CNX Resources: From Coal Giant to Natural Gas Pure-Play

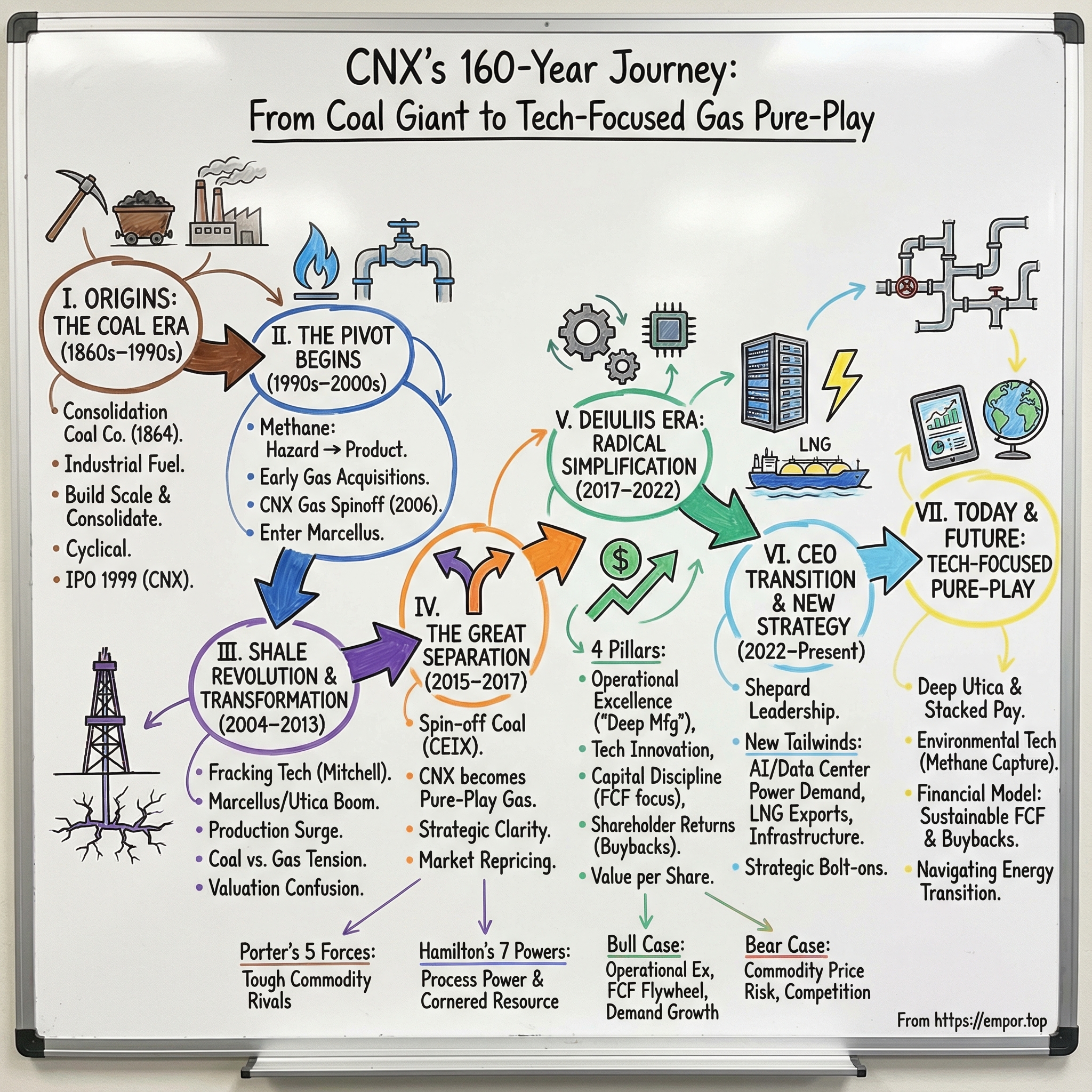

I. Introduction: The 160-Year Transformation

Picture southwestern Pennsylvania in the early morning mist: rolling Appalachian hills, the skeletal frames of old coal tipples now quiet, and—just down the road—modern natural gas compressor stations humming around the clock. In one landscape, you can see two energy eras overlapping. And inside that overlap sits one of the most dramatic reinventions in American industry: a company born in the coal fields of the Civil War era remaking itself into a natural gas operator that talks like a technology business.

CNX Resources began as Consolidation Coal Company, founded in 1860. Today, CNX is a pure-play Appalachian natural gas producer with 8.54 trillion cubic feet equivalent of proved natural gas reserves as of December 31, 2024. Its market capitalization is roughly $5.5 billion—big enough to matter, small enough to still surprise, and closely watched by investors looking for tells about where U.S. energy is headed next.

The question driving this story is simple, but the answer isn’t: How does a 160-year-old coal company pull off a full identity change—operationally, financially, and culturally—into a technology-focused natural gas enterprise? And if you’re looking at this through an investor lens, there’s a second layer: what does that transformation say about CNX’s competitive position, its management philosophy, and the way it tries to create value in a brutally commoditized business?

The timing matters. Natural gas is being pulled in multiple directions at once: LNG exports are reshaping global supply chains, manufacturing reshoring is rebuilding domestic industrial demand, and the AI data center boom is putting a spotlight on the need for reliable, always-on power. As one observer put it: "On top of LNG demand, the likely rapid North American construction of data centers—which are voracious consumers of energy—and the electrification that they need promise a substantial boost in both natural gas demand and the infrastructure that serves it. Estimates vary for how much and when natural gas demand will pick up from LNG liquefaction facilities and for AI-driven data centers. But medium-term demand from both will likely dwarf that of other types of users."

Appalachian gas sits right at the center of those crosscurrents. And CNX—with its reputation for discipline, simplification, and doing more with less—makes for a sharp case study in what corporate reinvention actually looks like when it’s forced by markets, enabled by technology, and judged by capital allocation.

II. Origins: The Coal Era (1860s–1990s)

The story starts in the first great surge of American industrialization—when energy wasn’t an input to the economy, it was the economy. In 1860, several western Maryland coal operators made a straightforward, very 19th-century move: band together to get bigger, safer, and more efficient. They called the new company Consolidation Coal Company. The Civil War slowed everything down, and full operations didn’t begin until April 1864.

From there, the tailwinds were enormous. Coal was the fuel behind nearly every symbol of progress. Pittsburgh steel mills devoured coking coal. Railroads ran on it. Factories, steamships, and household furnaces depended on it. And Consolidation Coal was sitting on rich seams in Western Maryland, with a natural path to expand outward across Appalachia as demand grew.

Over the next century, the company did what commodity businesses do when they want to win: it built scale. CONSOL expanded existing mines, acquired other operators, and accumulated reserves across major U.S. coal fields. It also got a firsthand education in how brutal cyclicality can be. The Great Depression nearly pushed the company into receivership, but it reorganized, restructured its operations, and came out the other side on firmer footing. Then World War II arrived, and CONSOL—like so many industrial companies—shifted into war footing too, supplying coal energy that was essential for transportation and home heating.

After the war, a merger created the Pittsburgh Consolidation Coal Company. And the core strategy stayed consistent for decades: consolidate, expand, and improve efficiency in a fiercely competitive industry where prices swing and survival depends on cost.

The ownership story, though, kept evolving. In 1991, Rheinbraun A.G. offered DuPont stakes in coal mines and $890 million to form an equal-part joint venture called Consol Energy. Through the 1990s—despite falling coal costs—Consol stayed competitive, helped by long-term contracts and investments in longwall mining. Then, in 1998, DuPont sold most of its stake, keeping just 6 percent, while Rheinbraun held 94 percent.

A year later came a moment that quietly set the stage for everything that followed: Consol went public. In 1999, the company launched an IPO on the NYSE under the ticker CNX, using it in part to pay down debt tied to the DuPont buyout and the acquisition of Rochester & Pittsburgh Coal Company. After more than a century of operating largely out of public view, Consol now had public-market accountability—quarterly scrutiny, shareholder expectations, and a stock price that would react to strategic drift.

By the early 2000s, the coal story still looked like a success. Consol stood among America’s premier coal producers. In 2010, it was the leading producer of high-BTU bituminous coal in the United States and the country’s largest underground coal mining company. In 2006, it joined the S&P 500, replacing Knight-Ridder.

But here’s the twist: even as coal hit its modern peak, the company started acting like it could see the next chapter coming. With coal demand increasingly uncertain in the early 2000s, Consol leaned into diversification—especially natural gas. And it wasn’t starting from scratch. Its engineers had known for decades that coal seams don’t just hold coal; they also trap methane. Historically, that gas was a deadly hazard—something you vented to avoid explosions. Consol began asking a different question: what if the problem was actually a product?

III. The Pivot Begins: Entering the Gas Business (1990s–2000s)

Underground coal mines are dangerous places, and methane is one of the biggest threats. It seeps out of coal seams and surrounding rock, gathers in confined spaces, and if it hits a spark, the result can be catastrophic. For decades, mine operators treated methane as something to fear and flush away—spending heavily on ventilation and drainage to keep people alive.

CONSOL eventually realized there was a second way to look at the same molecule. If you were already pulling methane out of the ground ahead of mining for safety, why not capture it, sell it, and build a business around it? That move—turning a hazard into a revenue stream—became the first real step in CONSOL’s shift from a pure coal producer into a multi-fuel energy company.

The early moves were practical and regionally focused. CONSOL’s first major natural gas investment came through the acquisition of MCN Energy Group Inc.’s methane reserves in southwestern Virginia for $160 million. In 2001, it acquired Conoco Inc.’s coalbed methane gas production assets in the same area. Later that year, it spent another $158 million to acquire additional coalbed methane production and pipeline assets from Conoco.

CONSOL didn’t just produce the gas—it looked for ways to consume it too. In 2001, its subsidiary CNX Ventures formed a joint venture with Allegheny Energy Supply Company to build an 88-megawatt coalbed-methane-fueled power plant in Virginia. The facility began operating in 2002, running on methane produced by CONSOL.

By the mid-2000s, the gas operation was large enough to deserve its own label. In 2006, Consol spun off its subsidiary CNX Gas as a standalone company, while still retaining 83 percent of the shares. It was a partial separation—enough to give the gas business its own identity and a clearer capital story, but still tethered strategically to the parent.

Then came the geological catalyst that changed everything: the Marcellus Shale.

In 2007, CNX Gas began investing heavily in Marcellus Shale exploration in Pennsylvania. The Marcellus stretches across much of Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Ohio, and New York—an enormous gas-bearing formation roughly a mile underground. It would become the largest gas-producing formation in the United States. And beneath it sat the deeper Utica Shale, with growing development activity, particularly in Ohio and Pennsylvania.

CONSOL’s commitment went from meaningful to unmistakable in 2010. It acquired Dominion Resources Inc.’s natural gas production and exploration assets for $3.74 billion. Included in the deal was nearly 500,000 acres of Marcellus potential—an addition so large it effectively tripled the company’s position, bringing it to roughly 750,000 acres.

This wasn’t an incremental hedge. It was a declaration. CONSOL was putting billions behind the idea that the fuel defining its next century wouldn’t be the black rock that built Pittsburgh—it would be the invisible gas trapped in gray shale.

In 2011, Consol signed two joint venture agreements designed to speed up development. One was with Noble Energy to jointly develop 663,350 Marcellus acres in Pennsylvania and West Virginia. The other was with Hess Corporation to jointly explore and develop nearly 200,000 Utica acres in Ohio.

The structure mattered. These partnerships brought in capital to accelerate drilling, shared the risk in a business where costs and outcomes could swing wildly, and added technical expertise at a moment when shale development was still as much learning curve as playbook.

Inside the company, though, the strategy created a fundamental strain. Consol Energy now had two businesses living under one roof—and they were heading in opposite directions. Coal faced tightening environmental pressure, intensifying competition from cheap gas in power generation, and weakening demand from traditional industrial customers. Natural gas, meanwhile, looked like the future: cleaner-burning, increasingly abundant, and positioned to benefit from expanding electricity needs and the growth of LNG exports.

For investors, the hybrid was hard to price. Was Consol a coal company with a side hustle in gas? Or a gas company trapped inside a coal wrapper? The market couldn’t quite decide—and that valuation confusion would become a major force in the next chapter.

IV. The Shale Revolution & CNX's Transformation (2004–2013)

To understand CNX’s transformation, you have to understand the shale revolution. And to understand the shale revolution, you have to start with one stubborn Texan: George Mitchell.

George Phydias Mitchell (May 21, 1919 – July 26, 2013) was a businessman, real estate developer, and philanthropist from Texas who is widely credited with pioneering the economic extraction of shale gas. Born in 1919 in the port city of Galveston to Greek immigrant parents, Mitchell didn’t look like the kind of person who would rewrite America’s energy future. But he did—because he refused to quit when the math didn’t work yet.

Through Mitchell Energy, he spent the better part of the 1980s and 1990s experimenting with hydraulic fracturing—fracking—burning time and money while much of the industry rolled its eyes. The basic idea was simple to describe and brutally hard to perfect: inject water, sand, and chemicals into dense shale to crack it open and let gas flow. After years of trial and error, one of Mitchell Energy’s shale gas wells broke through in 1997. It wasn’t just a good well. It was proof that shale could be developed at scale.

Oil historian Daniel Yergin later called Mitchell’s work the “most important, and the biggest, energy innovation of this century.”

Once the formula clicked—horizontal drilling paired with hydraulic fracturing—it didn’t stay in Texas for long. The technique spread across U.S. shale basins and turned previously “uneconomic” rock into a national strategic asset. As the industry applied those methods more broadly starting in the mid-2000s, U.S. oil and gas production surged and reversed a long decline in domestic output.

For Consol Energy, the timing was electric. The company wasn’t just dabbling in gas anymore—it was sitting on top of the Marcellus, one of the richest shale gas formations in North America, with a rapidly expanding acreage position. Mitchell’s innovation turned that buried resource into something developable, financeable, and ultimately central to the company’s future. Consol pushed hard into Marcellus development, applying these new techniques across its holdings.

The shale boom showed up quickly in industry production numbers. As one example from the period, Southwestern’s Appalachian output rose year over year to 1.8 Bcf/d, while CNX Resources Corp. more than tripled its Utica volumes to 0.46 Bcf/d from 0.13 Bcf/d.

But shale’s gift came with a catch. The same success that unleashed enormous volumes of gas also drove prices down—hard. And that price pressure ricocheted through the energy system. Cheap natural gas didn’t just make gas more competitive; it made coal less competitive. In other words: the technology that increased the strategic value of Consol’s gas assets was also undermining the economics of its coal business.

Inside the company, the tension wasn’t theoretical anymore. Consol was trying to run two businesses with different DNA. Coal demanded stability, long-life assets, and a cash-flow-and-dividend mindset. Shale demanded capital intensity, fast learning cycles, and constant reinvestment to drill and complete the next wave of wells. Investors didn’t know which story they were buying—and management couldn’t fully satisfy both.

That’s when the pressure started to build. More sophisticated investors began to see what the market was already signaling: a conglomerate discount. Consol’s pieces looked like they might be worth more apart than together. All that remained was the hard part—getting the company to choose.

V. The Great Separation: Spinning Off Coal (2015–2017)

By the mid-2010s, the “two companies in one” problem had stopped being an analyst talking point and started becoming a strategic choke point. Consol could keep trying to balance coal’s long-life, contract-driven world with shale gas’s capital-hungry, fast-iteration reality—or it could choose.

In December 2016, the company announced its intent to separate its coal business from its gas business. It was the public acknowledgement of a decision that had been brewing for years, accelerated by market whiplash and growing pressure for clarity. The company had already been shedding coal assets, and in early 2017 it elevated the separation to a stated “strategic priority.”

The rationale was straightforward, and hard to argue with. Coal and gas appealed to different investor bases and demanded different capital allocation frameworks. Their regulatory and environmental outlooks were diverging. And as long as they were bundled together, capital markets struggled to value either business cleanly.

On October 31, 2017, Consol Energy Inc. announced that its board had given final approval for the plan: split into two publicly traded companies—one coal company and one natural gas exploration and production company.

That split became effective November 28, 2017. The natural gas business was named CNX Resources Corporation. It stayed on the New York Stock Exchange and kept the ticker symbol “CNX.” The coal business took back the CONSOL Energy Inc. name and began trading on the NYSE under a new ticker: “CEIX.”

The mechanics followed the standard spin playbook. On November 28, 2017, shareholders received one share of CEIX for every eight shares of CNX they owned as of the November 15, 2017 record date. Fractional shares weren’t issued; shareholders received cash instead.

Nick DeIuliis, who had risen through the company over decades, framed it as the end of a long arc and the start of two cleaner stories: “Today’s historic announcement is the culmination of a strategy over a decade in the making. Our objective was to once again transform a 150-year old institution, which owns and operates the best natural gas and coal assets in the world. We have accomplished that goal and, in doing so, positioned two new companies to dedicate singular focus to their individual industries and market segments. The E&P company is now one of the premiere pure-play natural gas E&P companies with a significant Marcellus and Utica Shale legacy acreage position, low-cost structure, and stacked pay opportunities.”

But this wasn’t just a financial engineering exercise. It was a decisive break with more than 150 years of corporate identity. For employees who’d built careers in coal, it was emotionally loaded—almost like watching a family name get handed to someone else. For investors, though, it delivered what the market had been demanding: choice and clarity. You could own a pure-play Appalachian gas operator, or you could own a pure-play coal company—each with its own strategy, risks, and discipline.

And the market immediately put numbers on that judgment. Based on the when-issued share price at the close of business on November 28, 2017, and roughly 28 million shares outstanding, CEIX’s equity value was about $600 million. CNX Resources emerged as the larger, better-capitalized entity—an unmistakable signal of where management believed the future was headed.

VI. The DeIuliis Era: Radical Simplification & Tech Innovation (2017–2022)

With the spin-off complete, CNX finally had what it had been missing for years: a single identity, a single capital story, and a CEO who wanted to run the company in a way that looked very different from the typical shale playbook.

That CEO was Nick DeIuliis. He’d spent more than three decades inside the organization, holding roles that spanned engineering and operations through senior leadership, including president and CEO, COO, and senior vice president of strategic planning. He joined in the 1990s and became CEO in 2014—meaning he didn’t just inherit the transformation; he helped engineer it.

In the years surrounding the separation, shareholder pressure also sharpened CNX’s posture. Southeastern’s engagement with the company ushered in a new board and a more explicit focus on value creation per share. DeIuliis leaned into that framing: less “How big can we get?” and more “How much value can we create for each share that stays outstanding?”

He also became one of the more outspoken CEOs in the U.S. energy business. When he retired, The Pittsburgh Post dubbed him a “firebrand,” describing him as a fierce defender of fossil fuels and a critic of renewable energy. He positioned himself as a pro-capitalism, free enterprise advocate and lifelong Pittsburgher, and later wrote a book, Precipice, arguing that the country faced a dangerous mix of economic, social, and geopolitical threats.

But whatever you think of the rhetoric, the more consequential story is the operating system he put in place at CNX. Post-spin, DeIuliis organized the company around four pillars.

Pillar 1: Operational Excellence

CNX pushed what it called “Deep Manufacturing”—a deliberate attempt to treat natural gas development less like wildcatting and more like advanced manufacturing: standardized processes, repeatable execution, and continuous improvement. The ambition was to be a premier, ultra-low carbon intensive natural gas development, production, midstream, and technology company in Appalachia—one of the most energy-abundant regions in the world.

Pillar 2: Technology Innovation

The “tech company” framing wasn’t just branding. CNX invested in digital transformation and partnered with Dynamis to bring the first electric-powered drilling rig to the Appalachian Basin. The rig was fueled by onsite natural gas through high-efficiency, continuous-duty natural gas reciprocating power generation, paired with battery energy storage.

CNX also moved to cut emissions by becoming the first driller in the Appalachian Basin region to eliminate diesel engines from its hydraulic fracturing fleet, switching to all-electric.

Pillar 3: Capital Discipline

While many shale producers chased production growth, CNX made free cash flow the centerpiece. The company later said it expected to generate nearly $300 million of free cash flow in 2024, and it used that cash to aggressively repurchase shares—74 million shares retired, a 33% reduction in shares outstanding since the third quarter of 2020.

Pillar 4: Shareholder Returns

DeIuliis was explicit about what he was optimizing for. As the company put it: “Since the inception of the buyback program in 2020, we have retired approximately 36% of our outstanding shares. We continue to believe that our discretionary share repurchase program provides an opportunity to create incredible value for our long-term, like-minded shareholders, who will benefit as their per share value continues to grow meaningfully over the coming years.”

In practice, that meant CNX’s hurdle rate for acquisitions was unusually blunt: the best deal often was “acquiring ourselves.” Unless an outside acquisition could beat the value of buying back CNX stock at the current price, CNX preferred to shrink the share count and concentrate ownership.

The simplification went beyond buybacks. CNX rationalized its asset base—selling non-core positions and narrowing capital spending to the highest-return opportunities in its core Marcellus and Utica footprint. It also exited midstream businesses, selling pipeline stakes to simplify the model and free up capital.

And DeIuliis wanted CNX’s identity to extend beyond wells and capital returns. In 2021, the company created the CNX Foundation to administer a $30 million commitment aimed at helping people in the Appalachian Basin pursue economic success. CNX also launched a mentorship academy for high school students in disadvantaged rural and urban areas, with the goal of exposing them to careers and helping them secure a job or apprenticeship by graduation. DeIuliis contributed $1 million of his 2022 compensation to support the academy, and proceeds from his book Precipice also supported it.

For a long time, though, the market didn’t reward any of this. Analysts and investors kept asking the same question: why isn’t CNX growing? In an industry trained to equate success with more drilling and higher volumes, CNX’s insistence on free cash flow per share—and on shrinking its way into a stronger company—was easy to misunderstand. The stock languished even as operational execution improved and the company kept doing exactly what it said it would do.

VII. The CEO Transition & New Strategy (2022–Present)

After years of CNX insisting that discipline mattered more than drilling headlines, the next big question became: what happens when the architect of that approach steps aside?

CNX announced that Alan Shepard, then serving as president and chief financial officer, will become president and CEO effective January 1, 2026. He will succeed Nick DeIuliis, who will retire at the end of 2025 after 35 years with the company. DeIuliis will remain involved as a member of CNX’s board.

In other words, this wasn’t framed as a clean break. It was framed as a handoff.

Shepard rejoined CNX in 2020 and became CFO in June 2022. He brought more than two decades of energy experience, including senior finance roles at EdgeMarc Energy Holdings, and earlier work at PwC. He holds a bachelor’s degree in accounting and administration from Thiel College and an MBA from Carnegie Mellon University’s Tepper School of Business.

CNX positioned the transition as continuity rather than reinvention. Shepard had been deeply involved in building and executing the company’s capital allocation framework, and his elevation telegraphed that the board wanted the same operating system to keep running. As the company put it: “Since rejoining CNX in 2020, Alan has been instrumental in the development and execution of the company's unique Sustainable Business Model.”

What did change—dramatically—was the world around CNX. Since the spin-off, the market narrative for Appalachian gas has shifted from short-term storage levels and weather to something bigger: structural demand growth. And that shift brought fresh tailwinds to the basin.

The AI/Data Center Power Demand Story

A November study from the Hamm Institute for American Energy estimated that meeting AI-driven power demand could require U.S. natural gas production to rise by 10% to 15% by the early 2030s—arriving at the same time LNG exports continue expanding.

Moody’s has similarly estimated that data centers alone could drive an additional 2 Bcf/d to 4 Bcf/d of demand by 2030, with the caveat that the number could be higher if renewables scale more slowly than expected. Even in a faster-renewables scenario, Moody’s argues data centers still create a durable tailwind for natural gas.

Appalachian Advantages

Those demand forecasts matter even more in Appalachia because of what the region already has: some of the lowest-cost supply in the country, plus proximity to major population centers. NGI’s Rau noted that those factors make in-basin development attractive for data centers, especially as developers look for reliable power and shorter supply chains.

And that demand is starting to shape infrastructure decisions. The surge in power load has helped justify a new wave of takeaway projects aimed at moving more gas out of Appalachia. Transco, for example, announced a new project called “Power Express,” a 950 MMcf/d pipeline running largely along existing rights of way from Station 165 to northern Virginia—straight into the heart of “Data Center Alley.”

LNG Export Growth

At the same time, LNG has gone from “promising” to “here.” Venture Global’s Plaquemines LNG facility shipped its first commissioning cargo in late 2024 and ramped toward full capacity through 2025. ExxonMobil and QatarEnergy also began the final commissioning phase of the Golden Pass LNG terminal.

Against that backdrop, CNX made a notable move of its own. The company closed its acquisition of Apex Energy II, LLC’s natural gas upstream business and associated midstream assets in the Appalachian Basin for total cash consideration of approximately $505 million. CNX described the deal as a bolt-on that expands its stacked Marcellus and Utica undeveloped leasehold in the CPA region, while adding an infrastructure footprint it can leverage for future development. CNX also said the acquisition is expected to be immediately accretive to its key metric: free cash flow per share.

The deal added scale right where CNX wanted it—central Pennsylvania’s Utica and Marcellus development corridors—by bringing in approximately 8,600 undeveloped Utica acres and 12,600 undeveloped Marcellus acres.

VIII. The Technology & Operations Playbook

What makes CNX different operationally isn’t a single breakthrough. It’s the way the company tries to turn drilling into a repeatable system: tighter processes, faster learning loops, and technology that shows up in the field, not just in slide decks.

Deep Utica Development

One of the clearest examples is CNX’s push into the deep Utica. Company leaders have said they’re “pretty excited” about early results from the first deep Utica wells brought online recently. Last quarter, CNX turned in line two of the three deep Utica Shale wells it drilled in Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, during the second quarter. Regulatory filings show the two wells had average lateral lengths of 13,800 feet, roughly 2.6 miles. Alan Shepard, then CFO, said the wells were “absolutely meeting expectations” on both drilling costs and performance.

The deeper point is what those wells signal about the operating system. CNX said drilling times were nearly halved since 2023, a change that makes deep Utica development materially more competitive. And it’s not treating the Utica as a standalone project. The company is testing Marcellus co-development as it looks to expand the “stacked pay” concept—multiple productive layers, developed with shared surface infrastructure and a unified plan.

Geology matters here. The Utica sits beneath the Marcellus—about two miles underground versus roughly one mile for the Marcellus—which historically made it more expensive to develop. CNX’s bet is that efficiency gains in drilling and completion design can close that gap. If it works, stacked pay becomes a real advantage: more inventory and more production potential from the same footprint, with better capital efficiency.

Environmental Technology Leadership

CNX’s technology story also runs through emissions—especially methane. Coalbed methane is a greenhouse gas emitted from active and closed (or abandoned) underground and surface coal mines, and without capture and abatement programs it would be released directly into the atmosphere. Operating in the Appalachian Basin—which the company notes has the lowest methane intensity among major U.S. natural gas basins—CNX has focused on capturing waste gas from mining operations.

The company has said it captured approximately 9.1 million metric tons of waste methane CO₂e—nearly 20 times greater than its Scope 1 emissions.

Radical Transparency Initiative

CNX has also tried to differentiate on how it shows its work. Its Radical Transparency environmental monitoring and real-time disclosure initiative—done in collaboration with Pennsylvania Governor Shapiro and the state Department of Environmental Protection—aims to give local communities a clearer, more immediate view into operations. CNX says the level of transparency is “second to none” in the industry.

Partnership Innovations

Then there are the partnerships that blur the line between producer and end-user. CNX partnered with Pittsburgh International Airport (PIT) to produce alternative fuels and electricity from natural gas wells CNX operates on airport property. PIT sits atop shale formations including the Utica and Marcellus, and the concept is straightforward: produce energy where it’s needed, reduce transport complexity, and turn gas into useful products onsite—compressed natural gas for vehicle fleets, and liquefied natural gas for other applications.

The partnership began in 2013, and CNX started drilling natural gas wells there in 2014. By 2022, it supported a five-generator, 20 MW micro-grid powered by natural gas, plus a 3 MW solar array—together providing 100% of the airport’s electricity needs.

In May 2024, CNX and KeyState Energy signed a letter of intent for a project to make sustainable, hydrogen-based aviation fuel at Pittsburgh International Airport using coal-mine methane gas. Formal approval depends on the approval of federal hydrogen production tax credits under the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022.

IX. Business Model & Strategic Positioning Today

CNX today is a pure-play Appalachian natural gas producer—but not a simple “drill it and sell it” operator. It also runs integrated midstream assets: it designs, builds, and operates gathering systems that move gas from the wellhead into interstate pipelines or local sales points. CNX owns and operates about 2,700 miles of gathering pipelines, plus natural gas processing facilities. On the operations side, it also offers turn-key water sourcing, delivery, and disposal—both for its own drilling program and for third parties.

As of year-end 2023, CNX held rights on 527,000 net Marcellus acres and 607,000 net Utica acres.

Financial Model: Free Cash Flow Generation

By late 2025, CNX’s story in public markets had become remarkably consistent: generate free cash flow, repeat. In its Q3 2025 results presentation on October 30, the company highlighted its 23rd consecutive quarter of positive free cash flow and raised its full-year free cash flow guidance.

The quarter also delivered a jolt of investor attention. CNX’s earnings report came in well ahead of analyst expectations, and the stock rose 3.56% in pre-market trading. Reported earnings per share were $1.21 versus a forecast of $0.40, and revenue was $583.8 million versus expectations of $438.29 million.

CNX raised its 2025 free cash flow guidance to about $640 million, up from its prior estimate of $575 million. The driver wasn’t just operations—it was also more asset-sale proceeds, now projected at about $115 million versus the prior guidance of $50 million.

Capital Returns: Share Buybacks

If free cash flow is the engine, buybacks are the signature move. CNX continued leaning into repurchases, including buying back 6.1 million shares in Q3 at an average price of $30.12 per share, for a total of $182 million.

Zoom out, and the scale of the effort becomes the point. Since Q3 2020, CNX reduced shares outstanding by about 43%, from 224.5 million to 134.8 million as of October 20, 2025.

That discipline carried into 2025. CNX delivered a strong first quarter, generating $100 million of free cash flow—its 21st consecutive quarter of positive FCF. Since launching its seven-year plan in 2020, the company said it generated about $2.3 billion in cumulative free cash flow.

Hedging Strategy

CNX has also tried to make its cash flows less hostage to the next gas-price swing. Even after a recent drop in natural gas prices, the company positioned itself as well-equipped to handle volatility, pointing to its low-cost status in Appalachia and what it described as one of the strongest hedge books in the industry.

Production Guidance

For 2025, CNX expects annual sales volumes of about 605 to 620 Bcfe, with capital expenditures projected between $450 million and $500 million.

X. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Porter's 5 Forces

Threat of New Entrants: MODERATE

Appalachia isn’t a brand-new frontier where a fresh driller can just show up, lease land, and start taking share. It’s a mature basin, and the best acreage positions are already in the hands of incumbents. A would-be entrant would need real capital and, more likely, would have to buy its way in by acquiring an existing position. Add in Pennsylvania’s regulatory complexity, and the friction goes up another notch. As one industry view puts it, “Appalachian producers have the lowest costs and largest reserves, but have takeaway capacity constraints.” That doesn’t stop entry, but it does narrow who can realistically play.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW

The oilfield services world has become increasingly commoditized, which shifts leverage toward the operator. CNX benefits from that dynamic, and its scale helps when negotiating pricing and availability. It has also pulled key technologies in-house, which further reduces dependence on outside vendors and makes supplier power even less of a choke point.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: HIGH

This is the brutal truth of selling natural gas: you don’t get to “brand” it. CNX is a price-taker because a molecule of methane is a molecule of methane, regardless of who produced it. Buyers can shop around, and the market sets the clearing price. CNX does get some help from geography—proximity to premium Northeast markets and the rise of in-basin demand, including from data centers—but those are advantages at the margin, not pricing power in the classic sense.

Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE-HIGH

For power generation, renewables keep taking share. Coal has fallen hard but hasn’t vanished. Nuclear is the long-game competitor for always-on electricity. Still, gas keeps winning on reliability and responsiveness, especially when the load can’t wobble. And that’s where the modern demand story matters: “Data centers and AI will likely still depend on natural gas for power reliability beyond 2030, and will therefore keep contributing to growth in midstream infrastructure.” Substitutes are real, but gas remains the default solution when reliability is non-negotiable.

Industry Rivalry: HIGH

CNX is competing in one of the most crowded, well-capitalized gas neighborhoods in the country. EQT is already the largest U.S. gas supplier, producing 44% more than its nearest competitor, Exxon Mobil Corp. CNX’s competitors include Ember Resources, Energy Corporation of America, Range Resources, and EQT. And the landscape is still shifting: Chesapeake and Southwestern Energy are combining in a $7.4 billion merger and are poised to overtake EQT as the nation’s largest gas producer. In a commodity business, scale, cost, and access to markets decide who thrives—and consolidation is one way the industry keeps trying to manufacture those advantages.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

1. Scale Economies: MODERATE

CNX is big enough to spread fixed costs over a meaningful production base, and its integrated midstream footprint provides useful infrastructure leverage. But it’s not the basin’s scale leader. Larger peers—especially EQT—can match or exceed these benefits, which caps how much “scale” alone can protect CNX.

2. Network Effects: NONE

There’s no flywheel here. Producing more gas doesn’t create a network that makes producing even more gas easier in the way it might in software or marketplaces.

3. Counter-Positioning: WEAK/MODERATE

CNX’s “Deep Manufacturing” mindset and its capital discipline are a real strategic posture—especially in an industry that spent years rewarding growth at any cost. But it’s not a position competitors are structurally unable to copy. If the industry keeps prioritizing free cash flow and efficiency, others can adopt the same language and many of the same practices.

4. Switching Costs: NONE

For buyers, switching is trivial. Gas is purchased to spec, and the market is designed to make the product interchangeable.

5. Branding: NONE

CNX isn’t selling consumer goods. End customers don’t pay extra because they like the logo. What matters is price, consistency, and delivery.

6. Cornered Resource: MODERATE

High-quality Marcellus and Utica acreage is finite, and most of it is already held by established players—which creates a barrier against newcomers. CNX’s position is strong, but it’s not singular. Where it does have something more proprietary is in the accumulated operational data and the know-how embedded in its methods.

7. Process Power: MODERATE-STRONG

This is where CNX has its most credible edge. Over time, the company has built an operating system—cost discipline, completion efficiency, and repeatable execution—that’s hard to replicate quickly, even if rivals know what CNX is doing. CNX maintained its free cash flow guidance at $575 million while tightening costs in its Utica development, including a 20% reduction in drilling costs. In a business where the product is identical, process is often the closest thing to a moat.

Overall Assessment: CNX operates in a tough, commoditized industry with limited durable competitive advantages. Its best defense isn’t structural. It’s behavioral: process power, cost leadership, capital discipline, and a focused position in a core part of Appalachia—advantages that don’t eliminate the commodity reality, but can tilt outcomes over time.

XI. Bull vs. Bear Case

The Bull Case

Operational Excellence: CNX has built its whole post-spin identity around being a low-cost operator in Appalachia, and the financials reflect that. The company reported a strong cash operating margin for the quarter, supported by all-in cash costs that were just over a dollar per Mcfe before DD&A.

Strategic Positioning: Appalachia is no longer just a supply story; it’s increasingly a demand-and-infrastructure story. The basin sits in the path of multiple tailwinds at once—rising LNG exports, new pipeline projects aimed at moving gas to the Mid-Atlantic, and power demand growth tied to data centers. CNX is bullish on how those forces compound, projecting that combined demand and takeaway capacity can grow meaningfully by 2028 versus 2023 levels, with incremental demand coming from coal plant retirements and new data center load.

Capital Discipline: In an industry with a long history of “drill first, explain later,” CNX has stayed unusually consistent: free cash flow per share first, and growth only if it clears that bar. The most tangible proof point is the share count. Since 2020, CNX has retired a large chunk of its outstanding shares—about 43%—turning buybacks into a central lever for compounding per-share value.

Energy Transition Beneficiary: Whether you call it a bridge fuel or a reliability fuel, natural gas keeps showing up as the backstop when the grid can’t afford to be wrong. By late 2025, the gas market looked very different than the oversupplied environment of 2024. Prices moved higher alongside record LNG exports, a more structural shift in power demand tied to AI-related load growth, and a U.S. production landscape that remained far more disciplined than in prior cycles.

Undervalued: There’s still an argument that the market hasn’t fully repriced the company’s identity shift—from a coal-weighted legacy story into a focused, shareholder-return-driven gas producer with core Appalachian inventory.

Free Cash Flow: CNX’s ability to generate steady free cash flow is the flywheel behind everything else: buybacks, balance-sheet flexibility, and the option to invest opportunistically when the setup is right.

The Bear Case

Commodity Exposure: No matter how good the operating system is, CNX sells a commodity. It’s a price-taker, and when natural gas prices break, the whole model gets stress-tested. That played out in 2024, when weak regional pricing contributed to muted production growth in Appalachia. Texas Eastern M-2, 30 Receipt—a key Appalachia benchmark—averaged $1.670/MMBtu in 2024.

Limited Growth Profile: CNX has often preferred a maintenance-mode posture to chasing volume. That protects returns when prices are weak, but it can cap upside if demand ramps faster than expected. Looking ahead, the company has signaled continued “maintenance mode” production in 2026.

Energy Transition Risk: If the energy transition accelerates materially—or policy turns more restrictive—gas demand could face a faster long-term decline, raising the risk of stranded inventory.

Competition: Appalachia is crowded, and the biggest players have real scale advantages. EQT and CNX, both Pennsylvania-based, are among the region’s largest drillers. Continued consolidation could further intensify pressure on smaller independents.

Regulatory Risk: Pennsylvania’s environmental rules can add cost and complexity, and shifts in federal policy represent another layer of uncertainty—especially around permitting, emissions, and enforcement.

Takeaway Constraints: The basin’s growth has slowed in recent years, in large part because the major interstate pipelines moving gas out of Appalachia are effectively maxed out. Without new takeaway, it’s hard to grow meaningfully—even with great rock.

No Structural Moat: CNX’s advantage is mostly execution. The commodity nature of the product limits pricing power and makes sustained above-market returns difficult without continual cost and capital-allocation outperformance.

Key Metrics to Watch

For investors tracking CNX’s ongoing performance, three metrics deserve particular attention:

-

Free Cash Flow Per Share: This is the company’s north star. If CNX keeps shrinking the share count while generating steady free cash flow, per-share value can compound even without headline production growth. Track quarterly free cash flow against changes in shares outstanding.

-

All-in Production Costs Per Mcfe: CNX’s “low-cost producer” claim has to hold up quarter after quarter. Watch fully burdened cash costs and how they stack up against peers like EQT, Range Resources, and Antero.

-

Share Repurchase Activity: Management has made it clear that its default “acquisition” is buying back CNX stock. Repurchase volumes and average prices are a direct signal of how management is weighing intrinsic value versus the market price.

XII. The Future of CNX & Natural Gas

As 2025 draws to a close, CNX sits in a familiar place for any long-lived industrial company: not at the finish line, but at the next decision point. The big transformation is real. The coal conglomerate structure is gone. The company is simpler, more focused, and far more explicit about what it’s trying to do: generate free cash flow, allocate it with discipline, and compound per-share value.

What’s changed most isn’t CNX’s message. It’s the backdrop.

The defining macro storyline of 2025 is the so-called “AI energy boom.” Data centers—once a niche demand factor—have become a year-round pull on the gas market. By late 2025, AI data centers were projected to consume roughly 1.9 Bcf/d, and that estimate had already been revised upward multiple times during the year. The important part isn’t the precision of the number. It’s the shape of the demand: always on.

That’s a different animal than residential heating, which spikes in winter and fades in spring. Data centers need power 24/7, and in much of the U.S. the grid still leans on natural gas turbines for that reliability—especially when intermittent renewables can’t carry the load or when demand surges faster than new transmission can be built. Layer in a world of geopolitical realignment and energy security concerns, and gas starts to look less like a short-term trade and more like strategic infrastructure.

Against that, CNX’s coming CEO transition reads like a hand on the wheel, not a turn. Alan Shepard’s move into the top job signals continuity more than upheaval. The framework stays the same: free cash flow generation, capital discipline, and shareholder returns.

The obvious question in a consolidating basin is whether CNX itself could become a target. Three privately held shale gas producers and Pittsburgh independent CNX Resources Corp. have been cited as potentially attractive to Marcellus operators looking for bolt-on acreage. But CNX has been consistent about how it thinks about that trade-off. As Nick DeIuliis put it on an earnings call, emphasizing the company’s preference when weighing capital allocation: “We look at everything that comes to market. Our threshold is acquiring ourselves.”

Zoom out far enough, and CNX’s arc starts to feel like a broader American industrial story. A company founded in the Civil War era, built on coal, hardened through depressions and wars, then forced—by markets and technology—to reinvent itself into a natural gas operator that talks like a process-driven tech company. That’s not a guarantee of future success, but it is proof of a rare corporate trait: adaptability.

Natural gas, of course, is still fighting its own identity battle. Is it truly a “bridge fuel” on the way to something else, or does it remain essential for much longer than many people want to admit? The answer will shape whether CNX is ultimately seen as a durable value creator—or a business living on borrowed time.

For now, CNX is positioned right where the argument is hottest: at the intersection of AI-driven power demand, LNG exports reshaping global energy flows, and the messy reality that the grid still can’t rely on intermittent renewables for baseload reliability. Whether those tailwinds prove durable or fleeting will determine what this latest reinvention is worth to the shareholders betting on it.

XIII. Key Resources for Further Research

If you want to go deeper on CNX—and on the Appalachian gas machine it operates inside—these are the best places to keep pulling the thread:

-

CNX investor presentations and quarterly earnings materials – The clearest primary-source record of how management explains the strategy, tracks execution, and talks about capital allocation. Available at investors.cnx.com

-

The Frackers by Gregory Zuckerman – The most readable, ground-level account of how the shale revolution actually happened, and why it reshaped companies like CNX

-

CNX 10-K and proxy filings – The unfiltered detail: risk factors, compensation and governance, hedging, reserves, and the mechanics behind the narrative

-

EIA Appalachian Basin analysis – The best baseline data on production, pricing dynamics, and how Appalachia fits into the U.S. natural gas picture

-

Nick DeIuliis shareholder letters (2017–2025) – A direct window into the worldview that shaped CNX’s post-spin identity: discipline, simplification, and per-share value

-

The New Map by Daniel Yergin – Useful context for the bigger forces around CNX: energy security, geopolitics, and the shifting role of gas in a changing world

-

Industry research from Tudor Pickering and Raymond James – Helpful for understanding how professional analysts frame Appalachian producers, including costs, inventories, and basin-level constraints

-

Pennsylvania DEP reports – The regulatory and permitting reality on the ground in CNX’s home state, including environmental compliance and operational oversight

-

Natural Gas Intelligence (NGI) – One of the better sources for day-to-day Appalachia coverage, pipeline developments, and market color

-

Harvard Business Review case studies on corporate transformation – Not about CNX specifically, but valuable frameworks for thinking about what it really takes to change a company’s identity and operating system over time

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music