Cushman & Wakefield: The Story of Global Commercial Real Estate

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture this: it’s September 1, 2015. In a Chicago conference room, executives from two commercial real estate heavyweights finally put pen to paper on a deal that was about to redraw the industry map. DTZ, backed by private equity giant TPG, was buying Cushman & Wakefield for $2 billion—assembling a new contender built to go toe-to-toe with CBRE and JLL on a truly global scale.

On paper, the combined company was enormous: around $5 billion in revenue, roughly 43,000 employees, more than 4.3 billion square feet under management, and $191 billion in transaction value. But the numbers aren’t the point. The point is what that signature represented: commercial real estate services—long a local, relationship-driven craft—had fully entered the era of global platforms.

And here’s the twist that makes Cushman & Wakefield’s story so compelling: this wasn’t the company’s first ride with dealmakers and financial sponsors. It wasn’t its second. It wasn’t even its third.

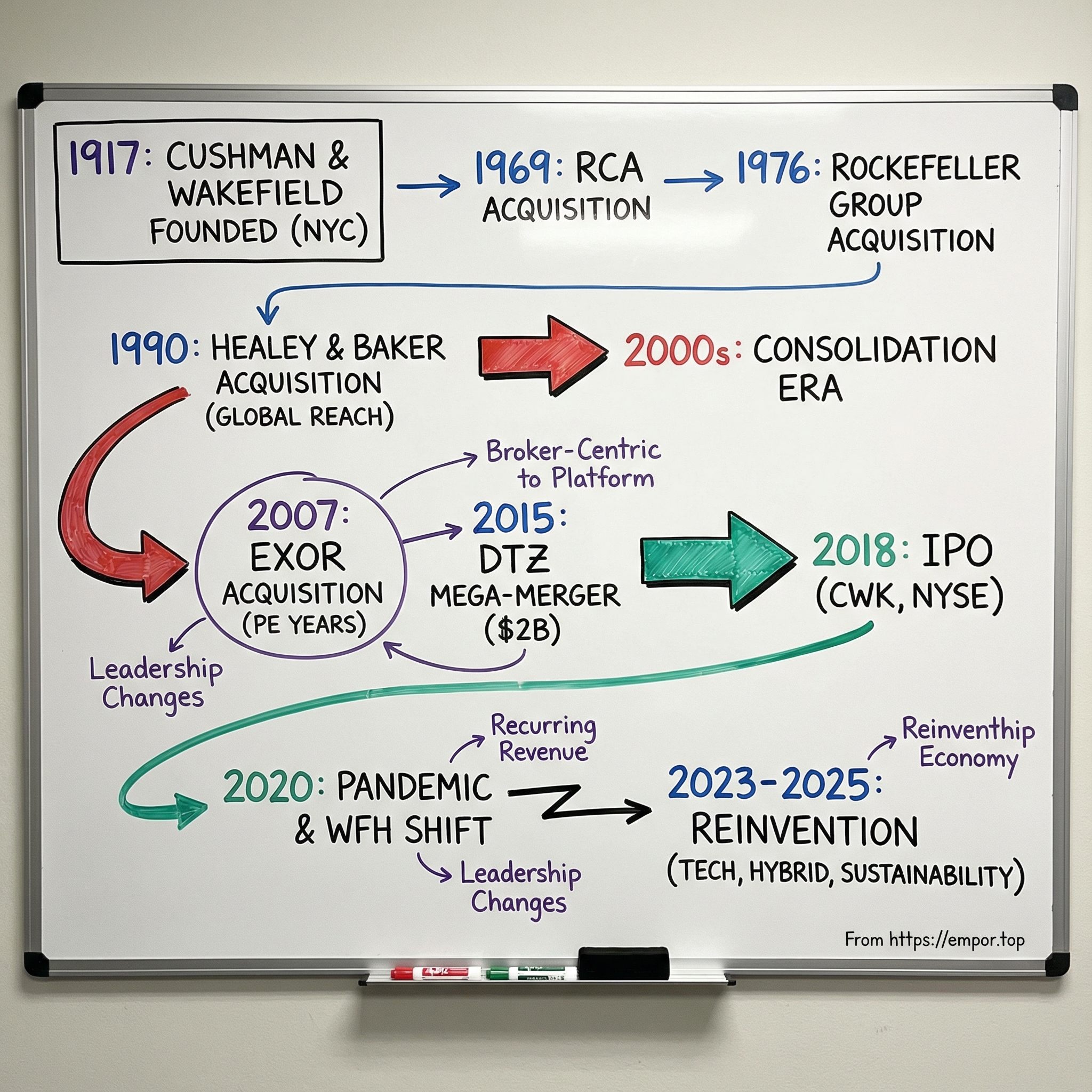

Cushman & Wakefield was founded in New York City on October 31, 1917, by brothers-in-law J. Clydesdale Cushman and Bernard Wakefield. Over the next century, it would pass through a startling lineup of owners—RCA, the Rockefeller Group, Mitsubishi Estate, the Agnelli family’s EXOR investment vehicle, and eventually TPG. Each handoff didn’t just change the cap table. It changed what the firm was, what it could be, and what it had to survive.

So how did two separate 19th- and early-20th-century firms grow up, collide, merge, get shuffled through private equity more than once, and emerge as a public company now trying to navigate the work-from-home revolution? That’s the question we’re unpacking.

At its core, Cushman & Wakefield is a commercial real estate services firm: leasing, capital markets, property and project management, valuation, analytics, and consulting—work done on behalf of occupiers, owners, and investors across offices, logistics, retail, data centers, and more. It started in 1917 as a family business in New York, and it became one of the industry’s biggest players through decades of expansion and acquisitions—culminating in that transformative DTZ combination in 2015.

Today, Cushman & Wakefield operates at true global scale, with approximately 52,000 employees across nearly 400 offices in 60 countries. In 2024, the firm reported $9.4 billion in revenue across its core lines: Services, Leasing, Capital Markets, and Valuation and other.

Along the way, we’ll follow three big themes: the consolidation wave that turned a fragmented cottage industry into a fight among global titans; the financial engineering—and near-death experiences—that kept Cushman & Wakefield in motion through boom, bust, and restructuring; and, most importantly, how the company has been forced to reinvent itself in the face of technology, hybrid work, and a deeply uncertain future for the office sector.

II. The Early Origins: Two Founding Stories (1917–1970s)

On Halloween 1917, with World War I still raging and New York City reaching skyward, two brothers-in-law quietly incorporated a small property management company. On October 31, 1917, John Clydesdale “Clyde” Cushman and Bernard Wakefield made their partnership official—built on a simple conviction that managing buildings shouldn’t be a purely gut-and-handshake business. They believed you could bring rigor to it. Process. Measurement. A more scientific approach to running modern commercial properties.

That mindset became their early differentiator. While much of real estate at the time ran on intuition and relationships alone, Cushman & Wakefield worked to systematize what “good” management looked like. Clyde even put it in writing. In 1922, he published a book titled Management: How Modern Business Buildings Are Operated, documenting the firm’s principles and helping cement its reputation as a disciplined operator, not just a well-connected broker.

It also helped that Cushman came from what you might call Manhattan real estate royalty. His family’s roots in development and property management stretched back into the 19th century with D.A. Cushman Realty Corporation. Wakefield brought complementary strengths, and together they built a firm that quickly embedded itself in the world of New York commercial property.

Cushman & Wakefield began as a property management business, and in the 1920s it became the managing and leasing agent for a roster of prominent New York buildings. The decade was a tailwind: a booming city, a construction surge, and a growing need for professionals who could run and lease increasingly complex office properties. The firm’s momentum carried into the 1930s even as the Great Depression crushed economic activity. Cushman & Wakefield kept growing, focusing in particular on Midtown Manhattan business buildings.

In 1932—right in the teeth of the Depression—the firm opened a branch office at 30 Broad Street in the downtown financial district. It was a small detail with a big signal: this was a company that expanded through downturns, not just booms.

After World War II, Cushman & Wakefield’s standing in the industry was reinforced by a landmark assignment: the 1946 land assemblage for the United Nations complex in Manhattan. It was exactly the kind of large-scale, complex transaction that separated credible operators from true institutional advisors—and it helped place the firm firmly in the commercial real estate elite.

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, a second origin story was taking shape—one that would eventually become Cushman & Wakefield’s European counterpart. In London, George Healey founded what became Healey & Baker, and George Henry Baker joined and pushed the firm toward commercial property. Over time, Baker’s name became part of the brand, and Healey & Baker developed into a significant London advisory platform.

Put those two arcs together and you can see the blueprint of the modern real estate services firm forming. The “trusted advisor” model emerged: brokerage, valuation, and property management offered together for clients who didn’t just want a deal—they wanted someone who could guide decisions, operate assets, and keep the relationship going long after a lease was signed. The economics were straightforward: commissions on transactions, fees for ongoing management, and a relationship engine that fed itself through referrals. But the real asset was always the human one. In a broker-centric business, relationships often lived with individual producers more than with the corporate brand.

In the postwar decades, that model met a massive market opportunity. Corporate America expanded, office footprints grew, and commercial real estate matured into an institutional asset class. Cushman & Wakefield responded by pushing beyond New York. In the 1960s, it began expanding nationally across the United States, opening offices in major markets and riding the era’s broad demand for office space and professionalized services.

Then came the first big ownership shift. In 1969, RCA acquired Cushman & Wakefield. Under RCA’s ownership, the firm gained access to a larger corporate ecosystem and was involved in major projects, including work connected to the development of Chicago’s Sears Tower, then the world’s tallest building. But the conglomerate era had its own gravity—exposure to big-company dynamics, and then the volatility of the 1970s.

In 1976, RCA sold Cushman & Wakefield to The Rockefeller Group, the owner and operator of Rockefeller Center in Manhattan, where RCA had housed its headquarters. It was a fitting handoff: a real estate services firm built in New York, now owned by one of New York’s most iconic real estate institutions.

And if you’re wondering why this industry stayed so fragmented for so long, it comes down to a few stubborn realities. Properties don’t move. Regulation is local. Relationships are local. And in a world where the most valuable producers can walk out the door with their clients, scale is hard to hold onto—until the economics and client needs finally force consolidation.

III. The Consolidation Era Begins (1980s–2000)

The 1980s were when commercial real estate services started to stop behaving like a neighborhood trade and began acting like a global industry. For decades, you could be the best broker in your city and have that be enough. Then corporate clients went multinational. Suddenly, “great in New York” didn’t help you much if your customer also needed London, Frankfurt, Hong Kong, and São Paulo.

Cushman & Wakefield was well positioned for this shift—but it also needed a push. Under The Rockefeller Group, the firm became more stable and more professionalized. Then, in 1989, that Rockefeller ownership base itself changed: Mitsubishi Estate Co. Ltd. became the majority shareholder in The Rockefeller Group. The timing mattered. Japanese capital was flowing aggressively into U.S. real estate, and Mitsubishi brought not just money, but a more international posture for what Cushman & Wakefield could become.

The biggest move came next. In 1990, Cushman & Wakefield established a real presence in Europe through the acquisition of Healey & Baker. This wasn’t a small bolt-on. It was the kind of step that turns a strong American firm into something that can credibly claim global reach. And the relationship deepened through the decade—culminating in September 1998, when the firm announced a merger with Healey & Baker, the 178-year-old London-based real estate company.

Cushman & Wakefield also pursued another path to scale: partnership. In 1994, it established the C&W Worldwide partnership with real estate services firms across the U.S., Europe, Asia, South America, Mexico, and Canada. The logic was straightforward—if clients were going global, your coverage had to go global too, whether you owned every office outright or not.

Meanwhile, the competitive pressure was rising fast. CBRE, JLL, and Colliers were running variations of the same playbook: buy local champions, stitch them into an international footprint (often messily), and sell the promise of one firm that could follow the client anywhere. By the end of the decade, CBRE, JLL, and Cushman & Wakefield were all widely recognized as major forces in commercial real estate—leaders across leasing, sales, and property management.

Inside Cushman & Wakefield, though, the business still ran on a very old truth: the brokers were the product. The culture stayed broker-centric, with an “eat-what-you-kill” compensation model that rewarded individual production more than institutional teamwork. Top producers earned huge commissions, carried enormous internal influence, and could walk out the door—with clients following—if they didn’t like the deal.

By 1999, the footprint looked like a global platform: 52 offices in the United States and 144 international offices through Cushman & Wakefield Worldwide across Asia, Canada, Europe, Mexico, the Middle East, South Africa, and South America.

And yet, by 2000, there was an uncomfortable reality: despite the brand, despite the expansion, Cushman & Wakefield was still widely seen as a respected but mid-tier player compared to CBRE and JLL. The gap wasn’t just size—it was momentum.

So the question heading into the new millennium wasn’t whether Cushman & Wakefield belonged in the global game. It was what it would take to stop playing catch-up.

IV. Enter Private Equity: The EXOR Years (2000–2007)

The early 2000s delivered two developments that would quietly set up Cushman & Wakefield’s next transformation: a family return, and a new model for how the firm could cover the map.

First came the homecoming. In 2001, Cushman & Wakefield acquired Cushman Realty Corporation (CRC), boosting its presence on the West Coast and in the Southwest. Just as importantly, it brought two names back into the fold: CRC founders John C. Cushman III and Louis B. Cushman—grandsons of J. Clydesdale Cushman, and grand-nephews of Bernard Wakefield. John C. Cushman became Chairman of the Board of Directors, and Louis B. Cushman became Vice Chairman.

This wasn’t just consolidation. The Cushman brothers had built a meaningful West Coast practice on their own—and now they were rejoining the firm their family had helped create eight decades earlier.

A year later, in 2002, the company launched the Cushman & Wakefield Alliance Program, designed to expand service capabilities in U.S. markets where the firm didn’t maintain owned offices. It was a pragmatic acknowledgement of the core challenge in this industry: clients wanted national coverage, even when the economics didn’t justify planting a flag everywhere.

Then came the ownership shake-up. In 2007, IFIL (now known as EXOR), the Agnelli family’s investment group, acquired roughly a 70 percent stake in Cushman & Wakefield—becoming the majority shareholder and replacing The Rockefeller Group in that role. In the same period, Cushman & Wakefield went shopping, completing a series of acquisitions including real estate investment banking firm Sonnenblick Goldman, Semco, and Alston Nock.

EXOR brought a different kind of backing: European roots, a powerful name, and the kind of capital that could support a bigger swing. The Agnelli family—best known for its control of Fiat Chrysler Automobiles—paid $565.4 million in 2007 to purchase a 67.5 percent interest, part of a broader effort to diversify beyond autos.

When EXOR took control in March 2007, Cushman & Wakefield was generating $1.5 billion in commissions and service fee revenues, with $116 million of EBITDA—about a 7.6% margin.

The playbook under EXOR was straightforward: expand globally and use the parent company’s balance sheet and connections to accelerate growth. And in 2007, it looked like perfect timing. Commercial real estate was ripping, transaction volumes were high, and optimism was everywhere.

And then the world changed.

V. The Great Financial Crisis & Private Equity Musical Chairs (2007–2014)

The 2008 financial crisis hit commercial real estate with devastating force. Lehman Brothers collapsed, credit markets froze, and the entire deal machine seized up. Transaction volumes fell off a cliff—and Cushman & Wakefield, fresh off a major ownership change, suddenly wasn’t talking about growth plans. It was talking about survival.

By 2009, the firm posted a $127 million loss. Worse, in a broker-driven business, bad years don’t just shrink revenue—they trigger exits. High-performing brokers left for competitors that could offer better economics or simply looked steadier in the storm. In retrospect, the Agnelli family’s entry couldn’t have been timed much closer to the peak. Now they were staring down a long, grinding downturn in the harshest commercial real estate environment since the Great Depression.

The irony was hard to miss. This was a firm that had endured the 1930s, weathered multiple ownership changes, and held its own through decades of intense competition. And yet here it was again, in genuine distress—hemorrhaging talent, carrying a heavy debt load, and operating in a market where deals just weren’t happening.

The turnaround began in 2010, when Glenn Rufrano—a CEO known for fixing broken situations—was brought in to run the company. He imposed operational discipline on a platform that needed it fast. The playbook was straightforward: cut costs hard, stop treating transaction fees like the only engine that mattered, and build up steadier, contract-based businesses like outsourcing and property management. He also narrowed the firm’s footprint by exiting unprofitable markets and invested selectively in technology where it could actually move the needle.

That shift toward recurring revenue mattered. In a business that can swing wildly with deal volume, property management and facilities outsourcing bring something rare: predictability. Those contracts don’t eliminate cyclicality, but they can keep the lights on when capital markets go dark. Cushman & Wakefield’s pivot in that direction would prove to be one of the most important strategic choices of the era.

EXOR, for its part, stayed supportive through the turbulence. Over its years as owner, the company expanded its presence outside the U.S. and became more diversified, and its EBITDA margin improved even in what was a brutal period for U.S.-based brokerage and services firms.

By 2014, the business had stabilized—and then some. Under CEO Ed Forst, Cushman & Wakefield delivered record results in revenues and margins that year: commissions and service fee revenues reached $2.1 billion, Adjusted EBITDA came in at $175.4 million, and the Adjusted EBITDA margin rose to 8.4%.

From the start of EXOR’s tenure to 2014, revenues grew from $1.5 billion to $2.1 billion, and margins improved from 7.6% to 8.4%. Not explosive growth, especially across eight years—but given that those eight years included the financial crisis and the recovery crawl afterward, it was real resilience.

EXOR, though, was ready to cash out. The Agnelli family had paid $565.4 million in 2007 for a 67.5 percent stake, and over time their ownership increased to 81 percent. They’d doubled down through the storm. Now, with the business back on firmer ground, it was time to monetize that bet.

VI. The DTZ Mega-Merger: Creating a Giant (2014–2015)

EXOR’s exit didn’t come through a quiet secondary sale. It came through a deal that, almost overnight, changed where Cushman & Wakefield sat on the global leaderboard.

On May 11, 2015, DTZ—a commercial real estate services firm backed by TPG, PAG Asia Capital, and the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan—agreed to buy Cushman & Wakefield for $2 billion.

To see why the combination clicked, you have to understand DTZ’s own whirlwind path to scale. DTZ traced its heritage back to predecessor firms dating to 1784. In 2011, Australia’s UGL acquired DTZ and expanded the platform’s reach across Europe and Asia. The combined business employed roughly 47,000 people, kept the DTZ name, and operated across more than 50 countries—doubling down on a brand that carried real weight in property services.

Then, just a few years later, the assets changed hands again. In 2014, UGL sold DTZ for $1.2 billion to a private equity consortium led by TPG, alongside PAG Asia Capital and Ontario Teachers’. And the new owners didn’t slow down. DTZ moved quickly to add more scale, including its acquisition of Cassidy Turley—part of an aggressive roll-up strategy designed to create a true global rival.

That set the stage for Cushman & Wakefield. The logic of the merger was simple: put two complementary footprints together and suddenly you’ve got a firm with real global coverage. Cushman & Wakefield was strongest in the Americas and Europe; DTZ brought heft in Asia-Pacific. Combined, the company would operate under the Cushman & Wakefield name, with more than $5.5 billion in revenue, over 43,000 employees, and more than 4 billion square feet under management.

For EXOR, the deal delivered the payoff after years of riding out the crisis cycle. The transaction generated net proceeds of $1.278 billion for EXOR’s 75% shareholding (on a fully diluted basis), representing a capital gain of about $722 million.

But the most important decision wasn’t just the price. It was who would run the new giant.

Brett White was tapped as Chairman and CEO of the combined company—an attention-grabbing choice, because White wasn’t just any industry executive. He’d spent 28 years at CBRE, serving as president from 2001 to 2005 and CEO from 2005 to 2012, and he’d been a board member from 1998 to 2013. Bringing in a former CBRE CEO to lead the newly expanded Cushman & Wakefield was a clear statement: this wasn’t a merger to survive. It was a merger to compete.

As White put it at the time, “While breadth and depth are important to serve clients, it’s not just about size. It’s also about local expertise and deep customer service… and ultimately what will differentiate us going forward.” He called it “a game-changing event in commercial real estate,” pointing to how both legacy firms had been aggressively expanding with acquisitions and talent.

The deal closed on September 1, 2015. DTZ as a standalone brand was retired, and everything moved forward under the iconic Cushman & Wakefield name—complete with a new logo for the combined entity.

Of course, signing the merger agreement was the easy part. The hard part was integration: blending tens of thousands of people across different cultures, unifying technology platforms, keeping brokers from getting poached during the uncertainty, and finding real cost synergies without breaking client service. In commercial real estate services, size gets you a seat at the table—but execution is what keeps you there.

Founded in 1917 in New York by brothers-in-law J. Clydesdale Cushman and Bernard Wakefield, Cushman & Wakefield brought strength to markets DTZ didn’t have—and DTZ filled in key gaps for Cushman. Together, they’d built a new number-two scale platform. Now they had to prove it could actually run like one.

VII. Going Public: The IPO Journey (2018)

Three years after the DTZ deal closed, the integration work was largely done—and the next step was the one private equity always points toward: the public markets.

On June 20, 2018, Cushman & Wakefield publicly filed its S-1 with the SEC, formally kicking off the IPO process. A few weeks later, on August 2, the stock began trading on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker CWK. The company priced the offering at $17 per share, selling 45 million shares and raising roughly three-quarters of a billion dollars. On day one, the stock popped—up as much as 7% intraday—and finished at $17.81.

The pitch was clean and familiar: Cushman & Wakefield was now the number-two global player, with real scale, a diversified mix across leasing, capital markets, outsourcing, valuation, and property management, and a growing base of recurring revenue that could smooth out the industry’s brutal cycles.

But the prospectus told a less comforting story in the fine print. As of March 2018, Cushman & Wakefield carried about $3.1 billion of debt—up roughly $300 million from the end of 2017. The Financial Times flagged the leverage as a central risk factor, and skeptics latched onto it: the IPO implied an equity value of around $3 billion, but the balance sheet still had billions of debt sitting beside it.

And profitability wasn’t yet a victory lap, either. Costs and expenses had risen faster than fee revenue, and the company posted a net loss of just over $124 million for the first half of 2018, albeit improved from the prior year. Management and industry watchers pointed to the obvious culprit: the expensive, multi-year process of stitching together two massive organizations—integrating offices, systems, and teams.

Investors, though, didn’t want explanations. They wanted proof. In the months after the IPO, the stock slipped below its $17 offering price. With TPG retaining majority control, governance questions lingered too.

The market’s message was blunt: the merger story was over. Now show that this platform can reliably produce profits.

VIII. Navigating Disruption: PropTech, WeWork, & Changing Clients (2018–2020)

If the market’s message after the IPO was “prove it,” the late 2010s made that job harder. Commercial real estate services was suddenly getting squeezed from multiple directions: new technology players promising to “unbundle” the broker, a handful of mega-clients changing how space was used, and an economy that was quietly rewiring which property types mattered most.

First came PropTech. Startups like VTS, Hightower, and Comfy raised huge sums and went after the industry’s soft underbelly: messy workflows, opaque data, and processes still built around relationships, phone calls, and spreadsheets. Their pitch was simple. Make leasing and portfolio management run like modern software. Give clients better visibility. Strip out friction. And, in the most threatening version of the story, eventually strip out the middleman.

Then there was WeWork—both rocket fuel and a warning label. WeWork became one of Cushman & Wakefield’s largest clients, generating major leasing volume and transaction fees. But when WeWork’s story cracked in 2019, it did more than embarrass a high-flying tenant. It reminded the entire industry that “new models” don’t repeal the old rules of real estate: leverage, cycles, and what happens when growth assumptions collide with reality.

At the same time, the Amazon effect was reshaping the map. Retail properties—from malls to shopping centers—were getting hammered. Industrial and logistics, meanwhile, were surging as e-commerce fulfillment became mission-critical infrastructure. Cushman & Wakefield’s breadth across property types helped, but there was no escaping the larger anxiety creeping into the system: the office sector, still the industry’s marquee category and a core revenue engine for major firms, was starting to face more serious questions about long-term demand.

Inside Cushman & Wakefield, the response wasn’t to pretend it could out-software Silicon Valley. Brett White’s mantra was “operate, integrate, innovate”—get the post-merger machine running smoothly, finish the hard integration work, and then place smart bets on technology and new capabilities. The firm could build some tools, but it also needed partnerships, selective investments, and faster adoption of platforms that clients were starting to expect as table stakes.

And the competitive pressure wasn’t letting up. CBRE and JLL—the two giants Cushman & Wakefield was trying to match—were investing heavily in technology and consistently posting stronger operating performance. Beneath them, hungry competitors like Newmark and Colliers kept taking swings. Specialists, too, were carving out niches and winning mandates in targeted verticals where expertise mattered more than global scale.

Underneath all of that sat the real challenge: culture. Commercial real estate had always been broker-centric, an “eat-what-you-kill” world where the best producers held real power and could take relationships with them. But the future clients were pointing toward looked more platform-centric—where data, tools, and institutional capabilities mattered as much as individual rainmakers. Cushman & Wakefield wasn’t alone in trying to make that shift. But like the rest of the industry, it was learning that changing the operating system of a relationship business is a lot harder than buying another firm.

IX. The Pandemic & The Work-From-Home Earthquake (2020–2022)

In March 2020, the world shut down. Offices emptied almost overnight. And for commercial real estate services firms, an uncomfortable question went from abstract to urgent: what happens to your business if nobody needs an office?

COVID-19 spread rapidly through the first half of 2020, and the global economy flipped from expansion to contraction in a matter of months. For a company like Cushman & Wakefield—where leasing and capital markets thrive on movement—the initial shock was brutal. Transaction activity froze. Leasing slowed to a crawl. Investment sales stalled. The stock fell below $10, more than 40% below its IPO price. Layoffs and cost reductions followed.

Cushman & Wakefield tried to put a frame around the chaos. It released its first-ever Global Office Impact Study, projecting that office leasing fundamentals would be hit hard by the COVID-19 recession and the work-from-home trend, but would begin improving in 2022 and recover fully two to three years after that—similar to the Great Recession, but with a longer tail because this time the demand shock wasn’t just financial. It was behavioral.

Then the company’s earlier strategic pivot started to matter. When transactions disappear, transactional revenue disappears with them. But property management and outsourcing don’t work that way. Those contracts kept producing cash flow even while the deal machine was stalled. The unglamorous, recurring parts of the business became the lifeline through the darkest stretch.

Cushman & Wakefield also went on offense with new services built for a world thinking about airflow and elbow room. Workplace safety consulting became a real offering. The firm leaned into space-planning and redesign—helping clients reopen safely and, just as importantly, figure out what “the office” was supposed to be for in a hybrid world.

“Our clients are very interested in new workplace strategies that align with the science at the forefront of the fight against COVID-19,” said Despina Katsikakis, Head of Workplace Business Performance at Cushman & Wakefield. “We’re pleased to expand on our 6 Feet Office prototype with further testing in areas like advanced air filtration and surface hygiene technologies.”

The “6 Feet Office” became the signature product of that moment: part design concept, part consulting package, and part signal to clients that the firm could help them navigate the new rules of work.

This was also when leadership began to shift. In early April 2020, Cushman & Wakefield announced that Michelle M. MacKay would join as Chief Operating Officer, stepping down from the board to take the newly created role. She brought a finance-and-operations profile to a company that needed both. Before joining, she’d served as a Senior Advisor to iStar, and during her 15 years there held roles including Executive Vice President of Investments and Head of Capital Markets—helping grow the company from $6 billion to $16 billion.

From the outside, it looked like a standard executive hire. Inside, it was more like succession planning under pressure. MacKay later described a clear trajectory: when CEO Brett White asked her to consider becoming CFO, she declined. Instead, she agreed to become COO in 2020 with a path to the CEO role in July 2023.

By 2021 and 2022, the recovery arrived—but it didn’t feel smooth. It felt like whiplash. Transaction volumes came roaring back as pent-up demand was released. M&A across commercial real estate accelerated, creating fresh advisory work. And yet the existential question never fully left: even if deals return, what does long-term office demand look like now that work-from-home is proven?

As the market reset, Cushman & Wakefield’s leadership baton moved again. Brett White, who led the firm through the DTZ combination, the IPO, and the early pandemic period, transitioned out of the CEO seat in 2021 and became executive chairman. In January 2022, longtime company president John Forrester, based in London, became CEO. Forrester served as CEO for about a year and a half before being succeeded by Michelle MacKay on July 1, 2023.

The company had survived the shock. Now it had to lead through the aftershocks.

X. The Present & Recent Inflection Points (2023–2025)

As the pandemic faded into the background, commercial real estate ran into its next shock—this time from the Federal Reserve. In 2022 and 2023, rates rose fast as the Fed fought inflation. Higher borrowing costs didn’t just slow deals; they rewrote valuations. And nowhere was the damage more visible than in offices.

Vacancy became the headline. In one snapshot from that period, roughly 21% of office space sat empty—versus 8.7% for multifamily—while shopping centers and industrial looked comparatively healthy, with vacancy around the mid-single digits. By 2024, the picture was still unsettled. In July, office vacancy was reported at a record 13.8%, retail and industrial fundamentals were softening, and apartment demand was surging. Other measures were even bleaker: CBRE pegged U.S. office vacancy at 19% in the first quarter of 2024, a level that pushed past the highs of both the Great Recession and the COVID-era shock.

What emerged wasn’t just “office is down.” It was a split-screen market.

The flight to quality became unmistakable. Class A buildings—vacancy around 7.9%—held up far better as companies tried to lure employees back with newer space and amenity-rich campuses. Class B and C buildings, with vacancies of 14.5% and 23.4%, were left holding the bag, facing an ugly combination of maturing loans and weak values.

Against that backdrop, Cushman & Wakefield made its leadership transition official. The firm named longtime executive Michelle MacKay to succeed CEO John Forrester, who announced his retirement. Forrester—at the company for 35 years and CEO since 2022—stepped down on June 30, and MacKay, then the COO, took over as chief executive on July 1.

In her tenure, the story the company wanted investors to see was resilience and momentum, even in a distorted market. “We closed out 2024 with strong momentum in our business, reporting another quarter of solid Leasing revenue, our strongest Capital markets growth since the first quarter of 2022 and robust year-over-year improvement in free cash flow,” MacKay said. “We begin 2025 with renewed optimism, as investor and occupier sentiment continues to improve, and we have positioned ourselves to thrive in what we believe will be a multi-year commercial real estate growth cycle.”

The top line was broadly steady. Cushman & Wakefield reported $9.4 billion of revenue for the year ended December 31, 2024, down about $47 million from 2023. Within that, Leasing revenue grew 7%, driven by office and industrial leasing in the Americas and APAC. Capital markets revenue rose 4%, with strength across industrial, retail, and office, and across all segments.

By 2025, management pointed to a clearer upswing. In the third quarter of 2025, the company reported 9% service line fee revenue growth, its fourth consecutive quarter of double-digit Capital markets revenue growth, and organic Services revenue growth accelerating to 7%. After what it called record third-quarter cash flow generation, the company prepaid an additional $100 million in debt, bringing two-year cumulative debt prepayments to $500 million.

MacKay added that since becoming CEO in July 2023, Cushman & Wakefield had paid down $230 million in debt and refinanced and repriced its debt five times to reduce annual cash interest burden. She also noted a $25 million debt paydown in the first quarter of 2025.

The stock reflected some of that improved tone. Cushman & Wakefield’s closing price as of December 24, 2025 was 16.53, compared with an all-time high closing price of 23.12 on February 16, 2022. More recently, shares traded in a day range of 15.41 to 15.74, with a 52-week range of 7.64 to 17.33.

Underneath the quarterly swings, MacKay framed the shift as more fundamental than a cycle. “What I think people don't understand is we're growing a different kind of engine, a different kind of company, and a different kind of culture that's far more tapped into where the world is going and far less reliant on historical practices of where the world has been.”

Part of that “different engine” was technology. Strategic investments accelerated, with MacKay emphasizing the push to build “a global capital markets platform, not a U.S. institutional platform,” while continuing to invest in AI and data infrastructure.

And sustainability moved from marketing to mandate—and increasingly, to revenue. As the firm put it in its 2024 Sustainability Report: “Our 2024 Sustainability Report reflects the strides we've made toward reducing our carbon footprint, enhancing energy efficiency and fostering communities that thrive. We are particularly proud to have achieved our 2030 emissions reduction target for Scope 1 and 2 emissions six years ahead of schedule—a clear indication of the meaningful progress we are making.”

XI. Business Model Deep Dive & Competitive Moat

To understand Cushman & Wakefield, you have to understand the economics of commercial real estate services. This isn’t a company that sells a product off a shelf. It sells expertise, relationships, and execution—and it gets paid in a few very different ways, depending on the work.

Leasing is the classic brokerage engine: representing tenants hunting for space and landlords trying to fill it. It’s transactional, intensely competitive, and highly cyclical. When companies are expanding, moving, or upgrading space, leasing fees flow. When uncertainty hits, decisions get delayed—and revenue drops fast.

Capital Markets is the buy/sell/finance side of the house: investment sales and debt placement. In good times, it can be the most lucrative line of business. In bad times, it can go quiet almost overnight, because it’s extremely sensitive to interest rates and investor sentiment.

Valuation & Advisory is the steadier counterweight—appraisals and consulting work that tends to keep moving even when the deal machine slows. It doesn’t have the same upside as a hot capital markets cycle, but it provides ballast.

Property Management is exactly what it sounds like: operating buildings on behalf of owners. It’s recurring and predictable, but typically lower margin—more like operational infrastructure than a commission windfall.

Outsourcing and Facilities Management takes that idea further: instead of managing a single building, you manage entire real estate portfolios for corporate clients. This is where scale really matters. These contracts are often stickier, and strategically they’re a big deal because they turn a cyclical, transaction-heavy firm into something more annuity-like.

Investment Management is the firm running real estate funds—earning management fees and, when performance allows, carried interest.

But here’s the structural reality that shapes everything: this is still a broker-driven business. Broker compensation can consume roughly 50–60% of revenue. In other words, top producers generate the revenue—and then split a big portion of it with the firm. That dynamic is great for attracting and retaining talent, but it puts a natural ceiling on margins, even as you get bigger.

On top of that, you have a meaningful fixed-cost base: technology, back office, compliance, and corporate overhead. So scale helps—but not in a clean, software-like way. The main scale advantages come from global coverage, brand credibility, and the ability to spread technology investment across a very large revenue base.

And that brings us to why this business is so hard.

First, talent retention. Brokers can leave, and clients can follow. In many cases, the relationship isn’t owned by the institution; it’s carried in someone’s phone.

Second, cyclicality. Transaction volumes can swing dramatically with the economy and capital markets, and when they swing down, they swing down hard.

Third, local market knowledge. Real estate is deeply local—regulation, pricing, inventory, and relationships vary block by block. You can’t just “deploy” into a market and expect credibility.

Fourth, technology disruption. Platforms can streamline workflows, improve transparency, and potentially disintermediate pieces of the traditional brokerage value chain. That threat doesn’t mean the broker disappears—but it does mean parts of the service can become more standardized, and therefore more price-competitive.

So what’s the moat?

It’s complicated. Network effects are limited—one client using Cushman doesn’t inherently make the service better for another client. Switching costs are mixed: outsourcing and facilities contracts can be sticky and painful to replace, while brokerage relationships are more portable. Brand matters, especially for trust and recruiting, but individual broker brands can matter even more. Scale helps—in coverage and in funding technology—but it doesn’t create a winner-take-all dynamic.

The prize is clear: keep growing the recurring businesses with higher switching costs, like outsourcing and property management. The risk is just as clear: transactional services get commoditized, and technology keeps pressuring the value of what used to be hard-to-replicate expertise.

XII. Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

If you want the simplest explanation for why Cushman & Wakefield has always had to fight for every inch of margin, it’s this: there are a lot of capable competitors, and the product is hard to differentiate.

At the top of the market, the same names keep showing up—CBRE, JLL, and Cushman & Wakefield—huge global platforms with real brand gravity and the ability to service multinational clients. But they’re not competing in a tidy oligopoly. This industry is still crowded: the “Big Five” (CBRE, JLL, Cushman & Wakefield, Colliers, Newmark) are surrounded by thousands of local and regional firms that can win business on relationships, specialization, or price.

And in core brokerage, the uncomfortable truth is that the service can look similar from the outside. One team’s pitch can sound a lot like another’s. When services start to feel commoditized, pricing gets pressured, and competition turns into a constant knife fight. Add meaningful fixed costs—offices, systems, compliance, corporate infrastructure—and the incentive is always to keep the machine fed, even if it means competing more aggressively.

Threat of New Entrants: MODERATE

At the local level, barriers to entry are low. A small group of experienced brokers can leave a big firm, start a boutique, and compete almost immediately—especially if they bring relationships with them.

But building something truly global is a different game. A worldwide platform takes decades, acquisitions, infrastructure, and a brand clients trust in dozens of markets. Cushman & Wakefield didn’t get there quickly; it took more than a century and multiple ownership eras to assemble its footprint. Technology is also changing the entry story—PropTech startups can attack specific slices of the workflow—but incumbents are responding, adopting tools, and narrowing the advantage new players might have.

Supplier Power: MODERATE-HIGH

In this business, the suppliers aren’t raw materials. They’re people—brokers, deal teams, and specialized experts. And the best ones have leverage.

Top producers can often walk out the door and bring clients with them, because relationships can be more personal than institutional. That portability is a structural vulnerability for every firm in the sector, including Cushman & Wakefield.

There are a few ways companies try to blunt that power: building team-based coverage so a relationship isn’t held by one person, investing in platform support and technology that makes it harder to replicate the experience elsewhere, and using equity compensation to give people a reason to stay. But the core reality remains: talent has options.

Buyer Power: MODERATE-HIGH

Many of the biggest customers—large corporates, institutional owners, major investors—know exactly what they’re buying and what it should cost. They can run competitive RFP processes, push on fees, and treat parts of the service like a commodity.

Switching costs in brokerage are often low. If a client wants to change firms, they usually can. What creates protection is everything that’s harder to swap out: deep specialized expertise, long-standing trusted-advisor relationships, and especially outsourcing and facilities management contracts, where operational integration makes switching painful and risky.

Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE-GROWING

The substitute threat isn’t one thing—it’s a handful of forces slowly eating at the edges.

Technology platforms can streamline steps that once required a broker or advisor. Some large companies build in-house real estate teams and rely less on outside firms. In some cases, landlords and tenants can connect directly and bypass intermediaries. AI and better data can also reduce the amount of “pure advisory” work needed for certain decisions.

But the other side of the ledger still matters: large transactions are complex, negotiated, and often relationship-driven. When the stakes are high, clients still tend to want experienced humans in the middle.

Overall Industry Attractiveness: Moderate—leaders can make good money at scale, but relentless competition keeps returns from getting too comfortable.

XIII. Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: MODERATE

Cushman & Wakefield does get real benefits from size: technology spend, compliance, and back-office costs can be spread across a bigger revenue base, and broad geographic coverage makes it easier to win and retain global clients. But there’s a hard cap on how much scale turns into margin. In a broker-driven model, a large share of every dollar still goes back to the producers who generated it.

Network Effects: WEAK

There isn’t much in the way of classic network effects here. One client using Cushman & Wakefield doesn’t automatically make the service more valuable for the next client. The closest thing is data: more transactions can mean better comps and sharper market intelligence. But those data flywheels are still early, and the industry isn’t a winner-take-most game.

Counter-Positioning: LIMITED

PropTech startups tried to counter-position with technology-first models—faster, cleaner workflows, and more transparency than legacy brokerage. But the big firms didn’t stand still. As incumbents adopted the same tools and partnered where it made sense, the asymmetry narrowed. And true business model reinvention remains difficult when compensation and culture are anchored around individual production.

Switching Costs: MODERATE

Switching costs depend on what you’re buying. In outsourcing and property management, they can be high—changing providers can disrupt operations and unwind years of embedded processes and relationships. In brokerage, switching costs are often low because relationships are portable. In investment management, switching is possible but more nuanced: performance matters, and reallocations happen, but not lightly.

Branding: MODERATE

Cushman & Wakefield benefits from being a globally recognized name, with a long track record and a broad service portfolio that supports cross-selling. Its international footprint also matters when multinational clients want one firm across markets. But brand power has a ceiling in this business. Clients often don’t say they work with Cushman & Wakefield; they say they work with a specific broker at Cushman & Wakefield.

Cornered Resource: WEAK-MODERATE

Talent can function like a cornered resource—top brokers and specialist teams are scarce and valuable. But portability limits how “cornered” it really is, because those people can leave and relationships can move with them. Proprietary data is becoming more important, but it’s not fully defensible yet. Local advantages can exist through key relationships, like exclusive landlord assignments, though true geographic exclusives are rare.

Process Power: MODERATE

Process is where a big platform can quietly build an edge. Strong execution in property management and outsourcing can separate firms that merely win mandates from firms that keep them. Years of acquisition integration have also built institutional muscle around combining teams and systems. And a unified technology platform could become a real advantage over time. Still, none of this is unique—competitors have developed similar operational capabilities.

Overall Power Position: MODERATE

Put it together and you get a company with meaningful scale and pockets of stickiness—but no single, dominant power that lets it relax. Cushman & Wakefield has to keep executing to hold its position. The upside is clear: expand the recurring, higher-switching-cost lines of business. The danger is just as clear: transactional services get commoditized, and the fight for talent and share never lets up.

XIV. Bull vs. Bear Case

The Bull Case:

Office rebounds more than expected. Hybrid work settles into something stable, and the best offices stay valuable because they solve the hard problems: collaboration, culture, and recruiting. In that world, the flight to quality keeps rewarding Class A buildings with amenities.

Diversification wins. Even if traditional office is messy, other property types don’t have to be. Industrial, life sciences, and data centers keep growing, and a broad footprint across the Americas, EMEA, and APAC smooths out the cycle.

Recurring revenue reaches critical mass. Outsourcing and property management keep climbing toward, or even past, half of total revenue—making the company less dependent on whether the deal machine is on or off.

Technology investments pay off. Years of spending finally show up where it counts: better broker productivity, better client outcomes, and a platform that’s harder to replicate than “a good team with a phone.”

Market share gains accelerate. If markets stay tough, smaller and undercapitalized competitors struggle, consolidation continues, and Cushman & Wakefield picks up talent and accounts.

Margin expansion materializes. With integration synergies fully realized, profitability finally starts closing the gap with CBRE and JLL.

Debt reduction continues. After record third-quarter cash flow generation, the company prepaid an additional $100 million in debt, bringing two-year cumulative debt prepayments to $500 million. Less leverage means more flexibility—and less risk when the cycle turns.

Valuation gap closes. If execution improves and leverage falls, the stock’s discount to CBRE and JLL could narrow as investors gain confidence that the model is working.

Sustainability services boom. ESG compliance and net-zero consulting stop being “nice-to-have” projects and become required work—and a meaningful growth engine.

The Bear Case:

Structural office decline persists. Remote and hybrid work permanently shrink office demand, and the industry is left with too much space and too many middle-of-the-road buildings fighting for too few tenants.

Margin pressure continues. The business stays stuck in a knife fight on fees, and the broker compensation model keeps a hard ceiling on how much scale can translate into profits.

Technology disrupts faster than expected. PropTech platforms chip away at brokerage and advisory, and AI makes market data more accessible—reducing the advantage that used to come from proprietary insight and experience.

Talent flight accelerates. Top brokers move to competitors or boutiques that offer better economics, more autonomy, or a brand that feels more stable.

Economic recession hits. Transaction volumes fall sharply, and even a larger base of recurring revenue can’t fully offset the hit.

Commercial real estate crisis deepens. Defaults in the office sector spread stress through owners, lenders, and transaction markets—dragging out the downturn and keeping activity muted for longer.

Commoditization accelerates. As data and tools become cheaper and more standardized, advisory work becomes more price-competitive, squeezing margins.

Private equity overhang. TPG and other PE investors’ eventual exits weigh on the stock, limiting upside even when operations improve.

What to Watch—Key Performance Indicators:

Two metrics matter most for tracking Cushman & Wakefield’s trajectory:

-

Recurring Revenue as Percentage of Total Revenue: The north star is 50% or higher. The closer the mix gets to that level, the less the company lives and dies by capital markets and leasing cycles.

-

Adjusted EBITDA Margin vs. Competitors: Watch whether the firm can close the gap with CBRE and JLL. In 2024, Adjusted EBITDA was $581.9 million, up $11.8 million from 2023, and the Adjusted EBITDA margin measured against service line fee revenue was 8.8%, relatively flat year over year. Sustained margin improvement is the clearest signal that integration and operating discipline are translating into real performance.

XV. Lessons & Takeaways: The Playbook

For Founders & Operators:

Cushman & Wakefield’s story is a reminder that in professional services, the “product” is trust—earned over years, tested in months, and lost in days. The playbook here isn’t about a single brilliant strategy. It’s about surviving enough cycles to keep earning the right to play.

Surviving financial engineering: Few companies get bought and sold as many times as Cushman & Wakefield did and still come out intact. It lived through private equity handoffs, heavy leverage, and the 2008 crisis. What kept it together wasn’t fancy financial structuring—it was holding onto client relationships and keeping top talent from walking out the door when uncertainty spiked.

Integration is everything: The DTZ merger created scale quickly, but scale is the easy part. Integration is where deals succeed or die. Cultures collide. Systems don’t connect. Competitors circle your best brokers while everyone’s distracted. The takeaway is simple: never underestimate how long it takes to turn “combined” into “one company.”

Recurring revenue is king: The pivot toward property management and outsourcing didn’t look glamorous when capital markets were roaring. Then COVID hit, transactions vanished, and those recurring contracts helped keep the business standing. If your revenue depends on the deal machine being on, you need another engine for when it’s off.

Technology adoption requires balance: Real estate is full of tools that look great in a demo and die in practice. Move too fast and producers feel threatened. Move too slow and clients decide you’re behind the times. The winning approach is technology that makes brokers and teams more effective without trying to replace the relationship at the center of the business.

Talent-dependent businesses are fragile: In this model, the value walks out the door every night. Compensation, culture, and tools aren’t HR issues—they are existential strategy. Lose the people, lose the clients.

Diversification provides portfolio effect: Geography and service-line breadth aren’t just growth stories. They’re shock absorbers. Different markets and property types move at different speeds, and a diversified platform can stay steadier when one part of the map—or one asset class—falls apart.

For Investors:

Be wary of leveraged IPOs: When a private equity-backed company comes public with a lot of debt, you’re not buying a clean slate—you’re buying a capital structure. And PE sponsors’ timelines and incentives don’t always match what public shareholders want.

Industry structure matters: Commercial real estate services is brutally competitive and still fragmented. Even leaders with scale fight for share, fight for talent, and fight to defend fees.

Cyclicality is real: These firms are tied to the economy, interest rates, and sentiment. When confidence disappears, transactions disappear with it. Don’t confuse a strong market cycle with a permanent improvement in the underlying business.

Moats are hard to assess: Scale helps, but it doesn’t guarantee pricing power. Brand matters, but relationships often matter more. In industries like this, “advantages” can be real and still not show up as outsized returns.

Structural trends trump cycles: Work-from-home didn’t just dent demand—it changed the conversation. Betting on a return to normal means betting on office demand finding a durable new equilibrium.

Valuation gaps exist for reasons: Cushman & Wakefield has often traded at a discount to CBRE and JLL. That’s not an accident—it reflects leverage, execution risk, and margin gaps. Closing it requires consistent performance over time, not a single good quarter.

The Bigger Picture:

Commercial real estate services is a case study in modern professional services competition: technology is reshaping workflows and raising expectations, but it hasn’t eliminated the need for experienced judgment and human relationships.

Cushman & Wakefield’s story, in the end, is a survival story—through the Great Depression, the 2008 financial crisis, COVID-19, and an office market still searching for its next stable form. A century later, the lesson is the same one the founders implicitly understood in 1917: in real estate, the environment always changes. The firms that endure are the ones built to adapt.

XVI. Epilogue: The Road Ahead

The post-pandemic commercial real estate landscape doesn’t just feel different. It is different. Hybrid work isn’t a temporary policy anymore; it’s turning into a permanent operating model. So the question isn’t “will offices survive?” The question is what the office is for now—and how much of it companies are actually willing to pay for.

That uncertainty has a real price tag. Moody’s economists Tom LaSalvia and Todd Metcalfe warned that rising vacancies could erode commercial property values by as much as $250 billion by 2026. Their logic is painfully simple: for many industries, work-from-home hasn’t clearly crushed productivity (even if the research is mixed). And if output doesn’t meaningfully fall, companies have less incentive to return to old office habits—especially when reducing footprints can mean immediate savings.

At the same time, the toolset of the industry is changing fast. AI is pushing into everything from valuations to research to lease language. VR and AR have the potential to change how space is marketed and toured. Blockchain still sits mostly in the “someday” bucket, but the idea is seductive: fewer frictions, cleaner records, faster transactions. The open question is whether these technologies finally disintermediate parts of the business—or mostly become amplifiers that the big platforms, with their data and distribution, can use to get even stronger.

Then there’s the biggest structural shift of all: climate and sustainability. Net-zero isn’t a slogan when tenants, regulators, and capital markets start treating it like a requirement. Climate risk analysis is becoming part of underwriting. ESG reporting is increasingly tied to financing and value. For a services firm, that’s both disruption and opportunity: the rules of value creation are changing, and clients need help navigating the transition.

And underneath all of it is a generational transition that’s easy to understate but impossible to ignore. Millennials are now the largest share of the workforce. They want different workplace experiences, different flexibility, and different trade-offs between commute, cost, and culture. If you’re advising occupiers and landlords, understanding those preferences isn’t a “future trend.” It’s the demand curve.

As Michelle MacKay put it: “What I think people don't understand is we're growing a different kind of engine, a different kind of company and a different kind of culture that's far more tapped into where the world is going, and far less reliant on historical practices of where the world has been and when we were talking about talent. This is a complete tie out to the kind of talent that we want too. We don't want people who are going to tell us the way that it was done. We want visionaries to come to us thinking about the way it's going to be done.”

For Cushman & Wakefield, that’s the bet—and the test. The DTZ integration is largely behind it. The leadership transition is done. The company has been paying down debt. Now the work is execution: can this platform consistently convert scale into margins and returns that actually close the gap with its top competitors?

After more than a century—from a small New York property management firm founded by brothers-in-law, through ownership by RCA and the Rockefellers, European expansion via Healey & Baker, control by the Agnellis, private equity reshaping, an IPO, a pandemic, and the work-from-home earthquake—Cushman & Wakefield is still standing. The buildings it helps buy, sell, lease, and manage may look very different in the decades ahead. But the need for real estate expertise—grounded in local knowledge and delivered at global scale—hasn’t gone away.

The firm that J. Clydesdale Cushman and Bernard Wakefield founded in 1917 with a belief in “scientific methodology” is still doing the same thing at its core: bringing rigor to a messy, human, high-stakes business. The methods keep changing. The mission, so far, has endured.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music