Carter's Inc.: From Gold Rush Baby Clothes to America's Childrenswear Empire

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture this: you’re a new parent in America. You’re running on fumes, you’ve finally made it to the baby aisle, and you’re staring at a wall of tiny onesies that all somehow look the same. In that moment, you don’t want to run a product comparison. You want the safe choice. The trusted choice. The one you’ve heard of a hundred times.

For a huge share of the market—roughly a quarter of sales in both children’s sleepwear and clothing for newborns through age two—that choice is Carter’s. For about 160 years, this brand has been showing up in one of life’s most universal moments: dressing a baby for the first time.

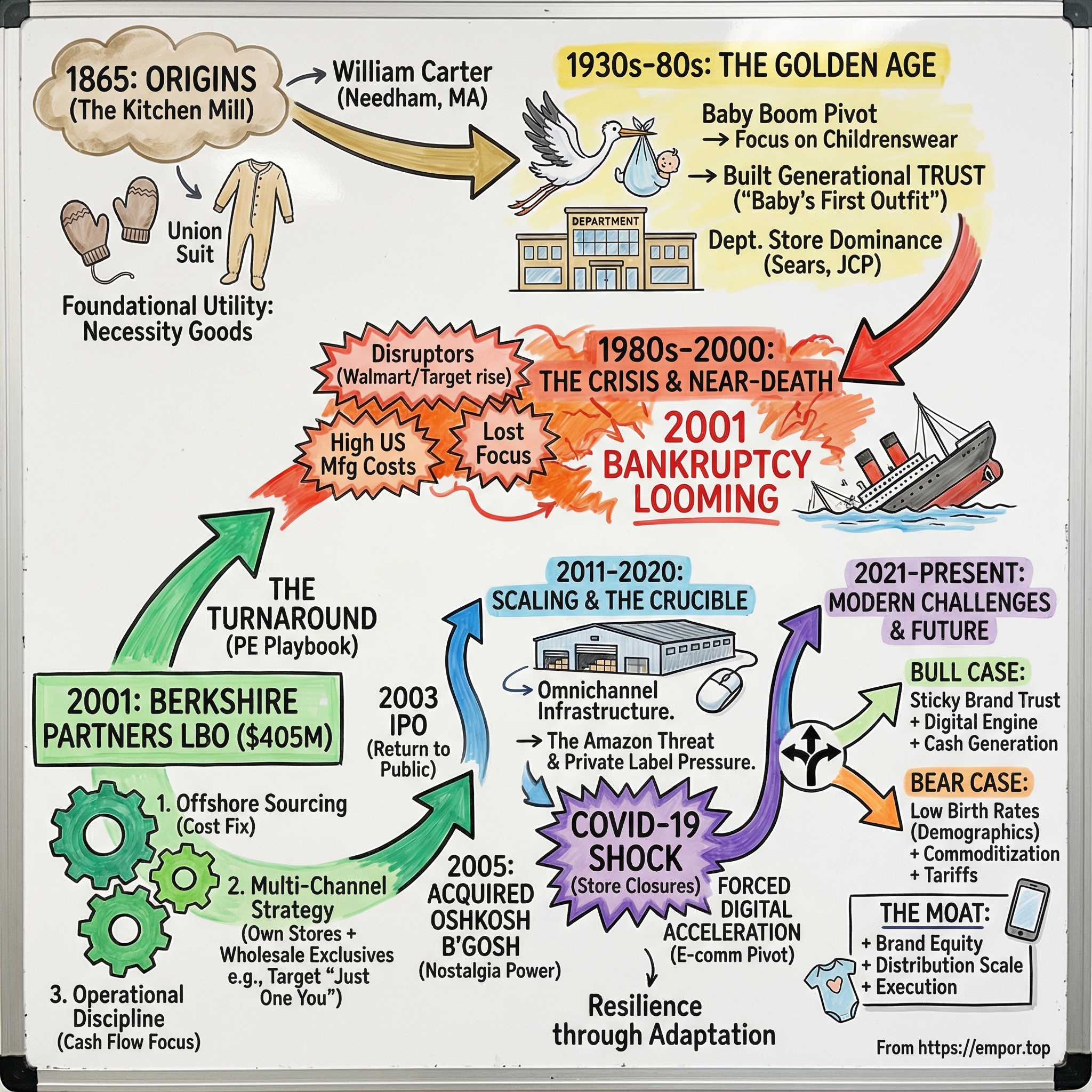

So how did a 19th-century knitting mill in Massachusetts become America’s default name in baby clothes—and nearly die twice along the way? That’s the question at the heart of this story.

Today, Carter’s, Inc. is a major American designer and marketer of children’s apparel. It generates about $2.83 billion in trailing twelve-month revenue, with a market capitalization around $1.32 billion. On paper, it’s almost comically unsexy: basics, onesies, pajamas. And yet it’s also a fascinating paradox—a “boring” business that has stayed resilient even as Amazon rewired retail.

One market research firm found that 90 percent of millennial parents—and 80 percent of baby boomer grandparents—shopped at Carter’s in the past year. That’s not just customer awareness. That’s multi-generational habit. There aren’t many consumer brands that can credibly claim that kind of reach across decades of families.

But Carter’s didn’t get here on a straight line. This is a story of Civil War-era origins, strategic stumbles, near-death experiences, a private-equity-led transformation, and an ongoing fight to stay relevant in a digital-first world. Ownership changed hands through a series of pivotal moments: an IPO in 1984, a Berkshire Partners leveraged buyout in 2001 that took the company private, and a return to the public markets with a second IPO in 2003.

Why does this company matter—beyond the fact that it outfits millions of kids? Because it sits at the intersection of three big forces: necessity goods that people keep buying in almost any economy, the value-creation playbook of private equity operational excellence, and the brutal math of modern retail disruption. Whether you’re looking at Carter’s as an investment or as a case study in how iconic American brands survive, there are real lessons here.

And we’re meeting Carter’s at a particularly interesting moment. Michael D. Casey retired as Chairman and CEO after more than 15 years in the role, and more than 30 years with the company. Carter’s is navigating a leadership transition at the same time tariff headwinds have scrambled its cost structure. To understand how it got here—and where it might go next—we have to go all the way back to the beginning.

II. The Gold Rush Origins & Early Foundation (1865–1920s)

It was 1865. The Civil War had just ended. Lincoln had been assassinated. And the United States was about to rocket into an industrial boom that would reshape everyday life—including what people wore, how it was made, and where it came from.

In a small Massachusetts town called Needham, a new company was born: the William Carter Company. But the man behind it wasn’t a native son.

William Carter (1830–1918) was born in Alfreton, Derbyshire, England—right in the heart of the textile world. When he arrived in America on January 28, 1857, he didn’t show up with a fortune. He showed up with a skill: deep know-how in knitting and textiles, the kind of practical expertise that powered a huge share of 19th-century American enterprise.

Eight years later, with the war over and opportunity everywhere, Carter made his bet. He started by knitting mittens in his kitchen. Not a factory. Not a mill. A kitchen—one man, a machine, and the earliest version of what would become an American household name.

And here’s the key: he didn’t choose baby clothes by accident. He had found something timeless. Babies outgrow clothing constantly, no matter what the economy is doing. Parents don’t “trade down” on the basics if they can help it, especially when it comes to safety and comfort. Long before anyone had language like “recession-resistant” or “non-discretionary demand,” Carter had stumbled into a category where the need never goes away.

Early on, ownership was as simple as it gets. The William Carter Company was founded and controlled entirely by William Carter himself—a sole proprietorship built from the ground up, with no early outside backers.

As New England’s textile economy surged, the company grew with it. Carter expanded beyond mittens into children’s undergarments, including one product that would become a staple in American households: the “union suit,” a one-piece undergarment. It sounds quaint now, but in an era before central heating, these weren’t cute extras. They were real necessities.

The business stayed in the family, and the handoff to the next generation—often the moment when family companies wobble—turned into an upgrade. Carter had four children, including William Henry Carter (1864–1955). William Henry served two terms in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1915 to 1919, and then became president of the William Carter Company in 1918. Having a former Congressman at the helm didn’t just add prestige—it signaled stability, credibility, and seriousness to the outside world.

And while the brand began in Massachusetts, the company’s footprint eventually mirrored the broader migration of American textiles. By the early 1960s, the William Carter Company manufactured at seven mills in Massachusetts and the South, following the industry toward lower costs and a different labor environment.

But the real legacy of this founding era isn’t a particular factory or garment. It’s the positioning Carter’s locked in early: safe, trusted, essential. Not fashion. Not status. The basics parents needed again and again as their kids grew. That simple idea became the foundation for a moat that held for generations—until the retail world itself began to change beneath it.

III. The Golden Age: Building Brand Equity (1930s–1980s)

The Great Depression wiped out plenty of American businesses. Carter’s didn’t just survive it—it deepened the thing that would become its greatest asset: trust. When families cut back everywhere they could, they still had to clothe their kids. And the department stores that made it through the crisis remembered the suppliers who were steady when everything else was shaky. Carter’s became one of them.

World War II brought a different kind of stress test: shortages, disrupted labor, rationing. But when the war ended, America surged into a wave that was almost tailor-made for a childrenswear company. Soldiers came home, marriages spiked, and then came the baby boom. From 1946 to 1964, demand for anything infant-related wasn’t just strong—it was relentless.

Carter’s met that moment with a strategic pivot that, in hindsight, looks obvious and in real time was decisive. In the 1950s, it moved its focus toward children’s wear, away from adult undergarments, and into the category it would come to define. Just as millions of new families were figuring out parenthood in real time, Carter’s positioned itself as the safe, essential choice for infants and toddlers.

The marketing didn’t try to be clever. It tried to be reassuring. “Trusted by generations of mothers” worked because it was more than a line—it matched reality. Brand loyalty wasn’t won one customer at a time; it was handed down. Grandmothers told daughters. Daughters told daughters. And for new parents overwhelmed by a thousand decisions, reaching for the same label their family had always used felt like one decision they didn’t have to overthink.

Distribution amplified that trust into ubiquity. Carter’s was everywhere parents already shopped—Sears, JCPenney, and local department stores across the country. If you were buying kids’ clothes in America, you were almost certainly seeing Carter’s on the rack.

The products evolved in the same practical, parent-first way. Fabrics got stretchier. Closures got easier—snaps replacing the buttons that no one wants to wrestle with in the middle of the night. Materials and construction moved toward safety features that would later become table stakes. None of this was flashy. That was the point. Each small improvement reinforced the idea that Carter’s understood real parents in real moments.

And then there was the emotional pinnacle: “baby’s first outfit.” The set of clothes you bring your newborn home in isn’t just another purchase—it’s a memory. Carter’s became attached to that memory for countless families, and that kind of association is the closest thing retail has to a lock-in.

But the same success that built the brand also set a trap. By the 1980s, the ground under American retail started shifting fast. Discounters like Walmart and Target changed expectations on price and pressured suppliers’ margins. Department stores—Carter’s longtime stronghold—began a slow, painful decline. And Carter’s U.S. manufacturing base, once a source of pride and control, increasingly looked like an anchor as competitors moved production offshore and reset the cost structure of the entire category.

The company that had made it through depression and war now faced a different enemy: a new retail reality. And stability, which had been its strength for decades, started to look a lot like inertia.

IV. The Near-Death Experience: Bankruptcy and Decline (1980s–2000)

By the late 20th century, the Carter’s story stopped being a slow, steady family enterprise and started looking like a cautionary tale.

The Carter family ultimately exited in 1990, ending roughly 125 years of family ownership. That long run had kept the founder’s original idea—quality, practical knitwear for kids—at the center of the company’s identity. But by then, identity wasn’t the problem. The world around Carter’s had changed faster than the company did.

And once the old playbook stopped working, the mistakes didn’t arrive as one big, obvious blunder. They piled up.

First came the cost problem. Carter’s held onto U.S. production longer than many competitors, even as apparel manufacturing sprinted offshore and a new, cheaper global supply chain became the industry default. The result was simple: Carter’s cost structure stayed high while everyone else reset theirs lower.

Then came the channel squeeze. Walmart and Target were rising into the center of American retail, and they didn’t just want to stock your product—they wanted to control it. Exclusive items, lower prices, and tough terms became the price of admission. Meanwhile, Carter’s still depended on department stores, where it had built its brand and its distribution. Trying to serve both worlds created real channel conflict: protect your traditional partners, or chase the volume where the foot traffic had moved.

To make it worse, the department store world itself started thinning out. Montgomery Ward vanished. The survivors consolidated. Macy’s and JCPenney grew through mergers and became bigger, fewer buyers with more leverage. Every consolidation tipped bargaining power away from brands like Carter’s and toward the retailers that controlled shelf space.

Management tried to diversify its way out. On paper, acquisitions and new product lines offered growth and “synergies.” In practice, they soaked up cash and focus. Execution lagged. Some initiatives fizzled. Debt climbed even as the core business weakened.

By the late 1990s, the company was in real trouble. Carter’s was bleeding cash, and the fixes it reached for only created new problems. Cost-cutting started to show up in the one place you couldn’t afford it: the product. Quality slipped, and with it, the trust that had taken generations to earn. Inside the company, morale cratered. Leadership churned. The spiral fed itself.

In 1996, Investcorp acquired Carter’s for $208 million from Wesray Capital Corporation. The thesis was familiar: an iconic brand, temporarily broken, that could be restored through operational improvements. But the turnaround was slower—and harder—than expected.

All of it led to Carter’s low point in 2001: the moment the company came closest to disappearing. Bondholders took control. Survival wasn’t a given. An analyst who visited headquarters around this time described a place that felt like it was running on desperation.

So what almost killed Carter’s? Not one thing—an entire pattern of failing to adapt. Holding onto expensive domestic manufacturing while competitors went offshore. Relying on a department store ecosystem that was shrinking. Underestimating how completely mass merchants had changed the economics of selling basics.

But here’s the twist, and it’s the reason Carter’s story doesn’t end in that bankruptcy-era fog: the brand still mattered. Parents still trusted the name. Retailers still wanted the product. The machine was broken, but the signal—safe, reliable, essential—was still there.

That gap between brand equity and operational execution was everything. The brand hadn’t failed. The business model had. And business models can be rebuilt—if the right owner shows up with the discipline to do it.

V. The Berkshire Partners Transformation (2001–2011)

After four and a half bruising years, Investcorp—the Bahrain-listed investment firm that had bought Carter’s in 1996—found its buyer. Berkshire Partners, a Boston private equity firm, agreed to acquire the William Carter Company for $405 million, nearly double what Investcorp had paid.

Berkshire officially closed the deal on August 15, 2001. Externally, the timing was awful—just weeks before September 11 would rattle the country and the economy. Internally, it was exactly what Carter’s needed: a clean break, a reset button, and an owner willing to do the unglamorous work of rebuilding the business from the inside out.

Berkshire put in about $130 million of equity and financed the rest with debt—classic leveraged buyout structure, and a capital structure that would shape Carter’s for years. The encouraging part was that the company still had real volume. By 2000, consolidated net sales were $471.4 million, up sharply from $318.2 million in 1996. Wholesale sales rose from $189.0 million to $256.1 million, and retail outlet store sales jumped from $129.2 million to $215.3 million. The demand was there. The question was whether Carter’s could finally run the machine properly.

That’s what Berkshire brought to the table: a retail-operations playbook. Not “brand magic.” Execution. Supply chain fixes. Store discipline. Professional management. The stuff that’s easy to say and hard to do.

And Berkshire had the right internal leader ready to step into the moment. Michael Casey had joined Carter’s in 1993 as Vice President of Finance and became Chief Financial Officer in 1998. Under Berkshire’s ownership, Casey emerged as the central operator of the turnaround. He would later become CEO in 2008 and lead the company for more than 15 years.

The turnaround itself came in three interlocking moves.

First came the operational fix. Carter’s finally did what it had resisted for too long: it shifted production offshore to Asia and moved away from the expensive U.S. manufacturing footprint that had been crushing margins. This wasn’t just “move the sewing.” The company rebuilt its supply chain and installed modern inventory management, forecasting, and logistics processes. Carter’s cost structure started to look like the rest of the industry’s—meaning it could compete again.

Second came the channel strategy. Carter’s went aggressively multi-channel. It kept feeding wholesale partners—department stores, specialty retailers, and mass merchants—but it also expanded its own direct-to-consumer store fleet. At the time, that was a risky, even controversial bet. Owning your own stores can spook wholesale partners. But it also gives you something wholesale never can: control over how the brand shows up in the world, and a direct relationship with the customer.

This is also where Carter’s made a smart, quietly powerful move in mass retail. In the early 2000s, it reached an agreement with Target to create “Just One You,” an exclusive line sold only in Target stores. Later, Carter’s created exclusive lines for Walmart and Amazon, too. The products were similar—bodysuits, pajamas, dresses—but each line had its own design team and its own pricing approach tailored to that retailer. The genius here was separation: Carter’s could win in mass without dragging its core brand into a race to the bottom.

Third came brand revitalization. With the operations improving and the channels expanding, Carter’s leaned back into what it had always owned: trust. The positioning sharpened around “trusted quality at accessible prices,” reinforcing that Carter’s wasn’t luxury and wasn’t disposable—it was the safe choice, priced for real families.

The payoff came fast. In 2003, Carter’s was healthy enough to go public. The company priced its initial public offering at $19.00 per share and began trading on October 24 on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker “CRI.” Two years after Berkshire’s acquisition, Carter’s had regained access to the public markets. That is not normal turnaround speed.

But Berkshire wasn’t finished building.

The transformational acquisition arrived in 2005: OshKosh B’Gosh. Carter’s purchased 100 percent of OshKosh’s common stock for approximately $312 million. It was a big swing—and a logical one. OshKosh, founded in Oshkosh, Wisconsin in 1895, was an American icon in its own right, best known for its children’s clothing and especially its bibbed overalls. It carried the same kind of emotional baggage Carter’s did: nostalgia, hand-me-down history, a “my parents bought this for me” glow.

The fit worked because the brands didn’t step on each other. Carter’s dominated baby and infant basics. OshKosh owned playwear for toddlers and young kids. Together, they covered childhood from newborn through elementary school—different jobs, different wardrobes, one combined platform.

Financially, Carter’s said it expected the deal to be neutral to slightly accretive to earnings in 2005 and accretive in 2006, after non-cash purchase accounting adjustments. Operationally, it moved even faster. Carter’s shut down all 15 OshKosh “Lifestyle” stores and 14 underperforming OshKosh outlet stores, closed OshKosh’s Liberty, Kentucky distribution center to consolidate distribution, and completed the shift to third-party sourcing by closing OshKosh’s Choloma, Honduras sewing facility and planning to close the Uman, Mexico facility in the first half of fiscal 2006.

This is the part of the story that’s easy to admire from a distance and brutal up close: the discipline was relentless. Inventory got managed tightly. Working capital became a lever, not a mess. Cash flow became a priority, not an afterthought.

That, more than any single product or campaign, is what Berkshire really changed. Carter’s became a business that could reliably generate cash, fund investments, and still support shareholder returns—all while operating with the leveraged balance sheet the buyout had created.

It’s the private equity operational playbook, executed cleanly: buy a distressed company with real brand equity, fix the engine, make a smart acquisition, professionalize the team, and use the public markets as the exit. In Carter’s case, it wasn’t just value creation. It was a rescue—and a reinvention.

VI. The Public Company Era: Scaling and Optimization (2011–2015)

With the turnaround complete and the company back in the public markets, Carter’s settled into something it hadn’t enjoyed in years: a repeatable growth machine. Management organized the business around a “four-pillar” strategy—Carter’s retail, OshKosh retail, wholesale, and international—and then ran each pillar with clear goals and tight execution.

The most visible move was store growth. Carter’s ramped up openings aggressively, adding roughly 70 to 100 stores a year. A lot of those were outlets, where the brand could turn inventory quickly and reach value-oriented families. Over time, the expansion pushed further into mid-tier shopping centers, too. The pitch was simple: small boxes, lean staffing, and strong store-level economics.

In 2012, Carter’s announced a major bet on infrastructure: a 1-million-square-foot, $50 million distribution center in Braselton, Georgia. It was designed to support e-commerce, retail, and wholesale all at once, and the company said it hoped the facility would create up to 1,000 jobs by 2015.

That kind of investment wasn’t just about moving more boxes. It was a signal that Carter’s understood where retail was headed. Omnichannel isn’t a marketing concept—it’s a logistics problem. Things like buy-online-pickup-in-store and ship-from-store only work if your physical network can flex, fulfill, and recover when demand shifts. Carter’s was building the backbone early, before the world forced everyone’s hand.

The company also started widening the definition of what “Carter’s” could sell. In February 2017, Carter’s, Inc. acquired Skip Hop Inc., a New York-based infant and child product company, for $140 million in cash plus up to $10 million in contingent payments tied to 2017 performance. Skip Hop’s business was adjacent but meaningfully different: diaper bags, kids’ backpacks, travel accessories, home gear, and hardline products for playtime, mealtime, and bathtime—essentials with a stronger tilt toward design and function.

Strategically, it made sense. If you’ve already earned a parent’s trust on the clothing that touches their baby’s skin, it’s not a huge leap to earn the right to sell the diaper bag they carry every day. Skip Hop wasn’t just diversification; it was a way to capture more of the same customer’s basket.

International growth, meanwhile, was real but measured. Canada was the obvious first step—similar consumers, familiar retail dynamics, and simpler logistics. Mexico followed. But the global breakout some investors imagined never fully materialized. Carter’s remained, overwhelmingly, a North American story.

And for a while, the public-company narrative was almost boring in the best way: steady growth, disciplined margins, dependable cash flow, and shareholder returns through dividends and buybacks. Wall Street rewarded the predictability. Carter’s became the kind of company people describe as a “boring compounder”—not flashy, but consistent.

By 2019, beyond selling through third-party retailers, Carter’s operated 1,060 branded stores and outlets, and it was still planning to add as many as another 100 stores in “mid-tier” malls in the years ahead.

But buried inside all that consistency was the risk. The strategy leaned heavily on physical retail. Physical retail leaned heavily on malls. And mall traffic was about to get hit from two directions at once.

VII. The Amazon + COVID Crucible (2016–2020)

The “retail apocalypse” didn’t hit like a single event. It seeped in. Mall traffic softened. Store closures became normal. And then, almost overnight, everyone realized the center of gravity in retail had moved.

No company embodied that shift like Amazon. Shopping habits migrated from aisles to search bars, and few groups adopted the change faster than young parents. They were already buying diapers, wipes, and formula online. Clothing wasn’t a leap—it was the next click.

For Carter’s, this wasn’t just another channel to learn. It was an existential question: could a 150-year-old baby-clothes brand survive a world where convenience, infinite selection, and price transparency were the default? Amazon trained customers to expect two-day delivery on everything, including a pack of onesies.

Then Amazon pushed directly into Carter’s home turf with private-label kids’ apparel—Simple Joys and Amazon Essentials. These weren’t flimsy knockoffs. They were good enough, cheap enough, and perfectly placed at the moment of purchase. For a big chunk of price-sensitive parents, that’s all it takes.

Carter’s response wasn’t a single bold move. It was a series of practical, defensive decisions—exactly the kind that determine whether a legacy retailer adapts or fades.

First, it accelerated e-commerce investment. The company upgraded its digital platforms, pushed harder on mobile, and built better personalization. Online sales stopped being “nice to have” and became a core pillar of how Carter’s planned to reach customers.

Second, it started rationalizing the store fleet. Closures came quietly at first—underperforming mall locations, leases that no longer penciled out. The mindset shifted from “open more doors” to “make the doors we have work better.” Expansion gave way to optimization.

And third, Carter’s did something that sounds counterintuitive until you remember how retail power works: it leaned into Amazon instead of treating it like an enemy. Carter’s created exclusive lines for major partners, including Walmart and Amazon. Simple Joys—made by Carter’s, sold only on Amazon—gave Amazon what it wanted without forcing Carter’s to cheapen its core brand everywhere else. It was a controlled compromise: let the giant have its exclusive, protect the flagship name, keep the volume.

Then came COVID-19, and whatever was gradual instantly became extreme.

The pandemic temporarily shut down Carter’s entire store fleet—more than a thousand locations that generated the bulk of its direct-to-consumer revenue. Inventory sat stranded. Fixed costs didn’t stop. The survival math turned ugly fast.

But at the same time, the world’s shopping behavior snapped into a new shape. U.S. e-commerce sales surged in 2020, jumping by $244.2 billion, or 43%, according to the 2020 ARTS release. Parents stuck at home still needed clothes as kids grew, and for long stretches, online wasn’t a preference—it was the only option. Carter’s earlier digital buildout, done before anyone imagined a global shutdown, suddenly looked like foresight.

Stimulus checks added fuel. Families cut travel and entertainment spending to near zero, and many redirected that money toward home and kids. The pandemic didn’t just boost online shopping; it pulled the timeline forward, accelerating the shift away from physical retail by roughly five years.

Before COVID, Casey said the company had delivered 31 consecutive years of growth. That streak ended in the initial disruption, but what mattered more was what came next: the recovery showed that the core engine—trusted basics, repeat purchase behavior, and a now-real digital business—still worked.

The lesson wasn’t subtle. Digital wasn’t optional. It was existential. Omnichannel capabilities weren’t buzzwords; they were the difference between surviving and being stranded when the world changed. And when parents couldn’t touch products before buying, brand trust became even more valuable.

Years later, leadership would turn over, too. Michael D. Casey retired as Chairman and Chief Executive Officer after more than 15 years in the role and over 30 years with the company. Richard F. Westenberger was appointed interim Chief Executive Officer, in addition to his responsibilities as Senior Executive Vice President, Chief Financial Officer & Chief Operating Officer.

The transition announced in January 2025 closed the book on the era defined by Casey—taking Carter’s from near-bankruptcy to industry leadership, then steering it through the most severe retail shock in modern history. The next chapter would be about building on that foundation in a world where the fight for relevance would be won—or lost—online.

VIII. The Modern Carter's: Digital, DTC, and the Next Chapter (2021–Present)

Post-COVID, Carter’s operated with a fundamentally different operating model than it had just a few years earlier. E-commerce had gone from an afterthought to a major engine of the business—far larger than it was a decade ago—and the company leaned into it with heavier investment in digital marketing, personalization, and mobile shopping.

At the same time, Carter’s kept pulling a big lever it could control: its store base. Store fleet rationalization continued, and the company said it would shutter about 150 underperforming North American stores as leases expired over the next three years—up from its previously disclosed plan to close 100. Those 150 stores represented roughly $110 million in annual net sales, so this wasn’t just “tidying up.” It was a strategic retreat from doors that no longer earned their keep.

That push came with painful internal cuts, too. Carter’s increased its planned closures by 50 and began downsizing its workforce, cutting around 300 office jobs by the end of 2025. The company said it expected those reductions to generate about $35 million in annual savings starting in 2026.

But even if Carter’s got leaner, the hardest strategic problem didn’t go away. The wholesale dilemma remained: Carter’s still needed the reach of Target, Walmart, and Amazon—partners big enough to move enormous volume, and powerful enough to demand exclusives and sharp pricing. Meanwhile, Carter’s also wanted to grow direct-to-consumer, where it controlled the experience and typically earned better margins. Keeping both sides happy required constant negotiation, careful assortment decisions, and disciplined brand management.

On the product side, Carter’s accelerated innovation in areas that matched where modern parents were headed. Sustainability initiatives expanded into organic cotton options and recycled materials. The Little Planet sub-brand targeted eco-conscious millennial parents. And adaptive clothing for children with disabilities wasn’t just a values statement—it also represented a real commercial opportunity.

Because the customer had changed, too. Millennials and Gen Z parents were digitally native, values-driven, and skeptical of traditional advertising. They researched purchases online before buying, and they didn’t just talk to friends and family—they posted. In this world, praise spreads fast, and so does criticism.

Competition only made the pressure sharper. Target’s Cat & Jack, launched in 2016, became one of the most serious threats in the category. The brand reached $2 billion in sales in a little more than a year. Target held 3.2% of the industry, ranking fifth behind Carter’s, Gap, Nike, and The Children’s Place—but Cat & Jack’s trajectory signaled that Target was gaining share.

At the same time, digitally native DTC brands like Primary and Honest Company captured mindshare with millennial parents by leaning into transparency and design. They were still small compared to Carter’s, but they pointed to the shape of the next wave of competition: brands built for the internet first, not retrofitted later.

Financially, the post-pandemic period wasn’t a clean upward line. In 2024, Carter’s revenue was $2.84 billion, down 3.45% from $2.95 billion the prior year. Earnings were $181.83 million, down 20.33%.

Leadership was changing, too—and with it, potentially the company’s emphasis. In March 2025, Carter’s tapped Douglas Palladini from Vans as its new President and CEO. “I am very proud to join Carter’s as its new CEO,” Palladini said. “Carter’s is one of America’s most iconic companies and I am sincerely grateful to our Board of Directors for the faith it has placed in me to return Carter’s to consistent, profitable growth.” His background in athletic footwear and apparel suggested a fresh perspective, and perhaps a more brand-centric, marketing-driven approach.

Then there was the external shock Carter’s couldn’t optimize its way around: tariffs. The company said higher tariffs had “weighed meaningfully” on profits, and it expected about $200 million to $250 million a year in additional costs. That hit landed especially hard because Carter’s sourced primarily from Asia—China, Vietnam, Cambodia, Indonesia, and Bangladesh. Carter’s estimated the gross pre-tax earnings impact of additional import duties at roughly $125 million to $150 million on an annualized basis. In plain terms, those costs had to go somewhere: absorbed through thinner margins, passed along via higher prices, or mitigated by reshaping the supply chain.

The impact showed up in results. Carter’s operating income fell more than 62% over the first three fiscal quarters of 2025 compared to the same period the year before. The numbers were stark, even as management stressed that comparable sales had stabilized and that its strategic initiatives were beginning to take hold.

IX. The Business Model & What Makes Carter's Special

So what actually protects Carter’s in a world where anyone can launch a baby brand on Shopify and sell it through Instagram? If you’re trying to judge Carter’s durability, this is the whole game.

Brand equity is the clearest answer—and it’s not abstract. One market research firm found that “ninety percent of millennial parents — and 80 percent of baby boomer grandparents — have shopped at Carter’s in the past year.” That’s not just awareness. That’s a hand-me-down habit. When you’re a new parent and you’re uncertain about everything, you don’t want “the most innovative” onesie. You want the one you trust. Carter’s has been earning that reflex for more than 160 years.

Product-market fit is the other quiet superpower here. Parents don’t get to opt out of buying baby clothes. Kids grow, seasons change, and the basics wear out. In the first year especially, babies move through sizes fast—often every few months—which turns childrenswear into something closer to a recurring need than a discretionary splurge.

Distribution is where Carter’s starts to separate from the wave of smaller, digitally native competitors. The company isn’t betting on a single channel. It sells through its own stores, its own e-commerce sites, and wholesale partnerships with essentially every major North American retailer. That scale shows up in reach: Carter’s operates in about 18,800 wholesale locations across department stores, national chains, and specialty stores. Most challengers simply can’t match that kind of omnichannel footprint.

Operational excellence is the less visible edge, and it’s a legacy of the Berkshire-era rebuild. Carter’s learned to run tight—managing inventory, working capital, and cash flow with discipline—and that matters in apparel, where too much product in the wrong place can wreck a year.

And then there’s customer lifetime value. Carter’s doesn’t just want one purchase; it wants the family. The ideal story is that it meets parents at birth and keeps them buying through age 10 and beyond—different sizes, different seasons, different life moments, same relationship.

Put it together, and the economics can look surprisingly attractive for a specialty retailer. Gross margins benefit from the value of the brand and the design work layered on top of simple products. Scale in sourcing, marketing, and distribution helps keep operating costs efficient. And capital requirements stay relatively modest compared to businesses that have to build factories or fund heavy equipment.

This is why baby clothes can be a great business, even if it looks boring from the outside: necessity demand that tends to hold up in downturns, repeat purchasing because kids keep growing, emotional involvement because parents will spend on their kids, and a category where “good enough” still has to clear a trust bar.

Challenges abound nonetheless. The U.S. fertility rate dropped to an all-time low in 2024, with fewer than 1.6 children being born per woman. In the early 1960s, the U.S. total fertility rate was around 3.5, but it fell to 1.7 by 1976 after the Baby Boom ended. That’s the hard, structural headwind: fewer babies means fewer baby clothes, no matter who wins share.

On top of that, there’s deflationary pricing pressure from fast fashion players like Shein, which makes it harder to raise prices even when costs rise. Differentiation has limits—there’s only so much you can reinvent a onesie. And while the heavy debt load from the private equity era has come down, it still reduces flexibility compared to a balance sheet built for maximum optionality.

X. Strategic Frameworks: Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: Medium-High. Starting a baby clothing brand has never been easier. If you have a decent design point of view, a contract manufacturer, and a Shopify store—or a listing on Amazon—you’re in business. The hard part is everything after launch: earning trust from nervous new parents, winning distribution at scale, and staying relevant long enough to become a default. New brands can take bites out of the market, but breaking through the way Carter’s has is rare.

Supplier Power: Low. Carter’s sources primarily through contract manufacturers in Asia, and there are plenty of them. With hundreds of factories competing for business, Carter’s scale and professional sourcing organization give it leverage. In most cases, suppliers need Carter’s volume more than Carter’s needs any single supplier.

Buyer Power: Medium-High. Parents are price-sensitive, and online shopping makes comparison effortless. At the same time, Carter’s doesn’t just sell to parents—it sells through giant wholesale partners. Retailers like Walmart and Target have real negotiating power because they control shelf space and can demand sharp pricing or exclusives. The limiting factor is loyalty: when parents are in “I just want something I trust” mode, they’ll often pay a little more for Carter’s.

Threat of Substitutes: Medium. Babies grow fast, which makes secondhand clothing a perfectly rational substitute. Hand-me-downs and consignment are especially attractive for budget-conscious families. Then you have ultra-low-cost basics from players like Shein and Amazon Essentials that can meet the “good enough” threshold on price alone. The threat is meaningful, but it’s capped by what parents will tolerate on quality and safety for the clothes touching their kids’ skin.

Competitive Rivalry: High. This is a crowded, unforgiving category. Target’s Cat & Jack, Gerber products at Walmart, Gap Kids, Old Navy, and DTC brands like Primary all compete aggressively for the same families. Carter’s also faces broader apparel players like American Eagle Outfitters, Abercrombie & Fitch, SHEIN, Hennes & Mauritz, and Aeropostale—among many others. When the product is a basic onesie, price pressure is constant and true differentiation is hard to sustain.

Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis

-

Scale Economies (Moderate): Carter’s can spread procurement, distribution, and marketing costs across nearly $3 billion in revenue, which gives it an edge versus smaller brands. But apparel isn’t software—scale helps, just not in a winner-take-all way.

-

Network Effects (None): Kids’ clothing doesn’t get better because more people buy it. There’s no network effect here.

-

Counter-Positioning (Historical, Fading): The private-equity-era turnaround let Carter’s out-execute competitors stuck in old habits. But success cuts both ways: today, Carter’s is the incumbent, and it’s the one that can be counter-positioned by internet-native brands built around a different model.

-

Switching Costs (Low): Switching baby brands is easy. No contracts, no learning curve, no meaningful friction.

-

Branding (Strong): This is the core advantage. Carter’s has multi-generational trust, emotional resonance at stressful parenting moments, and a credible claim to “baby’s first outfit.” But branding is not a set-it-and-forget-it asset. If quality slips or the brand stops feeling current, it can erode.

-

Cornered Resource (None): Carter’s doesn’t control unique IP, exclusive materials, or scarce assets that lock competitors out.

-

Process Power (Moderate): The company’s operational discipline—supply chain execution, inventory management, and omnichannel fulfillment—creates real, embedded know-how. It’s hard to replicate quickly, but it’s not exclusive.

Verdict: Carter’s strength comes primarily from Branding, with Scale Economies and Process Power providing meaningful support. The moat is real, but it isn’t permanent. It has to be maintained—by staying trusted, staying relevant, and continuing to execute.

XI. Bull vs. Bear Case & Future Outlook

The Bull Case

Carter’s has already lived through the kinds of shocks that kill most retail brands: depressions, wars, the rise of mass merchants, a bankruptcy-era near-death, and the Amazon and COVID gut punch. And it’s still here. That kind of longevity doesn’t happen by accident. It’s the proof that the brand means something—and that parents keep reaching for it when they want the safe, familiar choice.

Demographics are still a headwind, but there are at least signs of stabilization. In 2024, 3,628,934 births were registered in the United States, up 1% from 2023. Fertility rates remain low, but the absolute number of births has steadied. Immigration also continues to add younger families to the U.S. population, partially offsetting the broader decline in native birth rates.

Then there’s the biggest operational shift of the last decade: digital. COVID didn’t just push Carter’s to improve its e-commerce game—it forced it to. And coming out the other side, the company’s online capabilities are no longer a glaring weakness. With omnichannel fulfillment, Carter’s can offer convenience that pure online brands can’t always replicate, especially when speed and flexibility matter.

There’s also still an expansion story, even if it’s more “option” than “certainty.” Carter’s remains overwhelmingly North American. Europe, Asia, and much of Latin America are still lightly tapped. If global middle-class families increasingly seek trusted Western childrenswear brands, Carter’s has room to grow its addressable market.

And the Berkshire-era legacy still shows up where it counts: the ability to generate cash. Even with revenue pressure, Carter’s has continued to run the business with operational discipline and maintain investment-grade credit. The company ended the third quarter with no seasonal borrowings and more than $1 billion in liquidity—real breathing room in a retail environment where many brands live quarter to quarter.

Put all of that together with a stock price weighed down by tariffs and top-line concerns, and you can see the bull argument: for long-term investors, the market may be pricing Carter’s like a deteriorating legacy retailer, even as the company looks more like a hardened operator with a trusted brand and a functioning digital engine.

The Bear Case

The bear case starts with a reality Carter’s can’t out-execute: fewer babies. In 2024, the U.S. recorded its lowest ever fertility rate, at 1.6 births per woman, continuing a long decline that began in the early 2000s. That’s not a cyclical slump. It’s a structural contraction in the core market. If the total number of kids shrinks, every brand fights harder for every purchase.

At the same time, the category is being commoditized from both ends. Amazon and mass merchants have turned baby basics into a price-transparent, easily substitutable product. Target’s Cat & Jack, Walmart’s Gerber offerings, and Amazon’s Simple Joys give parents “good enough” at a lower price—and they control the shelf space, the search results, and the promotions.

Digitally native DTC brands add another layer of pressure. They speak the language of younger parents—discovered on Instagram, not recommended by a grandmother—built around lifestyle marketing, design point of view, and values-first storytelling. Carter’s can compete, but it’s competing on terrain that doesn’t naturally favor incumbents.

Then there’s ultra-fast fashion. Temu and Shein have pushed pricing expectations down even further, offering trendy designs at levels Carter’s can’t sustainably match without sacrificing margins.

And the financial impact has already shown up. Operating income fell 62% to $29.1 million from $77.0 million year-over-year, and operating margins dropped to 3.8% from 10.2% in 2024. That’s not just noise. It’s evidence that when cost shocks hit—like tariffs—or when demand softens, the model can get squeezed fast.

Finally, there’s the question of differentiation. Baby clothes are, by definition, simple. There’s only so much reinvention available when the core products are cotton bodysuits and pajamas. In a world where competitors can copy designs quickly and undercut on price, the brand and the distribution have to do most of the work—and those advantages aren’t invincible.

Key Performance Indicators to Watch

For investors following Carter’s, two metrics matter most:

1. Comparable Store Sales (Comps): This measures organic demand, stripping out the noise of store openings and closures. Positive comps can indicate share gains or better pricing; negative comps can signal weakening demand. U.S. Retail comparable net sales increased 2.2% in recent quarters, which is a meaningful bright spot amid broader challenges.

2. E-Commerce Penetration and Growth: As physical retail faces structural pressure, Carter’s long-term trajectory depends on digital. Watch e-commerce as a share of total sales and the direction of year-over-year growth. If growth slows materially, it’s often an early warning that competitors are winning the online battlefield.

XII. Epilogue & Final Reflections

Carter’s story is a reminder that business durability doesn’t always look exciting. Sometimes it looks like a drawer full of onesies.

“Boring” businesses, done extremely well, can produce extraordinary results over time. Baby clothes will never dominate headlines the way AI or EVs do. But parents keep buying them—year after year, generation after generation. In a category like that, steady demand doesn’t just persist. It compounds.

For founders and operators, Carter’s is a clean equation: brand plus operational excellence plus adaptability equals survival. The company came close to dying in 2001 not because parents stopped trusting the label, but because the execution underneath the label stopped working. The brand created a second chance. The turnaround required rebuilding the engine. Neglect either one long enough, and the business breaks.

For investors, the lesson is equally sharp: iconic brands are not invincible. Berkshire Partners’ 2001 intervention wasn’t guaranteed to work, and plenty of household names never make it back from the edge. Private equity can create enormous value through operational improvement—but only if there’s real brand equity worth saving in the first place.

That’s what made Carter’s special. The company sells necessity goods, and it sells them with multi-generational trust. As the company itself put it, “During his tenure, the Company has strengthened its position as the market leader in young children's apparel and has grown significantly through the creation of new brands and new channels of distribution including retail stores, eCommerce, and our international businesses.”

Zoom out, and Carter’s is also a story about American retail itself: the move from department stores to mass merchants to e-commerce, and the wreckage that shift left behind. The survivors tend to share a few traits: a willingness to cannibalize old channels before someone else does, investments made ahead of inflection points, and an almost stubborn focus on what customers actually need.

So what’s next? Sustainable and adaptive clothing offer real room for product innovation. Global expansion remains a potential growth lever. And the millennial and Gen Z parent generation will decide whether Carter’s trust transfers cleanly to yet another cohort.

As Carter’s has said, “The strength of our brand assets, broad market distribution, substantial equity with generations of consumers, and our talented team represent significant advantages to drive long-term growth.” The open question is whether those advantages translate into sustained value creation in a tougher, more price-transparent world.

The best businesses are often hiding in plain sight—sometimes they’re literally clothing your baby. Carter’s has done that for 160 years. Whether it does it for another 160 will come down to the same thing that saved it before: the willingness to change before it has to.

XIII. Further Reading & Resources

If you want to go deeper on Carter’s—beyond the headlines and into the mechanics of how this business actually works—these are the best places to start:

-

Carter’s, Inc. Investor Relations (ir.carters.com) — The annual reports (10-Ks) are the cleanest way to track the company’s evolution, especially across the 2001–2025 stretch: restructuring, channel strategy, acquisitions, digital investment, and how the numbers moved as the model changed.

-

Harvard Business School Case: “Berkshire Partners: Bidding for Carter’s” — A detailed, classroom-style look at the 2001 leveraged buyout and the private equity logic behind fixing an iconic but broken brand.

-

SEC EDGAR filings — The primary-source record: proxy statements, quarterly reports, and major disclosures. If you want the unfiltered version of what happened and when, this is it.

-

The End of Fashion by Teri Agins — A great lens on the broader apparel industry and the mass-merchant shift that reshaped pricing, margins, and power dynamics—exactly the forces that squeezed Carter’s in the first place.

-

Women’s Wear Daily (WWD) and Retail Dive — Trade coverage that’s especially useful for tracking childrenswear trends, competitive moves, and the real-time pressure points in retail.

-

CDC birth data and U.S. Census Bureau demographics — The demand curve for baby clothes starts with births. These datasets help you understand the structural headwinds and tailwinds that no amount of execution can fully escape.

-

Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers framework — A helpful way to pressure-test whether Carter’s advantages are durable—or just the result of being big and familiar.

-

Private equity industry resources — For understanding the LBO mechanics and value-creation playbooks that shaped Carter’s post-2001: leverage, operational fixes, cash generation, and the discipline behind the turnaround.

-

Company conference call transcripts — Often more revealing than press releases. These capture management’s real-time view of pricing, inventory, traffic, wholesale relationships, and the push-and-pull between DTC and partners.

-

Target, Walmart, and Amazon investor materials — Carter’s doesn’t operate in a vacuum. These sources provide context on private-label strategy, retail priorities, and the channel power that shapes Carter’s wholesale reality.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music