then there’s the risk that never leaves this business: politics. Biden’s Executive Order 14006 became a symbol of the threat—and then it was rescinded as part of Trump’s “Initial Rescissions of Harmful Executive Orders and Actions” executive order on January 20, 2025. That’s the whole problem in one sentence. The policy can flip with a pen. And when more than half your revenue is tied to federal partners, every election becomes a potential shock to the system.

Capital markets make it worse. The bank pullback wasn’t a moment; it was a migration. Danish pension funds PKA and Lærernes Pension removed CoreCivic from their portfolios in 2019. Canada’s largest pension fund, PSP, fully divested in 2021. Norway’s KLP excluded CoreCivic in 2022, citing human rights concerns. And in 2024, banks including ANZ, Nordea, and Danske Bank added the company to their investment exclusion lists. Even if the company performs operationally, its cost of capital can stay structurally higher than “normal” businesses simply because a large part of the financial system prefers not to touch the category.

Operational and legal risk is the other drag that never fully clears. COVID-era lawsuits, civil rights investigations, staffing-related deaths—these aren’t one-off events in this industry; they’re recurring hazards. Tennessee’s fines of more than $29.5 million for inadequate staffing between 2022 and 2024 underline how quickly “execution issues” become contractual penalties, headlines, and lawsuits.

And the staffing problem isn’t just a cost issue—it’s existential. How do you recruit and retain talent in a stigmatized business where the work is hard and the scrutiny is constant? Trousdale Turner’s 188% turnover rate in 2023 is the kind of number that doesn’t just suggest stress; it suggests instability. Understaffing degrades safety and quality, quality failures deepen reputational damage, and reputational damage makes staffing harder. That’s a compounding loop, not a temporary headwind.

Finally, the substitute threat is getting sharper. Technology—GPS monitoring, electronic surveillance, algorithmic risk tools—can make “alternatives to incarceration” more feasible. GEO Group’s investment in monitoring is, in part, an acknowledgment that the world may eventually want fewer beds and more supervision.

And even if none of that happens, there’s the simplest bear argument: a growing number of investors just won’t own a company that profits from human confinement, regardless of margins, audits, or program improvements. That’s not a debate you can win with a better quarterly slide deck. It permanently narrows the buyer base for the stock.

The Likely Reality

CoreCivic probably survives, but it doesn’t get to be a normal compounder. The pattern looks built in: boom periods when enforcement surges, leaner years when reform and divestment pressure rises. Growth is likely capped by two structural constraints at the same time—downward pressure on incarceration over the long arc, and a higher, stickier cost of capital because much of the market treats the sector as uninvestable.

The most plausible endgames are not heroic. A slow decline in relevance over the next decade or two. A take-private deal if public-market friction becomes too costly. A merger with GEO Group to consolidate scale. Or some form of government buyout of facilities during a future reform push.

In other words: cash flows may persist, but investors hoping for durable growth or sustained multiple expansion are probably looking in the wrong place.

XII. Key Metrics for Investors

If you’re going to follow CoreCivic—controversy and all—you don’t need a hundred metrics. You need a small handful that tell you, quickly, whether the story is tightening or unraveling. Three stand out:

1. Compensated Occupancy Rate: This is the cleanest read on whether CoreCivic’s assets are actually earning. In Q4 2024, the company reported a 75.5% compensated occupancy rate, its highest level since Q1 2020. By Q3 2025, total occupancy across the safety and community segments reached 76.7%, up from the prior year. The takeaway is simple: empty beds don’t just mean lost revenue—they still carry fixed costs. When this number rises, the model starts to work. When it falls, everything gets harder.

2. Federal Revenue Concentration: This is the political risk meter. In Q3 2025, federal partners—primarily ICE and the U.S. Marshals Service—made up 55% of total revenue. That concentration cuts both ways. It can drive growth quickly when Washington demand surges, but it also means the company is perpetually one election away from a major reset. If CoreCivic can grow its state share meaningfully, that’s real de-risking.

3. Idle Facility Count and Activation Pipeline: This is the “option value” embedded in the business. CoreCivic has said it can make roughly 30,000 additional beds available, including about 13,400 beds across nine currently empty facilities. Those dark facilities are a drag when they sit idle—carrying costs without revenue—but they become a weapon when demand spikes and governments need capacity fast. The key is not just how many beds exist, but which facilities are getting activated, and how quickly the activation pipeline turns into signed contracts and occupied beds.

XIII. Epilogue & Reflections

The fundamental question CoreCivic forces us to confront isn’t really about prison operations, financial structures, or stock valuations. It’s about whether private companies should profit from incarceration in a democratic society. And there’s no definitive answer a story like this can deliver, because the question isn’t empirical. It’s moral.

What CoreCivic reveals about American criminal justice, capitalism, and democracy is complicated and, in places, unsettling. The company exists because government systems couldn’t—or didn’t—build enough capacity during the incarceration boom. Private capital stepped into that vacuum, offering speed and flexibility when states and federal agencies were overwhelmed. You can read that as market efficiency. You can also read it as a failure of public governance. The same facts support both interpretations.

That’s the unresolved tension at the heart of the private-prison model: prisons are a public-good function tied to safety, legitimacy, and state power. Introducing a profit motive into that machinery may create efficiency. It may also create perverse incentives. The debate has lasted decades because the tradeoff is real, and because different people weigh risk, rights, and outcomes differently.

It’s tempting to file CoreCivic alongside other “sin stocks”—tobacco, gambling, weapons—and move on. But private prisons haven’t reached the same uneasy equilibrium those industries have with investors and the public. The moral stakes feel different. Taking someone’s freedom, by design and for profit, doesn’t land like selling cigarettes or running a casino. Even people who tolerate vice often recoil at confinement.

And that’s before you get to the part the numbers can’t carry. Behind “occupancy” are actual lives. Behind “per diem rates” are people separated from families, jobs, and futures. Financial analysis has to abstract away from that human reality to make sense of the business. But a complete view of CoreCivic requires holding both truths at once: the spreadsheet is real, and so are the people it describes.

For investors, that leaves a question no analyst can answer for you: when does responsibility extend beyond returns? Some will say the role of markets is to price risk and allocate capital, not to adjudicate morality. Others will argue there are categories where profit itself is the ethical problem, regardless of execution. This story can help you understand what you’d be underwriting. It can’t tell you what you should be comfortable owning.

For founders, CoreCivic is its own warning label. Some markets offer profit and stability on paper, but come with permanently elevated political risk, reputational drag, and a narrow set of possible outcomes. If your business depends on controversial government policy, you’re not just building a company. You’re tying your fate to the direction of the country—and accepting that the country can turn quickly.

Zoomed out, mass incarceration looks like a policy failure by almost any measure. The United States has incarcerated far more people than peer nations for decades, without clear evidence of proportionally better public safety outcomes. Private prisons are not the cause of that choice. They’re a symptom and an adapter: a way the system expanded capacity to meet demand created by drug policy, sentencing laws, and immigration enforcement.

Which brings us back to the paradox. CoreCivic can be, simultaneously, a legitimate government contractor delivering capacity that agencies say they need, and a company whose best years tend to coincide with America detaining more people. That tension can’t be solved by better messaging, a different corporate structure, or even better operations. It can only be resolved—if it ever is—by the democratic process that decides what incarceration should look like, how much of it society will tolerate, and whether it’s a public function that should ever be delegated to a profit-seeking firm.

Until then, CoreCivic remains what it has always been: a business built to thrive in the spaces where policy, capacity, and conscience collide.

XIV. Further Reading & Resources

Essential Reading

- "American Prison" by Shane Bauer — The clearest, most visceral window into what it looks like on the ground when a prison is run as a business, based on Bauer’s time undercover as a guard in a CCA facility.

- "The New Jim Crow" by Michelle Alexander — The modern classic on how policy choices helped produce mass incarceration, and why its impacts are unequal.

- CoreCivic SEC Filings (2012-2025) — If you want to watch the story change in real time, read the annual reports: the risk factors, the language shifts, the REIT era, and the post-REIT repositioning.

- "Banking on Bondage" by ACLU — A forceful critique of the industry’s economics, incentives, and the role of private capital.

- DOJ Office of Inspector General Reports — The audits that show up again and again in the political case against federal private prison contracting.

- "The Prison Industrial Complex" by Angela Davis — A foundational ideological critique that helps explain why privatized incarceration faces opposition beyond questions of cost or performance.

- "In The Public Interest" Research on Occupancy Guarantees — A practical look at how contracts are written, and why “guaranteed beds” became such a lightning rod.

- Senate Testimony Transcripts (2012, 2016, 2019) — The executive narrative, stated under oath, in the moments when scrutiny peaked.

- Securities Filings Around REIT Conversion/Termination — The paper trail for the financial engineering: why the company entered the REIT structure, and why it later backed out.

- Brennan Center for Justice Reports — Consistent, policy-focused analysis tracking how private prisons fit into broader criminal justice and detention debates.

Key Context

- Academic studies comparing private versus public prison costs and outcomes are still contested, and both critics and defenders can point to research that supports their side.

- Investigative reporting from Mother Jones, ProPublica, and local newspapers has often been the fastest way to understand what’s happening facility by facility, beyond corporate statements.

- For an industry-friendly lens, trade publications and American Correctional Association materials lay out how operators describe standards, accreditation, and best practices.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music