Broadstone Net Lease: The Quiet Evolution of Triple Net Real Estate

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

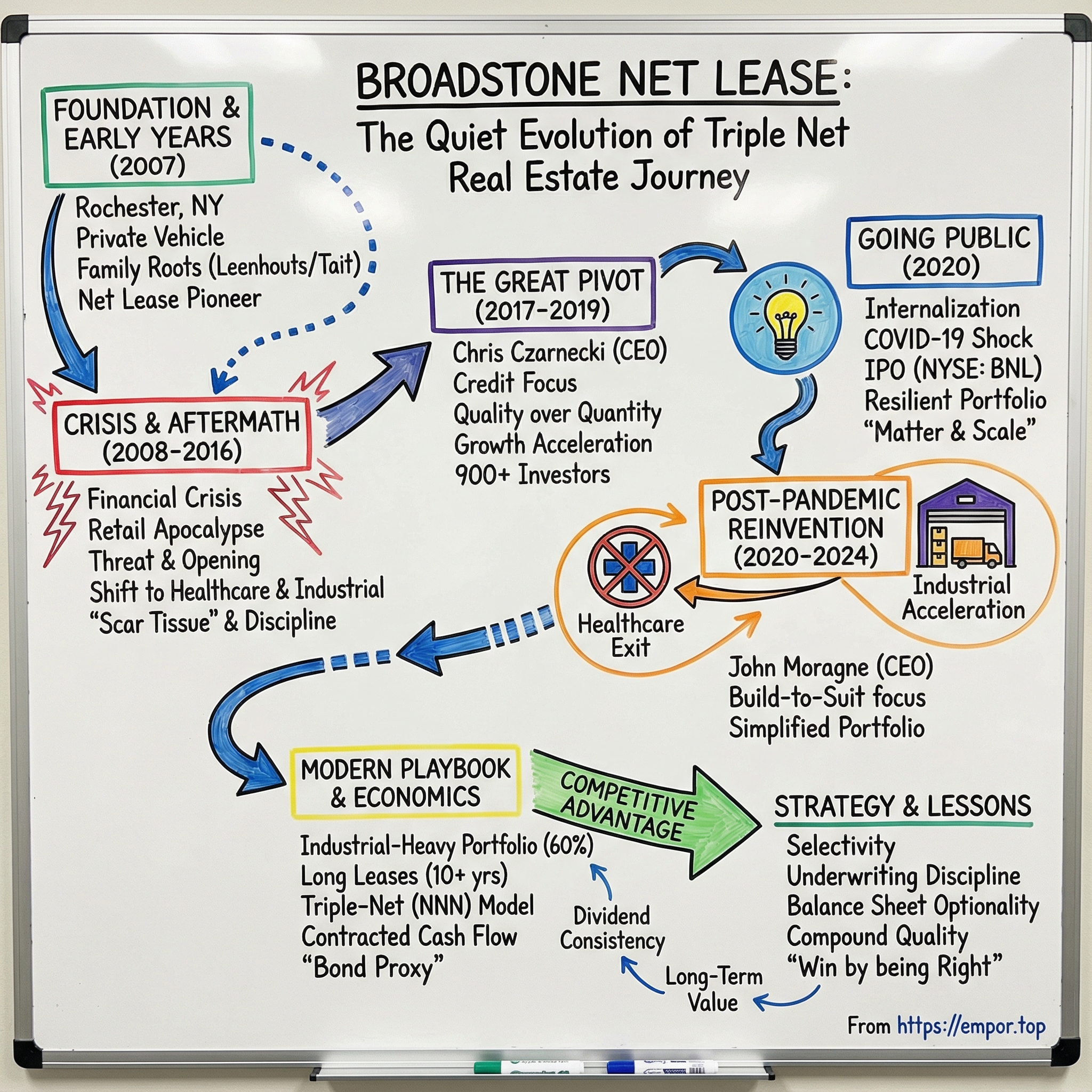

Picture a small office building in suburban Rochester, New York, around 2007. Inside, a handful of real estate professionals were putting together what, on the surface, looked like one more private real estate vehicle—one of thousands riding America’s commercial property boom. Nothing about it screamed “future public company,” let alone “best-in-class net lease REIT.” And yet, over the years, that quiet operation evolved into something rare in real estate: a platform defined less by hype and more by discipline—reinventing itself while much of the sector chased yield wherever it could find it.

Today, Broadstone Net Lease, Inc. (NYSE: BNL) is a diversified net lease REIT with a portfolio that leans heavily industrial. It owns primarily single-tenant commercial properties leased on a long-term, triple-net basis to a wide range of tenants. With a market cap around $3 billion and roughly 760 properties spread across 44 U.S. states and Canada, Broadstone sits in an interesting lane: big enough to have real scale, small enough to stay selective, and steady enough to have pulled off a decade-long transformation without blowing itself up.

That transformation is the point of this story. How did a Rochester-based, family-rooted real estate business go from being a diversified net lease operator with meaningful healthcare exposure to an industrial-focused REIT with one of the higher-quality portfolios in the net lease space? And what does that journey teach us about capital allocation, strategic patience, and what “competitive advantage” can even mean in a business that, from the outside, looks like it’s just collecting rent checks?

Broadstone’s public description is simple: formed in 2007, grounded in credit analysis and real estate underwriting, and built to produce predictable cash flow through cycles. All true. But it leaves out the more interesting part—how a conservative financial philosophy survived a series of strategic turns, how the company repeatedly chose quality over the fastest growth, and how it managed those shifts without torching shareholder value or relying on desperate, dilutive capital.

In an industry where “bigger” is often treated as the strategy, Broadstone tried something else. This is the story of how it got there.

II. Foundation & Early Years: The Net Lease Pioneer

Broadstone didn’t start with a single “aha” moment. It started with something rarer in real estate: accumulated scar tissue.

In 2006, Norman Leenhouts co-founded Broadstone alongside his daughter, Amy Tait, and her husband, Bob Tait. Leenhouts served as Chief Investment Officer and as an officer and director across the firm’s two private real estate investment trusts. This wasn’t a Silicon Valley-style startup. It was the next chapter of a family business that had been watching real estate and capital markets rise, fall, and rise again for decades.

Amy’s most important mentor was the one she grew up with: her father. Norman and his identical twin brother, Nelson—both University of Rochester graduates—co-founded Home Leasing Corp. back in 1967. It began in affordable housing and steadily expanded. In 1994, the business went public as Home Properties Inc., growing into a multifamily REIT that eventually reached more than $6 billion in market capitalization before being acquired by Lone Star Funds in 2015 for $7.6 billion. The lesson the family took forward wasn’t “grow fast.” It was “survive cycles.” Conservative financing, underwriting discipline, and respect for downturns were already baked into the DNA by the time Broadstone was formed.

Amy Tait would later retire in 2021 as Founder and Chairman of Broadstone Net Lease, a REIT with more than $4 billion of commercial properties across the United States. Before that, she served as Founder, CEO, and Chairman of Broadstone Real Estate, which sponsored three private REITs.

To understand what Broadstone was building, you have to understand the structure at the core of the business: the triple-net lease.

In a triple-net, or NNN, lease, the tenant pays the property’s operating expenses—real estate taxes, insurance, and maintenance—on top of rent and utilities. That changes the job of the landlord. Instead of running buildings day to day, the landlord is primarily underwriting tenants and structuring long-duration cash flows. The building matters, but the credit matters more.

As one industry analyst put it, triple-net REITs have historically stood out in downturns for dividend security and stock performance, helped by long-term leases—often 15 to 20 years—typically conservative financing, and a business model that avoids construction risk.

For tenants, the appeal is just as straightforward. A sale-leaseback with a triple-net REIT lets a company pull capital out of real estate it already owns, without giving up operational control of a mission-critical facility. It turns a fixed asset into fuel for the operating business. For the REIT, it creates a long-term rent stream with minimal ongoing responsibilities.

Think of it like this: if a net lease REIT buys a company’s headquarters for $100 million and leases it back at a 5% lease yield, the economic effect resembles providing $100 million of capital at a 5% cost. The tenant gets liquidity to invest back into the business; the landlord gets contracted income. If the tenant uses that capital well, their credit strengthens—making the arrangement better for both sides.

Broadstone started as a private REIT, raising money from individual investors through private placements rather than launching with a big institutional check. That approach kept early growth controlled. The company’s first closing of a private investment offering to outside shareholders was December 31, 2007—almost perfect timing in the worst possible way, just as the global financial system began to crack.

Still, the platform grew. Within a decade, Broadstone’s investor base expanded beyond friends and family to more than 900 investors across three continents. Along the way, it also ventured beyond its core net lease focus into single-family rental housing.

By 2015, Broadstone Net Lease—its largest private REIT—reached $1 billion in total market capitalization. The portfolio had become notably diverse. “For a fairly small portfolio, we’ve got a huge amount of diversification, both in terms of geography and industry,” Amy Tait said at the time. “We have 320 properties in 32 states. Our largest tenant is Siemens Corp. at 5.7 percent of revenue.”

That early diversification was both a risk-management choice and a reflection of private-market dealmaking: you take good opportunities where you can find them. Unlike giant public REITs that can narrow their aperture to a specific property type, Broadstone needed to stay flexible. The result was a portfolio that was durable, but not yet sharply defined—something the company would eventually have to address head-on.

III. Building Through Crisis: Navigating the Financial Crisis and Its Aftermath

Broadstone’s timing was brutal. It raised outside capital at the end of 2007—basically the moment the floor dropped out from under global real estate. Credit markets seized up. Property values sank. Tenants got shaky. And the types of businesses that often anchor net lease portfolios, especially retail, were suddenly fighting for survival as consumer spending dried up.

But the crisis also exposed what Broadstone actually was: not a growth-at-all-costs shop, but a risk-management shop. The conservative approach to leverage that Norman Leenhouts had spent a career preaching wasn’t a slogan—it was a survival trait. While plenty of real estate investors were forced into fire sales or refinancing gymnastics just to stay alive, Broadstone had enough balance-sheet flexibility to keep making rational decisions.

And then came the longer, more structural problem. The financial crisis didn’t just knock retail down for a couple of years—it accelerated a shift that would become known as the retail apocalypse. Shopping centers that had once been treated as steady, almost bond-like cash flow started to look like melting ice cubes. Traffic declined at power centers anchored by department stores. Restaurant concepts that once seemed “safe” began failing. The old conventional wisdom—retail is king, shopping centers are stable—wasn’t just wrong. It was being dismantled in real time.

For Broadstone, that was a threat and, quietly, an opening.

The threat was straightforward: any meaningful retail exposure was now a source of creeping risk. The opening was more subtle: distress creates inventory. As weaker owners flooded the market with assets, the buyers who could still transact—and who could still say “no” to the wrong deals—had the chance to pick up quality properties at attractive prices. The trick was distinguishing what was temporarily distressed from what was permanently impaired.

This is where Broadstone started doing the work that would define the next decade: repositioning, steadily and without theatrics. Instead of chasing yield in struggling retail, management leaned more into property types that looked better built for the new economy—industrial and healthcare.

When Chris Czarnecki joined the then-private company in 2009, Broadstone was barely out of infancy: just over a year old, with fewer than 10 employees. Even at that size, it was already beginning to separate itself from plenty of net lease investors by edging into healthcare and industrial, rather than doubling down on what had worked last cycle.

The shift wasn’t dramatic. It was methodical. Deal by deal, Broadstone reduced its reliance on retail and increased exposure to categories with stronger long-term demand. That meant selling some retail assets—even when it hurt—and redeploying the capital into industrial, healthcare, and restaurant properties.

Healthcare, in particular, fit the company’s temperament. The aging U.S. population created durable demand for medical services. Many healthcare properties were occupied by hospital systems or physician groups with solid credit. And while retail was being hollowed out by e-commerce, healthcare wasn’t—patients still needed physical locations for exams and procedures.

Industrial offered a different kind of resilience: tailwinds. The very forces hammering brick-and-mortar retail were fueling demand for warehouses and logistics facilities. Companies needed more distribution capacity, not less. Last-mile delivery became more valuable. The reshoring of manufacturing created more demand for production and industrial space. Broadstone started building exposure to those trends early, before “industrial” became the default answer for every real estate investor.

By 2016, the platform was large enough to show what this repositioning looked like in practice. Broadstone Net Lease acquired 88 properties across 22 transactions for $518.8 million, bringing the portfolio to 428 properties. It raised $290.8 million in equity capital and delivered an 11.22 percent total return to investors that year.

IV. The Great Pivot: Strategic Transformation Takes Shape

By 2017, Broadstone was ready for its next major evolution. Christopher J. Czarnecki, who had joined the company in 2009 when it was still tiny, was promoted to Chief Executive Officer of BRE, BNL, and BTR. Up to that point, he had served as President and Chief Financial Officer of BRE and BNL—meaning he already had his hands on the two things that matter most in net lease: capital and credit.

That credit emphasis wasn’t theoretical. Before Broadstone, from 2005 to 2007, Czarnecki worked as a commercial real estate lender and credit analyst at Branch Banking & Trust Co. That training—reading financial statements, stress-testing cash flows, and getting paid to worry—fit perfectly with where Broadstone wanted to go. Plenty of real estate executives are, at heart, property people. Czarnecki approached the business like a lender: the building matters, but the tenant’s ability to pay is the engine.

His education reinforced that analytical bent: a B.A. in Economics from the University of Rochester, a Diploma in Management Studies from the Judge Business School at the University of Cambridge, and an M.B.A. Put it together, and you get a CEO wired for underwriting discipline, not deal volume.

Broadstone had also grown up. As Amy Tait put it, “In the time since founding Broadstone more than a decade ago, we have expanded our organization to include more than 80 smart and ambitious professionals working in five states who oversee more than $2 billion in properties located in 37 states, and serve over 2,000 high and ultra-high net worth investors from all over the US as well as other countries.”

Under Czarnecki’s leadership, that steady repositioning turned into real acceleration. Broadstone acquired more than $500 million of net leased real estate each year from 2015 through 2019, including roughly $1.0 billion of acquisition activity during 2019. By June 30, 2020, the portfolio had grown to 633 properties with gross asset value of approximately $4.0 billion.

But the headline wasn’t just growth. It was what that growth was designed to accomplish.

The transformation strategy had a few clear pillars. Broadstone would keep pushing the portfolio away from retail and further toward industrial and healthcare. It would keep widening its geographic footprint to avoid concentration risk. It would keep diversifying tenants so no single credit could become a portfolio-level problem. And, most importantly, it would prioritize quality over quantity—accepting lower yields if that meant better real estate and stronger tenants.

That last choice is where Broadstone quietly separated itself. In net lease, the easiest way to pump near-term returns is to buy higher cap rate deals—which often means taking on weaker credits, shorter lease terms, or less desirable locations. Those deals can make the numbers look great today and support a higher dividend, but they tend to hand you the bill later: more defaults, more vacancies, and more value erosion when leases roll.

Broadstone went the other way. It was willing to take a modestly lower initial yield in exchange for durability. Not because it sounded virtuous, but because it was a compounding strategy: build a portfolio that holds up through cycles, earns trust in the market, and ultimately gets valued at a premium. In other words, Broadstone wasn’t trying to win the quarter. It was trying to win the decade.

V. Going Public: The IPO and Modern Broadstone

By 2019, Broadstone had done the hard part: it had a real portfolio, a real process, and a real track record. The next step was getting public-market access. But before it could ring the bell at the NYSE, it had to fix something public investors had come to hate: the external management structure.

In November 2019, BNL announced a definitive agreement to internalize the management functions that were being performed by Broadstone Real Estate, LLC. In plain English: the REIT was going to bring the management team in-house, instead of paying a separate “manager” company to run it for fees.

The board approved a series of mergers that made the internalization effective on February 7, 2020. On closing, the upfront consideration paid to the manager totaled $300 million across cash, stock, and operating partnership units, with the potential for an additional earnout of up to $75 million.

This wasn’t just governance cleanup. In the public REIT world, external management often signals misaligned incentives and conflicts of interest—exactly the kind of thing that can keep investors on the sidelines. Internalization made Broadstone easier to understand, easier to own, and more clearly aligned: management wins when shareholders win.

The structure also showed how carefully Broadstone thought about deal mechanics. The $300 million upfront price included roughly $206 million for the manager’s equity—more than 80% paid in BNL common stock and operating company membership units—plus the assumption of approximately $94 million of debt. The earnout, up to $75 million, was split into four tranches and tied to either share price performance after an IPO or AFFO per share before an IPO.

And then the world changed.

In March 2020, COVID-19 hit—right as Broadstone was lining up its public debut. Markets sold off. The IPO window effectively shut. Lockdowns began. For plenty of companies, that would have been the end of the story, at least for a while.

For Broadstone, it became a live-fire test of the portfolio it had spent a decade rebuilding.

Yes, restaurants—still a meaningful part of the portfolio—came under pressure as dining rooms closed and traffic evaporated. But industrial sites stayed open, doing exactly what the pandemic economy demanded: moving goods, supporting supply chains, and serving as the physical backbone of surging e-commerce. Healthcare saw disruption too, but proved far more resilient than most property types. The diversification Broadstone had been quietly compounding for years suddenly looked like the point, not just a preference.

Broadstone ended up among the best-performing net lease REITs in 2020 on rent collection metrics, helped by the simple fact that it wasn’t overexposed to any one tenant category, region, or single macro shock.

By September 2020, markets had recovered enough for Broadstone to go for it. The company completed its initial public offering of 33,500,000 shares of Class A common stock at $17.00 per share, for estimated net proceeds of $533.5 million. Trading began on the New York Stock Exchange on September 17, 2020 under the ticker symbol “BNL”.

Broadstone raised more than $588 million through the IPO, earmarking the capital for future acquisitions and for paying down unsecured debt and its revolving credit facility.

There was one wrinkle that stood out at the time. According to J.P. Morgan, about 16% of Broadstone’s tenants were rated investment grade at IPO, versus roughly 36% for its peer group. But that wasn’t Broadstone chasing lower quality—it was Broadstone operating in a part of the market where many solid tenants simply didn’t have public ratings. The company’s bet was that fundamentals mattered more than labels, and that disciplined underwriting could identify strong operators even without a formal stamp.

Czarnecki was clear about what public scale meant for them. “Given our size, that is meaningful external growth,” he said. As a public company, Broadstone was “large enough where we matter and people want to hold our stock, but not so large that we need to do $3 billion to $5 billion worth of acquisitions a year to deliver superior results.”

VI. The Post-Pandemic Reinvention: Healthcare Exit and Industrial Acceleration

After the IPO, Broadstone didn’t take a victory lap. It did what it had been doing for years: kept tightening the portfolio around what worked. The industrial tilt continued, but the post-pandemic era brought a sharper call—Broadstone would exit healthcare almost entirely.

Management framed it less as a change of heart and more as a recognition of friction. “As I've highlighted in recent quarters, we continue to focus more heavily on net lease industrial assets, while continuing to have deep conviction in net lease retail and restaurant assets, and have taken a hard look at property types that don't fit within our investment thesis, particularly clinical, surgical, and traditional medical office building assets,” said John Moragne, then serving as Chief Operating Officer. “Tenant bankruptcies, hands-on property management, heavier landlord responsibilities and costs, and messaging complexity in these properties has been an unnecessary distraction from our otherwise prudent and successful capital allocations.”

On paper, healthcare had always looked like a perfect defensive sector. In practice, it didn’t behave like the clean, low-touch triple-net model Broadstone wanted to scale. Clinical buildings meant specialized buildouts. Turnover was harder. And the “net” in triple-net was, at times, messier than it looked—more landlord involvement, more complexity, more ways for predictability to leak out of the model.

Broadstone’s response was decisive. It identified 75 healthcare assets for sale—about 11% of total annualized base rent—with the intent to redeploy the proceeds into its core targets: industrial, retail, and restaurant properties. Pro forma, selling all clinically oriented healthcare properties would cut healthcare exposure from 17.6% of the portfolio to 7.5% based on annualized base rent.

The most visible milestone came in May 2024, when joint venture partners Remedy Medical Properties and Kayne Anderson Real Estate announced they would acquire a portfolio of 37 healthcare properties from Broadstone for $252 million.

By the end of 2024, the strategy was largely complete. As of December 31, 2024, Broadstone had substantially finished simplifying its healthcare portfolio, bringing clinical and surgical assets down to 3.2% of annualized base rent, from 9.7% a year earlier.

This period also marked a major baton pass at the top. In early 2023, Broadstone’s board approved a succession plan that elevated John Moragne—from Executive Vice President and Chief Operating Officer—to Chief Executive Officer and board member, effective February 28, 2023. Chris Czarnecki stepped down as President and CEO but remained with the company in an advisory role through January 31, 2024.

Czarnecki had led Broadstone from 2017 to 2023, overseeing the $629 million IPO, expanding the portfolio to more than $5 billion in assets, and securing investment-grade credit ratings. He later joined Keller Williams in 2025.

Moragne, meanwhile, brought a different but highly compatible skill set to the CEO seat. He had been with Broadstone for years—Chief Operating Officer from 2018 to 2023, and before that General Counsel and Chief Compliance Officer from 2016 through 2018, plus Company Secretary from 2016 to 2021. Prior to joining Broadstone, he worked as a corporate, securities, and M&A attorney from 2007 to 2016, including providing legal counsel to the company since its inception in 2007.

That combination—legal precision, deal experience, and operational responsibility for acquisitions and portfolio management—made the transition feel less like a shift in direction and more like continuity. Same disciplined culture. Same underwriting-first mentality. Just with even less tolerance for anything that distracted from the cleanest version of the net lease playbook.

VII. The Modern Playbook: How Broadstone Competes Today

By the first quarter of 2025, Broadstone’s portfolio had a clear center of gravity: 59.8% industrial, 31.3% retail, and 8.9% other. Occupancy sat at 99.1%, and rent collections matched it. The balance sheet had real flexibility too, with $1 billion of total revolver capacity.

Zoom out a bit, and you can see what the machine looks like in full. As of December 31, 2024, Broadstone owned 765 individual net leased commercial properties—758 across 44 U.S. states and seven spread across four Canadian provinces—totaling about 39.4 million rentable square feet. Those buildings were leased to 202 tenants, and no single tenant represented more than 4.1% of annualized base rent.

The leases themselves tell the same story: built for durability, not drama. As of December 31, 2024, the ABR-weighted average lease term was 10.2 years, and the ABR-weighted average annual minimum rent increase was 2.0%.

That combination is the quiet engine of the strategy. Long lease terms create visibility. Built-in escalators create organic growth. And broad tenant diversification keeps any single credit from becoming an existential problem. Put together, it’s the kind of portfolio designed to keep producing steady, growing cash flow through different economic backdrops.

One place Broadstone has leaned harder in the modern era is build-to-suit development. Moragne called it “a fantastic place to allocate capital. We’re essentially building things that we couldn’t afford if we were trying to buy them straight off the market.”

That line captures the logic. Instead of showing up to a marketed deal process where everyone’s bidding against everyone—and returns get competed away—build-to-suit gives Broadstone a more proprietary path to high-quality assets. The trade-off is complexity: you’re managing construction timelines, coordinating with developers, and signing leases before the building is finished. But in exchange, you can often achieve better risk-adjusted returns than you’d get buying the same type of facility fully stabilized in the open market.

Looking ahead, management’s initial 2026 guidance called for about 4% adjusted funds from operations per share growth at the midpoint, supported by a $500–$625 million investment pipeline focused on industrial and retail acquisitions, build-to-suit developments, and asset management projects.

All of that feeds what most public REIT investors ultimately care about: the dividend. This portfolio and growth plan underpinned BNL’s roughly 6.6% dividend yield, and InvestingPro data showed the company had raised its dividend for six consecutive years.

Broadstone also pointed to strong economics in the build-to-suit pipeline, with a 7.5% initial cash capitalization rate and an 8.9% straight line yield. And on the capital markets side, a recent $350 million bond offering of 5% senior unsecured notes due 2032 was nearly seven times oversubscribed—an important signal that lenders were eager to fund the strategy.

None of this happens in a quiet corner of the market. Net lease is intensely competitive, and the biggest shadow over the whole sector is Realty Income—“The Monthly Dividend Company”—with a far larger, more diversified portfolio across retail, industrial, and office. In 2023, Realty Income generated roughly $4.0 billion in total revenue, a scale advantage that shapes everything from access to capital to sourcing.

And it’s not just public peers. Broadstone competes with virtually every form of real estate capital: other publicly traded REITs, private and institutional investors, sovereign wealth funds, banks, mortgage bankers, insurance companies, investment banks, and a wide ecosystem of lenders. Some of those competitors are larger, have deeper resources across leasing and underwriting, and—most importantly—may operate with a lower cost of capital or access funding sources Broadstone simply doesn’t have.

That’s the playing field Broadstone operates on today: win deals without overpaying, keep the portfolio clean, and use discipline—not size—as the edge.

VIII. Business Model Deep Dive: The Triple-Net Lease Economics

When the triple-net lease model works, it produces some of the cleanest, most predictable cash flow in real estate. That isn’t magic—it’s mechanics. In a true NNN lease, the tenant picks up the tab for the big operating expenses: property taxes, insurance, and maintenance. The landlord’s job shifts away from running buildings and toward picking the right tenants, structuring the right leases, and managing a portfolio through time.

That simple shift is why research has found REITs with net lease portfolios tend to be more operationally efficient than other property owners. There’s less day-to-day operational noise, fewer surprise bills, and a lot more visibility into what the next decade of rent is supposed to look like.

You can see the economics in Broadstone’s financial profile. Over the last twelve months, BNL posted a 94.76% gross profit margin—basically the business model in one number. When tenants pay the operating costs, most of the rent you collect flows through.

The lease terms matter, too. Triple-net REITs are often called “bond proxies” because long leases and contractual rent checks can make them hold up better during periods of stress. When the economy gets shaky, it isn’t just the property type that matters—it’s whether the leases are long, the rent is collectible, and the portfolio stays full.

That’s also why underwriting in net lease is different. In most real estate, the headline question is, “How good is the building in this market?” In net lease, the first question is, “How good is the tenant for the next 10 to 15 years?” The real estate still matters—especially for what happens if a tenant ever leaves—but tenant creditworthiness is the engine.

Broadstone’s industrial focus is built around that idea. It looks for properties that are mission-critical to the tenant’s operations: essential locations the tenant can’t easily replicate, where moving would be difficult or expensive. It also targets industrial sites near major transportation infrastructure—airports, ports, rail lines, and interstate highways—because logistics efficiency tends to keep a building relevant.

From the tenant’s side, the pitch is straightforward: keep control of a strategic facility, unlock capital, and deploy that capital into the core business instead of tying it up in owned real estate. The sale-leaseback is as much a financing decision as it is a real estate one.

For investors, the REIT structure translates that rent stream into dividends. Broadstone has maintained a dividend payout ratio of around 80% of Adjusted Funds From Operations and has offered a dividend yield around 6.3%. With a diversified portfolio that’s increasingly industrial and a long-duration lease base, the value proposition is steady income backed by contracted rent.

But the risks are real, and they’re concentrated. A triple-net REIT’s performance is largely a function of tenant credit. If a tenant can’t pay—or goes bankrupt—the REIT can lose income and the property’s value can drop, especially if the building is specialized or hard to re-lease.

And like all REITs, net lease companies are sensitive to interest rates. When rates rise, the relative appeal of dividend yields changes, and the cost of capital can tighten—both of which can pressure REIT valuations and slow acquisition economics.

Still, this is why the model has endured: long-term net leases can deliver a rare combination of stability and transparency. If you’re looking for durable earnings streams over long periods, triple-net is about as close as real estate gets to predictable.

IX. Leadership & Culture: The People Behind the Pivot

Broadstone’s evolution is, at its core, a people story. The company was founded in 2007 by Amy Tait, then Chairman, who brought with her something unusually valuable in private real estate: lived experience running a public REIT. She had been a veteran of Home Properties Inc., the multifamily REIT that was ultimately acquired in 2015 by an affiliate of Lone Star Funds.

That background shaped how Broadstone operated long before it ever traded under a ticker symbol. As Chris Czarnecki put it, “We sourced our capital privately for 13-plus years before going public and continued to grow the portfolio, but we always had a public company mentality by virtue of Amy's guidance and experience in the public-company space.”

That “public company mentality” mattered more than it sounds like. While still private, Broadstone built institutional-grade financial reporting, compliance, and underwriting processes—the kind of infrastructure most companies scramble to assemble right before an IPO. So when the window finally opened, Broadstone wasn’t trying to become a public company overnight. It had already been acting like one.

Tait’s own training reinforced that culture. She graduated from Princeton in 1980 with a BSE in Civil Engineering (cum laude) and later earned an MBA from the University of Rochester’s Simon School. Engineering tends to reward systems thinking and precision, and that showed up in Broadstone’s internal DNA: steady, analytical, and allergic to unnecessary risk.

Her leadership was also recognized outside the company, including the Susan B. Anthony Promise Award in 2010, the Simon School Distinguished Alumna Award in 2012, and induction into the Rochester Business Hall of Fame in 2016.

After 15 years with Broadstone Net Lease, Tait stepped down as Chairman of the Board in May 2021. The board appointed Laurie A. Hawkes, previously BNL’s Lead Independent Director, as Chairman.

What’s notable is how much continuity Broadstone maintained through the transition. John Moragne, who later became CEO, had worked with or for the company since its inception, across roles that put him at the center of both governance and execution. That history—deep familiarity with operations, investment strategy, and corporate decision-making—gave the board a leader who didn’t need to “learn” Broadstone. He helped build it.

Moragne also brought a particular edge that fits Broadstone’s style: legal and transactional fluency. He previously served as a Partner at Vaisey Nicholson & Nearpass, a law firm focused on complex real estate, finance, corporate, and transactional matters. Combined with his operational experience as general counsel, chief operating officer, and then CEO, it added up to a leadership profile built for structured decision-making: evaluate risk, structure the deal right, and avoid the kind of surprises that blow up a REIT’s long-term compounding.

That discipline shows up in how Broadstone describes its growth engine. The REIT expects to grow revenues and earnings through four building blocks: (1) embedded same store net operating income growth driven by portfolio rent escalations, stable rent collections, minimal credit losses, strong lease rollover outcomes, and accretive recycling; (2) revenue generating capital expenditures with existing tenants; (3) build-to-suit developments; and (4) a diversified acquisition pipeline.

Moragne framed the moment simply: “We are entering 2026 with strong momentum and a clear runway ahead. Our disciplined execution, combined with the strength and depth of our build-to-suit pipeline, gives us confidence in our ability to deliver on our AFFO growth targets for both 2025 and 2026, despite recent tenant related headlines.”

X. Strategic Analysis: Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers

To see where Broadstone really sits, you have to zoom out in two directions at once: first, to the structure of the net lease industry, and second, to what—if anything—can become a durable edge in a business that, from a distance, looks like “buy buildings, collect rent.”

Porter’s 5 Forces Analysis:

Threat of New Entrants (Medium): In theory, net lease has a low barrier to entry. The REIT structure is well understood, and anyone who can raise capital and follow the rules can show up and start buying properties. In practice, the hard part is competing over time. Incumbents benefit from scale in cost of capital, deep relationships with tenants and brokers, and a track record that makes capital easier to raise. You can launch a new net lease platform quickly; you can’t manufacture the credibility that lets you consistently win good deals against players like Realty Income—or against a Broadstone that has spent years building repeatable sourcing and underwriting.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers (Low): Sellers are fragmented. There are thousands of potential net lease transactions, and owners have all kinds of motivations—liquidity, portfolio cleanup, recapitalizations. Even though bidding can get crowded for top-tier assets, the overall universe of properties is broad enough that a disciplined buyer can stay selective.

Bargaining Power of Buyers/Tenants (Medium-High): The best tenants have options. They can run a competitive process among multiple net lease landlords, they can finance the property themselves, or they can just keep owning it. That means landlords compete not only on price, but also on certainty of close, speed, and the ability to structure transactions that actually solve a tenant’s problem.

Threat of Substitutes (Medium): A sale-leaseback is only one way to raise capital. Traditional mortgages, banks, private equity, and other financing solutions can all compete. Net lease wins when its advantages—speed, flexibility, and the ability to unlock capital while keeping operational control—outweigh the perceived cost of committing to a long lease.

Competitive Rivalry (High): This is the big one. Net lease is crowded, and the “good” deals tend to attract everyone at once: Realty Income, Agree, NNN, NETSTREIT, and plenty of private and institutional capital. When multiple buyers can fund similar transactions, competition shows up where it always shows up in real estate: pricing. Cap rates compress, spreads tighten, and the only way to avoid overpaying is either (1) having a lower cost of capital, (2) finding proprietary deal flow, or (3) having the discipline to walk away.

Hamilton’s 7 Powers Analysis:

Scale Economies (Moderate): Size matters because it lowers the cost of capital. Cheaper equity and cheaper debt translate directly into the ability to pay more for the same building and still make the math work. Broadstone’s scale helps compared to smaller competitors, but it can’t match the advantage of the biggest players, especially Realty Income.

Network Effects (None): Owning more properties doesn’t make Broadstone’s next property inherently more valuable. This isn’t a platform business where each additional user strengthens the system.

Counter-Positioning (Weak but Present): Broadstone’s quality-first posture does create a form of counter-positioning versus yield-chasing strategies. If a REIT has trained its investors to expect a higher dividend supported by higher-risk assets, pivoting to “lower yield, higher quality” can be painful in the short term—exactly the kind of change many management teams avoid.

Switching Costs (Moderate): During a 10- to 15-year lease, tenants aren’t “switching” landlords. That’s the whole point of the model: contracted cash flows and stability. The real test comes at lease rollover, when switching costs fall and the real estate has to stand on its own.

Branding (Weak): Broadstone has brand value where it matters—in the small world of sophisticated operators, brokers, and advisors who care about certainty of execution. But it’s not consumer-facing, and the brand doesn’t carry the same gravitational pull as the sector’s household names.

Cornered Resource (Weak): Proprietary sourcing and tenant relationships help, but they’re not exclusive. Competitors can build their own networks, and capital is abundant. These advantages differentiate, but they don’t lock the door behind Broadstone.

Process Power (Moderate): This is where Broadstone’s story actually shows up as an advantage. Underwriting discipline, portfolio management, and capital allocation judgment—built and reinforced over nearly two decades—create a repeatable process that’s hard to copy quickly. In net lease, culture is part of the product: the ability to say “no,” to avoid the tempting high-yield deal, and to keep the balance sheet intact even when the market is pushing you to stretch.

Synthesis: Broadstone doesn’t have a classic, structural moat. Its edge is more practical: quality, discipline, and balance sheet flexibility, applied consistently over time. And the biggest proof point is the transformation itself—the ability to move from a broad, diversified net lease platform to an industrial-weighted portfolio, and to simplify away property types that created friction. Many competitors can describe that strategy. Far fewer can execute it without getting trapped by their own legacy portfolios.

XI. Bull vs. Bear Case & Future Outlook

Bull Case:

The optimistic view on Broadstone starts with a simple claim: the heavy lifting is largely done. By year-end 2024, the company had substantially completed its healthcare simplification, taking clinical and surgical assets down to 3.2% of annualized base rent. It also refreshed how it talks about itself—updating its core reporting categories to industrial, retail, and other—so the story investors see matches the portfolio Broadstone actually wants to compound.

From there, the bull case leans on the industrial bet. Broadstone’s roughly 60% industrial allocation puts it in the slipstream of long-running demand drivers: e-commerce logistics, supply chain reconfiguration, and last-mile delivery. The key is that Broadstone isn’t making an “industrial at all costs” wager. It’s pairing that tilt with tenant and geographic diversification, which is exactly how you try to capture tailwinds without turning the whole company into a one-theme trade.

Growth is the next pillar. Broadstone’s build-to-suit pipeline gives it a path to add high-quality properties without living and dying by the most competitive, brokered acquisition processes. Management has reaffirmed that build-to-suit activity, paired with roughly 2% average rent escalators, is meant to be the engine behind consistent 4% annual AFFO growth.

Then there’s the balance sheet, which functions like an option. In 2024, Broadstone maintained an investment-grade profile, low leverage around 5.0x, and ample liquidity—giving it the ability to act when opportunities open up and other buyers get constrained.

Finally, there’s valuation. Broadstone has traded at roughly a two-turn AFFO multiple discount to the sector average, which some analysts view as more pessimism than the portfolio deserves—implying room for multiple expansion if execution stays clean.

On Street sentiment, three analysts have issued hold ratings and eight have issued buy ratings. The average one-year price target among those covering the stock is $20.10.

Bear Case:

The bearish view is less about “what Broadstone is doing wrong” and more about what the market and the business model can do to any net lease REIT.

First, scale is real. In a crowded asset class, bigger players—especially Realty Income—often win deals simply because their cost of capital lets them pay a price smaller REITs can’t justify. Broadstone’s edge has to be selectivity and sourcing, not brute force.

Second, interest rates. Net lease REITs can execute perfectly and still see their valuations compress if rates stay elevated or move higher. Even when fundamentals hold up, the market can re-rate the entire group.

Third, leverage discipline matters. Broadstone has been around 5.2x net debt, and management has signaled comfort going as high as 6x. That’s not inherently reckless, but it does shrink the margin for error if the economy softens or credit issues emerge.

Fourth, industrial could cool. If supply catches up, if demand slows, or if cap rates expand, property values can come under pressure—even for well-located buildings with good tenants.

And lastly, the dividend trade-off cuts both ways. Broadstone’s yield is lower than some peers, which can limit its appeal to investors who want the highest current income and are less interested in quality-driven compounding.

Key Performance Indicators to Monitor:

For investors tracking Broadstone, two metrics are especially telling:

-

AFFO Per Share Growth: This is the cleanest scoreboard for whether the strategy is working—organic escalators plus external growth, net of financing costs. Management has targeted 4% annual growth. Hitting that consistently is what turns the “quality thesis” into actual per-share compounding.

-

Rent Collection Rate: In net lease, everything flows from tenants paying rent. Broadstone’s history of 99%+ collection is a signal of tenant quality and underwriting discipline. Any sustained drop would be an early warning that credit stress is moving from “headline risk” to “cash flow risk.”

XII. Lessons from Broadstone's Journey

The Broadstone story leaves behind a handful of lessons that travel well—whether you’re allocating capital, running a company, or just trying to understand what actually works in a crowded, commoditized business.

Strategic reinvention is possible, but it’s rarely fast. Broadstone didn’t “pivot” in a quarter. It rebuilt itself over years, property by property, tenant by tenant. And it did it with an unusual constraint: it couldn’t torch the portfolio to start over. Selling too aggressively would have forced ugly losses and made it harder to replace assets with the right kind of quality. So the company took the slower path—less dramatic, more disciplined—and let the transformation compound instead of trying to force it.

Quality really does compound—especially when the world stops being friendly. Broadstone repeatedly chose slightly lower initial yields in exchange for better tenants and better real estate. In calm markets, that can look like leaving money on the table. But then came the real tests: the post-crisis retail unwind, COVID, and then the rate shock. And in those moments, portfolio quality stopped being an abstract concept and started being the difference between “collecting rent” and “explaining why you can’t.”

Balance sheet conservatism isn’t boring. It’s optionality. Keeping leverage around 5.0x didn’t just reduce risk—it preserved the ability to act. When markets dislocate, the best deals usually go to whoever can move with certainty. A more levered competitor might look great in a smooth environment, but the minute conditions tighten, they can lose the one thing that matters most in real estate: flexibility.

Culture can be strategy. Broadstone’s family-business roots weren’t a branding detail; they helped shape how the company behaved. The Leenhouts family brought a long view and an instinct for cycle survival—analytical rigor, caution around leverage, and a bias toward durability over flash. Plenty of family businesses never institutionalize those traits. Broadstone did, and it shows in the decisions that defined the last decade.

And finally: in net lease, you don’t have to be the biggest—you have to be right more often than you’re wrong. Broadstone can’t outscale Realty Income, and it isn’t trying to. Its version of edge is selectivity: underwriting discipline, tenant credit focus, proprietary sourcing through build-to-suit, and the willingness to walk away when pricing gets stupid. In a market where everyone has capital, “no” becomes a competitive advantage.

"With a well-positioned balance sheet, a differentiated growth strategy centered around our core building blocks, and a robust and expanding relationship network, we believe Broadstone is uniquely positioned for long-term value creation."

The story, of course, isn’t finished. The healthcare exit is largely in the rearview mirror. The industrial tilt is now the center of gravity. The build-to-suit pipeline is meant to be the next growth leg. And the balance sheet is set up to play offense when others can’t.

Whether Broadstone delivers from here will come down to execution—keeping underwriting tight, keeping the portfolio relevant, and keeping growth accretive at the per-share level. But the foundation it spent years building looks exactly like what a long-term net lease compounder is supposed to look like.

For investors, Broadstone offers a straightforward bet: disciplined management plus a higher-quality portfolio, potentially at a valuation that still reflects “small and underfollowed” more than “clean and durable.” For students of strategy, it’s a reminder that even in a mature industry, you can still create value—not with a bold announcement, but with a decade of consistent, correctly aligned decisions.

XIII. Further Reading & Resources

Top 10 Long-Form Resources:

- Broadstone Net Lease SEC Filings (10-Ks, 10-Qs, proxy statements) - The primary source for the company’s financial history, risk disclosures, and how management explains the strategy in its own words

- "The Intelligent REIT Investor" by Stephanie Krewson-Kelly & R. Brad Thomas - A strong grounding in REIT fundamentals, with useful context for how net lease economics work in practice

- NAREIT Net Lease REIT Research - Clear, industry-level explanations of the net lease model, REIT structure, and sector trends

- Green Street Advisors REIT Research Reports - Institutional-quality commentary on valuations, portfolio quality, and sector dynamics

- Broadstone Investor Presentations (available on IR website) - The cleanest view of what Broadstone wants investors to focus on: portfolio mix, underwriting posture, and capital allocation priorities

- "Sale-Leaseback Transactions: A Practical Guide" - A helpful lens on why tenants choose sale-leasebacks, and what they negotiate for in net lease deals

- Bloomberg/S&P Capital IQ data on REIT sector - Fast comparisons across peers: multiples, balance sheet metrics, and historical performance

- Conference call transcripts (2020-present via Seeking Alpha) - Where the strategy meets reality: leasing updates, credit issues, dispositions, and what management emphasizes quarter to quarter

- CoStar/Real Capital Analytics data - Transaction data that helps you track cap rates, pricing, and where competition is heating up or cooling off

- NAREIT industry presentations and conferences - Useful for the broader backdrop: how net lease fits into public real estate, and what the sector is collectively worried about (or excited about) at any given moment

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music