Calix Inc.: The Broadband Infrastructure Story You've Never Heard

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

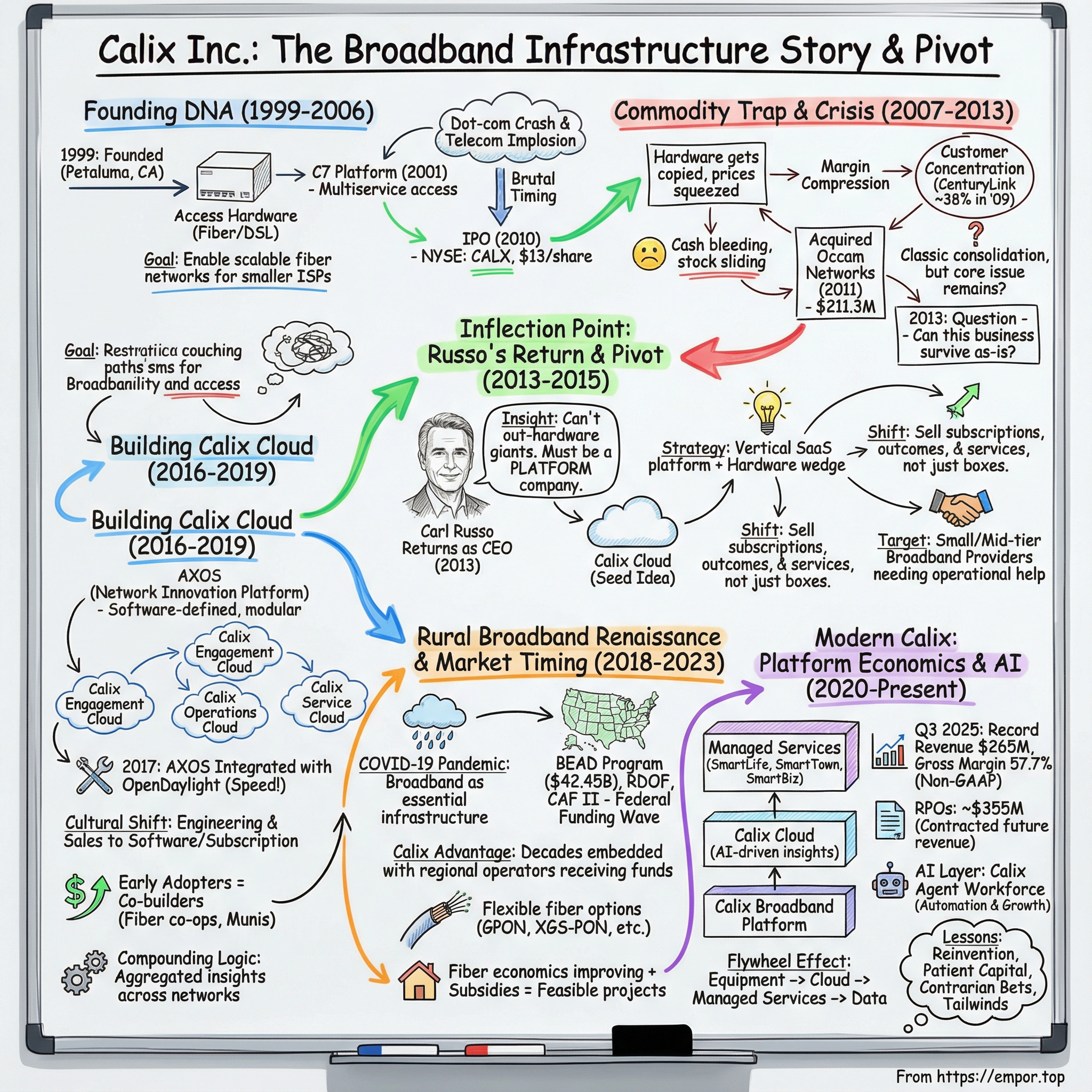

Picture this: it’s 2013, and Carl Russo is walking back into Calix’s headquarters in Petaluma, California. He helped found the company in 1999. But now the place feels different—quieter, heavier. Calix, a telecom equipment maker, is bleeding cash, losing customers, and watching its stock slide toward penny-stock territory. The board has called Russo back as CEO, and plenty of people privately assume his job is to end it politely: sell what’s left, wind things down, and move on.

Russo didn’t see a funeral. He saw a pivot.

Because Calix’s problem wasn’t just execution. It was the category. Being “the box company” in telecom is brutal. Hardware gets copied, prices get squeezed, and customers treat you like a line item. Russo’s contrarian insight was that Calix couldn’t win by trying to out-hardware the giants. It had to become something else entirely: a platform company that could help America’s smaller broadband providers run and grow their businesses—not just light up networks.

That’s the story we’re telling.

Today, Calix describes itself as an agentic AI cloud and appliance-based platform and managed services company. Communications service providers use the Calix platform and managed services to simplify operations and engagement, innovate for consumer, business, and municipal subscribers, and grow both their businesses and the communities they serve. More than a thousand broadband service providers use Calix systems, including GigaSpire, to deliver the subscriber experience those providers increasingly compete on.

If you only look at revenue, you’ll miss the point. In 2024, Calix reported $0.83 billion in revenue, down from $1.03 billion in 2023. But the more interesting story is what sits underneath those totals: a company spending years and billions of dollars pushing itself out of the commodity trap and into an end-to-end cloud-and-software platform model. Over 13 years, Calix invested $1.3 billion to make that transition.

So here’s the question that animates the entire episode: how did a telecom equipment maker—selling boxes to phone companies in an industry famous for margin compression—transform into something that increasingly looks like a vertical SaaS platform?

The answer runs through a near-death spiral, the return of a founding CEO, a patient decade-long bet on software, and then a bizarre bit of timing: federal broadband policy, a global pandemic, and fiber economics all hitting at once. It’s a story about unsexy infrastructure that makes modern life possible—and what happens when a company decides its only path forward is radical reinvention.

II. The Telecom Equipment Context & Founding DNA (1999-2006)

Rewind to 1999. Most people still got online through dial-up—the screeching modem handshake that felt like it might wake up the whole house. Amazon was “that bookstore on the internet.” Google was barely a year old.

But inside telecom, it was pure gold rush.

Fiber-optic networks. DSL. The promise of always-on broadband. Investors and operators were pouring billions into the idea that bandwidth demand would climb forever. Companies raced to lay fiber across the country, convinced they were building the next great American utility.

Calix was born in that moment. In August 1999, Michael L. Hatfield and Carl E. Russo founded the company in Petaluma, California, as a Delaware corporation originally named Calix Networks, Inc. The mission was straightforward and highly specific: build access hardware that would let rural broadband service providers deploy scalable fiber networks—and finally move beyond the limits of copper in places big telecom tended to overlook.

Russo’s resume fit the era. From April 1998 to October 1999, he served as president and CEO of Cerent Corporation, which Cisco acquired. Then, from November 1999 to May 2002, he was Cisco’s vice president of optical strategy and group vice president of optical networking. He’d lived at the center of the telecom equipment boom. But his key insight wasn’t just technical—it was about the customer. America’s small and mid-sized telephone companies were getting squeezed by the cable broadband revolution. They needed a way to compete, and the big vendors weren’t building for their scale.

With $14 million in venture funding, Calix went after a growing demand: integrated voice, data, and video. The bet was that the country’s thousands of smaller incumbents—especially rural operators—were about to be forced through the same transition: from copper to fiber, from voice to data, from basic phone service to real broadband. They needed equipment that was capable, but also affordable and sized for them.

Early on, Calix poured its energy into multiservice access platforms. That work culminated in December 2001 with the launch of its flagship C7 platform: a multiservice, multiprotocol system that could aggregate and deliver traditional phone service, high-speed data, and broadcast or on-demand video over both copper and fiber. In plain English, it gave carriers a way to upgrade their networks without ripping everything out at once.

The timing, though, was brutal. Calix was founded just before the dot-com crash and the telecom implosion that followed. WorldCom and Global Crossing would file for bankruptcy. Equipment makers got hammered. Entire categories collapsed under the weight of overbuilding and debt. Calix survived in part because it wasn’t chasing the same giant, speculative buildout customers—it was selling to smaller carriers still trying to serve real communities.

Over time, the company raised $108 million across three funding rounds. A notable Series C in June 2007 brought in $57.5 million. Early institutional investors included Redpoint Ventures, Azure Capital Partners, Meritech, and Foundation Capital. That capital fueled more product development and helped Calix expand with tier-2 and tier-3 telephone companies—the regional operators too small to be strategic priorities for giants like Alcatel-Lucent or even Cisco.

And then came the milestone that closed Calix’s founding chapter and opened a new one: the IPO.

On March 24, 2010, Calix announced the pricing of its initial public offering at $13.00 per share. Calix offered 4,166,666 shares of common stock, and certain selling stockholders offered 2,162,266 shares. The stock began trading the same day on the New York Stock Exchange under the symbol “CALX.” Goldman, Sachs & Co. and Morgan Stanley & Co. Incorporated acted as lead joint book runners, with Jefferies & Company, Inc. and UBS Securities LLC as joint book runners.

For a company that started on $14 million of venture money, and did it through the shadow of a telecom crash, ringing the bell on the NYSE was a real accomplishment.

But it also meant something else: Calix was now stepping onto the most unforgiving stage there is for a hardware company. Because once you’re public, you can’t hide from the basic physics of the business—competition shows up fast, differentiation erodes, and “great tech” is rarely enough.

III. The Commodity Trap: Growth, Competition & Crisis (2007-2013)

The years after the IPO were supposed to be the victory lap. Calix had real technology, real customers, and now the public markets behind it. Revenue climbed. The customer list grew. From the outside, it looked like a clean telecom equipment success story.

But underneath, the ground was shifting.

Calix was falling into the commodity trap: the slow, brutal squeeze that happens when what you sell starts looking interchangeable. In telecom equipment, that squeeze is especially vicious. You’re shipping expensive physical hardware to a small set of highly sophisticated buyers. Those buyers—phone companies—have their own margins under pressure and negotiate like their lives depend on it. Meanwhile, the technology never stops moving, so you keep spending on R&D just to stay relevant… even as the market prices the same capabilities lower and lower.

For a while, the financials still looked good. From 2009 to 2013, revenue grew at a 13.2% CAGR. Gross margin improved by 11.8 percentage points, and operating and net income margins improved by 3.5 and 5.1 percentage points. It was progress—but it also made the situation easier to misread. These were the good years of a fragile model.

The biggest fragility was customer concentration. CenturyLink and its predecessors Embarq and CenturyTel accounted for 29% of Calix’s revenue in 2010—and 38% in 2009. When one customer is that large, you don’t have “accounts.” You have weather systems. A single change in purchasing plans can ripple through your entire company.

Calix tried to get bigger and stronger the way telecom vendors usually do: by buying another telecom vendor. On February 22, 2011, Calix acquired Occam Networks in a stock-and-cash transaction valued at approximately $211.3 million. The pitch was straightforward: a broader broadband access portfolio, faster innovation, and more scale across the Calix Unified Access portfolio.

It was a classic consolidation move—combine product lines, cut overlap, and hope the math works.

But the core issue didn’t go away. Calix was still competing as a hardware company in a market where hardware was getting cheaper, faster than any one company could keep differentiating it.

And then the cracks started showing. In the first half of 2014, revenue declined 0.6% and profitability worsened. Gross, operating, and net profit margins all fell. The market for broadband access equipment was expected to keep growing, but Calix ran straight into near-term challenges that hit growth at the worst possible time—right when the company needed momentum to justify its model.

Because the competitive landscape was unforgiving. Giants like Alcatel-Lucent, Nokia, and Cisco had scale advantages in R&D and manufacturing that Calix simply couldn’t match. Huawei and other Chinese competitors were willing to play a different game entirely, selling at razor-thin margins to win share. And Calix’s customers—regional telcos—were becoming even more price-sensitive as cable companies kept taking broadband share.

Even the geography worked against them. Dell’Oro Group noted that most GPON revenue was generated outside the United States. That mattered because Calix generated the majority of its revenue in the U.S.—87.1% in 2013. The global fiber market was expanding, but Calix was largely tied to North America, and within North America, to the smaller carriers that the mega-vendors often treated as an afterthought.

The stock reflected that skepticism. Calix had priced its IPO at $13 in 2010, but for years the market valued it like a company trapped in a box-business future. The eventual all-time high closing price—$79.97 on December 31, 2021—was still far off, and it would only come after a transformation that, at this point in the story, hadn’t even begun.

By 2013, the question inside Calix wasn’t “How do we grow?” It was “Can this business even survive as-is?” If your entire identity is being a pure-play telecom equipment vendor—selling to smaller carriers in a world of price wars and consolidating buyers—the honest answer was starting to look like no.

Something had to change. And to make that kind of change, Calix was going to need the person who understood its original DNA—back in the driver’s seat.

IV. The Inflection Point: Carl Russo's Return & Strategic Pivot (2013-2015)

In boardrooms across Silicon Valley, there’s a familiar argument: should the founder come back when the company is in trouble? The success stories—Steve Jobs at Apple, Howard Schultz at Starbucks—become legend. The failures get quietly filed away.

In 2013, Calix needed something that dramatic. Carl Russo stepped in as CEO at a moment when the company’s core business model—selling access hardware into a brutal, price-driven market—was starting to look like a dead end.

But here’s an important nuance in the record: Russo wasn’t some long-gone founder making a sentimental comeback. He had already been Calix’s chief executive officer since December 2002 and president since December 2002. Later, he would remain CEO through September 2022 and president through January 2021. So “Russo returns” is less about a literal homecoming and more about a decision to stop trying to optimize the existing playbook—and instead rewrite it.

Russo’s career had trained him for exactly this kind of moment. He joined Cisco in 1999 after Cisco acquired Cerent Corporation, where Russo had been president and CEO. Before Cerent, he was COO at Xircom (later acquired by Intel), overseeing sales, marketing, development, and manufacturing. He also held executive roles at Network Systems Corporation (later acquired by StorageTek) and AT&T Paradyne.

That arc mattered because Russo had seen how technology companies win—and how they lose. Cerent’s $6.9 billion acquisition by Cisco didn’t happen because it was a nice little hardware business. It happened because Cerent built something meaningfully differentiated at exactly the right layer of the stack. But Russo also knew the darker truth of telecom equipment: hardware differentiation is temporary. Eventually someone matches your features, builds it cheaper, and your “innovation” turns into a line item in a procurement spreadsheet.

That’s the mental model Russo brought to Calix’s crisis. The breakthrough idea was simple, almost obvious once you say it out loud: Calix’s customers—small and mid-tier broadband service providers—needed more than boxes. They needed the stuff big carriers either build themselves or buy from giant enterprise vendors: operational software, subscriber analytics, marketing automation, and customer management. Not in a bloated, generic way, but in a form that actually fit a rural telephone cooperative or a municipal network team with a handful of employees.

That insight became the seed of what would later be Calix Cloud.

Getting there, though, meant pushing against Calix’s own identity. The company’s engineering muscle memory was hardware: silicon, optics, chassis, and ports. Telling a hardware organization the future was software wasn’t a gentle suggestion—it was heresy. And the sales motion was just as entrenched. Calix had spent years selling capital equipment. Now Russo was effectively asking the team to sell subscriptions, outcomes, and ongoing services.

His blunt framing cut through the debate: “We can’t out-hardware Huawei.” Huawei could outspend Calix on R&D, pressure pricing, and keep pace on features. If Calix stayed in a pure hardware fight, the ceiling was low and the risks were existential. But Huawei—and most traditional equipment vendors—weren’t built to win at the layer between the network and the subscriber: the software, the data, the operations, and the experience.

So the plan became audacious: turn Calix into something closer to a vertical SaaS platform company that also shipped hardware. Hardware would be the wedge—the reason operators engaged. But the platform would be the engine. The long-term lock-in wouldn’t come from proprietary specs. It would come from workflows, data, and the day-to-day systems that actually run a broadband business.

There was no painless way to start. Calix had to invest in software talent in a market dominated by giants like Google and Facebook. It had to build cloud and analytics capabilities it didn’t have. And it had to do it while still supporting and selling the hardware products that, at the time, paid the bills.

What kept the company moving through that discomfort wasn’t a spreadsheet. It was customers. When Calix talked to rural co-ops, independent telcos, and municipalities building fiber networks, the message was consistent: “We don’t just need equipment. We need help running our businesses.” These operators didn’t have big IT teams. They couldn’t justify generic enterprise stacks. They needed tools designed for their reality, at their scale, from a vendor that actually understood broadband access.

As leadership changes unfolded at the board level, Russo publicly thanked long-time chairman Don Listwin “for his guidance and contributions… as the company embarked on its long-term transformation into a software platforms, systems and services provider.” Listwin, for his part, framed the governance decision plainly: “With Calix capitalizing on major secular disruptions across the industry, the Board concluded it is in the best interests of the company to combine the roles of Chairman and CEO in order to best execute on our plan and vision for the future.”

By 2015, Calix hadn’t finished the transformation—far from it. But the direction was set. The company had a strategy that could actually beat the physics of commodity hardware, early investments underway, and leadership aligned around a pivot that would take years to prove.

Next came the hard part: building—and selling—a platform customers had never bought from Calix before.

V. The Platform Transformation: Building Calix Cloud (2016-2019)

If the strategic pivot took shape in 2013 through 2015, the years from 2016 to 2019 were when Calix started building the machine. This was the unglamorous part of reinvention: writing code, designing interfaces, retraining teams, and—hardest of all—convincing customers that the “telecom equipment vendor” they’d known for years could also deliver modern cloud software.

The centerpiece was AXOS. Calix positioned its award-winning Calix Network Innovation Platform as the foundation for moving beyond the access edge—helping broadband service providers roll out differentiated services faster, simplify operations, and create more value for subscribers, businesses, and the communities they served.

What made AXOS meaningfully different from traditional telecom gear was the architecture. It was built to be software-defined: hardware independence, service abstraction, a modular design, stateful “always on” operation, and SDN interfaces that kept data models and service interfaces consistent across technologies and systems. In other words, Calix was trying to break the old pattern where every box was its own snowflake—and every integration was a custom project.

A concrete example landed in 2017. On September 27, 2017, Calix announced that AXOS had been integrated with the OpenDaylight (ODL) Carbon release, an open-source platform used in SDN controllers. Because both ODL and AXOS supported native NETCONF/YANG interfaces, Calix said the integration was completed in days—rather than the traditional cycle that could take months depending on how much abstraction was required.

That kind of speed mattered, not just as a technical flex, but as a signal: Calix was building with modern software assumptions, while legacy vendors were often trapped under decades of accumulated complexity.

“We have invested 11 years and more than a billion dollars to build the world’s most advanced platforms to enable BSPs of all sizes to innovate and win,” said Shane Eleniak, executive vice president of products at Calix.

If AXOS was the operating system at the edge, Calix Cloud was the layer that made the platform strategy real. Calix described its Calix Broadband Platform as a unified approach—bringing together network systems, cloud management, and intelligent edge technologies to simplify operations, reduce costs, and increase value for subscribers. The promise was automation, actionable insights, and an “agent workforce” that could help service providers support subscribers more personally and grow revenue faster.

None of this was just a product shift. It was a cultural one. Hardware engineers had to get used to software release cycles and rapid iteration. Sales teams had to learn subscription economics. And the company had to internalize a new truth: the hardware sale wasn’t the finish line anymore. It was the start of the relationship.

The go-to-market challenge was just as big. Calix’s customers were used to CapEx: buy the box, depreciate it for years, call the vendor when something breaks. Cloud subscriptions meant ongoing OpEx and ongoing expectations. To get adoption, Calix had to prove continuing value—then keep proving it.

Early adopters became co-builders. Small fiber cooperatives and municipal broadband providers—too small to develop sophisticated operational software in-house—became the proving ground for Calix Cloud. They were willing to experiment because they needed these capabilities to compete, and they didn’t have many other realistic paths to get them.

Financially, the transition hurt in the ways platform transitions almost always hurt. Moving from one-time equipment revenue to recurring subscriptions can make the near-term numbers look worse even as the long-term model gets stronger. And Wall Street, accustomed to valuing Calix like a hardware vendor, didn’t have a clean mental model for what those recurring streams could become.

By 2019, though, the compounding logic was starting to show. As more customers deployed AXOS and connected into Calix Cloud, Calix could aggregate insights across thousands of networks—turning patterns into recommendations, surfacing common failure modes earlier, and enabling benchmarking that no single provider could generate alone.

And in the middle of all those customer conversations, a simple reframing emerged that would shape the next chapter: Calix’s customers weren’t just buying equipment. They were building community infrastructure.

VI. Rural Broadband Renaissance & Market Timing (2018-2023)

Sometimes strategy and timing line up so cleanly it feels scripted. For Calix, 2018 through 2023 was that moment: a decade of grinding toward a platform model met a sudden, national insistence that broadband wasn’t optional. The tailwinds were already forming before anyone had heard of COVID-19—but the pandemic turned them into a gale.

The centerpiece of that policy shift was the Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment Program, better known as BEAD. Created by the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, BEAD set aside $42.45 billion to help connect Americans to high-speed internet by funding partnerships to build broadband infrastructure—the largest federal investment in broadband to date.

BEAD didn’t appear out of nowhere. It was the peak of a longer build: programs like the Connect America Fund Phase II (CAF II) and the Rural Digital Opportunity Fund (RDOF) had already started pushing billions toward unserved and underserved communities. But BEAD was different in both scale and intent. It was an explicit national commitment to closing the digital divide.

Then came the catalyst nobody modeled.

COVID-19 made the digital divide impossible to ignore. Households with solid broadband could keep living life—working, attending school, seeing doctors—through a screen. Households without it couldn’t. When everything essential moved online at once, “slow internet” stopped being an annoyance and became a crisis. The data reflected what people were feeling: at the county level, more rural areas correlated with lower internet speeds, underscoring just how hard rural communities were being hit.

And it changed the framing. Broadband started to look like power or water: not a luxury, not even a nice-to-have, but foundational infrastructure. Students struggled to stay in class over video. Remote workers discovered their connections couldn’t handle meetings. Telemedicine surged—and then ran into the reality that it doesn’t work if the patient can’t maintain a reliable connection.

For Calix, this was the rare case where preparation matched the moment. The company had spent years building exactly what small and mid-sized broadband service providers needed: a way to deploy fiber networks and then actually operate them, market them, and manage the subscriber experience. Now those same providers were about to receive once-in-a-generation federal funding to build.

The customer base advantage mattered. While many tier-1 vendors oriented around AT&T, Verizon, and other national carriers, Calix had spent two decades embedded with regional telephone cooperatives, municipal utilities, and independent operators—the exact organizations most likely to build in rural and underserved places, and the ones positioned to benefit from federal programs. They weren’t new prospects. They were longtime customers.

Technology helped, too. Calix positioned AXOS as the only software access platform with a portfolio of systems designed to support networks across PON technologies—GPON, XGS-PON, 10G EPON, and NG-PON2. With more than 75 customers on its 10G PON solutions, adoption of next-generation networks was already moving. The practical payoff was flexibility: operators could choose the fiber approach that fit their geography, their economics, and their upgrade path—without betting their entire future on a single technology fork.

Just as important, the economics of fiber were improving. Deployment costs had been falling for years, pushing fiber-to-the-home into the realm of possibility for areas that once looked prohibitively expensive. Layer federal subsidies on top, and projects that used to die in feasibility studies started to pencil.

BEAD’s scale showed up state by state. Texas received the largest allocation at $3.3126 billion, followed by major awards to California ($1.8641 billion), Missouri ($1.7363 billion), Michigan ($1.5594 billion), and North Carolina ($1.5330 billion). The details varied, but the headline was the same everywhere: this was real money aimed at real buildouts.

For Calix, that funding wave wasn’t just an equipment opportunity. It was a platform opportunity. Every new network built with Calix systems was a chance to attach Calix Cloud—the subscription layer that turned a one-time hardware purchase into an ongoing operating system for the provider’s business. And as rural operators suddenly found themselves competing for subscribers, the platform pitch sharpened: with the right tools, you don’t have to win on price alone. You can win on experience.

That’s why the acceleration that followed mattered. It wasn’t just a good cycle. It was the market validating a bet Russo had placed nearly a decade earlier—the painful shift away from hardware-only revenue, the cultural overhaul, the years spent building software while the old model still paid the bills. When the rural broadband renaissance arrived, Calix was ready for it.

VII. The Modern Calix: Platform Economics & Business Model (2020-Present)

The Calix of 2020 through 2025 looked nothing like the telecom equipment maker from a decade earlier. The pivot finally showed up where it matters most: in the way the business ran, the way it made money, and the kind of value it could deliver to customers beyond the box.

The company’s more recent results reflected that shift. In Q3 2025, Calix reported record revenue of $265 million, up 10% sequentially. Earnings per share came in at $0.44, well ahead of the $0.34 forecast.

Just as telling was profitability. Calix posted its seventh consecutive quarter of gross margin improvement, reaching a non-GAAP gross margin of 57.7%. For a company with hardware roots, that’s a very different margin profile—and it underscored what the transformation was really buying them: more software and services in the mix, and less dependence on one-time equipment cycles.

Visibility improved too. At the end of Q3 2025, remaining performance obligations, or RPOs—contracted future revenue—were $354.6 million. That was up 2% from the prior quarter and up 20% from the same quarter a year earlier, giving the business a clearer “what’s already sold” runway than a traditional hardware vendor usually gets.

By this point, Calix wasn’t really selling products so much as running a flywheel. The wedge was still equipment: when a broadband service provider deployed Calix AXOS systems, it opened the door to Calix Cloud. That cloud platform included Calix Engagement Cloud, Calix Operations Cloud, and Calix Service Cloud—designed to surface role-based insights and help broadband experience providers anticipate needs and target new revenue-generating services.

Then Calix layered in managed services aimed at what subscribers and communities actually feel day to day. SmartLife managed services included SmartHome services and applications to enhance, operate, and secure the connected experience in the home—Wi-Fi, content controls, network security, connected cameras, and social media monitoring. SmartTown aimed to make community Wi-Fi a ubiquitous, secure, managed experience across a provider’s footprint. And SmartBiz targeted the networking and productivity needs of small business owners.

This is where the land-and-expand motion became the growth engine. A customer might start by buying AXOS for a fiber build. Once they were connected to Calix Cloud, they could unlock operational wins like reduced truck rolls, faster troubleshooting, and better subscriber insights. That often led to more cloud modules being adopted. And from there, managed services like SmartHome or SmartBiz could follow—creating new revenue streams for the broadband provider, and recurring revenue for Calix.

The customer base continued to grow alongside that expansion. Calix added 20 new customers in the third quarter. And growth wasn’t just about signing new operators—it also came from expanding platform adoption within existing accounts and increasing the number of subscribers served on those customers’ networks.

Calix also leaned into AI as the next step of the platform thesis. The company said it was aiming to simplify operations and drive customer growth with a strategic partnership with Google for its third-generation platform. Calix also pointed to product investment over the prior two years enabling it to take advantage of artificial intelligence by launching the Calix Agent Workforce.

That AI layer signaled where the platform could go next: automating higher-level work for operators, from operational efficiency to customer growth. With agentic AI capabilities embedded in the platform, Calix positioned itself to help customers handle more complex tasks through automation—improving efficiency and supporting growth—while keeping the system integrated into the workflows operators already used.

Importantly, the next major funding wave was still ahead. Calix expected the BEAD program to begin contributing to revenue starting in 2026, with the potential to drive more network builds and subscriber additions. Even then, Calix said it had been deliberately conservative about incorporating BEAD into guidance.

Financially, Calix ended the quarter with record cash and investments of $340 million, up $41 million sequentially. That kind of balance sheet gave the company real options—whether that meant investing through macro headwinds, funding internal product development, or pursuing acquisitions.

And through all of this, Calix argued that culture remained a differentiator. The company emphasized its internal culture and pointed to a 4.9/5-star rating, 98% overall approval, and 100% CEO approval on Glassdoor. In a world where the transformation lives or dies by attracting and retaining software talent, that kind of signal mattered.

VIII. The Competitive Landscape & Strategic Positioning

To understand Calix’s competitive position, you have to start with a simple premise: Calix no longer competes in just one market. It sells hardware, yes—but it also sells cloud software, managed services, and an operating model. That overlap makes “who are their competitors?” a trick question, because the answer depends on which part of the stack you’re looking at.

On the networking and access equipment side, the list looks familiar: Cisco Systems, ADTRAN, Nokia, Juniper Networks, and CommScope, plus global-scale players like Huawei and ZTE where they’re allowed to compete. In the pure-play broadband access lane, ADTRAN is the most direct head-to-head rival. It sells into the same service provider world with a similar promise: better access infrastructure, improved performance, and reliable operations.

But if you reduce Calix to another equipment vendor in a price fight, you miss the entire point of the last decade. Calix now competes in three categories at once:

Traditional Equipment Competition: In hardware, Calix is up against vendors with enormous manufacturing scale and deep customer footprints. The classic dynamic here is brutal: feature parity arrives fast, and pricing pressure never stops. Calix’s differentiation is that its access gear is built around a software-defined, cloud-managed approach—positioning the “box” less as a standalone product and more as the on-ramp to a broader system.

Cloud BSS/OSS Competition: Once you move up into Calix Cloud, the competitive set shifts. Now you’re in the neighborhood of large horizontal platforms like Salesforce and ServiceNow, along with specialized telecom software vendors. The catch is that generic platforms don’t come preloaded with broadband-specific context. They can run workflows, but they don’t inherently know what a regional broadband provider needs to do tomorrow morning to improve service quality or reduce operational pain. Calix is betting that this domain depth—built over decades with exactly these operators—matters.

Vertical SaaS Analog: The closest mental model might not be telecom at all. It’s vertical SaaS: companies like Veeva in life sciences, Procore in construction, or Toast in restaurants—platforms that win because they’re designed around one industry’s specific workflows and economics. Calix is trying to be that kind of platform for broadband service providers.

That’s where the company’s sweet spot comes into focus: “too small for giants, too sophisticated for startups.” The biggest carriers can afford to build a lot of this themselves. The tiniest providers can limp along with manual processes. But there’s a wide middle—thousands of regional operators—who need real capabilities without enterprise bloat. That’s the segment Calix was built to serve, and it’s why the platform story isn’t just about technology. It’s about fit.

It also helps explain why incumbents haven’t simply copied the model. This is what Hamilton Helmer calls counter-positioning: if you’re a legacy equipment vendor, shifting to a platform business can undermine the very economics that keep your hardware engine running. It’s hard to enthusiastically sell the thing that changes customers’ buying behavior away from big, periodic box purchases. Even if the strategy is obvious, the organizational antibodies are real.

Competitors have noticed. ADTRAN, for example, has pushed its own platform capabilities through Mosaic One, signaling that the battle is no longer just about ports and speeds—it’s about who owns management, analytics, and the day-to-day operating layer. But keeping up here is more than feature matching. It requires product integration, data leverage, and a sales motion that can sell subscriptions and outcomes, not just hardware refresh cycles.

Then there’s the obvious question: why hasn’t someone just bought Calix? With a market capitalization of roughly $4 billion, it’s not too large for a major telecom or software player to acquire. And yet, no deal has happened. One possibility is that would-be acquirers understand what makes Calix valuable—and fragile: trust in a niche community, long customer relationships, and a culture that pulled off a rare hardware-to-platform transformation. Those are exactly the kinds of assets that can degrade quickly inside a big merger.

Finally, the threats. Low-earth-orbit satellite broadband from Starlink—and eventually Amazon’s Project Kuiper—could take share in rural areas where fiber is expensive or slow to deploy. The policy conversation around BEAD has already started making room for more satellite options. Chinese vendors still pressure pricing in markets where they’re allowed to compete. And like every infrastructure cycle, the fiber buildout won’t expand at the same pace forever. When deployment matures, the question shifts from “how many new networks get built?” to “who owns the ongoing platform and subscriber experience on the networks that already exist?”

IX. Playbook: Business & Strategic Lessons

Calix’s arc is a telecom story, but the playbook travels. Strip away the acronyms and fiber talk, and what’s left is a set of lessons about reinvention, customer choice, and how to build a business that compounds instead of getting squeezed.

Lesson 1: Sometimes the Only Way Forward is Through Radical Reinvention

By 2013, Calix was staring at an existential fork in the road: stay a hardware vendor in a market that was steadily commoditizing, or rebuild the company around a different kind of value. There wasn’t a comfortable middle. The pivot to a platform model meant unlearning what had made Calix “Calix” in the first place—and replacing it with a new identity.

That kind of reinvention is rare because it fights the natural immune system of an organization. Processes, incentives, and pride all pull you back to what you already know how to do. Calix made it through because leadership—especially Carl Russo—had enough credibility to keep pushing even when the outcome was uncertain and the payoff was years away.

Lesson 2: Find Customers Incumbents Ignore—Then Build What They Actually Need

Calix built for tier-2 and tier-3 broadband providers: too small to be strategic to the global telecom giants that chase the biggest carriers. The industry’s spotlight was on AT&T and Verizon. Calix’s customers were the regional providers and co-ops who still had to compete, but didn’t have the budgets, staff, or bargaining power to get tailored solutions from massive vendors.

That “ignored” segment ended up being the perfect foundation for a platform business. These operators didn’t just want better boxes. They needed help running the business: operations software, analytics, and tools to improve the subscriber experience. And because few others were building for them, solving their real problems created loyalty and switching costs that commodity hardware alone could never generate.

Lesson 3: Platform Transformations Require Patient Capital and Conviction Through Pain

Calix’s transition wasn’t a quick pivot. It was a long rebuild. Over 13 years, the company invested $1.3 billion to move from a hardware company toward an end-to-end cloud-and-software platform model. For much of that journey, the financial results didn’t neatly validate the strategy. The company had to keep investing before the market could clearly see what it was becoming.

That’s the price of transformation: you often look worse before you look different. It requires long-term-oriented shareholders—and leaders willing to endure the uncomfortable stretch where you’re funding the future while the past is still paying the bills.

Lesson 4: Macro Tailwinds (Policy, COVID) Can Validate Contrarian Bets

Calix didn’t start its platform journey because it foresaw a pandemic or a federal broadband funding wave. It couldn’t have predicted COVID-19 or the $42.5 billion BEAD program. But when those tailwinds hit, Calix was positioned exactly where it needed to be: serving rural and regional providers just as unprecedented funding and urgency flowed toward rural buildouts.

The broader lesson: contrarian positioning looks unnecessary—until the world changes. The payoff comes from building the capability before the tailwinds arrive, not after.

Lesson 5: Vertical SaaS + Hardware Integration = Powerful Combo in B2B

Calix’s advantage isn’t “software” or “hardware.” It’s the combination: industry-specific software tightly integrated with the network systems it manages. That integration creates real defensibility—data dependencies, operational embed, and domain-specific workflows that are painful to replace. In Calix’s case, the integration isn’t an add-on. It is the product.

Lesson 6: Founder-CEO Returning to Save the Company—When Does It Work?

Calix is a reminder that “founder return” isn’t magic. What matters is whether the leader has the context and stamina for a multi-year rewrite. Russo’s long tenure as CEO (2002 through 2022, with ongoing board involvement) gave the company unusual continuity. When the leader understands the company’s original DNA and the industry’s direction—and has the internal trust to force change—transformations that would stall under an outsider can actually get finished.

Lesson 7: Build Flywheels Where Products Sell Platforms, Platforms Sell Products

Calix built a compounding machine: equipment deployments open the door to cloud adoption, cloud adoption enables managed services, and managed services generate data and outcomes that make the platform stronger. Each layer makes the next one easier to sell, and each reinforces switching costs. That’s what a flywheel looks like in an industry that used to be defined by one-off box sales.

Capital Allocation Choices: Calix has leaned into R&D over acquisitions or aggressive shareholder returns, signaling conviction that differentiation would come from building—not buying. It also maintained a strong balance sheet to ride out industry cycles, rather than using debt-fueled consolidation the way many telecom equipment vendors have, often with painful consequences later.

X. Power Analysis: Hamilton's 7 Powers & Porter's 5 Forces

Hamilton's 7 Powers Framework

1. Scale Economics (Moderate)

On the cloud side of the house, Calix starts to look like a classic scale business: big R&D investments get spread across more customers, aggregated data sharpens the insights, and cloud infrastructure costs get amortized as more subscribers run through the platform. Hardware is different. Manufacturing and supply chains don’t scale with the same clean curve, so the “more customers = better economics” effect is less pronounced there.

2. Network Effects (Weak-to-Moderate)

Calix’s closest thing to a network effect is data. When you can see patterns across thousands of networks, you can generate insights no single operator could produce alone. SmartTown Alliance pushes further, letting broadband service providers keep subscribers connected as they move between towns and cities—an early hint of value that increases as participation grows. Still, the core proposition doesn’t require everyone else to be on it. Most customers get value even in isolation, which keeps this power in the “emerging” category.

3. Counter-Positioning (Strong)

This is the heart of the Calix story. Legacy equipment vendors can’t easily pivot to a platform model without kneecapping their own economics. Their organizations are optimized for boxes: sales comp, quotas, product roadmaps, margin expectations. Asking that machine to sell subscriptions and outcomes means rewriting incentives and accepting near-term disruption. Even when incumbents see the shift, the internal resistance is structural, not philosophical.

4. Switching Costs (Very Strong)

Once an operator builds on AXOS and ties day-to-day operations into Calix Cloud, “switching vendors” isn’t a clean procurement decision—it’s a high-risk operational event. Data has to move, workflows have to be rebuilt, people have to be retrained, and service disruption becomes a real fear. The growth in RPOs to about $355 million is the financial fingerprint of that reality: customers aren’t just buying products, they’re signing up for multi-year commitments.

5. Branding (Weak-to-Moderate)

Calix isn’t a consumer brand, and it doesn’t get to charge “premium pricing” because a household recognizes the logo. But inside the tier-2 and tier-3 operator world, it has something that matters more: a trust-based reputation built over decades. In infrastructure, that kind of credibility can be a quiet advantage—even if it doesn’t look like Apple-style branding.

6. Cornered Resource (Moderate)

Calix’s real scarce asset is deep, specific domain knowledge: what small and mid-sized broadband operators actually need, what they can afford, and what they can realistically deploy with limited teams. The customer relationships and co-innovation partnerships built over roughly twenty-five years aren’t easily copied or bought off the shelf.

7. Process Power (Moderate)

A decade-plus of building an integrated hardware-and-cloud platform creates institutional muscle memory: how to ship edge systems that work cleanly with cloud software, how to sell and support subscriptions, how to run product cycles like a software company while still living in the physical world. That’s process power—hard to see from the outside, and hard to replicate quickly.

Primary Powers: Switching Costs, Counter-Positioning

Emerging Powers: Scale Economics (as cloud ARR grows)

Porter's 5 Forces

1. Threat of New Entrants (Low-to-Moderate)

If this were only hardware, entry would be brutal: high R&D costs, long qualification cycles, and relationships that take years to earn. Cloud software lowers the barrier—well-funded teams can build platforms faster than they can build optics and chassis. But Calix’s integrated hardware+software approach raises the bar again, because a new entrant has to win both the technical layer and the operational layer, and then convince conservative operators to bet on them.

2. Bargaining Power of Suppliers (Moderate)

The 2021–2022 chip shortages were a reminder that component suppliers can have real leverage, especially when availability tightens globally. Calix can diversify some sourcing, but it’s still constrained by the realities of semiconductors and optics.

3. Bargaining Power of Buyers (Moderate-to-High)

These customers are regional operators. They’re sophisticated, they’re price-conscious, and they negotiate hard. But once Calix is embedded, switching costs blunt that power—buyers have leverage at the point of purchase, not as much after the platform becomes operationally central. Subsidy programs also matter here: when buildouts are funded, the conversation often shifts away from pure lowest-price bidding.

4. Threat of Substitutes (Moderate)

Fiber isn’t the only way to deliver broadband. Fixed wireless access can be “good enough” in some markets, and low-earth-orbit satellite broadband—like Starlink, and eventually Amazon Kuiper—can be compelling where density is low and construction is hard. The move toward more technology-neutral BEAD policy, including more satellite options, underlines that substitutes aren’t theoretical.

5. Competitive Rivalry (High)

Rivalry stays intense. The market includes global giants like Nokia and Huawei (where allowed), plus regional specialists like ADTRAN and DZS. Hardware pricing pressure never really goes away. Calix’s platform differentiation changes the basis of competition somewhat, but it doesn’t eliminate it—especially as others push their own platform narratives.

Overall Industry Attractiveness: Moderate, and improving as platform economics take hold. The more the category shifts from one-time hardware cycles toward recurring software and services, the more room there is for margin expansion—if you can execute the transition without getting crushed in the meantime.

XI. Bear vs. Bull Case

Bull Case

The bull case for Calix is basically a bet that the company’s timing and business model are finally lined up—and that the market is still underestimating just how durable that combination can be.

Fiber buildout still has a long runway in North America. Even after years of progress, millions of households still don’t have adequate broadband. BEAD alone commits roughly $42.5 billion in federal funding, and states and localities are layering on additional programs. The point isn’t the exact number—it’s that the U.S. has made broadband a national infrastructure priority, and fiber remains the gold standard for delivering it.

The platform model may be earlier than it looks. Calix has spent more than a decade trying to climb out of the hardware trap, and its more recent performance suggests the shift is starting to show up in the financial engine. Record Q3 2025 revenue of $265 million and a 57.7% gross margin are the kind of signals you expect when software and services are becoming a larger part of the mix. If that mix shift keeps compounding, margin expansion can continue.

Government funding creates unusual demand visibility. Calix expects BEAD to begin contributing to revenue starting in 2026, and the program could run for five to eight years. For a company that used to live and die by hardware cycles, that’s a very different backdrop: more planned builds, more predictable project pipelines, and a longer window to attach the platform.

Switching costs can turn growth into annuity-like revenue. When operators run day-to-day workflows through Calix Cloud, the relationship gets stickier than a typical equipment vendor relationship. The $355 million in RPOs—up 20% year-over-year—is the clearest proof point that customers are signing up for multi-year commitments, not just buying a box and moving on.

The market may still be valuing the “old” Calix. If investors keep mentally filing Calix under “telecom equipment,” they may not give the company credit for looking more like a vertical SaaS platform—one with high-50s gross margins and growing recurring revenue. If that perception shifts, valuation could expand even without dramatic changes to the underlying business.

International expansion remains largely untapped. The U.S. made up 94% of Q3 2025 revenue. If Calix can translate its platform playbook to more international markets as global broadband buildouts accelerate, that becomes a meaningful second act.

Bear Case

The bear case is the reminder that Calix’s tailwinds aren’t guaranteed forever—and that the company still operates in an industry that can turn unforgiving fast.

Fiber buildouts are cyclical, and subsidies don’t last forever. BEAD will eventually be spent. If broadband infrastructure funding isn’t renewed, demand could fall back toward a more normal cycle. In that scenario, the risk is that Calix’s growth has been pulled forward by a once-in-a-generation policy moment.

The customer base can be fragile in a downturn. Calix’s sweet spot is small and mid-tier providers. Many are operationally lean and financially constrained. A recession can mean delayed builds, strained budgets, and in the worst case, bankruptcies—turning project pipelines into revenue headwinds and raising credit risk.

Platform adoption could level off. Not every equipment customer will adopt the full Calix Cloud suite. If attach rates stall, the “platform” story becomes less powerful, and Calix is left with more exposure to the lower-margin, more competitive hardware side of the business.

Low-cost Asian hardware competition is real—especially internationally. Vendors like Huawei and ZTE can compete aggressively on price where they’re permitted. Even if U.S. geopolitical constraints limit their presence domestically, they can shape pricing dynamics in many international markets Calix might target.

Substitutes keep improving. Fiber is the best long-term infrastructure in many cases, but it’s not the only option. Satellite broadband players like Starlink continue to improve, and 5G-based fixed wireless access keeps getting better. If those options become “good enough” for more rural deployments, it could pressure long-term fiber demand—especially at the margin.

The tier-2/3 focus naturally caps the TAM. Calix’s positioning is part of its advantage, but it also limits the ceiling. The largest carriers have the biggest budgets and often build or buy differently. If Calix can’t expand its reach without losing focus, growth could eventually slow as its core segment matures.

Key Metrics to Watch

If you want to track whether Calix is really becoming what it claims—a platform company, not just an equipment vendor—three metrics do most of the work.

1. Cloud/Platform Revenue Mix and Growth Rate: This is the heartbeat of the transformation. Watch how much revenue is coming from recurring cloud and managed services versus one-time equipment sales, and how fast those recurring lines are growing. That mix shift drives both margins and how the market values the company.

2. Remaining Performance Obligations (RPO): RPO is the “already sold” backlog of contracted future revenue, largely from cloud and managed services. If RPO keeps growing, it signals stickiness, multi-year commitments, and better visibility than a traditional hardware business. Calix ended Q3 2025 with RPOs of $354.6 million, up 20% year-over-year.

3. Gross Margin Trajectory: Gross margin is the simplest proxy for how much of the business is becoming software-like. Calix’s non-GAAP gross margin reached 57.7% after seven consecutive quarters of improvement. If margins continue climbing toward 60%+, that’s strong evidence the platform economics are taking hold.

Together, these tell you whether the core bet is working: that Calix can keep escaping the commodity physics of hardware by owning the operating layer—and the subscriber experience—on top of the network.

XII. Epilogue & Looking Forward

By late 2025, Calix sat at a new kind of inflection point. The long, grinding transformation that began more than a decade earlier had worked. The company posted record Q3 2025 revenue of $265 million with a 57.7% gross margin—numbers that would have sounded like science fiction back when Calix was fighting for survival as a hardware-only vendor in 2013.

The leadership baton had already passed. Michael Weening, who succeeded Carl Russo as CEO in September 2022, kept the platform strategy moving while putting his own stamp on it. Before taking the top job, Weening served as Calix’s president and chief operating officer. His résumé included senior roles at Salesforce and Microsoft, focused on customer success and global sales—exactly the kind of operating background you’d want when the product is no longer just a box, but a platform you have to land, expand, and keep proving valuable every month.

If the last chapter was “become a platform,” the next one looked like “make it intelligent.” Calix introduced the Calix Agent Workforce, integrating AI capabilities into the platform, and it pointed to a strategic partnership with Google for its third-generation platform. The promise wasn’t AI for the sake of buzzwords. It was automation that could take real work off the plates of lean broadband teams—reducing costs, improving subscriber experiences, and opening up new managed service opportunities.

Meanwhile, the near-term technology cycle kept turning. Calix unveiled its first Wi-Fi 7 systems, positioned as the next step in its GigaSpire and GigaPro lineup and integrated with the Calix Broadband Platform to keep deployment simple. At the network level, 10G fiber remained part of the same story: new capability drives upgrades, upgrades create opportunities to pull more customers deeper into the cloud layer, and the platform attaches to the lifecycle.

The most important demand wave, though, was still in front of them. Calix expected BEAD to begin contributing to revenue starting in 2026, potentially driving more network builds and more subscribers on customer networks. And the company said it had been conservative about including BEAD in guidance—a way of signaling that even after years of proving the pivot, telecom is still a business where you don’t declare victory until the purchase orders arrive.

Zoom out, and Calix’s story points to a bigger question than any one quarter: can vertical SaaS platforms exist in places we assume are pure commodity? Telecom equipment is supposed to be a knife fight where scale wins and everybody else gets squeezed. Calix showed a different path: pick the customers the giants don’t prioritize, build around their workflows, and use platforms—not ports—as the source of differentiation.

There’s also founder wisdom embedded in the arc. Russo watched the company he helped build slide toward an existential crisis, then spent years forcing a transformation while the market doubted. When he assumed the chairman role, he publicly thanked long-time chairman Don Listwin “for his guidance and contributions… as the company embarked on its long-term transformation into a software platforms, systems and services provider.” It reads like a polite quote. In context, it’s a quiet admission of how long and difficult the climb really was.

In an era dominated by quarterly thinking, Calix became a reminder of what can happen when leadership has conviction, capital has patience, and the market eventually shifts in your direction. The unsexy infrastructure that enables modern life—fiber under rural highways, cloud software running subscriber experiences, and automation reducing the burden on small operator teams—rarely gets the spotlight. But it’s increasingly the difference between communities that can participate in the modern economy and communities that can’t.

Calix’s story isn’t finished. The transformation that began in 2013 is still evolving through AI, international expansion, and new customer segments. But the central thesis has already been validated: a telecom equipment maker can become a platform company—and, in doing so, build durable advantage in a place where it once looked impossible.

XIII. Further Reading & Resources

Top 10 Long-Form Resources:

-

Calix Investor Relations - Annual reports from 2013 to 2024, told in management’s own words. If you want the clearest paper trail of the shift from “boxes” to platform subscriptions, this is where it shows up—quarter by quarter, line item by line item.

-

"The Platform Economy" by Geoffrey Parker, Marshall Van Alstyne, and Sangeet Paul Choudary - A solid, accessible framework for what Calix was attempting: moving from a pipeline business (sell hardware once) to a platform business (keep delivering value, keep getting paid).

-

FCC National Broadband Plan and Broadband Maps - The policy and measurement backbone for the rural broadband story: where coverage gaps actually are, how they’re defined, and why federal programs aimed so much money at closing them.

-

Light Reading Industry Analysis - One of the best places to follow the broadband equipment world in real time, including the competitive chess match between Calix, ADTRAN, Nokia, and others.

-

Calix Customer Success Stories - Case studies from operators using the platform, hosted on Calix’s website. These are the “ground truth” version of the pitch: what changed operationally, what improved for subscribers, and why customers stuck with the platform.

-

"Good Strategy/Bad Strategy" by Richard Rumelt - Useful for separating real strategy from wishful thinking. Calix’s transformation is a great example to test Rumelt’s ideas: diagnosis, guiding policy, and coherent action.

-

Telecom Ramblings Blog - A long-running industry blog with sharp, opinionated coverage of fiber buildouts, network economics, and the realities that never make it into glossy investor decks.

-

Calix SEC Filings - The primary source material: S-1 and prospectus documents, plus quarterly and annual filings. If you want to track the transformation with precision—revenue mix, risk factors, customer concentration—this is the record.

-

Harvard Business Review: "Platform Revolution" - More academic, but helpful for understanding how platforms create value differently than product businesses—and why that difference matters when you’re trying to escape commoditization.

-

Fiber Broadband Association Reports - Market data and forecasts that help put Calix’s world in context: the pace of fiber deployment, the long-term runway, and how big the opportunity could be as buildouts continue.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music