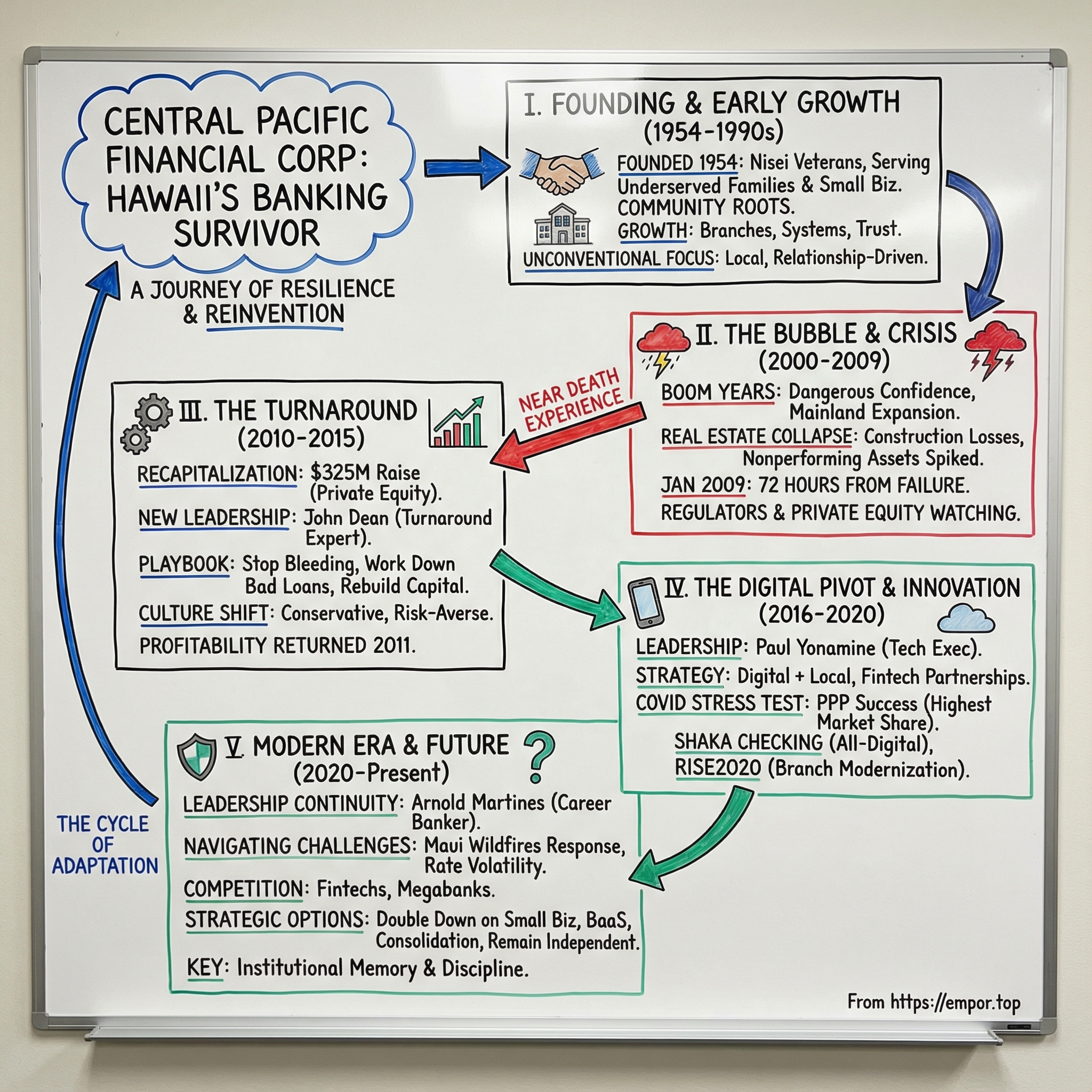

Central Pacific Financial Corp: Hawaii's Banking Survivor

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture this: January 2009. In a nondescript conference room in Honolulu, Central Pacific Financial Corp’s executives sit locked on a speakerphone, waiting on the people who decide whether a bank lives or dies. On the other end: federal regulators. And a few of the biggest names in private equity.

Central Pacific is Hawaii’s third-largest bank, with more than $6 billion in assets. But none of that matters in the moment, because the math is brutally simple: the bank has about 72 hours to raise more than $300 million in fresh capital. Miss that deadline, and regulators will move in Friday night. By Monday morning, Central Pacific’s 850 employees and tens of thousands of customers won’t be banking with Central Pacific anymore. They’ll be another entry in the growing list of Great Financial Crisis casualties.

This is the story of how a scrappy community bank—founded in 1954 by local businessmen who wanted to serve small businesses and working families the big Hawaii banks overlooked—ended up on the edge of the abyss. And then, against the odds, fought its way back. Not just to survive, but to reinvent itself into something few would’ve predicted in 2009: a conservative, battle-scarred bank that later found a second act by leaning into digital banking.

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture this: it’s January 2009, and in a nondescript conference room in Honolulu, Central Pacific Financial Corp’s executives are staring at a speakerphone like it’s a life-support machine. On the other end are federal regulators—and a few of the biggest names in private equity.

Central Pacific, Hawaii’s third-largest bank, has roughly 72 hours to raise more than $300 million in fresh capital. Miss that window, and regulators step in Friday night. By Monday morning, Central Pacific’s employees and tens of thousands of customers won’t be banking with Central Pacific anymore. They’ll be another entry on the Great Financial Crisis casualty list.

This is the story of how a scrappy community bank—founded in 1954 to serve local families and small businesses the giants overlooked—ended up on the edge of failure. And then, against the odds, clawed its way back. Not just to survive, but to become something few would’ve predicted in 2009: a conservative, battle-tested bank that later found an unexpected second act in digital banking. Today, Central Pacific Financial Corp. is a Hawaii-based bank holding company with approximately $7.47 billion in assets.

The question that drives everything: how does a regional community bank survive the 2008 crisis when it’s hours from being shut down—and then emerge as one of the most aggressive digital banking innovators in its market?

The answer sits at the intersection of place and trauma. Hawaii is a geographic moat—banking on paradise, quite literally—but it’s also a small, concentrated economy where mistakes get magnified fast. Central Pacific’s near-death experience rewired its culture around risk. And a later leadership transition pushed the bank to modernize in ways its larger rivals didn’t have to—until they did. Along the way, the company was recognized as one of America’s Best Regional Banks by Newsweek, one of the Best in State Banks by Forbes, and the Best Bank in Hawaii by readers of the Honolulu Star Advertiser.

We’ll walk through Hawaii’s peculiar banking landscape, the founding story, the boom years that bred dangerous confidence, the crisis that almost destroyed the franchise, and the hard, surprising reinvention that followed. And we’ll test the big idea underneath it all: does Hawaii’s uniqueness create a durable advantage for a local bank—or does it simply slow down the consolidation that’s swallowing regional banking everywhere else?

For investors, Central Pacific is a rare case study in institutional memory: a company that learned the most expensive lesson possible about concentration and risk, came out more conservative and more digitally capable, and now faces the same existential question hanging over every regional bank. In an era of fintech disruption and megabank gravity, can a roughly $7 billion community bank on an isolated set of islands survive—and thrive?

II. Hawaii's Unique Banking Landscape & Founding Context

Walk through downtown Honolulu’s financial district today and you’ll see three names everywhere: First Hawaiian Bank, Bank of Hawaii, and Central Pacific Bank. But in the early 1950s, the landscape looked very different—and for a lot of local families, it felt closed.

Hawaii’s banking market has always been its own ecosystem. Start with the obvious: an island chain about 2,400 miles from the mainland. The economy is unusually concentrated, heavily tied to tourism and military spending, with a cost of living that squeezes households and small businesses. And because there are only so many people—barely more than 1.4 million—the market is tight: relationships matter more, reputations travel faster, and when the economy turns, there’s nowhere to hide.

Statehood in 1959 poured gasoline on growth. Tourism surged, deposits rose, and the islands needed construction loans, business credit, and mortgages to build the Hawaii the world now recognizes. But the demand for a new kind of local bank didn’t start with statehood. It started with what happened after World War II.

Before the war, Japanese-managed banks served many immigrant and Japanese-American families. After Pearl Harbor, those banks were shut down and seized. When the war ended, members of the Japanese-American community said they still didn’t have adequate access to financial resources. In other words: the money was there, the entrepreneurs were there, the families were there—but the system wasn’t built for them.

That created a market gap, and something deeper than a business opportunity. Central Pacific Bank was founded by Japanese-American nisei—second-generation Americans—many of them veterans of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, the 100th Infantry Battalion, and the Military Intelligence Service. Future senator Daniel Inouye was among them. These weren’t people asking for a favor. They were men who had proven their loyalty to the United States in the most literal way possible—then came home and found doors still closed.

The 100th and the 442nd became two of the most decorated units of the war. The MIS—Japanese-American linguists and intelligence specialists—helped crack documents and interrogations that are credited with shortening the war in the Pacific. And yet, back in Hawaii, many of these veterans still faced the same inequities their families had lived with before the war.

So they started meeting. Not in boardrooms—at Ala Moana Beach Park, over 50-cent plate lunches. Names like Daniel Inouye, Sakae Takahashi, Elton Sakamoto, and others kept showing up, week after week, to talk through an idea that sounded almost naive in its ambition: build a bank that would serve all of the people of Hawaii.

Even the name carried a thread of history. “Central Pacific Bank” echoed Pacific Bank, a Japanese-managed bank that had been shut down when the war began. The message was clear: this was a continuation of something that had been interrupted—and a response to what came after.

To make the dream real, the group widened the circle. They reached out to issei—first-generation—business leaders, which led them to a relationship with Sumitomo Bank. Then they did the hard part: they raised $1 million in capital through grassroots efforts across the islands. With that funding, plus managerial assistance from Sumitomo, Central Pacific Bank received its charter on January 29, 1954, and opened for business on February 15, 1954.

It opened on the corner of King and Smith streets—Hawaii’s first new bank since 1935. And the community showed up immediately. In its first year, CPB generated more than $5 million in deposits, grew to $6.4 million in assets, and earned a very small profit. For a bank built by outsiders, that early traction was the point: people had been waiting for an institution that felt like it belonged to them.

The leadership structure reflected the coalition that created it. Koichi Iida, a prominent issei merchant in Honolulu and one of the founders, became the first CEO. The Sumitomo relationship mattered, too—so much that the next two CEOs were seasoned executives from within the Sumitomo Bank system.

That connection gave CPB something invaluable: experienced operators, a conservative banking tradition, and international relationships. It also made CPB a little different from the start—more patient, more relationship-driven, and more focused on the small businesses and families that the entrenched players had historically underserved.

By the time Hawaii became a state in 1959, CPB had five branches, including its downtown headquarters. The boom was about to begin—and a bank that was only five years old was positioned to grow right alongside it.

For investors trying to understand Central Pacific’s culture today, this origin story isn’t trivia. It’s the blueprint. CPB was built by people who knew what it meant to be excluded, who raised capital the hard way, and who won customers through trust. That underdog DNA—relationship-first, community-rooted, built from nothing—still echoes through the franchise decades later, even as the company has grown into a roughly $7.5 billion bank holding company.

III. Growth Years: Building a Hawaii Franchise (1960s–1990s)

The decades after statehood were Hawaii’s long boom—and Central Pacific grew up with it. As the islands shifted from agriculture to tourism, CPB kept doing the unglamorous work of becoming a real modern bank: adding branches, upgrading systems, and steadily widening the circle of customers who felt welcome walking through its doors. By 1979, the bank had grown from $6.3 million in assets at launch to $410.9 million.

That kind of growth is impressive anywhere. In Hawaii—where two incumbents had been entrenched for generations—it was a statement.

First Hawaiian Bank dated back to 1858 and sat at the top of the market. Bank of Hawaii was right behind it, the biggest bank owned locally. They had the brand, the history, the big corporate relationships, and the balance sheets. CPB didn’t. So it competed the only way an underdog can: by going where the giants weren’t looking.

The Big Two were built around Hawaii’s plantation-era power structure—large employers, big commercial clients, and wealthy families. CPB leaned into the opposite end of the market: small businesses, working families, and customers who were used to being treated like they didn’t quite belong. In a place as small as Hawaii, that mattered. When you build a bank around relationships, reputations spread fast, and loyalty can last for decades.

And CPB’s success had ripple effects beyond banking. Its very existence—and the customer base that formed around it—helped accelerate broader acceptance of Japanese and other ethnic communities across Hawaii’s business life. The bank wasn’t just taking deposits and making loans. It was helping pull down barriers that had lingered since the war.

As the franchise expanded, the bank put down a physical marker of permanence. In 1981, CPB began construction on a new downtown Honolulu headquarters. The building was completed in 1982, and in February 1983 the bank moved in. Central Pacific Plaza became a fixture of the skyline—and it remains the company’s headquarters today.

The tech upgrades came in practical steps. In 1990, CPB joined the ATM Plus network, expanding access to ATMs. In 1992, it introduced phone banking. Nothing flashy—just the steady modernization required to keep a community bank competitive.

But even in these growth years, Hawaii imposed a constraint that mainland bankers rarely feel: there’s no obvious next market. A regional bank in California can push into Arizona or Nevada. In Hawaii, expansion usually means one of three things: take share from entrenched rivals, buy another local institution, or try your luck on the mainland. And that last option had a nasty track record.

The Big Two tried it anyway. In 1987, Bank of Hawaii bought First National Bancorp of Arizona, based in Phoenix. In 1996, First Hawaiian acquired 31 branches across Oregon, Washington, and Idaho from U.S. Bancorp and placed them into a new subsidiary called Pacific One Bank. Hawaii banks kept learning the same lesson the hard way: what works on the islands doesn’t always translate across an ocean.

CPB watched those moves closely. The takeaway seemed clear—Hawaii banking was different, and “mainland adventures” often ended badly. It’s a lesson that will matter later, because the bank’s real trouble didn’t come from crossing the Pacific. It came from forgetting its own conservative instincts once the 2000s made risk look like opportunity.

One more thread from the founding era also shaped CPB’s trajectory. Central Pacific was one of two Hawaii banks started in the 1950s by nisei war veterans to serve the Japanese-American community. The other was City Bank, founded in 1959. Over time, the market consolidated—and Central Pacific ultimately became the survivor. In September 2004, CPB acquired City Bank for $423.1 million in cash and stock.

The timing mattered. The deal landed as the real estate market was heating up. Overnight, CPB was bigger, broader, and more capable of taking on the Big Two. Around this period, Central Pacific Financial Corp.’s stock began trading on the New York Stock Exchange. And with the City Bank combination, Central Pacific Bank became a roughly $5 billion institution.

That shift—from a private, community-rooted bank to a larger, publicly traded one—changed the internal physics of the business. Now there were quarterly expectations. Analysts wanted growth. Investors wanted a story. The patient, relationship-first model that built CPB over 50 years started to feel slow, even old-fashioned.

And the leadership culture was changing, too. In 2002, Clint Arnoldus became CEO—the first non-Sumitomo chief executive. The Sumitomo era, with its conservative Japanese banking traditions, was fading out at exactly the wrong time: just as the biggest credit bubble in modern American history was beginning to inflate.

IV. The Bubble & The Build-Up to Crisis (2000–2007)

The mid-2000s real estate boom hit Hawaii like a high tide that just wouldn’t stop rising. Tourism was strong. Mainland buyers, flush with home equity, were scooping up vacation properties. Developers seemed to have a new condo project in the ground every time you turned around. And for Central Pacific—now public, bigger after the City Bank deal, and living under the glare of quarterly expectations—the moment felt like a mandate: grow.

But the bank’s biggest bet wasn’t just that Hawaii real estate would keep climbing. It was that Central Pacific could take its playbook across the ocean and win on the mainland.

Years later, when John Dean came out of retirement in March 2010 to help stabilize the business, he pointed to that decision as the core mistake. Central Pacific, he said, had entered the mainland roughly a decade earlier to chase “robust loan growth,” and did it at the worst possible time—right before the real estate market collapsed. The loan losses that were bleeding the company were tied largely to construction and land development in mainland states such as California.

That’s the crucial context for what follows: Central Pacific didn’t just take on too much construction risk. It took on that risk in markets where it didn’t have the relationships, the local knowledge, or the community ties that had always been its edge back home. Hawaii’s insularity and relationship density—two things that had historically protected the franchise—got traded for growth.

The competitive dynamics made the temptation easier to rationalize. Bank of Hawaii, under different leadership, had tried a similar growth path earlier. It got burned, took severe losses, and pulled back. Central Pacific, in a sense, arrived late to the mainland expansion game—just as the music was about to stop.

Then the broader system cracked.

The 2008 financial crisis produced a wave of bank failures across the United States. The FDIC closed 465 failed banks from 2008 to 2012. In the five years before 2008, only 10 failed. And the pattern was clear: the banks that got hit the hardest were the ones loaded with construction and development lending, especially those that had stretched beyond their core markets.

The long calm of the Great Moderation ended when U.S. housing activity peaked in 2006 and residential construction started falling. By 2007, losses on mortgage-related assets were spreading stress through global markets. In December 2007, the U.S. economy entered a recession, and major financial firms began to wobble.

For Central Pacific, the problem was painfully specific. Construction and development loans only work when time is on your side—when projects keep moving, buyers keep buying, and prices keep rising. When that motion stops, the collateral becomes the worst kind of security: half-finished buildings and raw land worth far less than the loan balance. Projects stalled. Borrowers defaulted. Losses accelerated.

The bank’s stress showed up in its nonperforming assets. Among six Honolulu banks reporting first-quarter results, the median ratio of nonperforming assets to total assets was 3.3%, versus a national median of 1.8% at March 31. Central Pacific’s ratio was 13.1%, the second-highest in that local group—down from 17.1% a year earlier. Its net income improved sharply from the prior year’s $160.2 million loss, but the headline didn’t change: this was a balance sheet under siege.

Put differently: even after “improving,” more than one out of every eight dollars of assets wasn’t performing. At the worst point, it was closer to one out of every five. That’s not a bad quarter. That’s an institution edging toward insolvency.

Dean later put it plainly: “If you look at the goodwill write-off, we had over $700 million in losses, so we were running out of capital. And, if you remember, there were a lot of people chasing capital at that time.”

And then came the week that turned a crisis into a stampede.

On September 15, 2008, Bank of America announced its intent to buy Merrill Lynch for $50 billion. That same day, Lehman Brothers filed for Chapter 11. Credit markets seized up. Liquidity became a scarce resource, and scarce resources don’t flow to a regional bank carrying heavy construction exposure.

For Central Pacific, the cascade was brutal. Lehman’s collapse froze credit. The shock hit tourism. Hawaii’s economy weakened. Borrowers fell behind. Losses ate capital. And just when the bank needed the market’s confidence to raise money, the market had no confidence to give.

A bank that had stretched for growth now discovered what stretching really means: when the tide goes out, you find out how thin the cushion is.

V. The Financial Crisis: 72 Hours from Failure (2008–2009)

“The toughest challenge was recapitalizing the bank,” John Dean would later say. When he came out of retirement in 2010 to help rescue Central Pacific, he wasn’t naïve about what he was walking into. This was his fifth bank and his fourth CEO turnaround. He understood exactly what Central Pacific needed most—and how impossible it would be to raise it in the wreckage of the financial crisis.

By early 2009, the bank was operating under a consent order from regulators: a formal, public signal that capital had to be raised fast, or the FDIC could step in. These orders aren’t gentle nudges. They’re countdown clocks. In banking, they usually end one of two ways: a successful recapitalization—or a Friday night closure.

Central Pacific was trying to buy time. In a press release, the roughly $4.2 billion-asset Honolulu company said it had been working with a private equity investor on a $98 million infusion and was trying to finalize an agreement “by the end of the week.” At the same time, the company entered into an agreement with state and federal regulators requiring it to submit a capital restoration plan within 60 days.

The numbers around the bank made the situation stark. Central Pacific had lost roughly $700 million over three years—losses that would have sounded absurd back when the same leadership team was reporting record profits. Nonperforming assets had climbed past 17% of total assets. The stock, once around $40 a share before the crisis, had fallen to under $2.

The turnaround architect officially arrived in March 2010. Dean joined as Executive Chair and arranged a $325 million recapitalization backed by private equity. Under his watch, the company returned to profitability in the first quarter of 2011, and he helped drive the divestment of the bank’s troubled assets.

To understand why the board went looking for Dean—and why investors would later back him—you have to understand his résumé. He’d spent decades in financial services and was credited with turning around four major banks. He graduated from Holy Cross, served as a Peace Corps volunteer in Western Samoa, and earned an MBA in finance from Wharton. Business Week named him one of Silicon Valley’s top 25 “movers and shakers” in 1997. Forbes called him one of the “50 most powerful dealmakers” in 2001.

From 1993 to 2001, Dean was CEO of Silicon Valley Bancshares and Silicon Valley Bank. Over that stretch, Silicon Valley Bank grew from under $1 billion in assets to more than $5 billion, and its market capitalization climbed from tens of millions to the billions. He’d seen what it looked like when a bank was bleeding, under a regulatory order, and written off by the market—and he’d seen what it looked like when that story flipped.

But the most revealing part of why he took Central Pacific wasn’t a deal stat. It was a conversation at home.

“I talked to Sue,” Dean said, referring to his wife. “And she said, ‘How many employees are there?’ And I said about a thousand. And she said, ‘What happens if the bank doesn’t make it?’ And I said, ‘Unfortunately, most of them are going to end up on the street.’ And Sue said, ‘Then you’ve got to go do it.’”

The rescue ultimately came from an unlikely place for a Hawaii community bank: private equity. Central Pacific Financial Corp. announced definitive agreements with The Carlyle Group and Anchorage Capital Group, L.L.C. Under the deal, each lead investor agreed to invest about $98 million in common stock. Those investments were the anchor for an expected $325 million capital raise from institutional and other investors.

The terms were brutal for existing shareholders—but that’s the trade when regulators are standing at the door. Carlyle and Anchorage would each own 24.9% of the company’s common stock prior to giving effect to the rights offering. The shares were priced at $0.75 per share for an aggregate $195 million. Each investor also received a board seat at both the company and the bank.

Seventy-five cents a share—for a stock that had traded above $40 just three years earlier. That wasn’t a bargain. It was the price of survival when you’re days away from seizure.

The capital raise was completed in early 2011. On February 18, 2011, the company closed a private placement with investments from affiliates of Carlyle Financial Services Harbor, L.P. and Anchorage Advisors, L.L.C. As part of the planned recapitalization, Carlyle and Anchorage each put $98 million into Central Pacific Financial, each ending up with a 24.9% stake and a board seat.

So why did Central Pacific survive when hundreds of other banks didn’t?

Part of it was size. At roughly $4 to $5 billion in assets at the time, the bank was large enough to attract sophisticated investors—but still small enough that private capital could realistically fill the hole. Smaller banks often couldn’t pull in institutional money; larger banks required government-scale solutions.

Part of it was timing. By early 2011, the panic phase had eased and private equity had started actively hunting for distressed bank investments. Earlier, credit markets were frozen solid. Later, the cleanest opportunities would be gone.

And part of it was something harder to quantify: relationships. Even after its mainland missteps, Central Pacific still had deep ties to Hawaii’s business community and a founding mission that people remembered. That support—depositors who didn’t run, borrowers who worked through problems, a community that still wanted the bank to exist—provided a kind of stability that purely transactional institutions rarely get.

Then there was leadership. Dean’s arrival gave investors a credible operator with a reputation for executing turnarounds under regulatory pressure. He wasn’t selling hope. He was selling a playbook he’d already run.

“We want to go back to our roots,” Dean said. “There’s nothing wrong with being a homegrown community bank.”

VI. The Turnaround: From Basket Case to Boring Bank (2010–2015)

The recapitalization kept Central Pacific out of the FDIC’s hands, but it didn’t magically make the bank healthy. It still had a mountain of troubled loans, a cost structure built for a very different strategy, and a culture that—at the peak—had treated growth like a virtue and risk like a rounding error. Survival bought time. Now the bank had to use it.

The financials were still ugly. In the third quarter of 2010, Central Pacific Financial reported a $72 million loss. That was a meaningful improvement from the $183 million loss in the third quarter of 2009—but “less bad” is not the same as “good.” Losses were still draining the franchise, and regulators were still watching.

Dean’s playbook was simple, and it was going to hurt: stop the bleeding, work down the bad loans, rebuild capital by keeping what you earn, and reset the organization around conservative risk management.

As he put it: “So, the toughest thing for me was to get investors to believe our vision that, with $325 million, we could return the bank to profitability.”

Then something rare happened in bank turnarounds: the timeline pulled forward. Central Pacific returned to profitability in the first quarter of 2011—sooner than analysts expected. Joe Gladue at B. Riley & Co. said, “I wasn't expecting them to become profitable yet. … I had expected more so for it to occur in the third quarter.” Dean himself said he didn’t expect a profit that quickly either. The main drivers were lower credit costs and a smaller loan-loss provision.

But the speed didn’t mean the work was easy. It meant the bank had finally gotten past the phase where every quarter brought another wave of surprises. Much of the worst credit damage had already been recognized in 2009 and 2010—brutal at the time, but it cleared the deck. Hawaii’s economy also began to stabilize as tourism came back. And crucially, the $325 million capital infusion gave Central Pacific room to absorb remaining losses while still staying on the right side of regulatory requirements.

Dean was instrumental not just in getting the bank back to black, but in the unglamorous part that actually makes a turnaround stick: divesting troubled assets and driving asset quality back toward high performance standards.

The deeper shift was cultural. Central Pacific went from a bank willing to stray outside its core competencies to what it later became known as: the most conservative major bank in Hawaii. “Boring” wasn’t an insult anymore. It was the strategy.

The private equity exit captured the arc in one snapshot. Carlyle and Anchorage eventually sold their holdings—about 5.5 million shares in total—and exited their positions entirely. They sold at $22.15 per share. They had bought at $0.75. That kind of return is eye-popping, but it also underlines what was true in January 2009: this wasn’t a normal value investment. It was a rescue.

Dean’s role in that rescue—and what it meant for Hawaii—earned him Hawaii Business’ 2012 CEO of the Year.

Inside the company, the leadership structure evolved as the turnaround moved from emergency response to steady-state rebuilding. Dean served as Executive Chairman from June 2010 through April 19, 2011, then served as President and CEO from April 20, 2011 through May 31, 2014, while also remaining a director.

Even after he stepped away from day-to-day leadership, he stayed connected. Dean chose not to stand for board re-election at the April 2020 Annual Shareholders Meeting, retained the title of Chairman Emeritus, and continued supporting the bank through customer outreach, leadership development, and community engagement.

By the end of the turnaround era, post-crisis Central Pacific looked nothing like pre-crisis Central Pacific:

- A loan portfolio concentrated in Hawaii, with minimal mainland exposure

- Commercial real estate kept limited as a percentage of total loans

- Conservative underwriting institutionalized

- Regular stress testing embedded in decision-making

- Capital maintained well above regulatory minimums

For investors, this period created something more durable than a good quarter or a repaired balance sheet: institutional memory. What happened from 2008 through 2011 wasn’t a chapter the organization could forget. It became the filter for everything that followed—every growth plan, every credit decision, every internal debate that started with a simple, sobering sentence: remember what happened last time.

VII. The Digital Pivot: Unexpected Innovation (2016–2020)

If 2010 through 2015 was about surviving and stabilizing, the years that followed forced a different kind of question: in a world of fintech and megabanks, what does a small, island-based regional bank do to stay relevant?

Central Pacific’s answer came from a surprising place: not a career banker, but a technology operator who understood that the bank’s greatest limitation could be turned into leverage.

Paul K. Yonamine served as Executive Chairman of GCA Corporation, the largest independent M&A firm in Japan. Until March 2017, he served as the Country General Manager and President of IBM Japan, Ltd. Before that, he was President and CEO of Hitachi Consulting Co., Ltd., where he founded the first consulting and solutions business for Hitachi Ltd.

Yonamine—son of Hawaii-and-Japan baseball legend Wally Yonamine—had already been on the boards of Central Pacific Financial and Central Pacific Bank when he was named chairman and CEO of both in September 2018.

What he brought was something Central Pacific had never really had at the top: deep experience in technology strategy at global scale. And his core insight was counterintuitive. Hawaii’s geographic isolation, which limits how far you can grow by simply planting more branches, could actually accelerate the bank’s digital evolution. With nowhere to expand physically, CPB either had to win through digital channels—or accept stagnation.

That reframed the strategy. Instead of trying to build everything in-house—a slow, expensive path for a bank of this size—Central Pacific could partner. Fintechs could bring speed and customer-facing product; CPB could bring what fintechs often lack: a banking charter, regulatory infrastructure, and credibility built through local relationships.

Then COVID hit, and the bank got a stress test that doubled as a proving ground.

During the pandemic that began in 2020, CPB built an online portal for Paycheck Protection Program applications. The result: the highest market share of PPP loans disbursed by any bank in any state in the U.S.

That claim matters because PPP wasn’t a marketing contest. It was a race. Funding was limited and the program was first-come, first-served. The banks that could move fastest—collect documents, verify information, submit clean applications—captured the share.

Arnold Martines led CPB’s PPP effort. Under his leadership, the bank originated 11,833 PPP loans totaling $870 million—more loans than any other local bank. That represented 28% of all PPP loans made in Hawaii, the highest percentage of any bank in the nation.

Put simply: in a state where CPB was not the dominant player, it became the dominant operator when speed and digital process were the difference between “approved” and “missed it.”

The momentum wasn’t limited to PPP. The bank emphasized small business support more broadly, providing more U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA) loans than all other Hawaii banks combined, and becoming the first bank in the state to offer an online portal for SBA services.

Digital investment also moved into everyday consumer banking. In 2021, CPB launched Shaka Checking, Hawaii’s first all-digital checking account, and became the first Hawaii bank to offer a live chat feature with customer service representatives.

Shaka launched with a VIP waitlist campaign and what the bank described as the largest social media influencer campaign in Hawaii’s history. Since the product launch on November 8, 2021, more than 3,300 Shaka accounts were opened.

From there, Central Pacific pushed the logic even further. The company announced a Banking-as-a-Service initiative designed to expand the business in and beyond Hawaii by investing in, or collaborating with, leading fintech companies. The effort was built around the same product development and launch playbooks used for Shaka.

Beginning in the first quarter of 2022, the company continued the BaaS push with an equity investment in Swell, a fintech that planned to launch a consumer banking app combining checking, credit, and more into one integrated account, with Central Pacific Bank serving as the sponsor bank.

It was a pragmatic response to regional banking’s scale problem. CPB couldn’t outspend the megabanks on technology. But it could become the regulated backbone that fintechs needed, while keeping its own franchise modern and competitive at home.

And importantly, the “pivot” wasn’t only about apps. Central Pacific also rethought what a branch and a headquarters were supposed to feel like in a digital-first world.

In January 2020, the bank launched its RISE2020 initiative, aiming to update the main branch with an indoor-outdoor lanai, co-working spaces, and new retail space.

Martines also played a key role in implementing RISE 2020, a multi-faceted renovation and rebranding program that invested $40 million across branches, ATMs, and digital platforms, alongside redevelopment of Central Pacific Plaza—the bank’s landmark downtown Honolulu building.

For a bank of CPB’s size, that wasn’t a cosmetic refresh. It was a commitment: modernize the physical footprint, modernize the digital experience, and build a version of relationship banking that could live comfortably in both worlds.

VIII. Modern Era: Navigating New Challenges (2020–Present)

The post-pandemic years brought a different kind of test for Central Pacific: not survival in a crisis, but proving the reinvention could hold up in a harsher, faster-moving banking environment.

A key part of that story is leadership. Arnold Martines was appointed President and Chief Executive Officer of Central Pacific Financial Corp. and Central Pacific Bank on January 1, 2023, and Chairman of both on June 10, 2024.

Martines wasn’t a headline-grabbing outsider like John Dean, and he wasn’t a tech executive like Paul Yonamine. He was the inside-the-building pick: a career banker who started in the industry in 1995 at another Hawaii bank, then joined Central Pacific Bank in February 2004 and steadily moved up through both business-line and credit roles. Over the years, he held senior posts including Chief Banking Officer and President and Chief Operating Officer.

He also brought something else that matters in Hawaii: roots. Martines grew up in the small Big Island town of Paauilo, and his rise to the CEO seat capped a 27-year climb. More than anything, his appointment signaled continuity. This was the bank betting that the lessons of the crisis—and the discipline that followed—had to remain embedded at the top.

That continuity was tested almost immediately.

In August 2023, the Maui wildfires turned into a real-time stress event for every institution on the islands. For CPB, it was personal and operational at the same time. The bank’s Lāhainā branch and its three Lāhainā-based ATMs withstood the fire, but initially stayed closed due to power and data outages and accessibility issues.

Martines framed the bank’s posture in the language of its founding mission: “[Central Pacific Bank] was founded to help all of Hawaii's people with their financial needs and we are committed to helping the Maui community during this critical time.”

The response wasn’t just statements. The Central Pacific Bank Foundation donated $50,000 to the Hawaiʻi Red Cross to support victims. “Our hearts break for everyone on Maui who have been hit by the horrific fires and the CPB Foundation makes this donation in their honor,” Martines said.

Then came the operational proof. Central Pacific Bank announced the Lāhainā Branch would reopen on Monday, Aug. 28, 2023, after being closed since Wednesday, Aug. 9. When it reopened, it offered a full range of business and personal banking services. “We are heartbroken and grieve with our family and friends that have been impacted by the wildfire in Lahaina,” Martines said.

Behind the scenes, CPB offered relief through “the deferral of customers' residential, consumer and business loan and line payments,” and emphasized that it had “completely [stood] up our Lahaina Branch in 20 days to serve the financial needs of our customers,” adding, “We will look at more innovative ways to support the rebuilding efforts.”

The CPB Foundation also donated $50,000 to the Hawaii Red Cross and $25,000 to the Maui Food Bank. And the bank offered a Natural Disaster Loan Program, providing loans up to $10,000 at special rates with flexible terms for people impacted by the fires.

These aren’t the moves of a distant financial brand. They’re the moves of a community bank in a small market where trust is a real asset—and where showing up, quickly, is part of the business model.

Financially, CPB has been navigating the same macro forces hitting every bank—rate volatility, deposit competition, and shifting customer behavior—while trying to keep the post-crisis conservatism intact. The company reported adjusted net income of $19.0 million, or $0.70 per diluted share, for the fourth quarter of 2024, and $63.4 million, or $2.34 per diluted share, for the full year 2024.

Net interest margin was 3.17%, up 10 basis points from 3.07% the prior quarter—an indicator that CPB was able to reprice assets as rates stayed elevated.

Capital remained a defining feature of the “never again” era. Total risk-based capital and common equity tier 1 ratios were 15.4% and 12.3%, respectively—levels well above regulatory minimums and consistent with the conservative posture institutionalized after the crisis.

The board also signaled confidence in the bank’s footing: it approved a 3.8% increase in the quarterly cash dividend to $0.27 per share and authorized a new share repurchase program of up to $30.0 million for 2025.

There was also a noteworthy regulatory milestone: Central Pacific Bank became a member of the Federal Reserve System. Moving from state to Fed membership is a meaningful positioning choice, potentially bringing advantages like access to Federal Reserve lending facilities and deeper alignment with the Fed’s regulatory framework.

All of this is happening in an environment where CPB is still the underdog—and the pressure isn’t easing.

Competition in Hawaii comes from every direction. The Big Two are still there, with scale and brand gravity. National banks like Bank of America and Wells Fargo have a presence. And Bank of Hawaii has the most accounts, customers, branches, and ATMs of any financial institution in the state, even though First Hawaiian Bank holds a greater number of dollars in deposits.

Scale matters, too. First Hawaiian was listed on the NASDAQ on August 4, 2016, and debuted at number 12 in Forbes’ January 2017 list of America’s 100 Largest Banks with $20 billion in total assets. At roughly $25 billion today, it is more than three times CPB’s size.

In other words: Central Pacific’s modern era isn’t about outrunning the giants. It’s about staying disciplined, staying relevant, and proving that a bank forged in near-failure can still compete—on service, on technology, and on trust—when the easy growth is gone.

IX. Playbook & Business Model Deep Dive

To understand Central Pacific, you have to start with the thing that makes every Hawaii business a little weird: the market is both protected and boxed in at the same time.

Hawaii’s geography is a moat, and CPB benefits from it. The islands are far from the mainland, the economy is relationship-driven, and a lot of the most important banking work here still depends on local context—who the developers are, how collateral really trades, which businesses have staying power, and which ones are just riding a wave. That kind of knowledge doesn’t travel well through a call center on the continent.

But the same moat cuts the other direction. There’s no “next state over” for CPB to expand into. There’s no easy branch-by-branch march into a neighboring metro. Growth usually means taking share from the Big Two, buying a local institution, or trying the mainland again—an option Hawaii banks have learned to approach with scars and skepticism.

That constraint is why relationship density matters so much. In a state of roughly 1.4 million people spread across a handful of islands, reputations move fast. If you treat customers like numbers, people hear about it. If you show up when it counts, they remember that too. This is also why CPB’s origin story—the veterans, the grassroots capital raise, the mission of serving people who were excluded—still has power. In Hawaii, history isn’t a plaque in the lobby. It’s part of the brand.

Then there’s the post-crisis imprint. Central Pacific’s biggest competitive edge today may be the hardest to market: restraint. The bank won’t stretch to win business that requires aggressive underwriting. That means walking away from deals that might look attractive in the moment. It also means avoiding the kind of balance-sheet fragility that nearly wiped the company out. In a business where one bad credit cycle can undo decades of steady work, that institutional memory is a strategy.

On paper, CPB looks like a full-service community bank. It offers personal, business, and commercial banking services—checking and savings, loans and lines of credit, mortgages, credit cards, certificates of deposit, individual retirement accounts, plus wealth management services including insurance and trusts. But the practical center of gravity is small business. CPB has emphasized supporting local entrepreneurs, including originating more U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA) loans than all other Hawaii banks combined.

That matters because SBA lending is not “easy money.” It’s paperwork-heavy, process-intensive, and built on real underwriting and real relationships. It’s exactly the kind of business that pure digital challengers struggle to replicate, and it’s where a bank with local credibility can build a durable niche.

Over the last several years, CPB’s bigger bet has been what you could call digital-plus-local. The idea isn’t to out-fintech the fintechs or outspend the megabanks. It’s to offer modern convenience without giving up the relationship model that still wins in Hawaii. Products like Shaka Checking pull in customers who want a Hawaii-based digital account. From there, the bank has a chance to earn deeper relationships—mortgages, business credit, and wealth management—where local expertise and trust are harder to displace.

Even the way CPB thinks about capital allocation reflects the “never again” era. Dividends have grown, but not recklessly. Share repurchases are sized to what the bank can actually support. And balance-sheet growth is meant to be funded through retained earnings and discipline, not by reaching for risk or chasing hot money.

The hard part is talent. Hawaii is expensive, isolated, and competitive for skilled workers. Banking isn’t always the first choice for ambitious young people with options, and keeping experienced bankers costs real money—money that can pressure efficiency ratios at a bank CPB’s size. It’s a structural disadvantage versus fintechs that can hire globally and megabanks that can rotate talent through Hawaii as a desirable posting.

So CPB’s playbook isn’t mysterious, but it is demanding: protect the franchise with conservative risk, keep winning small business relationships that require real local work, and use digital to widen the funnel—without ever forgetting how close the bank once came to disappearing.

X. Porter's Five Forces & Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

In Hawaii, banking is a knife fight in a phone booth. You have the Big Two—First Hawaiian and Bank of Hawaii—anchoring the market with scale, brand recognition, and deep commercial relationships. Then you have Central Pacific and the credit unions battling in the middle. And hovering over everyone are the national banks, showing up just enough to scoop the most profitable customers without having to live with all the local complexity.

The Big Two also have the earnings power to keep investing—more branches, more marketing, better tech—year after year. Credit unions add another kind of pressure, especially on consumer deposits. Their tax-advantaged structure often lets them pay up for deposits or offer cheaper consumer loans, which forces banks to compete harder for everyday customers.

And then there are the mainland giants like Bank of America and Wells Fargo. They don’t need to dominate Hawaii to matter. They just need to win the affluent households and the biggest commercial clients—the ones that move the profit pool.

Threat of New Entrants: MODERATE-HIGH

Starting a new chartered bank is still hard. But “banking” isn’t confined to chartered banks anymore.

Digital-first players can serve Hawaii from anywhere, and they don’t need a single branch on Oahu to siphon off deposits. Chime, SoFi, and similar fintechs are perfectly happy to take a customer’s paycheck direct deposit and leave the rest of the relationship behind.

The one place Hawaii still protects incumbents is commercial lending—especially real estate and small business. Relationship underwriting matters here. A lender who doesn’t understand the local market, the local operators, and the local seasonality is flying blind. It’s hard to credibly underwrite a Maui development or get comfortable with a Kailua restaurant’s cash flows from a mainland credit box.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW-MODERATE

Banks “buy” two critical inputs: deposits and capability.

When rates rise and customers suddenly care again about what their cash earns, deposit costs jump—and everyone has to pay up to keep funding stable. At the same time, technology vendors have more leverage than they used to. Digital banking features aren’t optional anymore, and smaller banks can’t always dictate terms when a handful of providers control the best platforms.

Then there’s labor. Hawaii is expensive, talent is scarce, and experienced bankers are in demand. For a mid-sized bank, paying market rates for specialized skills—credit, compliance, tech, and relationship managers—can quietly become a structural disadvantage.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-HIGH

For consumers, switching has never been easier. You can open an account with a fintech in minutes, move your paycheck, and never talk to a human being if you don’t want to. Rate transparency also turns deposits into a shopping exercise, especially when money market yields are high and everyone is chasing basis points.

Business customers have more choices too: mainland banks, private credit, and direct lending funds all compete for commercial relationships.

But there’s still real stickiness at the high end of relationship banking. A business owner with a long history at CPB—someone whose banker understands their cycles, their collateral, and their business model—doesn’t move just to shave a little off the price of credit. In a small market, trust and continuity still carry weight.

Threat of Substitutes: HIGH

Payments and money movement, once a core bank monopoly, now have real alternatives. Fintech products can replace pieces of what checking accounts used to do. Buy-now-pay-later has chipped away at parts of consumer credit. Private credit can step in where banks once dominated commercial lending. Crypto and stablecoins remain a smaller factor today, but they continue to sit on the edge of the system as a potential substitute for storing and moving value.

Hamilton's Seven Powers Assessment:

-

Scale Economies: WEAK - CPB is simply smaller than the Big Two, and microscopic next to national banks. That makes it harder to spread fixed technology and compliance costs.

-

Network Effects: NONE - Traditional banking doesn’t improve just because more people use the same bank.

-

Counter-Positioning: MODERATE - The digital-plus-local model can work if it hits a sweet spot that neither pure fintechs nor megabanks fully deliver. But competitors can copy the idea, even if execution is harder.

-

Switching Costs: MODERATE - Commercial relationships create meaningful friction. Consumer relationships create some friction too—direct deposit, autopay, bill pay, and the annoyance factor—but not enough to prevent churn when a better offer appears.

-

Branding: MODERATE - CPB has real credibility in Hawaii, reinforced by its founding story and community presence. But it doesn’t have the same gravitational pull as the Big Two, and it can’t reliably charge premium pricing on brand alone.

-

Cornered Resource: WEAK - There’s no exclusive asset here. Good bankers are valuable, but they can be hired away, and talent isn’t owned.

-

Process Power: MODERATE - CPB’s “never again” risk discipline, its accumulated SBA lending know-how, and its improving digital execution are forms of institutional learning that don’t appear overnight.

Overall Assessment: CPB’s advantages are real but narrow. Its defensibility comes from relationship density in commercial banking and a hybrid model that blends local trust with modern digital delivery. That’s sturdier than a pure digital strategy, but it’s not the kind of moat scale players enjoy. Long-term success depends on staying disciplined, staying relevant, and continuing to focus on niches where local expertise actually matters.

XI. Bull Case vs. Bear Case

Bull Case:

Hawaii’s fundamentals still create steady demand for banking. The islands are supply-constrained by nature—there’s only so much buildable land—which tends to support property values and, by extension, mortgage and real estate lending. Tourism is cyclical, but it has proven remarkably durable over decades. And the military presence provides a stabilizing layer of government-backed economic activity that most states simply don’t have.

CPB’s digital investments also appear to be more than a buzzword. The PPP sprint showed the bank can execute at speed when it matters. Shaka Checking and the Banking-as-a-Service push suggest management is actively looking for growth levers that don’t require opening more branches in a market that’s already fully mapped. If those bets translate into more customers, deeper relationships, and better efficiency, earnings could compound faster than investors expect from a bank this size.

Then there’s the post-crisis advantage: scar tissue. CPB’s leadership and credit culture were forged in the 2008–2011 near-death experience. The bank doesn’t need another lesson about concentration risk. If Hawaii hits a soft patch, the bull case is that underwriting discipline keeps losses painful, but not existential—and the bank keeps doing what it does best: staying alive and taking share while others get reckless.

For income investors, the dividend matters. At roughly a 4% yield, with a history of steady increases, CPB offers a tangible return while you wait. In a sector that can re-rate violently, a reliable payout can soften the downside.

And finally, there’s optionality. Banking keeps consolidating. If that wave continues, a profitable Hawaii franchise with a modernizing digital platform and strong SBA lending capabilities could be attractive to a larger acquirer—and acquisitions often come with a premium.

Bear Case:

The structural squeeze on regional banks is getting tighter every year. Compliance costs don’t scale down just because the bank is smaller, which means mid-sized institutions like CPB carry a heavier burden. Meanwhile, “keeping up” in technology isn’t a one-time project. It’s an arms race—and megabanks can spread those costs across vastly larger customer bases.

Deposit competition is another pressure point. As rates rose, customers started caring about what their cash earns again, and banks had to pay up to keep deposits from walking out the door. If rates stay higher for longer, CPB may have to continue raising deposit rates, pushing its funding costs up and compressing net interest margins.

The growth runway is also inherently limited. Hawaii’s population is flat to declining, and the market is mature. CPB can win share, but it’s hard to outrun a pie that isn’t getting bigger.

At the same time, the competitive set is evolving. Hawaii consumers are practical and skeptical, and they’re increasingly comfortable shopping for financial services the way they shop for everything else: online, quickly, and with little loyalty. That dynamic makes it harder for any incumbent—especially one without the scale of the Big Two—to defend deposits and everyday consumer relationships against fintechs and national brands.

And then there’s climate risk. Sea level rise, stronger storms, and wildfire risk aren’t abstract concepts in Hawaii—they directly affect real estate collateral, insurance availability and cost, and a borrower’s ability to keep paying. Rising insurance premiums can function like a stealth rate hike on households and small businesses, tightening cash flow just when banks most need borrowers to stay resilient.

Key Metrics to Watch:

For investors tracking CPB, three indicators are especially telling:

-

Net Interest Margin (NIM): A core driver of bank profitability. If NIM expands, the bank is earning more on assets relative to what it pays for funding. If it compresses, it’s usually a sign deposit competition is biting.

-

Core Deposit Growth: Sticky, relationship-based deposits—checking, savings, and money market—are the best kind of funding. If CPB starts losing core deposits to fintechs or rate-driven competitors, funding gets more expensive and relationships get weaker.

-

Commercial Loan Mix and Credit Quality: CPB’s commercial business is where relationship banking earns its keep. Investors want to see healthy commercial growth without a rise in nonperforming loans—especially in the categories that hurt the most when cycles turn.

XII. Epilogue & Future Scenarios

Central Pacific Bank’s story lands on the same uncomfortable question hanging over regional banks everywhere: can a business built on geography and relationships hold up when banking becomes more digital, more national, and more scale-driven every year?

On the optimistic side, CPB’s near-death experience did what no consultant or strategic plan ever could. It hardwired discipline into the organization. After 2008–2011, the bank didn’t just “get more conservative.” It became culturally allergic to the kind of concentration and growth-at-all-costs thinking that kills banks. Layer on the digital push—small in absolute dollars compared to the megabanks, but meaningful for a Hawaii franchise—and you get a bank that’s more modern than many of its regional peers, with a home market that still rewards local trust.

On the pessimistic side, the math of banking has only gotten harsher. CPB is too small to get true scale economies in technology and compliance, too geographically constrained to diversify its risk the way a mainland regional can, and still tethered to an economy that’s heavily exposed to tourism cycles and external shocks. In that version of the future, the outcome is either consolidation—CPB gets absorbed—or slow erosion, as fintechs and megabanks nibble away at deposits and consumer relationships over time.

From here, the menu of strategic options is fairly clear:

Double down on commercial/small business: Lean even harder into the relationship-heavy work where local knowledge actually matters, and where digital-only competitors still struggle. Implicitly, that means accepting that a chunk of consumer banking will drift toward fintechs and national brands.

Accelerate BaaS partnerships: Use CPB’s charter and compliance infrastructure to support fintech products, letting partners handle customer acquisition while CPB generates fee income and expands its reach beyond the islands.

Pursue strategic merger: Look for a partner that adds scale without breaking the community banking model—potentially another Hawaii institution.

Remain independent and optimize: Treat the franchise like a durable, cash-generating business. Keep expenses tight, return capital to shareholders, and prioritize longevity over ambition—unless competitive pressure or leadership succession forces a bigger move.

The M&A question, in particular, isn’t theoretical. Results for the third quarter of 2024 were impacted by $3.1 million in pre-tax expenses tied to evaluating and assessing a strategic opportunity. The parties were no longer in discussions, but the company said it remained interested under the right terms and conditions.

In plain English: CPB has kicked the tires on something meaningful. We don’t know who was on the other side of the table. But we do know management is willing to explore consolidation if it strengthens the long-term position.

So what should investors take from all of this?

First, near-death can change a company. CPB’s post-crisis identity—more conservative, more process-driven, and later more digitally ambitious—was forged by the trauma of almost failing. The scars became the strategy.

Second, geographic moats don’t disappear overnight, but they do erode. Hawaii’s insularity still matters in relationship banking and commercial credit. But digital delivery makes physical presence less essential than it was 20 years ago, and it will be even less essential 20 years from now.

Third, leadership timing matters. John Dean stabilized the franchise when survival was on the line. Paul Yonamine brought a technology lens that pushed the bank into a more modern posture. Arnold Martines represents execution and continuity—keeping discipline intact while navigating a faster, more competitive environment.

And finally, community banks win when they act like community banks. CPB’s founding mission wasn’t a slogan; it was an operating principle. You can see it in the PPP sprint, in the bank’s SBA focus, and in how it responded on Maui. In a small market, that kind of credibility compounds in ways marketing budgets can’t buy.

Central Pacific is, at its core, the bank that almost died—and then learned how to evolve. Maybe necessity really is the mother of invention. Or maybe survival forces something even rarer: clarity about what matters, and what never can be allowed to happen again.

XIII. Recommended Resources

If you want to go deeper on Central Pacific—and on why Hawaii banking plays by its own rules—these are the best places to start:

-

CPF Annual Reports (2008–2011) - The crisis and recapitalization told in the company’s own words (SEC.gov EDGAR filings)

-

Hawaii Business Magazine archives - The local view of the boom, the bust, and the turnaround, including John Dean’s 2012 CEO of the Year coverage

-

Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Pacific Basin Notes - Research and market structure analysis on banking in Hawaii

-

FDIC Failed Bank List & case studies - The national failure wave CPB narrowly avoided—and how similar banks didn’t make it

-

CPF Investor Presentations (2020–present) - How management describes the digital strategy, the business mix, and performance (ir.cpb.bank)

-

S&P Global Market Intelligence reports on Hawaii banking - Competitive dynamics, market share, and industry context

-

Maui wildfire response documentation - A real-world look at what “community banking” means during an on-island disaster

-

442nd Regimental Combat Team resources - Background on the founders’ experiences and the social context that shaped CPB’s mission

-

Silicon Valley Bank case studies - John Dean’s earlier turnaround work and the operating playbook he brought to Central Pacific

-

Hawaii tourism industry reports - The economic engine behind the islands—and a key variable in CPB’s lending environment

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music