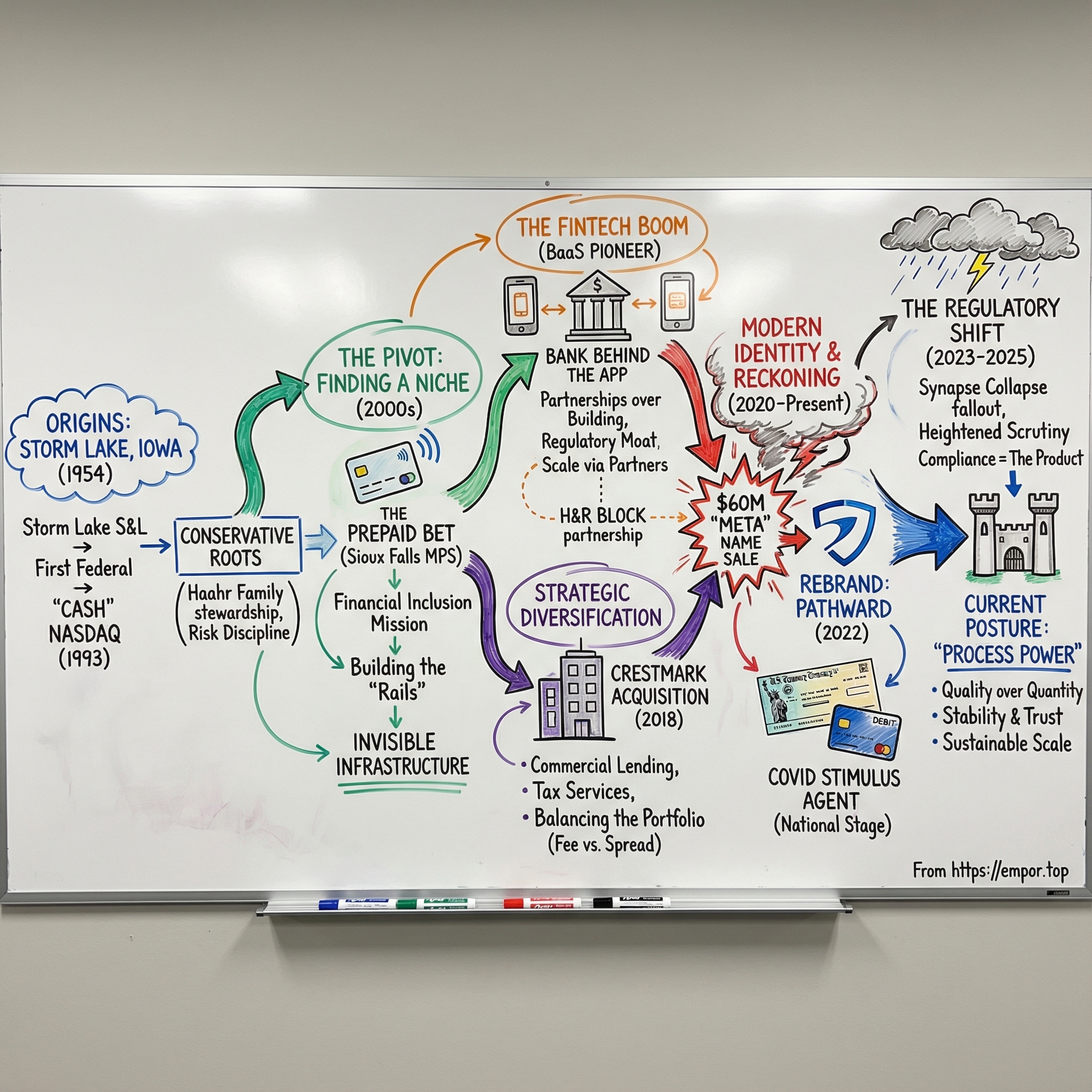

Meta Financial Group / MetaBank: From Prairie Bank to Fintech Infrastructure Giant

I. Introduction: How Did a Small-Town Iowa Bank Become Invisible Infrastructure for Billions?

Picture a plain white envelope landing in your mailbox in the chaotic early weeks of 2021. It’s postmarked from Nebraska. Inside is a debit card preloaded with $600: your second COVID-19 stimulus payment.

On the card is a name most people had never heard of: MetaBank, N.A.

For millions of Americans, it triggered the same split-second reaction: Is this a scam? It wasn’t. That envelope was simply the rare moment when an institution built to stay in the background suddenly stepped into the spotlight.

The IRS described MetaBank, N.A. as the “Treasury’s financial agent.” MetaBank traced its roots back to 1954, and on its website it called itself “a leader in providing financial solutions to customers and businesses in underserved, niche markets.” In other words: not a household name, but very good at sitting behind the household names.

Today the company is called Pathward Financial, trading on NASDAQ under the ticker CASH. It took the Pathward name in 2022, after its parent company sold the “Meta” trademark to Meta Platforms. And while it still carries the DNA of a traditional bank, its business is anything but traditional: banking-as-a-service, commercial finance, and tax services.

This is the story of how a savings and loan founded in a small Iowa farming community turned itself into the invisible plumbing behind some of America’s most recognizable money moments—from H&R Block tax refunds to emergency government payments reaching tens of millions of people. Along the way, MetaBank became the second-largest issuer of prepaid cards in the U.S., ultimately issuing more than a billion cards through partnerships with banks, program managers, payments providers, sponsors, and other businesses.

The tension at the heart of the story is simple: how does a conservative Midwestern bank—shaped by community relationships and old-school risk management—survive, and then thrive, in a world where fintech partners demand speed, scale, and constant iteration? And now that regulators are scrutinizing banking-as-a-service relationships more aggressively than ever, is being “the bank behind the app” a durable advantage—or an existential risk?

To answer that, you have to follow three inflection points: the moment Meta discovered prepaid cards as an overlooked opening, the fintech boom that made “bank-behind-the-app” a core piece of the industry, and the current era of embedded finance colliding with a regulatory reckoning. Threaded through all of it are the Haahr family’s multi-generational leadership, strategic acquisitions, and yes—a trademark deal that reportedly sent $60 million from Mark Zuckerberg’s company back to an Iowa-born bank.

II. Origins: Small-Town Banking in Storm Lake, Iowa (1954–1990s)

Storm Lake, Iowa sits about 75 miles east of Sioux City. It’s a town of roughly 10,000 people, built on agriculture, meatpacking, and the kind of steady rhythms that define the rural Midwest. In 1954, it was the perfect place for one of the most ordinary events in American finance: the founding of a local savings and loan meant to help neighbors buy homes and keep small businesses running.

Pathward began life that year as Storm Lake Savings and Loan Association, founded by Stanley H. Haahr. He stayed closely tied to the institution for decades—serving on the board until 1990 and as chairman from 1981 to 1990.

Haahr wasn’t trying to reinvent banking. He was doing the opposite. He was part of a generation of community bankers who saw their job as stewardship: protect deposits, lend carefully, and keep credit flowing through the community—especially for families trying to own a home and farmers navigating the brutal up-and-down cycles of agriculture.

The bank grew up literally in the town. In 1970 it purchased the Bradford Hotel property at Fifth and Erie in Storm Lake, and by 1972 it had completed construction on a new headquarters there.

For the next few decades, Storm Lake Federal Savings ran the way thrift institutions were supposed to run: conservatively, quietly, and tightly inside the guardrails of Depression-era regulation. This was the Glass-Steagall era, where the lines between types of financial institutions were clearer and the playbook was, by design, cautious. Nothing about it was flashy. But it built something that would matter later: an instinct for compliance and a bias toward risk control.

Then came the S&L crisis of the 1980s—an industry-wide catastrophe that wiped out more than a thousand institutions between 1986 and 1995. Storm Lake Federal survived, largely by not joining the stampede into higher-yield, higher-risk bets that sank so many peers. That period left an imprint: banking can fail fast when risk discipline breaks, and regulators will always have the last word.

In 1993, the institution took another step toward becoming something bigger than a hometown thrift. It changed its name from First Federal Savings and Loan Association of Storm Lake to First Federal Savings Bank of the Midwest, operating as a subsidiary of First Midwest Financial, Inc. On September 20, 1993, First Midwest Financial issued 1.9 million shares at $10 per share, and the stock began trading on NASDAQ under the symbol “CASH.”

That stock conversion didn’t turn Storm Lake into a fintech powerhouse overnight. In the early 1990s, it was still a modest bank by any national standard. But it did mark a break in identity: less like a local savings institution, more like a platform that could raise capital, pursue new lines of business, and think beyond Storm Lake.

And that’s the real inheritance from this era. It wasn’t a particular loan book or a branch network. It was the culture the bank carried forward: respect for regulation, seriousness about risk, and the belief that compliance could be a strength, not just overhead. Those traits would become unexpectedly valuable when the bank started moving into markets where speed mattered, partners were far away, and mistakes traveled fast.

III. The J. Tyler Haahr Era: Finding a New Path (1990s–2000s)

In 1993, James S. Haahr became President and CEO of Meta Financial Group, Inc. In 2005, leadership passed to J. Tyler Haahr. And in 2011, James stepped down as chairman, with Tyler taking the dual role of chairman and CEO. It was a clean handoff across three generations: James and Tyler were the son and grandson of founder Stanley Haahr.

But this wasn’t just family succession. It was a shift in ambition. James pushed the bank beyond its original footprint. Tyler went further and began reshaping what the institution actually was.

Tyler Haahr would go on to lead MetaBank through the era that turned it from a small Midwestern bank into a payments-first platform. He ultimately retired in 2019, after years of steering the company into what had become a sizeable fintech-oriented business.

The question that defined Tyler’s tenure was both simple and existential: how does a roughly $200 million bank in Storm Lake compete? Traditional community banking offered the usual playbook—more branches, nearby markets, slightly better rates. But none of that looked like a real path to scale.

Tyler’s background helped him see a different path. Before returning to the bank, he was a partner at the law firm Lewis and Roca LLP in Phoenix, Arizona. That legal training mattered: he didn’t see regulation as a wall to bang into, but as terrain to understand. In banking, that difference is everything. If you can find a profitable niche that big banks ignore—because it’s too small, too messy, or too compliance-heavy—you can build a real business where competition is thinner.

In the early 2000s, Meta experimented with niche lending. But the real breakthrough came from a corner of finance most banks wanted nothing to do with: prepaid cards. Back then, prepaid was widely viewed as low-margin and high-hassle, aimed at customers mainstream banks weren’t eager to serve. That dismissiveness created the opening.

The bank had already started laying geographic groundwork. On September 6, 2000, it opened its first Sioux Falls office in a temporary facility. Then, in 2004, it launched a new division there: Meta Payment Systems (MPS). In 2005, the broader organization consolidated its identity as well, renaming the bank and its divisions under the MetaBank brand across four market areas: Central Iowa, Northwest Iowa, Brookings, and Sioux Falls.

MPS was the turning point. It wasn’t built to win consumer accounts. It was built to become infrastructure—helping other companies offer financial products without having to become a bank themselves. And Sioux Falls, South Dakota wasn’t an accident. The state had long attracted credit card operations thanks to favorable banking rules. MetaBank intended to tap similar advantages for payments and prepaid.

Tyler later summarized just how wide that infrastructure vision became: the payments division was anchored in prepaid, but it also sponsored a huge share of white-label ATMs—those machines you see in convenience stores, restaurants, and hotels—working with Visa, Mastercard, and other banks to keep money moving.

The strategic leap was realizing that being invisible could be the business model. Instead of building a consumer brand, MetaBank could power other people’s brands. The hard part—and the moat—wasn’t marketing. It was earning the right to issue FDIC-insured card products, navigating the rules, and building the operational and technology backbone to do it reliably at scale.

IV. The Prepaid Card Revolution: Becoming the Rails (2000s–2010)

If Tyler Haahr supplied the strategy, Brad Hanson helped turn it into a machine.

Hanson arrived at MetaBank in 2004 and quickly became a central figure in making prepaid real, not just plausible. As president of Meta Financial Group, MetaBank, and Meta Payment Systems, he helped build what would become one of the industry’s major platforms—spanning prepaid card issuance, ACH origination, and ATM sponsorship. In the prepaid world, Hanson earned a reputation as an innovator because he wasn’t just selling a product. He was building the underlying system that made whole categories of products possible.

He moved fast. Hanson saw the opening in prepaid and worked to win internal support to pursue it. Then he pushed the idea further: if MetaBank could sponsor and support one prepaid program, it could support many—processors, program managers, and other third parties that wanted to offer payments products without becoming a bank themselves.

There was also a mission baked into the model. Hanson believed prepaid could bring real financial access to people traditional banks routinely left behind. And the market was enormous. In the mid-2000s, prepaid still felt like the financial equivalent of the Wild West—but the “why” was straightforward: tens of millions of Americans lived without stable access to mainstream checking accounts. They relied on check cashers with punishing fees, or they ran their lives in cash, with all the friction and risk that came with it.

Haahr framed MetaBank’s approach in plain terms: “our goal is financial inclusion for everyone. So since a lot of people don't qualify for a checking account at a traditional bank, roughly 28% of the population is either unbanked or underbanked, according to a Wall Street Journal article. For products, the traditional prepaid card started with the gift card, but there are also rebate and loyalty cards. And the majority of our prepaid business and the fastest-growing part of the prepaid business is really general purpose reloadable and payroll cards. So for people that otherwise would have to take their check to a check cashier, a payroll card is a great solution.”

The model MetaBank built was simple to describe and hard to execute.

MetaBank would do the regulated, bank-only work: BIN sponsorship (the bank identification numbers that let cards run on Visa, MasterCard, and Discover), the compliance and controls needed for FDIC-insured products, and the technology backbone to move money, reconcile balances, and keep transactions flowing cleanly. Then partners—program managers, retailers, employers, even government entities—would do what banks usually struggle with: distribution, branding, customer acquisition, and day-to-day front-line interaction.

MetaBank stayed mostly invisible. But it was essential.

That invisibility was the point. The economics worked because the heavy fixed costs—compliance programs, risk systems, processing infrastructure—could be amortized across huge volumes. One transaction doesn’t pay for much. Millions and then billions of them do.

By 2009, MetaBank pushed further into retail prepaid. It introduced a new retail product line, and Meta Payment Systems became a leading issuer of rebate and gift cards in the U.S. and internationally, as well as one of the top issuers of Visa, MasterCard, and Discover prepaid cards.

Hanson also helped shape the broader industry, becoming a founding member of the Network Branded Prepaid Card Association, a key trade group for prepaid.

By the end of the decade, MetaBank had gone from a small-town bank with an interesting idea to a real force in prepaid and payments infrastructure. In the years that followed, it started showing up in industry rankings for top-performing banks and thrifts—recognition that, while not glamorous, was a signal that this odd hybrid model was working.

And with that, the stage was set. Prepaid wasn’t the endgame. It was the wedge—the product that let MetaBank build the rails, prove it could operate at scale, and earn credibility with partners. The next chapter would be even bigger: the fintech boom, when “the bank behind the app” became one of the most important roles in modern finance.

V. The 2010s: Financial Crisis Aftermath & Strategic Bets

The 2008 financial crisis didn’t just rattle banks. It rewired the rules of the game. For MetaBank, the aftermath cut both ways.

On the threat side, Dodd-Frank arrived with a wave of new requirements that pushed compliance costs higher for everyone. And then there was the Durbin Amendment, which capped debit-card interchange fees—but only for banks above $10 billion in assets. MetaBank stayed under that line, and that detail mattered. In a business where pennies per transaction add up to real money, being on the right side of a regulatory threshold can turn into a structural edge.

On the opportunity side, the crisis thinned the field and expanded the market. As banks tightened risk controls and shut down accounts, more people found themselves pushed to the margins—locked out by overdrafts, credit issues, or closures. The underbanked population grew, and prepaid cards became a practical alternative. MetaBank had been building for exactly that customer, and now the tailwinds showed up.

By 2017, the growth was visible enough that Fortune named Meta Financial Group one of the top 100 Fastest-Growing Companies.

Around the same time, MetaBank spotted a second engine: taxes. Tax refunds are one of the most reliable annual flows of money in America, and they land disproportionately with the same customers prepaid served so well. Every year, taxpayers want their refund faster than the standard timeline. That “faster” is where the business lives—refund transfers, advances, and the rails that move the money.

So MetaBank started buying the infrastructure.

In 2014, it announced the acquisition of AFS/IBEX Financial Services Inc., an insurance premium financing company based in Dallas. In 2015, it announced the acquisition of Refund Advantage, a tax refund-transfer software company based in Louisville.

Then, in 2016, two more pieces dropped into place: EPS Financial in November, a tax-related financial transaction solutions provider headquartered in Easton, Pennsylvania, and Specialty Consumer Services (SCS) in December, a consumer tax advance services provider with an underwriting and loan management system based in Hurst, Texas.

Taken together, these weren’t random add-ons. They were a vertical integration plan. MetaBank wasn’t content to sit in the background simply issuing cards and processing transactions. It was stitching together the software, underwriting, and servicing capabilities needed to own more of the tax moment end to end—and capture more value each time a refund hit.

Tyler Haahr described the payoff plainly: a model unlike any other nationwide had helped grow the Sioux Falls-based company’s market value dramatically over five years, fueled in large part by its push into tax-related services. Prepaid cards weren’t just a product anymore; they were a distribution channel for refund flows, refund transfers, and advance loans.

And then there was H&R Block—a partnership that captured both the promise and the fragility of this strategy. Meta had been working with H&R Block as recently as 2017, but the tax preparation company ended the partnership the next year. A relationship that can reshape your income statement can also disappear quickly.

In 2020, the two sides came back together under new terms. MetaBank announced it had entered into a program management agreement as part of a three-year strategic banking relationship with Emerald Financial Services, LLC, a wholly-owned indirect subsidiary of H&R Block. MetaBank would serve as a facilitator for H&R Block’s suite of financial services products, including the Emerald Prepaid MasterCard, Refund Transfers, Refund Advances, Emerald Advance lines of credit, and other products distributed through H&R Block’s channels. Meta said a completed agreement with H&R Block could generate $15 million to $20 million in net operating income in 2021.

This was the company’s next step up the value chain. Prepaid had built the rails. The 2010s were about learning to run bigger, more integrated systems on top of them—where the bank wasn’t just moving money, but underwriting it, managing it, and making itself harder to replace.

VI. The Fintech Boom: Powering the Invisible Backend (2015–2020)

By the mid-2010s, venture capital was pouring into financial technology, and a new generation of startups showed up with a familiar promise: we’re going to reinvent banking.

They quickly ran into an inconvenient reality. You can’t “disrupt” your way around a bank charter. Becoming a bank meant years of approvals, a deep bench of compliance talent, and a level of regulatory scrutiny that doesn’t fit neatly into a startup roadmap.

So fintechs did what startups do best: they found a workaround. They partnered.

The deal was simple. Fintechs built the slick consumer experience. Banks like MetaBank provided the charter, the compliance framework, and the operational machinery that actually moved money. That partnership model became known as banking-as-a-service, or BaaS—and MetaBank had quietly been preparing for it for more than a decade.

In hindsight, BaaS didn’t come out of nowhere. It came from a handful of niche banks that chose specialization over the traditional “do everything for everyone” model. MetaBank went deep on prepaid and payments. Others, like Cross River, specialized around targeted lending. At the time, it looked like a weird, even risky bet. But that focus turned out to be exactly what fintechs needed: a bank that was already built to power someone else’s product.

Will Sowell, Divisional President of Banking as a Service at Pathward, has described MetaBank’s role as a kind of prototype. The bank, now known as Pathward after its 2022 rebrand, “provided a precursor to what we now call banking as a service,” he said. “We frequently say we were a BaaS bank before there was a term for it.”

For fintech partners, the pitch was irresistible: speed to market, regulatory know-how, and infrastructure they couldn’t replicate. Instead of trying to become a bank, they could launch with a bank—and do it fast.

“Our national bank charter, combined with the deep relationship we have with our regulators and our expertise within the risk and compliance controls area, really gives us the opportunity to guide our partners and help them deliver financial products to the market that are safe and sound,” said Woyke. In its BaaS division, he explained, Pathward offered “issuing solutions, acquiring solutions, money movement and credit solutions” for customers who couldn’t get them through traditional banks.

One example of how this ecosystem snapped together was Pathward’s long-running relationship with Galileo, a major processor in the fintech stack. The two companies had collaborated since 2005, and in the BaaS era they became part of the same assembly line: Pathward handled issuing and banking services, while Galileo provided API-driven processing. In products like Clair, which offers instant pay access for hourly and gig workers, that split was the whole model. The same general structure showed up in other relationships, including Fundbox, which provides working capital to small and mid-sized businesses.

By this point, Pathward had launched thousands of programs and moved as much as $2.5 billion a day in ACH and wire transactions. The bank was becoming what it had always aimed to be: invisible infrastructure at industrial scale.

But BaaS came with a catch, and it was a big one. No matter how clean the fintech interface looked, regulators didn’t care who owned the app. The bank was still on the hook. Anti-money laundering controls, consumer protection rules, and Bank Secrecy Act compliance all ultimately sat with MetaBank—across every partner, every product experiment, and every growth spurt.

That made early partner banks pioneers in the truest sense: they got there first, and they absorbed the first wave of hits. As one observer put it, the few community banks willing to work with the first generation of neobanks—“your Bancorps and MetaBanks”—helped establish the blueprint for direct fintech-bank partnerships, but they also “took their lumps.” Both The Bancorp and MetaBank (now Pathward) dealt with consent orders in the 2010s.

MetaBank came out of the period with momentum and a bigger seat at the fintech table—but also with scar tissue. The boom taught a hard lesson that would shape the next era: in a partnership-driven model, growth is optional, but responsibility isn’t. Selectivity, compliance investment, and ruthless partner risk management weren’t overhead. They were survival tools.

VII. Strategic Diversification: Beyond Prepaid (2015–2020)

By the mid-2010s, MetaBank’s leadership could see a vulnerability hiding inside all that momentum: the company was getting dangerously concentrated in prepaid cards and tax services. Those businesses could be lucrative, but they were also exposed—vulnerable to regulatory shifts, vulnerable to partner decisions, and vulnerable to the simple reality that fee-driven businesses can turn seasonal and choppy fast. Meta didn’t need a reminder that Washington could redraw the economics of a whole category overnight. It already had one, in the form of Durbin.

So Meta went looking for a second engine—something that could generate steady, on-balance-sheet earnings while the payments side did what payments always does: boom, spike, and fluctuate.

That search led to Crestmark.

Meta Financial Group reached an agreement to acquire Crestmark Bancorp, Inc., the holding company for Crestmark Bank, in an all-stock transaction. Crestmark wasn’t a payments company. It was a commercial lender—business-to-business financing, built around products like asset-based lending, factoring, and equipment finance. The deal was designed to give Meta a national commercial and industrial lending platform, add an immediate pipeline for insurance premium financing, and open up cross-sell opportunities across the company’s growing set of business lines.

The acquisition was announced in January 2018 and closed in August. And in terms of sheer strategic significance, it was the biggest bet Meta had made. Crestmark had been in the commercial finance business for more than two decades, and Meta was effectively saying: we’re no longer going to be defined by one fast-growing niche. We’re going to build a portfolio.

Tyler Haahr framed it as a diversification move with a clear payoff. The transaction, he said, would help Meta “significantly add on-balance sheet loans at attractive yields” through Crestmark’s national lending platform, while also creating cross-sell opportunities for the insurance premium finance business. Crestmark CEO W. David Tull pitched the combination as complementary muscle: a payments-led company and low-cost deposit generator joining up with a “premier, high-margin asset generator,” with synergies that could help the combined entity grow.

At the time, MetaBank reported $5.2 billion in assets and $1.3 billion in total loans as of September 30, 2017. On a pro forma basis, the combined company would have been larger, with roughly $6.4 billion in assets and $2.2 billion in loans and leases at the end of that same quarter. The headline numbers mattered less than what they represented: Meta was deliberately shifting from being mostly a fee-and-flows platform to being more of a balanced bank.

The logic had several layers.

Commercial finance could generate consistent net interest income—exactly the kind of stabilizer that could smooth out a business mix dominated by prepaid and tax. The customer bases also fit together on paper: the small and mid-sized businesses using Crestmark’s financing products could be candidates for payroll cards and other payment solutions. And Meta’s prepaid programs generated deposits—funding that could support Crestmark’s lending at attractive spreads.

This wasn’t Meta’s first step in that direction. The Crestmark transaction built on its earlier lending acquisition of AFS/IBEX in December 2014. But Crestmark took the idea to a different scale, and it sharpened the strategic intent: build lending capabilities that could offset the seasonality of the other divisions. Meta Payment Systems lived in peaks—holidays, tax season, and major program cycles. The tax-related businesses—Refund Advantage, EPS Financial, and Specialty Consumer Services—were inherently tied to the calendar. Crestmark promised a steadier baseline.

With the deal closed, Crestmark leadership also moved into the center of the organization. W. David Tull and Michael R. Kramer joined the board of directors of Meta and MetaBank. Mick Goik, Crestmark’s president and COO, became an executive vice president of MetaBank and president of the Meta Commercial Finance Division, which would include Crestmark.

But diversification isn’t just additive. It’s complicating.

After Crestmark, Meta wasn’t simply a payments infrastructure company with a quirky niche. It was now operating across transaction processing, consumer-facing programs, commercial finance, and insurance premium finance—businesses with different risk profiles, different regulatory expectations, and different ways to win. The integration didn’t just require systems and org charts. It required a new kind of managerial rhythm: one that could run a portfolio instead of a single play.

By the end of the decade, the defining question had changed. It wasn’t “How does a small bank compete?” anymore. It was “What kind of company are we becoming?” And the answer would depend heavily on what happened next—because leadership was about to change hands.

VIII. The Pathward Rebrand & Modern Identity (2020–Present)

The COVID-19 pandemic hit in early 2020 and, almost overnight, it turned MetaBank’s “invisible infrastructure” into something the whole country could see. The bank’s core competency—moving money fast, at scale, through partners—suddenly became part of the national emergency response.

In January 2021, MetaBank issued prepaid debit cards of up to $600 to millions of Americans as part of the second round of COVID-19 Economic Impact Payments. MetaBank was acting as the U.S. Treasury’s “financial agent” for that distribution.

And the reason the government leaned on debit cards was as simple as it was urgent: speed. The IRS said it was sending prepaid debit cards “to speed delivery of the payments to reach as many people as soon as possible.”

For MetaBank, being selected for that role was validation at the highest level. A bank that started in Storm Lake had become trusted to help deliver emergency relief nationwide. Pulling it off meant processing and distributing cards at massive scale, under extreme time pressure—an operational test that only a small handful of institutions were even set up to handle.

Then, in late 2021, a completely different kind of event forced another big shift. Mark Zuckerberg’s newly renamed Meta Platforms needed the “Meta” trademark for its metaverse ambitions. In December 2021, Meta Financial Group sold its “Meta” trademark to Facebook’s parent company (now Meta Platforms) for $60 million, and agreed to phase out the name within one year. In March 2022, the financial services company announced its new brand: Pathward.

The timing wasn’t purely reactive. The company said it had already started a branding strategy review with the goal of unifying its prior acquisitions under a single name. Brett Pharr, CEO of MetaBank, framed the new identity around mission: “Our new name serves as a constant reminder of the importance of creating a path forward for the unbanked, underbanked, and underserved to help them achieve economic mobility.”

The rebrand wasn’t free. Company disclosures put the cost at roughly $15 million to $20 million out of the $60 million proceeds. President Anthony Sharett said the rebrand work was underway before the Meta Platforms deal, and that contractual obligations prevented the company from describing exactly how the trademark agreement came together. What he could say was that the parties “made contact with one another” and ultimately reached a deal. “Our new name and branding reflect our goal of charting a path forward and helping our clients reach the next stage of their financial journey,” Sharett said.

A leadership transition also arrived as the company entered this era. In 2021, Hanson announced plans to retire. Brett Pharr was named CEO, and Anthony Sharett was named President of Meta Financial and MetaBank—setting the team that would carry the company into the Pathward chapter.

Financially, the business was performing like a very different kind of bank. The company reported net income of $156.4 million, or $5.26 per share, for the fiscal year ended Sept. 30, up from $141.7 million, or $4.38 per share, the prior year. Return on assets increased as well, and Pharr called it a “landmark year” in the effort to unify the company under a single brand.

The rebrand mattered for another reason: it fit the story investors were already seeing in the numbers. A 2020 Andreessen Horowitz analysis, using a three-year average, found MetaBank’s return on equity and return on assets well above industry averages.

And Pathward wasn’t just changing names. It was sharpening what it actually was.

In March 2020, the company announced the sale of its community bank division to Central Bank, a state-chartered bank headquartered in Storm Lake, Iowa. That sale—letting go of the legacy operation that traced back to the original Storm Lake business—was a symbolic break with the past. Pathward was no longer a community bank that happened to do payments. It was a payments and commercial finance company that happened to have a bank charter.

IX. The Strategic Inflection We're Living Through (2023–2025)

The fintech winter hit in 2023 and 2024 like a hard stop. Interest rates rose, startup valuations collapsed, and venture funding dried up. But the event that really rewired the banking-as-a-service world wasn’t a down round. It was a failure.

Synapse Financial Technologies—one of the best-known middleware players in BaaS—collapsed, and it collapsed loudly. Synapse’s product was the connective tissue: it let fintechs embed bank accounts, cards, and money movement into their apps without building direct banking infrastructure themselves. The company raised a bit over $50 million in venture capital, including a 2019 Series B led by Andreessen Horowitz’s Angela Strange. By 2023, Synapse was already wobbling—layoffs, instability, and clients leaving. It filed for Chapter 11 in April 2024, hoping to sell its assets in a $9.7 million deal to another fintech, TabaPay. TabaPay walked away.

And then the human cost showed up.

More than 200,000 accounts were affected, and roughly $85 million in customer funds was reported unaccounted for. In the aftermath—after fintech clients fled and the bankruptcy proceeded—a court-appointed trustee found that as much as $96 million of customer money appeared to be missing. Months of court-mediated efforts among the four banks involved didn’t resolve where the money went. One reason: Synapse’s estate didn’t have the funds to hire an outside firm to fully reconcile ledgers. What was clear, though, was the worst-case outcome for “invisible infrastructure”: everyday customers—people who believed their savings were protected—were the ones stuck in the middle.

Synapse had helped startups like Yotta and Juno, which aren’t banks, offer checking accounts and debit cards by connecting them to partner banks like Evolve. When Synapse failed, it didn’t just break a company. It exposed a structural question regulators could no longer treat as theoretical: when multiple fintechs, middleware providers, processors, and banks touch the same customer funds, who is actually accountable when something goes wrong?

The answer from regulators in 2024 was essentially: the bank. And the crackdown arrived fast.

Evolve Bank & Trust, Synapse’s primary banking partner, received a cease and desist order from the Federal Reserve on June 14, 2024. The order cited major gaps in risk management, anti-money laundering and Bank Secrecy Act compliance, and consumer compliance. It also effectively put Evolve in a penalty box: the bank was prohibited from establishing new fintech partnerships or launching new products for existing partners without prior approval, and it was required to strengthen board oversight and build comprehensive risk management plans.

Evolve wasn’t alone. Blue Ridge Bank, Cross River Bank, and later First Fed Bank faced penalties tied to fintech partnerships, as regulators increasingly pushed banks to implement stricter oversight of these tie-ups. Even so, some industry observers argued the point wasn’t to kill BaaS, but to force it to grow up. James Stevens, a partner in Troutman Pepper’s financial services practice, put it this way: enforcement was a signal that banks need to boost compliance programs, not a sign that BaaS was ending. “Smart BaaS participants are assimilating the guidance and learning from the enforcement activity,” Stevens said. “These participants are making their programs safer and stronger and that trend will continue.”

The numbers underline how hard the pendulum swung. Fintech partner banks accounted for one-third of all formal enforcement orders by federal banking agencies in the fourth quarter of 2023—despite representing only about 3% of U.S. banks.

So where does that leave Pathward?

Pathward’s position in this moment is nuanced. Unlike Evolve, it largely avoided the most serious regulatory actions of this cycle. And it continued to highlight balance-sheet strength: the company and its subsidiary Pathward, N.A. remained above federal minimum capital requirements at September 30, 2025, and stayed classified as well-capitalized and in good standing with regulatory agencies.

But Pathward also understood the mood had changed. In an environment where “move fast” had become synonymous with “break things,” the company leaned into a different message: stability, operating discipline, and trust.

“We want to keep delivering scalable, compliant solutions to our partners, and our goal is always to provide our partners and the end users with solutions they can trust over the long term,” said Will Sowell, Pathward’s Divisional President of Partner Solutions. He framed a FinTech Breakthrough award as validation of what Pathward claimed was its edge: decades in the business, operational rigor, stable governance, and a commitment to building alongside partners, not just onboarding them. Pathward described its offering as a configurable suite spanning issuing, acquiring, digital payments, and consumer credit—built to help payment innovators launch and scale “safely and sustainably.”

That’s the heart of Pathward’s current posture: quality over quantity. Anthony Sharett explained that the company had recently marked 20 years in payments and had been an early pioneer. It even renamed the business line—away from “Banking as a Service”—to signal “cocreation and innovation” with partners. In the earlier era, he said, partners brought Pathward a product they wanted to launch, and the bank found a way to get it onboarded and live. Now, the implicit message is different: fewer partners, deeper diligence, tighter control—and a renewed emphasis on being the kind of infrastructure that doesn’t make headlines for the wrong reasons.

X. Business Model Deep Dive & Unit Economics

By now, Pathward doesn’t look like a traditional bank with a couple of side hustles. It looks like a purpose-built financial infrastructure company that happens to own a bank charter. The model is designed to do two things at once: generate high-volume fee income through partner-led payments, and generate steadier spread income through commercial lending.

The bank reports three segments: Consumer, Commercial, and Corporate Services/Other.

Consumer is where the “bank-behind-the-app” work lives. This is the partner business (formerly labeled banking as a service, now often called Partner Solutions) that helps companies launch and run products like prepaid cards, debit cards, deposit accounts, payment processing, and consumer lending. It’s also where Pathward offers installment and revolving consumer credit products through its credit solutions capabilities.

Commercial is the portfolio business: working capital, equipment finance, structured finance, and insurance premium finance lending solutions. It’s the side of Pathward that looks more like classic banking—underwrite risk, earn interest, manage credit cycles—except it’s been built to pair with the deposits and cash flows coming from the payments side.

Partner Solutions makes money the way payments infrastructure businesses usually do: lots of small economics that compound at scale. Revenue comes from card issuance fees, transaction processing fees, interchange income, and, increasingly, acquiring services. The important operating idea is leverage: once you’ve built the compliance program, the risk controls, and the technology platform, you can run more volume across it without rebuilding the whole machine each time.

Put differently: Pathward’s two pillars are Partner Solutions and Commercial Finance. Partner Solutions powers fintech and payments partners with issuing, merchant acquiring, and digital payment processing. Commercial Finance helps stabilize the overall company with on-balance-sheet earning assets. Pathward noted that acquiring services have shown triple-digit revenue growth, underscoring how the company has been expanding beyond issuing into more of the payments value chain.

That mix has produced strong results. For the three months ended September 30, 2025, Pathward reported net income of $38.8 million, or $1.69 per share, compared with $33.5 million, or $1.34 per share, for the three months ended September 30, 2024. For the fiscal year ended September 30, 2025, it reported net income of $185.9 million, or $7.87 per share, compared with $183.2 million, or $7.20 per share, for fiscal 2024. For fiscal 2025, the company reported return on average assets, return on average equity, and return on average tangible equity of 2.46%, 23.44%, and 38.75%, respectively.

On the top line, Pathward reported annual revenue of $739.31 million for the fiscal year ended September 30, 2024, up 19.55% from 2023. Revenue for the trailing twelve months ending September 30, 2025 was $783.12 million, representing 9.7% year-over-year growth. For fiscal 2025, annual revenue was $783.1 million, up 5.9% year over year.

Just as important as growth is what Pathward chose to exit. On October 31, 2024, Pathward, N.A. completed the sale of substantially all assets and liabilities related to its commercial insurance premium finance business. The purchase price was $603.3 million, plus a $31.2 million premium, and the bank recorded a $16.4 million pre-tax gain on the sale. It was a clear example of portfolio optimization: simplify, redeploy capital, and keep tightening the focus on the businesses where Pathward believes it has durable advantage.

You can see that tightening in profitability metrics too. Net interest margin increased 17 basis points to 7.43% for the third quarter, up from 7.26% in the same period the prior year, driven primarily by an improved earning asset mix from continued balance sheet optimization. When including contractual, rate-related processing expenses associated with deposits on the company’s balance sheet, NIM would have been 5.98% in fiscal 2025’s third quarter, compared with 5.76% in fiscal 2024’s third quarter.

XI. Competitive Analysis: Porter's Five Forces

Threat of New Entrants: Medium-High

Becoming a bank is still brutally hard. A charter takes years, real capital, and the willingness to live under constant regulatory scrutiny. That alone keeps a lot of would-be competitors out. And once a fintech partner is wired into Pathward—technology, operations, compliance processes, program economics—switching isn’t like changing a software vendor. It can mean BIN migration, customer communications, new approvals, new controls, and months of work. In practice, that creates real stickiness.

But the other side of the coin is that the “BaaS tech layer” has gotten easier to buy. Middleware platforms like Synapse, Treasury Prime, Unit, Bond, and Synctera have offered fintechs a packaged way to connect into sponsor banks. That model can make banks feel more interchangeable and can push pricing down by giving fintechs more choices.

Supplier Power: Medium

Pathward’s “suppliers” are a mix of critical infrastructure and hard-to-hire people: core banking technology vendors, the card networks (Visa and Mastercard), and specialized talent. The market for compliance leaders, BSA/AML professionals, and payments engineers is competitive, and fintechs have often been willing to pay more than traditional banks to get them.

Buyer Power: Medium-High

Fintech customers have shown they’ll switch bank partners when they see a better deal, better capabilities, or lower friction. Still, the leverage isn’t unlimited, because switching is painful. Moving a card or account program to a new bank can require re-plumbing integrations, notifying regulators, migrating BINs, and running parallel operations for a period of time. Even when a fintech wants to move, it can take months.

Threat of Substitutes: High

The cleanest substitute is vertical integration: fintechs getting their own bank charters. As that happens, a partner can become a competitor. The line has already blurred in cases like SoFi, which moved from being “just” a fintech partner to owning a charter and doing more of the stack itself.

Competitive Rivalry: High

This is a crowded, high-stakes arena. Pathward competes with other public sponsor banks like The Bancorp (TBBK) and MVB Financial (MVBF), along with private players such as Cross River Bank and Evolve Bank & Trust—banks that built reputations on speed, startup connectivity, and technical execution.

A relatively small group of banks has invested deeply enough to partner directly at scale—Cross River, Pathward, The Bancorp, Column, and Lead. But these platforms weren’t built overnight; in many cases they’re the product of a decade or more of systems work, or new ownership and leadership with fintech DNA. For most banks—even large regionals—the easier path isn’t to build all of this in-house. It’s to partner with someone who already has the tech and the operating muscle.

XII. Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis

1. Scale Economies: Medium

Pathward has real scale benefits, just not the pure, winner-take-all kind you see in software. The biggest fixed costs—compliance infrastructure, risk oversight, and payments technology—get cheaper per transaction as volume rises. But banking scale has a governor: capital requirements and risk management don’t stay fixed as you grow, so you can’t simply “scale to infinity” the way an API company can.

2. Network Effects: Weak

Most fintech partnerships are separate lanes. One new partner doesn’t automatically make the platform dramatically more valuable for the next partner in the way a marketplace or social network works. The upside is more subtle: learnings carry over, integrations become reusable, and the organization gets better at operating the playbook.

3. Counter-Positioning: Strong (Historical), Eroding

Pathward—and other early specialists like Cross River—bet on being narrowly great at specific “unbank-like” lines of business. At the time, that specialization looked like a risky departure from the traditional everything-for-everyone bank model. In retrospect, those pioneers built the early blueprint for what later got labeled banking as a service. The problem now is that the secret is out. More banks are entering, and larger institutions are building competing offerings, shrinking the edge that came from being early and different.

4. Switching Costs: Medium

Once a fintech partner is integrated into Pathward’s platform—technology connections, operating procedures, compliance routines, program economics—switching becomes painful and expensive. That stickiness matters. But it’s not absolute. Competitive pricing, capability gaps, or regulatory pressure can still force a move, even when the move is disruptive.

5. Branding: Weak-to-Medium

Pathward isn’t trying to win consumers; it’s trying to win partners. That means consumer brand recognition is limited by design. What does matter is reputation—especially for compliance strength, reliability, and operational execution—because sophisticated fintechs and payments companies increasingly select bank partners based on who won’t become tomorrow’s headline.

6. Cornered Resource: Medium

The bank charter is a gate: you either have it or you don’t. Beyond that, Pathward’s real “cornered resource” is time—more than two decades of operating experience, partner pattern recognition, and regulator relationships that can’t be recreated quickly.

7. Process Power: Strong

This is the heart of Pathward’s moat. The company’s edge is operational: building, running, and controlling high-volume programs safely over years, not quarters. As Pathward put it when discussing recognition from FinTech Breakthrough, its advantage comes from decades of experience, a deep bench of talent, operational excellence, stable governance, and a commitment to partnership and co-creation. In practice, that shows up as a configurable suite across issuing, acquiring, digital payments, and consumer credit—capabilities partners can use to launch and grow programs “safely and sustainably.”

Overall Assessment: Pathward’s power comes primarily from Process Power—accumulated operational expertise and compliance infrastructure built over decades—plus a historical counter-positioning advantage from getting to this model early. The risk is that both moats fade as the category matures and competitors invest to close the gap.

XIII. Bull vs. Bear Case

Bull Case:

“From our own research, we know that embedded finance is set to grow exponentially over the next several years, and as one of the top BaaS providers, we look forward to being a part of the payments evolution as we help payments innovators sustainably scale their financial solutions.”

That quote captures the core bull thesis: embedded finance is still early. Even after the Synapse-era blowups and the regulatory backlash, the direction of travel hasn’t changed. Commerce platforms, vertical SaaS providers, and consumer apps still want to offer “bank-like” capabilities—accounts, cards, payouts, and payments—without becoming banks. Every one of those products needs regulated rails. Pathward is selling those rails.

In a world that’s consolidating around fewer, higher-quality providers, Pathward’s conservative posture becomes an asset. The more regulators push banks to take direct responsibility for what their fintech and middleware partners do, the more valuable it is to have a sponsor bank that already treats compliance and operational discipline as the product, not the tax. The crackdown can actually clear the field: banks under consent orders, like Cross River, have a harder time onboarding new fintech relationships, which can shift demand toward providers that can still say “yes” without tripping over supervisory constraints.

Pathward also looks less fragile than a pure-play sponsor bank because it isn’t one. Its revenue streams are spread across Partner Solutions, Commercial Finance, and Tax Services, which reduces dependence on any single line. And management has shown it’s willing to reshape the portfolio, not just accumulate assets—the sale of the commercial insurance premium finance business for $603 million plus a premium is a concrete example of monetizing something non-core and redeploying capital.

Finally, the company’s balance-sheet strength and profitability metrics give it options. A strong capital position supports organic investment in controls and technology, and it leaves room for opportunistic M&A when weaker players get forced into exits.

Bear Case:

The bear case starts with the uncomfortable possibility that the banking-as-a-service model doesn’t just get regulated—it gets fundamentally constrained.

Regulators have made it clear they view sponsor banks as the accountable party, regardless of how many layers of fintechs, processors, or middleware sit in between. And the enforcement trend has been moving in the wrong direction for the industry. In 2023, banks engaged in BaaS accounted for 13.5% of all “severe” enforcement actions. The underlying risks may be familiar, but the posture has changed: broader focus, faster escalation, and far less patience for “we’re still building the controls.”

A second structural risk is disintermediation. If the largest, most successful fintechs eventually pursue their own charters, Pathward risks losing the very partners that drive the most volume and fee income. In sponsor banking, your best customers are also the ones most capable of deciding they don’t need you anymore.

Then there’s the industry-wide cost of compliance. Consent orders across the ecosystem highlight the same problem: doing this business “the right way” is expensive, and the bar keeps rising. Cross River’s experience is a useful cautionary tale here. Its rapid growth through fintech partnerships attracted regulatory attention, including FDIC criticism tied to fair-lending compliance weaknesses in 2023 and requirements that can limit new partner or product expansion without approval. Whether or not Pathward faces similar action, the message is that growth in this category increasingly comes with a regulatory speed limit.

And Pathward’s diversification cuts both ways. Commercial finance can stabilize earnings, but it also introduces classic banking cyclicality. In a recession, credit losses rise, provisions go up, and the steady “portfolio” side of the house can turn into a headwind. On top of that, Pathward is still small compared with the megabanks. If large incumbents decide they want to enter embedded finance in a serious way, they have the balance sheets and distribution to make the fight painful.

Key KPIs to Monitor:

-

Partner Solutions Fee Income Growth and Customer Retention: The clearest signal of whether Pathward is winning in its core business. Watch partner adds and losses, renewals, and what fee income does over time as the industry consolidates.

-

Net Charge-Off Rate in Commercial Finance: The early warning system for credit stress and underwriting discipline. If charge-offs rise, earnings come under pressure, and capital flexibility shrinks right when it matters most.

XIV. Lessons for Founders, Operators & Investors

Find the White Space: MetaBank kept winning by going where bigger institutions didn’t want to go. Prepaid cards for the unbanked and underbanked. Tax refund processing. Later, banking-as-a-service for fintechs that couldn’t get a charter. Each time, the niche looked unattractive to incumbents—until it wasn’t. That willingness to serve “messy” markets became a durable edge.

Regulatory Navigation as Competitive Advantage: Pathward has been explicit about what it sells: not just products, but the right to run them. “Our national bank charter, combined with the deep relationship we have with our regulators and our expertise within the risk and compliance controls area, really gives us the opportunity to guide our partners and help them deliver financial products to the market that are safe and sound.” In other words, compliance isn’t merely overhead. Done well, it’s the moat.

Infrastructure Plays Scale Quietly: Pathward is the proof that you can build a massive business without building a famous brand. B2B infrastructure can compound in the background—no consumer acquisition treadmill, no splashy marketing, just operational execution that partners can trust. The invisibility isn’t a disadvantage. It’s the model.

Culture is Strategy: The bank’s roots in Storm Lake mattered. Small-town conservatism, shaped by decades of risk discipline, paired with a willingness to innovate is a rare mix. Most organizations only get one half of that equation: prudence without ambition, or ambition without prudence. Pathward’s synthesis let it take calculated risks without losing the plot.

Know When to Pivot: This company reinvented itself multiple times—thrift to prepaid, prepaid to BaaS, and then into a more diversified financial services portfolio. It didn’t cling to a legacy identity just because it was familiar. It treated strategy as a living thing.

Partner Risk is Existential: The Synapse collapse showed the nightmare scenario in a multi-party fintech stack: when something breaks, customers get trapped in the middle, and accountability snaps back to the bank. The lesson is blunt. You can’t outsource responsibility. Banks and fintechs have to design for failure—clearer controls, more transparency around pooled accounts, stronger consumer protections, and less dependence on any single intermediary that could become a single point of collapse.

The Power of Being Early: Pathward’s biggest advantage may be time. It started building payments and partnership infrastructure before the market even had a name for it. That early start—shared by a small set of pioneers like Pathward, Cross River, and Bancorp—created experience, tooling, and pattern recognition that still matter, especially now that regulators are forcing the whole category to grow up.

XV. Epilogue: The Road Ahead

Pathward Financial now sits at a strange, almost poetic crossroads in American finance. It survived when much of its thrift-era peer group collapsed in the 1980s. It reinvented itself from a community bank into a prepaid-card specialist, then into the bank behind fintech. It even sold its name to one of the most valuable companies in the world for $60 million. And now it’s navigating a regulatory climate that’s become sharply more skeptical of the very partnership model it helped popularize.

In 2024, as the company marked roughly 20 years in payments, it picked up recognition from Finovate—an award Pathward framed as a vote of confidence in its partnership approach and its ability to build products with third parties, not just for them. “Pathward's Partner Solutions team is honored to be recognized by Finovate. We have an incredible team, and it's rewarding to earn national recognition as the Best Banking as a Service Provider,” said Will Sowell, Pathward’s Divisional President of Partner Solutions. He added, “The payments ecosystem is evolving rapidly, and we expect tremendous growth in embedded finance as more companies see the value in adding these products and services.”

But the next chapter won’t be written by awards. It’ll be written by forces that sit largely outside management’s control.

Will regulators fundamentally reshape banking-as-a-service with new requirements around real-time tracking and reconciliation of partner funds—an idea some are already informally calling the “Synapse Rule”? The FDIC’s proposed rule, which would require near real-time reconciliation of fintech partner accounts, could change the operating model for sponsor banks in a very real way. If that becomes the new standard, the winners won’t be the fastest movers. They’ll be the operators with the deepest controls, the cleanest data, and the strongest ability to prove—at any moment—where customer money is and who owns it.

At the same time, the market is still sorting out what embedded finance really is. Is it a durable shift, where every software platform eventually offers accounts, cards, and payments? Or was the first wave inflated by cheap capital and optimism, with the Synapse collapse acting as the pin?

And then there’s the long-term question underneath all of it: will fintechs keep renting bank partnerships as the fastest path to market, or does the post-Synapse era accelerate the push toward direct charter acquisition for the biggest players?

Whatever the answers, the arc from Storm Lake to Sioux Falls to national payments infrastructure remains one of the more unlikely transformations in modern American business. This was a family-led institution that could’ve remained a small-town bank. Instead, it kept repositioning—again and again—staying close to the seams where regulation, technology, and distribution meet.

The same conservative culture that helped it survive the S&L crisis also proved flexible enough to embrace prepaid cards, tax services, BaaS-style partnerships, and commercial finance. And the regulatory fluency built over decades became the exact asset fintechs needed when they wanted to move fast without building a full compliance organization from scratch.

For investors, the bet is straightforward to state and hard to handicap: does Pathward’s history of adaptation carry forward into a moment when the rules are changing mid-game? Maybe the company emerges stronger yet again, as weaker operators get pushed out and the market consolidates around “flight to quality.” Or maybe the combination of regulatory and competitive pressure proves more constraining than anything it has faced before.

Either way, Pathward offers a clear lesson in how infrastructure businesses really scale. Not through consumer love. Through being the regulated, operationally excellent backbone that other brands depend on. The prairie bank that became invisible infrastructure changed American payments in ways millions of people touch every day without ever seeing its name—and for a company built to be essential, that might be the most fitting legacy of all.

XVI. Further Reading & Resources

Essential Resources:

-

Pathward Financial annual reports and investor presentations – The story in the company’s own words, straight from management and filings. Available at PathwardFinancial.com

-

Alex Johnson's Fintech Takes newsletter – Sharp, practical analysis of banking-as-a-service, including ongoing coverage of regulation and the industry’s shifting fault lines

-

OCC and Federal Reserve enforcement actions database – The primary-source paper trail on what regulators are focusing on across sponsor banks

-

Federal Reserve Request for Information on Bank-Fintech Relationships (July 2024) – A window into the rulebook regulators are building in the wake of the Synapse collapse

-

Synapse Financial Technologies bankruptcy court filings – The clearest first-hand record of how the BaaS stack can break, and what that failure looks like in real time

-

Andreessen Horowitz's analysis of fintech banking economics – A useful framework for thinking about BaaS economics and why “infrastructure” can be both powerful and fragile

-

Crestmark Financial acquisition S-4 filing – The detailed rationale behind Meta’s biggest diversification move, in the language that mattered most: what they told shareholders

-

Consumer Federation of America's analysis of BaaS supervision gaps – A critical counterweight: where watchdogs think the industry’s oversight model has been weakest

-

Gibson Dunn Monthly Bank Regulatory Reports – A reliable, ongoing digest of enforcement actions and regulatory developments

-

American Banker's ongoing BaaS coverage – Industry reporting that adds context, color, and updates as the category continues to evolve

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music