Banc of California: From Regional Bank to Fortress-Backed Rebuild

I. Cold Open & Episode Roadmap

Picture this: March 2023. The U.S. banking system is lurching into its sharpest panic since 2008. Silicon Valley Bank collapses in the span of two days. Signature follows. First Republic is bleeding deposits. Across California, customers are moving money with a few taps on a phone, and mid-sized bank stocks are getting crushed.

In downtown Los Angeles, inside Banc of California’s headquarters, executives are watching the same red screens as everyone else—while taking calls from clients asking the only question that matters in a bank run: Is my money safe?

Now for the twist. Eighteen months earlier, Banc of California wasn’t anyone’s idea of a safe harbor. It was a walking case study in what happens when governance breaks: insider dealings, conflicts, activists circling, reputations shredded. A bank that had imploded under the weight of its own ambition.

And yet here it was, in the middle of a once-a-generation regional bank crisis, not backing away from risk—but stepping into it. Banc of California was gearing up to buy a bank more than twice its size.

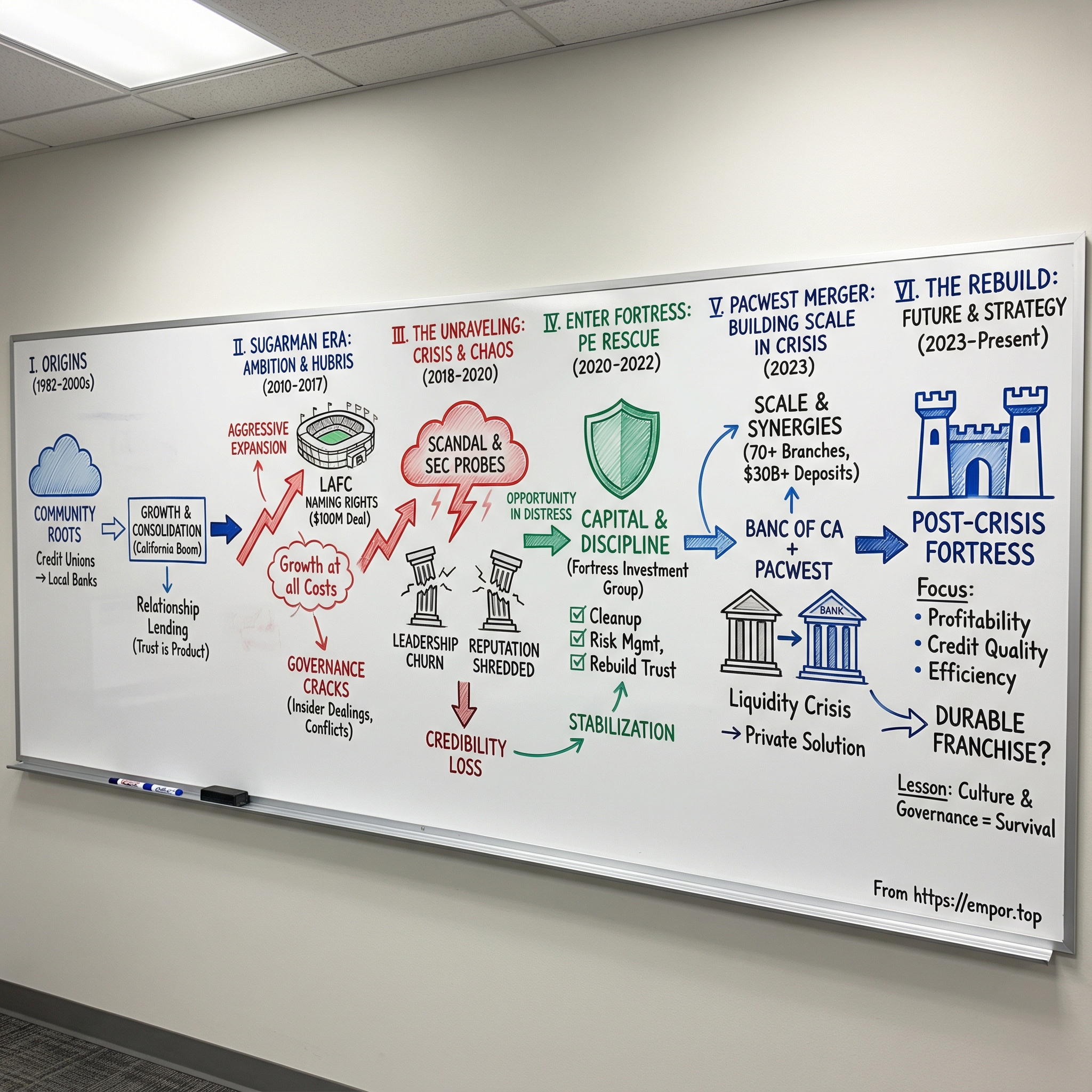

This is the story of a California community bank that rose with big dreams, fell into scandal, got rescued by a private equity heavyweight, and is now attempting a rebuild into something sturdier: a post-crisis fortress.

It matters because it sits right at the intersection of three forces reshaping American finance: the relentless consolidation of regional banks, the expanding footprint of private equity in regulated industries, and the existential squeeze on every bank that isn’t either enormous or truly specialized.

Along the way, we’ll see how governance failures can destroy value faster than any credit cycle ever could. We’ll follow the activist fight that finally forced change. We’ll watch Fortress Investment Group—one of Wall Street’s most aggressive distressed investors—move in when the bank needed credibility and capital. And we’ll ask the question at the center of this whole saga: can a turnaround playbook designed for distressed assets actually work in a business where trust is the product?

By the end, the takeaway won’t be about one merger or one scandal. It’ll be about a truth that’s easy to ignore until it’s too late: in banking, culture, controls, and governance aren’t paperwork. They’re survival.

So let’s start where every origin story should—at the beginning.

II. The Origins: Community Banking in California (1982–2000s)

The year was 1982, and Southern California was booming. Ronald Reagan had just entered the White House, and the Golden State was in one of its periodic growth explosions. Population was surging. Real estate was climbing. New businesses were popping up everywhere. In Orange County, a group of local businessmen saw a familiar opening: if California was going to keep growing this fast, it was going to need more local banks willing to lend into that growth.

But the roots of what would eventually become Banc of California actually stretch back much further—back to 1941, when the institution began life as the Rohr Employees Federal Credit Union. It existed for a simple purpose: serve the workers of the Rohr Aircraft plant in Chula Vista. A wartime credit union isn’t a flashy origin story, but it’s an honest one. It was built to help defense workers save, borrow, and get through uncertain times. Trust, not scale, was the product.

By the early 1980s, that same organization was taking shape in its modern banking form—right as California banking was entering one of the most chaotic eras in American financial history. To understand why the timing matters, you have to zoom out to what was happening across the industry.

The Savings and Loan crisis—spanning from the late 1970s through the late 1980s—was a slow-motion disaster triggered by deregulation, competition, and a shift into riskier assets like commercial real estate. Institutions that had once been plain-vanilla lenders suddenly had permission, and pressure, to reach for yield.

And California was ground zero for both the upside and the wreckage. From 1985 onward, a huge share of thrift failures came from just three states: California, Texas, and Florida. California’s regulatory environment became especially permissive. In December 1982, the state passed the Nolan Bill, allowing California-chartered S&Ls to invest all of their deposits in essentially any type of venture—a move intended to keep them from fleeing to the federal system, but one that also opened the door to far more risk.

The collapse that followed was staggering. More than a thousand savings and loan associations failed in the 1980s and 1990s, making it one of the most devastating banking breakdowns since the Great Depression.

But in every wreckage, there’s a different kind of opportunity—especially for institutions with patient capital and conservative underwriting. While thrifts were blowing up around them, the disciplined community banks that made it through came out with something valuable: proof that a relationship-based model could survive in California’s complex, fast-moving economy.

Over the next two decades, the institution kept evolving—step by step, name by name. It became Pacific Trust Federal Credit Union in 1995. In 2000, it was renamed Pacific Trust Bank, converting into a mutually owned federal savings bank. Two years later, it became a subsidiary of First PacTrust Bancorp Inc.

That arc—from an employee credit union to a federal savings bank to a holding-company structure—mirrored the broader reshaping of American banking after the S&L crisis. Survivors didn’t just grow by opening branches. They grew by consolidating, acquiring, and building durable local franchises.

The modern Banc of California identity arrived later. In 2012, First PacTrust Bancorp, Inc. and Beach Business Bank completed their merger. In 2013, the company’s two banking subsidiaries—Pacific Trust Bank and The Private Bank of California—were merged to form Banc of California.

Underneath all the corporate restructuring was a timeless community-bank value proposition: relationship lending grounded in local knowledge, aimed at customers the national giants often overlooked. Small businesses that needed a banker who could actually understand their cash cycles. Real estate developers who needed someone who knew the local market block by block. Entrepreneurs in underbanked communities who needed access to credit, not a generic scorecard.

This model had real advantages. Local bankers could judge risk in ways an algorithm often couldn’t. They could be flexible when they trusted the borrower and understood the business. And those relationships created real stickiness—once a bank becomes embedded in your operations, switching is painful.

But the same community model came with baked-in limits. Scale is constrained by geography. Big tech investments are harder to justify. Regulatory costs don’t shrink just because you’re smaller. And relationship banking has a darker edge, too: when the distance between banker, borrower, and board member gets too small, conflicts of interest become easier to hide—and harder to unwind.

As the bank moved into the 2010s with ambitions to become a statewide player, those tensions stopped being theoretical. The question wasn’t whether the franchise could grow. It was whether it could scale without breaking the very trust that made it valuable in the first place.

III. The Steven Sugarman Era: Ambition Meets Hubris (2010–2018)

Enter Steven Sugarman: a Yale Law School graduate who’d done stints at McKinsey & Company and Lehman Brothers before launching his own investment vehicles. On paper, he was the kind of leader you’d pick if your goal was to take a small, locally rooted institution and turn it into something much bigger. He even co-authored a book called "The Forewarned Investor: Don't Get Fooled Again by Corporate Fraud." The irony wouldn’t land until later.

Sugarman saw what many outsiders miss about California banking: it’s massive, fragmented, and full of niches. If you could stitch together the right pieces—branches, deposits, talent, and a brand—you could build a true statewide business bank.

He became deeply involved in the combination that ultimately formed today’s Banc of California. He served as a director of First PacTrust Bancorp, the holding company of Pacific Trust Bank, in 2010. He was instrumental in the merger of Pacific Trust Bank and The Private Bank of California, which merged to form Banc of California in 2013. After that merger, he led the combined bank until 2017, serving as Board Chair, CEO, and President.

And for a while, the story looked like a win. Under Sugarman, Banc of California earned high-profile recognition: it landed on lists like Forbes Magazine's Top Banks in America and Fortune Magazine's Fastest Growing Companies, and it became the largest independent bank in California to receive an "Outstanding" Community Development rating from the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency.

But the engine behind all that praise was an aggressive growth playbook. Sugarman put it plainly: "We're one of the few community banks that can offer to finance someone's business and their home." The bank expanded quickly, including a major deal with Popular Inc.—the parent of Banco Popular in Puerto Rico—that added 20 retail branches across Los Angeles and Orange counties, plus $1.1 billion in deposits and $1.1 billion in performing loans and other assets.

In 2014, Banc of California bought those 20 Southern California branches from Popular, Inc. for $5.4 million. Overnight, it doubled its branch footprint and pushed assets to $5 billion. This wasn’t slow-and-steady community banking. This was scale, fast.

The hiring signaled the same ambition—and a taste for big-name credibility. Former Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa joined the bank as a strategic advisor. The role was part-time, advising Sugarman and the board, and it also left Villaraigosa room to keep his public profile—speaking engagements, affiliations, even the possibility of a run for governor.

On the outside, the bank also projected a strong community mission. Sugarman championed a financial literacy initiative built in collaboration with nonprofit, community, and faith-based organizations across Southern California. In 2014, alongside President Bill Clinton and Villaraigosa, Sugarman helped set two Guinness World Records for the world's largest financial literacy event.

Then came the move that put Banc of California’s name—literally—on the skyline.

In 2016, Los Angeles FC signed a 15-year, $100 million naming rights deal with Banc of California for the stadium. For a community bank, it was a statement: a long-term commitment worth roughly $6.7 million a year for fifteen years, to put its name on a Major League Soccer venue.

At the groundbreaking, LAFC announced the naming rights deal as demolition began on the Los Angeles Memorial Sports Arena site, next to the Coliseum—about as high-visibility a location as you can buy in Southern California. When Banc of California Stadium opened in April 2018, it became the first open-air sports venue built in Los Angeles since 1962. LAFC’s fanbase showed up loud from the start, and the club quickly looked like an MLS powerhouse.

If you were a certain kind of CEO, the stadium deal was perfect. It signaled arrival. It associated the brand with a rising franchise and a glamorous ownership circle. It opened doors to celebrity owners and high-net-worth customers. And the bank wasn’t just slapping its name on the building—it was also involved in financing it, securing a significant part of the $180 million loan while signing the $100-million, 15-year naming rights agreement.

But to skeptics, it landed differently. What did naming rights have to do with relationship banking? Was this really the best use of shareholder capital? And why was a bank this size making a bet that felt designed for institutions ten times larger?

Around the same time, the questions got sharper—and darker. Governance concerns surfaced. The board’s relationships looked increasingly complicated. Short sellers began digging in, asking uncomfortable questions about insider lending, related-party transactions, and whether everything at California’s fastest-growing community bank was as clean as the marketing suggested.

In early 2017, those doubts spilled into public view. Banc announced on March 1, 2017 that it had received a "notice of formal investigation" from the SEC on January 17, 2017. A special committee reviewed the allegations and reported mixed findings. It "did not find evidence that the individual named in the blog posts had any direct or indirect control or undue influence over the Company." It also said it found no violations of law or evidence that any loan or related-party transaction impaired director independence.

But then came the line that mattered: the Special Committee found that certain public statements the company made in October 2016 about its earlier inquiry "were not fully accurate."

In banking, that kind of phrasing is radioactive. And the damage was immediate. Sugarman resigned as chairman and CEO on January 23, 2017.

His exit ended the era of aggressive expansion and kicked off a prolonged credibility crisis. Even the stadium—meant to symbolize Banc of California’s graduation to the big leagues—eventually turned into a very expensive reminder of what happens when image gets ahead of fundamentals. On May 26, 2020, Banc of California announced it planned to end the naming rights deal, paying $20 million to terminate early while remaining the club's banking sponsor.

LAFC later moved to a new naming rights deal with BMO, due to span the next 10 years. Banc of California walked away from a 15-year agreement after only a few seasons—having paid the termination fee and sponsored the club for three years. In total, the bank spent roughly $56 million on a deal that was supposed to run for fifteen years, but ended after only a fraction of that time.

The Sugarman era is a case study in what happens when ambition outruns controls. The growth was real. The brand-building was loud and visible. But governance was weak, related-party transactions looked murky, and oversight wasn’t strong enough for the pace of expansion.

Those aren’t the flaws that always kill a bank in good times. They’re the flaws that make survival almost impossible when the environment turns—and when trust, once cracked, becomes the hardest asset to rebuild.

IV. The Unraveling: Governance Crisis & Leadership Chaos (2018–2020)

The unraveling of Banc of California played out like a financial thriller—except the damage was real, and it lasted for years. What started as an anonymous online attack escalated into a credibility crisis that toppled leadership, drew regulators in, and sent shareholders into free fall.

In October 2016, an individual using the pseudonym “Aurelius” published a post on Seeking Alpha alleging that Banc of California’s directors had ties to an imprisoned con man. The story jumped from the internet to mainstream media fast, and once it did, the market reacted with brutal speed. The next day, Banc of California’s stock dropped 29%, its worst one-day move since 2002.

The allegations centered on Jason Galanis, a California financier who had pleaded guilty to securities fraud charges. And the “Aurelius” posts didn’t land on a clean slate. Banc was already dealing with activist pressure and lawsuits, and governance concerns from major shareholders, including the California State Teachers Retirement System. There were also conflict-of-interest allegations involving the bank and Steven Sugarman’s brother, Jason.

Then came the part that turned an ugly headline into a lasting wound: the bank’s response.

Banc issued a press release describing an “independent” investigation into the allegations. But later reviews concluded the effort wasn’t truly board-led. It appeared to have been directed by management, not independent directors, and the law firm involved had previously represented both the company and Sugarman personally. The release also suggested that the board, or “Disinterested Directors,” had been receiving regular updates, including about regulatory communications—language that overstated both the level of regulator engagement and the depth of board oversight.

That wasn’t just a PR misstep. In banking, misleading disclosures aren’t a slap-on-the-wrist problem. They’re a regulator problem.

On January 12, 2017, the SEC issued a formal order. That same day, it served a subpoena seeking documents largely related to the October 2016 press release and associated public statements. Less than two weeks later, on January 23, 2017, Steven Sugarman resigned as CEO and chairman—the same day the bank publicly disclosed it was under SEC investigation. Banc offered no explanation for the resignation, but the timing made it hard for anyone to see it as a coincidence.

The mess kept expanding. Whistleblower lawsuits followed, painting a picture not just of governance confusion, but of a culture that had lost control of itself. One complaint alleged inflated profits and described a senior executive using company funds to pay for strippers. It also alleged that a decision to reverse accrued employee bonuses resulted in revenues being carried over in a way that made the company look more profitable. The plaintiff said she was terminated after raising concerns about both the bonus issue and the then-CFO’s behavior.

Another whistleblower suit came from Carlos Salas, a former vice president who alleged he, Sugarman, and others were ousted by a special board committee because they had raised concerns about the conduct of certain directors and officers—including alleged breaches of fiduciary duty and self-dealing.

Inside the bank, leadership became a revolving door. Banc named Doug Bowers as CEO—an outsider with a tech banking background who previously led Square 1, the venture-focused lender acquired in 2015. His job was simple to describe and almost impossible to execute: stabilize the institution, restore trust with regulators and investors, and prove Banc could operate like a serious bank again.

On paper, the board moved quickly. It separated the Compensation, Nominating and Corporate Governance Committee into two committees—one focused on compensation, the other on governance. It began preparing a stricter related-party transaction policy. And it split the roles of board chair and CEO.

But reforms on paper can’t instantly repair a reputation, especially when new problems keep surfacing. In June 2018, Banc of California was named as one of the KPMG audit clients caught up in the KPMG/PCAOB regulatory data theft scandal, where former KPMG executives were accused of stealing confidential PCAOB inspection information to improve audit results.

The CEO churn continued, too. Bowers departed in 2019. Jared Wolff became CEO in March 2019, succeeding Bowers, who had taken the job in 2017 after Sugarman’s exit.

Meanwhile, Sugarman’s departure didn’t end the public fight. A month after the SEC filed a fraud suit against his older brother, Sugarman filed a $65 million racketeering, fraud, and defamation lawsuit against what he described as the “Aurelius Enterprise,” which he said included short sellers like Carson Block and Muddy Waters, among others.

Sugarman was not charged in the SEC case involving his brother, and he has not otherwise been accused of wrongdoing in the years before or since. His spokesman said he “committed no wrongdoing at Banc of California, no court has ever found any wrongdoing, and no regulatory agency has ever alleged any wrongdoing against Mr. Sugarman,” and added that he received an official written no-action letter from the SEC.

But by then, the bigger story had already taken hold. The lesson from Banc of California’s governance crisis is brutally simple: governance failures can destroy value faster than bad loans.

The bank’s underlying business wasn’t collapsing under credit losses. The loan book wasn’t the headline. Trust was. And once the market decided it couldn’t trust what Banc said about itself—who was really in charge, what the board really knew, how “independent” anything really was—the damage spread everywhere a bank is vulnerable. Depositors get nervous. Regulators lean in. Talent starts taking recruiter calls. The franchise doesn’t die all at once; it starts bleeding credibility until it can’t compete.

And that’s the state Banc of California carried into the next phase of its life: a bank that still had a business, but had lost the one asset no bank can function without—belief.

V. Enter Fortress: The Private Equity Rescue (2020–2022)

By early 2020, Banc of California was wounded but not dead. The governance crisis had been contained—at least on paper. Leadership had turned over. The loudest scandals were in the rearview mirror. But the bank was still small, still carrying a bruised reputation, and still operating without the kind of balance-sheet strength that buys you time when markets get ugly.

Then COVID-19 hit.

For a bank already fighting for credibility, the pandemic could have been the final blow. Instead, it became the forcing function. Volatility has a way of clarifying who can fund themselves, who can’t, and who needs a stronger backer. Banc needed more than a fresh coat of paint. It needed capital, confidence, and a new center of gravity.

That’s where private equity comes in—specifically, Fortress Investment Group.

The basic turnaround thesis is simple, and it’s as old as distressed investing: buy cheap relative to the bank’s underlying value, recapitalize it, impose discipline, clean up operations, and wait for trust—and the valuation—to come back. Fortress specializes in exactly these situations.

Fortress Investment Group, LLC is a New York-based multi-manager investment firm that invests across corporate credit, real estate, private equity, insurance, and permanent capital strategies. It manages $53 billion of assets for more than 2,000 institutional clients and private investors worldwide. The firm was founded in 1998 by Wesley Edens, a former BlackRock partner, alongside other Wall Street veterans. Fortress expanded quickly into hedge funds, real estate-related investments, and debt securities, and its private equity funds produced strong results in the early years, including net returns of 39.7% between 1999 and 2006.

So why would a firm like that want a troubled California bank?

A few things lined up.

First, the bank’s issues weren’t primarily about a loan book imploding. The rot had been governance, culture, and control failures—serious problems, but ones that can be fixed with the right oversight and incentives.

Second, California banking is still a prize. The state’s economy is the largest in the country and among the largest in the world. A well-run business bank with the right footprint in California is valuable, even if it needs rebuilding.

Third, the stock was trading at a steep discount to tangible book value. For a value-oriented buyer, that discount creates room for mistakes—and upside if the turnaround sticks.

Fourth—and this mattered most—the bank had already started the cleanup. Management under Jared Wolff was in place, focused on rebuilding, and the worst of the regulatory issues were no longer compounding day after day. In other words: the platform wasn’t pristine, but it was investable.

With Fortress aligned with management, the early priorities were exactly what you’d expect: reinforce capital, tighten risk management, and rebuild relationships with regulators and the market. Then came a concrete step toward scale. In March 2021, Banc of California announced it would acquire Pacific Mercantile Bank in a transaction valued at $235 million. The message was that this time, consolidation would be deliberate—building size with a compatible California franchise, not swinging for headlines.

Still, the skepticism was fair. Private equity and banking are an uneasy mix. PE likes speed, clean narratives, and high returns on a defined timeline. Banking runs on patience, compounding, and credibility with regulators and depositors—credibility that takes years to earn and minutes to lose.

But the best distressed investors know a bank turnaround isn’t a flip. It’s a long rebuild. And what Fortress and its co-investors brought wasn’t just money. It was governance muscle built across decades of messy situations, an operating playbook for stabilizing institutions, and a signal to the outside world—especially regulators—that this bank was now under heavier supervision than it had ever been.

Banc of California wasn’t out of the woods. But it finally had something it hadn’t had in years: a sponsor with the capital and control to force a real reset.

And that mattered, because the next crisis was already on the horizon. Within two years, the 2023 regional banking panic would hit—and Banc would be in position to do something that would’ve sounded absurd just five years earlier.

VI. The PacWest Merger: Building Scale in Crisis (2023)

March 2023 kicked off the most acute banking panic since 2008. Silicon Valley Bank and Signature failed within days of each other. To stop the run from spreading, the U.S. government stepped in and promised that even uninsured depositors would be made whole. Seven weeks later, First Republic became the next domino, and again the government moved to contain the contagion.

PacWest Bancorp ended up in the blast radius. Like SVB, it had been squeezed by the rapid rise in interest rates through 2022 and into early 2023. In the fourth quarter of 2022, PacWest sold $1 billion of available-for-sale securities at a $49 million loss. Then the crisis of confidence hit full force: the Monday after SVB failed, PacWest’s stock fell 21%, and trading was halted amid volatility.

What happened next was the classic modern bank-run story—fast, digital, and brutal. PacWest saw a swift deposit run, losing $1.7 billion in just two days after the spring’s regional banking shock. By the time it reported earnings on October 24, the picture was deteriorating: pressure from a weakening property market and rising credit risk, made worse by higher mortgage rates.

The market had already passed its verdict. From February 2022 through May 2023, PacWest’s stock plunged from above $50 to as low as $2.48 per share. It rebounded somewhat in May and June as it became clear PacWest wasn’t the next SVB—but the franchise had been damaged, and the clock was ticking.

Into that chaos stepped Banc of California with a deal that sounded upside down: the smaller bank would buy the larger one. PacWest had about $44 billion in total assets as of March 31, versus Banc of California’s roughly $10 billion. Yet their market values were suddenly in the same neighborhood—about $924 million for PacWest and $842 million for Banc.

The transaction came with another crucial ingredient: new outside capital. The deal included a $400 million investment from Warburg Pincus and Centerbridge Partners, giving them about 20% of the combined company and warrants to buy additional shares.

The mechanics reflected just how carefully engineered this needed to be. After closing, PacWest shareholders would own about 47% of the combined company. The new investors would hold about 19%. Existing Banc of California shareholders would own about 34%. It was a 100% stock-for-stock merger with a fixed 0.6569 exchange ratio, set at the time the indication of interest was signed. And the $400 million capital raise was committed at a fixed $12.30 per share of BANC stock, funding concurrently with the merger’s close—an important stabilizer in a market where certainty had become the rarest commodity.

Regulators helped make that certainty possible. The Federal Reserve, working behind the scenes, accelerated the approval process as it pushed for a private-sector solution while PacWest was teetering. As a Warburg Pincus spokesperson put it: “As longstanding bank investors, we appreciate the ability of regulators to move fast in a crisis. When appropriate, creating regulatory certainty makes it considerably easier to inject private capital into banks when they need it most and can avoid the need for a bailout.”

The key detail was that PacWest, for all its liquidity stress, wasn’t viewed as hopelessly insolvent. It had positive tangible common equity as a percentage of tangible assets—adjusted for unrecognized bond and loan losses—before the acquisition. That metric stood at 3.98% on March 31, 2023. One analyst summarized the opportunity: it was a liquidity crisis, not a capital wipeout, and that made a private solution viable—especially with supportive regulators.

The deal closed December 1, 2023. Banc of California completed its all-stock merger with PacWest, and Pacific Western Bank merged into Banc of California. The combined organization kept the Banc of California name and brand, operating more than 70 branches across the state.

But scale didn’t come for free. The combined bank moved quickly to reposition the balance sheet. In connection with the merger, Banc of California and PacWest sold about $1.9 billion in assets. By November 30, PacWest had sold around $1.5 billion of its securities portfolio, including agency commercial mortgage-backed securities and collateralized mortgage obligations. Banc of California sold nearly $450 million of its own assets.

Even with that, absorbing PacWest’s issues was expensive. Banc of California bought PacWest for a headline price of about $1 billion, but the cleanup came with real costs. After the merger, the bank sold roughly $6 billion of lower-yielding loans and securities, taking a $442.4 million loss on the securities sales. It also paid $32.7 million to the FDIC as part of the special assessment tied to the year’s banking turmoil.

Shareholders still backed it overwhelmingly. More than 98% approved the merger when both companies voted on November 22, 2023. “Today begins a new chapter for Banc of California,” CEO and President Jared Wolff said. “California has experienced a void of business banks that we intend to fill, and we look forward to helping our clients grow and delivering for our clients, communities and shareholders.”

The strategic logic was straightforward: scale, deposit diversification, cost synergies, and—most of all—survival. Post-close, the combined bank had about $25.3 billion in loans and $30.5 billion in deposits. It planned to pay down about $13 billion of wholesale borrowings by selling assets, reducing dependence on expensive, non-core funding.

This was the inflection point. A bank that had nearly been destroyed by governance failures just six years earlier was now taking over a competitor far larger than its pre-crisis self—and doing it with heavyweight capital partners and regulators eager for a private-sector fix.

VII. The Rebuild: Strategy, Culture & Competitive Positioning (2023–Present)

The post-merger integration was the moment of truth. All the strategic rationale in the world meant nothing if Banc of California couldn’t take two institutions—with different systems, different cultures, and different scars from 2023—and turn them into a single bank that felt coherent to customers and controllable to regulators.

“Since closing our transformational merger with PacWest Bancorp on November 30, 2023, we have made excellent progress on the integration and the balance sheet repositioning actions,” CEO Jared Wolff said. “As a result, we have created the well capitalized, highly-liquid financial institution we envisioned, with significant earnings potential and a strong position in key California markets.”

The first order of business was the messy, expensive work of cleaning up the balance sheet. The bank moved aggressively. In the fourth quarter, it sold $2.7 billion of legacy PacWest available-for-sale securities, taking $442.4 million in losses. That quarter also included pre-tax merger costs of $111.8 million, a $32.7 million FDIC special assessment, and an initial credit provision on acquired loans of $22.2 million.

The headline was brutal: a net loss of $492.9 million, or $4.55 per diluted common share, for the fourth quarter of 2023. But strategically, this was the price of ripping off the bandage—resetting the earnings base and getting the combined bank out from under low-yield assets and crisis-era baggage.

Then came the other make-or-break step: getting everyone onto one operating platform. The core systems conversion was completed on July 21, 2024. That’s the kind of milestone most customers never see—but inside a bank, it’s the difference between “two banks wearing one logo” and one institution that can actually run, report, and serve clients as a unified whole.

Once systems were aligned, the cost side followed. Occupancy expense fell as the bank consolidated branches, closing redundant locations that sat too close to each other after the merger. Headcount came down and operations were streamlined—classic post-merger muscle, but essential if the combined franchise was going to earn its keep.

“During the third quarter, we made significant progress growing our core earnings and we achieved our year-end targets for net interest margin, noninterest expenses, and balance sheet metrics a quarter early,” Wolff said. He pointed to additional balance sheet moves, including the sale of $1.95 billion of Civic loans, which he said improved capital and liquidity.

By September 30, 2024, the bank was emphasizing capital strength well above “well-capitalized” thresholds, including estimated ratios of 16.98% total risk-based capital, 12.87% Tier 1 capital, 10.45% CET1, and a 9.83% Tier 1 leverage ratio. Book value per share rose to $17.75, and tangible book value per share to $15.63.

Profitability, too, started to look less like a post-merger recovery story and more like a bank regaining its footing. Net interest margin improved to 3.13% for the nine months ended September 30, 2025, up from 2.79% in the comparable 2024 period—driven largely by a 53 basis point decline in the average total cost of funds to 2.40%.

That funding story was the whole point. PacWest had leaned on expensive wholesale funding in the panic. Banc’s rebuild required unwinding it. Deposit costs also moved in the right direction: the average cost of deposits declined by 49 basis points to 2.11%, reflecting federal funds rate cuts in the second half of 2024.

With the balance sheet cleaned up and the plumbing modernized, management began shifting the narrative from repair to offense. Banc of California, Inc. describes itself as a relationship-based business bank, providing banking and treasury management services to small-, middle-market, and venture-backed businesses. It is also the largest independent bank headquartered in Los Angeles and the third largest bank headquartered in California.

Wolff framed the pivot plainly: “With these major balance sheet and operational initiatives behind us, Banc of California is now at an inflection point, shifting our focus from transforming our internal infrastructure to external growth. We are capitalizing on the strength of the franchise and balance sheet we have built and the exceptional customer experience we can offer to expand existing relationships and add attractive new client relationships.”

By the third quarter of 2025, the bank pointed to continued momentum: book value per share of $19.09, total revenue growth of 9%, earnings per share of $0.38, and tangible book value per share of $16.99. It also reported 17% annualized growth in noninterest-bearing deposits—an important signal, because in banking, cheap and sticky funding is strategy.

And Banc kept leaning into the “community bank, scaled up” identity it had always marketed—especially when California needed it. During the January 2025 Southern California wildfires, the bank created the Wildfire Relief & Recovery Fund a week after the fires began, seeding it with a $1 million donation to support recovery and rebuilding.

This is what the rebuild looks like in real life: integration synergies realized, systems finally unified, expensive funding unwound, and a balance sheet repositioned for a more normal earnings profile. But the hard part—the part that determines whether this becomes a durable franchise—still lies ahead: growing profitably, maintaining credit discipline, and competing in California without repeating the mistakes that nearly ended the story the first time.

VIII. The California Banking Ecosystem & Competitive Landscape

California’s banking market is its own planet. If it were a country, its economy would rank among the largest in the world—bigger than India, the United Kingdom, or France. More than $3.5 trillion of economic output flows through the state each year, powered by a mix that’s unusually diverse: technology, entertainment, agriculture, real estate, international trade, and professional services.

For a bank, that diversity is the prize. It’s also the problem. Because where the money is, the competition is.

At the top of the food chain are the national giants—JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, and Wells Fargo—who dominate share, brand, and distribution. Then come the super-regionals like U.S. Bank, big enough to spend heavily and aggressive enough to take share. Layered in are California-grown regionals that have historically built real franchises by specializing—Western Alliance, and previously First Republic before its collapse—proving there’s room in this market for banks that know exactly who they’re serving.

This is the arena Banc of California is trying to win in. It’s the third largest bank headquartered in California and offers a broad range of loan and deposit products and services through 80 full-service branches located throughout California and in Denver, Colorado, and Durham, North Carolina, as well as through regional offices nationwide.

So why do regional banks still matter when a customer can open an account with a megabank or a digital-first fintech in minutes?

Because business banking isn’t just a product menu—it’s a relationship. The value isn’t “a checking account.” It’s a banker who understands the local market, knows the customer’s cash flows, and can make credit decisions with context that doesn’t fit neatly into a standardized model.

That’s especially true in the middle market—companies with revenues between $10 million and $1 billion. These businesses are often too complex for small community banks to serve at scale, but not large enough to get white-glove attention from the biggest institutions. This is Banc of California’s target zone: relationship-driven commercial banking for companies that need a real partner, not a call center.

Fintech changes the battlefield, but it doesn’t replace it. Digital banks are great at simple, standardized products—checking, savings, basic payments. But once you get into the machinery that actually runs a business—treasury management, trade finance, credit facilities, interest rate swaps, foreign exchange—you’re in a world where expertise, trust, and ongoing service matter. Those are harder to scale with an app alone.

Then there’s the invisible force shaping everything: regulation. California banks live under multi-layered oversight—the Federal Reserve, the OCC or state regulators depending on charter type, the FDIC for deposit insurance, and the California Department of Financial Protection and Innovation. Compliance is non-negotiable, and the costs hit smaller institutions harder, which quietly tilts the economics toward scale.

That’s a big reason U.S. banking has consolidated for decades. In 1984, there were over 14,000 commercial banks. Today, there are fewer than 4,500, and the number keeps shrinking. For mid-sized banks, the choices narrow over time: get bigger so compliance and technology costs don’t crush you, specialize so deeply you can defend your margins, or sell.

The 2023 regional banking crisis poured gasoline on that trend, especially in California. Silicon Valley Bank failed. First Republic failed. PacWest—after a crisis that damaged confidence—ended up being acquired. Competitors didn’t just disappear; many of the survivors pulled back, tightening credit and rethinking risk.

Management believes that reshuffling has opened a window: opportunities to add attractive client relationships that bring both operating deposit accounts and high quality loans, particularly after the significant changes in the California banking landscape over the past two years as competitors exited or significantly retreated.

That’s the bet behind Banc of California’s rebuild. Be big enough to matter in the most competitive banking market in the country, but still small enough to feel personal. The open question is whether that middle ground is a stable destination—or just a temporary stop before the next wave of consolidation forces the story into another act.

IX. Business Model Deep Dive & Unit Economics

To understand whether Banc of California’s rebuild is real, you have to understand how a bank actually earns its keep.

At the core, banking is a spread business. A bank gathers money—mostly deposits—then puts that money to work in loans and securities. If it earns more on those assets than it pays on its funding, it generates net interest income. Layer on fees from things like treasury management and wealth management, and you get a second stream of revenue that can help smooth out whatever interest rates are doing.

The trick is that this “simple” model gets judged through a handful of metrics that tell you whether the machine is healthy—or just temporarily flattered by a good quarter.

Net Interest Margin (NIM) is the headline number: the spread between what the bank earns on its assets and what it pays on its liabilities. Banc of California’s net interest margin was 3.13% for the nine months ended September 30, 2025, up from 2.79% for the same period in 2024. That improvement is exactly what you’d expect if the post-merger cleanup is working: sell or run off lower-yielding assets, reduce expensive wholesale funding, and let the core franchise do more of the work.

Cost of Deposits is where that story either holds up or falls apart. Deposits are the raw material for the spread engine, and the price you pay for them is a direct hit to profitability. The average cost of deposits declined by 49 basis points to 2.11%, reflecting federal funds rate cuts in the second half of 2024. In plain English: funding got cheaper, and cheaper funding widens the spread.

Noninterest-bearing Deposits are the best kind of deposits—because they’re essentially free. They tend to come from operating accounts tied to real customer relationships, not rate shoppers. Average noninterest-bearing deposits represented 28.2% of average total deposits for the nine months ended September 30, 2025, up from 27.0% in the comparable 2024 period. It’s not just a mix statistic; it’s a signal of relationship depth and long-term funding quality.

Efficiency Ratio captures whether the bank can translate revenue into profit without the cost structure eating it alive. Lower is better. Banc’s noninterest expense decreased by $55.2 million to $555.2 million for the nine months ended September 30, 2025, driven mainly by declines in insurance and assessments, customer-related expenses, and occupancy expense. This is what post-merger synergies are supposed to look like: fewer duplicative costs and a tighter operating footprint.

Credit Quality is the reality check, because it determines how much of that interest income is actually real. The provision for credit losses was $58.1 million for the nine months ended September 30, 2025, compared to $30.0 million for the same period in 2024. The provision for 2025 primarily included a provision for loan losses of $57.0 million. Higher provisions can reflect multiple things at once—portfolio changes, loan sales, and a shifting economic backdrop—but either way, this is the line item that can erase a lot of operational progress if credit turns.

Put together, the roadmap from “rescued” to “normalized” is straightforward: keep improving NIM through balance sheet optimization, keep building the base of noninterest-bearing deposits, keep taking costs out of the combined platform, and keep credit losses from overwhelming the gains—especially as California commercial real estate works through stress.

What should investors watch? Three KPIs matter most:

-

Net Interest Margin trajectory – The clearest read on whether the restructuring is translating into better earnings power, and how deposit pricing is evolving.

-

Noninterest-bearing deposit mix – A proxy for relationship strength and funding quality. More of it usually means stickier customers and a better margin structure.

-

Credit costs (provision expense and charge-offs) – The pressure gauge for downside risk, and likely where any California CRE deterioration shows up first.

X. Porter's 5 Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: Moderate-High

For most of modern banking history, the moat was obvious: you needed regulatory approval, a lot of capital, a branch network, and—most importantly—enough credibility to convince people to park their money with you. Those barriers still exist, but they’re not what they used to be.

Fintech has found ways around the traditional gatekeepers. Instead of building a bank from scratch, many companies effectively rent the regulated parts—partnering with chartered banks or pursuing narrower licenses. Square, PayPal, and Stripe have all built meaningful lending businesses without being traditional banks. Neobanks like Chime have pulled in millions of customers by delivering a cleaner, faster digital experience.

Capital, too, is less of a limiter than it once was. Private equity and tech funding can show up quickly behind a credible team and a compelling wedge. The hardest thing to buy is still the same thing Banc of California lost—and is now rebuilding: trust. For business customers, especially, trust is the real barrier to entry, because operating deposits don’t move to a new institution on vibes. They move when decision-makers believe the bank will be there tomorrow.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Low-Moderate

In banking, the core “suppliers” are depositors—the source of the funding a bank turns into loans. And in the post-2023 world, depositors have gotten more demanding. Deposit beta—how much of each Fed move banks have to pass through to customers—has been elevated, and competition for deposits intensified during the crisis and hasn’t fully cooled.

Then there’s talent. A relationship bank is only as good as its relationship managers, and experienced commercial bankers are expensive. In California, where the client base is dense and competitors are everywhere, the fight for strong bankers is constant.

Finally, core technology providers matter more than most outsiders realize. Vendors like Fiserv and Jack Henry have real leverage because switching a core system is painful, risky, and time-consuming—exactly the kind of project banks try to avoid unless they absolutely have to.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: Moderate-High

Banc of California’s target customers—small and middle-market businesses—often have real negotiating power. Larger depositors are sophisticated, rate-aware, and willing to move money when they see a better deal. Borrowers can shop terms across banks and non-banks, and they do.

But business banking has one advantage consumer banking doesn’t: inertia that’s actually earned. Once a company is set up with treasury management, operating accounts, payment rails, and credit facilities, switching becomes a real project. That friction creates stickiness, and stickiness is why relationship banking can still work—even when price competition is relentless.

Threat of Substitutes: High

The substitution threat isn’t theoretical—it’s happening. Bigger companies increasingly bypass banks by raising money directly in the capital markets. Private credit has expanded rapidly and competes head-to-head with banks for middle-market lending. Money market funds give customers a deposit-like place to park cash at competitive yields.

Payments are shifting, too. Digital tools reduce reliance on traditional bank rails, and embedded finance is pushing banking products into non-bank apps. The direction is clear: more substitutes, more disintermediation. The uncertainty is how quickly it changes behavior across Banc of California’s core customer base.

Competitive Rivalry: Very High

California is a knife fight. National banks, super-regionals, local community banks, credit unions, and fintechs all chase the same relationships, deposits, and loan opportunities. The 2023 crisis created openings as some competitors exited or pulled back, but the long-term structure of the market is still intensely competitive.

That shows up where it always does in banking: pressure on margins, pressure on fees, and pressure to keep spending on talent and technology just to stay in the game. In a market like this, the edge doesn’t come from avoiding competition—it comes from operating with enough discipline and differentiation to keep winning customers anyway.

XI. Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: Emerging

The PacWest merger pushed Banc of California into a more workable scale tier. With 80 full-service branches across California and a small footprint beyond the state, it can spread the heavy fixed costs of banking—technology, compliance, risk management, and operations—across a larger base. It’s getting closer to “efficient scale” for a California-focused regional strategy, even if it’s still nowhere near the cost advantages of the national giants.

Network Effects: Minimal

This isn’t a classic network-effects business. Banc of California can add customers all day long without that automatically making the product better for existing customers the way it would in payments networks or consumer platforms. Some treasury management services can become more valuable as usage grows, but overall, banking here is not a flywheel of users attracting more users.

Counter-Positioning: Limited

Banc of California isn’t counter-positioned against incumbents with a fundamentally different model. It’s not trying to reinvent banking; it’s trying to run a traditional relationship bank with more discipline, better execution, and a sharper focus on its chosen clients. That caps the upside from disruption—but it also means competitors aren’t forced into an existential response.

Switching Costs: Moderate

Business banking is sticky because it gets embedded. Changing banks isn’t just moving money; it’s re-plumbing operating accounts, treasury management, payment workflows, and credit facilities. That friction can create real staying power. At the same time, switching has gotten easier than it used to be as tools and processes become more digital. Banc of California’s approach—earning deeper relationships across multiple products—is designed to make leaving feel like a full operational project, not a quick decision.

Branding: Rebuilding

The governance crisis didn’t just hit the stock price; it hit the brand. The recovery has been real, but it’s not complete. Banc has local presence and relationship credibility in parts of its footprint, yet it doesn’t have the kind of “power brand” that commands premium pricing or near-automatic loyalty.

Cornered Resource: Fortress Capital & Governance

If there’s a true differentiator, it’s this: patient, long-term backing from sophisticated private equity investors who know how to stabilize troubled institutions. In moments like 2023, access to credible capital—and the governance muscle that comes with it—matters. Not many competitors can replicate that combination quickly, especially under stress.

Process Power: Developing

After everything the bank lived through, process is the rebuild. Risk management, credit discipline, and operating rigor are being strengthened, and the PacWest integration has been a real-world test of execution. It’s still early to claim a durable advantage here—but the bank is clearly trying to turn what used to be a weakness into an institutional habit.

Overall Assessment:

Banc of California doesn’t have a dominant moat today. It’s competing in a crowded, aggressive market where the products are similar and the fights are won on pricing, service, and trust. The turnaround is tangible, but the structural advantages are limited. From here, the outcome is less about defensibility—and more about whether management can execute, quarter after quarter, without slipping back into old patterns.

XII. Playbook: Lessons for Founders, Operators & Investors

The Banc of California saga is specific—California banking, a governance blow-up, a private equity rescue, and a crisis merger. But the lessons travel.

Governance is destiny. Banc’s collapse in the Sugarman era wasn’t triggered by a wave of bad loans or an unavoidable macro shock. It came from governance failures: related-party transactions, weak board oversight, disclosures that didn’t hold up, and relationships that were too tangled to manage cleanly. For founders and operators, the point is simple: treat governance like a core product feature, not back-office paperwork.

Growth without guardrails is dangerous. “Growth at all costs” can look brilliant right up until it doesn’t. Rapid expansion, splashy sponsorships, and dealmaking created the appearance of momentum while the foundations—controls, culture, and risk discipline—lagged behind. Real scaling means your underwriting, compliance, and decision-making systems scale with you.

Crisis creates opportunity. Fortress and its partners stepped in when confidence was collapsing. In the regional bank panic, they recognized a crucial distinction the market often blurs in fear: a liquidity crisis is not the same thing as a solvency crisis. That clarity—plus the willingness to act—can create extraordinary openings.

Patient capital enables transformation. Bank turnarounds don’t happen on a quarterly cadence. They take years, and they take credibility. Investors who can bring both capital and governance muscle can create real value—but only if their expectations match the pace of a regulated, trust-based business.

Integration is the hardest part. Mergers don’t succeed because a press release says “synergies.” They succeed because systems, people, and processes actually get stitched together. The core systems conversion, branch consolidation, and headcount reductions after the PacWest merger were painful—and unavoidable—if the combined bank was going to function as one institution.

Regulated industries require different playbooks. Banking isn’t software. You can’t “move fast and break things” when deposits and regulators are involved. Compliance isn’t a box to check; it’s the operating system. Relationships with regulators aren’t optional. Culture and controls aren’t a drag on value creation—they’re the entry ticket.

Know when to pivot. Banc’s second act required abandoning what had previously been rewarded. The shift from growth-at-all-costs to disciplined rebuilding meant choosing profitability and balance-sheet strength over headlines. As Wolff put it in January 2024: “We’re focused on hitting our profitability targets, regardless of the size of the balance sheet.”

Trust takes years to build, moments to destroy. In financial services, trust is the product. Lose it, and everything else—deposits, talent, valuation, strategic freedom—starts to slip. Banc’s governance crisis showed how fast a franchise can unravel, and why the rebuild is always harder than the growth phase that came before.

XIII. Bear vs. Bull Case & What to Watch

Bull Case

Fortress-backed capital and governance provide stability. Banc of California isn’t trying to rebuild on hope alone. It has patient backing from sophisticated investors who’ve done turnarounds before—and who tend to bring tighter oversight along with the capital.

PacWest merger creates scale and efficiency opportunities. The combined bank is now big enough to spread the fixed costs that punish smaller banks—technology, compliance, risk infrastructure—while still pursuing real cost synergies. And so far, the integration narrative has been more “progress” than “panic.”

California economy is a long-term winner. California is volatile, but it’s also enormous and unusually diversified. That mix—technology, entertainment, trade, agriculture, professional services—keeps producing businesses that need exactly what Banc is selling: lending, operating accounts, and treasury services.

Management reset and risk culture transformation underway. The scars from the Sugarman era are part of the bank’s story, but they don’t appear to be driving today’s decision-making. The current leadership team has been executing a more disciplined, risk-aware playbook—exactly what a post-crisis franchise needs.

Trading at discount to tangible book value offers turnaround upside. If the bank keeps hitting profitability and balance-sheet targets, the opportunity is simple: confidence returns, earnings look more “normal,” and the valuation can follow. The upside isn’t magic—it’s a rerating driven by credibility.

Bear Case

California CRE exposure in an uncertain environment. Commercial real estate, especially office, is still working through structural changes from remote and hybrid work. A California-heavy footprint means the bank could feel that stress more acutely if the regional economy softens.

Regional banking model under secular pressure. Fintech, embedded finance, and private credit keep nibbling away at pieces of what banks used to own. It’s not always dramatic, but it is persistent—and it can compress margins and growth over time.

Integration risks from the PacWest merger remain significant. Even when integration is “going well,” the hard parts can show up later: client retention, cultural fit, technology execution, and the operational drag that comes from running a bigger institution.

Net interest margin compression if rates decline. Lower rates can reduce funding costs, but they can also squeeze margins as asset yields reset. If rate cuts outpace how quickly deposit costs fall—or if competition forces deposits to stay expensive—NIM can come under pressure.

History of governance failures is hard to outlive. Trust takes time to rebuild with regulators, customers, and employees. And because the bank’s past is well known, any governance slip would be punished faster and harder than it might be elsewhere.

No defensible moat. Relationship banking helps, but it’s still a competitive, largely commoditized business. Without structural advantages, execution has to stay sharp just to produce solid, peer-like returns.

Key Metrics to Track

-

Tangible book value growth – A clean read on whether the bank is compounding value per share over time.

-

Net interest margin evolution – The scorecard for the balance-sheet reset. Improvement supports the turnaround; sustained compression is a warning sign.

-

Noninterest-bearing deposit mix – A proxy for relationship depth and funding quality. More of these deposits usually means stickier customers and cheaper funding.

-

Credit quality – Nonperforming loans, charge-offs, classified assets, and provisioning are where trouble tends to surface first, especially in California CRE.

-

Efficiency ratio improvement – The simplest test of whether merger synergies are real. If efficiency stalls, integration may be costing more than expected.

XIV. Epilogue & Reflections

So where does Banc of California stand today? Midway through a multi-year turnaround. The hardest operational chores—stabilizing the balance sheet, absorbing PacWest, and getting onto one core system—are largely behind it. The governance catastrophe that nearly ended the franchise is no longer the daily story. But the real test still sits out in front: proving this bank can produce durable, repeatable profitability in one of the most competitive banking markets in the country—without any obvious structural moat to hide behind.

That’s the larger point of this saga. Banc’s second act is a window into what regional banking looks like now: consolidation under stress, credibility as the scarce resource, and private equity increasingly showing up as the backstop. When confidence breaks, the modern rescue playbook often isn’t a quiet recovery—it’s a recapitalization, a governance reset, and an operating overhaul engineered to survive the next shock. Whether you love that or hate it, it’s becoming a defining feature of how mid-sized American banks get saved.

There are still unanswered questions. Does the Fortress model work over the long arc? Private equity doesn’t stay forever—eventually there’s an exit, whether that’s through a sale, a distribution, or something that looks like a public-market handoff. What happens when the sponsor’s time horizon collides with banking’s slow, compounding nature? And can Banc build a franchise strong enough that it doesn’t need “patient capital” to be its identity?

It’s also hard not to be struck by how quickly the plot turned at key moments. Governance issues went from uncomfortable to existential with shocking speed. When the bank was most vulnerable, the capital arrived decisively—and with it, control. And then, in the middle of the 2023 regional banking panic, the crisis itself created the opening for a transformational merger that probably couldn’t have happened in calm waters.

If there’s one lesson here that travels beyond banking, it’s this: culture, controls, and governance aren’t paperwork. They’re the product. They’re what depositors, regulators, employees, and investors are actually buying when they decide to trust an institution. Ignore that, and growth becomes a trap. Get it right, and you earn the right to survive the moments when everyone else is panicking.

The U.S. banking system is remarkably adaptive. Banks fail. They get rescued. They merge. They reinvent. Consolidation keeps marching. Private capital keeps stepping into the gaps. And the survivors keep competing for the relationships that power the real economy.

Banc of California’s story, for all the twists so far, is still unfinished. A bank that made it through scandal, scrutiny, leadership churn, and a statewide crisis now has the chance to prove it can build something that lasts. Whether it does will come down to execution, the cycle, and whether the lessons of the first collapse have truly become habits—not just talking points.

XV. Further Reading & Resources

Top 10 Long-Form Resources:

-

SEC Filings (10-Ks, 2018–2024) – The governance crisis, the Fortress investment, and the PacWest merger—straight from the company’s own disclosures.

-

"The Fall of Steven Sugarman" – American Banker’s investigative series on the governance breakdown and what it set in motion.

-

"How Fortress Turned Around a Troubled California Bank" – A case study on what private equity looks like when it steps into a regulated turnaround.

-

"The 2023 Regional Banking Crisis: Lessons and Aftermath" – Federal Reserve analysis of SVB, Signature, First Republic, and the policy response that followed.

-

"Banking on America" by Kathleen Day – Broader context on U.S. banking regulation and why regional banks keep consolidating.

-

"The Acquirer's Multiple" by Tobias Carlisle – A useful value-investing framework for thinking about distressed, misunderstood situations.

-

SNL Financial/S&P Global Market Intelligence Reports – Peer comparisons and California banking market data.

-

FDIC Community Banking Studies – Research on the economics, strengths, and vulnerabilities of community and regional banks.

-

"Private Equity in Banking: Opportunity or Risk?" – Brookings Institution paper on the tradeoffs when PE enters regulated financial institutions.

-

Banc of California Investor Presentations (2023–2025) – Management’s view of the turnaround: strategy, priorities, and targets.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music