Cummins: Powering Through a Century of Innovation

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

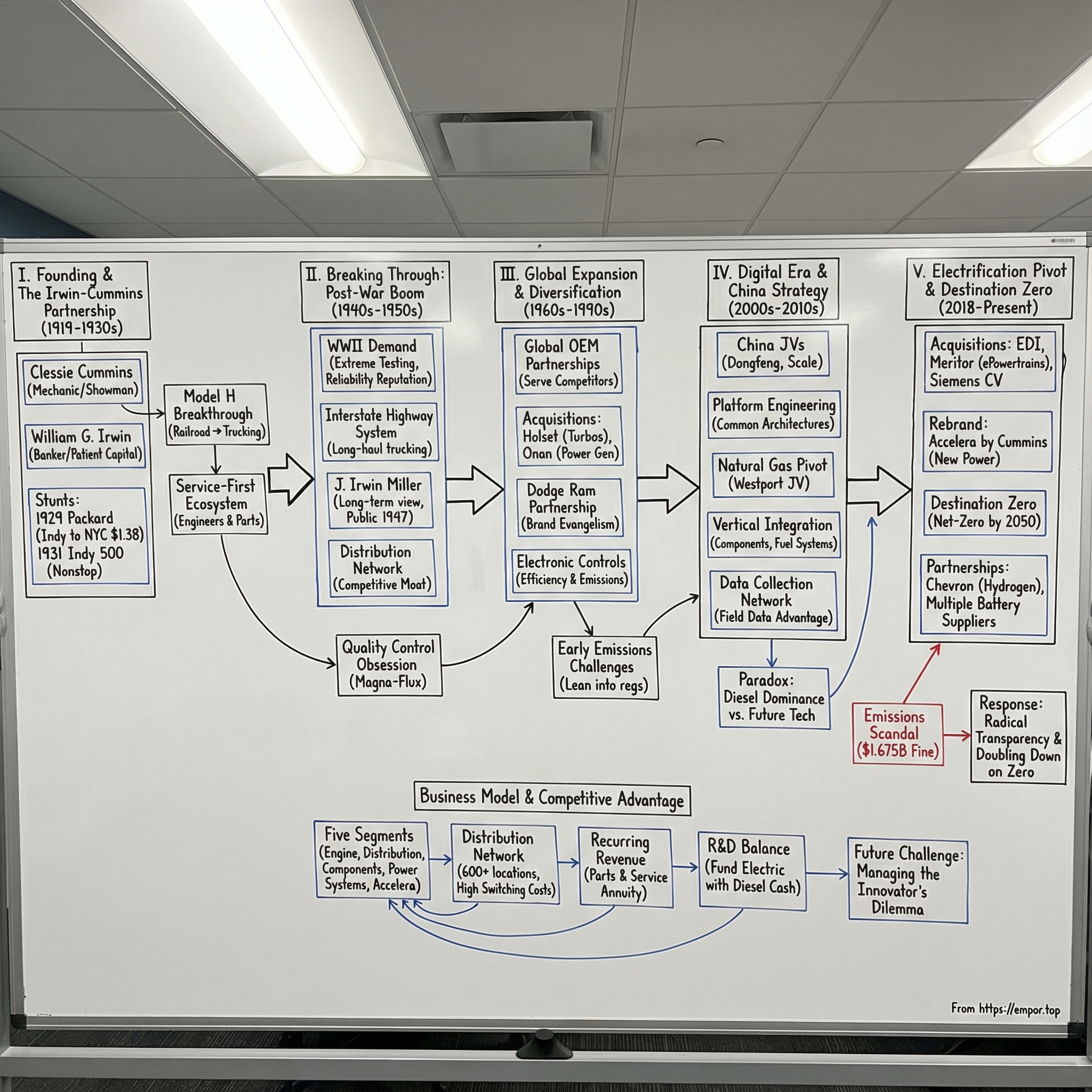

In Columbus, Indiana—a town of barely fifty thousand people—sits the headquarters of a company that powers an astonishing share of America’s heavy-duty trucks. Cummins Inc. doesn’t make the trucks. It makes what makes the trucks go: engines, turbochargers, filtration systems, power electronics—and, increasingly, the batteries and electric drivetrains that could one day replace combustion altogether.

With a market cap around $49 billion and trailing twelve-month revenue near $34 billion, Cummins holds a rare place in industrial America. It’s a legacy diesel giant and, at the same time, one of the more serious incumbents betting on zero-emissions tech. It sells to OEMs that compete fiercely with each other. It operates in nearly two hundred countries. And it’s been doing it, in some form, since 1919.

So here’s the question that makes this worth your time: how did a small Indiana mechanic shop—founded by a tinkerer and his banker—become the world’s dominant independent engine maker, and then decide to spend billions preparing for a future where diesel isn’t king?

That’s not just a history story. It’s a strategy story. A capital allocation story. And a test of whether a century-old company can move fast enough to survive an energy transition that’s rewriting the rules for transportation and power.

Because that’s what Cummins is trying to do: keep milking a diesel business that still throws off enormous cash, while building the next Cummins through Accelera, hydrogen engine development, and a long run of acquisitions that stretches from Silicon Valley all the way to the mining pits of Australia.

To understand how they got here, we have to go back to 1919—to a mechanic named Clessie, a banker named Irwin, and a masterclass in engineering showmanship that helped drag diesel into the mainstream.

II. Founding Story & The Irwin-Cummins Partnership

Cummins doesn’t start in a boardroom. It starts in a driveway—with a chauffeur and the man riding in the back seat.

Clessie Lyle Cummins was a self-taught mechanic from rural Indiana, the kind of person who seemed to understand machines the way other people understand language. By twelve, he’d built and run his own steam engine. He could fix almost anything. But what made him unusual wasn’t just mechanical talent—it was that he knew how to make people pay attention.

William Glanton Irwin couldn’t have been more different. He was a Columbus, Indiana banker: quiet, careful, methodical. He ran the Irwin-Union Trust Company, and Clessie worked for him as a driver and mechanic. Over time, Irwin came to see that Clessie wasn’t just keeping cars running. He was building capabilities. And Irwin—measured as he was—decided this was a mind worth backing.

On February 3, 1919, they founded the Cummins Engine Company. Their bet was diesel, a technology invented by Rudolf Diesel in the 1890s that still felt, to most of the market, like an industrial curiosity. Diesel engines were big, loud, temperamental machines—fine for stationary equipment and marine use, but ridiculous, people thought, for cars or trucks. Clessie disagreed.

The first decade punished that optimism. Cummins started with marine diesels, but the business was slow, the economics were ugly, and losses piled up. The Irwins kept funding the experiment anyway—patient capital before the phrase was fashionable. But by the late 1920s, even a supportive family and a friendly bank had limits. Pressure mounted. Liquidation became a real possibility. Cummins was running out of time.

Clessie’s response wasn’t to write a memo or tighten a budget. He put on a show.

In 1929, with the company on the brink, he installed a diesel engine in an automobile—an early successful attempt at something most people considered impractical—and drove it around to prove it could work. Then he went bigger. In 1930, he drove a diesel car from Indianapolis to New York City, roughly 800 miles, and spent just $1.38 on fuel. He timed it to the New York Auto Show, where the stunt landed exactly as intended: reporters swarmed, skeptics leaned in, and diesel suddenly had a story people could repeat.

And then came the Indianapolis 500. That same year, Clessie entered a Cummins diesel-powered car. It didn’t win. It finished twelfth. But it completed the entire race without a single pit stop—an endurance flex in a sport built on speed, noise, and constant drama. The message was simple and memorable: this engine wasn’t just efficient. It was dependable.

Those stunts didn’t instantly turn Cummins into a commercial powerhouse. But they bought something just as important in the moment: credibility. The Irwin family, now convinced diesel had real legs beyond the workshop, stayed in the fight.

In hindsight, that commitment reads like a foundational myth, but it was a very real financial risk at the time. The Irwins kept backing a money-losing engine company long before the market validated the bet. That same family wealth would later shape Columbus itself—through the Irwin-Sweeney-Miller Foundation and a wave of landmark architecture commissioned from designers like Eero Saarinen and I.M. Pei. But in the late 1920s and early 1930s, the more consequential wager was much smaller and much stranger: trusting a mechanic with a flair for spectacle to drag diesel into the mainstream.

Together, Irwin and Cummins set the company’s enduring template: engineering ambition paired with financial discipline, technical risk-taking supported by long-term capital. It was a combination that could survive lean years—and, eventually, scale.

III. Breaking Through: The Model H and Post-War Boom (1930s–1950s)

If the 1930s were a brutal time to be alive, they were also a brutal time to waste fuel. And that’s what made diesel’s core promise—more work per gallon—go from “interesting” to “urgent.” The Great Depression didn’t create demand for new technology out of generosity. It created demand out of necessity.

Cummins’ first real breakout came in 1933 with the Model H. Up to that point, the company had lived largely in the world of big marine and stationary engines: impressive, but narrow, and hard to scale. The Model H was different. It was built for a specific job that ran day in and day out: small railroad switchers—the yard locomotives that shuffle railcars short distances. Not glamorous. Just constant. And in that grind, the Model H did exactly what it needed to do: it ran reliably, it ran efficiently, and it started to generate repeat orders. For the first time, Cummins had something that looked like a repeatable business, not just a clever invention.

More importantly, the Model H established a playbook Cummins would run for decades: find a segment where economics matter more than tradition, prove diesel is better in the real world, and expand from that foothold into adjacent markets. Do that enough times and you don’t just sell engines—you change what the industry considers normal.

Then World War II poured gasoline on the fire—ironically, by making diesel even more valuable. The military needed dependable engines for trucks, generators, and marine vessels, and Cummins had already spent years getting good at the unsexy part of engineering: durability. The wartime work brought volume, production discipline, and hard engineering problems that couldn’t be solved with marketing. The war wasn’t just revenue. It was a proving ground. If an engine could survive wartime conditions, it could survive life on the road.

The real boom hit after the war. The U.S. economy surged, highways expanded, and trucking exploded into a backbone industry. Cummins walked into that moment with exactly the right product. Its N Series engines, introduced in the late 1940s, went on to capture more than half the heavy-duty truck engine market from 1952 to 1959. A company headquartered in a small Indiana town had built an engine family that powered the majority of America’s long-haul freight during the country’s biggest infrastructure buildout.

That kind of dominance wasn’t only about a great engine. It was about everything around the engine. Cummins invested heavily in a national network of distributors and service centers, and that network became one of its most enduring advantages. Because when you’re hauling freight, an engine isn’t a spec sheet—it’s uptime. A driver stranded on a highway doesn’t care about elegant engineering. He cares about parts, expertise, and how fast help can arrive. Cummins understood that early, and built the support system before many competitors even realized it mattered.

In 1947, Cummins went public, moving from the Irwin family’s private backing to the public markets. But the long-term mindset that patient capital had embedded didn’t disappear with the IPO. If anything, the listing gave Cummins more oxygen—more resources to keep investing in R&D, manufacturing, and that distribution moat.

A small detail from this era captures the culture: Cummins became the first engine manufacturer to use Magna-Flux, a non-destructive metal testing technique, as part of quality control. It sounds like trivia until you realize what it signals. Cummins wasn’t content to test engines at the end and hope for the best. It wanted to engineer quality into the process. In a business where failure is expensive and reputation is everything, that obsession compounds.

By the end of the 1950s, Cummins had completed a remarkable transformation. It went from a diesel stunt at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway to the dominant force in American diesel for heavy-duty trucking. The distribution network was spreading. The engineering culture was set. And maybe most strategically important of all, Cummins had proven a counterintuitive idea: an independent engine maker—selling to everyone, owned by no one—could beat the vertically integrated truck manufacturers at their own game. That independence became the foundation for everything that came next.

IV. Global Expansion & Diversification (1960s–1990s)

By the early 1960s, Cummins had done the hard part in the U.S.: it had become the name in heavy-duty diesel. The next question was tougher than it looked. Could a company built in small-town Indiana export that dominance to the rest of the world?

The first real move came with an assembly plant in Shotts, Scotland, in the early 1960s. On paper, it was just a facility. In practice, it was a statement: Cummins wasn’t going to be a company that shipped engines overseas and hoped for the best. It was going to show up. International markets wanted local manufacturing, local service, and products tuned to local realities. An engine that thrived on American interstates might need different calibrations and configurations for European roads, African mines, or Asian construction sites.

As Cummins pushed outward, it leaned into a business model that was both powerful and precarious: be the independent engine supplier of choice. That put it in a different lane than companies like Caterpillar, which built both the equipment and the engines, and unlike truck makers with captive engine divisions like Volvo and Daimler. Cummins was the Switzerland of engines—able to work with almost anyone, owned by no one. But independence came with a price: if you’re not vertically integrated, you don’t get guaranteed demand. You earn it, order by order, by being better.

One of the era’s most important relationships started in 1988, when Cummins began supplying a 5.9-liter inline-six diesel for the Dodge Ram pickup. Over time, that engine line expanded, including a later move to a 6.7-liter version in 2007. It became more than a supply deal. For Dodge, and later Ram, the Cummins diesel turned into an identity—an engine people asked for by name. For Cummins, it was a rare kind of marketing in an industrial business: hundreds of thousands of rolling billboards, plus a long tail of parts and service revenue that lasted far beyond the initial sale. The relationship endured for decades, which is almost unheard of in an industry where supplier ties can reset with every new vehicle cycle.

Cummins also started buying its way into key technologies. In 1973, it acquired Holset, a British turbocharger manufacturer. Turbocharging—forcing more air into the cylinders so an engine can make more power without getting bigger—isn’t a nice-to-have in diesel. It’s core performance. Owning that capability gave Cummins control over a component that directly shaped fuel efficiency, power, and reliability. More importantly, it foreshadowed a shift in strategy: Cummins didn’t just want to sell engines. It wanted to own more of the system around the engine.

That theme showed up again, even more dramatically, with Onan. The Onan acquisition stretched from 1986 to 1992 and pulled Cummins into power generation: generators, transfer switches, and backup power systems. The underlying engineering was familiar, but the customers and use cases were different—hospitals, military installations, remote job sites, and later the kind of infrastructure that can’t afford downtime. The Onan business became Cummins Power Generation, and it gave the company a second major leg to stand on. Decades later, as data center demand surged, that leg would matter even more.

This period wasn’t a straight-line growth story. The 1980s and 1990s brought real threats, including rising Japanese competition—Komatsu in particular—in construction and mining equipment. These companies showed up with lean manufacturing, disciplined operations, and aggressive pricing. Cummins responded the way it tended to respond: it improved its own manufacturing processes and leaned hard into what rivals couldn’t copy overnight—quality, uptime, and a service footprint that kept customers running.

By the time Cummins rebranded in 2001—dropping “Engine” and becoming Cummins Inc.—the name change was simply catching up to reality. Engines were still the core, but the company’s identity was widening. Turbochargers, filtration, fuel systems, and aftertreatment were becoming a business in their own right. Power generation had become a meaningful platform. Cummins was turning into a broader power-technology company, even as diesel remained the economic engine of the whole machine.

And threading through all of it was the quiet superpower Cummins had been building since the postwar boom: distribution. By the late 1990s, it had assembled a global web of more than 600 company-owned and independent distributors, plus thousands of dealer locations. That network didn’t just help sell engines—it produced recurring, higher-margin parts and service revenue that softened the cyclicality of new equipment sales. It also made Cummins harder to dislodge. You can compete on price. You can even compete on specs. But competing with a service and support system that took decades to build is a different kind of fight—and it’s one most challengers can’t afford to take on.

V. The Digital Era & China Strategy (2000s–2010s)

If the twentieth century was about making diesel work, the twenty-first century was about making diesel clean. Starting in the early 2000s, regulators in the U.S. and Europe—and increasingly across Asia—began tightening the screws on what could come out of a tailpipe, especially nitrogen oxides (NOx) and particulate matter, the soot linked to smog and respiratory illness.

For Cummins, that wave of regulation landed as both a threat and a gift. Every new standard meant expensive reengineering and relentless R&D. But it also raised the bar for everyone else. Keeping up with frameworks like EPA Tier 3 and Tier 4, and Europe’s Euro V and Euro VI, wasn’t just about designing a better engine—it was about building an organization that could hit moving targets, again and again. Smaller competitors and many in-house OEM engine programs struggled to match the pace. Cummins, with scale and deep engineering benches, could amortize the cost of compliance across huge volumes. In effect, every tightening cycle made the moat a little wider.

The engine itself was changing, too. Cummins poured investment into electronic engine controls—turning the diesel from a mostly mechanical machine into something closer to a computer-managed system. Fuel injection, timing, and combustion weren’t set once and left alone; software adjusted them constantly to balance power, efficiency, and emissions. This wasn’t a side upgrade. It was a shift in what “engine technology” meant. And it built a capability Cummins would lean on later, when propulsion started to look less like pistons and more like power electronics.

At the same time, Cummins made a geographic bet that would reshape the company: China.

Breaking into China meant playing by China’s rules, which often meant joint ventures. It wasn’t just regulatory necessity; it was also practical. You needed local partners who understood the market, the customer relationships, and the way policy could change. Cummins’ two most important beachheads were Dongfeng Cummins and the Beijing Foton Cummins Engine Company.

The payoff was enormous. The ISG and X12 platforms became staples in China’s commercial vehicle market, with production surpassing 240,000 units per year. This was the era of China’s infrastructure surge—highways, cities, industry—built at a pace that made the West look slow. Demand for durable, locally supported diesel engines was insatiable, and Cummins was in-country, manufacturing with partners who knew how to navigate the landscape.

But China didn’t come as a simple growth story. Joint ventures meant shared economics and shared know-how. Policy risk was always present. And the long-term national strategy was clear: build domestic capability that could eventually rival foreign suppliers. For Cummins, China became both an accelerator and an exposure—too large to ignore, too complex to ever treat as “solved.”

By 2013, Cummins’ footprint reached 197 countries, and it placed another bet—this time on fuel. Working with Westport Innovations (later WPRT), Cummins began offering natural gas versions of its heavy-duty engines. The pitch to fleets was straightforward: natural gas could be cheaper than diesel and burned cleaner, especially attractive in predictable-route applications like refuse trucks and regional hauling. It didn’t replace diesel, but it mattered strategically. Cummins was signaling that it would follow customer economics, even when that meant pushing an alternative to its own core product.

That instinct—to adapt early, even at the risk of cannibalizing yourself—became one of Cummins’ most important cultural advantages heading into the next era. Because in transportation, disruption rarely asks permission. The companies that survive are the ones that practice changing before they’re forced to.

VI. The Electrification Pivot & Destination Zero (2018–Present)

In 2018, Cummins hit a strategic hinge point. It acquired Efficient Drivetrains Inc. (EDI), a Silicon Valley company building hybrid and electric power solutions for commercial vehicles. The deal was small compared to Cummins’ overall footprint, but the message was loud: the world’s best-known independent diesel engine maker was now putting its name—and capital—behind electrified power.

This wasn’t framed as a panic move. Under CEO Tom Linebarger, who led Cummins from 2012 to 2023, the company rolled out “Destination Zero,” a commitment to reach net-zero emissions by 2050. The logic was straightforward and, for Cummins, deeply pragmatic: decarbonization wouldn’t arrive in one clean wave. A long-haul truck in Montana, a mining excavator in Chile, and a city bus in Shenzhen wouldn’t transition on the same timeline or with the same technology. So Cummins aimed to sell across the whole menu—cleaner diesel and natural gas where that’s what customers can use today, and electric and hydrogen systems where customers are ready for the leap.

Then came a run of capability-building acquisitions. Cummins bought Johnson Matthey’s battery systems division and Brammo, adding lithium-ion battery pack manufacturing and engineering talent. These weren’t “cool tech” trophies. Cummins needed the hard, unglamorous know-how of electrification—battery pack design, power electronics, and thermal management—skills that don’t come standard in a century-old diesel organization.

The biggest statement arrived in August 2022, when Cummins closed its $3.7 billion acquisition of Meritor, a long-established maker of drivetrain components like axles and brakes—and, most importantly, electric powertrain systems. The crown jewel was Meritor’s eAxle technology, which integrates an electric motor, transmission, and axle into a single unit. That integration matters because it simplifies the drivetrain and can bring costs down. With Meritor in the fold, Cummins could credibly pitch OEMs on a more complete electric powertrain stack: batteries, motors, power electronics, and drivetrain—delivered by one supplier, supported by the same industrial service mindset Cummins has always sold.

Meritor also brought another layer of electric capability in Europe. Through Meritor, Cummins acquired Siemens Commercial Vehicles for about €190 million. The Meritor business has been integrated within Cummins’ Components segment, with the company targeting about $130 million in annual cost synergies.

In 2023, Cummins put a clearer name on the future it was building. It reorganized its electrification efforts under Accelera by Cummins, replacing the old “New Power” label. The rebrand wasn’t cosmetic—it was a flag in the ground that this was meant to scale. Accelera spans batteries, eAxles, fuel cells, electrolyzers for hydrogen production, and integrated electric powertrain systems. In 2024, the segment generated $414 million in revenue—just over one percent of company sales—small today, but positioned as the platform Cummins wants to grow into tomorrow.

The price of that ambition shows up in the numbers, too. Accelera posted an EBITDA loss of $431 million in 2024, including $312 million in strategic reorganization charges. Cummins also took a $240 million non-cash charge tied to its electrolyzer business and launched a strategic review of that operation as losses mounted and policy support for green hydrogen subsidies looked uncertain. This is what transitions actually look like in real companies: the new engine of growth burns cash, while the old engine funds the experiment.

In February 2025, Cummins added another, very Cummins-style angle on decarbonization: make the existing fleet cleaner, faster. It acquired key assets of First Mode, a startup that developed retrofit hybrid systems for ultra-class mining haul trucks. First Mode’s approach converts existing diesel-electric mining trucks to hybrid operation with minimal modifications and no new infrastructure, reducing fuel consumption by up to 25 percent. The deal came through bankruptcy after First Mode lost funding from Anglo American, and Cummins reportedly bid around $15 million for the assets. The appeal is obvious. There are thousands of these haul trucks globally, each burning staggering amounts of fuel. A retrofit that can shave a quarter off that bill doesn’t need a climate speech to justify itself—it can win on pure economics.

Cummins also acquired Jacobs Vehicle Systems, adding engine braking and cylinder deactivation technologies that improve efficiency for conventional diesel—even as the company pushes hard into electrification. That’s the balancing act in one sentence: keep optimizing the core business while you build its eventual successor.

Hydrogen is part of the picture, too. Cummins completed “Project Brunel,” a consortium effort that produced a 6.7-liter hydrogen internal combustion engine with more than a 99 percent reduction in tailpipe carbon emissions compared to diesel. The company’s X15H hydrogen engine, under the Cummins HELM platform, points to a route for operators who need near-zero-carbon operation but can’t realistically run battery-electric—think long-haul routes far from charging infrastructure, or industrial sites where uptime and logistics make charging impractical.

Accelera also helped form Amplify Cell Technologies, a battery cell joint venture with PACCAR and Daimler Truck. The subtext is important: when two of the world’s biggest truck makers show up as partners, it signals that the scale economics of batteries may require cooperation—even among competitors. And on the public funding side, Accelera received a $75 million Department of Energy grant—the largest federal grant ever awarded solely to Cummins—matched by the company, for a total $150 million investment in zero-emissions manufacturing capacity.

Destination Zero is ambitious, expensive, and uncertain by design. But Cummins is attempting it from a position of unusual strength: a diesel business that still throws off billions in cash flow. That’s the central tension inside modern Cummins. The legacy business pays for the future. The future is being built to eventually replace the legacy. Managing that handoff—without breaking either side—is the defining challenge of the next decade.

VII. Partnerships & Strategic Alliances

One of the strangest—and most powerful—things about Cummins is that it thrives by selling to rivals. It will put its engines and powertrains into vehicles made by OEMs that compete fiercely with each other, and sometimes even compete with Cummins’ adjacent businesses. It’s the Switzerland strategy: stay independent, stay indispensable, and never let customers feel like you’re playing favorites.

In 2023, Cummins and Chevron signed a memorandum of understanding to collaborate across hydrogen, natural gas, and other lower-carbon fuel value chains. It was a classic “two halves of the same problem” pairing. Cummins can build the engines and power systems, but fuel transitions don’t happen if nobody produces the fuel or builds the distribution network. Chevron can do that. By 2025, the relationship had moved beyond research-mode, with Chevron developing hydrogen fueling stations in California and Cummins continuing to advance its hydrogen engine portfolio.

This partnership-driven OEM model is an underappreciated strategic asset. By supplying power to companies like Daimler, PACCAR, Navistar, and others, Cummins gets something that most captive engine divisions can’t replicate: scale across brands. Every additional OEM customer spreads Cummins’ R&D and compliance costs across more volume, which lowers the per-engine burden and helps fund the next wave of technology. And for the OEMs, the trade is simple: they get access to Cummins’ engineering depth and service support without having to carry the capital and complexity of running a full in-house engine program.

In emerging markets, Cummins has used joint ventures as the entry strategy, especially in China and India. The logic is practical: local partners help navigate regulation, market structure, and customer relationships, while also sharing the capital load. In China, Dongfeng Cummins and Foton Cummins became major production platforms, turning out hundreds of thousands of engines a year. In India, Cummins has operated a joint venture with the Tata Group for decades, supplying engines into the country’s commercial vehicle market.

Holding all of this together is the piece most people underestimate: service. Cummins’ network of more than 600 distributors and about 7,200 dealer locations supports the engines it sells no matter whose badge is on the hood. That does two things at once. It creates a recurring parts-and-service revenue stream that’s typically higher margin and less cyclical than new engine sales. And it builds customer habit. If you’re a fleet operator and you know you can get Cummins parts and support almost anywhere, specifying a Cummins engine on the next order becomes the low-risk choice.

But this model has a built-in tension: partnerships aren’t permanent. Any OEM can decide it wants more control and try to build its own competitive engine or powertrain system, turning from customer into competitor. So Cummins has to earn the relationship every cycle—by staying ahead on emissions compliance, by investing in electric and hydrogen alternatives, and by maintaining a support footprint that’s hard to justify from scratch. So far, for most OEMs, the math has favored buying from Cummins instead of rebuilding the entire capability stack in-house.

VIII. The Emissions Scandal & Recovery

Every great company story has its crisis chapter. Cummins’ arrived with an especially sharp twist: the company that had spent two decades making a business out of emissions compliance was accused of doing the opposite.

In early 2024, Cummins agreed to pay $1.675 billion to settle allegations that it violated the Clean Air Act. It was the largest civil penalty in the Act’s history, surpassing even Volkswagen’s headline-grabbing diesel settlement. The allegations centered on software and emissions-control strategies that regulators said functioned as defeat devices—tools that helped engines perform differently under testing than they did in everyday driving.

The government’s claims were specific. For model years 2013 through 2019, Cummins developed software for engines used in RAM 2500 and 3500 pickup trucks that, according to the allegations, enabled the vehicles to pass emissions testing while producing higher nitrogen oxides during normal operation. For model years 2019 through 2023, regulators said Cummins used additional undisclosed auxiliary emission control devices on roughly 330,000 more engines.

The settlement’s dollars didn’t stop at the headline number. Cummins owed $1.478 billion to the U.S. Treasury, $164 million to the California Air Resources Board, and $175 million to California’s environmental mitigation fund—plus the cost to recall and repair affected vehicles. In total, the hit was widely estimated at roughly $2 billion.

The chain of events traced back, ironically, to the scandal that made “defeat devices” a household term. After Volkswagen was exposed in September 2015, the EPA broadened its diesel testing across the industry. That wider scrutiny ultimately ensnared Cummins. The company said it had “seen no evidence that anyone acted in bad faith” and did not admit wrongdoing—common settlement posture, but not language that did much to quiet critics.

Reputationally, it hurt. But it didn’t break the company.

A few realities softened the blow. Cummins had already set aside significant reserves, which reduced the shock when the settlement became official. The engines at issue were tied to pickup applications—important, but not the core heavy-duty and industrial markets where Cummins’ name carries the most weight. And its OEM and fleet relationships were deep enough that customers didn’t stampede for the exits.

Even so, the episode exposed a governance and compliance failure that was hard to square with Cummins’ public posture as a sustainability-forward manufacturer. For a company investing billions into Accelera, hydrogen, and cleaner power systems, getting caught up in an emissions case wasn’t just expensive—it was contradictory. Leadership and compliance changes followed, along with the broader lesson that in a heavily regulated industry, the cost of trying to outsmart the rules almost always dwarfs the cost of following them.

For investors, the settlement looked like a brutal, largely one-time event rather than a permanent impairment to the business. Cummins reported 2024 net income of $3.9 billion, or $28.37 per diluted share, versus $735 million the prior year, which included settlement-related charges. The underlying question wasn’t whether Cummins could earn its way past the fine—it clearly could. It was whether the internal fixes would be strong enough to make sure the company never ended up here again.

IX. Business Model & Financial Analysis

Cummins runs a deliberately balanced machine. It reports five segments, and each one plays a different role in the broader “power ecosystem.” When you put them together, you start to see why Cummins can take hits in one market and keep moving.

In 2024, the Engine segment generated $11.7 billion in revenue, selling diesel and natural gas engines into trucks, buses, and a wide range of industrial equipment. Components delivered nearly the same, also at $11.7 billion, supplying the critical hardware that makes modern engines—and now electric powertrains—work: turbochargers through Holset, filtration and fuel systems, and, after the Meritor deal, axles and drivetrain components. Distribution brought in $11.4 billion by running Cummins’ parts and service network. Power Systems added $6.4 billion from generator sets, industrial engines, and the increasingly important business of backup power for data centers. And Accelera—the electrification platform—contributed $414 million.

The takeaway isn’t the exact dollars. It’s the shape of the company. No single segment completely owns the P&L. That’s not luck; it’s the result of decades of pushing beyond “we sell engines” into the components around them, the service that keeps them running, and adjacent markets like power generation. When truck demand slows, generators can carry more weight. When new engine builds soften, the installed base still needs parts, technicians, and uptime.

Financially, Cummins looks like what it is: a high-quality, capital-intensive industrial business. Gross margin runs around 25.6 percent—healthy for manufacturing, not software-company territory. Operating margin around 11.8 percent and profit margin around 8.2 percent reflect the reality of heavy engineering, factories, and supply chains. Where Cummins really separates itself is in capital efficiency: roughly 26 percent return on equity and about 13 percent return on invested capital suggest it’s historically been good at turning big, expensive assets into real earnings power.

That cash generation is what makes the shareholder story possible. Cummins supports an $8.00 annual dividend, around a 2.2 percent yield, and it has a long history of raising it—an important signal in a business that still lives with industrial cycles.

If there’s one part of Cummins that behaves less like a cyclical manufacturer and more like an annuity, it’s Distribution. This is the closest thing Cummins has to a subscription model. There are huge numbers of Cummins engines running worldwide, and every one of them eventually turns into a stream of maintenance, rebuilds, consumables, and the occasional high-stakes roadside or jobsite repair. Parts and service tend to be higher margin and less volatile than new equipment builds, which gives Cummins a steadier cash-flow foundation to fund R&D and acquisitions—even when engine cycles turn down.

That resilience showed up in 2024. Cummins posted record revenue of $34.1 billion even after divesting its Filtration business through the Atmus Filtration Technologies spinoff. In other words, the rest of the portfolio—especially Power Systems and Distribution—grew fast enough to more than fill the gap. In North America, Power Systems revenue jumped 42 percent, largely on demand for data center backup power. That’s not just a one-year blip. As cloud computing, AI workloads, and digital infrastructure scale, the need for reliable standby power scales with them—and Cummins is one of the standard names buyers turn to.

For 2025, management guided to revenue ranging from down 2 percent to up 3 percent, with EBITDA margins of 16.2 to 17.2 percent. That spread tells you what management is balancing: continued uncertainty in the heavy-duty truck cycle—especially expectations for further declines in North American on-highway engine shipments—against sustained strength in power generation and service. The next key checkpoint is Q4 2025 results, expected on February 5, 2026.

If you only track a few metrics to understand where the story is going, focus on two. First, Power Systems revenue growth and backlog, because it’s the cleanest read on whether the data center tailwind is still strengthening. Second, Accelera’s losses relative to companywide EBITDA, because that’s the practical scoreboard for the transition: is the electrification bet becoming more efficient as it scales, or getting more expensive before it gets better?

X. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

Cummins’ century-plus run isn’t just an engine story. It’s a blueprint for how to build an industrial company that lasts—and how to invest in one.

First: patient capital buys you time to do real engineering. The Irwin family funded Clessie Cummins through years of losses before the business found commercial traction. In a world that often demands fast proof and tidy timelines, Cummins is a reminder that some categories—hard tech, manufacturing, regulated infrastructure—don’t move at app speed. Patience doesn’t guarantee success. But without it, some successes never get the chance to exist.

Second: distribution and service are a moat you can’t simply reverse-engineer. Cummins’ roughly 7,200 dealer locations didn’t appear because someone drew a map. They were built over decades, one relationship and one service bay at a time. A competitor can copy features, even performance. What’s far harder to copy is the ability to keep a customer running everywhere, all the time. In heavy-duty equipment, uptime is the product—and service is how you deliver it.

Third: the ability to cannibalize yourself is less about a single strategic plan and more about culture. Cummins leaned into natural gas engines while diesel was still growing, and into electrification while diesel was still throwing off serious profits. That’s uncomfortable. It means funding businesses that look worse than the core business for a long time. But it’s also how you avoid waking up one day to find the future has already been won by someone else.

Fourth: the best M&A doesn’t buy revenue—it buys capability. Holset brought turbocharging. Onan brought power generation. Meritor brought drivetrain and electric powertrain depth. First Mode brought a pragmatic angle on decarbonizing mining fleets. In each case, Cummins wasn’t collecting logos. It was filling a technical gap fast enough to matter. The alternative—building everything from scratch—might have been slower, riskier, and ultimately more expensive.

Fifth: independence can be a structural advantage, especially in fragmented markets. By supplying multiple OEMs, Cummins gets scale that a single manufacturer’s captive engine program can’t match. That scale funds more R&D, which produces better products, which attracts more customers. It’s a flywheel that’s hard to start, but powerful once it’s spinning.

Finally: regulation isn’t just a cost—it can be a weapon. Each tightening emissions cycle rewarded the companies that could keep up, and Cummins often used its compliance investments to widen the gap versus smaller players and under-resourced in-house programs. That’s what made the emissions scandal so damaging: it undercut the very credibility Cummins had used as an advantage. Winning it back isn’t a press release. It’s years of process, proof, and trust rebuilt the hard way.

XI. Analysis & Bear vs. Bull Case

The Bull Case

Cummins’ bull case is basically the argument that the company has the rare combination of scale, execution, and optionality. Revenue has been growing around 12.6 percent annually, and return on equity has been north of 24 percent—signals that, despite being a century-old industrial, Cummins has still been compounding like a business with real momentum.

The cleanest near-term tailwind is Power Systems. Data centers don’t just need electricity; they need certainty. As hyperscalers and AI-heavy workloads drive more buildouts, the demand for backup generation can stay elevated for years, and Cummins sits right in the middle of that spend.

Then there’s the long game: electrification. Yes, it’s expensive right now. But if commercial vehicles electrify in a meaningful way—even on a slower, more uneven timeline than passenger cars—Cummins has placed the right kinds of bets: batteries, eAxles, hydrogen, and hybrid systems. And it hasn’t done it alone. The Amplify Cell Technologies joint venture with PACCAR and Daimler is a strong validation point. Those OEMs don’t partner lightly, and their involvement suggests Cummins is viewed as a credible supplier for the next powertrain era, not just the last one.

And underneath all of this is the moat that keeps showing up in every era of Cummins’ story: the distribution and service network. It’s hard to overstate how sticky this is. Fleets don’t just buy an engine; they buy the ability to keep that engine running across routes, seasons, and geographies. In Hamilton Helmer’s “7 Powers,” it looks like a “cornered resource” (the network itself) and “switching costs” (it’s painful to retrain techs, change parts ecosystems, and rebuild service habits). In Porter’s terms, it raises barriers to entry and makes it harder for OEMs to simply swap Cummins out without taking on real operational risk.

The Bear Case

The bear case starts with one uncomfortable truth: Cummins’ cash cow is still diesel. Over time, diesel’s share of the commercial vehicle market is likely to shrink as regulations tighten and alternatives get better. The key variable is speed. A slow fade over a couple of decades is manageable, and maybe even ideal—it gives Cummins time to transition while the legacy business funds the build. A faster shift could hit margins, leave manufacturing assets underutilized, and force a more chaotic handoff than “Destination Zero” implies.

The second risk is China and geopolitics. Cummins has meaningful exposure through joint ventures. But China is a market where industrial policy can turn into competitive policy, and where tensions around trade, technology transfer, and local sourcing can change the economics quickly. If domestic suppliers gain preference—or foreign players face restrictions—Cummins’ China engine could sputter.

The third risk is execution across too many paths at once. Cummins is simultaneously pushing battery electric, hydrogen combustion, hydrogen fuel cells, and hybrid approaches. That’s strategically rational in a world where end markets won’t transition in sync—but it’s also capital intensive, and it increases the odds of spending heavily on the wrong answer for certain applications. The electrolyzer strategic review and Accelera’s $431 million EBITDA loss in 2024 make the point plainly: this transition is real, and it’s costly.

Competition adds another layer of pressure. Caterpillar is a formidable rival in power generation and industrial engines. OEMs like PACCAR and Volvo have their own engine programs and are investing in electrification themselves. Chinese manufacturers are improving quickly in both diesel and electric drivetrains. And in specific niches, pure-play EV and powertrain startups can move faster than an incumbent.

Finally, there’s valuation. Cummins trades around 17.7 times trailing earnings and about 17.5 times forward earnings—roughly what you’d expect for a mature, high-quality industrial with modest growth baked in. Bulls will say that looks cheap if the data center demand wave persists and Accelera scales into real profitability. Bears will say it can look expensive if diesel erodes faster than expected or if the transition bets don’t translate into durable returns.

XII. Epilogue & "If We Were CEOs"

The defining challenge for whoever leads Cummins through the next decade is managing the clock. Diesel isn’t disappearing tomorrow—global commercial fleets will keep running on internal combustion for years, and in many developing markets, likely for decades. But the direction is unmistakable. Diesel’s peak share is in the rearview mirror. The job now is to harvest the legacy business at maximum value while building what comes next—and to sequence that handoff so the old funds the new without starving either one.

Geographically, the next innings are still wide open. India, Africa, and Southeast Asia are massive growth markets for mobility and infrastructure, and they’ll need every kind of power solution: conventional engines, cleaner combustion, hybrid systems, and eventually zero-emissions options where infrastructure allows. Cummins already knows how to expand this way. The joint venture playbook—learn the market with a local partner, manufacture locally, support relentlessly—worked in China. And the distribution footprint remains a real edge, because selling power is only half the deal; keeping it running is the other half.

The hardest decisions, though, are technological. Battery-electric and hydrogen both have real use cases, but neither is a universal replacement for diesel in heavy-duty work today. Hydrogen needs fueling infrastructure that still isn’t there at scale. Battery-electric needs charging, and it comes with range, weight, and duty-cycle constraints that become unforgiving in long-haul and heavy industrial settings. Cummins’ “all of the above” approach—hydrogen, batteries, hybrids, and cleaner diesel—makes strategic sense in a messy transition. It’s also expensive, and it demands brutal capital allocation discipline. The difference between a portfolio of options and a pile of distractions is focus, timing, and the willingness to double down only when the path is real.

If we were sitting in the CEO chair, that’s where we’d obsess: protect the diesel cash engine, keep winning on uptime and service, and make sure Accelera’s losses are buying learning and scale—not just buying time. Because in the end, the most valuable asset Cummins brings to this moment may not be a particular technology at all. It’s culture. This is a company that has reinvented itself repeatedly—from marine diesels to trucking dominance, from engines to components, from components to full power systems. That institutional muscle memory, rooted in the original Irwin-and-Clessie partnership, is what gives Cummins a credible shot at doing it one more time.

XIII. Recent News

Cummins recently touched an all-time high stock price of $587.66, capping a run of roughly 62 percent over the past year. The market’s read has been pretty clear: Cummins is executing, and two parts of the portfolio are doing the heavy lifting—Power Systems and Distribution—helped along by the surge in demand for data center backup power.

In Q3 2025, reported in November, Cummins beat expectations. Adjusted earnings came in at $5.59 per share versus analyst estimates of $4.73. Power Systems sales climbed 18 percent to $2 billion, and Distribution grew 7 percent to $3.2 billion. The soft spot, again, was on-highway. Demand continued to weaken, and shipments to truck customers were expected to fall another 15 percent in Q4.

On the product side, Cummins began limited production of its new F4.5 Structural engine for tractors. It also picked up an industry nod when the X15 Off-Highway engine won Powertrain Magazine’s 2026 Alternative Engine of the Year Award. And in a fun callback to the company’s showman roots, Cummins announced a full-season NASCAR sponsorship—returning to motorsports with Brenden “Butterbean” Queen’s No. 12 Cummins Ram 1500.

Accelera by Cummins delivered its largest electrolyzer system yet: a 35-megawatt PEM unit for Linde’s hydrogen facility in Niagara Falls. That milestone came even as the electrolyzer business continued to face broader headwinds. Meanwhile, the Department of Energy’s $75 million manufacturing grant—matched by Cummins—is supporting expanded battery pack and powertrain production capacity.

Looking ahead, Q4 2025 earnings are expected on February 5, 2026. Analyst consensus calls for about $5.36 per share in earnings on $8.15 billion in revenue. For the full year 2025, adjusted earnings are projected around $23.12 per share, with fiscal 2026 estimates rising to roughly $26 per share—about 12.6 percent year-over-year growth.

XIV. Links & Resources

- Cummins Investor Relations — SEC filings, earnings releases, and annual reports

- Cummins Newsroom — Press releases and company announcements

- EPA Cummins Emissions Settlement — The EPA’s full settlement page and case details

- Accelera by Cummins — Cummins’ zero-emissions business unit

- Cummins 2024 Annual Results — Full-year results and financial breakdown

- Cummins-First Mode Acquisition — Details on the mining retrofit acquisition

- Cummins-Meritor Integration — Meritor acquisition and integration overview

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music