Clear Channel Outdoor Holdings: From Radio Empire to Digital Billboard Giant

I. Introduction: The Billboard That Refused to Die

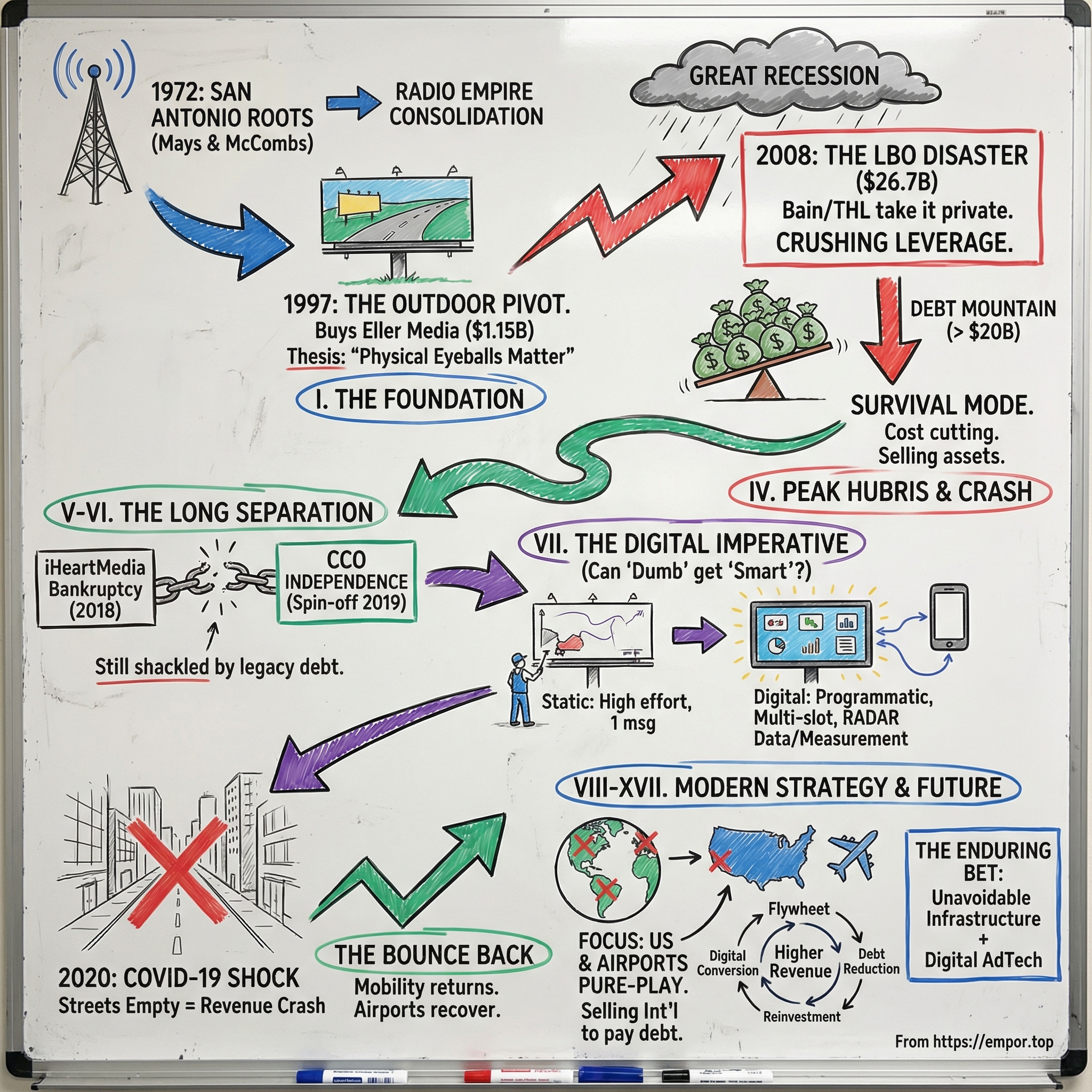

Picture a long, quiet stretch of Texas highway in 1997, somewhere between San Antonio and Houston. A single billboard breaks the horizon: a simple painted panel pitching a local steakhouse. To most drivers, it’s background noise. The kind of “dumb” piece of infrastructure you stop noticing the moment you pass it.

But that billboard was also a clue. Not about the steakhouse—about what was coming next.

That same year, Clear Channel Communications—then best known as a fast-growing radio broadcaster—bought Eller Media for $1.15 billion. On paper, it was an outdoor advertising acquisition. In reality, it was a thesis: that even as the internet began pulling attention onto screens, “eyeballs in physical space” would still matter. That there would always be places you couldn’t skip, scroll past, or ad-block.

What makes this story so compelling is how many times that thesis should have died.

It made it through a catastrophic leveraged buyout timed almost perfectly wrong. It made it through a parent-company bankruptcy that left the outdoor business legally separate, financially tangled, and strategically stuck. It even made it through a global pandemic that emptied downtowns, highways, and airports—the very places out-of-home advertising lives.

And yet, Clear Channel Outdoor Holdings Inc. is still here. Today it sells what it calls out-of-home advertising solutions: roadside billboards, street furniture, and airport displays—inventory planted directly into the flow of real life.

Clear Channel Outdoor trades on the New York Stock Exchange as CCO. After a long, messy separation from its radio parent, it operates as an independent public company. As of June 30, 2025, it operated more than 61,400 print and digital displays across 81 Designated Market Areas in the U.S. Now it’s in the middle of another reinvention—shrinking its international footprint to become a more focused U.S. operator, while racing to convert old-school, one-message-at-a-time billboards into digital screens that can change by the minute.

This is a story about leverage—how it can crush even a solid business. It’s a story about the stubborn durability of “dumb” media in a world obsessed with “smart.” It’s a story about whether a century-old industry can learn the language of programmatic buying and data-driven marketing. And more than anything, it’s the story of a company that has spent nearly two decades clawing its way out from one of the most ill-timed leveraged buyouts in corporate history.

II. The Outdoor Advertising Industry: A Business Model Hiding in Plain Sight

Before we get back to Clear Channel’s saga, it helps to zoom out and understand why billboards—maybe the simplest form of advertising ever invented—keep refusing to go away.

The outdoor model is almost disarmingly straightforward. An operator locks up the right to a location—usually through a long-term lease with a landowner, a city, or a transit authority. It builds the structure. Then it sells the space to advertisers, typically in week- or month-long chunks, priced off traffic and estimated impressions. Clear Channel Outdoor’s U.S. network of roadside, airport, and transit inventory reaches roughly 130 million Americans each week, in many of the most valuable “real world” locations you can buy.

The economics are where it gets interesting. Once a board is up, the incremental cost of running the next ad is tiny. On a static billboard, you’re basically paying for printing, installation, and the crew that swaps out the vinyl. Meanwhile, the big costs don’t care whether you sold the space or not: rent for the land, maintenance, electricity where applicable, and the sales organization. That combination—high fixed costs and low marginal costs—creates serious operating leverage. When demand is strong, profits can be fantastic. When demand drops, the business feels it immediately.

Despite all the hand-wringing about “traditional media,” the broader out-of-home market has been growing. Estimates put the global billboard and outdoor advertising market at about $38.3 billion in 2024, with projections reaching about $60.8 billion by 2030. The story behind that growth isn’t that billboards suddenly became trendy—it’s that the industry has been upgrading from one-message-at-a-time posters to digital screens, and making the buying process feel more like modern advertising.

So why has outdoor survived every new medium that was supposed to kill it—radio, TV, the internet, social media?

First: it’s unavoidable. You can skip a pre-roll, scroll past a sponsored post, or block an email. But you can’t install an ad-blocker on your windshield. If you’re crawling down I-10 in traffic, the billboard is part of the environment.

Second: it plays well with everything else. Outdoor tends to amplify other channels instead of replacing them. A TV campaign gets reinforced by boards near stores. A digital campaign extends into the physical world. And in a five-year study between Kantar and CCO, out-of-home is shown consistently outperforming connected TV and digital media on measures like brand favorability, ad awareness, and purchase intent.

Third: it’s local in a way digital still struggles to replicate. Digital targeting can follow you anywhere. Outdoor dominates a specific place. If you’re two miles from a restaurant and you see its billboard right now, that’s not “awareness.” That’s timing.

Then there’s the part people forget: regulation. The Highway Beautification Act and local zoning rules restrict where billboards can go, how big they can be, and how many can exist. It’s not a perfect system—and it’s controversial—but economically it has a weird effect. It makes new supply hard to create. And when supply is capped, the boards that already exist become more valuable. Over time, regulation becomes a barrier to entry that quietly protects incumbents.

By the 1990s and 2000s, that dynamic helped power a massive consolidation wave. Outdoor had long been a mom-and-pop business: local operators with a handful of boards and deep relationships in their towns. Then the roll-ups came, and the giants emerged. The biggest names globally include JCDecaux, Clear Channel Outdoor, Lamar Advertising, OUTFRONT Media, and Focus Media, alongside plenty of regional players like Capitol Outdoor.

In the U.S., the market is led by Lamar, then OUTFRONT, then Clear Channel Outdoor, with JCDecaux much smaller stateside than it is in Europe. And even after decades of consolidation, the category is still fragmented—independent operators collectively make up a huge portion of the market.

That fragmentation cuts both ways. It’s an acquisition pipeline for the big players, but it also means constant competition from local operators who can be scrappier, cheaper, and closer to city hall.

All of this matters because it sets up the core tension in Clear Channel Outdoor’s story. This is a business with high fixed costs, big operating leverage, and real capital requirements—an unforgiving combination if you pile on too much debt. And as Clear Channel would learn the hard way, “simple” doesn’t mean “safe.”

III. The Clear Channel Communications Empire (1972-2005)

Clear Channel Outdoor’s story actually starts with something far smaller than a billboard: one radio station, in one city, bought by a man who wasn’t trying to build a media empire.

Lester Lowry Mays (July 24, 1935 – September 12, 2022) didn’t come up through programming or broadcasting. He was born in Houston, studied petroleum engineering at the A&M College of Texas (now Texas A&M University), then served as an Air Force officer. After the military, he earned an MBA from Harvard and went into investment banking, eventually becoming Vice President of Corporate Finance at Russ & Company. He was a deal guy.

Radio entered his life almost sideways—what his daughter later described as “things kind of happening.”

In 1972, Mays teamed up with Red McCombs to form the San Antonio Broadcasting Company and buy KEEZ-FM (now KAJA-FM) for $125,000. McCombs was already a San Antonio power broker—a car dealership magnate who would later own stakes in the San Antonio Spurs, Denver Nuggets, and Minnesota Vikings. The partnership worked because each brought something the other didn’t: Mays had financial discipline and deal instincts; McCombs had local relationships and capital.

They bought a second San Antonio station, WOAI, in 1975. That deal mattered beyond the numbers. WOAI was considered a “clear channel” station—one of those rare AM frequencies with a 50,000-watt signal that could travel hundreds, even thousands of miles on a clear night because no other station shared the frequency. The phrase stuck. Eventually, it became the name.

Over the next several years, the company bought ten more struggling stations and turned them around—often by flipping formats to religious or talk programming. This became the early Clear Channel playbook: find underperforming assets, tighten operations, and let the economics do the rest. Broadcasting has enormous fixed-cost leverage; it costs roughly the same to run a station whether ten people are listening or ten million. If you can push ratings up even a little, the advertising rates follow—with very little incremental cost.

Regulation opened the door to doing that at scale. In 1984, the FCC loosened ownership limits, allowing companies to own up to 12 AM stations, 12 FM stations, and 12 television stations, up from seven in each category. With expansion on the horizon, Mays took the company public in 1984, raising $7.5 million in an IPO.

But the true accelerant arrived in 1996. The Telecommunications Act rewrote the rules of American broadcasting by lifting national limits on radio station ownership and significantly relaxing local caps. Consolidation, once constrained by law, became a land grab. Under Mays’ leadership, Clear Channel went on an acquisition spree, building a footprint of more than 1,200 stations by 2003—about 10% of U.S. radio outlets—reaching roughly 27% of listeners.

This was consolidation at industrial scale. In major cities, Clear Channel owned clusters of stations, which gave it enormous leverage with advertisers who wanted national reach but local targeting. It wasn’t just big. It was synchronized.

Then, at the exact moment the internet era was beginning to reshape attention, Clear Channel started buying the physical world.

In 1997, it acquired Eller Media for $1.15 billion. Karl Eller was already a legend in out-of-home—he’d built and sold Combined Communications for $370 million in 1978, then done it again. He had started by buying 300 billboards in Phoenix from Gannett Outdoor and scaled that into a nationwide company across 25 large markets. Clear Channel didn’t just buy a billboard portfolio; it bought one of the best builders in the business. Eller stayed on as President and CEO until retiring in 2002.

The strategy was elegantly simple: bundle “ears and eyes.” If Clear Channel owned the radio stations and the billboards in the same markets, it could sell integrated packages—radio spots plus outdoor placements—through one relationship. Local sales teams could cross-sell. National advertisers could coordinate campaigns without stitching together a dozen vendors.

And Clear Channel didn’t stop at U.S. highways. In 1998, it made its first big move overseas by acquiring the UK’s leading outdoor advertising company, More Group plc, led by Roger Parry. From there, it kept buying—outdoor, radio, live events—rolling these assets together under the Clear Channel International banner. Under the umbrella, Clear Channel Outdoor was assembled through deals including Eller Media, Universal Outdoor, and More Group plc, ultimately giving iHeartMedia outdoor advertising presence in 25 countries.

At the same time, the company made one more leap that completed the “own the whole funnel” fantasy. In 2000, Clear Channel acquired Robert F.X. Sillerman’s SFX Entertainment, bringing live events and concert promotion into the fold. Now the company could, in effect, own the soundtrack, the stage, and the marketing: the radio stations that played the music, the venues and promoters that put on the shows, and the billboards that sold the tickets.

By 2005, the empire had settled into three major pillars: Clear Channel Communications running radio operations, Clear Channel Outdoor running out-of-home advertising, and Live Nation (then known as Clear Channel Entertainment) overseeing live event production and promotion. All three were ultimately controlled by the Mays family, including Lowry Mays’ sons, Mark and Randall.

But scale has a shadow. As Clear Channel grew, it became a lightning rod for everything people feared about media consolidation. Smaller concert promoters and radio operators accused it of using its market power to squeeze them out. In 2001, a Denver concert promoter filed an antitrust lawsuit that was settled out of court in 2004.

On the radio side, critics pointed to homogenization: local programming replaced with nationally syndicated content, and “voice-tracking” where DJs who had never set foot in a city sounded like they were broadcasting from it. The argument wasn’t just that radio sounded different. It was that consolidation reduced viewpoint and source diversity, and prioritized efficiency over community connection.

The company also faced allegations of undisclosed promotional arrangements resembling payola, where record labels provided non-disclosed incentives for airplay on its stations. In 2007, Clear Channel reached a settlement with the FCC, agreeing to pay $3.5 million and provide 2,100 hours of public service announcements—without admitting wrongdoing.

Still, by the mid-2000s, Clear Channel Communications sat atop American media: radio, outdoor, and live events, all under one corporate roof and guided from San Antonio. From the outside, it looked like an unbeatable machine.

What happened next would turn it into a cautionary tale—about leverage, timing, and what happens when a business built for steady cash flow gets strapped to a debt load it can’t outrun.

IV. The Leveraged Buyout: Hubris at the Peak (2006-2008)

By late 2006, private equity was in its golden age. Debt was cheap, lenders were eager, and the mega-deal had become a status symbol. If a company threw off steady cash flow, someone on Wall Street was ready to lever it up and call it “value creation.”

Clear Channel looked like the perfect target: a sprawling media empire with predictable ad revenue, a portfolio that could be broken into parts, and plenty of “optimization” private equity could promise with a straight face. Bain Capital and Thomas H. Lee Partners leaned into that logic. They agreed to buy Clear Channel for $37.60 a share—nearly $19 billion in equity value—and the full transaction landed around $26.7 billion once debt was included.

The pitch was simple. Take the company private, separate radio, outdoor, and live entertainment, squeeze costs, and wait for advertising to rebound. In other words: financial engineering plus time.

But the deal was messy from day one. Big shareholders—including Fidelity, Highfields Capital, and CalPERS—pushed back hard, arguing the offer was too low and insisting that part of the company remain publicly traded. Bain and THL raised their bid to get it done, and by the time it closed, roughly 30% of Clear Channel still traded publicly.

Then the world changed underneath them.

As 2007 turned into 2008, credit markets started locking up. The banks that had promised to finance the buyout came back to Bain’s John Connaughton more than once, essentially asking to reopen the terms. At one point, the request was described as “hat in hand.” Soon after, the lenders tried a more direct tactic: refusing to fund unless they got better terms.

Clear Channel and the buyout firms fought back by suing their own banks to force them to honor the commitments. The sponsors ultimately sweetened the deal to keep it alive, and in July 2008—right at the crest of the buyout boom—shareholders finally approved the transaction.

It closed in July 2008. Months later, Lehman Brothers collapsed, and the global economy tipped into the worst downturn since the Great Depression.

The timing wasn’t just unlucky. It was lethal.

The LBO loaded Clear Channel’s balance sheet with massive new obligations. The company took on billions in new debt on top of the roughly $8 billion it already had, pushing total debt above $20 billion. It was the classic buyout structure at full volume: the company effectively borrowed against itself to pay shareholders and finance the acquisition.

And then advertising—the oxygen of the whole enterprise—started disappearing.

As the Great Recession hit, ad budgets were among the first expenses companies cut. Clear Channel’s revenue fell just as its interest burden surged. In the years that followed, the numbers told the story of a company running hard just to stay in place: by 2017, annual interest expense was running at roughly $1.4 billion. Even when it generated cash, much of it went straight to creditors.

At the exact same moment, radio’s business model began to crack for reasons that had nothing to do with the recession. The iPod had already changed listening habits. The iPhone, introduced in 2007, helped fuel an ecosystem of streaming and on-demand audio—Pandora, Spotify, and more—that rewired consumer expectations. Radio wasn’t just cyclical anymore. It was facing a structural shift.

Clear Channel even found itself fighting on new fronts, like opposing the merger of Sirius and XM in 2008—an early sign of how quickly the audio landscape was becoming more competitive and more digital.

Here’s the twist: while radio was getting hit from both sides—economy and technology—the billboards held up better.

Outdoor didn’t have a direct digital substitute. Highways still existed. Cities still moved. Commuters still had to look out the window. Compared to radio, out-of-home was the steadier asset inside a suddenly unstable empire. And as Clear Channel’s situation deteriorated, that stability turned the outdoor division into the crown jewel—the part of the company that still looked like it might be worth something when everything else was under pressure.

So Clear Channel started doing what highly levered companies always do: sell assets, cut costs, and try to buy time.

It sold 56 television stations and their websites, along with 448 smaller-market radio stations, focusing the remaining business on big-market radio and billboards. Live entertainment—already spun off as Live Nation in 2005—was no longer there to help, and would go on to merge with Ticketmaster and become a powerhouse on its own.

Inside the remaining company, the knife came out. In early 2009, Clear Channel announced a major centralization push and layoffs affecting about 1,500 employees. By the time that restructuring finished in May 2009, a total of 2,440 positions had been eliminated.

This was the fundamental change the LBO imposed: Clear Channel went from a media operator to a debt management exercise. Lowry Mays had built the company with a reputation for financial discipline—strong cash flow, growth funded carefully, debt treated as a risk to be managed. The buyout replaced that philosophy with a single, unforgiving mandate: service the leverage.

What the Mays family built over three decades, private equity threatened to unravel in just a few years.

V. The Spin-Off & Survival Mode (2012-2014)

As the parent company lurched from one crisis to the next, Clear Channel Outdoor slowly became the escape pod—the healthier asset that could be separated, at least on paper, from the radioactive debt stack.

That separation had actually started earlier. In November 2005, Clear Channel Outdoor Holdings, Inc. (NYSE: CCO) and its parent, Clear Channel Communications, Inc. (NYSE: CCU), launched an IPO: 35,000,000 shares of Class A common stock priced at $18.00 per share, raising $630,000,000. It was a way to surface value and create a publicly traded currency for the outdoor business.

But the years that followed left a structure that was public in name and constrained in reality. CCO traded on its own, but Clear Channel—the parent that would later rebrand as iHeartMedia in 2014—kept majority control. So even as the billboard business held up better than radio through the Great Recession and its aftermath, its fate was still tied to a parent fighting to keep the lights on.

Inside CCO, strategy stopped meaning “growth” and started meaning “don’t break.” Management focused on protecting the core assets, squeezing more efficiency out of leases, holding the line on cash flow, and servicing debt—always with the looming risk that a covenant tripwire could turn a bad situation into an immediate disaster.

And when you’re managing for survival, you do things you’d never choose in a healthier world.

On January 7, 2016, Lamar Advertising Company purchased Clear Channel Outdoor’s assets in five major U.S. city markets for $458.5 million. It was the kind of deal that tells you exactly where the leverage sat: selling valuable inventory to pay down debt—the reverse of the roll-up playbook that built the company in the first place.

International markets became a pressure release valve. A broader footprint—especially in Europe, including the UK and Scandinavia—meant revenue streams tied to different economies and currencies. It helped diversify the ride. But running a far-flung portfolio is hard when you don’t have the capital, flexibility, or balance sheet to play offense.

These were the “zombie company” years: a business that could still perform day to day, still generate cash, but couldn’t really invest its way into the future. Clear Channel Outdoor wasn’t failing operationally. It was stuck financially—handcuffed by obligations created in an era of peak leverage, inside a structure built more for extraction than reinvention.

VI. The Bankruptcy & Restructuring (2016-2019)

The inevitable finally arrived in March 2018. iHeartMedia—still widely thought of as “Clear Channel,” even after the 2014 rebrand—filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection under the weight of the leveraged buyout it had closed a decade earlier. The company went into court with roughly $20 billion of debt, in one of the largest media bankruptcies in U.S. history and a blunt verdict on the idea that you could safely lever a mature, ad-dependent business to the hilt.

Clear Channel Outdoor didn’t file.

That distinction mattered. CCO and its subsidiaries were explicitly kept out of the Chapter 11 proceedings, protected by the separate corporate structure created years earlier and by the fact that CCO already traded publicly. The outdoor business wasn’t untouched by the chaos—it was still connected to iHeart through ownership and legacy obligations—but it wasn’t dragged into bankruptcy court alongside the radio company.

Over the next year, iHeart negotiated with its major debtholders, led by Franklin Resources Group, to engineer a debt-for-equity swap that would finally make the math work. The deal handed creditors more than 91% of the reorganized company’s equity. Bain Capital and Thomas H. Lee Partners, the private equity sponsors behind the LBO, were left with about 1%.

That’s what leverage does when the cycle turns: equity doesn’t “decline,” it disappears. The original shareholders—including the Mays family—were wiped out. The lenders became the owners.

One of the most important pieces of iHeart’s plan was to fully separate Clear Channel Outdoor. In December 2018, iHeart announced its intent to spin out its majority stake in CCO as part of the reorganization designed to cut debt and exit Chapter 11.

“Today’s announcement is recognition that while iHeartMedia and CCOH are both very strong in their respective areas – iHeartMedia is America’s number one audio company and CCOH is one of the world’s largest outdoor advertising companies – their key constituencies have little strategic overlap,” CEO Bob Pittman said at the time. “We believe that the separation of the two businesses makes strategic and financial sense…”

In May 2019, iHeartMedia emerged from bankruptcy with a new board, and the separation of Clear Channel Outdoor moved from intention to reality. CCO became, at last, what it had long been in theory: an independent public company with governance and a board focused solely on out-of-home advertising.

For CCO, it felt like liberation—permission to think about something other than the parent company’s emergency. But it wasn’t a clean break into a debt-free future. The broader restructuring eliminated about $10 billion of debt across the system, yet Clear Channel Outdoor still carried substantial leverage. The bankruptcy was necessary surgery; the recovery would take time.

Leadership also came into clearer focus. William Eccleshare, a London-based executive who had joined Clear Channel International in 2009 and led that division, became CEO of the company. Scott Wells continued as CEO of Clear Channel Outdoor Americas, reporting to Eccleshare.

After more than a decade defined by financial handcuffs, Clear Channel Outdoor finally had room to operate. The question was what it would do with that breathing room—and whether billboards could be upgraded fast enough to compete in a world that now expected every ad dollar to come with data, targeting, and measurable results.

VII. The Digital Transformation Imperative (2014-Present)

With the balance sheet no longer in full-blown emergency mode, the next problem was existential in a different way: in an ad world increasingly run by dashboards, algorithms, and attribution, could a billboard—by definition, a piece of physical infrastructure—compete with Google and Facebook?

For most of the industry’s history, out-of-home had a nagging handicap. It was great at reach and frequency, but weak on proof. You could point to traffic counts, you could tell a compelling story, but you couldn’t easily answer the question every modern CMO asks: what did I get for my money?

In 2016, Clear Channel Outdoor Americas started building its answer. It rolled out what it described as the industry’s first measurable outdoor advertising solution: CCO RADAR. The basic insight was that the smartphone had become a proxy for real-world movement. By using aggregated and anonymized mobile location data from privacy-compliant providers, RADAR aimed to help advertisers plan campaigns, understand who was likely being reached, and measure what happened after exposure.

That same year, CCOA also took another step that would have sounded almost contradictory a decade earlier: it introduced the automated ability for advertisers to buy ads on its digital formats programmatically. In other words, billboards could be bought with software. Inventory in the physical world could start to behave a little more like inventory on the internet.

Together, those moves were meant to close the historic gap between outdoor and digital. CCO’s proprietary RADAR suite used aggregated and/or anonymous mobile location data to help plan, optimize, and measure digital out-of-home campaigns. The promise was straightforward: connect the ad on the street to what people do in the real world—where they go, what they visit, and how out-of-home influences attitudes and behaviors. For advertisers, it wasn’t just “we put you on a highway.” It was “here’s who you likely reached, and here’s what changed.”

RADAR became Clear Channel’s attempt to make outdoor feel measurable and targetable without compromising privacy. With thousands of audience segment profiles, the pitch was that advertisers could do more than buy a location; they could engage a specific kind of audience, backed by insights into daily habits and movement patterns.

All of that software progress sat on top of a very literal transformation: the conversion of static boards into digital ones.

A static billboard is a single message that sits for weeks and requires printed vinyl and a crew to swap it out. A digital billboard can rotate multiple advertisers in a day, shift messaging by time of day, and update content quickly. That flexibility doesn’t just modernize the medium; it changes the business model. One piece of infrastructure can now sell many “slots,” not just one.

Digital boards also made outdoor feel more relevant in the moment. Brands could run timely creative tied to weather, commuting patterns, or local events. And because multiple ads rotate through the same location, the revenue potential per display goes up.

But the tradeoff is brutal: capital. A digital billboard costs roughly ten times more to install than a static display, even if it can generate three to five times the revenue once it’s up and running. In the United States, CCO operates over 1,100 digital billboards across 27 markets—progress, but still a reminder that converting a nationwide footprint is a long, expensive marathon.

As measurement expectations kept rising, Clear Channel pushed RADAR further into the adtech ecosystem. It announced partnerships that integrated the RADAR data platform with data clean room applications and services from Aqfer, Habu, InfoSum, and LiveRamp. The goal was to make first-party data matching possible for out-of-home in a secure, privacy-conscious way—so brands already using clean rooms could plan and measure OOH campaigns using their own data without exposing sensitive information.

By the late 2010s, the message to advertisers had evolved into a new thesis: outdoor is no longer dumb. With digital screens, programmatic buying, audience targeting, dayparting, optimization, and attribution-style measurement, out-of-home could argue it belonged in the modern omnichannel playbook.

Then came COVID-19—the nightmare scenario for an industry built on people leaving their homes.

When streets emptied, the “unavoidable” medium became suddenly avoidable. According to the Out of Home Advertising Association of America, outdoor advertising revenue fell sharply, including a 30.5 percent decline in the fourth quarter of 2020 versus the prior year. Clear Channel Outdoor was hit hard: it went into the pandemic with the lowest margin among the big three U.S. operators, saw revenue drop about 30%, and finished 2020 with 19% fewer employees. In its Americas segment, revenue declined 31.8% year-over-year, and segment adjusted EBITDA fell 48.2%.

For a moment, the question wasn’t whether billboards could become more digital. It was whether the category could survive a world with no commuters, no downtown foot traffic, and no air travel.

But the recovery came faster than many expected. As JPMorgan Chase & Co. analyst Alexia Quadrani put it, advertisers often shifted campaigns later instead of canceling them outright, and out-of-home was expected to remain relevant once normal activity resumed. Industry forecasts echoed that arc: WARC estimated 2020 out-of-home revenue was far below 2019 levels, with a rebound in 2021 that still didn’t fully close the gap.

And in a strange way, the pandemic also reinforced the logic of the digital transformation. As mobility returned in uneven waves, flexibility mattered. Programmatic DOOH made it easier to start, stop, and adjust campaigns as conditions changed. The broader “return to normal” created renewed appetite for real-world, experiential marketing that screens alone couldn’t satisfy. And as travel resumed after vaccine distribution, the rebound in airports provided a tailwind for one of Clear Channel’s most valuable pockets of inventory.

VIII. Geographic Strategy & Portfolio Mix

Clear Channel Outdoor’s footprint has changed shape more than once. For years, the logic was diversification: operate across geographies, currencies, and economic cycles. Now the strategy has swung the other way—toward a tighter, more concentrated portfolio centered on the U.S. and airports.

Not long ago, the company reported four operating segments: America, Airports, Europe-North (the U.K., the Nordics, and other northern and central European countries), and Europe-South (Spain, plus Switzerland, Italy, and France until those businesses were sold in 2023).

In practice, the heartbeat of the company has always been the Americas business: big highway bulletins, dense urban inventory like posters and shelters, and the airports division that sits at the premium end of the category. Management has pointed to strength in digital and local sales as key drivers, including a quarter in which the America segment delivered record revenue.

Airports, though, are the crown jewel. In 2009, the airports media sales operation began operating as Clear Channel Airports. Today, it manages advertising and marketing contracts in more than 260 airports around the world. The appeal is obvious: travelers are a captive audience with time to kill. In a terminal, you’re not glancing up for half a second at 65 miles an hour—you’re sitting, waiting, and far more likely to absorb the message. Add in premium pricing and long-term contracts, and airport media offers the kind of visibility and durability that out-of-home operators love.

The biggest shift, however, has been what Clear Channel Outdoor has been willing to walk away from: its international businesses.

On March 31, 2025, the company announced it had closed the sale of its Europe-North segment to Bauer Radio Limited, a subsidiary of Bauer Media Group, for $625 million, subject to customary closing adjustments. Management’s message was clear: this wasn’t just a portfolio tidy-up, it was balance-sheet strategy.

“We expect to prioritize using the remaining net proceeds to retire the most advantageous debt in the Company’s capital structure. With the sale of our Europe-North segment completed, we have closed international divestitures amounting to approximately $745 million in purchase consideration, increasing optionality and reducing risk in our business.”

A few months later, on September 8, 2025, Clear Channel Outdoor announced a definitive agreement to sell its business in Spain to Atresmedia for an expected purchase price of EUR 115 million (about USD 135 million), subject to customary adjustments.

“This agreement to sell our business in Spain represents the final step toward completing our process to divest our European businesses. By monetizing our European and Latin American businesses, we have improved our balance sheet and sharpened our focus on growing our America and Airports segments,” said Scott Wells.

Then, on October 1, 2025, the company completed the sale of its Brazil business to Publibanca Brasil S.A., an affiliate of Eletromidia S.A., for $15.0 million, subject to customary adjustments.

The logic behind all of this is straightforward: simplify the story, double down on the markets where Clear Channel believes it has the best competitive position, and use the proceeds to reduce leverage.

“We are following a path aimed at enhancing our ability to drive organic cash flow with the ultimate goal of reducing leverage on our balance sheet.”

Even within the remaining footprint, the push toward higher-performing inventory is visible in the numbers. Digital revenue increased 11.1% to $113.8 million, helped by new digital billboards—including additions under the Metropolitan Transportation Authority contract in New York. That MTA footprint matters because it isn’t just more screens; it’s high-visibility roadside inventory in the biggest advertising market in the country.

This is what portfolio optimization looks like in real life: trading breadth for depth. Fewer markets, fewer distractions—and a bigger bet that scale, digital conversion, and premium locations can do more for the business than a flag planted on every map.

IX. Competitive Landscape & Strategic Positioning

Clear Channel Outdoor competes in an industry with a split personality: a handful of giants at the top, a long tail of local operators underneath, and a new set of would-be middlemen trying to turn physical inventory into something you buy like digital ads.

The big names in out-of-home include JCDecaux, Clear Channel Outdoor, Lamar Advertising, OUTFRONT Media, Focus Media, and regional players like Capitol Outdoor.

Globally, the leader is JCDecaux. In 2023, it operated more than 107.5 thousand billboards worldwide and grew revenue to 3.57 billion euros. JCDecaux also helped define the modern “street furniture” playbook—bus shelters, kiosks, and other public amenities that double as ad real estate—often built around long-term municipal relationships.

In the United States, Lamar is the heavyweight. With a market capitalization of $17.9 billion, it’s built a reputation for steady consolidation: buying up smaller operators, integrating them, and compounding over time. Its REIT status is also a structural advantage, giving it tax benefits Clear Channel doesn’t have.

Clear Channel’s position is trickier. It’s third in the U.S. behind Lamar and OUTFRONT—research estimates Lamar controls about a quarter of U.S. out-of-home revenue, with OUTFRONT next and Clear Channel after that. Yet for years, Clear Channel also carried the second-largest global footprint behind JCDecaux. That used to be a selling point. Now it’s something the company has been intentionally unwinding as it shifts toward a more focused U.S.-and-airports story.

So what’s the differentiation case?

One is digital. Clear Channel has been investing in digital conversions and pairing that inventory with its RADAR data platform to make buying, planning, and measurement feel closer to the workflows advertisers already use elsewhere—especially as programmatic buying becomes more common in out-of-home.

Another is airports. In a category where location is everything, airports are among the most defensible, premium environments: captive audiences, long dwell times, and pricing power that’s hard to replicate with a roadside board.

And then there’s the sheer quality of its urban footprint in major markets—places like New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco—where density and visibility can make certain locations feel almost irreplaceable.

But the threat landscape is shifting too. Digital advertising platforms have started experimenting with aggregating out-of-home inventory, raising the possibility of disintermediation—someone else owning the demand relationship while operators become the “pipes.” Cities and municipalities, seeing how valuable these assets are, have increasingly considered running advertising more directly rather than relying on concession agreements. And longer-term technology shifts—like augmented reality or in-car screens in an autonomous future—hang out there as the kind of change that could alter how valuable “real-world attention” is.

Meanwhile, buyer power keeps rising. When every marketer has an always-on menu of cheap, targetable digital options, out-of-home has to earn its place. That’s why the industry’s battle isn’t just over locations anymore. It’s over proof—measurement, attribution, and the ability to argue that a billboard can be as accountable as a feed ad, while still doing what feeds can’t: show up in real life, at scale, in places you can’t scroll past.

X. Business Model Deep Dive & Unit Economics

Out-of-home looks simple from the road. Financially, it’s a classic operating-leverage machine: fantastic when demand is healthy, unforgiving when it’s not.

The revenue engine is straightforward. Clear Channel sells advertising space on its inventory, usually on week- or month-long contracts. Pricing depends on the basics—traffic, how visible the location is, and whether the display is static or digital. Digital screens change the game because they can rotate multiple advertisers in a day, which means one structure can produce multiple revenue streams. Big national brands and agencies tend to negotiate larger, bundled buys. Local businesses usually work directly with Clear Channel’s regional sales teams.

The cost side is where the story gets more interesting. Most expenses don’t flex down just because demand softens. The biggest line item is site rent: ground leases with property owners and public authorities, often built as minimum guarantees plus a slice of revenue. Then you’ve got maintenance and utilities—especially meaningful for digital boards—and the sales organization, which has to exist whether a board is sold out or sitting empty.

You can see that dynamic in the company’s second-quarter 2025 expense lines. In the America segment, direct operating and SG&A expenses rose 7.5%, and site lease expense climbed 11.1% to $94.1 million—largely tied to the MTA contract.

That’s the core unit economics lesson: revenue is elastic, costs aren’t. When occupancy is high, a lot of incremental revenue drops to the bottom line. When occupancy falls, margins compress fast because the company can’t cut leases and fixed operating costs at the same speed.

Digital conversion is the main lever that improves those economics over time. A static board is typically one advertiser, one message, for weeks. A digital board turns the same location into a rotation. The tradeoff is heavy upfront capital, but the payoff is higher revenue per structure. In simple terms, a static billboard might sell for around $1,000 per week to one advertiser. A digital board in the same spot might bring in roughly $3,000 to $5,000 per week because several advertisers can share the time slots. The incremental cost to convert can be substantial—potentially $200,000 to $400,000 per display—but the logic is that the revenue uplift can earn that back over time.

Management has been explicit about what it thinks this adds up to. “We are powering our cash flow flywheel and expect it will enable us to increase our Adjusted EBITDA between 6% to 8% annually through 2028.”

But over all of this hangs the company’s financial architecture—still shaped by the LBO era. After its second-quarter senior notes repurchases and the August 2025 refinancing, Clear Channel expected cash interest payments of about $184 million for the rest of 2025, and about $400 million in 2026. After redeeming certain senior secured notes, the next scheduled maturity isn’t until April 2028, when $899.3 million of 7.750% Senior Notes comes due.

The stated goal is to bring net leverage down to 7x to 8x by the end of 2028. That’s still high by most standards—but for a company built in the shadow of a disastrous buyout, it represents a meaningful step away from “debt management exercise” and back toward running the business for growth.

XI. Porter's Five Forces & Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis

Porter's Five Forces Analysis:

Threat of New Entrants: MODERATE

Outdoor looks simple from the street, but it’s hard to break into in practice. Permits, zoning, and the grind of locking up locations create real barriers. And even in the digital era, “building” still means steel in the ground and rights on paper. Software doesn’t get you a billboard on the right corner.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

In the best locations, landlords and municipalities hold real leverage. You can’t manufacture a Times Square corner or a prime highway interchange. That said, scale still matters: Clear Channel can negotiate better terms with many landlords, and technology vendors are far more replaceable than the land beneath the board. Longstanding city and transit relationships also make operator switches slow, political, and costly.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE TO HIGH

Big advertisers and agencies negotiate hard, especially with so many digital options competing for the same budget. But outdoor has a unique claim: it reaches people in the real world, in a way you can’t skip or block. Local advertisers, meanwhile, often have fewer substitutes that deliver the same “right place, right time” impact.

Threat of Substitutes: HIGH

The substitute set is enormous: social, streaming, search, online video—channels with built-in targeting and measurement. Outdoor has spent years trying to close that accountability gap through tools like RADAR and programmatic buying. Its saving grace is that it usually complements other media rather than replacing it, and that role gives it some defensive insulation.

Industry Rivalry: MODERATE TO HIGH

The category is concentrated at the top, but competition is still intense on price, quality, and access to premium inventory. Below the giants is a long tail of independents, and they keep the market honest—especially in local and secondary markets.

Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis:

Scale Economies: YES

Scale lets Clear Channel spread fixed costs—sales teams, corporate overhead, and tech platforms—across a bigger base of inventory. It also improves leverage with vendors and many counterparties.

Network Effects: LIMITED

There’s a light network dynamic in programmatic DOOH: more inventory can attract more buyers, and more buyers can make the marketplace more relevant. But it’s not a flywheel on the level of social networks or true digital marketplaces.

Counter-Positioning: LIMITED

A digital-native DOOH player could, in theory, counter-position as “asset light.” But at the end of the day, somebody still has to control the physical inventory. Clear Channel’s biggest historical handicap wasn’t a lack of a strategy—it was the debt overhang that limited how fast it could execute.

Switching Costs: MODERATE

Advertisers don’t face a massive technical lock-in, but switching does create friction: planning workflows, creative versions, and relationship management all take time. Tools like RADAR add stickiness as brands build measurement habits around a specific system.

Branding: WEAK

This is not a consumer brand battle. Advertisers care about where the ads are, how good the inventory is, and what the results look like—not the operator’s logo.

Cornered Resource: YES—THE PRIMARY POWER

This is the moat. The best locations are scarce and, in many cases, effectively non-replicable. A board at a critical interchange, inside a major airport, or in a signature urban corridor is a piece of real estate you can’t “compete” into. Long-term leases and permits turn those spots into quasi-monopolies.

Process Power: MODERATE

Years of experience navigating permitting, servicing contracts, and managing municipal relationships creates real operational know-how. It’s valuable, but it’s not invincible—more like a set of hard-earned advantages than an unassailable fortress.

Primary Powers: Cornered Resource (premium locations) + Scale Economies

The takeaway is simple: Clear Channel’s value isn’t that it owns billboards. It’s that it owns the right billboards—premium, defensible locations—and has the scale to monetize them efficiently. That’s why the strategy points toward concentrating on markets where it’s strongest, then squeezing more revenue out of those assets through digital conversion and better measurement, while keeping a tight grip on costs everywhere else.

XII. Key Inflection Points: The Last Decade

2012: The Spin-Off

Going public put a spotlight on Clear Channel Outdoor’s performance and forced more discipline. But the reality was that iHeartMedia still held the keys, and the debt baggage from the LBO years still sat on the story like a weight vest. The company could operate, but it couldn’t freely fund the kind of growth that required real capital.

2014-2016: Digital Acceleration

This is when the strategic center of gravity shifted. Instead of expanding the footprint, management leaned into converting static inventory to digital. In 2016, CCO launched RADAR and pushed into programmatic buying—an explicit bet that outdoor could win by becoming more measurable and more “adtech-compatible,” not by racing competitors to the lowest price.

2019: Emergence from Parent Bankruptcy

When iHeartMedia came out of Chapter 11 in May 2019, Clear Channel Outdoor finally got what it had been chasing for years: true independence. The balance sheet wasn’t suddenly pristine, but it was clean enough for management to start thinking about offense again—investing in the business instead of just protecting it.

2020: COVID-19

Then the category’s nightmare scenario arrived. With mobility collapsing, Clear Channel took roughly a 30% revenue hit. But the shock also forced hard moves—tightening operations, renegotiating leases, cutting headcount—that permanently improved the cost structure. And when the world reopened, outdoor snapped back faster than many traditional media peers, a reminder that “people being out in the world” is still one of the most durable demand drivers in advertising.

2021-Present: The Programmatic Bet

Coming out of the pandemic, Clear Channel leaned even harder into RADAR and data-driven sales, trying to win brand budgets that might otherwise default to digital. As the company put it: "We saw growth in key markets, including New York and San Francisco, across both national and local sales channels, and in digital and programmatic sales." At the same time, airports returned as travel recovered—becoming an increasingly important profit engine inside the portfolio.

2025: Portfolio Transformation

By 2025, the transformation wasn’t just digital—it was geographic. Clear Channel accelerated its retreat from Europe, turning international assets into cash and using the proceeds to reduce leverage. Management summarized the move plainly: "With the sale of our Europe-North segment completed, we have closed international divestitures amounting to approximately $745 million in purchase consideration." The company’s endgame here is clear: become a more focused U.S. and Airports pure-play, with a simpler story and a balance sheet that can finally support the next phase.

XIII. The Road Ahead: Opportunities & Existential Risks

Opportunities:

Digital Conversion Runway: A lot of Clear Channel’s footprint is still static. Every time a board flips to digital, the company gets to sell more inventory from the same piece of real estate—more messages, more flexibility, more revenue potential. The upfront spend is real, but the playbook is clear and the economics are no longer theoretical.

Programmatic Growth: More ad budgets are being routed through automated buying systems, because that’s how modern media gets planned and purchased. The more out-of-home inventory behaves like the rest of an omnichannel buy—bookable in software, measurable in dashboards—the more it can compete for dollars that used to default to online-only.

Smart City Integration: Cities aren’t just leasing space for ads anymore; they’re exploring “multi-use” infrastructure—digital shelters, kiosks, EV charging stations, Wi‑Fi hubs—where advertising helps pay for the buildout. Clear Channel’s long history with municipal and transit partners gives it a seat at that table, if it can deliver the technology and capital those projects require.

Measurement and Attribution: Tools like RADAR are aimed at the industry’s oldest weakness: proving what out-of-home actually does. If Clear Channel can keep tightening the link between exposure and real-world outcomes—without compromising privacy—out-of-home becomes less of a “nice to have” and more of a defensible, repeatable line item in the budget.

Risks:

Macro Sensitivity: Advertising is famously cyclical, and it’s usually the first spend companies cut when the economy turns. For a business with high fixed costs, that hurts fast. And while Clear Channel has been working to reduce leverage, higher leverage still means less room to absorb a prolonged downturn than a more conservatively financed competitor.

Regulatory: The rules of the road—literally—can tighten at any time. Cities can restrict new construction, limit digital conversions, or clamp down over light pollution and environmental concerns. And in some places, the direction of travel is toward fewer billboards, not more. Regulation rarely gets easier with time.

Technology Disruption: Out-of-home’s advantage is that it sits in the physical world. But the next wave of technology could change how people experience that world. Autonomous vehicles might shift attention inside the car. AR glasses could layer digital content over everything. These possibilities are still speculative, but they’re the kind of shift that could rewrite the value of roadside and street-level attention.

Debt Re-emergence: This company’s history is a reminder that leverage can turn a good operating business into a fragile financial one. Even with a target of 7x to 8x net leverage by the end of 2028, the balance sheet would still be heavily geared. Staying disciplined—especially in good times—is the only way to avoid repeating the LBO-era mistakes.

Competition from Digital: The harsh reality is that some ad dollars may never come back from the biggest digital platforms. When buying is frictionless and measurement is built-in, out-of-home has to fight for attention inside the plan. That pressure doesn’t go away—it’s the baseline of the modern ad market.

XIV. Bull vs. Bear Case

The Bull Case:

Outdoor advertising has a claim that’s getting rarer every year: it still delivers mass reach in the real world, and the modern defenses against advertising—cord-cutting, ad-blocking, skipping—don’t really work. You can scroll past a feed ad. You can’t scroll past a billboard on your commute.

And the industry has been building a better evidence file. In a five-year study between Kantar and Clear Channel Outdoor, out-of-home consistently outperformed connected TV and digital media on measures like brand favorability, ad awareness, and purchase intent. That matters, because “it feels big” isn’t enough anymore; marketers want proof that a medium moves the needle.

The bigger bull thesis is that digital transformation isn’t just a buzzword here. Clear Channel has been trying to turn a historically “dumb” medium into something that fits modern media buying: measurable, targetable, and increasingly programmatic. RADAR is central to that pitch—making it easier to plan campaigns, tie exposure to audience behavior, and buy inventory in workflows that look more like today’s adtech stack. As more of the network converts to digital displays, the medium gets easier to use: faster creative swaps, dayparting, and campaigns that can be optimized instead of locked in for weeks.

Then there’s the moat: location. The best inventory is a cornered resource. You can’t replicate a major highway interchange or an airport terminal. Long-term leases and permits turn premium placements into something close to a local monopoly.

The post-pandemic recovery is another tailwind. When people returned to roads, cities, and airports, out-of-home regained what it sells best: real-world attention at scale. As the company put it, “Our outlook remains positive for the second half of the year, attesting to the strength of out-of-home advertising and our leadership in driving the digital transformation of our industry.”

And if programmatic DOOH is still in the early innings, the upside isn’t just better yield on existing boards—it’s potentially a larger total market as outdoor gets pulled into omnichannel plans by default, not treated as a specialty add-on.

Which is why management frames the moment as a reset, not a grind: “The Company is at a key inflection point. Our transformation over the past few years is creating a U.S. visual media powerhouse - a simplified, de-risked platform with multiple revenue growth engines.”

The Bear Case:

The bear case starts with the most uncomfortable truth: the ad world has structurally shifted toward platforms built for targeting and measurement. Even with tools like RADAR, out-of-home is still competing against digital channels that were designed from day one to be bought, tracked, and optimized in software. That budget share migration may not reverse.

The digital transformation also isn’t free. Converting boards and upgrading infrastructure is capital-intensive, and it’s not a “one and done” project. The company has to keep investing just to maintain competitive parity—while still carrying a meaningful debt load.

There’s also the commodity problem. Outside of premium locations, a lot of inventory can blur together, and when that happens pricing power gets thin. In many markets, the fight becomes less about differentiation and more about rate cards.

History hangs over the story, too. The LBO and bankruptcy era destroyed equity value. Today’s management team inherited much of that damage rather than causing it, but the execution bar is higher when investors have already lived through one “this time it’s different” cycle.

Then there’s disruption risk, both technological and behavioral. In-car screens, AR overlays, and changing commute patterns driven by remote work all threaten the foundational assumption that lots of people will keep moving through the same physical corridors at the same times, looking outward.

Regulation is another persistent threat. Cities can—and do—turn against visual clutter. What’s permitted today might be restricted tomorrow, especially as concerns around light pollution and digital signage grow.

And finally, the balance sheet is still a flashing warning light. As of December 31, 2024, Clear Channel Outdoor reported total liabilities of $8.4 billion versus total assets of $4.8 billion—negative equity of $3.6 billion. The company’s case rests on going-concern value and cash flow, not on a fortress balance sheet. That’s workable in stable conditions, but it leaves less margin for error if the economy turns or the transformation takes longer than planned.

XV. Key Metrics for Investors

If you’re trying to track whether Clear Channel Outdoor is actually executing on its comeback plan—and not just telling a good story—three numbers tend to tell you the most.

1. Digital Revenue Growth Rate

Digital screens are where the modern version of this business lives: higher yield per location, more flexibility, and a product that fits into how campaigns get bought today. So the cleanest signal is simple: is digital revenue growing, and is it coming from both more screens and better monetization of the screens already up? In Q2 2025, digital revenue rose 11.1% to $113.8 million. Over time, the bet is that this pace picks up as more of the network goes digital.

2. Net Leverage Ratio

This company’s history makes one thing non-negotiable: the balance sheet has to keep improving. Management has targeted net leverage of 7x to 8x by the end of 2028. Each quarter, progress toward that range—or slippage away from it—matters because it’s the difference between a business that can invest and compound and one that gets pulled back into survival mode.

3. Airports Segment Revenue Growth

If outdoor has a “best seats in the house” asset class, it’s airports: long dwell times, premium environments, and contracts that tend to be stickier than a roadside board on a month-to-month buy. In Q3 2025, Airports segment revenue grew 16.1%. Watching this line is a read on both the travel cycle and Clear Channel’s ability to hold and grow one of its most defensible profit engines.

XVI. Lessons for Founders, Investors & Operators

Leverage Kills: A great business can still be taken down by bad timing and too much debt. Clear Channel Communications wasn’t collapsing operationally when private equity strapped it with more than $20 billion in obligations. The engine still ran; the balance sheet made it un-drivable.

Asset-Heavy Businesses Require Discipline: When your product is steel, permits, and long-term leases, you don’t get to pivot on a dime. You can’t “ship an update” to a location bolted into the ground. In asset-heavy businesses, capital allocation isn’t just important—it’s destiny, because today’s decisions can shape your economics for decades.

The "Dumb" Business Advantage: Sometimes the unsexy businesses win precisely because they’re unsexy. Billboards aren’t glamorous. They aren’t viral. But they’re durable infrastructure in regulated markets, and they tend to keep throwing off cash when the world changes around them. Low-tech can be a feature, not a bug.

Adapt or Die: Durability doesn’t mean complacency. Outdoor has stayed relevant by absorbing the rules of modern advertising: digital screens, faster creative cycles, programmatic buying, and measurement. Tools like CCO RADAR were part of the industry’s attempt to answer the question advertisers now ask by default: “What did this do?” Legacy industries that don’t learn that language don’t stay legacy for long.

Irreplaceability Matters: The real moat isn’t the billboard—it’s the place the billboard sits. Premium locations are cornered resources. If you own the right corner, interchange, or terminal, competitors can’t simply “build another one” next door. That scarcity is where the pricing power lives.

Cyclicality Requires Balance Sheet Strength: Advertising is a confidence business, which makes it cyclical by nature. When the economy turns, budgets get cut fast—and fixed costs don’t. Companies that enter downturns over-levered often don’t survive long enough to enjoy the rebound. Clear Channel Outdoor made it through because the assets retained value, even when the broader corporate structure around it was breaking.

B2B Relationships Are Underrated: This industry runs on trust: landlords who renew leases, cities that grant permits, airports that award contracts, agencies that keep sending spend. Those relationships take years to build, and they can’t be replicated overnight. They’re a compounding advantage.

The Long Game: Clear Channel’s arc spans more than half a century: roll-ups, reinvention, collapse, survival, and another reinvention. The companies that last usually aren’t the ones that look the most exciting in any single year. They’re the ones that can keep operating through cycles—and still be standing when the cycle turns back in their favor.

XVII. Epilogue: The Billboard Abides

As 2025 closes, Clear Channel Outdoor is back at a familiar kind of inflection point—except this time, it’s choosing the shape of the company, not having it chosen for them. After years of operating as a sprawling, debt-constrained global footprint, it has been shedding international operations and moving toward the focused U.S. pure-play management has been describing. In 2024, Clear Channel Outdoor generated $1.51 billion in annual revenue, up 4.95% year over year.

The tone from the company has been steady, even optimistic:

"We delivered solid financial results within our guidance range during the second quarter, while making good progress executing on our strategic plan. Our second quarter consolidated revenue increased 7.0%, reflecting growth from our America and Airports segments. In addition, our outlook remains positive for the second half of the year."

After that quarter ended, the company refinanced and extended roughly 40% of its debt maturities in two tranches to 2031 and 2033. The nearest maturity now sits in 2028—still a clock, but no longer a countdown that dominates every decision.

None of this makes the road ahead easy. The debt burden, while reduced, remains heavy. Digital advertising continues to siphon budget share from traditional media. And the next economic wobble could compress ad spend fast. But if there’s one thing outdoor has demonstrated for nearly two centuries, it’s an ability to outlast the obituary cycle.

Painted wall advertisements showed up in the 1830s. Radio was supposed to kill outdoor. Television was supposed to kill outdoor. The internet was supposed to kill outdoor. Smartphones were supposed to kill outdoor. Each time, the billboard kept its place—sometimes bruised, sometimes upgraded, but rarely displaced.

The reason is almost embarrassingly simple: humans still live in physical space. We commute on highways. We wait in airport terminals. We walk city streets. As long as people move through the real world, advertisers will want to show up there too. You can block an ad in an app. You can’t scroll past a building. You can’t swipe away a highway.

Clear Channel Outdoor’s bet is that this physical truth still has economic power—that “eyeballs in physical space” can remain premium in a digital-first world. And it’s trying to upgrade the product to match modern expectations: measurable, targetable, and increasingly programmatically bought, while keeping the one advantage digital can’t replicate—the fact that you can’t skip it.

Is Clear Channel Outdoor a value trap or a misunderstood compounder? The answer turns on execution speed. Can the digital transformation scale fast enough to matter? Can cash flow keep improving while leverage keeps coming down? And can out-of-home defend its role in budgets that increasingly default to online channels?

What’s certain is that the billboard—the simple structure rising over that Texas highway—has proven tougher than anyone expected. In an economy obsessed with disruption, the strangest survivor might be the medium that never pretended to be anything other than what it is: unavoidable.

XVIII. Further Reading & Resources

If you want to go deeper—into the numbers, the court filings, and the broader industry context—these are the sources that best map onto the story.

Essential Primary Sources: - CCO's SEC filings, including 10-K annual reports and quarterly 10-Qs (investor.clearchanneloutdoor.com) - iHeartMedia bankruptcy court documents for historical context (PACER database) - JCDecaux annual reports for competitive benchmarking

Industry Context: - Out of Home Advertising Association of America (OAAA) research reports - Geopath OOH measurement data and methodology whitepapers

Historical Background: - "The Master Switch" by Tim Wu for media consolidation context - Harvard Business School case studies on the Clear Channel LBO - "Barbarians at the Gate" for leveraged buyout era context

Trade Coverage: - Billboard Insider for day-to-day industry coverage - AdExchanger for programmatic DOOH developments - Ad Age for broader advertising industry trends

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music