Commerce.com Inc.: The Story of an Open SaaS E-commerce Pioneer

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

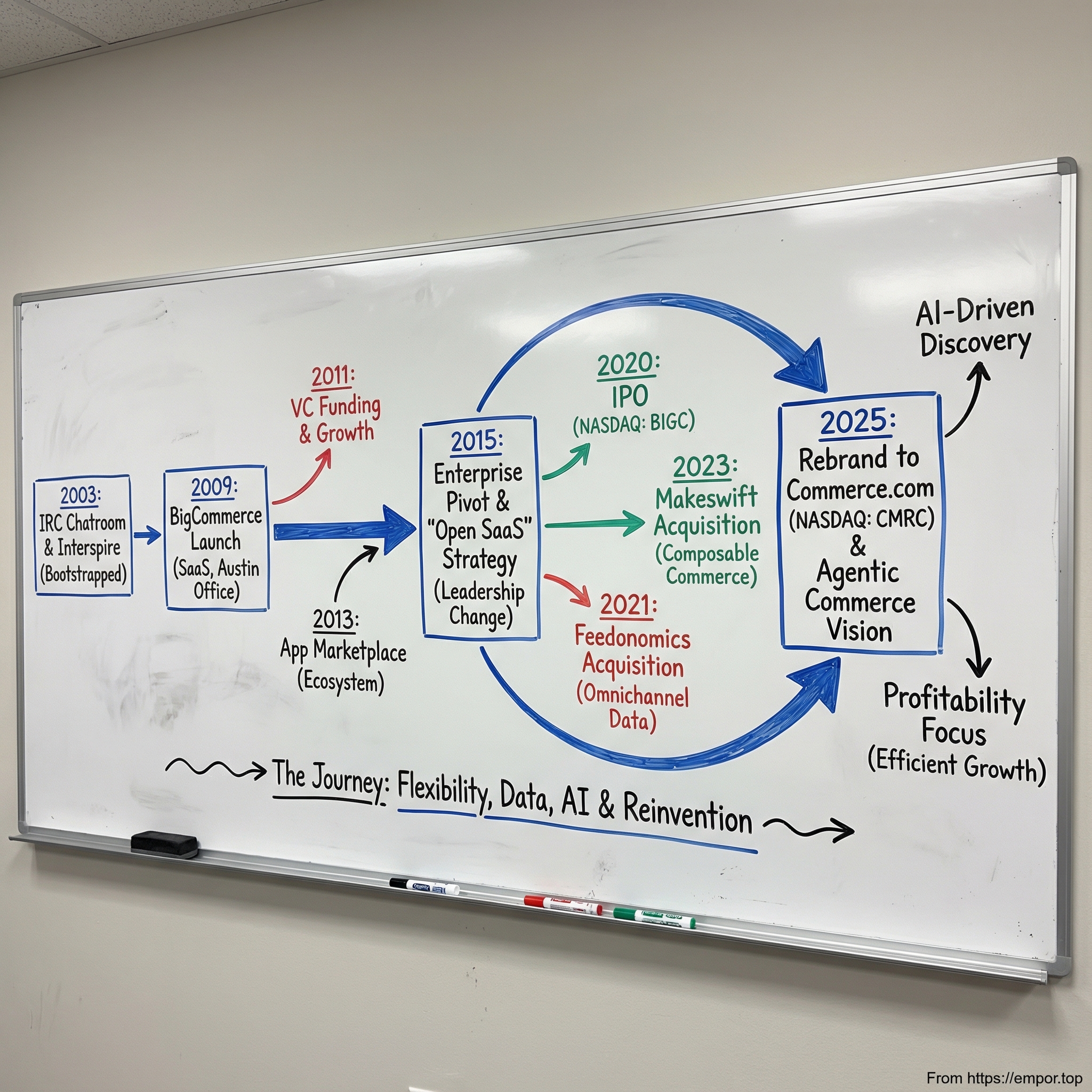

Late summer, 2025. In Austin, Texas, a company that’s spent sixteen years building the plumbing of online retail decides it’s time to change the sign on the building.

On July 31, 2025, BigCommerce officially became Commerce.com, Inc.—and with it, the NASDAQ ticker flipped from BIGC to CMRC. The announcement wasn’t just a logo swap. It introduced a new parent brand, Commerce, meant to bring BigCommerce, Feedonomics, and Makeswift under one roof—positioned as a single platform built for what the company calls the next era of “agentic commerce.”

That phrase matters, because it signals what this rebrand is really about: a belief that AI is going to reshape shopping from the top down. Not just better recommendations, but systems that can research, compare, and transact on a customer’s behalf. And in that world, Commerce.com is betting the advantage won’t go to whoever has the prettiest storefront—it’ll go to whoever has the cleanest product data, the most flexible architecture, and the infrastructure to plug into whatever new discovery channels emerge next.

Which brings us to the central tension: the problem every number-two player has to solve.

How do you build something enduring when the market leader isn’t just ahead—it’s Shopify-ahead? Years of momentum, an ecosystem advantage, and the kind of brand recognition that turns the company name into shorthand for the whole category.

Commerce.com’s answer has been to win differently. Instead of trying to out-Shopify Shopify, it has leaned into counter-positioning: “Open SaaS.” The pitch is simple, and brutally hard to execute—give mid-market and enterprise merchants the flexibility they want (APIs, integrations, composability) without forcing them into the complexity and maintenance headaches that often come with open-source.

And the company’s origin story fits that contrarian streak.

BigCommerce was founded in Sydney in 2009 by two Australians, Eddie Machaalani and Mitchell Harper, who first met in an online chatroom in 2003. A year later, they launched Interspire—the business that would eventually evolve into BigCommerce.

From a Sydney apartment to a NASDAQ listing to a 2025 rebrand that aims to define the next chapter of e-commerce, this is a story of bootstrapping, venture-scale ambition, reinvention under pressure, and a relentless attempt to become the enterprise-ready alternative in a world where Shopify dominates mindshare—but may not own every segment of the market.

II. The Founding Story: IRC Chatrooms to Interspire (2003-2009)

The origin story of BigCommerce doesn’t begin in a Stanford dorm room or a Silicon Valley garage. It begins in an IRC chatroom in 2003—one of those early-internet places where strangers showed up to solve problems, share code, and occasionally meet the person they’d build a company with.

Eddie Machaalani came up through the very unglamorous side of tech. In 2001 and 2002, he was working as a web designer, obsessed with a specific kind of customer: small businesses that didn’t have big budgets, but still needed to look credible online and grow. That focus wasn’t abstract. His parents had immigrated from Lebanon and found stability in Australia through small business—the kind of grinding, practical entrepreneurship that turns necessity into a livelihood. Lebanon’s civil war began in 1975 and lasted fifteen years, with an estimated 120,000 lives lost. For Machaalani, that history wasn’t a distant fact; it was part of the backdrop that shaped how he saw work, risk, and resilience.

Mitchell Harper’s path looked different, but it rhymed. He was self-taught, building software from a young age. By twelve, he was writing programs in QBasic on an old XT computer—curious, relentless, and comfortable teaching himself whatever he needed next.

Harper jumped into an IRC chatroom looking for help, and ran into Machaalani—another developer working on similar problems, including an HTML editing component and a website CMS. They connected, then met up in real life, and the collaboration snapped into place. In 2003, they combined what they were building and launched a new company: Interspire.

Interspire was a bootstrapper’s kind of business. No venture capital. Just products customers were willing to pay for, shipped fast and improved constantly. Harper led the technical development. Machaalani obsessed over design and customer experience. Together, they built a bundle of practical tools—knowledge base software, email marketing, shopping cart solutions—licensed software sold to businesses around the world. At their peak, they were running six or seven products at once.

It worked. Interspire grew into a real company with thousands of customers and millions in revenue. And as often happens, the next act didn’t come from a brainstorm—it came from support emails and customer calls.

Merchants kept asking for the same thing: not another piece of software to install and manage, but a hosted e-commerce solution—something that removed the technical overhead of running an online store. At first, Harper and Machaalani resisted. In their minds, they already had plenty on their plate. As they put it later: “Initially, we resisted. We figured we had enough products. … I mean, by that time we had seven or eight products.”

Eventually, the requests got too consistent to ignore. Harper went off to build it, and came back with an almost-completed e-commerce platform.

Around this time, they made a hire that mattered: Chris Boulton, a Target employee by day and a software programmer by night. Boulton became a key force in the technical evolution of what they were building. Harper later credited him heavily: “I’ve always said that I knew enough to be dangerous… but I wasn’t nearly as talented as any of the engineers we brought in, especially Chris.”

They launched the product in late 2007 as licensed software, and demand showed up immediately. They pre-sold more than $250,000 in licenses and generated roughly $2–3 million in 2008. But success exposed a structural problem: e-commerce isn’t like other business software. Merchants don’t just need features—they need uptime, security, and the ability to handle traffic spikes without breaking. Those hosting requirements were becoming the product, and the licensed model wasn’t built for it.

So in 2009, Harper and Machaalani made the decision that would set the trajectory for everything that came after: they would re-architect the platform as a hosted SaaS solution. In 2010, working out of the prior business and funding early efforts with about $10,000 on their credit cards, they launched it under a new name.

BigCommerce.

III. Early Growth & The Bootstrap-to-VC Transition (2009-2012)

BigCommerce didn’t wait for permission to become an American company. The same year it relaunched as SaaS, it opened its first U.S. office—half a world away from Sydney—in Austin, Texas.

Austin wasn’t a random bet. Most of BigCommerce’s customers were already in North America. The venture capital scene in Australia was still early. And Austin offered what the Bay Area didn’t: a fast-growing tech community, a lower cost base, and an environment that made it easier to hire and scale.

The early product strategy was just as pragmatic. BigCommerce went after a very specific customer: the merchant who had outgrown the simplest tools but didn’t want to take on the cost and complexity of heavyweight enterprise platforms. In other words, it aimed for the middle—serious businesses that needed real functionality without signing up for an IT project.

And then came the hard part: the business model reset. Moving from licensed software to subscriptions meant giving up the comfort of upfront checks for the slower build of recurring revenue. It’s the classic trade—pain now, compounding later. But the founders believed hosting, uptime, security, and ease of use weren’t add-ons in e-commerce. They were the product. SaaS wasn’t just a pricing change; it was the only way to deliver what merchants were actually asking for.

It worked. By June 2012, BigCommerce had grown to roughly 20,000 active merchants—an enormous number for a company that was still, in spirit, a bootstrapper.

But scale attracts gravity. If BigCommerce wanted to compete in a market where Shopify was already pulling away, it needed resources—more engineering, more go-to-market muscle, and a faster pace of product expansion. That meant doing the thing many bootstrapped founders resist for as long as possible: raising outside capital.

In July 2011, BigCommerce raised a $15 million Series A led by General Catalyst—its first major institutional round. Harper later described the psychological hurdle as much as the financial one: taking other people’s money felt like stepping onto a path where “massive success” and “massive failure” were both suddenly on the table, and the difference could come down to growing too quickly and letting that speed break the company.

Once they crossed that line, the mindset shifted. BigCommerce stopped thinking like a profitable software shop and started thinking like a platform company. Harper and Machaalani flew back to Sydney with fresh capital and a new mission: scale fast without losing the culture they’d built—made trickier by the reality that both founders wanted to remain Sydney-based even as the Austin team grew into the operational center of gravity.

By 2014, BigCommerce had passed 50,000 paying customers, grown to around 300 employees, and raised a total of $75 million. The company had a real footprint, real momentum, and—most importantly—a real runway for the next chapter.

IV. Building the Moat: Platform Strategy & Ecosystem (2013-2015)

If the early years were about proving BigCommerce could work, 2013 to 2015 was about making sure it could last. In e-commerce platforms, features matter—but ecosystems decide who wins. The merchants with real complexity don’t just buy a storefront. They buy everything that connects to it: payments, shipping, taxes, marketing, inventory, analytics, and the thousand edge cases that show up once you’re doing meaningful volume.

So in 2013, BigCommerce launched its App Marketplace. On the surface, it was a catalog of integrations. Strategically, it was BigCommerce admitting what Shopify already understood: this business isn’t one product, it’s a platform. A two-sided market where developers build, merchants install, and the ecosystem compounds.

But BigCommerce wasn’t trying to copy Shopify. It was trying to beat Shopify at a different game.

This is where the company’s “Open SaaS” identity started to harden into a real strategy. BigCommerce took a hybrid approach: the convenience of SaaS—security, scalability, automatic updates—paired with the flexibility merchants associated with open-source. Through robust APIs and headless commerce capabilities, businesses could build tailored experiences, bring their own frontend, and integrate deeply with the rest of their stack, without taking on the burden of hosting, patching, or maintaining infrastructure.

The positioning was deliberate: be the “Magento of SaaS.” Give enterprise merchants the ability to customize nearly everything—checkout flows, catalog management, integrations—while keeping the operational headaches off their plate.

And with that, the competitive wedge against Shopify became clear. Shopify optimized for simplicity: get a first-time merchant online fast. BigCommerce optimized for flexibility: make it possible for a serious merchant to plug into ERPs, build custom experiences, and keep evolving without hitting a wall. The bet was that as merchants grew up, they’d stop treating “easy” as the main requirement—and start treating “adaptable” as the difference between scaling and stalling.

In April 2015, BigCommerce made its first acquisition, buying Zing to add checkout and inventory technology. It was an early signal that BigCommerce saw where commerce was heading: omnichannel. The line between online and offline was blurring, and merchants were going to need unified inventory and checkout across wherever customers chose to buy.

At the same time, BigCommerce pushed hard on marketplace integrations. Instead of forcing merchants to run Amazon, eBay, and their own storefront as separate worlds, BigCommerce worked to sync inventory, orders, and product data from a single dashboard—one more step toward becoming the system of record for commerce, not just the website that takes the order.

V. Leadership Transition & Enterprise Pivot (2015-2017)

By 2015, BigCommerce hit the moment every fast-growing company eventually runs into: the thing that got you here won’t necessarily get you there. The team was now roughly 300 people. The business had real scale. And Eddie Machaalani was staring down a hard, founder-level truth—he loved being close to customers and the product, not managing a few hundred people.

So he made a call rooted in self-awareness. At that size, he said, he’d stopped having fun. The work had drifted away from the hands-on, customer-intimate building that energized him most.

In June 2015, BigCommerce brought in Brent Bellm as CEO, and the company’s headquarters moved officially to Austin, Texas. Bellm wasn’t a typical “professional CEO” hire. He’d been COO at HomeAway and helped lead it through its IPO, during a period when the business scaled rapidly and profitably. Before that, he’d held senior roles at PayPal and eBay—experience forged inside online marketplaces and payments, where platform dynamics and distribution are life-or-death.

Bellm walked into a company that was doing a lot right—and still had a glaring problem. BigCommerce had become a major SaaS platform for small businesses. But in the most important race in the category, it was running from behind. Shopify was already the clear leader, with years of momentum and a head start that was compounding into ecosystem strength. Bellm’s conclusion was blunt: BigCommerce couldn’t keep doing the same thing, selling to the same customers the same way, and expect to catch the number one player.

So the strategy pivoted upmarket.

Instead of trying to win the SMB land-grab, BigCommerce went after mid-market and enterprise merchants—the ones who cared less about “easy setup” and more about flexibility. The merchants who needed open APIs, headless capabilities, deep integrations, and the freedom to build the exact experience they wanted without being boxed in by a more closed platform.

That shift wasn’t a tweak. It required rewiring almost everything: product priorities, messaging, partnerships, who the sales team targeted, how customer success operated, even what “great” looked like internally. Bellm was effectively turning BigCommerce from a tool for independent storeowners into a platform pitched to serious brands with serious complexity—while still promising they wouldn’t have to endure the traditional enterprise mess.

This was also when “Open SaaS” stopped being a philosophy and became the company’s core identity. BigCommerce wasn’t going to out-Shopify Shopify on simplicity. It was going to be the alternative for sophisticated merchants who wanted enterprise-grade power without enterprise-grade friction.

And it backed that positioning with concrete moves. In 2016, BigCommerce partnered with Amazon to help retailers sync inventory across both channels—one more step toward being a flexible system that could plug into wherever customers were actually buying.

The costs of the pivot were real. To compete for larger merchants, BigCommerce needed to invest in enterprise-grade capabilities—things like multi-storefront, B2B functionality, and deeper headless support—and it needed to learn how to sell to a completely different buyer than the one it had built the company on.

VI. The IPO Journey & Public Market Reality Check (2018-2021)

The road to an IPO wasn’t a single breakthrough moment. It was years of unglamorous execution under Brent Bellm: keep upgrading the product for bigger merchants, keep building credibility in enterprise, and keep proving that “Open SaaS” was more than a slogan.

By 2020, BigCommerce had become a real global platform, serving tens of thousands of merchants across more than 120 countries. In July 2020, the company filed to go public. On August 5, 2020, BigCommerce hit the NASDAQ.

The timing couldn’t have been more dramatic. COVID-19 didn’t just nudge retail online; it yanked it forward. As consumers shifted spending to the internet, investors stampeded into anything that looked like e-commerce infrastructure. BigCommerce raised its expected IPO price range to $21–$23, up from $18–$20, before pricing at $24.

It opened at $24 in a 10.4 million share offering, with 7.9 million shares sold by the company and the rest by existing shareholders. And then the first day turned into a spectacle. Shares surged into triple-digit gains, trading was halted twice as the price spiked within minutes, and the company’s market capitalization shot north of $5 billion. BigCommerce raised nearly $216 million in the offering.

For a brief, intoxicating stretch, BigCommerce was valued at more than $6 billion—an astonishing outcome for a business that, a decade earlier, had been funded with about $10,000 on credit cards.

But public markets don’t grade on a curve. They compare you to the leader. And in e-commerce platforms, the leader was still Shopify.

The pandemic boom also made it easy to miss what was happening underneath: BigCommerce was growing, but Shopify was growing faster. BigCommerce was moving upmarket, but Shopify was pushing Shopify Plus hard into the same enterprise segment.

One metric did validate Bellm’s strategy. Enterprise ARR climbed from $90 million in Q3 2020, around the IPO, to $269 million by Q2 2025. Enterprise also grew from less than half of total ARR at IPO to about three-quarters.

That was the bright spot: bigger customers, bigger contracts, and relationships that tended to stick.

The problem was that enterprise traction didn’t automatically translate into a narrative Wall Street loves. Overall growth slowed, expectations reset, and the stock slid for years from its early highs.

And the Shopify shadow only got longer. Shopify continued to sprint ahead, with more than a million businesses across 175 countries. As Gaurav Joshi of AArete put it: “Shopify is far and away the leader, with 3x the apps connections and 1 million-plus customers,” while BigCommerce had “been in catch-up mode” for some time. Still, Joshi pointed to one potential lever that could change the equation: Feedonomics, which he said “unlocks several doors.”

VII. The Feedonomics Acquisition: Omnichannel Ambitions (2021)

If “Open SaaS” was BigCommerce’s wedge against Shopify, Feedonomics was a bet on the part of commerce most people ignore until it breaks: the product data.

In July 2021, BigCommerce acquired the assets of Feedonomics for about $145 million—roughly $80 million paid at closing, with additional payments of up to $32.5 million due on the first and second anniversaries of the deal.

Feedonomics wasn’t a storefront tool. It was the machinery behind omnichannel selling: a full-service data feed management platform that helps mid-market and enterprise merchants show up correctly across hundreds of marketplaces and advertising channels. It ingests product data, cleans it up, enriches it, and then syndicates it out to the places shoppers actually discover products—search engines, ad networks, social platforms, and marketplaces. And once the orders come in, it syncs the resulting order data back into the merchant’s existing systems to keep operations from turning into chaos.

Brent Bellm framed the logic clearly. “This acquisition reflects our strong belief that Feedonomics offers the world's best product feed optimization and syndication solution for merchants looking to optimize their advertising and selling via search engines, ad networks, social media sites and marketplaces. On average, these channels represent ecommerce merchants' largest non-direct source of sales and one of the largest spending line items,” he said.

BigCommerce’s promise was that, together, the two companies could “connect the dots” between a merchant’s back-end operations and the channels that actually drive demand—improving return on ad spend, conversion, and ultimately GMV.

This also fit BigCommerce’s broader philosophy. The company kept leaning into a best-of-breed world of partner integrations, while Shopify increasingly pushed toward proprietary tools. Bellm’s view was that Feedonomics had already proven itself where it mattered most: at scale. “We knew having worked with [Feedonomics] that in terms of feed management, optimization and integration, at scale they are the best,” he said.

What made the deal look even smarter in hindsight was the data layer it added. Feedonomics didn’t just distribute product catalogs—it standardized and optimized them for each channel’s rules and quirks. As commerce started drifting toward AI-driven search and discovery, that capability began to look less like a nice-to-have and more like infrastructure.

And of course, there was the straightforward commercial upside: Feedonomics could sell into BigCommerce’s merchant base, and BigCommerce could walk into enterprise deals with a broader, stickier platform story.

VIII. Makeswift, Multi-Storefront & The Composable Era (2021-2024)

If Feedonomics was about getting the data layer right, the next chapter was about the layer customers actually see: the storefront experience. BigCommerce wanted enterprise merchants to move fast, ship beautiful experiences, and still keep the flexibility that “Open SaaS” promised—without turning every change into a weeks-long developer project.

A big step in that direction was Multi-Storefront. It first launched in March 2022, reached general release for enterprise merchants in April, and by February 2023 it expanded to all plans. The idea was straightforward but powerful: one BigCommerce account could run multiple storefronts or brands. For enterprises managing portfolios, regional sites, or distinct customer segments, this was table stakes—and BigCommerce needed to have it.

Then came a bet on how the modern web was being built.

On October 31, 2023, BigCommerce acquired Makeswift, Inc. for $9 million. Makeswift billed itself as the world’s most powerful visual editor for Next.js websites: a no-code visual builder that makes React components visually editable. In plain English, it let teams build and iterate on high-performance storefronts without bottlenecking everything on engineering.

The acquisition wasn’t out of the blue. Makeswift had been working closely with BigCommerce throughout 2023 as both a customer and a partner, and along the way they found they were pushing toward the same destination: a “composable” future, where merchants build exactly what they want by snapping together the best tools for each job.

That’s also the context for BigCommerce’s Catalyst: an open-source, composable, fully customizable headless commerce framework designed to speed up storefront creation. Catalyst is built with Next.js and React, powered by BigCommerce’s GraphQL Storefront API, and it includes a drag-and-drop visual editor out of the box—aimed at giving developers a strong foundation while still letting marketers and designers move quickly.

All of this was riding a broader shift in enterprise e-commerce. The old model was a monolith: one platform that tried to do everything, end to end. The new model was composable commerce—assemble best-of-breed components: a headless CMS here, specialized search there, maybe a custom checkout flow on top.

Composable commerce often gets described as MACH architecture: Microservices, API-first, Cloud-native, Headless. The takeaway is the same: more flexibility, less lock-in, and faster iteration.

BigCommerce leaned into that world by positioning itself as the commerce engine inside the stack—the transactional core that could plug into whatever experience layer the merchant wanted to build.

IX. The Rebrand to Commerce.com & Agentic Commerce Vision (2024-2025)

In October 2024, BigCommerce made it clear the transformation wasn’t slowing down—it was speeding up. On October 2, the company announced it had parted ways with Brent Bellm, who had been serving as both CEO and chairman. He exited both roles immediately.

In his place: Travis Hess, the company’s president, who had only joined a few months earlier, in May 2024.

Hess wasn’t new to commerce, but he was new to BigCommerce. He’d spent more than 15 years in senior leadership roles across commerce agencies and consultancies, served on partner advisory boards for companies like Shopify, Klaviyo, SAP/Hybris, and Rackspace, and was recognized as one of the 30 Most Influential in Ecommerce. Most recently, he was a managing director at Accenture, where he led its direct-to-consumer commerce offering and go-to-market strategy—and managed Accenture’s Shopify partnership globally.

Then came the brand reset.

BigCommerce Holdings, Inc. announced the launch of a new parent brand, Commerce, and officially changed its corporate name to Commerce.com, Inc. The idea was to pull what had effectively become a multi-product company—BigCommerce, Feedonomics, and Makeswift—into one unified platform story aimed at powering what it calls the next era of agentic commerce. Alongside the rebrand, effective on or about August 1, 2025, the company’s common stock began trading on the Nasdaq Global Market under a new ticker symbol: CMRC.

“We’ve rebooted the entire company,” Hess said in an interview. “It’s not just a new name — it’s a new model. The market is changing, and we needed a brand that reflects where commerce is going, not where it’s been.”

He pointed to a simple but telling moment from his own onboarding. “I didn’t even know BigCommerce owned Feedonomics when I interviewed,” Hess said. “That told me everything I needed to know about how disconnected the story was. We had to unify the business.”

The repositioning hinged on a specific thesis: that shopping is starting to move upstream, away from traditional storefront browsing and toward AI-driven discovery and decision-making. In Hess’s framing, “agentic commerce” is the model where AI handles much of product research and purchasing on a consumer’s behalf—and that requires a different kind of infrastructure. “Agentic commerce requires a new playbook,” he said. “Commerce is here to deliver it with an open ecosystem built for speed, intelligence and flexibility.”

The company tied that shift to how consumers were already behaving, using generative AI platforms like ChatGPT, Perplexity, and Google’s Gemini to search for products and make decisions—sometimes without ever visiting a traditional ecommerce site.

Even the domain told you this wasn’t meant to be subtle. Commerce.com reportedly cost roughly $2.4 million—cheap for a category-defining domain, but also a reminder that only a handful of global players could realistically justify buying it. The message was clear: this wasn’t a feature launch. It was a claim on the category—platform ambitions, not point-solution positioning.

X. Current State & The Profitability Pivot (2024-2025)

The latest earnings make the new posture obvious: this is no longer a “grow at any cost” story. It’s a company choosing discipline—because the market demanded it, and because the business needed to prove it could generate real profit, not just revenue.

In Q2 2025, Commerce.com reported $84.4 million in revenue, up 3% from the prior year. Total ARR rose to $354.6 million, also up 3%. The heart of the business is now firmly enterprise: enterprise ARR reached $269.3 million, growing 6% year over year.

That mix shift keeps tightening. As of June 30, 2025, enterprise accounts represented 76% of total ARR, up from 73% a year earlier. Margins also improved: GAAP gross margin was 79% versus 76% in Q2 2024, and non-GAAP gross margin was 80% versus 77%.

And, crucially, profitability showed up in a way that’s hard to hand-wave away. Commerce.com delivered $4.8 million in non-GAAP operating income and $5.7 million in adjusted EBITDA. After years of losses, it was a clear signal that the model can work at scale—especially when the company prioritizes efficiency.

There’s still a growth reality check embedded in the numbers. Since the IPO, total ARR has compounded at about 17% annually, but more recent quarterly growth has been modest. The cash story, however, has moved sharply in the right direction: operating cash flow improved to $14 million in Q2 2025 (a 16% margin), compared to negative $14 million (a -20% margin) in Q2 2022.

The customer metrics tell you what kind of business this is becoming. Enterprise accounts totaled 5,803, down 3% year over year. But the accounts that stayed, or landed, got bigger: enterprise ARPA rose 9% to $46,403.

That’s the “land and expand” dynamic in action—fewer logos, larger relationships. The open question is what’s driving it: healthy focus on higher-quality customers, or mounting pressure at the top of the funnel as competition intensifies.

Commerce.com ended the quarter with $135.6 million in cash, cash equivalents, restricted cash, and marketable securities, and generated positive free cash flow of $11.9 million for the quarter.

XI. Competitive Landscape & Strategic Positioning

Commerce.com plays in one of the harshest arenas in software: e-commerce platforms, where the leader doesn’t just win on product. It wins on ecosystem, distribution, and sheer momentum.

At the center of the category sits Shopify—the company that made “start an online store” feel as easy as spinning up a social profile, then used that SMB scale to build an enormous advantage. Shopify now claims a dominant share of the top direct-to-consumer brands, supports millions of businesses across 175+ countries, and has built a sprawling partner and app ecosystem—thousands of experts and tens of thousands of apps and integrations. For anyone competing with Shopify, that’s the real challenge: you’re not just selling a platform. You’re selling against an entire gravity well.

By comparison, BigCommerce remains much smaller in market share and store count. But it’s also very much in the conversation: a well-regarded SaaS platform known for flexibility and feature depth, serving a large global merchant base across B2B and B2C in roughly 150 countries. Even with a modest share of the U.S. e-commerce software market, it’s consistently counted among the top platforms in the space, including meaningful adoption in Europe. And industry surveys have suggested a notable minority of e-commerce professionals chose BigCommerce in 2023—evidence that, for the right customer, the product is a credible alternative.

Then, at the pure enterprise end, you’ve got the heavyweights: Adobe Commerce (Magento), Salesforce Commerce Cloud, and Oracle Commerce. These are built for the biggest retailers in the world—along with the biggest budgets, the longest implementation timelines, and the most complex deployments.

Commerce.com’s sweet spot is the gap between those extremes: mid-market and lower-enterprise businesses that have outgrown the “easy button,” but don’t want—or can’t justify—massive, seven-figure platform implementations.

That strategy shows up in who actually uses the platform. In 2024, more than 60 of the Top 2000 online retailers ran on BigCommerce, and together those retailers generated over $4.1 billion in annual e-commerce sales.

The wedge is still the same one the company has been sharpening for years: Open SaaS. BigCommerce’s pitch is that you can get SaaS reliability—performance, security, uptime—without giving up flexibility. That means an architecture designed for integrations and customization, plus enterprise-grade capabilities like multi-storefront and multi-region support. And for teams building in a composable world, the Catalyst storefront starter kit is meant to reduce the time it takes to launch modern, headless experiences—so brands can move fast without turning every change into an engineering fire drill.

XII. Playbook: Business & Strategic Lessons

The Commerce.com story is a reminder of what it actually takes to build in a market where the leader is always one step ahead, and the rest of the field is fighting over what’s left.

Counter-positioning is survival. When you can’t outspend or out-scale the market leader, you don’t win by chasing them—you win by choosing the hill they can’t easily take. For Commerce.com, that hill was Open SaaS: SaaS reliability with real flexibility. Shopify’s advantage is simplicity and a tightly controlled ecosystem. Commerce.com bet that a meaningful segment of merchants would eventually value openness and composability more than the easy button. Both are valid. The key is committing to one and building the whole company around it.

Timing matters, but it’s not everything. BigCommerce was arguably too late to “own” SMB the way Shopify did, and too early to fully benefit from the composable commerce wave before the market matured. COVID should have been a rocket booster for everyone in the category, but Shopify captured most of that momentum. What’s notable isn’t that BigCommerce missed a moment—it’s that it stayed alive, kept shipping, and kept adapting until the market caught up to some of its bets.

When to pivot upmarket. The enterprise shift wasn’t just a new go-to-market motion—it was a strategic escape route. Instead of spending forever in a land-grab it was unlikely to win, BigCommerce went after merchants who cared about APIs, integrations, and control. The results show up in the mix: enterprise has grown from 46% of ARR at IPO to 76% now. The lesson isn’t “enterprise is better.” It’s “pick the segment where your differentiation actually matters.”

M&A as capability building. Feedonomics and Makeswift weren’t about rolling up competitors. They were about time. In markets that move this fast, “we’ll build it ourselves” can be another way of saying “we’ll arrive late.” These acquisitions added new layers—product data syndication, modern storefront creation—that would have taken years to replicate, and they gave Commerce.com a broader platform story in enterprise deals.

The rebrand as strategic reset. Brands carry baggage. For years, “BigCommerce” inevitably read as “the Shopify alternative.” The Commerce.com rebrand is an attempt to stop playing on someone else’s scoreboard and claim a bigger category narrative: a unified platform across BigCommerce, Feedonomics, and Makeswift, built for where commerce is headed next. It’s risky, but it’s coherent. Sometimes the only way out of a shadow is to move the whole spotlight.

XIII. Porter's 5 Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: MEDIUM

E-commerce platforms have real barriers to entry. The software is complex, customers expect near-perfect reliability, and the moment you move upmarket you’re dealing with long sales cycles and the kind of integrations that create real switching costs. The moat also isn’t just code—it’s the ecosystem of apps, agencies, and developers that makes a platform feel “safe” to bet a business on.

But the floor is dropping in another way. Cloud infrastructure is now a commodity, and AI-assisted development is making it faster and cheaper for new teams to ship credible products. That’s why new entrants keep showing up at the edges: headless-first players, vertical-specific solutions, and focused tools that do one thing extremely well.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW

Commerce.com doesn’t rely on a single choke-point supplier. Cloud providers like AWS and GCP are broadly interchangeable, and the ecosystem of app and technology partners is competitive—partners want access to merchants, not the other way around. That keeps supplier leverage relatively low, and it gives Commerce.com room to change providers or renegotiate terms without risking the core business.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MEDIUM-HIGH

For serious merchants, switching is painful. You’re moving catalogs, rebuilding customizations, reworking integrations, retraining teams, and accepting the risk of downtime or conversion loss during migration. That friction is real.

But buyers still have leverage—especially at the enterprise level—because there are plenty of viable alternatives. Shopify, Adobe, Salesforce, and others all want the same accounts, and that competition gives customers negotiating power on pricing, contracts, and roadmap commitments. On the SMB side, buyer power shows up differently: more price sensitivity, more churn risk, and less patience for complexity.

Threat of Substitutes: HIGH

This is the most uncomfortable force for any commerce platform. Merchants can increasingly bypass “a platform” altogether by going headless and assembling their own stack—often following MACH principles: microservices, API-first, cloud-native, headless. Others choose vertical SaaS tools built for specific categories. And plenty of sellers skip the branded storefront route entirely, leaning into marketplaces and marketplace-like products where the platform owns the customer relationship.

In other words: the substitute isn’t one competitor. It’s the idea that you don’t need a traditional e-commerce platform in the first place.

Competitive Rivalry: VERY HIGH

Commerce is one of the most brutal software categories because everyone is fighting on multiple fronts at once: product, pricing, partners, talent, and mindshare. Shopify dominates the mainstream narrative and keeps pushing upmarket. At the enterprise end, Adobe, Salesforce, and Oracle are entrenched. Open-source and newer frameworks keep improving, giving technical teams more options.

The result is a constant feature race, constant pricing pressure, and very little room for mistakes—because customers have choices, and the cost of falling behind is getting written into every competitive deal.

XIV. Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

1. Scale Economies: MODERATE

Commerce.com benefits from the usual SaaS scale curves: infrastructure gets cheaper per customer, and R&D can be amortized across a larger base. But this is also where the Shopify gap hurts most. Shopify’s scale advantage translates into better unit economics and more room to invest, and Commerce.com’s enterprise mix—higher ARPA, more complex deployments—helps, but it doesn’t close that distance.

2. Network Effects: WEAK-TO-MODERATE

The App Marketplace creates a classic two-sided flywheel: more merchants attract more developers, which produces more apps, which attracts more merchants. The challenge is intensity. Shopify’s ecosystem is simply bigger and louder, and that matters when developers and agencies choose where to place their bets. Also, enterprise buyers don’t select platforms primarily because of “how many apps exist”—they buy for flexibility, integrations, and fit—so the network effect matters, just less than it does in SMB.

3. Counter-Positioning: STRONG

This is the heart of the strategy, and arguably the company’s clearest power. “Open SaaS” is not a minor feature difference—it’s a philosophical stance against Shopify’s more integrated approach. Commerce.com is optimizing for merchants who want composability, open APIs, and control. Shopify can add flexibility at the edges, but leaning too far into openness risks diluting the simplicity that made it dominant. That’s what makes this counter-positioning real: it’s hard for the leader to copy without trade-offs.

4. Switching Costs: STRONG

Once Commerce.com is deeply embedded, it’s sticky. Replatforming means migrating catalogs, rebuilding customizations, redoing integrations, retraining teams, and accepting meaningful operational risk. In enterprise, that work takes months, not days. Feedonomics increases the friction even further—because now it’s not just the storefront and checkout. It’s the product data and syndication infrastructure running across channels.

5. Branding: MODERATE

Within mid-market and enterprise circles, BigCommerce built a solid reputation for flexibility and “Open SaaS.” But it’s still operating in the shadow of a consumer-grade brand: Shopify is the household name. The Commerce.com rebrand is an attempt to elevate the umbrella story and claim category-level relevance—but branding power is earned over time, not bought in a press release.

6. Cornered Resource: WEAK

There’s no single cornered resource that competitors can’t access. No exclusive partnerships, no irreplicable IP. Feedonomics is a meaningful asset, but it’s not something only Commerce.com can have in a durable, defensible way. The Commerce.com domain is valuable—and strategically smart—but it’s not a moat by itself.

7. Process Power: MODERATE

Where Commerce.com does have an advantage is in accumulated know-how: running enterprise implementations, supporting complex merchants, and learning what actually breaks at scale. The combined workflow across BigCommerce, Feedonomics, and Makeswift can also create an internal efficiency that’s hard to see from the outside. Over time, that kind of operational muscle becomes a real edge—especially in enterprise, where execution often beats features.

Overall Power Position: MODERATE

Commerce.com’s strongest powers are Counter-Positioning, Switching Costs, and Process Power. Its biggest weaknesses remain Scale, Network Effects, and Branding relative to Shopify. The strategic mandate is clear: defend the enterprise niche it can credibly own, and use AI-driven differentiation—especially around data and discovery—to widen the gap where Shopify is least likely to follow.

XV. Bear vs. Bull Case

🐻 Bear Case:

Shopify’s lead keeps compounding, and it’s no longer just an SMB story. Shopify Plus continues to move upmarket, squeezing the exact segment Commerce.com has spent years repositioning toward. At the same time, Commerce.com’s growth has cooled—management’s 2–4% revenue growth outlook for 2025 is modest—and the customer count has been slipping year over year. With a market cap around $350 million and negative GAAP earnings, the market is effectively saying: prove this can be a durable, value-creating business, not just a competent platform in a brutal category.

Then there’s the question hanging over the whole rebrand: does “agentic commerce” meaningfully change the competitive landscape, or does it simply raise the baseline for everyone? If AI-driven discovery and purchasing becomes table stakes across platforms, Commerce.com doesn’t automatically win just because it’s talking about it first.

Put those together—slower growth, ongoing competitive pressure, and a big strategic pivot under a new CEO—and the bear case starts to look like this: Commerce.com becomes more valuable as part of someone else’s stack than as a standalone public company. Add in financial risk from a high debt-to-equity ratio, and the margin for error narrows fast if the macro environment worsens or execution slips. Rebrands and turnarounds are easy to announce and hard to complete.

🐂 Bull Case:

The bull case starts with the most important thing the company has done in years: it has begun to look like a real, profit-generating SaaS business. In Q2 2025, Commerce.com posted about $5 million in positive non-GAAP operating income. That’s not a victory lap, but it is proof the model can work when the company prioritizes efficiency.

The second pillar is differentiation that’s actually legible in enterprise: BigCommerce for the commerce engine, Feedonomics for the product data and syndication layer, and Makeswift for building modern storefront experiences faster. Together, that combination is unusually aligned with how serious merchants are building today—omnichannel distribution, composable stacks, and teams that want flexibility without turning every change into an engineering project.

And then there’s the upside embedded in the “agentic commerce” thesis. If shopping increasingly starts in AI-driven search and recommendation systems, the bottleneck shifts from “who has the best theme” to “who has the best data and infrastructure to surface the right products, in the right format, across the right channels.” Feedonomics, in particular, could become more than an add-on—it could become central. Management expects acceleration from 2026 onward as new products and go-to-market investments take hold.

From a market perspective, bulls can plausibly argue the stock is underappreciated relative to SaaS peers, and that meaningful institutional ownership—around 52%—signals there are sophisticated investors willing to underwrite the turnaround. The Commerce.com domain and umbrella brand also give the company a larger narrative to sell: not “the Shopify alternative,” but a platform built for what comes after the traditional storefront. And if composable becomes the enterprise default, Open SaaS stops sounding like positioning and starts sounding like inevitability.

XVI. The Agentic Commerce Thesis & What's Next

Commerce.com’s bet on “agentic commerce” is both its biggest opening and its biggest gamble. The company is arguing that the next battle in e-commerce won’t be won on templates, themes, or even checkout. It’ll be won upstream—where products get discovered and decisions get made—inside AI systems that increasingly act as the first interface between shoppers and merchants.

That’s the context for a key move: BigCommerce and Feedonomics deepened their partnership with Google Cloud, aiming to help merchants improve performance using Google Cloud’s next-generation AI tools. The promise is straightforward: better product discoverability and higher conversions across the Google ecosystem, powered by cleaner, richer product data.

Here’s what that looks like in practice.

Feedonomics Surface, now in closed beta for BigCommerce customers, is designed to optimize and deliver high-quality product data directly into Google Merchant Center. The idea is that if your product data is AI-enriched and properly structured, you show up more accurately—and more often—across the channels where Google is sending shopping traffic.

Feedonomics is also rolling out new AI-powered data enrichment capabilities built on Google Cloud with Gemini. Instead of merchants manually cleaning and enhancing catalogs, the system can automatically enrich product attributes and descriptions, creating more compelling product data that can then be syndicated across any Feedonomics-supported channel—improving search performance and conversion rates along the way.

And on the builder side, Commerce.com is trying to make “agentic” real for developers, not just a marketing phrase. By combining BigCommerce’s Model Context Protocol (MCP), currently in closed beta, with Google’s Agent Development Kit (ADK), developers can build intelligent, commerce-aware merchant agents—software that can automate tasks, personalize experiences, and streamline operations.

Google isn’t the only partner in this story. Commerce.com has also announced expanded partnerships with AI leaders including Perplexity, Microsoft, and PayPal—part of a broader push to make the platform relevant wherever AI-driven discovery and transaction flows end up living.

The thesis underneath all of this is simple, and it has real teeth: as AI increasingly mediates discovery and purchasing, the companies that help merchants become “AI-readable” and “AI-preferred” capture disproportionate value. In that framing, Feedonomics isn’t just an add-on product—it’s the data infrastructure layer that helps merchants compete in a world where the storefront is no longer the starting line.

The hard question is whether that’s enough. Shopify is investing enormous sums into R&D, and every major commerce platform is sprinting toward AI-native features. Commerce.com’s advantage is its positioning as open and composable—but in AI, scale often wins. The next chapter comes down to execution: can Commerce.com turn “agentic commerce” from a compelling narrative into a measurable advantage before the market decides it’s just table stakes?

XVII. Key Metrics to Watch

If you want a simple dashboard for whether Commerce.com’s reinvention is actually working, it comes down to three signals:

1. Enterprise ARR Growth Rate

This is the cleanest read on whether the upmarket strategy is paying off. In Q2 2025, enterprise ARR grew 6% to $269 million—positive, but not exactly runaway. If that rate starts pushing back into double digits, it suggests real momentum. If it slips under 5%, it raises the uncomfortable possibility that the enterprise engine is maturing before the company’s broader platform story fully lands. With enterprise now representing 76% of total ARR, this isn’t just a segment. It is the business.

2. Net Dollar Retention (NDR)

Commerce.com’s customer count has been drifting down, even as revenue per account rises. NDR is what tells you which story is true: disciplined focus on better customers, or churn hidden by a handful of bigger wins.

The company doesn’t always put NDR front and center, so you have to listen for it in the subtext of earnings calls: expansion vs. contraction, logo churn, downgrades, and whether bigger customers are actually deepening their spend over time.

3. Operating Cash Flow

Profitability narratives are easy to pitch and hard to sustain, so cash flow is where the truth shows up. Commerce.com posted $14 million in operating cash flow in Q2 2025, a 16% margin—an enormous swing from negative $14 million and a -20% margin in Q2 2022.

If the company can keep generating cash while still investing in the product, it validates the whole “efficient growth” posture. If cash flow slips back into the red, the market will treat the turnaround as temporary—and the rebrand as noise.

XVIII. Conclusion

Commerce.com’s journey—from an Australian IRC chatroom to a NASDAQ listing to a rebranded, AI-leaning commerce platform—reads like a case study in entrepreneurial persistence. Eddie Machaalani and Mitchell Harper built something real: a platform used by merchants around the world, across roughly 150 countries, and tied to billions of dollars of e-commerce activity. Brent Bellm then took the company through the enterprise pivot and into the public markets. Now Travis Hess is trying to pull the business into its next act, with “agentic commerce” as the banner.

The challenge in front of them is as unforgiving as the category itself. Shopify’s scale compounds every year. Public markets have far less patience for growth-stage losses. And the agentic-commerce thesis is, by definition, a bet on a future that isn’t fully here yet—made by a company that doesn’t have the luxury of many wrong turns.

Still, Commerce.com is playing a game Shopify can’t completely mirror without changing what made it Shopify: an insistence on openness, flexibility, and an ecosystem that lets sophisticated merchants build commerce their way, not the platform’s way. Whether that wedge turns into enduring value is the open question. But sixteen years in, the story isn’t over. The company is still shipping, still repositioning, and still trying to win on different terms.

From here, the plot is simple: execution. Not aspiration. And as Hess has acknowledged, there’s no reason to grandstand—they haven’t earned it yet. The market will be watching.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music