Celestica: The Hidden Engine of the AI Cloud

I. Introduction: The "Picks and Shovels" of the Data Center

Somewhere inside a hyperscale data center in Oregon, an AI model is learning to see. Thousands of GPUs churn through training runs, pulling so much power and throwing off so much heat that yesterday’s cooling playbook would tap out. But the real magic isn’t just inside the chips. It’s in everything around them: the networking gear that keeps the GPUs fed, the racks engineered to survive brutal thermal loads, the storage built to keep up with relentless reads and writes.

That’s where the story gets interesting.

Because a lot of that gear doesn’t say Nvidia. It doesn’t say Google or Amazon either. Often, it’s built by a company most investors have barely heard of: Celestica.

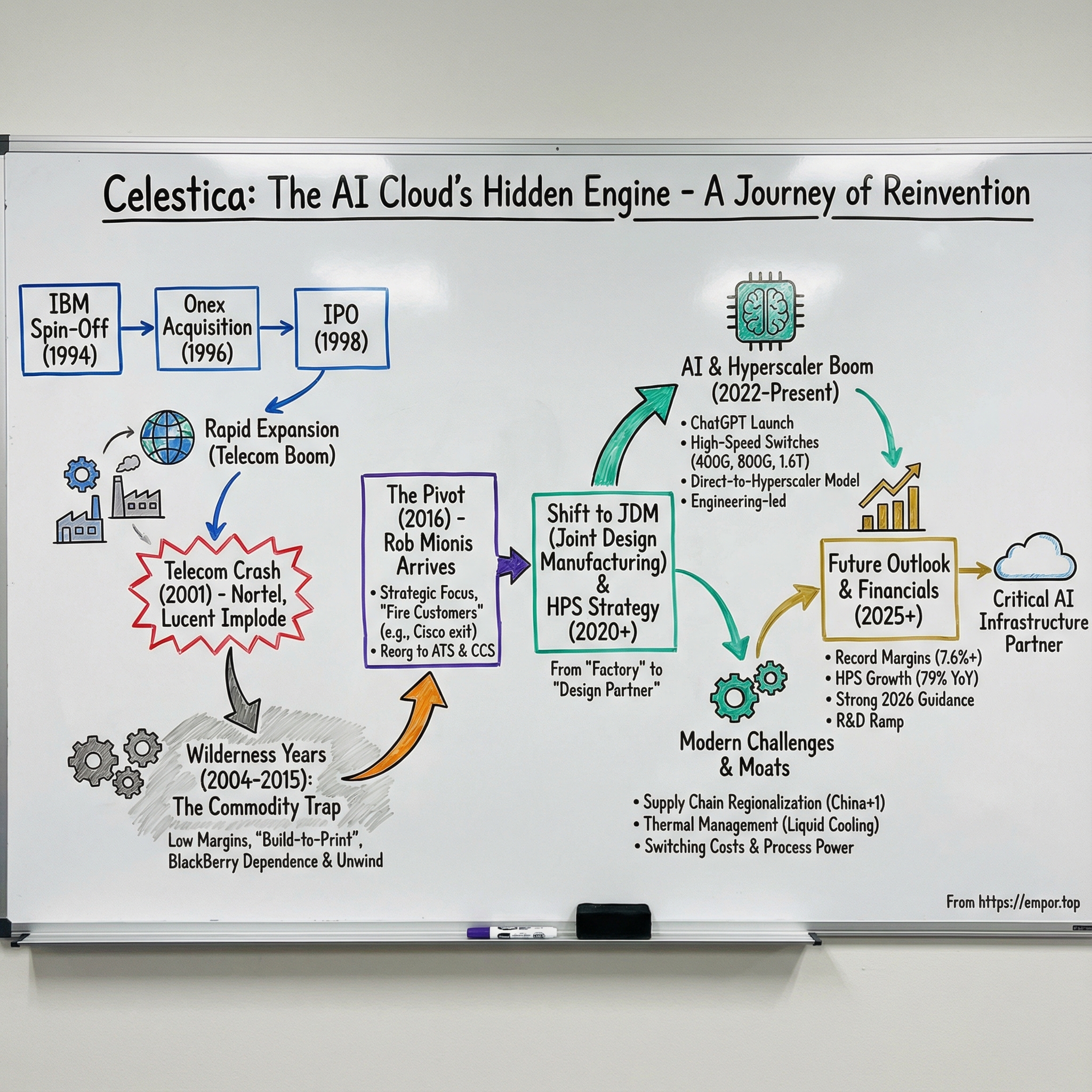

Over the last year, Celestica’s stock surged, riding a wave of AI infrastructure spend and a very specific kind of growth: hyperscalers rebuilding the guts of their data centers to move vastly more data, vastly faster. For decades, Celestica was the definition of “in the background”—a contract manufacturer living at the mercy of customers’ product cycles. So how did an IBM Canada spin-off that spent years in the wilderness turn into one of the market’s standout winners of the AI boom? And how did it pull ahead of better-known peers like Flex and Jabil?

To answer that, you have to understand what Celestica used to be—and what it deliberately chose to become.

The old Celestica looked like a classic electronics manufacturing services company. Customers sent the design; Celestica built it. It was essential work, but it was also low-margin and brutally competitive. If all you offer is capacity and execution, you’re a commodity. Someone, somewhere, will always do it cheaper.

The new Celestica is something else. Today, it positions itself as a design-centric technology partner: an electronics platform integrator that co-develops and manufactures the hardware inside modern cloud and AI infrastructure. Think of it as the company helping design and build the custom plumbing of the AI era—switches, storage systems, and connectivity solutions that move data between GPUs at mind-bending speeds.

The financials show the shift. In 2024, Celestica generated $9.65 billion in revenue, up from $7.96 billion the year before, and earnings rose to $428 million. The market rewarded that transformation, too, pushing Celestica’s market cap to more than $35 billion—light-years from the days when it was valued like just another contract factory.

But this wasn’t a straight line. Celestica’s path runs through boom-and-bust cycles, near-death experiences, and one strategic pivot so severe it effectively reinvented the company. This is the story of how a Canadian contract manufacturer shed its commodity skin—and became a critical enabler of the AI revolution.

II. The Blue Blood Origins: IBM Canada & The Spin-Off

To understand where Celestica came from, you first have to remember what IBM was in the 1980s: a vertically integrated empire. In the 1970s and much of the 1980s, IBM dominated the computer world like a heavy-footed colossus, leasing big mainframes to corporate customers—and building virtually everything itself. Components, enclosures, cabling, assembly. Outsourcing manufacturing wasn’t a strategy. It was a kind of heresy.

The person who spotted the crack in that worldview, at least in one corner of IBM, was Eugene Polistuk. A University of Toronto engineering grad from 1969, Polistuk joined IBM Canada and climbed through senior management roles on both sides of the border. By 1986, he was running IBM Canada’s Toronto manufacturing unit—an operation that, among other things, produced the physical boxes that housed IBM components.

From that vantage point, the shift inside IBM was impossible to miss. The company was beginning to pivot away from low-margin equipment and toward software and services. Cost pressure mounted. Layoffs followed. And suddenly, even a proud manufacturing organization inside Big Blue didn’t feel untouchable anymore.

A spin-off started to look like the obvious move. The problem was that IBM didn’t exactly have a sterling reputation for making spin-offs work.

Polistuk, though, didn’t see a doomed legacy asset. He saw a business that could stand on its own—lean enough, efficient enough, and, most importantly, able to do something it couldn’t do under the IBM name: sell to IBM’s rivals. Plenty of companies didn’t want Big Blue anywhere near their supply chain. But an arm’s-length supplier with IBM-grade discipline? That was a different proposition.

IBM bought the argument. In January 1994, Celestica was formed as a wholly owned subsidiary of IBM Canada. The name was meant to feel aspirational—something cosmic, something reaching upward. But the reality was more grounded: Celestica was still inside IBM’s orbit, and Polistuk knew real independence would take outside capital.

He also knew independence would require a different kind of culture. One of his early moves was a 5% pay cut paired with a profit-sharing program that could pay out up to 30% of base salary. It wasn’t just belt-tightening. It was a deliberate attempt to turn career IBM employees into owners—people who would think and act like entrepreneurs, not caretakers of a legacy division.

The decisive break came in 1996. In October, Onex Corporation acquired Celestica from IBM for $750 million. Onex—founded by Gerry Schwartz and quickly becoming a major force in Canadian private equity—saw what Polistuk saw: a manufacturing operation with world-class quality systems that, once freed from IBM, could compete broadly.

Then Celestica hit the gas.

In a short span after the divestiture, the company expanded from Toronto to 24 facilities across seven countries, added roughly 12,000 people, and pushed hard on customer diversification. The ambition wasn’t subtle. Management talked openly about building the infrastructure to reach $10 billion in sales by 2001.

In 1998, Celestica stepped onto the public stage. On June 29, it launched its IPO, agreeing to sell 20.6 million shares at $17.50 each and raising $414 million—at the time, the largest technology IPO in Canadian history. The message was clear: this wasn’t a slow, careful carve-out. This was a global expansion story.

And the buying spree had already begun. In February 1998, Celestica purchased a manufacturing facility in Monterrey, Mexico, from Lucent Technologies—its first Mexican footprint. It expanded into Europe by taking over a facility in Dublin, Ireland, from Madge Networks. The pace only intensified: eight deals in 1998 alone, including the acquisition of International Manufacturing Services, which brought facilities in Thailand, Hong Kong, and China.

By the end of that year, Celestica was doing about $3.2 billion in annual revenue.

The bet underneath all of this was simple and, at the time, extremely compelling: OEMs would stop building their own hardware. Companies like Dell, HP, and Cisco would focus on design, branding, and sales, and they’d outsource the messy, capital-intensive reality of manufacturing. Celestica—armed with IBM’s engineering rigor and quality culture—would become the trusted builder behind the builders.

For a few golden years, it worked. Spectacularly.

But it also set up the question that would define Celestica’s next chapter: what happens when your best customers stop ordering?

III. The Icarus Moment: The Telecom Bubble & The Crash

In the late 1990s, if you sat anywhere in the telecom supply chain, it felt like the ground was shaking—in a good way. The Telecommunications Act of 1996 deregulated the U.S. market and kicked off a wave of spending that turned into a full-blown arms race. By 2000, telecom capital expenditure peaked at roughly $121 billion. Fiber was being laid across continents. New carriers were popping up overnight. And every one of them needed boxes, boards, and systems shipped yesterday.

Celestica leaned into it hard. It kept buying factories to keep up, chasing the demand curve and filling its customer roster with the era’s giants: Nortel, Lucent, Motorola. In 2001, it acquired Omni Industries Limited and signed a US$10 billion supply deal with Lucent Technologies. A ten-billion-dollar deal with Lucent alone. At the time, it looked like the kind of contract that could power a decade of growth.

Then the music stopped.

The turn hit in a single, dramatic headline on February 15, 2001. Nortel, halfway through its first quarter, abruptly slashed its guidance. This wasn’t the usual penny-or-two adjustment investors had come to expect. Nortel went from forecasting a $0.16 profit per share to a $0.04 loss. Markets that were already jittery snapped. And once the confidence broke, it didn’t come back.

The scale of Nortel’s rise—and fall—was hard to overstate. At its peak, Nortel represented more than a third of the entire Toronto Stock Exchange’s total valuation, with 94,500 employees worldwide and 25,900 in Canada. Then came the collapse: its market cap cratered from C$398 billion in September 2000 to under C$5 billion by August 2002, and the stock slid from C$124 to C$0.47.

For Celestica, this wasn’t just a customer wobbling. This was the foundation cracking.

Celestica’s exposure wasn’t only to telecom, but to “big iron” tech customers like IBM and Sun Microsystems too. The model worked beautifully as long as those giants were selling lots of gear—and ordering lots of manufacturing. When their end demand dried up, Celestica’s orders dried up. And because factories come with fixed costs, the downside hit faster than anyone wants to admit in a boom.

The first visible cut came in April 2001, when Celestica announced layoffs of 3,000 people—about 10% of its workforce—blaming the dot-com crash. But it didn’t stop there. The financial pain stacked up year after year: a $51 million loss in 2001, nearly a $500 million loss in 2002 as sales plunged, then another steep drop the following year to about 70% of 2001 levels, with losses reaching $266 million. Layoffs, plant closures, writedowns—more than $1 billion in special charges piled up over three years.

This is the moment Celestica learned the hard rule of contract manufacturing: volume is vanity, concentration is deadly. It had built around the assumption that a handful of massive customers would keep ordering. When those customers faltered—Nortel imploding, Lucent stumbling, Sun beginning its long decline—Celestica had nowhere to hide.

By January 29, 2004, the fallout had reached the top. Celestica announced that CEO Eugene Polistuk would retire. The founder who had persuaded IBM to spin the business out, guided it through Onex’s acquisition, and took it public in a record-setting Canadian tech IPO was leaving in the aftermath of a business model that had looked nearly unstoppable just a few years earlier.

In April 2004, Stephen Delaney stepped in as CEO on a temporary basis. Over the years, leadership would keep changing as the company searched for a stable identity in the post-bubble world.

But the most important thing Celestica took from the crash wasn’t a cost-cutting playbook. It was a strategic scar that would shape the next two decades: if you’re only a contractor, you live and die by your customer’s cycle. To survive—and eventually to thrive—you have to be more than a pair of hands. You need to own something: design, IP, and relationships that make you harder to replace.

IV. The Wilderness Years: The "Commodity Trap"

The years between 2004 and 2015 were Celestica’s wilderness years. The company survived, but it didn’t really win. It was stuck in the middle—too expensive to out-Foxconn Foxconn, and too undifferentiated to command real pricing power.

That was the trap. Electronics Manufacturing Services had matured into a brutal, global auction: who can build it cheapest, fastest, with the least drama? In that world, the advantage goes to sheer scale and the lowest-cost footprint. Foxconn became the emblem of that model—an industrial machine optimized for high-volume consumer electronics, where pennies matter and suppliers get squeezed until they squeak. If your primary pitch is “we have factories,” and your competitors have bigger factories in lower-cost countries, the math is merciless.

Celestica kept looking for the next growth engine, and for a while it found one at home: BlackBerry—then Research In Motion—the Canadian smartphone pioneer that, for a moment, looked like it might own the mobile era. Celestica built BlackBerry devices like the Bold and Curve in Mexico for the North American market, and the relationship became enormous. At its peak, RIM accounted for nearly 30% of Celestica’s revenue.

Which, after the Nortel experience, should sound like a warning siren.

When the iPhone arrived and BlackBerry’s grip on the market started to slip, Celestica’s exposure flipped from tailwind to trap. RIM began shrinking its supplier base to cut costs, and Celestica announced it would wind down manufacturing services for RIM over the following months, working through a transition period as BlackBerry reworked its supply chain. Another iconic customer. Another concentrated bet. Another painful unwind.

All of it showed up in the numbers, but the bigger story was what the numbers represented. For most of that decade, Celestica’s operating margins sat in the low single digits. That’s not “we’re investing for the future” profitability. That’s “we’re fighting for air” profitability. Investors treated it accordingly: a low-value manufacturer, easily replaced, with little control over its destiny.

The market’s perception hardened into something close to an insult: Celestica as a “dumb pipe”—a company that added value mainly by owning buildings, labor, and equipment. And Celestica didn’t have a clean identity to counter it. It wasn’t the cheapest assembler, and it wasn’t yet seen as a premium engineering partner. It was stuck between strategies, and the industry punished that kind of indecision.

Something had to break. And in 2015, it did—when a new CEO arrived with a very different playbook.

V. The Inflection Point: The 2016 Pivot

Rob Mionis took over from Craig Muhlhauser on August 1, 2015. If Celestica needed a CEO built for a turnaround, Mionis fit the spec.

He arrived with more than 25 years of senior leadership across aerospace, industrial, and semiconductor markets. Just before Celestica, he was an Operating Partner at Pamplona Capital Management—a private equity firm with a reputation for treating businesses like portfolios to be sharpened, not museums to be preserved. Earlier, he spent more than six years as President and CEO of StandardAero, one of the world’s largest independent aerospace maintenance, repair, and overhaul companies.

That background mattered. Private equity trains you to look at a company with ruthless clarity: Which programs are earning their keep? Which customers are quietly destroying your margins? What would you do if you didn’t care about how the answer “felt”?

Mionis brought that discipline to a public company that had spent years drifting in the commodity trap. And his strategy, once you strip away the management-speak, was straightforward: stop chasing revenue for revenue’s sake. Start chasing returns and strategic value instead.

Which led to the move that sounds simple in a boardroom and feels brutal in real life: fire customers.

The defining example was Cisco. For years, Cisco had been Celestica’s largest customer—at one point nearly a fifth of total revenue. But the economics weren’t good enough, and they were getting worse. As Celestica later acknowledged, its Communications end market had been hit by “program-specific market dynamics” that pushed returns below the company’s targets. After trying to renegotiate, Celestica and Cisco agreed to a phased exit of existing programs beginning in 2020.

By late 2019, Cisco still represented 13% of consolidated revenue—an amount Celestica estimated would total roughly $750 million for the year. Walking away from that much business isn’t a tweak. It’s a statement.

But the logic was clear: if the biggest customer is dragging down margins and tying up working capital, then losing that revenue can actually make the company healthier. Even outside observers framed it the same way—painful, tedious, and likely the right decision.

The Cisco exit was completed in the fourth quarter of 2020. And it did what Celestica needed it to do: it cleared space for higher-margin, more strategic work that fit the company Mionis was trying to build.

At the same time, Celestica reorganized itself into two customer-focused engines: Advanced Technology Solutions (ATS) and Connectivity & Cloud Solutions (CCS).

This wasn’t just reporting housekeeping. It was a declaration of identity.

ATS—think aerospace and defense, medical technology, and industrial—leaned into high-reliability, regulated markets where quality systems and engineering discipline aren’t nice-to-haves; they’re the price of admission. CCS—communications and enterprise servers—became the platform for the company’s bigger bet on cloud infrastructure, and eventually, AI.

The most important shift, though, wasn’t in org charts. It was in where Celestica chose to sit in the value chain.

Mionis pushed investment into Joint Design Manufacturing, or JDM. Management talked openly about “investing in higher margin services” like JDM as new programs ramped. The concept was simple: Celestica wouldn’t just build what a customer handed them. It would co-design the product, then manufacture it.

That changes everything. “Build to print” makes you replaceable. JDM makes you sticky. If you’re involved from the design phase, you understand the roadmap, influence the architecture, and accumulate know-how that doesn’t transfer cleanly to the next bidder. In practice, it meant Celestica was trying to stop being a factory on call—and start being a technology partner.

The transformation didn’t happen overnight. For years, investors stayed skeptical, anchored to the old Celestica story. In early 2023, Onex Corp. announced it would exit its investment, selling shares in two tranches priced at US$12.40 and around US$20—levels similar to where Celestica had traded all the way back in 2004. Around the same time, Letko Brosseau & Associates, then the company’s largest public shareholder, said it planned to start selling down its 13-million-share position.

And then came ChatGPT.

VI. The Hardware Platform Solutions (HPS) Strategy

The launch of ChatGPT in November 2022 didn’t just light a fire under OpenAI. It reset priorities across the entire AI supply chain. Overnight, the work Celestica had been quietly doing for years—high-speed networking, custom data center infrastructure, the unglamorous “plumbing” of the cloud—stopped being a niche capability and became a gating factor.

And this wasn’t a small shift in product mix. It was a shift in what Celestica was.

By 2020, Celestica had introduced its first 400G switch and, in the process, planted a flag in the high-performance Ethernet switch market inside a business it called Hardware Platform Solutions. That launch matters because it marked the moment Celestica started moving from “build what we’re told” to “help design the platform, then build it at scale.”

So what is Hardware Platform Solutions, exactly?

Inside Celestica’s Connectivity & Cloud Solutions segment, HPS became the engineering-led effort to bundle hardware, software, and lifecycle services into repeatable platforms for cloud and hyperscale customers. Instead of being the factory at the end of the chain, Celestica positioned itself earlier—where requirements are set, architectures are chosen, and the hard engineering tradeoffs get made.

And the products HPS focuses on are the kinds of things AI data centers can’t live without. Take Celestica’s DS5000, a high-performance 800GbE switch in the HPS portfolio. It delivers next-generation networking density—64 OSFP 800GbE ports in a 2U form factor—built around Broadcom’s StrataXGS Tomahawk 5 Ethernet switch chip.

The timing, in hindsight, was almost unfair.

Because when AI workloads exploded, the bottleneck wasn’t only “do we have enough GPUs?” It was “can we move data between those GPUs fast enough to keep them from sitting idle?” Training large language models means thousands of GPUs operating like a single organism, constantly exchanging data. If the network can’t keep up, the whole system chokes.

Celestica’s pivot toward higher-value platform work showed up in its financial profile as that demand ramped. In Q3 2025, the company reported record operating margin of 7.6%, alongside strong growth in HPS—up 79% year over year—and HPS had grown to represent 44% of total revenue. The company also pointed to strong share in high-bandwidth Ethernet switching (200G/400G/800G) and custom solutions, reinforcing that this wasn’t just a one-off win—it was a position being built.

But HPS didn’t work without another critical shift: who Celestica sold to.

Rather than staying behind the traditional OEMs—Dell, HP, Cisco—Celestica pushed toward a direct-to-hyperscaler model. It started selling straight to the companies building the biggest clouds: Meta, Google, and others. And those customers optimize for something different. They care about engineering quality, speed of iteration, and reliable delivery at scale—not just the lowest bid.

That shift became a growth engine. In fiscal year 2024, Celestica’s hyperscaler business rose 66% year over year to $4.8 billion, representing half of total revenue.

The moat here isn’t only the metal.

Celestica built out a global software engineering team—nearly 400 dedicated engineers—with deep SONiC expertise, plus the ability to customize, harden, and support features for bespoke customer deployments. For hyperscalers running proprietary network operating systems, Celestica can support switch abstraction interfaces, help ensure interoperability with the underlying silicon, and assist with debugging and testing. That pulls Celestica further up the stack—from hardware supplier to system-level partner—and raises switching costs in a way pure manufacturing never can.

By October 2025, Celestica was rolling out the next wave: two 1.6TbE data center switches, the DS6000 and DS6001, based on Broadcom’s Tomahawk 6, delivering up to 102.4Tbps of switching capacity—explicitly aimed at high-bandwidth AI/ML data center applications.

The industry started treating Celestica like a leader, not a subcontractor. As the company highlighted at the time, it had earned the 2024 Dell’Oro Market Share Leader Awards for both Ethernet Switch – AI Networks and High-Speed Networks—validation that it wasn’t just participating in the trend, it was helping define it.

You could see it in the quarterly results too. In Q3 2025, Connectivity & Cloud Solutions revenue rose to $2.41 billion, up 43% year over year, with segment margin improving to 8.3%. HPS alone delivered about $1.4 billion in revenue, up 79% from the prior year.

Put it all together and the punchline is simple: the “new Celestica” wasn’t selling commodity capacity anymore. It was selling design capability, IP, and deeply integrated customer relationships—exactly the kind of work that compounds, exactly the kind that’s hard to rip out once it’s in.

And that’s why, when AI spending surged, Celestica didn’t just catch a wave. It looked like a company that had been building toward it all along.

VII. The Modern Era: AI, Complexity & Supply Chains

Celestica’s AI moment didn’t arrive in a vacuum. It collided with another, equally important shift: the global supply chain started to fracture.

As U.S.–China tensions escalated, “China-only” manufacturing stopped looking like a best practice and started looking like a liability. Big customers moved to “China Plus One,” spreading production across multiple countries to reduce geopolitical and tariff risk. And suddenly, Celestica’s long-built footprint—especially in Thailand, Malaysia, and Mexico—wasn’t just nice to have. It was leverage.

The irony is that this footprint wasn’t built for today’s headlines. It was built decades earlier, during Celestica’s expansion sprint. In 1998, the company acquired International Manufacturing Services (IMS), establishing operations across Japan, Thailand, Hong Kong, and China. That same year, Celestica set up its first major manufacturing presence in Mexico by acquiring Lucent Technologies’ facility in Monterrey. The following month, it expanded into Europe with the acquisition of Madge Networks’ Dublin, Ireland operation.

Those moves now read like a hedge against the modern world—whether management intended it or not.

Thailand, in particular, became a heavyweight site. It offers the full stack: engineering and design services, supply chain management, printed circuit board assembly, box build, direct order fulfillment, and after-market services. It also houses a regional technology center, a failure analysis lab, and a clean room—exactly the kind of infrastructure you need when you’re building complex systems where “good enough” isn’t good enough.

By this point, Celestica wasn’t a single-country manufacturer at all. It’s a Canadian multinational headquartered in Toronto, operating across 50 sites in 15 countries. That scale gives customers something they value more every year: options. If a program can’t be built in one place—because of tariffs, politics, capacity constraints, or lead times—Celestica can often move it without starting from scratch.

That flexibility shows up in how the company talks about supply chain strategy. It has localized production in North America for hyperscalers and in Asia for emerging markets, designed to reduce exposure to shifting trade policies like U.S. Section 232 tariffs and potential semiconductor duties. In a world where resilience is becoming as important as cost, that regionalization has turned into a competitive edge.

Then there’s the other “hidden” constraint of the AI era—one that has nothing to do with geopolitics and everything to do with physics: heat.

AI infrastructure pulls enormous power. Power becomes heat. And the old data-center playbook—air-cooling at scale—starts to break down. Liquid cooling isn’t a futuristic add-on anymore; it’s quickly becoming table stakes for dense AI deployments.

Celestica has leaned into that reality with thermal management systems built for the high-heat profile of AI accelerators. That includes liquid cooling solutions for data centers, along with advanced airflow and containment systems. The work is deeply collaborative: Celestica’s engineers co-design with silicon partners to push performance within tight thermal limits. The company points to rack-level and data center-level solutions including Cooling Distribution Units, cold plates, and manifolds—hardware that sounds mundane until you realize it can determine whether an AI rack runs at full speed or gets throttled.

The industry’s numbers underline the urgency. TrendForce notes that power consumption for GPUs and ASIC chips in AI servers has risen sharply. NVIDIA’s GB200/GB300 NVL72 systems, for example, are cited at roughly 130 to 140 kW per rack—far beyond what traditional air-cooling was built to handle.

Even Celestica’s networking gear is being designed with this new thermal world in mind. The DS6001, while maintaining the same overall networking performance as the DS6000, is built to operate in a hybrid cooling environment, using a mix of air and liquid cooling. It’s a 2U switch designed for a 21-inch OCP ORv3 rack—another signal that hyperscale AI infrastructure is becoming its own engineering category, not just “servers, but bigger.”

And the financials started to validate what the strategy implied.

In the third quarter of 2025, Celestica reported revenue of $3.19 billion, up 28% from the third quarter of 2024. GAAP earnings from operations rose to 10.2% of revenue, versus 5.5% a year earlier. Adjusted operating margin came in at 7.6%, up from 6.8%. GAAP EPS increased to $2.31 from $0.75, and adjusted EPS rose to $1.58 from $1.04.

The outlook moved up with it. Celestica guided Q4 revenue to $3.325 billion to $3.575 billion, and Q4 adjusted EPS to $1.65 to $1.81. It raised its 2025 revenue outlook to $12.2 billion (from $11.55 billion) and adjusted EPS to $5.90 (from $5.50). For 2026, the company shared a preliminary outlook of $16.0 billion in revenue, non-GAAP operating margin of around 7.8%, adjusted EPS of $8.20, and a free cash flow target of $500 million.

This is what the turnaround looks like when it’s real. The company that once struggled to hold 3% margins was now operating near 8%, with a supply chain footprint built for a fractured world and a technical toolkit built for AI’s heat and complexity.

The market’s re-rating wasn’t just a momentum trade. It was recognition that Celestica had stopped being a commodity manufacturer—and started behaving like a compounder.

VIII. The Playbook: Analysis & Frameworks

So the turnaround is real. The margins are real. The hyperscaler demand is real. The question that matters now is the one the market always asks after a great run: is Celestica’s edge actually durable, or is this just a cycle in disguise?

A useful way to pressure-test that is to run the business through a couple of classic frameworks.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis:

Switching Costs: This is Celestica’s clearest power. In the JDM model, Celestica doesn’t just assemble a product—it helps design it, and in many cases owns or co-owns key pieces of the design IP. That makes the relationship far stickier than traditional contract manufacturing. A hyperscaler can’t simply move production to another supplier like Foxconn without losing the people who understand the architecture, the validation work, the test processes, and the software customization that makes the system behave in the real world. When Celestica holds the blueprints, it’s no longer just providing capacity. It’s providing continuity.

Process Power: The IBM heritage shows up here. Celestica has built a vertically integrated playbook—design, engineering, manufacturing, supply chain management, software, and aftermarket services—that’s hard to replicate quickly. High-mix, low-volume, high-complexity builds are exactly where process becomes a moat. Think aerospace electronics and AI networking systems, where qualification, reliability, and failure analysis are as valuable as the hardware itself. In those environments, “good enough” doesn’t ship. Celestica’s quality systems, and the institutional muscle memory behind them, are the product.

Counter-Positioning: While giants like Foxconn optimize for massive consumer-electronics volume, Celestica made a very different choice: go after complex, high-margin niches that are too small to excite the volume monsters but too hard for smaller players to execute consistently. The decision to exit lower-margin programs—including the phased Cisco departure—fits that pattern. It’s a strategy built around being more specialized, not more commoditized.

Porter's 5 Forces Analysis:

Supplier Power (Moderate to High): Celestica is still exposed to the same physics as everyone else: if you need chips from Broadcom or Nvidia, you live with their lead times and allocation decisions. What helps is execution—longstanding relationships, planning discipline, and inventory intelligence that can soften the worst of supply shocks. It doesn’t eliminate supplier power, but it can make Celestica a more reliable partner than peers when the supply chain gets tight.

Buyer Power (Mixed): Hyperscalers have enormous negotiating leverage, and customer concentration is the price of playing in this arena. In Q3 2025, three hyperscaler customers represented 59% of revenue (30%, 15%, and 14%). That concentration cuts both ways. On one hand, it signals deep entrenchment—Celestica is doing work important enough to be scaled hard. On the other, it exposes the company to capex swings, pricing pressure, and customer-specific demand volatility. The relationship may evolve from vendor to partner, but the bargaining power imbalance never fully disappears.

Threat of Substitutes (Low): There isn’t a shortcut around this kind of hardware. You can’t 3D print a hyperscale switch. When the system requires optical components, thermal considerations, software integration, and high-speed electrical interfaces, the substitute isn’t “something else.” It’s usually “a different supplier who can do the same thing,” which is a very different competitive dynamic.

Threat of New Entrants (Low to Moderate): In regulated markets like medical technology and aerospace, barriers are crushing—certifications and qualification cycles alone can take years. Cloud infrastructure is more fluid, and a well-funded newcomer can emerge in a narrow niche. But competing at scale, across design, manufacturing, supply chain, and support, is a taller order. It’s not just an engineering problem; it’s an execution and trust problem.

Industry Rivalry (High but Manageable): Celestica competes with serious players—Jabil, Flex, Foxconn, Sanmina—and the industry remains intensely competitive. The difference is that rivalry looks different at the high end. The fight isn’t only over price. It’s over who can co-design, deliver reliably, ramp fast, and support the platform over time. Celestica’s strategy is to stay on the capability axis where fewer competitors can play.

The Customer Lifecycle Management Strategy:

This is where Mionis’s private equity instincts show up most clearly. Celestica is effectively maximizing “lifecycle value”: win the customer at the design phase (higher margin), stay with them through the volume phase (sustainable margin), and keep the relationship through aftermarket services (recurring revenue). That’s a sharp break from the old world of chasing one-off builds. Instead, the goal is to embed into a customer’s roadmap and become hard to unwind.

For investors tracking whether this is working, two KPIs are especially telling:

KPI 1: HPS Revenue as a Percentage of Total Revenue — Currently at 44%. This is the simplest read on whether Celestica is continuing to shift toward the higher-margin, design-centric platform business. Management has said HPS should keep outgrowing the base.

KPI 2: CCS Segment Operating Margin — Currently at 8.3%. This is the profitability scoreboard for the cloud and communications engine. Moving from roughly 5% to above 8% over the last few years is what mix improvement and operating leverage look like when they’re actually taking hold.

IX. Bear vs. Bull & Future Outlook

The Bull Case:

The bull story starts with a simple claim: AI infrastructure is still early. The hyperscalers are still guiding to big capital spending, and the gating factor in deploying AI isn’t just GPUs—it’s everything wrapped around them. Networking, storage, power delivery, rack integration, thermal management. The unsexy parts that determine whether the GPUs run hot and idle, or run flat-out.

That’s the world Celestica has been building toward: networking and custom AI/ML compute infrastructure, with big ramps in 800G and the early innings of 1.6T programs. To support those ramps, the company has been leaning hard into investment—more R&D, more engineering headcount (over 1,100 design engineers today, with plans to add several hundred more), and a software organization of roughly 400 engineers. It’s also expanding capacity, including in Texas and Thailand, to meet customer demand through 2027 and 2028. Management expects R&D to rise sharply in 2026, on the order of 50%, as it pushes further up the value chain.

Bulls also argue the margin story isn’t a temporary wind at Celestica’s back. They see the shift toward HPS as structural: more design content, more software, more platform ownership, and more stickiness. And even after the stock’s run, they argue the valuation still looks more like “industrial manufacturer” than “critical AI infrastructure enabler.”

The stock performance is undeniable. Since the end of 2022, Celestica’s share price has climbed about 540%. Over the last five years, it’s up roughly 950%. The bullish interpretation is that the move isn’t speculative froth—it’s the market finally pricing the company as what it has become, not what it used to be.

The Bear Case:

The bear case begins with the oldest rule in this business: it’s still hardware, and hardware is cyclical.

If hyperscalers pull back on capex—because of a recession, a shift in AI priorities, or simply because growth slows—Celestica will feel it quickly. The company’s own disclosures make the exposure clear. In Q3 2025, three hyperscaler customers accounted for 59% of revenue (30%, 15%, and 14%). That kind of concentration can be a sign of deep entrenchment and real switching costs. It can also be a single-point-of-failure risk, and it gives customers leverage on pricing and terms.

Which leads to the second bear point: customer concentration hasn’t gone away. When nearly 60% of revenue comes from three customers, losing even one would be a body blow.

Third, skeptics question how durable the JDM advantage really is over a full cycle. If hyperscalers decide to bring more design work in-house, does Celestica keep its seat at the table? And can it fend off Asian ODMs that are climbing the value chain and looking for exactly this kind of higher-margin platform work?

Material Risks and Overhangs:

Geopolitics is the ever-present background risk. Celestica has diversified beyond China, but trade tensions can still disrupt supply chains, add friction, or increase costs.

And then there are the operational risks that come with scale and concentration: replacing revenue from completed, lost, or non-renewed programs; managing customer disengagements; and operating through uncertain market, political, and economic conditions tied to a global footprint. Celestica also discloses in its SEC filings that three customers each represent more than 10% of revenue, and together make up the majority of the CCS segment’s business.

What to Watch:

Near term, the adoption curve for 800G and 1.6T switching will do a lot to determine growth rates. In parallel, liquid cooling integration will only become more important as rack power densities keep rising.

And if you’re looking for balance in the story, watch ATS. Aerospace, medical technology, and industrial programs won’t grow like hyperscale cloud in a boom, but they can provide diversification and steadier demand if cloud spending ever decelerates.

X. Conclusion & Grading the Transformation

Celestica’s story is one of the more remarkable turnarounds in tech hardware history—and it played out mostly in the background. While the market fixated on software names and chip designers, a Canadian company long dismissed as “just a contract manufacturer” quietly rebuilt itself into something far more valuable: a critical infrastructure partner helping hyperscalers wire up the AI era.

The arc runs across three decades: IBM spin-off, telecom boom, telecom bust, BlackBerry dependence, years in the commodity trap—and then a hard pivot into engineering-led cloud hardware. Each chapter left a scar, and each scar became a lesson. The 2001 crash taught the danger of living on a few customers. The BlackBerry unwind proved it wasn’t a one-time mistake. And the long stretch of low margins made the underlying truth unavoidable: pure manufacturing scale, on its own, is a race you don’t win for long.

What Rob Mionis and his team did after he arrived in 2015 was accept that survival meant becoming a different company. Not a bigger contract manufacturer—a smarter, more design-centric one. Not cheaper—more essential. The decision to walk away from major, lower-return work—including the phased exit of roughly $750 million in annual Cisco revenue—wasn’t just financial discipline. It was a declaration of what Celestica would, and would not, be.

As Celestica’s share price surged, Mionis—who had guided the turnaround since 2015—sold a substantial amount of his share holdings, and other executives sold shares as well. Insider sales can be a normal part of turning equity compensation into cash, but it’s still the kind of signal investors tend to track, especially after a big run.

The AI supercycle provided the tailwind. But Celestica didn’t throw up a sail at the last minute—it built the ship before the wind arrived. By the time hyperscalers began accelerating AI infrastructure spend, Celestica already had the engineering muscle, the platform strategy, and the customer trust to capture the moment.

In a gold rush, everyone talks about selling shovels. But the better business is designing the shovel—then becoming the partner your customers can’t dig without.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music