Boyd Gaming: From Downtown Las Vegas to Coast-to-Coast Casino Empire

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

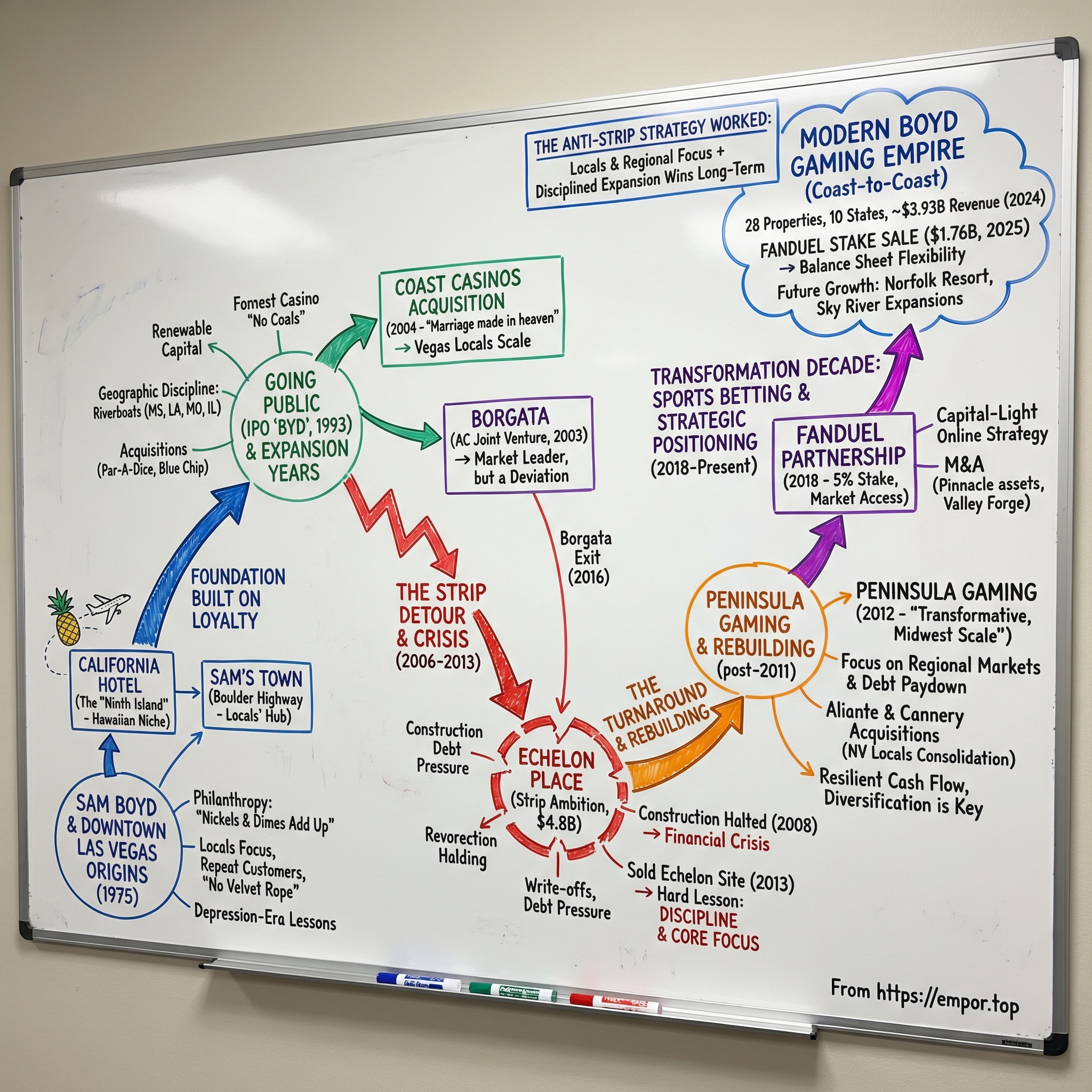

Picture Las Vegas in 1975. Not the glossy Strip we all recognize today, but downtown—Fremont Street’s rougher, louder cousin—where neon buzzed over low-rise casinos and customers arrived by Greyhound, not private jet. In that world, a former carnival barker named Sam Boyd was quietly building something that would prove far more durable than the flash a few miles south.

Today, Boyd Gaming operates 28 properties across 10 states and brings in roughly $3.8 billion-plus a year. But the real hook is how it got there. Boyd didn’t win by chasing the same dream everyone else chased: high-rollers, tourists, and ever-bigger spectacle. It won by doing the opposite—by perfecting the “neighborhood casino.” The kind of place where locals come for a reliable meal, a few hours on the slot floor, maybe a movie, and a familiar face behind the counter. No velvet rope. No attitude. Just a business built on repeat customers and small habits that add up.

This is also a family story—three generations, half a century, and a front-row seat to the modern American gaming industry as it spread state by state. On January 1, 2025, Boyd Gaming hit a milestone: 50 years in business, from a single downtown Las Vegas property to one of the largest and most respected gaming operators in the country.

In 2024, Boyd reported $3.93 billion in revenue, up a little over 5% from 2023. It ran those 28 gaming entertainment properties across 10 states, managed a tribal casino in northern California, and owned Boyd Interactive—its B2B and B2C online casino arm. And it held a 5% equity stake in FanDuel Group, the nation’s leading sports-betting operator.

So here’s the deceptively simple question at the center of this story: in an industry addicted to spectacle—mega-resorts, billion-dollar builds, and “whales” who can drop a fortune in a weekend—what happens when you ignore all of that and build for the person who lives twenty minutes away, wants a good steak, and likes a Tuesday night session of video poker?

The answer is a company with surprisingly resilient cash flow, decades of survival through multiple industry shocks—and one near-fatal detour when Boyd tried to play the Strip’s game and almost lost everything. This is the story of Boyd Gaming: the anti-Strip strategy that actually worked, the Echelon disaster that nearly broke the business, and the hard-earned lessons about discipline, diversification, and knowing exactly who your customer is.

II. The Boyd Family & Downtown Las Vegas Origins

To understand Boyd Gaming, you have to start with Sam Boyd. And to understand Sam, you have to understand what it meant to learn business during the Depression—standing behind a carnival game in Long Beach, watching people scrape together a few coins for a moment of fun.

Samuel A. Boyd was born on April 23, 1910, in Enid, Oklahoma. He got into gambling young. In 1928, he was running bingo games on a gambling ship off the coast of Long Beach, California. That wasn’t glamorous work. But it was a front-row education in human nature: why people play, what makes them come back, and how small profits—repeated a thousand times—turn into a real business.

In the 1930s, Boyd worked in casino operations across southern California and Hawaii to support his young family. He wasn’t chasing whales. He was watching the “regulars.” The Depression taught him that nickels and dimes add up, that relationships matter more than one-off transactions, and that the customer with a few dollars today might be the customer with a few dollars again next week. Those lessons became the quiet philosophy that Boyd Gaming would later scale into a national strategy.

Just before the U.S. entered World War II in 1941, Sam moved his family to Las Vegas with $80 in his pocket. He started where nearly everyone in the business starts: on the floor. Dealer. Pit boss. Shift boss. Over time, he saved enough to buy a small interest in the Sahara Hotel, then moved downtown to become general manager and a partner at The Mint. At The Mint, he built a reputation for marketing and operating innovations that actually moved the needle—less about flash, more about getting people in the door and making sure they had a reason to return.

When The Mint was sold in 1968, Sam didn’t retire. He went to work managing the Eldorado Casino in downtown Henderson, a property he had acquired earlier, in 1962, with his son Bill Boyd.

Bill’s path into the business was anything but inevitable. Sam had encouraged him to build a career outside of gaming, so Bill served a short stint in the U.S. Army in the mid-1950s and then went to law school. By the early 1960s, Bill—along with law partners Myron Leavitt and John Brennan—had become one of Las Vegas’ best-known attorneys. His entry into the family casino business was practical: he earned his first interest in the Eldorado by doing all of its legal work.

The company that would become Boyd Gaming was born on January 1, 1975, when Sam and Bill founded the business to develop and operate the California Hotel and Casino in downtown Las Vegas. Bill left the legal profession after 15 years to work full-time at the Cal.

The problem was the Cal’s location. It sat on Ogden Street—away from the foot traffic of Fremont Street—and it struggled immediately. The original plan had been straightforward: attract visitors from Southern California. The name “California Hotel” wasn’t subtle, and neither were the gold rush-themed murals inside. But after a rough first year with little business, the Boyds did something that would become a defining trait of the company: they stopped insisting the market should behave the way they wanted, and instead listened to what the market was telling them.

Sam had lived in Honolulu years earlier and had worked for a Japanese man named Hisakichi Hisanaga at Palace Amusements. Through those relationships—and through organizing bingo games—he learned something crucial: locals loved to gamble. And at the time, Hawaii residents were flying to Reno to gamble because it was cheaper than flying to Las Vegas.

So the Boyds pivoted hard toward Hawaii. They leaned into their cultural knowledge and personal connections, worked with Hawaiian travel agents, and built package deals that made Las Vegas the easy choice. The approach was intensely relationship-driven. David Strow, vice president of corporate communications, later described the Boyds showing up to meetings with a highly specific peace offering: cases of Coors beer, a favorite in Hawaii that was hard to find. They’d load it in the trunk, stop at travel agencies, and walk in with a case on each shoulder.

It worked—fast.

Before long, the Cal had built a Hawaiian customer base that surpassed the combined Hawaiian business of Strip properties. Las Vegas started getting called Hawaii’s “ninth island,” not just as a vacation destination, but as a meeting ground—where families and old friends could see each other, eat familiar food, and feel at home.

The scale of the niche was startling. By 1985, Hawaiians made up 70 percent of the California’s clientele. A decade later, the property was receiving about 200,000 annual visitors from Hawaii. By 2006, Boyd was charting roughly 10,000 Hawaiian tourists to Las Vegas each month, and they accounted for around 80 percent of the California’s guests.

And it wasn’t just tourism. Over time, Hawaiians began moving to Las Vegas to work at the Cal and build a community. Eventually, some 40,000 Native Hawaiians established residency in the valley. Las Vegas now has the second-largest population of Hawaiians in the country, behind only Honolulu. “Ninth island” wasn’t just a nickname—it became a lived reality.

The California Hotel didn’t just save a struggling casino. It revealed the Boyd playbook in its purest form: find an underserved audience, build trust through real relationships, deliver obvious value, and let loyalty compound in a way competitors can’t easily copy.

Boyd’s next move made that playbook even clearer. In 1979, the company opened Sam’s Town Hotel and Gambling Hall—Sam’s Town Las Vegas—on Boulder Highway at Nellis Boulevard. It was one of the first true “locals” properties in the valley and helped kick off what later became the Boulder Strip.

Sam’s Town was named for Sam Boyd himself, and the strategy was the same idea in a new form: don’t build for the once-a-year tourist. Build for the person who lives nearby.

Sam Boyd’s philosophy was deceptively simple: take care of locals, treat employees like family, and remember that nickels and dimes add up. He was also known for giving back to the community. In the 1960s, he helped introduce the United Way and the Boys and Girls Clubs to Las Vegas. He was an early proponent of diversity in the gaming industry, becoming one of the first casino operators to hire women and African-Americans as dealers.

This locals-first approach mattered because it rewired the economics of a casino business. Strip operators could spend billions to chase tourists who might visit once a year—or once in a lifetime. Boyd was cultivating customers within a short drive who could become weekly regulars. Over decades, the repeat business from a satisfied local could dwarf the unpredictable revenue from a one-time visitor.

And that mindset—quietly, steadily—set the foundation for everything Boyd would become.

III. Going Public & The Expansion Years

Sam Boyd died on January 15, 1993, at 82. Bill Boyd stepped into the CEO role, and with him came something Boyd would lean on for decades: continuity. This wasn’t a revolution; it was a handoff. Bill had already spent years in the business, and the culture Sam built—take care of the customer, take care of the employee, let the small stuff compound—didn’t change.

What did change was the company’s toolkit.

That July, Boyd Gaming went public, listing on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker “BYD.” The IPO didn’t just bring in money. It gave Boyd a renewable source of capital, and a new kind of credibility, right as the biggest land grab in modern American gaming was getting underway.

Because in the early 1990s, gambling stopped being “that thing they do in Nevada” and started becoming a state-by-state budget solution. Legislatures were under pressure, tax bases were tight, and Nevada’s gaming revenue looked awfully attractive from afar. Riverboat casinos popped up along the Mississippi and in the Midwest. Native American gaming expanded after federal legislation. And suddenly, the map of where you could legally gamble began spreading fast.

Boyd’s strategy in this era was refreshingly consistent: go where legalization goes, aim at the middle of the market, and don’t get dragged into the Strip’s arms race. The company’s first step outside Nevada came in 1994 with Sam’s Town Tunica in Mississippi, in a market just south of Memphis that was quickly becoming a riverboat gaming hotspot. And crucially, it was a drive-in market—most customers came from within a short radius—which meant Boyd’s locals-style playbook worked.

From there, expansion was steady and geographically disciplined. Boyd entered and built positions in riverboat markets across the South and Midwest, including Mississippi, Louisiana, Missouri, and Illinois—jurisdictions that were newly friendly to regulated gaming.

Back home, Boyd consolidated too. In 1993, the company acquired the Eldorado and Jokers Wild, properties that had previously been owned directly by the Boyd family. Later that year it picked up the bankrupt Main Street Station Hotel and Casino and Brewery downtown.

As the regional build-out continued, Boyd took on more deals and openings: Treasure Chest Casino in Kenner, Louisiana (Boyd initially owned 15% when it opened in 1994, then acquired it outright in 1997); Sam’s Town Kansas City (opened in 1995 and later closed in 1998); and a bigger bet in Illinois with Par-A-Dice in East Peoria. Boyd acquired Par-A-Dice in December 1996 for $163 million in cash from the local investor group that had opened it in 1991.

Then, in 1999, Boyd added its 12th property with Blue Chip Casino in Michigan City, Indiana. Opened in 1997, Blue Chip was a three-deck riverboat with 37,000 square feet of gaming space and two restaurants—one of just five casino riverboats authorized to operate in Indiana along Lake Michigan.

Underneath all these dots on the map was a single operating idea Boyd kept refining: build casinos that feel like part of people’s routines. Not tourist magnets—community hubs. Slots, value-forward restaurants, bowling, movies, live entertainment. At Sam’s Town Las Vegas, for example, gaming, bowling, and entertainment turned the property into a social center, and its food-and-beverage value and slot marketing programs helped drive repeat business.

By the early 2000s, Boyd had become a very different company than it had been at Sam’s death. It entered 1993 with four properties. By the decade’s end, it had tripled that count and, by 2000, had pushed annual revenues past $2 billion.

And then Boyd made its most ambitious move yet—one that, on paper, broke every “anti-Strip” instinct the company had built.

In 2003, Boyd opened the $1.1 billion Borgata Hotel Casino in Atlantic City, New Jersey, in a joint venture with MGM Resorts International. Borgata was the first new casino in Atlantic City in 13 years, and it didn’t just do well—it quickly became the market’s leading property by gaming revenue.

With Borgata up and running, Boyd turned right back to its core: Las Vegas locals. In 2004, the company announced it would acquire Coast Casinos, one of the biggest locals operators in the city. The deal closed on July 1, 2004, for $1.3 billion and added four Las Vegas properties to Boyd’s portfolio: Suncoast, Gold Coast, the Orleans, and Barbary Coast.

The logic was straightforward and powerful. Boyd already had Sam’s Town, a locals landmark. Coast brought three more successful locals properties—Gold Coast, Suncoast, and the recently expanded Orleans—creating a much larger footprint in a fast-growing segment of the Las Vegas market.

It also fused two long-standing Las Vegas gaming families. When the Nevada Gaming Commission approved the acquisition, Commissioner Augie Gurrola called it “one of these marriages made in heaven,” telling the principals William Boyd and Michael Gaughan that he expected “a lot of good work” from them in the future.

By this point, the pattern was clear. While others chased the Strip’s mega-projects, Boyd doubled down on something less glamorous but far more predictable: locals and regional drive-in customers. Strip casinos lived and died by tourism cycles, airline schedules, and convention calendars. But a neighborhood casino—done right—could keep earning through thick and thin. That stability became Boyd’s edge, and it set the stage for the one time the company would forget its own rulebook.

IV. The Financial Crisis & Near-Death Experience

In retrospect, the timing feels almost cruel. Boyd had just assembled exactly what it was built to win at: a portfolio of locals casinos in Las Vegas and drive-to regional properties across the country. Then it made the one move that ran directly against its own instincts.

In 2006, Boyd went after the Strip.

The company announced Echelon Place, a planned $4.8 billion resort complex on the site of the Stardust. It was, by far, the biggest swing in Boyd’s history—and it was a swing at the part of the market Boyd had spent decades avoiding. This wasn’t another neighborhood casino with good food and a strong slot club. This was a mega-resort meant to compete with MGM, Caesars, and Wynn, funded by billions of construction financing and dependent on tourists and convention calendars behaving perfectly.

The Stardust had been a Boyd property since 1985. But the plan for its future was a complete reinvention. Echelon was envisioned as a mixed-use complex with five themed hotels totaling roughly 5,000 rooms, a 140,000-square-foot casino, extensive retail and dining, a 750,000-square-foot convention center, multiple theaters, and sprawling pool and recreation areas—all spread across more than 87 acres on the north end of the Strip.

Boyd even reshaped its Strip footprint to make the project possible. It swapped the Barbary Coast to Harrah’s Entertainment in exchange for 24 acres near the Stardust, stitching together an 87-acre parcel. The Stardust closed on November 1, 2006, and was imploded on the night of March 13, 2007—Vegas spectacle, in service of what was supposed to be Vegas’s next big thing.

Construction began on June 19, 2007. The opening was targeted for 2010.

Then the world changed.

By the time the credit markets seized up, Boyd had secured financing for about $3.3 billion of the $4.8 billion price tag, including three of Echelon’s hotels. The loans carried an interest rate of less than 5 percent and were set to mature in May 2012. But crucial parts of the project still weren’t financed, including a $500 million retail mall and two boutique hotels that together would have added roughly another $1 billion in cost.

And the trouble wasn’t just Boyd’s. Echelon relied on partners—Morgans Hotel Group and General Growth Properties—to fund and build pieces of the development. When the Great Recession hit, those partners couldn’t raise the money for their portions.

On August 1, 2008, Boyd suspended construction.

By then, the company had already put roughly $500 million into the site: preparation, foundations, and the early structures of what were becoming real buildings. Parts of the hotel towers had risen to about eight stories. In public, executives pointed to “the difficult environment in today’s capital markets, as well as weak economic conditions,” and suggested work might resume in three to four quarters.

It didn’t.

Investors’ reaction made the subtext explicit. Boyd’s stock jumped about 20 percent the day the postponement was announced. Wall Street wasn’t punishing Boyd for stopping. It was celebrating that the company was no longer trying to finish the project at all costs. The message was unmistakable: the market had been worried the Strip ambition would sink the whole ship.

And now Boyd was stuck with the worst possible middle ground—neither a completed resort nor a clean exit. Just an 87-acre construction site with partially built steel-framed towers and half a billion dollars of sunk cost. As the downturn accelerated, Strip gaming revenues fell sharply, projects across the city were cancelled or paused, and operators across the industry were forced into renegotiations, alliances, and survival mode.

Inside Boyd, the crisis rewired how leadership thought about leverage and risk. The company’s CFO later reflected that the lesson would be lasting—like the Depression had been for earlier generations—changing how they would manage “personally and within the company.”

As the recession deepened, Boyd’s own timeline kept slipping. In October 2009, it said it would likely be three to five years before development resumed.

At the same time, another big question sat on the balance sheet: Atlantic City.

Borgata had been the crown jewel of the expansion years. It generated more than a third of Boyd’s profits. But the Atlantic City market was deteriorating, squeezed by new casinos in neighboring states—especially Pennsylvania—and headed into a structural decline that would eventually claim multiple properties.

The Borgata partnership also carried its own complexity. MGM wanted out of New Jersey, and the joint-venture structure made the path messy. A clean sale didn’t materialize right away. Years later, in May 2016, MGM agreed to purchase Boyd’s 50 percent stake in Borgata for $900 million in cash and assumed debt. Boyd said it received $589 million from the transaction after deducting its share of Borgata’s outstanding debt, and it planned to use the proceeds largely to pay down debt and for general corporate purposes.

In hindsight, the exit was well-timed. Borgata remained the market leader, but Atlantic City’s broader collapse and consolidation hit hard in the years that followed.

Boyd’s final break with the Strip dream came earlier. In March 2013, it sold the Echelon site to Genting Group for $350 million. Genting planned to develop it as Resorts World Las Vegas.

Financially, it was brutal. Boyd recorded a one-time, noncash pretax impairment charge of about $994 million tied to the decision not to complete Echelon. The sale contributed to a roughly $900 million loss in the fourth quarter.

But strategically, it was the beginning of recovery: the moment Boyd stopped trying to become something it wasn’t.

“Our highest priority is strengthening our balance sheet,” CEO Keith Smith said at the time. “The sale of the Echelon site is another important step in the ongoing effort to improve our long-term financial position. While we remain committed to the Las Vegas market, we determined that developing a large-scale project on the Las Vegas Strip was not consistent with our current strategy.”

The tuition was enormous. But it permanently changed the company’s posture. Coming out of the crisis, Boyd and much of the industry shifted away from grand, debt-heavy moonshots and toward discipline: incremental expansion, diversified revenue streams, and a much sharper sense of what could kill you if the cycle turned.

Boyd had tried the Strip’s game once. It almost didn’t survive it.

V. The Turnaround & Peninsula Acquisition

By 2011, Boyd Gaming had made it through the financial crisis—but it didn’t come out unscarred. The company had taken the Echelon write-off, sold valuable assets, laid off thousands of employees, and suspended its dividend. What it still had, though, was the part of the business that had always worked: a network of locals casinos and regional, drive-to properties built on Sam Boyd’s old formula of repeat customers and steady habits.

So the comeback plan was simple, and intentionally unglamorous: pay down debt, refocus on the core regional markets, and only grow when prices reflected the post-crisis world—not the pre-crisis fantasy.

That’s what made the Peninsula Gaming deal in late 2012 such a signal. Boyd was ready to expand again, but this time it was doing it on its own terms, in its own lane.

Boyd announced a definitive agreement to acquire Peninsula Gaming, LLC for total consideration of $1.45 billion. Peninsula, headquartered in Dubuque, operated five casinos across the Midwest and South.

“Acquiring Peninsula Gaming is a transformative transaction that fits perfectly into our growth strategy by expanding our Company's scale, diversifying our platform, strengthening our financial profile, and generating meaningful value for our shareholders,” Keith Smith, Boyd’s president and CEO, said at the time. He emphasized that Peninsula’s properties were well-managed and located in resilient markets.

And the geography mattered. With Peninsula, Boyd added new footholds in Iowa and Kansas, while building on what it already had in Louisiana. Smith called it “an opportunity to really expand in the Midwest,” noting that it was where business looked strongest then. The deal also pushed Boyd further toward a portfolio that didn’t live or die by any single market cycle.

Financially, Boyd framed the price as disciplined: about seven times trailing 12-month EBITDA for Peninsula’s four properties in Iowa and Louisiana. The deal brought Boyd into Iowa through the Diamond Jo casinos in Dubuque and Northwood; Smith said those two properties controlled more than 40 percent of the northeast Iowa market.

Kansas Star, meanwhile, was positioned as the prize asset—the “jewel of the Peninsula portfolio,” and a long-term growth opportunity. An interim facility in Mulvane opened in December, with a permanent casino and hotel planned to open the following January.

The acquisition also changed Boyd’s scale overnight. After the transaction, Boyd had more than 25,000 employees and 22 properties spanning Nevada, New Jersey, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Louisiana, and Mississippi. And even as it expanded on the ground, Boyd was also preparing to enter online gaming, lining up a license for intrastate online poker in Nevada.

Culturally, Boyd leaned on a familiar message: this wasn’t a merger of opposites. “Boyd Gaming and Peninsula share very similar cultures and business models,” Smith said, pointing to customer service, efficient operations, and community involvement.

But the most telling detail was how Boyd described its own future. Smith said the company expected more than two-thirds of its cash flow to come from regional markets. That wasn’t just a metric—it was a declaration. Boyd wasn’t going back to the Strip dream. It was committing, explicitly, to being a regional operator.

That commitment also explains why Boyd survived when others didn’t. Diversification mattered, but so did what Boyd was diversified into. Strip casinos were exposed to tourism disappearing overnight. Locals properties, by contrast, still had customers who lived down the road. And with revenue spread across multiple states, no single market downturn could become an extinction event.

By 2016, Boyd was still sharpening the portfolio around that thesis. It expanded further in the Las Vegas locals market by acquiring Aliante Casino and Hotel for $380 million and the two Cannery Casino Resorts properties for $230 million. Around the same period, it also sold its 50 percent stake in Borgata to MGM for $900 million.

By the end of 2016, the arc of the turnaround was clear. Boyd had taken the biggest mistake in its history, absorbed the pain, and rebuilt into something far more durable: a focused regional operator with greater geographic diversity, a repaired balance sheet, and the cash flow to start thinking about growth again—without betting the company.

VI. The Transformation Decade: M&A, Sports Betting & Geographic Expansion

By 2017, Boyd Gaming had put the crisis years behind it. The balance sheet was steadier, the portfolio was bigger and more diversified, and management had internalized the hard lesson of Echelon: don’t gamble the company on a single, fragile bet.

Then the industry’s next earthquake hit. In 2018, the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Murphy v. NCAA opened the door for states to legalize sports betting. For casino operators, it was the start of a new gold rush—one that rewarded speed, technology, and regulatory access.

Boyd found itself in a rare position: it had the licenses and the physical footprint, but it didn’t have to pretend it was a Silicon Valley product company. Instead of building a sports-betting platform from scratch, it did what the post-Echelon version of Boyd was built to do: partner, stay disciplined, and turn its existing assets into leverage.

In August 2018—just months after the ruling—Boyd and FanDuel announced a strategic partnership to pursue sports betting and online gaming opportunities across the United States.

“Through this partnership, Boyd Gaming and FanDuel Group will be in excellent position to successfully capitalize as sports betting and online gaming expand across the country,” Keith Smith, Boyd’s President and CEO, said at the time. “By joining forces with FanDuel’s nationally-known brand, as well as their considerable technical expertise and resources, we will be positioned to build market-leading sports-betting and online gaming operations in each state as they move forward with these new forms of gaming.”

The deal’s genius was in its fit. Boyd received a 5% stake in FanDuel as part of the partnership, and it also became a “market access” on-ramp for FanDuel in certain states—places where online operators needed ties to a brick-and-mortar casino license, like Indiana. Boyd didn’t have to win the app war. It just had to provide what FanDuel couldn’t easily manufacture: regulated access and real-world casino infrastructure.

That same year, Boyd kept building out the core, too. In late 2018, it acquired Valley Forge Casino Resort in Pennsylvania for $281 million, giving Boyd a foothold in the Philadelphia market. It also purchased the operations of four casinos from Pinnacle Entertainment for $564 million: Ameristar Kansas City, Ameristar St. Charles, Belterra Casino, and Belterra Park. It was classic Boyd expansion—regional, drive-to oriented, and spread across markets so no single geography could dominate the risk profile.

Then came COVID-19.

For casinos, the pandemic wasn’t a normal downturn. It was a lights-out order. In July 2020, Boyd announced layoffs affecting at least 25% of its workforce—thousands of jobs across its properties—as shutdowns dragged on and uncertainty ruled every planning meeting.

But the recovery, once reopenings began, flipped the script. Regional casinos came back faster than almost anyone predicted. In many places, the local casino reopened before restaurants, theaters, and other entertainment options. And because Boyd’s business wasn’t concentrated in one destination market, it benefited as different states reopened at different times—its geographic diversity turning into a real operating advantage.

The FanDuel partnership ultimately became one of the most financially meaningful moves of the era. In 2025, Flutter Entertainment reached an agreement to purchase Boyd Gaming’s remaining 5% ownership in FanDuel for $1.76 billion, with the deal expected to close in the third quarter of 2025.

Boyd acquired that 5% interest in 2018 for an undisclosed price. Selling it for nearly $1.8 billion wasn’t just a great trade. It was validation of the post-crisis Boyd playbook: avoid ego projects, use your real advantages, and let partnerships do the heavy lifting where you don’t have one.

VII. Modern Era: The Online Gaming Arms Race & Strategic Positioning

The 2025 sale of Boyd’s FanDuel stake didn’t just put a massive number on the scoreboard. It made Boyd’s underlying strategy impossible to miss: ride the online wave through partnerships, not platform ownership.

While other operators spent heavily trying to build or buy their way into a national app—Penn’s high-profile swings are the obvious example—Boyd took the quieter route. It focused on what it already had that was scarce: licenses, local databases, and a real operating footprint. FanDuel brought the product, the brand, and the speed. Boyd provided the access and the on-the-ground execution. When online sports betting exploded, Boyd participated in the upside without signing up for the tech arms race.

By 2025, that choice showed up everywhere you’d expect: in steadier operations, a simpler story, and a balance sheet that looked nothing like the one that almost sank under Echelon.

In the third quarter of 2025, Boyd reported $1.0 billion in revenue, up 4.5% from the same quarter the year before. CEO Keith Smith pointed to the same engine that’s powered Boyd for decades: loyal, repeat customers. “Across the country, we continue to see strengthening play from our core customers,” he said.

The financial recovery is easiest to see in the company’s flexibility. As of September 30, 2025, Boyd had $319.1 million in cash and $1.9 billion in total debt. And the FanDuel deal was the accelerant: in July 2025, Boyd sold its 5% stake in FanDuel for $1.755 billion in cash, cutting leverage from 2.8x to 1.5x. CFO Josh Hirsberg summed up what that kind of change buys you in this business: “We have outstanding flexibility to continue executing our strategy.”

That flexibility wasn’t just theoretical. Boyd’s development pipeline kept moving, with projects advancing across multiple markets: an Ameristar St. Charles meeting and convention center, the Cadence Crossing property slated for a 2026 opening, a Paradise facility expected to begin construction in late 2026, and a $750 million resort in Norfolk, Virginia targeted to open in 2027.

Just as important, Boyd kept leaning into the kind of expansion that doesn’t require betting the company. Its managed relationship with Sky River Casino in Northern California is the clearest example of the model Boyd now prefers: capital-light growth, with the operator’s expertise doing the heavy lifting. Demand stayed strong in the three years after Sky River opened, and Boyd and the Wilton Rancheria tribe moved forward with an expansion plan. Phase one adds 400 slot machines and a 1,600-space parking garage, expected to be completed in the first quarter of next year. Phase two goes bigger: a 300-room hotel, three new food-and-beverage outlets, a full-service resort spa, and an entertainment and event center.

Underneath all of this is the same thesis Boyd has been refining since the California Hotel found its Hawaiian customer: regional gaming can be boring—and that’s the point. Boyd’s footprint across markets including Louisiana and Mississippi means the business isn’t dependent on a single tourism engine or a single convention calendar. And in Las Vegas, it continues to prioritize the locals market: properties away from the Strip, built for convenience, value, and habit, with amenities designed around residents rather than once-a-year visitors.

To keep those habits sticky, Boyd has continued investing in the unsexy tech that actually matters in regional gaming: loyalty programs, mobile apps, and data analytics that drive retention. The company maintained property-level operating margins above 40% and returned nearly $750 million to shareholders in 2024.

VIII. The Boyd Gaming Playbook: What Makes This Company Different

After 50 years in the business, Boyd’s edge isn’t a secret sauce—it’s a set of habits. While the biggest operators chased high-roller tourism and destination-resort economics, Boyd built its advantage around a different customer entirely: the person who lives nearby and comes back often.

That “locals first” philosophy traces straight back to Sam Boyd’s Depression-era instincts: steady, repeat customers matter more than a few flashy weekends. Boyd stayed close to that idea for decades, building casinos that fit into people’s routines—places designed for regulars, not once-a-year visitors. Even in markets like Tunica, where the early drive-to model worked until the region got crowded with casinos, the lesson held: the best business is the business that reliably returns.

Over economic cycles, the middle-market customer is the whole point. When recessions hit, tourists stop traveling first. Locals still want affordable entertainment, and they don’t need a plane ticket to get it. That dynamic helped Boyd when Las Vegas went through the post-2008 collapse: because Boyd wasn’t all-in on the Strip, it had less exposure to the tourism freefall. And because it wasn’t dependent on just one market, weakness in one region could be offset by strength in another.

That geographic diversification is a moat in a heavily regulated industry. Boyd operates across Nevada, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Ohio, and Pennsylvania. No single market is so dominant that a downturn there becomes existential. Decades of disciplined expansion built a footprint that spreads risk—and gives Boyd more ways to win without needing any one property to be a home run.

Operational discipline is the other pillar. The Echelon experience taught Boyd, painfully, what overreach looks like. Since then, the playbook has been consistent: tight cost control, efficient capex, and a firm allergy to vanity projects. When Boyd sold the Echelon site, CEO Keith Smith framed it plainly: “Our highest priority is strengthening our balance sheet.” The language may have come from a crisis moment, but the mindset stuck.

The Boyd family legacy also shows up in the company’s long-term posture—how it treats employees, how it behaves in its communities, and how it thinks beyond the next quarter. UNLV’s William S. Boyd School of Law is named for Bill Boyd, in recognition of the $30 million he contributed to the school’s funding. Bill earned a bachelor’s degree in political science from the University of Nevada, Reno, and a law degree from the University of Utah. He also served in the United States Army from 1953 to 1955. He is the father of three children, and all three are involved in the family business.

That legacy continued into the current era. Executive Chairman Marianne Boyd Johnson—Bill Boyd’s daughter—has held the position since May 2023. She joined the company in 1977, has served on the board since 1990, and oversaw areas including purchasing, risk management, and diversity initiatives.

Then there’s partnership strategy—Boyd’s modern version of “stick to what you’re good at.” The FanDuel model captured it cleanly: Boyd brought the gaming licenses and physical presence; FanDuel brought the technology and brand. Boyd got exposure to the upside without signing up to build a national tech platform.

All of it ladders up to Boyd’s most distinctive choice: avoiding the Strip trap. While competitors poured tens of billions into mega-resorts—often with returns that didn’t justify the spectacle—Boyd focused where its advantages were real. The “boring” regional strategy beat Strip glamour over the long run precisely because it matched the company’s strengths to the right kind of opportunity.

And that’s why Boyd tends to look steadier in downturns. A good-value casino close to home can stay in the rotation even when budgets tighten. That stability doesn’t make for the flashiest headlines, but it does make for more predictable cash flow—and, over time, a company that’s hard to kill.

IX. Strategic Analysis: Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers

Porter's 5 Forces Analysis:

Threat of New Entrants: Casinos look easy to copy until you try to open one. Licenses are scarce, approvals are slow and invasive, and the upfront capital runs into the hundreds of millions for any property that actually matters. And even if you clear those hurdles, the local relationships—regulators, community leaders, vendors, repeat customers—take years to build. The twist is that legalization keeps moving the goalposts. As new states open up, new competitors show up too, and the growth of tribal gaming adds another layer to the competitive landscape. Boyd’s advantage here is less about any one property and more about having the licenses, the credibility, and the muscle memory of operating compliantly across jurisdictions.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Supplier power is generally low. Slot machines, food and beverage, and most inputs are widely available and price-competitive. The real constraint is labor. Post-COVID staffing pressures hit the entire industry, and the cost and availability of frontline workers can swing operating performance. Boyd’s long-standing reputation and culture help, but labor remains the supplier category that can bite.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: Customer power is moderate. Players can drive ten minutes in the other direction and find another casino, and online options make switching even easier. Boyd’s counterweight is the combination of loyalty and routine. Rewards programs create real switching costs through points and perks, but the bigger force is softer: once a customer decides this is “their” place, convenience and familiarity do a lot of the retaining.

Threat of Substitutes: This is the pressure that keeps rising. Online gaming and sports betting apps let customers gamble without leaving the couch, and they compete for the same leisure time and discretionary dollars as movies, restaurants, and everything else. Boyd’s response has been pragmatic: partner where it makes sense, rather than trying to out-tech pure-play digital operators.

Competitive Rivalry: Competition is intense in most markets, and it rarely stays still. New properties open, promotions escalate, and every operator fights for the same repeat customer. Boyd’s edge is that it’s built for this kind of knife fight: a locals focus, regional scale, and the ability to operate efficiently. In markets where Boyd runs multiple properties, it can offer different experiences and price points while keeping customers inside the ecosystem. And strong property-level margins give it breathing room when competitors start discounting.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis:

Scale Economics: Boyd has built meaningful scale in the places it cares about. In Las Vegas locals, it operates more properties than any competitor. In Louisiana, Peninsula added heft. That scale shows up in the unglamorous ways that matter: marketing leverage, operating efficiencies, and a management team that has seen every version of a regional cycle.

Network Economics: Traditional casino operations don’t naturally produce big network effects, but loyalty programs come close. Boyd Rewards gets more valuable as the property footprint grows, because customers can earn and redeem across more locations. The more properties in the network, the more reasons there are to stay.

Counter-Positioning: Boyd’s entire history is a case study in counter-positioning. While the biggest names poured capital into destination resorts and Strip glamour—businesses that depend heavily on travel and convention volume—Boyd leaned into locals and drive-to markets. It wasn’t as sexy, but it was structurally hard for the Strip giants to follow without undermining their brand and economics. Boyd won by playing a different game.

Switching Costs: Switching costs are real, but not absolute. Points and tier status matter, yet the deeper moat is habit. For a locals customer, a casino isn’t a one-time choice—it’s a weekly rhythm. Once that routine sets in, it takes a lot to break it.

Branding: Boyd’s brands are powerful where they’re planted. Sam’s Town has decades of recognition with Las Vegas locals. The California Hotel effectively owns the Hawaiian visitor niche. Properties like the Orleans, Gold Coast, and Suncoast are fixtures in their neighborhoods. What Boyd doesn’t have is a single national consumer brand on the level of Caesars or MGM, which limits its pull with customers who don’t already know the markets.

Cornered Resource: In gaming, licenses are the scarce asset. In Nevada, the value is not just the license itself but the regulatory relationships and reputational capital built over decades. In states with limited licenses, simply already being in the club can be a durable advantage.

Process Power: This is Boyd’s quiet superpower: the operational system behind the properties. Running a locals casino well isn’t just about having slots and restaurants—it’s about the day-to-day discipline that keeps customers coming back and costs under control. Boyd’s ability to deliver strong property-level margins consistently across a broad portfolio reflects processes, culture, and institutional knowledge that are hard to replicate quickly—especially for new entrants trying to buy their way into competence.

X. Bull vs. Bear Case & Future Outlook

Bull Case:

Sports betting and iGaming remain a long runway, and Boyd has a clean way to participate. Its partnership with FanDuel runs through 2038, which means Boyd can collect fixed fee income tied to the nation’s leading sports-betting operator—without having to build the product, fight the customer-acquisition war, or take on the operating risk.

Geographic expansion is still on the table as more states legalize. Boyd’s advantage here isn’t hype; it’s repetition. It knows how to win licenses, open properties, and run them efficiently. The biggest visible swing right now is the $750 million resort under development in Norfolk, Virginia—exactly the kind of new market entry that can add a fresh growth engine without changing the company’s DNA.

The regional gaming model has also shown it can bend without breaking. Boyd’s customer is local, not tourist-dependent, and that tends to hold up better across cycles. Pair that with a footprint spread across multiple states, and you get a business that’s less likely to be taken out by one bad market or one bad year.

Then there’s cash. Boyd has been generating strong free cash flow, which gives it options: fund growth projects, keep upgrading properties, and still return capital to shareholders. In Q4 2024 alone, it repurchased $203 million of stock. Across the full year, it returned nearly $750 million to shareholders, while also steadily raising the quarterly dividend.

M&A remains a wildcard tailwind. Gaming is consolidating, and Boyd has historically been opportunistic when assets are priced right. After the sale of its FanDuel stake, some analysts even speculated that it could spark conversations about a much larger move—like pursuing Penn Entertainment, which operates 43 casinos in 21 states.

Finally, there’s operational leverage. As properties mature and marketing gets more efficient, incremental revenue can fall to the bottom line faster. Boyd’s newer investments are an important proof point here. Projects like Treasure Chest’s land-based facility have been outperforming expectations, reinforcing the idea that Boyd can generate attractive cash-on-cash returns when it sticks to well-defined, regional projects.

Bear Case:

The biggest structural risk is online cannibalization. As sports betting and iGaming get easier and more widely legal, some gambling spend inevitably shifts from the casino floor to the phone. And while Boyd has chosen a capital-light path through partnerships, selling its FanDuel equity means it no longer has the same direct participation in the upside of that digital shift as competitors with proprietary platforms.

Boyd’s customer base is also the one that can feel a downturn first. Middle-market households tend to tighten entertainment budgets when inflation bites or a recession hits, and casinos—especially the locals variety—compete with a lot of other “nice-to-have” spending.

Competition keeps escalating, too. Tribal operators, new commercial licenses, and newly legalized states can all crowd the field. Virginia is a good example: it’s a major opportunity, but it also shows how legalization can fragment regional demand and intensify the fight for the same customer.

Boyd’s deliberate choice to avoid the Strip and international tourism markets comes with a tradeoff. It means less exposure to high-growth engines like the Las Vegas Strip and Macau—areas where some competitors can see outsized gains when travel booms.

Margins face pressure from labor as well. Post-pandemic staffing dynamics have pushed wage costs higher across hospitality, and those pressures don’t disappear just because demand improves.

And while the FanDuel partnership still provides income, the equity-style upside is gone. Boyd can still benefit from the relationship, but it no longer owns the kind of stake that turned into a once-in-a-generation financial win.

Lastly, many of Boyd’s markets are mature. In places where capacity is already built out, growth often comes more from operational improvement than from expanding the total customer base—which can limit how fast revenues climb without major new development.

Key Performance Indicators to Monitor:

For long-term investors tracking Boyd Gaming, two metrics deserve primary attention:

Same-Store Revenue Growth in Key Markets: This is the clearest read on organic health—how Boyd is performing without the noise of acquisitions. The most important lenses are the Las Vegas locals segment and the Midwest & South segment, which together make up the bulk of Boyd’s revenue. Sustained positive trends suggest the model is still winning with its core customer; persistent weakness would hint at share loss or a softening local consumer.

Free Cash Flow Yield and Capital Allocation: Boyd’s story only works if it keeps converting earnings into real cash—and then uses that cash intelligently. In 2024, it returned nearly $750 million to shareholders while still investing in upgrades and the Norfolk development. The question going forward is whether Boyd can keep that balance: steady free cash flow, disciplined reinvestment, and shareholder returns that don’t come at the expense of the long game.

XI. Epilogue & Reflections

The Boyd Gaming arc—from a family business downtown, to a public company, through a near-death experience, and into a modern coast-to-coast operator—has lessons that travel well beyond casinos.

The most surprising part, in hindsight, is that the “boring” strategy won. Over the long run, Boyd’s regional, locals-first model outperformed Strip glamour not because Boyd got lucky, but because it kept playing the game it was built to win. The moment Boyd nearly broke itself, it wasn’t because the locals formula stopped working. It was because the company tried to abandon that formula and compete in a lane where it didn’t have the same advantage. Echelon wasn’t just expensive—it was ambition unmoored from what made Boyd Boyd. The recovery began when leadership returned to first principles.

For founders, Boyd is a reminder that “know your customer” isn’t a slogan; it’s an operating system. Sam Boyd understood that the person scraping together a few dollars for bingo and the local resident coming in for dinner and a few hours on the slot floor were looking for the same thing: respect, consistency, and obvious value. That insight scaled—from one struggling downtown property, to an entire portfolio designed around repeat visits and routine.

It also shows how much discipline matters. Bill Boyd built on his father’s foundation by keeping the culture intact while professionalizing the company. The Coast Casinos merger, the Peninsula acquisition, and the steady regional expansions all fit the same pattern: extensions of proven capability, not leaps into the unknown. When Boyd broke that pattern with Echelon, the results were almost catastrophic.

What separates survivors from failures is what they do after the mistake. The post-Echelon Boyd—deleveraging, diversifying geographically, and partnering rather than trying to own every platform—looks like real organizational learning. Management came out of the crisis with sharper clarity about what Boyd does well, and what kinds of risks are simply not worth taking.

For investors, survivorship itself is a signal. Boyd’s 50-year anniversary in 2025 marked something rare in gaming: multi-decade continuity through booms, busts, and shifting technology. Many competitors that once looked stronger at various points either disappeared or no longer exist independently.

And management quality shows up most clearly when the options are bad. The decisions made under pressure from 2008 through 2013—suspending Echelon, selling to Genting, acquiring Peninsula, and exiting Borgata—required nerve and focus. Those calls positioned Boyd for the growth and flexibility that followed.

Diversification, done the right way, works too. Not diversification as a grab bag, but geographic diversity that reduces reliance on any one market while still leaning on the same core capabilities: efficient operations, loyalty-driven marketing, and properties built for repeat customers.

Looking forward, the industry keeps moving. Online gaming grows. Sports betting expands to new states. Technology reshapes how customers are acquired and retained. Consolidation keeps rearranging the competitive map.

Boyd enters that next chapter with the hard-earned advantages its history taught it to prioritize: a strong balance sheet, a diversified footprint, operational discipline, partnerships where appropriate, and capital allocation that doesn’t rely on perfect timing. Whether Boyd pursues major M&A, grows through developments like Norfolk, or keeps returning capital to shareholders, it does so from a position of strength that Sam Boyd could scarcely have imagined when he arrived in Las Vegas with eighty dollars in 1941.

The national gaming landscape is getting more crowded and more competitive. Boyd looks as prepared as any operator to handle it. And if its first 50 years proved anything, it’s this: the closer you stay to your customer, the more reliably your customer stays with you.

XII. Further Reading & Resources

Top 10 Long-Form Links & Books:

-

"Finding the Next Starbucks" by Michael Moe - Includes a chapter on Boyd Gaming’s crisp, repeatable regional casino model.

-

"Winner Takes All: Steve Wynn, Kirk Kerkorian, and the Race to Own Las Vegas" by Christina Binkley - Great context on the Strip’s arms race and the competitive dynamics Boyd chose not to chase.

-

Boyd Gaming 10-K Filings (2008, 2017, 2024) - The cleanest primary sources for how the company described the crisis, the recovery, and the modern strategy (available at SEC.gov).

-

"The Money and the Power: The Making of Las Vegas" by Sally Denton & Roger Morris - A broader history that helps you understand the downtown Las Vegas world that shaped the Boyd family’s approach.

-

CDC Gaming Reports (2010–2025) - Ongoing industry reporting on regional gaming, regulation, and market shifts across Boyd’s key territories.

-

"License to Steal: Nevada's Gaming Control System" by Jeff Burbank - A deep dive into Nevada regulation—and why credibility and compliance are such durable assets in this industry.

-

Morgan Stanley Gaming Industry Reports - Wall Street’s angle on Boyd and its peers: strategy, positioning, and what the market is watching.

-

Las Vegas Sun archives on Echelon Place - Contemporary coverage of the project’s rise, stall, and fallout—the clearest real-time record of Boyd’s biggest misstep.

-

"Super Casino: Inside the 'New' Las Vegas" by Pete Earley - A culture-and-business look at modern Vegas that helps frame the difference between Strip spectacle and locals-driven economics.

-

American Gaming Association “State of the States” reports - A strong reference for state-by-state legalization, market sizing, and the regulatory map Boyd has learned to navigate.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music