Coca-Cola Consolidated: The Quiet Giant of American Bottling

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture this: you walk into a grocery store anywhere from Virginia to Louisiana, reach into the cold case, and grab a bottle of Coca-Cola. The familiar red label. That sharp hiss when you crack the cap. The taste that hasn’t changed in over a century.

But here’s the part almost nobody thinks about: that bottle probably didn’t come from The Coca-Cola Company.

It came from a sprawling, industrial distribution empire headquartered in Charlotte, North Carolina—an operation that’s been run by the same family for more than 120 years.

Welcome to Coca-Cola Consolidated, ticker symbol COKE—and no, that’s not The Coca-Cola Company (that’s KO). Coca-Cola Consolidated is the largest independent Coca-Cola bottler in the United States, a roughly $7 billion revenue business serving about 65 million people across 14 states plus Washington, D.C. It manufactures, sells, and delivers beverages from The Coca-Cola Company and other partners—hundreds of brands and flavors—through a network of more than 300 facilities and distribution locations. And for more than 122 years, it’s stayed obsessively focused on the communities and customers in its territory.

That’s the central mystery of this story: how did what started as a regional bottler quietly turn into a monster consolidator—without getting swallowed by Coke itself?

The scale today is hard to overstate. As of December 31, 2024, the company employed about 17,000 people (they call them “teammates”), roughly 15,000 full-time and about 2,000 part-time. This is no longer a small Southern family business. It’s a system that stretches from Delaware down through the Carolinas and across to Louisiana.

And here’s what makes it even more interesting: this is a private equity story hiding in plain sight. Over the past decade, Coca-Cola Consolidated produced the kind of returns you’d expect from top-tier buyout funds—but instead of a tower full of MBAs in Manhattan, it’s been driven by a family that’s been in the Coca-Cola bottling business since 1902. As of December 31, 2024, J. Frank Harrison III—Chairman and CEO—controlled approximately 72% of the total voting power of the company’s outstanding stock.

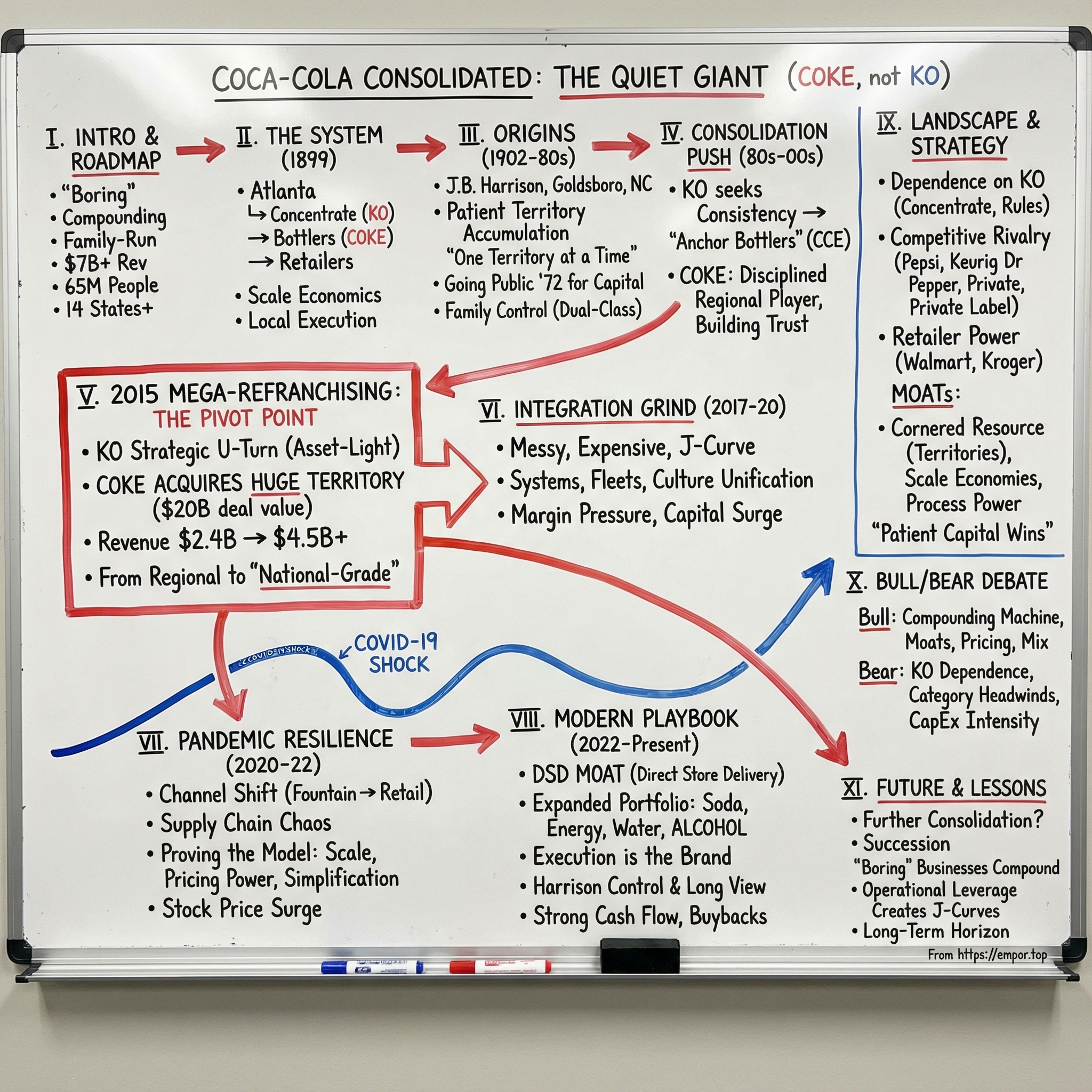

So this is the roadmap. We’re going to start with the genius of Coca-Cola’s franchise bottling system—one of the most elegant, underappreciated business models in American capitalism. Then we’ll follow the Harrison family’s slow, patient accumulation of territory, before hitting the inflection point: the 2015 mega-refranchising that reshaped the entire industry. From there, we’ll get into the messy, grueling integration—and the modern machine that emerged on the other side.

By the end, you’ll see why “boring” distribution businesses—capital-intensive, operationally demanding, often ignored—can compound wealth in ways that flashier companies often can’t.

II. The Coca-Cola Bottling System: Context You Need

To understand Coca-Cola Consolidated, you first need to understand one of the most ingenious business model innovations in American history: the franchise bottling system that Coca-Cola more or less stumbled into in 1899.

Picture Atlanta at the turn of the century. Coca-Cola was mostly a soda fountain drink—served at ornate counters where a druggist mixed syrup with carbonated water and sold it for a nickel a glass. Two Tennessee lawyers, Benjamin Thomas and Joseph Whitehead, walked in with a simple idea: let us bottle this stuff so it can travel.

Asa Candler, who controlled Coca-Cola at the time, didn’t think much of it. He believed the future was the fountain, not the bottle. And in a decision that still feels impossible to believe, he sold them perpetual bottling rights for one dollar. That contract went on to become one of the most valuable pieces of paper in business history.

Out of that deal came a three-tier system that still runs the show today.

At the top is The Coca-Cola Company: the concentrate maker, brand owner, and marketing engine. They produce the syrup, own the trademarks, spend enormous sums on advertising, and control what the products are.

In the middle are the bottlers: independently owned companies that buy concentrate from Coca-Cola, turn it into finished beverages by adding water and sweetener, package it in cans and bottles, and then get it to shelves.

At the bottom are the retailers—everything from Walmart to the corner store—who sell it to the rest of us.

So why would one of America’s great companies hand off manufacturing and distribution?

Because bottling is an industrial grind, and it’s expensive. You need plants, warehouses, trucks, coolers, vending equipment, and a small army of people running routes every day. In the early 1900s, Coca-Cola couldn’t realistically fund that infrastructure across the entire country. Franchising let them “crowdsource” the capital for national expansion—while they stayed focused on what they did best: branding and demand creation.

And there’s another advantage: bottling is local. The realities of servicing Charlotte, North Carolina are different from servicing Phoenix, Arizona—different store networks, different traffic patterns, different customer relationships, different competitive dynamics. The bottler on the ground knows which accounts need daily drops, which store manager wants help setting an endcap, and which competitor is quietly taking cooler space.

The economics are straightforward, and unforgiving. The bottler buys concentrate at prices that The Coca-Cola Company largely sets. Then the bottler does the heavy lifting—manufacturing, warehousing, and distribution—businesses with big fixed costs and thin margins. The upside comes from volume. The more cases you can push through your system, the more those fixed costs get spread out, and the better the unit economics become.

Which means bottling is, at its core, a scale game.

By the mid-20th century, the U.S. was covered with hundreds of small, often family-run bottlers. Many were deeply local institutions—prominent business families who’d secured territory rights decades earlier and handed them down across generations. Some territories were tiny, as small as a single county.

But scale economics don’t politely wait for tradition. They create pressure. A bottler serving five counties can’t match the route density, technology investment, or negotiating leverage of a bottler serving an entire region. Trucks don’t care about county lines; they care about making more stops with fewer miles. Bottling plants beg for volume. And as big retailers grew, they increasingly wanted partners who could coordinate across markets, not just one town at a time.

Consolidation wasn’t a question of if. It was when—and who would be the consolidator.

Those answers took decades to unfold. And in the end, they’re what turned a modest Carolinas bottler into America’s largest independent Coca-Cola bottler.

III. Origins: The Harrison Family & Building a Regional Powerhouse (1902–1980s)

In 1902—just three years after Thomas and Whitehead got their now-legendary bottling rights from Asa Candler—J.B. Harrison was in Goldsboro, North Carolina, looking at this strange new idea: Coca-Cola, but in a bottle. He secured the bottling rights for the Goldsboro territory, a small patch of eastern North Carolina. That modest foothold became the seed of what would eventually be Coca-Cola Consolidated.

What’s striking about the Harrison story isn’t a single daring bet or a once-in-a-lifetime deal. It’s the opposite. Over four generations, they built their position the way great operators often do: one territory at a time, one sensible reinvestment at a time, one neighbor bought out when the timing was right.

Early bottling was gritty work. You had to get production working reliably, build delivery routes from scratch, and convince store owners to stock something most customers had never seen in a bottle. And you had to do it with just enough cash left over to keep improving the business.

Then history threw its punches.

Prohibition arrived and, ironically, helped Coca-Cola as consumers shifted toward non-alcoholic alternatives. The Great Depression followed, when discretionary spending cratered—but a nickel Coke still fit into the category of affordable comfort. World War II brought sugar rationing and other constraints that threatened production and strained small bottlers.

Through all of it, the Harrisons kept the business standing. They reinvested what they could. And when smaller bottlers couldn’t keep up—whether from economic shock, capital needs, or simple exhaustion—the Harrisons were often there to absorb nearby territory. It wasn’t flashy. It was durable.

The expansion had a clear logic. Start where you’re strongest: eastern North Carolina. Push across the state. Step into South Carolina as openings appear. Get enough scale to justify better facilities and better equipment. And then let that operational edge widen the gap between you and the bottlers who couldn’t afford the next round of investment.

By the 1960s and 1970s, the Harrison operation had become a meaningful regional bottler in the Southeast—steady, respected, well run. But it was still small compared to the forces reshaping the Coca-Cola system. Coca-Cola Enterprises—later the dominant North American bottler—was assembling territories on a scale that made most independents look tiny.

Then, in 1972, the company did something most family bottlers avoided: it went public. Many peers preferred to stay closely held, keeping their finances private and their control absolute. The Harrisons chose access to public capital while still protecting control through a dual-class share structure. The family held Class B shares with superior voting rights, ensuring they stayed in charge even as outside shareholders bought the publicly traded stock.

Why take that route? Capital. Bottling was getting more and more asset-heavy. Filling lines, trucks, warehouses—every upgrade cycle required bigger checks. Public markets offered funding without giving up the steering wheel, and the public stock could also serve as currency for acquisitions.

Out of this history, a very specific culture took shape. Conservative by instinct. Cash flow over optics. Balance sheet strength over growth-at-any-cost. And relationships—inside the Coca-Cola system, with retailers, and with local communities—over whatever the quarter happened to look like.

Most importantly, the Harrisons built trust with The Coca-Cola Company. In a franchise system, that relationship is the whole game. Coke needed bottlers who would execute national programs locally, protect quality, invest in cold drink equipment, and represent the brand well in the market. The Harrisons proved, year after year, that they would do exactly that.

And that trust is what made them the natural buyer when the biggest opportunity in the company’s history showed up in 2015.

IV. The Coca-Cola Company's Bottler Consolidation Push (1980s–2000s)

By the early 1980s, The Coca-Cola Company had a problem that wasn’t showing up in the TV ads, but was absolutely showing up in execution: the U.S. bottler network was too fragmented, too unevenly capitalized, and increasingly vulnerable—especially next to Pepsi.

PepsiCo had been moving in the opposite direction for years. Through the 1960s and 1970s, it steadily bought up independent Pepsi bottlers and pulled distribution under tighter corporate control. That meant when Pepsi rolled out a new product, a promotion, or a pricing push, it could run the play nationally with consistency. One command center, one set of priorities, one system.

Coke, meanwhile, was still operating through a patchwork of hundreds of franchises—many excellent, many merely adequate, and some simply unable to keep up with the modern demands of big-box retail, route technology, and ever-rising capital needs. And when the system needed to move fast, the seams showed. The “New Coke” episode in 1985 is the clearest example: once the decision was made in Atlanta, getting the entire bottler network to pivot—and then to pivot back—was a logistical headache on top of a brand one.

So Coke went looking for a lever it could pull to create scale without fully dragging bottling onto its own balance sheet.

That lever was Coca-Cola Enterprises, formed in 1986. The idea was to build an “anchor bottler”: a large, publicly traded bottling company that could accumulate territory and cover a huge share of the U.S. population. The Coca-Cola Company kept a meaningful ownership stake, giving it influence and alignment—without owning the whole, low-margin, asset-heavy bottling machine outright.

It was, in many ways, a masterstroke. CCE could raise capital and invest in plants, trucks, and coolers at a scale that smaller bottlers couldn’t touch. Coke got a more coordinated system and a stronger counterweight to Pepsi—while still enjoying the economics Wall Street loved most: the high-margin concentrate business.

Underneath all of this sat the legal backbone of the franchise system: the agreements between The Coca-Cola Company and each bottler. These contracts define the territory, the required products, the standards for quality and execution, and the commercial mechanics of the relationship. In reality, they function less like a simple license and more like a detailed operating framework. The bottler is independent, but it is also, day to day, the face of Coca-Cola in its markets.

And here’s the tension that never goes away: pricing power flows downhill. The Coca-Cola Company sets concentrate pricing, and bottlers largely take it as given. Bottlers can try to pass those costs through to retailers, but the biggest retailers—especially the national giants—have leverage of their own. That push and pull is why bottling tends to be a business of thin margins and constant operational pressure.

So where did Coca-Cola Consolidated fit as this new world took shape?

They were solid. Disciplined. Well-run. But they weren’t the centerpiece. CCE was the consolidator with the spotlight; regional bottlers like the Harrison operation were more like dependable partners on the edges—important, but not the strategic priority.

Over the 1990s and 2000s, the direction of travel stayed the same. CCE got bigger. Independent bottlers shrank in number, either selling to CCE, merging to survive, or exiting when the next generation didn’t want to inherit a capital-intensive, operationally relentless business.

Coca-Cola Consolidated made it through by doing what it had always done: keep investing, run the routes well, protect the balance sheet, and play the long game. The Harrisons understood a simple rule of consolidation: when the cycle turns, optionality belongs to whoever still has financial flexibility and a reputation for execution.

What they couldn’t have seen yet was that The Coca-Cola Company was heading toward a strategic U-turn—one that would flip the entire bottling landscape and hand Coca-Cola Consolidated the opportunity of a lifetime.

V. The 2015 Mega-Refranchising: Everything Changes

The phone call that would remake Coca-Cola Consolidated came in 2014. It was The Coca-Cola Company. And the question wasn’t subtle: would the Harrison family be willing to take on a lot more territory—fast?

To see why Coke was even making that call, you have to rewind to the years around the financial crisis. The “anchor bottler” strategy that looked so elegant in the 1980s had started to turn messy in practice.

Through the 1990s and 2000s, Coke repeatedly found itself stepping in when bottlers underperformed or ran into financial trouble. When service levels slipped, shelves went empty, or a franchise holder teetered toward bankruptcy, Coke didn’t have the luxury of letting the market sort it out. The brand had to be protected. So Coca-Cola made what it called “bottler investments”—buying stakes, propping up operations, and, in some cases, taking more direct ownership than it ever intended.

Those fixes piled up. And every one of them pulled Coke further away from the story Wall Street loved: a high-margin, asset-light concentrate company.

Then 2008 hit. Debt-heavy bottling operations felt the pressure. Consumers pulled back. And the sheer complexity of running massive bottling territories—plants, trucks, labor, local execution—was the opposite of what Coke’s leadership wanted to spend their time on. The more Coke got dragged into bottling, the more it distracted from the company’s real superpower: building brands and driving demand.

By 2014, Muhtar Kent, Coke’s CEO, put words to what was effectively a strategic U-turn. Coca-Cola would return to being, as much as possible, a “pure” concentrate business again. That meant getting out of bottling in North America and pushing those territories back out to independent partners—refranchising at an enormous scale. Asset-light. Higher margins. Lower capital intensity. Cleaner narrative.

This became the 2015 mega-refranchising—one of the largest distribution handoffs in modern American business.

Coke announced it would sell off vast territories that had been operated inside its bottling orbit, much of it previously associated with Coca-Cola Enterprises through various restructurings. Taken together, the territories changing hands were valued at close to $20 billion. In plain English: this was a generational land grab, and only a few players had the capital, operational credibility, and appetite for complexity to even participate.

Frank Harrison III recognized the moment immediately. The Harrison family had spent more than a century building patiently, territory by territory, into a strong regional bottler. This was the breakout chance—the kind that doesn’t come along twice. Coke wasn’t just allowing scale. It was asking for it.

In 2017, Coca-Cola Consolidated closed on the acquisition of major territories across the Southeast and Mid-Atlantic. The change was instant and dramatic. Revenue leapt from around $2.4 billion to more than $4.5 billion. The map expanded from a Carolinas core into Virginia, Maryland, West Virginia, Tennessee, and beyond.

Suddenly, they weren’t “a Carolinas bottler.” They were operating a footprint that stretched from the Pennsylvania border down toward the Florida panhandle, and from the Atlantic coast across toward the Mississippi River. A regional player, now big enough to start thinking in national terms.

Of course, you don’t double a business like this with spare change. The financing was complicated, and leverage rose. But the acquired territories came with real volume and real cash flow, and The Coca-Cola Company provided financing support as well—more like a partner making sure the system stayed healthy than a distant franchisor collecting rent.

So why the Harrisons? The fit was unusually clean. They had a century-long record of execution. They could access capital as a public company. They were willing to swallow the integration risk. And just as important, they weren’t trying to become a rival power center inside the Coke universe. They wanted to be the best bottler—full stop.

For investors, this was a classic J-curve bet. Integration would be costly, margins would take a hit before they improved, and the execution risk was very real. But if it worked, Coca-Cola Consolidated would come out the other side as a fundamentally different company: a scaled platform with the economics—and the credibility—to keep consolidating.

VI. Executing the Integration: The 2017–2020 Transformation

The celebration after the mega-deal lasted about a business day. Then the real work started.

Integrating bottling territories isn’t like integrating software companies or banks. You can’t hop on a few calls, harmonize org charts, and declare victory. Beverage distribution is relentlessly physical: pallets moving through warehouses before dawn, trucks threading through traffic, coolers being serviced in corner stores, shelves needing to be full when shoppers walk in. If the integration slips, product doesn’t move—and The Coca-Cola Company notices immediately.

And the scope here was staggering. Coca-Cola Consolidated wasn’t just taking over a map. It was inheriting entire operating systems: warehouses, fleets, salesforces, frontline routines, customer expectations, and a patchwork of technology. Many of those newly acquired operations had been run under Coca-Cola Enterprises and its successors—competent, but built with different assumptions than the Harrison family’s lean, locally grounded style.

So the company went into build mode.

Capital spending surged. Facilities needed upgrades. Some needed expansion. Equipment had to be standardized. And the technology stack—often a collection of older, incompatible systems—had to be pulled into something that could actually run a much bigger enterprise. The 2018 and 2019 spending levels were unlike anything the company had done before, because there was no other way to make the machine run as one.

Even something as “simple” as routing became a major project. In the legacy Carolinas business, route knowledge had been refined for decades: which stores wanted deliveries early, which ones had cramped docks, which accounts needed extra merchandising help. After the acquisition, Coca-Cola Consolidated suddenly had thousands of routes across unfamiliar markets—run by drivers who had learned different processes, under different managers, with different expectations. To get efficiency, they had to relearn the terrain and then redesign it.

The technology transition was its own kind of pain. Orders, inventory, dispatch, billing, accounts receivable—none of it works if the systems can’t talk to each other. And even when the software is chosen, the hard part begins: training thousands of people who’ve done their jobs the same way for years, sometimes decades. In distribution, a “system rollout” isn’t an IT milestone. It’s a daily operational risk.

The workforce numbers capture the reality best. Before the 2017 acquisition, Coca-Cola Consolidated had around 6,000 employees. Within a year, it had more than 16,000 “teammates” spread across 14 states. This wasn’t a hiring spree. It was the absorption of whole organizations—each with its own identity, pay practices, and ways of working—into a single company that needed to function immediately.

Through all of it, J. Frank Harrison III held the line on the long game. Integration was going to be expensive, and it was going to look messy quarter to quarter. He resisted the temptation to underinvest just to make near-term results look cleaner. He visited facilities across the newly expanded footprint to communicate what mattered to the Harrison family: service, operational excellence, and a purpose-driven culture rooted in faith. People in Richmond, Nashville, or Chattanooga needed to feel that Charlotte wasn’t just a new headquarters sending directives—it was ownership that planned to be there for decades.

And, predictably, the early numbers weren’t pretty. Margins tightened as integration costs hit the P&L. Operating profit didn’t keep pace with the sudden surge in revenue. Cash flow was pressured as capital spending soaked up cash. The stock, which had run up into the deal, went quiet afterward.

Public market patience is rarely built for this kind of J-curve. The playbook—invest hard up front, absorb disruption, then earn it back through scale and efficiency over the next several years—makes all the sense in the world operationally. It just doesn’t always look good on a quarterly chart.

The Coca-Cola Company was involved throughout. It offered support, but it also kept a close eye on execution. Atlanta sent teams to track progress, monitor service levels, and make sure the brand was being represented the way Coca-Cola expects in every market. The relationship was aligned, but not frictionless: Coke needed this to work, and it also needed to protect itself if it didn’t.

By late 2019, the first signs of progress showed up. Routes were getting tighter. Systems were coming together. Productivity began to improve as training stuck and best practices spread. The acquired territories started to resemble the disciplined Carolinas operation that had earned the Harrisons so much trust in the first place.

Then COVID-19 arrived.

VII. COVID, Supply Chain Chaos, & Proving Resilience (2020–2022)

March 2020 hit like a surprise audit from reality. Just as Coca-Cola Consolidated was finally getting its arms around the post-2017 integration, the world shut down—and the beverage business got remapped almost overnight.

People didn’t stop drinking Coke. They just stopped drinking it in the places the system had been built to serve. Restaurants, stadiums, movie theaters, and office cafeterias went quiet. Meanwhile, grocery and convenience stores became the front line. Demand didn’t vanish; it snapped from one channel to another.

For a distribution business, that’s not a marketing problem. It’s an operational emergency.

Routes that used to hit downtown lunch spots suddenly had nowhere to go. Trucks and drivers geared for foodservice runs needed to be redeployed into retail-heavy corridors. And the product mix swung hard toward take-home packages—multi-packs for the pantry and fridge—instead of single-serve bottles meant for commuting, events, and impulse buys.

Coca-Cola Consolidated moved faster than many would’ve expected, and a big reason was timing. The painful work of 2017 to 2019—unifying systems, tightening routes, modernizing operations—turned out to be exactly what you’d want in a crisis. With better visibility and coordination across the network, the company could reshuffle people, change delivery patterns, and reposition inventory in ways that simply wouldn’t have been possible with the fragmented systems it inherited.

Then came the problems nobody could solve with better routing software.

Aluminum cans became scarce as at-home consumption surged and consumers stocked up on canned goods. Trucking tightened, with driver availability dropping and capacity getting bid up. Warehouses and plants dealt with unpredictable staffing as illness moved through workforces. Even when demand was there, getting the right package in the right place at the right time became a daily fight.

Coca-Cola Consolidated got through it, and three things really mattered.

First: scale. Bigger operators can shift production between facilities, carry more buffer inventory, and get more attention from suppliers. The same size that made integration hard in 2017 became a shock absorber in 2020.

Second: pricing power showed up when it counted. As inflation took hold in 2021 and intensified in 2022, price increases finally moved through the system. Coca-Cola brands have real pull. Consumers don’t treat them like a generic commodity, and retailers can’t afford to be out of stock on the category leader. That dynamic gave the bottler room to pass along higher costs.

Third: COVID forced simplification. The whole industry leaned into a “less is more” approach—fewer flavors, fewer niche packages, more focus on the core sellers that keep lines running and trucks efficient. What started as crisis triage turned into a genuine operational upgrade: better throughput, less complexity, fewer headaches.

And the results caught attention. After the margin pressure of the integration years, 2021 and 2022 looked like a different company. Profitability improved as efficiency gains started to stick. Free cash flow swung positive. The balance sheet began to heal after being stretched to fund the big territory expansion.

The stock followed. Shares that had traded around $250 before the pandemic moved past $600 by late 2022. Wall Street, which had mostly treated Coca-Cola Consolidated like a sleepy bottler with a complicated integration story, started to price it like what it had become: a scaled, resilient distribution machine.

More than anything, COVID served as the proof test. It showed that the company could execute when the playbook broke, when demand moved under its feet, and when the supply chain stopped cooperating. The Harrison family’s approach—invest through the mess, protect service, and play for the long term—didn’t just survive the stress. It looked validated by it.

VIII. The Modern Playbook: What Makes COKE Tick Today (2022–Present)

Walk into a convenience store anywhere from Virginia to Louisiana today and you’re watching Coca-Cola Consolidated’s modern machine at work. The cold vault is full, the endcaps are set, the shelf tags are right, and the product is where it’s supposed to be—because someone in a COKE uniform has been there, physically, to make sure it happens. That’s the business. Not the logo. The execution.

What’s changed in recent years is what’s riding on those trucks.

The portfolio has moved well beyond “just soda.” Coca-Cola, Diet Coke, and Sprite still anchor the system, but a growing share of momentum comes from adjacent categories that carry different price points and different consumer occasions. Energy has been a major driver—particularly Monster and Reign, which Coca-Cola Consolidated distributes. Sports drinks are another pillar, with BODYARMOR—acquired by The Coca-Cola Company in 2021—moving through the same routes and coolers. And premium water has quietly become a meaningful part of the mix, with price points that would’ve sounded absurd a decade ago for something that’s, on paper, just water.

Then there’s the most surprising addition: alcohol.

Topo Chico Hard Seltzer was Coca-Cola’s early push into alcoholic beverages using the bottler network. In 2023, the Jack Daniel’s and Coca-Cola ready-to-drink cocktail took that idea a step further—leveraging the same distribution footprint for an entirely new category. For a company built on non-alcoholic beverages, these products come with real complexity: different regulations, different rules in the store, and sometimes different relationships to manage. But strategically, it’s the same logic as energy and premium water: premiumization that lifts revenue per case without changing the fundamental engine.

That engine is direct store delivery, or DSD—and it’s still the moat.

Unlike packaged goods companies that ship to retailer warehouses and hope the store figures out the rest, Coca-Cola Consolidated delivers straight to the shelf. Their people don’t just drop product; they manage inventory, build displays, and fight for placement in the most valuable real estate in the store. It’s more expensive than warehouse delivery, but it’s also much harder to replicate at scale. In practice, it turns distribution into a service business—and it makes the bottler far more embedded with the customer.

Cold drink equipment makes that moat deeper. Those Coca-Cola-branded coolers you see everywhere? Coca-Cola Consolidated owns them, places them, and services them. When a retailer gives Coke that space, they’re not just buying drinks. They’re getting equipment, maintenance, and a system that keeps the cold box full. Over time, that creates real switching costs—both psychological and physical.

The customer set is just as important, and just as demanding. Walmart is a major account, but so are regional grocers like Food Lion, dollar stores like Dollar General, independent convenience stores, and countless local operators. Each channel wants something different: different service cadence, different promotions, different pricing mechanics. Running all of that at scale—without losing execution quality—is one of the most underappreciated advantages in the business.

Over all of it sits the Harrison family’s control. Through the dual-class structure, J. Frank Harrison III controls about 72% of the voting power while owning a much smaller economic stake. That setup gets criticized in some governance circles, but it also explains how this company consistently behaves: there’s no looming hostile takeover, no activist campaign demanding short-term optics, and no temptation to starve the system of investment to hit a quarterly number. The family can keep doing what it has done for four generations—reinvest, compound, and think in decades.

That philosophy shows up in capital allocation. Coca-Cola Consolidated continues to pour money into the unglamorous essentials: distribution centers, technology, fleets, and cold drink equipment. It continues to do tuck-in territory acquisitions when the opportunities appear. Dividends have risen, but they’re not the centerpiece. In 2024, the company also announced a major share repurchase program—returning cash to shareholders while still keeping the balance sheet flexible.

And now, after years of integration spending, the operational leverage is finally showing up in a way even the public markets can’t ignore. The same investments that looked like drag in the late 2010s—systems, facilities, process discipline—are turning into better productivity and stronger margins. The J-curve that started with the 2017 leap is, at last, bending upward.

For fiscal year 2024, income from operations increased $86 million to $920 million. During 2024, the company invested over $370 million in capital expenditures, repurchased approximately $626 million of Common Stock, and increased the annualized regular dividend.

This is what makes COKE so unusual as a public company. It isn’t a story about reinvention or hype. It’s a story about compounding: building advantage through scale, relationships, and relentless execution—then letting time and repetition do the work. The Harrison family has been playing that game for 122 years.

IX. The Competitive Landscape & Industry Dynamics

Coca-Cola Consolidated doesn’t operate in a quiet little corner of the beverage world. It sits in the middle of a complicated battlefield, pulled in four directions at once: other Coke bottlers, The Coca-Cola Company itself, rival beverage brands, and retailers that have grown big enough to throw their weight around.

Start with the closest peers: the other large independent Coca-Cola bottlers. Liberty Coca-Cola Beverages runs the New York metro area—arguably the most dense, high-stakes, logistically unforgiving beverage market in the country. Swire Coca-Cola covers much of the West, from Colorado up through Washington. Reyes Holdings, through its beverage division, is a major player in the Midwest and other regions. Same basic job, wildly different operating environments—and different styles of execution.

But the real competitive dynamic isn’t bottler-versus-bottler. It’s bottler-versus-gravity: the constant push and pull with The Coca-Cola Company. People ask, “Is this a partnership, or are bottlers basically puppets?” The honest answer is: both, depending on the day.

On one side, Coca-Cola Consolidated is deeply dependent on Coke. Approximately 85% of bottle/can sales volume consists of Coca-Cola products. The franchise agreements give The Coca-Cola Company enormous influence over what gets sold, how it gets sold, and what standards the bottler has to meet. If Coca-Cola ever decided to take back territory—as it has in other markets—it would be an existential event for COKE.

On the other side, Coke needs bottlers that execute. The whole point of the 2015 refranchising was that Atlanta didn’t want to run plants, fleets, and warehouses. It wanted partners who would invest, keep service levels high, and win locally. A great bottler doesn’t just move product; it protects the brand in the moments that actually matter—when shelves are empty, when a promotion breaks, when a competitor tries to steal cooler space.

That’s why Coca-Cola owns a stake here—but not control. The Coca-Cola Company holds approximately 7% of Coca-Cola Consolidated’s voting power, enough for a board seat and alignment, not enough to run the company. It’s a deliberately awkward middle ground: partnership with leverage on both sides.

Under the hood, the franchise agreements are where the relationship gets real. These comprehensive beverage agreements spell out the rules of the game: who serves which territories, what products must be carried (and what can’t be), how concentrate pricing works, what marketing support looks like, the quality standards that must be met, the reporting requirements, and even how disputes get resolved. Bottlers don’t have much freedom to go off-script—you won’t see a Coca-Cola Consolidated truck delivering Pepsi. But in some markets, they can distribute non-competing brands through separate agreements, including Dr Pepper.

Looking across the aisle at Pepsi makes the strategic trade-off obvious. PepsiCo runs a much more integrated model, owning most of its North American bottling operations directly. That gives Pepsi tighter central control—but it also means Pepsi carries the full weight of the capital-intensive distribution machine. Coke’s refranchised model is the opposite bet: give up some control, keep the balance sheet cleaner, and rely on independent bottlers to execute at a high level.

Then there’s the broader category war. Dr Pepper Keurig is a real competitor, even if it sometimes shows up on the same truck. Energy drinks have also changed the fight. Red Bull built its own direct-store-delivery system and competes aggressively for shelf and cooler space, right where a bottler wants to win. And private label is always lurking—especially at retailers like Walmart—offering cheaper alternatives. The limiter there is demand: consumers might buy a store-brand cola sometimes, but Coke is still the must-have brand that drives the category.

Finally, you can’t talk about today’s bottling business without talking about retailers. When the Harrison family started, the customer base was fragmented: thousands of small grocers, local operators, and mom-and-pop accounts. Today, a handful of giants—Walmart, Kroger, Costco, and others—dominate volume. They negotiate hard, demand promotional support, and increasingly bring their own data and category management playbooks to the table. But they can’t opt out of Coca-Cola. For most of them, not carrying Coke isn’t a negotiating tactic; it’s unthinkable.

And underneath every one of these dynamics is the true law of the business: route density and logistics are everything. The bottler that can deliver more cases with fewer miles, fewer empty truck hours, and fewer wasted stops gets better unit economics. Better unit economics fund more investment in service and execution. Better execution wins more space and more business. That flywheel is why consolidation keeps happening—and why the small operators keep getting squeezed.

The endgame is still unfolding, but the direction is clear: fewer bottlers, each covering more territory, each running a more efficient system. Whether the future is three, four, or five major independent bottlers, Coca-Cola Consolidated is positioned to be one of the survivors—and likely one of the consolidators.

X. Strategy & Business Model Analysis

With the history and competitive dynamics in place, you can now see Coca-Cola Consolidated for what it really is: a company with some unusually strong structural advantages—and one unusually immovable constraint. Strategic frameworks make that trade-off painfully clear.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Supplier Power: HIGH. The Coca-Cola Company isn’t just a supplier; it’s the brand owner, the concentrate maker, and the rule-setter. It controls concentrate pricing, product formulations, marketing priorities, and large parts of how the bottling system operates. Coca-Cola Consolidated doesn’t negotiate from a position of strength here. If Atlanta changes the terms, the bottler’s job is to execute—or accept that its entire business model is at risk. That dependence is the core strategic limitation.

Buyer Power: MODERATE-HIGH. On the customer side, the power is split. At the top end, a handful of giants—especially Walmart—buy enormous volume and negotiate relentlessly. Other national and regional chains have similar leverage. But the customer base also includes thousands of smaller accounts that don’t have the same muscle. And there’s an important counterweight: Coca-Cola products are not optional. Retailers can squeeze on price and promotions, but they can’t simply decide not to carry Coke without taking a hit in traffic and category performance.

Threat of New Entrants: LOW. This is one of the cleanest “moat” stories you’ll ever see in distribution. The territory is contractually locked. You can’t just decide to start a new Coca-Cola bottler in an existing Coca-Cola Consolidated market—the franchise rights are already spoken for. Even if you could, the infrastructure requirements would be enormous: plants, warehouses, trucks, coolers, people, systems, and years of relationship-building. The practical answer is that new entry isn’t hard. It’s effectively impossible.

Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE-HIGH. Consumer tastes move. The long-term trend line has been challenging for sugary carbonated soft drinks, and “share of stomach” gets fought over by water, coffee, energy, functional beverages, and whatever comes next. Health and wellness concerns add real pressure. The good news for Coca-Cola Consolidated is that substitutes don’t bypass the bottler—they often ride on the same trucks. As the portfolio shifts, the company adapts by distributing those newer categories through the same cold boxes, warehouses, and routes.

Competitive Rivalry: MODERATE. Bottlers aren’t really head-to-head competitors with each other because the system is geographic. Coca-Cola Consolidated doesn’t fight Liberty Coca-Cola for the same shelf space in the same stores; they serve different territories. Rivalry shows up in the store, against Pepsi systems, Dr Pepper systems, energy drink players, and private label—all competing for placement, displays, and mindshare. But Coca-Cola’s brand strength and the territorial structure keep the rivalry from becoming a pure price war.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: This business rewards density. The more stops you can pack into a route, the better your cost per case. The more volume you run through a plant and warehouse, the better your utilization. The more cases you ship, the more you can justify investments in technology and automation. Scale isn’t just helpful here; it’s the game.

Network Effects: Not the classic “users attract users” dynamic, but there’s a softer compounding effect. Better route density and stronger service make you a more valuable partner to retailers, which makes it easier to win more displays and more space. And broad retail coverage makes you more attractive to brand partners that want reach.

Counter-Positioning: Not really applicable. Coca-Cola Consolidated isn’t winning by reinventing the model. It’s winning by operating the model extremely well, at scale.

Switching Costs: Switching is friction-heavy. Coca-Cola Consolidated places and services cold drink equipment in stores. Its teams manage shelves, inventory, and promotions. Relationships are built store by store, route by route. Even if a retailer wanted to change, the practical burden—equipment, staffing routines, and execution—makes switching painful. And for core Coca-Cola products, there often isn’t a true “switch” available anyway.

Branding: The global brand power belongs to The Coca-Cola Company. But bottlers still build something valuable: an execution brand. Retailers remember who keeps the shelves full, who fixes problems fast, and who makes their category look good. Over time, that reputation becomes a real asset.

Cornered Resource: The crown jewel. Exclusive franchise territories are a cornered resource—hard contractual rights to distribute some of the most valuable beverage brands in the world across defined geographies. Competitors can’t buy their way into that position. They can’t out-hire it. They can’t out-innovate it. The rights are the rights.

Process Power: Direct store delivery, route optimization, cold drink execution, merchandising discipline—this is deeply learned, operational craft. It’s built through repetition, training, and systems that get better over decades. You can copy the concept, but copying the competence is much harder.

Primary Powers: Cornered Resource + Scale Economies. This is the engine. Exclusive territories create a protected base of volume, and scale turns that volume into better unit economics. Better economics fund better execution and investment. And that, in turn, makes Coca-Cola Consolidated the kind of operator that gets offered more territory when the system reshuffles again.

XI. Bull vs. Bear Case & Investment Considerations

At this point in the story, Coca-Cola Consolidated starts to look less like “a bottler” and more like an investment debate wrapped around one big question: is this a protected compounding machine—or a great operator stuck inside someone else’s system?

The honest answer is that it can be both. So let’s lay out the bull case and the bear case the way a real investor has to: with the best arguments on each side.

The Bull Case

The foundation is unusually strong: monopolistic territories paired with category-leading brands. In its footprint, Coca-Cola Consolidated doesn’t compete with another distributor for Coca-Cola products. If you want Coke, Sprite, or Diet Coke delivered into those markets, this is the route system that does it. That moat isn’t a brand story or a “we’re better at sales” story. It’s contract rights.

And the consolidation runway still appears long. Even after the 2017 step-change, the U.S. bottling map remains fragmented. Over time, smaller operators hit the same wall—succession issues, capital needs, complexity—and territory changes hands. When that happens, Coca-Cola Consolidated is positioned the way you want a consolidator positioned: scaled, trusted by Atlanta, and able to finance and integrate.

The margin story also has a very believable “still early” feel. The company spent years absorbing territories, modernizing systems, and tightening operations. Those investments tend to show up in the P&L late. When the machine starts to run smoother—better routing, better warehouse throughput, better labor productivity—you get operating leverage without needing heroic top-line growth.

Then there’s the ownership structure. Frank Harrison III’s voting control makes this company behave differently than most public equities. It doesn’t have to optimize for a quarter. It can keep reinvesting in the unglamorous things that actually widen the moat: equipment, facilities, systems, execution. That’s the kind of alignment that can compound for a long time.

Pricing power has also been demonstrated, not just claimed. The inflationary stretch from 2021 through 2023 was the stress test: costs rose, and the system still found room to move pricing without demand collapsing. When you distribute must-have brands, you often get more pricing flexibility than a low-margin business “should” have.

Finally, mix keeps improving. The trucks are increasingly carrying products with higher price points and different consumption occasions—energy, premium water, and now alcohol products in certain markets. Even if carbonated soft drinks are mature, revenue per case can still move up as the portfolio premiumizes.

Put that together and you get the bull view: protected territory, scale economics, a still-unfolding efficiency story, and a family owner willing to play the long game.

The Bear Case

The biggest risk is also the simplest: The Coca-Cola Company controls the ecosystem. Concentrate pricing, product requirements, marketing priorities, and, ultimately, the franchise relationship itself are set in Atlanta. If Coke ever decided to tighten the screws—through pricing, terms, or territory decisions—the bottler doesn’t have many levers to pull in response. This is the paradox of the whole system: you’re protected from competitors, but dependent on your most important partner.

The long-term category trend is another real concern. Carbonated soft drink consumption in the U.S. has been declining for years. Health concerns, sugar scrutiny, and changing preferences don’t disappear just because execution is great. Diversification helps, but the core still matters.

Then there’s capital intensity. This is a business that demands constant reinvestment: fleets, facilities, production lines, cold drink equipment, and technology. Even when accounting earnings look strong, a meaningful portion gets recycled right back into the physical system just to keep service levels high and assets current.

Concentration risk sits underneath everything. If roughly 85% of volume is Coca-Cola products, then the bottler’s success is tied to the strength of brands it doesn’t own. Execution can win at the margin, but it can’t change the strategic direction of the Coca-Cola portfolio.

Retailers can also squeeze. The customer base includes giants with real leverage, and retail consolidation has only increased that power. When your biggest customers negotiate harder and demand more promotional support, it can compress profitability—especially when costs are rising.

And costs do rise. Labor remains a major input: drivers, warehouse teams, and route sales. Fuel, packaging, and logistics create ongoing volatility. The whole system works best when price increases can keep pace with cost increases; when they can’t, margins get hit.

Finally, there are practical public-market issues. Coca-Cola Consolidated is still a relatively small-cap company with concentrated family ownership, and the stock can be thinly traded. That limits who can own it at scale and can amplify price moves in both directions.

Key Metrics to Watch

If you’re tracking the story from here, a handful of signals matter more than any single quarter:

Revenue per case is the cleanest read on pricing power and mix. If revenue per case keeps rising faster than volume, it usually means the company is pushing through price and shifting the portfolio toward higher-value products.

Operating margin trajectory tells you whether the post-integration machine is actually getting more efficient. The bull case depends on operating leverage showing up over time; persistent margin pressure suggests costs or customer dynamics are winning.

Free cash flow conversion is the reality check. This is a capital-heavy business, so the question isn’t just “are earnings up?” It’s “how much of that turns into cash after the system has been maintained and upgraded?” Improving conversion is a sign that the model is maturing into a true compounding engine.

XII. Lessons for Founders & Investors: The Playbook

Coca-Cola Consolidated’s 122-year run is an unusually clean case study in how unglamorous businesses create enduring advantage. And the lessons travel well beyond beverages.

Patient capital wins. The Harrison family built with a time horizon that most public companies simply can’t match. That let them invest ahead of need, live through stretches when results looked unimpressive, and still be ready when the once-in-a-generation opening arrived. In a world trained to react to the next quarter, patience becomes a competitive weapon.

Know your role. The Harrisons never tried to be a brand company. They didn’t chase consumer marketing glory or try to own the relationship with the drinker. They focused on what they could uniquely control: execution in the market, the quality of the routes, the reliability of service, and the discipline of operations. In a franchise model, that clarity matters. The fastest way to destroy a good franchise is to pick a fight with the franchisor by pretending you’re the one who owns the brand.

Consolidation playbooks matter. Being the buyer in a consolidating industry isn’t luck; it’s preparation. You need financial flexibility, systems and talent that can absorb complexity, access to capital, and credibility with the entity that controls the chessboard. Coca-Cola Consolidated spent decades building those muscles, so when Coke came looking for partners in 2015, the Harrisons were ready to say yes—and actually deliver.

Franchise dynamics require navigation. Partnering with a giant brings enormous benefits—global brands, marketing muscle, product innovation—but it also means you live inside someone else’s ecosystem. The Harrisons managed that tension by being relentlessly dependable: invest, execute, protect the brand, don’t posture, don’t threaten the power center in Atlanta. In franchise systems, performance is important, but diplomacy is part of the job.

Operational leverage creates J-curves. Big acquisitions almost always look worse before they look better. Costs and disruption hit immediately; the efficiency gains show up later, if you do the work. Operators and investors who understand that timeline can hold steady through the ugly middle. The ones who demand instant perfection usually exit right before the payback.

Hidden gems compound quietly. For years, Coca-Cola Consolidated lived in a corner of the market most people ignored. That obscurity was an advantage: less noise, less pressure to manage optics, more freedom to invest for the long term. Sometimes the best compounding happens where the spotlight isn’t.

Distribution is a moat. It’s easy to underestimate the defensibility of moving physical product—until you try to replicate it. Trucks, warehouses, cold drink equipment, routing density, labor, and retailer relationships don’t scale with a clever interface. Last-mile distribution is still stubbornly real, and that reality gives great operators durable staying power.

Family control structures enable long-term thinking. Dual-class shares are controversial for good reasons. But in this case, concentrated voting control made the strategy possible: invest through the integration years, ignore short-term market moods, and play for decades. The trade-off only works when the controlling family earns the trust—and keeps earning it.

Scale threshold effects create winners. In distribution, small operators can survive, but they struggle to thrive. Once you cross certain thresholds, the economics change: technology investments start to pay off, routing gets denser, purchasing improves, and best practices spread faster. The 2017 expansion pushed Coca-Cola Consolidated over those thresholds, turning what used to be a regional bottler into a platform with national-grade economics.

XIII. Recent Developments & The Road Ahead (2023–2025)

The story didn’t end when the integration dust settled. If anything, the last couple years have clarified what Coca-Cola Consolidated is trying to become: not a one-time refranchising winner, but a long-term compounding platform.

The earnings trajectory has stayed strong. In fiscal year 2024, income from operations reached $920 million, up $86 million from the prior year. And they did it while still spending like an operator, not a financial engineer—investing over $370 million in capital expenditures even as they returned meaningful cash to shareholders through buybacks and dividends.

That shareholder return piece is the newer twist. In 2024, the company announced it intended to repurchase up to $3.1 billion of its Common Stock—a big statement for a business that historically prioritized reinvestment above almost everything else. During 2024, it repurchased approximately $626 million of Common Stock and increased the annualized regular dividend. The message was clear: the balance sheet had strengthened enough that they could do both—keep upgrading the system and still send cash back to owners.

On the map, the expansion now looks more like steady stitching than a single dramatic leap. Territory tuck-in acquisitions continue to build out the footprint. Nothing has come close to the scale of 2017, but Coca-Cola Consolidated has kept adding territory opportunistically as smaller bottlers become available, gradually filling in gaps and improving density.

The product mix is also where the future gets decided—especially in energy. Energy drinks remain a battlefield, with Red Bull, Monster, Celsius, and a steady stream of new brands fighting for cooler space and consumer attention. Coca-Cola Consolidated benefits from Monster’s strength, but this category is more fragmented and faster-moving than traditional soft drinks. It creates real upside, and real complexity, for the distributor that has to execute in the store.

Alcohol is the other frontier. The Jack Daniel’s and Coca-Cola ready-to-drink product launched in 2023, and Topo Chico Hard Seltzer represents another early move into alcohol distribution. If these bets work, they expand the addressable market and push more premium dollars through the same routes. If they don’t, they risk becoming distractions that burn time and resources without paying back.

Underneath all of it, the company keeps leaning into technology—less “tech company,” more “better machine.” Technology investments target AI and analytics, especially around route optimization and predictive analytics to improve efficiency. Demand forecasting, inventory management, and maintenance scheduling can all get smarter with better data. None of this is flashy, but in a high-volume, low-margin business, incremental efficiency gains can be worth a lot.

And then there’s the pressure that keeps building in the background: sustainability. Packaging waste, water usage, and carbon footprint are drawing more attention from regulators, investors, and consumers. Coca-Cola Consolidated has to navigate those pressures without breaking the economics of the system—a balancing act that will require ongoing investment and adaptation.

Looking ahead, a few scenarios are easy to imagine. Further consolidation still seems likely as smaller bottlers exit and territories become available. Private equity interest could emerge, because the business model can generate substantial cash flow and has monopolistic characteristics within defined territories. Strategic alternatives—including a potential sale to The Coca-Cola Company or a merger with other bottlers—remain possible if the right price ever materialized.

And over all of it hangs the most human question in the whole story: succession. Frank Harrison III led the company through its most transformative era. Whether the next generation of Harrisons chooses to carry the torch—and whether they can sustain the operational and strategic discipline that made this run possible—will shape whatever the next century looks like.

XIV. Epilogue & Final Reflections

What surprised us most about Coca-Cola Consolidated is what it isn’t. This isn’t a high-growth tech platform or a disruptive startup. It’s a business built on trucks, warehouses, and franchise contracts whose roots go back more than a century. And yet the results—especially over the past decade—have looked an awful lot like top-tier private equity.

The meta-lesson is that “boring” businesses with monopolistic characteristics can compound. While investors chase the next software rocket ship, Coca-Cola Consolidated quietly turned the 2017 step-change into extraordinary shareholder returns. The pattern shows up in other corners of the market too: unglamorous operators, protected routes, relentless execution, and a flywheel that gets stronger with scale.

The 2015 refranchising will likely be remembered as a watershed moment. The Coca-Cola Company’s decision to step back from bottling—after decades of pushing toward more integration—created a rare opening for independent operators. Coca-Cola Consolidated was positioned to grab it because it had spent a century building credibility, capital access, and operating discipline.

The paradox of dependence is the permanent condition of this business. Coca-Cola Consolidated thrives because of The Coca-Cola Company: the brands, the marketing machine, the innovation pipeline. But it’s also constrained by that same relationship: concentrate pricing, tight rules of the road, and strategic dependence on decisions made in Atlanta. You don’t “solve” that tension. You manage it—day after day, negotiation after negotiation, year after year.

And that, in turn, says something important about American capitalism that’s easy to forget in an era of quarterly pressure and constant reinvention: patient family capital still works. The Harrison approach can look old-fashioned—conservative balance sheets, steady reinvestment, relationships treated like assets. But four generations of disciplined capital allocation and operational focus built a company that was ready when the game board shifted.

The biggest remaining question is scale: can Coca-Cola Consolidated cross $10 billion in revenue and reach truly national heft? The 2017 acquisitions proved they could operate well beyond their Carolinas roots. But going from a regional giant to something closer to national coverage would require more territory, more integration, and continued excellence in the unsexy details that actually decide whether shelves stay full.

For investors, the trade-off is as clean as it is uncomfortable. The moats are real—exclusive franchise territories, scale economies, and process power earned the hard way. The risks are real too—dependence on The Coca-Cola Company, category headwinds, and the capital intensity that keeps cash flow from ever feeling effortless.

Whether that’s attractive comes down to time horizon. If you measure performance quarter to quarter, this can look like a constrained, heavy, operational business. If you measure in decades—as the Harrison family has for 122 years—it can look like a compounding machine with a remarkably durable foundation.

After more than a century, Coca-Cola Consolidated is still running the same playbook: execute obsessively, invest through cycles, and take the long view. The next chapter is still being written. But the principles that got them here don’t appear to be changing.

XV. Further Reading & Resources

If you want to go deeper on Coca-Cola Consolidated—and on the bottling system that makes a company like this possible—these are the best places to start:

Coca-Cola Consolidated 10-K filings (SEC.gov) are the closest thing to an operating manual. They lay out the territory integration story, the mechanics of the business, and the risks in a way that quarterly updates simply don’t.

For God, Country, and Coca-Cola by Mark Pendergrast is still the definitive Coca-Cola history. If you want to understand why the franchise system exists, how it evolved, and why bottlers matter, this is the book.

The Coca-Cola Company’s 2015 refranchising announcement and related investor materials capture the strategic pivot that reshaped the entire North American bottling map—and created Coca-Cola Consolidated’s once-in-a-generation expansion opportunity.

Beverage Digest is the trade publication lens: market share, category shifts, and who’s winning which battles for shelf space and distribution.

The Outsiders by William Thorndike isn’t about beverages, but it’s a great companion read for what this story really is: disciplined, long-term capital allocation in a business that doesn’t look exciting until you follow the compounding.

Frank Harrison III interviews (BevNET and industry conferences) are the best way to hear the company’s operating philosophy in its own words—especially around culture, execution, and long-horizon decision-making.

Competitive Strategy by Michael Porter and 7 Powers by Hamilton Helmer are the frameworks behind the analysis: how industry structure shapes outcomes, and why certain advantages persist for decades.

The Coca-Cola Consolidated story is a reminder that the fundamentals still win: moats you can explain, cash you can track, and execution you can see in the real world. The flashiest trend often isn’t the best teacher. Sometimes the best lessons are sitting in a warehouse, on a route, and in a century-long time horizon.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music