BGC Group: From Cantor's Ashes to FinTech Powerhouse

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

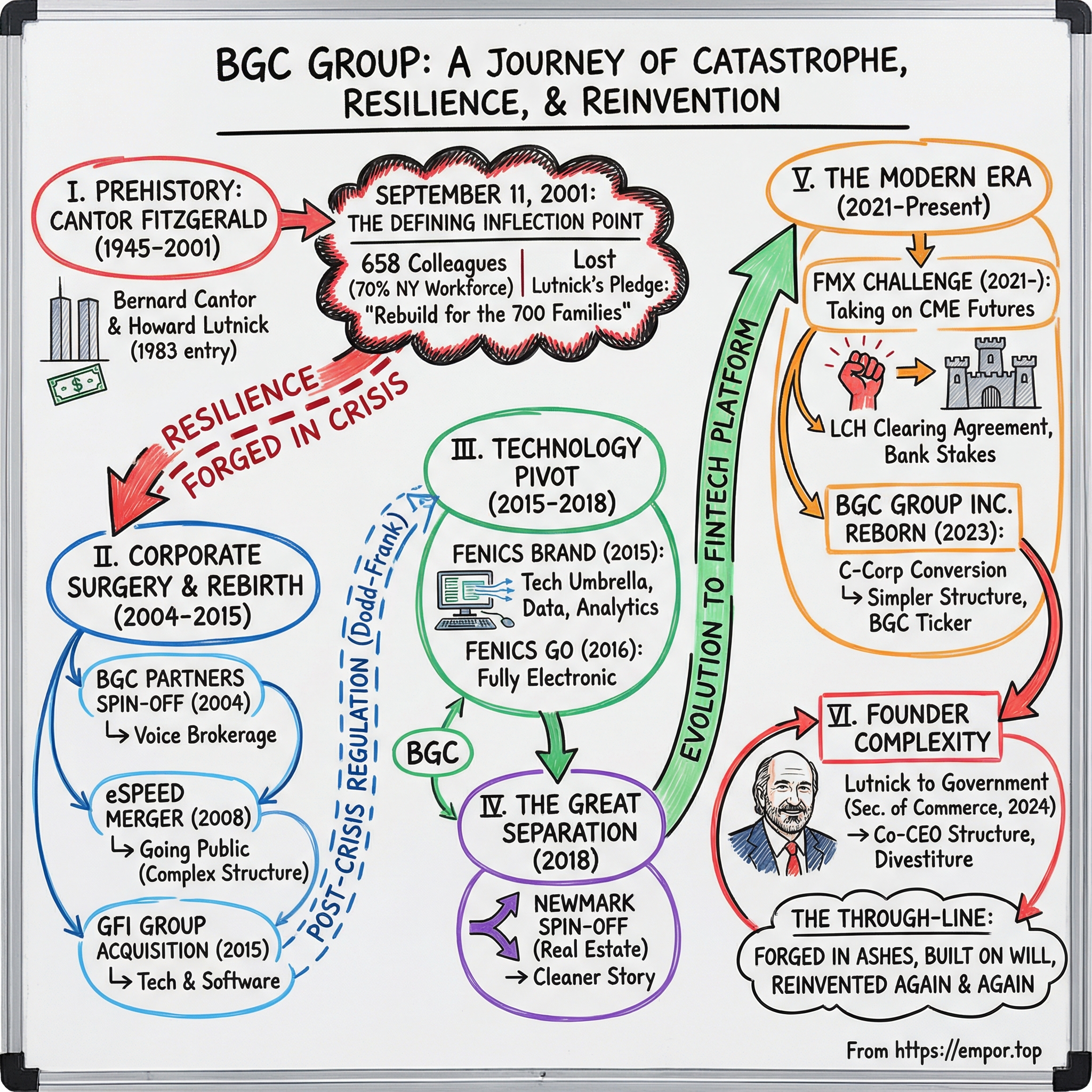

Picture this: it’s a crisp September morning in 2001. A trader is at his desk on the 105th floor of the World Trade Center, coffee in hand, watching Treasury quotes flicker across his screen. Minutes later, that floor is gone. So are 658 colleagues who showed up for work that day.

What comes next is the part that still feels almost impossible to say out loud. This isn’t only a story about loss. It’s a story about a firm that lost nearly 70% of its New York workforce in a single morning—and still managed to keep operating, rebuild, and then reinvent itself so thoroughly that today it looks less like a traditional brokerage and more like a fintech platform with a brokerage attached.

That company is BGC Group. It has grown into a global marketplace spanning fixed income, foreign exchange, energy, commodities, shipping, and equities. It employs more than 4,000 people worldwide, generates over $2.25 billion in revenue, and carries a market capitalization around $4.5 billion. And in a move that tells you exactly how ambitious this evolution has become, it has also launched the FMX Futures Exchange—aimed straight at the U.S. interest rate futures market long dominated by CME Group.

So the question driving this story is simple to ask and hard to explain: how does a company born out of Wall Street’s darkest hour become a technology-first disruptor in a corner of finance that still runs on phones, relationships, and human judgment?

The answer runs through a few big chapters. There’s tragedy, yes—but also corporate surgery: carving businesses apart, spinning pieces out, and constantly reshaping the structure. There’s regulation: the post-crisis push toward electronic trading that both threatened the old model and handed BGC a roadmap to the next one. And there’s deal-making: a steady drumbeat of acquisitions and expansions designed to build breadth, liquidity, and relevance.

Then there’s the human center of gravity: Howard Lutnick. He’s been praised as a visionary and a philanthropist, and criticized for compensation practices that have ranked among the highest on Wall Street. He’s also the connective tissue across a web of related entities—an arrangement that has created real strategic flexibility, and real governance discomfort.

Three themes will keep showing up as we go. First, technology as a survival mechanism—how systems and redundancy mattered when the physical headquarters vanished. Second, the art (and mess) of separation—splitting voice brokerage, real estate, and technology into distinct public stories. Third, founder complexity—what it means to have one leader shaping three interconnected businesses for decades, and what happens when that leader steps into government service.

And if you’re coming at this as an investor, that tension is the point. BGC is a legacy brokerage business racing to become a higher-margin, more recurring, technology-led platform—while carrying a corporate structure that makes plenty of institutions hesitate. The bet is that the transformation outruns the secular decline in voice brokerage, and that data, software, and electronic execution eventually become the core of the valuation.

Let’s start where it all began—long before BGC had a ticker symbol, when Cantor Fitzgerald was building an empire in the bond markets, and Howard Lutnick was still a young partner on the rise.

II. Prehistory: Cantor Fitzgerald & Howard Lutnick

Bernard Gerald Cantor was born in the Bronx on December 17, 1916, the son of Jewish immigrants from Belarus—Rose (née Delson) and Julius Cantor. Before he was fifteen, he was already hustling concessions at Yankee Stadium for fans who came to see Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig. Even then, he was thinking like an operator: he worked only the doubleheaders because, as he put it, “you sold more between games.”

After studying law and finance at New York University from 1935 to 1937, Cantor became a securities analyst on Wall Street. He served in the U.S. Army in the South Pacific during World War II, and when he came home he started a firm called B.G. Cantor and Company. That business would later become Cantor Fitzgerald L.P.—a New York partnership that grew into one of the most important institutional brokers of U.S. government securities in the country.

Cantor Fitzgerald was formally established in 1945 by Bernard Gerald Cantor and John Fitzgerald. Over the decades, the firm built its reputation on a simple idea: use technology to make the bond market faster, more transparent, and more scalable. It became the world’s first electronic marketplace for U.S. government securities in 1972. In 1983, it became the first to offer worldwide screen-based brokerage services in those same securities—an early signal that this was not going to be a purely phone-and-relationship shop.

To understand why that mattered, you have to understand the interdealer broker model. Fixed income markets didn’t run on a centralized exchange. They ran on networks—dealers trading with dealers, constantly managing risk in credit, interest rates, and currencies. In that environment, interdealer brokers (IDBs) served as neutral intermediaries: they helped banks and broker-dealers find liquidity, discover pricing, and most importantly, preserve anonymity.

An IDB’s value shows up in a moment of vulnerability. Imagine a large investment bank holding a billion dollars in Treasury bonds it wants to sell. If it goes directly to another bank, it risks broadcasting its intentions and pushing the market against itself. With an IDB, the bank can work through a broker who finds the other side without revealing identities until the trade is done. The broker earns a commission measured in basis points—tiny slices that become meaningful when you’re touching enormous volume.

This was the world Cantor built. And in 1983, it’s where Howard Lutnick walked in.

Howard William Lutnick was born on July 14, 1961, on Long Island, to Solomon and Jane Lutnick. His father was a history professor; his mother was a sculptor and painter. He grew up in Jericho, New York, the middle of three children, in a Jewish household. In high school, his mother died of lymphoma. He enrolled at Haverford College in 1979, and during his freshman year, his father died of cancer. Haverford’s president and dean offered Lutnick a full scholarship to finish his education—an intervention he never forgot. He later became one of the school’s largest donors, and graduated in 1983 with a degree in economics.

That early double loss didn’t just shape him personally; it helped form the leadership reflex he would become known for later. Institutions can step in when life collapses. And rebuilding—real rebuilding—often means outworking what seems possible.

Lutnick joined Cantor Fitzgerald in 1983 under the mentorship of B. Gerald Cantor, and his rise was fast. In 1991, at just 29, Lutnick was appointed President and CEO. Five years later, he became Chairman.

But the succession wasn’t clean. As Cantor’s health declined in 1995, Lutnick became embroiled in a contentious legal battle with Cantor’s wife, Iris, over control and succession. He filed suit in Delaware court, claiming Cantor lacked sufficient mental capacity to make decisions. A settlement ultimately gave Lutnick management control, and after Cantor died in 1996, Lutnick was appointed chairman.

Once in charge, Lutnick pushed the firm harder into technology. He invested heavily in what became eSpeed, an electronic trading platform that helped drag an old voice market into the screen era. The shift accelerated in March 1999 when Cantor introduced eSpeed, and later that year the company spun it out in a December 1999 public offering.

That bet would end up mattering in a way nobody could have predicted. On September 11, 2001, when physical infrastructure would vanish, the firm’s distributed computing systems and New Jersey data centers kept trading operations alive. At Cantor, technology wasn’t just a growth engine. It was a continuity plan.

By 2001, Cantor Fitzgerald had become a dominant force in the bond market, with more than 70% of all Treasury securities traded through the company. The firm occupied floors 101 through 105 of the North Tower—“top of the world,” as it was often called.

III. September 11, 2001: The Defining Inflection Point

The morning of September 11, 2001, started like any other for Cantor Fitzgerald’s New York team. Nearly 1,000 employees worked out of the firm’s headquarters on floors 101 through 105 of 1 World Trade Center—“top of the world,” literally.

Howard Lutnick, Cantor’s CEO, wasn’t there. He was doing something painfully ordinary: taking his son Kyle to his first day of kindergarten. Later, he would describe standing outside the school at 8:46 a.m., taking a photo—his son with a backpack, hair tucked behind his ears—and thinking of it as “the last minute of my old life.” The new one began immediately, and it included the loss of his brother, Gary.

American Airlines Flight 11 hit the North Tower below Cantor’s offices. The impact zone severed escape routes; smoke, fire, and debris made the stairwells impassable. Everyone who had reported to work that morning in those Cantor floors was trapped. In total, 658 Cantor Fitzgerald employees who were present that day were killed—the largest loss of life of any single organization in the attacks. Forty-six contractors, food service workers, and visitors in Cantor’s offices were also killed.

The scale of it is hard to hold in your head, even when you say it plainly: 658 out of 960 Cantor employees based in New York were killed or missing—well over two-thirds of the office.

In the immediate aftermath, Lutnick didn’t talk like a man thinking about strategy. He talked like a man trying to survive the next hour. He later described losing his brother, his best friend, and roughly 200 employees he had personally hired. At first, he felt there was no choice but to shut the company down. Cantor had gone from making about a million dollars a day to losing about a million a day.

Two days after the attacks, Lutnick went on national television and broke down in an interview with ABC’s Connie Chung. Through tears, he pledged to take care of the families of those who had died. “There is only one reason to be in business,” he said, “it is because we have to make our company be able to take care of our 700 families… That’s my American dream now.”

And then, almost immediately, came the backlash.

The firm dropped its missing employees from payroll two days after the attacks. For families still clinging to hope, it felt like abandonment. Lutnick became a lightning rod—praised for raw, public grief, and condemned for decisions that looked like cost-cutting at the worst possible moment.

On September 19, Cantor Fitzgerald made a formal commitment: 25% of the firm’s profits for the next five years—profits that otherwise would have gone to partners—would be distributed to the families. The firm also committed to ten years of health care coverage for the families of its 658 former Cantor Fitzgerald, eSpeed, and TradeSpark employees. By 2006, Cantor said it had fulfilled that promise, paying $180 million, plus an additional $17 million from a relief fund run by Lutnick’s sister, Edie.

Keeping the business alive required something close to the impossible. Cantor rebuilt its infrastructure and eventually relocated its headquarters to Midtown Manhattan. Its London office—built up since the mid-1980s and about 700 people strong—became a lifeline, helping keep the bond brokerage functioning in the days when New York had been physically erased.

By December 2002, Cantor Fitzgerald had 750 employees in New York again. The firm had survived. But it would never be the same company.

This is the moment that matters for understanding BGC Group, because 9/11 didn’t just wound Cantor; it rewired it. The culture was forged in crisis, and that institutional memory of resilience seeped into everything that came after. Technology went from being a competitive advantage to being existential—distributed systems meant trading could continue even when the headquarters was gone.

And the relationship between the firm and the families of fallen employees became a permanent part of the company’s identity, expressed most visibly through annual Charity Days, when Cantor Fitzgerald and BGC donate 100% of their revenue to charitable causes. Since Charity Day began, it has raised $192 million for charities globally.

It also shaped Lutnick himself. He came out of 9/11 with an almost indomitable purpose: rebuild the firm in honor of the people who died, and support the families left behind. For investors looking at BGC decades later, that history is not just biography—it’s governance and capital allocation context. The company is run by someone who has already lived through the kind of event that destroys institutions. The open question is what that survivor’s mentality produces over the long run: exceptional focus and endurance, or a tendency toward aggressive, controversial decisions made under the conviction that the only acceptable outcome is winning.

IV. The Birth of BGC Partners: Corporate Surgery

By 2004, Cantor Fitzgerald had rebuilt enough to think about something other than survival. It could finally do what Wall Street firms do when they want to grow without tripping over their own complexity: reorganize.

Inside Cantor, the voice brokerage business had become a real franchise, especially in London and across Europe. But it lived by different rules than Cantor’s other operations—things like institutional equity trading, investment banking, and the eSpeed electronic platform. Voice brokerage was people-heavy and relationship-driven. It expanded by opening offices, recruiting teams, and living on reputation and service. Electronic trading, on the other hand, was increasingly a technology and scale game. Keeping both under one roof made the story harder to manage, harder to report cleanly, and harder to fund the way each side needed.

So in August 2004, Cantor Fitzgerald announced that—effective October 1—it would spin off its global voice brokerage business to form BGC Partners, L.P. The new firm would focus on wholesale fixed income, interest rates, foreign exchange, and derivatives markets, offering pricing and execution, along with access to electronic trading services and technology support from eSpeed. It would launch as a private partnership, with offices spanning London, New York, Tokyo, Hong Kong, Singapore, Geneva, and Milan, and more than 400 brokers across Europe, the U.S., and Asia.

The name was a deliberate tether to Cantor’s roots: BGC stood for Bernard Gerald Cantor.

The push for the carve-out came from inside the business. In 2004, Lee Amaitis and Shaun Lynn approached Lutnick about separating what had become a largely London-based interdealer operation. Lutnick and his partners agreed—Cantor would effectively split in two, with Cantor Fitzgerald retaining a majority stake in the new brokerage.

The logic was simple and powerful. A voice brokerage doesn’t scale like software. It scales through talent, relationships, and boots-on-the-ground expansion. Spinning it out meant more focused management, clearer financials, and, eventually, a cleaner path to tapping public-market capital.

Cantor had historically run with little debt. But in early 2005, it borrowed about $380 million—and BGC, now armed for expansion, moved fast. That May, it acquired Maxcor Financial Group, the parent of interdealer broker Euro Brokers. Euro Brokers had been based in the South Tower on 9/11 and had lost 60 people. It was a strategically meaningful deal, and an emotionally loaded one too—linking two firms marked by the same catastrophe.

From the start, BGC’s model was a hybrid: high-touch voice and hybrid execution where it mattered, alongside electronic execution across a widening set of products. It brokered trades for banks, broker-dealers, and investment banks across fixed income, foreign exchange, equity derivatives, credit derivatives, futures, structured products, and more—supported by market data products in selected instruments.

But BGC was unusual in another way, and it would become impossible for investors to ignore later: the ownership and control structure. Cantor Fitzgerald kept a controlling stake, and Howard Lutnick served as Chairman and CEO across both worlds. That tight linkage created strategic flexibility—but it also baked in a web of related-party relationships that would become a recurring theme in BGC’s public story, and a recurring concern for governance-focused shareholders.

V. Going Public & The Cantor Entanglement (2008)

BGC’s path to the public markets was anything but standard. Instead of a clean, traditional IPO roadshow, it took a shortcut that felt very Cantor: a reverse merger with eSpeed, the electronic trading platform Cantor had spun out in 1999—and the piece of the empire whose technology backbone had helped the firm function after 9/11.

In March 2008, eSpeed announced that its shareholders had approved a merger with BGC Partners. At a special meeting, holders representing about 99.5% of eSpeed’s voting power approved the deal, with closing expected around April 1, 2008.

So in 2008, BGC became a public company by merging into eSpeed. And it happened right as the ground under global finance was starting to liquefy. The financial crisis would soon drive enormous volatility in fixed income markets—conditions that can be good for brokers because activity spikes—but it also put a harsh spotlight on counterparty risk and the stability of the institutions BGC depended on.

Then there was the structure. If the business was hard to explain, the ownership was harder.

The post-merger setup was famously complex: different classes of shares, LP units, and distribution rights, with Cantor and insiders holding most of the real control. Economically, the rough split looked like this: Cantor owned around 19%, BGC executives and employees held about 35%, and the public held roughly 48%. But for everyday shareholders, the key point wasn’t the percentages—it was the voting. Public investors owned the “A” shares, and those votes didn’t carry much weight compared to the control embedded elsewhere in the structure.

That complexity cut both ways. On one hand, it signaled alignment: Cantor and management had meaningful skin in the game. On the other, it was a controlled-company arrangement in practice, with public shareholders along for the ride on governance.

And the entanglement wasn’t theoretical. Lutnick had effectively split Cantor in 2004, but he didn’t step away from either side. Cantor continued to handle large trades through its stock and bond trading desks, while BGC built out the broker-driven interdealer franchise. Several senior executives wore hats in both organizations, and Howard Lutnick remained chairman and CEO of both.

For investors, the pitch was compelling: a global wholesale brokerage business with deep relationships, a hybrid voice-and-electronic model, and infrastructure with real staying power.

The footnotes were just as clear: related-party transactions with Cantor, governance that concentrated control, and the long-term question hanging over every people-heavy brokerage—what happens as markets keep migrating from humans on phones to machines on screens?

VI. Building the Brokerage Empire (2008–2015)

After the crisis, BGC found itself riding a wave that cut in two directions at once.

On the surface, volatility was good business. When markets whip around, dealers trade more, hedge more, and call brokers more. But the real story of the post-crisis era wasn’t just volume—it was rules. Washington and regulators across the world were determined to drag opaque, dealer-to-dealer derivatives trading into the light. The Dodd-Frank Act in 2010 pushed the market toward central clearing and more standardized execution, including trading on swap execution facilities, or SEFs.

For an interdealer broker, that shift was both an invitation and a threat. If the market moved from private phone calls to regulated platforms, the winners would be the firms that could become the platform.

BGC moved early. In October 2013, it began operating as a SEF, putting itself near the front of the pack as derivatives trading started migrating from bilateral deals to more structured, regulated venues.

At the same time, BGC did what consolidators do in industries where scale and coverage matter: it went shopping. It expanded product lines, added geographic reach, and rolled up competitors. In 2014, it acquired R.P. Martin, a U.K.-based interdealer broker. But the defining move of this era was much bigger—and much messier.

The GFI Group acquisition became the largest deal in BGC’s history, and it didn’t happen politely. In July 2014, CME Group announced it had agreed to buy GFI at $4.55 a share. BGC wasn’t interested in watching a rival get absorbed by an exchange. In October 2014, BGC launched a hostile bid—about $675 million—to take GFI for itself. A bidding war followed. CME raised its offer to $5.85 a share in cash and stock. BGC countered with an all-cash $6.10 a share offer. By the end of January 2015, GFI shareholders rejected CME’s proposal, and in February GFI’s board agreed to accept BGC’s tender offer.

By February 2015, BGC announced it had successfully completed the tender offer for the GFI shares it didn’t already own. Later, it completed the acquisition of the remaining stake in GFI Group.

This wasn’t just about adding brokers. GFI brought technology and software that fit perfectly with where the market was headed. Years earlier, in 2001, GFI had acquired FX analytical software firm FENICS Software Ltd. And in 2008, it acquired Trayport Ltd, a major provider of trading software for OTC energy products and other markets. With an agreement in place to sell Trayport to ICE for $650 million, BGC recouped the majority of what it paid for GFI—and still kept the Fenics business.

Alongside all of this financial-market expansion, BGC made a move that seemed, at first glance, almost random: commercial real estate. In October 2011, BGC completed its acquisition of Newmark Knight Frank, a major U.S. commercial real estate brokerage and advisory firm. In March 2012, it acquired the assets of Grubb & Ellis Company, another long-established real estate name. The result was a meaningful commercial real estate platform sitting inside a wholesale financial brokerage.

It was an odd pairing—and it wouldn’t last forever. But in the moment, the logic was straightforward: trading revenue is cyclical and volatility-dependent. Real estate brokerage and services promised a different rhythm, one that could smooth the business and create another engine for growth.

VII. The Technology Pivot: From Broker to FinTech (2015–2018)

By the mid-2010s, BGC’s leadership could see where the industry was headed. Voice broking—humans on phones, working relationships and discretion—wasn’t going to disappear overnight. But it was under steady, secular pressure as more products moved to screens, more workflows became automated, and more regulators demanded transparent, auditable execution.

So BGC needed a new identity. Not a brokerage firm that happened to own some technology, but a technology platform that could still deploy brokers when the market demanded high-touch liquidity.

The banner for that shift was Fenics. In the fall of 2015, BGC expanded the FENICS brand into the umbrella for its technology business—tying together pricing and analytics, execution tools, risk mitigation and regulatory advisory services, plus market data and SaaS offerings. Fenics was positioned to support BGC’s regulated venues and workflows—its SEF, DCM, and MTF—and to help customers navigate global rulemaking. More than that, it was framed as the gateway: the layer through which BGC’s network of participants would access markets around the world.

In 2016, BGC rolled out a concrete example of what “Fenics” was supposed to mean in practice: Fenics GO (Global Options), an electronic trading and market data platform focused on exchange-listed futures and options. The initial launch targeted Eurex-listed Euro Stoxx 50 Index Options and related Delta 1 strategies, with liquidity support from firms including Optiver, IMC, and Maven Securities. The pitch was simple and modern: let traders access liquidity electronically and anonymously.

Under the hood, Fenics was also becoming a data engine. Fenics Market Data drew information directly from BGC’s global operations—electronic and voice broking, pricing systems, and analytics—and packaged it with proprietary datasets. The company emphasized round-the-clock coverage supported by quantitative analysts, data scientists, and data engineers.

The promise wasn’t just “here are yesterday’s prints.” It was full curves and surfaces powered by in-house models and calibrated using executable market observations, plus consolidated streams of quotes, orders, and trades from BGC’s trading platforms. In particular, Fenics aimed to deliver a real-time view of global interest rate markets across both linear and non-linear instruments, pulling from multiple broking brands and liquidity pools.

The market started to notice the shift in narrative. BGC Partners won Risk.net’s inaugural interdealer broker award for balancing its traditional strengths with newer models. It continued to hire senior people from major financial institutions—Bank of America, HSBC, ICAP, and J.P. Morgan—still investing in the legacy franchise. But strategically, Fenics was being built as something more than a product line: an internal champion and organizing principle for BGC’s electronic execution and data businesses.

Even the way BGC talked about “electronic” was part of the messaging. Where some competitors counted a trade as electronic if it merely showed up on a screen at some point, BGC said it only counted transactions executed with no voice component at all. That stricter definition gave management a clean scoreboard, desk by desk, across more than 400 desks globally—and gave investors a metric that mattered, because pure electronic platforms tend to command far higher valuation multiples than traditional brokers.

VIII. The Great Separation: Newmark Spin-Off (2018)

For years, BGC had carried an answer it didn’t love having to explain: yes, the wholesale financial broker also owned a commercial real estate services company.

The real estate push had made sense when it happened. Trading can be cyclical and volatility-driven; a big advisory business tied to office towers and capital markets could smooth the ride. But by 2017, it had become strategically awkward. Investors didn’t know whether to value BGC like an interdealer broker, a tech platform, or a real estate services roll-up. So BGC did what it had learned to do best over the years: separate the stories.

Newmark Group, Inc.—operating as Newmark Knight Frank—went public in 2017. Then, in 2018, BGC completed the full separation. BGC distributed all of its Newmark shares to BGC stockholders via a special pro rata stock dividend. The spin-off became effective at 12:01 a.m. Eastern on November 30, 2018, for BGC stockholders of record as of the close of business on November 23.

The deal was structured to be generally tax-free to BGC stockholders for U.S. federal income tax purposes. And once it was done, it was done: BGC no longer held any shares of Newmark.

On paper, the outcome was exactly what investors usually want. Two cleaner companies. Newmark could be valued like a commercial real estate services peer to firms like CBRE and JLL. BGC could go back to being judged as a wholesale financial services business—one increasingly trying to tell a technology story through Fenics.

But even after the separation, the entanglement didn’t disappear. Howard Lutnick remained Chairman of Newmark and continued as CEO of both Cantor and BGC. Related-party arrangements, including administrative services, continued across the ecosystem.

So for BGC shareholders, the Newmark spin-off was a real step toward simplification—but not the end of the identity question. Was BGC a brokerage firm trying to become a technology company, or a technology company that still needed brokers? The market’s answer to that would go a long way toward determining whether BGC traded on brokerage multiples or fintech multiples.

IX. The FMX Challenge: Taking on CME (2021–2024)

If Fenics was BGC’s argument that it could be more than a broker, FMX was the proof-of-conviction move: build an exchange and go straight at the most entrenched franchise in U.S. markets—CME’s grip on interest rate futures.

In November 2021, BGC Partners announced FMX, a fully electronic marketplace spanning U.S. rates cash and futures. It also announced a Clearing Services Agreement with LCH Ltd, one of the world’s major clearing houses. The pitch was deliberately customer-led: FMX was designed to combine Fenics UST and FMX U.S. Futures on one platform, creating an integrated Treasuries-and-futures workflow with trading and clearing in the same place.

The ambition was clear from the start. This wasn’t “another venue.” It was a direct attempt to create a credible alternative to CME’s interest rate complex, offering market participants a new home for benchmark contracts.

In January 2024, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) granted FMX approval to begin operations. Then, in April 2024, BGC announced that ten global investment banks and market-making firms had taken minority equity stakes in FMX, valuing it at $667 million post-money.

BGC Group named Bank of America, Barclays, Citadel Securities, Citi, Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan, Jump Trading Group, Morgan Stanley, Tower Research Capital, and Wells Fargo as minority equity owners.

FMX officially launched SOFR futures trading on September 23, 2024 at 9:00 p.m. ET, for the trade date of September 24, 2024.

But “taking on CME” is not a slogan—it’s a scale problem. CME had about 98% of on-exchange interest rate derivatives in North America, according to the Futures Industry Association. And it wasn’t sitting still: SOFR futures and options had surged after replacing Eurodollars, with average daily volume up 92% to 5.3 million contracts, alongside record open interest.

So FMX’s wedge wasn’t supposed to be branding or novelty. It was economics. The LCH partnership was central to that: by clearing through LCH, FMX participants could cross-margin the new futures contracts, unlocking margin efficiencies and, in theory, a reason to move flow. As BGC put it, “This is the first US interest rate futures exchange to launch with a fully operational, globally connected, state-of-the-art trading system, along with enormous capital savings driven by the LCH's cross-margin capabilities.”

After SOFR, FMX expanded the contract set. It launched U.S. Treasury futures contracts on May 18, 2025, for trade date Monday, May 19, 2025.

And there were early signs of life. In BGC’s second quarter 2025 results, the company said average daily volume and open interest on FMX Futures Exchange reached record levels during the quarter. It also said SOFR average daily open interest rose 73% sequentially in the second quarter, and that July’s open interest more than doubled from those levels.

For investors, FMX is the cleanest expression of BGC’s risk profile. If it takes meaningful share from CME, the upside is enormous—an exchange franchise can be worth far more than a brokerage. If it doesn’t, BGC still has its core business and its Fenics platform, but it will have spent heavily on technology buildout, regulatory process, and the hard, political work of keeping a multi-owner market structure aligned.

X. The Final Evolution: BGC Group Inc. Reborn (2023)

After years of operating with a structure that even seasoned investors had to diagram on a whiteboard, BGC finally did the thing public markets love most: it simplified.

On Saturday, July 1, 2023, BGC Partners, Inc. completed a corporate conversion into a full C-corporation. Along the way, it rebranded as “BGC Group, Inc.” and changed its Nasdaq ticker to BGC from BGCP.

Howard W. Lutnick, still Chairman and CEO, framed it as a turning point: a move to a simpler, more efficient structure that could broaden the shareholder base and make the company easier to own, understand, and value.

Mechanically, the shift happened through a series of mergers and related transactions that converted BGC Partners and BGC Holdings, L.P., plus certain related entities, from an Up-C structure into a single public holding company. After the conversion, BGC Group became the public parent and successor to BGC Partners, and the former stockholders of BGC Partners and the former limited partners of BGC Holdings participated in the economics of the business through BGC Group.

The practical impact was the point. The old partnership-within-a-public-company setup had long complicated how investors thought about dilution, partner compensation, and voting rights. As a straightforward C-corporation, BGC became easier to model with standard public-company metrics—and, just as importantly, easier to explain.

The financials showed the transformation continuing in parallel. In 2024, the company generated $2.20 billion in revenue, up from $1.97 billion in 2023.

And the mix kept tilting toward technology and recurring-style businesses. Beginning in the second quarter of 2023, BGC renamed “Data, Software, and Post-trade” to “Data, Network, and Post-trade.” That segment’s revenue grew 17.9%, driven by Fenics Market Data and Lucera, its network business.

XI. The Howard Lutnick Factor: Founder Complexity

You can’t really understand BGC without understanding Howard Lutnick. He joined Cantor Fitzgerald in 1983, rose fast, became President and CEO in 1991, and later Chairman. His tenure stretched across three decades of Wall Street history—boom times, the worst day imaginable, and a long, deliberate reinvention of what his companies even were.

9/11 didn’t just scar Cantor. It permanently defined Lutnick in the public eye. In the aftermath, the Cantor Fitzgerald Relief Fund donated $180 million to the families of coworkers who died in the attacks. Lutnick has also personally donated more than $100 million to victims of terrorism, natural disasters, and other emergencies around the world.

The recognition followed. He was named the Financial Times’ Person of the Year in 2001, and Ernst & Young’s United States Entrepreneur of the Year in 2010.

But the same intensity that helped rebuild a firm from the rubble has also made Lutnick a complicated figure for public-market investors. Executive compensation has drawn criticism. And the related-party arrangements between Cantor, BGC, and Newmark have been a persistent governance overhang. Even after simplifications, BGC has still carried a controlled-company feel—where public shareholders can own the stock, but have limited influence over the big decisions and the board that makes them.

Then, in late 2024, Lutnick’s story took a hard turn into politics. He was a fundraiser for Donald Trump’s 2020 and 2024 presidential campaigns and a vocal proponent of Trump’s tariff proposals. In August 2024, he was named co-chair of Trump’s presidential transition team.

BGC later announced that Howard W. Lutnick, Chairman and Chief Executive Officer, was confirmed by the United States Senate as the 41st Secretary of Commerce and, as a result, stepped down as Chairman of the Board and from his executive positions at the Company.

BGC said it expected John Abularrage, Jean-Pierre Aubin, and Sean Windeatt to be named Co-CEOs of BGC effective upon confirmation.

Lutnick also agreed to divest his interests in BGC to comply with U.S. government ethics rules and said he did not expect any arrangement that would involve selling shares on the open market.

For investors, that succession is both risk and opportunity. Risk, because for decades Lutnick has been the central strategist and power center, and his exit removes the person who could force alignment across a complex ecosystem. Opportunity, because his departure could ease long-running related-party and governance concerns—and potentially make the stock investable for institutions that simply wouldn’t touch it before.

XII. The Competitive Landscape & Market Evolution

BGC operates in a market that looks competitive on the surface, but behaves more like an oligopoly underneath. A small group of players control the pipes that connect the world’s biggest dealers—especially in products that don’t trade on a simple, centralized exchange.

The biggest of them is TP ICAP, a U.K. firm listed in London and widely regarded as the largest interdealer broker globally. It spans the major asset classes and plays the same core role BGC does: sit between buyers and sellers in wholesale markets, match liquidity, and keep identities shielded until a trade is done.

TP ICAP’s dominance didn’t happen organically. In 2017, Tullett Prebon and ICAP completed their merger to form TP ICAP, creating a combined heavyweight in interdealer broking.

But the rivalry here isn’t just broker versus broker. The competitive dynamics have shifted in a more existential direction: traditional IDBs like BGC and TP ICAP still fight each other for broker talent and client flow, but the larger threat is electronification—platforms that can cut humans out of the loop entirely.

That’s why, when BGC executives talk about competition, they don’t always point first to TP ICAP. They point to electronic venues like Tradeweb. As one BGC executive put it: “When we sit down on Monday mornings and talk about how to play out the next week, the next month, the next six months, we're looking at the bigger threats from those venues, rather than wondering how we can drag market share from the other brokers. We don't want to win the battle and lose the war.”

Platforms such as Bloomberg, MarketAxess, and Tradeweb have traditionally been thought of as dealer-to-client venues—serving the other side of what used to be a fairly cleanly split fixed income ecosystem. But that line has been getting blurrier, and their models have been evolving in ways that increasingly overlap with what IDBs historically owned.

After 2008, consolidation accelerated as the market matured and the pressure to build scale intensified. Nearly every major provider still standing leaned into aggressive M&A, with the most visible examples being the Tullett Prebon–ICAP deal that created TP ICAP and BGC’s acquisition of GFI Group.

And as execution fees get squeezed, another battleground has grown up alongside trading: data.

IDBs have embraced the idea that their real asset isn’t only commissions—it’s the information embedded in all that flow. Both TP ICAP and BGC leaned into that narrative through explicit rebranding of their data businesses. In April 2021, TP ICAP rebranded its Data & Analytics group as Parameta Solutions, echoing the direction BGC had already been pushing with Fenics Market Data.

XIII. Business Model Deep Dive

By this point in the story, BGC can sound like a lot of things at once: a broker, a data company, a software platform, even an exchange-builder. The cleanest way to understand it is to start with what it actually does every day.

Headquartered in London and New York, BGC Group helps the biggest institutions in the world trade. It provides trade execution and broker-dealer services, plus the clearing, processing, information, and back-office plumbing that makes wholesale markets function. Across more than 200 products—fixed income, interest rate swaps, foreign exchange, equities and equity derivatives, credit derivatives, commodities, futures, and structured products—BGC sits in the middle, connecting liquidity and keeping the workflow moving.

And the customer list tells you why this business can be so durable. It spans the vast majority of the world’s largest banks, broker-dealers, investment banks, trading firms, hedge funds, governments, corporations, and investment firms. In other words: the people who trade size, care about discretion, and can’t afford downtime.

Operationally, BGC now runs on two tracks at the same time. The first is Fenics: the company’s platform for fully electronic execution, market data, and software solutions across multiple asset classes. The second is the legacy engine that still matters—voice brokerage—where brokers and relationships remain the fastest way to find liquidity in complex or less-liquid markets.

The mix has been tilting toward the higher-margin, more scalable parts of the business: electronic execution and data. In the first quarter of 2024, BGC reported record revenue of $578.6 million, up 8.6%, with growth across geographies and across energy, commodities, shipping, rates, and foreign exchange. Total brokerage revenue rose 7.3% year-on-year to $528 million. Rates revenue increased 6.3% to $175.1 million, driven by strength in interest rate derivatives, government bonds, and emerging market rates products.

BGC’s footprint matches its ambition. It employed about 3,991 people globally, with offices across the Americas, Europe, the Middle East, Africa, and Asia-Pacific. Around the most recent data, its market capitalization sat at approximately $3.919 billion.

But the real “model” here isn’t just products and platforms—it’s people.

BGC is a talent business. Brokers are the product. Their relationships, market judgment, and credibility generate the flow that generates the commissions. That creates upside—great teams can scale a franchise quickly—but it also creates a permanent vulnerability. If competitors can recruit those teams away, revenue can move with them. And when markets are hot, compensation can become an arms race.

The other defining feature is that BGC is capital-light compared to banks or exchanges. It generally isn’t taking large principal risk; it’s acting as an intermediary and collecting commissions rather than warehousing big inventories. That can produce attractive returns when volumes and volatility are healthy. But it also means BGC doesn’t have the same built-in shock absorbers that more balance-sheet-heavy financial institutions do. In this business, you live and die by activity, relevance, and the strength of your network.

XIV. Strategic Analysis: Powers and Forces

Porter's Five Forces Analysis:

Threat of New Entrants: MODERATE-LOW. This is not an app-store category. To get into interdealer broking, you need licenses, compliance muscle, credibility with the biggest dealers in the world, and serious investment in trading tech. Those barriers keep most would-be entrants out. Still, fintechs can attack one slice at a time—MarketAxess in credit is a reminder that you don’t have to rebuild the whole stack to take meaningful profit pools.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE. In this business, the “suppliers” are people. Star brokers carry relationships and flow, and they can walk out the door. The same goes for engineers who can build low-latency systems and data products. And in the background, the specialized infrastructure vendors that power modern electronic trading can exert pricing power too.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-HIGH. The buyer base is concentrated: the major banks and large institutional players. They know what they’re worth, they shop aggressively on price, and they increasingly have options. Switching costs can be real in complex products and workflows—but multi-dealer platforms make it easier to route around any single intermediary.

Threat of Substitutes: HIGH. If BGC is the middle, substitutes are everything that tries to remove the middle: direct bank-to-client trading, exchange-traded products, internal crossing networks, and fintech platforms that unbundle one product or workflow and do it cheaper, faster, and more transparently.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH. It’s an oligopoly, but it doesn’t feel gentle. Firms battle for broker talent, fight over volumes, and cut price in commoditized products. Meanwhile, the real contest is a technology arms race: better electronic execution, better data, better tools—because that’s where the margin and the future are.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers:

Network Effects: STRONG. This is the engine. Liquidity venues behave like true two-sided networks: more participants usually means better pricing and tighter markets, which attracts more participants, which deepens the pool again. Then the flywheel tightens: more flow creates better data and analytics, which makes the platform more valuable, which pulls in more flow.

Switching Costs: MODERATE-STRONG. Once a client is wired into a workflow—systems integration, training, compliance processes—it’s inconvenient to rip out. And in voice and hybrid markets, there’s another kind of stickiness: the relationship with the broker who consistently finds you liquidity. But multi-dealer platforms and electronification keep chipping away at that lock-in.

Counter-Positioning: MODERATE. BGC originally counter-positioned against old-school voice brokers by leaning into technology. Now the tables have turned: pure-play fintechs counter-position against brokers by saying, “we don’t need humans at all.” BGC’s response is the hybrid model—the argument that you can marry high-touch liquidity with electronic scale.

Scale Economies: MODERATE. There are real scale advantages in technology and data: the more volume you run through a platform, the more you can amortize systems and infrastructure. But it’s not pure software. Broker-heavy parts of the business don’t scale cleanly, and revenue per employee can swing.

Cornered Resource: MODERATE. BGC’s edge comes from hard-to-recreate assets: broker relationships, proprietary market data built from real flow, and regulatory permissions. None of these are invincible—talent can be poached—but together they form a meaningful moat.

Process Power: MODERATE. Experience matters in market microstructure. Years of operating in complex, regulated markets builds institutional know-how: risk controls, compliance routines, operational reliability, and the muscle memory of keeping markets running under stress.

Branding: WEAK. This is wholesale plumbing, not consumer goods. The brand helps at the margins, but the real purchase drivers are pricing, liquidity, trust, and execution quality.

XV. Bull vs. Bear Case

🐂 Bull Case:

Electronification is still in the early innings for huge parts of rates, FX, credit, and commodities. Plenty of those markets are still dominated by phone-driven liquidity and fragmented, inefficient screens. If that flow migrates onto platforms like Fenics, BGC doesn’t just grow volume—it can shift the mix toward higher-margin, more scalable revenue.

FMX is the big, asymmetric bet. CME has a near-monopoly in U.S. interest rate futures, and cracking that is extraordinarily hard. But if FMX becomes a real alternative—even in a narrow slice—the value of an exchange franchise can compound far faster than a traditional brokerage. The fact that ten major banks and trading firms took minority stakes matters here: it signals credibility, and it helps with the only thing that ultimately counts in a new market venue—liquidity.

BGC also tends to benefit when markets get noisy. Volatility drives hedging, repositioning, and dealer activity, which pulls brokers and electronic venues into the center of the action. In an environment shaped by geopolitical shocks, shifting central bank paths, and macro uncertainty, that tailwind can persist.

Then there’s governance. Lutnick’s departure to government service and his planned divestiture of his economic interests removes a longstanding overhang. If that lowers perceived related-party risk and controlled-company concerns, it could expand the pool of institutional investors willing to own the stock.

Finally, valuation. BGC has been trying to get paid like a technology-enabled marketplace, not a legacy broker. If investors increasingly underwrite Fenics, data, and network revenue as durable, higher-multiple businesses, the stock has room to rerate—even without heroic assumptions.

🐻 Bear Case:

The long-term threat is disintermediation. As workflows become more electronic and transparent, the need for human brokers can shrink. In the harshest version of the story, voice brokerage isn’t “defensible legacy”—it’s a declining product category.

Even when trading goes electronic, the economics can get ugly. Execution fees often compress as platforms compete, products commoditize, and pricing moves toward “race to zero” dynamics that already played out in equities. If that happens in BGC’s core markets, volume growth may not translate into profit growth.

FMX is also a steep climb. CME has defended its position for decades. And beyond the pure market-structure challenge of attracting enough two-sided flow, FMX’s reliance on LCH raises regulatory and political questions around clearing, particularly given sensitivities about where U.S. rates risk gets cleared. The risk is that FMX never reaches escape velocity.

BGC is also cyclical by nature. When volatility falls and activity dries up, brokerage revenue can drop quickly. That cyclicality doesn’t disappear just because some of the business is more electronic.

And the business is still people-driven. Leadership transitions can create openings for competitors to recruit teams. In an industry where relationships are portable, losing the wrong brokers can mean losing revenue faster than you can replace it.

Key Metrics to Watch:

-

Fully Electronic Revenue Mix (%) - The clearest scoreboard for the transformation. The goal is sustained movement toward 60%+ over time. BGC discloses this as the percentage of total brokerage revenue executed electronically.

-

FMX Trading Volumes and Open Interest - The simplest way to measure whether FMX is becoming a real venue. Track progress against CME’s SOFR and Treasury futures volumes to gauge share.

-

Data, Network and Post-trade Revenue Growth - This is where “fintech multiple” arguments come from. Consistent double-digit growth would strengthen the rerating thesis.

XVI. Lessons for Founders & Investors

BGC’s story isn’t just a Wall Street case study. It’s a set of lessons—some inspiring, some cautionary—for anyone building, buying, or betting on businesses in industries that are getting rewired by technology.

Resilience as competitive advantage. Surviving 9/11 didn’t just keep Cantor alive—it forged the culture that eventually produced BGC. Companies that have been through true existential threats develop an institutional toughness that’s hard to copy. The flip side is that a survivor’s mindset can also tilt toward aggression and risk-taking, and that doesn’t always get rewarded.

Technology + relationships matter in tandem. In wholesale markets, “humans versus machines” is the wrong framing. Pure electronic platforms can win in standardized, high-volume products. Pure voice brokers can still win in complex, illiquid, or fast-moving situations where judgment and discretion matter. BGC’s bet—the hybrid model, where electronic execution is backed by relationship-driven liquidity—may be one of the more durable answers.

Complexity can be both moat and curse. BGC’s famously byzantine structure helped defend control and preserve flexibility. It also confused public investors, fed governance worries, and kept the valuation anchored. The C-corp conversion was a long-awaited acknowledgement of a simple truth: complexity that benefits insiders but punishes outsiders eventually shows up in the multiple.

Founder-led longevity presents tradeoffs. Lutnick’s multi-decade run delivered continuity and a consistent strategic through-line. It also concentrated power, amplified related-party concerns, and likely kept some institutions away. The broader lesson isn’t “founders should leave.” It’s that succession planning can’t start when the transition becomes unavoidable—it has to start while the founder is still firmly in charge.

Data as hidden asset. Every trade that flows through BGC creates information—prices, liquidity signals, and behavioral patterns—that can be packaged and sold at far better economics than execution fees. Market data and analytics businesses often earn higher multiples than brokerage. If you control a real flow of transactions, you may be sitting on a more valuable product than you think.

Transformation timing is everything. BGC started pivoting toward technology years ago, which was the right instinct. The open question is whether it moves fast enough to stay ahead of the secular pressure on voice brokerage. In businesses like this, delay isn’t neutral—it’s margin compression, one quarter at a time.

XVII. Epilogue: What's Next for BGC?

The Lutnick succession is a real inflection point. Howard William Lutnick—who has served as the 41st United States secretary of commerce since February 2025—wasn’t just a long-tenured CEO. He was the force that held together an unusually interconnected ecosystem, and the person who could push through controversial decisions when needed.

Now BGC has to prove it can run without that gravitational center.

The company’s answer is a co-CEO structure: John Abularrage, Jean-Pierre Aubin, and Sean Windeatt sharing the top job. It’s unconventional, but it also fits the reality of BGC: global, multi-asset, and increasingly split between old-school brokerage and newer platform businesses. The open question is whether this is a stable long-term model—or a bridge to a more traditional single-CEO setup once the transition settles.

Strategically, the next few years will likely be defined by one big bet: FMX versus CME. FMX offers SOFR futures and is expected to add U.S. Treasury futures. If FMX can take meaningful share—something like 10% to 15% of CME’s rates franchise—that’s not a “nice win.” That’s transformative. If it doesn’t break out, then FMX risks becoming an expensive ambition that drags on returns.

At the same time, the quieter story may matter just as much: continued electronification of BGC’s core brokerage. FMX UST—its cash U.S. Treasury platform, formerly known as Fenics UST—has been growing its central limit order book share quarter after quarter. It ended the first quarter of 2024 with a 28% market share, up from 26% in the fourth quarter of the prior year. That’s the kind of steady adoption that turns a “tech narrative” into a real structural shift.

And then there’s the wildcard: deals. Further consolidation among interdealer brokers is always on the table. So is the possibility that BGC itself gets bought—by an exchange, a data company, or a diversified financial firm that wants distribution, flow, and a technology stack it can plug into.

Which brings us to the final question. Will BGC still be independent in ten years, or will it be part of something larger? Its technology assets, data businesses, and market infrastructure make it an appealing target. But historically, its scale, profitability, and founder-influenced governance helped keep it standing alone. If governance normalizes as Lutnick exits, strategic alternatives may look more feasible than they ever have before.

XVIII. Closing Reflections

From tragedy to transformation: that’s the through-line. A firm that lost 658 people in a single morning didn’t just survive—it rebuilt, expanded around the world, bought its way into new markets, pushed hard into electronic execution and data, and then did something almost audacious for an interdealer broker: it launched a futures exchange designed to take on CME.

On paper, the interdealer broker business can sound like the definition of unsexy—anonymous middlemen matching trades between banks in markets most people never see. In practice, it’s critical infrastructure. When an institution needs to move a huge position without lighting up the market, it still wants discretion, judgment, and a deep pool of liquidity on the other end. And when Treasury markets become the center of the global financial system—as they do in moments of stress—the pipes matter. BGC has built itself into those pipes.

What BGC really shows about market evolution is that “software eats the world” doesn’t always mean “humans disappear.” In the most standardized products, screens win. But in complex, fast-moving, or fragmented markets, relationships still carry weight—because what clients are buying isn’t just a price, it’s certainty of execution. BGC’s bet has been that the long-run answer isn’t voice or electronic. It’s a hybrid: technology that scales, backed by people who can source liquidity when the market gets tricky.

The most surprising thing, after pulling on all the threads, is how directly 9/11 still connects to the strategy. Decades later, it’s in the culture. It’s in the obsession with resilient infrastructure. It’s in the public-facing identity of the firm and its philanthropic commitments. Plenty of companies have origin stories. BGC has an origin event that still shapes how it operates.

And the question I’d want to put to Howard Lutnick is this: beyond the immediate decisions of September 2001, what was the single hardest strategic call of the last thirty years—the one where you genuinely didn’t know if you were about to break the business—and did it turn out the way you hoped?

XIX. Further Reading & Resources

Essential Links:

- "On Top of the World" by Tom Barbash - A readable history of Cantor Fitzgerald, and a grounded account of the 9/11 aftermath.

- BGC Group 10-K filings (2020-2024) - The best place to see the structure, related-party arrangements, and segment reporting in plain, regulated detail.

- "The Brokerage Trilogy" - TABB Group reports on IDB industry (2015-2020) - Helpful context on how interdealer broking works and how electronification has changed the economics.

- Fenics white papers - Background on BGC’s technology platform and product strategy at fenicsmd.com.

- "102 Minutes" by Jim Dwyer & Kevin Flynn - A minute-by-minute account of 9/11 that includes Cantor’s experience inside the towers.

- BGC investor presentations (2021-2024) - How management has framed the transformation in their own words, available at ir.bgcg.com.

- FT Alphaville series on interdealer brokers - Smart, skeptical industry analysis with real market-structure texture.

- Senate Commerce Committee hearings (2025) - Public record context around Lutnick’s confirmation and testimony.

- BIS Quarterly Review articles on fixed income market structure - Useful framing for how regulation and market plumbing evolved after 2008.

- Federal Reserve research on Treasury market microstructure - A more technical lens on the world FMX UST and rates platforms compete in.

Academic: - Hasbrouck & Saar papers on market microstructure - BIS reports on OTC derivatives market evolution - New York Fed Staff Reports on Treasury market functioning

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music