Byline Bancorp: The Story of Chicago's Community Banking Survivor

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

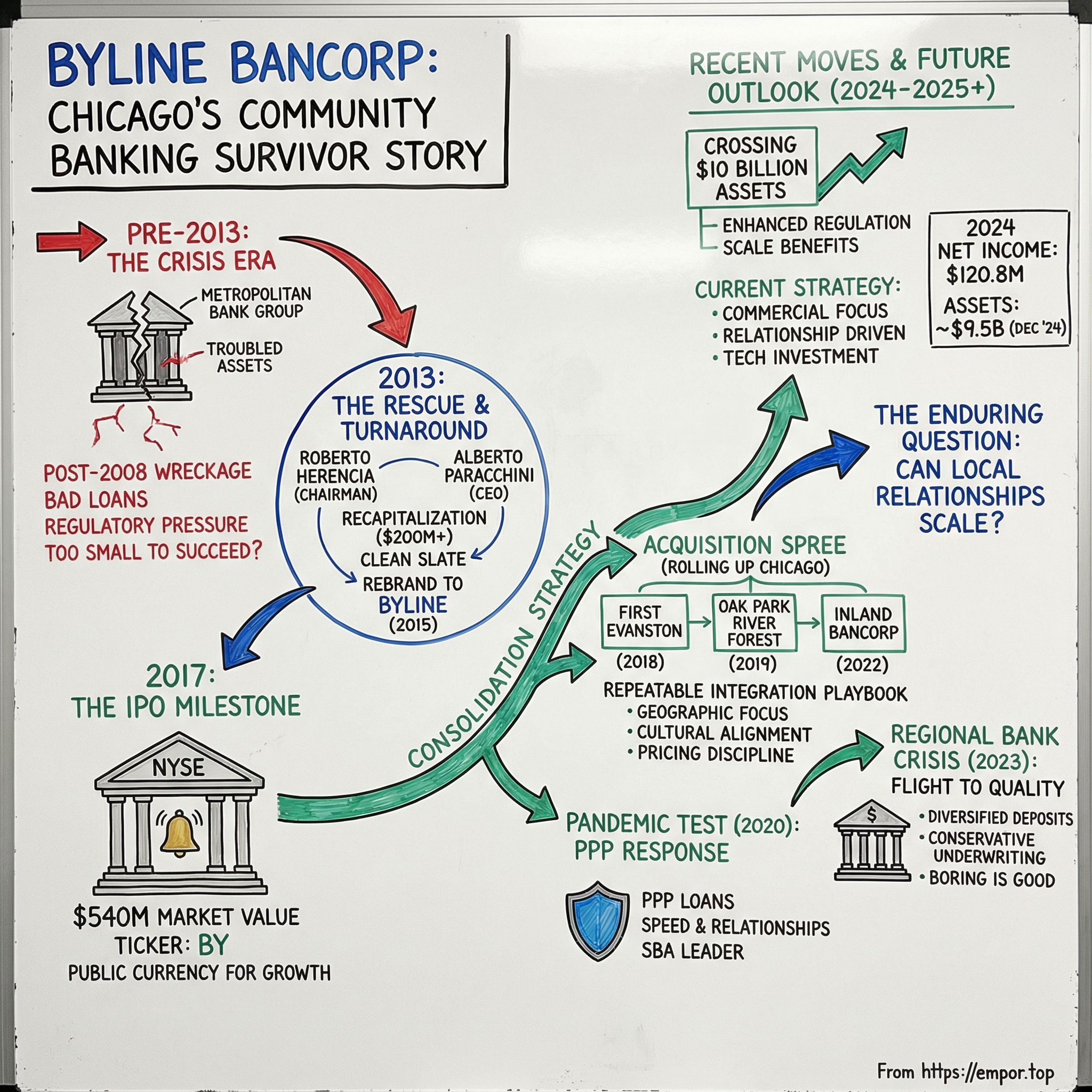

Picture this: June 30, 2017, at the New York Stock Exchange. A team of Chicago bankers has just rung the bell and is already hustling back toward the airport, phones lighting up with congratulations. They’ve pulled off something that, in modern banking, is anything but routine: taking a once-troubled local bank public at a roughly $540 million market value.

“This is a huge milestone,” CEO Alberto Paracchini says in an interview, as the team races to catch its flight.

What makes that moment so striking is what came before it. Just four years earlier, the bank—then known as Metropolitan Bank Group—was still living in the wreckage of the 2008 financial crisis, weighed down by bad loans and teetering on the edge. The IPO was the market’s stamp of approval on a hard, unglamorous cleanup: Chairman Roberto Herencia and Paracchini had stabilized the franchise after Herencia led a group of Mexican investors that recapitalized it with more than $200 million nearly four years earlier.

Fast-forward to today, and Byline Bancorp looks like a survivor story with a second act. As of December 31, 2024, it reported $9.5 billion in assets and positioned itself as “Chicago’s preeminent commercial bank.” The company trades under the ticker “BY” and posted 2024 net income of $120.8 million, or $2.75 in diluted earnings per share.

But the real question isn’t whether Byline survived. It did. The question is whether the model endures.

How did a scrappy 2017 bank merger not just make it through regulatory chaos, a pandemic, and the biggest bank failures since 2008—but come out stronger? And zooming out even further: does community banking have a future in a world of fintech disruption, rate shocks, and megabanks with bottomless tech budgets?

This is a story about consolidation as a strategy, about local relationships that still matter in a digital world, and about the middle-market squeeze that forces community banks to either get bigger or get bought. It’s the story of how a Puerto Rican banker named Roberto Herencia bet his reputation on rescuing a Chicago institution—and how a management team turned that rescue into one of the cleaner turnaround-to-growth arcs in modern community banking.

Let’s dive in.

II. Setting the Stage: Community Banking in America

To understand Byline’s story, you have to rewind to the golden age of American community banking—a world that, from today’s vantage point, feels almost quaint.

In the mid-1980s, community banks held roughly 38 percent of industry assets. By 2008, that share had fallen to about 14 percent. In that same stretch, the U.S. went from nearly 19,000 banks and thrifts to far fewer. The “why” is one of the biggest structural shifts in modern finance: a slow-moving collision between regulation, technology, and the relentless logic of scale.

For most of the 20th century, American banking was intensely local by design. The McFadden Act of 1927 blocked banks from branching across state lines, and many states piled on with even tighter limits. Illinois was especially strict: for years, its unit banking laws effectively kept banks confined to a single county. The result was a landscape built for small institutions. In Chicago, a neighborhood might have its own bank—literally. These weren’t just places to deposit checks. They were civic fixtures, where a business owner could walk in, sit down with the bank president, and make the case for a loan.

That relationship model worked because information was expensive and geography mattered. A local banker knew which contractors were reputable, which storefronts were turning over, which families always paid on time. Before anyone talked about “data” and “edge,” this was it: local knowledge turned into credit decisions.

Then the map started to change. Illinois didn’t repeal its unit banking rules until the 1980s—roughly two decades after many other states. That late start delayed consolidation. And that delay mattered: it meant that when the rest of the country had already been swept into larger regional franchises, Chicago and the broader Illinois market still had a dense undergrowth of small, privately held banks—exactly the kind that would become targets, or casualties, in the next era.

By the 2010s, Chicago had become a strange hybrid. At the top sat the money-center giants—Chase, Bank of America, BMO Harris—armed with sprawling branch networks and the kind of technology budgets community banks couldn’t dream of. JPMorgan Chase, the nation’s largest bank, dominated local branching and product breadth.

But Chicago also had a deep bench of local players. Wintrust Financial, based in Rosemont and among the area’s largest deposit holders, pursued a very different strategy: a community-banking feel at scale, operating through more than 10 separately chartered, locally branded banks spread across the metro area.

Below them was the long tail: dozens—arguably hundreds—of community banks, some founded in the early 1900s, many family-controlled, most too small to comfortably fund modern compliance and technology. That fragmentation created both a problem and a possibility. It was a problem because survival was getting harder every year. It was a possibility because someone could stitch the market together—if they had the discipline, the capital, and the stomach for a slow, complicated roll-up.

And the pressure on the old model was coming from every direction: big banks with better digital experiences and denser ATM networks; credit unions with structural tax advantages; and a rising generation of online lenders that didn’t need branches at all. For a Chicago community banker in the 2000s, the question wasn’t about growth. It was about existence: can we survive—and if we can, what do we have to become?

That’s the backdrop for why Byline matters beyond its own numbers. Byline is, at its core, a bet about American banking: that there’s still room between the megabanks and the upstarts for a locally rooted, relationship-driven institution—but only if it gets big enough, fast enough, to carry the modern cost of being a bank.

III. The Financial Crisis & Its Aftermath: A New World for Small Banks

September 2008 changed the rules of the game.

After more than a decade when bank failures were relatively rare, the financial crisis triggered a wave of collapses: 489 banks failed from 2008 through 2013. The most famous was Washington Mutual, a roughly $307 billion institution and still the largest failure in FDIC history.

But beneath the headlines about Wall Street giants was a quieter story that hit Main Street harder. Between January 2008 and December 2011, 414 U.S. banks failed, according to the GAO. About 85 percent of them—353 banks—had less than $1 billion in assets. These were the lenders that knew the local contractors, the family-owned manufacturers, the restaurant owners. When they went under, the damage didn’t just show up on a balance sheet; it showed up in small business credit drying up and local jobs disappearing.

The community banks that failed tended to rhyme. Many were overconcentrated in commercial real estate. They chased growth during the boom, didn’t carry enough capital for a downturn, and then got crushed when property values fell. Loans that looked safe in 2006—strip centers, condo projects, office buildings—turned into anchors when tenants vanished and vacancies spiked. The FDIC’s resolution process became grimly routine, with regulators often stepping in at the end of the week and handing the keys to a healthier buyer.

And then, when the immediate panic eased, the second wave hit: regulation.

In 2010, Congress passed the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. It brought more than 400 new rules and mandates aimed at making the system safer.

Here’s the irony: community banks weren’t the ones engineering subprime securities or packaging mortgages into CDOs. But they got caught in the blast radius anyway. Rules designed with trillion-dollar institutions in mind landed on small banks with the force of fixed costs: compliance staff, upgraded systems, new reporting requirements, more documentation for everything. For a $500 million bank, it wasn’t a rounding error. It could be the difference between profitable and stuck.

Surveys captured the shift in mood. In one survey of 322 small financial institutions, 79 percent called regulatory compliance a significant challenge—up from 66 percent in 2008 and 42 percent in 2004. And it wasn’t just frustration; it was expense. Most said they expected higher training costs and software upgrades just to keep up.

Academic work pointed to the same trend. A Harvard University study concluded that smaller banks were hurt by Dodd–Frank’s regulatory load, and noted a long-term decline in community banks’ share of U.S. banking assets and lending.

This is where the “too small to succeed” era begins. “Too big to fail” banks got bailouts and backstops. Community banks faced something more mundane and, in some ways, more lethal: death by a thousand paper cuts. Any one requirement could sound reasonable. The pile-up made running a small bank dramatically harder.

And that pressure created a predictable outcome: consolidation. If compliance was a largely fixed cost, then scale wasn’t optional anymore. You either got big enough to spread those expenses across a larger revenue base, or you found a buyer.

This is the world that sets up Byline’s formation narrative. In the wreckage, a certain kind of banker saw opportunity. Not the kind that comes from financial engineering, but the kind that comes from structure: an industry forced to merge, a growing pipeline of potential sellers, and a regulatory environment that made new bank formation extremely difficult.

For long-term investors, it also created what you might call a regulatory moat—not a classic competitive advantage like a brand, but a barrier to entry. Starting new banks got harder. Existing banks got more expensive to run. The survivors who achieved enough scale could face less competition and, at the same time, find plenty of acquisition targets.

It was into this environment that Roberto Herencia led a group of investors in 2013, placing a bet on a struggling Chicago institution called Metropolitan Bank Group. What they thought they were buying wasn’t a broken bank.

It was a platform.

IV. The Origin Story: Two Banks, One Vision

Byline’s story doesn’t start with a merger. It starts with a rescue.

By 2013, Metropolitan Bank Group—one of Chicago’s older banking franchises—was in real trouble. The company had been founded in 1978 by the Fasseas family after the purchase of North Community Bank. Over time, they expanded from a single location to more than 90 branches across the Chicago metro area. Then the financial crisis hit, and the growth story turned into a cleanup story. In 2009, the bank took $71.5 million from the Troubled Asset Relief Program.

The Fasseas name still shows up around Chicago in a surprising way—they founded PAWS, the animal shelter. But in banking, Metropolitan had become a case study in what went wrong after the boom: bad commercial real estate loans, a damaged reputation, and a franchise that looked like it might not make it.

Then came Roberto Herencia.

Herencia wasn’t a random distressed-asset tourist parachuting into town. By the time Metropolitan needed saving, he was already deeply embedded in Chicago banking and civic life. Since 2010, he had been President and CEO of BXM Holdings, Inc., an investment fund focused on community bank investments. Before BXM, he served as President and CEO of Midwest Banc Holdings, Inc. Earlier still, he spent 17 years at Popular Inc., including as Executive Vice President and as President of Banco Popular North America.

His background reads like a tour through every part of the banking stack: born and raised in Puerto Rico, scholarship to Georgetown, MBA from Northwestern’s Kellogg School of Management, and a decade at The First National Bank of Chicago (now part of JPMorgan Chase) in roles that included Deputy Senior Credit Officer and Head of the Emerging Markets Division.

He also built credibility outside the balance sheet. He served as a trustee of DePaul University and the Northwestern Memorial Foundation, sat on the Junior Achievement of Chicago Board of Directors, and joined the Archdiocese of Chicago’s Finance Council. Along the way, he earned civic recognition including the Distinguished Corporate Citizenship Award from The Jewish Council on Urban Affairs, the Evy Award from A Silver Lining Foundation, and the Ellis Island Medal of Honor.

That context matters because the rescue of a bank is never just about writing a check. It’s about trust—trust from regulators, from depositors, and from the local business community that needs to believe the institution will still be there next year.

In 2013, BXM Holdings LLC, led by Herencia, stepped in and recapitalized Metropolitan with a $207 million investment.

The recapitalization set off a broader reset. The bank would ultimately become Byline after that June 2013 restructuring—but the money was only half the move. The other half was leadership. Herencia brought in Alberto Paracchini to run the operating bank as CEO. Paracchini became President and CEO of Byline Bank in 2013, bringing nearly two decades in financial services and executive experience at places including Banco Popular North America, BXM Holdings, Inc., Popular Financial Holdings, and E-Loan—an early internet banking company.

It turned into a deliberate two-person system. Herencia, as Chairman, brought capital relationships, regulatory credibility, and the strategic frame. Paracchini, as CEO, owned the hard work of the turnaround: stabilizing operations, improving credit, and rebuilding the franchise day by day. Together, they had the right combination for a complicated job—fix a bank that had lost its footing, and do it in a way that created an engine for the next chapter.

In 2015—about a year before the Ridgestone deal—the company changed its name to Byline Bancorp Inc. and consolidated its subsidiaries.

That rename wasn’t cosmetic. “Metropolitan” carried the baggage of the crisis years. “Byline” signaled a clean slate. But the real work was underneath: cleaning up the loan book, working through troubled credits, rebuilding deposits, and getting the platform into shape for growth.

And during that rebuilding, the strategy began to crystallize. Chicago was still fragmented, filled with small banks feeling the weight of post-crisis regulation and rising technology costs. A healthy, well-capitalized operator with an integration playbook could become the natural buyer. Byline wasn’t just trying to survive anymore—it was getting ready to consolidate.

There’s also a deeper thread in the company’s history that gave it something many newer banks didn’t: longevity. As the company’s filings describe it, Byline traces its corporate lineage back to an Illinois incorporation on December 29, 1978 as North Community Bancorp, Inc., which owned Metropolitan Bank and Trust Company—a bank chartered in 1914. The company name changed to Illinois Financial Services, Inc. in 1987, then to Metropolitan Bank Group, Inc. in 1995, and finally to Byline Bancorp, Inc. in 2015.

That 1914 charter meant something. In an era when banks were disappearing, it was a signal of permanence—an institutional memory that customers and business owners could recognize, even after a near-death experience in 2008.

By late 2016, the turnaround was largely done. The bank was profitable, the balance sheet had been cleaned up, and management was ready to move from repair to expansion. Once the franchise was stabilized, Byline rolled into growth mode. In October 2016, it completed the acquisition of Ridgestone Financial Services, Inc. Then, in 2017, Byline executed its initial public offering, raising $125 million to fund the next leg: continuing to grow—and continuing to buy.

The stage was set for the IPO, and for the acquisition run that would follow.

V. Building the Platform: The Post-Merger Integration

In the IPO prospectus, everything was written in the careful language of process: the shares were expected to begin trading June 30, 2017 on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker “BY,” and the offering was expected to close the following week, subject to the usual conditions.

Then June 30 arrived, and it stopped being a plan.

Byline completed its initial public offering that day. Shares of the parent of the $3.3 billion-asset Byline Bank began trading at $19 per share—priced at the low end of the range—putting the company at a market value of about $540 million.

If you only looked at the pricing, you could read it as a mild letdown. But management saw the real win: Byline now had publicly traded currency. And in community banking, where growth is often bought as much as it’s built, stock isn’t just a valuation—it’s a tool.

“Armed with its new publicly traded currency, Byline is expected to be a buyer of smaller, privately held Chicago banks as it looks to grow,” one report noted. Herencia put it plainly: “We have a management team that is capable of running a much larger and more complex organization.”

Byline Bank itself had the kind of footprint that still mattered in Chicago. It was an Illinois state-chartered bank with more than a century of history, and it operated the fourth largest branch network in the city—55 branches across the Chicago metro area. The pitch wasn’t that Byline could be everything to everyone. It was that it could be the bank for the people and businesses who actually lived and worked around those branches: small and medium-sized companies, commercial real estate owners, financial sponsors, and local consumers. And beyond traditional banking, it had a specialty arm—Byline Financial Group—offering small ticket equipment leasing.

That positioning was intentional. Byline wasn’t going after JPMorgan’s Fortune 500 treasury clients. It was aiming for the middle: businesses too big for tiny one-office community banks, but still relationship-driven enough to feel underserved at the megabanks.

The Ridgestone acquisition—completed pre-IPO—also gave Byline a capability that was both profitable and differentiating: government-guaranteed small business lending. Ridgestone Bank was a leading Small Business Administration lender nationally, consistently ranked among the Top 10 SBA lenders in the country. With Ridgestone’s roughly $433 million in assets as of March 31, 2016, Byline could credibly claim real scale in SBA. Pro forma for the acquisition, it would be the 6th largest SBA originator in the U.S., and the largest SBA originator in Illinois and Wisconsin, based on 2015 origination volume.

This wasn’t just a league-table flex. SBA lending would become central to Byline’s identity because it fit the business model perfectly: government guarantees that reduced credit risk, fee income from selling the guaranteed portions, ongoing servicing fees, and—most valuable of all—deep relationships with exactly the kind of small business customers Byline wanted to keep for decades.

Ridgestone had previously held the title of No. 1 Wisconsin SBA lender, and Byline inherited that position. The company organized the capability into a dedicated business, Byline Small Business Capital, specializing in SBA and USDA lending and operating as a recognized preferred SBA lender. The message to the market was straightforward: “As a national leader in government guaranteed lending, we plan to continue to grow our SBA and USDA footprint.”

By September 30, 2017, Byline reported consolidated total assets of $3.3 billion, gross loans and leases of $2.2 billion, deposits of $2.5 billion, and stockholders’ equity of $459.5 million.

From there, the first stretch as a public company was about proving it could do what it promised: integrate, grow, and keep credit and culture intact. Assets rose from $2.4 billion at December 31, 2013 to $5.4 billion by June 30, 2019. Profitability held up too, with ROAA of 0.97% in 2018 and 1.01% year-to-date through June 30, 2019, while capital levels remained strong.

A roughly 1% return on assets wasn’t meant to dazzle. It was meant to reassure. It signaled a bank that could expand without blowing up, and a team that could absorb acquisitions without breaking the relationship-driven model that community banking depends on.

For investors, that was the early post-IPO proof point. Byline wasn’t just raising money and talking about consolidation—it was building a repeatable integration playbook: consolidate systems, optimize branches, preserve the culture, and keep moving.

And with a public currency in hand, it was ready for the next step: buying.

VI. The Acquisition Spree: Rolling Up Chicago

If the IPO gave Byline the currency, the years that followed showed what it planned to buy with it. From 2018 through 2020, the company began to look less like a single Chicago bank and more like a platform—one designed to consolidate a fragmented market without losing the relationship-driven feel that made those banks valuable in the first place.

The first big move came in May 2018, when Byline acquired First Evanston Bancorp for $178.6 million in cash and stock. First Evanston—the parent of First Bank & Trust—was headquartered in Evanston, Illinois, with 10 locations concentrated along Chicago’s North Shore suburbs, including three in Evanston. As of September 30, 2017, it had $1.1 billion in assets, $893.5 million in gross loans, and $993.7 million in deposits. It had also spent more than 20 years building a full-service franchise across commercial banking, retail, mortgage banking, and wealth management.

Strategically, the logic was simple: the North Shore is one of the most attractive banking corridors in the region. It tends to bring sticky deposits and a steady mix of high-quality commercial lending opportunities. Just as importantly, First Evanston added capabilities—wealth management and mortgage banking—that fit neatly with Byline’s goal of becoming the go-to bank for customers who wanted something more personal than a megabank, but more capable than a one-branch institution.

Then, in April 2019, Byline acquired Oak Park River Forest Bankshares, Inc. for $40.0 million in cash and stock.

On paper, these were straightforward community bank deals. In practice, they were Byline sharpening a repeatable playbook.

The pattern was consistent: find a bank with real local relationships and a culture that wouldn’t revolt inside a larger organization, pay a price that made sense, integrate the back office quickly, and keep the bankers who actually owned the customer trust. Byline wasn’t trying to win by hollowing out the very franchise it had just bought. The point wasn’t to slash for slash’s sake. The point was to spread the fixed costs—compliance, systems, reporting—across a bigger base, while keeping the front line intact.

Over time, that approach took on a few clear characteristics. First, geographic focus. Byline stayed close to home, largely in the Chicago metro area, where operational overlap and local knowledge created real synergy. Second, cultural alignment. It looked for banks that fit its emphasis on relationships and community presence. Third, pricing discipline. Management repeatedly emphasized that it would walk away from deals that didn’t clear their hurdles.

“Our M&A strategy has always been about finding the right partners in complementary markets that share our core values and approach to the business.”

And as the years went on, the same model kept showing up in larger form. In 2022, Byline and Inland Bancorp, Inc. announced a definitive merger agreement to combine Inland Bancorp and its subsidiary, Inland Bank and Trust, with Byline in a cash-and-stock transaction valued at approximately $165 million based on Byline’s closing stock price. The deal was framed as a scale-and-footprint move: it would strengthen Byline’s position as Chicago’s largest community bank with assets under $10 billion, expand into additional contiguous suburban communities, and create a combined organization with approximately $8.5 billion in assets.

When the transaction later closed, it drew attention for a different reason, too. Chicago-based Byline’s closing of its $129 million cash-and-stock acquisition of Inland—pushing Byline to $8.7 billion of assets and more than 40 branches across the Chicago and Milwaukee metro areas—landed at a moment when analysts were watching bank mergers for signs that deals might get trapped in regulatory delays.

Financially, Byline leaned on the same logic that makes bank M&A compelling when it’s done well: make the economics work without making the franchise worse. When the Inland deal was announced, Byline estimated cost reductions of about 30% of Inland’s expense base, expected the transaction to be more than 10% accretive to earnings per share in 2024, and projected that it would earn back tangible book value dilution in less than three years.

That mattered because in banking, acquisitions are notorious for destroying value. Integration takes longer than planned, cultures clash, customers quietly leave, and the “synergies” never quite show up. Byline’s ability to repeatedly structure deals that penciled out—and then integrate them without breaking the customer relationships—became a distinguishing trait.

By 2023, the market had started to treat Byline like the default consolidator. When a local bank board decided it was time—because founders were aging, because the fixed costs of regulation kept rising, because scale had shifted from advantage to requirement—Byline was increasingly the first call.

VII. The Pandemic Test: Banking Through COVID

March 2020 presented community banks with the kind of test they’re not supposed to survive. The world stopped moving. Businesses went dark. And loan portfolios that had looked perfectly reasonable in February suddenly felt like they were balanced on a knife edge. For a bank like Byline—with deep roots in commercial lending and commercial real estate—that anxiety was immediate. Restaurants had no diners. Retail tenants had no foot traffic. Offices were empty, and no one knew if they’d ever refill.

But the pandemic didn’t just create risk. It also created a once-in-a-generation opening: the Paycheck Protection Program.

As PPP rolled out, activity surged at banks like Live Oak Bancshares in Wilmington, N.C., Byline in Chicago, and Fulton Financial in Lancaster, Pa. They weren’t just getting lucky. They were fast. They knew how to underwrite government-backed small business loans. And they leaned into customers and industries that were more resilient—or simply into borrowers that bigger banks couldn’t, or wouldn’t, prioritize.

At the same time, the biggest banks were rerouting resources. Wells Fargo, JPMorgan Chase, and others pulled back on traditional SBA 7(a) lending as they focused on originating PPP loans. That shift created whitespace. Smaller, specialized lenders like Live Oak and Byline picked up share by targeting niches and handling larger loans.

This is where Byline’s earlier decisions paid off. The Ridgestone acquisition hadn’t just given the bank a line item called “SBA.” It had given it muscle memory: the people, the processes, and the systems to move government-guaranteed loans through the pipe. When megabanks were overwhelmed—and when smaller borrowers found themselves stuck in digital queues that never seemed to move—banks like Byline could do the simplest, most valuable thing in a crisis: pick up the phone and get it done.

Byline’s standing in SBA wasn’t new, either—it was already a top-tier player going into COVID. In September 2020, the Illinois District Office of the U.S. Small Business Administration named Byline Bank the Illinois SBA 7(a) Lender of the Year for dollar volume, based on its 2019 performance. In FY2019, Byline’s Illinois SBA-backed loans totaled over $130 million, supporting 1,202 jobs, according to the SBA. As an SBA Preferred Lender, Byline ranked fifth nationally that year for SBA 7(a) loan volume.

PPP also delivered something harder to measure, but arguably more important: relationship equity.

In March 2020, plenty of business owners learned a painful lesson about scale. When they called a megabank in a moment of panic, they often got a maze—hold times, forms, portals, and silence. Community banks offered a different experience. Byline could walk customers through the process, explain what mattered, and help them get funding across the finish line. For small businesses, that wasn’t just service. It was survival. And the goodwill didn’t disappear when the program ended.

Meanwhile, the nightmare scenario investors feared—mass defaults driven by commercial real estate and small business failures—never hit the way many expected. Federal stimulus, eviction moratoriums, and a more resilient economy blunted the wave.

“The product became very attractive for borrowers” because of that commitment, said Alberto Paracchini, Byline’s president and CEO. “I would say that, if you strip out some of that extraordinary effect, demand was good.”

When the dust settled, Byline came out of the pandemic with a clearer message about what it was building: not a nostalgic throwback, but a modern community bank platform that could move quickly when customers needed it most. In the moment when “community banking” was easiest to dismiss as obsolete, it turned out to be precisely what many businesses were looking for.

VIII. The Regional Bank Crisis & Flight to Quality

March 2023 delivered a different kind of test.

In just a couple of days, Silicon Valley Bank went from looking fine on paper to being shut down by regulators. Depositors rushed to pull their money, and on March 10, 2023, federal regulators closed SVB—at the time, the second-largest bank failure in U.S. history, behind Washington Mutual in 2008.

And it didn’t stop there. SVB’s failure exposed real stress points across the system and triggered a fast-moving panic about who might be next. Signature Bank failed soon after. First Republic followed. Within roughly two months, the U.S. had seen three of the four largest bank failures in its history.

For community and regional banks, the fear wasn’t abstract. It was intensely practical: if customers suddenly decided safety meant size, would deposits stampede toward the “too big to fail” giants?

Inside board rooms across the country, the conversation shifted from growth plans to survival math. The old post-2008 idea—too big to fail—started to morph into something closer to too small to survive. If confidence was going to concentrate in the largest institutions, smaller banks had one obvious response: get bigger, or find a buyer.

Byline, though, didn’t look like SVB. SVB’s problems were uniquely sharp: a highly concentrated depositor base, heavily uninsured, tied to venture-backed startups, paired with significant unrealized losses in its securities portfolio. Byline’s profile was different. It had a more diversified deposit base, a conservative approach to underwriting, and a book oriented around commercial real estate and small business lending—not a single industry ecosystem that could move in lockstep.

That distinction mattered. Many observers noted that SVB was unusually specialized, and that financial regulations were materially stronger than they had been heading into 2008. The system was under stress, but it wasn’t 2008 all over again.

Still, the shockwaves hit everyone. The crisis kicked off a brutal repricing of deposits across the industry. Banks had to pay up to keep and attract funding, as customers moved money into higher-yield alternatives. Net interest margins compressed. Even healthy, well-run banks felt it.

Byline had some insulation here, too. In relationship banking, service and responsiveness can matter as much as rate. Customers who bank with you because you know their business don’t always leave at the first basis point. That doesn’t eliminate pressure—but it can slow the bleed.

In the aftermath, consolidation went from a long-term trend to an urgent strategy. One unexpected second-order effect: more open discussion about whether regulators might be willing to allow mergers, seeing them as a path to a more stable regional banking sector without necessarily creating more complexity.

For Byline, that environment reinforced what it had been building toward all along. If fear and higher costs pushed more small banks to reconsider independence, acquisition opportunities didn’t dry up—they multiplied. Banks that had been holding out suddenly faced sharper questions from their own customers, their own shareholders, and their own directors.

Byline’s platform—cleaner, larger, and already practiced at integration—was built for exactly that moment.

IX. Recent Moves & Current Strategy

After spending years building an integration machine in Chicago, Byline kept doing what consolidators do best: keep rolling the platform forward, one culturally compatible deal at a time.

Byline and First Security Bancorp announced a definitive merger agreement to combine First Security Bancorp and its wholly owned subsidiary, First Security Trust and Savings Bank, with Byline in a cash-and-stock transaction valued at approximately $41.0 million, based on Byline’s closing stock price. The pitch was familiar and deliberate: two franchises with aligned cultures, one stronger Chicago commercial bank. And it came with a positioning statement Byline has worked toward for years—further solidifying its place as Chicago’s largest community bank with assets under $10 billion.

First Security was a classic community bank fit. Headquartered in Elmwood Park, Illinois, it reported total assets of $354.8 million, total loans of $201.4 million, and total deposits of $321.8 million as of June 30, 2024. It had served its communities for more than 75 years, offering the kind of commercial and community banking services that thrive on local relationships and trust.

Then the deal moved from announcement to reality. Byline completed the merger with First Security Bancorp, Inc. and First Security Trust and Savings Bank, and effective April 1, 2025, First Security merged with and into Byline Bank. With that, Byline’s total assets rose to approximately $9.8 billion.

In the company’s own framing, the April 1, 2025 acquisition brought Byline to roughly $9.9 billion in combined total assets, with approximately $7.2 billion in loans and approximately $7.8 billion in deposits. The message was consistent: this acquisition further reinforced Byline’s identity as a preeminent commercial bank in Chicago.

Now, the bank is closing in on a milestone that matters in banking in a way it doesn’t in most other industries: the $10 billion asset threshold. Byline anticipated crossing $10 billion in assets by late 2025 or early 2026.

That line isn’t symbolic. Crossing $10 billion triggers enhanced regulatory scrutiny, including the Durbin Amendment’s interchange fee caps on debit cards. Many banks slow their growth as they approach it, taking time to build the operational and compliance infrastructure needed for the next level of oversight. Byline’s posture suggested something different: management believed the benefits of more scale were worth the added burden—and that it was ready to operate in that heavier regulatory weight class.

External observers began to signal the same confidence. On March 18, 2025, Kroll Bond Rating Agency, LLC (KBRA) upgraded the credit ratings of both Byline Bancorp, Inc. and its subsidiary, Byline Bank. KBRA upgraded Byline Bancorp’s senior unsecured debt rating to BBB+, its subordinated debt rating to BBB, and its short-term debt rating to K2. KBRA also upgraded Byline Bank’s deposit and senior unsecured debt ratings to A-, and its subordinated debt rating to BBB+.

Ratings upgrades can sound wonky, but the implication is straightforward: a third party was publicly validating Byline’s credit quality and financial stability. And investment-grade ratings aren’t just bragging rights—they can influence funding costs and access to wholesale funding markets.

At the same time, Byline was behaving more like a mature public company in how it managed capital. Byline announced that its Board of Directors approved a new stock repurchase program authorizing the company to repurchase up to 2.25 million shares of its outstanding common stock—approximately 4.9% of shares outstanding. The program is set to be effective January 1, 2026 and remain in effect through December 31, 2026. As the company put it: “The new stock repurchase program reflects our confidence in the Company’s capital position, and our ability to support the long-term growth trajectory of the Byline franchise.”

Alongside buybacks, shareholder returns were rising through dividends, too. On January 21, 2025, the Board declared a cash dividend of $0.10 per share, an 11.1% increase from the prior quarterly dividend of $0.09 per share.

X. The Byline Business Model Deep Dive

So what, exactly, is Byline selling—and why does it work in the narrow space between the megabanks and the tiny community banks that never got to scale?

At the simplest level, Byline Bancorp, Inc. is the holding company for Byline Bank, and the product set looks familiar: deposit accounts, debit cards, and digital banking across online, mobile, and text. It makes loans. It offers treasury management. It provides wealth services.

But the differentiation is in who it’s built for, and how it delivers.

Byline focuses on small and mid-sized businesses, commercial real estate owners, and financial sponsors—plus consumers who still want a bank where a real person can actually solve a problem. The bank’s sweet spot is relationship-driven customers who often feel like an afterthought at the giants: businesses that want speed, attention, and a lender who can structure something more thoughtful than a generic “computer says no.”

That customer profile is fairly consistent: small businesses typically doing about $1 million to $50 million in annual revenue, commercial real estate investors, professional service firms, and owner-operators who care about responsiveness as much as price.

On the balance sheet, the tilt is also clear. Around 75% of Byline’s assets sit in loans, and the book skews commercial. That’s a very different DNA than a consumer-heavy retail bank, and it’s why Byline lives and dies by underwriting discipline and deposit relationships.

The revenue engine is a blend of spread income and fee businesses. Net interest income is the core, but Byline has built meaningful fee streams around it. SBA lending generates gain-on-sale income and ongoing servicing fees. Equipment leasing through Byline Financial Group adds another lane. Wealth management and trust services deepen relationships and make customers stickier over time.

If there’s one “secret sauce” Byline keeps returning to, it’s credit culture. The bank emphasizes a strict separation between business development and credit decision-making, with credit decisions made locally but within consistent underwriting standards. Management points to continuous risk-and-return evaluation and tight monitoring limits at the loan, relationship, product, and portfolio levels. The goal is simple: grow without stretching so far that the next downturn becomes existential.

That matters because the banks that didn’t make it through 2008 usually failed the same test: they let growth incentives overwhelm risk controls. Byline’s structure is designed to keep that from happening again.

The numbers in 2024 reflected a bank that, at least for now, is executing on that model. Byline reported net income of $120.8 million, diluted EPS of $2.75, ROA of 1.31%, return on average tangible common equity of 14.85%, and an efficiency ratio of 52.45%, with revenue up 5.2% year over year—an indication of positive operating leverage even in a moderating-rate, mixed macro backdrop.

Those metrics aren’t just scorekeeping. They describe a bank that’s doing three hard things at once: earning strong returns, keeping expenses in check, and maintaining credit performance while staying heavily commercial.

For investors tracking whether the model keeps working, two KPIs matter most:

-

Net Interest Margin (NIM): The spread between what Byline earns on loans and what it pays for deposits. In Q4, net interest income was $88.5 million and net interest margin was 4.01%. More recent results showed a 4.07% NIM. In community banking, a NIM above 4% is a real strength, and it suggests Byline has been able to protect its economics despite the industry-wide fight for deposits.

-

Credit Quality (Non-Performing Assets/Total Assets): The early-warning signal for whether credit problems are building. Byline reported non-performing assets at 0.71% of total assets. For a commercial-focused lender, staying below 1% is generally a sign that the credit book is holding up.

XI. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Porter's 5 Forces:

Threat of New Entrants: HIGH but mitigated On paper, banking looks like a business with lots of competition and not much switching friction. In reality, starting a new bank in the post-Dodd-Frank world is hard, slow, and expensive. Fintechs can absolutely pick off profitable slices—payments, lending niches, consumer deposits—but they struggle to recreate the full-stack commercial bank relationship: deposits, treasury management, credit, and advice, all wrapped in trust.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE For a bank, the key “input” is deposits. And since the 2023 regional bank crisis, that input has gotten more expensive. Customers became more rate-aware, and the market forced banks to compete harder to keep funding stable. The other supplier is talent—especially proven commercial bankers—and their price has climbed too.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-HIGH Commercial customers can shop. The best borrowers do shop. But for a business with operating accounts, treasury management, and lending all tied together, switching isn’t as easy as opening a new checking account. The more integrated the relationship, the higher the friction—which is why banks fight so hard to become the primary institution, not just the lender on one deal.

Threat of Substitutes: HIGH Byline isn’t just competing with other banks. It’s competing with online banks, non-bank lenders, fintech platforms, and especially private credit funds that have grown rapidly by offering commercial loans that used to be a bank’s bread and butter. Substitutes don’t have to replace the whole bank—just the most profitable products—to create real pressure.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH Chicago is a knife fight. Megabanks like Chase, Bank of America, and BMO have scale and convenience. Wintrust runs a community-bank model with a bigger footprint. Credit unions have structural advantages. And the remaining community banks are still out there, protecting their best relationships. Everyone wants the same things: stable deposits and high-quality borrowers.

Hamilton's 7 Powers:

Scale Economics: WEAK-MODERATE Scale matters in community banking—but mostly in unglamorous places. Compliance, risk management, and technology are heavy fixed costs, and a larger balance sheet helps carry them. Still, this isn’t software. Being twice as big doesn’t make you twice as profitable, and it doesn’t lock the market.

Network Economics: WEAK There’s no meaningful network effect in traditional relationship banking. Your customers don’t become more valuable just because other customers bank with you, the way they would on a marketplace or payments network.

Counter-Positioning: MODERATE Byline’s pitch—relationship banking with speed and local decision-making—does counter-position it against megabanks that often can’t profitably deliver that level of attention to mid-market customers. The catch is that this gap narrows over time as large banks invest more in middle-market coverage and tools.

Switching Costs: MODERATE-STRONG Switching costs are where business banking gets defensive. Treasury management setups, operating accounts, payment rails, and credit relationships create real hassle and real risk for a customer to move. That friction doesn’t make customers permanent—but it buys time and makes service quality matter.

Branding: WEAK-MODERATE Reputation matters locally, and it matters a lot in moments of stress. But “Byline” isn’t a household name the way Chase is, and it doesn’t have the long-cultivated local brand strength of a Wintrust. Branding helps, but it’s not an unbreakable shield.

Cornered Resource: WEAK There’s no secret ingredient that can’t be hired. Great bankers are mobile, and when a relationship manager leaves, relationships can follow. Byline can build loyalty, but it can’t fully “own” it.

Process Power: MODERATE This is where Byline has something real: the accumulated muscle memory of underwriting discipline, operating controls, and a repeatable integration playbook. Those processes compound over time. But they’re still replicable by other well-run banks.

Conclusion on Competitive Position: Byline’s advantages are real, but modest. This isn’t a power-law business where one winner takes the market. The edge comes from execution—running a clean balance sheet, retaining relationships, integrating acquisitions, and staying disciplined when competitors get aggressive. The most durable position here is “scale within a niche”: big enough to fund modern banking, small enough to stay responsive, and focused enough to win relationships that megabanks routinely under-serve.

XII. The Existential Questions & Bear vs. Bull Case

The Bear Case:

Community banks are dinosaurs. The bear view is simple: fintech doesn’t have to replace the whole bank to do damage. It just has to skim the best parts—payments, deposits, point-of-sale lending, cash-flow underwriting—while offering a slick, digital-first experience. And as younger business owners take over, the fear is that the “call your banker” relationship model that worked for prior generations won’t carry the same weight with millennials and Gen-Z entrepreneurs.

Commercial real estate exposure is a time bomb. Byline is a commercial bank in a city still working through the post-pandemic office reset. Chicago’s downtown office market remains under pressure, and remote work has structurally reduced demand. Even if underwriting has been conservative, concentrations in CRE can turn from “stable and boring” to “suddenly everyone’s worried” fast, especially if valuations keep adjusting.

NIM compression ahead. If the Federal Reserve moves into meaningful rate cuts, Byline’s asset-sensitive balance sheet could see margin pressure. Loan yields tend to reprice quickly, while deposit costs often fall more slowly. In other words, earnings can get squeezed in the transition—even if credit stays fine.

Scale still insufficient. Even as Byline approaches $10 billion in assets, it’s still operating in the shadow of much larger competitors—Wintrust at more than $60 billion, and the national giants with effectively unlimited technology budgets. The bear concern is that the cost of competing—on digital experience, fraud, compliance, and product breadth—keeps rising faster than mid-sized community banks can keep up.

M&A risk. Serial acquirers rarely get every deal right forever. Eventually, someone overpays, misjudges credit, loses key bankers, or underestimates integration complexity. Each acquisition brings a new set of systems, cultures, and customer relationships that can break if handled poorly.

Geographic concentration. Byline’s identity is Chicago, and that’s both a strength and a vulnerability. Bears point to Midwest headwinds—population outflows, state-level fiscal challenges, and the long-running migration to warmer, faster-growing Sunbelt markets—as reasons a Chicago-centric growth story could be structurally tougher than it looks.

The Bull Case:

The consolidator trade. The bull case starts with the same industry facts and flips the conclusion: in a world where sub-scale banks are being squeezed, the winner isn’t the bank that resists consolidation—it’s the one that becomes the buyer. Byline has positioned itself as the disciplined roll-up platform, and if it keeps executing, that compounding can be powerful. The pool of potential targets hasn’t disappeared; if anything, the pressures that create sellers keep stacking up.

Relationship banking endures. For many small and mid-sized businesses, banking still isn’t an app—it’s a problem-solving function. They want speed, judgment, and a decision-maker who understands their business. Not every borrower wants to explain nuance to a portal or a chatbot, especially when something goes sideways. In that world, the human relationship isn’t nostalgia; it’s a real product.

Flight to quality. The 2023 regional bank crisis didn’t just create fear—it created differentiation. Banks with diversified deposits and conservative underwriting looked safer. Byline’s profile fits that “boring is good” category, and that stability can attract customers when confidence matters most.

Valuation is undemanding. Byline trades below tangible book value and at a single-digit earnings multiple. If it continues performing and sentiment normalizes, there’s room for the multiple to expand—without needing heroic growth assumptions.

M&A optionality. Consolidators can also become targets. A larger regional bank that wants Chicago market share could view Byline as a ready-made platform. Wintrust, Old National, or an out-of-market buyer might find the franchise appealing.

Management track record. This is where bulls keep coming back: Herencia and Paracchini have been running this play for more than a decade. They executed the turnaround, built the platform, and integrated multiple acquisitions. That history doesn’t guarantee the future, but it’s a meaningful signal in an industry where bad decisions compound quickly.

The verdict: this is a “show me” story. The bet works if Byline keeps doing three hard things at once: growing without stretching on credit, integrating acquisitions without losing relationships, and navigating the real overhangs—especially commercial real estate. The skeptics will keep waiting for the model to break. The optimists will keep watching for evidence that it doesn’t.

XIII. Lessons for Founders, Operators & Investors

Timing is everything. Herencia and his investor group stepped into Metropolitan Bank in 2013, when the post-crisis hangover was still heavy and plenty of franchises were priced like they’d never recover. They bought into distress, did the hard, unsexy work to fix what was broken, and positioned the bank to benefit as conditions normalized. In cyclical industries, the entry point doesn’t just influence returns—it often determines whether the whole strategy works.

Consolidation playbooks create value. When an industry is fragmenting and scale becomes a requirement, the winners are rarely the loudest innovators. They’re the disciplined consolidators. Byline’s edge wasn’t “doing deals.” It was doing repeatable deals: knowing what it would pay, integrating quickly, keeping credit standards intact, and holding onto the bankers who held the relationships.

The boring business advantage. Community banking is regulated, capital-intensive, and built on trust. That sounds limiting—until you realize those same constraints make the business harder to enter and harder to displace. Not every great outcome comes from disruption. Some come from showing up every day, compounding credibility, and being the institution people rely on when things get messy.

Crisis preparation pays off. Byline’s entire arc is a reminder that risk management isn’t a department; it’s the business. Conservative underwriting and a steady credit culture didn’t just help it look good on paper. They helped it stay standing through multiple stress moments—when weaker banks found out, in real time, what corners they’d cut.

Local vs. global matters. Byline didn’t win by trying to be everywhere. It won by being deeply useful in a specific place, for a specific kind of customer. In banking, local knowledge can still translate into better credit decisions and stickier relationships. You don’t need the biggest footprint. You need a footprint where you can consistently be the first call.

The middle-market squeeze is real. There’s a size range where banking gets brutally hard: too big to operate like a tiny community bank, too small to comfortably fund modern compliance, technology, and talent. If you’re stuck there, the math doesn’t care about your history. You either grow into scale—or you accept shrinking returns and rising vulnerability.

Cultural integration trumps cost synergies. Bank acquisitions can look great in a spreadsheet, right up until customers and lenders walk out the door. Byline’s M&A success wasn’t built on slash-and-burn cost cutting. It came from protecting the relationship culture that made those banks valuable in the first place. You can’t “synergy” trust.

Patient capital wins. This isn’t a winner-take-all story, and it’s definitely not a get-rich-quick one. The payoff comes from years of consistent decisions: clean up, build, buy carefully, integrate well, repeat. The investors who backed Herencia in 2013 weren’t betting on a sudden miracle. They were betting on compounding.

XIV. Epilogue: What's Next for Byline?

The 2025 outlook sets up the next act—and it’s a familiar Byline tension: opportunity created by chaos, paired with a higher bar for execution.

Management’s tone has been steady. As the company put it: “First quarter results were highlighted by steady earnings and profitability, net interest margin expansion, stable deposit and loan growth, repayment of our term loan, and controlled expenses. As we navigate the current landscape, we believe our continued strong capital position reflects a well-managed balance sheet and strong risk management practices.”

The next obvious plot point is the one the industry obsesses over: $10 billion in assets. Crossing it isn’t just a vanity milestone. It brings Durbin Amendment interchange fee restrictions and enhanced regulatory oversight—real costs that can punish a bank that isn’t operationally ready. Byline’s posture suggests it thinks the trade is worth it: more scale, more ability to fund technology and compliance, and more gravity with commercial customers.

Then there’s the question that hangs over every successful consolidator: do you keep consolidating, or do you get consolidated?

Byline’s consistent profitability and its track record of clean integrations make it easier to imagine as a target than many peers. Wintrust is the second largest banking company in Chicago, and a combination with a larger regional player could create real weight in the Chicago metro area. Whether that ever happens depends less on speculation and more on the usual banking realities—price, timing, and whether management and the board believe independence still offers the best compounding path.

Meanwhile, the competitive battlefield keeps shifting under everyone’s feet. Big banks continue pouring money into digital capabilities and middle-market coverage. Fintechs keep picking at specific products. Private credit funds compete aggressively for commercial loans, often with speed and structures banks can’t—or won’t—match. In this environment, whatever “moat” exists in community banking isn’t a castle wall. It’s upkeep: service, credit discipline, and constant reinvestment.

Which is why technology bets matter more every year. Banks that can apply AI to underwriting, customer acquisition, and operational efficiency will have a real edge. Byline’s long-term competitiveness will be shaped by how much it can invest directly, and how smart it is about partnering when building in-house doesn’t make sense.

And through all of it, Byline keeps returning to the same core claim: culture and relationships scale if you protect them. When the First Security deal closed, the company framed it that way: “We are pleased to welcome First Security customers, colleagues and stockholders to Byline. The closing of this transaction brings together two strong, culturally aligned, community-focused franchises that strengthens Byline's position as the preeminent commercial bank in Chicago.”

Zooming out, that’s the bigger story anyway. Community banking in America is still sitting on an existential question: can relationship-driven institutions survive against digital-native competitors, and is there a sustainable middle ground between megabanks and neobanks? If local banks disappear, what happens to the small businesses and communities that relied on them for judgment, not just capital?

Byline’s arc argues for cautious optimism. A well-managed community bank—big enough to carry the fixed costs, disciplined enough to avoid credit blowups, and focused enough to win relationships—can still thrive. Personal attention, local knowledge, and quick decisions are not obsolete. For many customers, they’re the product.

But the optimism has to be earned, continuously. Regulation keeps getting more complex. Technology keeps getting more expensive. Competition keeps getting more intense. Survival isn’t a one-time turnaround story; it’s an operating requirement.

For long-term investors, Byline is a bet on what American banking becomes, not what it was. If you believe community banks still have a durable role—serving small businesses, commercial real estate investors, and relationship-oriented consumers—Byline is one of the cleaner vehicles for that thesis.

It has already lived through multiple stress tests: the post-2008 wreckage, the regulatory surge, COVID-19, and the 2023 bank failures. Each one reshaped the industry—and Byline used each one to get a little bigger, a little more relevant, and a little more practiced at the only thing that matters in banking: staying trusted.

What comes next will decide whether that resilience turns into sustainable outperformance as the bank enters a new weight class.

The story continues.

XV. Further Reading & Resources

If you want to go deeper—into the numbers, the industry context, and the playbooks behind bank consolidation—these are the best places to start.

Top 10 Resources:

- Byline Bancorp SEC filings (10-Ks, proxy statements, investor presentations) — The primary source for financials, strategy, risk factors, and management commentary

- "The Outsiders" by William Thorndike — A great lens on capital allocation and why disciplined serial acquirers can compound value

- SNL Financial / S&P Global Market Intelligence — The go-to database for bank M&A comps, market share, peer benchmarking, and deal history

- FDIC Historical Statistics on Banking — The cleanest way to understand long-term U.S. banking trends, failures, and consolidation

- "The House of Morgan" by Ron Chernow — Big-picture banking history that helps put modern cycles in context

- Keefe, Bruyette & Woods (KBW) research — Sector research and frameworks used by many bank investors and executives

- Federal Reserve community banking research — Thoughtful work on community bank economics, regulation, and credit cycles

- American Banker & Bank Director Magazine — Industry reporting on deals, regulation, and what bank management teams are actually worried about

- Chicago Federal Reserve publications — Regional economic data and banking analysis with a Midwest lens

- Wintrust Financial filings — A useful comparator for a scaled, Chicago-area relationship banking model

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music