Balchem Corporation: The Story of a Chemical Compounder Turned Animal Nutrition Powerhouse

I. Introduction: The Puzzle of the Invisible Giant

Picture a dairy farm in Wisconsin at first light. A cow is about to calve. Months earlier, during pregnancy, she’d been fed a supplement engineered to do something that sounds almost impossible: carry a fragile nutrient through the rumen, where it would normally be destroyed, and release it later where it could actually be absorbed.

Now jump scenes.

In a hospital, a clinician reaches for a sterile device. The packaging was treated with a specialty gas. Different industry, same idea: chemistry you never see, doing work you absolutely rely on.

And across town, a new parent mixes infant formula that includes an essential nutrient associated with brain development—sourced, again, from the same quiet company headquartered in New Hampton, New York.

That company is Balchem.

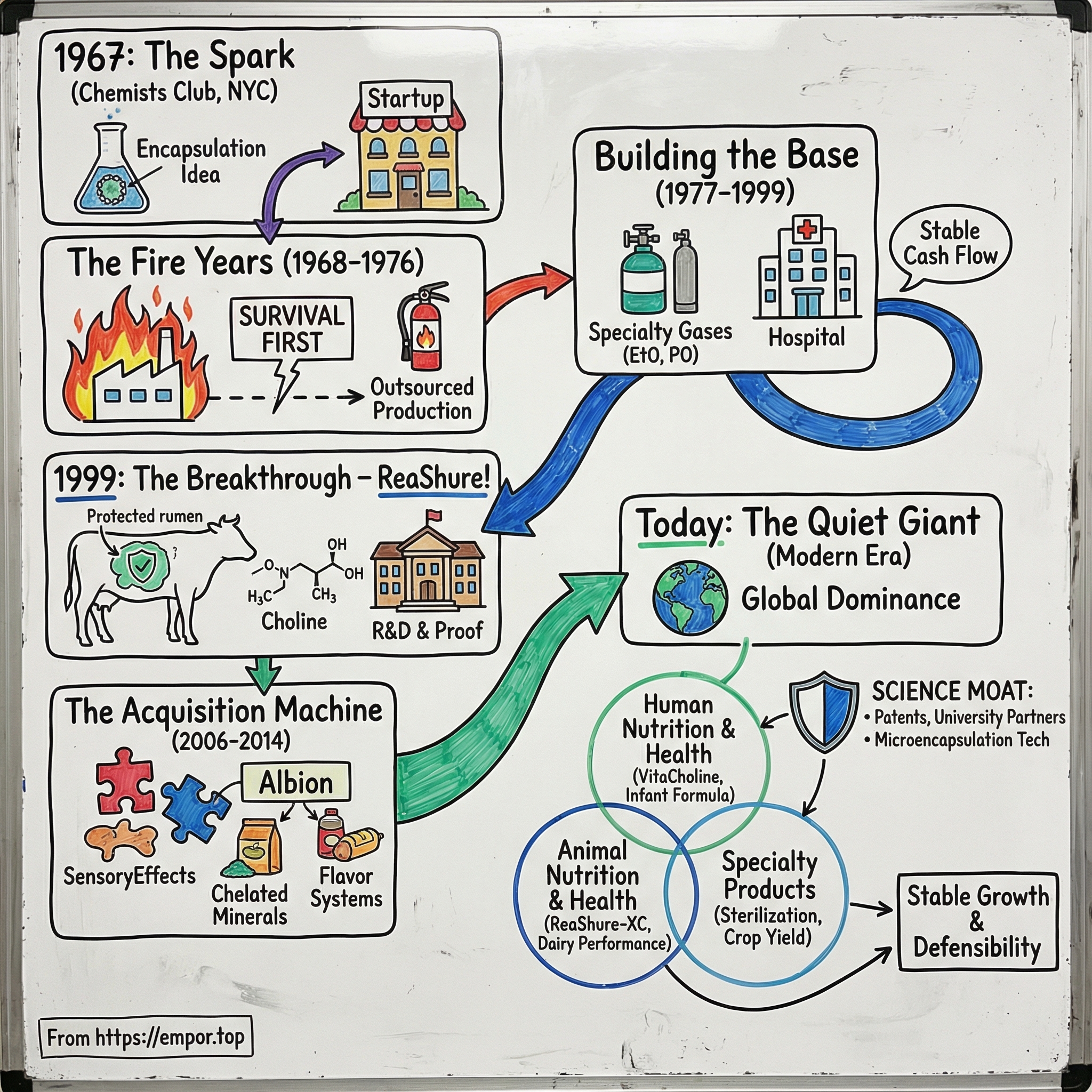

Balchem was founded in 1967, and it built its business around trusted, science-based solutions for nutrition, health, and food markets. Yet despite touching dairy farms, hospitals, nurseries, and supplement aisles, “Balchem” isn’t a household name. That’s the paradox at the center of this story: Balchem makes mission-critical ingredients, but it stays largely invisible to the end consumer.

The scale, though, is anything but small. For the twelve months ending September 30, 2025, Balchem generated $1.014 billion in revenue, up 7.55% year over year. In Q3 2025, GAAP net earnings rose 19.1% to $40.3 million. And with a major expansion underway to more than double its microencapsulation capacity, the company is leaning into the very technology that started it all.

So here’s the question that makes Balchem so interesting:

How did a fire-prone encapsulation startup—born in a laboratory atop the Chemists Club in midtown Manhattan—survive near-death moments, reinvent itself across industries, and end up as the world’s dominant force in rumen-protected choline, while also becoming a major player in both human and animal nutrition?

Balchem went public in 1970 and trades on NASDAQ as “BCPC.” Today, it operates through three segments—Human Nutrition & Health, Animal Nutrition & Health, and Specialty Products—each with its own customers, economics, and competitive dynamics. Getting from there to here required literal fires, hard pivots, breakthrough science, and an acquisition strategy that steadily expanded what Balchem could offer.

And for investors, the appeal is straightforward: strong secular tailwinds, defensible technology like microencapsulation and chelated minerals, and a business model that turns scientific proof into pricing power. Balchem’s moat isn’t just patents or scale. It’s decades of university partnerships, feeding trials, and relationships with nutritionists who don’t gamble with herds—or reputations—on unproven substitutes.

II. Founding Context: Encapsulation Science in the 1960s

Balchem’s origin story doesn’t start with a grand plan to transform animal nutrition. It starts with a classified ad.

In 1967, chemist Dr. Herbert Weiss spotted a Wall Street Journal advertisement touting an invention that could coat individual particles—essentially letting you deliver nutrients in measured doses. Forbes reports that Weiss didn’t just file it away as an interesting idea. He went looking for the inventor.

That inventor was Dr. Leslie L. Balassa. Balassa had earned his doctorate in chemistry at the University of Vienna in 1926 and later worked for E.I. du Pont de Nemours & Company. He wasn’t a “feed” scientist; he was a drug-delivery scientist. He’s best remembered for contributions in pain relief, including treatments designed to ease pain from molar extractions and long-term arthritis discomfort. Underneath those applications was the real breakthrough: a patented microencapsulation process that became a foundation for time-release medicine.

That detail matters, because it explains Balchem’s DNA. This was a company born from the idea that coatings—applied with precision—could change what an active ingredient actually does in the body. From time-release pharmaceuticals to time-release nutrients is not a huge conceptual leap. The market opportunity just took a long time to catch up.

Weiss and Balassa teamed up with three former officers of Baltimore’s Alcolac, Inc., along with other Baltimore investors, to form Balchem. The company acquired the rights to Balassa’s inventions, processes, and technologies. It incorporated in Maryland in 1967, with Balassa initially serving as president. But the business didn’t spring to life overnight. Balchem went through a long development stretch, and actual operations didn’t begin until 1970.

Early on, the company worked out of laboratory space on the top floor of the Chemists Club in midtown Manhattan—an almost cinematic setting for a business that would later become essential to industries far from Manhattan. From there, Balchem moved to Slate Hill, New York, setting up operations on the site of a former dairy. It’s hard not to notice the irony: a company that would eventually become a major force in dairy nutrition got its manufacturing start on an old dairy farm.

To understand why any of this mattered, you have to understand the basic problem microencapsulation solves. Many useful ingredients are fragile, volatile, reactive, or simply unusable in their raw form. A flavor component can degrade in storage. A nutrient can get destroyed before it reaches the part of the digestive system where it’s absorbed. A medicine can hit too hard if it releases all at once instead of over time.

Microencapsulation tackles that by wrapping an active ingredient in a protective shell—often using fats, polymers, or other coating materials—so it’s shielded from the outside world until the right conditions trigger release. It’s a way to improve stability, control timing, and make the core ingredient more effective.

But even with a powerful technology, Balchem still had a very 1960s problem: it needed cash. The encapsulation business wasn’t ready to carry the company on its own, so Balchem made a pragmatic choice. It would manufacture and sell what it called “known products for known markets.” In other words: while it built the future, it would fund the present with conventional chemical production.

The equipment and expertise were adaptable, and synthetic organic chemicals could be produced without shutting the door on future encapsulation work. In October 1970, Balchem formed a subsidiary—Arc Chemical Corporation—to run this side of the business. For the first several years, Arc generated most of Balchem’s revenue.

It was a classic early-stage play: keep the lights on with lower-margin, more established products while nurturing the higher-margin, proprietary technology that was supposed to become the real business.

By 1971, Arc was in production, and Balchem was also doing commercial encapsulation work for the food industry. It encapsulated solids like flavor enhancers fumaric acid and adipic acid, preservative sodium nitrate, leavening agent sodium bicarbonate, and nutrient ferrous sulfate. Then came a major early win: Balchem landed a contract with General Foods, which wanted to simplify a lemon pudding mix. Using encapsulation, Balchem helped reduce what had been a three-step process to a single step by combining lemon oil, powdered starch, and citric acid.

That General Foods contract was proof that the science could pay the bills. Encapsulation wasn’t just clever chemistry—it could make a product better, simpler, and more scalable. Still, Balchem was very much in its infancy. Encapsulation revenue was modest, and the company was leaning heavily on the chemical subsidiary it had created to survive.

III. The Fire Years: Near-Death Experiences (1968-1976)

Making specialty chemicals in the early 1970s wasn’t just competitive—it was dangerous. Volatile compounds, reactive intermediates, heat, pressure… it was the kind of manufacturing where a small mistake could become a catastrophe. For Balchem, running out of Slate Hill with limited capital and basically no margin for error, that risk wasn’t theoretical. It was existential.

The first big warning came in 1972. After an incident at the facility, Balchem reached a $300,000 settlement with its insurer on April 20. The money wasn’t just for patching holes. Balchem used the rebuild as an opportunity to modernize, adding anti-pollution devices that were quickly becoming mandatory across the chemical industry. Arc Chemical returned to production and even broadened its lineup—adding monomers for plastics and specialty ethoxylates used in textiles, plastics, and cosmetics.

It looked like a recovery. In 1972, revenue was about $850,000 and the operating loss shrank to $36,500. That same year, Balassa retired and Weiss took over. In 1973, the business kept moving in the right direction, bringing in almost $1.2 million in revenue and making “profitability” feel close enough to touch.

Then, on January 21, 1974, it happened again.

Another fire—again tied to specialty chemical manufacturing—wiped out momentum in a single day. Balchem sold what equipment it could salvage, but the damage still produced a loss of more than $222,000. For the year, Balchem lost $524,000, and revenue slid to $706,000.

At that point, management stopped trying to muscle through it. They made a hard, survival-first decision: cease direct production of specialty chemicals. Instead, Balchem would have an outside company manufacture the products, while Balchem marketed them on a commission basis.

This wasn’t a tweak. It was an admission that the “keep the lights on” business was now the thing most likely to burn the house down.

Outsourcing bought Balchem breathing room. It reduced operational risk, protected the balance sheet, and gave the company a chance to keep developing what it actually believed in: encapsulation. And it worked. In 1975, Balchem finally posted a profit—$236,000 on $967,285 in revenue. Better still, encapsulation was gaining traction in the market. Customers were starting to understand what controlled release and ingredient protection could do, and Balchem’s growth accelerated. Revenue climbed through the rest of the decade, reaching $5.15 million by 1980, with profits in each year along the way.

By 1976, Balchem employed just 12 people. By decade’s end, it was up to 50. The company wasn’t just surviving anymore—it was building.

And then came another pivotal choice. In late 1976, Balchem returned to direct specialty chemical sales after a three-year hiatus—but with the scars to prove it wasn’t going to repeat the same mistake. Instead of producing volatile chemicals at the Slate Hill site alongside encapsulation, Balchem set up chemical production separately, establishing a facility in South Carolina. The separation was the point: keep the core encapsulation operation insulated from the hazardous, cash-generating work.

In January 1977, Arc Chemical merged into Balchem as the Arc Chemical Division, and the Arc subsidiary itself was dissolved. The South Carolina plant was completed and operational by May 1979.

In hindsight, it’s easy to tell Balchem’s story as a clean arc of invention to dominance. The fire years are the reminder that it wasn’t. Plenty of specialty chemical startups in that era didn’t make it through setbacks like these—accidents, financing strain, bad timing, and strategic overreach. Balchem did, thanks to insurance that kept it afloat, management willing to make radical changes, and the discipline to redesign the business around a simple truth: survival comes first, and the future only matters if you’re still around to build it.

IV. Building the Foundation: Specialty Gases & Early Diversification (1977-1999)

If the fire years were Balchem fighting to stay alive, the late 1970s and 1980s were the company learning how to stand on its own two feet. Arc Chemical’s merger into Balchem in 1977 wasn’t just paperwork. It was a signal that Balchem was growing up—integrating the revenue-generating chemical side with the longer-term bet on encapsulation, and starting to look like a real operating company.

One of the most important foundations it built in this era was Specialty Products—particularly specialty gases. Over time, Balchem’s portfolio here centered on three: ethylene oxide, propylene oxide, and methyl chloride.

Ethylene oxide was the crown jewel. In healthcare, it’s used as a sterilizing agent by hospitals, medical device manufacturers, and contract sterilizers. And it’s not a niche application. Ethylene oxide can sterilize both hard and soft surfaces, which makes it useful across an enormous range of products—from syringes, catheters, and scalpels to gauze, bandages, and full surgical kits.

Propylene oxide went into different channels. Balchem sold it into chemical synthesis markets and for bacteria reduction in spice treatment. It also showed up in industrial processes like coating textiles, treating specialty starches, and improving paint strength.

The third gas, methyl chloride, served as a raw material input—used in products like herbicides, fertilizers, and pharmaceuticals.

What made this business such a good fit for Balchem wasn’t just that it generated revenue. It matched the company’s personality. Specialty gases are hazardous, highly regulated, and unforgiving to low-quality operators. That creates real barriers to entry. Customers care about reliability and compliance, not just price. And once you’re qualified and embedded in a regulated supply chain, switching isn’t simple.

Ethylene oxide illustrates that dynamic perfectly. It was first registered as a pesticide in the U.S. in 1966, which meant it later went through the EPA’s reregistration process. A RED was completed in 2008. As of now, there is one technical registrant: ARC Specialty Products of Balchem Corporation.

Balchem’s acquisition of Allied Signal’s sterilant gas business—flagged in company timelines as a key milestone—was a turning point for this segment. It helped establish Balchem as a premier supplier of ethylene oxide to the healthcare industry, a position the company would reinforce in the decades that followed.

The demand drivers were as steady as they come. Ethylene oxide is among the leading sterilization methods in healthcare because it’s effective and works at low temperatures. That low-temperature capability is crucial: many modern medical devices rely on plastics, composites, and other materials that can’t tolerate high heat. Ethylene oxide is compatible with a wide range of materials, including metals, plastics, and elastomers, and it’s used not only for devices but also for medicinal products, packaging, and combination products.

For investors, the logic is straightforward. Sterilization is non-discretionary. Medical device makers and hospitals don’t get to pause it during downturns. Regulation raises the moat. And many critical products—especially complex medical device kits assembled to streamline surgical procedures—depend on ethylene oxide because of the mix of device types and materials inside a single package.

By the end of the 1980s, Balchem had climbed to nearly $10 million in annual revenue—an astonishing distance from the post-fire low point just a decade earlier. It had a sturdier base now: specialty gases for durable, regulated cash flow, and encapsulation continuing to mature in the background.

But the next transformation—the one that would shape Balchem for the next quarter century—was only beginning to come into focus.

Animal feed additives, especially choline chloride for poultry and swine, looked like a natural adjacency. Choline is an essential nutrient for growth and health. For monogastric animals—pigs and chickens—standard choline chloride products worked well enough. But for ruminants—cattle, sheep, goats—the story was different.

In ruminants, the digestive system doesn’t just absorb nutrients. It can destroy them first. And that would become Balchem’s opening.

V. The Game-Changer: ReaShure & Rumen-Protected Choline (1999-2010s)

The rumen is both the dairy cow’s superpower and the nutritionist’s headache.

It’s the first compartment of a ruminant’s stomach, packed with microbes that can turn rough forage—grass, hay, silage—into usable energy. Evolutionary magic. But that same microbial ecosystem doesn’t politely step aside when you try to deliver targeted nutrients. It breaks down fiber, and it breaks down a lot of supplements, too—long before they ever reach the small intestine, where absorption actually happens.

Choline is a perfect example. It’s an essential nutrient tied to liver function, fat metabolism, and milk production, but in a standard form it simply doesn’t survive the rumen. By the time unprotected choline gets to the abomasum and small intestine, the bacteria have already taken it.

This is where Balchem’s entire origin story suddenly matters.

After decades spent perfecting microencapsulation—and years applying it specifically to dairy—Balchem launched its first animal nutrition product in late 1999: ReaShure® Precision Release Choline. The promise was elegantly simple. Encapsulate choline so it could pass through the rumen intact, then release where the cow can actually use it.

ReaShure wasn’t just a new product; it was the first time Balchem aimed its core technology at a high-value, high-stakes biological bottleneck. And it worked well enough that universities and farms started putting it to the test. Studies showed that feeding rumen-protected choline promoted animal health, improved reproductive function, and increased milk yield—outcomes that, in dairy, quickly translate to profitability. The newest research also points to epigenetic benefits for the in utero calf.

Over time, ReaShure built something even harder to manufacture than an encapsulated nutrient: credibility. Balchem could point to a long record of peer-reviewed research, on-farm studies, and composite summaries. In a market where producers don’t like surprises—and nutritionists don’t like betting their reputations—being the most extensively researched and tested encapsulated choline on the market is a real advantage.

And the use case fit the rhythm of dairy economics. The pitch wasn’t “feed this forever.” It was: feed ReaShure to transition cows for about 42 days—roughly three weeks before calving through three weeks after—and let the benefits show up across the entire lactation.

University research backed up specific outcomes. Work from the University of California-Davis and the University of Florida showed measurable reductions in metabolic disorders like ketosis, displaced abomasum, and subclinical milk fever when cows were fed ReaShure. University of Florida data also showed a lactation-long impact on milk production: cows fed ReaShure during transition hit higher peaks and produced an additional 2.1 kg of milk per day.

That’s the kind of result dairy farmers understand instantly. An extra 2.1 kilograms per day, sustained across a standard 305-day lactation, adds up to roughly 640 kilograms more milk per cow. The intervention happens during a short window, but the payoff can run for the whole year.

Balchem’s materials also framed the broader economic story in practical, farm-level terms—more milk, fewer involuntary culls, better calf performance, more colostrum—and even cited a 25-to-1 return on investment. The exact numbers will vary by herd and milk price, but the core point held: compared to most inputs on a dairy, this was a small change with the potential for outsized impact, supported by published science rather than anecdotes alone.

Research also linked choline to reduced ketosis, improved lactation performance, and enhanced fertility. Put that together and you can see why ReaShure changed Balchem’s trajectory. It pulled the company out of the gravity of “specialty chemicals” and into something far more defensible: a mission-critical partner to dairy nutritionists. The relationship became less about selling an ingredient and more about improving herd outcomes—creating higher margins, higher switching costs, and the foundation for the dominance Balchem would build in choline over the decades to come.

VI. The Acquisition Machine: Building Human Nutrition & Health (2006-2014)

ReaShure gave Balchem a breakout product and a scientific calling card. But management could see the bigger opportunity: if you could protect and precisely deliver nutrients for a cow, you could do it for people, too. The mid-2000s became the start of a deliberate acquisition strategy that would reshape Balchem from a specialty chemicals company into a broader nutrition and ingredients platform.

The first move was about control.

In 2006, Balchem acquired an animal feed grade aqueous choline chloride manufacturing facility in St. Gabriel, Louisiana, from BioAdditives and CMB Additives. The logic was vertical integration into choline—owning more of the supply chain behind both the commodity choline business and the premium, technology-enabled products Balchem was building. The facility had about 80 million pounds of capacity, giving Balchem scale and security of supply in a market where reliability matters.

But the deal that truly changed the company’s trajectory came in 2014: SensoryEffects.

On May 7, 2014, Balchem announced it had completed the acquisition of Performance Chemicals & Ingredients Company, doing business as SensoryEffects, a supplier of customized food and beverage ingredient systems based in St. Louis, Missouri. The transaction had been announced earlier on March 31, 2014. Balchem acquired all outstanding capital stock for $567,000,000, before working capital and other adjustments.

The price tag was big. SensoryEffects expected about $260 million in 2014 revenue and about $53 million in EBITDA—putting the deal at roughly 10.7x EBITDA. That’s premium territory. Balchem paid it because SensoryEffects wasn’t a commodity ingredient business. It was an applications-and-systems business: technology-driven solutions designed to make foods and beverages taste better, feel better, mix better, and look better—improving properties like texture, solubility, aroma, and color for brand-name customers.

SensoryEffects was a leader in powder, solid, and liquid flavor systems, creamer and specialty emulsified powders, cereal-based products, and other functional ingredient delivery systems. It had also built a broad customer base by pairing innovation with operational efficiency, backed by serious food safety and quality capabilities.

Part of what made SensoryEffects so attractive was that it already looked like a platform—because it had been built that way. Over the eight years leading up to 2014, SensoryEffects had completed twelve additional acquisitions, invested heavily in people and capital projects, and grown to six manufacturing sites. Those deals ranged from family-owned businesses to corporate carve-outs, negotiated transactions, an auction process, and even a bankruptcy process. Yet, as the company described it, each acquisition fit the same strategy developed by its founder, Charles A. Nicolais—and it wasn’t just roll-up math. SensoryEffects leveraged the platform to drive substantial organic growth as well.

Nicolais put it simply at the time: “We are excited to enter into this agreement with Balchem, who is an ideal partner for us, strengthening our position by merging our business with its encapsulated and functional choline ingredients.” Founded in St. Louis and backed by Highlander Partners, L.P. of Dallas, SensoryEffects had become a significant food and beverage ingredient supplier—and Balchem saw a way to combine that customer reach with its own strength in functional ingredients and delivery technology.

The acquisition brought Balchem three business units—powder systems, flavor systems, and cereal systems—broadening what Balchem could offer the human nutrition and food ingredients market. In plain terms: Balchem wasn’t just selling ingredients anymore. It was moving closer to selling finished solutions that customers could plug directly into products on shelves.

Balchem framed the combined opportunity around complementary strengths: two companies with reputations for quality and technical problem-solving, now able to serve a wider range of food and beverage customers with a deeper toolkit.

In February 2016, Balchem continued this acquisition strategy with the purchase of Albion International.

On February 1, 2016, Balchem announced it had acquired Albion International, Inc., a privately held manufacturer of mineral amino acid chelates, specialized mineral salts, and mineral complexes headquartered in Clearfield, Utah, for $111.5 million in cash. Albion’s 2015 revenue was approximately $53.5 million. The purchase price reflected a multiple of approximately 10.7 times 2015 EBITDA, excluding synergies, and it was financed through Balchem’s revolving credit facility and cash on hand.

Albion had deep roots—going back to 1956—and a long-standing reputation as a leader in organic mineral compounds. For Balchem, already the global leader in choline, the appeal was straightforward: add another science-forward product family to the portfolio and broaden the company’s footprint in nutritional ingredients. The combination also strengthened Balchem’s position as a technology leader in spray-drying and ingredient delivery solutions.

Albion’s brand story leaned hard into scientific support: decades of mineral research, a long list of publications, and products like Ferrochel® positioned as leaders within their categories. It fit Balchem’s playbook perfectly. This wasn’t about buying revenue. It was about buying credibility, capability, and a product line that could win on performance—not price.

VII. The Modern Era: XC Technology & Global Choline Dominance (2015-Present)

When Ted Harris took over as CEO in April 2015, Balchem was already a leader in a handful of narrow, high-value niches. What it needed next wasn’t a new identity—it needed scale, discipline, and a sharper growth engine. Harris brought that playbook with him, shaped by senior roles at Ashland Performance Materials and at FMC, where he ran the Food Ingredients Division.

Harris became CEO in April 2015, and later added the Chairman role in January 2017. He also serves on the board of Pentair plc. Under his leadership, Balchem kept doing what it had always done best—investing in R&D and upgrading its core technologies—but with a renewed focus on turning scientific advantage into the next generation of products.

The most important recent upgrade landed in 2021: ReaShure-XC, a next-generation version of Balchem’s flagship rumen-protected choline.

At a high level, ReaShure-XC is still the same promise that made ReaShure matter in the first place: get choline through the rumen intact, and release it later where the cow can actually absorb it. The difference is in the engineering. ReaShure-XC pairs a new pure choline crystal core—designed to deliver a higher, more concentrated payload and eliminate the need for a carrier—with Balchem’s X-Technology coating system. That coating is built to balance three competing requirements at once: stability in feed, stability in the rumen, and reliable release in the intestine.

Balchem positioned the product as not just more effective, but also more efficient. With a more concentrated formulation, customers can deliver the same nutrient with less material—something the company noted reduces emissions per unit of choline delivered, lowering the carbon footprint of supplementation.

ReaShure-XC is also the culmination of the thing competitors struggle most to replicate: proof. Backed by more than 25 years of research, Balchem describes it as the most extensively tested encapsulated choline on the market. And as the research has continued, the story has expanded beyond the transition cow.

The newest findings pointed to something bigger than milk yield: transgenerational effects. Balchem cited research indicating that calves born from cows supplemented with ReaShure-XC showed a 0.05 kg/day improvement in average daily gain—adding up to heifers that were 36 kg larger at calving and that produced 1.8 kg more milk per day during first lactation. Separate research highlighted colostrum outcomes, noting that cows consuming ReaShure-XC during the 21 days prior to calving had a 57–85% increase in colostrum quantity—about 2.3 kg more.

Academic work explored the same theme from another angle: feeding rumen-protected choline to late-gestation dairy cows potentially affecting offspring growth and metabolism. In a study evaluating in utero choline exposure in Angus × Holstein cattle, feeding prepartum dairy cows rumen-protected choline increased offspring body weight and height through 10 months of age. The intervention also improved indicators of insulin sensitivity when calves were later fed a finishing diet—results that could have implications for carcass composition.

While ReaShure-XC strengthened Balchem’s position in animal nutrition, the company was also extending its reach in the other “quiet powerhouse” segment that had become a foundation over decades: specialty gases.

In 2019, Balchem signed a definitive agreement to acquire Chemogas NV, a privately held specialty gases company based in Grimbergen, Belgium, from Gilde Equity Management and Chemogas management. Chemogas was a leader in packaging and distributing specialty gases—most notably ethylene oxide—serving medical device sterilization customers primarily across Europe and Asia. The company supported customers in more than 70 countries. Balchem said Chemogas expected approximately €29 million in 2019 revenue with an EBITDA margin of around 30%, and that the transaction would be financed with the company’s revolving credit facility and cash on hand. Balchem also stated the deal was expected to be accretive to adjusted EPS in 2019.

Strategically, it did something simple and powerful: it expanded Balchem’s packaged ethylene oxide footprint from a strong U.S. position into a global network. Combined with Balchem’s U.S. sites, the Chemogas facilities in Europe and Asia gave the company worldwide service capability for sterilization customers. Harris summed up the ambition clearly at the time, saying that with the acquisition, Balchem was now the clear global leader in the critical supply of ethylene oxide to the medical device sterilization industry.

The numbers during Harris’s tenure reflected the broader pattern: steady growth, with profitability expanding faster than revenue. In 2024, Balchem revenue was $953.68 million, up from $922.44 million the year before, and earnings increased to $128.48 million.

And the momentum carried into 2025. Balchem reported record Q1 2025 consolidated revenue of $251 million, up 4.5% year over year, alongside record adjusted EBITDA of $66 million and adjusted net earnings of $40 million. Management emphasized resilience amid a shifting global trade environment, noting manageable direct tariff impacts on raw material imports and minimal impact on exports at the time. Performance was broad-based: Human Nutrition & Health delivered record sales of $158 million, Animal Nutrition & Health posted $57 million in sales and continued its recovery, and Specialty Products came in at $33 million.

All of it reinforces the modern Balchem formula: keep upgrading the science, keep widening the platform, and make the company harder to replace in the places where customers can’t afford failure.

VIII. Business Model Deep Dive: The Three-Legged Stool

By now, Balchem isn’t one business. It’s three. And that’s not an accident—it’s the result of decades of pivots, reinventions, and acquisitions that gradually turned a fragile encapsulation startup into a portfolio of “must-not-fail” ingredients.

Today Balchem develops, manufactures, and markets specialty performance ingredients for nutrition, food, pharmaceuticals, animal health, medical device sterilization, plant nutrition, and a range of industrial applications. Those offerings roll up into three segments: Human Nutrition & Health, Animal Nutrition & Health, and Specialty Products. Each one behaves differently, but together they create a three-legged stool: growth, defensibility, and steady cash flow.

Human Nutrition & Health (about 60% of revenue, based on recent segment data) is now the biggest segment and a major engine of growth. This is where the SensoryEffects platform lives—powder and flavor systems, spray dried and emulsified powders, extrusion and agglomeration, blended lipid systems, liquid flavor delivery systems, juice and dairy bases, chocolate systems, cereal systems, and even ice cream bases and variegates. Layered on top of that are Balchem’s “science brands”: specialty vitamin K2, microencapsulation solutions, human-grade choline nutrients, and mineral amino acid chelated products.

VitaCholine is a clean example of how Balchem plays this game.

Choline is an essential nutrient for human health, officially recognized by the Institute of Medicine in 1998. And yet, study after study suggests that more than 90% of people aren’t getting enough choline from diet alone. Balchem’s VitaCholine® line of choline salts shows up in infant formula, prenatal multivitamins, fortified foods, and supplements—not because it’s flashy, but because it’s trusted.

That trust was reinforced by clinical research in which VitaCholine was the choline source used. In one study design, the intervention group received a total of 930 mg of choline per day from diet plus supplementation, while the control group received 480 mg. Researchers controlled other key nutrients during pregnancy, like folate, to isolate the effect. After birth, infants were tested on saccade eye reaction times—how quickly the brain processes an image before the eyes move to new stimuli. Published in The FASEB Journal, the results showed babies born to mothers in the higher choline group had significantly faster information processing speeds than those in the control group.

Cornell University researchers later published additional work in The FASEB Journal reinforcing the same core idea: choline plays a critical role in infant cognitive development, and higher intake during pregnancy was associated with cognitive benefits that persisted into early childhood. VitaCholine® from Balchem was the choline used in the original Cornell study.

Underneath all of this is the secular tailwind: most people don’t hit recommended choline intake, and many don’t even realize choline needs to be consumed daily. NHANES 2015–2018 data put mean dietary intake at 284 mg/day for women and 390 mg/day for men, with only 6% of women and 11% of men above the adequate intake. For pregnant women, less than 9% met the adequate intake.

Animal Nutrition & Health (about 25% of revenue) is anchored by the ReaShure franchise, plus related products for both ruminants and monogastrics. The go-to-market model here is relationship-driven and science-driven: Balchem sells through nutritionists, feed mills, and integrated producers. These customers are sophisticated, skeptical, and intensely ROI-focused—which is exactly why Balchem’s long track record of research matters. In practice, this segment behaves less like “selling feed additives” and more like selling performance insurance to operations that can’t afford a bad nutritional bet.

Specialty Products (about 15% of revenue) is the steadying leg. It includes ethylene oxide for medical device sterilization and propylene oxide for food safety applications like spice and nutmeat fumigation and pasteurization. This segment also includes Plant Nutrition, where Balchem sells Metalosate® chelated minerals—using amino acid chelate technology designed to help growers deliver micronutrients efficiently through foliar sprays to improve crop yield and quality. In other words: regulated, mission-critical chemistry that tends to hold up when other parts of the economy wobble.

IX. The Science & Technology Moat

The most important thing to understand about Balchem’s competitive position is that it’s built on science—then reinforced by manufacturing know-how—not just scale or distribution.

At the center is proprietary technology. Balchem’s core expertise in microencapsulation and chelation creates real barriers to entry. Those capabilities let it make differentiated products that can earn premium pricing, including the Albion Minerals line.

Company leadership has been blunt about where the edge starts: “That’s really the foundation of Balchem – that microencapsulation technology.” You can see it across the brand portfolio. Albion® Minerals is positioned around improving mineral utility and bioavailability. VitaCholine® is built on high-quality choline ingredients for human health applications. And VitaShure®—Balchem’s line of microencapsulated ingredients—aims to do what microencapsulation was always meant to do: protect potency, extend shelf life, and improve taste and stability in finished products.

Chelation is the other pillar. Through Albion®, Balchem has long positioned itself as the pioneer in chelated mineral research and technology across human, animal, and plant health. The claim is straightforward: these are “gold standard” mineral chelates, produced in state-of-the-art facilities, and backed by a deep library of patents—over 150 of them—covering everything from manufacturing processes to food applications. The practical promise is also straightforward: minerals bound into forms that are designed to be absorbed and used effectively, making them valuable for supplements and food fortification.

Albion’s leadership leans into the origin story, too. As Stephen Ashmead, Sr Fellow for Chelates R&D at Balchem Corp—and grandson of Albion founder Harvey H. Ashmead—put it: “Albion® pioneered amino acid chelates — long before they became the industry standard. My grandfather Harvey Ashmead transformed nature’s concept into validated science. With proven absorption and real bioavailability. We are the original. And still the leader.”

But the moat isn’t just what Balchem makes. It’s how Balchem proves it works.

University partnerships add another layer of advantage. Balchem partners with universities to run studies on emerging technologies and products, building the kind of third-party validation that matters in nutrition. As Reid explained, “We’re really big on research to try to make sure that we’re staying current and can come up with the next best thing to offer to our customers. We have done so many studies and so much work internally to understand our products, and we want to make sure people are aware of the nutritional value of our products.”

That research engine is also how Balchem keeps widening the story beyond a single product claim. The company has said its purpose is to remain a pioneer in choline research and encapsulation technology, digging deeper into the mechanisms behind the consistent results shown in scientific trials and on-farm outcomes. More recently, that has meant focusing on areas like metabolomics and epigenetics—work that includes University of Florida studies led by Dr. José Santos examining the nutrigenomic role of choline in heifer growth and health performance.

X. Competitive Landscape & Market Dynamics

Balchem competes in a set of markets that look similar from 30,000 feet—ingredients, nutrition, regulated chemicals—but play by very different rules once you’re on the ground.

In Animal Nutrition, the company goes up against giants like DSM-Firmenich, Evonik, Adisseo, and Kemin. These are broad, diversified animal health and nutrition platforms with global reach. But rumen-protected choline is a narrower arena, and here Balchem’s advantage isn’t size—it’s time. With more than 25 years of work behind ReaShure, plus a deep bench of published research and field experience, Balchem built a reputation with dairy nutritionists that’s hard to dislodge.

In Human Nutrition, the competitive set shifts to large ingredient houses like Kerry Group, Givaudan, IFF, and Glanbia. Again, many of these players are bigger. Balchem’s edge is that it tends to win on trust and technical problem-solving—scientific credibility, application expertise, and consistent quality—rather than trying to out-muscle competitors on scale alone.

What makes the overall model resilient is diversification. Balchem operates across three distinct end markets—Human Nutrition, Animal Health, and Specialty Industrial—which means a slowdown in any one doesn’t automatically sink the whole ship. That “three-legged stool” structure acts as a buffer when the cycle turns.

And the wind is generally at Balchem’s back. The biggest tailwinds are straightforward:

- Global dairy intensification: the push to get more milk per cow increases demand for precision nutrition tools like ReaShure.

- Human nutrition premiumization: rising awareness of choline deficiency, the supplement boom, and growing interest in cognitive health.

- Medical device sterilization growth: aging populations, more procedures, and ongoing innovation in complex devices that still need reliable sterilization.

- Sustainability pressure: precision nutrition can reduce waste and the environmental footprint versus blunt, over-supplementation.

But the business isn’t immune to gravity. The main headwinds are the usual suspects in ingredients: volatility in commodity inputs, customer consolidation (mega-dairies and large feed mills gaining bargaining power), and the constant threat of low-cost competition—especially from Chinese manufacturers in bulk choline.

XI. Strategic Analysis: Porter's Forces & Hamilton's Powers

You can tell Balchem’s story through products and acquisitions. But you can also tell it through structure: what makes this business hard to attack, hard to copy, and hard to displace once it’s embedded. Two frameworks help make that visible.

Porter's Five Forces Assessment:

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

Breaking into Balchem’s core niches isn’t like launching another ingredient brand. New entrants run into a wall of practical barriers: years of feeding trial data needed to earn credibility, regulatory approvals like FDA and EFSA that take time, major capital requirements to build encapsulation capability, and customer relationships that are won through technical service—not a price sheet.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MEDIUM

Balchem relies on specialized inputs, including trimethylamine for choline production, which gives suppliers some leverage. But Balchem has partially insulated itself through vertical integration in choline and by using long-term contracts that add stability.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MEDIUM-HIGH

Balchem sells into markets where buyers can be big—large dairy cooperatives and feed mills—and that size gives them negotiating power. Still, switching isn’t frictionless. Reformulating a ration or changing a validated input takes time, carries performance risk, and can create real operational headaches. When performance matters, differentiation blunts pure price pressure.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW-MEDIUM

In rumen-protected choline, the substitute set is thin—there just aren’t many alternatives with comparable proof and efficacy. In human nutrition, there are more options, but brand trust and quality still separate suppliers. And in sterilization gases, ethylene oxide remains difficult to replace for many applications, which limits substitution.

Competitive Rivalry: MEDIUM

Competition is real, but this isn’t a commodity knife fight. Specialty ingredients tend to compete on reliability, science, service, and compliance. And because end markets are growing, it’s less of a pure zero-sum brawl.

Hamilton's Seven Powers Assessment:

Scale Economies: MODERATE — Scale helps in choline production, but the market isn’t winner-take-all; niche applications can support multiple players.

Network Economies: WEAK — There are no meaningful network effects here; this isn’t a platform business.

Counter-Positioning: MODERATE — Balchem’s early move into rumen-protected choline created a position that low-cost, commodity choline producers couldn’t easily chase without undermining their own business models.

Switching Costs: STRONG — Nutritionists don’t like changing what works. Reformulation and revalidation take time, and in animal health, the downside of a bad switch is measured in production and profit.

Branding: STRONG — ReaShure® is widely recognized in dairy nutrition. VitaCholine® is trusted in infant formula. Albion® Minerals carries “gold standard” credibility in chelated minerals. Here, brand is really shorthand for scientific confidence and consistent quality.

Cornered Resource: MODERATE-STRONG — Balchem has what most competitors can’t buy quickly: decades of peer-reviewed research, university partnerships, feeding trial infrastructure, regulatory approvals and GRAS determinations, and proprietary encapsulation formulations.

Process Power: STRONG — This is the quiet superpower: decades of manufacturing know-how in microencapsulation, quality control systems that are hard to replicate, and embedded customer relationships that feed back market intelligence.

Primary Power: Put together, Process Power plus Branding plus Switching Costs form Balchem’s moat—especially in Animal Nutrition, where customers are allergic to uncertainty and loyal to proven results.

XII. Bull vs. Bear Case

The Bull Case:

Start with the simplest tailwind: the world keeps eating more animal protein. As incomes rise—especially across parts of Asia—demand for dairy and meat tends to rise with them. That’s the tide Balchem’s Animal Nutrition business swims in. And it’s not just “more feed.” Precision nutrition has become part of the sustainability story, too: deliver the right nutrients more effectively, reduce waste, and shrink the footprint per unit of production.

On the human side, the opportunity is almost hiding in plain sight. Choline is essential, yet more than 90% of Americans don’t meet recommended daily intake. As awareness grows around choline’s role in cognition, prenatal development, and liver function, the market for trusted, high-quality sources like VitaCholine—and for better delivery formats—has room to expand.

Then there’s the operating model. Balchem runs capital-intensive processes, which means fixed costs are meaningful. When volumes rise, margins can expand quickly because incremental revenue doesn’t require the same incremental cost. The company’s ongoing effort to more than double microencapsulation capacity fits neatly into that setup: invest ahead of demand, then let utilization and mix do the work.

Finally, Balchem has a well-worn lever it can keep pulling: acquisitions. It has a history of integrating deals, a balance sheet that supports it, and it operates in a specialty ingredients landscape that’s still fragmented enough to offer targets.

Put all of that together and you get the “defensive growth” version of Balchem: diversified end markets, mission-critical ingredients, and pricing power rooted in scientific differentiation rather than marketing gloss.

The Bear Case:

The same markets that make Balchem attractive also come with real pressure points. Customer consolidation is one. Mega-dairies and large feed mills have increasing negotiating leverage, and in food ingredients, the gravitational pull of giants like Walmart and Costco can squeeze suppliers in ways that have nothing to do with chemistry.

Commodity competition is another, especially in choline. Low-cost Chinese producers can create pricing pressure in parts of the market where quality and regulatory advantages matter less—or where customers decide they matter less.

Animal agriculture also has cycles, whether you want it to or not. Milk prices move. Hog cycles swing. When producer economics tighten, premium supplements become a tougher sell, even if the long-term ROI is compelling.

In Specialty Products, the elephant in the room is ethylene oxide. Environmental and health concerns—including those associated with “Cancer Alley” issues in Louisiana—can invite regulatory scrutiny, and any meaningful restriction would matter.

And then there’s execution risk. Balchem has benefited from acquisitions, but bigger deals raise the stakes: overpaying or stumbling on integration can erase value quickly.

Lastly, key person risk is real. Ted Harris has been central to strategy and momentum over the past decade, and any disruption there would be closely watched.

XIII. What to Watch: Key Performance Indicators

If you want a quick read on whether Balchem’s story is staying on track, there are three metrics that tend to tell you first.

1. Animal Nutrition & Health Segment Organic Growth Rate

This is the clearest signal of the ReaShure franchise’s underlying strength. With dairy intensification as a long-term tailwind, you’d generally expect steady, mid-single-digit organic growth in a normal environment. If that growth stalls for a sustained stretch, it’s worth asking why—whether that’s competitive pressure, weaker farm economics, or something shifting in customer behavior.

2. Human Nutrition & Health Adjusted EBITDA Margin

This margin is where Balchem’s “ingredients platform” strategy shows up on the scorecard. Expanding profitability here usually means the company is holding pricing power in its branded, science-backed portfolio and getting real operating leverage from scale and integration. If margins compress, it can be a sign that competition is getting sharper, input costs are rising faster than pricing, or the portfolio mix is moving in the wrong direction.

3. Free Cash Flow Conversion

This is the reality check. Balchem can report strong earnings, but the business is at its best when those earnings reliably turn into free cash flow. Healthy conversion funds the acquisition playbook, supports the dividend, and keeps the balance sheet flexible. If cash flow starts drifting away from reported profits, it often points to a working-capital squeeze, heavier capex, or other strains that don’t show up in the headline numbers.

XIV. Epilogue: The Next Chapter

Balchem started in 1967 in a lab above the Chemists Club. It nearly got wiped out by fires in the 1970s. Then it spent decades doing something that doesn’t sound like a growth strategy until you see the results: patiently perfecting microencapsulation and building credibility one study, one customer, one application at a time.

Now, that same core capability sits squarely in the middle of several long-running trends—better nutrition, more demanding food and supplement customers, and healthcare supply chains that cannot afford failure.

Balchem is acting like a company that believes the next decade will look a lot like the last one, just bigger. With a major expansion underway to more than double microencapsulation capacity, it’s leaning into what made it different in the first place. Management expected growth tailwinds in 2025 from continued demand for choline and vitamin K2 products, new product launches like VitaCholine ProFlow and K2 Delta fermented, and solid performance across its segments.

The next set of opportunities isn’t a single bet. It’s a menu:

- Aquaculture and alternative proteins, where nutrient delivery and stability matter as much as raw ingredients

- Sustainability solutions, including methane reduction in ruminants, as environmental pressure reshapes animal agriculture

- Personalized nutrition and bioavailability optimization, where delivery systems can justify premium pricing

- Emerging markets expansion in places like India, Southeast Asia, and Latin America, where nutrition demand grows alongside incomes

The real strategic question is the one Balchem has been answering, again and again, since ReaShure: can it turn encapsulation into more than a technology—into repeatable franchises? New products that become the default choice because they’re backed by years of research, university partnerships, and brand trust that competitors can’t manufacture on a deadline.

That’s what makes Balchem such a useful case study. The company’s products are mostly invisible to end consumers. People don’t think about Balchem when they buy infant formula, take a supplement, or open a sterile medical device package. But the invisibility is the point: Balchem doesn’t win by being famous. It wins by being embedded—qualified, trusted, and hard to replace.

Balchem was founded in 1967 and is committed to making the world a healthier place by delivering trusted, innovative, science-based solutions to the nutrition, health, and food markets. It aims to provide the service, quality, and technology that helps its customers win with their customers. And as a publicly traded company on NASDAQ under BCPC, it has built a long track record of delivering results to stakeholders.

The fire-prone encapsulation startup became a billion-dollar global leader by surviving literal flames, making uncomfortable pivots, compounding know-how in manufacturing and research, and acquiring capabilities without breaking the culture. If you want to understand how specialty ingredients businesses quietly compound value over decades, Balchem is a blueprint hiding in plain sight.

Further Reading

- Balchem Investor Relations (balchem.com/investors) — Annual reports, 10-Ks, and quarterly earnings materials straight from the source.

- Choline: An Essential Nutrient for Public Health — Nutrition Reviews’ foundational overview of why choline matters and how the science evolved.

- Journal of Dairy Science — The core peer-reviewed research on rumen-protected choline, including studies tied to ReaShure’s performance claims.

- Encyclopedia.com Balchem Corporation History — A useful timeline-style history if you want the corporate “who/when/what” in one place.

- Patent filings — The USPTO database, which shows how Balchem’s encapsulation ideas turned into protectable, repeatable engineering over time.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music