Casella Waste Systems: The King of the Northeast

Introduction: The "Gold" in the Green Mountains

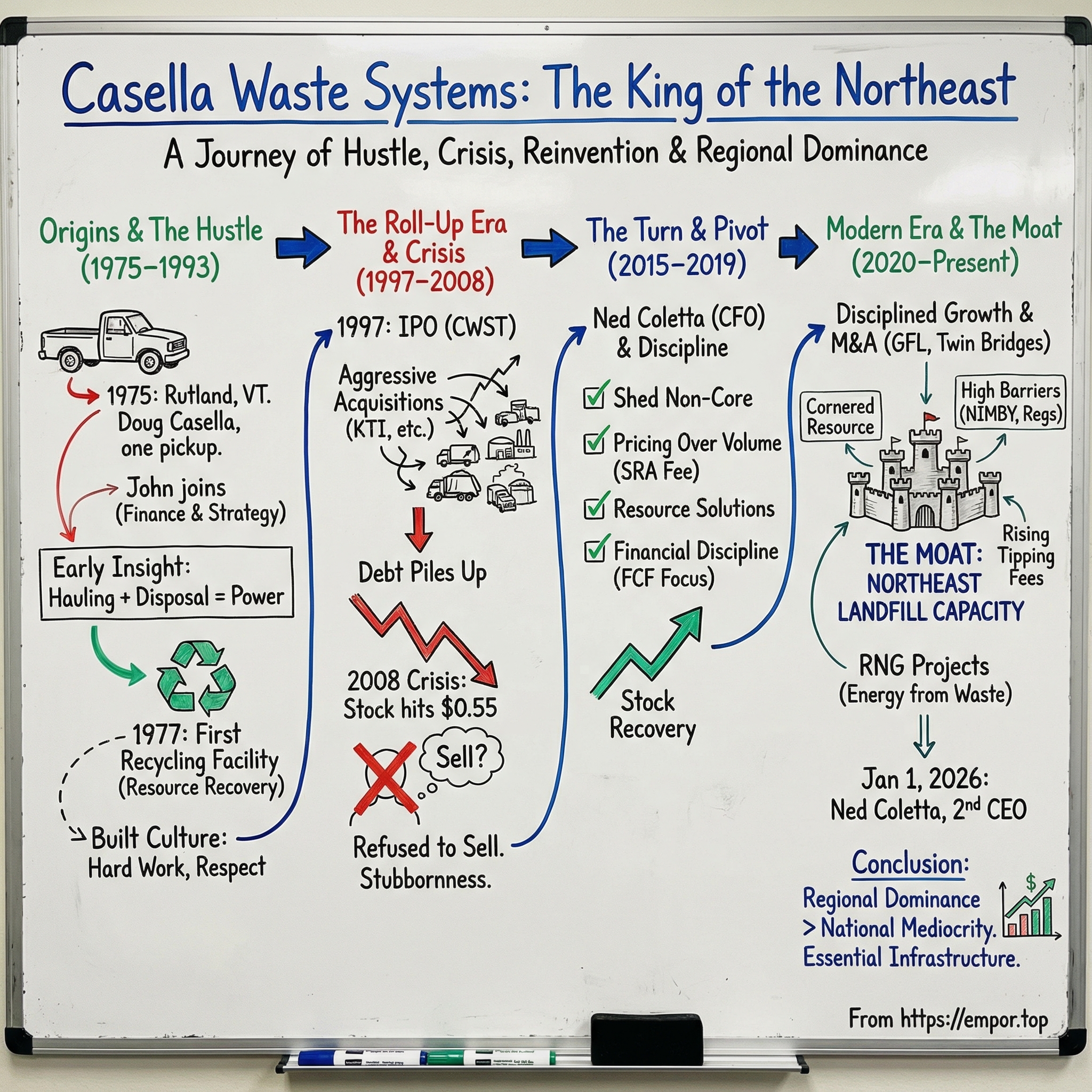

Picture a chilly April morning in 1975. Rutland, Vermont is still shaking off winter, tucked up against the Green Mountains. A young Doug Casella climbs into a pickup truck he bought with money saved from high school jobs and odd work. His first route is small: a few customers around Rutland and nearby Killington. No business plan. No investors. No fancy degree. Just a simple insight that turns out to be ironclad: everybody produces trash, and somebody has to deal with it.

That pickup-truck hustle became Casella’s Refuse Removal, founded in Rutland in 1975—the seed that eventually grew into Casella Waste Systems.

Nearly fifty years later, the scale is almost hard to reconcile with that first morning. Casella is now a public company with a market capitalization around $6.7 billion. In 2024, it reported $1.557 billion in revenue, up meaningfully from the year before. It serves more than a million customers across residential, commercial, municipal, institutional, and industrial end markets. And it has expanded beyond just picking up bins: today Casella runs collection, transfer, recycling, organics, and disposal, plus resource management services across more than 10,000 customer locations in over 40 states.

Still, the Casella story isn’t a straight line of “small business becomes big business.” It’s a story with a hangover from the roll-up era, a brush with real financial danger, and then an unusually disciplined reinvention. And at the center of it is a surprisingly powerful idea: geography.

Here’s the thesis. Casella isn’t just a “trash company.” Over the last decade, it has turned into a masterclass in what Hamilton Helmer calls a Cornered Resource—owning something scarce that competitors can’t easily replicate. In Casella’s world, that resource is permitted landfill capacity in the Northeast.

The pricing tells the story. In the Midwest, dumping a ton of trash can cost something like $25 to $30. In the Northeast, it’s often more than double. Industry data shows the region’s tipping fees are the highest in the country, and they’ve risen over time. The reason isn’t mysterious: environmental regulation is stricter, permitting is harder, and local opposition is fierce. New landfills are politically close to impossible. So the “hole in the ground” becomes the bottleneck—and the owner of the hole has leverage.

That’s what separates Casella from the national giants. Waste Management and Republic Services are enormous, with market caps that dwarf Casella’s. But their advantage is national scale. Casella’s advantage is different: it built regional dominance in one of the most difficult, most constrained waste markets in America. Instead of trying to paint the whole map, Casella focused on becoming the incumbent in a tight, defensible geography—king of a small, impenetrable castle rather than a minor lord in a sprawling empire.

Today, Casella provides integrated solid waste services across seven Northeastern states—Vermont, New Hampshire, New York, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Maine, and Pennsylvania—with its headquarters still in Rutland. And after major acquisitions in 2023, it pushed further into the Mid-Atlantic, adding Delaware and Maryland to its footprint.

Getting from one pickup truck to that position required surviving a near-collapse, making hard choices, and having the stubbornness to refuse to sell at the bottom. That’s the story we’re going to tell.

Origins: The Hustle & The Brothers (1975–1993)

The Casella brothers grew up in working-class Vermont, the sons of immigrants who believed in sweat equity. Their home was a modest apartment their father built above a red brick motel he owned on Route 4, between Rutland and the ski trails.

Raymond Casella had come north from Yonkers, New York in the early 1950s. He was a mason by trade, and between running the inn with his wife, Thurley, he picked up construction work and whatever else it took to keep the family moving forward. Doug, John, and their sister Judith grew up inside that rhythm: early mornings, hard work, and no patience for excuses.

When the boys were teenagers at Mount St. Joseph Academy, their summers weren’t for lounging. They were for mixing cement and carrying bricks. John would later say their father was “a taskmaster, to say the least,” and he credited both parents with building the work ethic that would define the company long before there was a company.

Doug, the younger brother, went first. In 1975, he started hauling trash with a single truck. It was small, local, and unglamorous—exactly the kind of business that only works if you show up, do the job, and do it well. And that’s what he did.

A year in, Doug called John with a simple pitch: leave the job at Killington and come be my partner. John had been working in hospitality like their parents, but he could see what Doug had found: a basic service with steady demand, and a chance to build something real.

Their partnership clicked because it was naturally split down the middle. Doug was operations—comfortable in the cab of a truck, close to customers, fluent in the physical reality of the work. John brought finance and strategy—someone who could think beyond the next route and, eventually, navigate public markets, crisis, and reinvention.

Even in those early days, the family’s connection to the business ran deeper than routes and customers. The brothers hauled their trash to a landfill in Danby that their father bought the same year Doug launched his business. Casella didn’t own that landfill, and it’s now closed—but the arrangement gave the young company an early boost and hinted at the bigger lesson they were already absorbing: hauling is important, but disposal is power.

Control enough of the waste stream—collection, transfer, recycling, disposal—and you don’t just compete. You shape the economics of the whole market. That idea would take decades to fully execute, but the brothers were standing next to it from day one.

They also showed unusual foresight about sustainability—long before it became a corporate slogan. In 1977, they built the company’s first recycling facility, which was also Vermont’s first. It wasn’t a marketing move. It was a practical, New England kind of insight: waste isn’t just something to get rid of; it’s something you can sort, recover, and manage as a system.

Vermont’s bottle bill had taken effect a few years earlier, and the facility processed glass, PET plastics, aluminum, and steel. The timing was prescient. Vermont’s environmental consciousness was ahead of the curve, and the Casellas put themselves right at the intersection of trash collection and resource recovery.

But what truly set them apart wasn’t just what they built—it was the culture they baked in. Years later, that culture showed up in how John Casella evaluated talent. Ned Coletta, coming from med-tech in the early 2000s, wanted to learn by working closer to senior leadership. John agreed to meet him—with a catch.

“John said, ‘Ned, I’m going to interview you at 8 a.m., but show up at the Walmart parking lot at 4 a.m. Have boots on, jeans, work gloves, and I’ll have one of my drivers pick you up,’” Coletta recalled. Coletta spent the morning working alongside a driver, and then met John in between the route and the interview so they could talk—after John had seen how he carried himself.

It wasn’t hazing. It was a values test. Do you respect the work? Can you connect with the people who actually run the company every day? Are you willing to do the job before you try to manage the job? Coletta passed. He joined in 2004 and, on January 1, 2026, became only the second CEO in the company’s fifty-year history.

John himself stayed close to the industry beyond Casella, serving in advisory roles on solid waste issues for the Governors of Vermont, New York, and New Hampshire. His path was practical and local, too: an Associate of Science degree in Business Management from Bryant & Stratton College and a Bachelor of Science degree in Business Education from Castleton University.

By the early 1990s, the brothers had built a solid regional business—grounded in hard work, tight operations, and an early understanding that the bottleneck in waste is where it ends up.

But the industry around them was changing fast. And the Casellas were approaching a fork in the road that would shape the next few decades: stay small and private, or step onto the roll-up treadmill that was transforming waste management across America.

The IPO and The "Wild West" Roll-Up Era (1997–2008)

To understand Casella’s near-death experience, you have to understand what the waste business turned into in the late 1990s.

This was the age of the roll-up. Wayne Huizenga had already turned Waste Management into a consolidation machine, then took the same playbook to Blockbuster and AutoNation: buy up mom-and-pops in a fragmented industry, stack the routes, squeeze out costs, and let “scale” do the rest. Wall Street loved it. If you could tell a clean story about synergies and growth, the capital was there.

So in 1997, Casella stepped onto the treadmill. The company went public on NASDAQ under the ticker CWST, and the timing was almost surreal: trading began the day after one of the largest single-day market drops in U.S. history. You’d expect investors to hide. Instead, despite the jitters, Casella’s IPO became one of the most successful debuts the industry had seen.

The date was October 28, 1997. Casella now had a currency it never had before: public-market capital. And the Casellas intended to use it.

What followed was an aggressive acquisition spree. The biggest early swing came in 1999, when Casella bought KTI, Inc., a publicly traded waste-handling company with meaningful disposal and recycling operations, including KTI Recycling of New England. It was a step-change deal—one that quickly broadened Casella’s reach and deepened its material-processing footprint.

But the roll-up logic has a trap built into it: growth is easy to buy, and discipline is hard to maintain.

Casella bought a lot, and it bought fast—sometimes in places that didn’t neatly connect to the routes and assets it already had. And it built out significant recycling infrastructure, tying more of the company’s economics to commodity cycles it couldn’t control. Meanwhile, debt piled up.

The strain showed up most clearly in the balance sheet. Acquisitions plus a massive landfill development initiative in the early 2000s pushed leverage to uncomfortable levels. Ned Coletta, who later became CFO, described what he inherited: “When I became CFO in 2013, we were levered, which means how much debt we had to how much cash we produced in a year was close to six times, which is very, very high. We were having a really hard time investing back into the business.”

Six times. That’s not “a little aggressive.” That’s operating with almost no margin for error—where a downturn, a bad year in recycling, or any unexpected shock can turn into an existential problem.

And then the shock arrived: the 2008 financial crisis.

By March 2009, the market had little patience for leveraged roll-ups with uneven returns. On March 12, 2009, Casella’s stock closed at $0.55 per share. The next day, it hit $0.53—its all-time low. A company that had gone public with one of the industry’s strongest IPOs was now trading like a penny stock.

Fifty-five cents. In just over a decade, the roll-up strategy that was supposed to create value had pushed Casella to the edge. Investors began circling. Calls for a breakup or sale got louder. To outsiders, the obvious move was to take what you could get and move on.

The story could have ended right there. Many expected John Casella to sell.

But he refused. This wasn’t a spreadsheet exercise for the brothers. They’d spent their lives building the company, signed personal guarantees, and put their family name on trucks that drove through their hometown every day. Selling at the bottom wasn’t just financially painful—it felt like surrender.

The Turn: Crisis, Activism, and the Strategic Pivot (2015–2019)

The years after the 2008 crisis weren’t a comeback montage. They were a slog.

From 2009 into the mid-2010s, Casella did what highly levered companies have to do: keep the lights on, pay down debt where it could, and steady day-to-day operations. But “stable” isn’t the same as “healthy.” The stock stayed stuck. Returns on invested capital were still disappointing. And the core issues from the roll-up era—too many non-core businesses, recycling economics tied to volatile commodities, and assets scattered across less-than-ideal geographies—were still sitting there, unresolved.

The real turning point came when management stopped asking, “How do we grow?” and started asking, “What are we actually trying to be?”

A key figure in that shift was Ned Coletta, who had become Senior Vice President, Chief Financial Officer and Treasurer in December 2012. Inside the company, he was credited with helping reset strategy, impose capital discipline, and build a culture of accountability—less “do the deal,” more “does this make sense?”

The pivot that emerged wasn’t one silver bullet. It was a set of choices—hard ones—stacked on top of each other.

First, Casella started shedding the fat. That meant divesting non-core operations and pulling out of low-margin geographies. The filter became brutally simple: does this strengthen the core business in the core footprint? If not, it didn’t belong.

Second, it chose pricing over volume. This was the cultural break from the roll-up mindset. Instead of chasing revenue for revenue’s sake, Casella prioritized returns. The signature move here was the Sustainability/Recycling Adjustment (SRA) fee—designed to take recycling from a commodity casino and turn it into a more predictable service. When China’s National Sword policy disrupted recycling markets in 2018, Casella wasn’t immune to the chaos—but it had a mechanism to pass much of that commodity risk through to customers, keeping margins from whipsawing with global paper and plastic prices.

Third, it leaned into a “Resource Solutions” model. Rather than selling itself as the company that simply collects waste and dumps it, Casella repositioned as a partner that helps customers hit sustainability goals. As the company put it, sustainability had been part of its DNA since the recycling facility it built in 1977—but the sophistication changed. Now it was providing circular services for industrial customers like Becton Dickinson, helping manage hard-to-recycle plastics coming out of manufacturing processes.

Fourth, it tightened the financial screws. Casella focused intensely on free cash flow and capital discipline—saying “no” to acquisitions that didn’t clear return hurdles. Coletta also pushed technology adoption, including Microsoft Dynamics and NetSuite, to streamline operations and bring down general and administrative costs.

This is what made the turnaround real: it wasn’t just a narrative shift. The balance sheet improved, leverage came down, and investor confidence started to rebuild. By the end of the 2010s, Casella wasn’t just surviving anymore—it was setting itself up to buy again, but with a completely different rulebook.

The stock told the story in hindsight. After bottoming at $0.55 in 2009, CWST rebounded sharply over the years that followed—closing 2016 at $12.41 after a strong run that year—and later reached an all-time high closing price of $120.37 in May 2025.

From pennies to triple digits is a great chart. But the more important takeaway is why it happened: Casella stopped trying to be a fast-growing roll-up and started acting like a disciplined owner of scarce, strategic infrastructure in the hardest waste market in the country.

The Moat: Why the Northeast is Different

Here’s the central insight behind Casella’s edge: the Northeast is one of the hardest places in America to run a waste business—and that difficulty is exactly what makes the incumbent so powerful.

Start with what it takes to open a new landfill. You need a huge tract of land. You need a long list of permits. You need to meet strict technical standards for liners, leachate collection, methane capture, and groundwater monitoring. And then, on top of all of that, you need the one requirement you can’t engineer your way into: community acceptance.

As suitable landfill land near growing population centers becomes harder to find, communities get pushed to consider sites farther away. At the same time, citizen opposition groups have become increasingly effective at blocking new facilities. The Not-In-My-Backyard dynamic has made siting and permitting new landfills extraordinarily difficult.

In the Northeast, every one of these hurdles gets harder.

Land scarcity. This is a dense, older region with limited undeveloped land. Any serious landfill proposal is going to be near someone’s home, someone’s drinking water, someone’s treasured open space, and someone’s property values.

Regulatory stringency. Northeastern states tend to regulate aggressively. Vermont’s Act 250—enacted in 1970—puts major development projects, including landfills, through extensive review. New permits can take a decade or more to secure.

NIMBY politics. Waste facilities have attracted intense opposition for years, and the data shows how effective that opposition has been. Slate’s Brian Palmer highlighted a steep decline in the number of waste disposal facilities in the U.S., from 7,683 sites in 1986 to 1,908 in 2009. In the Northeast—where communities are often affluent, educated, and politically active—opposition is especially fierce. Few local officials want to be remembered as the ones who approved “the new dump.”

The result is simple: new landfill permits are, for practical purposes, close to impossible to obtain. Capacity gets used up, older sites close, and replacements don’t get built. In many parts of the country, that dynamic has contributed to a real disposal crunch.

For Casella, though, that crunch is a moat. They already have what everyone else can’t get. As competitor landfills shut down and new ones don’t come online, the remaining permitted airspace becomes more and more valuable.

Casella owns, or operates under long-term agreements, nine active landfills across its footprint—from Maine through western New York and into Pennsylvania. That network matters because disposal is the bottleneck. If you control where trash ultimately goes, you influence what it costs for everyone in the region to do business. Even competitors who beat Casella on a collection contract can still end up paying Casella to dispose of the waste. As one industry line puts it: it’s a limited asset, so you can charge more for the ability to use it.

This is vertical integration at its most uncomfortable. If you’re a smaller hauler trying to compete with Casella, you immediately run into one question: where do you take the trash? You can’t just build your own landfill. It can take years to permit and costs a fortune to develop. So you bring it to a transfer station—often one Casella owns. Then it moves to the landfill—often one Casella controls. Your biggest competitor becomes your essential supplier. That’s not just an operational advantage. That’s pricing power.

And you can see it in the numbers. In 2023, unweighted average tipping fees fell in every region except the Northeast. The Northeast increased by $7.52 per ton, about 10%, rising from $75.92 to $84.44 per ton.

While tipping fees softened elsewhere, they went up in the Northeast. That isn’t a coincidence. That’s scarcity economics—playing out in real time, and turning permitted landfill capacity into something that looks less like a commodity and more like infrastructure.

Modern Era: Acquisitions & The Return to Growth (2020–Present)

With the balance sheet repaired and the strategy sharpened, Casella stepped back into M&A in the early 2020s. But this time it wasn’t the old roll-up mentality of buying anything that moved. It was targeted, methodical, and built to deepen the moat.

The new playbook was simple: - Stay in markets that overlap with, or sit right next to, existing operations - Be disciplined on price, and walk away if the returns don’t work - Only buy what the organization can actually integrate without losing its operational edge - Prioritize vertical integration—acquire assets that pull more waste into Casella-controlled transfer, recycling, and disposal

And there’s a blunt, very real competitive angle here too: when you already control key infrastructure downstream, one of the cleanest ways to reduce pressure upstream is to buy the competitor who’s creating it.

In 2021 alone, Casella acquired 10 different entities that together generated more than $88 million in annual revenue. The group included a major trash and recycling firm in Connecticut and one of Vermont’s largest compost companies.

Then came 2023—Casella’s most aggressive acquisition year since the roll-up era, but executed with post-turnaround discipline.

The GFL deal. In April 2023, Casella signed an equity purchase agreement to acquire collection, transfer, and recycling operations in Pennsylvania, Delaware, and Maryland from GFL Environmental Inc. for $525 million. The package included nine hauling operations, one transfer station, and one material recovery facility, with aggregate annualized revenues of approximately $185 million.

Casella completed the acquisition on June 30, 2023. It funded the $525 million purchase price through a combination of a new $430 million Term Loan A under its existing senior secured credit facility and proceeds from a recent equity offering.

Strategically, this mattered as much for what it signaled as for what it added. Casella was no longer just a New England incumbent—it now had a true platform in the Mid-Atlantic. These assets, which came from GFL’s acquisition of Waste Industries, gave Casella a real beachhead for expansion southward.

The Twin Bridges deal. In another major move that year, Casella completed its acquisition of New York-based Consolidated Waste Services—better known as Twin Bridges Waste & Recycling—for $219 million, closing on Sept. 1. The deal brought in two collection operations, a transfer station, and a material recovery facility in the greater Albany, New York, area. It was expected to generate about $70 million in annualized revenues.

The logic was classic Casella: deepen vertical integration in a region where landfill space is scarce and infrastructure control matters. In markets like that, owning more of the chain isn’t just margin expansion—it’s strategic leverage.

Taken together, GFL and Twin Bridges represented about $745 million of acquisition spend in 2023—roughly four times what Casella spent in 2021. That sounds like a throwback to the old days, but the rationale was different: these assets were adjacent to existing operations, the returns cleared internal thresholds, and Casella had the financial footing to absorb them.

Renewable Natural Gas. Casella’s “modern era” expansion hasn’t been limited to trucks, transfer stations, and recycling lines. It’s also leaned into the energy opportunity sitting on top of its landfills.

On July 10, 2023, Casella and Waga Energy announced a commercial agreement to develop renewable natural gas facilities at three Casella landfills. Under the agreement, Waga Energy would fund construction and own and operate the RNG infrastructure, while Casella and Waga share the revenue once the facilities are operational. Commercial operations were expected to begin in approximately 24 months, given permitting and construction timelines. Initial production across the three sites was expected to total about 1,300,000 MMBtu per year.

Once processed, the RNG would be transported by truck for injection into existing pipeline facilities. The emissions reduction from converting landfill gas into transportation fuel was estimated at 78,000 tons of greenhouse gas emissions annually—equivalent to taking more than 15,000 passenger cars off the road.

There’s an irony here that’s hard to miss. The same political and environmental forces that make it nearly impossible to permit new landfills also make existing permitted airspace more valuable. And RNG lets landfill operators monetize methane that would otherwise be flared—turning environmental credits into real cash flow.

The results, at least by management’s telling, showed the strategy working. “We finished the year strong, reporting records yet again across our key financial metrics in 2024, with growth of over 20% in revenues, Adjusted EBITDA and Adjusted Free Cash Flow,” said John W. Casella, Chairman and CEO of Casella Waste Systems, Inc. “Our consistent execution against clear operating and growth strategies have yielded consistently strong results, year after year.”

In 2025, Casella said the momentum continued: “Through the first nine months of 2025, we have completed eight acquisitions representing approximately $105 million of annualized revenue, with the pending acquisition of Mountain State Waste expected to add another $30 million. Looking forward, we have positioned ourselves to continue capturing opportunities in our robust acquisition pipeline.”

Analysis: The Playbook & Powers

To see why Casella looks less like a typical industrial company and more like essential infrastructure, it helps to run the business through a couple of classic strategy lenses.

Let’s start with Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers.

Cornered Resource (the primary power). Casella’s biggest advantage isn’t its trucks or even its customer list. It’s access to permitted landfill capacity in the Northeast—an asset that’s increasingly scarce and, for all practical purposes, impossible to recreate. Environmental regulation is strict. Community opposition is relentless. And the politics of siting “a new dump” are brutal. Casella already owns or controls legacy permits, and that puts it in the position every other player eventually finds themselves in: needing access to a limited asset that Casella can price.

Process Power. In rural Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine, efficiency isn’t about fancy software—it’s about route density and repetition. When you’re already the incumbent, you can run tight routes, keep trucks full, and spread fixed costs across more stops. For a challenger, trying to send a second truck down the same snowy back roads for a handful of customers just doesn’t pencil out.

Scale Economies. Casella is big enough to absorb shocks that wipe out smaller operators. That mattered during the recycling turmoil triggered by China’s National Sword policy. With a broader revenue base and the SRA fee structure to help manage recycling volatility, Casella had a resilience that many mom-and-pop recyclers simply didn’t.

Switching Costs. Waste isn’t glamorous, which means switching providers isn’t either. Municipal contracts often run five to ten years. For commercial customers, changing haulers means renegotiating service, swapping containers, dealing with missed pickups, and managing complaints. Once a provider is embedded, inertia is a real advantage.

Network Effects. This isn’t a classic “users attract users” business. But vertical integration creates something that rhymes with network effects: more collection volume feeds transfer and recycling, which feeds disposal, which strengthens pricing power and economics across the whole system. The pieces reinforce each other.

Now, zoom out and look at the same picture through Porter’s Five Forces.

Threat of New Entrants: virtually zero. In the Northeast, the gating factor isn’t entrepreneurship—it’s permitting and time. Bringing new disposal capacity online can take around a decade when you include site work, applications, approvals, and construction. And even after a landfill stops taking waste, the closure requirements are extensive, including final covers and caps that can run from roughly $80,000 to $500,000 per acre. That combination—time, capital, and politics—kills most would-be entrants before they begin.

Supplier Power: low. Casella buys trucks, fuel, and equipment. These are competitive, commodity-like markets, and no single supplier has much leverage.

Buyer Power: low. Every household and business produces trash. You can negotiate at the margins, but you can’t opt out of waste removal. And if Casella controls key disposal infrastructure in the region, alternatives narrow quickly—especially for competitors who still need somewhere to take the waste.

Threat of Substitutes: limited. Recycling and waste reduction help, but they don’t eliminate the need for disposal. The 2024 State of Recycling report shows that even leading states rarely push recycling rates above about 30% of waste recovery. In other words, most material still ends up needing a landfill somewhere.

Industry Rivalry: moderate to low. In Casella’s core markets, competition is constrained by geography and economics. The national giants have less presence in rural New England, and Casella’s control of disposal capacity gives it leverage even when it’s not the one winning the collection contract.

Put it all together and you get what investors often describe as the “utility” thesis. Casella provides an essential service that customers can’t avoid, in a territory where competition is structurally limited, while controlling infrastructure that takes decades to replicate. The difference from a traditional regulated utility is the key one: its rates aren’t set by a commission. If landfill capacity is scarce and demand is steady, Casella can raise prices to the extent the market will bear.

Leadership Transition: The Coletta Era Begins

On January 1, 2026—just days ago as of this writing—Edmond R. “Ned” Coletta officially stepped into the CEO role and joined Casella’s Board of Directors. It’s a milestone for the company: in fifty years, he’s only the second chief executive Casella has ever had.

Coletta isn’t new to the business. He joined Casella in December 2004 and worked his way through the roles that matter: Vice President of Finance and Investor Relations, Senior Vice President, Chief Financial Officer and Treasurer, then President and Chief Financial Officer. Before Casella, he co-founded Avedro, Inc. and served as its CFO, and earlier held a research and development engineering role at Lockheed Martin Michoud Space Systems. He holds an MBA from Dartmouth’s Tuck School of Business and a Bachelor of Science degree from Brown University.

That résumé is unusual in trash. An engineering background. An elite MBA. Startup experience. When John Casella hired him back in 2004—after that 4 a.m. ride-along on a garbage route—he was betting on an outsider who could bring discipline to an industry that often rewards brute-force growth.

Coletta justified the bet. John Casella credited him as “a driving force in our success as a company over the last 10-years,” pointing to the unglamorous work that actually changed the trajectory: resetting strategy, enforcing financial and capital discipline, building accountability across the organization, and strengthening risk management. Inside the company, he built a reputation for hard work, integrity, and a straightforward style.

John Casella, for his part, moved into the role of Executive Chairman—continuity by design, and a way to keep five decades of regulatory and political relationships in the picture. The handoff feels very Casella: planned, measured, and aligned with the same disciplined approach that powered the turnaround.

“Ned’s deep understanding of our business and his proven ability to execute make him the ideal leader for Casella’s future,” John W. Casella said. “His vision aligns perfectly with our long-term strategy to grow responsibly and lead in sustainability.”

Bear vs. Bull: The Risks and Opportunities

The Bull Case

The bull thesis rests on a few reinforcing ideas.

Continued consolidation. The Northeast is still a patchwork of local and regional operators. Casella says it sees roughly $500 million of addressable acquisition opportunities in its traditional footprint, and it believes the Mid-Atlantic expansion could roughly double that. Done well, each tuck-in deal isn’t just more revenue—it’s tighter routes, better asset utilization, and higher returns.

Pricing power. When landfill capacity shrinks in the highest-tipping-fee region in the country, the owner of disposal gets to write more of the economic rules. Casella has shown consistent mid-single-digit price growth in both collection and disposal—often a signal that it’s winning with pricing, not just volume.

Scarcity premium expansion. This is the flywheel at the heart of the story. Landfills close. Permits don’t get replaced. Remaining permitted airspace gets more valuable. That scarcity can compound over time, supporting above-market returns as long as demand stays steady and capacity stays constrained.

RNG and sustainability. Policy tailwinds like the Inflation Reduction Act, plus state-level incentives, make renewable natural gas projects increasingly compelling. For Casella, that turns landfills into more than a disposal asset—they become energy assets too, creating another stream of monetization on top of the same “hole in the ground.”

Financial performance. Management has pointed to strong recent momentum: higher net income year-over-year for the quarter, double-digit growth in Adjusted EBITDA versus the same period in 2024, and meaningful gains in operating cash flow and adjusted free cash flow year-to-date. The point isn’t the exact figures—it’s that the machine is currently throwing off more cash, which funds more investment and more disciplined M&A.

The Bear Case

But the bear case is real—and it’s not hard to sketch.

PFAS—the "forever chemicals" risk. In a 2019 analysis commissioned by the company, engineering firm Sanborn Head found PFAS in “an overwhelming number” of materials coming into the Coventry landfill. Specifically, 95% of waste samples analyzed contained PFAS, ranging from 0.043 to 2,030 parts per billion. The analysis found that 99% of the PFAS stayed within the landfill, but the remainder ended up in the leachate.

PFAS is an industrywide issue, yet it can be especially punishing in the Northeast, where regulatory scrutiny is intense. Casella’s WasteUSA landfill in Coventry accepts approximately 70% of Vermont’s trash and is a critical infrastructure asset—but managing PFAS in landfill leachate has created ongoing regulatory challenges. In February 2024, the Conservation Law Foundation reported that 9,000 gallons of leachate spilled at the Coventry facility during operation of a pilot PFAS treatment system. Casella halted the pilot project following the incident.

If regulators require costly PFAS treatment at scale—or worse, if cleanup liability expands—it could compress margins and consume capital for years. Casella is investing in treatment solutions, but the rulebook is still being written.

Valuation. Casella’s P/E ratio (TTM) is 440.88, inflated by acquisition-related depreciation and amortization. Even looking through that on an EV/EBITDA basis, the stock trades at a premium to the sector. Waste Management trades at roughly 30x P/E; Republic Services at about 31x. Waste Connections, often seen as the closest comp as a growth-oriented regional consolidator, trades at approximately 60x. A premium can be earned—but it also means the market is not leaving much room for disappointment.

Labor shortages. This is a “simple” business that’s hard to staff. Driving a trash truck through a Vermont winter is not most people’s dream job, and the industry has structural labor constraints. Casella’s response has been proactive: in 2020, it established the Kenneth A. Heir Sr. CDL Training Center, which has trained over 300 new drivers and reduced reliance on the external labor market. That helps, but labor remains a persistent headwind.

The capacity cliff. The moat is permitted airspace—and airspace is finite. The uncomfortable question is what happens in 20 to 30 years when landfills truly approach the limits. Casella can extend runway through recycling and resource recovery, but the long-term constraint doesn’t go away.

Integration risk. The post-turnaround M&A push is larger and faster than anything the company had attempted in years. Spending $745 million on acquisitions in 2023 adds scale, but it also strains integration bandwidth. On a third quarter 2025 earnings call, John Casella acknowledged lessons learned around the need for “rapid system integration” during the Mid-Atlantic expansion. If integration slips—systems, people, routes, pricing—margins can get squeezed and management focus can drift at exactly the wrong time.

Key Metrics to Watch

If you’re tracking Casella from the outside, it helps to focus on a few signals that tell you whether the story is still working—or starting to fray. Three metrics do most of the heavy lifting:

1. Solid Waste Pricing Growth. This is the cleanest read on moat and discipline. In the quarter, solid waste pricing rose 4.6% versus the same period in 2024, driven by 4.7% collection price growth and 4.6% disposal price growth. When pricing holds in the mid-single digits, it usually means the core markets are tight and the company is choosing margin over volume. If pricing starts to slip, it’s often an early warning that competition is heating up, customers are pushing back, or capacity isn’t as scarce as it looks.

2. Adjusted Free Cash Flow. This is the scoreboard. Free cash flow is what pays down debt, funds the next acquisition, and gives management room to invest without stretching the balance sheet. Casella’s adjusted free cash flow improved from $79 million in 2023 to $158.3 million in 2024, and the company expected further growth in 2025. The bigger point isn’t the exact dollar amount—it’s that cash generation is rising, which is the best proof that the post-turnaround capital discipline is real.

3. Net Leverage Ratio. This is the guardrail that keeps Casella from repeating the roll-up era. Management has targeted leverage in the 2–3x range: enough flexibility to do opportunistic M&A, not so much that a downturn turns into a crisis. As of December 31, 2022, net leverage was 2.08x. On a pro forma basis after reflecting the pending GFL acquisition and related debt, it moved to 3.59x—above the target range, but still a far cry from the near-6x levels that once boxed the company in.

Conclusion: Regional Dominance vs. National Mediocrity

Casella’s story lands on a lesson that’s easy to miss in a world that worships scale: outsized returns don’t always come from being everywhere. Sometimes they come from being unavoidable somewhere.

In the 1990s, Casella tried to play the national roll-up game. It chased growth, piled on complexity, and learned the hard way that buying revenue is not the same thing as building value. The turnaround didn’t come from a clever financial trick. It came from the discipline to say “no”—no to low-return geographies, no to non-core businesses, and no to deals that didn’t clear return hurdles.

And on the other side of that crucible, Casella came out as a different kind of waste company: vertically integrated, operationally tighter, and intensely focused on the Northeast. Not because the Northeast is easy, but because it’s hard. Permits are scarce. Communities fight new sites. Capacity doesn’t magically appear. In that environment, controlling disposal isn’t just an advantage—it’s the foundation of the moat.

Casella has argued the next wave of change will be technological too, pointing to advances in artificial intelligence and robotics that could make recycling more efficient and more broadly accessible. Whether that evolves quickly or slowly, it fits the same philosophy the company has leaned into: treat waste as a managed system, not just something to bury.

The market has rewarded that shift. Casella has climbed to all-time highs, a long way from the years when debt and bad fits left it boxed in. The same business that once looked like a roll-up cautionary tale is now a major mover of New Englanders’ garbage—and, increasingly, a gatekeeper for where that garbage can actually go.

From a single pickup truck in Rutland to the company sitting on some of the most valuable permitted landfill airspace in the country, the journey required a near-death experience, reinvention, and the stubbornness to refuse to sell at the bottom. For anyone willing to look past the “trash company” label, Casella is a case study in how regional dominance can beat national mediocrity—and how controlling a scarce resource can compound value for decades.

The shift from “Waste Management” to “Resource Management” isn’t just marketing. It’s the operating mindset: every landfill is finite, every ton is either a cost to bury or an input to recover, and the best operators are the ones who constantly look for the higher-value path.

“We’re going to be the first to cannibalize ourselves in the landfill business,” Casella says. “If we can find a higher and better use and put material through the recycling processing facility, we’ll generate more free cash flow by doing that.”

That’s the voice of a company that finally understands what it actually owns—and what it can become. And it’s a fitting capstone to fifty years of building, nearly losing, and ultimately transforming a single-truck hauling business into multi-billion-dollar essential infrastructure.

Sources & Further Reading:

For those who want to go deeper, Casella’s investor relations site includes extensive materials, including the strategic plan presentations that laid out the 2021 turnaround. Elizabeth Royte’s Garbage Land is excellent background on the waste industry more broadly. Casella’s sustainability reports provide detail on its environmental initiatives and operating metrics.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music