BankUnited Inc.: From Spectacular Failure to Disciplined Revival

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

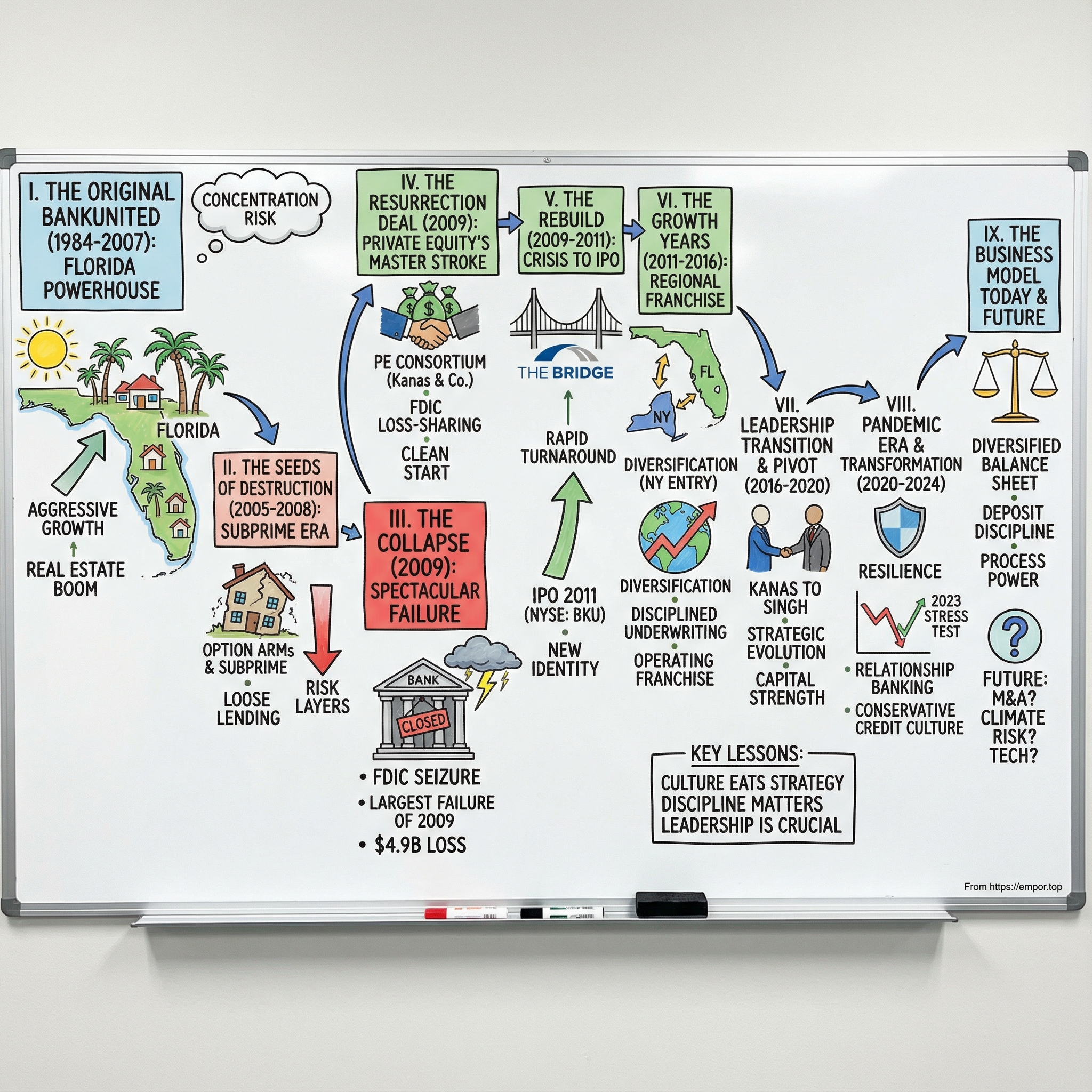

Picture this: May 21, 2009. The sun is going down over Coral Gables, Florida, throwing long shadows across the manicured streets and Mediterranean Revival facades. Inside BankUnited’s headquarters, there’s nothing tranquil about the scene. Federal regulators have arrived with a final decision. The bank that only recently looked like a monument to Florida’s unstoppable prosperity is being seized—capped off as the largest bank failure of 2009, and a multibillion-dollar hit to the FDIC’s insurance fund.

And yet, that’s not the end of the story. It’s the twist.

Because in less than two years, BankUnited would be back—reborn through a deal that read like a crisis-era cheat code. A consortium of private equity heavyweights, paired with a banker famous for building and selling a great franchise, stepped in and turned a wreck into one of the fastest turnarounds in modern American banking. By January 2011, BankUnited was public again. The investors who funded the resurrection walked away with extraordinary returns.

Fast forward to today: BankUnited trades as BKU on the NYSE. It’s a national bank headquartered in Miami Lakes, Florida, with operations spanning Florida, the New York metro area, Dallas, and an Atlanta office focused on the Southeast. The company reports total assets of $35.8 billion. Rajinder Singh is President and CEO, and under his leadership BankUnited has grown into the largest independent depository institution headquartered in Florida.

But if you stop there—if you only read the corporate profile—you miss the point.

BankUnited’s story is one of the most dramatic arcs in American banking: a spectacular death in the financial crisis, followed by an improbable, disciplined revival. So the central question of this episode is simple to ask and hard to pull off: how does a bank fail so completely that regulators shut it down, and then come back as a credible growth story?

The answer is a mix of hubris, regulatory blind spots, private equity opportunism, and—once the smoke clears—a masterclass in the unglamorous fundamentals that actually make banks work.

BankUnited was founded in 1984 and grew into a Florida powerhouse by leaning heavily into residential real estate. When the housing market turned, the bank’s exposure to risky adjustable-rate mortgages and real estate-linked lending didn’t just hurt it—it broke it, making BankUnited one of the most consequential collapses of the 2007–2010 crisis era.

In other words: this is really a tale of two banks. The first BankUnited chased growth and rode the boom until it couldn’t. The second was rebuilt from the ashes with a very different set of instincts—credit discipline, deposit gathering, and a relentless focus on survival.

Our story runs in three acts: the go-go years when Florida felt like a one-way escalator up, the collapse that turned BankUnited into a case study in what not to do, and the turnaround engineered by John Kanas and his private equity partners, who saw opportunity where everyone else saw rubble.

II. The Original BankUnited: Building a Florida Powerhouse (1984–2007)

To understand BankUnited’s rise—and why its fall was so violent—you have to start with Florida itself.

Go back to Coral Gables in 1984. It’s an elegant Miami suburb: Mediterranean-style buildings, banyan-lined streets, the kind of place that always feels like it’s doing well. BankUnited opened there as a small community savings bank, one of hundreds across the state. Nothing about it screamed “future headline.”

But Florida has a way of turning small bets into huge ones. Warm weather, steady in-migration, and a constant churn of new development made real estate feel less like a cyclical business and more like a permanent engine. Over time, BankUnited leaned hard into that engine. It grew up as a Florida bank built around housing—residential mortgages, construction lending, and financing the neighborhoods that seemed to appear overnight.

By the early 2000s, the backdrop had shifted from healthy growth to full-on mania. Easy mortgages, low rates, and rampant speculation pushed home prices up fast. From 2000 to 2007, Florida housing prices surged by about 96%—nearly doubling, and leaving incomes far behind. The prevailing belief wasn’t just optimism. It was conviction: prices only went one direction.

And if you look at Florida’s longer history, that confidence rhymes. Boom-and-bust cycles have repeated for generations: waves of outside money, abundant credit, rapidly appreciating property values—and then the air comes out. In the 2000s, the epicenter included Miami Beach, Coral Gables, Hialeah, Miami Springs, and Hollywood—exactly the kinds of markets where BankUnited built its footprint.

South Florida also had a unique accelerant: it wasn’t just a place Americans moved to. It was a financial crossroads. Miami functioned as a gateway to Latin America, drawing wealth from Venezuela, Brazil, Colombia, and beyond—capital looking for stability, property, and a safe harbor from political volatility back home. That influx helped reinforce the sense that demand would never stop.

BankUnited took full advantage. Through the 1990s and into the 2000s, it expanded aggressively—both organically and through acquisitions—until it had more than 80 branches across Florida. The model was simple, and for a while it looked brilliant: keep feeding the mortgage machine, keep financing construction, keep growing alongside the state.

By 2007, BankUnited was one of Florida’s largest banks—a real hometown powerhouse. But the thing that made it powerful also made it fragile. It had effectively tied its fate to one geography and one asset class. In banking, that’s not just a strategy. It’s a vulnerability. Concentration risk is the silent killer, and BankUnited was making a massive, leveraged bet that Florida housing would keep climbing.

That’s the first key point for understanding BankUnited today: the original version of this bank was built for expansion, not resilience. It was an aggressive growth machine—chasing volume, fee income, and market share—and it worked, right up until it didn’t. The institution that exists now was rebuilt from the wreckage. Same name, very different philosophy.

III. The Seeds of Destruction: The Subprime Era (2005–2008)

Walk into a BankUnited branch in 2005 and you’d see the boom in real time. Mortgage officers were working late. Files piled up. Phones rang. Each quarter seemed to validate the same story: Florida was hot, housing was hot, and BankUnited was printing growth.

But underneath the pace and the optimism, the bank was loading the balance sheet with exactly the kind of risk that only looks manageable on the way up.

Later, the Treasury Department’s Inspector General would lay it out in a Material Loss Review that reads like a slow-motion tragedy: BankUnited didn’t put adequate controls in place. It didn’t manage the risks of its breakneck growth. And it concentrated heavily in one of the most combustible products of the era: option ARMs. The review ultimately tied the failure to losses in that higher-risk, geographically concentrated option ARM portfolio—and to unsafe and unsound practices that steadily pushed the bank’s risk profile higher.

To understand how BankUnited walked itself into a catastrophe, you have to understand what an option ARM actually was. It was a mortgage designed to make payments look cheap—at least at first. Typically, borrowers were given multiple monthly payment choices. The lowest option was often so low it didn’t even cover the interest due. The unpaid interest got added to the loan balance, so instead of paying down a mortgage, the borrower watched the balance rise over time. That’s negative amortization: a mortgage that grows.

And the trap was built in. BankUnited’s option ARMs would “recast” into much higher payments after five years, or sooner if the loan balance grew too much from negative amortization—generally when it exceeded about 115% of the original loan amount. In plain English: borrowers were signing up for a payment shock, whether they realized it or not.

BankUnited didn’t just participate in this market. It swallowed it whole.

By March 2008, option ARMs were 59% of the bank’s total loans—about $7.4 billion. By the end of 2007, they were even more dominant: 70% of the residential loan portfolio and roughly 60% of total loans. That’s not a business line. That’s a single point of failure.

Then there was underwriting. By early 2008, more than a tenth of the option ARM portfolio consisted of DocEase loans—reduced-documentation products where verifying a borrower’s ability to repay could be optional in practice. After the collapse, the FDIC would accuse former management of fostering an overly aggressive lending mentality—summed up in a line that’s almost too on-the-nose: “to make the loan as long as the borrower had a pulse.”

The incentives inside the bank matched the behavior. The FDIC later argued that compensation policies encouraged loan production while effectively ignoring what happened after closing—creating personal financial upside for officers and directors to lean into risky, aggressive, short-term lending.

Zoom out and you can see just how far BankUnited had drifted into the subprime ecosystem. The Center for Public Integrity found that BankUnited FSB made almost $4.5 billion in subprime loans from 2005 to 2007—enough to put it among the top 50 subprime lenders in the country.

By 2008, the cracks weren’t subtle. BankUnited’s troubled asset ratio was in a different universe than a typical U.S. bank’s. At the end of 2008, it stood at 251.6, and MSNBC listed it as the third highest ratio among the U.S. banks it examined.

Which brings us to the uncomfortable question: where were the regulators?

An internal review by the Office of Thrift Supervision—BankUnited’s regulator—later concluded that objectionable practices were occurring as early as 2004, 2005, and 2006, and they weren’t addressed in time. OTS itself would later be abolished by the Dodd-Frank Act, in part because of failures like this one.

And this isn’t just history for history’s sake. For today’s investors, it’s the “why” behind the modern BankUnited’s personality. The conservative credit discipline you see in the rebuilt institution isn’t branding. It’s scar tissue.

IV. The Collapse: America's Largest Bank Failure of 2009

The end came on a Thursday.

On May 21, 2009, the Office of Thrift Supervision closed BankUnited, FSB and appointed the FDIC as receiver. In a crisis already littered with broken banks, this one still managed to stand out: it was the largest bank failure of 2009, the 34th FDIC-insured institution to hit the Failed Bank List that year, and the FDIC estimated it would cost the Deposit Insurance Fund $4.9 billion.

That number wasn’t just large. It was shocking relative to the size of the bank.

BankUnited had about $12.8 billion in assets at the time. An estimated $4.9 billion loss meant the FDIC was staring at a hit equal to roughly 38% of the bank’s asset base. That kind of impairment raises an inevitable question, and it was asked loudly at the time: why wasn’t BankUnited shut down sooner?

By then, there was no way to sugarcoat what was happening inside the institution. The OTS said BankUnited had reported $1.2 billion in losses in the prior year as loan defaults piled up, and that the thrift was “critically undercapitalized and in an unsafe condition to conduct business.”

What made the failure especially notorious wasn’t just the raw dollar cost—it was how thoroughly the asset portfolio had been wrecked. Compared with other major failures, BankUnited’s loss was extreme as a percentage of assets. IndyMac, which failed in July 2008, cost the FDIC $8.9 billion—about 27% of assets. American Savings & Loan’s September 1988 failure cost $5.4 billion—about 18% of assets. BankUnited’s estimated loss rate was worse. It was a brutal signal of two forces colliding: years of loose lending standards and a Florida real estate collapse severe enough to turn “good times” collateral into quicksand.

This is also where the earlier option ARM story cashes out. In the OTS’s own postmortem, the cause was clear: “ultimately, the combination of an excessive concentration in payment option ARM loans with too many risk layers and rapidly deteriorating economic conditions overwhelmed BankUnited’s capacity to absorb the losses on the portfolio.”

On paper, BankUnited’s parent company was BankUnited Financial Corp. On the ground, it was a large operating business—about 1,083 employees and 85 branches, all in Florida, concentrated along the state’s southeast coast. In other words, the bank was not just exposed to Florida housing. It was Florida housing.

And then there’s the part that still makes the story feel uncomfortable: the regulatory timeline.

BankUnited remained open even though it had been critically undercapitalized since December 31. At that point, its Tier 1 leverage ratio was 1.37% and its total risk-based capital ratio was 3.60%—far below what’s required to be considered adequately capitalized (5% and 10%, respectively). When a bank’s capital falls that low, it doesn’t have a cushion. It has a trapdoor.

There were also questions about how capital was reported. The holding company transferred $80 million to the institution in August 2008, but that capital appeared in BankUnited’s June 30, 2008 thrift financial report. An inspector general report didn’t name BankUnited specifically, but it said the OTS had directed one thrift to backdate an August capital infusion to June 30—exactly the kind of detail that, in hindsight, reads like a system trying to buy time.

BankUnited didn’t fail in isolation. It failed in a wave. The 34 bank failures by that point in 2009 compared with 25 in all of 2008 and just three in 2007. As unemployment rose, home prices fell, and defaults surged, failures cascaded and drained the insurance fund—down to $18.9 billion as of December 31, from $52.4 billion at the end of 2007.

If you’re looking at BankUnited today, this collapse isn’t just a dark chapter—it’s the origin story of the bank’s modern personality. Concentration risk is deadly. Incentives that reward volume over credit quality eventually detonate. Hypergrowth should trigger scrutiny, not applause. And when regulators move slowly, problems don’t stay contained; they compound.

The current BankUnited’s emphasis on conservative underwriting and a more diversified mix of business exists because the institution was rebuilt in the shadow of this failure. The old BankUnited isn’t a competitor anymore—but it’s still a warning, and it shows up in every decision the new one makes.

V. The Resurrection Deal: Private Equity's Master Stroke (2009)

Here’s where the story takes a hard left. Even as regulators were preparing to shut BankUnited’s doors, another drama was playing out in conference rooms and back channels from Washington to Wall Street. A group of private equity firms looked at this flaming wreck and didn’t just see losses. They saw a deal.

At the center of it was John Kanas—a banker with the rarest kind of credibility: he’d already built a franchise the old-fashioned way and sold it at exactly the right time. Kanas had spent roughly three decades running North Fork Bank, then sold it to Capital One in December 2006, near the peak of bank valuations. Capital One paid about $15 billion for a bank with roughly $60 billion in assets—just months before the mortgage crisis turned into a market collapse.

Kanas’s own origin story is almost too perfect. Before he was a banking legend, he owned a deli. One day, his wife went to their bank to withdraw $5,000 from their joint account and was told she needed her husband’s signature. So Kanas told her to go back the next day and try to close the account instead. The bank’s rules were stricter for a withdrawal than for shutting the whole relationship down, and she walked out with $10,000. Kanas later told Forbes the absurdity of that moment flipped a switch: “I thought, hey, these people don’t know what they’re doing. This is the industry for me.”

At North Fork, he backed up the swagger with results. Through the late ’90s and early 2000s, the bank’s return on equity hovered around 20%, well above what many analysts view as the industry’s approximate cost of capital. Return on assets ran around 2%. In other words: he didn’t just talk a good game. He put up numbers that made him a natural candidate to lead a resurrection.

After a short stint at Capital One, Kanas shifted into crisis mode investing. During the financial crisis, he partnered with WL Ross—Wilbur Ross’s private equity firm—to hunt for distressed and failed banks. But in May 2009, he wasn’t just looking to invest around the edges. He wanted a platform.

BankUnited was that platform.

Kanas later summed up the strategy with blunt honesty: “We were searching for the biggest disaster we could find. We knew BankUnited would be an effective bankruptcy and the FDIC would have to back the deal.”

And that’s exactly what happened.

A newly formed institution—organized as BankUnited, Inc. on April 28, 2009 by a management team led by Kanas—was capitalized with $945 million from a who’s-who lineup: funds advised by The Blackstone Group, The Carlyle Group, Centerbridge Partners, and WL Ross & Co., among others. When the Office of Thrift Supervision closed BankUnited, FSB on May 21 and appointed the FDIC as receiver, the FDIC turned around and facilitated the sale of the failed bank’s operations to this new vehicle. The newly formed bank was granted a savings association charter and acquired substantially all of BankUnited, FSB’s assets, assumed all non-brokered deposits, and took on substantially all other liabilities.

But the real magic—what made the economics so eye-popping, and the politics so combustible—was the FDIC loss-sharing agreement.

Alongside the acquisition, BankUnited entered into Loss Sharing Agreements with the FDIC that covered certain legacy assets: the entire loan portfolio and OREO, plus certain purchased investment securities, including private-label mortgage-backed securities and non-investment grade securities. Some assets were explicitly not covered—cash, certain investment securities purchased at fair market value, and other tangible assets. And importantly, the loss-share protection didn’t extend to anything the new bank later originated or acquired. This was a cleanup backstop for the mess they inherited, not a blanket guarantee going forward.

By June 30, 2010, the “Covered Assets” totaled about $4.4 billion in book value, with a total unpaid principal balance of $9.4 billion. Overall, the FDIC agreed to share losses on roughly $10.7 billion in assets. The headline term was the one that mattered: the FDIC would absorb 80% of losses up to a threshold of approximately $4.1 billion, with additional sharing beyond that point. In plain English, the government provided meaningful downside protection—while the private investors kept the upside.

Normally, the FDIC prefers a clean handoff: one operating bank takes over another. But Florida real estate was still imploding, BankUnited’s losses were enormous, and the bid pool of traditional acquirers appears to have been thin. In the end, the FDIC allowed private equity—rather than another bank—to assume the assets and liabilities of BankUnited, FSB, paired with a major capital injection and a loss-share structure that reduced the risk of taking on a toxic balance sheet.

Kanas also didn’t show up alone. He brought a bench.

BankUnited’s vice chairman and chief lending officer, John Bohlsen, had worked with him at North Fork. Raj Singh, BankUnited’s chief operating officer, had been head of corporate strategy and development at North Fork and later worked at WL Ross & Co. The board, meanwhile, reflected the ownership: private equity-nominated directors including Wilbur Ross, Carlyle managing director Olivier Sarkozy, and Blackstone senior managing director Chinh Chu.

The deal’s creativity didn’t stay a secret for long. Kanas later said that within six weeks, Goldman raised $25 billion for investors looking to come to Florida and pursue similar opportunities. But BankUnited’s setup was hard to replicate—especially once competition arrived and prices adjusted. He also noted BankUnited had talked to dozens of Florida banks but couldn’t agree on valuation.

Predictably, the backlash came fast. Critics called it a sweetheart arrangement—private equity profiting while the FDIC, funded by insurance premiums ultimately backed by the government, absorbed a huge portion of losses. Defenders argued the FDIC was choosing between bad options, and that liquidation would have cost more while doing more damage to depositors, borrowers, and communities.

Whatever your view, the outcome was undeniable: the “new” BankUnited emerged extremely well-capitalized. By June 30, 2010, it reported a 10.3% tangible common equity ratio, a 9.8% Tier 1 leverage ratio, and a 41.9% Tier 1 risk-based ratio. With that cushion, it began paying dividends—declaring a quarterly dividend of $14 million on September 17, 2010, and a special one-time dividend of $6 million on October 19, 2010.

And Kanas wasn’t shy about the plan. Florida and the broader Southeast were still significantly distressed, and management believed that meant opportunity: acquire institutions, recruit talent, and win customers from weaker competitors. With strong capital, ongoing earnings power, and a scalable operating system, BankUnited had the flexibility to play offense while others were still trying to survive.

For investors, this is the masterclass. The consortium understood that a loss-share agreement could turn a toxic pile of legacy mortgages into something close to a structured opportunity: limited downside, enormous upside if you could stabilize the franchise. Add a proven operator in Kanas, and you get the kind of asymmetric payoff profile that only shows up in crises—when the rules bend, the government needs solutions, and speed matters as much as price.

VI. The Rebuild: From Crisis Bank to IPO (2009–2011)

Once the FDIC handed the wreckage to Kanas and the investor consortium, BankUnited effectively restarted as a brand-new company wearing an old name. The mandate was straightforward: strip out the crisis DNA, rebuild the operating machine, and prove to the market that this wasn’t yesterday’s Florida mortgage story anymore. The business was restructured from the top down, and employees were consolidated into a new headquarters in Miami Lakes.

What happened next was the part that made people sit up. The turnaround moved at a pace that’s almost unheard of in banking. Less than two years after the failure, BankUnited was ready to sell itself back to public investors.

On February 2, 2011, BankUnited, Inc. (NYSE: BKU) completed its initial public offering at $27.00 per share, closing an offering of 33,350,000 shares of common stock. Of those, BankUnited itself sold 4,000,000 shares, while selling stockholders sold 29,350,000 shares, including 4,350,000 shares sold through the underwriters’ over-allotment option, exercised in full.

Demand was strong enough that the bank sold about 3 million more shares than expected, and at a price above what many analysts had been modeling. The deal had been marketed with an expected price range of $23 to $25, but it priced at $27. On its first day of trading, the stock popped—up 5.2%—after the offering raised $783 million.

For the private equity backers, this was the payoff. Reports at the time estimated they were looking at hundreds of millions of dollars in IPO proceeds, and filings showed the owners had effectively paid about $10.01 per share on average. At $27, that implied a gain of roughly 170% in under two years—an eye-widening result in a business that usually rewards patience, not speed.

Wall Street’s enthusiasm wasn’t just about the trade. It was about the setup: a management team with a strong track record, sponsors with reputations that opened doors, and a structure that had insulated the new bank from a big chunk of the inherited losses. As part of the FDIC-assisted transaction, the FDIC also received a warrant, later amended, that it exchanged for at least $25 million in cash after the IPO.

BankUnited also used the moment to define who it wanted to be. In its IPO prospectus, the company framed its pitch in plain terms: “Our customers are attracted to us because we offer the resources and sophistication of a large bank, as well as the responsiveness and relationship-based approach of a community bank.” The new identity was meant to signal something bigger than a Florida thrift—local service, but with real scale and ambition.

Even the branding told the story. The old logo leaned hard into Florida, featuring a palm tree. The new design introduced an abstract icon nicknamed “the bridge,” built from the curving forms of the letters B and U. It nodded to Miami’s causeways, but it was also symbolic: a bridge between south and north, local and global, today and tomorrow. The bank made that repositioning feel real when executives rang the opening bell of the New York Stock Exchange on January 28, the day of the IPO.

At the time, BankUnited was still a federally chartered, federally insured savings association headquartered in Miami Lakes. It had $11.2 billion in assets, more than 1,100 professionals, and 78 branches across 13 counties. And it articulated a mission designed to put daylight between the new bank and the old one: “We are building a premier, large regional bank with a low-risk, long-term value-oriented business model focused on small and medium sized businesses and consumers.”

For investors, the BankUnited IPO became the cleanest case study of a crisis-era private equity playbook: buy distressed assets at a steep discount, stabilize the franchise under proven leadership, and exit through public markets. With substantial fresh capital, FDIC loss-sharing protection on legacy assets, and Kanas driving execution, BankUnited had close to ideal conditions for value creation—conditions that would be talked about and copied for years, even if few later deals matched the outcome.

VII. The Growth Years: Building a Regional Franchise (2011–2016)

Once the IPO glow faded, BankUnited faced the question that always separates a good turnaround from a great company: how do you grow without reloading the same gun that blew you up last time?

Kanas and team had a clear answer. Diversify the balance sheet, diversify the footprint, and stay allergic to “growth for growth’s sake.” And the most symbolic move they made was also the most counterintuitive: a Florida bank pushing hard into New York.

That pivot became real in early 2012. On February 29, 2012, BankUnited, Inc. (NYSE: BKU) closed its acquisition of Herald National Bank. At the same time, BankUnited converted its charter from a thrift into a national bank—now named BankUnited, National Association. With that conversion, BKU became a bank holding company.

Rajinder P. Singh, the company’s Chief Operating Officer, framed it as a building block, not a one-off deal: “We are excited to successfully complete the acquisition of Herald. The conversion to a bank holding company and the acquisition of Herald are an integral step in our corporate vision and we remain focused and committed to our future growth plans.”

New York wasn’t random. The leadership bench had deep roots there—Kanas had spent 30 years building North Fork into a New York powerhouse, and many of his lieutenants knew the market cold. And in the aftermath of the recession, BankUnited saw New York as a comparatively resilient economic story. Internally, the thesis was simple: North Fork was gone, no one had truly stepped into that slot, and there were customers—and former employees—who were open to doing business with a familiar team again.

While the headlines focused on geography, the bigger change was discipline. The “new” BankUnited emphasized higher-quality originations and tighter risk management as it rebuilt a loan book that, right after the FDIC transaction, was essentially starting over. By March 31, 2014, new loans—those originated or purchased after the acquisition—had grown from near zero to $8.6 billion, while total deposits had climbed to $11.1 billion.

The scale followed. By the end of 2015, BankUnited’s assets had doubled under Kanas to more than $26 billion. And the footprint shift wasn’t cosmetic: eventually, the bank had more loans outstanding in New York than in Florida—a remarkable reversal for an institution that had once been almost entirely a bet on one overheated state.

Just as important was what BankUnited didn’t do. In interviews, Kanas explained that he originally expected a rapid roll-up of Florida banks, but the window closed quickly once competitors tried to copy the playbook:

“We expected to acquire a dozen or more banks after we came to Florida. After we bought BankUnited—it was very creative and lucrative—Goldman within six weeks raised $25 billion for people to come to Florida and do the same thing we did. So the economics of the deals never made sense. We have talked to 50 or 60 banks in Florida, but have never agreed on price. We think banks should trade at a lower multiple than banks are willing to sell them.”

That willingness to walk away—especially when everyone around you is chasing deals—was the cultural inversion of the old BankUnited. The predecessor had pursued size and volume. The rebuilt bank prioritized returns and survivability.

And it showed up in performance. In a period that wasn’t exactly a golden age for bank growth, BankUnited held its own. By mid-2017, its return on equity was about 10%, right in line with the industry’s top-performing companies.

For investors, these years mattered because they answered the skepticism hanging over any private-equity-led rescue. This wasn’t just financial engineering plus a lucky FDIC structure. BankUnited had become a real operating franchise—one built on disciplined underwriting, a broader geographic base, and profitability that looked sustainable, not borrowed from the next credit cycle.

VIII. Leadership Transition & Strategic Pivot (2016–2020)

Every turnaround has a moment when the founder-operator steps back and the organization has to prove it isn’t just riding one person’s instincts. For BankUnited, that moment arrived in 2016.

John A. Kanas—the banker who had built North Fork and then engineered BankUnited’s resurrection—announced he would step down as CEO at the end of the year. He wasn’t disappearing; he would remain chairman. But the message was clear: the rebuild phase was over. Now the question was whether BankUnited could keep compounding as a disciplined regional bank.

The handoff went to Rajinder Singh, who became President and CEO on January 1, 2017. If Kanas was the headline name, Singh was the operating engine. He’d been part of the BankUnited story from the start in 2009, served as Chief Operating Officer from October 2010, and helped turn a post-seizure shell into a public company again by 2011. This was succession by design—continuity, not a clean break.

By January 2019, Singh was also appointed Chairman of the Board, completing the transition from the Kanas era to the next chapter of leadership. His résumé fit the job: more than 25 years in financial services, with executive roles spanning WL Ross & Co., Capital One, North Fork Bancorporation, and FleetBoston. He also took on prominent industry and policy roles, serving on the Board of Directors of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta and the Mid-Size Bank Coalition of America. From January 2020 through December 2022, he served on the Federal Reserve’s Federal Advisory Council for the Atlanta Region, and in 2023 he served as Chairman of the MBCA.

Kanas framed the move as a natural evolution, praising Singh as a longtime partner and the right person to lead the next stage. Singh’s own message was equally consistent with the bank’s post-crisis identity: keep executing the strategy that had made BankUnited “growing, profitable, safe and sound.”

Operationally, Singh also built out the next layer of leadership. Thomas M. Cornish became Chief Operating Officer in January 2017, after serving as President of the Florida Region. Cornish brought a long management background, including years at SunTrust Bank and leadership of Marsh & McLennan Agency’s Florida region, where he was recognized locally with CEO awards.

Singh took over at a particularly revealing moment. By then, BankUnited had already moved beyond the FDIC loss-sharing era—the safety net that had helped stabilize the inherited mess was no longer part of the story. The training wheels were off. From here on out, credit outcomes would reflect the bank’s own underwriting and portfolio choices in real time.

That raised the strategic questions that define any regional bank in the late-cycle years: how to grow when the recovery was maturing, how to compete in a low-rate environment, and how to keep diversifying the balance sheet without drifting back toward the kind of concentration risk that once destroyed the franchise.

By the time the calendar turned to 2020, the transition was complete—and BankUnited entered the year with something it didn’t have in the old days: a strong capital position and a clean balance sheet. Within weeks, those strengths would be tested, as the world changed dramatically in March 2020.

IX. The Pandemic Era & Recent Transformation (2020–2024)

When COVID-19 shut down huge parts of the economy in March 2020, banks immediately started preparing for the worst. The last time the world had seen a shock of that magnitude, credit losses didn’t just rise—they cascaded. And for BankUnited, with deep roots in Florida and a balance sheet built around commercial lending, the setup looked uncomfortably familiar: a sudden economic stop, uncertainty around property values, and the fear that borrowers would simply run out of oxygen.

What actually happened was messier—and, for BankUnited, far more survivable—than the early panic suggested.

The stress didn’t end with the pandemic. In 2023, the regional banking system took its biggest hit since the global financial crisis as Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, and First Republic failed. Those three collapses were estimated to cost the FDIC’s deposit insurance fund about $35 billion, and they sent a shockwave through markets. Investors didn’t need a spreadsheet to know what the fear was: if depositors could move money with a few taps, which bank was next?

BankUnited wasn’t immune to that anxiety. Trading in the group turned chaotic, with violent swings in the SPDR S&P Regional Banking ETF (KRE) as the market tried to sort “safe” from “at risk” in real time.

One useful comparison from that moment is New York Community Bancorp. NYCB stepped in as a rescuer by purchasing some assets of the failed Signature Bank—but the move also changed the bank overnight. The rapid consolidation doubled its size and pushed it above the $100 billion asset threshold, bringing a tougher regulatory regime. NYCB later said those requirements helped explain why it needed to bolster its balance sheet by cutting its dividend and increasing what it set aside for future loan losses.

BankUnited’s story in the same period was less dramatic, but that’s the point. Its conservative credit culture—built in direct response to the 2009 failure—positioned it to avoid the worst outcomes. Just as importantly, its deposit base proved stable enough to avoid the kinds of sudden runs that proved fatal elsewhere.

As 2023 wore on, pressure across the sector began to ease. Many regional banks managed their interest rate risk and saw deposit conditions stabilize. Industry observers said things started to feel “a lot more normal.” For BankUnited, a diversified funding base and a relationship-driven commercial banking model helped provide that resilience when confidence across the system was being tested.

Financially, the results showed up in 2024. BankUnited reported revenue of $958.35 million, up from $873.04 million the prior year, and earnings of $228.35 million, also higher year over year. In a period when regional banks were being judged harshly—and often indiscriminately—those numbers signaled that BankUnited could still produce meaningful profits in a difficult environment.

The bank also kept pushing its longer-term strategy: diversify and expand thoughtfully. It entered Charlotte, North Carolina with a new corporate banking and commercial real estate team, extending its presence in the Southeast beyond its Florida and New York anchors.

For investors, the combined arc of the pandemic and the 2023 regional banking shock served as a real-world stress test—and, for BankUnited, a validation. The post-crisis model wasn’t built for perfect conditions. It was built to hold up when conditions stopped being perfect.

X. The Business Model Today: What Makes BankUnited Tick

Today’s BankUnited barely resembles the institution that cratered in 2009. BankUnited, Inc. (NYSE: BKU) is a bank holding company with total assets of $35.8 billion as of September 30, 2024. Its main operating subsidiary is BankUnited, N.A., a national bank headquartered in Miami Lakes, Florida. From there, it serves consumers and businesses through banking centers in Florida, the New York metropolitan area, and Dallas, Texas, and it supports a broader set of wholesale offerings through an Atlanta office focused on the Southeast.

Beyond its branch footprint, BankUnited also runs national platforms that offer certain commercial lending and deposit products—an extension of the same theme you see throughout the modern franchise: diversify the sources of growth, and don’t let the bank become hostage to a single market or product again.

Leadership continuity is a big part of that story. Rajinder Singh, who became President and CEO on January 1, 2017, has been a central figure since 2009, helping drive the post-failure transformation and the operating discipline that followed.

The footprint today reflects that deliberate diversification. Florida is still the anchor, but New York gives BankUnited exposure to one of the most competitive and opportunity-rich commercial banking markets in the world—exactly the kind of second engine that the old, Florida-only BankUnited never had.

Reputation has become an asset, too. BankUnited has been ranked #4 among America’s Most Trusted Companies in the Banking industry and has been included on the Newsweek and Statista America’s Most Trusted Companies Award List. It has also been ranked year over year as the #1 South Florida Community Bank based on assets by the South Florida Business Journal.

But the bigger shift—and the one that actually determines whether a bank survives the next downturn—is what sits on the balance sheet.

The loan mix has moved a long way from the residential mortgage concentration that destroyed the predecessor institution. Today, BankUnited emphasizes commercial real estate (particularly multi-family), commercial and industrial lending, and specialty finance products. The goal is straightforward: reduce concentration risk, build a more stable earnings engine, and avoid the single-product trap that made the 2009 collapse inevitable.

On the funding side, the product set looks like what you’d expect from a full-service regional bank: checking, money market, and savings accounts; certificates of deposit; and treasury and cash management services for businesses. On the lending side, it spans commercial loans such as equipment loans; secured and unsecured lines of credit; formula-based lines of credit; owner-occupied commercial real estate term loans and lines of credit; mortgage warehouse lines; subscription finance facilities; letters of credit; commercial credit cards; Small Business Administration and U.S. Department of Agriculture offerings; Export-Import Bank financing products; trade finance; business acquisition finance facilities; along with commercial real estate loans and residential mortgages.

The key strategic choice is less about the menu and more about how the bank wants to be funded. BankUnited’s deposit strategy emphasizes sticky commercial relationships over rate-sensitive retail deposits. Instead of trying to win by paying the highest rates—deposit “hot money” that can leave overnight—it aims to build deposits that are tied to operating businesses and lending relationships. That mindset reads as especially relevant after 2023, when deposit flight was the killer blow for certain banks.

That relationship-first positioning is reinforced by customer preferences. A 2025 BankUnited survey found nearly 2x more small and medium-sized business owners valued in-person support (32%) than digital tools (17%) when the stakes were high. In other words, when things get complicated, plenty of customers still want a banker, not a chatbot—and BankUnited is choosing to compete there.

All of this sits on top of what may be the bank’s most important asset: its credit culture. The old BankUnited became infamous for a mentality the FDIC later described as making loans as long as the borrower had “a pulse.” The rebuilt institution is run by people with institutional memory of what that kind of thinking costs. The underwriting standards are tighter, and the scars function as a governor on risk.

BankUnited describes its operating performance as consistent, supported by a robust capital foundation and prudent risk management. It also frames trust as a core part of the value proposition—stability and security as products in their own right.

Stack it up against regional peers like New York Community Bancorp, Valley National, and others, and a few differentiators stand out. BankUnited’s leadership team has lived through a failure and a rebuild—experience that tends to show up in decision-making when conditions get volatile. It also benefits from Florida’s demographic momentum, while maintaining a broader footprint than the bank that once lived and died on one overheated housing market. And compared with institutions that have carried legacy problems from past cycles, BankUnited has presented itself as cleaner and more deliberate in its growth.

Still, the Florida advantage cuts both ways. Population growth, retiree wealth, and the absence of state income tax are real tailwinds. But hurricanes, climate-related concerns, and the state’s long history of real estate boom-and-bust cycles are not theoretical risks. They’re part of the price of doing business in one of the most attractive banking markets in America.

XI. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

BankUnited’s arc—from a spectacular, headline-grabbing failure to a steadier, more disciplined regional bank—offers a handful of lessons that travel well beyond Florida and well beyond banking. If you’re an investor, an operator, or a regulator, the takeaway isn’t “never take risk.” It’s “know which risks you’re really taking, and what incentives you’re baking into the system.”

The Spectacular Failure Lesson: Culture Eats Strategy

The original BankUnited did have a strategy: ride Florida real estate. But it was culture that turned that strategy into a death spiral. When pay and promotions reward volume over credit quality, when the internal mindset becomes “make the loan as long as the borrower had a pulse,” the ending is mostly written. Culture is how thousands of micro-decisions get made—what gets waved through, what gets questioned, what gets escalated, what gets ignored. In the rebuild, BankUnited didn’t just change its loan mix; it made a point of changing the internal defaults, with underwriting discipline and institutional memory replacing growth-at-any-cost.

Private Equity Opportunism: Profiting from Crisis

The Kanas-led consortium showed how sophisticated investors can make money in a crisis by understanding not just assets, but the rules of the game. The FDIC’s loss-sharing arrangement dramatically reduced downside risk on a toxic legacy portfolio while leaving meaningful upside if the franchise stabilized. Pair that with fresh capital and an operator who knew how to run a bank, and you get an unusually asymmetric bet. It’s a playbook that shows up in different forms whenever governments need private capital to help clean up systemic messes.

The FDIC Loss-Sharing Playbook

The loss-share structure worked because it served both sides’ objectives. The FDIC wanted to reduce the ultimate cost of a failure and avoid the disruption of a straight liquidation. The new owners wanted a viable bank, not years of being buried in workouts. With the FDIC absorbing most of the legacy losses, the new BankUnited could focus on rebuilding a functioning franchise—keeping branches open, protecting depositors, and preserving jobs along the way.

But the criticism never really goes away: moral hazard. If crisis-era deals are too generous, do they quietly encourage the next cycle of bad behavior by suggesting there will be a backstop? That tension—between pragmatic crisis resolution and discouraging future excess—is still at the heart of banking regulation debates.

Leadership Matters

John Kanas was not interchangeable. His decades-long run at North Fork, and the credibility that came with it, mattered to everyone involved. Regulators needed to believe the bank could be run responsibly. Investors needed to believe the turnaround could be executed quickly. Counterparties and customers needed to believe the name on the door meant something again. In crisis situations, capital is important—but judgment and trust are often the true scarce resources.

Regional Banking Fundamentals

BankUnited’s post-crisis success also reinforces the boring truths of banking: build deposits through relationships, not just pricing; underwrite with discipline; keep capital strong; and stick to markets and customer types you actually understand. These ideas sound basic—until you watch how easily they get abandoned in a boom.

The Challenge of Growth

A rebuilt bank still has to grow. The lesson here is that growth is not the same thing as progress. BankUnited expanded into New York and beyond, but it also showed a willingness to walk away when pricing didn’t make sense—passing on dozens of potential acquisitions rather than forcing a deal. After 2009, that restraint wasn’t a footnote. It was the strategy.

Capital Allocation Discipline

Finally, there’s capital allocation. BankUnited has returned capital through dividends and buybacks while maintaining strong capital ratios. The signal in that balance is simple: confidence, but not complacency. Not hoarding capital out of fear, and not stretching the balance sheet just to juice short-term returns. In a business where the downside can be fatal, that maturity is a competitive advantage of its own.

XII. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

If you want to understand where BankUnited can win—and where it’s basically stuck playing the same game as everyone else—it helps to get out of the quarterly noise and use two clean lenses: Porter’s Five Forces for industry structure, and Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers for durable advantage.

Porter's 5 Forces

Competitive Rivalry: High

Florida is a knife fight of a banking market. The national giants—JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, Wells Fargo—are all there with deep budgets and enormous scale. You’ve also got plenty of regional banks, plus credit unions that compete for the same households and small businesses.

In that environment, differentiation is mostly about service and relationships. Those matter, but they’re hard to defend because they can disappear the moment a good banker leaves or a competitor decides to price more aggressively. And when rates rise, deposit pricing turns into a bidding war. BankUnited’s status as the largest independent bank headquartered in Florida helps, but it doesn’t make the competition any less relentless.

Threat of New Entrants: Moderate

Starting a new bank the traditional way is tough. Charters are hard to get, regulators expect serious capital, and the economics aren’t friendly to under-resourced players.

But “new entrants” today don’t always look like banks. Fintech firms can pick off profitable product lines—payments, consumer lending, certain deposit-like products—without building branches. Still, the core of what BankUnited leans on, commercial banking relationships, is harder to replicate quickly. Those are built over years, not acquired with an app download.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers (Depositors): Moderate to High

In banking, your “suppliers” are depositors. And depositors have options. When rates go up, people can move money into money market funds, Treasury bills, or the bank down the street offering a better deal. In 2023, the industry got a blunt reminder of how fast those moves can happen.

BankUnited’s relationship-driven approach helps make deposits stickier, but it doesn’t exempt the bank from market reality. And while wholesale funding like Federal Home Loan Bank advances can fill gaps, it comes with costs and its own risks. Deposits are still the lifeblood, and customers know it.

Bargaining Power of Buyers (Borrowers): Moderate

Borrowers have become better shoppers. Commercial clients compare rates, push on terms, and aren’t shy about moving business if the value isn’t there.

BankUnited’s pitch is that it can combine community-bank responsiveness with larger-bank capabilities. When that’s true in practice—fast decisions, good service, sophisticated products—it’s meaningful. But it’s not a one-time positioning statement. It’s something the organization has to earn over and over again.

Threat of Substitutes: Growing

Banks are no longer the only place to get credit or move money. Private credit funds and other non-bank lenders can compete aggressively, and larger companies can bypass banks entirely by going to the capital markets. Payments—the historical gateway drug to a banking relationship—also face pressure from companies like Stripe, Square, and PayPal.

That said, the threat isn’t uniform. Some areas, like commercial real estate lending (a BankUnited strength), are still relatively insulated compared to consumer-facing products where fintech has been more disruptive.

Hamilton's 7 Powers

1. Scale Economies: Limited

Scale helps—especially in spreading technology and compliance costs—but it doesn’t create software-like winner-take-all economics. A bank ten times larger doesn’t automatically have ten times better unit economics. In banking, scale is useful, not decisive.

2. Network Effects: Minimal

Traditional deposit-taking and lending don’t get stronger just because more people use the same bank. Network effects exist in payments networks like Visa and Mastercard, not in most regional banking franchises.

3. Counter-Positioning: Not Applicable

BankUnited isn’t running a disruptive model that incumbents can’t copy without blowing up their own economics. It’s competing inside the traditional banking playbook—just trying to execute it better.

4. Switching Costs: Moderate

For operating accounts, treasury management, and lending facilities, switching can be painful. There’s paperwork, onboarding, new relationship building, and operational risk for the customer.

But for rate-sensitive deposits, switching costs are basically nothing. If someone is there for the yield, they can leave for the yield.

5. Branding: Moderate

“BankUnited” is an unusual brand because it comes with a real narrative. There’s credibility in having survived a catastrophe and rebuilt with discipline—but the original failure is also part of the name’s history.

Brand strength is meaningfully higher in South Florida, where the bank is known. Nationally, it doesn’t have the automatic recognition of the mega-banks.

6. Cornered Resource: Limited

Florida is a great banking market, but it’s not exclusive. Plenty of competitors can serve it. BankUnited’s experienced management team is an asset, but people can retire, move on, or get recruited away. It’s valuable, but not permanently ownable.

7. Process Power: Strong (Relatively)

This is the closest thing BankUnited has to a moat. The bank’s credit culture—shaped by direct experience with catastrophic failure—creates a kind of institutional discipline that’s hard to manufacture. Many banks talk about underwriting standards; fewer have the scars that make those standards non-negotiable.

Verdict

BankUnited’s advantages are real but modest. Its best edge is process power—credit discipline—plus the tailwinds of operating in Florida. But banking remains a commodity business where sustainable competitive advantage is rare, and the gap between “fine” and “fatal” is often just execution and risk management.

XIII. Bull vs. Bear Case

The Bull Case

Florida Demographic Tailwinds

Florida keeps attracting people, businesses, and capital. No state income tax, warm weather, and a lower cost structure than places like California and much of the Northeast continue to drive migration. For a Florida-headquartered bank, that’s the kind of steady backdrop that can translate into long-run loan demand and deposit growth.

Clean Balance Sheet with Conservative Underwriting

BankUnited came through the 2023 regional banking panic without the kind of hangovers that hurt some peers. It didn’t have to explain away a sudden balance-sheet transformation or patch over legacy issues. The post-2009 bias toward conservative risk management showed up when the system got shaky again—and that matters in a business where confidence is oxygen.

Strong Credit Culture Institutionalized

A key difference in the modern BankUnited is that it built its current loan book under its own rules, not by inheriting a pile of distressed assets from a failed competitor and hoping workouts go well. The institutional memory of what happens when credit discipline slips acts like a guardrail: it doesn’t eliminate risk, but it raises the bar for taking it.

Efficient Operator

BankUnited has generally run with a focus on expense discipline while still expanding the franchise. In a world where deposit costs can jump quickly and fee income can be volatile, operating efficiency is one of the few levers management can consistently control—and it can be the difference between “fine” and “fragile” in a tougher cycle.

Potential M&A Target

With a clean franchise, exposure to attractive markets, and a size that’s digestible for larger players, BankUnited could be appealing to a bigger regional or national bank that wants a stronger foothold in Florida. In that scenario, a takeout premium becomes a source of upside that doesn’t require heroic organic growth.

Management Team with Crisis Experience

Rajinder Singh and the senior team have operated through multiple stress events: the legacy of the 2009 failure, the pandemic shock, and the 2023 confidence crisis. That kind of judgment tends to show up in small decisions made early—before problems become headlines.

The Bear Case

Regional Banking Structural Headwinds

Banking is getting harder for mid-sized players. Fintech competition, persistent pressure on deposit pricing, rising compliance costs, and the continuing shift to digital-first customer behavior all squeeze the traditional regional bank model. Scale increasingly buys you better technology and more efficiency, and BankUnited simply can’t spend like the largest institutions.

CRE Concentration Risk

Commercial real estate is a real risk category in the post-pandemic economy, especially anything tied to office demand. BankUnited’s CRE book leans more toward multi-family than office, which helps, but it doesn’t make the bank immune. A broad CRE downturn can pressure collateral values, refinancing activity, and credit performance all at once.

Florida Concentration Risk

Even with meaningful business in New York and other markets, Florida remains the center of gravity. That brings tailwinds—but also unavoidable concentration risk: hurricanes, climate-related uncertainty, and Florida’s long history of boom-and-bust real estate cycles. You can diversify around the edges; you can’t diversify away the core.

Limited Scale vs. National Competitors

Against the money-center banks, BankUnited can’t match the combination of technology budgets, product breadth, and geographic diversification. That caps which customer segments it can win, and it raises the execution burden: the bank has to be sharper in its niches because it can’t be everything to everyone.

Deposit Franchise Vulnerability

The 2023 crisis was a blunt reminder that deposits can move faster than most management teams want to believe. BankUnited’s relationship-first strategy provides some insulation, but the structural vulnerability remains: in a digital world, money can leave in days, not months.

No Sustainable Competitive Moat

The earlier 7 Powers lens points to a hard truth: BankUnited’s advantages are mostly execution-based, not structural. This is a commodity business. That means the bar isn’t “be good.” It’s “be excellent, constantly,” just to generate acceptable returns across cycles.

Historical Failure Reminder

The original BankUnited is also a warning label. It proves that a bank can look successful right up until it isn’t—and that culture can drift. Investors don’t get to set credit discipline on autopilot. They have to watch for the early signals that incentives are shifting, standards are loosening, or growth is getting celebrated a little too loudly.

Key Metrics to Watch

For investors monitoring BankUnited, a few metrics do the best job of cutting through the noise:

-

Net Interest Margin (NIM): The core spread between what the bank earns and what it pays. Sustained compression often signals deposit competition and weaker profitability; sustained expansion suggests better pricing and balance sheet positioning.

-

Non-Performing Loans (NPL) Ratio and Charge-Offs: This is the reality check on underwriting. Rising NPLs or charge-offs usually show stress before it shows up in earnings narratives.

-

Deposit Cost and Composition: Not just how expensive deposits are, but what kind they are—relationship-based operating balances versus rate-sensitive money that can leave quickly.

Together, these three measures track the core drivers of a bank’s success: earning power, credit quality, and funding stability. If they stay healthy, the story tends to stay intact. If they start moving the wrong way, the plot changes fast.

XIV. Epilogue: What the Future Holds

BankUnited now sits at the same crossroads facing almost every regional bank in America. The menu of choices is familiar: get bigger through acquisitions, sell to a larger player, or stay focused and try to win through discipline rather than scale.

The M&A Question

One of the most consistent traits of the post-2009 BankUnited has been the willingness to walk away. Management has passed on dozens of deals that didn’t clear its return thresholds. That restraint is a feature, not a bug—especially for a bank whose original version died from chasing the wrong kind of growth.

But the industry keeps pushing in the other direction. Technology spending is relentless. Compliance costs don’t scale down. And in a crowded market, size can mean better efficiency and a stronger competitive stance. So the question becomes less “should BankUnited do M&A?” and more “can it find the right M&A at the right price?” If not, the other possibility is obvious: BankUnited becomes the acquired, not the acquirer.

It’s not hard to see why a larger regional or national bank might be interested. BankUnited has a clean franchise and operates in attractive markets, especially Florida. For shareholders, a takeout at a premium could be a straightforward path to strong returns.

Climate and Florida

Any long-term view of BankUnited has to reckon with Florida’s climate risk. Rising sea levels, the potential for more intense hurricanes, and mounting insurance costs are not abstract concerns—they’re pressures that can filter into property values, construction decisions, and household budgets over time.

And because Florida remains the center of gravity for the franchise, these risks can’t be diversified away inside the current model. They’re simply part of the bargain: Florida’s growth tailwinds, paired with Florida’s long-run environmental and insurance headwinds.

Technology Transformation

Banking is also being reshaped by technology in ways that won’t neatly reverse. The core question isn’t whether BankUnited will “go digital.” It’s whether a traditional bank can keep competing as fintechs and big tech keep unbundling pieces of the relationship.

The answer likely depends on who you’re serving. Relationship banking can remain durable with sophisticated commercial clients who value responsiveness, judgment, and a real human decision-maker. But consumer and small business banking face genuine disruption as customers get more comfortable choosing convenience and price over a branch and a familiar name.

Regulatory Environment

The regulatory aftershocks from 2023 will shape the next decade for regionals. Stricter capital expectations, long-term debt requirements, and more intensive supervision above certain size thresholds create real costs—but they also raise barriers.

BankUnited’s position relative to those thresholds could turn out to be either a strategic advantage or a constraint, depending on how the rules evolve and where the bank wants to land on the size spectrum.

Generational Question

Then there’s the customer question that doesn’t show up cleanly in quarterly filings: will younger customers choose regional banks at all? The answer determines whether institutions like BankUnited are building a franchise that endures—or simply managing a book of relationships that ages out over time.

BankUnited’s relationship-first approach can resonate with business owners and commercial clients. But in consumer banking, generational change is real, and loyalty is thinner. Winning the next cohort may require new distribution, new product expectations, and a different kind of brand presence than what worked historically.

BankUnited's Specific Path

The most plausible near-term path is the least cinematic: steady execution. Under Raj Singh, BankUnited is likely to keep pursuing measured growth, keep credit discipline tight, and return capital to shareholders. It has already proven it can operate without the FDIC-era backstop, navigate the pandemic shock, and stay standing through the 2023 confidence crisis.

The more dramatic outcomes are still on the table—a transformative acquisition, a sale to a larger competitor, or a credit event driven by a broader commercial real estate downturn. But those are scenarios, not forecasts. The best approach is to underwrite the base case while staying alert to tail risks on either side.

Final Reflection

BankUnited’s story is, at its core, a story about consequences and redemption—and about the boring truth that in banking, culture and discipline matter more than growth.

The failure in 2009 embedded crisis memory into the institution’s DNA. The rebuilt bank is shaped by what happens when underwriting breaks, when concentration risk becomes destiny, and when incentives prioritize volume over quality. That memory is the foundation for everything that followed.

The resurrection itself was extraordinary: from the largest bank failure of 2009 to a disciplined regional franchise in under two years. John Kanas and the private equity consortium saw opportunity where others saw only wreckage, and they paired operational expertise, fresh capital, and a government partnership to produce remarkable outcomes.

But the story also carries a warning. The 2023 regional banking turmoil showed that even with stress tests and modern supervision, bank runs can form fast. BankUnited made it through, yet the episode reinforced the fragility at the heart of the business model: borrowing short, lending long, and depending—always—on confidence.

For investors, that’s the frame. BankUnited has favorable Florida demographics, an experienced leadership team, and a credit culture built around hard-earned lessons. But it’s still a commodity business in a sector with structural headwinds. Acceptable returns don’t come from having a moat; they come from executing well, year after year.

The ghost of the old BankUnited is the reminder: in banking, success is never permanent. The story continues.

XV. Further Reading

If you want to go deeper on the forces that shaped BankUnited—housing euphoria, regulatory blind spots, and the crisis-era dealmaking that turned a failed bank into a public company again—here are ten great places to start:

-

"The Big Short" by Michael Lewis — A fast, vivid tour through the mortgage machine and the financial products that helped take down BankUnited, along with hundreds of other institutions.

-

"Too Big to Fail" by Andrew Ross Sorkin — A ground-level look at how decisions got made during the crisis, and why the government ended up blessing unusual resolutions like BankUnited’s.

-

FDIC Failed Bank List & BankUnited Case Study — The official record: what happened, when it happened, and how the FDIC resolved it.

-

BankUnited SEC Filings (10-Ks, Proxy Statements) — The primary source for how BankUnited describes its strategy, risks, performance, and leadership over time.

-

"The House of Dimon" by Patricia Crisafulli — A useful contrast case: leadership and risk management in a very different kind of bank.

-

American Banker coverage of BankUnited (2009-present) — Industry reporting that tracks the turnaround, the strategy shifts, and the competitive context as the bank evolved.

-

"Private Equity at Work" by Eileen Appelbaum — Broader context on private equity in financial services, and the debates around who benefits when crises create once-in-a-generation opportunities.

-

John Kanas interviews and profiles (Wall Street Journal, American Banker) — Insight into the operator at the center of the resurrection, and the thinking behind the playbook.

-

Federal Reserve Bank research on regional banking — Clear, data-driven analysis of how regional banks compete, how regulation shapes outcomes, and why “simple” banking is often anything but.

-

South Florida Business Journal coverage — The local lens: the market dynamics and real estate backdrop that still matter disproportionately for a Florida-headquartered bank.

BankUnited’s story boils down to consequences and redemption—and to a core banking truth that never changes: culture and discipline matter more than growth. Its spectacular failure and unlikely comeback make it one of the defining banking case studies of the 21st century, and one worth understanding if you invest in financial institutions.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music