Carvana: The Digital Used Car Revolution That Almost Died

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

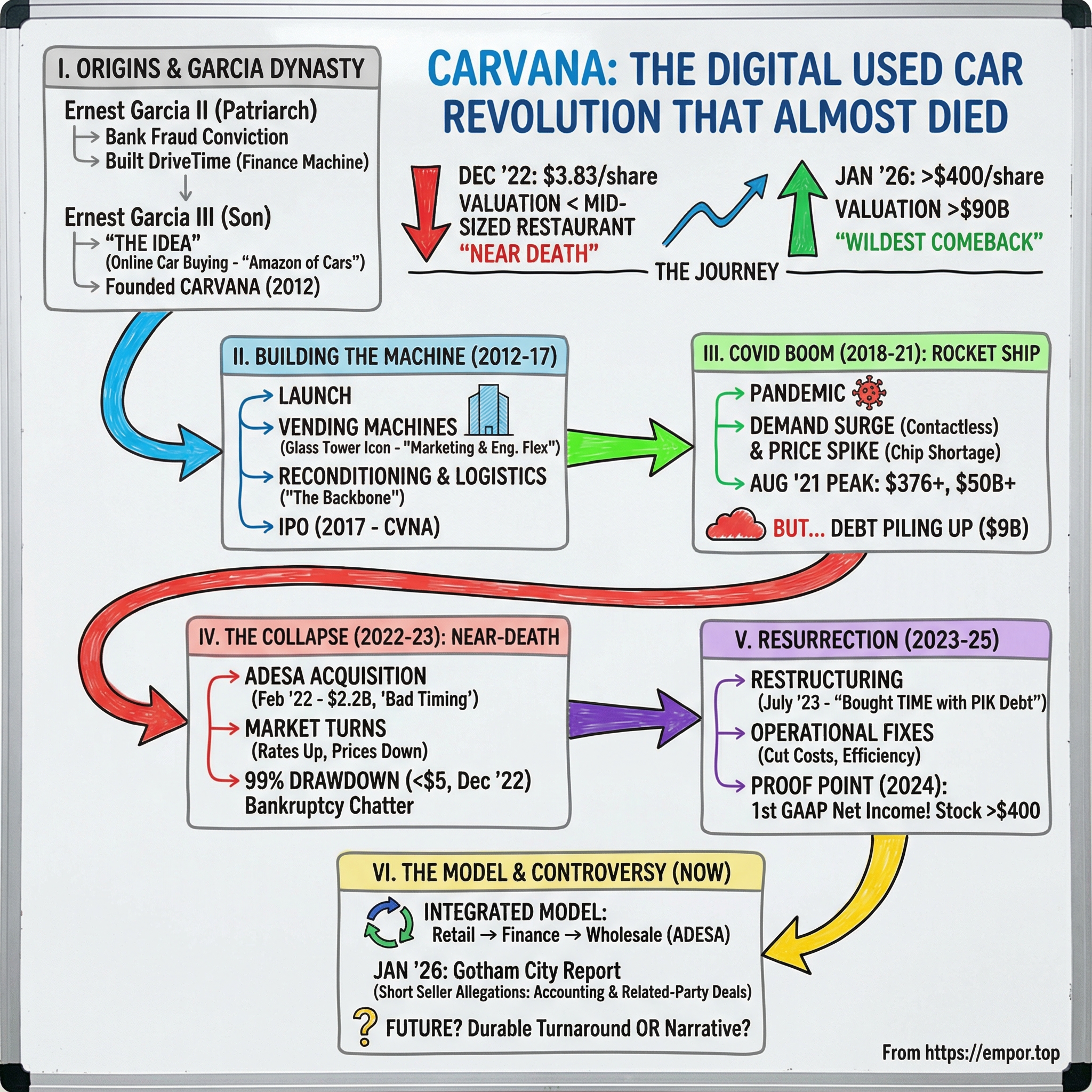

In December 2022, Carvana’s stock hit $3.83. Not thirty-eight dollars. Three dollars and eighty-three cents.

Eighteen months earlier, this was a company the market had crowned at more than $50 billion. Now it was worth less than a mid-sized restaurant group. The Wall Street Journal was publishing post-mortems. Wedbush put a one-dollar price target on it—analyst-speak for, “this might go to zero.” Bankruptcy chatter was everywhere. The verdict seemed in: Carvana, the online used-car dealer with the glass car-vending machines, was a pandemic hallucination. And the hangover had arrived.

Now jump to January 2026. Carvana is trading above $400 a share, with a market cap that has, at times, topped $90 billion. It sold more than 400,000 cars in 2024, reported its first full year of GAAP net income, and has been folding in a giant network of physical auction sites that could dramatically expand its reconditioning footprint. By almost any standard, it’s one of the wildest corporate comebacks in recent American business.

But this isn’t a neat redemption arc.

It’s a father-and-son story, with a family patriarch who has a bank-fraud conviction and restrictions that kept him from holding leadership roles at a public company. It’s a story about vending machines that are equal parts engineering flex and marketing bait. It’s a story about mountains of debt, a restructuring many observers called “tantamount to default,” and a web of related businesses that still makes governance questions impossible to ignore.

Even now, the controversy hasn’t faded. On January 28, 2026, short seller Gotham City Research published a report alleging Carvana overstated its 2023–2024 earnings by more than a billion dollars through undisclosed related-party transactions, and the stock dropped 14% in a single session.

This is the story of how Carvana got built, how it nearly died, and what its resurrection really means—especially for anyone trying to separate a real turnaround from a great-looking narrative.

II. Origins: DriveTime & The Garcia Dynasty

To understand Carvana, you have to start with Ernest Garcia II—because without him, Carvana doesn’t exist. And yet, if you skim Carvana’s official leadership charts, you won’t find him anywhere.

In 1990, Garcia II was a 33-year-old real estate developer in Tucson, Arizona, when he pleaded guilty to a felony bank fraud charge tied to the collapse of Lincoln Savings and Loan Association—the Charles Keating scandal that became one of the defining financial blowups of the late 1980s. Prosecutors said Garcia fraudulently obtained a $30 million line of credit through transactions that helped Lincoln conceal its ownership of risky Arizona desert land from regulators. He was sentenced to three years of probation, agreed to cooperate with federal prosecutors in the wider Keating investigation, and—financially—was wiped out. He filed for bankruptcy.

Most people don’t come back from a federal bank-fraud conviction to build a multi-billion-dollar empire. Garcia II did.

A year later, in 1991, he bought Ugly Duckling—a bankrupt rent-a-car franchise—for less than a million dollars. Then he paired it with a small finance operation he’d been putting together and leaned into a business that looked simple on the surface but demanded discipline and stamina: sell used cars to people with poor credit, and finance the purchases yourself.

At the time, subprime auto lending was the industry’s unglamorous corner. It was fragmented, largely ignored by big dealers, and not well understood by institutional investors. Mainstream dealerships preferred selling to borrowers with strong credit, clean paperwork, and low headaches. Garcia saw something else: huge demand, little competition, and a playbook that could scale.

The loop worked like this. Buy cheap cars at auction. Mark them up. Finance them at high interest rates to buyers with limited options. Collect aggressively. When borrowers defaulted, repossess, resell, and start again. Ugly Duckling went public on NASDAQ in 1996 under the ticker “UGLY,” a symbol as memorable as it was on-the-nose. The company grew fast, but controversy followed. In 1999 alone, it faced multiple lawsuits alleging Garcia used his position to personally profit from real estate deals tied to company properties. In 2002, Garcia and co-founder Gregory Sullivan took the company private and rebranded it as DriveTime Automotive Group.

DriveTime became the foundation of the Garcia dynasty. Based in Tempe, Arizona, it grew into the largest privately held used-car sales and finance company in the U.S., with more than 125 dealerships and over 4,000 employees. And crucially, it wasn’t just a retailer. It was a finance machine.

The business had two engines: sell cars and originate loans. Then it would bundle those loans into securitizations—turning monthly payments into bonds and selling them to institutional investors. That recycling of capital was the whole game: originate a loan, sell it, use the cash to originate the next one. DriveTime’s servicing arm, Bridgecrest, handled collections and administration, keeping the value chain in-house from sale to payment to repossession.

But Garcia II’s felony conviction never stopped mattering. It imposed lasting constraints. He was legally restricted from holding formal roles at companies listed on the New York Stock Exchange. He couldn’t sit on Carvana’s board or serve as an officer. He couldn’t hold a banking or lending license in his own name. What he could do was remain the largest single shareholder in the family’s businesses—and shape the next act through ownership, influence, and a successor.

That successor was his son, Ernest Garcia III.

Garcia III grew up inside the used-car world. He later went to Stanford to study economics, and it was there—surrounded by Silicon Valley’s conviction that anything clunky and offline could be rebuilt into software—that the Carvana idea started to harden into a plan. The insight wasn’t exotic. It was personal and universal: buying a used car in America is miserable. You haggle with commissioned salespeople. You wait while someone “talks to the manager.” You’re shuffled into a finance office, pressured through add-ons, and sent home with the uneasy feeling you got played.

Garcia III believed the whole thing could move online. Browse from your couch. See what you’re paying. Get financing. Sign. Schedule delivery. The same way people had learned to buy everything else—from books to shoes—without stepping into a store.

In 2012, he launched Carvana with co-founders Ryan Keeton and Ben Huston, as a subsidiary of DriveTime. The first money came from DriveTime too—very much a family-backed start. The name was “car” plus “nirvana,” a promise that would take years to live up to, but perfectly captured the ambition: frictionless car buying.

DriveTime gave Carvana advantages most startups could only dream about. It meant access to vehicle supply, reconditioning capacity, and two decades of operational know-how about buying, fixing, pricing, and financing used cars. Carvana wasn’t starting from zero; it was starting from inside a working machine.

That connection would eventually become one of the most controversial parts of the Carvana story. Related-party transactions—cars moving between entities, loans being originated and serviced across companies controlled by the same family, facilities and services intertwined—would later draw scrutiny from short sellers, regulators, and governance watchdogs. But in 2012, that fight wasn’t on the horizon.

The immediate problem was more basic, and more existential: could you really get someone to buy a used car online—sight unseen, without a test drive—and feel good about it?

III. Building the Machine: Early Days to IPO (2012–2017)

Carvana launched its first market in Atlanta in 2013. It wasn’t random. Atlanta was big enough to matter, centrally located enough to stress-test delivery logistics, and far enough from Arizona to prove this wasn’t just a DriveTime-adjacent experiment in the Garcias’ backyard.

Then came the hard part: getting real people to do the thing.

“It took us almost a year to sell our first 100 cars,” Garcia III later said. That’s a brutal pace for a startup with big ambitions, and it reflected just how unnatural the idea felt at the time. Buying a car sight unseen from a website required a leap most Americans weren’t ready to take. Carvana tried to lower the bar with a seven-day return policy—basically, test drive it after you’ve already bought it—but early conversion was still tough. Skepticism was high, and finding customers wasn’t cheap.

So Carvana did something that, in hindsight, looks obvious: it built a spectacle.

In 2013, it unveiled its first car vending machine in Atlanta—a multi-story glass tower that “dispensed” vehicles like they were oversized toys. Buy online, show up, insert an oversized coin Carvana hands you, and watch a machine retrieve your car and bring it down to street level.

On one level, it was an engineering gimmick. On another, it was marketing dynamite.

Local news couldn’t resist it. Social media ate it up. The visual did what millions in ad spend often can’t: it made people stop and pay attention. And in 2015, Carvana doubled down with a fully automated, coin-operated vending machine in Nashville—sleeker, bigger, and famous enough to become a tourist stop.

The towers also had a practical angle. They acted like compact pickup and storage hubs, stacking inventory vertically in cities where land is expensive. But their real power was emotional. They made Carvana feel different—fun, modern, and slightly magical—in an industry that most people associated with fluorescent lights and a sinking feeling in their stomach.

While the public saw the glass tower, the company was quietly building the less glamorous machine behind it.

The operational backbone was reconditioning: inspecting, repairing, detailing, and photographing every vehicle to a consistent standard so customers could trust what they were seeing online. Carvana built a 150-point inspection process and software to track each car from acquisition through recon to listing. Then came the logistics problem: delivering cars directly to customers meant investing in a fleet, training drivers, and building a network of hubs positioned to keep delivery times reasonable.

By 2016, Carvana was selling around 18,000 cars a year. In a U.S. used car market that moves tens of millions of vehicles annually, that was still tiny. But it was big enough to prove something important: customers would actually buy a used car online—and not hate the experience.

In April 2017, Carvana went public on the New York Stock Exchange as CVNA. The IPO priced at $15 per share, valuing the company at about $2 billion. It was an unusual pitch for public markets: a money-losing company in a notoriously competitive category, going up against giants like CarMax and AutoNation, plus thousands of entrenched local dealers.

But the story was clean and compelling. Take a massive, fragmented market. Pair it with terrible customer satisfaction. Wrap it in software, logistics, and a brand people remember. Then scale.

Carvana also started making targeted acquisitions to strengthen the engine. It bought Carlypso, a data analytics firm, to sharpen pricing and inventory decisions. And in 2018, it acquired Car360, a Mark Cuban-backed startup focused on 3D photography and augmented reality, for $22 million—another move aimed at the same core problem: if customers can’t physically inspect the car, the online experience has to feel rich enough that they’ll trust it anyway.

Between the IPO and the pandemic, Carvana expanded steadily—but expensively. It added markets, built out hubs, and extended the logistics network required to deliver cars at scale. Revenue climbed fast, but so did cash burn, funded through equity raises, debt, and the securitization of auto loans Carvana originated.

The question hanging over everything was simple, and it would only get louder: could this heavy, infrastructure-first model ever generate durable profits—or was it a beautiful story that only worked as long as capital stayed cheap?

IV. The COVID Boom: Rocket Ship Years (2018–2021)

When the pandemic hit in March 2020, Carvana took the same punch everyone else did. Confidence cratered. The economy slammed on the brakes. Buying a car—especially a used one—felt like the kind of thing you postponed until life returned to normal.

Then, within weeks, “normal” changed. And suddenly Carvana’s entire pitch looked less like a risky experiment and more like the obvious answer.

People didn’t want to wander a crowded lot. They didn’t want to sit shoulder-to-shoulder with a salesperson or get walked into a tiny finance office to sign paperwork. They wanted contactless. They wanted simple. They wanted delivery. In other words, they wanted the thing Carvana had spent seven years building. The company rolled out “touchless delivery and pickup” almost overnight—part genuine operational shift, part perfectly timed messaging—because the core product was already built for a world avoiding in-person retail.

The results were immediate. In the second quarter of 2020, while traditional dealerships were shutting down or limping along, Carvana reported a 25% increase in sales and $1.12 billion in revenue. Over the full year, it sold 244,111 vehicles and generated $5.587 billion in revenue—an enormous jump from the year before. The stock, which dipped below $30 in the March panic, didn’t just recover. It took off.

And the pandemic didn’t just push shoppers online. It rewired the entire used-car market.

Stimulus checks put extra cash in consumers’ pockets. Interest rates fell to rock-bottom, making monthly payments easier to swallow. Then the semiconductor shortage hit, new-car production stalled, and the country ran into a weird, once-in-a-generation problem: there weren’t enough new cars. Buyers spilled into used cars, and used-car prices surged to levels that would’ve sounded fake in 2019—sometimes even exceeding original sticker prices for late-model vehicles.

For a used-car dealer, it was the dream scenario: not “buy low, sell high,” but “buy high, sell higher.” At least, as long as the music kept playing.

Carvana went all in. It expanded aggressively and stocked up on inventory at elevated prices, betting the market would stay hot. Revenue soared. In August 2021, the stock peaked at $376.83, valuing the company at more than $50 billion. Around the same time, Carvana hit a headline milestone: one million vehicles sold—faster than any automotive retailer had ever done it, reaching the mark in just nine years.

Ernie Garcia III got treated like the guy who’d finally digitized the last great offline purchase. The story wrote itself: Carvana was the Amazon of cars. Analysts raced each other to raise price targets. Retail investors piled in. The stock became a momentum rocket, lifted by the same speculative air that was inflating meme stocks, SPACs, and crypto across the market.

But beneath the celebration, something else was piling up: leverage.

To fund inventory and the infrastructure-heavy model—reconditioning capacity, hubs, logistics—Carvana issued debt at a relentless pace. By the time the environment changed, the company would be sitting on roughly $9 billion of obligations. And the inventory play—paying peak-ish prices assuming resale prices would stay peak-ish or go higher—wasn’t some new, software-driven genius. It was a classic cyclical bet, dressed up as inevitability.

When the cycle turned, that bet wouldn’t just hurt. It would nearly kill the company.

V. The ADESA Acquisition: Doubling Down at the Peak (2022)

In February 2022, with Carvana’s stock already well off its August highs but still above $100, the company announced the deal that would come to define the entire downturn: it would buy ADESA’s U.S. physical auction business for $2.2 billion in cash. ADESA, owned by KAR Global, ran 56 auction sites, employed about 4,500 people, and moved more than a million vehicles a year through its lanes. On a slide deck, it looked like a power move. In real life, it was a bet placed at exactly the wrong moment.

The logic, in isolation, was hard to argue with. Carvana’s biggest constraint wasn’t demand. It was throughput—how many cars it could inspect, fix, photograph, and push back out the door. Before ADESA, Carvana’s reconditioning capacity was roughly one million units a year. With ADESA, Carvana said it could add another two million, tripling theoretical capacity to around three million. That’s the kind of number that makes investors start doing “what if they get just a few percent of the whole U.S. market?” math.

ADESA also solved a geographic problem. Used cars are heavy, awkward, and expensive to move. A national network of sites meant cars didn’t have to crisscross the country as often. With ADESA folded in, Carvana said 78% of Americans would live within 100 miles of a facility—closer hubs, faster delivery, and lower transport cost per vehicle.

And then there was the second, quieter benefit: wholesale optionality. Not every car Carvana touches belongs on its retail site. Some are too old, too rough, or too costly to recondition. Historically, Carvana sent those cars to third-party auctions and paid fees to do it. Owning ADESA meant Carvana could run that channel itself—keep the auction economics in-house, add a second revenue stream, and, importantly, have a pressure-release valve when retail demand cooled. Wholesale tends to keep moving even when consumers pull back, because dealers still need to trade inventory.

None of that was free.

To fund the deal, Carvana borrowed $3.275 billion from JPMorgan and Citi, and it set aside another $1 billion for facility improvements. The tab pushed Carvana’s debt load to roughly $9 billion—an eye-popping figure for a company that still hadn’t produced an annual profit. ADESA had done roughly $800 million of revenue and more than $100 million of EBITDA in 2021, but those results were minted in the same overheated market Carvana was now levering itself to the hilt to chase.

The deal closed in spring 2022. Almost immediately, the world flipped. The Fed launched its most aggressive rate-hiking cycle in decades. Higher rates made auto loans more expensive, which dented demand. Supply chains normalized, new-car inventory started coming back, and used-car prices stopped behaving like they were on a one-way escalator. And as capital got more expensive, the entire market repriced risk, punishing debt-heavy growth stories.

Carvana had bought the infrastructure for the next phase of its empire. The problem was that the next phase never arrived. ADESA didn’t land as a turbocharger. It landed as a weight—right as every tailwind that had lifted Carvana turned into a headwind.

VI. The Collapse: 99% Drawdown & Near-Death Experience (2022–2023)

The fall was brutal—and fast. From its August 2021 peak of $376.83, Carvana’s stock slid to under $5 by December 2022, a drop of more than 97%. At the bottom, $3.83 a share, the entire company was valued at less than what it had just paid for ADESA. Wall Street wasn’t pricing in a tough stretch. It was pricing in a funeral.

Under the hood, the numbers justified the panic. Carvana posted a $1.59 billion loss in 2022—more than it had lost in all previous years combined. Cash shrank to $434 million, while total debt sat around $7 billion. Interest expense became its own kind of gravity. At the same time, demand softened as inflation and rising rates hit consumers, and the inventory Carvana had bought at peak prices started sliding in value. What had looked like bold stocking-up in 2021 now turned into writedowns and margin pain.

Then the operational cracks started showing in public. Carvana’s dealer licenses were suspended in Illinois, Michigan, and North Carolina over title-processing delays and administrative issues—exactly the kind of unglamorous back-office failure that can poison trust. For a company selling “car buying, but better,” paperwork breakdowns weren’t a nuisance. They were existential.

And once the stock breaks, everyone rushes to the exits—or to the pile-on. Carvana’s top ten lenders, holding roughly $4 billion of unsecured debt, formed a coordination group. In distressed-land, that’s the siren: get organized because this is headed toward restructuring, maybe bankruptcy. Short sellers pressed. Analysts gave up. Wedbush slapped on a one-dollar price target and said bankruptcy was “becoming more likely by the day.” The story flipped completely. Carvana wasn’t the Amazon of cars anymore. It was the next cautionary tale.

Garcia III later summed up the vibe: “People will line up to kick you when you’re down.” But inside the company, the posture wasn’t resignation. It was triage. Carvana cut more than 4,000 jobs, stripped out over $1.1 billion in annualized expenses, and narrowed the mission to Garcia’s three-step plan: get to operational break-even, fix unit economics, then grow again—if they survived long enough to try.

Because that was the real clock. With $434 million left and debt service eating up cash, Carvana’s runway didn’t feel like years. It felt like months. And without a deal, every week brought the same question closer: would this end in a restructuring that kept the company alive—or a Chapter 11 that wiped out shareholders entirely?

VII. The Restructuring & Resurrection (2023–2024)

In July 2023, Carvana announced the debt exchange that would decide whether it lived or died. It was one of the most closely watched restructurings in recent memory, covering more than 96% of Carvana’s roughly $5.7 billion in unsecured notes across five tranches. Creditors agreed to swap about $5.5 billion of those unsecured bonds for roughly $4.2 billion of new senior secured notes, pushing maturities out from 2025–2030 to 2028–2031. On the headline slide, it looked like a miracle: about $1.3 billion of debt reduction, and more than $455 million of cash interest savings over the first two years.

But the real story was in the fine print.

For the first two years, Carvana could choose to pay interest not in cash, but by issuing more notes—payment-in-kind, or PIK. So the “interest savings” were, in part, a cash-management trick: less cash out the door now, more debt on the balance sheet later. Once that two-year window closed, the deal stepped up to cash interest again, at a 9% coupon. And if Carvana used the PIK option heavily, the face value of the new debt could swell from $4.2 billion to roughly $5.6 billion by 2025—giving back a big chunk of the initial debt reduction.

There was another shift too, and it mattered. The old bonds were unsecured. The new ones were secured by Carvana’s assets. In other words, creditors moved up the food chain. Shareholders moved down.

Still, the exchange bought Carvana the one thing it didn’t have in late 2022: time. With lower cash interest for two years, the company finally had enough breathing room to try to fix the business instead of just surviving the next payment.

And surprisingly quickly, the turnaround started showing up. The layoffs, facility consolidations, and process changes landed faster than many skeptics expected. Carvana also leaned on proprietary software called CARLI, which it used to automate pieces of inspection, pricing, and logistics decision-making. The message was simple: fewer hands, fewer steps, faster throughput—and better margins.

Public markets noticed. From under $5 at the end of 2022, the stock climbed past $55 by the beginning of 2024, a move that made it one of the most violent “dead company” reversals of the era. The Garcia family bought in too. Ernest Garcia II and Ernest Garcia III purchased about $126 million of Carvana shares at depressed prices before the company reported a better-than-expected second quarter in 2023. The timing drew plenty of commentary, but the trades were ultimately treated as compliant with insider-trading rules, coming during an open trading window.

Then came the proof point.

Full-year 2024 results, announced in February 2025, showed a company that looked nothing like the one on the brink a year and a half earlier. Carvana sold 416,348 retail units, up 33% year over year, and generated record revenue of $13.67 billion. It also reported its first full year of GAAP net income: $404 million, about a 3% margin. Adjusted EBITDA reached $1.378 billion, a 10.1% margin. Garcia III declared Carvana “the most profitable public automotive retailer in U.S. history as measured by Adjusted EBITDA margin.” That framing was arguable—adjusted EBITDA strips out costs like stock-based compensation and depreciation—but the direction was hard to miss.

And the momentum carried into 2025. Through the first three quarters, Carvana kept setting records. In Q3, revenue hit $5.647 billion on 155,941 units sold, and net income for the quarter was $263 million. Management guided to full-year 2025 adjusted EBITDA at the high end of a $2.0 to $2.2 billion range. The stock ran above $480—until Gotham City Research’s short report in late January 2026 knocked it back down toward $400, reviving the question Carvana can’t seem to escape: is this a durable resurrection, or just another version of the story that looked unbeatable right up until it didn’t?

VIII. The Business Model: How Carvana Actually Works

Strip away the vending machines and the brand sheen, and Carvana is an integrated used-car retailer with a built-in finance engine. The whole turnaround debate comes down to whether this machine can keep producing real cash flow through a full cycle—or whether today’s valuation assumes everything goes right, forever.

It starts with the customer experience, which is intentionally designed to feel nothing like a dealership. Shoppers browse inventory on Carvana’s website, filter by make, model, year, mileage, price, and features, and click into listings packed with photos—many enhanced by the 3D imaging tech Carvana picked up through Car360—plus a vehicle history report and a single, posted price. No haggling. Pricing is set by Carvana’s algorithms, which blend market comps, demand signals, and the company’s own costs to get the car ready for sale. Buyers can get pre-qualified for financing through Carvana, upload trade-in details, and complete the purchase end-to-end online, often without ever needing to talk to a person.

Behind that clean front end is the hard part: sourcing cars. Carvana brings vehicles in through three main channels—trade-ins tied to purchases, customers selling directly to Carvana without buying, and wholesale auctions. ADESA adds a crucial extra layer: Carvana now owns an auction network, which gives it another source of retail-quality vehicles and a built-in outlet for the ones that don’t belong on Carvana’s retail site.

Once Carvana owns the car, it goes through the reconditioning pipeline—the part of the business customers never see, but the economics live or die on. Vehicles run through a 150-point inspection covering mechanical condition, cosmetic issues, and safety items. Repairs get done, the car is detailed, and it’s photographed for the listing. Historically, this work happened at Carvana’s inspection and reconditioning centers, but ADESA is reshaping the footprint. By the end of Q3 2025, Carvana had added IRC capabilities to 15 ADESA locations, with plans to keep expanding at a similar pace in 2026. The long-term goal is a network of “megasites” that combine wholesale auction operations, retail reconditioning, and logistics in one place—an approach Carvana first put into practice at ADESA’s Kansas City facility in Belton, Missouri.

Then comes the other half of the infrastructure bet: moving the cars. Logistics is both one of Carvana’s biggest potential advantages and one of its biggest cost lines. The company runs its own fleet of multi-car haulers to move vehicles from reconditioning sites to customers’ driveways. ADESA has helped here too: Carvana has said the network reduced inbound transport distances by about 20% and outbound miles by about 10% year over year. In a business where transportation cost hits every unit, those kinds of improvements can meaningfully shift margins.

Carvana makes money in more ways than “buy car, sell car.” Retail vehicle sales are around 70% of revenue, but they aren’t the whole profit story. For many purchases, Carvana originates the auto loan, bundles those loans into asset-backed securities, and sells them to institutional investors—straight out of the DriveTime playbook. The economics come from the spread between what borrowers pay and what investors accept in the securitized product. On top of that, Carvana sells high-margin finance-and-insurance add-ons like vehicle service contracts, GAP coverage, and other ancillary products, which have become increasingly important to overall profitability.

ADESA also gives Carvana a wholesale lever. Vehicles that don’t meet retail standards can be sold through Carvana’s own auction channel, ADESA Clear, which was live at 47 sites by late 2025. That lets Carvana keep more of the economics that would otherwise go to third-party auction houses—and it provides a pressure-release valve for inventory that might not sell well on the retail platform.

If you’re trying to evaluate whether Carvana’s model really works, two measures tend to matter most. First is GPU, or gross profit per unit: how much total gross profit Carvana generates per vehicle when you include retail margin, finance and insurance income, and wholesale results. Second is retail unit growth, because Carvana’s model carries massive fixed costs—sites, trucks, systems—and that creates operating leverage. When units rise and GPU holds, the machine can throw off a lot of profit. When either slips, the same infrastructure that’s supposed to be a moat can start looking like an anchor.

IX. Playbook: Key Business & Strategic Lessons

Carvana’s story reads like a case study in what happens when you combine big ambition with a cyclical market and an appetite for control. The lessons aren’t just about used cars. They’re about strategy, capital, incentives, and what “moats” really look like when the cycle turns.

First: vertical integration cuts both ways. Carvana didn’t just build a website. It built an end-to-end machine—sourcing, reconditioning, pricing, financing, delivery, and, after ADESA, wholesale auctions too. In good times, that structure lets you capture margin at every step and control the customer experience from first click to driveway drop-off. In bad times, it turns into fixed-cost gravity. When demand falls, you can’t simply “order less” from suppliers; you still have to carry the overhead of hubs, trucks, staffing, and facilities built for much higher volume. ADESA intensified that dynamic. Those sites were bought to support a company moving vastly more cars. When volumes fell, they didn’t feel like a growth engine. They felt like a bill.

Second: debt-funded growth is especially dangerous in a cyclical business. Used-car demand and pricing swing with interest rates, consumer confidence, and new-car supply. Levering up to around $9 billion of obligations near the top of that cycle is like building your plans around the best weather you’ve seen in years. It holds—until it doesn’t. Carvana’s crisis wasn’t simply “the business model failed.” It was that the capital structure left no room for normal conditions to return.

Third: related-party relationships can become a permanent valuation discount. The Garcia family’s influence spans Carvana and DriveTime, and that creates inherent conflicts—whether or not anything improper is happening. Carvana has bought cars from DriveTime, loans have been serviced by Bridgecrest (a DriveTime subsidiary), and there have been other shared services and operational ties. These arrangements are disclosed, and Carvana has long said they’re done at arm’s length. Still, in January 2026, Gotham City Research alleged the ties ran deeper than disclosed, including a claim that Bridgecrest charged artificially low servicing fees to third-party loan buyers in exchange for Carvana booking inflated gains on loan sales. Carvana said the report was “inaccurate and intentionally misleading.” Regardless of who you believe, the takeaway is simple: when a public company is intertwined with a family-controlled private empire, governance becomes a risk investors never stop pricing in.

Fourth: marketing can be a product. Carvana’s vending machines were expensive, and they weren’t strictly necessary—traditional pickup centers could have handled the same handoff. But as customer acquisition and brand-building, the towers were brilliant. They generated huge earned media, made Carvana instantly recognizable, and turned a boring transaction into a story people wanted to tell. They were, essentially, giant billboards you could take home.

Fifth: there’s a difference between riding a wave and building a system. The COVID boom was a wave—powerful, lucrative, and temporary. Companies that mistook it for a permanent shift made permanent decisions off temporary conditions. Carvana did that too, especially with inventory and expansion. To its credit, the turnaround playbook wasn’t “get the wave back.” It was: fix unit economics, drive efficiency, and make the machine work even when the environment is normal. Whether that durability holds through the next downturn is still the core debate.

Finally: control cuts both ways, too. Carvana’s dual-class structure and concentrated Garcia ownership mean the company’s direction isn’t decided by minority shareholders. Ernest Garcia II remained the largest individual shareholder even while unable to hold a formal leadership role. That concentration of power made it possible to move aggressively—building what Carvana became, and taking the risks that nearly broke it. It also means that, for better or worse, the Garcias’ vision keeps winning the vote.

X. Bear vs. Bull Case & Competitive Analysis

The Bear Case

The bear case on Carvana is basically a three-part argument: the stock is priced for perfection, the balance sheet still has teeth, and the company operates in an industry that fights you on margins no matter how pretty your app is.

Start with valuation. At prices above $400, Carvana is valued like a high-growth software company—trading at roughly 100 times trailing earnings and at revenue multiples far above traditional peers. CarMax, the largest public used-car retailer, sells more cars, produces steadier profits, and carries a far stronger balance sheet, yet trades at a fraction of Carvana’s multiple. AutoNation trades at an even steeper discount. Bulls call that “disruption.” Bears call it “denial” about what the underlying business actually is: retail—cyclical, capital-intensive, and brutally competitive.

Then there’s the debt. The 2023 exchange bought time, but it didn’t make leverage disappear. Long-term debt was roughly $4.8 billion as of September 2025. And the easy-mode period is over: the PIK window has ended, so cash interest has stepped up. That matters because Carvana is still investing—building out ADESA sites, expanding reconditioning capacity, and pushing growth. If used-car prices soften, or volume growth stalls, the company has less room to absorb a shock before the capital structure starts driving the story again.

Bears also point to customer experience—the very thing Carvana sells as its moat. As the company cut costs, consumer complaints and negative reviews have highlighted problems like title delays, condition issues that don’t match expectations, and slow customer support. For a business that asks customers to buy sight unseen, trust is the product. If that trust erodes, the brand stops being an advantage and becomes a liability.

Step back further, and the structure of the industry is the bear’s favorite exhibit. Used-car retail is not an easy place to build durable pricing power. Entry barriers are low: get licensed, get inventory, start selling. Buyer power is high because consumers can comparison-shop instantly. Supplier dynamics are messy because sourcing is competitive and fragmented. Substitutes exist too—ride-sharing, improving public transit in some metros, and newer ownership models that can reduce the need to buy a car at all, especially for younger buyers. And rivalry is intense: CarMax, AutoNation, thousands of independent dealers, and increasingly capable online experiences from incumbents all compete for the same transactions.

Look at it through Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers lens, and skeptics argue Carvana’s defensibility is thinner than the stock implies. True scale economies are limited because used-car logistics and demand are local. Network effects are weak: Carvana doesn’t get meaningfully more valuable just because more people use it, the way a marketplace or social network does. The brand is real, but not the kind that creates durable pricing power. The strongest “power” is process—its reconditioning and logistics system—but that’s something competitors can replicate if they have enough capital, time, and operational discipline.

The Bull Case

The bull case flips the same facts into a different conclusion: Carvana has built the best machine in a huge market, and if it keeps running, the operating leverage can be extraordinary.

Carvana is the dominant digital brand in the U.S. used-car market, which is massive. And despite selling more than 400,000 vehicles in 2024, it’s still only a small slice of total transactions—meaning the growth runway is long if the model holds up. The company’s platform, logistics network, and brand recognition give it an early lead that others have struggled to match. The two most visible digital challengers didn’t make it: Vroom effectively exited the retail model, and Shift shut down. Meanwhile, CarMax has improved online, but bulls argue it still lacks Carvana’s end-to-end digital flow and the brand association with “buying a car online” that Carvana has essentially claimed.

ADESA—the deal that looked catastrophic in 2022—could be the asset that makes Carvana’s system hard to copy. The megasite model, where wholesale auctions, retail reconditioning, and logistics live together, is designed to drive down time, miles, and cost per unit. Carvana has said the real estate footprint can support retail production capacity of about three million units annually and that it expected fully built-out capacity of over 1.5 million units by the end of 2025. If demand grows into that capacity, the math gets compelling: you push more units through a largely fixed infrastructure base, and margins expand.

Bulls also bet that consumer behavior keeps moving in Carvana’s direction. The pandemic didn’t invent online shopping, it accelerated it. And cars are one of the last giant purchases to truly move over. Younger buyers, especially, are comfortable buying big-ticket items digitally, and they have little patience for the dealership ritual. If “digital-first” becomes the default, Carvana is positioned to take share.

Finally, there’s management. Even critics concede this: most companies that get trapped like Carvana did in 2022—overleveraged, bleeding cash, with creditors coordinating—do not survive. Carvana did. Garcia III and his team not only avoided bankruptcy, they executed a turnaround that, so far, has been faster and more profitable than almost anyone expected. For bulls, that track record earns the benefit of the doubt on the next phase.

The Competitive Landscape

CarMax is still the heavyweight: hundreds of locations, a strong balance sheet, and decades of operational excellence. AutoNation brings scale too, with diversification across new and used vehicles. And traditional franchised dealers are pushing hard into digital, chipping away at Carvana’s early advantage.

But Carvana’s argument is that none of those competitors have the same combination in one company: a digital-native shopping flow, a vertically integrated logistics network, and a large, owned wholesale auction footprint through ADESA. Whether that combination becomes a true moat—or just an expensive structure that’s hard to keep full—remains the central bet.

XI. Analysis & Future Speculation

The central question for Carvana investors is deceptively simple: is the turnaround real?

On the surface, the scoreboard says yes. Through 2024 and into 2025, revenue rose, unit sales climbed, and profitability showed up where it hadn’t before. But Gotham City Research’s January 2026 report forces a more uncomfortable follow-up: even if the company is improving, how much of what you’re seeing is operating progress—and how much is accounting, structure, and timing?

The short seller’s core allegation goes straight at the heart of the comeback story. Gotham argues that Carvana’s profitability was inflated by favorable related-party dynamics with DriveTime and Bridgecrest, both controlled by the Garcia orbit. The claim, in essence, is that gains on loan sales look better than they should because servicing economics are being shifted in ways that don’t reflect market rates. If that’s true, then reported margins overstate the underlying economics of the business. Carvana has denied the allegations. And notably, JPMorgan raised its price target even after the report, signaling that at least some institutional investors see the claims as either overstated or already priced in. Either way, the next real checkpoints are concrete: the February 2026 earnings release and the annual 10-K, where detail tends to replace slogans.

Then there’s governance—an issue Carvana can’t grow out of. Ernest Garcia II’s felony conviction, his controlling stake across both Carvana and DriveTime, and his legal inability to serve as an officer or director of a NYSE-listed company produce a structure that’s hard to map onto a normal public-company template. Carvana has long said the DriveTime relationship is conducted at arm’s length. But when the same family has deep economic interests on both sides of key transactions, the risk isn’t just wrongdoing. It’s perception, incentives, and the permanent question of whose interests come first when trade-offs appear.

And looming over all of it is the debt clock. The restructuring bought time, but time isn’t the same thing as forgiveness. With the PIK interest window no longer available, cash interest becomes real again—money leaving the building, not just numbers rolling forward. That makes the next phase less forgiving: servicing the debt now depends on Carvana sustaining volume and margin improvements in a business tied tightly to rates and consumer budgets. If the economy weakens, or if interest rates stay high longer than expected, leverage stops being background noise and starts being the whole story again.

ADESA sits at the intersection of everything: the biggest opportunity and the sharpest execution risk. Turning 15 integrated IRC locations into a planned network of roughly 60 megasites by 2030 means years of capital spending, operational consistency, and demand that stays strong enough to keep those facilities utilized. Carvana has laid out an ambitious vision—selling three million cars per year at a 13.5% adjusted EBITDA margin—which would make it one of the largest and most profitable retailers in the country. But that outcome lives five to ten years into the future, and it assumes a lot of things break the right way.

In the end, Carvana’s fate may hinge less on whether management is capable—its survival through 2022–2023 proved something there—and more on forces no one at Carvana controls: the path of interest rates, consumer confidence, new-car supply, and regulators’ tolerance for operational missteps.

What is certain is that this story isn’t finished. Carvana survived the near-death experience. But with billions of debt still hanging over it, a governance structure that invites scrutiny, and a valuation that implies years of clean execution, the margin for error is thin.

XII. Recent News

The biggest headline in early 2026 was a short report from Gotham City Research, published January 28, 2026. Titled “Carvana: Bridgecrest and the Undisclosed Transactions and Debts,” it argued that Carvana overstated its 2023–2024 earnings by more than $1 billion through related-party dynamics tied to DriveTime’s loan-servicing arm, Bridgecrest. Gotham’s central claim was that Bridgecrest charged unusually low servicing fees to third-party buyers of Carvana’s securitized auto loans—fees that, in Gotham’s view, made Carvana’s gains on those loan sales look better than they really were. The report also alleged that DriveTime burned more than $1 billion in operating cash flow during 2023–2024 while taking on leverage of 20 to 40 times earnings, far above historical norms. And it made two forward-looking calls designed to rattle investors: that Carvana’s 2025 10-K would be delayed, and that Grant Thornton—the auditor for Carvana, DriveTime, and related entities—would resign.

The market reaction was immediate. On January 28, Carvana shares fell as much as 20% intraday before closing down 14.2% at $410.04. Carvana responded by calling the report “inaccurate and intentionally misleading,” and it reiterated that it still planned to report fourth-quarter and full-year 2025 results on February 18, 2026. That same day, securities law firm Bleichmar Fonti & Auld announced an investigation into potential federal securities-law violations. Meanwhile, JPMorgan went the other direction—raising its price target to $510 from $490 and keeping an Overweight rating, a signal that its analysts didn’t view the short thesis as a knockout blow.

Operationally, the ADESA integration kept moving forward. Carvana completed its tenth IRC integration of 2025 at ADESA Long Island and said it planned to start full build-outs at select locations in 2026. Its digital auction platform, ADESA Clear, was live at 47 sites by late 2025. Management guided for continued integration at a similar pace in 2026, while reiterating its long-term ambition: three million vehicles sold annually at a 13.5% adjusted EBITDA margin.

XIII. Links & Resources

- Carvana Investor Relations: investors.carvana.com

- Carvana on SEC EDGAR (CIK: 0001690820)

- Q3 2025 Shareholder Letter (October 2025)

- Q4 and Full Year 2024 Earnings Release (February 2025)

- Gotham City Research report: “Carvana: Bridgecrest and the Undisclosed Transactions and Debts” (January 2026)

- CNBC coverage of the Gotham City Research short report (January 28, 2026)

- Carvana 2023 Debt Exchange Summary (Carvana Investor Relations)

- Ernest Garcia II biographical profile (Wikipedia)

- ADESA integration press releases (Carvana Investor Relations, 2025)

- CarMax and AutoNation annual reports (for competitive context)

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music