Bed Bath & Beyond: The Rise, Fall, and Bankruptcy of a Retail Icon

I. Introduction: How Did a $17 Billion Home Goods Empire Collapse?

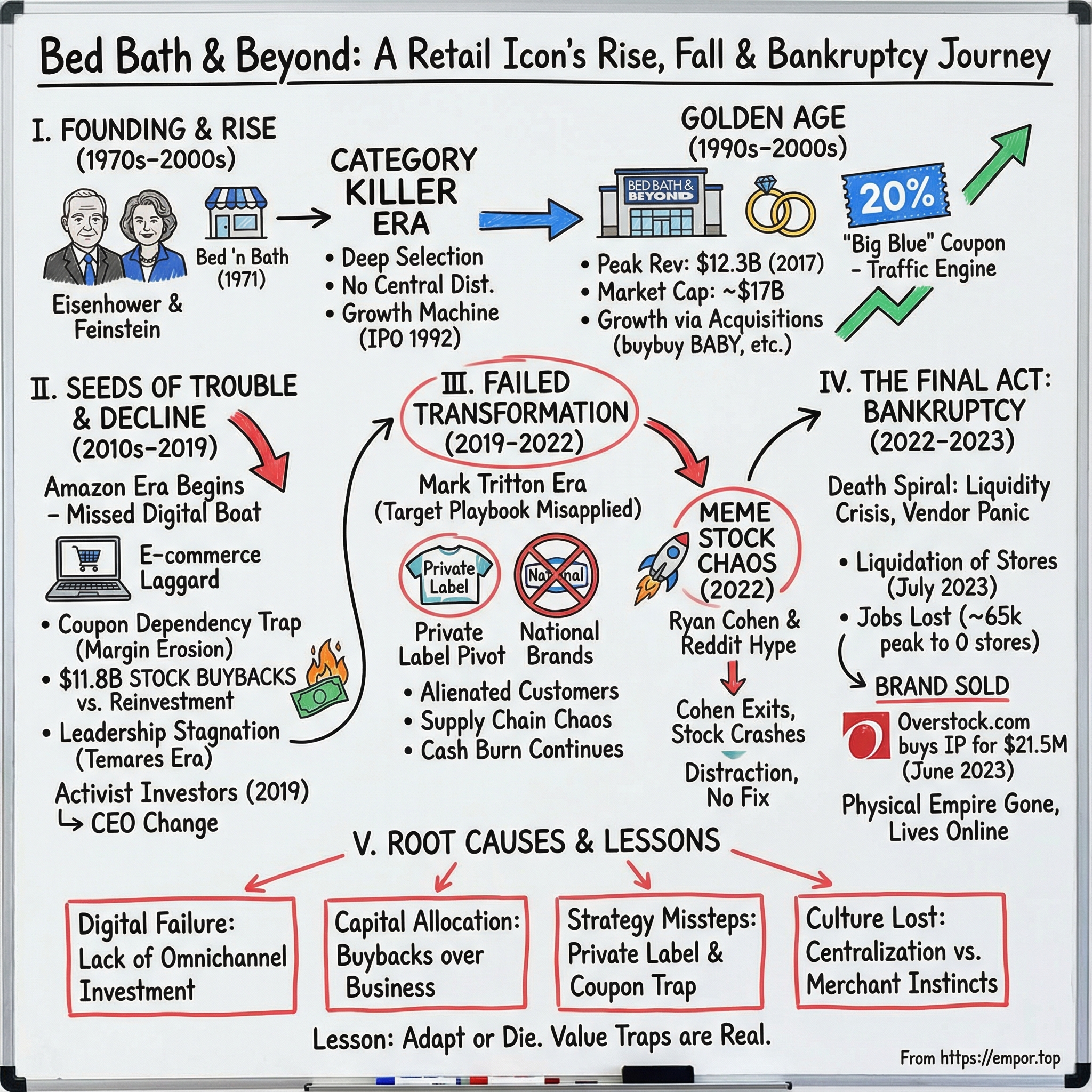

Picture the scene that played out in thousands of American strip malls: families pushing oversized blue carts past aisles packed floor to ceiling with bath towels, picture frames, coffee makers, and every oddly specific kitchen gadget you didn’t know you needed. In one hand, a familiar rectangle of paper—the “Big Blue” 20% off coupon—showing up in mailboxes with the dependability of the morning paper. For decades, Bed Bath & Beyond was where America outfitted apartments, built wedding registries, and stocked up before sending kids off to college.

Then it vanished. Bed Bath & Beyond filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in April 2023 and liquidated its remaining stores, with the last locations closing on July 30, 2023. In a June 2023 bankruptcy auction, Overstock.com acquired the Bed Bath & Beyond name and associated intellectual property through a $21.5 million stalking-horse bid.

Now sit with that for a second. A company that once reached a market capitalization near $17 billion, operated more than 1,500 stores, and employed over 65,000 people ended up reduced to a brand name and IP valued at $21.5 million. This wasn’t a trapdoor collapse. It was a slow-motion corporate death spiral—unfolding over more than a decade, visible in plain sight, and still somehow impossible to stop.

Bed Bath & Beyond was also a crown jewel of the “category killer” era—the same era that produced giants like Toys "R" Us, Circuit City, and Sports Authority. These were specialty retailers built on scale, selection, and relentless physical presence. And one by one, they fell as shoppers traded giant stores for infinite digital shelves—especially Amazon.

What makes Bed Bath & Beyond so instructive is how many classic failure modes it managed to combine in one story: activist investors, meme stock mania, $11.8 billion in stock buybacks, a disastrous private-label pivot, and a textbook case of an outsider CEO arriving with the wrong playbook for the wrong company. Underneath it all is a more human narrative too: two friends building a retail machine, a 30-year coupon strategy that turned from superpower to shackle, and the real toll when a retail empire implodes.

This is the story of how America’s favorite home goods store became a cautionary tale.

II. Founding & The Category Killer Playbook (1971–1990s)

The partnership that built Bed Bath & Beyond began the way a lot of great retail stories do: two insiders watching their employer fall apart, and realizing the future was arriving faster than the people in charge could see.

The driving force was the pairing of Leonard Feinstein and Warren Eisenberg. By 1971, both had more than a decade in the business and a buyer’s instinct for what shoppers wanted. Eisenberg, a New York City native, started as a buyer at Gimbel Brothers. Feinstein came up through Gertz, then moved on to become a merchandise manager at Arlan’s, a discount chain that was already wobbling in the early ’70s.

As Arlan’s faltered, Eisenberg and Feinstein weren’t just thinking about their next jobs—they were thinking about what would replace the old model. “We had witnessed the department store shakeout, and knew that specialty stores were going to be the next wave of retailing,” Feinstein told Chain Store Executive in 1993. “It was the beginning of the designer approach to linens and housewares and we saw a real window of opportunity.”

So they took their shot.

In 1971, they opened their first Bed ’n Bath store in Springfield, New Jersey. The initial locations were small—about 2,000 square feet—in high-traffic strip malls. They stocked recognizable brands like Cannon, Wamsutta, and Fieldcrest, alongside lower-priced options. The idea was straightforward and, at the time, quietly radical: pick a category that department stores treated as an afterthought, then win with selection and value.

Department stores carried bed and bath as one aisle among many, with limited choice and heavy markups. Eisenberg and Feinstein believed customers would happily drive past them for a specialist that felt like the authority.

But they learned quickly that being a specialist wasn’t enough. A store built only around linens and towels didn’t generate enough repeat visits—soft goods drove soft traffic. If they wanted to build something big, they needed a “beyond.”

By 1985, they had grown to 18 stores across the New York metro area and California. That same year, they made the pivot that would define the next three decades: they opened their first superstore, built to separate them from a rising wave of competition. It was more than ten times the size of the original shops—about 20,000 square feet—and it didn’t just expand the linen assortment. It broadened the mission into home furnishings across the board.

In many ways, this was the first true home furnishings superstore: a category-killer concept applied to the home.

The format broke a lot of the “rules” of traditional retail. Everything was discounted. Merchandise was stacked high in a warehouse-style presentation. Traditional advertising was minimal, leaning instead on direct mail and grand-opening campaigns. And the company even avoided central distribution centers—suppliers shipped directly to stores, a setup that made it “very, very, very difficult to do business with them.” But it also gave Eisenberg and Feinstein flexibility. They could open stores where they wanted, when they wanted, without waiting for a distribution network to catch up.

In 1987, they made it official: Bed ’n Bath became Bed Bath & Beyond. The name wasn’t just a rebrand. It was a declaration—this wasn’t going to be a towel store. It was going to be a destination for the entire home.

And behind the scenes, the engine was the founders’ relationship. Feinstein and Eisenberg served as co-CEOs, spoke daily, and were even executors of each other’s estates. Feinstein summed up the partnership in a 2000 Forbes interview: “There aren’t many good marriages out there, but when you’ve got one of the great ones, it’s wonderful.” It wasn’t a cute anecdote—it was a competitive advantage. Retail rewards speed, trust, and decisive merchandising calls, and they had built a working rhythm that lasted decades.

In June 1992, Bed Bath & Beyond went public on the NASDAQ at $17 per share. The IPO came with 38 stores and roughly $200 million in revenue, and it immediately landed with Wall Street. Media coverage was strong, and a new Manhattan store helped signal that this wasn’t just a suburban strip-mall concept.

The market loved the story. Analysts said the timing was ideal given the popularity of the merchandising model they were championing. By May 1993, the stock traded around $32 as the company reported record results: $216.7 million in sales and $15.9 million in earnings.

Bed Bath & Beyond wasn’t just growing—it was starting to look inevitable.

III. The Golden Age: Dominating Home Goods Retail (1990s–2000s)

If the early years proved Bed Bath & Beyond’s model could work, the 1990s and 2000s proved it could scale. What started as a regional specialty retailer became a national institution—one of the defining category killers of its era.

After going public in 1992, growth came fast. Revenue crossed $1 billion by 1999, and the store base marched outward through the suburbs. The company hit its 100th location by 1996, cleared 200 stores by 1999, and kept going—largely through new builds in high-traffic shopping centers where the format thrived.

By the time the new millennium arrived, Bed Bath & Beyond had more than 250 stores, had planted flags in states from Rhode Island to Idaho, and had done it with a balance sheet that made competitors jealous. The company operated with no debt, funding expansion with cash flow. Wall Street loved the story: the stock climbed steadily through the 1990s, and in July 2000, the company announced a two-for-one stock split. By year-end, it had topped $2 billion in sales and grown past 300 stores across 43 states.

But the real magic wasn’t just the footprint. It was what it felt like to shop there.

Bed Bath & Beyond stores were cavernous, packed floor-to-ceiling with towels, bedding, cookware, and every oddly specific home gadget you could imagine. The layout was intentionally open and maze-like—less “get in, get out,” more “wander and discover.” People came in for a set of dishes and left with pillows, bath mats, and a new coffee maker they didn’t plan on buying.

And then there were the coupons.

The blue-and-white 20% off “Big Blue” coupon became a cultural artifact—something people stuffed in glove compartments, kitchen drawers, and junk boxes “just in case.” The strategy was elegantly simple: mail a sweeping discount that got customers in the door, then count on the cart to fill up with plenty of full-price items. For years, it worked exactly as intended, helping turn routine errands into high-margin treasure hunts.

The company also locked itself into some of the most emotionally charged shopping moments in consumers’ lives: wedding registries and baby registries. These weren’t just transactions—they were life milestones. They drove big baskets, repeat visits, and a kind of loyalty that normal retail just doesn’t get. Bed Bath & Beyond became a seasonal ritual too: winter holidays, back-to-school, and college move-in were prime time for those oversized blue carts.

As the core business surged, the company expanded “beyond” through acquisitions that pushed into adjacent categories. Harmon Face Values arrived in March 2002. Christmas Tree Shops followed in 2003. buybuy BABY was acquired in March 2007. Cost Plus World Market was acquired in May 2012. Along the way, Bed Bath & Beyond built out a portfolio that included beauty and seasonal specialty retail alongside the mothership.

Underneath all of this was a founder-era operating style that fit the business perfectly: decentralized decision-making, merchant judgment, and a relentless focus on the customer experience. That culture—paired with the company’s scale and productivity—helped drive strong margins and a low-cost structure.

Wall Street rewarded the consistency. For years, Bed Bath & Beyond became known as the kind of company that simply did not miss—posting a long run of earnings that met or beat expectations as the broader U.S. economy boomed. It was a point of pride, and it became part of the brand’s identity.

It also planted a seed that would matter later: when “never missing” becomes the goal, the temptation grows to manage the numbers instead of rebuilding the business.

And while the golden age is usually thought of as the ’90s and 2000s, the growth machine kept running well into the next decade. Bed Bath & Beyond’s peak revenue was $12.3 billion in 2017. By around that same peak, with roughly 1,560 locations, it had gone from two friends’ strip-mall experiment to an empire spanning nearly every American suburb.

IV. Seeds of Trouble: The Amazon Era Begins (2005–2012)

Even as Bed Bath & Beyond celebrated record quarters and kept planting new stores in strip malls across America, the ground under retail was already moving. The seeds of the company’s collapse weren’t planted in a crisis. They were planted in what looked like the good years.

Years later, founder Warren Eisenberg would put it bluntly in a Wall Street Journal interview: “We missed the boat on the internet.” That single sentence explains a lot. Over the 2010s, customers didn’t stop buying towels and blenders. They just started buying them online—from Amazon and a growing list of other sellers offering the same branded goods with easier search, faster shipping, and increasingly competitive prices.

This was the core vulnerability of the Bed Bath & Beyond model in the internet era. In the 1980s and 1990s, “deep selection” meant something. If you wanted the good toaster oven or the right thread-count sheets, a specialist with packed shelves could beat a department store. But online made selection feel infinite everywhere. The endless aisle moved from the store to the screen.

And Bed Bath & Beyond’s digital presence lagged. While Amazon was training consumers to expect frictionless ordering and building a fulfillment machine to match, Bed Bath & Beyond kept acting like the center of the universe was still the big-box store. Capital and attention flowed to leases, new locations, and keeping the physical engine humming.

The leadership transition didn’t help. In 2003, the founders stepped back from day-to-day control into co-chairmen roles, and Steven Temares took over as CEO. Temares wasn’t a merchant by background; he came up through the company as a real estate lawyer, then ran real estate and legal, and later served as COO before becoming chief executive. He knew the company inside and out, and under his watch Bed Bath & Beyond kept expanding—eventually growing to more than 65,000 employees and around $12 billion in annual revenue.

But the skill set that helped Bed Bath & Beyond scale its footprint wasn’t the one it needed as the industry pivoted. The 2000s and early 2010s demanded a reinvention around technology, e-commerce, and omnichannel logistics. Bed Bath & Beyond largely stayed the course.

By 2012, the change showed up in the numbers. Growth began to flatten, and what had been a machine of steady momentum started to look mortal. Same-store sales slowed. The old playbook still worked—just less and less each year.

And the famous coupon strategy, once a near-perfect traffic generator, started to lose its edge. Online shopping made price comparison effortless. Competitors leaned into price matching. Customers learned to treat the 20% off as a baseline, not a bonus. Bed Bath & Beyond had trained an entire generation to wait for a discount—and by the time the market shifted, it was too dependent on coupons to simply walk away.

So the company got squeezed from both sides. The category-killer advantage eroded as Amazon made “selection” universal, and the coupon engine weakened as transparency made discounts feel mandatory.

The model that had once disrupted department stores was now being disrupted itself—and by 2012, the warning lights were already flashing.

V. The Decline Accelerates: Death by a Thousand Cuts (2012–2019)

From 2012 to 2019, Bed Bath & Beyond didn’t implode all at once. It bled out—slowly, predictably, and in public. This was the era when the company kept choosing the short-term move over the long-term fix, and when the strengths that once made it a category killer turned into liabilities.

Nothing captures that tradeoff better than the buybacks.

Over the years leading up to bankruptcy, Bed Bath & Beyond poured an enormous amount of cash into repurchasing its own stock—about $11.8 billion since 2004, according to financial filings. Put differently: it spent roughly twice what it later carried in debt when it finally filed for Chapter 11. This was money that could have gone into the unglamorous but essential work of survival in modern retail—e-commerce, better systems, upgraded distribution, refreshed stores.

The details make it worse. The company bought back about 264.7 million shares at an average price north of $44 per share. By the time this story reached its endgame, the stock was trading for only a few dollars. That’s not just bad timing. It’s a strategic choice repeated for years: returning cash to shareholders while the business model underneath was cracking.

And yes—Amazon and online competitors were taking share regardless. Bed Bath & Beyond had been slow to treat e-commerce as existential. It kept building and operating big stores, leaning on a playbook from the 1990s while customers were quietly moving to search bars, fast shipping, and easy returns. The buybacks didn’t create the disruption, but they starved the company’s ability to respond to it.

At the same time, the coupon machine that once fueled the whole empire started working against them. The 20% off offer had been a brilliant traffic driver, but over time it trained customers to treat the discount as the real price. Full price began to feel like a markup. Margins tightened, promotions escalated, and the brand’s value proposition got muddier by the year.

“The coupon was both its greatest strength and weakness,” UBS retail analyst Michael Lasser said.

By 2019, performance had deteriorated enough that activists smelled blood in the water. In March of that year, Legion Partners, Macellum Advisors, and Ancora Advisors went public with a campaign to remove CEO Steven Temares and reshape the board. Their critique wasn’t subtle: long-term underperformance, weak governance, and what they described as nepotism—pointing to deals like buybuy BABY (founded by two of co-founder Leonard Feinstein’s children) and Chef Central (created by co-founder Warren Eisenberg’s son) as examples of questionable decision-making.

The pressure worked. On April 22, 2019, five independent directors stepped down.

The activists also pinned a big number to the storyline: they said the company had destroyed more than $8 billion in market value during Temares’ tenure, and that the stock had fallen more than 80% from early 2015 to 2019. The broader picture matched: comparable sales were sliding, costs were rising, and the stock had fallen sharply from its highs earlier in the decade to roughly $10 by late 2018.

Eventually, the board did what it had delayed for years. In late May 2019, Bed Bath & Beyond announced that Steven Temares was stepping down as CEO, effective immediately. Mary Winston, newly appointed to the board, was named interim CEO.

And hovering over all of it was the kind of governance optics that poisons trust fast: Temares’ compensation. From 2006 through 2017, he realized $172,655,854 in pay, including stock and options.

That’s the ugly contradiction at the heart of this chapter: a company shrinking, a stock collapsing, and a leadership structure still paying out like the good times would never end.

VI. The Transformation That Wasn't: Mark Tritton Era (2019–2022)

With Steven Temares out, the board went hunting for a savior—someone with a modern retail pedigree who could drag Bed Bath & Beyond into the omnichannel era. They landed on Mark Tritton, and the market loved the hire.

Bed Bath & Beyond announced Tritton as president and CEO effective November 4, 2019, replacing interim CEO Mary Winston. His pitch, straight from the press release, was tailor-made for what the company supposedly needed: more than 30 years in retail, most recently as Target’s chief merchandising officer, where he helped reshape the company’s omnichannel experience and led a major overhaul of Target’s private-label strategy—reviving existing brands and launching more than 30 new ones in about two and a half years.

On paper, Tritton was the exact kind of operator you hire when you think the problem is merchandising discipline and brand strategy. At Target, he had been associated with private-label brands that became huge businesses. Before that, at Nordstrom’s Product Group, he ran a massive portfolio of private-label brands across design, manufacturing, marketing, and distribution.

The board believed it had found a retail maestro. The stock jumped. Analysts talked about a turnaround.

But there was a basic flaw in the thesis: the playbook that worked at Target did not map cleanly onto Bed Bath & Beyond.

Target is a curated mass merchant with a tight assortment and a strong private-label identity. Bed Bath & Beyond, at its peak, was a specialist destination—built on breadth, recognizable national brands, and the psychological comfort of that endless blue coupon. Trying to “Target-ize” the experience meant ripping out pieces of the model customers actually came for.

Tritton moved fast—and in a way that signaled he was going to remake the company, not gently evolve it. Within weeks of starting, and right in the middle of the holiday season, he pushed out a swath of senior leadership, including executives overseeing merchandising, marketing, digital, and legal.

Then came the centerpiece: owned brands.

Between early 2020 and mid-2022, Bed Bath & Beyond introduced nine major house-brand lines. Starting in early 2021, the company rolled out names like Nestwell, Simply Essential, and Wild Sage, and relaunched Haven. The strategy was clear: pull back from national brands, grow margins with private label, and make Bed Bath feel more “designed.”

In later litigation, Tritton argued that this wasn’t just his personal crusade—it was the job he was hired to do. He said the company made clear he was expected to replicate his Target success, with private label at the center. The suit also conceded the dark side of that decision: shrinking the vendor base and leaning harder on owned brands left the company more exposed when supply chain disruptions hit.

And the execution didn’t match the ambition. Critics said the quality didn’t hold up, price points felt too high for what customers were getting, and too much of the assortment felt like generic product with a new label slapped on. Private label can be a powerful strategy—but only if the product is truly differentiated and customers trust it.

Worse, the pivot damaged relationships with the national brands that had anchored the business for decades—the Cuisinarts, KitchenAids, and Oxos that shoppers actually walked in asking for. During the holiday 2021 season, Bed Bath & Beyond was missing many of its best-selling items, including key appliances and personal electronics—exactly the kinds of products that drive traffic and fill carts. Supply chain chaos hurt plenty of retailers, but Bed Bath & Beyond had chosen the moment to narrow its vendor bench and overhaul the assortment. It made the company unusually vulnerable.

At the same time, Tritton tried to dial back the thing that had functioned as the company’s heartbeat: coupons. Target never needed them. Bed Bath & Beyond had trained customers for decades to expect them. In 2020, the company said it had become overly reliant on discounting. But within two years, executives would publicly concede that scaling back the coupon cadence had been a “big mistake.” They had misread just how much the “Big Blue” coupon was acting as a reminder—and a reason—to visit.

Then came the self-inflicted wound that spooked the people Bed Bath needed most: its suppliers.

Even as the turnaround demanded investment in inventory, systems, and supply chain resilience, Bed Bath & Beyond kept sending cash out the door through buybacks. In 2021, the company spent $625 million repurchasing shares. In November 2021, it announced it was accelerating buybacks further, including spending hundreds of millions more over the next two quarters—this after reporting a net loss and a decline in comparable sales.

From a supplier’s perspective, that’s not “returning capital.” That’s a warning flare. If you’re shipping blenders and bedding to a retailer on credit, and you see it burn through cash buying its own stock, you start to wonder whether you’ll get paid. Bed Bath & Beyond’s finance chief, Gustavo Arnal, later said the buybacks created concern among vendors, who feared the company wouldn’t have enough cash to pay them in full. Some responded by scaling back shipments—leading to even emptier shelves, more frustrated customers, and less revenue. The spiral feeds itself.

And this all happened during a period that should have been a gift. The pandemic created a historic surge in home-goods spending as Americans upgraded kitchens, bedrooms, and home offices. Retailers like Target and Wayfair benefited. Bed Bath & Beyond, unbelievably, missed much of the moment because it was mid-overhaul—swapping out familiar brands, changing promotions, and struggling to keep core items in stock.

By the spring of 2022, the numbers reflected the damage. In the first quarter of 2022, losses ballooned and sales dropped sharply from the year before, with comparable sales falling dramatically across the chain—and even more at the core Bed Bath & Beyond banner.

The board finally pulled the plug. In June 2022, after just over two and a half years, Tritton stepped down as CEO, president, and board member. Sue Gove, a director since 2019 and chair of the board’s strategy committee, took over as interim CEO.

Tritton had arrived as the high-profile outsider with the modern retail answer. He left behind something worse than a declining business: a confused assortment, alienated customers, rattled suppliers, and a company that had burned precious time and cash trying to become something it was never built to be.

VII. The Meme Stock Saga & Ryan Cohen Chaos (2022)

By the time Bed Bath & Beyond fired Mark Tritton and put Sue Gove in the interim CEO chair, the business was already in triage. Shelves were thinning, vendors were nervous, and the turnaround story was running out of oxygen.

And then, out of nowhere, the stock became the story.

The meme-stock wave that had launched GameStop and AMC into financial absurdity in 2021 rolled on to a new target: Bed Bath & Beyond. The setup was familiar—heavy short interest, a collapsing legacy retailer, and a retail-investor crowd eager for another squeeze. Trading volume exploded. On Reddit’s WallStreetBets, BBBY started dominating the conversation, even as the company’s fundamentals kept deteriorating in real time.

Into that frenzy walked Ryan Cohen.

In March 2022, Cohen—Chewy co-founder and GameStop chairman—disclosed that his firm, RC Ventures, had taken a 9.8% stake in Bed Bath & Beyond. He had accumulated more than 7 million shares and call options, buying in at an average price of roughly $15.34 per share. He followed it with a public letter that sounded, at least on the surface, like a conventional activist play: narrow the company’s focus, fix operations and inventory, and explore strategic alternatives, including separating buybuy BABY or even selling the whole company.

Bed Bath & Beyond moved quickly. After Cohen threatened a proxy fight, the company entered into a cooperation agreement with him. Cohen got three seats for his picks on the board, plus significant influence through a newly created strategy committee. For retail investors, it looked like the cavalry had arrived—another “activist savior” who might force the company into a big, value-unlocking move around buybuy BABY.

But Cohen wasn’t there to run a turnaround. He was there to trade.

In August 2022, after a sharp run-up that sent the stock surging from its summer lows, RC Ventures dumped everything—shares and call options—selling at prices ranging roughly from the high teens up to the high twenties per share. In filings, the total sale came out to about $189 million. The profit was widely reported as roughly $68 million, a gain of around 56% on a position held for about seven months.

The timing was the twist of the knife. Cohen disclosed the completed exit on August 18, 2022, after the market closed. Over the next three trading days, Bed Bath & Beyond’s stock dropped about 40% as retail investors processed what had happened: the person many believed was going to “save” the company had already left.

The blowback got ugly fast. Lawsuits followed. One January 30, 2023 complaint alleged Cohen manipulated the market and engaged in insider trading, using social media-driven hype to maximize the price before quietly selling his entire position. Whether those allegations ultimately held up or not, the damage was real: it reinforced the sense that BBBY had become a casino chip, not a retailer.

And the company didn’t even get the upside you’d hope for from a meme-stock spike. Yes, the stock price had briefly levitated. But it didn’t refill shelves. It didn’t calm suppliers. It didn’t fix broken systems or an unraveling assortment. If anything, the whiplash made Bed Bath & Beyond look even more unstable to the people whose trust it needed to survive.

Because underneath the memes and the message boards, the real crisis was still there: cash.

Liquidity was drying up, and the company needed new capital to keep operating. By its fiscal first quarter, Bed Bath & Beyond reported roughly $108 million in cash and equivalents—down from about $1.1 billion a year earlier. The market spectacle hadn’t bought them time. It had just turned the collapse into a public sport.

And now, with vendors tightening terms and lenders staring at the balance sheet, Bed Bath & Beyond was about to enter the final phase of the death spiral.

VIII. The Final Act: Bankruptcy & Liquidation (2022–2023)

With Cohen gone, Tritton out, and cash evaporating, Sue Gove inherited an impossible hand. The company was already in the classic retail death spiral: vendors tightening terms and demanding cash up front, shelves thinning out, customers drifting away, and creditors watching every move.

Then the crisis turned personal. On September 2, 2022, CFO Gustavo Arnal died by suicide after jumping from the balcony of his New York City apartment. At the time, he was also one of the targets in a class action lawsuit tied to allegations that Bed Bath & Beyond’s stock had become a pump-and-dump scheme. Two weeks later, on September 16, the company named 56 stores it planned to close—another sign that the business was no longer trying to grow its way out, but shrink fast enough to survive.

It didn’t.

Bed Bath & Beyond began 2023 warning investors, bluntly, that it might not make it through the year. On January 5, 2023, shares plunged nearly 30%, and the company disclosed there was “substantial doubt” about its ability to continue operating.

From there, the moves got more frantic. The company hunted for financing anywhere it could find it. By February 2023, it was on the brink of bankruptcy before it arranged a complex financing deal with Hudson Bay Capital Management. It wasn’t a durable lifeline. Another attempt to raise $300 million through a stock offering also failed to materialize.

At the end of March, Bed Bath announced yet another stock offering it hoped would raise $300 million. Instead, the news sent the share price tumbling, making the raise even harder. By April 10, the company had sold about 100.1 million shares and raised only $48.5 million—nowhere close to what it needed.

On April 23, 2023, Bed Bath & Beyond Inc. and 73 affiliated debtors filed voluntary Chapter 11 petitions in the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the District of New Jersey.

The bankruptcy filings laid out the scale of the wreckage. As of late November, court documents showed roughly $4.4 billion in assets against $5.2 billion in debts. The creditor list was long—vendors included Pinterest, Keurig, and Blue Yonder—and the biggest obligation was to BNY Mellon at $1.18 billion. Bed Bath listed between 25,001 and 50,000 total creditors and about 14,000 non-seasonal workers.

“Bed Bath and Beyond has finally succumbed to the fact its business is broken and filed for bankruptcy,” said Neil Saunders, managing director of GlobalData. “While it has been a long time coming,” he added, “they simply could not defy gravity forever.”

The immediate reason for Chapter 11 was brutally simple: the company could no longer do the two things a retailer must do to stay alive—pay its bills and keep products on shelves. As interim CFO and chief restructuring officer Holly Etlin wrote in court papers, the retailer “is simply unable to service its funded debt obligations while simultaneously supplying sufficient inventory to its store locations.”

A year earlier, the company still had about 955 stores and tens of thousands of employees. After months of accelerated closures, it entered bankruptcy with about 360 Bed Bath & Beyond stores and 120 buybuy BABY locations remaining.

The end came fast. Bed Bath said those stores would remain open for liquidation sales but would close over time. Starting Wednesday, April 26, the chain would stop accepting coupons and discounts—and all sales would be final. The iconic “Big Blue” coupon, the symbol of the whole empire, didn’t even make it to the credits.

Bed Bath & Beyond liquidated its remaining stores, with the last locations closing on July 30, 2023. In the aftermath, the brand itself—separate from the stores—was sold off. Overstock.com acquired Bed Bath & Beyond’s trademarks and related intellectual property in a bankruptcy auction.

The assets Overstock bought included the website and domain names, trademarks and tradenames, patents, the customer database, loyalty program data, and other brand assets tied to the Bed Bath & Beyond banner. The U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the District of New Jersey approved Overstock’s winning bid at a sale hearing on June 27, 2023. The deal excluded anything tied to the physical retail machine—store leases, inventory, warehousing, and logistics infrastructure—and it also excluded the buybuy BABY and Harmon banners. The price: $21.5 million.

It’s hard to find a cleaner epitaph. Bed Bath & Beyond spent $11.8 billion buying back its own stock. And in the end, the entire brand—everything that had once stood for those towering towel aisles and packed wedding registries—sold for $21.5 million.

“This is a historic day for Bed Bath & Beyond and Overstock — and for the broader ecommerce industry,” said Overstock CEO Jonathan Johnson. “Overstock has a great business model with a name that does not reflect its focus on home. Bed Bath & Beyond is a much-loved and well-known consumer brand, which had an outdated business model that needed modernizing.”

Overstock officially relaunched its U.S. e-commerce site as Bed Bath & Beyond that Tuesday, following its June 28 purchase of the intellectual property out of bankruptcy.

The physical stores were gone. The jobs—more than 65,000 at peak, about 14,000 at the end—were gone too. The name lived on, but only as a digital shell: a familiar sign bolted onto a very different business than the category killer that once dominated American retail.

IX. Why BBBY Failed: The Root Causes

Bed Bath & Beyond didn’t go bankrupt because of one bad quarter or one unlucky bet. It went down the way a lot of big retailers do: a slow accumulation of bad decisions—strategic, financial, and cultural—that eventually left the company with no room to maneuver.

The Digital Transformation Failure

If you zoom out, the central problem was relevance. GlobalData managing director Neil Saunders put it plainly: “If there is a single point of failure of Bed Bath and Beyond, it’s that the company stopped being relevant to consumers.” As online shopping surged and rivals like Target sharpened their home-goods assortments, Bed Bath’s experience started to feel tired—“which lacked inspiration,” Saunders said—and customers had more convenient options everywhere.

Even the founders admitted what happened. “We missed the boat on the internet.” And in retail, being late to a platform shift isn’t like being late to a product cycle. It’s existential. By the time Bed Bath & Beyond tried to get serious about e-commerce, competitors had already spent a decade training customers on faster shipping, better search, and easier purchasing habits.

The Capital Allocation Catastrophe

Then there’s the money. Since 2004, Bed Bath & Beyond spent about $11.8 billion repurchasing its own stock—more than twice the debt it ultimately carried on its books.

That choice matters because retail is a business that demands constant reinvestment: systems, stores, inventory, logistics, digital. A stronger balance sheet could have bought the company time to adjust and fund a real turnaround. Instead, years of buybacks drained flexibility. When the environment tightened and performance slipped, the company didn’t have the cushion to absorb shocks—it had to slash and scramble, which only accelerated the decline.

The Private Label Disaster

The next self-inflicted wound was the private-label pivot. Under CEO Mark Tritton, who arrived in late 2019 after running Target’s store-brand strategy, Bed Bath & Beyond pushed hard into owned brands. The customer experience changed overnight: shoppers walked in expecting recognizable name brands and found unfamiliar labels instead.

The timing couldn’t have been worse. As supply chain disruptions hit the industry in 2021, Bed Bath & Beyond had already destabilized its vendor relationships and narrowed its assortment. As one critique noted, “While many US retailers had to deal with similar supply chain shortages over the course of 2021, Bed Bath & Beyond’s ill-timed shift in strategy compounded the retailer’s woes to a remarkable degree.” In other words: everyone got punched, but Bed Bath walked into the fight with its hands down.

The Coupon Dependency Trap

And then there was the thing that made the brand famous: the 20%-off “Big Blue” coupon.

For decades it was a brilliant traffic engine. But over time, it trained customers to treat “20% off” as the real price. As the retail landscape evolved and price comparison became effortless, the coupon stopped being a delightful bonus and started functioning like a permanent markdown—dragging on margins and weakening pricing power.

As one observer put it: “It’s a very effective short-term strategy in terms of generating sales, but coupons are not good for long-term loyalty.”

The Category Killer Curse

Finally, Bed Bath & Beyond was a victim of its own era. It was built as a “category killer,” the same model that powered chains like Toys “R” Us, Circuit City, and Sports Authority—big footprint, huge selection, and dominance through physical presence. Many of those companies ultimately ended up in bankruptcy too, as consumers migrated from giant specialty stores to the infinite shelf online.

The model that made Bed Bath & Beyond great—deep selection in a physical location—became far less special when Amazon could offer endless variety without the drive to the strip mall.

X. Strategic Frameworks Analysis

Porter's Five Forces: A Decade of Deterioration

Threat of New Entrants

In 2010, breaking into big-box home goods was hard. You needed capital, real estate know-how, and the supplier relationships to keep shelves full. By 2020, those barriers had cratered. Wayfair showed you could build a home-goods giant without stores. Direct-to-consumer brands popped up on Instagram with minimal upfront investment. The old physical-retail moat that had protected Bed Bath & Beyond for decades wasn’t just shrinking—it was gone.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers

This relationship flipped. In 2010, Bed Bath & Beyond had real leverage: if you were a supplier, getting onto its shelves meant access to a huge customer base. By 2022, suppliers held the cards. Many demanded cash up front, cut shipments, and favored steadier partners like Amazon and Walmart. Once the balance sheet started wobbling, the supplier relationship stopped feeling like a partnership and started feeling like a risk calculation.

Bargaining Power of Buyers

The internet handed customers the ultimate negotiating tool: instant price transparency. The 20% coupon that once felt like a perk became far less compelling when Amazon could offer competitive pricing every day with fast delivery. With alternatives a click away, loyalty thinned out fast.

Threat of Substitutes

In the 2010s, substitutes didn’t just appear—they flooded the zone. Amazon and Wayfair grabbed the online customer. Target kept upgrading its home assortment. HomeGoods and the broader TJX ecosystem offered a more exciting treasure-hunt experience. Meanwhile, direct-to-consumer brands multiplied. Bed Bath & Beyond wasn’t losing to one rival. It was getting boxed in by many, each with a sharper hook.

Industry Rivalry

Competition went from “tough but manageable” to all-out war. When Linens ’n Things went bankrupt in 2008, Bed Bath & Beyond briefly looked like it had won the category. By 2020, it was fighting everywhere at once—against e-commerce giants, mass merchants, off-price players, and the broader decline in retail traffic. And unlike earlier eras, there was no easy lever left to pull.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: Bed Bath & Beyond once benefited from scale in physical retail—purchasing power and distribution advantages. But as traffic declined, that same scale turned into a trap: rent, labor, and inventory are fixed costs that don’t shrink gracefully. Amazon, meanwhile, built scale where it mattered in the new era: digital logistics and customer acquisition.

Network Effects: Wedding registries created a form of network effect—people registered where friends had registered. But those effects weakened as registries moved online and became easy to replicate anywhere, while Amazon’s Prime ecosystem created stronger stickiness.

Counter-Positioning: Bed Bath & Beyond originally counter-positioned department stores: bigger selection, better value, more focus. Then Amazon and Wayfair counter-positioned Bed Bath & Beyond with a no-stores, infinite-selection model. BBBY couldn’t fully answer without undermining its own footprint—a classic Innovator’s Dilemma.

Switching Costs: In home goods, switching costs are almost nonexistent. The closest thing Bed Bath & Beyond had was registry “lock-in,” and even that faded as registries became portable across platforms.

Branding: For years, the brand stood for registries and the iconic 20% coupon. But over time, brand equity eroded through merchandising missteps—and by 2022, “Bed Bath” increasingly read as shorthand for “dying retailer.”

Cornered Resource: Prime retail locations were an early edge, until they became a burden in a world of declining in-store traffic. And there was no scarce resource here that couldn’t be matched—or bypassed—online.

Process Power: The company’s early advantage came from merchant expertise and a decentralized culture that let stores respond to customers. That differentiation faded, and then was actively dismantled when operations were centralized and the merchant culture was stripped out.

Conclusion: By 2020, Bed Bath & Beyond effectively had none of Hamilton’s 7 Powers left. The advantages that once made it formidable either eroded, were mismanaged, or flipped into liabilities—and that’s why the decline wasn’t just likely. It was hard to stop.

XI. Lessons & The Bigger Picture

For Founders & Operators

Digital transformation isn’t optional—it’s existential. Bed Bath & Beyond had years to build real e-commerce and omnichannel muscle before COVID poured gasoline on digital adoption. Instead, it chose buybacks over reinvestment, and financial engineering over the hard work of rebuilding the business for a new era.

Culture eats strategy. The merchant culture Eisenberg and Feinstein built—decentralized buying, entrepreneurial store leaders, and a constant bias toward the customer—wasn’t a soft, feel-good detail. It was the operating system. When Tritton centralized decisions and tried to impose a different model, the company didn’t just change strategy; it lost the instincts that had made it great. The retailer that once seemed to “get” shoppers started making choices that told customers it no longer did.

Know when your moat is eroding. The category-killer formula was perfect for a pre-internet world: huge selection, strong brands, and a convenient suburban footprint. But when the internet made selection infinite and convenience door-to-door, the advantage flipped. The response needed to be an aggressive pivot. Bed Bath & Beyond largely doubled down on the old machine.

For Investors

Beware value traps. For years, Bed Bath & Beyond looked “cheap” on traditional valuation metrics. But cheap isn’t the same as safe. When a company’s competitive position is collapsing, low multiples can be a warning sign, not an opportunity.

Capital allocation reveals management quality. Bed Bath & Beyond spent $11.8 billion buying back stock at an average price above $44 per share while underinvesting in digital capabilities and modernization. That isn’t just a bad outcome. It’s a message about priorities—and about whether leadership is building for the future or managing for the quarter.

The meme stock phenomenon is gambling, not investing. Ryan Cohen’s widely reported $68 million profit didn’t come from fixing shelves, rebuilding systems, or earning customers back. It came from trading a story—one that many retail investors believed would end in a rescue that never arrived.

The Category Killer Graveyard

Bed Bath & Beyond joined a crowded cemetery: Circuit City, Borders, Toys "R" Us, Sports Authority, Linens 'n Things. The pattern is painfully consistent. Specialized big-box retailers that once won through physical scale and selection got outflanked by digital generalists that offered more choice, sharper pricing, and radically more convenience.

The survivors—Home Depot and Best Buy—didn’t “wait and see.” They invested early and aggressively in omnichannel, treating stores as assets in a digital strategy, not relics competing against it. Bed Bath & Beyond never truly made that transition.

Target vs. Bed Bath & Beyond: Similar Challenges, Radically Different Outcomes

Target and Bed Bath & Beyond both lived through Amazon’s rise. Both faced the same consumer shift toward digital. Both, at different times, had Mark Tritton in major leadership roles.

But Target spent heavily on the unsexy fundamentals: supply chain modernization, store remodels, and digital integration. It leaned into ship-from-store, curbside pickup, and same-day delivery. It built distinctive private labels without ripping out the national brands customers expected.

Bed Bath & Beyond did the opposite. It prioritized buybacks over reinvestment, swapped out familiar national brands for underdeveloped private labels, and arrived late to the digital fight.

Same industry. Same threats. Radically different outcomes—driven less by luck than by choices.

XII. Epilogue & Current State

“We didn’t purchase any leases for the Bed Bath & Beyond stores because we think it’s an outdated business model, and it’s a big expense that one is having to pass along to customers in the form of higher prices,” Overstock CEO Jonathan Johnson said. “So we never say never to physical stores, but it’s never for now.”

That choice tells you what Bed Bath & Beyond became in the end: not a retailer you walk into, but a name you type into a browser.

Overstock rebranded its business under the Bed Bath & Beyond banner after acquiring the company’s intellectual property out of bankruptcy in June. Visit Overstock in the U.S., and it redirects you straight to BedBathAndBeyond.com—now stocked with an expanded online assortment of home goods.

Overstock said it added more than 600,000 items, primarily across bed, bath, and kitchen, to the new website. It also reinstated loyalty points for customers who were part of Bed Bath & Beyond’s rewards program.

But one artifact of the old empire didn’t make the jump: the Big Blue coupons. The discounts that defined the in-store experience for decades can’t be used on the new site.

The legal story didn’t end with the liquidation either. Six weeks after Judge McFadden denied Cohen’s motion to dismiss, The Wall Street Journal reported that the SEC was investigating Cohen over his ownership and trades of Bed Bath & Beyond stock.

And the most fought-over asset in the final stretch—buybuy BABY—found a buyer, but not the kind of outcome that ever could have saved the parent company. buybuy BABY was sold to New Jersey-based Dream on Me for $15.5 million, with plans to reopen up to 120 stores over the next few years.

For the rest of the home-goods market, Bed Bath & Beyond’s disappearance didn’t create a vacuum for long. Bank of America analyst Curtis Nagle pointed to the obvious winners from the wind-down: Walmart, Amazon, and Target. He also highlighted Wayfair, Overstock, and Williams-Sonoma as smaller players positioned to pick up share.

Still, the most visible remnants aren’t in earnings reports. They’re the empty boxes in suburban strip malls—the places where the brand once lived in physical space. More than 65,000 jobs at peak, down to about 14,000 at the end, and then zero in the stores. Vendors left holding the bag. Communities losing an anchor tenant. A 52-year institution reduced to a URL.

The hardest part is that none of this was mysterious. Bed Bath & Beyond’s failure was preventable. The warnings were there for years: digital disruption, a dated store experience, weakening vendor relationships, an urgent need to invest in systems and e-commerce. The company had resources. It spent $11.8 billion on buybacks.

It simply chose not to.

That’s what makes this story sting. This wasn’t just a tragedy of circumstances. It was a tragedy of choices—by boards, executives, and investors who kept prioritizing short-term stock dynamics over long-term reinvention. Customers lost a treasure-hunt destination. Employees lost careers. Suppliers lost a major partner.

The Bed Bath & Beyond name may live on online, but the company Warren Eisenberg and Leonard Feinstein built in a Springfield, New Jersey strip mall in 1971—the category killer that once defined home-goods retail—is gone.

What remains is the case study: a warning to every retailer staring down a platform shift, every board tempted to financial-engineer its way out, and every executive convinced that a strategy that worked somewhere else will automatically work here.

A $17 billion empire ended as a $21.5 million brand sale. That’s the Bed Bath & Beyond story—and the lesson travels far beyond towels and toaster ovens.

XIII. Key Metrics for Ongoing Monitoring

If you’re looking at other retailers that rhyme with this story, there are three numbers that usually start flashing red long before the bankruptcy filing.

1. Same-Store Sales Growth: This is the heartbeat. When same-store sales go negative and stay there, it’s the market telling you customers are choosing somewhere else. Bed Bath & Beyond ran that pattern for years before it finally broke.

2. E-commerce Penetration vs. Competitors: It’s not enough to be “doing e-commerce.” The question is whether digital is becoming a real engine of the business at the same pace—or faster—than the category leaders. If competitors are moving online and you’re not, you’re not standing still. You’re falling behind.

3. Capital Allocation Ratio (Investment vs. Buybacks): Follow the cash. When a retailer consistently sends more money to buybacks than to the unglamorous work of upgrading technology, supply chain, and stores, it’s choosing short-term stock optics over long-term survival.

Bed Bath & Beyond failed all three tests long before the end. The collapse didn’t come out of nowhere—the data was telling the story the whole time.

XIV. Further Reading & Resources

If you want to go deeper, here are a few of the most useful primary sources and solid lenses for understanding what happened:

- SEC 10-K filings from 2010–2022, which show the deterioration quarter by quarter—strategy shifts, cash burn, and the compounding effects of buybacks and missed investment

- Ryan Cohen’s Schedule 13D filings, which lay out the activist thesis, the proposed moves, and how quickly the narrative changed

- Bankruptcy court documents, which capture the last stretch in unfiltered detail: liquidity crises, vendor pressure, and the choices made when there was no time left

- Contemporary coverage from RetailWire and Chain Store Age, which follows the story in real time from inside the industry

- The Retail Revival by Doug Stephens and The New Rules of Retail by Robin Lewis, which give you frameworks to understand why some retailers adapt—and why others can’t

Bed Bath & Beyond is required reading if you want to understand how retail icons fail in public, over years, and in slow motion—and what it actually takes to survive when shopping behavior and distribution shift under your feet.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music