Columbus McKinnon: Lifting the World, One Hoist at a Time

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture this: somewhere in Manhattan, the lights dim on a Broadway stage. Unseen motors hum overhead, lifting a multi-ton set piece with near-perfect precision while the audience holds its breath. At the same time, in a Tesla Gigafactory across the country, conveyors and automation gear move battery modules through production lines built to run around the clock. And in a German petrochemical plant, an explosion-protected hoist lifts critical equipment in a place where a single spark can be a disaster.

What do these scenes have in common? Columbus McKinnon.

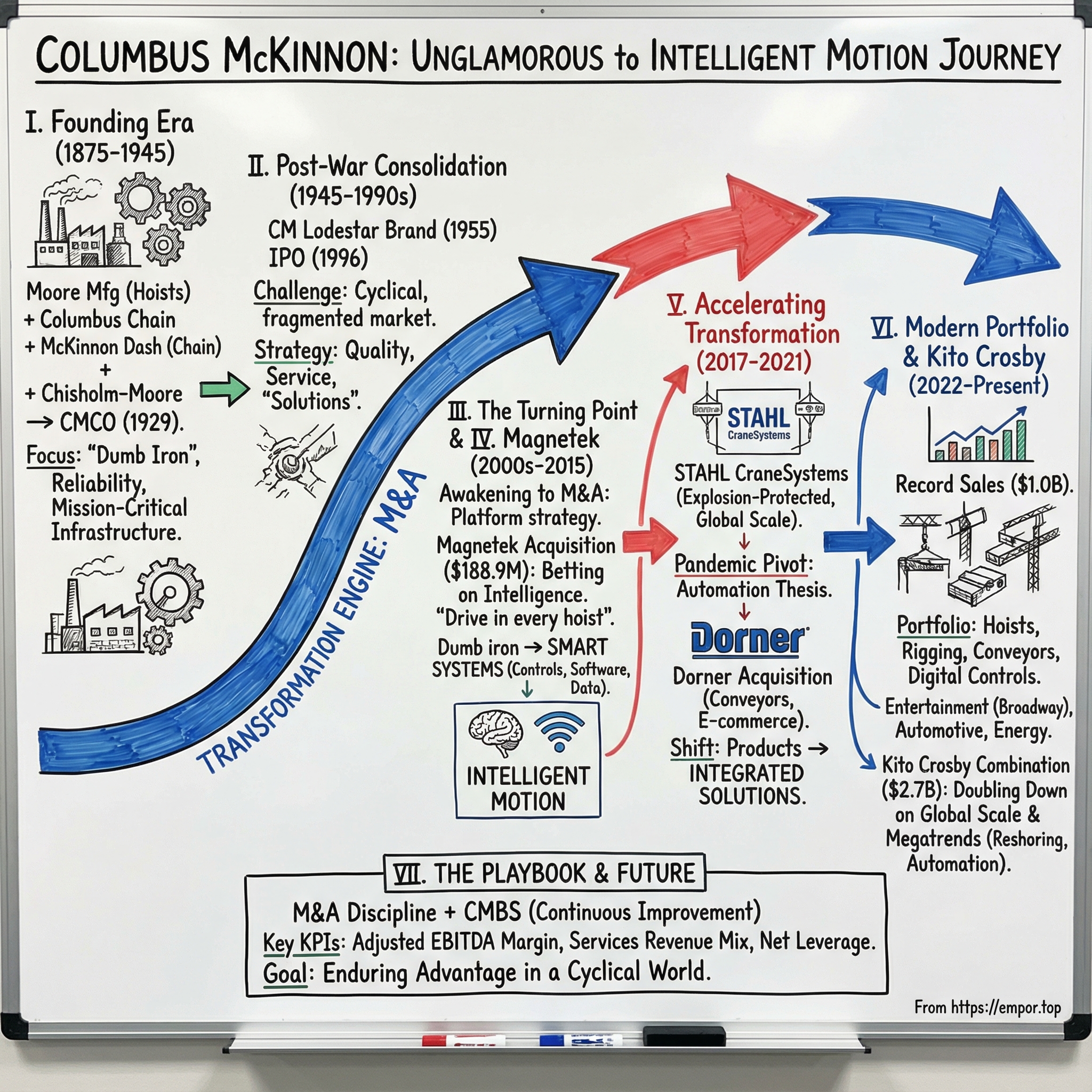

This is a company with more than 145 years of history that, in the last decade, has pushed well beyond “just hoists” and into intelligent motion solutions—equipment, controls, and increasingly the systems that tie them together. Along the way, it assembled a portfolio of high-quality brands—CM, STAHL CraneSystems, Yale, Magnetek, Coffing Hoists, Dorner, and Duff-Norton—each bringing a piece of the modern motion-control stack.

And the scale of what they’ve built is no longer small. Columbus McKinnon reached record net sales of $1.0 billion in fiscal 2024, with growth across geographies. Then, in early 2025, it announced its boldest move yet: a definitive agreement to acquire Kito Crosby Limited from KKR in an all-cash transaction valued at $2.7 billion—a deal that would more than double the company’s size.

So the central question here isn’t really about hoists and cranes. It’s the question underneath them: how does a legacy industrial company reinvent itself in the age of automation? How does management allocate capital when end markets are cyclical and competitors are everywhere? And can a business born in the Industrial Revolution build competitive advantages that still matter in the twenty-first century?

Yes, Columbus McKinnon helps put on the show—literally. From Broadway musicals to touring productions and international events, organizers rely on CM-Entertainment products to make sure the rigging works and the curtain actually goes up. But entertainment is just one corner of the map. CMCO sells into automotive and aerospace, food processing, energy, and e-commerce distribution centers—industrial infrastructure that keeps the physical economy moving. Unsexy, essential, and once you see the whole picture, surprisingly fascinating.

The themes we’ll unpack are bigger than any one company: using M&A as a transformation engine, moving from products to solutions, surviving brutal cyclicality, and managing the constant tension between legacy cash cows and the next wave of technology. Let’s lift the curtain on Columbus McKinnon.

II. Founding Era & The Birth of American Industry (1875–1945)

The story starts in the 1870s, in the middle of America’s industrial takeoff. The country was rebuilding after the Civil War. Railroads were stitching the continent together. Factories were popping up across the Northeast and Midwest. And every one of those factories had the same physical problem: you had to move heavy things. Doing it by hand was slow, dangerous, and expensive—so the companies that could make lifting safer and more efficient became the quiet enablers of everything else.

One of Columbus McKinnon’s roots on the “hoist” side traces back to 1875, with the founding of Moore Manufacturing Company in Chicago. Moore initially focused on the railroad industry—especially sliding doors and door hangers for freight cars. But over time, the center of gravity shifted. By 1889, the business—then known as Moore Manufacturing and Foundry Company, headquartered in Milwaukee—was increasingly focused on hoists, trolleys, and cranes.

Meanwhile, the “chain” side of the future company was forming on a parallel track. Around the turn of the twentieth century, the Columbus Chain Company in Columbus, Ohio, emerged as one of the earliest American suppliers of fire welded chain. It had been founded by employees from the Hayden Iron Company, a firm that had been producing harness hardware since 1825 and also manufactured coil chain. In other words: deep, practical metalworking know-how, repurposed for the needs of a mechanizing economy.

And then there’s the McKinnon name itself—coming from Canadian-born Lachlan Ebenezer McKinnon. His career is basically a Gilded Age origin story. He started as a hardware clerk, then in 1878 became a partner in an Ontario business called McKinnon and Mitchell Hardware. The shop focused on saddle and wagon hardware, and in the back there was a small, four-man workshop producing wagon gears and a patented adjustable dash. In 1887, McKinnon created a Buffalo subsidiary, the McKinnon Dash Company, and kept branching outward into metal products—everything from suspender buckles to bicycles and, crucially, chains.

What’s notable isn’t just the hustle—it’s the manufacturing mindset. McKinnon brought an emphasis on innovative production methods, including an electric welding process for chain manufacturing. That edge mattered. And in 1917, the merger of Columbus Chain Company and McKinnon Chain Company became a key step: consolidating ownership and sharpening operational focus around chain as an industrial product category, not just a sideline.

The final piece was the hoist business that would make Columbus McKinnon feel like a complete system. In 1899, S.H. Chisholm became president of what was then renamed the Chisholm and Moore Manufacturing Company. Over the next three decades, Chisholm Moore developed high-speed hoists and hand chain hoists, and by the 1920s the product line expanded into electric wire rope hoists and electric cranes. In 1928, Chisholm Moore was acquired by the Columbus McKinnon Chain Company—bringing hoists and chain under one roof.

A year later, in 1929, the company was incorporated as Columbus McKinnon Corporation. It was, strategically, a clean combination: two complementary product lines—chains and hoists—that reinforced each other and could be sold into the same industrial customers. The timing, however, couldn’t have been worse. The Great Depression was only months away. But the logic of the business—owning essential infrastructure products—was sound enough to endure.

This founding era also locked in the company’s DNA: an engineering-first culture, an obsession with reliability, and a focus on equipment that would never be glamorous but would always be necessary. Columbus McKinnon was in the “picks and shovels” business of industrialization—the hardware that made other industries run.

And then the world went to war—twice. Through World War I and World War II, the company became mission-critical infrastructure. Military demand drove expansion, but the bigger impact was cultural: when equipment failure can cost lives, quality stops being a marketing line and becomes a discipline. Those years hardened the company’s relationship with tolerances, testing, and durability—and set expectations that would carry forward for generations.

III. Post-War Consolidation & The CM Brand (1945–1990s)

After World War II, American manufacturing didn’t just recover—it roared. Factories ran hot, domestic demand kept climbing, and the U.S. sat at the center of global production. For industrial equipment makers, this was the golden age. Columbus McKinnon rode that wave, scaling the products and the distribution footprint that would define it for decades.

Some of the company’s most important advantages weren’t flashy; they were foundational. Long before “industrial safety” became a buzzword, this industry was being shaped by hard engineering breakthroughs—like the Weston differential hoist and Yale’s early hand chain hoist with a load pressure brake. These were the kinds of innovations that quietly became standards, because they solved the only problems that mattered: control, reliability, and keeping people alive on the job.

Coming out of the war years, CMCO expanded in a way that looks obvious in hindsight but took real operational discipline at the time. It broadened its lineup across manual and electric hoists, cranes, rigging equipment, and industrial chain. Each product category had its own quirks—different buyers, different routes to market, different competitors—but they were all built on the same core strengths: metalworking know-how, manufacturing capability, and relationships in the industrial distribution ecosystem.

And then there’s the brand. In this world, brand doesn’t mean advertising. It means what foremen say about you when something goes wrong. Starting in 1955, the CM Lodestar electric hoist earned a reputation for consistent performance and long life. That reputation mattered because the stakes were brutal: a hoist that slips or drops a load isn’t just a warranty claim. It’s an injury. It’s a lawsuit. It’s a customer who never comes back. Reliability wasn’t a feature—it was the product.

In 1996, Columbus McKinnon went public. With the IPO, the Amherst, New York-based company moved from being a strong regional industrial manufacturer into a publicly traded platform with access to capital—and a new mandate to grow. Management leaned into acquisitions, using the public markets to fund a more aggressive expansion strategy.

But through the automotive booms, the construction cycles, and the broader manufacturing churn of the late twentieth century, CMCO’s core challenge didn’t change. This was a mature business in a cyclical, fragmented market. There were hundreds of regional players, plenty of look-alike products, and constant price pressure on the most standard equipment. You could run a good business here—just not an easy growth story.

So the company did what high-quality industrial businesses do. It focused on quality and service, worked through distributors and crane builders who cared about uptime more than unit price, and tried to sell “solutions” instead of just equipment. That kept CMCO steady. But it didn’t fix the underlying math: organic growth in this kind of market is slow, grinding, and vulnerable to the cycle.

What started to become clear, though, was that the industry’s structure contained its own escape hatch. Fragmentation meant there were always potential targets. Trusted brands and entrenched distribution relationships created real switching costs. And customers were getting more sophisticated—more willing to pay for complete systems, not just parts.

In other words, the groundwork was being set for Columbus McKinnon’s next era: a company that would treat M&A not as a once-in-a-while event, but as a core capability—and eventually, as the engine of transformation.

IV. The Turning Point: Awakening to M&A (2000s–2014)

By the early 2000s, Columbus McKinnon ran into the hard limits of its old playbook. Organic growth was sluggish. Low-cost Chinese manufacturers were pushing into the market. The most standard hoists and chain were getting treated like commodities, and commodity pricing does what it always does: it squeezes margins. On top of that, CMCO’s largely regional footprint left it exposed to larger competitors with more scale.

That pressure forced a round of strategic soul-searching—and it produced a deceptively simple conclusion. CMCO couldn’t win by just building a slightly better hoist. It needed to become the platform others had to plug into.

The industry structure made that idea feel less like a leap and more like an obvious move hiding in plain sight. This was a market full of small manufacturers in adjacent niches. Many didn’t have the resources to invest meaningfully in R&D. Distribution was fragmented. And a lot of the sector was still family-owned, with founders nearing retirement—meaning there was a steady, natural pipeline of potential sellers.

So management started small and started learning. The goal wasn’t to swing for the fences immediately. It was to build the muscle: how to find targets, evaluate them, integrate them, and actually get better at it each time. In 2008, CMCO acquired Pfaff-silberblau Hebezeugfabrik GmbH in Kissing, Germany—an early step toward a real European presence.

What made this period important wasn’t deal size. It was intent. These weren’t acquisitions for the sake of adding revenue. CMCO increasingly looked at each deal as a way to add something specific: a complementary product line, a new route to market, a broader distribution footprint, or a capability the company didn’t already have.

The finance philosophy matched the strategy. Use leverage, but don’t get trapped by it. Keep enough headroom to do the next deal. Stay focused on improving returns on invested capital, not just reporting higher sales. Pay reasonable prices, then move quickly to capture synergies.

Alongside the deal-making, CMCO kept widening its map. It established Columbus McKinnon Russia LLC in St. Petersburg in 2010, renamed Yale Industrial Products GmbH to Columbus McKinnon Industrial Products GmbH in 2011, and founded operations in Turkey and Dubai in 2012.

All of this mattered. But it still wasn’t the transformation. It was the runway. To truly change the company’s trajectory, CMCO needed a much bigger move—one that would shift it up the value chain. And that deal was coming.

V. The Magnetek Acquisition: Betting on Intelligence (2014–2015)

In the summer of 2015, Columbus McKinnon made its biggest bet yet: it acquired Magnetek for $188.9 million. On paper, it was a straightforward deal—CMCO called it “an excellent strategic and cultural fit between two market-leaders,” and positioned it as a step toward its long-term ambition of reaching $1 billion in revenue.

But the real significance wasn’t the price tag. It was what Magnetek allowed CMCO to become.

Magnetek, based in Wisconsin, sat in a different layer of the stack. It was known as North America’s largest independent supplier of digital drives, radio controls, software, and accessories used in industrial cranes and hoists. It was also the largest independent supplier of digital DC motion control systems for elevators. In other words: this wasn’t more “iron.” This was the intelligence that makes the iron safer, smoother, and more productive.

The strategic logic was clean: move up the value chain from “dumb iron” to “smart systems.” A basic hoist is motors, gears, and metal—important, but increasingly subject to price pressure. Add integrated radio controls, variable frequency drives, and diagnostic software, and the conversation changes. Now you’re selling precision, uptime, safety, and features customers don’t want to rip out once they’ve built them into their operations. The margins improve. The stickiness improves. The switching costs go way up.

The two companies were already converging on the same direction—smart hoist technology—and management expected at least $5 million in cost synergies in the first full year after closing. But the bigger prize was growth: using Columbus McKinnon’s distribution footprint to push Magnetek’s control technology into more markets, in more geographies, through more channels.

Timothy Tevens, then President and CEO, summed it up: “We believe Magnetek's technology will enable the industrial world to continue to advance productivity and safety beyond what mechanical solutions alone can offer. We see many opportunities for revenue synergies by advancing Magnetek's power control technology globally through our multiple sales channels and introducing it into key vertical markets.”

There was also a quiet detail that made the bet feel less risky: Magnetek already counted Columbus McKinnon as a customer. CMCO wasn’t buying a mystery box—it was buying a capability it had been validating in the real world.

CMCO paid $50 per share in cash, for an aggregate purchase price of approximately $188.9 million, and expected the acquisition to add about $0.40 per share of earnings in the first full fiscal year of combined operations. Just as importantly, it didn’t try to “fix” Magnetek by folding it into the parent. Magnetek’s brand and operations stayed intact, and its CEO, Peter McCormick, continued to run the business.

What CMCO really acquired wasn’t just a product line. It was a set of muscles it didn’t have before: electronics engineering, software development, wireless controls, and the early building blocks of predictive maintenance. These were exactly the capabilities needed in an industrial economy moving toward connectivity, data, and automation.

After Magnetek, Columbus McKinnon wasn’t just a lifting company. It was becoming a motion control company—and the ceiling on what it could be got a lot higher.

VI. The Transformation Accelerates: 2015–2019

After Magnetek, Columbus McKinnon didn’t just keep acquiring—it started building a new kind of company around that acquisition. The shift became unmistakable in early 2017, when the board appointed Mark D. Morelli as President and Chief Executive Officer, completing a planned leadership succession. Morelli also joined the Board of Directors.

Morelli’s résumé fit the moment. He had most recently been President and Chief Operating Officer of Brooks Automation from 2012 to 2016, a business that lived at the intersection of industrial hardware and high-tech execution. Before that, he served as CEO of Energy Conversion Devices, and earlier spent more than a decade at United Technologies, moving through product management, marketing, strategy, and increasingly large general management roles—ending as President of Carrier Commercial Refrigeration. Even his first chapter read like a leadership case study: he began his career as a U.S. Army officer and helicopter pilot, commanding an attack helicopter unit. He held a mechanical engineering degree from Georgia Tech and a management master’s from MIT Sloan.

When Morelli took the role, he didn’t talk like a caretaker. He talked like someone arriving to press the accelerator. “Columbus McKinnon is an industry leader with excellent brands, strong customer relationships and a long, well-established history,” he said. “This is an exciting time to join the Company given its expanded market reach and new products gained both through acquisitions and the launch of the ‘drive in every hoist’ program.”

That last phrase—“drive in every hoist”—was the tell. This wasn’t about adding a nice-to-have option to the catalog. It was the company putting a stake in the ground: the future wasn’t just stronger steel and better gears. It was intelligence everywhere. Drives, controls, data, and the ability to monitor performance, optimize operation, and anticipate maintenance before something breaks. The hoist stops being a standalone product and starts behaving like a node in a system.

At the same time, the old era was closing. Timothy T. Tevens, who had joined the company in 1991 and served as President and CEO since 1998, retired. The board framed the handoff as a strategic one: Morelli’s experience across global technology and industrial markets—and his track record building high-performance organizations with faster growth and better margins—matched where CMCO wanted to go next.

And where it wanted to go next required momentum. The acquisition pace picked up, guided by a simple playbook: buy niche leaders with capabilities CMCO didn’t have, integrate with speed and discipline, capture synergies, and then use the company’s growing global distribution footprint to expand revenue.

Then came the deal that would test whether Columbus McKinnon could truly play on the global stage: STAHL CraneSystems.

VII. STAHL Deep Dive: The Game-Changer (2017)

Columbus McKinnon’s next move wasn’t just bigger. It was different.

The company acquired STAHL CraneSystems—STAHL CraneSystems GmbH plus nine affiliated companies—in an all-cash deal for €224 million (about $240 million), net of the cash and debt it took on, buying the business from Konecranes.

This deal deserves its own chapter because it changed Columbus McKinnon’s identity. Before STAHL, CMCO was still, at its core, a North American company with some European operations. After STAHL, it had a real second center of gravity: a commanding European platform and a credible claim to being global.

The opening came from a classic piece of industrial dealmaking: regulators. Konecranes was in the middle of an EU antitrust review tied to its pending acquisition of Terex’s Material Handling & Port Solutions business. To get that deal approved, it had to divest assets—and STAHL was one of them. When forced sales happen, great businesses can suddenly become available. CMCO was ready to move.

STAHL’s appeal wasn’t complicated: it made the kinds of hoists and crane components that are hard to replicate, and it had a reputation built over generations. The company manufactured explosion-protected hoists and crane components, and it was known for custom-engineered lifting solutions. Its customers included independent crane builders and engineering, procurement, and construction firms, and it served a wide spread of end markets: automotive, general manufacturing, oil and gas, steel and concrete, power generation, and process industries like chemical and pharmaceuticals.

STAHL itself had the kind of backstory that signals durability. Founded in 1876 by Rafael Stahl and Gustav Weineck in Stuttgart, it grew into a high-quality German hoist and crane technology manufacturer—140 years of accumulated trust, process discipline, and engineering heritage that you don’t “build” with a marketing budget.

The strategic fit was obvious to CMCO leadership. As CEO Timothy Tevens put it, “We have long viewed STAHL as an ideal complement to Columbus McKinnon EMEA, as well as an excellent expansion of our global product offering. Their strong position with wire rope and electric chain hoists in Europe immediately complements our leadership of handheld hoists in that region, and their broad portfolio of ATEX certified explosion-protected products serving the mining, oil & gas and chemical processing industries significantly extends our global offerings in capability and capacities.”

STAHL came with real scale. It had about 650 employees across manufacturing in Germany and nine sales affiliates around the world. For the trailing twelve months ended September 30, 2016, STAHL generated roughly €155 million (about $166 million) in revenue. And importantly, the geographic mix was the mirror image of Columbus McKinnon’s: about 71% EMEA, 16% Americas, and 13% Asia Pacific—almost perfectly complementary to CMCO’s North America-heavy footprint.

But the crown jewel was capability, not geography: explosion protection.

In this world, “explosion-protected” isn’t a spec on a datasheet. It’s a permission slip to operate in the harshest, most regulated environments on earth. STAHL’s brand stood for safe, reliable hoists and crane components, backed by methodical engineering and one of the most extensive product portfolios in explosion-protected crane technology.

And that capability came with a real barrier to entry. ATEX certification for equipment used in explosive atmospheres demands extensive engineering work, testing, and documentation. Once equipment is qualified, switching suppliers can mean expensive requalification and time-consuming compliance work—exactly the kind of friction that locks customers in and turns “products” into long-lived relationships.

CMCO told investors to expect the deal to be meaningfully accretive—forecasting earnings accretion of $0.34 per share in fiscal 2018 and $0.51 per share in fiscal 2019, driven by cost synergies. To finance the acquisition, the company completed a $50 million common stock sale and used debt financing. It put in place a $445 million first-lien term loan priced at LIBOR plus 3.0%, along with a $100 million revolving credit facility.

For Columbus McKinnon, that was significant leverage—less a financial flourish than a signal of conviction. Management believed STAHL’s brand, quality reputation, and customer relationships were worth leaning into. And paired with Magnetek, the message to customers was becoming clearer: CMCO could offer not just lifting equipment, but broader, higher-value systems.

Still, this was a bet that couldn’t be won on a slide deck. Integrating STAHL meant blending American deal-driven urgency with German engineering precision. It meant proving CMCO could operate through European channels as naturally as it did through North American distribution. Early signs were encouraging, but the full integration—and the full payoff—would take years.

VIII. Pandemic Pivot & The Automation Thesis (2020–2021)

When COVID-19 slammed the brakes on the global economy in early 2020, Columbus McKinnon got hit by the same fog of uncertainty as every industrial manufacturer. Supply chains fractured. Customer facilities went dark. Capital spending paused. For a company that sells into factories and job sites, it was the kind of shock that can expose every weakness at once.

But the pandemic didn’t just disrupt demand—it rewired it. Almost overnight, the world started asking for more automation, not less. If you couldn’t pack a plant with people, you needed equipment that could keep production moving with fewer hands on the floor.

Right in the middle of that turbulence, CMCO made a leadership change. In May 2020, Columbus McKinnon announced that its board had appointed David J. Wilson as President and Chief Executive Officer, effective June 1, 2020.

Richard Fleming, Chairman and Interim CEO, explained the choice plainly: “After a thorough and extensive search, he became our candidate of choice because of his proven success with operational excellence and customer-centric commercial growth. Further, he brings to Columbus McKinnon superior international and business development skills and a demonstrated track record for delivering results.”

Wilson’s background matched the moment. Over nearly two decades at SPX Corporation and its spin-off SPX FLOW, he rose into senior leadership roles where the job was less “keep the trains running” and more “rebuild the track while the train is moving.” He led growth initiatives, simplified and restructured operations, managed acquisitions and portfolios, and set strategy across multiple businesses. He also ran global operations and spent years living in Asia and Europe—experience that mattered for a company that had just made itself meaningfully international.

Wilson signaled that the company intended to keep moving forward, not just hunker down. “While we are currently in unprecedented times with the pandemic,” he said, “the team has acted quickly to adjust its operations to the current market environment while also pursuing select strategic initiatives that will advance its Blueprint for Growth strategy. I look forward to the opportunity to help us navigate through this period while we also build a sustainable growth platform that focuses on market segmentation, innovative product development and acquisitions.”

That last word—acquisitions—wasn’t incidental. Because as the pandemic unfolded, it became clear that the push toward automation wasn’t a temporary workaround. Labor shortages, distancing requirements, and the need for supply chain resilience were forcing manufacturers and distributors to invest in systems that could run with less human intervention. Meanwhile e-commerce surged, and every online order translated into physical reality: packages moving through distribution centers built on conveyors, hoists, and material handling infrastructure.

CMCO responded with one of the most consequential deals in its transformation. The company acquired Dorner Manufacturing Corporation for an all-cash purchase price of $485 million, on a cash-free, debt-free basis, and expected about $5 million of annual cost synergies by the end of fiscal year 2023.

Dorner gave Columbus McKinnon something it didn’t have: a true platform in specialty conveying. Dorner was a market leader in the global specialty conveyor market, with end markets benefiting from the same secular tailwinds CMCO was betting on—automation and the acceleration of e-commerce adoption across both consumer and industrial markets.

Founded in 1966 in Hartland, Wisconsin, Dorner built its reputation on high-precision specialty conveyor systems designed to improve productivity, quality, reliability, speed, and uptime. It offered both modular standard products and highly engineered custom solutions—exactly the kind of mix that tends to create stickier customer relationships and deeper integration into operations.

And Dorner was growing. Its revenue increased from $70 million in fiscal 2016 to an expected $125 million in the current fiscal year, and EBITDA grew from $15 million to an expected $31 million.

Wilson framed the acquisition as a strategic leap, not a bolt-on. He noted that Dorner significantly advanced CMCO’s growth objectives by establishing a new platform in specialty conveying—while also expanding the company’s scale as a provider of intelligent motion solutions for material handling.

And this is where the narrative snaps into focus: Dorner wasn’t just “more products.” It expanded the definition of what Columbus McKinnon could deliver. Hoists move loads up and down. Conveyors move them across. Put the two together, and you’re no longer selling components—you’re increasingly capable of selling complete, floor-to-ceiling motion solutions.

IX. The Modern Portfolio & Go-To-Market (2022–Present)

By fiscal 2024, which ended March 31, 2024, Columbus McKinnon hit a milestone it had been chasing for years: record net sales of $1.0 billion, up 8%, helped by growth across every geography and the acquisition of montratec.

Profitability moved in the right direction, too. Gross margin rose to 37.0%, and adjusted gross margin reached 37.3%. Net income was $46.6 million. Adjusted EBITDA climbed to $166.7 million—up 13%—with an adjusted EBITDA margin of 16.4%.

But the bigger story isn’t the one-year snapshot. It’s what the portfolio has become.

Today, Columbus McKinnon is a worldwide designer, manufacturer, and marketer of intelligent motion solutions—products and systems that move, lift, position, and secure materials safely and ergonomically. That spans hoists and crane components, precision conveyor systems, rigging tools, light rail workstations, and digital power and motion control systems. The common thread is the same one that’s been in CMCO’s DNA since the beginning: in commercial and industrial environments, safety and quality aren’t optional, and the engineering has to hold up in the real world.

You can see the company’s “hidden moats” especially clearly in entertainment. Columbus McKinnon Entertainment Technology, or CM-ET, is a leader in lifting and positioning equipment for riggers globally. Its electric chain motors, ratchet hoists, chain, and rigging products show up in venues around the world. And the CM Lodestar electric hoist—introduced in 1955—has earned the kind of trust you can’t buy: generations of users relying on it for consistent operation and long life. When you’re hanging loads over people, reputation is the brand.

CMCO didn’t stumble into that market; it earned it. Starting in 1981, the company reengineered its flagship industrial hoist, the CM Lodestar, to meet the unique requirements of entertainment applications. Since then, it has stayed close to the work—developing products and training designed not just to help riggers work safely, but to protect performers and audiences, too. And wherever the show is, CMCO’s global entertainment distributor network is there with parts, service, and accessories.

Zoom out, and entertainment is just one vivid example of the broader positioning. Whether its products are lifting a 47-ton airplane wing, positioning a subassembly at a workstation, or securing a lighting grid for a Broadway musical, customers rely on Columbus McKinnon’s application expertise as much as the equipment itself. CMCO is one of the few manufacturers that can offer complete, floor-to-ceiling integrated systems for lifting, pulling, and securing materials—built around the specific demands of each industry.

Then there’s the business that makes all of this stickier: services. Inspections, maintenance, modernization, and parts don’t just add revenue—they build recurring relationships and more predictable cash flows than equipment sales alone. Management has made it clear this is a strategic priority, with goals to meaningfully increase the services mix over time.

All of that adds up to a customer footprint that looks like a map of the modern economy: EV production and aerospace, energy and utilities, process industries, industrial automation, construction and infrastructure, food and beverage, entertainment, life sciences, consumer packaged goods, and the machinery behind e-commerce—supply chain, warehousing, and distribution.

X. Navigating Challenges & Setbacks (2022–2025)

The market’s verdict, at least in the short run, was brutal. Over the last year, Columbus McKinnon’s shares swung from a 52-week high of $41.05 down to a low of $11.78—off about 61% over that stretch.

And the pain intensified into late 2024. From September 2024, the stock fell another 41% over roughly six months, as softer quarterly results collided with a harder question investors couldn’t avoid: what happens when a roll-up story runs into a downcycle?

Because the headwinds weren’t coming from just one direction. Industrial activity cooled across key end markets, and “short-cycle” demand—the kind that shows up quickly in orders—started to fade. At the same time, the debt Columbus McKinnon had taken on to fund years of acquisitions looked more intimidating in a rising-rate environment. Then came the biggest variable of all: the proposed Kito Crosby deal, which would dramatically expand the business but also raise the stakes on execution, integration, and regulation.

You could see that skepticism show up in real time. DA Davidson analyst Matt Summerville downgraded the stock from Buy to Neutral, pointing to weaker short-cycle activity, project delays, and broader macro pressure—right as the company announced its definitive agreement to acquire Kito Crosby Ltd.

The rating agencies followed quickly. S&P Global Ratings put Columbus McKinnon’s ‘B+’ issuer credit rating on CreditWatch with negative implications, citing the leverage expected to come with the acquisition. Moody’s placed both Columbus McKinnon and Kito Crosby under review as well, flagging the same core concerns: high leverage at close, plus the integration risk that comes with a truly transformational transaction.

Then, on May 28, 2025, another layer of uncertainty arrived. The U.S. Department of Justice extended the Hart-Scott-Rodino waiting period for the CMCO–Kito deal by at least 30 days, requesting additional information to evaluate potential antitrust issues. Requests like this are common in large transactions, but they still matter—because they stretch timelines and keep everyone guessing.

Underneath all of it was a more fundamental frustration: the company’s long-term growth and profitability hadn’t looked as sharp as the story sounded. Over the last five years, Columbus McKinnon grew sales at a 3.3% compounded annual rate, below industrial-sector benchmarks. Over that same period, EPS declined about 1.8% annually—meaning the company got bigger, but not more profitable on a per-share basis.

This is the real stress test of the transformation thesis. Can Columbus McKinnon prove that the shift from products to systems and services holds up when the cycle turns? Can it integrate what it’s bought, protect margins, and bring leverage down—without losing the momentum that got it here?

There were signs of resilience. Columbus McKinnon reported Q2 fiscal 2026 EPS of $0.62, about 17% above forecasts, and revenue of $261 million, up 8% year over year—good enough to spark a nearly 18% pre-market jump in the stock. Gross profit rose 21% to $90.2 million, with adjusted gross margin of 35.3% and operating margin of 9.7%, helped by strength in aerospace, energy, and defense. Management also reaffirmed its full-year outlook, calling for low- to mid-single-digit net sales growth.

XI. The Kito Crosby Combination: Doubling Down

In February 2025, Columbus McKinnon went for the biggest swing in its modern history. The company announced a definitive agreement to acquire Kito Crosby Limited from funds managed by KKR in an all-cash transaction valued at $2.7 billion.

KKR had owned Kito Crosby since 2013, and by CMCO’s telling, it used that decade to build scale fast: more than doubling revenue, roughly quadrupling headcount, expanding into new product categories and geographies, and improving safety along the way. By 2024, Kito Crosby was generating $1.1 billion of revenue, selling largely through an extensive global channel partner network.

Kito Crosby, based in Texas, makes and distributes lifting, rigging, transporting, and load-securing products. Its stable of brands reads like a “greatest hits” list for this corner of industrial infrastructure: Kito, Crosby, Harrington, Gunnebo Industries, and Peerless. The company itself was newly stitched together—formed through the early 2023 combination of The Crosby Group, based in Richardson, Texas, and Japan-based Kito Corporation—then rebranded as Kito Crosby in October 2023.

For Columbus McKinnon, the math of the announcement was simple: the combined business was expected to produce about $2.1 billion in annual revenue, with adjusted EBITDA of $486 million and an adjusted EBITDA margin of 23%. In practical terms, CMCO would essentially double in size—adding more than 4,000 employees globally and roughly 40 factories, offices, and distribution sites.

Management also projected $70 million in annual cost savings, and the strategic pitch went beyond expenses. This deal would broaden product scope, increase scale, and materially expand Columbus McKinnon’s geographic reach—especially in Asia—while reinforcing its existing footholds across Latin America, Europe, the Middle East, and Africa.

CEO David Wilson put the rationale in megatrend terms: “Through this strategic combination, we're creating a company that is extremely well-positioned to deliver real-world solutions for customers, with favorable tailwinds from megatrends, including reshoring, infrastructure investment, modernization of aging industrial facilities and rising automation needs due to labor shortages.”

The financing structure underscored just how serious this was. Columbus McKinnon said it would fund the transaction with $3.05 billion of debt financing from J.P. Morgan, plus an $800 million convertible preferred equity investment from Clayton Dubilier & Rice. After the deal closed, CD&R would own approximately 40% of the combined company.

It’s hard to overstate how transformational this could be—and how much has to go right. Integrating two large organizations. Carrying significant leverage in uncertain economic conditions. Clearing regulatory review. And, most importantly, proving that getting bigger actually makes the platform stronger, not just heavier.

XII. The Playbook: How CMCO Actually Works

After decades of doing deals—and learning the hard way what works and what doesn’t—Columbus McKinnon has built something rare in industrials: a repeatable acquisition playbook. The target profile is tight. CMCO looks for niche leaders with strong brands and capabilities it can’t easily build from scratch, ideally in adjacent categories where the same customers and channels already exist. Cultural fit matters, too, because a great product line can still be a bad acquisition if the people who know how to run it walk out the door.

Once a deal closes, integration isn’t left to chance. CMCO runs structured 100-day plans aimed at early momentum: align leadership, stabilize the customer base, standardize the essentials, and start capturing the synergies that justified the purchase. The trick is managing the tension at the heart of every roll-up: standardize enough to get scale benefits, but not so much that you crush the entrepreneurial energy and know-how that made the acquired company worth buying in the first place.

The value creation levers show up again and again: - Cross-selling: putting STAHL products through CM channels and vice versa - Operational improvement: lean manufacturing, footprint optimization, procurement scale - Services attachment: selling maintenance and modernization alongside equipment - Innovation: R&D investments in automation and intelligence

Under the hood, much of this runs through the Columbus McKinnon Business System (CMBS), the company’s operating cadence for continuous improvement, disciplined execution, and accountability. A major focus has been the 80/20 process, with a current priority on simplifying product lines. This isn’t just a cost exercise; it’s about making the portfolio easier to sell, easier to build, and easier to support—while also creating the flexibility to rationalize and simplify the factory footprint over time.

Capital allocation follows the same “balanced, but pragmatic” logic. CMCO has used M&A as the main growth engine, while still investing organically and maintaining a measured dividend. But the obvious limiter is leverage: when debt rises, the range of options narrows, and the company has less room to maneuver if the cycle turns or integration takes longer than planned.

And the cycle always matters here. CMCO manages cyclicality by diversifying end markets—automotive, aerospace, energy, food and beverage, entertainment, e-commerce, and more—so it isn’t hostage to any single sector’s spending pattern. That helps. It doesn’t make the business immune. When manufacturing broadly slows, even a well-diversified motion-control portfolio feels the pull of gravity.

XIII. Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: LOW-MEDIUM

In theory, this is “just” industrial equipment. In practice, it’s hard to break in. You need real manufacturing capability, you need to clear safety and regulatory hurdles, and you need distribution relationships that take years to earn. In niches like explosion-protected lifting, the barriers get even higher. STAHL CraneSystems is a globally recognized name in explosion-protected crane technology with one of the most extensive, seamless product portfolios in the category—and duplicating that capability would require years of engineering work and significant investment.

The wildcard is disruption from the outside. Robotics and automation companies can creep into adjacent material handling applications, and low-cost Chinese manufacturers continuing to scale globally keep pressure on the lower end of the market.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW-MEDIUM

Much of the bill of materials—steel and standard industrial components—is relatively commoditized, with plenty of sourcing options. The squeeze shows up more in specialized electronics and sensors, where fewer suppliers hold more leverage. CMCO’s growing scale helps it negotiate, but it’s not immune when critical components get tight.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MEDIUM-HIGH

The customer base is professional, experienced, and price-aware. CMCO sells to end users directly, but also through a wide set of intermediaries and specifiers: industrial distributors, rigging shops, independent crane builders, material handling specialists and integrators, service-after-sale distributors, OEMs, government agencies, and engineering procurement and construction firms. That breadth gives buyers choices—and choices create leverage.

Still, this isn’t office furniture. When equipment is mission-critical and safety-regulated, “cheapest” isn’t always “best.” Switching costs can be real, especially once controls, parts, and service relationships get embedded. And the more CMCO sells integrated solutions instead of standalone components, the more buyer power comes down.

Threat of Substitutes: MEDIUM

There are plenty of other ways to move things around: conveyors, AGVs (automated guided vehicles), robots, and forklifts. As autonomous mobile robots improve, some applications may shift away from fixed, overhead infrastructure.

But overhead cranes and hoists exist for a reason. In many environments—heavy loads, constrained floorspace, and demanding safety requirements—there’s simply no substitute that matches the combination of capability and practicality.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

This is a crowded arena. Konecranes Oyj, headquartered in Hyvinkää, Finland, is one of the largest crane manufacturers in the world. It specializes in the manufacture and service of cranes and lifting equipment, operates in over 50 countries, and has about 16,800 employees. It also produces about one in ten of the world’s cranes.

Konecranes’ competitors include Terex, Columbus McKinnon, J-TEK, Whiting, and Cargotec. And beyond the global names, the market remains fragmented, with many regional players. That fragmentation fuels constant price pressure in standard products, where differentiation is thin and commoditization is always lurking. The way out is technology, service, and solutions—exactly where CMCO has been trying to move. At the same time, consolidation is raising the stakes at the high end, as scaled players fight harder for premium accounts.

Overall Assessment: It’s a solid industry structure, with real moats in specific niches—but no one gets to coast. The winners are the companies that can climb from products to solutions while staying cost-competitive where the market still behaves like a commodity.

XIV. Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: MODERATE

Scale helps, but it’s not the kind of business where size automatically crushes everyone else the way it can in software or semiconductors. The bigger advantage is downstream: a larger distribution footprint and a wider service network, which make it easier to be present, responsive, and hard to displace. Post-STAHL—and especially if Kito Crosby closes—CMCO’s global scale becomes more meaningful as a competitive edge.

Network Effects: LOW

There aren’t many classic network effects here. A hoist doesn’t become more valuable because more people use the same hoist. But there is a possible future version of this business where connected equipment creates something network-effect-like: the more assets you have in the field sending data, the better you get at diagnosing issues and predicting maintenance.

Counter-Positioning: LOW-MODERATE

CMCO is trying to move from products to solutions while some competitors remain anchored in a product-first mindset. That can be an advantage—until it isn’t. Because if competitors decide to invest, this shift is not impossible to copy.

Switching Costs: MODERATE-HIGH

This is CMCO’s strongest power. The equipment is long-lived—often measured in decades—so ripping it out and changing vendors is disruptive and expensive. The aftermarket deepens the lock-in: parts, service, inspections, modernization, and the installed base all reinforce the relationship. And once customers buy integrated systems instead of standalone products, the switching costs jump again. In mission-critical applications, trust becomes a form of friction—and CMCO’s established brands benefit from that.

Branding: MODERATE

In industrials, brand is reputation under pressure: does it work, does it last, and is it safe? CMCO has that credibility in its channels, and STAHL CraneSystems carries real weight for reliable, safety-focused hoists and crane components backed by methodical engineering. It’s not consumer-facing branding, but in safety-critical environments, trust is everything.

Cornered Resource: LOW-MEDIUM

CMCO has pockets of “hard to replicate” advantage: proprietary technologies in radio controls and motion control (Magnetek), precision conveying know-how (Dorner), and the regulatory and certification depth behind explosion-protected equipment (STAHL). None of these are absolute monopolies, but they’re meaningful hurdles. Skilled service technicians and deep customer relationships matter too, even if they’re not fully exclusive.

Process Power: MODERATE

After years of deal-making, CMCO’s ability to source, buy, and integrate businesses is becoming a real capability—not just a strategy. The Columbus McKinnon Operating System is meant to turn acquisitions into repeatable execution: shared practices, efficiency gains, and the kind of organizational learning that compounds over time.

Overall Assessment: CMCO’s powers have strengthened as it’s transformed. Switching costs, paired with emerging global scale and growing process power, could become durable advantages—if execution holds. The question is whether CMCO can build those moats fast enough before larger industrial conglomerates or PE-backed roll-ups outmuscle them.

XV. Bull vs. Bear Case

The Bull Case:

The big bull argument starts with the same forces that have reshaped modern factories: automation is not a fad, and labor constraints aren’t going away. As customers push for more throughput with fewer hands, demand for intelligent motion solutions should grow faster than the broader economy. CMCO’s shift from selling standalone products to selling systems and solutions puts it in a better position to earn premium pricing, win bigger projects, and attach recurring services.

The second pillar is the playbook. Over the past decade, management has shown it can find, buy, and integrate businesses that add real capabilities—then pull synergies out of them. If the Kito Crosby deal closes and integration goes well, CMCO doesn’t just get bigger; it gets meaningfully more global and more relevant across lifting, rigging, and motion control.

Then there are the megatrends that show up on basically every industrial CEO’s whiteboard right now: reshoring, infrastructure investment, modernization of aging facilities, and rising automation needs driven by labor shortages. Those forces all translate into more equipment, more systems, and more aftermarket work—exactly where CMCO wants to be.

Services is the underappreciated part of the upside. A growing services mix typically means higher margins, more predictable revenue, and deeper customer lock-in. The more CMCO sells solutions, the more it can become a long-term partner rather than a vendor—a shift that tends to show up in both profitability and resilience through cycles.

And to the extent reshoring accelerates, CMCO’s North American footprint can be a real advantage. When production moves closer to end markets, new and upgraded facilities still need the basics: lifting, positioning, and material flow equipment—plus the controls and service infrastructure to keep it running.

On Wall Street, that optimism shows up in expectations: the average 12-month price target for Columbus McKinnon is USD27.75, with a high estimate of USD34 and a low estimate of USD15. Three analysts recommend buying the stock.

The Bear Case:

The bear case starts with gravity: this is still an industrial business, and cyclicality still bites. When manufacturing rolls over, customers delay projects, distributors work down inventory, and “short-cycle” orders drop fast. CMCO’s recent revenue declines are a reminder that transformation doesn’t automatically make you cycle-proof.

There’s also the longer-term growth question. Over the last five years, Columbus McKinnon grew sales at a 3.3% compounded annual rate, below benchmarks for the industrials sector. If the company can’t convert its portfolio upgrades into faster organic growth, then the whole story risks becoming “a roll-up that got bigger,” rather than “a platform that got better.”

Leverage is the other big constraint. Debt can amplify returns when conditions are good, but it narrows your options when rates rise or demand softens. S&P Global Ratings put Columbus McKinnon’s ‘B+’ issuer credit rating on CreditWatch with negative implications due to the leverage expected from the acquisition—exactly the kind of signal that makes investors skittish.

Then comes the execution risk. CMCO has done plenty of integrations, but a transformational deal like Kito Crosby raises the difficulty level. Too many moving pieces at once can strain management bandwidth, slow down synergy capture, and distract the organization from customers.

Competition doesn’t make this any easier. Pressure from low-cost Chinese manufacturers can squeeze the lower end of the market, while large automation players can outspend on technology and solutions at the top end. And in some applications, technology shifts—like AGVs and autonomous mobile robots—could reduce the total addressable market for fixed infrastructure.

Finally, the cash flow picture has been uneven. Columbus McKinnon’s free cash flow margin dropped by 12.8 percentage points over the last five years. In a business carrying meaningful leverage and relying on execution to justify a transformation, weaker cash generation can quickly turn from an annoyance into a real limitation.

XVI. Key Performance Indicators for Investors

If you want to track whether Columbus McKinnon’s transformation is real—and not just a bigger collection of acquired brands—three KPIs do most of the work:

1. Adjusted EBITDA Margin: This is the cleanest scoreboard for the shift from “dumb iron” to higher-value systems, controls, and services. In fiscal 2024, adjusted EBITDA margin was 16.4%, up 60 basis points. From here, the key question is whether margins keep climbing as the portfolio gets more solution-heavy, and whether the company can move toward the roughly 23% margin profile it has described for the combined business post-Kito Crosby.

2. Services Revenue as Percentage of Total: Services are where cyclicality softens and customer relationships deepen. Inspections, maintenance, modernization, and parts can turn a one-time equipment sale into a long-lived annuity. The tell is simple: does the services mix keep expanding quarter after quarter?

3. Net Leverage Ratio: CMCO has used debt to fund its transformation, and the Kito Crosby deal would raise the stakes further. So the leverage ratio becomes a proxy for optionality. If free cash flow can steadily bring leverage down while the company still invests in growth, CMCO keeps control of its destiny. If not, the balance sheet starts making strategic decisions for them.

XVII. Epilogue & What's Next

Columbus McKinnon is standing on the edge of a fork in the road. If the Kito Crosby combination closes and gets integrated well, CMCO won’t just be a larger hoist company—it will become a materially bigger, more global motion-and-rigging platform, with roughly $2.1 billion of annual revenue and a far broader mix of end markets. But the trade-offs are real: the execution bar is higher than anything the company has attempted before, leverage will be heavy, and the industrial cycle doesn’t stop being the industrial cycle just because the strategy is good.

Management has said it expects the acquisition to close by fiscal year-end, and that the combined company would have around $2 billion of sales after the deal. That’s the upside version of the future: scale, diversification, and a portfolio that can show up as a full-solution provider across lifting, rigging, and intelligent motion.

From there, the work shifts from buying to building. Integration becomes the job. So does pushing the technology forward—connected equipment, smarter controls, and predictive maintenance that turns downtime from a surprise into a scheduled event. And if the company can deleverage on plan, it keeps the option open to keep stitching in smaller, targeted bolt-on acquisitions that strengthen the platform rather than distract it.

The macro backdrop supports the thesis. Factories keep leaning toward automation. AI-enabled predictive maintenance is becoming more practical. Fully autonomous production environments are no longer science fiction. And sustainability requirements are forcing modernization across aging industrial facilities. Layer on the “Amazon effect”—e-commerce continuing to drive distribution center buildouts and automation—and you get a world where moving, lifting, and positioning equipment isn’t going away. It’s getting more sophisticated.

But it’s worth asking the uncomfortable question: what if the bull case doesn’t play out? The downside scenarios aren’t exotic. A real industrial recession could force painful restructuring. Competitive intensity could compress margins right when the balance sheet has the least flexibility. Or the integration itself could become the sinkhole—absorbing management bandwidth and slowing organic growth at the exact moment the company needs to prove the transformation is real.

So the investor’s question is straightforward and brutal: is CMCO a value trap—a stock that looks cheap because the risks are earned—or is it a transformation story that the market has discounted too far? Over the next two to three years, the answer will come down to execution, and very little else.

XVIII. Further Reading

Top 10 Resources:

-

Columbus McKinnon Investor Relations (investors.cmco.com) - Annual reports and investor presentations from 2014 to the present tell the transformation story in management’s own words.

-

"The Outsiders" by William Thorndike - A useful lens on capital allocation, disciplined decision-making, and why the best operators often look boring—right up until the results compound.

-

Konecranes Annual Reports - The cleanest way to understand the competitive landscape through the eyes of one of the global category leaders.

-

Modern Materials Handling - Great industry coverage on automation, labor constraints, and how distribution and manufacturing are evolving.

-

"Lift and Hoist International" - The trade-level view of hoists, cranes, regulations, and market structure—helpful for separating signal from noise.

-

McKinsey on Industry 4.0 - Research on the broader automation and connected-factory shift that underpins CMCO’s “intelligent motion” thesis.

-

SEC Filings (10-K, 10-Q) - Where the real details live: segment performance, cash flow, debt, and how integration is actually going.

-

Manufacturing Leadership Journal - Smart manufacturing, Industrial IoT, and the kind of real-world adoption stories that show what “connected products” actually mean.

-

CMCO Earnings Call Transcripts - The fastest way to track how management is thinking in real time—especially when the cycle turns and expectations reset.

-

Hamilton Helmer’s "7 Powers" - A sharp framework for judging whether CMCO’s strengths—like switching costs and process power—can become truly durable.

Columbus McKinnon’s story is, at its core, about adaptation. A company with roots in an era when chains were built for wagons now sells intelligent motion systems into automated factories and modern distribution networks.

The world will always need to lift, move, and position heavy things. The harder question is whether CMCO can turn that eternal demand into enduring advantage—while managing a cyclical customer base and executing M&A at increasingly high stakes.

The shift from “dumb iron” to “intelligent motion” still isn’t finished. But the direction is unmistakable, the capability stack has gotten deeper, and the opportunity set is real. Whether that becomes a great investment comes down to the unglamorous part of every transformation story: integration, discipline, and execution over the next few years.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music