Badger Meter: The "Intel" of the Water Grid

I. Introduction: The Quiet Compounder

Picture the water grid the way it actually is: miles of aging pipe, buried and out of sight, carrying treated water from a plant to your kitchen tap. Somewhere along the way, a shocking amount of it never makes it. It leaks into the soil through cracked mains, slips out at corroded joints, or simply goes unmeasured and unbilled. Globally, that “non-revenue water” is estimated at roughly 126 billion cubic meters a year—about $39 billion of value, literally seeping away. It’s one of the biggest, least glamorous inefficiencies in modern infrastructure.

And it’s exactly the kind of problem Badger Meter was built to solve—because Badger sits at the one place you can’t hand-wave your way around: the measurement point.

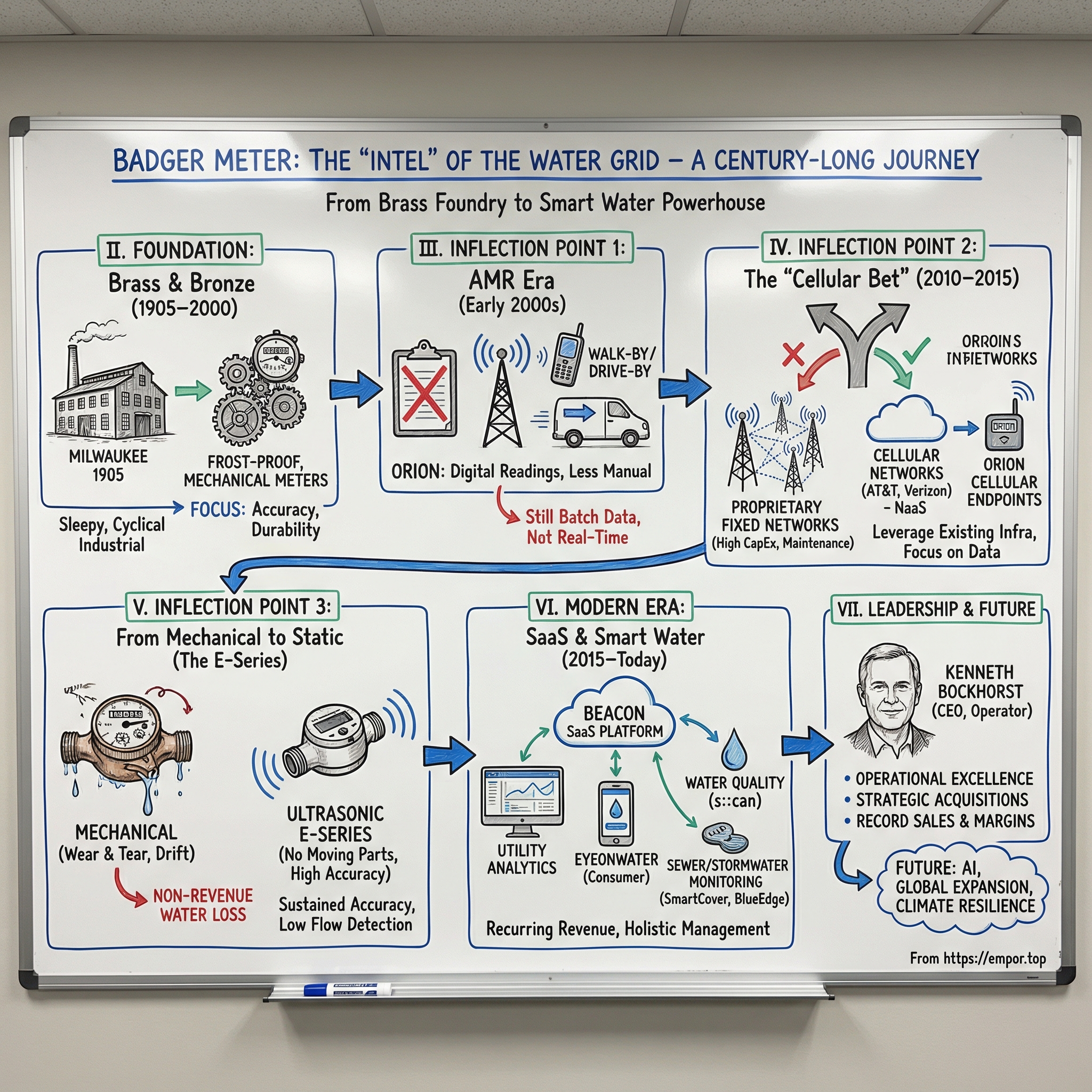

Badger Meter doesn’t get mentioned in the same breath as Tesla, NVIDIA, or whatever mega-cap is dominating the news cycle. It’s a Milwaukee company founded in 1905, and today it’s worth about $5.18 billion. But the performance tells its own story. Over the last several years, this “boring” industrial name has compounded like a tech winner—up more than 500% over the past seven years.

So how does a company that started by making frost-proof meters for Midwestern winters turn into a digital water management business approaching a billion dollars in annual revenue? By 2024, revenue was about $0.827 billion, and over the twelve months ending September 30, 2025, it reached about $0.901 billion.

The real answer, though, isn’t in the revenue line. It’s in the choices. Badger didn’t just survive the shift from mechanical hardware to digital systems—it leaned into it early. When the industry’s giants spent fortunes building proprietary radio networks, Badger made a contrarian bet: don’t become a telecom company. Ride the cellular networks the world was already paying trillions to build. And while competitors argued over whether software belonged in the meter business at all, Badger built a cloud platform that made the meter the beginning of the relationship, not the end.

That’s the whole thesis in one line: Badger Meter isn’t selling brass hardware anymore—it’s selling data and accountability. The company has become a North American leader in smart water solutions across utility, commercial, and industrial markets, with meters, valves, sensors, and software that turn invisible infrastructure into something you can actually monitor and manage.

If you want a playbook for how an “Old Economy” manufacturer digitizes itself without losing what made it trusted in the first place—and without betting the company on the wrong kind of innovation—this is it. Let’s trace the journey from brass foundry to smart water powerhouse.

II. The "Brass & Bronze" Era: A Century of Flow (1905–2000)

Badger Meter’s story starts on March 8, 1905, in a Milwaukee machine shop, when four local businessmen signed the papers to form the Badger Meter Manufacturing Company. The original mission wasn’t lofty. It was intensely practical: build frost-proof water meters for Midwestern homes.

That first breakthrough was beautifully simple. Wisconsin winters froze water inside pipes and meters, cracking housings and ruining the measuring mechanism. Badger’s solution was a meter with a soft, replaceable cast-iron bottom plate designed to rupture when the meter froze. The plate would fail on purpose, relieving pressure and protecting the parts that actually mattered. It was an early glimpse of a theme that would show up again and again in Badger’s history: win by solving the unglamorous problem better than anyone else.

The early years were scrappy and hands-on. By 1910, Badger was selling roughly 3,700 meters a year at about eight dollars each. Cofounder John Leach—now running the company—operated out of a two-story shop in downtown Milwaukee under the motto “Accuracy Durability Simplicity Capacity.” Badger had just a dozen employees, so when a big order landed—say 200 meters or more—the whole company worked weekends. They’d break for a lunchtime pail of beer and, after the day’s work, Leach would pick up the tab for dinner.

In 1919, Badger took a major step up the industrial food chain: it opened its first foundry and moved into a new facility that could cast its own metal components. That shifted Badger from a small shop assembling parts to an integrated manufacturer. It also meant the company could do job shop work for other Milwaukee manufacturers, building capability and cash flow beyond its own meter line.

Management changed hands in 1924, when Charles Wright replaced Leach as president. Wright would run Badger for the next three decades, and the family’s influence would stretch even longer. When Charles died in 1952, his son James Wright took over—and pushed Badger into a new chapter: diversification.

By the mid-century, Badger wasn’t just a water meter company anymore. In 1954, it acquired Precision Products of Oklahoma, which made detonating mechanisms for the oil industry and timing components for parking meters and other instruments. Three years later, it bought Milwaukee’s Counter and Control Corporation, a producer of electromechanical devices that counted shaft revolutions, lever strokes, and electrical impulses. The strategy reshaped the business. By 1975, more than half of Badger’s profits came from products other than residential water meters—something that would have been unthinkable in the company’s early decades.

But here’s the twist: even with all that activity, by the late 1990s the core meter business had become a commoditized replacement game. Utilities bought meters for new housing developments, or they replaced old ones after 20 or 30 years in the ground. Growth followed housing starts. Badger’s results rose and fell with construction cycles, not because the company had found a new way to create value.

And the customer made it even harder to change the trajectory. Municipal water utility managers are among the most risk-averse buyers anywhere. They keep equipment for decades, buy through slow and bureaucratic processes, and treat novelty like a liability. Selling something new can take years of relationship-building, pilots, and persistence.

For a long time, that dynamic quietly punished innovation. If your customers were happy installing the same mechanical meters their predecessors used, why swing hard on new technology? Through the 1990s, Badger looked like what it was: a steady franchise, but a sleepy, cyclical industrial company with limited upside.

What almost nobody anticipated was that the next era wouldn’t erase Badger’s legacy. It would weaponize it—turning a century of trust at the measurement point into a platform for something far more valuable than brass and bronze.

III. Inflection Point 1: No More Clipboards (The AMR Era)

Imagine the job of a meter reader in 1985. Clipboard in hand, uniform on, walking block to block through residential neighborhoods. Lift a manhole cover. Squint at a dial in a muddy meter pit. Write down the numbers. Move to the next house.

It was slow, expensive, and unreliable. Dogs lunged. Homeowners complained. Gates were locked. Snow and rain turned “read day” into a slog for months at a time. But utilities put up with it for a simple reason: there wasn’t another way. The meters produced the data, and the only way to get the data was to physically visit each meter.

Automatic Meter Reading—AMR—changed that. Not overnight, but unmistakably. For the first time, the measurement point could talk.

The idea was simple: add a small radio transmitter so the meter could broadcast its reading when a receiver came near. Early systems were “walk-by,” where a technician with a handheld unit could collect reads through walls and pit covers without stopping at each home. Then came “drive-by,” where a van with antennas could cruise through neighborhoods and pick up readings at street speed.

Badger’s entry into this world was ORION. Beginning in the early 2000s, the ORION product family enabled utilities to capture interval data and meter readings using one-way and two-way communications—bringing what Badger describes as Advanced Metering Analytics (AMA) into the mainstream of its offering. More important than the acronym was what ORION represented strategically: Badger could see that the value in a water meter was starting to migrate away from the brass chamber—the physical measuring component—and toward the register—the electronics, the radio, the digital interface.

AMR was a real improvement. It cut operating costs, improved billing accuracy, and freed up people who had been spending their days collecting numbers. And compared to the old method—either sending a person to each home or sending a truck to sweep a territory with radio sensors—it produced more data with far less friction.

But it still had a ceiling. Drive-by AMR was better than clipboards, yet it was still a batch process. You got a reading when the van came by—often monthly. If a pipe burst the day after the route ran, that leak could gush for weeks before the next read exposed the spike. AMR solved billing efficiency. It didn’t solve water loss.

That was the tension building underneath the whole industry. Utilities didn’t just need faster reads. They needed visibility. Continuous monitoring, not improved paperwork.

For Badger, this era became a proving ground. ORION forced the organization to get good at electronics, integration, and long-lived field support—and just as crucially, it taught Badger how to sell technology to the most change-averse customer base in the economy. They’d made the first transition successfully, from purely mechanical devices to digital-enabled metering.

And that mattered, because the next transition wouldn’t be incremental. It would require a conviction call—one that went directly against the path the biggest competitors were taking.

IV. Inflection Point 2: The "Cellular Bet" (2010–2015)

By 2010, the water industry had reached the obvious conclusion: once-a-month AMR reads weren’t enough. The future was AMI—Advanced Metering Infrastructure—where meters didn’t just report usage for billing, they streamed frequent, near real-time data back to the utility. Leaks. Backflow. Continuous visibility. The only question was the one that would define the next decade: what network would carry all that data?

The largest players made a big, expensive choice. Companies like Itron and Sensus poured billions into proprietary fixed networks—private radio towers and mesh networks spread across cities. In North America, proprietary RF networking platforms went on to dominate AMI, accounting for as much as 91% of the installed base of AMI endpoints in 2024.

At the time, the logic sounded airtight. Utilities already owned pipes, pumps, and plants. Why not own the communications layer too? A fixed network offered control, predictable performance, and the ability to tailor the system to local needs.

Badger looked at that same fork in the road and went the other way.

Instead of becoming a network builder, Badger bet on cellular. The premise was simple but gutsy: as the world poured money into national mobile networks, cellular would get cheap enough and power-efficient enough to make sense inside a meter pit. That became the foundation for ORION Cellular endpoints—Badger’s evolution of AMI built around a Network as a Service (NaaS) approach, using existing cellular infrastructure for secure, two-way communication of high-resolution meter data.

The economic argument was hard to ignore. AT&T and Verizon had already spent hundreds of billions building and maintaining networks that reached essentially everywhere people lived. They ran them with massive engineering teams, enterprise-grade security, and constant upgrades—investments a water utility could never justify, and a meter manufacturer would be foolish to try to replicate. With Badger’s approach, AMI meant utilities didn’t need to install and maintain their own communications infrastructure. Through partnerships with AT&T and Verizon, Badger devices could transmit over 4G and LTE networks, reducing downtime risk and eliminating the need for utility-owned gateway infrastructure, plus the installation and ongoing maintenance that came with it.

And crucially, the timing lined up. Badger’s cellular push arrived as LTE-M and NB-IoT matured—cellular standards designed for IoT: low power, long battery life, and built for small bursts of data on a predictable schedule. In other words: perfect for meters.

As the years played out, the competitive implications got sharper. Cities that had invested in proprietary networks discovered they’d also signed up for a second job: running a telecom system. Towers needed maintenance. Technology changed. Upgrades were expensive and disruptive. None of that helped deliver clean water.

Badger’s cellular customers didn’t have to manage any of it. They installed endpoints and relied on the carriers to run the network. The meter behaved more like a smartphone: it connected to infrastructure that already existed, and the utility didn’t need a specialized communications team to keep readings flowing.

“With the release of BEACON SaaS, Badger Meter also becomes the first major water meter company to release a cost-effective cellular based solution for system wide deployment. Utility managers across the country have told us that while they are experts at running their water utilities, they aren't as comfortable with managing communications network infrastructure.”

By the time AMI became a mainstream mandate, Badger’s position was clear. In North America, the top five AMI endpoint vendors by installed base were Sensus, Badger Meter, Itron, Aclara (Hubbell), and Neptune Technology Group (Roper Technologies). Badger was smaller than several of these competitors—but the cellular bet helped it run right alongside them.

The lesson is broader than water meters. Sometimes the best strategy isn’t building the infrastructure yourself. It’s choosing the platform with better unit economics than you could ever achieve, and designing your product around it. Badger effectively outsourced the most capital-intensive part of AMI to companies with trillion-dollar balance sheets—and kept its focus on what actually created customer value: the measurement point, the data, and what you can do with it.

V. Inflection Point 3: From Mechanical to Static (The E-Series)

Walk into a water treatment plant and ask an engineer about the difference between mechanical and ultrasonic meters. If they’ve spent enough years living with the old world of spinning parts, you’ll see it immediately: this is the kind of change they’ve been waiting for.

For most of Badger Meter’s history, “measuring water” meant mechanical meters—the nutating disc design and its cousins. Water flows through the meter, physically moves a disc or turbine, and that movement gets translated into a reading. It’s proven. It’s familiar. It worked for a century.

It also comes with an unavoidable truth: moving parts wear out.

As mechanical meters age, they start to drift. Bearings develop friction. Discs get sluggish. The meter under-registers the real flow going through it. On paper, that’s “accuracy degradation.” In the real world, it’s water being delivered, treated, pumped, and paid for by the utility… but not billed to the customer. That gap feeds non-revenue water, and it quietly compounds across thousands of connections for years.

Mechanical meters have another weakness that matters even more in a world obsessed with leaks: low flow. The slow drip. The tiny, constant leak that doesn’t look like a crisis—until you add it up over months.

Ultrasonic meters change the physics of the problem. Badger’s E-Series Ultrasonic meters measure flow with high-frequency sound waves. Instead of relying on a disc to spin, the meter sends ultrasonic signals with and against the flow of water and calculates velocity by measuring the time difference between those signals. It’s closer to sonar than it is to a traditional meter: you don’t touch the water with moving parts; you “listen” through it.

The payoff is exactly what utilities want and mechanical systems struggle to deliver: sustained accuracy over time, extended low-flow measurement, and reliability without the wear-and-tear curve. No moving parts means no mechanical degradation. And because ultrasonic technology can see tiny flows that mechanical meters often miss, it can detect the drip—turning what used to be invisible loss into measurable, actionable data.

For a city, that becomes a straightforward business case. Yes, an ultrasonic meter costs more up front. But if it starts capturing usage that previously slipped through unmeasured, it can pay for itself by recovering revenue the utility was already spending money to produce.

This wasn’t just a product upgrade. It forced a manufacturing identity change inside Badger. A company that had grown up casting bronze components in a foundry had to build capability for precision electronics and sensor assembly—clean-room facilities, electronic component sourcing, and quality systems that look a lot more like modern device manufacturing than old-school metalwork.

The E-Series meters were also built to match utility reality: long deployment cycles. They were designed for a roughly 20-year service life, aligned with how long utilities expect equipment to stay in the ground. Power mattered too. The battery is fully encapsulated within the register housing, not replaceable, and engineered for long life so the meter can do its job for years without intervention.

And then comes the strategic layering. On its own, an ultrasonic meter is a better measurement tool. Inside Badger’s ecosystem—paired with ORION endpoints and BEACON SaaS—it becomes a node on a network. In the E-Series Ultrasonic Plus configuration, that connection can even enable utilities to temporarily restrict water service remotely, without rolling a truck.

Zoom out and you can see why this mattered so much. The cellular bet changed how data got out of the ground. The E-Series changed what the measurement point could do in the first place. Badger wasn’t just adding connectivity to an old mechanical box. It was remaking the box into a solid-state sensor platform—and in doing so, crossing one of the hardest chasms in industrial tech: from mechanical to digital without losing the trust of conservative, long-cycle customers.

VI. The Modern Era: SaaS and "Smart Water" (2015–Today)

By the mid-2010s, Badger had done the hard physical work. Ultrasonic meters could measure with far more fidelity. Cellular endpoints could move that data out of pits and basements in regular intervals. But a utility doesn’t win just because it has more readings. It wins when those readings turn into action: find leaks faster, reduce complaints, recover revenue, and prove performance to regulators and city councils.

That’s where Badger’s most important evolution kicked in: it stopped being just a meter company and started becoming a software platform.

The BEACON Software as a Service (SaaS) solution combines the intuitive power of BEACON software suite with proven ORION Cellular Network as a Service (NaaS), Traditional Fixed Network (AMI) and Mobile (AMR) meter reading technologies to provide utility management with greater visibility, control and optimized information.

In plain terms, BEACON was Badger’s “App Store moment.” It was the layer that made every endpoint and every meter dramatically more valuable. Instead of dumping data into a spreadsheet, utilities got a living system: dashboards that could be tailored to what mattered locally, alerts that could be tuned to specific conditions, a secure hosted platform, and integrations into existing utility business systems. The pitch wasn’t “more data.” It was faster leak detection, cleaner revenue management, easier compliance reporting, and customer service that didn’t require guesswork.

And BEACON didn’t stop at city hall. The consumer-facing piece—EyeOnWater—pushed the platform all the way into people’s kitchens and laundry rooms. It’s a web portal and smartphone app that lets customers see their own water consumption and, crucially, see it at much tighter time intervals: 15-minute, hourly, daily, monthly, yearly. That meant homeowners could spot abnormal usage patterns, get leak alerts, and fix small issues before they turned into major water damage—or a brutal bill.

That software layer also changed Badger’s economics. A meter sale is episodic. A utility might touch that meter again in 20 years. BEACON turned the relationship into something ongoing: a recurring SaaS revenue stream that grew as more endpoints went into the ground. As adoption of ORION Cellular and BEACON increased, software revenue grew to more than $56 million in 2024, representing a 28% CAGR over five years.

By 2024, SaaS revenue reached 6.7% of sales, and it was still climbing. Software sales exceeded $56 million in 2024, up about 30% year over year. For a company that began in a foundry, this was a genuine financial profile shift: more recurring revenue, better visibility, and deeper customer stickiness.

Then Badger widened the lens. Once you’ve built a platform around “what happened to water,” the obvious next question is, “what condition is the water in—and what condition are the pipes in?” That’s where M&A came in.

In November 2020, Badger acquired s::can, a Vienna-based company specializing in water quality monitoring. Badger Meter acquired s::can GmbH and subsidiaries, a privately-held provider of water quality monitoring systems for a cash purchase price of €27 million. Founded in 1999 with headquarters in Vienna, Austria, s::can specializes in optical water quality sensing solutions that provide real-time measurement of a variety of parameters in water and wastewater utilizing in-line monitoring systems.

The strategic logic was straightforward. CEO Kenneth Bockhorst said, "Water quality is a growing concern across the globe. We believe adding s::can and their expertise in real-time water quality monitoring to the trusted Badger Meter portfolio is of tremendous strategic value to our customers. Just as water utility billing moved from manual reads to Advanced Metering Infrastructure (AMI), water quality monitoring is moving from lab sample testing to online, real-time collection, monitoring and reporting."

Badger’s ambition was now expanding from “How much water?” to “Is the water clean?” Quantity to quality.

Then came the biggest move yet. With the acquisition of SmartCover, Badger Meter strengthens its offering of BlueEdge solutions within collection system monitoring applications. Badger Meter announced the acquisition of SmartCover Systems from XPV Water Partners for $185 million.

Funded with available cash, the deal added a new category of visibility: real-time monitoring of water collection systems, with a focus on sewer lines and lift stations. It also broadened BlueEdge beyond the clean-water distribution side into the messier, more failure-prone wastewater world. SmartCover, with approximately $35 million in annual revenue, provides sensors, software and related services that monitor sewer levels around the clock, detect pattern changes, and automatically alert utilities before small issues become overflows, fines, or emergency call-outs.

The acquisition also pushed Badger into stormwater management. Bockhorst noted that "SmartCover is the market leader in the fast-growing stormwater management space, which is in the very early stages of adoption in North America and other regional markets in which we operate."

The $184 million SmartCover acquisition positions BMI at the forefront of a virtually greenfield sewer monitoring market with less than 0.5% digital adoption, offering outsized growth potential and margin accretion as the business scales within the BlueEdge ecosystem.

By 2024, Badger pulled these threads under one name: BlueEdge. Badger introduced BlueEdge, the platform brand aimed at simplifying the Badger Meter suite of scalable solutions for efficient water management. The branding was more than marketing. It was a signal that Badger no longer wanted to be perceived as “a meter vendor,” or even “a smart meter vendor,” but as a full-stack digital water management platform.

For investors, this modern Badger Meter didn’t look much like the cyclical industrial of the 1990s. The business primarily splits into two segments: Utility Water, which accounts for approximately 88% of net sales, and Flow Instrumentation, which makes up about 12%. The company has worked its way from a capital equipment manufacturer into a business with an expanding base of software and services—more recurring revenue, higher margins, and stronger switching costs as utilities embed Badger’s data streams and workflows into their operations.

VII. Leadership: Kenneth Bockhorst and Operational Excellence

A transformation like Badger’s doesn’t happen on strategy decks alone. At some point, someone has to make the calls, keep the organization executing through chaos, and resist the urge to chase shiny objects. For Badger Meter, that steady hand has been Kenneth Bockhorst.

Bockhorst joined Badger in October 2017 as Chief Operating Officer. On January 1, 2019, he became President and Chief Executive Officer, and on January 1, 2020, he added Chairman of the Board. He arrived with more than 20 years of global operations experience—less “visionary founder,” more “operator who can actually land the plane.”

His résumé explains the posture. Before Badger, he spent six years at Actuant Corporation, most recently as executive vice president of its energy segment. Earlier, he held product management and operational leadership roles at IDEX Corporation and Eaton Corporation. In other words: industrial businesses, complex supply chains, and customers who don’t tolerate mistakes.

That background mattered, because the world didn’t exactly hand him ideal conditions. In the years that followed, Badger had to navigate COVID, supply chain disruption, inflation, and the uncertainty of tariffs and geopolitics—all while continuing to shift the business toward higher-tech, higher-expectation products and services.

Operational discipline shows up in outcomes. In 2024, Badger Meter posted record net sales of $826.6 million, up 18% from $703.6 million in 2023.

The leadership transition that put Bockhorst in the role was also handled deliberately. Richard A. Meeusen—who joined Badger in 1995, became President and CEO in 2002, and Chairman in 2004—stepped out of the CEO seat at the end of 2018. He remained Chairman through 2019, then retired on December 31, 2019, clearing the way for Bockhorst to take over the board on January 1, 2020.

Bockhorst’s management philosophy is refreshingly direct. “I cringe when I hear someone say, ‘Fake it until you make it.’ That is the worst career strategy or advice I think I’ve ever heard. Be humble, work hard, and learn from those around you, or you will quite possibly, ‘Fake it until you get fired.’”

That mindset fits Badger: build credibility the slow way, keep promises, and compound.

Financially, the company’s execution under Bockhorst has been strong. In 2024, Badger delivered 18% year-over-year sales growth and reached record operating profit margins of 19.1%, driven by both gross margin expansion and SEA leverage—an improvement of 230 basis points year over year.

Zoom out further and you see the bigger signal: the business has been converting strategy into returns. Badger Meter’s five-year average ROIC was 25.3%, putting it in rare company among industrials—and reinforcing that this wasn’t just a technology pivot. It was an operational one, executed with the kind of discipline that turns a century-old manufacturer into a modern compounder.

VIII. The Playbook: Lessons for Builders and Investors

Badger Meter’s transformation is a case study in how an “Old Economy” company can cross a technology chasm without breaking what made it valuable in the first place. There are a few lessons here that travel well—whether you’re building a business in an adjacent industry or trying to spot the next quiet compounder hiding in plain sight.

Don't Reinvent the Infrastructure. Badger’s cellular bet is the cleanest expression of a principle most companies learn too late: don’t build the platform if someone else can run it better, cheaper, and at a scale you’ll never match. While competitors sank enormous capital into proprietary fixed networks, Badger piggybacked on the telecom buildout already happening at a planetary level. The ORION Cellular endpoint is the wedge. It gives utilities two-way data without forcing them to become accidental network operators. No towers to maintain, no mesh to troubleshoot—just a meter that connects like everything else in modern life.

The "Boring" Moat. Google or Amazon could absolutely build a technically superior meter. That’s not the barrier. The barrier is the sales motion. Smart water infrastructure is sold one utility at a time, through procurement cycles that can take years, often ending in a city council vote and a contract that might last decades. And the customer base is wildly fragmented—thousands of municipal utilities across North America, each with its own budget politics and legacy systems. It’s a go-to-market treadmill that software giants generally want nothing to do with, and that “boring” reality functions as a moat.

Hardware as Trojan Horse. In water, you don’t get the data unless you control the measurement point. Badger’s advantage wasn’t that it suddenly became a better software company than everyone else—it was that it already owned trust at the edge of the network. A century of reliable meters got Badger into the ground. Cellular endpoints turned those installs into connected nodes. And once utilities were depending on that stream of readings, BEACON SaaS became the natural next step, not a risky leap.

Pricing Power in Crisis. The harsher the water reality gets, the better the economics of Badger’s solutions look. The International Energy Agency has estimated that roughly a third of water worldwide becomes non-revenue water. In the U.S., estimates often range from about 10% to 30%, and in extreme cases distributors claim losses approaching half. Whether the issue is leaks, under-measurement, or aging infrastructure, the result is the same: utilities pay to treat and move water they never get paid for. When water is plentiful, that’s wasteful. When water is scarce and expensive, it’s intolerable. Badger sells the tools that help utilities find it, prove it, and stop it.

IX. Analysis: Powers, Forces, and Competitive Dynamics

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Supplier power is moderate to high. The modern Badger meter isn’t just brass and bronze anymore—it’s electronics, radios, and increasingly sophisticated sensors. That means Badger depends on semiconductor supply chains it doesn’t control. The recent chip shortage made that painfully clear. Scale helps, but it doesn’t make Badger immune.

Buyer power is moderate. On paper, utilities are large, price-sensitive customers, and the purchasing process is formal and competitive. In reality, once a utility has tens of thousands of endpoints installed, buyer power drops fast. Switching isn’t like changing a software vendor. It’s ripping up a city-wide system, retraining staff, reworking integrations, and risking service interruptions—all to save a few points on unit price.

The threat of new entrants is low. Yes, a well-funded newcomer could build impressive hardware. The real barriers are time and trust. Municipal procurement is built to favor track records, proven reliability, and vendors who will still be around to support equipment a decade from now. Badger has been earning that credibility for more than a century.

The threat of substitutes is very low. You can’t “estimate” water usage the way you might infer electricity use from device-level analytics. Water has to be measured in the pipe, at the edge, in the physical world. There’s no digital workaround for that measurement point.

Competitive rivalry is moderate. The market has several credible players, and at the end of 2024 the top AMI endpoint vendors in North America included Sensus, Badger Meter, Itron, Aclara (Hubbell), and Neptune Technology Group (Roper Technologies). It’s competitive—but Badger’s cellular-first positioning has given it a clear lane, especially for utilities that don’t want to become accidental network operators.

Hamilton Helmer's Seven Powers

Switching costs are the super power. This is the real engine of Badger’s durability. Once a utility standardizes on Badger—meters, endpoints, and BEACON—switching isn’t just a purchasing decision. It’s a multi-year infrastructure swap across an entire service territory, plus retraining teams and migrating years of historical consumption data and workflows. That kind of friction is exactly what shows up in the financials: strong returns, and a business that can keep compounding once it’s embedded.

Cornered resource: the install base. Badger has millions of meters already in the ground across North America. And in this industry, the easiest upgrade path is almost always: keep what’s already there and modernize it. That installed footprint becomes a resource competitors can’t easily replicate—and it creates a natural funnel for endpoints, connectivity, and software.

Scale economies matter too. Ultrasonic metering is a manufacturing game as much as a technology game. As volumes rise, unit costs tend to come down, and the organization gets better at building and supporting these devices at utility-grade reliability. That operational scale helps explain why Badger has been able to grow faster than a typical industrial company in recent years—and do it while staying profitable.

X. Bear vs. Bull: The Investment Thesis

The Bear Case

Valuation Premium. Badger has been priced like a software company even though most of its revenue still comes from hardware. At over 35x earnings and roughly a 3% cash flow yield, you’re not paying for what the business was—you’re paying for what the market believes it becomes. If growth cools, or if the software mix doesn’t expand as expected, that premium can compress fast.

Municipal Budget Dependency. Badger’s customers are local governments, and local governments don’t spend on the same schedule as private enterprise. In a downturn, projects get delayed. Pension obligations pile up. Road repairs and public safety crowd out “invisible” pipe upgrades. Even when the ROI on smart water is real, procurement timelines can stretch, and orders can slip.

Technology Obsolescence. The cellular bet is brilliant—until it isn’t. Badger has leaned hard into LTE-M and cellular endpoints. If 5G, 6G, or some new connectivity standard makes today’s hardware feel dated, the company has to manage the messy reality of long-life equipment in the ground. Backward compatibility and upgrade paths matter a lot when your product is expected to last decades.

Tariff Exposure. Badger has used pricing actions to offset cost pressures, including new import tariffs introduced in 2025. But trade policy is a moving target. If tariffs shift again, input costs can swing, and that volatility can squeeze margins—especially when customers are slow-moving and contracts are negotiated in public.

The Bull Case

Climate Change is the Ultimate Tailwind. Water scarcity and water stress are no longer abstract. Droughts, floods, and aging infrastructure failures are showing up more frequently and more expensively. Regions are investing in reservoirs, canals, and groundwater recharge to stabilize supply. And every high-profile main break or restriction order pushes utilities toward one conclusion: you can’t manage what you can’t measure. Badger sells the measurement—and the intelligence layer on top.

Federal Infrastructure Support. The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, passed in 2021, authorized $55 billion for drinking water, wastewater, water storage, and water reuse projects. The Inflation Reduction Act, passed the following year, included $550 million to assist disadvantaged communities with water supply projects. For an industry that runs on long replacement cycles and constrained budgets, targeted federal funding can materially accelerate modernization.

International Expansion Opportunity. About 90% of sales come from the United States, with the remaining 10% mainly from Asia, Canada, Europe, and the Middle East. The U.S. may be mature, but the rest of the world is far less penetrated—and the underlying problems Badger addresses aren’t uniquely American. Water loss, metering accuracy, and system visibility are global issues with global demand.

Recurring Revenue Transformation. The core bullish bet is that Badger keeps shifting from a “sell a meter every couple decades” business to a platform with recurring software and service revenue. SaaS revenue has been growing at a 28% CAGR, and gross margins have expanded toward a normalized 39–42% range. If software continues to become a larger share of the mix, the company’s financial profile can keep moving closer to what the market is already pricing in.

Balance Sheet Strength. Badger is profitable and well-capitalized, with $201.7 million in cash and no debt. That gives it room to keep investing, keep acquiring, and keep compounding—without needing perfect economic conditions to survive the next downturn.

XI. Key Performance Indicators for Tracking

If you’re tracking Badger Meter as it compounds, there are three metrics that tell you whether the story is getting stronger—or starting to wobble:

-

SaaS revenue growth rate. This is the clearest scoreboard for the transformation from “we sell meters” to “we run a platform.” Software revenue has grown at a 28% CAGR over the last five years. If that growth holds or accelerates, it’s a sign BEACON and the broader software layer are becoming more central to the relationship. If it slows meaningfully, it could signal adoption friction or a plateau in upgrades.

-

Utility Water sales growth. Utility Water is the engine room, representing about 88% of net sales. When this segment is growing, it usually means Badger is winning deployments, expanding its installed base, and pulling more utilities into its connected ecosystem—meters, endpoints, and software together.

-

Operating margin expansion. Badger posted a record 19.1% operating margin in 2024. The question now is whether margins keep widening as software and services become a bigger slice of the mix, and as the company continues to scale efficiently. If margins stall or compress, it can be an early warning that costs are rising faster than pricing power and mix shift can offset.

XII. Conclusion: The Quiet Revolution

Badger Meter’s journey—from a Milwaukee machine shop to a smart water platform—reads like a playbook for how legacy industrial companies can survive a technology transition and come out stronger. It didn’t throw away its heritage. It used it. A century of trust earned by shipping reliable brass and bronze meters became the credibility that let Badger sell connected endpoints, cloud software, and real-time monitoring to some of the most risk-averse customers on earth.

As the company put it: “Our track record of differentiated performance continued. This, coupled with execution of our strategic priorities, including investments in hardware and software innovation and complementary acquisitions, demonstrates our ability to further capitalize on the robust demand environment for comprehensive and tailorable digital water management solutions.”

And the demand environment really is robust—because the problem is getting worse. Water stress isn’t a niche concern or a future scenario. Roughly 4 billion people—nearly two-thirds of the global population—experience severe water scarcity during at least one month of the year. Earlier estimates from the early to mid-2010s put about 1.9 billion people, around 27% of the world, in potentially severely water-scarce areas. By 2050, that number is expected to rise to somewhere between 2.7 and 3.2 billion.

Against that backdrop, Badger’s positioning looks less like “industrial tech” and more like critical infrastructure. The company sits where the physical world meets the digital one: it measures water, helps monitor its quality, watches what’s happening inside aging pipes, and turns that reality into data utilities can act on. In a world of scarcity, tightening regulation, and climate volatility, that kind of accountability becomes a utility’s edge.

For patient investors who like quiet compounders, Badger Meter offers something that’s increasingly hard to find: a company that knows exactly what job it exists to do, executes relentlessly, and keeps expanding the value of that job over time. The frost-proof meter of 1905 evolved into a smart water platform by 2025—but the mission never really changed: measure the world’s most precious resource with accuracy, durability, and simplicity.

The water still flows. And Badger Meter is still counting every drop.

XIII. Carve Outs

If you want to go deeper on the ideas behind Badger Meter’s story—water scarcity, infrastructure, and the politics that make “simple” upgrades so hard—here are three great places to start:

Cadillac Desert by Marc Reisner — The classic history of water in the American West. It explains how we built the modern water system, why the incentives are so tangled, and why water decisions so often become political landmines.

The Water Knife by Paolo Bacigalupi — A fast, unsettling piece of speculative fiction about water scarcity in the Southwest. It’s not a business book, but it captures the human consequences of a world where water becomes power.

Xylem (XYL) — If you’re looking at the water technology landscape as an investor, Xylem is a larger-cap way to get exposure to many of the same long-term tailwinds, including smart water infrastructure.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music