Columbia Banking System: The Story of the Pacific Northwest's Quiet Giant

I. Introduction: A Bank That Refuses to Die

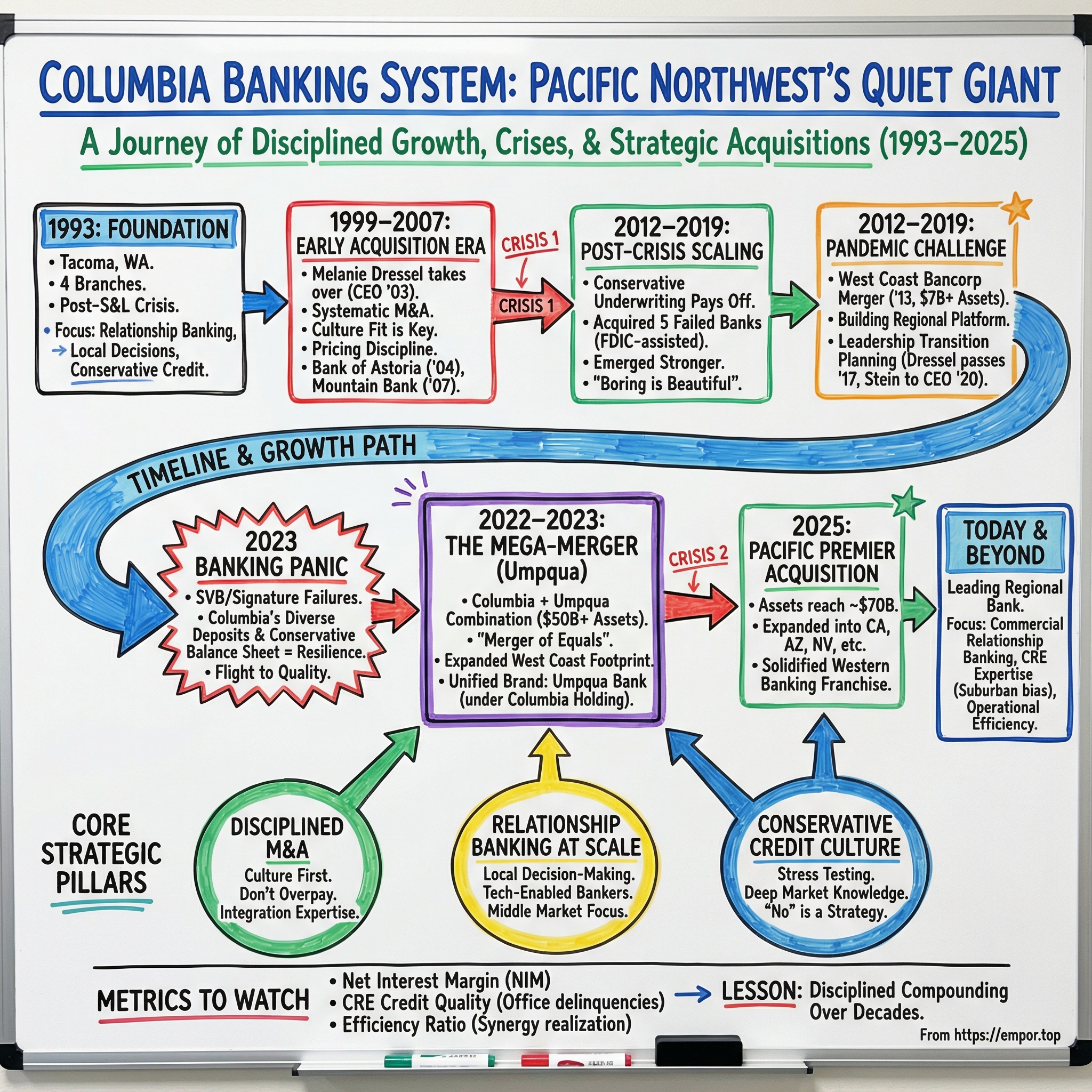

Picture this: late February 2023. The regional banking world is calm on the surface, but the ground is already shifting. Within weeks, Silicon Valley Bank will collapse in spectacular fashion, setting off the biggest wave of bank failures since 2008. Signature will follow. First Republic will wobble, then vanish. Headlines will blare “banking crisis.” Depositors will start asking uncomfortable questions. Regional bank stocks will get crushed.

And in Tacoma, Washington, Columbia Banking System is doing something that, on paper, looks almost reckless: it has just closed the most ambitious merger the Pacific Northwest has seen in years, combining with Umpqua Holdings to create one of the largest banks headquartered in the West.

The timing couldn’t have been more dramatic—or more revealing.

With more than $50 billion in assets at close, the combined institution set out to marry two ideas that rarely coexist in banking: the resources and sophistication you expect from a much larger bank, and the promise of relationship-driven service that’s supposed to die as you scale. And it didn’t stop there. Following its September 2025 acquisition of Pacific Premier Bancorp, Columbia’s assets rose to roughly $70 billion—an outcome that would have sounded absurd back when it opened its first branch in a modest Tacoma office three decades earlier.

This is the story of how a small-town Washington bank became one of the most acquisitive—and resilient—regional banks in America. It’s about disciplined underwriting while competitors chased the hot hand. It’s about walking away from deals when the numbers didn’t work. It’s about building an acquisition machine that could absorb failed banks in crisis, buy healthy competitors in calm markets, and eventually merge with a longtime rival to create something bigger than either could become alone.

Columbia isn’t interesting just because it got bigger. Plenty of banks got bigger. Columbia is interesting because of how it got bigger: through cycles that wiped out peers, through crises that should have broken it, and through decades of quiet, almost stubborn execution that turned a four-branch startup into a regional powerhouse.

For long-term investors, it’s a clean case study in the economics of regional banking: why scale matters, why geography can be both moat and trap, how consolidation creates opportunity, and why commercial real estate is always a gift with strings attached. Columbia has lived through every major banking shock of the past thirty years and, somehow, walked out stronger each time.

Whether it can keep doing that is the question we’re here to answer.

II. The Pacific Northwest Banking Context & Early Origins

To understand Columbia Banking System, you first have to understand the place that produced it.

The Pacific Northwest runs on contrasts. Yes, there’s the weather, the ever-present gray that seems to slow everything down by half a beat. But the real difference is economic. This is Boeing country, Microsoft country, Amazon country—alongside timber, fishing, and agriculture. It’s Seattle and Portland’s tech corridors, and it’s also small towns east of the Cascades where a handshake still counts and everyone knows who owns what.

That mix creates a very specific kind of banking problem. If you’re too small, you can’t support the more sophisticated needs of growing businesses—things like treasury management and commercial credit that has to move fast. If you’re too big, you feel distant. Decisions get made in another state by people who don’t know the market, and the relationships that keep deposits and loans “sticky” start to fray. National mega-banks never fully fit the region’s temperament. The banks that did were the ones that could do both: feel local while operating with real capability.

Columbia’s roots go back to 1988, when First Federal Corporation was established, later named Columbia Savings Bank. In 1990, an investor group acquired a controlling interest in the company, along with another corporation—Columbia National Bankshares, Inc.—and its sole banking subsidiary, Columbia National Bank.

Then came the pivot. In 1993, the company reorganized to pursue commercial banking opportunities in its core market. The opening wasn’t theoretical. It was created by consolidation—local institutions being acquired by out-of-state holding companies. Customers got “dislocated”: the loan officer they trusted was gone, credit decisions were centralized, and longtime business owners suddenly felt like a number in someone else’s portfolio.

The timing mattered. The early 1990s were still the hangover from the Savings & Loan crisis, which had wiped out thousands of institutions nationwide. In the Northwest, that mess collided with anxiety in legacy industries—timber was in decline, Boeing was laying off workers, and the region’s economic future didn’t yet look like the inevitable tech boom we now take for granted. In that environment, a bank that promised steady, local judgment wasn’t quaint. It was a competitive weapon.

Columbia Bank launched in 1993 under Columbia Banking System, Inc., opening its first Tacoma branch on August 17. Bill Philip was elected the first chairman and president.

Philip brought instant credibility. He wasn’t an outsider with a slide deck—he had been the CEO of Puget Sound National Bank before it was sold to Ohio-based Key Bank. His mandate was clear: expand in Pierce County by building a bank that felt like it belonged there. He went after experienced bankers who knew the market, knew the businesses, and could rebuild the kind of trust that consolidation had disrupted.

The founding philosophy was simple, and in the era’s growth-at-any-cost mindset, quietly contrarian: conservative underwriting, relationship banking, local decision-making. Don’t chase hot markets. Don’t stretch for yield. Know your customers. Understand their businesses. Make loans you’ll still like years from now.

By the end of 2007, Columbia had grown from four branches to 55. On the surface, that looks like straightforward expansion. But the more important point is how they were expanding. Columbia wasn’t just planting flags. It was learning how to scale without losing control—building the early version of an acquisition-and-integration playbook that would define the company for decades.

In 1998, Columbia crossed $1 billion in assets—one of those banking milestones that changes how a company is perceived. You have enough size to invest in infrastructure and compete for larger commercial relationships. You also attract a new kind of pressure: grow faster, swing bigger, take more risk.

Columbia’s response was to lean harder into fundamentals—credit quality, operational discipline, and culture. Even then, the goal wasn’t to be flashy. It was to build something that would still be standing when the cycle turned.

III. The Acquisition Machine Awakens (1990s–2008)

In 1999, Melanie Dressel took over as president and CEO of Columbia Bank. It was a leadership change that didn’t just shift the org chart—it hardened Columbia’s identity.

Dressel wasn’t a new hire brought in to “professionalize” the place. She was there at the beginning. Part of the founding team in 1993, she helped build Columbia’s particular style of banking: deeply local, relationship-first, and quietly allergic to anything that smelled like a shortcut.

Her personal story fit the region, too. Born and raised in Colville, in Stevens County, she grew up around a small family business—her parents owned a jewelry and gifts store. She got her start in banking as a commercial real estate loan clerk at the Tacoma branch of what was then Bank of California, and she climbed from there in an era when women rarely made it into the executive ranks. Eventually, she rose into leadership at Puget Sound National Bank.

When Puget was sold to Ohio-based Key Bank in 1993, Dressel didn’t stick around. She planned to leave banking entirely and start a financial consulting business. But Bill Philip had other plans.

“I harassed her to join us, and she did,” Philip later recalled. “She had the experience. She knew pretty much all the private-banking customers in Pierce County, so she was a natural. We all had fun getting the bank started, and she enjoyed working with her former clients and bringing them over to Columbia.”

As Dressel’s tenure deepened—she served as president starting in 2000 and as CEO beginning in February 2003—Columbia’s approach to acquisitions matured. It stopped being opportunistic and became systematic, with a few rules that rarely budged.

First: culture fit was treated as a hard requirement, not a soft preference. Plenty of bank buyers look at targets as a pile of deposits, a loan book, and a branch map. Columbia looked at them as living ecosystems of bankers and customers. If the people and the way they worked didn’t align, Columbia would pass—even when the spreadsheet said “go.”

Second: they didn’t overpay. Bank M&A has a long history of executives chasing size, calling it strategy, and handing shareholders the bill. Dressel kept pricing discipline. If a seller wanted more than Columbia believed the franchise was worth, Columbia walked. That meant losing deals in hot markets, but it also meant not getting trapped by bad math.

Third: integration wasn’t treated like cleanup—it was the product. The real risk in bank mergers isn’t the press release. It’s what happens afterward: customers get spooked, employees leave, systems break, and the combined institution bleeds quietly for quarters. Columbia invested in the operational muscle to convert systems and retain relationships smoothly, over and over again.

The results showed up in the map.

In 2004, Columbia Bank acquired Bank of Astoria, founded in 1968, for a reported $45.8 million. It was Columbia’s first real step into Oregon—an expansion that made strategic sense, not just geographic sense. Oregon was the next logical extension of a Pacific Northwest franchise.

Then, in the spring of 2007, Columbia announced it would merge with Enumclaw-based Mountain Bank Holding Co., the parent of Mt. Rainier National Bank. The acquisition closed on July 23, 2007.

But the thing that truly separated Columbia heading into the late 2000s wasn’t just the deals it did. It was the loans it refused to do.

A decade ago, Dressel was still defending the same stance to analysts and investors: she wasn’t going to chase riskier credits just to goose growth. That discipline showed up in the details—lower loan-to-value ratios, conservative appraisals, and stress-testing instincts before “stress testing” became standard industry language. Just as important, it showed up in the relational texture of the bank: bankers who knew the difference between a borrower with a real business and a borrower riding the cycle.

That conservatism could be maddening if you were grading the bank quarter to quarter. But it was exactly the kind of stubbornness you wanted when the world flipped in 2008.

IV. Surviving the Great Financial Crisis (2008–2011)

When the financial crisis hit in 2007 and accelerated into 2008, it punished the exact kind of lending that powered a lot of regional-bank growth in the years before it: commercial real estate, construction, and anything tied to a housing market that suddenly stopped going up.

The Pacific Northwest had plenty of both. There had been a construction boom. Home prices had climbed. And when the music stopped, banks across Washington, Oregon, and Idaho didn’t just take losses—they failed, in waves.

Columbia didn’t.

It did something rarer, and far more revealing: it got stronger.

By the time the crisis arrived, Melanie Dressel had already been running the bank for years. She took over as CEO in 2003, when Columbia had about $2 billion in assets. Over the next dozen or so years, she led Columbia through 10 acquisitions, including multiple failed-bank deals after the crash.

Those FDIC-assisted transactions were the kind of opportunities that only show up when things are broken. When regulators shut a bank, they typically looked for a healthy buyer to assume deposits and take on performing assets—often with loss-sharing arrangements that helped protect the acquirer from further credit deterioration. For a bank with capital, a conservative credit culture, and a proven ability to integrate, it was the closest thing finance has to buying good franchises in a fire sale.

Columbia leaned in. In 2010, it bought Columbia River Bank in Oregon and American Marine Bank on Bainbridge Island. In 2009, it acquired three Washington banks: Summit Bank in Burlington, First Heritage Bank in Snohomish, and Bank of Whitman in Colfax.

The strategic takeaway is simple: while competitors were nursing wounds, selling assets, raising emergency capital, and sometimes being seized outright, Columbia was picking up market share, talent, and customer relationships at favorable terms. The crisis that erased weaker institutions turned into an accelerant for Columbia.

And it wasn’t because Dressel suddenly got aggressive. It was the opposite. Columbia’s long-standing refusal to chase risky growth meant it entered the downturn with a cleaner loan book and the credibility to act when others couldn’t. In 2011, Dressel was named one of American Banker’s three Community Bankers of the Year—a recognition that, in context, was really a verdict on strategy.

Her performance during the crisis also stuck with peers who would matter later. Ray Davis, executive chairman at Umpqua Holdings in Portland, put it plainly: “When I think of Melanie, I think of how strong of a leader she was. She led her people while motivating them to reach the goals she set for the company.”

The crisis left Columbia with something else, too—something you can’t put on a balance sheet but that shapes every decision afterward: a crisis-tested culture. The people who lived through 2008 to 2011 didn’t need a training module to understand why credit discipline matters. They’d watched what happened to banks that stretched.

For investors, this era is where the Columbia model becomes undeniable. Conservative underwriting gave it a cleaner starting point. Strong capital gave it options. And the acquisition playbook turned chaos into compounding. It wasn’t luck. It was the delayed payout of years of quiet, stubborn execution.

V. The Post-Crisis Growth Era (2012–2019)

Columbia came out of the financial crisis with something most banks couldn’t buy: credibility. It had proven it could underwrite through a cycle, keep its footing when peers fell over, and then integrate acquisitions without blowing up the franchise. Now the mission shifted from survival and opportunism to something more ambitious: build a truly regional platform—big enough to matter, still local enough to feel like a community bank.

The deal that made that real arrived in September 2012. Columbia Banking System and West Coast Bancorp announced an agreement to combine in a transaction valued at roughly $506 million. It was a statement: this wasn’t an FDIC clean-up anymore. This was a healthy-on-healthy merger intended to create a Pacific Northwest contender.

The combined company was expected to have about $7.2 billion in assets and more than 150 branches across Washington and Oregon, and to rank number 1 in deposit market share among commercial community banks in the two-state footprint. Just as important, the market understood what it represented: the largest Pacific Northwest bank deal without government assistance since the 2008 crisis.

On April 1, 2013, Columbia announced it had completed the acquisition of West Coast Bancorp, the parent of West Coast Bank. Columbia’s total assets now exceeded $7 billion, with 157 branches spanning 38 counties in Washington and Oregon.

And the way Columbia talked about the deal mattered as much as the deal itself. West Coast’s CEO called it “a rare fit of two high quality organizations with similar business models, cultures and values.” That wasn’t PR fluff. It was Columbia’s core filter. In banking, you can buy branches and deposits, but you can’t force trust. Columbia wanted franchises where the customer relationships would survive the conversion.

You could see that in personnel decisions, too. West Coast CEO Robert Sznewajs retired, but West Coast’s chief credit officer, Hadley Robbins, stayed on and became group manager for Oregon in the combined organization. Columbia wasn’t in the habit of buying banks and immediately stripping them for parts. Keeping key people—especially credit and relationship leaders—was how you kept the thing you actually paid for.

There were, of course, the practical merger moves. Columbia expected to close eight to 10 overlapping branches and realize about $20.9 million in savings. Dressel was confident they could execute, pointing to recent experience integrating the five failed banks Columbia had acquired with federal assistance over the prior two years. This was the playbook now: merge systems, consolidate where it made sense, and get the synergies without breaking customer relationships.

This era also quietly set up Columbia’s next chapter: leadership succession. In August 2012, Dressel announced that Clint E. Stein had been promoted to Executive Vice President and Chief Financial Officer. Stein had joined Columbia in 2005 as Senior Vice President and Chief Accounting Officer, and Dressel emphasized how central he had been to the bank’s growth, including building the accounting processes that supported the FDIC-assisted acquisitions.

That planning turned out to matter more than anyone wanted.

In February 2017, Columbia Banking System announced that Melanie J. Dressel had died suddenly. Chairman William Weyerhaeuser said, “It is with great sadness that I announce the passing of my friend and colleague Melanie Dressel. Melanie had served as our Chief Executive Officer since 2003, and was also a member of our Board of Directors. Under her tireless leadership, Columbia grew to be widely recognized as one of the best regional community banks in the country, and has been continually acknowledged as one of the best workplaces in the Northwest. Melanie has made an indelible mark on who we are today.”

Dressel had taken a Tacoma bank and turned it into a regional force that would go on to exceed $10 billion in assets. But her bigger legacy was intangible: the culture, the discipline, and the bench of leaders who could carry it forward.

After Dressel’s death, Hadley Robbins—by then a key executive shaped by the West Coast integration—stepped in as CEO, with Stein becoming chief operating officer. It was the culmination of a succession plan that had been put in motion years earlier, including Stein’s deliberate progression from CFO to COO in 2017. When Robbins later retired, Stein became CEO on Jan. 1, 2020.

Stein’s background was different from Dressel’s—more finance and operations than commercial lending—but he’d spent years inside Columbia learning what, exactly, made the machine run. When he was appointed CEO, he said, “I’m honored to be chosen by the Board as Columbia’s next CEO. I had the privilege of working closely with Melanie Dressel for over a decade and with Hadley for the past seven years. I look forward to building on their legacy and the tremendous foundation they established.”

Stein attended the University of Idaho and previously served as Senior Vice President and Chief Financial Officer at Albina Community Bank in Portland. He earned a Bachelor’s degree in Accounting and Business Administration from the University of Idaho and completed post-graduate programs including the Graduate School of Bank Financial Management and the Graduate School of Banking at the University of Wisconsin.

Years later, after the merger with Umpqua, Stein would be leading one of the largest publicly traded banks headquartered in the West, with about 5,600 employees. But the real throughline to this period is simpler: Columbia didn’t just buy scale. It built continuity—of people, of process, and of a culture designed to outlast any one cycle, or any one leader.

VI. The Pandemic Plot Twist (2020–2021)

Clint Stein became CEO on January 1, 2020. Ten weeks later, the world shut down.

Overnight, COVID threw a wrench into the kind of banking Columbia had spent decades perfecting. Relationship banking is built on face time—walking job sites, sitting across a desk from an owner-operator, reading the room as much as the financials. Now branches went quiet. Office buildings emptied out. And the small businesses that made up Columbia’s core customer base were suddenly fighting for survival.

But the pandemic also made something else unmistakable: regional banks still matter, because in a real emergency, trust and proximity beat scale.

When the federal government rolled out the Paycheck Protection Program, the whole thing hinged on a simple question: who could get money to small businesses fast? The largest banks, optimized for standardized products and centralized workflows, struggled to serve businesses that weren’t already neatly inside their systems. Community and regional banks had the opposite advantage. They knew the owners. They knew the payroll cycles. They knew which businesses were real, and which were just paperwork.

Columbia processed thousands of PPP loans, pushing capital to businesses that might not have made it otherwise. It wasn’t a feel-good sideline—it was the franchise doing what it was built to do, at the exact moment customers needed it most. And those kinds of moments, in banking, tend to create loyalty that lasts a lot longer than the crisis itself.

Then came the twist nobody plans for: the bank had too much money.

Between stimulus checks, reduced spending, and general uncertainty, deposits poured into the system. Columbia, like many banks, found itself awash in liquidity at the worst possible time to have it—when interest rates were pinned near zero and “putting money to work” without taking bad risk was harder than it had been in years.

The result was predictable. With rates crushed, the classic banking engine—gather deposits cheaply and lend at a healthy spread—started sputtering. Net interest margins tightened across the industry, and disciplined banks like Columbia weren’t about to fix that problem by suddenly reaching for yield.

So the pandemic didn’t just test Columbia operationally. It forced a strategic reckoning. If organic growth was going to be slow and spreads were going to be thin, there was really only one lever left that could change the trajectory.

Get bigger.

VII. The Mega-Merger: Umpqua Acquisition (2022–2023)

In October 2021, Columbia announced the kind of deal that doesn’t just change a balance sheet. It redraws the map.

Columbia Banking System and Umpqua Holdings Corporation said they would combine in an all-stock transaction. The mechanics were straightforward: Umpqua shareholders would receive 0.5958 shares of Columbia for each Umpqua share. When the dust settled, Umpqua shareholders would own about 62% of the combined company and Columbia shareholders about 38%. The prize was scale: a West Coast franchise with more than $50 billion in assets.

The press release called it a merger of equals. And culturally, that was the point. But legally, Columbia was the acquirer—an important nuance in banking, where the fine print governs everything from taxes to regulatory approvals to who ultimately controls the holding company.

Leadership was designed to look like a partnership, too. The combined company would pull from both teams. Cort O’Haver, Umpqua’s president and CEO, would become executive chairman. Clint Stein, Columbia’s president and CEO, would run the combined bank as CEO.

To understand why this made sense—and why it was hard—you have to understand Umpqua.

Umpqua began life in 1953 as South Umpqua State Bank in Canyonville, Oregon. It had six employees and a very specific purpose: people in the timber business wanted a place where workers could cash payroll checks. The bank opened with $50,000 in capital, plus $25,000 in surplus and reserves.

Decades later, in 1994, Ray Davis took over what was then a small local bank with about 40 employees. By 1999, he was CEO and president of Umpqua Holdings. And he didn’t just grow the bank—he reinvented what it was supposed to feel like.

Davis became famous for insisting employees answer the phone with “World’s Greatest Bank,” a line that initially made competitors roll their eyes. He sent tellers to the Ritz-Carlton to learn customer service. Umpqua began calling branches “stores,” building spaces that looked more like retail lounges than banks—often with coffee bars, community gathering areas, and design that earned awards and national attention. A name change and more than 15 acquisitions later, Umpqua had become a Pacific Northwest standout.

The numbers told the same story. When Davis took the helm in 1994, the bank had about $140 million in assets and five branches in southwest Oregon, headquartered in Roseburg. Years later, Umpqua had grown into the region’s largest bank, with more than $24 billion in assets and roughly 320 branches.

Just as important: Umpqua had its own crisis scar tissue. During the financial crisis it had problems, but it moved early—selling underwater real estate assets quickly, rather than hoping the market would bail it out. That posture helped it raise more than $530 million in capital without relying on private equity money, and it emerged as an acquirer rather than a casualty. It bought four failed banks in 2009 and 2010, added the equipment-financing firm Financial Pacific Leasing in 2013, and then, in 2014, doubled down with its blockbuster acquisition of Sterling Financial in Spokane.

So when Columbia and Umpqua came together, it wasn’t a simple “strong buys weak” story. It was two survivors, both built through acquisition, both committed to relationship banking—but with very different personalities. Columbia had cultivated a steady, conservative, quietly methodical identity. Umpqua had built a brand that was louder, more retail-forward, and unusually well-known for a regional bank.

Strategically, the fit was clear. Columbia was stronger in Washington. Umpqua was dominant in Oregon. Put them together and you had a West Coast footprint with meaningful scale—big enough to invest in technology and compete harder for commercial relationships, while still claiming local decision-making.

The deal pitch leaned heavily on financial upside. The companies projected meaningful earnings accretion for both sides in 2023, assuming cost savings were fully phased in. They also projected about $1.1 billion in value creation from cost synergies, along with improved profitability and operating metrics under that same assumption.

But banking deals don’t close when you want them to. They close when regulators say they can.

The approval process stretched. The Federal Reserve approved the combination in October 2022. The next month, Columbia outlined plans to divest 10 branches to address Justice Department concerns about competition.

Finally, on March 1, 2023, Columbia Banking System and Umpqua Holdings announced they had closed the merger—combining two of the Northwest’s best-known banking franchises into one of the largest banks headquartered in the West.

The new institution positioned itself as a top-30 U.S. bank, with the product breadth and operational muscle of a larger regional player, but with the same promise both companies had long sold: local decision-making and a personalized approach to customers. The combined company’s board reflected the “merger of equals” spirit too: 14 directors, split evenly—seven from Columbia and seven from Umpqua.

Then came the branding decision, and it was telling. After closing, the holding company would keep the Columbia Banking System, Inc. name and remain headquartered in Tacoma. But the bank would operate as Umpqua Bank, headquartered in Lake Oswego. It was a pragmatic acknowledgement of what Umpqua had built: stronger consumer recognition—especially in Oregon and California, where it had invested heavily in marketing—and a retail brand that carried real weight in the market.

VIII. The 2023 Banking Crisis & Regional Bank Reckoning

The merger closed on February 28, 2023. Ten days later, Silicon Valley Bank failed.

For nearly four decades, SVB had been the banker to the startup economy—deep in the plumbing of Silicon Valley. It held deposits for venture-backed companies, served founders and funds, and became the largest bank by deposits in the Valley. Then, in early March, it went from “fine” to finished in a blink. Over two days, depositors rushed for the exits, and on March 10 federal regulators shut the bank down.

SVB’s collapse became the second-largest bank failure in U.S. history, behind Washington Mutual in 2008.

What spooked the system wasn’t just the failure. It was the fear that uninsured depositors might take losses. And once that idea is in the air, it doesn’t stay neatly contained. Uninsured depositors at other regional banks started asking the same question: “What about us?” Withdrawals spread. Signature Bank in New York—an institution with more than $100 billion in assets—came under intense pressure. By Sunday, March 12, just two days after SVB’s failure, New York regulators closed Signature as well.

This was, in other words, the worst possible moment for Columbia. It had just completed the largest merger in its history. Integration work was underway. Systems were being combined. Teams were being stitched together. And now the entire regional banking sector was being repriced in real time—by depositors, by investors, and by regulators.

Regional bank stocks fell hard across the board as the market began gaming out who might be next.

But Columbia’s situation was not SVB’s.

“With SVB, we saw the attempted withdrawal of over 60 percent of deposits in one day,” Stanford professor Darrell Duffie noted. “It is clear now, if it wasn’t before, that large uninsured depositors will move their funds out of a bank that’s in trouble very quickly, particularly financially savvy large depositors who are going to be attuned to these risks.”

SVB’s deposit base was unusually concentrated—tech companies, venture firms, and a tight network that moved together once confidence cracked. Columbia’s deposit base looked nothing like that. It was spread across industries, geographies, and customer types. There wasn’t a single community of depositors positioned to stampede in the same synchronized way.

The other difference was on the asset side. SVB had loaded up on long-duration securities and took on major interest rate risk. When rates surged, unrealized losses ballooned, and the balance sheet suddenly looked fragile at exactly the wrong time. Columbia had managed its securities portfolio more conservatively, and the Umpqua combination had been structured with interest rate and liquidity considerations in mind.

After the shock of March 2023, regional banks broadly stabilized. The acute panic faded, and aggregate indicators across the group improved. The larger takeaway from the first half of 2023 was the one that surprised a lot of Wall Street: this didn’t turn into an economic crisis. It didn’t cascade into a broad shutdown of credit, and it didn’t seem to meaningfully dent growth or the market’s appetite for risk.

For Columbia, the episode ended up reinforcing the logic behind several of its big strategic bets. Diversification in deposits mattered. Conservative balance-sheet management mattered. And scale—especially scale achieved by combining two Pacific Northwest franchises—could actually make the institution more resilient, not more brittle.

The policy response mattered too. The 2023 failures put regional banks under a hotter regulatory spotlight, with more scrutiny on liquidity, interest rate risk, and capital. That meant higher compliance costs across the industry—and once again, it quietly favored the players with enough scale to absorb those costs without breaking stride.

IX. Columbia Today: Business Model Deep Dive

Today, Columbia Banking System is still headquartered in Tacoma, Washington. But the operating engine underneath it is Umpqua Bank, based in Lake Oswego, Oregon—an award-winning Western U.S. regional bank and the largest bank headquartered in the Northwest. Across its footprint, it operates in Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, and Washington.

Scale has continued to ratchet up. Following the Pacific Premier acquisition, Columbia’s assets rose to approximately $70 billion, with roughly $50 billion in loans and $56 billion in deposits. In total, the organization runs more than 350 locations across eight Western states.

And then came a subtle but important signal of where management wanted to take the combined franchise. Effective September 1, 2025, Columbia Bank began serving customers under its unified name and brand, completing the transition announced earlier in the year away from the Umpqua Bank name.

Underneath the signage, the modern Columbia playbook is still recognizable. It’s the same core strategy that got them through 2008, through the pandemic, and through the 2023 panic—just executed at a much bigger altitude.

The modern Columbia playbook centers on several core elements:

Commercial Banking Focus: The bank targets middle-market companies and owner-operated businesses—enterprises too large for community bank services but too small to interest the mega-banks. These customers need sophisticated treasury management, credit facilities, and specialized lending products, but they also value personal relationships and local decision-making. Columbia’s size lets it deliver the product set, while its culture is designed to protect the relationship model.

Commercial Real Estate Expertise: CRE lending has been a Columbia competency for decades. At Columbia, a majority of office loans are in suburban areas. Real estate prices in the suburbs and smaller cities are generally expected to be less volatile than in urban areas. “We have very limited exposure to core downtown metro markets,” Frank Namdar, Columbia’s chief credit officer, has noted.

At least 36% of the firm’s office loans are in California. Another 28% are in Oregon, and 27% are in Washington state.

That suburban tilt has offered some insulation from the most visible office-market stress, which has been concentrated in big downtown cores. But it doesn’t make the risk disappear. Office loans totaled more than 70% of Tier 1 capital at the end of the first quarter of 2024, according to S&P—a concentration level that’s worth watching closely.

Relationship Banking at Scale: The challenge for any growing bank is maintaining personal relationships as the institution gets larger. Columbia addresses this through local decision-making authority, experienced relationship managers, and technology that’s meant to support bankers—not replace them.

“I call it small-town accountability because there’s no anonymity in a small town — and so that’s kind of helped in terms of how we think about our commitment to all of our stakeholders,” Clint Stein has observed.

Geographic Concentration: Columbia’s Pacific Northwest roots are both strength and vulnerability. Strength, because deep local knowledge creates real edge in underwriting and relationship banking. Vulnerability, because if the region takes a hit—a Boeing contraction, a tech bust, or a major natural disaster—the franchise feels it more directly than a nationally diversified bank would.

On recent performance, the bank’s results show what a larger, more integrated Columbia looks like in practice. Net interest income was $437 million for the fourth quarter of 2024, up $7 million from the prior quarter. The increase reflected lower funding costs, partially offset by lower interest income following reductions in the federal funds rate. Net interest margin was 3.64% for the fourth quarter, up 8 basis points from the third quarter.

Columbia reported net income of $143 million and operating net income of $150 million for Q4 2024, with earnings per share of $0.68 and operating earnings per share of $0.71.

On the cost side, management has emphasized that the integration and restructuring work is showing up in the numbers. The company cited a 25% reduction in recurring expenses over the past 18 months, alongside solid core deposit growth even as deposit costs declined. Columbia also reduced core expenses by 8% from the prior year.

For the full year 2024, Columbia Banking System reported revenue of $1.82 billion, up 2.22% from $1.78 billion the year before. Earnings were $533.68 million, up 53.04%.

X. Industry Dynamics & Competitive Landscape

Regional banking in 2025 is getting squeezed from every direction.

From above, the mega-banks—JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, Wells Fargo—show up with advantages that are hard to overstate. They can outspend everyone on technology, marketing, and product. They can treat certain services as loss leaders just to win deposits, confident that scale will pay them back over time. Their apps are best-in-class. Their footprints are national. Their brands open doors before a banker ever walks in.

From below, fintechs and neobanks attack the opposite way. They don’t have decades of branches, mainframes, and middle layers to pay for. They can pick a single wedge—payments, lending, deposits—and build a clean, specialized experience around it. For customers who don’t want a relationship, just a slick interface, that’s a real substitute.

And from the side, credit unions keep expanding with a structural edge: tax advantages that let them price more aggressively than for-profit banks on many of the same products.

So what’s left for a regional bank?

A defensible niche—something big banks are too scaled and centralized to do well, and fintechs can’t do because it still requires judgment, trust, and local knowledge. For Columbia, that niche is commercial relationship banking: serving middle-market businesses that need more than a self-serve portal but aren’t big enough to be prioritized by a mega-bank’s corporate machine.

The macro backdrop doesn’t make that job easier. As the largest banks keep getting larger—and increasingly look “too big to fail”—regional banks face persistent earnings pressure. Depositors can earn close to 5 percent in money market funds and T-bills, which forces banks to pay up for funding. And higher funding costs don’t just hit bank margins; they ripple outward into the commercial real estate market, where regional banks play an outsized role in financing. When bank funding gets more expensive, real estate capital gets tighter.

That’s why consolidation is no longer a theory in regional banking. It’s a survival strategy. Since 2008, compliance costs have climbed, technology expectations have risen, and efficiency ratios tend to reward whoever has the most scale to spread fixed costs.

In other words: get bigger, or get acquired.

Columbia has made its choice. The Pacific Premier acquisition in 2025 was the continuation of the same playbook that produced the Umpqua deal: build scale in the Western U.S. and use it to compete harder in the markets that matter most. After the combination, the company had roughly $70 billion in assets and positioned itself as a leading franchise across major Western banking markets. As Clint Stein put it, “This combination truly establishes the leading banking franchise in the Western region. It is a natural and strategic fit that strengthens our competitive position in Southern California, enhances our service offerings, and elevates our performance.”

Back home in the Pacific Northwest, competition is still intense. Banner Bank, HomeStreet, and a long tail of community banks continue to fight for the same deposits and commercial relationships. Columbia’s scale advantage has widened dramatically after Umpqua and Pacific Premier—but in banking, scale only buys you the right to win. The winners still have to execute: keep the culture intact, retain customers through conversions, and make sure the big-bank capabilities don’t come at the expense of the local judgment that made the franchise valuable in the first place.

XI. Strategic Analysis: Porter's Five Forces

Competitive Rivalry: Competition is constant in Columbia’s markets, and it comes from both directions at once. In big metro areas, the mega-banks bring brand power, product breadth, and the ability to win business with pricing that regionals can’t always match. In smaller markets, community banks compete on familiarity and local ties. Columbia sits in the middle: large enough to out-resource many local competitors, but still able to sell a relationship model that feels meaningfully different from a national bank. The one area that’s gotten noticeably tougher since 2023 is deposits, where customers have become far more rate-sensitive and willing to move for yield.

Threat of New Entrants: Traditional new-bank entry is constrained by high barriers. Building a bank today means meeting steep capital requirements, absorbing heavy compliance costs, and somehow assembling a stable deposit base from scratch—all while convincing experienced bankers to join an unproven platform. Since the financial crisis, de novo bank formation has been rare for exactly these reasons. The more realistic “new entrant” threat comes from fintech, but it tends to concentrate on consumer and small business use cases rather than the middle-market commercial relationships Columbia is built around.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: In banking, your suppliers are the people who give you funding—depositors—and in the current environment, they have real leverage. When money market funds and short-term Treasuries pay attractive yields, deposits become less “sticky,” and banks have to compete harder to keep them. Vendors matter too: the technology stack is increasingly essential, and major providers have pricing power, even if switching costs often keep banks locked into long relationships. And then there’s the supplier that doesn’t show up on a balance sheet: talent. The competition for strong commercial bankers has intensified as consolidation narrows the field and concentrates opportunity.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: On the lending side, middle-market clients can shop. They can compare rates, terms, and even relationship teams across banks. But switching isn’t frictionless. Moving operating accounts, treasury management, payroll, and long-standing credit facilities creates real costs and risk for a business, which gives relationship banks like Columbia more staying power than a pure rate-driven lender. Consumer customers have fewer barriers to switching, but inertia—and the hassle factor of changing banks—still helps retain balances.

Threat of Substitutes: The substitutes are real, and they’re multiplying. Private credit funds increasingly compete for commercial loans. Direct lending platforms chip away at parts of the small business market. And for deposits, money market funds are a straightforward alternative when yields are high. Traditional banking is being disintermediated in pockets across the system. The important nuance for Columbia is that the most resilient part of the model tends to be the hardest to replace: middle-market relationship banking, where judgment, trust, and local knowledge still matter.

XII. Strategic Analysis: Hamilton Helmer's Seven Powers

Scale Economies: YES—and becoming more important as banking gets more compliance-heavy and more tech-driven. In plain terms: the bigger you are, the cheaper it is per dollar of assets to run the machine. Technology spend, regulatory overhead, and back-office infrastructure don’t scale linearly. The Umpqua and Pacific Premier mergers meaningfully increased Columbia’s ability to spread those fixed costs. Even the branch network works this way: as deposits and relationships deepen, each location can produce more value without the cost base rising nearly as fast.

Network Economies: LIMITED. This isn’t social media, where every new user makes the product more valuable for everyone else. Banking doesn’t naturally compound that way. There are small, real second-order effects in a regional economy—being deeply embedded in Pacific Northwest commerce can create referral loops and relationship connectivity—but they’re modest, and they don’t behave like true network effects.

Counter-Positioning: NO. Columbia doesn’t have a structural “you can’t copy this without breaking your own model” advantage against mega-banks or fintechs. In theory, a mega-bank could decentralize decision-making and invest in relationship teams. A fintech could add humans and build a banker-led model. They generally don’t, because it would dilute what makes them efficient and scalable—but that’s their strategic tradeoff, not a unique shield Columbia has created.

Switching Costs: MODERATE. For commercial clients, moving banks is a real project. You’re migrating treasury management, changing operating accounts, rewiring payroll and payments, re-papering credit facilities, and bringing new bankers up to speed on how your business actually works. That friction creates stickiness. But it’s not a lock-in. If service slips or credit appetite changes at the wrong moment, customers will endure the hassle and leave.

Branding: MODERATE. Columbia—and the legacy Umpqua brand—carry real recognition in the region, along with generally positive associations. The positioning is straightforward: a community-banking feel with the capabilities to handle serious commercial needs. But this isn’t a national brand, and in commercial banking the brand that matters most isn’t the billboard—it’s reputation in the referral economy: accountants, attorneys, brokers, and business owners telling each other who they trust.

Cornered Resource: WEAK. There isn’t a single resource Columbia controls that rivals simply can’t access. Its management depth and M&A execution skill are valuable—and earned over time—but not uncopyable. The same goes for relationships: important, hard-won, and sticky, but never truly exclusive. Competitors are always calling on the same customers.

Process Power: MODERATE-STRONG. This is the heart of Columbia’s edge. It has a repeatable acquisition integration playbook, refined through decades of doing deals and living through the messy reality afterward. It also has embedded credit discipline—organizational muscle memory built across cycles that taught the bank what not to do. Those capabilities can’t be spun up overnight, and they’re surprisingly hard for competitors to replicate quickly, even if they understand the theory.

Overall Power Assessment: Columbia’s advantages are modest but real, anchored primarily in Scale Economies and Process Power. That’s why the company tends to produce solid, workmanlike profitability rather than the kind of outlier returns you see in businesses with stronger moats. These powers are mostly defensive: they help Columbia hold its ground, integrate growth, and survive shocks—more than they help it launch a clean offensive into entirely new territory.

XIII. Bull vs. Bear Case

The Bull Case

Proven M&A execution in a consolidating industry: For three decades, Columbia has shown it can find targets, buy them at sane prices, and actually integrate them without breaking the franchise. In a business where consolidation is less a trend than a gravity force, that makes Columbia a natural consolidator. The Pacific Premier deal closed cleanly, and the pipeline of potential sellers isn’t going away.

Flight to quality post-2023: The 2023 bank failures re-taught the market a lesson it periodically forgets: not all banks are the same. When confidence gets shaky, depositors and customers gravitate toward institutions that look well-capitalized, conservatively run, and boring in the best way. Columbia is built to be that kind of “safe pair of hands,” and periods of stress can translate into more stable deposits and stronger relationships.

Geographic footprint in growing markets: The Pacific Northwest has continued to attract people and investment, even through volatility. Seattle’s tech and business ecosystem, Portland’s mix of industries, and the region’s long-term demographic appeal create a tailwind for loans, deposits, and business formation. If the region grows, a bank with deep roots there tends to grow with it.

Synergy realization continues: The Umpqua integration has already produced meaningful expense reductions, and the Pacific Premier integration is now part of the operating agenda. The bull case assumes management keeps doing what it has historically done well: take costs out without losing customers, then keep tightening operations over time.

Trading below intrinsic value: Since 2023, regional bank stocks have spent long stretches in the penalty box. If the market is overly discounting the sector—and if Columbia’s credit performance and deposit base hold up—there’s room for valuation to recover simply as fear fades and fundamentals reassert themselves.

Essential infrastructure for the middle market: Columbia’s sweet spot is durable: middle-market businesses that need real banking—treasury management, credit facilities, decision-makers who can move quickly—but don’t get top-tier attention from the money-center giants. Not every business can, or wants to, bank with JPMorgan. Columbia exists because that gap is real.

The Bear Case

Regulatory burden increasing: After 2023, the direction of travel is clear: more scrutiny on liquidity, capital, and interest-rate risk. The problem for regional banks is that they can end up with big-bank style requirements without big-bank economics. Higher compliance overhead can weigh on returns for years.

Commercial real estate concentration risk: CRE is where regional banks make their money—and where they can get hurt. Columbia has meaningful exposure to office, a segment still working through the aftershocks of remote work. Management has emphasized a tilt toward suburban markets rather than the most stressed downtown cores, but office distress doesn’t need to be catastrophic to be painful. Even a slow grind of credit issues can drag earnings and sentiment.

Geographic concentration vulnerability: Columbia’s identity is tied to the Pacific Northwest. That’s an advantage when the region is strong, and a vulnerability when it’s not. A localized downturn—whether it’s aerospace weakness, a tech contraction, or a major natural event—could hit this franchise harder than a more geographically diversified bank. Expansion into California through Pacific Premier helps, but it doesn’t make the risk disappear.

Interest rate sensitivity: Banking is still, at its core, a spread business. Rate cuts can compress margins. An awkward yield curve can squeeze profitability. Deposit competition can force funding costs higher. Columbia can manage around these forces, but it can’t control the environment—and the wrong rate regime can make a good bank look mediocre.

Technology investment requirements strain efficiency: Customers expect great digital experiences now, and regulators expect more sophisticated risk management. Both require sustained spending. Even when M&A creates cost synergies, a meaningful chunk of those savings can get reinvested right back into technology and infrastructure, limiting how much efficiency improvement shows up in the bottom line.

Fintech encroachment continues: Relationship banking has held up better than many predicted, but fintech competition keeps creeping into specific products—payments, consumer deposits, certain lending niches. The risk isn’t that fintechs replace Columbia’s model overnight; it’s that they skim the easiest, highest-volume parts of the value chain and leave banks fighting harder for what remains.

Potential acquisition target: As Columbia gets bigger and cleaner, it gets more noticeable. That can make it attractive to even larger acquirers. A takeout could deliver a premium, but it’s not something investors can count on—or time. “Maybe someone buys it” isn’t a strategy; it’s a possibility.

XIV. Key Metrics to Watch

If you want to track whether Columbia is executing on the promise of scale without drifting into risk, there are three metrics that do an outsized amount of work.

1. Net Interest Margin (NIM): This is the core earnings engine—the spread between what Columbia earns on loans and securities and what it pays to fund them. In Q4 2024, Columbia’s net interest margin was 3.64%. The direction of that number matters more than the number itself, because it captures the real-time tug-of-war between interest rates, deposit competition, and shifts in what the bank is choosing to hold on its balance sheet.

2. Commercial Real Estate Credit Quality: CRE is one of Columbia’s biggest strengths—and the area where surprises can get expensive. Watch delinquencies, non-performing loans, and charge-offs in the CRE book, especially office. At the end of the first quarter of 2024, only 0.03% of Columbia’s office loans were either 30–89 days past due or in nonaccrual status. That’s pristine. The question is whether it stays that way as office markets continue to recalibrate.

3. Efficiency Ratio: This tells you whether scale is actually turning into better profitability. It measures how much revenue gets eaten by non-interest expenses. Integrations and cost saves should pull it down; technology spend and operating complexity push it up. One quarter won’t tell you much—what you’re looking for is a sustained trend that proves the combined company can run leaner without breaking the relationship model.

XV. Lessons for Founders, Operators & Investors

Discipline beats aggression: Columbia won by saying “no” more often than most banks could stand. It walked away from overpriced deals. It avoided hot markets. It kept underwriting tight while competitors loosened standards to keep up. None of that was exciting in the moment. Over decades, it became the difference between compounding and cleanup.

Culture eats strategy: The hard part of M&A wasn’t the announcement—it was the Monday morning after. Columbia treated integration as the real work: keep the best people, protect customer trust, convert systems without chaos, and preserve the community-banking feel even as the organization got bigger. In banking, the balance sheet is only half the asset; the relationships are the other half.

Play long games: This is not a business that rewards impatience. Brands are built one market at a time. Commercial relationships form over years, not quarters. Operational capability—especially the ability to absorb acquisitions—gets forged through repetition. Columbia’s arc is a reminder that the “secret” was time, consistency, and the willingness to keep executing when nobody was paying attention.

Know your competitive advantage: Columbia didn’t try to out-JPM JPMorgan or out-tech the fintechs. It focused on what it could do better than both: relationship banking for middle-market commercial customers who need real service and real judgment, not just a rate sheet or an app. The discipline was in the focus.

Crisis preparation pays: Conservative underwriting can look like self-sabotage during boom times. Then the cycle turns, and it becomes a superpower. In 2008 and again in 2023, Columbia’s “boring” balance-sheet management didn’t just reduce damage—it created options, letting the bank play offense when others were forced into defense.

Consolidation dynamics compound: Every successful integration made the next one easier. Each deal expanded the deposit base, spread fixed costs, and sharpened the playbook. Over time, Columbia didn’t just grow; it built an institutional muscle for consolidation that most competitors never develop, because they don’t do enough deals—or they do them badly.

Regulatory moats cut both ways: Regulation keeps new entrants out, which protects incumbents. But it also keeps getting heavier, and that weight lands hardest on banks without enough scale to absorb it. Columbia’s story underlines why “size” in modern banking isn’t about ego—it’s about having the economics to carry compliance, technology, and risk management without giving up the ability to compete.

XVI. The Future: What's Next for Columbia?

With the Pacific Premier acquisition in the books, Columbia sits at roughly $70 billion in assets, with a footprint that now makes it a leading player across many of the West’s biggest banking markets.

That’s a powerful position. It also creates a new set of questions—less about whether Columbia can grow, and more about what kind of institution it wants to become next.

Several strategic questions will shape Columbia’s next chapter:

Will Columbia remain independent? At around $70 billion in assets, Columbia is big enough to matter—and small enough to be bought. A super-regional or mega-bank could look at Columbia as a fast way to deepen a Western footprint. Whether shareholders are better off with long-term independence or a takeout premium will come down to execution, the rate environment, and how the market values regional banks in the years ahead.

More M&A or digest Pacific Premier? Columbia has earned its reputation as an acquirer. But there’s a difference between being good at deals and doing too many at once. Integrating Umpqua, absorbing Pacific Premier, and completing a major brand transition in close succession takes focus. At some point, the most strategic move may be the boring one: pause, integrate, simplify, and make sure the promised benefits actually show up in day-to-day operations.

Technology roadmap: Columbia’s competitive edge has always been relationships, but relationships increasingly run through software. The question isn’t whether to invest—it’s how to do it without letting costs run ahead of results. AI in underwriting, better digital banking experiences, and operational automation can improve speed and consistency, but only if they’re implemented cleanly and safely.

Commercial real estate navigation: The office market story still isn’t finished. Columbia’s long-term credit performance will depend on how it manages this portfolio through whatever comes next: restructuring borrowers early versus later, building workout capacity, recognizing losses when needed, and staying disciplined about what new office loans it chooses to make.

Leadership succession: Clint Stein has now led Columbia through the Umpqua integration and the Pacific Premier acquisition—arguably the most complex chapter in the company’s history. The next question is quieter, but just as consequential: who’s behind him? Melanie Dressel’s legacy wasn’t only growth—it was building the bench. Whether Columbia can keep its culture and execution advantage over the next decade will depend on whether that bench gets rebuilt again.

XVII. Epilogue: The Enduring Power of Regional Banking

In an era of global mega-banks and digital disruptors, Columbia Banking System is a case study in disciplined compounding. It didn’t get here by inventing a new category of finance. It got here the old-fashioned way: by doing the fundamentals better than most for a very long time. From four branches in 1993 to more than 350 locations and roughly $70 billion in assets three decades later, the story is less about breakthrough innovation and more about patient execution.

What stands out about Columbia isn’t any single swing. It’s the repetition. Conservative underwriting through multiple cycles. A willingness to walk away when deals didn’t pencil. An integration muscle built deal after deal, crisis after crisis. And an insistence that “relationship banking” wasn’t a marketing line—it was the operating system, even as the organization scaled beyond what most community banks ever become.

The regional banking model Columbia represents—local decision-making, a commercial relationship focus, and real community connection—has lasted longer than many predicted. Mega-banks have scale and product, but often struggle to feel truly local. Fintechs have speed and interface, but still run into the hard parts of banking: credit judgment, trust, and sticky operating relationships. And crises have repeatedly shaken the industry—yet Columbia has come out of multiple stress periods not just intact, but bigger.

For investors, it’s also a clean reminder of what regional banking is, and isn’t. The economics can be attractive, but they’re rarely magical. Competitive advantages tend to be real but modest. The stock is often pulled around by interest rates, deposit sentiment, and sector fear as much as by company-specific execution. That’s not a knock—it’s the terrain.

Within that terrain, Columbia has executed at an unusually high level. The acquisition playbook has held up. The credit culture has persisted. The benefits of scale have compounded.

“Boring is beautiful” is the right closing line. In an industry where aggressive growth often destroys more value than it creates, Columbia’s quiet discipline is exactly what turned a small Tacoma startup into a Western banking heavyweight. That’s why this story is worth understanding.

XVIII. Further Reading & Resources

If you want to go deeper, here’s where the real signal is.

Key Primary Sources: - Columbia Banking System annual reports (especially 2008, 2015, 2022, 2023, 2024). These are the best place to see how management explains risk, credit, deposits, and M&A when the cycle turns. - Umpqua merger S-4 filing and investor presentations, which lay out the logic of the deal, the integration plan, and the assumptions behind the synergy math. - Pacific Premier acquisition announcement and regulatory filings, for the strategic rationale and the specifics of the transaction. - FDIC Quarterly Banking Profile reports, for the clearest picture of what’s happening across the regional bank sector beyond any one company.

Leadership Background: - Ray Davis, "Leading for Growth: How Umpqua Bank Got Cool and Created a Culture of Greatness" - American Banker coverage of Melanie Dressel and Clint Stein, which captures how Columbia’s culture and operating discipline were built—and how leadership evolved as the bank scaled.

Industry Analysis: - Federal Reserve Supervision and Regulation reports, for the direction of travel on liquidity, capital, and interest-rate risk expectations post-2023. - Congressional Research Service, "Commercial Real Estate and the Banking Sector," for a grounded overview of why CRE keeps showing up as the fault line. - NYU Stern, "SVB and Beyond: The Banking Stress of 2023," for a crisp explanation of what actually broke, and what changed afterward. - S&P Global Market Intelligence bank M&A data, for context on consolidation trends and how deals are being priced.

Key Metrics to Watch: - Net interest margin trajectory - Credit quality in the commercial real estate book, especially office - Efficiency ratio progress as integration synergies flow through the income statement

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music