Capital One: The Data-Driven Revolution in American Finance

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

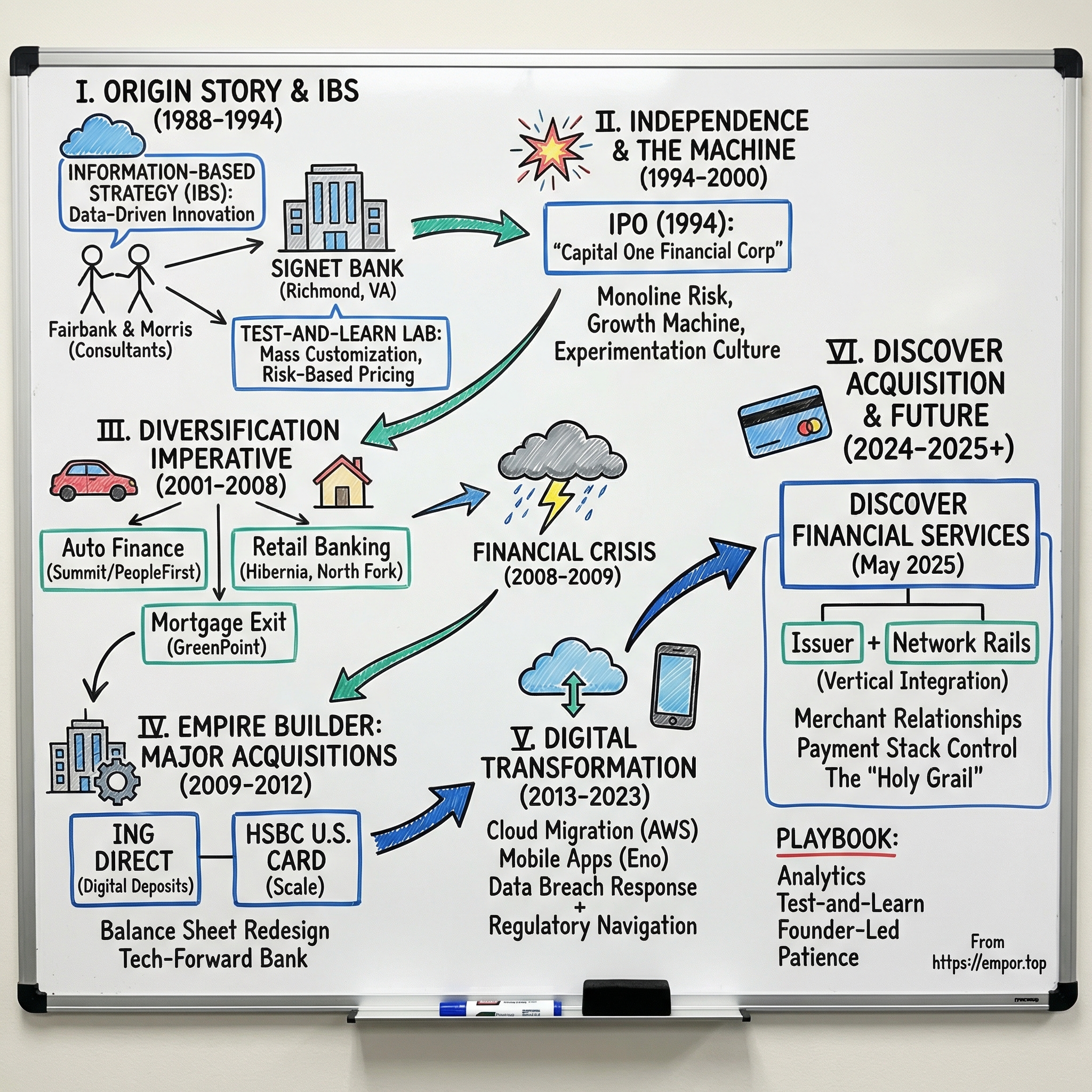

In the pantheon of American banking, Capital One holds a strange, modern kind of crown. It isn’t the oldest institution. It isn’t the biggest by assets—that title belongs to JPMorgan Chase. But over the past four decades, few companies have more aggressively rewired the assumptions of consumer finance. By September 2024, Capital One was the ninth-largest U.S. bank by total assets and the third-largest issuer of Visa and Mastercard credit cards. And when it completed its acquisition of Discover Financial Services in May 2025, it crossed into rare territory: a vertically integrated payments business that could issue cards and also own the network rails those transactions run on.

The question that powers this story sounds simple: how did two consultants use data science to reinvent the credit card business—and then build a roughly thirty-five billion dollar acquisition machine on top of it?

To answer it, you need three threads woven together. First is information-based strategy: the then-heretical idea that credit cards are less a “banking” problem than a data and decisioning problem. Second is founder-led transformation—Richard Fairbank staying in the CEO seat for more than three decades, an eternity in an industry that usually rotates leaders like clockwork. Third is empire-building through mergers and acquisitions, where Capital One didn’t just buy growth; it used deals to change what the company fundamentally was.

What follows is a story of test-and-learn innovation, regulatory battles that would’ve broken lesser institutions, and a decades-long march from a single insight about information to a company that could move money across its own network. The Discover deal, closed in May 2025, wasn’t just “another acquisition.” It was the endpoint of a vision Fairbank had been chasing since the very beginning.

II. The Origin Story: Two Consultants and a Bank

In the summer of 1988, two management consultants walked into a Richmond, Virginia bank office with a pitch that, in that era, bordered on blasphemy. Richard D. Fairbank, in his late thirties, had spent the previous decade at Strategic Planning Associates—later absorbed into Mercer—advising financial institutions on strategy. Nigel W. Morris, a British-born colleague trained in operations research, had been seeing the same thing Fairbank had: the credit card industry was sitting on a mountain of value and acting like it didn’t exist.

Credit cards in the 1980s were run with a kind of comfortable uniformity. Banks charged roughly the same interest rates—often around eighteen percent—sent out millions of identical mailers, and managed risk with relatively blunt tools like credit bureau scores and basic income checks. Portfolios were built on the hope that the good accounts would outweigh the bad. It worked well enough, which was the problem. When everyone does the same thing and makes money, nobody feels pressure to change.

Fairbank couldn’t unsee what was hiding in plain sight. A credit card wasn’t just a lending product—it was an information engine. Every purchase, every payment, every late fee produced signals about future behavior. The one-size-fits-all model wasn’t merely inefficient; it was an invitation. “In the mid-1980s,” Fairbank later reflected, “I recognized what I perceived as a missed opportunity by the credit card industry.” He was right—and that single recognition would end up reshaping consumer finance.

Fairbank and Morris turned the insight into a framework they called Information-Based Strategy, or IBS. The premise was simple, and radical for its time: stop treating customers as a pool and start treating them as individuals. If you could predict risk and value at the customer level, you could make different offers to different people—different rates, different credit lines, different introductory terms—designed to win the accounts you actually wanted. Not by guessing. By testing.

Today, that sounds like Marketing 101. In 1988, it sounded like science fiction. Personal computers were only beginning to seep into corporate life. Database tools were improving, but “big data” wasn’t even a phrase yet. Most banks viewed computing as a back-office necessity, not a weapon.

The bigger problem wasn’t the math. It was finding a bank willing to bet its reputation—and its balance sheet—on an approach no one had proven. Fairbank and Morris took the idea on the road, pitching more than twenty financial institutions. Most listened politely and passed. The big banks didn’t want to disrupt profitable card businesses. Smaller players worried the investment would be too heavy. Banking, by design, prizes caution.

Then they met Signet Bank.

Signet was a medium-sized regional bank headquartered in Richmond, with roughly four billion dollars in assets and a credit card operation that hadn’t exactly lit the world on fire. But Signet’s leadership had something rare: curiosity. They didn’t just hear “fancy analytics.” They heard “strategic edge.” If Fairbank and Morris were right, this wasn’t a product tweak—it was a way to outrun competitors who were all racing in the same lane.

So Signet did something unusual. It didn’t keep Fairbank and Morris at arm’s length as outside consultants. It brought them inside and effectively gave them room to build a startup within the bank—permission to experiment directly on the credit card portfolio, with real customers and real economics. Signet would own what they built, but Fairbank and Morris would get what they needed most: the ability to run the play for real.

At the center of that play was mass customization, a concept borrowed from manufacturing but almost unheard of in financial services. Instead of one “Signet card,” there could be thousands of variations—rates aligned to risk, introductory deals tuned to acquisition costs, balance transfer offers designed for specific segments. Each offer could be tested against a control group. The results would feed back into the next set of offers, and the next, creating a loop that got smarter with every cycle.

That loop was only possible because computing was changing. Mainframes had been around for decades, but they were mostly used to process transactions, not to learn from them. By the late 1980s, improving database technology and falling hardware costs made customer-level analysis increasingly feasible. Fairbank and Morris saw what many bankers didn’t: this was not just an efficiency upgrade. It was a strategic opening.

The partnership with Signet was the spark that would eventually become Capital One—though there was no such name yet, and no independent company. For the next six years, Fairbank and Morris would build their machine inside Signet’s walls, proving—experiment by experiment—that credit cards weren’t a commodity business at all. They were an information business. And the bank that treated them that way could win.

III. The Signet Years: Building the Machine (1988–1994)

Inside Signet, the credit card unit didn’t feel like a bank department. It felt like a lab.

Fairbank and Morris started by hiring people who didn’t look like traditional bankers—analysts trained in statistics, computer science, and operations research—and then did the most important thing: they built a system to run experiments constantly, on real customers, with real money on the line.

That “test-and-learn” approach became the operating system. Everything was up for debate. The envelope. The copy. The teaser rate. The long-term rate. Credit lines. Fees. Not as one-offs, but as controlled tests designed to produce answers, not opinions. While other card issuers judged a direct-mail campaign by response rate, Signet’s team tracked what actually mattered: customer profitability over time.

And quickly, the results came back with a clear verdict. Fairbank’s original insight held. If you could predict behavior and value at the customer level, you didn’t have to choose between growth and risk control—you could do both. Some customers who looked risky could be profitable if priced correctly. Some low-risk customers could be won with tailored offers that a one-size-fits-all competitor couldn’t match. The portfolio grew, but it grew with intent.

One of the most consequential applications was subprime lending. The phrase would become infamous later, but in the early 1990s it mostly meant “a segment traditional banks avoided.” Fairbank and Morris used their models to do something subtler than blanket expansion: they tried to find the best risks inside a population most lenders wrote off. The bet wasn’t predation. It was precision—identifying customers whose patterns suggested they’d behave better than their credit scores implied, and structuring terms that matched the real risk.

It worked. What began as an internal experiment became Signet’s most profitable line of business. The credit card operation grew from a modest contributor into the bank’s crown jewel, throwing off returns that made the rest of Signet’s businesses look sluggish by comparison.

But that success created a new problem: fit.

Signet was still, at its core, a regional bank—branches, commercial loans, trust services—the kind of institution built to move carefully. The credit card unit was becoming something else entirely: a fast-moving, technology-heavy business with its own culture and, increasingly, its own ideas about where to go next. Fairbank and Morris wanted speed, national scale, new products, and bigger technology bets. The parent bank, managing a broader franchise and a more conservative balance sheet, didn’t always want to fund that appetite.

By the early 1990s, the tension was hard to ignore. The credit card division was generating outsized profits, yet it still had to compete internally for capital and autonomy. Fairbank and Morris weren’t just asking for more budget—they were arguing that the thing they’d built could go far beyond what Signet, structurally and culturally, could support.

So the answer wasn’t to keep expanding within the bank. It was to leave it.

In a move that looks wild in hindsight, Signet agreed to spin off its star performer as an independent company. The logic, at the time, was pragmatic. A standalone business could raise capital directly, make moves without navigating a parent’s priorities, and recruit and retain talent with equity tied to the credit card operation’s true economics—not diluted inside a diversified regional bank.

Signet would crystallize value and return to being the kind of bank it knew how to run. Fairbank and Morris would get the freedom to build what they believed they’d only just started. And Wall Street was about to meet a company whose “product” wasn’t really a credit card at all.

It was a machine: data, discipline, and decisioning—ready to operate on its own.

IV. The IPO and Independence (1994–1995)

On July 21, 1994, Signet Financial Corp announced a spin-off that would end up looking like a once-in-a-generation decision in American banking. Its credit card division would be set free as a standalone company. At first, it wore a placeholder name: OakStone Financial. Fairbank would run it as CEO. Morris would be President and COO. But the “working title” phase didn’t last long. By October 1994, the new company had a real name—Capital One Financial Corporation—and a clear identity: this wasn’t a bank dabbling in cards. It was a cards company built around information.

The IPO later that year was the real point of no return. The shares were priced at sixteen dollars, and the offering valued the business at roughly two billion dollars—an eye-catching number for a company that, on paper, still had just one product. The skepticism was predictable. Could Information-Based Strategy survive outside Signet’s umbrella? Could a young, tech-heavy card issuer keep its edge once it had to fund itself, stand on its own balance sheet, and answer to public-market expectations? And was “credit card innovation” actually a big enough frontier to justify all the hype?

In February 1995, the separation became complete. Capital One stepped onto the public stage as one of the country’s top ten credit card issuers, already serving more than five million customers. That’s an astonishing transformation in just six years: a modest regional portfolio turned into a national player—one that now had to compete, quarter after quarter, against entrenched giants with far deeper histories.

But independence came with a bright warning label. Capital One was a monoline bank. In other words, essentially all of its revenue came from credit cards. That kind of concentration can work wonderfully in good times—and turn vicious in bad ones, when consumer credit deteriorates and losses rise across the entire category. Capital One didn’t have a second engine: no wealth management fees, no commercial lending franchise, no other business line to soften the blow if the card cycle turned.

Fairbank didn’t deny the risk. He reframed it. The company’s defense, he argued, wasn’t diversification for its own sake; it was precision. Because Capital One understood customers at the individual level, it could adjust underwriting, pricing, and portfolio strategy faster—and with more nuance—than traditional issuers. Diversification was a blunt instrument. Data-driven portfolio management, in this telling, was a scalpel. It was a compelling idea. It just hadn’t been tested through a full credit cycle yet.

And the market wasn’t waiting around to see. The competitive pressure started immediately. Other issuers were learning that segmentation worked. Risk-based pricing was spreading. Teaser rates—those low introductory APR offers designed to pull in balance transfers—trained customers to shop aggressively and switch quickly. Mailboxes got crowded. Response rates got harder to win. Customer acquisition costs climbed.

Capital One’s answer was the thing it had built inside Signet: experimentation as a reflex. When a channel saturated, the company tested its way into another. When a competitor’s offer started to bite, Capital One didn’t need a months-long committee process—it could learn and respond quickly, because the infrastructure for learning was the business.

Inside the company, another question ran in parallel: what, exactly, was Capital One? A bank with strong analytics? Or a technology company that happened to operate under bank rules? Fairbank pushed deliberately toward the second identity. Technical talent held unusual influence for a financial institution. Engineers and data scientists weren’t support staff; they were part of the core. Even the culture in Richmond signaled something different—less traditional banking establishment, more builder mentality.

By the end of 1995, Capital One had done the first, essential thing: it had proven it could stand on its own. The company was public, growing, and increasingly confident that IBS wasn’t a clever trick—it was a system that scaled. The monoline risk still hung over the story, and a real downturn still waited somewhere in the future. But the machine had made it out of the lab. Now it had a stock ticker—and a mandate to keep winning.

V. The Growth Machine: Innovation and Expansion (1996–2000)

By the late 1990s, Capital One was no longer just the clever spin-off with a novel idea. It was starting to bend the industry around it.

The first big tell came in 1996, when Capital One made a clean break from the playbook that had dominated card marketing for years. Teaser rates had worked—until everyone copied them. When the mailbox filled up with the same “low intro APR” pitch from every issuer, the edge disappeared. Capital One responded the way it always did: it treated the problem as an experiment, not a panic. It shifted from relying on teaser rates to rolling out a broader set of products and offers engineered for specific customer segments.

What followed was variety with a purpose. Capital One introduced co-branded cards, secured cards, and joint account products—each aimed at a particular behavior pattern or need its models could identify. Co-branded partnerships with retailers and affinity organizations gave the company new ways to acquire customers. Secured cards, backed by deposits, let Capital One go deeper into subprime while limiting losses. Joint accounts leaned into household dynamics that most issuers weren’t really designing for.

That same year brought a quieter move with huge strategic implications: federal approval to set up Capital One FSB, a federal savings bank subsidiary. It wasn’t just a regulatory trophy. It meant Capital One could retain and lend out deposits tied to secured cards, and it could issue automobile installment loans. Just as importantly, it gave the company access to a steadier, potentially cheaper funding base than the securitization markets it had leaned on before. It also hinted at something bigger: the first real step away from being a pure credit-card story.

Capital One also started pushing beyond U.S. borders in 1996, expanding into the United Kingdom and Canada. The logic was straightforward. The UK card market lagged the U.S. in analytical sophistication, which created room for a data-driven entrant to compete differently. Canada offered geographic diversification in a market with familiar consumer credit dynamics.

The scale-up during this period was hard to ignore. A Chief Executive article in 1997 reported that Capital One held about $12.6 billion in credit card receivables and served more than nine million customers—nearly double the customer base it had at the spin-off just a couple of years earlier. Along the way, Capital One landed in the Standard & Poor’s 500. In 1998, the stock hit $100 for the first time, a striking leap from the IPO price.

Then came another signal that Capital One wasn’t content to just win at cards. In July 1998, it acquired Summit Acceptance Corporation, moving decisively into auto finance. Auto loans fit the same mental model that had made Capital One dangerous in credit cards: consumer credit, lots of historical data, and a business that could be improved through risk-based pricing and disciplined marketing. Summit brought a platform and domain expertise; Capital One brought the analytics and the test-and-learn engine.

By 2000, Capital One made the Fortune 500—an almost absurd milestone for a company that hadn’t existed as an independent business six years earlier. The broader industry was finally getting the message: data-driven finance wasn’t a gimmick. It was the future. Competitors scrambled to build their own capabilities, but Capital One’s head start—plus a culture built around experimentation—wasn’t easy to replicate.

But success was also surfacing the company’s structural constraint. Even with smarter models and more product variations, credit cards were still credit cards: one category, exposed to the same consumer cycle risk. Auto finance helped, but it wasn’t a true hedge. In a recession, consumers struggle with both cards and car payments.

So even as the growth machine roared, Fairbank and his team were already staring at the next problem: how to diversify in a way that didn’t dilute the very analytical edge that got them here. The answer would take shape in the decade ahead—and it would pull Capital One closer to becoming a “real bank,” whether it liked the label or not.

VI. Beyond Credit Cards: The Diversification Imperative (2001–2008)

By the turn of the millennium, Fairbank was staring at a problem that came with the company’s success. Capital One had built a formidable machine—but it was still, fundamentally, a credit card machine. And if the credit cycle turned, there was nowhere to hide.

So even before the dot-com era had fully cooled, he started talking about pushing the Information-Based Strategy beyond cards. In 1999, Fairbank announced moves to use Capital One’s experience collecting consumer data to offer other products—loans, insurance, even phone service. Telecommunications was the boldest stretch: a bet that the same test-and-learn discipline that could profitably acquire and manage cardholders might work in any business with similar customer economics.

That phone-service idea didn’t become the next act of the company. But it was revealing. Capital One wasn’t defining itself by a product. It was defining itself by a method—and Fairbank was willing to pressure-test that method far outside traditional banking.

The more consequential diversification, though, stayed closer to home: becoming a broader consumer lender and, eventually, a true deposit-taking retail bank.

That shift began to take shape through acquisitions. In October 2001, Capital One acquired PeopleFirst Finance LLC. Two years later, in 2003, the combined operation was rebranded as Capital One Auto Finance Corporation. It wasn’t just a name change. It was the company committing to auto lending as a scaled platform—and proving something important along the way: Capital One’s analytics could improve businesses it bought, not just businesses it built.

Then came the deal that signaled a deeper identity change. In 2005, Capital One acquired Hibernia National Bank, a traditional retail bank with branches concentrated in Louisiana and Texas. On paper, it looked like the opposite of Capital One’s original, technology-first, branch-light model. But strategically, it was exactly what Capital One needed: a meaningful deposit base and a real foothold in retail banking, reducing reliance on credit cards and auto loans.

The timing, though, was immediately brutal. Hurricane Katrina struck the Gulf Coast just months after the acquisition closed, devastating Hibernia’s Louisiana footprint. Capital One kept branches operating, supported customers through the disruption, and rebuilt damaged facilities while still trying to integrate a large, newly acquired bank. The work was messy and expensive—but it also made something clear: Capital One wasn’t going to dabble in these acquisitions. It was going to own them.

If Hibernia was the pivot, North Fork was the acceleration. In 2006, Capital One acquired North Fork Bank in a $13.2 billion cash-and-stock deal, gaining a substantial branch network in the New York metropolitan area—one of the most competitive and valuable banking markets in the country. With Hibernia and North Fork, the monoline risk that had hovered over Capital One since the IPO finally began to fade. Deposits and retail banking income were now real parts of the story.

Not every diversification move aged well. Included in the North Fork deal was GreenPoint Mortgage, a wholesale mortgage lender—exactly the kind of exposure that would become toxic as the housing bubble approached its peak. By 2007, with subprime mortgage defaults starting their steep climb, Capital One chose to shut GreenPoint down entirely. The decision came with substantial losses, but it also prevented the kind of slow-motion catastrophe that consumed institutions that stayed in mortgages too long, hoping the market would bail them out.

That willingness to admit error and cut losses—fast—was a defining Fairbank trait. In a period when many financial firms doubled down on failing positions, Capital One took the pain and moved on.

And then there was the strange little episode that showed just how operationally specific Capital One’s strategy could be. In late 2002, Capital One and the U.S. Postal Service proposed a negotiated services agreement for bulk mailing discounts. It sounds mundane—until you remember that direct mail was still a major acquisition engine for the company. The agreement ran for three years and was extended in 2006. But in June 2008, Capital One filed a complaint with the USPS about the terms of the next agreement, pointing to the negotiated terms a competitor, Bank of America, had secured. Capital One ultimately withdrew the complaint after a settlement. Even postage, it turned out, could be strategic when your growth machine ran on envelopes.

Then the world broke.

The financial crisis of 2008 and 2009 stress-tested everything about Capital One: its underwriting, its funding, and the bet that diversification could protect a company born in credit cards. Consumer credit losses surged as unemployment rose and housing values collapsed. Like most major financial institutions, Capital One accepted TARP funding under the government’s Troubled Asset Relief Program, and repaid it as conditions stabilized.

The crisis didn’t make Capital One invincible—but it clarified the value of the moves Fairbank had made earlier in the decade. Retail deposits provided a more stable funding base. The retreat from mortgages avoided a deeper blowup. And when the dust began to settle, Capital One emerged bruised but standing—positioned, oddly enough, for the next phase of its story: using the balance sheet and bank charter it had assembled to go buy its way into a new tier of American finance.

VII. The Empire Builder: Major Acquisitions Era (2009–2012)

From 2009 to 2012, Capital One didn’t just keep diversifying. It went shopping in a way that permanently changed the company’s weight class. The financial crisis had shattered confidence across the industry, but it also created openings—especially for institutions that still had the capital, the nerve, and the strategic clarity to act.

The first move came quickly. In February 2009, Capital One acquired Chevy Chase Bank for about five hundred twenty million dollars in cash and stock. Chevy Chase was a Washington, D.C.-area regional bank, and the appeal was straightforward: branches and deposits in one of the wealthiest metro areas in the country. This wasn’t a flashy “buy a wreck and rebuild it” crisis deal. It was Capital One sharpening a newer acquisition instinct—add strong franchises in attractive markets, and let deposits do the quiet compounding work.

But Chevy Chase was the warm-up.

In June 2011, Capital One announced the acquisition that would define this era: ING Direct USA. The headline number was nine billion dollars, and the impact was immediate. Measured by deposits, Capital One jumped from the eighth-largest U.S. bank to the fifth—leaping past U.S. Bancorp and landing just below Citigroup. It was the kind of move that makes competitors stop and re-rate you overnight.

ING Direct had built something rare in American banking: a massive deposit franchise without a single branch. Its Orange Savings Account and clean, simple digital experience had attracted millions of customers who didn’t want a relationship manager—they wanted convenience, clarity, and decent rates. For Capital One, those deposits weren’t just “nice to have.” They were strategic fuel: stable, relatively low-cost funding that fit perfectly with the company’s technology-forward identity.

When the deal closed, the final terms were different from the original headline. Capital One paid six point three billion dollars in cash and issued about fifty-four million shares to ING Groep, giving ING roughly a nine point seven percent ownership stake. With ING Direct’s deposits added to the balance sheet, Capital One became the sixth-largest depository institution and the leading direct bank in the United States.

Getting there, though, was anything but automatic. Regulators scrutinized the deal heavily, with public hearings and close review by the Federal Reserve, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, and state authorities. Community groups pressed concerns about Capital One’s credit card lending practices and questioned how the combined institution would serve lower-income communities. Capital One responded with commitments to community investment programs and changes to certain practices to satisfy concerns and keep the approval process moving.

In February 2012, regulators approved the transaction and Capital One completed the acquisition. In October 2012, it received permission to merge ING into its banking operations. A month later, in November, the orange brand disappeared: ING Direct became Capital One 360. The message was clear—this wasn’t a side business. Direct banking was now a core pillar.

At the same time, Capital One was making another enormous bet—one that got less consumer attention, but mattered just as much strategically. In August 2011, Capital One agreed to acquire HSBC’s U.S. credit card operations. The price: thirty-one point three billion dollars, in exchange for twenty-eight point two billion dollars in loans plus six hundred million dollars in other assets. The deal closed in May 2012.

The HSBC portfolio brought meaningful scale in premium cards, a segment where Capital One had historically lagged competitors like American Express and Chase. But the deeper logic tied directly back to ING Direct. With a much larger deposit base, Capital One could fund credit card growth through retail deposits instead of leaning so heavily on securitization markets. In banking, funding isn’t a footnote—it’s the game. And this pairing of deals was, in effect, a balance-sheet redesign.

Of course, buying two huge businesses at once comes with a predictable downside: integration pain. Technology systems had to be harmonized. Customer service operations consolidated. Risk frameworks unified. Capital One leaned on what it knew—analytics and discipline—using models to guide branch decisions, product migrations, and key retention calls. But even with a data-driven playbook, the operational load was enormous.

By the end of 2012, the company that had gone public as a credit card monoline had become something else: a diversified institution with deposit-funded banking, auto lending, commercial banking operations, and a scaled card franchise that could grow on a cheaper, steadier funding base. The transformation Fairbank had been reaching for since the late 1990s was largely in place.

Now Capital One had to do the harder part: prove that all these pieces could run as one machine.

VIII. Digital Transformation & Modern Era (2013–2023)

After the acquisition spree, Capital One had a different problem to solve. It wasn’t about buying the next platform anymore. It was about operating everything it had bought as one coherent machine—while the ground under banking was shifting from branches and call centers to apps, APIs, and cloud infrastructure.

Capital One’s response was faithful to its origin story. It didn’t treat technology as plumbing. It leaned harder into the idea that it was a technology company with a banking charter.

The clearest example was cloud computing. Capital One moved earlier—and more aggressively—than any other major bank, migrating large parts of its systems to Amazon Web Services. That choice wasn’t universally popular. Many competitors were still debating whether public cloud was safe enough for sensitive financial data, and regulators and examiners had limited experience evaluating cloud-based architectures. But Capital One pushed forward anyway, arguing that with the right controls, cloud could be more secure and more resilient than the status quo.

In 2018, the company put a physical stamp on that identity by opening a new headquarters in McLean, Virginia. It was designed to reflect the culture Fairbank had been building for decades: engineers, designers, and data scientists working alongside business teams, not in a separate “IT” wing. The building wasn’t the strategy, of course, but it symbolized one—software wasn’t support. It was core.

On the customer side, the shift to mobile only accelerated as smartphones became the default interface for money. Capital One’s apps became some of the highest-rated in banking, with features that reflected the same test-and-learn mindset that had once been applied to direct mail. Eno, the company’s text-based virtual assistant, was an early bet on conversational AI for customer service—something that would later become table stakes across the industry. And account opening was compressed into minutes, drawing directly from the simple, fast direct-banking experience Capital One had inherited from ING Direct.

Then came the moment that threatened to undercut the entire “tech-forward bank” narrative.

On July 29, 2019, Capital One disclosed that it had discovered unauthorized access to customer data ten days earlier. A former Amazon Web Services employee had exploited a misconfigured firewall and accessed information affecting 106 million people in the United States and Canada. The breach included about 140,000 Social Security numbers, roughly one million Canadian social insurance numbers, and 80,000 bank account numbers.

It was a full-spectrum stress test: of Capital One’s security practices, its credibility as a cloud pioneer, and its ability to respond under a national spotlight. The company moved to be transparent about what happened and what data was exposed, offered free credit monitoring, and poured more resources into security. Fines and litigation piled up into the hundreds of millions of dollars. And internally, the breach forced a sweeping reassessment of cloud security practices that, while costly and painful, ultimately hardened the company’s posture.

That recovery unfolded amid constant regulatory pressure that comes with scale. Consumer protection scrutiny remained intense, with attention on credit card practices, overdraft fees, and lending patterns. Capital One adjusted products and disclosures as needed, but the underlying model stayed the same: analytical customer selection, disciplined pricing, and a willingness to redesign processes when regulators—or customers—made clear something wasn’t working.

In 2017, Capital One also made a quieter but telling strategic decision: it exited mortgage lending. Even after the earlier GreenPoint experience, the company had kept a modest mortgage operation. Leaving the business was an acknowledgment that diversification wasn’t the goal by itself. Mortgages were fiercely competitive, operationally heavy, and offered less of the kind of data-driven acquisition advantage that had made Capital One exceptional elsewhere.

Then the pandemic hit, and the industry’s slow drift toward digital suddenly turned into a sprint. Capital One’s infrastructure absorbed the surge in online transactions, and the company offered payment deferrals to affected customers while maintaining underwriting discipline that helped limit credit losses relative to pre-crisis projections. By 2023, the behavioral shift looked durable: more customers were managing their entire financial lives through a screen, and fewer wanted banking to require a building.

And through all of it, one unresolved strategic gap remained. Capital One was still, in a critical sense, renting the most important piece of the payments stack. It issued cards on networks owned by Visa and Mastercard—living within rules and economics set by someone else.

Fairbank had talked for years about what he saw as the Holy Grail: being an issuer that also owned the network rails. That idea never went away. It just waited for the right moment—and the right target—to finally become real.

IX. The Discover Acquisition: The Ultimate Power Play (2024–2025)

On February 19, 2024, Richard Fairbank unveiled the deal he’d been chasing, in one form or another, for most of his career. Capital One announced an agreement to acquire Discover Financial Services in an all-stock transaction valued at about thirty-five billion dollars. Under the terms, Discover shareholders would receive 1.0192 Capital One shares for each Discover share, a premium of 26.6 percent based on Discover’s closing price of $110.49 on February 16, 2024.

The headlines, naturally, fixated on the sheer size of the merger and the idea of combining two major credit card issuers. But that wasn’t the real story. The story was the thing Discover owned that almost nobody owns: a payments network.

In the United States, there are only four major payment networks: Visa, Mastercard, American Express, and Discover. And it’s Discover’s network—the rails that route transactions between consumers and merchants, taking a toll along the way—that made this deal different. Capital One wasn’t just buying a book of cardholders. It was buying control of the infrastructure beneath the cards.

Fairbank said the quiet part out loud. “That network is a very, very rare asset,” he explained when announcing the transaction. “We have always had a belief that the Holy Grail is to be able to be an issuer with one’s own network so that one can deal directly with merchants.” He framed it as the payoff of a founding vision: since the late 1980s, he said, he’d imagined Capital One becoming a global digital payments technology company by owning the rails and dealing directly with merchants.

The logic clicked into place the moment you looked at how the industry normally works. As a large issuer on Visa and Mastercard, Capital One played inside someone else’s rulebook and someone else’s economics. Discover offered a way out. With its own network, Capital One could issue cards on its own rails, capture network economics, and create merchant relationships that typical Visa and Mastercard issuers simply couldn’t replicate. And paired with the scale Capital One had built over decades—supercharged by the ING Direct deposit machine and the HSBC card portfolio—Discover’s network turned that scale into something structurally new.

But the strategic appeal didn’t make the deal easy. The regulatory path was brutal. By 2024, big bank mergers were under intense scrutiny, and consolidation in financial services had become a political lightning rod. Community groups mobilized, raising concerns about competition and what the combined company would mean for community lending. Public meetings pulled in comments from across the spectrum, and every part of the deal was examined.

Capital One responded with patience—and with commitments designed to meet the moment. It announced a community benefits plan committing more than $265 billion in lending, investment, and philanthropy over five years. The plan was developed in partnership with the National Association for Latino Community Asset Builders, NeighborWorks America, the Opportunity Finance Network, and the Woodstock Institute.

Approvals came in steps. The Delaware State Bank Commissioner approved the proposed acquisition on December 18, 2024. Then shareholders weighed in: in early 2025, the votes at both companies cleared more than 99 percent approval, an unusually strong mandate for a transaction of this size and complexity. That left the final hurdle: federal regulators.

Then, after months of waiting, the Federal Reserve and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency approved the $35.3 billion all-stock deal. The approval came with conditions tied to community commitments and competitive practices, but the practical message was simple: the finish line was finally in sight.

Capital One completed the Discover acquisition on May 18, 2025. With that close, the company stepped into a new category of American finance. It could issue credit cards and also own the network those transactions ran on—putting it in a position to deal directly with merchants in ways that most Visa and Mastercard issuers never can.

The hard part, of course, didn’t disappear. Discover’s network technology wasn’t the same as Visa and Mastercard systems. Merchant relationships had to be managed through the transition. The regulatory commitments had to be implemented, not just announced. But this is what Fairbank had built Capital One to do: run complex integrations, absorb new capabilities, and turn them into an operating advantage. The Discover deal wasn’t just another acquisition. It was a culmination—an endpoint for a strategy that began with two consultants asking a simple question: what if a credit card company owned the information, the decisioning, and now, finally, the rails?

X. Playbook: The Capital One Method

Capital One’s rise—from a consulting insight inside a regional bank to a vertically integrated payments player—didn’t happen by accident. It happened because the company ran a repeatable playbook for decades. Not a slogan. A method. And in an industry where most competitors were optimizing within the same old constraints, Capital One kept changing the constraints.

The foundation was Information-Based Strategy. The original idea was almost offensively simple: credit cards aren’t primarily a banking problem, they’re a data problem. If you can understand customers better—risk, behavior, value—you can price, underwrite, and serve them better. Over time, that premise spread far beyond card marketing. It showed up in how Capital One managed consumer lending more broadly, how it handled customer service, how it fought fraud, and how it built teams. Most banks eventually adopted “analytics.” Capital One built its identity around it early, before it was fashionable, and that head start compounded.

Then there was test-and-learn at scale—the mechanism that made IBS real. Plenty of companies say they’re data-driven. Far fewer build the operational muscle to run constant controlled experiments without bogging down in politics or fear. Capital One did, and it treated that capability like a production system: clear accountability for test design, disciplined measurement, and a culture that could tolerate the truth. Most tests don’t win. The point is to learn quickly and keep going. That comfort with productive failure—failing in small, measured ways to avoid failing in big, catastrophic ones—let Capital One explore paths that more cautious institutions wouldn’t touch.

Next: M&A as transformation. Capital One didn’t use acquisitions just to add customers or get bigger for the sake of being bigger. The major deals were strategic moves that changed what the company could be. ING Direct wasn’t merely a deposit base; it was a direct-to-consumer distribution model and a funding engine that fit Capital One’s tech-forward posture. HSBC’s U.S. card portfolio wasn’t just receivables; it was scale and reach in segments Capital One wanted to deepen. Discover wasn’t simply another issuer; it was the network rails. In each case, Capital One applied the same analytic rigor it used in marketing and underwriting: evaluate the target, plan the integration, then reshape the asset to fit the operating system.

That operating system had an unusual advantage: founder-led continuity. Fairbank’s decades-long tenure as CEO is almost unheard of in American finance, where leadership often changes before strategies have time to mature. That stability allowed Capital One to play long games—especially the biggest one of all, network ownership—without getting whipsawed by shifting executive agendas. Instead of institutional knowledge walking out the door every few years, it accumulated.

Technology as differentiator was the through-line. From the beginning, Capital One treated software and analytics as core, not as a back-office function. The company made organizational and capital decisions that reflected that belief: building real engineering capacity, committing early to cloud infrastructure, and designing its headquarters and culture to keep technologists close to the business. When asked whether it was a tech company or a bank, Capital One’s answer was effectively: both—and we’re not apologizing for the tension.

Regulatory navigation was the necessary counterpart to ambition. In finance, regulation is both constraint and moat. Capital One’s path forced it to get good at working under scrutiny: major acquisitions, the aftermath of a significant data breach, and the intense review of the Discover transaction. Over time, that turned into a capability of its own—a learned ability to survive public hearings, satisfy supervisory demands, and keep the strategy intact. The community benefits plan tied to the Discover acquisition captured that mindset: regulatory requirements weren’t treated as a box to check, but as commitments the company could operationalize.

And finally, the power of patience. Capital One’s most consequential strategy—the idea that the “Holy Grail” was owning the network rails—took decades to become feasible. In an industry optimized for quarters and annual bonus cycles, Capital One repeatedly acted as if time was an asset. The Discover deal made that explicit: a vision rooted in the company’s earliest days, executed only when the right target and the right conditions finally aligned.

XI. Power Analysis & Competitive Dynamics

To understand Capital One’s competitive position, it helps to stop thinking like a bank analyst for a second and start thinking like a strategist. What actually compounds here? What gets better as the company gets bigger? And after Discover, what new advantages did Capital One buy into existence?

Start with the most “Capital One” advantage of all: scale in data and technology. Building great underwriting models, fraud systems, personalization engines, and digital experiences takes enormous upfront investment. But once you’ve built them, the cost doesn’t rise in proportion to volume. The more customers and transactions you run through the same core platforms, the more you spread those fixed costs—and the more training data you generate to make those models even better. After the Discover acquisition, Capital One’s scale creates an edge that’s hard for smaller competitors to replicate: every incremental account and swipe can improve decisioning, which can improve economics, which can fund more investment. It’s a flywheel.

Discover also adds something Capital One didn’t truly have before: network dynamics. Payment networks run on two-sided network effects. Merchants accept a network because consumers show up with those cards. Consumers carry cards because they know merchants will take them. Discover’s network is smaller than Visa or Mastercard, but it’s a real network with real rails—and now it’s a platform Capital One can develop. More merchant relationships, better incentives, and, over time, the ability to route more of Capital One’s own card volume over Discover’s infrastructure. The strategic prize isn’t simply “more cards.” It’s shifting transactions onto rails the company owns.

Then there’s stickiness—switching costs and retention. Credit cards are deceptively hard to replace once they’re in your life. The card number gets wired into subscriptions and automatic payments. Rewards balances accumulate. Your credit history ties to that account. Capital One has long used its data advantage to manage churn with targeted retention offers, while also recognizing when a customer is likely to leave no matter what. Add in the ING Direct deposit base—savings accounts that sit alongside card relationships—and you get a deeper, more durable customer connection than a standalone card issuer typically enjoys.

Regulation is the other, often underestimated, part of the moat. Since 2008, banking has become more compliance-intensive, more capital-constrained, and more tightly supervised. That burden is real—but it also raises the drawbridge. New entrants don’t just need a clever product; they need the balance sheet, risk management, and regulatory relationships to operate at scale. Capital One’s history of navigating scrutiny—culminating in the extensive approval process for Discover—creates institutional muscle that doesn’t show up on a product comparison chart, but matters when the stakes are high.

None of this means Capital One gets to coast. Competitive threats are still formidable. JPMorgan Chase runs the largest credit card portfolio in the United States, and its technology capabilities often match or exceed Capital One’s. Fintech continues to chip away at profitable slices of the market, from buy-now-pay-later players like Affirm to neobanks that pursue narrow, high-growth niches. And Big Tech remains a long-term uncertainty—especially Apple, which has already proven it can insert itself into both payments and consumer finance through its card and payment services.

And then there are the wildcards: structural shifts in the payments stack itself. Central bank digital currencies, if ever implemented, could reshape how value moves. Real-time payment systems, including the Federal Reserve’s FedNow service, create alternative infrastructure that could route around card networks for certain use cases. Embedded finance—the integration of financial services into non-financial apps—could shift power toward the platforms that own distribution, not the institutions that manufacture the product.

So if you’re trying to track whether Capital One’s post-Discover advantage is real and compounding, two indicators matter more than almost anything else. First: whether credit card purchase volume is increasingly flowing over the Discover network. That’s the tell on the acquisition’s core rationale—transactions on Capital One-owned rails. Second: the net charge-off rate across the combined card portfolios. That’s the scoreboard for the company’s claim that analytics remains a durable edge, even in a world where everyone now calls themselves “data-driven.”

XII. Bear vs. Bull Case

The Bull Case

The Discover network creates strategic optionality that’s hard to overstate. Capital One now has something most major U.S. banks don’t: the ability to both issue cards and own the network those cards can run on. That vertical integration opens doors that simply don’t exist when you’re a guest on Visa and Mastercard—direct merchant relationships, access to network-level data, and more flexibility in how economics get shared across the system. Even the merchant acquiring opportunity—helping businesses accept payments—becomes a plausible new growth lane, one that wasn’t really on the table for Capital One before.

Technology leadership gives Capital One a durable edge as banking keeps moving onto screens. Years of investment in cloud infrastructure, mobile apps, and AI capabilities show up in the customer experience—and in an industry where products often look the same, experience matters. The direct banking model it picked up with ING Direct fits how many consumers now prefer to bank, while the branch footprint from its retail acquisitions still serves customers who want physical access.

Then there’s execution. Discover is a massive integration, but Capital One has done big, complicated integrations before. It has absorbed major acquisitions, built internal playbooks, and accumulated scar tissue and muscle memory. That doesn’t guarantee success, but it lowers the odds that the company is learning core integration lessons for the first time in public.

Finally, there’s a world where the regulatory environment shifts in Capital One’s favor. If policymakers push harder for more competition in payments—seeking alternatives to the Visa-Mastercard duopoly—Discover becomes a particularly valuable asset to own and invest behind. And the community benefits plan, with its commitments to lending and investment programs, is aligned with the policy priorities that often shape how regulators think about bank scale.

The Bear Case

The biggest risk is that Discover is not “just another acquisition.” Integrating a payments network is fundamentally different from integrating a deposit base or a loan portfolio. Network technology is its own beast. Merchant relationships require capabilities that look more like enterprise sales and servicing than consumer marketing. And large cultural integrations are rarely clean. Financial services history is full of mergers that looked great on strategy slides and painful in execution.

Even after closing, regulatory scrutiny doesn’t go away—it compounds. Conditions tied to approval bring ongoing compliance and reporting requirements. Consumer financial protection remains a hot-button issue, and any future missteps are likely to be judged more harshly now that Capital One is larger and more systemically important.

Then there’s the credit cycle. Capital One is still heavily exposed to consumer lending. In a downturn, losses tend to rise together across credit cards, auto lending, and other consumer products. Better analytics can mean fewer mistakes and faster adjustments, but it can’t repeal the business cycle. And with elevated interest rates and consumers carrying meaningful debt burdens, the near-term backdrop adds uncertainty.

Competitive disruption is another pressure point. Fintechs and Big Tech don’t have to replace a whole bank to do damage—they can siphon off profitable use cases. Buy-now-pay-later has already diverted transactions that might have landed on credit cards. Apple’s payment services and broader ecosystem can reshape consumer behavior in ways that leave traditional issuers fighting for relevance. Embedded finance, meanwhile, can move advantage toward the platforms that own distribution, turning banks into suppliers rather than brands.

And despite all the diversification, concentration risk hasn’t vanished. Credit cards and related consumer lending still drive a large share of Capital One’s profitability. Retail banking, in many ways, exists to provide lower-cost funding for the card business. If consumer behavior or regulation structurally shifts away from revolving credit economics, Capital One would likely feel it more than more diversified banks.

Put through classic strategy lenses, the picture is mixed. Porter would highlight intense rivalry in consumer payments, real substitutes emerging across the payments stack, and meaningful buyer power among the largest merchants negotiating rates. Hamilton Helmer’s Seven Powers suggests Capital One’s best shots at durability are scale economies, the network effects it now gets through Discover, and process power—its Information-Based Strategy discipline—that keeps turning data into better decisions over time.

XIII. Epilogue: The Future of American Payments

Richard Fairbank’s arc—from management consultant to the architect of a payments empire—maps neatly onto the rise of data-driven finance itself. The thing he and Nigel Morris began building inside Signet in 1988 wasn’t, at its core, a “better credit card.” It was a better way to make decisions. Decades later, with Discover folded into the company, that method has been wrapped around something even rarer: a vertically integrated payments business that can issue cards, own the network, and deal directly with merchants along the chain.

That’s why the Discover acquisition matters beyond Capital One’s own earnings power. It hints at a reordering of American payments around institutions that combine scale, technology, and vertical integration. The question now is whether anyone else can assemble a comparable stack—through acquisition, partnerships, or building it the hard way—or whether Capital One has carved out a position that’s unusually difficult to copy.

The next decade will be defined by a few make-or-break questions. Can Capital One move meaningful card volume onto the Discover network without breaking customer habits, confusing merchants, or sparking a war with Visa and Mastercard? Will regulators continue to tolerate this kind of vertical integration in payments, or does the political mood swing toward forcing the ecosystem back apart? And can Capital One keep its technology edge as every major bank spends aggressively, and as the competition for engineering and data talent gets even more intense?

Zoom out, and the story leaves a playbook that travels well beyond banking. Information-Based Strategy proved that an industry built on tradition could be disrupted by treating the business as a data problem. Test-and-learn showed that experimentation isn’t a buzzword—it’s an organizational capability that compounds over time. And the long pursuit of network ownership is a reminder that the biggest strategic prizes often take the longest to become available, especially in regulated industries where patience can be as important as brilliance.

Which brings us back to the question that’s been hanging over Capital One for years: is it a bank, a tech company, or something else entirely? After Discover, the cleanest answer may be that it’s a payments institution—built on technology and data, operating under a banking charter that gives it funding and regulatory access, and now owning infrastructure that most banks only rent. If Capital One executes, that hybrid model may end up looking less like an anomaly—and more like a preview of where consumer finance is headed.

XIV. Recent News

The first quarter after the Discover deal closed in May 2025 set the tone for what comes next: less about splashy announcements, more about integration. On earnings calls, management focused on the practical question at the heart of the acquisition—when, and how, Capital One will begin moving card volume onto Discover’s network. The message has been that this is a staged transition, with early pilots expected through 2025 and a broader rollout unfolding over the following years.

On the merchant side, Capital One moved quickly to strengthen the part of the business that makes a network valuable in the first place: acceptance. Merchant acquisition efforts accelerated as the company worked to expand where Discover can be used, especially in segments where Discover historically trailed Visa and Mastercard. To do that, Capital One announced partnerships with payment processors and point-of-sale providers aimed at increasing merchant coverage.

Regulatory scrutiny, meanwhile, shifted from “should this merger happen?” to “are the promises being kept?” Monitoring has continued as Capital One began implementing the community benefits plan tied to approval. Progress reporting has tracked lending in designated communities, investment in community development financial institutions, and philanthropic contributions to the organizations referenced in the approval conditions.

Wall Street’s early read has been fairly consistent: near-term execution risk, long-term strategic upside if the integration is done well. That tension has shown up in the stock’s trading, which has moved around in a way that suggests the market is still pricing in a wide range of outcomes.

XV. Sources & Resources

Company Filings - Capital One Financial Corporation Annual Reports (Form 10-K) - Capital One Financial Corporation Quarterly Reports (Form 10-Q) - Discover Financial Services merger proxy statement (Form S-4) - Federal Reserve approval documents for the ING Direct, HSBC, and Discover acquisitions - Office of the Comptroller of the Currency regulatory approval letters

Regulatory Documents - Federal Reserve Board public meeting transcripts related to the Discover acquisition - Community Benefits Plan filed with regulators (2024) - TARP repayment documentation (2009)

Historical Sources - Capital One S-1 registration statement (1994) - Signet Financial Corp spin-off documentation - Strategic Planning Associates background materials

Industry Research - Nilson Report coverage and statistics on the credit card industry - Federal Reserve Payments Study - FDIC deposit and institution data

Academic Analysis - Harvard Business School cases on Capital One and Information-Based Strategy - Academic papers on credit card economics and risk-based pricing

Long-Form Coverage - The Information-Based Strategy: Richard Fairbank and the Founding of Capital One (corporate history materials) - Chief Executive magazine profile (1997) - Reporting on the 2019 data breach and the subsequent regulatory response

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music