Babcock & Wilcox: From Civil War Boilers to Nuclear Renaissance

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture this: it’s the predawn hours of March 28, 1979. Inside a control room in Pennsylvania, operators at the Three Mile Island nuclear plant face a wall of alarms—more than a hundred of them going off at once. Somewhere in that noise is the signal that matters, and they have to find it fast.

The reactor they’re fighting to stabilize came from a company founded more than a century earlier by two childhood friends in Rhode Island. The same company whose boilers helped power Thomas Edison’s first electrical stations, helped carry Theodore Roosevelt’s Great White Fleet across the oceans, and helped keep the “arsenal of democracy” running through two world wars.

Babcock & Wilcox.

For most of American history, that name meant industrial muscle: steam, steel, and engineering that scaled with the country’s ambition. But by 2025, the image has flipped. The company that once stood for conservative, best-in-class engineering is fighting for oxygen—staring down debt maturities, living under going-concern warnings, and trying to answer a brutal question: can a 158-year-old industrial icon reinvent itself fast enough for a world sprinting toward decarbonization?

That’s the tension at the heart of this story. How did the company that invented the water-tube boiler—the breakthrough that made modern steam power safer and more scalable—end up bankrupt, restructured, and now trying to build its future around hydrogen production technology and the power needs of AI data centers?

B&W began in 1867 in Providence, Rhode Island. Stephen Wilcox had a patented water-tube boiler design. George Babcock saw what it could become. Together, they built a company whose trajectory would end up tracking America’s: steam age to electric age to atomic age; dominance to disruption; stability to leverage; and finally to a scramble for a credible third act.

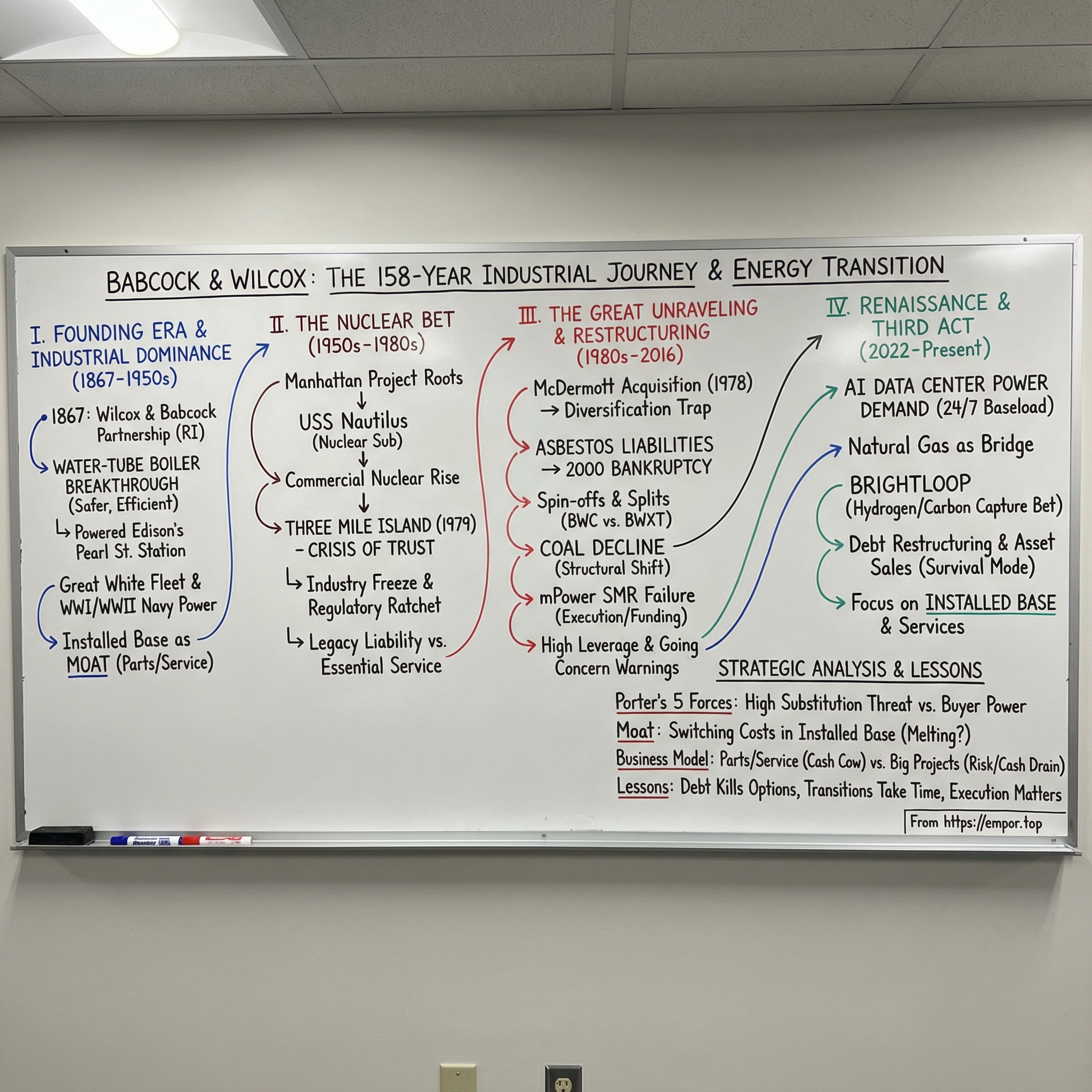

We’ll tell that story in four eras. First, the founding era, when B&W’s boiler becomes the standard for safe, efficient steam generation—and the company becomes a quiet backbone of U.S. industry. Second, the nuclear bet, when B&W helps usher in the atomic age, only to have its reputation forever linked to Three Mile Island. Third, the great unraveling: spin-offs, the coal market falling out from underneath it, and bankruptcy. And finally, the present—where B&W finds itself in an almost ironic position: a company built on fossil-era expertise that’s suddenly useful again, because AI data centers are forcing the world to confront an inconvenient truth about electricity. Reliability matters, and renewables alone can’t always carry the load.

Why does any of this matter beyond one company’s survival? Because B&W is a case study in the energy transition as it really is—not as we wish it were. Can a legacy industrial company genuinely pivot to cleaner technology, or does it just rename yesterday’s capabilities and call it strategy? What happens when climate imperatives collide with the practical requirement to keep a digital economy powered 24/7? And most importantly: if the next wave is real, can a company survive long enough to catch it—when it’s still tangled in the wreckage of the last one?

II. The Founding Era & Industrial Dominance (1867-1950s)

In the small industrial city of Westerly, Rhode Island, a young Stephen Wilcox became fixated on a problem that was both common and horrifying in early America: boiler explosions. In the pre-code days of steam power, they weren’t rare accidents. They were a recurring public disaster.

One of the worst came in February 1850, when a boiler blast tore through the A.B. Taylor & Co. hatters’ manufacturing headquarters on Hague Street in lower Manhattan. The building collapsed into its foundation. More than 60 workers—many of them young boys—along with bystanders were killed, and another 70 were injured.

That kind of event didn’t just make headlines. It left scars. And it helped set Wilcox on a mission: make steam power safer without sacrificing performance.

In 1857, in the wake of Hague Street, Wilcox introduced a new idea: the water-tube boiler. It was a major leap toward safer, more efficient steam generation. But the first versions weren’t perfect. It took years of tinkering—and eventually a partnership with his childhood friend, George Babcock—to turn the concept into a product the world would trust.

Babcock came from an inventive family. Born in New York State, he moved to Rhode Island at age 12 and met Wilcox there. At 19, he launched a newspaper and printing company. Working with his father, he helped invent a polychromatic printing press. But Babcock’s real pull was engineering. During the Civil War, he worked as chief draftsman at the Hope Iron Works in Providence—exactly the sort of place where industrial ideas became industrial reality.

In 1867, the two finally formalized what they’d been building toward. They received patents for the “Babcock & Wilcox Non-Explosive Boiler” and the “Babcock & Wilcox Stationary Steam Engine.” That same year, they formed Babcock, Wilcox and Company with Joseph P. Manton, founder of Hope Iron Works, to manufacture the new boiler at scale.

The breakthrough was deceptively simple: instead of holding water in one big shell, their design spread it through many small tubes. That mattered because the classic shell boiler had a terrifying failure mode—overheat it, rupture a seam, and you could get an explosion violent enough to level a building. With the water distributed across tubes, the system resisted catastrophic failure. It also had a second advantage that made it economically irresistible: it could generate higher-pressure steam, more efficiently, than the designs it replaced.

And they hit the market at exactly the right moment.

Post-Civil War America was industrializing at full throttle. Factories needed power. Railroads needed locomotion. Ships needed propulsion. Steam was the enabling technology of the age, and demand for safer, higher-performance boilers was effectively limitless.

In 1878, Thomas Edison bought B&W boiler No. 92 for his Menlo Park laboratory. It was a small purchase with big implications. When Edison later needed boilers for his electrical generating stations, he turned to the same company that had powered his workbench.

Soon B&W boilers were driving some of the nation’s first central electrical stations in Philadelphia and New York City, including Edison’s Pearl Street station in Manhattan. This wasn’t just another customer win. The electric utility industry was being born, and B&W equipment was there at the moment of ignition.

But the founders also understood something that many inventors don’t: building the better machine isn’t enough. You also have to build trust in the machine—industry-wide.

George Babcock didn’t just file patents for pumps, steam engines, and new boiler designs with Wilcox. He also helped push the entire field toward safer standards through professional leadership, including serving as ASME’s sixth president. He advocated for the kind of codes that would govern how boilers were designed, manufactured, maintained, and operated. By the time the ASME Boiler Code was adopted decades later, B&W’s fingerprints were already on the thinking behind it.

Babcock and Wilcox died just 19 days apart in 1893. But by then they’d created more than a product line. They’d created an institution: a company known for engineering quality, safety, and service.

By the turn of the century, that reputation translated into ubiquity. In 1902, New York City’s first subway line was powered by B&W boilers. In 1907 and 1909, Theodore Roosevelt’s Great White Fleet ran on B&W boilers. That fleet’s global circumnavigation was a deliberate performance of American industrial and military reach—and B&W was in the engine room of the story.

War made the relationship between engineering and national power even more explicit. In World War I, B&W’s marine boilers powered Navy destroyers and emergency fleets. The company scaled production using shop-assembly techniques it had begun in 1909—an early move toward industrialized, repeatable manufacturing rather than bespoke builds.

World War II was the culmination of that capability. From 1941 to 1945, B&W designed and delivered 4,100 marine boilers for combat and merchant ships. By the end of the war, B&W boilers powered 95 percent of the U.S. fleet sitting in Tokyo Bay at Japan’s surrender. It’s hard to find a cleaner data point for industrial dominance than this: when America accepted victory, it did so atop B&W steam.

And during the same period, B&W’s precision manufacturing took on an entirely new kind of importance. Between 1943 and 1945, the company provided components, materials, and process development for the Manhattan Project. The skills that made boilers safe and reliable—metallurgy, high-pressure systems, manufacturing discipline—also made B&W useful to the most secret engineering program in American history. This wasn’t a side quest. It was a bridge into the next era.

After the war, B&W kept doing what it did best: build the machinery that moved the world. Between 1949 and 1952, it provided eight boilers for the SS United States, the fastest ocean liner ever constructed. By the early 1950s, B&W had become what people would later describe as “the GE of boilers”—a dominant supplier with installations across hundreds of plants and facilities, in the U.S. and abroad.

And if you’re trying to understand why B&W keeps reappearing, decade after decade, even after the industry turns on it—this era gives you the answer. The real product wasn’t only the boiler. It was the installed base. Once a B&W boiler went into a plant or a ship, it created years—often decades—of parts, service, maintenance relationships, and deep customer dependency. Long before anyone called it a moat, B&W was building one the old-fashioned way: one piece of mission-critical equipment at a time.

III. The Nuclear Bet: Atoms for Peace & The Manhattan Project's Children (1950s-1980s)

In the early 1950s, a driven naval officer named Hyman Rickover was assembling a team to do something that still sounded like science fiction: build a practical nuclear-powered submarine.

But the real starting gun for American civilian-industry participation in nuclear power had gone off earlier. In April 1946, the Manhattan Project, through Oak Ridge, invited a select group of large industrial companies—along with the Navy, universities, and other federal agencies—to loan technical talent into the effort to develop, design, and build the world’s first nuclear power reactor. Companies showed up for all the reasons you’d expect: curiosity, fear of missing out, and genuine conviction that an entirely new energy era was beginning. The roster reads like a mid-century roll call of American industrial power: General Electric, Westinghouse, Allis-Chalmers, chemical giants like Monsanto, and boiler fabricators like Babcock & Wilcox.

For B&W, the Manhattan Project wasn’t just a prestige assignment. It was a head start.

Between 1953 and 1955, B&W designed and fabricated components for USS Nautilus (SSN-571), the world’s first nuclear-powered submarine. Nautilus didn’t just add a new ship to the fleet. It rewrote the rules of naval warfare. Diesel submarines had to surface regularly to recharge their batteries. A nuclear submarine could stay submerged for months. And in August 1958, Nautilus proved the point with a submerged transit of the North Pole. The strategic implications were enormous—and B&W’s engineering was part of the leap.

That success opened the door to something even bigger: commercial nuclear power. President Eisenhower’s Atoms for Peace program promised that the technology that powered submarines could power cities. B&W, alongside Westinghouse and General Electric, moved to become a major player in the new market.

In 1961, B&W designed and supplied the reactors for the world’s first commercial nuclear ship, NS Savannah. Soon after, it stepped into commercial power generation. In 1962, B&W designed and furnished reactor systems for its first commercial reactor, Indian Point, using HEU 233.

B&W’s reactor approach wasn’t identical to its rivals’. Its pressurized water reactor design used once-through steam generators—more efficient in theory, but also less forgiving in practice. The Three Mile Island Unit 2 reactor, for example, was a Babcock & Wilcox 900 MWe PWR with once-through steam generators and an unusually small primary coolant system volume.

By the mid-1970s, B&W had become one of the major nuclear reactor vendors in the United States, alongside Westinghouse, General Electric, and Combustion Engineering. Utilities were ordering plants to keep up with electricity demand, and nuclear looked like the future.

Then came March 28, 1979.

Three Mile Island Unit 2 (TMI-2), near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, suffered a partial meltdown that began around 4:00 a.m. The incident released radioactive gases and radioactive iodine into the environment. It remains the worst accident in U.S. commercial nuclear power plant history.

The tragedy wasn’t one single failure. It was a chain reaction of equipment behavior, human interpretation, and institutional weakness. The Kemeny Commission noted that Babcock & Wilcox’s pilot-operated relief valve (PORV) had failed before—11 times, nine of them in the open position—allowing coolant to escape. Even more ominously, much of the early sequence at Three Mile Island had effectively been duplicated 18 months earlier at another B&W plant, the Davis–Besse Nuclear Power Station. At Davis–Besse, operators recognized the valve issue in about 20 minutes; at Three Mile Island, it took about 80. Davis–Besse was operating at 9% power; Three Mile Island was running at 97%. And despite B&W engineers recognizing the pattern, the company failed to clearly notify customers about the valve issue.

The blame did not land on any one entity. Investigators criticized Babcock & Wilcox, Metropolitan Edison, General Public Utilities, and the NRC for gaps in quality assurance and maintenance, inadequate operator training, failures to communicate safety information, poor management, and complacency.

And in the middle of the chaos was a grimly modern problem: the people who knew the design best couldn’t reach the people running it. For five hours, B&W—trying to help from its headquarters in Virginia—couldn’t get through to the operators. As journalist Mike Gray described it, the designers in Lynchburg had to route information through an NRC office in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania, then to Unit One, and finally by runner to Unit Two, where someone would physically read a gauge, run back, and report what they saw.

The aftermath didn’t just hit B&W. It hit the entire industry. Between 1980 and 1984, 52 U.S. nuclear reactors were canceled. The accident didn’t singlehandedly kill nuclear power in America, but it froze its momentum. Similar reactors were shut temporarily. Licensing slowed to a crawl. And for years, no utility in the United States ordered a new reactor—stretching from 1979 into the mid-1980s.

Yet B&W survived when others pulled back, largely by leaning into a reality it had been building for a century: the installed base. Even in a nuclear winter, the existing fleet still needed maintenance, parts, refueling support, upgrades, and eventually decommissioning work. And because B&W’s designs were proprietary, the switching costs were real—only B&W could service certain B&W reactors.

That contradiction would become the company’s defining pattern for the next four decades: a brand forever linked in the public mind to a historic failure, and a business that remained indispensable to the customers living with the hardware every day.

IV. The Diversification Era & Private Equity Carousel (1980s-2000s)

In 1978—just before Three Mile Island would change the nuclear industry forever—Babcock & Wilcox was bought. The buyer was McDermott, an offshore construction company whose fortunes rose and fell with oil prices and drilling cycles. The price: about $748 million. The logic was simple: stabilize a volatile marine-construction business by adding a steadier, utility-facing industrial franchise.

The deal closed on March 31, 1978, after a drawn-out bidding war with United Technologies Corporation. United Technologies—home to Pratt & Whitney and Carrier—saw B&W as a natural expansion into power generation. McDermott saw something else: a diversification move that could smooth out the bumps in its core business.

On paper, it made sense. Both companies lived in the broad orbit of “energy.” Both were heavy-industry operators who knew steel, welding, and big-ticket projects. And B&W’s installed base—boilers, services, long-lived contracts—looked like exactly the kind of recurring cash flow a cyclical parent would crave.

In reality, the fit was awkward. The work rhythms were different, the customers were different, and the management challenge was bigger than either side wanted to admit. Over the next decade, McDermott shrank dramatically—down 57 percent between 1979 and 1988. And much of that downsizing hit B&W. Plants were closed. Facilities were sold. The supposed diversification play started to look less like a marriage and more like triage.

And yet, here’s the twist: inside the conglomerate, B&W often ended up being the healthier business.

Even as McDermott struggled through the 1980s, B&W—selling design, construction, and maintenance services for steam-generating equipment—kept producing profits. It didn’t post a losing year after the sale. In effect, the boiler company carried the offshore contractor for much of the decade.

Then a different kind of crisis arrived. Not technical. Not operational. Historical.

Like countless industrial manufacturers of its era, B&W had used asbestos insulation extensively in boilers and related equipment. As the medical reality of asbestos exposure became unavoidable in the 1980s and 1990s, lawsuits piled up across American industry—and B&W was right in the blast radius. By February 2000, B&W had 45,000 asbestos claims pending. McDermott had bought the company in 1978 and, since 1982, had spent $1.6 billion to settle more than 340,000 claims.

On February 22, 2000, B&W filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, driven in large part by the scale of asbestos-related personal injury claims. The allegations spanned the full spectrum of asbestos disease: asbestosis, lung cancer, and pleural and peritoneal mesothelioma. Executives pointed to a surge in the damages sought by plaintiffs’ attorneys as the immediate pressure point—but the deeper cause was structural: the bill for yesterday’s industrial materials was finally coming due.

This bankruptcy had almost nothing in common with Three Mile Island. TMI was a crisis of technology, communication, and public trust—an event that froze an industry. Asbestos was a crisis of law and finance: a legacy liability that had little to do with B&W’s current engineering work, but still threatened to swallow the entire enterprise.

When B&W emerged from bankruptcy in 2006, the company tried to stitch itself back together inside McDermott’s orbit. On November 26, 2007, B&W and BWX Technologies—both McDermott subsidiaries—merged to form The Babcock & Wilcox Companies, led by President John Fees.

The McDermott era left B&W with a hard-earned education. Conglomerate diversification didn’t automatically create stability. Divided attention was its own kind of risk. Underinvestment in core strengths could quietly compound over years. And legacy liabilities—totally disconnected from today’s strategy—could still dictate tomorrow’s fate.

Those lessons would matter. Because the next chapter would test them under even harsher conditions.

V. The Great Unraveling: Spin-offs, Bankruptcy & Restructuring (2010-2016)

By 2010, McDermott International had a problem that had nothing to do with boilers, welds, or megawatts. McDermott had moved its incorporation to Panama—an “inversion”—and the U.S. government changed the rules: inverted companies were barred from certain federal contracts. That was an existential issue for B&W’s government-facing nuclear work, where U.S. contracts weren’t a nice-to-have; they were a pillar.

So McDermott did the only clean fix it had. It spun B&W out.

In its own words, McDermott “completed the spin-off of its power generation systems and government operations segments” by distributing shares of The Babcock & Wilcox Company to McDermott shareholders. On August 2, 2010, B&W started trading on the NYSE under the ticker BWC.

It looked like a return to independence: its own management team, its own strategy, its own destiny.

But the independence came packaged with a balance-sheet burden that would turn vicious as the market turned. The pitch to investors was simple and familiar: diversification. Fossil power equipment and services, plus nuclear work, plus renewables—combined into a modern energy technology company. The problem was that diversification only works if at least one of those pillars is growing fast enough to carry the others. B&W’s biggest pillar was about to crack.

While the spin happened, B&W was also reaching for a moonshot.

On June 10, 2009, it unveiled B&W Modular Nuclear Energy, LLC (B&W MNE) and, with it, the mPower reactor: a small, modular nuclear plant designed to be built in a factory, shipped by rail, and installed with a below-ground containment structure. The design was a 125-megawatt, passively safe Advanced Light Water Reactor—Generation III, built around the promise that nuclear didn’t have to mean gigantic, bespoke projects that took a decade and a fortune.

This wasn’t a side project. mPower was B&W trying to leapfrog the post–Three Mile Island stagnation and re-enter the future of nuclear on its own terms.

Momentum followed. In November 2012, mPower won a U.S. Department of Energy funding competition for new small modular reactor designs. In February 2013, B&W announced a deal with the Tennessee Valley Authority to apply for permits to build an mPower SMR at TVA’s Clinch River site in Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

The support was meaningful—tens of millions initially, part of a larger multi-year package with the possibility of more. But funding competitions don’t equal customers, and grants don’t equal a business model.

By early 2014, the cracks were visible. B&W told the market it was struggling to attract investors for the mPower venture with Bechtel. On an earnings call in February, executives pointed to the headwinds: sluggish electricity-demand growth, cheap domestic natural gas, and an uncomfortable truth for a U.S.-based SMR project—the market for early SMRs was increasingly seen as international.

In April 2014, B&W announced it was scaling back investment in the program, expecting to spend up to $15 million annually. The company said it plainly: without additional investors or customer EPC contracts to finance deployment, development would slow.

mPower didn’t die overnight. It lingered—then collapsed. In March 2017, Bechtel withdrew from the joint venture, citing the same core issue: no utility willing to host the first reactor and no investor ready to fund it. The project was terminated, and B&W paid Bechtel a $30 million settlement. Altogether, the joint venture partners spent more than $375 million, on top of the DOE’s $111 million contribution.

While mPower was burning cash and hope, the core business—coal—was sliding into a cliff.

Environmental regulations tightened. Hydraulic fracturing flooded the market with cheap natural gas. Renewables kept getting more competitive. And utilities, reading the same writing on the wall, began to retire coal plants and cancel new ones. B&W was heavily exposed to coal-fired boiler services and new builds, and there’s no gentle way to put this: it was standing in the blast radius.

Then came the second spin.

On June 30, 2015, B&W completed a separation from BWX Technologies, the entity that had been formed years earlier inside McDermott’s orbit. Starting July 1, the companies traded separately. The filing language made the split explicit: the “Power Generation business” would be spun off and renamed Babcock & Wilcox Enterprises, Inc., while the remaining company would become BWX Technologies, Inc.

This was the moment the story’s center of gravity shifted.

The stable nuclear government operations business—the crown jewel, anchored by long-lived Navy work—remained with BWX Technologies (BWXT). The business that became today’s Babcock & Wilcox, trading as BW, was the power generation and environmental operation: more exposed to coal’s decline, more dependent on project execution, and far less protected by the kind of sticky government-backed demand that can carry you through a downturn.

In effect, the most durable part of the company was carved away. What was left kept the harder problems: shrinking end markets, a debt load that no longer matched the risk profile, and the residue of big bets like mPower that had produced headlines—but not revenue.

From 2010 to 2015, each step could be defended on its own. The first spin-off solved a government-contracting constraint. The second created a clean separation between nuclear government work and the rest. But stacked together, they created something far more dangerous: a smaller, weaker company shouldering the most cyclicality and the least stability, right as its biggest market went into free fall.

And that’s how B&W entered the crisis years—not with one catastrophic decision, but with a sequence of “reasonable” restructurings that, in combination, set the stage for the collapse.

VI. The New B&W: Rebuilding & Repositioning (2016-2021)

When B&W Enterprises emerged on the other side of the 2015 separation, there was no sugarcoating the situation. The stable, government-anchored nuclear business had stayed with BWXT. What B&W had left was a power and environmental company tied to shrinking coal markets, weighed down by a stressed balance sheet, and still carrying the aftertaste of a once-promising nuclear moonshot that was now effectively over.

So it needed something more than a cost-cutting plan. It needed a new identity—and a strategy that could actually survive the transition it was living through.

On September 24, 2018, Babcock & Wilcox announced it would move its corporate headquarters from Charlotte to Akron, Ohio, into space formerly occupied by the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company before Goodyear relocated nearby. Akron, the old rubber capital, has spent decades trying to reinvent itself amid Rust Belt decline. For B&W, the symbolism was almost too perfect: a legacy industrial name relocating into the shell of another legacy industrial giant, both searching for a modern second life.

The turnaround fell to Kenneth Young. His playbook centered on three moves: dial back the company’s exposure to volatile international construction projects, lean harder into higher-margin parts and services tied to the installed base, and keep placing measured bets on environmental and “cleaner” energy technologies that might become the next engine of growth.

Operationally, the company organized itself into three segments: Babcock & Wilcox Renewable, Babcock & Wilcox Environmental, and Babcock & Wilcox Thermal. Renewable included technologies like waste-to-energy, solar construction and installation, biomass energy systems, and black liquor systems for the pulp and paper industry—tools meant to turn waste streams into power and reduce reliance on fossil fuels. Environmental focused on emissions control and related technologies sold into utility and industrial steam generation markets, including waste-to-energy and biomass applications. Thermal remained the legacy heart: boilers, steam generation equipment, and the services that keep them running.

And yes—the irony was obvious. B&W, which had helped build so much of the coal-powered industrial world, was now selling the equipment designed to scrub and control the emissions from that same world. In a transition, there’s money on both sides: building the system, then retrofitting it as the rules change.

The results were uneven. The parts-and-services business did what parts-and-services businesses are supposed to do: it was steadier and generally higher margin, because the installed base still needed attention. But the company couldn’t fully shake the gravity of big, complex projects. International construction work continued to generate losses and write-downs, draining cash and consuming management bandwidth—the exact opposite of what a fragile turnaround needed.

Then COVID hit, and the timing couldn’t have been worse. Disruptions rippled through supply chains, job sites, and labor markets. Input costs rose, timelines stretched, and projects got harder to execute profitably. The pressure showed up in tighter margins and higher liquidity needs as the world moved through 2020 and into the following years.

By 2021, B&W had taken real steps forward, but it still didn’t feel safe. The stock caught a temporary lift from market enthusiasm around clean energy and nuclear-adjacent narratives, but the underlying question didn’t change: could B&W generate enough cash from legacy markets that were in long-term decline to fund its transition into whatever came next?

VII. The Nuclear Renaissance & B&W's Third Act (2022-Present)

By late December 2025, Babcock & Wilcox was staring at a kind of inflection point it hadn’t seen in years—one that, even in 2023, would’ve sounded improbable.

The spark wasn’t a new EPA rule or a utility buildout. It was artificial intelligence.

In 2024, data centers accounted for about 4% of total U.S. electricity use, and demand was expected to more than double by 2030. Training and running AI models doesn’t just consume electricity; it demands electricity that doesn’t blink. These facilities can’t simply “wait for the wind” or “catch up when the sun comes back.” They need steady, 24/7 baseload power.

The fuel mix reflected that reality. As of 2024, natural gas supplied more than 40% of U.S. data center electricity, according to the International Energy Agency. Renewables like wind and solar contributed about 24%, while nuclear and coal supplied roughly 20% and 15%, respectively. And the expectation was that natural gas would remain the largest contributor through 2030.

Suddenly, B&W’s old strength—steam generation hardware and the know-how to deliver reliable power—looked relevant again.

Babcock & Wilcox Enterprises, Inc. said it planned to lean on its “reliable, readily available and proven natural gas technologies” to meet the growing power needs of AI data centers, pointing to a pipeline of more than $3 billion in potential opportunities. As part of that push, the company announced it had signed a limited notice to proceed with Applied Digital (NASDAQ: APLD) to begin work delivering and installing natural gas technology for an AI data center project. The planned system would provide one gigawatt of power, with full release for an estimated $1.5 billion contract expected in the first quarter of 2026.

“B&W has designed and installed thousands of boilers and has more than 400 gigawatts of installed generating capacity at utility and industrial plants around the world,” said Kenneth Young, B&W Chairman and Chief Executive Officer. “Our solutions for AI Data Centers are proven technologies that utilize natural gas efficiently while providing reliable, redundant and readily available power faster than combined-cycle or simple-cycle plants.”

At the same time, B&W kept pushing its newer bet: BrightLoop, its hydrogen and carbon-capture technology. The company said it continued moving forward on its BrightLoop project in Massillon, Ohio, targeting hydrogen production by early 2026. It also announced $10 million in funding for development of a BrightLoop hydrogen production and carbon capture facility in Mason County, West Virginia. Management framed the ambition clearly: deploying BrightLoop at commercial scale and aiming for targeted bookings of approximately $1 billion by 2028.

Under the hood, BrightLoop is a chemical looping process. An “oxygen carrier” particle cycles through oxidation and reduction: feedstock reacts with those particles in a fuel reactor, producing reaction products that are predominantly CO2 while reducing the particles. Those reduced particles then move to a hydrogen reactor, where they react with steam—partially re-oxidizing the particles and generating a stream of hydrogen. In other words, the hydrogen comes from the steam in that reaction, rather than being separated out of the original feedstock mix.

But the most dramatic shift in 2025 was financial. The company positioned the year as a turning point in its debt situation, citing asset sales, debt reduction, and improving cash flows as steps that eased prior going-concern pressure. “Recently, we completed the previously announced sale of Diamond Power International for gross proceeds of $177 million, which further improves our balance sheet and reinforces the value of our underlying assets as we re-capitalize our businesses going forward,” Young said. “The proceeds of the Diamond sale allow us to continue to pay down our existing debt obligations.”

The Diamond Power divestiture brought in $177 million of gross proceeds, which B&W said it would use to reduce debt and support its energy transition efforts, including natural gas conversions and data center-related solutions. The company also described debt restructuring steps that extended maturities to 2030, reduced annual interest costs by $1.1 million, and helped lift second-quarter 2025 adjusted EBITDA from continuing operations to $15.1 million.

It went a step further and introduced a full-year 2026 adjusted EBITDA target range of $70 million to $85 million from the core business—roughly 80% year-over-year growth—explicitly excluding any contribution from the newly announced AI data center project.

That optimism reads very differently when you remember what the company itself said not long before. In its reporting, B&W noted that as of December 31, 2024 it had $193 million in senior notes maturing in February 2026—inside the 12-month window after the financial statements were issued. “As a result of the uncertainty regarding our demonstrated ability to repay the current debt, these conditions raise substantial doubt about the Company’s ability to continue as a going concern.”

By September 30, 2025, the company reported total debt of $416.4 million and cash, cash equivalents, and restricted cash of $201.1 million. It paid down $70 million of the February 2026 bonds on October 2, 2025, and said it expected the remaining February 2026 bonds to be paid down in full in December 2025.

B&W also announced a strategic partnership with the private equity fund Denham Capital to pursue coal-to-natural-gas conversions aimed at supplying AI data centers across North America and Europe.

And the opportunity set, at least on paper, swelled fast. “We are seeing strong global demand for our diverse portfolio of technologies and as a result of recent data center opportunities, our global pipeline has increased to over $10.0 billion. We continue to make progress on converting this pipeline of identified project opportunities into bookings.”

VIII. Strategic Framework Analysis

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: LOW to MODERATE

In B&W’s world, “new competitor” usually doesn’t mean a couple of smart engineers and a pitch deck. Designing and building steam generation equipment—especially for nuclear or other high-pressure, high-consequence applications—demands deep technical know-how, specialized manufacturing, and years of credibility. Regulation reinforces the moat: nuclear-grade work requires extensive certifications, documentation, and quality systems that can’t be spun up overnight.

But the threat isn’t zero. In environmental equipment, Chinese manufacturers have shown they can enter and compete hard on price. And in small modular reactors, the competitive set looks different: well-funded ventures like NuScale (even if now struggling) and TerraPower (backed by Bill Gates) can become real rivals if SMRs ever reach sustained commercial deployment.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW to MODERATE

B&W doesn’t buy generic inputs. It needs specialized alloys, catalysts, and precision components—materials where the supplier universe is narrower and the qualification bar is higher. Still, B&W’s long-standing relationships and scale give it some negotiating leverage.

COVID-era supply chain disruption exposed weak points across the industry, and B&W wasn’t immune. But it also wasn’t uniquely disadvantaged; everyone building complex industrial equipment lived through the same delays, shortages, and price pressure.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: HIGH

This is the part of the industry that’s least romantic and most punishing. B&W sells to utilities, industrial operators, and government agencies—buyers that are sophisticated, price-sensitive, and perfectly willing to run a long procurement process to squeeze terms. Government work, particularly Navy nuclear, is stable but comes with strict requirements and tight economics. Utility consolidation only strengthens the buyer’s hand, as large operators can dictate pricing and conditions.

The one counterweight is the installed base. If your plant was built around B&W equipment, you don’t casually swap out the OEM for parts, service, and specialized support. That switching-cost dynamic is what has kept B&W alive through multiple downturns: less a growth engine than an annuity that buys time.

Threat of Substitutes: HIGH and ACCELERATING

The long-term substitution story is clear. Wind and solar keep getting cheaper, batteries keep improving, and policy support—especially incentives from the Inflation Reduction Act—keeps pushing the grid away from coal and, eventually, from other fossil generation too. Natural gas has already taken a huge bite out of coal’s role in U.S. power.

But here’s the twist that explains why B&W is suddenly back in the conversation: AI and data centers have injected new urgency into the need for always-on power. These loads don’t flex easily, and renewables alone can’t guarantee 24/7 supply. Solar doesn’t run at night. Wind doesn’t show up on command. For certain customers, that reality slows substitution and, in pockets, temporarily reverses it.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

Rivalry depends on where you look. Environmental equipment is crowded and often price-driven. Nuclear services are more concentrated, with a small set of players—B&W and competitors like BWXT, Westinghouse, and Framatome—tied to specific reactor fleets and customer relationships. And in the emerging race to power AI infrastructure, B&W is up against much larger, better-capitalized industrial giants like GE Vernova and Siemens Energy.

Overall Industry Attractiveness: MODERATE with Pockets of Value

The core fossil equipment market is mature and in structural decline. But there are pockets where value still concentrates: retrofits, emissions controls, services tied to existing plants, and now, potentially, new demand for firm power driven by data centers. The opportunity is real—but the clock is running. B&W has to capture these pockets before retirements and substitution shrink the base further.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: MODERATE

Scale matters in heavy manufacturing. The more volume you run through engineering and production, the more you can spread fixed costs and keep unit economics competitive. The problem for B&W is that post-bankruptcy and post-divestiture, it’s no longer operating with the same heft. Against integrated players like GE Vernova or Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, B&W is simply smaller.

Network Economics: NONE

There are no network effects here. One customer’s boiler doesn’t become more valuable because another customer bought one too.

Counter-Positioning: WEAK

B&W is trying to define itself as more than legacy thermal—BrightLoop, environmental solutions, cleaner conversions. The question is whether any of that is truly defensible. Established competitors can copy features, and new entrants don’t carry the burden of legacy cost structures or legacy markets. BrightLoop could become a real differentiator if it proves itself at commercial scale, but until then, it’s promise more than power.

Switching Costs: MODERATE to STRONG (varies by segment)

This is the closest thing B&W has to a durable advantage. In nuclear services, switching costs can be extremely high—if you’re running B&W-designed equipment, you need B&W expertise and support. In thermal parts and service, proprietary designs also keep customers sticky.

But in new equipment, switching costs drop sharply. Buyers shop on price, performance, and execution track record. And in recent decades, execution has been where B&W has been most vulnerable.

Branding: WEAK

B&W’s name carries history, but not the kind you can always monetize. Bankruptcy, project disappointments, and the enduring Three Mile Island association weigh on perception. In industrial markets, brand matters far less than reliability, pricing, and proof you can deliver without surprises.

Cornered Resource: MODERATE

B&W’s engineering bench—nuclear expertise, high-pressure systems knowledge—takes time to replicate. It also has intellectual property in emissions controls and BrightLoop. And the installed base across more than 600 utility sites functions like a quasi-cornered resource: a captive audience for parts and services.

Still, this advantage is fragile. An aging workforce and the pull of better-capitalized competitors can drain the very talent that makes the cornered resource “cornered.”

Process Power: WEAK to MODERATE

The company has decades of manufacturing experience in complex equipment. But process power only becomes a true edge when execution is consistently excellent. B&W’s record—especially on large, complex projects—has been uneven, and it hasn’t built the kind of operational machine that turns competence into a compounding advantage.

Dominant Power: Switching Costs in the Installed Base

If B&W has a moat, it’s here: hundreds of sites running proprietary B&W equipment that need B&W parts, service, and know-how. That installed base produces recurring revenue and creates time—time to refinance, to restructure, to attempt the next bet.

But it’s also a melting moat. As older plants retire and are replaced with non-B&W technology, the lock-in shrinks. The installed base can sustain B&W, but it can’t save B&W forever.

IX. Business Model & Unit Economics

By now, the pattern is pretty clear: B&W survives on what it already installed, and it gets hurt when it tries to swing for the fences with big, bespoke projects. The business is basically three revenue streams with very different risk profiles:

Thermal Equipment and Services (largest segment, ~60%+ of revenue)

This is the modern version of B&W’s original identity: steam generation for utility and industrial customers. It’s a blend of two very different businesses living under one roof.

On one side, you have new equipment and large project work—lower margin, higher risk, and brutally dependent on flawless execution. On the other, you have aftermarket parts and service—recurring, stickier, and generally higher margin. In recent years, management has been explicit about the shift: less large international EPC work, more domestic parts-and-services tied to the installed base.

Environmental Equipment and Retrofit

Here’s the company selling the tools of the transition: pollution-control systems like electrostatic precipitators, scrubbers, and emissions monitoring equipment. The pitch is straightforward—help existing plants comply with changing environmental standards.

This segment can get a tailwind when regulations tighten, and it can get whiplash when the regulatory mood swings the other way. It’s a business where demand is real, but predictability isn’t guaranteed.

Renewable Energy Equipment

This includes waste-to-energy and biomass work, with solar installation now divested. The big theme here has been retreat: B&W pulled back from international renewable projects after they proved unprofitable. It still participates in “renewables,” but with a much sharper filter on what it’s willing to build and where.

The real economic dividing line across all of this isn’t thermal versus environmental versus renewable. It’s Parts & Services versus New Equipment/Projects:

Parts & Services: This is the annuity. Higher margin, recurring, and supported by the switching costs of proprietary equipment. It’s the part of B&W that can keep the lights on while everything else gets reorganized. In the second quarter of 2025, Global Parts & Service revenue rose to $64.8 million, up from $49.3 million in the second quarter of 2024.

New Equipment/Projects: This is where B&W’s margin goes to die. New builds and complex projects tend to carry low single-digit margins even when they go well, and when they go poorly, they can turn into multi-year cash drains through cost overruns and write-downs—especially on large international work.

The Working Capital Trap

The cruel part of big projects isn’t just that they’re risky. It’s that they’re cash-hungry early.

You have to spend upfront—materials, engineering hours, mobilization—while customer billing happens later through milestones that don’t always match the cash leaving the building. If schedules slip or costs spike, the project doesn’t just lose money on paper; it can actively consume liquidity. That’s how you end up with the paradox B&W keeps living: “operational improvement,” but cash still bleeding because yesterday’s bad project decisions take years to unwind.

The Debt Spiral

Layer leverage on top of that working-capital dynamic and you get the classic distressed loop: interest expense eats the cash the business generates, so you sell assets to reduce debt. But selling assets also reduces future earnings power, which makes the remaining debt harder to carry.

B&W’s 2025 debt restructuring helped ease the pressure and partially interrupt that loop, but the underlying reality hasn’t changed. The company is still highly leveraged, and it’s still racing to turn its backlog and pipeline into actual cash before the next wall shows up.

X. Bull vs. Bear Case

The Bull Case: "From the Ashes"

1. AI-Driven Baseload Renaissance

The explosion in data center construction has created a new kind of demand: reliable, 24/7 power, fast. That plays directly to B&W’s modern pitch—natural-gas-based steam and power solutions that can be deployed sooner than many traditional builds.

B&W said it signed a limited notice to proceed with Applied Digital (NASDAQ: APLD) to begin work delivering and installing natural gas technology for an AI data center project. The planned system would provide one gigawatt of power, with full release for the estimated $1.5 billion contract expected in the first quarter of 2026. If the full release comes through—and if this becomes the first of several similar projects—B&W could see growth that finally feels like a real escape velocity moment, not just a turnaround story.

2. BrightLoop Could Be Transformational

Hydrogen is still more promise than infrastructure. But if BrightLoop works at commercial scale, the prize is huge: a pathway to produce hydrogen while generating a concentrated CO2 stream suitable for sequestration. B&W has pointed to state grant support and potential federal programs as validation, and it has set an aggressive goal: targeted bookings of approximately $1 billion by 2028.

In the bull framing, that number isn’t important because it’s a precise forecast. It’s important because it signals management believes BrightLoop can move from “interesting technology” to “sellable product”—and that would give B&W something it hasn’t had in years: a growth vector that isn’t tied to aging coal assets.

3. Debt Crisis Resolved

The 2025 restructuring is the optimistic turning point: maturities extended, interest costs reduced, and the immediate sense of “this company might not make it” eased. Management has argued that a mix of asset sales, debt reduction, and improving cash flow has pushed B&W out of the most dangerous part of the liquidity tunnel—at least for now.

4. Operational Turnaround Gaining Traction

This is the simple, measurable part of the bull case: demand is showing up. B&W reported 2024 bookings of $889.6 million, up 39% versus full-year 2023, and an ending backlog of $540.1 million, up 47% from the end of 2023. If those bookings convert cleanly into profitable execution, it’s evidence that the refocus on the installed base, parts and service, and more selective projects is working.

5. Deeply Undervalued if Survival is Assured

The final bull argument is classic distressed optionality: if B&W survives the balance-sheet stress and executes on the data center and BrightLoop narratives, today’s valuation could end up looking like it priced in failure rather than a rebound.

The Bear Case: "Zombie Company"

1. Execution Risk Remains High

B&W has been burned by big projects before—cost overruns, write-downs, and contracts that looked exciting until they started consuming cash. The AI data center deal is also not final: it’s a limited notice to proceed, with full release expected in Q1 2026. Until that happens, it’s potential revenue, not real revenue. And even if it does happen, “large, complex project” is exactly the category that has historically destroyed value here.

2. BrightLoop is Unproven Technology

mPower is the ghost in the room. The joint venture partners spent more than $375 million on that SMR program, on top of the DOE’s $111 million contribution, and it still never reached commercialization. BrightLoop could be different—but it could also rhyme. The “$1 billion by 2028” figure is a target, not contracted backlog, and in the bear framing it’s more marketing than money until a commercial-scale facility runs and customers sign.

3. Core Business Remains a Melting Ice Cube

Even with AI-driven demand, the long-term direction of travel for coal is still down. Plants keep retiring, and renewables plus storage keep getting cheaper and more capable. Data centers may slow the decline in pockets or extend the life of certain assets, but that’s not the same thing as a structural comeback for fossil-fired power equipment and services.

4. Leverage Remains Extreme

Debt is still the constraint that makes every operating hiccup existential. Even after restructuring, the company remains highly levered, which means one bad project, one demand pause, or one refinancing surprise can put it right back under the same going-concern cloud it has been trying to escape.

5. Better-Capitalized Competitors

Finally, B&W is not the only company that sees the AI power buildout. It’s competing against giants—GE Vernova, Siemens Energy, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries—with stronger balance sheets and more capacity to invest, price aggressively, and absorb risk. In a bidding war for data center power projects, size and capital can matter as much as engineering.

XI. What Would We Have Done Differently?

With the benefit of hindsight, B&W’s story has a handful of moments where the path forked—and where a slightly different decision could have changed the company’s odds of making it through the decade intact.

The 2010 Spin-off from McDermott

The spin solved a real problem: McDermott’s Panama incorporation threatened B&W’s ability to win and keep certain U.S. government contracts. Structurally, the separation made sense.

But B&W came out into public markets carrying too much leverage for what it actually was: a company exposed to a fuel source about to go into structural decline. A cleaner balance sheet at separation—more conservative debt, more liquidity—would have bought the flexibility to absorb the coal collapse instead of being defined by it. The lesson here is brutal and simple: in a spin-off, capital structure matters as much as strategy.

The mPower SMR Program

mPower was the right kind of idea. Small modular reactors are still a credible answer to nuclear’s biggest commercial problem: scale and complexity.

The issue was execution and timing. B&W tried to commercialize a revolutionary nuclear product before the market was ready, and without the level of funding that nuclear development demands. It was an awkward middle ground—too ambitious to do cheaply, but too undercapitalized to finish. When you’re building nuclear technology, “mostly committed” is just another way to say “eventually abandoned.” Either commit fully, with patient capital and a real path to customers, or don’t start.

Exit Coal Earlier and More Decisively

By 2012, the warning lights were flashing. EPA pressure, cheap natural gas, and renewables getting better every year weren’t cyclical headwinds. They were structural.

And yet B&W stayed tied to coal longer than it could afford to, continuing to invest in coal-adjacent capabilities while the addressable market kept shrinking. A faster pivot toward environmental solutions, nuclear services, and cleaner technologies would have protected capital—and, maybe more importantly, protected focus—when the company needed both.

International Project Discipline

The cash destruction from international construction projects wasn’t a one-off. It was a repeating pattern: contracts that looked attractive on paper, then turned into margin erosion, delays, and write-downs.

A more disciplined approach could have taken two forms: either invest early in world-class project execution and risk management, or make the hard choice to walk away from work that didn’t fit the company’s capabilities and balance sheet. The operating principle should have been under-promise and over-deliver—especially for a company that couldn’t afford surprises.

XII. Lessons for Founders & Investors

For Founders and Operators

1. Beware the Slow-Motion Disruption

Coal didn’t collapse overnight. Its decline was visible for decades before it turned into a cliff. The danger for incumbents is that slow declines feel survivable—until the moment they aren’t. When your core market is shrinking structurally, “waiting for clarity” is usually just another way of waiting until the cash, the talent, and the options are gone.

2. Debt is a Double-Edged Sword

Leverage doesn’t just amplify downturns; it narrows your strategy. B&W’s debt load turned every market shock into a crisis and made even sensible pivots harder to fund. In a declining or disrupted industry, a clean balance sheet isn’t conservative—it’s offensive. It buys you time, credibility, and the ability to make long-term bets without betting the company.

3. Technology Transitions Take Longer Than You Think

For forty years, nuclear has been “five years away.” SMRs were supposed to fix nuclear’s cost and complexity problem, but commercial deployment has remained stubbornly out of reach. The lesson isn’t that the technology is fake—it’s that timelines kill. If you bet the company on unproven tech while the core business is deteriorating, you can be right on engineering and still lose on timing.

4. Switching Costs Create Moats But Cannot Save Sinking Ships

B&W’s installed base kept it alive through multiple storms. But a moat isn’t a cure for a market that’s melting out from under you. The play is to harvest the moat for cash and use it to fund the next chapter—not to keep reinvesting in a core business whose long-term demand is shrinking.

For Investors

1. Value Traps are Real

B&W looked “cheap” for years, and shareholders still got punished. Low multiples don’t automatically mean undervaluation; sometimes they’re just the market pricing in survival risk. The real question isn’t “is it cheap?” It’s “what has to go right for this equity to matter?”

2. Inflection Points are Hard to Time

The nuclear comeback narrative, the AI power surge, and the hydrogen economy are all plausible. But in public markets, being early often feels exactly like being wrong. For companies with leverage and execution risk, it can be smarter to wait for proof—contracts that convert, projects that deliver, technology that runs—than to try to buy the bottom of a story.

3. Going Concern Warnings Matter

When the filings say there’s “substantial doubt” about the company’s ability to continue, don’t wave it away as boilerplate. In distressed situations, equity is a thin slice sitting underneath everything else—and it can disappear fast. B&W’s 2024 going-concern language reflected real uncertainty, not just cautious phrasing.

4. Follow the Cash, Not the Story

AI data centers and hydrogen make for great headlines. But the balance sheet and cash flow statement are where the truth lives. A company can’t narrative its way out of a debt hole, and it can’t outrun losses with optimism. If the cash doesn’t show up, the story doesn’t matter.

XIII. Where Do We Go From Here?

Key Signposts to Watch

1. AI Data Center Contract Conversion

Right now, the headline deal—the estimated $1.5 billion Applied Digital project—is only at a “limited notice to proceed,” with full release expected in Q1 2026. If that release happens, and if it becomes the first domino in a broader wave of data center work, it changes the company’s trajectory. If it slips, shrinks, or never converts, it reinforces the harsher read: B&W is still living on potential.

2. BrightLoop Commercial Demonstration

The BrightLoop site in Massillon, Ohio is targeting hydrogen production by early 2026. This is the make-or-break moment for the story B&W is selling about its future. A working, commercial-scale demonstration would validate years of investment and give customers something real to underwrite. If it doesn’t perform—or if funding runs dry before it can prove itself—BrightLoop risks becoming another ambitious bet that never crosses the line from engineering to revenue.

3. Quarterly Cash Flow

EBITDA can tell you a business is improving. Cash flow tells you whether it can survive. B&W has said it expects positive net cash flow in 2025 excluding BrightLoop investment. The key signal is consistency: quarter after quarter where the core business actually generates cash, not just “adjusted” progress.

4. Backlog Composition

The size of backlog matters, but what’s in it matters more. Services versus projects. Domestic versus international. Higher-margin, repeatable service work tied to the installed base is the kind of backlog that stabilizes a turnaround. Low-margin, complex construction—especially far from home—is the kind that can quietly turn into the next write-down.

Three Scenarios for 2027

Scenario A: Bankruptcy 2.0 (20% probability)

The data center contracts don’t materialize beyond early-stage activity. BrightLoop fails to reach commercial performance or runs out of funding. The decline in the core business accelerates. The debt restructuring buys time, but not enough. Equity gets wiped out and creditors end up owning whatever remains.

Scenario B: Zombie Survival (40% probability)

B&W manages to refinance and keep moving, but never breaks into real momentum. The installed base continues to fund the company, slowly shrinking as older plants retire. AI-related work helps at the margin without transforming the business. BrightLoop stays perpetually “next year.” The stock drifts, and the company becomes a case study in endurance rather than reinvention.

Scenario C: Renaissance (40% probability)

The data center wave turns into a real growth engine, and B&W proves it can execute profitably at scale. BrightLoop reaches commercial viability and starts converting interest into bookings. Debt falls into a range the business can carry without turning every setback into an existential threat. In this scenario, B&W becomes something it hasn’t been in decades: a credible clean-energy infrastructure play, and the market re-rates it accordingly.

The Human Story

Underneath the contracts, the debt, and the technology bets are thousands of employees—many from multi-generational B&W families—whose lives have been intertwined with this company for decades. The headquarters in Akron sits in a region that knows, firsthand, what deindustrialization feels like. When B&W stumbles, it doesn’t just hit a stock chart; it hits a community.

And the toughest challenge may be the quietest one: talent. The engineering expertise that built B&W’s reputation is aging, and recruiting the next generation is harder when the narrative is uncertainty. Keeping institutional knowledge alive while attracting new engineers into a legacy industrial company may be one of the most consequential fights B&W is in—and one of the least visible from the outside.

Final Reflection

Babcock & Wilcox compresses 158 years of American industrial history into one company: innovation, dominance, hubris, disruption, and desperation. The same name that powered Edison’s early electrical systems, Roosevelt’s navy, and the arsenal of democracy is now trying to keep itself powered through a very different kind of energy transition.

If there’s a lesson here, it’s that moats age. Installed base and switching costs can buy you time, but they don’t stop the world from changing. Financial engineering can delay consequences, but it can’t replace execution. And legacy liabilities—whether asbestos, Three Mile Island’s shadow, or an overleveraged balance sheet—can follow a company for decades.

B&W is back at an existential decision point. The AI power buildout and the hydrogen economy offer real pathways to renewal. But they also demand something B&W has rarely had in abundance over the last decade: clean execution and enough runway to let big bets mature.

B&W may have a strategy. The open question is whether it has the time.

Key Metrics to Track Going Forward

If you’re trying to underwrite Babcock & Wilcox as more than a good story, you want a short list of signals that can’t be massaged. Three matter most:

1. Quarterly Cash Flow from Operations (excluding BrightLoop)

This is the lie detector. EBITDA can improve while cash quietly leaks out through working capital, project overruns, and interest. If the core business can produce steady, positive operating cash flow quarter after quarter (even while BrightLoop remains an investment), that’s real evidence the turnaround is working. If it can’t, then the company is still living on time, not on fundamentals.

2. Backlog Conversion Rate and Composition

Backlog looks comforting until it doesn’t turn into cash. Watch how reliably it converts into revenue each quarter, and pay close attention to what the backlog is made of. A backlog weighted toward parts and services—repeatable work tied to the installed base—usually means better margins and fewer surprises. A backlog dominated by large project work is where B&W’s past has gone sideways.

3. Debt-to-EBITDA Ratio Trajectory

This is the constraint that turns normal business risk into existential risk. At roughly 11x post-divestiture, leverage still has to come down for B&W to feel truly stable. The direction matters more than the precision: quarter by quarter, is the company de-levering through real earnings and cash generation, or just reshuffling the problem?

The next year is where the story stops being theoretical. Either B&W turns backlog into cash, brings leverage down, and earns the right to pursue its next bets—or it becomes another reminder that in heavy industry, a compelling narrative is never a substitute for runway.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music