CNO Financial Group: The Unlikely Survivor's Tale

Introduction & Episode Roadmap

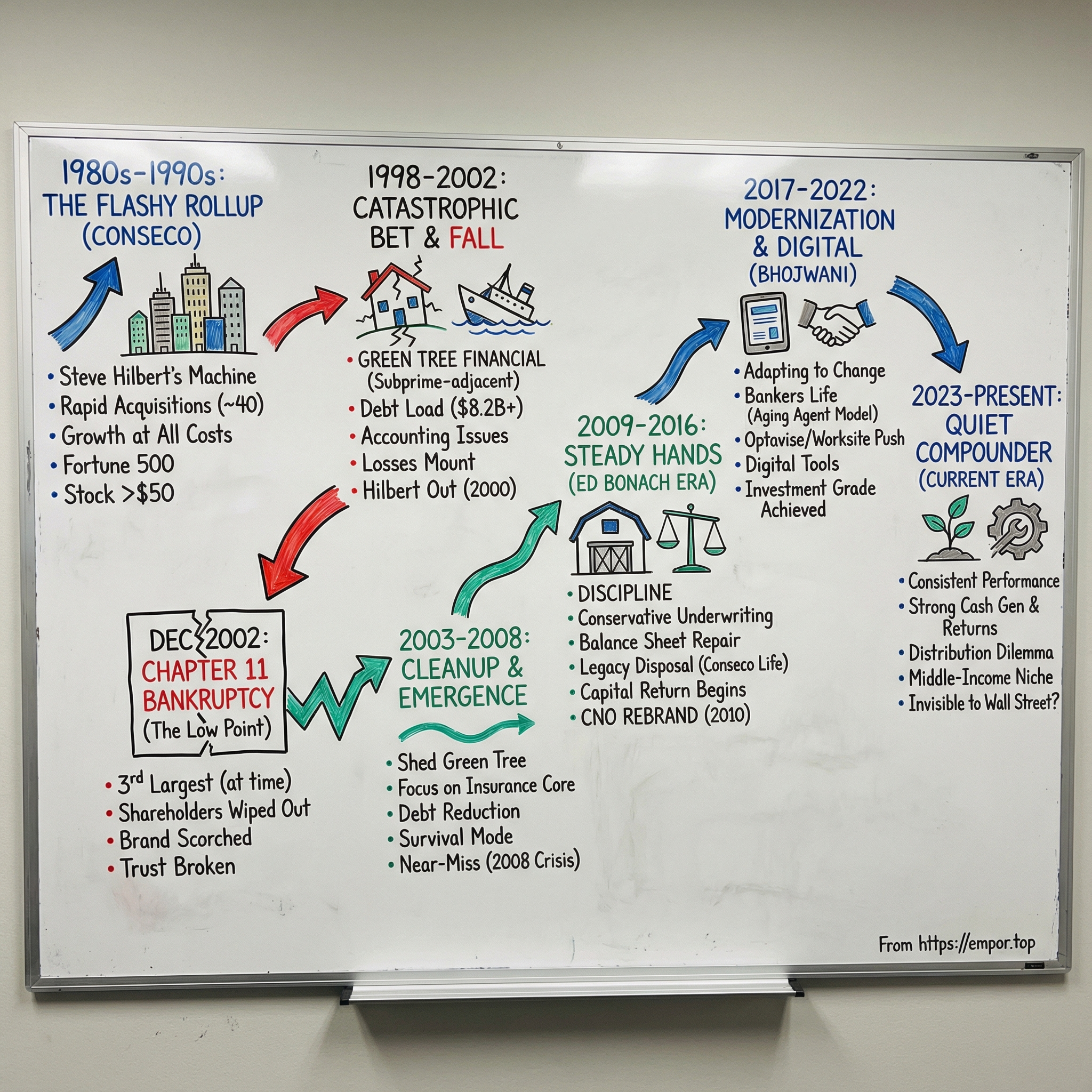

Picture the scene: December 2002, Carmel, Indiana. In a modest conference room, executives huddle around speakerphones while lawyers slide stacks of paperwork across the table. The company they built—once a Wall Street darling with more than $100 billion in managed assets—has just tipped into Chapter 11. At the time, it was the third-largest U.S. bankruptcy on record, behind only WorldCom and Enron.

A few years earlier, Conseco stock had traded above $50. Now those certificates are basically souvenirs. Thousands of jobs are gone. And millions of policyholders are left asking the only question that matters in insurance: will my coverage still be there when I need it?

Conseco filed for Chapter 11 in 2002 and emerged nine months later in 2003. But “emerged” is a generous word. The brand was scorched, the balance sheet was shredded, and trust—among agents, customers, and markets—was going to take years to earn back.

Now jump forward two decades. That same company—reborn as CNO Financial Group—trades on the New York Stock Exchange with a market cap as of March 2025 of about $4.14 billion. It serves millions of policyholders, pays billions in claims, and manages tens of billions in assets. It has quietly sent billions back to shareholders while remaining, to most investors, essentially invisible.

That’s the improbable arc of this story: a go-go 1990s rollup that chased growth, a disastrous detour into subprime-adjacent lending, a bankruptcy that should have been the end, and then a slow, methodical rebuild—tested again by the 2008 financial crisis and still evolving today.

CNO Financial Group, Inc. is a financial services holding company based in Carmel, Indiana. Through its insurance subsidiaries, it sells life insurance, annuities, and supplemental health products to millions of Americans—primarily people who don’t show up in glossy brokerage ads or private-bank pitch decks.

And that’s the paradox at the center of CNO. Its biggest vulnerability is also its most defensible niche: it focuses on middle-income, pre-retiree and retired Americans. People too well-off for Medicaid, but not wealthy enough to have a dedicated advisor calling them back. They still need protection—against medical bills, against income shocks, against outliving their savings—and CNO built its business around finding and serving them.

So here’s the tension that makes this worth our time. Is CNO a quiet compounder hiding in plain sight? Or is it a melting ice cube—stuck with an aging distribution model while digital-first insurgents remake how insurance gets sold?

Let’s dig in.

The Insurance Industry Context: Understanding the Playing Field

Before we rewind into the Conseco saga, it helps to understand the game CNO is playing today. Insurance gets described like it’s a vending machine: collect premiums, pay claims, invest the float. That’s directionally true. But in practice, the details—who you sell to, what you sell, and especially how you sell—determine whether you’re a steady compounding machine or a slow-motion accident.

CNO’s target customer is middle-income, pre-retiree and retired America. It reaches them through a mix of exclusive agents, independent producers (some of whom sell one or more product lines exclusively), and direct marketing.

On the product side, CNO largely lives in three lanes.

First is supplemental health: Medicare supplement, cancer insurance, accident coverage, hospital indemnity—policies designed to plug the holes that primary coverage leaves behind.

Second is life insurance, from simplified-issue final expense policies all the way to more traditional whole life and term.

Third is annuities—products that turn a pool of savings into a stream of guaranteed income, which becomes a very real need the moment a paycheck stops.

That middle-income market is both enormous and chronically underserved. Think Americans earning roughly $30,000 to $100,000 a year—teachers, nurses, plumbers, office workers. They don’t have the kind of wealth that pulls in a full-service advisor. But they still face the same scary set of risks: healthcare costs that spike in retirement, the financial shock of losing a spouse, and the looming fear of outliving savings. Someone has to meet them where they are.

In CNO’s world, distribution is destiny. The company sells through three channels: career agents who primarily sell the company’s products, independent agents who may represent multiple insurers, and direct-to-consumer marketing through TV and direct mail. Each channel comes with its own trade-offs—different acquisition costs, different customer relationships, and different policy persistency.

CNO contracts with approximately 4,900 exclusive insurance agents and over 5,500 independent partner agents nationwide.

Underneath it all is the core economic engine: premiums come in now, that money gets invested as float, and claims get paid later. If underwriting is disciplined and the investment portfolio is managed well, the company keeps the spread. If either side goes wrong—pricing too aggressively, taking too much investment risk, or misjudging claims—insurance can unravel fast.

Now zoom back to the 1990s. Why did consolidation look so tempting? The industry was fragmented, full of smaller insurers with bloated overhead and outdated systems. Conseco leaned hard into that logic, growing quickly through roughly 40 acquisitions across the 1980s and 1990s. The pitch was simple: buy “sleepy” insurers, cut costs, modernize, and earn better returns on the portfolio. When that playbook worked, it looked like financial alchemy.

And when it didn’t… well, that’s where the story gets interesting.

For anyone trying to understand CNO—then or now—this is the key: it’s fundamentally a distribution business wearing an insurance-company suit. The products are not unique. The advantage, if there is one, comes from reaching the right customers efficiently, keeping them for a long time, and earning the right to sell them the next policy.

The Conseco Rise: Steve Hilbert's Rollup Machine (1979–2000)

Every great business story needs a main character, and Stephen Hilbert fit the role perfectly.

Hilbert didn’t come up through actuarial tables or corporate apprenticeships. He grew up in a small rural community near Terre Haute, Indiana, went to Indiana State University, and then left after two years. As he told Barron’s in 1991: “I dropped out to sell encyclopedias.”

That detail matters. Hilbert was a born salesman. And in the version of insurance he believed in, growth wasn’t just a goal—it was the point. He understood hustle, deal-making, and the power of a compelling story. The finer points of governance and risk management were not what made his heart beat faster.

He founded Conseco with $10,000 in 1979. He co-founded the company and raised capital door-to-door around Indiana. Conseco began operations in 1982, and three years later it went public.

Then the machine kicked in.

The rollup playbook was clean and repeatable: find insurers with real policyholder bases but sleepy management. Buy them at attractive prices. Pull the operations into Carmel, Indiana. Cut overhead. Juice investment returns by running a more aggressive portfolio. Rinse and repeat.

And repeat they did. Conseco’s main growth engine was acquisition—on average, a target about every six months.

Through the 1990s, the results looked like magic. Conseco’s earnings increased sixteen-fold from 1986 to 1992, and the stock kept climbing. By 1992, the company had about $15 billion in assets, making it the state’s second-largest insurance company and fourth-largest corporation. More deals followed, and by 1996 Conseco was in the Fortune 500. From 1988 to 1998, it enjoyed a decade of financial achievement, with stock gains averaging nearly fifty percent annually.

The acquisitions that mattered most weren’t just bigger—they were strategic. Bankers Life brought a dedicated career agent force focused on seniors. Colonial Penn added direct-to-consumer marketing and TV-driven brand recognition. Washington National expanded the product set into supplemental health and added worksite distribution capabilities.

By the time Hilbert was forced to resign in April 2000, Conseco had gone from $102 million in assets to more than $52 billion. Headcount had ballooned to 17,000. As chairman, president, and CEO, Hilbert had built a company with $100 billion of assets under management—and made himself one of the highest-paid executives in insurance.

In 1998 alone, Hilbert received about $69.7 million in compensation. This was the era of imperial CEOs, and he leaned into it. Conseco ran a major campaign pitching itself as the “Wal-Mart of financial services.” The company’s name went on arenas and into pop culture: in 1999, the home of the Indiana Pacers became Conseco Fieldhouse. Hilbert’s horse, Stephen Got Even, even ran the Triple Crown circuit that year—finishing 14th in the Kentucky Derby, 4th in the Preakness, and 5th in the Belmont.

But the flash was covering up a more dangerous reality: the culture was growth at all costs. As the decade wore on, the warning signs multiplied. Deals got larger. Integration got messier. Complexity piled up. And each acquisition demanded more leverage than the last.

By the late 1990s, Hilbert had also started to run out of obvious insurance targets. The easy wins were gone. To keep feeding the growth narrative Wall Street had come to expect, he needed something bigger—something that could move the needle fast.

He found it in St. Paul, Minnesota, at a company called Green Tree Financial.

For investors, the Conseco run of the 1990s leaves a lesson that keeps repeating across industries: acquisition-fueled growth can look brilliant for years—right up until the moment it doesn’t. The metrics that matter most—underwriting quality, integration reality, cultural fit—tend to show up late. And when they finally do, the game is usually already over.

The Fall: Green Tree, Subprime, and Spectacular Collapse (1998–2002)

The Green Tree Financial deal is the moment Conseco stopped being an aggressive insurance consolidator and started becoming a cautionary tale.

In 1998, Conseco agreed to buy Green Tree for about $7.6 billion, pending shareholder and federal regulatory approval. Green Tree, founded in 1975, had built itself into the nation’s largest lender in manufactured housing—mobile homes—originating and servicing manufactured-housing loans, consumer loans, and first and second lien residential mortgages.

On paper, you can see why Hilbert talked himself into it. Conseco already sold insurance to middle-income America. Green Tree lent to middle-income America. The late-90s obsession was “financial services diversification.” Stitch it together, cross-sell, and keep the growth story alive.

The market wasn’t buying it. Conseco shares dropped nearly 15 percent the day the deal was announced—a rare, immediate vote of no confidence. Wall Street saw problems that Hilbert either couldn’t see or didn’t want to.

Start with the most basic issue: this wasn’t Conseco’s business. As one observer put it, it was an acquisition completely outside Conseco’s expertise. There was little real synergy with the insurance operations, and Hilbert paid too much for the privilege of learning that lesson.

Then there was the risk embedded in what Green Tree actually was. This was subprime-adjacent lending before “subprime” became a household word. Green Tree was later renamed Conseco Finance, and Hilbert found himself prominent in high-risk residential lending years before the 2008 crash made that entire world infamous.

And then came the accounting. In 1999, Conseco and Conseco Finance made materially false and misleading statements about earnings in Commission filings and in public releases, overstating results by hundreds of millions of dollars. According to allegations, much of the overstatement traced back to a fraudulent accounting scheme designed to avoid writing down the value of certain securities held by Conseco Finance.

Even if the accounting had been pristine, the underlying market was turning. Manufactured housing was already wobbling. Defaults climbed as conditions softened and values fell. Within a year, Green Tree needed an additional $1 billion investment—exactly the kind of “just one more” cash infusion that shows up right before a balance sheet snaps.

After that, the unraveling wasn’t gradual. It was violent.

The Green Tree deal became the watershed event that turned Conseco into a company trapped under debt. The acquisition left it as a debt-burdened shell that couldn’t shake roughly $6.5 billion of obligations tied to the financing business.

By April 2000, earnings fell far below expectations. Debt climbed to about $8.2 billion. Hilbert and CFO Rolland Dick resigned under pressure. In 2000, with losses at Conseco Finance mounting, Hilbert was forced out.

The board went shopping for a grown-up.

They hired Gary Wendt, a famous cost-cutter from GE Capital, to try to engineer a turnaround. He took control in June 2000 and rolled out restructuring plans. Over the next two years, he managed to cut debt by about $2 billion—real progress, but nowhere near enough to outrun the damage. In October 2002, Wendt resigned as CEO, though he stayed on the board, while restructuring talks with creditors dragged on.

Even the rescue attempt carried the stink of the old Conseco culture. Investors fumed over Wendt’s $45 million signing bonus. The company was asking for patience and sacrifice while still paying like it was 1999.

By late 2002, the math finally won. In November, the company posted quarterly losses of $1.8 billion. In December, Conseco filed for Chapter 11—at the time, the third-largest corporate bankruptcy in U.S. history. It had collapsed under the debt load created by its 1990s acquisition spree, with Green Tree at the center.

The human cost was brutal. Thousands lost their jobs. Shareholders were wiped out. Policyholders—who buy insurance for certainty—were left wondering whether their coverage would still be there. Hilbert’s life visibly downsized too: his 23,000-square-foot French-style mansion, set on 40 acres and featuring a full-size replica of Indiana University’s Assembly Hall basketball court, went on the market for $20 million in July and didn’t sell.

One detail mattered enormously for what came next: the bankruptcy filing did not include Conseco’s insurance operations. Regulators and the company insisted those units were sound. And they were. That separation would prove crucial, because it meant there was something left worth saving.

For investors, Green Tree is the cleanest illustration of how diversification destroys value when it drags a company outside its circle of competence. The subprime crisis of 2008 didn’t come from nowhere. In a smaller, earlier form, this movie had already played—right here in Carmel, Indiana.

Emergence from Bankruptcy: The Cleanup Begins (2003–2008)

Bankruptcy is often described as a reset button. In Conseco’s case, it was more like a forced detox. The go-go, growth-at-all-costs culture had finally run into a hard constraint: reality. And Chapter 11, as traumatic as it was, imposed the discipline the company had avoided for years.

In September 2003, Conseco emerged from Chapter 11 with a radically reshaped balance sheet and—most importantly—without Green Tree. The company announced that its sixth amended joint plan of reorganization, confirmed by the U.S. Bankruptcy Court, had become effective. William J. Shea, Conseco’s president and CEO, tried to draw a bright line between the old Conseco and the new one: “We are very pleased to announce that Conseco has emerged from bankruptcy court protection as a financially stable company now totally focused on the insurance business.”

Green Tree was gone. The finance detour had been cut away. What remained was the part of the house that had never been the problem in the first place: the insurance operations.

Shea also emphasized the speed of the restructuring, calling the completion of such a large and complex process in less than nine months “truly a remarkable achievement.” And it was. But the harder part wasn’t getting out of court. It was earning back the one asset an insurer can’t buy with a reorg plan: trust.

The new management team didn’t look anything like the Hilbert era. These were operators, not deal-makers, and their mandate was brutally simple: keep the insurance businesses stable, rebuild confidence with agents and policyholders, and get the debt down. No grand reinvention. No transformational acquisitions. Just boring competence, applied day after day.

From 2003 through 2007, the progress was real—but it wasn’t pretty and it wasn’t fast. The company emerged, stumbling, and there was executive turnover along the way. Jim Prieur arrived in 2006, and a few months later he tapped Ed Bonach. The marching orders were clear: cut the holding company’s risk and refocus the businesses that were doing okay—Bankers Life, Washington National, and Colonial Penn—on middle-income Americans at or near retirement.

That focus mattered, because those core franchises had never been fundamentally broken. They still had customers. They still had distribution. They still knew how to price and service policies. The “cancer,” as many inside and outside the company saw it, had been the finance subsidiary—and it had been amputated.

As the cleanup continued, the playbook stayed consistent: divest non-core pieces, strengthen capital, tighten operations. It wasn’t glamorous, but it was the work that actually changes outcomes in insurance.

And when a business with real underlying cash flow gets left for dead, private equity tends to notice. Investors began accumulating positions, betting that the public markets were overcorrecting—pricing the company as if the insurance engine was as broken as the brand. The thesis was straightforward: if you can keep the core stable and stop doing reckless things, time starts working for you again.

One sign of how badly the old name had been contaminated came later, when the board officially approved changing the holding company’s name to CNO Financial Group on May 11, 2010. The rebrand was an attempt to outrun the Conseco stigma—a name that, to many, had become synonymous with corporate failure.

But even before the name change, the next test arrived. And it was the kind that doesn’t care whether you’ve already paid for your sins.

Then came 2008. Just as the company was getting its legs under it, the global financial crisis threatened to knock it right back into the grave.

By early 2009, executives—including then-CEO Jim Prieur and then-CFO Ed Bonach—were backed into a corner. Analysts projected the company needed roughly $400 million over the following year to stay afloat. The stock was trading around 30 cents a share, borrowing capacity was already tight, and the options were limited for a company that had been in bankruptcy only six years earlier.

The crisis hit CNO from both directions at once. On one side, the value of the assets it held in financial markets dropped, pressuring the capital cushion it could rely on in a pinch. On the other, bond ratings were downgraded along with other insurers’, which tightened covenants—especially around debt-to-capital ratios. The combination pushed CNO uncomfortably close to covenant breaches in early 2009, and the company’s auditor issued the dreaded “going concern” warning.

Bonach later described what it felt like to have to go to markets under those conditions: “We were negotiating with lenders and investors like Paulson from a position of weakness. It’s a nightmare to have to face that perfect storm of events that you have to try to navigate through quickly and efficiently.”

And yet—somehow—they navigated it. CNO avoided a second trip through bankruptcy. The company that came out the other side increasingly looked like the opposite of old Conseco: less flash, less leverage, fewer grand declarations—more discipline.

The crisis was terrifying in the moment, but it also burned the lessons into the culture. After surviving two near-death experiences in less than a decade, CNO internalized what insurance companies are supposed to believe in the first place: risk management, conservative capital, and boring, predictable operations.

For investors, the lesson of this era is almost unsatisfying—because it isn’t clever. From 2003 through the financial crisis, the “new” CNO created value the old-fashioned way: by running the core insurance businesses competently, shrinking risk, and grinding down debt. No financial engineering. Just the slow work of becoming survivable again.

The Ed Bonach Era: Steady Hands (2009–2016)

Ed Bonach was exactly the kind of CEO CNO needed when it was still wobbling from the crisis. He’d joined the company as CFO in 2007 after serving as CFO at National Life Group. Before that, he spent more than two decades at Allianz Life Insurance Company of North America, including senior roles like President of the Reinsurance Division and Chief Financial Officer.

In other words: not a swashbuckling empire-builder. Bonach was a career insurance and capital-markets operator—someone fluent in reserves, credit ratings, and the unsexy mechanics of staying solvent. And after bankruptcy and a brush with a second collapse, CNO didn’t need vision. It needed discipline.

Years later, as he reflected on his time at the company, Bonach put it simply: “It’s been an incredible privilege and honor to serve this great company… and work with the many talented leaders, associates and agents who successfully serve the needs of our customers every day.”

The strategy that followed the crisis was straightforward and, by design, unexciting. Four pillars defined the Bonach era.

First: conservative underwriting. No reaching for growth by loosening standards.

Second: balance sheet repair—reducing debt, building capital, and operating with the memory of 2008 still fresh.

Third: focus on what actually worked. Bankers Life had a real franchise with middle-income seniors, and CNO leaned into that instead of chasing the next shiny thing.

Fourth: no heroics. No transformative acquisitions. No “financial services supermarket” fantasies. Just steady execution.

And then came the cleanup—the part that didn’t make headlines but mattered most. The company still carried legacy blocks from the Conseco days: old products it wasn’t selling anymore, but still had to manage, reserve for, and explain to skeptical investors. Many of those blocks were volatile and sensitive to interest rates. They were a drag on confidence, even when the core operating businesses were performing.

Bonach’s tenure became defined by getting that baggage off the books.

CNO started by unloading about $550 million of an old block of long-term care business to a reinsurer. But the bigger step was selling Conseco Life Insurance Co. That business lost $5.1 million in 2013, and CNO held $3.4 billion in reserves against it. Moving it out wasn’t just a transaction—it was a symbolic break from the name and the risks that still haunted the company.

As CNO divested and ran off these legacy pieces, the numbers told the story. After the sale of Conseco Life, CNO’s reserves dedicated to legacy business dropped from about $5 billion to $961 million. The company stopped reporting the old Conseco business as a segment. The exorcism was happening faster than many observers expected. “We’re able to now finally focus going forward on our core business,” Bonach said. “We’re pleased with our progress in that relatively short period of time.”

What’s striking about the Bonach years isn’t explosive growth—it’s consistency.

From 2011, when Bonach became CEO, CNO didn’t put up much top-line expansion. Revenue was $4.125 billion in 2011 and slipped to $3.985 billion by 2016. But earnings per share moved the other direction, rising from 75 cents in 2011 to $1.34 in 2016.

That’s the signature of a turnaround maturing: the surface looks flat, but the engine underneath is getting cleaner and more efficient. Revenue drifted down, while profitability improved and value per share rose.

A big part of that was capital return. CNO leaned hard into buybacks, repurchasing $845 million of stock since 2011, including $31 million in the fourth quarter mentioned. It wasn’t trying to convince investors it was a growth story again. It was treating itself like what it was becoming: a cash-generating insurer that could shrink its share count and increase each remaining shareholder’s claim on the business.

The other long-running mission was credibility in the debt markets. Ever since emerging from bankruptcy in 2003, CNO had been chasing investment-grade status. By this period, it was getting close, helped by a drumbeat of ratings upgrades—10 upgrades since 2012. It was one notch away from investment grade at A.M. Best, S&P, and Fitch, and two notches away at Moody’s.

Those ratings would matter not because they were prestigious, but because they were practical—lower borrowing costs, better flexibility, and a clearer signal that the company had truly left the Conseco era behind.

When Bonach prepared to step down, board chairman Neal Schneider summarized the internal view of what had been accomplished: “He has successfully increased shareholder value, delivered strong profitability, and has been unwavering in his commitment for CNO to be the leader in meeting the needs of middle-income Americans for financial security and readiness for the life of their retirement. He’s leaving CNO a strong, thriving, focused and profitable insurance enterprise.”

From an investor’s lens, the Bonach era is a reminder that some of the best compounding doesn’t come from dramatic reinvention. It comes from refusing to blow up, cleaning up what’s broken, and running the core business better every year—while returning cash along the way.

The Gary Bhojwani Transformation: Modernization & Digital (2017–2022)

By the time Ed Bonach handed over the keys, CNO had done something that once seemed impossible: it had made itself stable. The question was what to do with that stability.

Enter Gary C. Bhojwani. He became CEO of CNO Financial Group on January 1, 2018, after serving as president from April 2016 through December 2017. He joined the board in May 2017 and served on its Executive and Investment Committees.

Bhojwani wasn’t a return to the Hilbert-era appetite for spectacle. But he did represent a shift in posture: CNO had spent a decade shrinking risk and proving it could survive. Now it needed to prove it could evolve.

His resume signaled exactly where he wanted to push. He’d been CEO of Allianz Life Insurance Company of North America from 2007 to 2012 and later served on the Board of Management of Allianz SE from 2012 to 2015. Before that, he was president of Commercial Business at Fireman’s Fund Insurance Company from 2004 to 2007, with earlier experience at McKinsey & Company, Allianz SE, and Allianz of America. He held an MBA in Finance and Marketing from the University of Chicago Booth School of Business.

When he took the top job, his message was optimistic—but aimed squarely at the market CNO had bet its life on:

"I strongly believe that CNO is uniquely qualified to meet the needs of the middle-income market, our people are extremely talented, and our future is bright. I look forward to working closely with our leaders, associates, agents and our Board to successfully deliver on our strategy to meet the needs and expectations of our customers, our shareholders, and our communities."

The strategic inflection was simple: demographics and distribution were changing, whether CNO liked it or not. Bankers Life’s career-agent model—so central to the company’s identity—was aging. Agent counts were declining. Younger agents weren’t lining up for a commission-only career. And customers were increasingly expecting digital-first interactions as the default, not the exception.

So Bhojwani started rewiring the org chart to match the world CNO was heading into.

CNO announced a new operating model, moving from three operating business segments to two divisions: Consumer and Worksite. The promise was a leaner, more integrated, more customer-centric company. Bhojwani framed it in plain terms: "CNO is transforming its organizational structure to build a leaner, more agile company. Consumer purchasing behaviors are rapidly changing across all industries, including insurance."

If Consumer was about modernizing how CNO sold to individuals, Worksite was about changing where it showed up. Instead of relying primarily on one-on-one sales to retirees and near-retirees, CNO pushed harder into reaching people through their employers.

That push took a concrete shape with the introduction of Optavise, the new brand for CNO’s Worksite offerings. Optavise positioned itself as a comprehensive provider of employee benefits solutions, intended to help employers and employees make better health and financial decisions. It combined three existing worksite brands under one go-to-market banner: PMA Worksite Marketing Division’s career agent network, DirectPath (its benefits education and advocacy services provider), and Web Benefits Design (its benefits administration technology provider). Optavise agents continued to sell Washington National voluntary benefits and supplemental insurance products.

Bhojwani described the logic: "With the launch of the Optavise brand, CNO is taking the next strategic step in building our Worksite capabilities. Our acquisitions over the past three years enhanced the competitiveness and attractiveness of our Worksite business. By uniting our people, technology and products under a single go-to-market brand, we've created a comprehensive employee benefits solution that is unique in our market."

One of the key building blocks was DirectPath, which CNO acquired in early 2021. The deal added benefits education and advocacy services—an important capability if you want to be more than just the carrier behind a policy and instead become part of an employer’s benefits infrastructure.

Then COVID-19 hit, and it forced the issue.

In-person selling—still central to much of insurance—was suddenly constrained. But the upside of a crisis like that is clarity: things that were “optional” become mandatory overnight. Remote selling accelerated. Video meetings became normal. Customers got more comfortable buying without sitting at a kitchen table. The future Bhojwani was steering toward arrived early.

Under the new setup, the Consumer Division served individual consumers through phone, online, face-to-face with agents, or a blend of channels—bringing together CNO’s agent forces with its direct-to-consumer business, including advertising, web and digital capabilities, and call center support. The Worksite Division focused on worksite and group sales for businesses, associations, and other membership groups, meeting customers at their place of employment.

The transformation was also meant to take cost out of the system. The initiatives were expected to reduce gross annual run-rate spending by approximately $22 million by the end of 2020.

The results during the Bhojwani years were the kind you’d expect from an insurer modernizing mid-flight: improved margins and returns, but still modest growth. And, perhaps most symbolically, CNO finally reached a milestone it had been chasing since the early 2000s: it became investment grade with all four major ratings agencies—AM Best, Moody’s, Fitch, and S&P.

That mattered because it marked the end of the “will they make it?” era. The company that had once been defined by bankruptcy and close calls had re-established itself as a financially secure insurer.

For investors, the Bhojwani era shows how hard transformation really is when you’re already alive again. The strategy was clear: distribution was changing, so CNO had to change with it. But execution is brutally difficult when the legacy model still generates most of the profits. It’s the innovator’s dilemma—except instead of smartphones and software, it’s agents, call centers, and the slow-moving machinery of insurance.

The Current Era: Recent Performance & Strategic Questions (2023–Present)

By the early 2020s, the question wasn’t whether CNO could survive anymore. It was whether it could finally look like a modern insurer—one that could grow without leaning on the same old levers that nearly broke it.

The headlines, at least, have been encouraging.

For the fourth quarter of 2024, CNO reported net income of $166.1 million, or $1.58 per diluted share, up from $36.3 million, or $0.32 per diluted share, in the fourth quarter of 2023. For the full year 2024, net income was $404.0 million, or $3.74 per diluted share, compared to $276.5 million, or $2.40 per diluted share, in 2023.

Revenue rose too. In 2024, CNO generated $4.45 billion, up from $4.15 billion the year before.

Management framed it as more than a one-off bounce. They pointed to 10 consecutive quarters of sales growth, strong agent-force metrics, and what they called one of the company’s best operating performances in years—highlighted by production records across both divisions. They also emphasized that operating earnings per share, excluding significant items, grew sharply for both the quarter and the year, driven by underwriting margins, net investment income, and disciplined expense and capital management.

Profitability metrics moved in the right direction as well. Return on equity was 16.4% in 2024 versus 14.0% in 2023. Operating return on equity, excluding significant items, was 11.4% in 2024 versus 8.6% in 2023.

Then there’s the part shareholders care about most: cash coming back.

CNO returned $349.3 million to shareholders in 2024, up 50% from 2023. In the fourth quarter alone, it returned $108.0 million. Over the past 10 years, the company has returned $3.0 billion to shareholders.

Looking ahead, CNO’s 2025 guidance signaled confidence: expected operating EPS of $3.70–$3.90, with an expense ratio of 19.0%–19.2% and an effective tax rate of approximately 23%.

On paper, the balance sheet looked steady, too. The consolidated RBC ratio was 378% versus a target of approximately 375%. Holding company liquidity was $187 million, above its $150 million minimum target. And the debt-to-capital ratio was 26.1%, within the company’s 25%–28% target range.

But in CNO’s story, the numbers are never the whole story—because the real plot is distribution.

The distribution dilemma remains the company’s central strategic challenge. Career agent counts have been pressured for years, and even with efforts to stabilize and grow the force, the long-term trajectory of face-to-face insurance distribution is still uncertain.

That’s why Worksite matters so much. Optavise now operates nationwide through a network of 10,000 broker partners and more than 600 dedicated agents, serving nearly 20,000 businesses and employers. CNO has been clear that this channel is becoming the growth engine, pointing to four consecutive quarters of sales momentum, increased agent counts, and record growth across multiple product categories—evidence, in their view, that the distribution mix is getting healthier.

In the market, CNO still sits in that “quiet compounder” zone: a market cap of approximately $3.79 billion, about 95.35 million shares outstanding, a dividend yield of 1.71%, and a P/E ratio of 13.90, with trailing twelve-month revenue of $4.506 billion.

So the question for investors in 2025 isn’t whether CNO can post a good year. It’s whether the recent strength is a durable step-change, or a period of help from the environment. Higher interest rates have lifted investment income. Agent recruitment has improved. The worksite push is gaining traction.

The hard part is the next part: can CNO keep that momentum when conditions get less friendly—and can it keep evolving fast enough to stay relevant in how insurance is actually bought?

The Business Model Deep Dive: How CNO Actually Makes Money

To understand CNO, you have to understand the brands underneath it—and, more importantly, the distribution engines attached to each one. This is not a company built around a breakthrough product. It’s built around multiple ways of getting fairly simple insurance products into the hands of people who actually need them.

Start with Bankers Life.

Bankers Life markets and distributes Medicare supplement insurance, interest-sensitive life insurance, traditional life insurance, fixed annuities, and long-term care insurance products to the middle-income senior market. It does it the old-fashioned way: through a dedicated field force of career agents and sales managers, supported by a network of community-based branch offices.

This is the heart of CNO’s Consumer Division. Bankers Life agents work out of those local offices and meet clients primarily in their homes. It’s high-touch and relationship-driven, which fits the senior market, where trust is often the product.

Next is Colonial Penn, which is almost the opposite.

For more than 60 years, Colonial Penn has specialized in offering life insurance directly to consumers. Through the mail, TV, the call center, and the web, it focuses on providing life insurance protection for older Americans and their families. It was also an early pioneer in designing products for the mature market, and in 1968 became one of the first insurers to offer a Guaranteed Acceptance Life Insurance plan exclusively for people age 50 and over.

This is the side of CNO you’ve probably seen: the direct-to-consumer ads, including the famous “$9.95 a month” pitch. The products are simplified-issue—generally no medical exam—which makes them easier to buy. The unit economics look different than an agent-sold policy: lower margin per policy, but a model that can scale through marketing and a centralized call center.

Then there’s Washington National.

Washington National is a leading provider of supplemental health and life insurance for middle-income Americans in both the worksite and individual markets. Think cancer insurance, accident coverage, and hospital indemnity—products meant to cover the gaps that traditional health insurance leaves behind. It sells both to individuals and via worksite enrollment, where employees can opt in through their employer.

And finally, Optavise—the Worksite “wrapper.”

Optavise provides personalized employee benefits solutions designed to help employers and their employees optimize benefits and make better health and financial decisions. In practice, it’s part services business, part distribution platform: benefits administration, education, and enrollment support that helps Washington National products get adopted inside workplaces.

Through 2024, the Consumer Division (Bankers Life plus Colonial Penn) has generated roughly 65–75% of collected premiums and operating earnings, anchored by life, Medicare Supplement, and fixed annuities. Worksite (Washington National and Optavise) provides the remainder, with growing fee-income as the platform expands.

Once you know the brands and channels, the economics are the familiar insurance flywheel.

First is pricing discipline: charging premiums that actually reflect the claims the company expects to pay.

Second is persistency: keeping policies in force long enough to earn back the high upfront costs of acquiring customers, whether that’s an agent commission or a marketing and call-center funnel.

Third is investment income: earning returns on the float between premium collection and claims payment.

You can see that dynamic in the recent environment. Yield on the general account supports reserves and capital, and net investment income rose in 2023–2024 as reinvestment yields improved with market rates. In annuities, profitability is heavily influenced by the spread between what the portfolio earns and what CNO credits to policyholders. And for fixed indexed annuities, the option budget helps deliver index-linked crediting while protecting principal.

All of this only works because of who CNO sells to.

The middle-income market deserves its own spotlight, because it’s the reason this company exists—and the reason it’s hard to replicate cleanly. These are customers who often have real gaps in coverage, sometimes lack robust employer-sponsored options, and typically don’t have the assets to attract a high-end advisor. They still need protection, but they need it delivered in a way that fits their lives and budgets.

CNO meets them where they are: across a kitchen table with a Bankers Life agent, through a worksite enrollment meeting, or through a Colonial Penn commercial that catches someone at exactly the moment they’re worried about leaving their family exposed.

That’s the differentiation in plain terms: serve the middle market with simplified underwriting, human advice for modest-ticket policies, and worksite enrollment capabilities. The advantage, to the extent there is one, comes less from product innovation and more from distribution and the ability to keep customers on the books.

For investors, that combination tends to produce predictable cash flows—but it also caps the story. The middle-income market is large, but it doesn’t expand quickly. Competition is real, even if fragmented. And the moat, such as it is, lives in distribution relationships and execution, not in patents or a beloved consumer brand.

Porter's 5 Forces Analysis

Competitive Rivalry—HIGH

CNO lives in one of the most crowded arenas in finance. It competes with giants like MetLife and Prudential—companies with budgets and balance sheets that make CNO look small—as well as specialists like Globe Life and Aflac that know the same middle-market customer just as well.

In early 2025, the competitive set around CNO included names like Aflac, Assurant, Ameriprise Financial, Equitable, Old Republic International, Principal Financial Group, Radian Group, and Unum Group.

And scale matters here. CNO’s market cap has been around the $4 billion range, while much larger insurers can invest in technology, advertising, and compliance and then spread those fixed costs across vastly bigger books of business. That makes it harder for CNO to win a straight spending contest.

Worse, the products themselves are often close to interchangeable. A Medicare supplement policy is a Medicare supplement policy. If customers can’t tell the difference on paper, competition turns into a battle of price, service, and—most importantly—distribution. Who can reach the customer first, explain it clearly, and keep them happy afterward?

Threat of New Entrants—MEDIUM

Insurance isn’t a “two people in a garage” business. Regulation and capital requirements are real barriers. You need licenses, you need reserves, and you need to satisfy state regulators who exist specifically to make sure insurers don’t take reckless risks.

But the internet has changed what “entry” looks like. Digital-first players like Haven Life, Ethos, and Bestow have chipped away at the old advantages by focusing on simplified products with streamlined underwriting, sold online. They don’t need a sprawling agent network or a dense branch footprint to get started.

Still, the hardest thing to replicate isn’t the policy form—it’s distribution. Building a career agent force or embedding yourself in worksite relationships takes time, trust, and years of execution. A new entrant can launch a product quickly. Building a durable sales channel is the long game.

Supplier Power—LOW

Insurance doesn’t have suppliers in the classic manufacturing sense. The closest analogue is reinsurance—outsourcing some risk to reinsurers—but the global reinsurance market is deep and competitive, with plenty of capacity from multiple major players.

Agents matter too, but no single company controls them. Recruiting is competitive, yet the “supply” of potential producers isn’t owned by any one insurer.

Buyer Power—MEDIUM-HIGH

CNO’s customers are value-conscious, and that shapes everything. Middle-income households tend to shop carefully, and comparison tools have made it easier to see competing offers side by side.

But there’s a counterweight: once someone has a policy, switching can be a headache. It can mean new underwriting questions, new health disclosures, and the simple emotional friction of changing something tied to security. When there’s a trusted agent relationship, that inertia gets even stronger.

And in annuities, the switching costs aren’t just psychological. They’re often contractual, through surrender charges that penalize early exits.

Threat of Substitutes—MEDIUM

The substitute for insurance is, in theory, self-insurance: save more, build an emergency fund, cover expenses yourself. For some needs, government programs can also substitute—Medicare and Medicaid being the obvious examples.

The longer-term risk is cultural. Younger generations may be less inclined to buy traditional policies or may prefer different buying experiences than their parents.

And technology keeps widening the menu of alternatives. New models—like peer-to-peer insurance concepts or parametric products—haven’t replaced mainstream life and supplemental health yet, but they’re reminders that “insurance” as a category isn’t frozen in time.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies—WEAK

CNO is simply smaller than the giants it competes with. With a market cap around $3.9 billion versus MetLife at roughly $54.1 billion, it can’t spread technology, compliance, and corporate overhead across anywhere near the same premium base. There is some leverage in shared systems and centralized functions, but CNO doesn’t have the kind of scale that becomes a built-in advantage.

Network Effects—MINIMAL

Insurance doesn’t get stronger because more people use it, the way a marketplace or a social network does. The closest thing CNO has to a network effect is its agent organizations—shared training, shared playbooks, and culture—but those “networks” are fragile. Attrition is always pulling in the other direction.

Counter-Positioning—MODERATE

CNO’s focus on middle-income America does create a different operating model than high-net-worth-oriented financial firms. Simplified products and community-based distribution fit customers who don’t need bespoke planning or complex structures. It’s not a business Morgan Stanley Wealth Management would naturally want to run.

The catch is that this positioning cuts both ways. Digital-first insurers can counter-position against CNO too, marketing a lower-cost, online-first experience that makes an agent-heavy model look expensive and slow.

Switching Costs—MODERATE-STRONG

Once someone has an insurance policy, switching isn’t frictionless. Underwriting requirements and health questions can make changing carriers inconvenient—or impossible at an attractive price. Add a trusted agent relationship and you get real inertia.

In annuities, the switching costs are even more concrete: surrender charges create contractual penalties for leaving. And for life insurance, policies with accumulated cash value tend to get stickier over time, especially as policyholders age.

Branding—WEAK

As a holding company name, CNO has little consumer pull. The brands that matter are the subsidiaries—Bankers Life and Colonial Penn—which have pockets of recognition but not the kind of national, aspirational branding you see in the biggest consumer finance franchises.

And the old Conseco bankruptcy still casts a long shadow. Many customers today won’t remember it, but in parts of the market the institutional memory hasn’t fully faded. That said, the middle-income segment typically isn’t shopping based on corporate brand prestige anyway. Price, simplicity, and the person selling the policy usually matter more.

Cornered Resource—WEAK

CNO doesn’t have a truly “cornered” asset—no proprietary distribution channel, breakthrough underwriting technology, or unique product structure that competitors can’t chase. Its agent networks are meaningful, but they’re not exclusive, and they can be rebuilt by others over time.

Process Power—MODERATE

There is real value in doing insurance well for a long time: underwriting data, actuarial muscle memory, and the operational habit of managing risk. CNO’s post-bankruptcy culture—conservative, ratings-aware, and capital-disciplined—counts as a form of institutional advantage.

But it’s not a fortress. Well-capitalized competitors can hire talent, buy systems, and replicate “best practices” if they decide the market is worth the push.

Summary: CNO’s defensibility is real but limited. Switching costs and process discipline help. Still, there’s no dominant structural advantage here—meaning the outcome hinges on execution, distribution evolution, and capital allocation.

The Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

The CNO story is a reminder that some companies don’t win by being the smartest in the room. They win by surviving long enough to become disciplined.

Survival lessons: Near-death experiences can create stronger businesses, but only if the company treats the crisis as a forced reset—not a temporary storm to wait out. CNO’s post-bankruptcy discipline wasn’t a branding exercise. It was learned the hard way, through real consequences.

The importance of culture change: The biggest shift wasn’t a product launch or a new market. It was the move from Hilbert’s growth-at-all-costs posture to Bonach’s operating-first, capital-first mentality. You can see it in the choices: fewer headline-grabbing moves, more focus on risk, ratings, reserves, and repeatable execution.

Distribution is destiny: In insurance, the channel is often the strategy. CNO’s three main distribution engines—Bankers Life’s career agents, Colonial Penn’s direct-to-consumer machine, and Optavise’s worksite platform—aren’t just go-to-market options. They define what kinds of customers you can reach, what kind of economics you can earn, and how resilient you are when the world changes.

The unglamorous compound: There’s a version of business success that never makes the cover of a magazine. CNO didn’t reinvent insurance. It didn’t build a cult brand. It just ran the core business steadily, improved profitability, and returned cash to shareholders. Sometimes that’s the whole edge.

Know your customer: Middle-income America is a huge market, but it’s not an easy one. It’s price-sensitive, often needs explanation and reassurance, and tends to buy smaller policies that don’t leave much room for waste. CNO built around that reality. Many companies say they serve “the middle market.” Far fewer can do it profitably.

Capital allocation after crisis: The slow work—paying down debt, strengthening capital, and fighting back to investment-grade ratings—created flexibility that the old Conseco never had. Optionality is what you earn when you stop trying to impress the market and start trying to be unkillable.

Technology as enabler, not silver bullet: CNO’s modernization push reflects a practical truth: in this category, technology helps sell and service, but it rarely replaces trust overnight. The company invested in digital tools and worksite infrastructure while still leaning on human distribution where it remains effective.

Bear vs. Bull Case & Investment Considerations

The Bull Case

Secular demand: America is aging, and that’s not a subtle trend. Roughly ten thousand baby boomers turn 65 every day. More retirees means more pressure from healthcare costs, longevity risk, and retirement insecurity—the exact set of anxieties CNO’s products are built around.

Undervalued: For a business that’s stabilized, gone investment grade, and now reliably generates cash, the stock still trades at a valuation that suggests skepticism. In early 2025, CNO’s P/E has sat in the mid-teens—below many peers and well below the broader market. If investors ever decide it deserves to trade more like a “normal” insurer, there’s room for upside even without heroic growth.

Cash generation: This is the appeal of the rebuilt CNO: it generates cash, and it gives it back. Management said its capital position and free cash flow generation remained robust while returning $349 million to shareholders in 2024—up 50% from 2023. In a slow-growth industry, that kind of capital return can be the whole story.

Execution improvements: The company has pointed to a real operational streak—10 consecutive quarters of sales growth—and described 2024 as one of its best operating performances in years, with production records across both divisions. If that’s more than a temporary tailwind, it’s the clearest signal that the turnaround has shifted into a sustainable operating rhythm.

Market inefficiency: CNO sits in an awkward investing no-man’s land. It’s not big enough to be a core position for many institutions, and it’s not exciting enough for growth investors. That neglect can create mispricing—especially when the business is quietly doing the right things.

Balance sheet repair: The company is now investment grade across AM Best, Moody’s, Fitch, and S&P. After everything in this story, that matters less as a badge and more as a permission slip: lower funding costs, more flexibility, and far less “existential risk” priced into the equity.

The Bear Case

Secular decline: The career-agent model is under pressure across the industry. If CNO can’t keep replenishing the agent force—or can’t shift enough growth into Worksite and other modern channels—it risks becoming the classic melting ice cube: still profitable, still paying dividends, but slowly shrinking.

Competitive pressure: The giants have scale and budgets CNO can’t match. And digital-native insurers can iterate faster on customer experience and acquisition. CNO doesn’t have to win a tech arms race—but it does have to avoid falling behind in how customers expect to buy.

Product commoditization: In supplemental health and life, it’s easy for products to look similar on paper. As shopping and comparison get easier, pricing pressure shows up fast, and margins can get squeezed unless distribution and service create real differentiation.

Demographic risk: CNO serves middle-income households—the customers who feel inflation, housing costs, and healthcare expenses most sharply. When budgets tighten, insurance premiums compete with everything else. That can mean slower sales and more lapses.

Regulatory/political risk: Insurance is always one legislative or regulatory shift away from a different playing field. Medicare-related markets can change. Rate regulation can compress margins. And political uncertainty is a persistent background risk for health-adjacent products.

No moat: The competitive advantage here isn’t structural dominance—it’s execution. As the 7 Powers analysis suggests, CNO doesn’t have an unassailable moat. That’s fine when management is running well, but it leaves less margin for error.

Reputation hangover: The Conseco collapse is old history, but not ancient history. In some corners of the market, institutional memory lingers—especially among agents and customers who lived through it. Trust is everything in insurance, and CNO has had to earn it the hard way.

Low growth: Even in the bull case, this is not a rocket ship. It’s likely a low-single-digit grower in mature categories. If you need rapid expansion, this probably isn’t your stock.

Key Metrics to Watch

If you want to monitor whether the story is getting better or worse, keep it simple and focus on the leading indicators that tell you whether distribution is working.

Agent Count and Productivity: This is the heartbeat of the model—especially at Bankers Life. Growing agent counts suggest recruiting and retention are working. Improving productivity suggests training, tools, and the product mix are landing. If agent counts fall and productivity doesn’t offset it, that’s a warning sign.

New Annualized Premiums (NAP) Growth: NAP captures the annualized premium value of new business sold, which makes it a clean read on whether sales momentum is real. Sustained NAP growth tends to show up later as future earnings growth as policies season.

Secondary metrics worth tracking include persistency rates (how long policies stay in force), operating return on equity, and capital deployment—dividends, buybacks, and any M&A that changes the shape of the company.

Epilogue: What's Next for CNO?

CNO is at a familiar fork in the road—one it’s been approaching, in different forms, ever since it crawled out of Chapter 11.

One path is the public-company playbook: keep grinding out modest growth, keep the balance sheet conservative, and keep sending cash back through dividends and buybacks. It’s not flashy, but it’s worked—and it fits what CNO has become: a steady insurer with a real niche and a hard-earned allergy to existential risk.

The other path is more dramatic: a deeper transformation that might be easier to pull off away from the quarterly scoreboard. Private equity interest in insurance has surged in recent years, with firms like Apollo, KKR, and Blackstone buying insurers for their stable cash flows and investment portfolios. In that light, CNO’s predictable earnings and investment-grade profile are exactly the kind of thing financial sponsors tend to find attractive.

But even if the ownership structure never changes, the defining question for CNO’s next decade is still distribution.

Technology is reshaping how insurance gets bought, and the middle market is notoriously hard to serve efficiently. The challenge isn’t choosing between digital and human advice—it’s making them work together. Can CNO build a hybrid model where agents still provide trust and guidance, while digital tools lower acquisition costs, speed up underwriting, and improve service? Strategically, that’s the right answer. Operationally, it’s one of the hardest things in the business.

M&A is another lever, and it cuts both ways. CNO could play offense—buying smaller players, adding capabilities, or expanding in channels where it’s underweight. Or it could end up on the other side of the table, acquired by a larger insurer that wants its distribution footprint, its customer base, or simply a middle-market platform that’s already standing.

Then there’s the generational shift, which may be the most important variable of all. Bankers Life’s core customer has traditionally been at or near retirement. But Gen X and Millennials don’t behave like their parents, don’t buy the same way, and may not even want the same products. The open question is whether CNO can evolve what it sells—and how it sells it—without losing the economics that made the model work in the first place.

And, of course, there are wild cards. Regulatory change could reshape Medicare supplement markets quickly. A recession could squeeze middle-income households and push lapse rates higher. And somewhere out there, a startup may still find a cleaner, cheaper way to reach the exact customer CNO has spent decades trying to serve.

Zoom out far enough and CNO starts to look less like an insurance stock and more like a case study in resilience. This company lived through a rollup boom, a catastrophic detour, and a bankruptcy that should’ve been fatal. It rebuilt itself through disciplined operations, balance sheet repair, and an almost stubborn commitment to staying in its lane. Near-extinction turned into quiet compounding.

The bigger question goes beyond CNO: is there a sustainable, scalable business model for serving middle-income America’s insurance needs?

These customers matter, and they’re easy to ignore—too “small” for wealth management, too complex for pure self-service, and too exposed to economic shocks to be an effortless market. They still need protection. If CNO can’t deliver it profitably and responsibly, who will? The answer to that question may shape not just CNO’s future, but the financial security of millions of families.

Recommended Resources

If you want to go deeper—into CNO’s turnaround, how insurers actually make money, and why distribution matters so much—these are the best places to start:

CNO Financial Annual Reports & Investor Presentations (2003–present)—The story in management’s own words, straight from the filings and decks, available at CNOinc.com

SEC 10-K Filings—The unfiltered source for business segment details, risk factors, and the mechanics behind the numbers

Insurance industry reports from AM Best and S&P Global—Credit ratings context, competitive positioning, and how the industry views CNO’s balance sheet and risk profile

"The Outsiders" by William Thorndike—A great lens on capital allocation, and a useful framework for understanding why buybacks, dividends, and balance-sheet choices mattered so much in CNO’s post-bankruptcy era

"7 Powers" by Hamilton Helmer—A clear way to think about whether a company has durable advantage, and what “moats” look like in a business as unglamorous—and competitive—as insurance

Key Industry Publications to Follow:

- Insurance Journal

- National Underwriter

- AM Best News

- Insurance News Net

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music