Popular, Inc.: The Story of Puerto Rico's Banking Empire

Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture this: it’s the morning after Hurricane Maria tears across Puerto Rico in September 2017. The island is dark. Power is gone, water is unreliable, cell service is dead, roads are blocked, and the grid has effectively collapsed. In the middle of that chaos, people need all the basics—food, shelter, medicine—but there’s one other thing that suddenly becomes priceless: cash.

And somehow, amid the wreckage, branches of Banco Popular flicker back to life on backup generators. Employees show up any way they can—on foot, by boat, however—then start doing the unglamorous, vital work of keeping money moving. Paying out currency to stunned customers through whatever improvised process will work, because in a crisis like this, the bank isn’t just a bank. It’s infrastructure.

That’s the company at the center of our story.

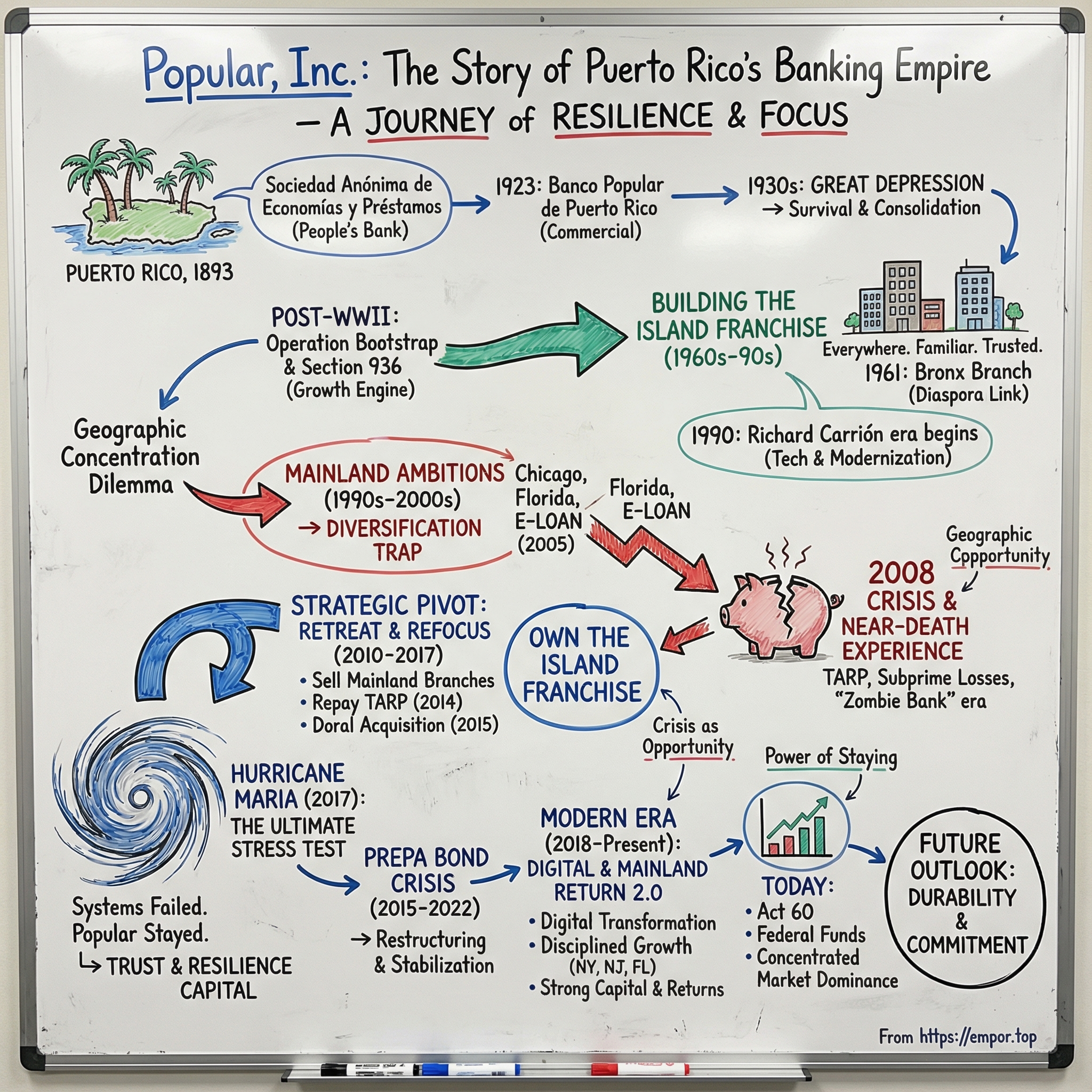

Popular, Inc. is Puerto Rico’s leading financial institution, with more than $70 billion in assets and operations spanning the island, the mainland United States, and the Virgin Islands. It’s also one of the fifty largest bank holding companies in the country. But this isn’t a typical “regional bank grows steadily and compounds quietly” narrative. This is the story of how a small savings institution founded in 1893—back when Puerto Rico was still a Spanish colony—became the financial backbone of a U.S. territory, survived a decade-long economic depression, lived through catastrophic natural disasters, navigated a government debt crisis, and still managed to emerge as one of the stronger performers in American banking.

Popular’s origin is as grounded as it gets. In 1893, Rafael Carrión Pacheco and a group of Puerto Rican entrepreneurs created a savings-and-loan cooperative called Sociedad Anónima de Economías y Préstamos. It would later become Banco Popular de Puerto Rico, built to serve working people at a time when formal banking largely catered to the wealthy.

So here’s the question that animates everything that follows: how did a Puerto Rican bank survive the island’s lost decade, hurricane devastation, and a historic public-debt collapse—and still end up among the best-performing regional banks in America?

The answer isn’t a single heroic moment. It’s a mix of smart strategy and hard-earned operational discipline, plus some painful detours—especially on the mainland—and an almost stubborn commitment to a market that plenty of others would have written off.

In this story, we’ll follow Popular’s arc from island institution to Caribbean powerhouse, through an ambitious U.S. expansion that didn’t work, and back to a refocused core that proved far more resilient than anyone expected. Along the way, keep an eye on three themes: resilience born of necessity, the double-edged sword of geographic concentration, and the power—sometimes underrated, sometimes dangerous—of staying when others leave.

Founding Context: Puerto Rico's Unique Banking Ecosystem

To understand Popular, you first have to understand Puerto Rico’s odd place in the American financial system. It’s part of the United States, but not a state. It uses the U.S. dollar, yet lives under its own tax and economic realities. Its banks can be FDIC-insured and regulated inside the U.S. framework, while operating in an island economy that behaves nothing like Florida or New Jersey.

Popular’s roots go back to 1893, when Puerto Rico was still under Spanish rule. That year, fifty-two stockholders put up the capital to launch what was essentially a savings institution for ordinary people: the Sociedad Anónima de Economías y Préstamos, created to help working-class Puerto Ricans save and borrow in a world where formal finance mostly ignored them.

That context matters. Under Spanish administration, credit for everyday Puerto Ricans was scarce. Foreign banks catered to wealthy merchants and sugar interests. So local entrepreneurs—including members of the Carrión family, who would guide the institution for generations—set out to build something different: a true “people’s bank,” meant to widen access to basic financial services.

Then history hit fast.

In 1898, the United States invaded Puerto Rico during the Spanish–American War, and the island was ceded to the U.S. under the Treaty of Paris, ratified on December 10, 1898. The American takeover kicked off an aggressive “Americanization” of Puerto Rico’s economy and governance, and banking was no exception. Control over key financial institutions shifted, and the island’s economic rules were rewritten almost overnight.

For the young Popular, the timing was brutal. Deposits fell by roughly two-thirds. A hurricane devastated the island in 1899. And in 1900, Congress reset the currency conversion, declaring the Puerto Rican peso worth only 60 cents instead of a dollar—shrinking the bank’s capital down to about $18,000. For a fragile, community-focused institution, it was the kind of one-two-three punch that ends most stories.

But this one didn’t end.

Out of those early shocks, Popular re-emerged in a more durable form. In 1923, Carrión and his older brother, along with former members of the original Sociedad Anónima, organized Banco Popular de Puerto Rico as a commercial bank rather than a savings bank. Carrión became Executive Vice President. By 1927, he was the majority stockholder, president, and CEO.

Rafael Carrión Sr. turned out to be exactly the kind of leader a bank like this needed: practical, aggressive, and deeply attuned to what everyday customers lacked. In 1934, Popular opened its first physical branch. In its first year, it made personal loans without requiring collateral—a radical move in a banking world built around who already had assets. The strategy worked. It wasn’t just a bank with a nice name; it became popular in the literal sense. By 1954, it had grown to 20 branches across the island.

Then came the Great Depression. Banks failed everywhere, and Puerto Rico was no exception. Popular survived. More than that, it consolidated. In 1930, it purchased the island’s oldest and most respected bank, Banco Comercial de Puerto Rico. By 1937, with deposits totaling $8.82 million, Banco Popular was the largest bank in Puerto Rico.

After World War II, Puerto Rico launched Operation Bootstrap—an industrialization push that reshaped the island from an agricultural economy into a manufacturing hub. And decades later, Section 936, enacted in 1976 as part of the U.S. tax code, added rocket fuel. Designed to encourage investment in Puerto Rico and other U.S. possessions, it made the island especially attractive to manufacturers, including pharmaceutical and electronics companies. Those incentives didn’t just change Puerto Rico’s economy; they helped define the financial ecosystem Popular would dominate for years.

The founding context reveals something essential about Popular: it wasn’t born as a clever financial play. It was built to serve people who had been left out. That “serve the community first” origin became part of the bank’s operating DNA—and it would matter enormously when Puerto Rico’s future stopped being stable and started being a stress test.

Building the Island Franchise (1960s–1990s)

By the 1960s, Puerto Rico was in the middle of a full-on economic makeover. Tax incentives pulled in mainland manufacturers, pharmaceutical plants went up, and the island’s economy expanded at a pace that surprised almost everyone. Banco Popular did what it had always done best: it made itself unavoidable. The strategy was simple, almost stubborn in its consistency—be everywhere Puerto Ricans were, and make banking feel familiar.

That didn’t just mean saturating the island with branches. In 1961, Banco Popular opened its first mainland U.S. branch in the Bronx. Three years later, it opened another in Manhattan’s Rockefeller Center. The Bronx location wasn’t a random beachhead; it was a direct response to the Puerto Rican diaspora. If people were leaving the island to build lives in New York, Popular wanted to be the bank they could take with them—one that spoke Spanish, understood their needs, and didn’t treat them like a niche.

That same period, Popular also began to stretch beyond U.S. borders. In 1964, it established its first foreign branch in the Dominican Republic. In 1965, Rafael Carrión Jr. succeeded his father as president, and the bank relocated its headquarters to a newly built home in Hato Rey, the growing financial district outside San Juan. It was a symbolic move: Popular wasn’t just surviving anymore. It was building permanence.

What Popular really had—what mainland banks struggled to replicate—was cultural and local fluency. Big U.S. banks could look at Puerto Rico and see a small, distant market. Popular saw the internal logic of the island economy: the seasonality of cash flows, the importance of remittances, and how much lending depended on relationships and reputation. Popular spoke the language, literally and figuratively. It showed up in towns where a Chase or Citibank would never bother planting a flag.

And as the Hispanic population on the mainland grew, Popular leaned harder into serving that community there too—especially in the 1990s, when it significantly expanded its mainland presence.

Then consolidation hit, and it reshaped Puerto Rican banking. In 1989, Banco Popular bought BanPonce Corporation in a cash-and-stock deal valued between $278 million and $324 million. BanPonce—founded in 1971 as Banco de Ponce—was the fourth-largest bank in Puerto Rico, with dozens of branches on the island and a meaningful foothold in New York. The branches took the Banco Popular name, but the corporate structure temporarily carried the BanPonce label. That lasted until 1997, when the parent company was renamed Popular, Inc.

In 1990, Popular merged with Banco de Ponce, strengthening its grip on the island. In 1991, it deepened its position in New York by purchasing the failed Bronx-based New York Capital Bank—another step toward becoming the default choice for Hispanic customers who wanted a bank that felt like home.

This era also marked the rise of the next Carrión. In 1990, Richard Carrión—Rafael Sr.’s grandson and Rafael Jr.’s son—was named Chairman and CEO of the company, the bank, and its North American operations. He brought a different kind of ambition: MIT training, global confidence, and a strong belief that technology could widen Popular’s moat.

Under Richard’s leadership, Popular pushed banking modernization across Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and parts of Latin America. He brought the first network of ATMs to Puerto Rico and other Latin American markets, drove the shift from paper to electronic transactions, and built what became the Caribbean’s largest data processing center—turning IT from a back-office function into a strategic weapon.

By the 1990s, Popular had pulled off something rare: dominance in a geographically protected market. With around 40% of Puerto Rico’s deposits, it operated in what was effectively an oligopoly alongside FirstBank and Oriental. Competition was more rational than cutthroat. Customer relationships were sticky. And the economics were attractive.

But even as the franchise looked stronger than ever, the foundation under Puerto Rico was starting to crack. In 1996, Congress voted to phase out Section 936, arguing the tax break was too costly and benefited too few companies. The phase-out finished in 2006. It was the beginning of a long unwinding for the island’s economic engine—and it meant Popular’s greatest strength, its deep entanglement with Puerto Rico, was also its biggest exposure.

The takeaway from this era is straightforward: Popular built an extraordinary franchise through proximity, trust, and operational execution. It also tied its fate to Puerto Rico’s fortunes—whether those fortunes were rising or falling.

Mainland Ambitions: The U.S. Expansion Era (1990s–2000s)

By the late 1990s, the strategic logic felt almost impossible to argue with. Section 936 was being phased out. Puerto Rico’s population was aging, and more people were leaving for the mainland. If Popular’s greatest risk was concentration on one island economy, then the obvious fix was diversification—take what the bank was best at, serving Hispanic communities with cultural fluency, and scale it in the U.S.

Popular had already been laying groundwork. It bought Chicago’s Pioneer Bank in 1993, then added two more banks, building out to 13 locations in the city. In 1997, it even made Chicago its official U.S. headquarters—a signal that this wasn’t a side project. It was a second home base.

Florida came next. Popular entered the state by acquiring Seminole National Bank in Sanford, and by the spring of 1999 it had eight branches there. That same year, Banco Popular launched a nationwide mortgage-loan program aimed at the Hispanic market—another attempt to turn a cultural edge into a growth engine.

For a while, the story looked like it was working. By the end of 2000, Popular, Inc. ranked as the 35th largest bank holding company in the United States, with $28.1 billion in consolidated assets and $14.8 billion in deposits. Puerto Rico was still the core, but the mainland was starting to look real.

Then came the move that was supposed to make Popular feel truly modern: E-LOAN. In 2005, Popular acquired the online consumer lender for about $300 million, paying $4.25 per share in cash. The pitch was straightforward—E-LOAN would get access to Popular’s balance sheet, and Popular would get a national digital platform that could originate loans at scale, far beyond the reach of branches.

By the mid-2000s, Popular’s mainland footprint was massive. Banco Popular North America ran more than 135 branches across California, Texas, Illinois, New York, New Jersey, and Florida, plus roughly 130 financial services stores under the Popular Cash Express name. Its U.S. finance subsidiary, Popular Financial Holdings, operated nearly 200 retail lending locations for mortgages and personal loans, alongside a wholesale broker network, warehouse lending, servicing, and an asset acquisitions unit. At its peak, it looked like Popular had pulled off the rare trick: an island bank turning into a nationwide platform.

But underneath the growth, there was a contradiction that never went away.

Popular could borrow cheaply in Puerto Rico, where deposits were stable and abundant. Then it turned around and pushed that funding into aggressive mainland lending—often in riskier corners like subprime mortgages and construction-related credit. The mainland operations grew fast, but they didn’t match the profitability or stability of the Puerto Rico franchise. Popular was diversifying geography, yes—but it was also changing the bank’s risk profile.

And back on the island, the thing Popular was running from was accelerating. In 1996, President Clinton signed the legislation that phased out Section 936 over ten years, with full repeal at the start of 2006. Once that tax advantage disappeared, Puerto Rican subsidiaries of U.S. companies faced the same worldwide corporate income tax treatment as other foreign subsidiaries. The incentive that had anchored so much investment began to unwind.

Not coincidentally, 2006 marked the start of a deep recession in Puerto Rico that persisted for years. With Section 936 gone, the island’s economic structure—high taxes on domestic corporations paired with unusually favorable treatment for certain U.S. subsidiaries—lost its center of gravity. Foreign investment began to flee, and the slow-motion downturn Popular feared started to show up in the real economy.

For investors, this era reads like a warning shot. The motivation was rational: diversify away from a weakening home market. But execution is where strategies live or die. Popular expanded quickly, spread itself across too many markets, and leaned into loan products—especially subprime—that it didn’t fully understand.

The 2008 crisis wouldn’t just test that bet. It would nearly break the company.

The 2008 Crisis & Near-Death Experience

The Great Financial Crisis hit Puerto Rico harder than almost anywhere else in America. The island was already wobbling from the slow unwind of Section 936. Then the global credit machine seized up. What had been a recession turned into something closer to a prolonged economic free fall.

For Popular, this wasn’t a bad year. It was an existence check.

On the mainland, the growth engine that was supposed to diversify risk did the opposite. Losses piled up in construction and commercial real estate, and the bank’s exposure to subprime-related lending suddenly mattered a lot. Back in Puerto Rico, the economy contracted sharply and borrowers across portfolios started to break. Non-performing loans surged into the double digits, and capital ratios came under pressure.

Popular survived, but only by entering what amounted to emergency mode: restructuring, shedding distractions, and refocusing on what it could still control.

The most visible symbol of that survival was TARP. Popular took a $935 million infusion under the U.S. Treasury’s Capital Purchase Program—money that was both a lifeline and a public admission that the bank couldn’t ride this out alone. Years later, after getting regulatory approval from the Federal Reserve, Popular repaid the government. The Treasury announced taxpayers received $946 million in that repayment, and that overall they recovered $1.22 billion of principal and interest from the original $935 million investment.

In the meantime, regulators tightened the leash. Popular operated under restrictions and consent orders, with balance-sheet decisions scrutinized and flexibility limited. For several years, the bank lived in that uncomfortable in-between state industry watchers call a “zombie bank”: alive, functioning, even profitable at times—but too weak to take real swings.

Some of the clearest evidence of what went wrong showed up in E-LOAN. In October 2008, Popular said E-LOAN would stop operating as a direct mortgage lender in 2009. It would keep offering certificates of deposit and savings accounts, while operational and administrative functions were moved into other Popular subsidiaries. The acquisition that had been pitched as a modern, national digital platform—bought just a few years earlier for about $300 million—had turned into a millstone as the subprime crisis vaporized its core business.

And the broader cleanup had already started. In 2007, Banco Popular North America sold five of its six Texas branches to Prosperity Bank. That same year, Popular bought Citibank’s retail business in Puerto Rico, including nine branches, along with the Puerto Rico operations of Smith Barney, a Citibank subsidiary. In 2008, Popular agreed to sell certain assets of Equity One—the mainland consumer finance operations inside Popular Financial Holdings—to American General Finance, part of AIG.

The crisis years tested everything: underwriting, funding, leadership, morale. Management turmoil came with the financial stress. But Popular didn’t collapse. It endured, then began the slow, grinding work of rebuilding.

The lesson for long-term investors is uncomfortable but useful. The mainland expansion wasn’t just unlucky timing—it exposed gaps in risk management and pulled Popular into businesses that didn’t behave like its home franchise. And yet, the Puerto Rico core—despite the island’s deepening downturn—kept producing enough earnings power to keep the institution standing. In a small market, being essential cuts both ways. Popular was Puerto Rico’s financial infrastructure, and in 2008 that meant regulators had every incentive to make sure it survived.

The Strategic Pivot: Retreat & Refocus (2010–2017)

After the crisis, Popular made what might be the most counterintuitive decision in its entire history: it started backing away from the mainland and leaning harder into Puerto Rico.

To most outsiders, it looked like madness. Why would a bank that nearly got taken out by a collapsing economy choose to concentrate itself even more in that same market?

But Popular’s bet wasn’t “Puerto Rico is about to boom.” It was sharper than that: even in a terrible economy, being the dominant institution can be a better business than being a mid-tier player in hyper-competitive mainland markets. Own the island, wait for recovery, and make yourself unavoidable.

The retreat started becoming visible in 2014. Popular Community Bank sold many of its mainland branches in Central Florida, Illinois, and Southern California—moves aimed at cutting costs and building reserves as the aftershocks of foreclosures and Puerto Rico’s recession kept rippling through the system.

Then came the milestone that signaled Popular was finally crawling out of the government’s shadow. On July 2, 2014, the Corporation completed repayment of its TARP funds to the U.S. Treasury by repurchasing $935 million of trust capital securities issued under the TARP Capital Purchase Program. It funded the repurchase through a mix of available cash and roughly $400 million from the proceeds of its $450 million issuance of 7% Senior Notes due 2019, which settled on July 1, 2014.

That repayment wasn’t just a balance-sheet event—it was a psychological one. Popular pointed to a Tier 1 common equity ratio of 15.9% at year-end, 110 basis points higher than in 2013 (a year that still included TARP capital). And crucially, the bank did it without issuing additional equity—buying back its independence while preserving ownership for shareholders. It also meant something very practical: more freedom to actively manage capital going forward.

Not long after, Popular did the other thing strong banks get to do in messy times: it consolidated. On February 27, 2015, Doral Bank—a $5.9 billion institution—was closed by Puerto Rico’s Office of the Commissioner of Financial Institutions, and the FDIC was appointed receiver. Popular, through Banco Popular de Puerto Rico, stepped in and acquired certain assets and assumed all deposits (excluding certain brokered deposits) of Doral Bank from the FDIC as Receiver, in alliance with other co-bidders. As part of the transaction, BPPR assumed approximately $1.0 billion in deposits held across eight of Doral’s 18 Puerto Rico branches and its online deposit platform, and acquired $848 million in performing residential and commercial loans in Puerto Rico.

The message was clear: the new Popular would use crisis as an opportunity. As competitors stumbled or failed, Popular got bigger—and more central to the island’s financial system. “This will provide stability to the financial system,” CEO Richard Carrión said at the time, noting the deal would increase Popular’s assets by about $2.5 billion.

Behind the scenes, the bank was also rebuilding the muscle it had lacked in the boom years. The focus shifted to operational execution: accelerating digital transformation, enforcing cost discipline, and tightening risk management and underwriting. Popular wasn’t trying to be everything everywhere anymore. It was trying to be excellent where it already mattered most.

Then, in 2017, the leadership baton passed. Richard Carrión—who had been the face of Popular for 26 years—stepped down as CEO effective July 1 and became Executive Chairman of the Board. Ignacio Alvarez succeeded him. Alvarez had served as President and Chief Operating Officer from 2014 to 2017 and as Chief Legal Officer from 2010 to 2014, and as CEO and President from 2017 to 2024 he oversaw the continuation of the Puerto Rico strategy and the restructuring of the remaining mainland operations.

By the time this pivot was fully underway, it was working. Popular’s profitability and capital position were stronger. And the timing mattered, because the bank was about to face a stress test that had nothing to do with credit cycles or consent orders.

Puerto Rico was about to go dark.

Hurricane Maria & The Ultimate Stress Test (2017)

On September 20, 2017, Hurricane Maria made landfall in Puerto Rico as a Category 4 storm, with winds reaching up to 155 miles per hour. It tore across the island from southeast to northwest, dumping torrential rain—some places recorded as much as 30 inches over 48 hours.

The island’s systems didn’t just strain. They failed.

Power, phone service, and internet went down. The grid was so badly damaged that the entire island lost electricity, and many residents relied on portable generators for months. Full restoration wouldn’t come until August 2018. The agricultural sector was crushed too, with the vast majority of banana and plantain crops wiped out, along with most root crops and tree plantations.

And then came the human toll. Maria became the second deadliest hurricane in U.S. history. The official estimate put deaths in Puerto Rico at 2,975, though a 2018 Harvard University study estimated the number at roughly 4,645. In damage, it ranked among the costliest hurricanes the U.S. has ever endured, with repairs estimated at $115.2 billion.

For Popular, Maria was the ultimate stress test—not just of branches and backup generators, but of whether the bank’s role in Puerto Rico was as essential as its history suggested. Ignacio Alvarez led the post-hurricane recovery effort, working to restore operations and meet the needs of customers, employees, communities, and regulators in the middle of an island-wide emergency.

The operational challenge was almost surreal. No power meant no electronic systems. No communications meant no reliable way to coordinate. ATMs were dark. Branches that could open did it on generators, reverting to paper ledgers and manual processes that banking had largely abandoned decades earlier. And suddenly, cash wasn’t a convenience. It was the difference between being able to buy food, water, and medicine—or not.

In San Juan, lines wrapped around Banco Popular branches as people waited, desperate to withdraw cash. Nearly a week after landfall, residents were still scrambling for the basics: gas, supplies, and money.

Popular’s employees effectively became first responders. Branches that were able to operate stayed open for extended hours. The bank coordinated with FEMA and government agencies to support relief distributions. And on the credit side, it leaned into forbearance—working with customers facing losses of homes, jobs, and businesses, instead of forcing the kind of immediate reckoning a normal operating environment might demand.

Then came the twist almost no one expected: the loan portfolio held up far better than feared. Even amid catastrophe, many customers prioritized their bank obligations. The relationship between Popular and Puerto Ricans—built over more than a century—turned out to be more than brand familiarity. It was trust under pressure.

As federal aid began flowing—disaster relief, reconstruction dollars, enhanced Medicaid payments—it moved through the banking system and into Popular’s accounts. Deposits grew even as the broader economy struggled.

And Popular’s response during Maria became reputational capital you can’t buy. “The bank that stayed when others might have left” stopped being a slogan and became lived experience for millions of people. Market share increased. Deposit growth accelerated. Where other institutions looked at Puerto Rico and saw only risk, Popular saw a chance to deepen the kind of advantage that only comes from showing up when it matters.

Richard L. Carrión, Chairman of Popular’s Board of Directors, later said, “The Board would like to thank Ignacio for his important contributions over the past 15 years. He joined Popular in 2010, when I was CEO, at a very challenging time for our organization and the financial industry. His counsel and support were invaluable and his highly strategic and collaborative approach quickly set him apart as a great leader. From his earliest days as CEO, he demonstrated his deep commitment to Popular's core values, as he steered our response in support of the many clients, colleagues and communities impacted by Hurricane Maria and the global pandemic.”

For investors, Maria clarified something that doesn’t show up cleanly in a spreadsheet: Popular’s franchise value extends beyond capital ratios and earnings power. Its cultural connection, its embedded role in day-to-day life, and the trust earned over generations proved more durable than concrete, steel, and even the grid itself.

The PREPA Bond Crisis & Restructuring Era (2015–2022)

Even before Maria, Puerto Rico was already buckling under the weight of its own promises. When Congress passed PROMESA, the territory was carrying more than $70 billion of debt and more than $55 billion in unfunded pension liabilities—without a workable legal mechanism to restructure and regain its footing.

The public unraveling started in 2014. The major credit rating agencies downgraded several Puerto Rico bond issues to junk after the government couldn’t convince markets it had a credible plan to pay what it owed. Once those downgrades hit, the government’s access to new borrowing effectively froze. With the bond market shut, Puerto Rico began burning through its own savings to cover obligations—while warning everyone that those reserves would eventually run out.

In 2016, Washington stepped in with an unusual solution: a custom-built restructuring framework designed specifically for Puerto Rico. The Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act—PROMESA—created a formal process to restructure the island’s debts and set up expedited approvals for certain critical infrastructure projects. It also created the Financial Oversight and Management Board, quickly nicknamed la junta on the island, which took oversight of the Commonwealth’s budget and became the central negotiator in the debt fight.

On June 30, 2016, President Barack Obama signed PROMESA into law. With legal protections from lawsuits now in place, Puerto Rico Governor Alejandro García Padilla suspended debt payments due the very next day, July 1.

For Popular, this was a different kind of stress test. Hurricanes and recessions are brutal, but they’re familiar. A sovereign-style debt crisis inside the U.S. financial system is something else entirely. Popular’s exposure to Puerto Rico government bonds was meaningful, but the bigger point was structural: as the island’s primary financial institution, Popular wasn’t just watching the restructuring from the sidelines. It was part of the machinery that had to keep running while the island renegotiated its future.

Over time, the Oversight Board and the Government of Puerto Rico restructured roughly 80% of the Commonwealth’s outstanding debt, reducing total liabilities from more than $70 billion to about $37 billion and projecting more than $50 billion in savings on debt service payments. The process, however, did not end cleanly across every corner of the government ecosystem—negotiations and litigation over the debt of Puerto Rico’s public utility continued.

By the early 2020s, the fiscal picture began to look less like free fall and more like stabilization. Puerto Rico’s audited government-wide financial statements for fiscal year 2022 showed a total net surplus of $1.9 billion, a sharp reversal from the net deficits that dominated prior years. And in its 2024 fiscal plan, the Oversight Board pointed to progress in aligning revenues and expenses, alongside the reality that most of the restructuring work envisioned by PROMESA had been completed.

The bottom line for Popular was that, while the haircuts on municipal bonds hurt, they were manageable—and the broader resolution of the debt crisis de-risked the entire environment the bank depended on. A more stable government balance sheet improves confidence, investment, and everyday economic activity. And for a bank whose franchise is inseparable from the island, that stability matters.

For investors, the debt crisis put Popular’s unique position into sharp relief. The bank was exposed to Puerto Rico’s problems, but it was also indispensable to solving them. Popular couldn’t sidestep the fiscal storm—but it was always going to have a seat at the table when the path forward was negotiated.

Modern Era: Digital Transformation & Mainland Return (2018–Present)

In the years after Maria, Popular started to look like a different kind of bank. When the island went dark, it exposed just how dependent modern banking had become on power, networks, and centralized systems. Coming out the other side, Popular didn’t treat digital as a nice-to-have. It treated it as resilience. The crisis forced an acceleration that, in normal times, would have taken years—upgrading online and mobile tools while still leaning on the branch network that had proven so essential when everything else failed.

Management framed the moment as a return to offense, but with guardrails. As the company put it:

"Our strong capital and liquidity position allowed us to recommence share buybacks and increase our dividend during 2024. We are also pleased by the acceleration in the pace of our Transformation, which is already generating tangible results. We are making meaningful progress in the modernization of our customer channels and enhancement of our customers' experience. I am thankful for our employees' hard work and dedication throughout the year and optimistic about our prospects for 2025 as we continue to leverage the improved performance of the Puerto Rico economy and the strength of our franchise."

The results showed up in performance. Popular reported net income of $177.8 million in Q4 2024, up from $155.3 million in Q3 2024. For full-year 2024, net income was $614.2 million, compared to $541.3 million in 2023. Revenue also moved higher: $2.68 billion in 2024 versus $2.56 billion the year before, while earnings rose to $612.80 million, up 13.50%.

In other words, this wasn’t just a “good Puerto Rico story.” It was a bank putting up numbers that compared well against peers, including a trailing twelve-month return on equity of 12.22%, ahead of the industry average of 9.74%.

Just as important: the mainland chapter restarted, but this time without the old ambition trap. In 2018, Popular Community Bank changed its name to Popular Bank (Legal name) and Popular, commercial name. The strategy shifted from spreading across too many competitive markets to focusing on places where Popular already had a right to win—New York, New Jersey, and Florida—markets with established presence and deep Hispanic community ties.

Balance-sheet growth followed, led by the island franchise. Deposits grew to $67.2 billion, up $1.7 billion over the second quarter of 2024, driven by growth in Puerto Rico public deposits, which totaled $20.9 billion at quarter-end. Loans held in portfolio rose 7.3% year over year to $38.2 billion, with growth across commercial, construction, mortgage, and auto lending.

And with capital levels stronger, Popular leaned into shareholder returns. In August 2024, it initiated a $500 million share repurchase program, with $160 million remaining available as of March 31, 2025.

Leadership, too, reflected the theme of continuity over reinvention. Popular, Inc. ("Popular" or the "Corporation") (NASDAQ: BPOP) announced today that Ignacio Alvarez will retire effective June 30, 2025 after serving as Chief Executive Officer ("CEO") since 2017. He will be succeeded by Javier D. Ferrer, currently President and Chief Operating Officer ("COO").

As President and Chief Operating Officer of Popular, Ferrer has been responsible for overseeing all business lines and the Strategic Planning and Data and Analytics functions of the Corporation. He has also been instrumental in the execution of Popular's Transformation program.

For investors, the modern era is Popular’s argument that it learned the right lessons. Don’t chase growth for its own sake. Keep the balance sheet strong enough to survive the next shock. Invest in the channels customers actually use. And when you go to the mainland, do it with discipline—building where the brand has roots, not where the market is loudest.

The Puerto Rico Economy Today & Popular's Role

Puerto Rico’s economy is full of contradictions. The population is still shrinking—the 2020 Census counted 3.2 million residents, down from 3.7 million a decade earlier. And yet, on a per-person basis, incomes have been rising. Part of that is simple math: many of the people leaving are lower-income residents, while some of the newcomers have more money.

A big driver of that “newcomer” story is Puerto Rico’s Tax Incentives Code, known as Act 60. In a few years, it has gone from niche policy to dinner-party lore in finance and crypto circles. The pitch is straightforward: move to Puerto Rico, establish bona fide residency, and you may be able to dramatically reduce U.S. federal taxes on Puerto Rico-sourced income.

Under Act 60, qualifying Puerto Rican corporations can pay a 4 percent corporate tax rate, and individual residents pay zero percent tax on capital gains accrued after establishing bona fide residency, plus a full exemption on interest and dividends.

Those incentives—formerly Acts 20 and 22—have pulled in a wave of wealthy transplants: tech entrepreneurs, cryptocurrency investors, hedge fund managers. On the island, it’s politically and socially fraught, in part because of pressure on housing costs. For Popular, though, the banking implication is pretty direct. High-balance customers tend to bring deposits, activity, and fee opportunities.

At the same time, federal dollars have been flowing into Puerto Rico at levels the island hasn’t seen in decades—through infrastructure investment, disaster relief, and enhanced healthcare funding. That money doesn’t just help rebuild roads and systems; it shows up in the banking system too, lifting deposit balances and creating lending demand tied to construction and development.

And here’s where Popular’s home-market advantage becomes very real. Puerto Rico isn’t a sprawling battlefield of dozens of banks. It’s concentrated. FirstBank Puerto Rico holds roughly 20% of deposits, and Oriental Bank (owned by OFG Bancorp) has around 12%. Together with Popular, those three control more than 85% of the market.

That kind of structure changes behavior. It favors incumbency. Popular’s mix of reach—its branch footprint—plus its digital capabilities and century-plus presence gives it real leverage in how customers choose a primary bank. And in an oligopoly, you typically see less irrational price competition and more stable margins.

The real question for investors isn’t whether Popular can win on the island—it already has. The question is whether Puerto Rico can sustain enough economic momentum to keep the flywheel turning, despite the demographic headwinds. Popular’s bet is that the deposit base stays supported by federal transfers and high-income migrants, lending stays disciplined as credit conditions improve, and the bank’s role as essential infrastructure keeps demand steady even when the macro picture gets messy.

Playbook: Business & Strategic Lessons

The Geographic Concentration Dilemma. Popular’s story is a reminder that dominance cuts both ways. On the island, scale compounds: more branches, deeper relationships, better local knowledge, and a brand people actually trust. On the mainland, those advantages didn’t travel. Popular was just another regional bank competing in crowded markets where it couldn’t lean on cultural familiarity in the same way, and where pricing and growth pressures nudged it into riskier lending. The lesson is uncomfortable but clear: sometimes the highest-return move isn’t to diversify—it’s to fully own the market where you have a real edge, even if that market looks “hard” from the outside.

Surviving Catastrophe. Hurricane Maria wasn’t just a disaster; it was a systems failure. Power, telecom, logistics, payments—everything modern banking depends on—collapsed at once. Popular held together because it had built more than infrastructure. It had built social capital: employees who showed up, customers who stayed, and a community that treated the bank as part of daily life. Wind and water can destroy buildings. They can’t erase trust and habit overnight. That intangible asset base turned out to be a form of resilience that spreadsheets don’t capture.

The Retreat Decision. Companies love to talk about “focus,” but very few leaders actually do the hard version of it—shrinking to get stronger. Popular’s pullback from the mainland meant selling branches, unwinding strategies, and admitting that an expensive growth story wasn’t delivering the right kind of returns. It drew criticism because it looked like giving up. In reality, it was a reset: concentrate resources where the bank had durable advantages and rebuild the balance sheet and operating discipline that the expansion years had diluted.

Regulatory Arbitrage and Risk. Puerto Rico’s status created a strange mix of tailwinds and traps. Popular got the benefits of operating inside the U.S. banking system—FDIC insurance, dollar-based deposits, and access to federal frameworks—while also living in an economy shaped by unique tax policies and political constraints. The debt crisis exposed the downside: territorial status didn’t guarantee the kind of smooth federal backstop people assume exists in the states. Popular benefited from the regulatory architecture, but it was also exposed to the gaps in it.

Crisis as Opportunity. Popular repeatedly turned moments of island-wide stress into consolidation. The Doral Bank acquisition was the cleanest example: a competitor failed, and Popular stepped in to absorb deposits and assets, increasing its centrality to Puerto Rico’s financial system. After Maria, a similar dynamic played out more quietly—when people needed stability, they gravitated toward the institution that was open, functioning, and present.

Management Quality. In banking, survival is often about capital and funding. Excellence is often about people and judgment. The Carrión family built a culture rooted in long-term reputation and community presence, which helped Popular endure shocks that would have broken a less trusted institution. Ignacio Alvarez brought discipline and operational focus in the turnaround years, and the planned succession to Javier Ferrer signals that Popular is prioritizing continuity in that playbook rather than another reinvention.

Capital Allocation Evolution. Popular’s capital story is also its maturity story. The mainland years were defined by growth and acquisition momentum. The post-crisis era has been defined by caution, balance sheet strength, and capital returns when the bank could afford them. The return of buybacks and dividend growth isn’t just a reward to shareholders—it’s evidence that Popular absorbed the core lesson of its near-death experience: expansion is optional, but resilience isn’t.

Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Porter's 5 Forces

Threat of New Entrants: LOW. Puerto Rico is a hard place for a new bank to “just show up.” The island’s geography alone weeds out a lot of would-be competitors, and after watching the debt crisis and Hurricane Maria, most mainland banks have had little appetite to jump in. Regulation is another barrier—any entrant would face intense scrutiny from day one. But the biggest hurdle is softer: banking in Puerto Rico is still relationship-driven, and trust is already spoken for. The real pressure comes from fintech and digital-first banks, which can compete without building branches or a legacy footprint.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW. In a bank, the main “supplier” is deposits, and Popular sits in a market where deposits have been plentiful—boosted by federal transfers, Act 60 migration, and limited local options for where to park savings. That keeps the cost of funds relatively low versus many mainland peers. And when it needs to, Popular can still tap mainland capital markets for wholesale funding.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE. The island’s oligopoly structure limits how much leverage most customers have—there simply aren’t endless alternatives. Switching is also annoying in the way switching banks always is: moving direct deposits, resetting auto-pay, rebuilding credit relationships. That said, commercial clients tend to be more price-sensitive than retail customers, and digital banking has lowered friction enough that switching is easier than it used to be.

Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE TO HIGH. Banking’s competitors aren’t always banks anymore. Fintech products, crypto, peer-to-peer lending, and credit unions all fight for pieces of the same wallet share. Mainland banks can also serve more customers remotely than ever. Credit unions, in particular, remain active in Puerto Rico. Still, plenty of high-stakes moments are stubbornly physical—mortgage closings, complex business banking, wealth management—and Popular’s combination of branches plus digital tools is built to meet customers in both worlds.

Competitive Rivalry: MODERATE. In an oligopoly (Popular, FirstBank, Oriental), competition tends to be more rational than ruthless. With population decline limiting total market growth, banks compete more on service, reach, and reliability than on suicidal price wars. One area where the fight has picked up is the Act 60 segment, where higher-balance customers attract disproportionate attention.

Hamilton's 7 Powers

Scale Economies: ★★★★☆. With roughly 40% market share in Puerto Rico, Popular gets the classic benefits of scale: it can spread big fixed costs—technology, compliance, branches—across the largest base on the island. The catch is that Puerto Rico is still Puerto Rico. There’s a natural ceiling to how large a Puerto Rico-centric institution can become, and Popular will never have the raw scale advantage of mainland mega-banks.

Network Effects: ★★☆☆☆. Banking has some network-like elements, but it rarely turns into winner-take-all. Popular benefits modestly from payments scale—ATMs, acceptance, reach—but it’s not a true network-effects business. Its processing subsidiary (originally EVERTEC, later separated) did show more traditional network characteristics, but Popular ultimately spun it off.

Counter-Positioning: ★☆☆☆☆. Popular is a classic bank. It hasn’t built a fundamentally new model that incumbents can’t copy without cannibalizing themselves. There’s no real counter-positioning advantage here.

Switching Costs: ★★★☆☆. Switching costs are real, just not absolute. For retail customers, the stickiness comes from direct deposits, auto-pay setups, and an existing credit history with the bank. For commercial customers, the glue is stronger: credit facilities, treasury-management integrations, and relationship knowledge that takes time to rebuild. Digital tools have chipped away at these barriers, but inertia still does a lot of work.

Branding: ★★★★☆. In Puerto Rico, Popular isn’t just a brand—it’s the default mental category for “bank.” That identity is built on ubiquity, familiarity, and trust accumulated over generations. Hurricane Maria strengthened it, because Popular didn’t just advertise community commitment; it demonstrated it. On the mainland, though, that brand power fades quickly. Popular is far less known, which limits how much its island reputation can fuel expansion.

Cornered Resource: ★★★☆☆. Popular’s island footprint is hard to replicate: branch locations, regulatory approvals, an experienced workforce, and deep relationships with government and major employers. None of these are “unique” in a theoretical sense, but in practice they’re incredibly difficult for a newcomer to assemble from scratch in Puerto Rico.

Process Power: ★★★☆☆. The post-crisis version of Popular built real process advantages: tighter risk management, better operational discipline, and improved efficiency. Add in cultural competency—bilingual service and fluency in local business norms—and the bank can deliver a quality of service that’s harder to copy than it looks.

Overall Assessment: Popular’s durable power comes from Scale Economies, Branding, and Cornered Resource inside a geographically protected market. The tradeoff is structural: those same strengths don’t travel well to the mainland, which helps explain why the first expansion wave went sideways. Popular’s moat is real—but it surrounds a market with a built-in growth ceiling.

Bull vs. Bear Case

Bull Case

Popular is operating from a position most regional banks would envy. After the near-death experience of 2008 and the hard reset that followed, it rebuilt into something closer to a fortress: a high-capital, high-liquidity bank with room to maneuver when the next shock arrives. That strength has translated into solid profitability too, with a trailing twelve-month return on equity of 12.22%, ahead of the industry average of 9.74%. The simple bull argument is that this is a disciplined bank earning above-peer returns—and the market still hasn’t fully given it credit.

A big reason why is macro support that’s hard to ignore. Federal dollars have continued flowing to Puerto Rico through infrastructure spending, disaster relief, and healthcare funding. Those funds tend to show up in deposits first, then ripple outward into construction, consumption, and lending demand.

There’s also a case that the island’s demographic story is shifting from “shrinking” to “stabilizing,” and that the mix may matter more than the headline. Act 60 tax incentives continue attracting high-income individuals and entrepreneurs. Whatever you think of the politics, the banking implication is straightforward: more high-balance deposits, more payments activity, and more opportunities for fee income.

Then there’s market structure. Puerto Rico banking is concentrated, with Popular, FirstBank, and Oriental controlling over 85% of deposits. In a market like that, competition tends to be more rational, pricing is less suicidal, and incumbents can earn better economics than they could in a fragmented mainland battleground.

Finally, the bull case leans heavily on a lesson Popular learned the hard way: don’t chase growth for its own sake. The mainland business today is meant to be selective and profitable, not sprawling and volatile. And with capital allocation now oriented toward shareholder returns rather than empire-building, the upside is simple: if execution stays strong and sentiment improves, Popular’s valuation discount to book value and to mainland regional peers could narrow.

Wall Street, at least on the surface, is leaning optimistic. According to 8 analysts, the average rating for BPOP stock is "Buy." The 12-month stock price target is $132.75, which implies a 16.36% increase from the latest price.

Bear Case

The bear case starts with one word: concentration. Popular is still, in many ways, a Puerto Rico bank with some mainland operations on the side. That means the franchise is exposed to the island’s realities—population decline, aging demographics, and a heavy dependence on federal transfers. A single severe hurricane, a shift in federal funding priorities, or an adverse political change could hit deposits, credit quality, and operations at the same time.

Even with the debt restructuring progress, Puerto Rico’s economy remains vulnerable. Fiscal stabilization doesn’t automatically translate into long-term productivity gains, and labor market constraints can keep growth below what optimists expect.

Then there’s climate risk, which isn’t theoretical. As hurricanes grow more frequent and intense, Popular’s exposure becomes existential: a Maria-level event doesn’t just cause loan losses; it can disrupt the bank’s ability to function as infrastructure precisely when customers need it most.

Technology is another pressure point. Popular has invested heavily in digital capabilities, but fintech and digital-first alternatives keep lowering switching costs—especially for younger customers. Over time, what has historically been a moat—the physical network—could start to look more like a cost burden.

And the valuation discount may not be a temporary misunderstanding. The “Puerto Rico discount” could be permanent if investors decide that no amount of operational excellence fully compensates for geographic and political risk.

Speaking of politics: Puerto Rico’s tax status, federal benefit eligibility, and Act 60 itself are all policy-dependent. Changes to any of those could reshape the island’s economy—and by extension, Popular’s deposit base and growth opportunities.

Finally, even though the second mainland chapter is more disciplined, it’s still not fully proven. Popular’s history suggests it’s strongest inside its island fortress, and expansion beyond that has to fight gravity.

Key Metrics to Watch

For investors monitoring Popular’s trajectory, three signals do most of the work:

- Puerto Rico deposit growth rate — the clearest read on franchise strength and the flow-through of federal dollars

- Net charge-off ratio — the best real-time indicator of credit stress and underwriting discipline

- Return on tangible equity — the bottom-line measure of whether the bank is converting its advantages into durable shareholder returns

Together, these tell you whether Popular is keeping its core engine healthy, protecting the balance sheet, and earning the right to outgrow its “Puerto Rico discount.”

Epilogue & Future Outlook

Popular, Inc. sits at an inflection point, but not the kind most companies get to choose. It has already been dragged through the sort of decade that ends franchises: a long recession, a historic government debt crisis, Hurricane Maria, and then a global pandemic. Yet here it is—still standing, and in many ways stronger. The retreat from the first mainland expansion wasn’t just a defensive move; in hindsight, it was the decision that kept the company’s strengths intact. And by any reasonable standard, the recent financial performance has been impressive.

That sets the stage for the next chapter: leadership transition without a strategic reinvention. Javier D. Ferrer, Popular’s President and Chief Operating Officer and the incoming CEO, framed the moment like this:

Javier D. Ferrer, President and Chief Operating Officer, said, "The opportunity to lead Popular is tremendously exciting. I am truly honored by the trust our Board has placed in me and deeply grateful for Ignacio's confidence and mentorship over the years. Ignacio has developed a strong foundation to build upon. Popular's heritage and its ability to positively impact so many individuals, businesses and communities is an important asset, accompanied by a great responsibility. I look forward to our future with optimism, fully committed to continue to work with our great teams to strengthen our organization, with a strong focus on delivering exceptional customer service, innovate and modernize our technology, and foster a culture of agility and performance to deliver increasing value to our stakeholders."

And still, the core question doesn’t go away. Can a bank so tied to Puerto Rico deliver long-term shareholder value in a market facing demographic decline?

The optimistic case says yes: per-capita economics have improved, federal funds continue to flow, higher-income in-migration is real, and Popular operates from a position of strength in a concentrated market. If you’re going to be geographically concentrated, the argument goes, this is about as good as it gets—dominant share, trusted brand, and a balance sheet built to absorb shocks.

The pessimistic case says the discount exists for a reason. Trees don’t grow to the sky. At some point, population decline, climate risk, and competitive disruption will take their toll. Under that view, today’s strength is genuine, but it comes with an unavoidable ceiling—and investors are rational to demand a margin of safety.

But if there’s one insight that explains Popular better than any debate over multiples, it’s this: Popular’s advantage has often been the power of staying. When the mainland expansion didn’t work, management had the discipline to retreat. When Maria devastated the island, employees showed up. When competitors failed, Popular consolidated. When others might have looked at Puerto Rico and seen only risk, Popular leaned further in.

That kind of commitment—to a community, to a market, to an identity—creates value that doesn’t fit neatly in a model. Popular’s cultural significance on the island is a competitive asset no amount of capital can manufacture on demand.

For founders and investors, the lesson is simple and hard: sometimes the best strategy isn’t the most exciting one. Patient dominance in a difficult market can beat the adrenaline of chasing new geographies—especially when you already have a moat that’s real, trusted, and reinforced by lived experience.

Popular has been serving Puerto Rico for more than 130 years. The Carrión family’s original vision of a “people’s bank” evolved into a modern financial institution, but the role is basically the same: essential to everyday life on the island. Whatever comes next, that foundation is the closest thing banking has to durability.

The bank that stayed when others might have left. That’s Popular, Inc.

Further Reading

Primary Sources: - Popular, Inc. annual reports and SEC filings (2008–2024) — the clearest record of what happened in the crisis years, what changed afterward, and how the business rebuilt - Financial Oversight and Management Board reports — the best window into Puerto Rico’s restructuring process and the policy environment banks had to operate inside - Federal Reserve Bank of New York reports on Puerto Rico — reliable macro context on employment, migration, and the island’s recovery patterns

Books for Context: - Fantasy Island: Colonialism, Exploitation and the Betrayal of Puerto Rico by Ed Morales — a readable, sobering map of the political economy behind Puerto Rico’s modern reality - 7 Powers by Hamilton Helmer — the strategic framework used to think about moats, and why Popular’s advantages are strongest at home - The House of Morgan by Ron Chernow — broader banking history and the recurring patterns that show up in every financial empire story

Trade Press: - American Banker coverage of Popular’s mainland exit, turnaround years, and the more disciplined “mainland chapter 2.0” - Caribbean Business and News Is My Business — day-to-day reporting that captures what it feels like on the ground in Puerto Rico banking

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music