Compass Minerals International: The Salt of the Earth

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture this: it’s a brutal February morning in Chicago. The temperature is well below freezing. Snow has blanketed the interstate, and black ice is waiting in all the places you can’t see. At 3 a.m., highway crews are already out there, trucks rumbling through the dark with rock salt piled high. By the time commuters merge onto the road a few hours later, the lanes are open—safe enough for millions of people to get to work, get kids to school, and keep the city’s economy moving.

Almost nobody thinks about where that salt came from.

Even fewer people realize that one company—whose roots stretch back to 1844—supplies a meaningful share of it.

That company is Compass Minerals International.

Compass is the largest rock salt producer in North America and the U.K. It’s the kind of business that becomes invisible precisely because it works: essential, repetitive, and taken for granted. If it disappeared, winter road safety would get dangerous fast. But because it shows up as a white crust on asphalt instead of an app on your phone, most investors couldn’t pick the company out of a lineup.

And yet the underlying asset base is anything but ordinary. Compass operates the world’s largest underground salt mine. It also owns one of only a handful of facilities globally that can produce sulfate of potash from naturally occurring brine using solar evaporation. This is old-economy geology meeting modern infrastructure—massive fixed costs, unforgiving operations, and a product that’s both crucial and commodity-like.

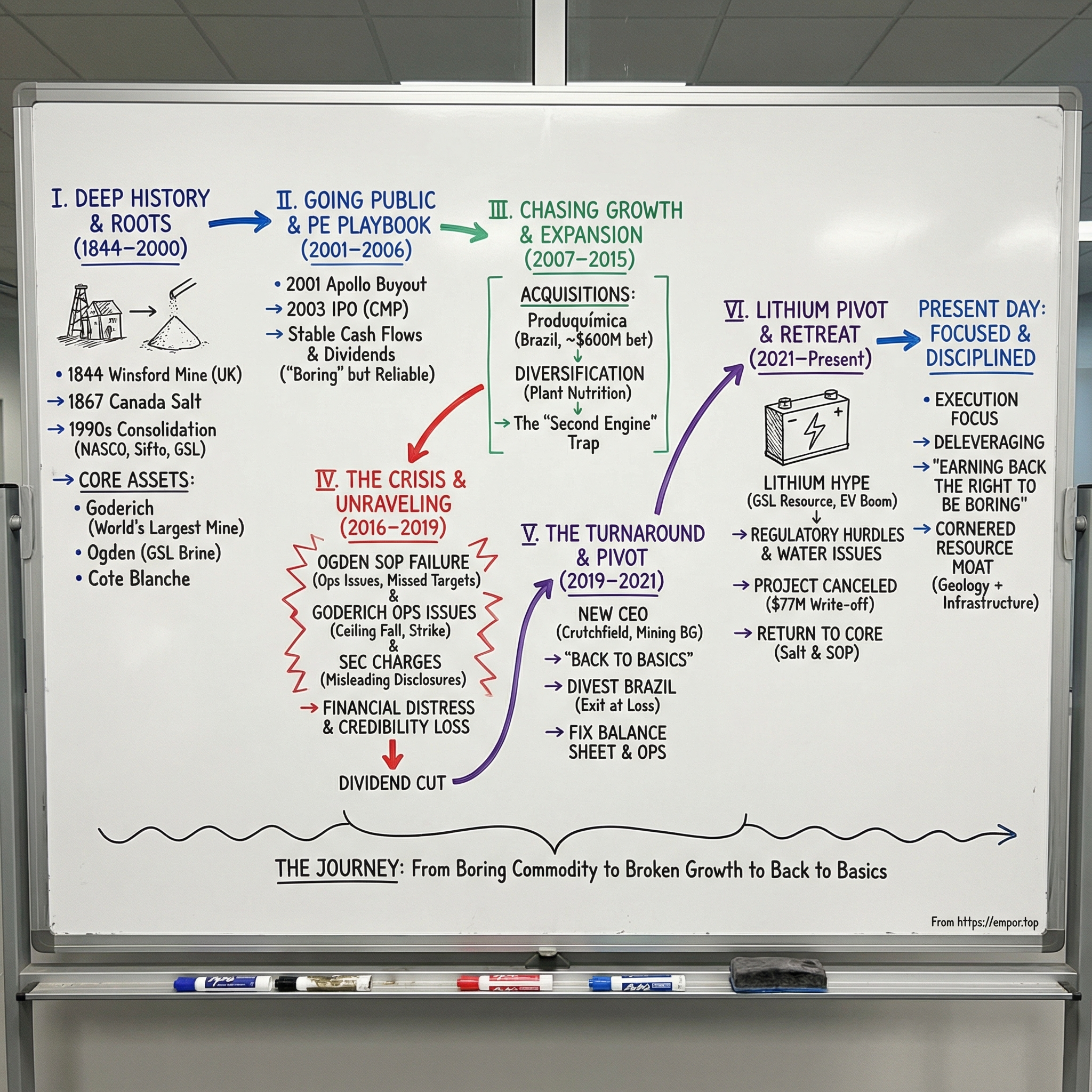

Which sets up the central tension of this story: how does a “boring” salt business become a roughly $1.4 billion public company, nearly break itself chasing diversification, and then claw its way back?

Because Compass didn’t just stumble once. It made big bets. It tried to transform itself. It lived through operational failures that cascaded into financial distress and a credibility crisis. And then, just as it was trying to stabilize, it went looking for the next chapter—pivoting into new ideas like lithium extraction and fire retardants, before walking away from both.

This isn’t only a story about salt. It’s a story about what “operational leverage” really means when your costs are fixed and your product is heavy and cheap. It’s a story about capital allocation—what happens when a company reaches beyond its circle of competence, and what it takes to unwind that decision once the bill comes due. And it’s a story about the rare kind of moat you can’t engineer: cornered geological resources, won by accident of earth history and preserved through permits, rights, and infrastructure.

Along the way, we’ll hit private equity, activists, labor strikes, environmental controversy, and the perennial question that haunts every commodity business: when what you sell is essentially interchangeable, where does value actually come from?

By the end, you’ll never look at a pile of road salt the same way again.

II. The Deep History: Salt, Mines, and American Infrastructure (1844–2000)

Salt is elemental—literally. It’s one of humanity’s oldest commodities, so important that Roman soldiers were sometimes paid in it, which is where we get the word “salary.” Cities grew up around salt deposits. Trade routes were built on it. Before refrigeration, salt was the technology that made food last through winter.

But the salt business we recognize today—industrial-scale production feeding highway departments, chemical plants, and grocery aisles—is mostly a 20th-century invention. The automobile changed everything. As road networks spread across North America and Europe, winter safety became a public works problem. Rock salt became infrastructure.

Compass’s roots start in the U.K., in 1844, with the Winsford rock salt mine in Cheshire. The deposit was discovered during coal prospecting, and the mine began as a local supplier—salt pulled from underground for nearby industrial and consumer use. Over time, it expanded and modernized, but the core idea stayed the same: take an essential mineral out of the earth at scale, year after year.

North America’s story began separately. In 1867, salt operations in Canada were established, growing from early evaporation-style production into more organized regional distribution by the late 1800s.

The company we now know as Compass didn’t appear in one founding moment. It was assembled—slowly—through decades of consolidation: smaller regional operators combining assets, footprints, and customer contracts until a coherent platform emerged. The key phase came in the 1990s. In 1990, DGHA formed North American Salt Company (NASCO) as a holding company and acquired Sifto Salt from Domtar, including the Goderich, Amherst, Milwaukee, and Unity operations.

Then came the crown jewel moves in 1993. DGHA acquired Great Salt Lake Minerals, including the Ogden sulfate of potash and magnesium chloride plants, opened the Ogden salt plant, acquired Salt Union (including the Winsford mine), and founded Harris Chemical Group as another holding company. This brought in the Utah operations—centered around Ogden, where activity on the Great Salt Lake dated back to 1968—that would later become both the source of Compass’s biggest ambitions and its most painful disappointments.

In 1998, the assets changed hands again. IMC Global (later Mosaic) acquired the Harris Chemical Group assets for approximately $1.4 billion—$450 million in cash and $950 million in debt—and reorganized the portfolio under the IMC Salt umbrella. But commodity businesses are unforgiving, and IMC’s center of gravity was fertilizers, not salt. By the early 2000s, these salt assets were ready for a new owner.

So what made them valuable? Not brand. Not patents. Geography and geology.

Start with Goderich, Ontario: a mine roughly 1,800 feet under Lake Huron that’s widely described as the largest underground salt mine in the world. It has been operating since 1959, and it can produce up to about four million metric tons annually. It sits atop an ancient, continuous formation—one of those rare deposits where decades of mining and data reinforce the same conclusion: the salt is still there, and the mine still matters.

Down on the Gulf Coast, Compass also had Cote Blanche in Avery Island, Louisiana—an underground rock salt operation about 1,500 feet deep. Established in 1961 and integrated into the broader portfolio in 1990, it anchored Gulf Coast distribution through depots tied into the Mississippi and other waterways.

And then there’s Utah, which is different in kind, not just in location. Near Ogden on the Great Salt Lake, Compass draws naturally occurring brine into shallow ponds and uses solar evaporation to produce salt, sulfate of potash (SOP), and magnesium chloride. Its SOP plant there is the largest in North America and one of only three SOP brine solar evaporation operations in the world.

Put those together—underground mines in Canada, Louisiana, and the U.K., plus solar evaporation ponds in Utah, plus other evaporation facilities across North America—and you get the foundation of what became Compass Minerals. The geographic spread wasn’t a nice-to-have. It was the business model. Salt is heavy and cheap per ton, which means transportation costs can decide whether you make money at all. You win by being close to customers and having the right distribution routes.

Here’s the key insight: these aren’t just “mines.” They’re geological lottery tickets that were won decades ago. New underground salt mine development in North America hasn’t happened in roughly 30 years. North America imports roughly 8 to 10 million tons per year of de-icing salt, and recent domestic mine closures removed around 4.5 million tons per year of capacity—while some legacy operations have faced their own operational challenges. The result is what looks a lot like regional oligopoly dynamics: not monopolies, but markets where new entry is brutally difficult.

And that history still drives Compass today. The mines, the locations, and the customer relationships built up through the consolidation era didn’t just create advantages—they created constraints. Compass doesn’t grow by casually building a new salt mine. It grows (or doesn’t) based on weather, pricing, and whether management can squeeze more value out of existing assets without lighting capital on fire trying to reinvent them.

III. Going Public and the Private Equity Playbook (2001–2006)

Private equity firms are usually cast as the villains of corporate folklore: load up the balance sheet, cut to the bone, flip it to the next buyer. But sometimes the playbook is exactly what a business needs. Compass’s early-2000s chapter is one of those cases—a commodity company, cleaned up and sharpened, then marched straight to the public markets.

On November 28, 2001, IMC Global sold its salt business (IMC Salt) and SOP business (Great Salt Lake Company) to affiliates of Apollo Management as part of a recapitalization effort, in a deal valued at roughly $640 million. Out of that transaction, Compass Minerals was formed: a portfolio of North American salt and specialty chemicals assets—thirteen salt-producing facilities spread across North America and the United Kingdom—assembled into a single platform under one owner.

Apollo’s rationale didn’t require a leap of imagination. Salt wasn’t trendy, but it was essential. Demand didn’t depend on consumer sentiment or corporate IT budgets. Roads still had to be safe, and municipalities still had to buy de-icing material. Better yet, the assets were hard to replicate. You can’t decide to build “a new Goderich” the way you decide to build a new warehouse. The geology either exists or it doesn’t, and permits and infrastructure take years.

In December 2002, Compass brought in Michael E. Ducey as President and CEO. He came with deep operating experience, having spent roughly three decades at Borden Chemical, including a stint as its President and CEO from December 1999 to March 2002.

With Apollo in control, the transformation followed the familiar private-equity script: tighten operations, impose cost discipline, and get the company into IPO shape. The business had previously been known as Salt Holdings Corporation. In December 2003, it took on the name Compass Minerals International, Inc.—a rebrand that signaled something important: this was no longer a carve-out. It was going to be a standalone public company.

The exit came fast. In December 2003, Compass went public on the New York Stock Exchange. It issued 16.675 million shares at $13 per share, raising about $217 million in gross proceeds before fees. The IPO helped set the company up for debt reduction and ongoing investment, and it put a real market price on what had been a private portfolio of mines, ponds, and contracts.

But the structure of the deal made one thing clear: this was, first and foremost, a liquidity event. After the reorganization, Apollo Management V, L.P., co-investors, and management owned about 81% of the fully diluted stock, while Mosaic retained 19%. When the IPO priced on December 17, 2003, the shares sold were from existing stockholders, meaning the proceeds largely flowed to Apollo and Mosaic rather than into Compass’s corporate bank account.

Credit Suisse First Boston and Goldman Sachs underwrote the offering, and Apollo didn’t waste time continuing its sell-down. In June 2004, there was a secondary offering of nearly 6.9 million shares. Three months later, Apollo filed to sell the rest. By the end of 2004, both Apollo and Mosaic had reduced their interest to zero—an ownership reset that also forced changes to a board that had been built for sponsor control, not life as a fully independent public company.

Early performance made the story easy to believe. In the years after the IPO, the company pointed to rapid growth in revenue, earnings, and operating cash flow. Compass looked like the ideal public-market version of a private-equity “fix”: essential product, cash generation, and a set of long-life assets that competitors couldn’t simply copy.

And as a newly independent company, Compass leaned into investment. It planned higher capital spending—up by $5 million in 2005 and $14 million in 2006—directing a meaningful share toward the Great Salt Lake operation: expanding magnesium chloride evaporation ponds, upgrading production facilities, and adding rail infrastructure.

For investors who bought in around the IPO, the pitch was almost boring in the best way: a stable, cash-generative business with modest growth, made more attractive by the kind of reliability that can support dividends. The stock rose through the mid-2000s.

But there’s a trap hiding inside “stable and boring.” Wall Street rarely leaves that alone. Once the market decides you’re predictable, the next question is always the same: what’s the growth story?

And in commodity businesses, chasing a growth story is where things tend to get dangerous.

IV. The Golden Years: Acquisitions and Expansion (2007–2015)

Success creates its own problems. By the late 2000s, Compass had done something most people wouldn’t bet on: it turned a salt company into a respectable public-market story. Earnings were steady. Dividends showed up like clockwork. The stock climbed, analysts paid attention, and management collected the kind of credibility that makes boards more willing to say yes. Years later, that glow was still visible—Compass was named one of Forbes’ 100 Most Trustworthy Companies in America in 2015 and 2016.

But the business still had a hard ceiling. How much can you really grow when your biggest product is a rock pulled out of the ground and your biggest customer is winter?

Highway de-icing demand lives and dies by the weather. A mild season doesn’t just trim the top line—it can wipe out volumes. Consumer salt is mature. Industrial salt is steady but slow. And the market tends to price commodity businesses accordingly: reliable, but not exciting.

So management faced a fork in the road. Either embrace the identity—slow growth, steady cash flows, dividend focus—or go find a second engine.

They went looking for that second engine.

The logic was defensible. Compass already had a foothold in specialty fertilizer through its Ogden operation on the Great Salt Lake, which produced sulfate of potash, or SOP. SOP sells at a premium to standard potash because it’s a better fit for certain crops, especially those sensitive to chloride. If Compass could build a real plant nutrition platform around that capability, it could smooth out the wild swings of the winter salt business.

In 2010, Compass launched its Plant Nutrition business alongside Salt, explicitly positioning it as diversification.

Then came bolt-ons. In 2011, Compass acquired Big Quill Resources in Canada, adding SOP production capacity at Wynyard, Saskatchewan.

But the biggest move was south—into Brazil. Compass signed a definitive agreement to buy a 35% stake in Produquimica Industria e Comercio S.A., described as one of Brazil’s leading manufacturers and distributors of specialty plant nutrients. The all-cash deal valued Produquímica at about R$450 million (roughly $120.7 million at the time), subject to typical closing adjustments.

Management sold the move as a gateway into one of the world’s most important agricultural markets. As CEO Fran Malecha put it, Produquímica had “a long history in Brazil,” plus “strong prospects for continued growth and margin expansion,” supported by specialty products, application technologies, and an established distribution network aimed at helping growers improve yields.

By December 2015, Compass owned that initial 35%. And it didn’t stop there. On October 3, 2016, Compass announced it had completed the purchase of the remaining interest. Total consideration for the rest of Produquímica was approximately $465 million.

The pitch was straightforward and, on its face, hard to argue with: the acquisition was described as accretive, exposed Compass to faster-growing markets, diversified earnings geographically, and—most importantly—reduced dependence on winter weather.

And the numbers appeared to back it up. From 2011 to 2015, Produquímica’s net sales and EBITDA grew at compounded annual rates of 16% and 19%, respectively.

From the outside, it looked like the cleanest kind of evolution: a dependable, “boring” salt company becoming a diversified essential minerals business with exposure to global agriculture—and, with it, higher margins and a better growth narrative.

By 2012, Compass reported total sales of $942 million and ended the year with a market capitalization of about $2.5 billion. Through the mid-2010s, the stock performed well, revenue rose, and management’s confidence showed. Ogden—already a rare asset in global SOP—was framed as the crown jewel: mineral-rich brine, solar evaporation, premium products.

But the best time to worry about a company is often when everything looks like it’s working.

In hindsight, the cracks were already there. Ogden wasn’t running the way the story implied. Brazil was heading into a brutal recession. And Compass was sketching out an aggressive plan to expand SOP production—an expansion that would turn the “second engine” into the company’s most dangerous bet.

V. The Ogden Gambit: When Bets Go Wrong (2016–2019)

Every corporate blowup has a “before” and “after.” For Compass Minerals, the dividing line ran straight through Ogden, Utah—and a decision to dramatically expand sulfate of potash production at the Great Salt Lake.

On paper, it was an easy story to sell. Ogden already produced SOP, salt, and magnesium chloride. It had meaningful capacity across all three, and management believed the real prize was SOP: premium pricing, growing demand from high-value crop growers, and a set of assets that looked almost impossible to replicate. This wasn’t a standard fertilizer plant. It was a sprawling solar evaporation system—about 55,000 acres of ponds—one of only a handful of SOP brine operations like it in the world.

But here’s what the slide deck can’t capture: you don’t “scale” a solar evaporation operation the way you scale a factory.

The system depends on weather, brine chemistry, and pond management—and the process itself takes years. Mineral-rich brine from the lake’s farthest reaches gets pumped into shallow ponds, where sun and wind slowly do the work. Over roughly three years, water evaporates away in stages, and different minerals crystallize out in sequence. If something goes wrong early in that chain, you don’t just lose a week of production. You can lose an entire season—or several.

When problems showed up, they didn’t stay contained. Production targets were missed. Costs climbed. Guidance got cut, and then cut again. The growth narrative that had helped justify all the investment started to unravel in public, quarter by quarter, as investors realized this wasn’t a temporary hiccup. It was a system that wasn’t behaving the way management had promised.

And Ogden wasn’t the only crack in the foundation.

Back in the core salt business, Compass’s flagship Goderich mine—often described as the crown jewel—hit its own operational shock. The company announced that the Goderich, Ontario rock salt mine was operating at reduced rates after geological movement led to a partial ceiling fall on September 18, 2017. No one was injured, but the incident damaged part of the mine’s main conveyance system. For a business built on reliability, that was the wrong kind of headline.

Then came labor trouble. Compass announced that the union representing 341 hourly employees at Goderich initiated a strike. The company said it had contingency procedures and expected to operate the mine at or near planned rates for 2018. The union’s version of events was less clinical. Representatives recalled: “We were at the table for probably 10 to 12 bargaining sessions, and the company gave no indication of even entertaining any of our proposals. They constantly kept bringing concessions to the table.”

Meanwhile, the diversification bet in Brazil—supposed to smooth out winter volatility and add growth—ran into the country’s economic crisis. Currency depreciation reduced the dollar value of results, and the agricultural market softened. Instead of becoming the stabilizer, it became another source of uncertainty.

The market response was swift and unforgiving. The stock—once above $90 at its peak—slid into a painful, grinding decline. Earnings disappointed. Credibility eroded. Credit rating agencies noticed.

Then the regulatory shoe dropped. The Securities and Exchange Commission announced settled charges against Compass Minerals for misleading investors about a technology upgrade the company claimed would reduce costs at Goderich but that, according to the SEC, had actually increased costs. The SEC also said Compass failed to properly assess whether to disclose financial risks tied to excessive mercury discharge in Brazil. Compass was ordered to pay $12 million to settle the charges.

According to the SEC’s order, Compass repeatedly assured investors in 2017 that the Goderich upgrade—at the world’s largest underground salt mine—was on track to materially reduce costs and improve results starting in 2018. The SEC’s Associate Director of Enforcement Melissa Hodgman summed up the core issue: “What companies say to investors must be consistent with what they know. Yet Compass repeatedly made public statements that did not jibe with the facts on—or under—the ground at Goderich.”

The allegations included repeated misleading statements about cost-reduction strategies, production levels at Goderich, and environmental compliance issues at a subsidiary facility in Brazil.

Inside the company, the stress showed up as churn. Management turnover accelerated. CEO Fran Malecha departed. The board installed an interim CEO. Investor confidence cratered.

The dividend story flipped too. After years of annual increases from 2005 through 2017, it was frozen—and then cut as Compass struggled to grow earnings.

By now, the soul-searching wasn’t theoretical. It was existential. Was this simply poor execution—fixable with better operators and enough time? Or had Compass tried to force an asset to do something it couldn’t do, at least not on the timeline and economics it had promised? Was Brazil still the right diversification move, or a mistake that needed to be unwound?

For anyone watching from the outside, it was a harsh reminder of the commodity-company paradox: the moat can be real—geology, permits, infrastructure, customer relationships—and you can still destroy enormous value with capital allocation and operational missteps. The earth can give you a cornered resource. It can’t give you discipline.

VI. Crisis Management and the Turnaround (2019–2021)

Turnarounds don’t start with vision statements. They start with someone walking in, looking at the mess, and saying: we’re going to stop pretending.

In April 2019, Compass made its choice. The company announced that Kevin S. Crutchfield would become president and CEO, and join the Board, effective May 7, 2019. Crutchfield came with more than 30 years in mining, most recently as CEO of Contura Energy, a publicly traded coal producer. Before that, he was chairman (2012 to 2016) and CEO (2009 to 2016) of Alpha Natural Resources.

His résumé wasn’t a clue. It was a message.

This wasn’t a glamorous “new economy” hire. Crutchfield was a mining engineer—Bachelor of Science in Mining and Minerals Engineering from Virginia Tech, plus the executive program at UVA Darden—who’d spent his career in industries where physics, geology, and fixed costs don’t care about your earnings call. The board wasn’t looking for financial alchemy. It was looking for operational discipline.

As the company put it at the time: “After a comprehensive search, our Board is delighted to welcome Kevin to Compass Minerals, and believes his proven track record as a CEO and his extensive mining experience will be critical both operationally and strategically as the company moves forward.”

The playbook was simple to describe and brutal to execute.

Step 1: Face reality. No more rosy promises. No more “next quarter it’ll be fixed.” Credibility had become a core asset—and Compass had run it down. The only way back was conservative guidance and clearer communication about what was actually happening on the ground.

Step 2: Fix what’s broken. Ogden needed technical help and operational focus. Goderich needed stability. And the company had to stop pouring cash into initiatives that weren’t delivering.

Step 3: Divest what doesn’t fit. In 2019, ICL announced it completed the acquisition of Compass Minerals América do Sul S.A., which included Compass’s South American Plant Nutrition business, for approximately US$420 million.

Crutchfield was blunt about it: “While the South American Plant Nutrition business is not part of our forward-looking strategy, we continue to believe the future is bright for these productive assets.”

Read between the lines and it’s even clearer: Brazil wasn’t the stabilizer it was supposed to be. Compass had spent nearly $600 million building that position and was now exiting for roughly $420 million—painful, yes, but also an admission that staying would mean throwing more capital after a strategy that no longer made sense.

Step 4: Repair the balance sheet. Reduce debt. Improve liquidity. Buy breathing room, because commodity businesses don’t get to choose their storms.

And then, as if the turnaround weren’t hard enough, the world piled on. The 2020–2021 period brought mild winters—the exact thing a de-icing salt producer can’t control and can’t afford. Then COVID-19 hit, and whatever rhythms the business relied on—from logistics to customer ordering patterns—got scrambled.

Compass still had real structural advantages. It operated in markets that behave like oligopolies, with assets and distribution networks that are incredibly hard to replicate. But advantages don’t automatically translate into attractive financials, especially when operations are unstable and fixed costs are high.

So the recovery looked like what real recoveries usually look like: slow. Uncelebrated. Measured in incremental gains—better reliability, lower costs, fewer surprises, safer operations. The stock stayed down. Skepticism stayed high. But the company began, gradually, to look less like it was spiraling and more like it was standing back up.

That’s the uncomfortable truth of commodity turnarounds: there’s no hack. Operational excellence isn’t a nice-to-have. It’s the business model. Strategy matters, but execution is the only thing that gets you paid—and rebuilding execution happens in years, not quarters.

VII. The Lithium Pivot: New Hope or New Hype? (2021–Present)

Just as the core business started to look steady again, Compass saw what looked like a once-in-a-generation escape hatch: lithium.

The timing couldn’t have been better—at least on paper. EV adoption was accelerating, battery demand was booming, lithium prices were ripping, and governments were throwing money at domestic supply chains. And out on the Great Salt Lake, in the same brine Compass had been pumping and processing for decades, there was lithium.

Compass announced it had hit several milestones and laid out a development plan for its previously identified resource of approximately 2.4 mMT lithium carbonate equivalent (LCE) on the Great Salt Lake. Phase one was expected to be located on the east side of the lake, where much of the company’s existing Ogden infrastructure already sat.

The story they told investors was elegant: lithium chloride would become the fourth mineral salt harvested from the same unit of brine already being processed. That meant, according to the company, minimal incremental environmental impact and no incremental brine draw from the Great Salt Lake.

They backed that narrative with specifics. Compass said it selected EnergySource Minerals as its direct lithium extraction (DLE) technology provider after three years of testing multiple DLE technologies. The project was framed as a low-cost, long-life brownfield build at the Ogden solar evaporation facility, leveraging existing infrastructure. The company targeted phase-one production of approximately 11 kMT of LCE annually, with estimated phase-one development capital of $262 million. It also presented an after-tax NPV range of roughly $626 million to $985 million and an after-tax IRR between 28%.

The market liked it. The stock responded enthusiastically as a new set of investors showed up—people less interested in winter road salt and more interested in “battery-grade lithium.” In that moment, Compass stopped being just a turnaround story and briefly became an energy-transition story.

And it got real financing behind it. Koch Minerals & Trading announced a $252 million investment in Compass Minerals to support phase-one development of the same Great Salt Lake lithium resource and to reduce debt. Compass said it believed it remained on track to enter the market with a cost-competitive, battery-grade lithium product by 2025.

Then reality arrived—this time from the statehouse.

The Great Salt Lake was shrinking. Water rights were turning into a political third rail. And lithium production on the lake wasn’t happening in a vacuum; it was happening under a spotlight.

In March 2023, Utah’s legislature passed House Bill 513, followed by a rulemaking process tied to lithium production on the Great Salt Lake. Compass said this introduced significant uncertainty around the regulatory environment.

And the uncertainty wasn’t subtle. “There’s nothing in [place] for an operator to extract lithium off the lake right now,” FFSL director Jamie Barnes told the Legislative Water Development Commission. “Nobody has a royalty agreement.”

Environmental concerns intensified too. “We’re struggling with the concept of furnishing that much water to one new industry that takes water away from the population,” advocates argued. A Great Salt Lake Strike Team report said mineral companies deplete 163,000 acre-feet from the lake each year—and of the extractors operating on the lake, Compass used the most.

By late 2023, Compass hit pause. CEO Kevin Crutchfield framed it as a capital discipline decision: “While we remain confident in the value creation potential of this project, we also have a responsibility to our shareholders to operate as prudent stewards of the capital we expend.” Without regulatory certainty, Compass said it would suspend the project indefinitely and focus on maximizing performance in its salt, plant nutrition, and emerging fire retardant businesses.

In early 2024, the pause became a stop. In a report to shareholders, Compass said its lithium development team in Ogden had been disbanded and the project would not go forward. “The environment surrounding our lithium project today is markedly different than the one that existed a couple of years ago when we started down this path,” the company wrote. “The simple fact is that the regulatory risks have increased significantly around this project. When combined with other changes to the commercial landscape, it became clear that the risk-adjusted returns on this project are inadequate to justify the investment.”

Compass said it had invested more than $77 million in its lithium projects.

So was this another Ogden-style fiasco—management reaching for a moonshot and lighting money on fire? Or was it the kind of adjacent bet you want a turnaround team to at least explore, only to shut down once the odds shift?

It’s probably both. The resource was real. The infrastructure synergies were real. The opportunity was real. But the regulatory environment moved faster than the company could underwrite, and the capital required to force the issue was hard to justify for a business still rebuilding its balance sheet and credibility.

For investors who bought into the lithium narrative, it was another gut punch. The energy-transition premium evaporated, and Compass was back where it started: a company whose future would be decided, once again, by operational execution in unglamorous, essential minerals.

VIII. The Business Model Deep Dive

Understanding Compass Minerals requires understanding how the company actually makes money—and why that’s simultaneously boring and fascinating.

The Salt Segment

Compass operates two business segments: Salt and Plant Nutrition. The Salt segment mines, produces, processes, and distributes sodium chloride and magnesium chloride across North America and the U.K. The biggest line inside that is highway de-icing: bulk rock salt sold to states, provinces, counties, municipalities, and the contractors who keep roads passable. The segment also includes consumer and industrial products.

Highway de-icing is the engine—and the roulette wheel. In harsh winters, demand spikes and the machine prints cash. In mild winters, orders fall off a cliff. But the costs don’t fall with them. Mines still need crews. Conveyors still need maintenance. Depots still need to run. That’s operational leverage in its rawest form: a mostly fixed-cost base riding on wildly variable demand.

In fiscal 2025, Salt segment revenue rose 13% year over year to $1,022.5 million. Management attributed that to a return to more typical winter conditions in North America, which drove a 20% increase in highway de-icing volumes. Chemical and industrial volumes were up slightly—consumer de-icing improved, offset by declines elsewhere.

Customer relationships add another wrinkle. Municipalities often sign multi-year contracts with pricing terms and committed volumes, which sounds like stability. But actual purchasing still depends on snowfall and ice. If winter doesn’t show up, the contract can’t force nature to cooperate. Compass can have “secured” business on paper and still feel the pain in the income statement.

The Plant Nutrition Segment

The Plant Nutrition segment produces sulfate of potash (SOP). Domestic SOP sales are concentrated in the Western and Southeastern U.S., with exports to Latin America, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand.

SOP earns its premium because it delivers potassium without chloride, which matters for chloride-sensitive crops like fruits, vegetables, and tree nuts. That typically allows SOP to sell for meaningfully more than standard muriate of potash (MOP).

And this takes us back to Ogden—because the economics here aren’t driven by slick marketing. They’re driven by chemistry, weather, and time. Compass operates a roughly 55,000-acre solar evaporation pond complex in Utah—one of only four in the world that can produce SOP from naturally occurring brine using solar evaporation. Brine is pumped into a series of shallow ponds, and over about three years, sun and wind evaporate the water in stages so different minerals crystallize out. When the system behaves, it’s a rare, advantaged asset. When it doesn’t, it can become an expensive lesson.

The Failed Diversification: Fortress Fire Retardants

Compass also tried another adjacent bet: fire retardants.

The company acquired the outstanding 55% interest in Fortress North America, taking its ownership to 100% after previously holding a 45% minority stake since January 2022.

Founded in 2016, Fortress developed proprietary magnesium chloride-based aerial and ground fire retardants. The tie-in was obvious: magnesium chloride is already produced at Compass’s Ogden solar evaporation facility. The pitch was elegant—turn an existing mineral stream into a higher-value product and add counter-seasonal revenue, with fire season in the summer and road salt in the winter. In December 2022, Fortress became the first new company in more than two decades to have long-term aerial fire retardants added to the U.S. Forest Service’s Qualified Product List.

Then it got complicated. After a more extensive inspection raised aircraft safety concerns, the USFS informed Compass on March 22, 2024, that it would be “unable to define the scope and associated terms and conditions of a new contract” until the NTSB and NIST completed a coordinated, independent assessment.

Compass recognized non-cash impairments related to Fortress of $47.6 million in the second quarter of 2024 and $53.0 million in the second quarter of 2025. In late March 2025, the company announced it was winding down the business.

It was another reminder of the company’s recent pattern: the core is hard enough. Adjacent “second engines” have not come easily.

Current Financial State

For fiscal 2025, Compass reported a net loss of $79.8 million, an improvement from a $206.1 million loss in fiscal 2024. Revenue increased 11% to $1.24 billion, while adjusted EBITDA declined 4% to $198.8 million.

The balance sheet story was more encouraging. Compass reduced net total debt by 14%, or $125 million, year over year to $772.5 million by fiscal year-end. It also completed a refinancing in the third quarter, which the company said improved flexibility, enhanced liquidity, and extended maturities. Liquidity stood at $364.6 million as of September 30, 2025.

Zooming out, the margin profile still tells you what kind of business this is: high fixed costs, big swings, and results that can look great—or ugly—depending on volume and execution. In fiscal 2025, the Salt segment generated adjusted EBITDA of $219.2 million, down 4% year over year. And because Compass curtailed production in 2024 to align inventory with business conditions, adjusted EBITDA per ton declined to about $20.20 per ton in fiscal 2025.

IX. Leadership, Culture, and Governance

Compass’s leadership story over the last decade is basically the company’s business story in miniature: big ambitions, painful operational reality, a hard-nosed turnaround, and then another reset.

When Kevin Crutchfield arrived in 2019, the board wasn’t hiring a visionary. It was hiring credibility—someone fluent in mines, fixed costs, and the kind of operational triage Compass desperately needed. He brought decades of relevant experience, including CEO roles at Alpha Natural Resources and Contura Energy, and he stepped into a company that had lost the market’s trust.

His tenure became defined by stabilization. Under Crutchfield, Compass sold the South American plant nutrition business, tried to get Ogden under control, and worked to shore up the balance sheet. He also pushed into new adjacency bets—most notably lithium at the Great Salt Lake—before the regulatory environment turned that plan into an indefinite suspension and ultimately a shutdown. Fortress, the fire-retardant effort tied to magnesium chloride, also failed to become the counter-seasonal growth engine the company hoped for.

Crutchfield eventually moved on. When he was appointed to Intrepid Potash in December 2024, he framed the new role in language that sounded familiar for anyone who’d watched his Compass playbook: “I am excited to join Intrepid, a company that is recognized for its high-quality, essential product, hands-on customer service, world-class team, and service to its communities.”

Edward C. Dowling Jr., the current CEO, inherited what was left: a company no longer in freefall, but still very much in transition—forced to simplify after years of trying to outrun its own fundamentals. Dowling put it plainly: “There is no doubt that 2024 was a transitional year for our company. We made the important strategic decision to get 'back to basics' by refocusing on our core Salt and Plant Nutrition businesses. We made leadership and organizational changes throughout the year to support this effort. Our company also had to confront the challenges resulting from one of the mildest winters in the last quarter century, as well as headwinds from the termination of our lithium project and setbacks in the Fortress business.”

A year later, he emphasized the direction of travel: “Compass Minerals today is a significantly healthier, more focused company than it was a year ago. The story of 2025 is primarily one of improving our financial position of the company and providing the foundation to pursue its back-to-basic business model.”

That “back to basics” framing matters, because Compass’s culture is, at its core, a mining culture: safety-first, operationally grounded, conservative by nature. That mindset is a feature when you’re running underground operations and long-cycle brine systems. But it can clash with the temptation to chase big, narrative-friendly growth moves—exactly the dynamic that got Compass into trouble in the first place.

Governance became part of the story during the crisis years, not just a footnote. The SEC found that Compass violated antifraud, reporting, and internal controls provisions under the Securities Act and the Exchange Act. Along with the civil penalty, Compass agreed to retain an independent compliance consultant to review and make recommendations on its disclosure controls and procedures.

For investors, the takeaway is blunt: in capital-intensive commodity businesses, the board’s job isn’t just approving strategy—it’s pressure-testing execution risk and making sure optimism doesn’t leak into disclosures as implied certainty. When credibility breaks, it’s expensive. And it takes years to earn back.

X. Strategic Frameworks: Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Porter's 5 Forces

Competitive Rivalry: In highway de-icing salt, rivalry looks moderate from 30,000 feet. The broader U.S. and Canadian markets include many producers and distributors—names like K+S, Compass, and Cargill among them. But on the ground, salt doesn’t behave like a normal national commodity market. It behaves like a set of regional markets, because transportation costs are so decisive. That reality—plus longstanding municipal relationships—creates pockets that feel like local oligopolies. In specialty fertilizers like SOP, the dynamic flips: competition is more global, and it’s more intense.

Threat of New Entrants: Very low for salt mining. The geology is scarce, the permitting is slow, and the capital requirements are real. Atlas Salt’s project matters precisely because it’s an exception: it represents the continent’s first major new salt mine development in roughly 30 years. In SOP, the threat is closer to moderate—there are only a handful of brine-based producers globally, but competition still exists, and customers can source alternatives.

Supplier Power: Low. Compass largely controls its own inputs because it owns the mines and mineral rights. The biggest variable isn’t a vendor squeezing them—it’s energy costs, like natural gas for processing.

Buyer Power: Moderate. The biggest customers in salt are municipalities and their contractors, and they do bid work out and push on price. There’s some stickiness from logistics and relationships, but alternatives exist. Pricing pressure is higher in commodity de-icing salt than in SOP, where the customer is often a grower making a more value-based decision for chloride-sensitive crops.

Threat of Substitutes: Low for de-icing salt at scale. There are alternatives, but nothing matches the combination of effectiveness and practicality for widespread winter road safety. For SOP, substitutes are also limited in the specific use case that makes SOP valuable: delivering potassium for chloride-sensitive agriculture.

Hamilton's 7 Powers

Scale Economies: Strong in regional salt markets, where fixed infrastructure and transportation economics reward large, well-positioned operators. Much less relevant in specialty products.

Network Effects: Not applicable.

Counter-Positioning: Not present. Compass isn’t disrupting anyone with a new model—it’s operating classic mining and extraction businesses.

Switching Costs: Moderate. Municipal relationships, depot networks, and delivery reliability create some inertia. But at the end of the day, salt is salt, and switching can be easier than it feels.

Branding: Weak in B2B commodities. Protassium+® has some recognition in specialty agriculture, but branding isn’t a durable moat here.

Cornered Resource: This is the key power. Compass’s advantage starts with what it owns, not what it markets. Goderich is the largest underground salt mine, spanning about 5,340 hectares, and the mine is expected to operate until 2094. In Utah, the roughly 55,000-acre solar evaporation pond complex is one of only four in the world of its kind. Those aren’t assets you can spin up with a fundraising round. They’re location-specific deposits plus permits, rights, and infrastructure that take decades to assemble. That is Compass’s primary moat.

Process Power: Developing, but not proven. Post-turnaround, “operational excellence” is the stated strategy. But the company’s recent history—especially the Ogden problems and the setbacks at Goderich—shows how hard it is to turn process into an enduring advantage. For now, this power is more ambition than track record.

Synthesis

Compass has real power where it matters most in minerals: cornered resources. The deposits, extraction rights, and installed infrastructure are exceptionally hard to replicate. But beyond that, the company has limited structural power. The lithium and Fortress chapters reinforced how treacherous it can be to chase “next engines” outside the core. For Compass, value creation comes down to one thing: executing reliably, year after year, and allocating capital with discipline inside the asset base it already has.

XI. Bull vs. Bear Case & Investment Thesis

The Bull Case:

Essential products in stable demand: Highway de-icing salt isn’t going away. When roads freeze, public safety requires a solution that’s proven, scalable, and available immediately. More broadly, the U.S. salt market is projected to reach USD 4.91 billion by 2032, supported by food-grade demand and continued industrial and de-icing use.

Cornered resources: Goderich and Cote Blanche, plus the Ogden facility, aren’t just “plants”—they’re hard-to-replicate geological assets with decades of embedded infrastructure. And because salt is so heavy and transportation is so expensive, local production and established distribution networks matter. North America still imports roughly 8–10 Mtpa of de-icing salt, which reinforces the advantage held by domestic operators that can reliably deliver.

Stabilizing operations: Management’s case is that the operational bleeding is slowing. As the company put it: “We have already ramped up both Goderich and Cote Blanche mines to more normal levels of production, which will result in a reduction of production costs per ton.”

Balance sheet improvement: The company has been paying down debt and refinancing to buy time and flexibility. The recent refinancing extended maturities and pushed the maturity wall out to 2030, easing near-term pressure.

Valuation: After years of disappointment, the bar is low. If Compass simply runs its core assets consistently—and avoids another “next engine” misstep—the stock could have more upside than investors currently expect from a bruised commodity name.

The Bear Case:

Execution risk: Compass’s recent history reads like a checklist of things that can go wrong in a capital-intensive business: Ogden SOP issues, the Goderich technology upgrade, Produquímica, then the lithium and Fortress chapters. At some point, it starts to look less like bad luck and more like a recurring execution problem.

Weather dependency: The core Salt segment still lives at the mercy of winter. One of the mildest winters in the last quarter century can gut demand and earnings, and that volatility can keep many investors on the sidelines no matter how “essential” the product is.

No growth engine: With lithium terminated and Fortress wound down, Compass is back to its original identity: a slow-growth salt and SOP business. Without a credible new leg of growth, it’s hard to see why the market would pay a higher multiple.

Debt burden: Leverage is still elevated. The consolidated total net leverage ratio was 4.9 times. If operations stumble or weather turns uncooperative, the balance sheet can tighten fast.

Climate change: Warmer winters over the long run are a structural headwind for de-icing volumes, even if year-to-year variability still creates occasional “big winter” windfalls.

What to Watch (Key Performance Indicators):

-

Highway de-icing sales volumes and pricing: This is the Salt segment’s heartbeat, and it’s heavily weather-driven. Watch how actual volumes compare with contract expectations, and whether pricing holds in bid cycles.

-

Salt segment adjusted EBITDA per ton: A clean read on operating efficiency. In fiscal 2025, EBITDA per ton fell from $24.60 to $20.20 after production curtailments; it should improve if production normalizes and costs come down.

-

Net leverage ratio: At 4.9x today, against a covenant of 6.5x, deleveraging is still the clearest signal that the turnaround is sticking—and that Compass has room to breathe.

XII. Lessons for Founders, Operators & Investors

The Commodity Paradox: Essential products can come with brutal economics. Salt keeps highways safe and economies moving, but that doesn’t mean it reliably creates shareholder value. When your product is interchangeable and demand is dictated by the weather, “essential” can still translate into lumpy earnings, weak pricing power, and long stretches where the stock goes nowhere.

Diversification Risks: Compass is a case study in how hard it is to bolt on a “second engine” to a commodity core. Brazil, lithium, and fire retardants were all adjacent enough to sound reasonable in an investor presentation. In practice, each one introduced new operational, regulatory, or execution risk—exactly the kinds of risks you take on when you leave your circle of competence.

Capital Allocation as Value Destruction: In businesses like this, capital allocation is the whole game. The roughly $600 million put into Produquímica, the more than $77 million spent pursuing lithium, and the money tied up in Fortress represent capital that didn’t go to paying down debt, strengthening the core operations, or returning cash to shareholders. For a fixed-cost commodity company, “growth” spending can be the fastest way to dig a deeper hole.

The Turnaround Playbook: Crutchfield’s era followed the classic turnaround sequence: stop the spin, focus on operational basics, sell what doesn’t fit, and buy time by repairing the balance sheet. That’s what survival looks like. But turnarounds are slow, they demand investor patience, and they rarely recreate the value that was destroyed during the boom-time bets.

Optionality vs. Core Business: The lithium chapter is a clean example of how optionality works—and how it can backfire. It created real excitement and briefly re-rated the story, but it also pulled attention toward a moonshot that depended on a shifting regulatory environment. When the odds changed, Compass walked away and returned to the core. That outcome is a reminder: optionality is not a strategy if the core isn’t already stable.

Cornered Resources Matter—But Execution Matters More: Compass’s moat is real: Goderich, Cote Blanche, Winsford, and the Ogden pond system are not assets you can replicate quickly, if at all. But a cornered resource only becomes a cornered advantage when the company runs it well—consistently, safely, and predictably. Compass has the geology. The enduring question is whether it can convert that into dependable performance.

For Investors: Low multiples aren’t the same thing as value. Compass looked “cheap” for years because the market didn’t trust execution, didn’t trust the growth pivots, and didn’t trust guidance. In a commodity business, real value requires both scarce assets and the discipline to run them and allocate capital without self-inflicted wounds.

XIII. Epilogue: The Road Ahead

As of late 2025, Compass Minerals finds itself at yet another hinge moment—only this time, the story is less about bold new bets and more about earning back the right to be boring.

For fiscal 2026, the company guided to consolidated adjusted EBITDA of $200 million to $240 million. Within that, it expected the Salt segment to deliver adjusted EBITDA of $225 million to $255 million. In other words: the core salt engine is still the center of gravity, and the path forward runs through execution.

The lithium dream is dead, at least for now. Compass said it “will continue to monitor and engage in legislative and regulatory processes in Utah to preserve the long-term optionality of the lithium potential at its Ogden operations.” But that’s not a plan to build—it’s a plan to keep the door cracked open.

Fortress, the fire-retardant business that was supposed to turn magnesium chloride into a counter-seasonal growth engine, has been wound down too. Another attempt at diversification, another reminder that “adjacent” doesn’t mean “easy.”

So what’s left is a simpler Compass: salt and plant nutrition, run as well as possible, with the financial agenda stated plainly. As the company put it: “With advantaged assets and a renewed focus on operational, commercial, and financial performance, we are prioritizing stronger cash generation and the reduction of absolute debt. This combination positions Compass Minerals well to generate long-term value for shareholders.”

Potential Scenarios:

Best case: Winters look normal. Goderich and Ogden keep getting more reliable. Debt comes down steadily. Over time, investors start to believe the turnaround is permanent, not temporary—and the stock rerates as confidence returns.

Base case: Earnings stay lumpy because weather is lumpy. Operations improve, but slowly. Returns are steady, not spectacular. Compass remains what it fundamentally is: a small-cap commodity company that gets loved when winter is harsh and ignored when it isn’t.

Worst case: Another operational shock lands at the wrong time, paired with a run of mild winters. Cash generation weakens, leverage becomes a problem again, and Compass is forced into unattractive choices—raising equity, selling assets, or ultimately being acquired at distressed prices.

The Bigger Picture:

Compass is a useful parable about American industry. The most essential businesses are often the least glamorous: the ones that keep roads safe, move bulk materials, and extract minerals from the earth. They can be fantastic assets and still be difficult public companies. Quarterly expectations don’t mix naturally with weather-driven demand, long-cycle operations, and capital-intensive infrastructure. That mismatch can create a constant temptation to “fix” the growth story with diversification—even when diversification is exactly what adds risk.

Maybe Compass is better suited to private ownership, where patient capital can tolerate volatility without demanding a new narrative every year. Or maybe the right answer is simpler: a stable equilibrium where Compass accepts what it is—a slow-growth, utility-like essentials business—and focuses relentlessly on operational excellence and disciplined capital allocation.

What’s not in doubt is the company’s quiet relevance. Every time you drive on a salted highway, every time SOP helps a grower protect yield in chloride-sensitive crops, Compass’s mines and brine systems are doing their unglamorous job.

Sometimes the most interesting companies are the ones you pass every winter without noticing. Compass Minerals is one of them—a 170-year-old story of salt, ambition, failure, and reinvention that is still being written.

XIV. Further Reading & Resources

If you want to go deeper—into the geology, the capital allocation decisions, the SEC fallout, and the broader commodity context—these are the sources worth your time.

Top 10 Long-Form References:

- Company SEC filings: The 10-Ks from 2015–2024 are the unfiltered record of the run-up, the Ogden problems, the balance-sheet stress, and the turnaround work.

- "The Salt Fix" by James DiNicolantonio: A useful primer on salt’s role in society and health—and why it’s never been a “simple” substance.

- "The Prize" by Daniel Yergin: A masterclass in how commodity industries really work when you zoom out far enough.

- USGS Mineral Commodity Summaries: The annual baseline for salt, potash, and lithium—production, consumption, and the bigger supply-demand picture.

- "The Alchemy of Air" by Thomas Hager: Fertilizer history and context, and a reminder that “plant nutrition” has always been tied to big bets and big consequences.

- Credit research reports: Moody’s and S&P commentary during the crisis years is often more candid than equity research, especially on leverage and downside risk.

- "Buffett: The Making of an American Capitalist": Helpful for understanding the mental models Buffett used to think about commodity-like businesses—where moats are thin and discipline matters.

- Benchmark Mineral Intelligence publications: Solid lithium-market context for understanding why the lithium pivot looked so compelling—and why it still wasn’t a layup.

- SEC enforcement action (2022): The primary source on Compass’s disclosure failures, and how the SEC viewed the gap between internal reality and external messaging.

- MIT Sloan case study "Ventures in Salt: Compass Minerals International": Academic perspective on the IPO era and early public-company strategy.

Additional Resources: - Compass Minerals investor presentations (2019–2025) on the investor relations website - Great Salt Lake journalism and collaborative reporting on lithium, water rights, and regulatory uncertainty - Unifor documentation and public materials on the 2018 Goderich strike - Environmental Registry of Ontario filings related to the Goderich mine lease renewal

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music