Ciena: The Architects of the Infinite Loop

I. Introduction: The Internet's Nervous System

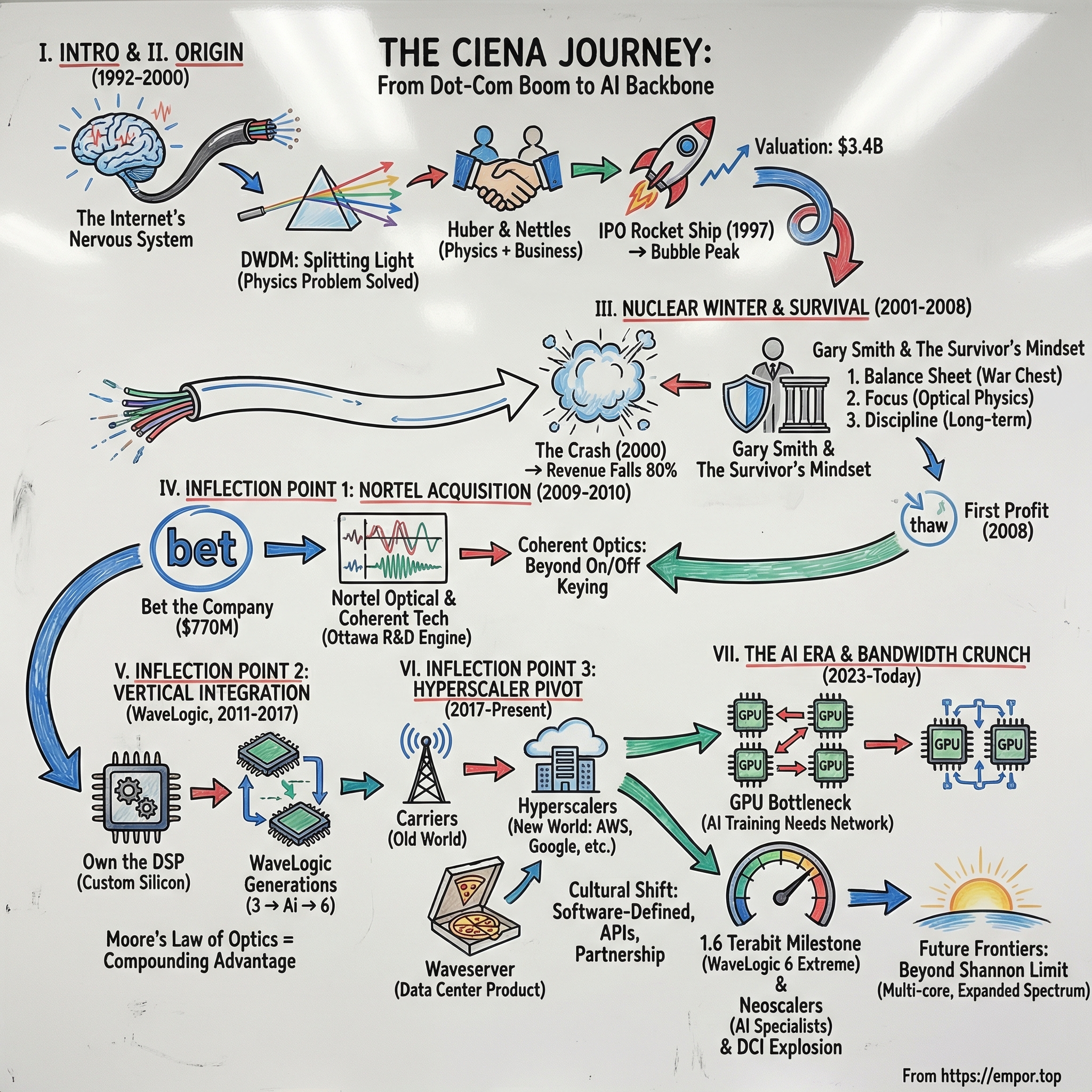

Right now, somewhere beneath your feet, photons are tearing through hair-thin strands of glass at roughly 186,000 miles per second. That Netflix stream you just started, the Zoom call your colleague is on, the ChatGPT prompt you fired off a moment ago—most of it is traveling as pulses of light through fiber. And there’s a very good chance those photons are being guided, amplified, and cleaned up by equipment from a company most people have never heard of: Ciena.

Think of the internet like a human body. Apps and websites are the thoughts—the part you notice. Data centers are the organs, doing the work. But the thing that makes the whole organism function is the wiring in between: the nervous system. That’s where Ciena lives. They build the infrastructure that moves signals across cities, across countries, and across oceans—fast, reliably, and at staggering scale.

Calling Ciena a “telecom equipment company” is technically true, but it misses the point. A closer description is “arms dealer for the bandwidth wars.” Ciena Corporation is an American optical networking systems and software company, and it’s a critical player in optical connectivity. Every time a hyperscaler like Amazon, Google, or Microsoft needs to move massive volumes of data between data centers—and they do that nonstop—Ciena’s gear is often the machinery making it possible.

Their stock chart tells you this isn’t a smooth, Silicon Valley-style ascent. In the late 1990s, Ciena was a classic dot-com-era rocket ship: a company that went from niche to near-mythic, then got obliterated when the telecom bubble popped. In the crash, annual sales fell from $1.6 billion to about $300 million. For a business that sells into carrier spending cycles, that kind of drop doesn’t just hurt—it threatens existence.

And yet, decades later, they’re still here—and very much in the game. In the fourth quarter of fiscal 2025, Ciena posted $1.35 billion in revenue. For the full year, revenue was $4.77 billion, up 19 percent year-over-year. And looking ahead to fiscal 2026, the company forecast revenue between $5.7 billion and $6.1 billion.

So this is the story: how a company gets caught in the blast radius of the biggest bubble in modern finance, survives the nuclear winter that follows, and patiently rebuilds into something essential. It’s a story about physics as a competitive advantage, engineering as a moat, and strategy measured in decades. And it’s about why, in an AI era defined by machines talking to machines at unimaginable scale, Ciena might be one of the most important technology companies you’ve barely thought about.

II. Origin Story: Splitting Light (1992–2000)

The Physics Problem No One Could Solve

In the early 1990s, the world was quietly running out of internet highway. Fiber optics had already rewritten the rules of telecommunications—glass strands could carry far more data than copper, and light didn’t fade the way electrical signals did over long distances. But there was a catch: a single fiber, in practice, carried a single stream. It was like installing a sixteen-lane superhighway and then letting only one car on it.

The idea to fix this had been sitting in the scientific literature for years. Light isn’t one thing; it’s a spectrum. Different colors are different wavelengths. If you could split light into separate wavelengths, send data on each one, and then recombine them at the other end, you could turn one fiber into many parallel channels—multiple “lanes,” all at once. The concept was called Wavelength Division Multiplexing, or WDM.

The problem was that “in theory” and “in the field” are two different universes. Precisely separating, stabilizing, and recombining those wavelengths with telecom-grade reliability was brutally hard. In the early ’90s, it was mostly a lab trick. Plenty of teams were chasing it, but nobody had made it commercially real.

That’s where David Huber came in.

It was the fall of 1992. The World Wide Web hadn’t yet become the thing it would soon become. But the company that eventually became Ciena was already taking shape, sparked by Huber—a former General Instruments engineer—who saw a way to help cable companies squeeze more television channels through their systems.

That year, he founded a company called HydraLite. The name was a clue: one light source, many “heads,” many streams. On November 8, 1992, HydraLite’s incorporation paperwork was filed in Delaware.

The PhD Who Made It Real

Huber had the technical vision. What he needed was someone who could translate physics into a product, and a product into a business.

That person was Patrick Nettles.

In late 1993, Huber met Nettles, a telecom veteran with an unusual profile: a seasoned operator who also had a Ph.D. in particle physics. Nettles joined in early 1994, becoming the company’s first CEO in February. He could speak both languages—the lab and the boardroom—which mattered because the product they were trying to will into existence lived right at that intersection.

One of Nettles’ first big calls reshaped the company. He convinced Huber to stop aiming at cable TV and go where the money—and the pain—really was: long-distance telephone carriers. Those networks were hitting capacity walls, and they were desperate for a way out that didn’t involve digging up the planet and laying more fiber.

As the team formed around that mission, the early core expanded. Over the next year and a half, Larry Huang and Steve Chaddick joined Huber and Nettles, forming the founding group. The company adopted a new name—Ciena—and narrowed its objective: bring Dense Wavelength Division Multiplexing, DWDM, into the long-haul fiber networks of major U.S. carriers.

Even the naming story has a startup scrappiness to it. Nettles later said, “I was in the shower and I thought of Ciena… I wrote it on the board. At the end of the day it had four or five circles around it.”

The “Pot of Gold” Pitch

Of course, vision doesn’t ship hardware. They needed capital.

Huber hired William K. Woodruff & Co. to take the pitch to venture firm Sevin Rosen. In November 1993, the idea was presented to John Bayless, and by April 1994 Sevin Rosen invested $1.25 million.

When Larry Huang came aboard to lead sales, he did something simple that told everyone exactly what they had. He called a senior contact at Sprint and described, at a high level, what this DWDM approach could do. The response wasn’t a polite “interesting.” It was: if you can actually pull that off, “it would be like me walking out of my office and finding a pot of gold on my secretary’s desk.” Huang joined the next day.

More funding followed. Ciena raised $40 million in venture capital financing from Charles River Ventures, Japan Associated Finance Co., Star Ventures, and Vanguard Venture Partners.

Underneath the fundraising and the storytelling was a brutally difficult engineering task. WDM, at its core, is a method of using multiple light wavelengths to carry multiple signals down the same fiber. DWDM is the “dense” version: tighter spacing between wavelengths, more channels per fiber, and much more complexity to build and operate.

A useful mental model is a rainbow. Split white light into distinct colors, and each color can carry its own data stream. Ciena’s breakthrough wasn’t merely splitting light—it was doing it with enough precision and stability to run real carrier networks. Early on, that meant controlling up to 16 narrow wavelength bands and combining them onto a single fiber strand, with room to scale to many more.

The Product That Changed Everything

Ciena’s real debut came on March 28, 1996, when it introduced its first product: the MultiWave 1600 Transmission System. It was the world’s first commercially available 16-channel DWDM platform, capable of delivering 40 Gbps of total capacity on a single fiber pair over distances up to 600 kilometers.

The economics were the killer feature. As Huber, then the company’s Chief Technology Officer, put it: “a single Ciena optical amplifier can replace sixteen electronic regenerators,” dramatically simplifying operations.

And the timing was immaculate. The commercial internet was taking off. Netscape’s August 1995 IPO had lit the match for the dot-com boom. Internet traffic was surging. Carriers like Sprint and MCI had to expand capacity fast, but laying new fiber was expensive, slow, and politically messy.

Ciena’s first products went to Sprint in May 1996. In its first year of sales, the company recorded $195 million in revenue—then the highest first-year sales ever recorded by a startup.

That’s not just “good for a startup.” That’s the market screaming, finally, someone solved the problem.

The IPO Rocket Ship

With demand roaring, Ciena went public on NASDAQ in February 1997. The IPO valued the company at $3.4 billion.

For the fiscal year ending in October 1997, Ciena generated about $370 million in revenue and $110 million in profits. The company was printing money, and the stock market treated it like the next inevitable giant.

By the peak of the bubble, Ciena was priced as if it were a future monopolist of bandwidth. The industry’s core belief sounded reasonable in the moment: bandwidth demand would keep doubling every three to four months. If that were true, then a company that could multiply fiber capacity without laying new cable wasn’t just valuable—it was essential.

But that assumption—doubling forever—was about to collide with reality.

III. The Nuclear Winter & The Survivor's Mindset (2001–2008)

The Crash

The dot-com bubble hit its high-water mark on Friday, March 10, 2000, when the NASDAQ Composite closed at 5,048.62. Then the floor gave out. After years of euphoria, the index unraveled, eventually falling roughly 78% from its peak by October 2002—erasing the gains that had defined the bubble years.

For Ciena, this wasn’t a bad year. It was a near-death experience.

In fiscal 2001, revenue still climbed—up 87% to $1.6 billion for the year ending October 31. But the income statement told the real story: a net loss of $1.8 billion. Another massive loss followed in 2002.

And then the demand cliff arrived. Over the course of the telecom crash, Ciena’s annual sales fell from $1.6 billion to roughly $300 million—an 80% collapse. The stock, which had been priced like the inevitable monopolist of bandwidth, cratered right along with the industry.

In some ways, the telecom bust was even harsher than the dot-com shakeout in software. When a web startup died, it left behind code and a few racks of servers. When a telecom carrier died, it left behind infrastructure—miles of fiber optic cable already buried in the ground. The crash created a glut of “dark fiber,” and for years carriers didn’t need to buy new capacity. They just lit what they already owned.

Ciena wasn’t alone in the wreckage. The giants were falling too—often harder. Nortel, the Canadian titan once valued at over $250 billion, began a slide that would end in bankruptcy. Lucent, spun out of AT&T and Bell Labs, saw its stock implode and was ultimately sold to Alcatel. Marconi collapsed altogether.

This was the nuclear winter: too much fiber, too little spending, and a market that no longer believed the old growth stories.

Enter Gary Smith

In 2001, Ciena made the kind of leadership change companies make when the mission shifts from “win” to “survive.” Gary Smith replaced Patrick Nettles as CEO, and Nettles moved to executive chairman.

Smith had joined Ciena in 1997. By May 2001, he was president and CEO—taking the helm at the worst possible moment, just as the industry was imploding.

He was also a different archetype than Nettles. Where Nettles was the physicist-entrepreneur, Smith was a sales-and-operations executive. Before becoming CEO, he’d been Ciena’s chief operating officer and head of sales. Prior to Ciena, he led sales and marketing at Intelsat and held senior roles at several European communications companies, including Cray Communications Group and Tricom Communications PLC.

His approach hardened into a simple cultural formula: people first, plus ruthless operational discipline, anchored by “best-of-breed technology.” In Ciena’s own telling, Smith’s elevation during the 2001 downturn—and the decision to stick to those core values—helped transform the company from a niche player into a diversified global leader.

Smith remained CEO more than two decades later, making him one of the longest-tenured chief executives not just in telecom, but across technology.

Survival Mode

The early 2000s at Ciena weren’t about expansion. They were about staying alive long enough for the world to need bandwidth again.

In 2001, Ciena raised $1.52 billion by selling 11 million shares, plus another $600 million through convertible bonds. That war chest mattered. It bought time—years of it—in an industry where customers had stopped spending and competitors were dropping like flies.

Then Ciena did something that looks strange at first glance: it started buying.

Between 1997 and 2004, the company acquired 11 businesses. And between 2001 and 2004—right in the heart of the downturn—it bought five networking technology companies for more than $2 billion.

Why would a company in a collapsing market go shopping? Because downturns don’t just destroy demand. They also put teams, patents, and product lines on the auction block. When competitors are forced to sell, the assets that were unaffordable in boom times can suddenly be bought at distressed prices. Ciena was using the winter to accumulate capabilities it believed would matter when spring returned.

The financial pain was still brutal. In 2002, Ciena reported $361.1 million in sales and a $1.59 billion loss, with roughly 3,500 employees. By 2003, it was the fourth-largest producer of fiber optic equipment in the U.S.—still standing, but very much fighting for oxygen.

The Philosophy That Mattered

So why did Ciena survive when some of the biggest names in telecom didn’t?

It wasn’t one magic move. It was a set of survival instincts that became a corporate identity.

First: the balance sheet. The 2001 capital raise gave Ciena runway—enough cushion to endure an industry depression that lasted years, not quarters.

Second: focus. While others chased the next promising category—wireless, switching, anything that might restart growth—Ciena stayed centered on what it believed was non-negotiable: optical performance. In other words, the physics.

Third: discipline. Smith’s leadership emphasized long-term sustainability over short-term bragging rights—keeping costs under control, avoiding speculative bets, and building a company that could outlast the cycle rather than pretend the cycle didn’t exist.

The recovery was slow, but it was real. Since the first full year of Smith’s tenure, revenue grew from $361 million in fiscal 2002 to $2.1 billion in fiscal 2013.

And by 2008, you could finally see the thaw. Ciena generated $902 million in revenue and reported a profit of $39 million—its first substantial profit in years, and a signal that it had made it through the storm.

But surviving the winter wasn’t the same as winning the future.

What came next would define Ciena far more than the years it spent simply refusing to die.

IV. Inflection Point 1: The Nortel Acquisition (2009–2010)

The Carcass of a Giant

In January 2009, Nortel Networks—once Canada’s most valuable company, at its peak worth more than $250 billion—filed for bankruptcy protection. The titan of Canadian telecom wasn’t just shrinking. It was being dismantled and sold off, piece by piece.

For Ciena, this was the kind of moment that almost never appears in real life: a once-in-a-generation chance to buy world-class assets at distress prices. It was also the kind of moment that can get you killed if you get it wrong.

Between 2009 and 2010, Ciena acquired Nortel’s optical technology and Carrier Ethernet division for about $770 million. Nortel’s Metro Ethernet Networks business brought next-generation optical transmission gear—and a customer base of more than 1,000 customers across 65 countries.

One analyst summed up the reality bluntly: “Ciena absolutely must make this acquisition work. It is a ‘bet the company’ move for them.”

Why This Wasn’t Just About Revenue

From the outside, most tech acquisitions look like spreadsheet logic: buy revenue, cut costs, gain scale. But the Nortel deal wasn’t primarily about customer lists or product SKUs. It was about buying the future of optical networking.

On March 12, 2008, the industry’s first coherent 40G optical transport solution was unveiled, along with the announcement of its first two customers. By late 2009, coherent technology was powering the first live 100G coherent network—an 893-kilometer link between Paris and Frankfurt on Verizon’s network.

That coherent optical breakthrough—arguably the biggest leap in optical networking since DWDM—came out of Nortel. So when Ciena went after Nortel’s optical division, it wasn’t just buying a business. It was buying the engineers and the intellectual property behind the next standard wave of bandwidth.

Dino DiPerna, along with many of his team, joined Ciena through the 2010 Nortel acquisition. He later became Ciena’s Vice President of Packet-Optical Platforms R&D, based in Ottawa.

To see why that mattered, you have to understand the problem coherent optics solved.

Coherent Optics Explained

Traditional fiber optic communication is straightforward: you blink a laser. Light on is a “1.” Light off is a “0.” It’s basically Morse code at the speed of light.

But that method—often described as intensity modulation—hits a wall. You’re essentially squeezing one bit of information out of each pulse. When your entire business is pushing more and more data through the same buried glass, that limitation becomes existential.

Coherent optics changes the game. Instead of just turning light on and off, it uses sophisticated modulation to encode information into the amplitude and phase of the light, and it transmits across two polarizations. In plain English: you stop treating light like a simple flashlight, and start treating it like a rich signal you can sculpt in multiple dimensions.

If basic optics is flicking a flashlight on and off, coherent optics is being able to vary brightness (amplitude), shift timing (phase), and use polarization—at the same time. The payoff is that each “symbol” can carry far more information: not one bit per symbol, but 2, 4, 8, 16 bits, and beyond, depending on the modulation method.

The result is a massive jump in transmission capacity versus conventional on-off keying, and it became foundational to keeping pace with the speeds demanded by cloud and hyperscale data center interconnects—400G, 800G, and the generations that followed.

The Integration Challenge

On March 19, 2010, Nortel completed the sale of substantially all the assets of its global Optical Networking and Carrier Ethernet business to Ciena.

The path there was anything but quiet. After a weekend-long auction that began Friday and ended Sunday, Ciena beat Nokia Siemens Networks in a two-horse race to buy Nortel’s Metro Ethernet Networks division. Ciena’s winning bid was $769 million, made up of $530 million in cash plus convertible notes valued at $239 million.

And then came the hard part: integration.

This deal didn’t just add a product line. It more than doubled Ciena’s size and reshaped where the company lived. The acquired business included roughly 1,400 employees in Canada—about 1,125 in Ottawa and 250 in Montreal. Years later, in 2017, Ciena’s 1,600 Ottawa personnel were consolidated into a new campus in Kanata, Ontario.

Those Ottawa teams—many with Nortel roots—ended up doing something wildly disproportionate: less than 30 percent of Ciena’s workforce, but responsible for about half of the company’s R&D. In a business where the moat is physics and implementation detail, that concentration matters. Ottawa became the optical engine room.

The Nortel acquisition moved Ciena from a survivor with solid technology into a true heavyweight—capable of going toe-to-toe with global giants like Huawei and Nokia. More importantly, it put Ciena in control of coherent optical technology that would define high-speed transport for the next era of networking.

V. Inflection Point 2: The Vertical Integration of WaveLogic (2011–2017)

The Chip Decision

After Nortel, Ciena had the coherent optics team. Now it had to decide what kind of company it wanted to be.

Most optical vendors bought the critical components—the parts that actually “think”—from specialist suppliers. Ciena could’ve done the same. Keep assembling systems, let someone else build the brains, and compete on packaging, pricing, and sales execution.

Or it could take the hard road: design its own custom silicon.

That’s the fork in the road Ciena faced. And it’s the kind of decision that, years later, Apple would make famous in consumer tech: stop relying on generic processors and build chips purpose-built for your own architecture. In Ciena’s world, that chip was the Digital Signal Processor, or DSP—the core engine that creates coherent signals on the transmit side and reconstructs them on the receive side.

Ciena chose vertical integration.

“That first chip was the birth of what we now call WaveLogic, it was the first generation of DSP-assisted electro-optics,” said DiPerna.

WaveLogic became Ciena’s proprietary advantage—the part competitors couldn’t simply source off a shelf. And over time, Ciena doubled down. WaveLogic Ai pushed the strategy further, integrating the DSP and optics more tightly and extending into the control plane. The company continued to avoid relying on outside suppliers like Acacia, NTT Electronics, or Clariphy, even as the broader industry experimented with more commodity hardware and disaggregated networks.

How WaveLogic Works

To understand why this mattered, you need to understand what the DSP actually does in a coherent optical system.

Coherent transmission isn’t just blinking a laser on and off. You’re encoding information into multiple dimensions of light, and then trying to recover it after that light has been battered by real-world fiber.

That’s the DSP’s job. It generates incredibly precise waveforms at the transmitter, then, at the receiver, it uses math to extract the original data—while compensating for distortions accumulated across the journey.

Those distortions are not edge cases; they’re the default. Different wavelengths travel at slightly different speeds through fiber, creating chromatic dispersion. The polarization of light shifts as it goes, creating polarization mode dispersion. Noise and other impairments pile on. Historically, carriers tried to manage some of this with bulky optical modules in the line system. With DSP-based compensation, much of that work moved into digital signal processing, enabling robust performance over old and new fiber alike.

The bigger picture is flexibility. Coherent optics, paired with a strong DSP, lets operators choose different baud rates and modulation formats to trade off reach versus capacity. That programmability becomes a strategic advantage when your network isn’t a static set of pipes, but a living system that has to adapt to demand.

The Moore's Law of Optics

Once Ciena committed to owning the DSP, it could run its own version of Moore’s Law—not by laying more fiber, but by getting smarter at the ends of the fiber.

WaveLogic moved through multiple generations, each one pushing the ceiling higher.

In 2013, Ciena unveiled WaveLogic 3, featuring the industry’s first integrated digital signal processing in the transmitter.

WaveLogic Ai followed WaveLogic 3, which was announced in 2012, along with incremental iterations—Extreme and Nano—announced in 2015.

Then the strategy kept compounding. By 2023, Ciena unveiled WaveLogic 6, another industry first in coherent optics. WaveLogic 6 was optimized for high-capacity transport: up to 1.6Tb/s single-carrier wavelengths for metro ROADM deployments, 800Gb/s over the longest links, and energy-efficient 800G pluggables across 1000km distances.

WaveLogic 6 was also the first announced coherent DSP implemented on a 3nm CMOS process. Competitors were shipping—or preparing to ship—5nm coherent DSPs. Ciena skipped 5nm entirely and shipped WaveLogic 6 Extreme coherent modems in the first half of 2024.

That move to 3nm gave Ciena a meaningful performance edge. In optical networking terms, it was a leapfrog moment: not a tweak, but a generational jump that would be painful for rivals to match quickly.

The Cumulative Advantage

Ciena has long positioned its innovation around a simple customer promise: more capacity with less—less power, less space, and less cost.

Since WaveLogic’s introduction in 2008, it delivered roughly 20 times more capacity over fiber and more than an 85% reduction in watts per gigabit per second for customers.

That’s what vertical integration buys you: not one breakthrough, but a compounding series of advantages that stack up over time.

And the economic impact is hard to overstate. Each WaveLogic generation let operators expand the capacity of fiber they already owned, without the slow, expensive, politically messy work of laying more cable—especially under oceans, where new builds can run into the billions.

This is the moat in deep tech. It’s not just patents or branding. It’s years of accumulated engineering effort, massive R&D expense, and the kind of hard-won implementation knowledge you only get by shipping at scale. Ciena shipped more than 60,000 WaveLogic 5 Extreme DSPs to over 200 customers. By the time competitors react, Ciena is already working on the next generation.

And that set up the next shift: not just better optics, but a new kind of customer—and a new kind of network.

VI. Inflection Point 3: The Hyperscaler Pivot (2017–Present)

The Customer Revolution

For Ciena’s first two decades, “customer” meant one thing: telecom carriers. AT&T, Verizon, Deutsche Telekom, BT—the incumbent operators that owned the fiber networks connecting cities and countries. They were the center of the industry, and they were Ciena’s center of gravity.

Then, starting around 2015, the ground shifted.

A new class of customer showed up with a very different posture: the hyperscalers—AWS, Google, Microsoft, Meta. They weren’t just renting capacity from carriers anymore. They were building their own networks: private fiber routes, metro rings, and even subsea cables spanning oceans. The driver was simple and relentless: their data centers needed to behave like one giant, distributed computer, which meant moving staggering volumes of traffic between facilities.

And they were scaling fast. Over 70 new data centers and 35 new cloud regions were expected in 2025 alone.

This changed the market. Carriers are deliberate, process-heavy, and often take years to make large purchasing decisions. Hyperscalers move at software speed. They test gear in their own labs, they deploy at massive volume, and they demand the best performance they can get—because for them, bandwidth isn’t a nice-to-have. It’s the product.

Waveserver: The Data Center Product

Ciena saw where the puck was going and built for it.

It introduced Waveserver, a compact, purpose-built platform aimed at metro data center interconnect—moving huge amounts of traffic between data centers quickly, efficiently, and at scale. It came in a one rack unit form factor, designed to stack, cable, and manage more like a server than a classic piece of telecom gear.

Rick Dodd, Ciena’s SVP of Portfolio Marketing, described it in plain terms: “In a pizza box format, it can do 400 gigabits on the line side, 400 gigabits in terms of clients, up to 20 terabits on a fiber – more capacity than anybody, more density than anybody.”

That “pizza box” framing matters. Traditional telecom platforms were built for dusty central offices and multi-decade lifecycles. Waveserver was built for the web-scale rhythm of a data center: fast ordering, fast installation, modular growth, and management that looks and feels like IT.

The Cultural Shift

Selling into that world required Ciena to change how it built and how it sold.

Carriers buy through long RFP cycles and committee decisions. Hyperscalers want hands-on testing, quick iteration, and a short path from “this works” to “ship it.” They also care intensely about programmability—treating the network as software, controlled through APIs, not as a box configured by hand.

That pushed Ciena beyond “great optics in a chassis” into software-defined networking expectations: open APIs, modern data models, streaming telemetry, declarative configuration, and automation-friendly platform design. It wasn’t just a product tweak. It was a shift in mindset—from telecom interfaces and telecom timelines to data center operations and software workflows.

The Partnership Model

As Ciena pushed into hyperscalers, the relationships looked less like vendor contracts and more like joint engineering.

With Microsoft, for example, Microsoft contributes its tiered optical business continuity and disaster recovery architecture, while Ciena provides the underlying transport technologies—the 6500 Packet-Optical Platform, the 6500 Reconfigurable Line System, and the Waveserver family.

With Meta, Ciena collaborated on a new approach to the growing complexity of out-of-band management networks. Ciena’s data center out-of-band management solution, developed closely with Meta, reflected a shared goal: simplify and modernize out-of-band infrastructure at hyperscale.

These weren’t just logos on a slide. They were proof that Ciena could do the hardest part of the hyperscaler pivot: earn a seat at the table where the network is designed, not just purchased.

VII. The Current Era: AI & The Bandwidth Crunch (2023–Today)

The GPU Bottleneck

Training large language models like GPT-4 or Claude requires something that feels almost counterintuitive: it’s not one supercomputer doing the work, it’s thousands of GPUs trying to behave like one. That only works if those GPUs can talk to each other constantly—sharing gradients, activations, and parameters with minimal delay.

And that’s where the pain shows up. Modern AI training inside data centers depends on short-reach networks that are both extremely high bandwidth and extremely low latency—running at 400Gb/s and 800Gb/s today, with 1.6Tb/s and beyond coming into view. Just as the industry has started building custom AI-focused CPUs and GPUs, it has also had to innovate the network fabric that feeds them and ties them together.

Because the real bottleneck often isn’t compute. It’s the network connecting the compute. A 10,000-GPU cluster is only as powerful as its ability to exchange information. If the network can’t keep up, those expensive GPUs spend time waiting—idle, stranded, and burning money.

Ciena CEO Gary Smith has been blunt about what’s changing in how customers think about AI infrastructure spending. Investment is starting to shift toward the networks needed to support AI, not just the chips and the power to run them. As he put it: “There’s no point in investing in these massive amounts of GPUs if we’re going to strand it because we didn’t invest in the network.”

The Data Center Interconnect Explosion

It’s not just that data centers need faster plumbing inside the building. They need it between buildings, too.

More than half of respondents in one set of survey results believe AI workloads will place the biggest demand on data center interconnect infrastructure over the next two to three years, surpassing cloud computing and big data analytics. And to meet that pull, 43% of new data center facilities are expected to be dedicated to AI workloads.

A Ciena survey found data center experts anticipate at least a sixfold increase in DCI bandwidth demand over the next five years.

This is the key shift: the internet used to be mostly about connecting data centers to users. AI is making it just as much about connecting data centers to each other—because training clusters can span multiple facilities, and the data has to move between them at speeds measured in terabits per second.

The 1.6 Terabit Milestone

By 2025, 1.6Tb/s stopped being a slide-deck milestone and became a commercial reality.

WaveLogic 6 Extreme first became available in late 2024, but 2025 is when deployments accelerated—and when operators started pushing speed and distance records that made 1.6Tb/s feel less like a lab demo and more like the new baseline for the most demanding parts of the network.

WaveLogic 6 Extreme is positioned as the first solution to deliver 1.6Tb/s-per-wavelength technology and ubiquitous unregenerated 800Gb/s connectivity across networks. Compared to the prior generation, it delivers double the capacity in the same footprint, a 50% reduction in power per bit, and a 15% increase in spectral efficiency.

To make 1.6Tb/s intuitive: that’s enough throughput to stream roughly 320,000 4K video streams at once—on a single wavelength of light. And DWDM doesn’t use one wavelength. It uses many. So one fiber pair can carry not just “a lot,” but tens of terabits per second.

The Neoscaler Opportunity

While hyperscalers have been the headline customers, another category has been rising fast: neoscalers.

These are AI specialists—AI model developers, GPU-as-a-service providers, and an expanding ecosystem of network operators building infrastructure for AI. They include cloud and edge service providers, plus data center and colocation providers. And as AI demand accelerates, they’re building highly scalable networks of their own to fuel growth.

It’s a customer category that barely existed five years ago. Companies like CoreWeave and Lambda Labs are assembling massive GPU clusters specifically for AI workloads—and the common requirement is the same: high-speed optical connectivity that can keep the whole system from choking on its own data movement.

The Financial Results

All of this shows up in Ciena’s results.

In the fourth quarter of fiscal 2025, Ciena posted $1.35 billion in revenue, up 20% year-over-year. For the full year, revenue was $4.77 billion, up 19%.

Gary Smith tied that performance directly to the expanding AI ecosystem: “We’re also seeing a significant addressable market opportunity in and around the data center. It is, I think, well understood that the cloud providers are investing heavily in data centers to deliver on the current and future promises of AI.”

Ciena also reported that revenue growth for data center opportunities was up threefold from 2024.

And for fiscal 2026, the company guided to revenue between $5.7 billion and $6.1 billion—implying roughly 20% to 28% growth off fiscal 2025.

VIII. The Playbook: Lessons from Ciena

Lesson 1: Deep Tech as Defensive Strategy

In a world where software advantages get copied fast, Ciena’s moat is rooted in something you can’t simply clone: the physics of light, and the decades of engineering required to bend it to your will. You can’t download coherent optical expertise from GitHub. You can’t hire a small team and catch up to generations of DSP development.

This is what Ciena has quietly done for years: assemble and sustain an R&D machine capable of turning hard science into shippable products that change what’s possible on fiber. It’s the kind of work that takes big, specialized teams—well over a hundred people pulling in the same direction—to produce a stack of innovations that don’t just improve a network, but reroute the whole industry.

And it’s expensive. Building a competitive coherent DSP takes years and costs hundreds of millions of dollars. Only a handful of companies in the world can afford that kind of sustained effort, which naturally turns the market into something close to an oligopoly: the leaders keep compounding, while smaller players struggle to keep up.

Lesson 2: Counter-Cyclical M&A

The Nortel acquisition is the textbook case for what counter-cyclical M&A looks like when it’s done right. When an industry cracks, talent and intellectual property that were untouchable in boom times suddenly hit the market at distressed prices. Ciena used its financial strength in the 2008–2010 window to buy capabilities that permanently reshaped the company.

The real insight is what they were actually buying. Ciena wasn’t chasing Nortel’s revenue line or its customer list. They were buying technology and the people who knew how to build it. That coherent optical team became a core engine of Ciena’s R&D for the next decade and beyond.

Lesson 3: Patience in Cyclical Industries

Telecom equipment is brutally cyclical. Carriers spend in waves, pause for years, then surge again—and the timing is rarely convenient. Ciena’s edge hasn’t been predicting every turn perfectly. It’s been surviving the downturns with discipline, while still investing enough to be ahead when demand comes back.

Gary Smith has been explicit that this mindset isn’t optional. Even as the company benefited from the AI-driven bandwidth buildout, he’s said he wants Ciena to stay locked on long-term goals, keep ambitions high, and avoid the one thing that kills companies in mature industries: complacency. “We have great perseverance, and we very much have a ‘challenge and disrupt’ mentality,” he said.

Lesson 4: Standards Participation

Ciena doesn’t just build to the standards. They help shape them.

The company is active in standards bodies like the OIF (Optical Internetworking Forum) and IEEE, which matters because standards don’t just ensure interoperability—they determine the playing field. When you help write the rules, you have a say in where the market is headed, and what “good enough” will mean.

That standards work keeps moving. At OFC 2025, OIF and its member companies showcased interoperability and next-gen optical building blocks—including 800ZR, 400ZR, OpenZR+, multi-span optics, and more—pushing performance, efficiency, and capacity toward the demands of future-oriented data centers.

IX. Analysis: 7 Powers & 5 Forces

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers

Cornered Resource: If you’re looking for the “special sauce” inside Ciena, it’s not a single patent or one product cycle. It’s a concentrated pool of optical physicists and DSP engineers—many with Nortel DNA—based in Ottawa. Roughly 1,600 people sit there, less than 30 percent of Ciena’s total workforce, yet they make up the company’s largest operational hub and deliver about half of its R&D. You can hire smart engineers. You can’t quickly recreate decades of coherent optics scar tissue and system-level know-how.

Scale Economies: This is a hardware business that behaves like a semiconductor business. A cutting-edge coherent DSP on a 3nm process can cost hundreds of millions of dollars to design, and that’s before you fund the hardware platform and the software that runs the control plane around it. Only companies with enough shipment volume can amortize those costs. Ciena benefits here because, as the largest pure-play coherent optical vendor in the West, it has the most volume to spread those R&D bets across.

Switching Costs: Optical networks aren’t plug-and-play like swapping productivity software. Once an operator has deployed Ciena transponders, switching vendors introduces real friction: retraining teams, changing sparing strategies, requalifying designs, and re-integrating network management tooling. It’s not an unbreakable lock-in, but it’s enough pain that customers usually don’t switch unless the performance or economics are meaningfully better.

Porter's Five Forces

Rivalry: Competition is intense, but it’s also concentrated. The global optical networking market is dominated by a small number of players, with Huawei, Ciena, and Nokia collectively holding more than half the market. The direction of travel is toward even more concentration as sub-scale competitors struggle and leaders pick up share.

Ciena is particularly strong in North America, where it holds nearly half the U.S. market, and it’s well positioned with cloud providers as demand rises for WaveLogic 6e and 400ZR/ZR+ solutions.

Geopolitics has also reshaped the playing field. Huawei has been banned from many Western markets, effectively removing what was arguably the most formidable competitor from Ciena’s core territories. Huawei held the highest global share at 33 percent, followed by Ciena at 19 percent, but much of Huawei’s position sits inside China—where Western vendors have limited access anyway.

Buyer Power: High. Ciena sells to some of the biggest buyers on earth—AT&T, Verizon, Microsoft, Google—and customer concentration gives them leverage. In fiscal Q4 2025, three customers each represented more than 10% of revenue, together accounting for 43.6% of the quarter.

But this power has a ceiling, because the buyers don’t have the option to stand still. Carriers and hyperscalers have to keep increasing capacity to stay competitive. Even if they push hard on price, they still need the upgrades.

Threat of New Entrants: Very low. The capital requirements, technical depth, and time-to-market are brutal. A credible new coherent optics entrant would need years of development and billions of dollars to get to parity—only to arrive in a market where incumbents are already shipping the next generation.

Threat of Substitutes: Low for core infrastructure. For long-distance, high-capacity transmission, there is no realistic substitute for fiber optics. Undersea cables carry 99% of global data traffic, and coherent optical technology is tailor-made for the long-range, high-throughput, high-reliability demands of that world. Wireless and satellite can complement fiber at the edge, but they can’t replace it in the backbone.

Supplier Power: Moderate. Ciena relies on semiconductor foundries for fabrication and on component suppliers for lasers and other optoelectronics. Moving to advanced nodes like 3nm creates concentration risk, particularly around TSMC. And in the current environment, the constraint is often supply, not demand. As Gary Smith put it: “For the foreseeable future, it's really just the ecosystem of supply to be able to meet these demands from an optical point of view. And we're working closely with our optical component partners to ramp and scale that up. But for the foreseeable future, we're still constrained basically by supply. This is not about demand.”

X. Epilogue: The Shannon Limit and Beyond

The Physics Wall

In 1948, Claude Shannon at Bell Labs proved something both elegant and unsettling: every communication channel has a maximum capacity. There’s a ceiling set by physics on how much information you can reliably push through a given medium. For optical fiber, that ceiling is often referred to as the Shannon Limit.

And the uncomfortable part is that modern coherent optical systems are already operating within about 1 to 2 dB of it. In other words, we’re no longer in the era where clever modulation alone can keep bailing us out. Ciena’s Brian Lavallée has been direct about what that means: the industry is getting close enough to the limit that you can feel it.

At first glance, that sounds like the end of the story. If the limit can’t be broken—and it can’t—then eventually the bandwidth curve should flatten.

But the industry’s response has been classic engineering pragmatism: if you can’t squeeze much more out of each hertz, go get more hertz. Or get more fibers. Or get more spatial paths.

That’s why the next chapter isn’t just “smarter modems.” It’s broader spectrum and more physical lanes.

One lever is spectrum expansion. By exploiting the L-band, operators can essentially double the available spectrum beyond the traditional C-band. Pair that with wider-band repeaters to make more of that spectrum usable, and you have a real step-function increase in capacity. Another lever is brute-force multiplication: more fiber pairs per submarine cable to increase total capacity, and eventually newer multi-core fibers in future wet plants.

The takeaway is subtle but crucial: even if raw bandwidth demand keeps doubling every two to three years, the Shannon Limit means future gains in transponder spectral efficiency will be incremental. So staying on the curve increasingly requires more spectrum, not just better math.

In fact, approaches like Super C plus Super L can push total fiber capacity beyond 100 Tb/s over shorter distances. Not because anyone “beat Shannon,” but because they found more room to operate.

The Future Frontiers

A few paths are emerging as the industry’s best bets:

Multi-core fiber: Instead of a single glass core, fibers with multiple parallel cores can multiply capacity without laying entirely new cables.

Expanded spectrum: Moving beyond just C-band into L-band, and potentially S-band, to double or even triple usable spectrum.

Space division multiplexing: Using multiple spatial modes within a single fiber, effectively creating more lanes inside the same strand.

And while the long-haul backbone gets the headlines, the next constraints are also showing up inside the data center. To push further there, Ciena announced the acquisition of Nubis Communications, whose high-bandwidth interconnect technologies complement Ciena’s portfolio and aim to unlock new levels of capacity and power efficiency for scale-up and scale-out data center applications driven by rapidly growing AI workloads.

The View From Here

Ciena ends up in a fitting place: right at the intersection of two unstoppable forces. On one side, the hard edge of physics—the Shannon Limit, the reality that you can’t negotiate with information theory. On the other, the relentless pull of demand—AI, cloud, video, and machines talking to machines, all insisting on more bandwidth.

The company that nearly died in the dot-com crash is now the dominant Western player in coherent optical networking, showing up precisely when bandwidth matters more than ever. As Gary Smith put it, “Our record fiscal fourth quarter and full-year performance reinforces our position as the global leader in high-speed connectivity with an expanding role in the AI ecosystem.”

In the end, the Ciena story is about patience, physics, and persistence. While the world fixated on software, Ciena kept compounding in a domain where progress is slower, harder, and far more defensible.

Because every ChatGPT query, every Netflix stream, every AI training run ultimately becomes light in glass. And at the ends of those fibers—where the signal has to be created, shaped, recovered, and made useful—there’s a very good chance Ciena is there, quietly keeping the modern world in motion.

Key Metrics for Investors

If you want a quick read on whether the Ciena flywheel is spinning, there are two metrics that tend to tell the story better than any single quarter:

1. WaveLogic generation adoption rate: Every WaveLogic generation is Ciena’s “new engine”—more capacity, better reach, better efficiency. The key question isn’t just whether WaveLogic 6 is good on paper. It’s how fast customers actually move to it. A strong adoption curve usually signals two things at once: Ciena is staying ahead technically, and the broader industry is in an upgrade cycle rather than a wait-and-see pause.

2. Cloud/hyperscaler revenue mix: For most of Ciena’s history, the center of gravity was carriers. Now the growth is increasingly driven by cloud providers building out networks for AI-era traffic patterns. Watching how much revenue comes from cloud and hyperscaler customers is a clean way to track whether Ciena is winning in the highest-growth part of the market—and how quickly its business is shifting away from the slower, more cyclical carrier world.

Further Reading

If you want to go deeper—either into the physics that makes modern fiber possible or the history of how we got here—these are great places to start:

- City of Light: The Story of Fiber Optics by Jeff Hecht — a clear, comprehensive history of how fiber optics went from lab curiosity to global backbone.

- The Information by James Gleick — a wide-angle tour of information theory, including Claude Shannon and the ideas that still define the limits of communication.

- Fiber: The Coming Tech Revolution by Susan Crawford — a look at fiber infrastructure as the foundational, often-invisible layer of modern connectivity.

And if you’re curious about what’s happening right now at the bleeding edge, the technical papers from OFC (the Optical Fiber Communications Conference) are where the industry shows its work—year by year, wavelength by wavelength.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music