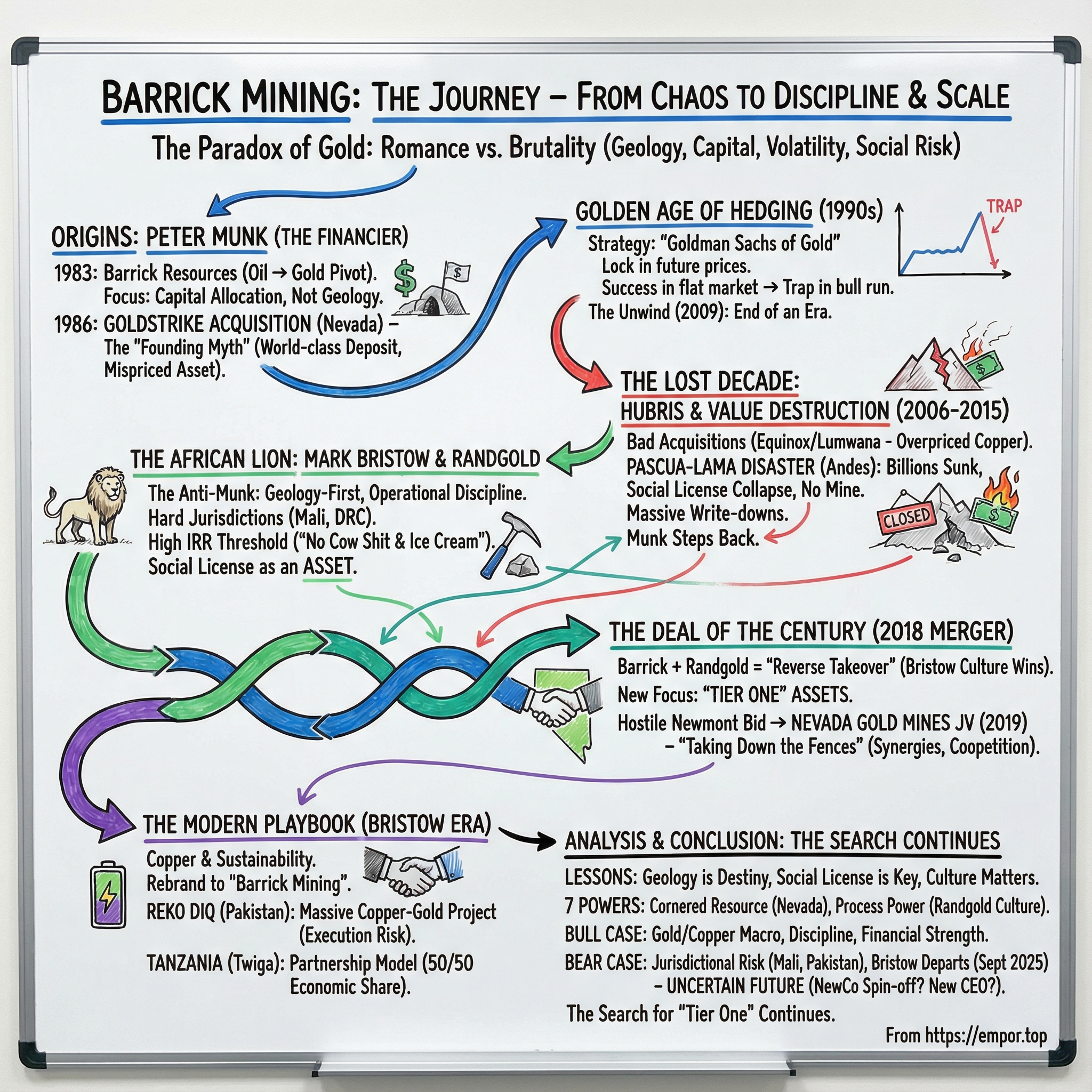

Barrick Mining: The Financier, The Geologist, and The Search for Tier One

I. Introduction: The Paradox of Gold

Gold is the oldest kind of money. Civilizations have fought over it for thousands of years. Central banks still stack it in vaults. And it’s so scarce that if you gathered every ounce ever mined, you could fit it into a cube roughly 70 feet on each side.

So why are the companies that pull it out of the ground so often awful businesses?

Because gold mining is a game with all the romance on the surface—and all the brutality underneath. It’s geology, first and foremost: you don’t choose where the gold is, and you can’t A/B test an ore body. Then it’s capital intensity: you spend for years, sometimes decades, before you really know what you’ve built. Add commodity volatility: miners don’t get to set prices, they get to accept them—prices discovered in global markets that swing on interest rates, geopolitics, and fear. And finally, the wildcard that makes spreadsheets tremble: political and social risk. The “asset” is wherever a government says it is, for as long as that government—and the local community—keeps agreeing.

Against that backdrop, Barrick is the rare miner that tried to build something that looked less like a prospecting outfit and more like a machine. Founder Peter Munk built Barrick into the world’s largest gold company in under twenty-five years—not by being the best geologist in the room, but by being the sharpest financier. He treated mining like a set of risks to be managed, hedged, and engineered.

That’s the first half of this story.

The second half begins when that very approach—so brilliant in one era—stops working, and nearly wrecks the company. Barrick stumbles into a lost decade of bad timing, bloated projects, write-offs, and a collapse in trust with the places it operated. And then, in 2018, the company effectively flips inside out through a merger with Randgold Resources, bringing in Mark Bristow: a South African geologist-operator who built his career in hard jurisdictions and had little patience for boardroom mythology.

To understand the scale Barrick operates at today, consider where it stood in 2024: 3.91 million ounces of gold produced, plus 195,000 tonnes of copper. All-in sustaining costs were $1,484 per ounce of gold and $3.45 per pound of copper. And as of December 31, 2024, Barrick reported proven and probable reserves of 89 million ounces of gold and 18 million tonnes of copper.

Impressive. But the numbers are the output, not the plot.

The plot is a philosophical tug-of-war over what kind of company Barrick should be. In the Munk era, Barrick leaned into finance—hedging production years ahead and running the business like a trading desk that happened to own mines. In the Bristow era, Barrick became obsessed with operations and “Tier One” assets, with a sharper focus on discipline, longevity, and earning the right to operate in-country.

That transition wasn’t gentle. Between the early-2000s peak and Bristow’s takeover, Barrick’s missteps piled up: a disastrous mega-project in the Andes, ill-timed acquisitions, and a painful lesson the whole industry eventually learns—the hard way—that without a social license to operate, a world-class deposit can still be worth zero.

And just as this modern version of Barrick seemed set in its new identity, another twist arrived: Bristow’s sudden departure in September 2025, opening a fresh chapter with an ending no one can claim to know yet.

From Nevada’s mountains to the jungles of the Democratic Republic of Congo, from Pakistan’s deserts to Tanzania’s courtrooms, this is the story of Barrick Mining.

II. The Origins: Peter Munk and The Anti-Miner

In 1944, a seventeen-year-old Jewish boy named Peter Munk boarded a train out of Nazi-occupied Budapest. The escape route had been arranged by Rudolf Kastner of the Zionist Aid and Rescue Committee, after secret negotiations with Adolf Eichmann—part of the grim “blood for goods” deals that traded money, gold, and diamonds for Jewish lives.

Munk got out. His mother didn’t. Unable to secure passage, she was deported to Auschwitz. She survived the camp, but later died by suicide.

Munk first reached Switzerland, then set his sights on Canada. He arrived in 1948, initially on a student visa. In 1952 he graduated from the University of Toronto with a degree in electrical engineering. He was new, unknown, and barely spoke English. But he felt welcomed—and he never forgot it. Years later he would say, in a line that became famous in Canadian business circles: “I arrived in this place not speaking the language, not knowing a dog... This is a country that does not ask about your origins; it only concerns itself with your destiny.”

He wanted that destiny badly.

His first big swing came in 1958, when he co-founded Clairtone Sound Corporation, a high-end stereo manufacturer with the kind of sleek modernist design that ended up in magazines and celebrity homes—including Frank Sinatra’s. For a moment, Clairtone looked like Canadian ambition made real.

Then it fell apart. By the late 1960s, the company collapsed under production problems, cost overruns, and a disastrous government bailout. Munk’s reputation cratered with it.

So he left and rebuilt far from Bay Street. After Clairtone, Munk and David Gilmour invested in oceanfront land in Fiji and developed a resort. That venture grew into the Southern Pacific Hotel Corporation, which at its peak included 54 resorts across Australia and the South Pacific. He proved he could create value again. But when he returned to Canada in 1979, he found the establishment had a long memory. Bankers and insiders viewed him, as Munk later put it, as “a fugitive and a loser.”

That chip on his shoulder wasn’t a footnote. It became the engine.

In 1980, Munk created Barrick Petroleum to invest in oil. He quickly concluded the sector was ruinous. Then came the pivot: after acquiring a small company called Camflo Mines, Barrick exited oil and, almost overnight, became a mining company. Prospecting began in 1983. What started as a less-than-spectacular petroleum story began to turn into something else entirely.

But Barrick was never going to look like a typical Toronto miner. Munk wasn’t a geologist. He wasn’t an engineer. He didn’t build his identity around rocks. He built it around deals.

To him, gold mining was an industry full of operational brilliance and financial chaos—companies run by people who could interpret ore bodies but not capital markets; executives who overpaid, overbuilt, and then tried to outwait reality. Munk’s conviction was simple: mining didn’t need more romance. It needed discipline.

Barrick Resources Corporation went public on May 2, 1983, listing on the Toronto Stock Exchange. The early moves were small—mines in Ontario and Quebec. But Munk wasn’t building a portfolio for its own sake. He was hunting for the one asset that would change the trajectory of the company.

He found it in Nevada.

In 1986, Barrick began building its Nevada footprint by acquiring the Goldstrike mine for about $62 million. It didn’t look like a crown jewel at the time. Goldstrike was underperforming, producing only around 40,000 ounces per year. To the seller, it was a marginal asset—something to clean up and move on from.

Barrick acquired full ownership in December 1986. Mining began in 1987. And then the ground told a different story.

After the acquisition, Barrick’s geologists established that Goldstrike sat on one of the largest gold deposits in North American history. On the Goldstrike property along Nevada’s Carlin Trend, Barrick developed the Betze-Post and Meikle mines—Betze-Post becoming the richest and most productive mine in the United States, and Meikle the largest underground mine in North America.

Goldstrike became Barrick’s founding myth because it was more than a mine. It was proof of concept. Munk’s entire worldview—assets get mispriced, markets get it wrong, discipline can beat tradition—was suddenly validated by the biggest possible exclamation point.

Even the setting sounded like scale. Goldstrike sits in the northern Carlin Trend in Eureka and Elko Counties, roughly 50 kilometers northwest of Elko. The Carlin Trend itself is a dense belt of mines—about 8 kilometers wide and 65 kilometers long—and it has produced more gold than any other mining district in the United States.

Years later, in 2016, Goldstrike would produce 1.1 million ounces of gold, ranking third globally behind Grasberg in Indonesia and Muruntau in Uzbekistan.

Munk took a lesson from all of this that would shape the next era of Barrick: you didn’t need to be a geologist to build a mining empire. You needed to be a capital allocator—someone who understood mispricing, risk, and timing. Most of all, you needed a way to survive the one thing no miner controls: the gold price.

That insight would become Barrick’s defining move in the 1990s. And in time, it would also become the thing that nearly broke the company.

III. The Golden Age of Hedging

Through the 1980s and into the early 1990s, gold was a stubborn, uncooperative commodity. Prices were flat to falling—the worst possible backdrop for an industry that has to spend huge sums upfront, wait years to build, and then hope the economics still work when the first bar finally comes out of the mill.

Most miners dealt with that uncertainty the old-fashioned way: drill, build, and cross your fingers. Peter Munk didn’t do faith-based investing. He looked at gold mining and saw a business with one fatal flaw: you do all the work, and the market gets to decide whether you make money.

So Barrick did something that made traditional miners roll their eyes and made Wall Street lean in. It hedged.

In the 1990s, Barrick turned gold hedging into a core strategy—less as a defensive move, and more as a profit engine. The mechanics were complex but the idea was simple: lock in future prices and manufacture stability in a volatile world.

Here’s how it worked in broad strokes. Barrick would borrow gold—often sourced from central banks—through its trading banks, sell it at the current market price, and invest the cash. If the interest it earned on that cash exceeded the cost of borrowing the gold, Barrick captured the spread. Layer on forward sales and option premiums, and Barrick wasn’t just mining metal. It was running a derivatives machine alongside the mines.

At its peak, the program looked like a cheat code. Over a ten-year stretch, hedging added hundreds of millions in revenue and earnings, delivering an average premium of about $46 per ounce on every ounce sold. In 1997, the company celebrated the hedging program’s tenth anniversary by posting its best year yet—an $88 per ounce premium, translating into $269 million of additional revenue and $200 million of added earnings.

Then came early 1998, and the contrast got even more dramatic. In the first quarter, Barrick reported $79 million in additional revenue from hedging and realized an average price of $400 an ounce, while the average spot price was $295. Competitors were price takers. Barrick, thanks to its hedge book, was playing a different game.

Munk leaned into it. Barrick’s annual reports openly bragged about how much the strategy boosted results. Harvard Business School wrote case studies on it. Investors loved it. In 1992, for example, American Barrick produced and sold over 1.28 million ounces at an average realized price of $422 per ounce, while the market price averaged $345.

For a while, it really did look like Munk had solved gold mining’s core problem: how to run a profitable company when your product price swings wildly and you can’t control it.

But hedging only feels like genius in one direction.

In 2001, gold began a bull run that would rewrite the entire industry’s story. Prices surged from under $300 an ounce to over $1,000, fueled by factors like a weakening dollar, central bank money creation, and growing demand from emerging markets. And the very thing that made Barrick so steady in the 1990s—locking in future prices—now trapped it.

Barrick was committed to selling gold at yesterday’s levels while the world price marched higher.

The company said in 2003 it would stop entering new hedge contracts, but the existing exposure didn’t just disappear. By the late 2000s, the hedge book had become a financial weight the market couldn’t ignore. Barrick’s hedge liabilities climbed sharply—from $1.9 billion in 2004 to $5.6 billion—turning what had once been an advantage into a visible problem. As one CIBC analyst put it, a meaningful portion of investors simply wouldn’t buy Barrick because of the hedge book.

In 2009, Barrick finally made the break. It announced a massive equity issue—expanded to as much as $4 billion—that would be used to largely eliminate its roughly 9.5-million-ounce hedge position. The move diluted existing shareholders by more than 12%, increasing the share count to as much as 982 million from 873 million. Barrick also took a $5.6 billion charge in the third quarter as hedge-related liabilities were brought onto the balance sheet.

That unwind was more than a financial transaction. It was the end of an era.

Barrick’s identity as the “Goldman Sachs of gold”—the financial engineering champion that could outsmart the commodity cycle—was effectively over. And the next era wouldn’t be defined by clever trades, but by far more painful realities.

IV. The Lost Decade: Hubris and Value Destruction

If the 1990s were Barrick’s peak as a financial engineer, the stretch from 2006 to 2015 was its low point as an operator. The company that once looked unstoppable started lighting capital on fire—through expensive acquisitions, sprawling projects, and the creeping realization that you can’t spreadsheet your way through the physical world.

It began with ambition. Gold had made Barrick famous; now management wanted a second engine. Copper, they reasoned, was different from gold: an industrial metal tied to real economic growth, with demand rising in emerging markets, especially China. The logic wasn’t crazy. The timing was.

In 2011, Barrick moved to buy Equinox Minerals through an all-cash offer: C$8.15 per share, roughly C$7.3 billion total. The prize was Equinox’s Lumwana copper mine in Zambia. Lumwana was built to last—enough reserves for decades, and it had reportedly cost about $1 billion to develop. But Barrick paid a roughly 30% premium at what would prove to be close to the top of the copper cycle. In a period when commodity prices were starting to turn against miners, Barrick had just written a very big check for diversification.

And as painful as Equinox would look in hindsight, it was still only the opening act. The real disaster was already underway in the Andes.

Pascua-Lama was meant to be Barrick’s masterpiece: a massive, high-altitude open-pit mine straddling the Chile-Argentina border, more than 4,500 metres up in the southern Atacama. It was designed to produce gold and silver, with copper and other minerals in the mix. The deposit was undeniably world-class—estimated at around 17 million ounces of gold and 635 million ounces of silver, with roughly three-quarters of it on the Chilean side and the rest in Argentina.

The ore wasn’t the issue. Execution was.

Barrick initially expected construction to cost about $3 billion. That estimate eventually ballooned to around $8.5 billion as labour, materials, and energy costs surged. Those overruns alone were brutal—but they weren’t what truly killed the project.

What broke Pascua-Lama was the collapse of what miners call the social license to operate.

The site sat near glaciers that local communities relied on for water. The project triggered protests, petitions, and sustained political pressure in Chile. Barrick at one point proposed relocating glaciers—an idea so audacious, and so environmentally charged, that it became gasoline for opposition. Over time, the controversy turned into enforcement. Barrick ultimately halted construction in October 2013 as costs escalated and environmental mismanagement caused delays and setbacks.

Years later, on September 17, 2020, Chile’s First Environmental Court ordered the definitive closure of the Pascua mining project and fined Barrick over $9.7 million. The company faced 33 charges, including contaminating the Estrecho River without informing nearby communities and failing to adequately evaluate impacts on Andean glaciers.

By then, the financial damage was already done. Pascua-Lama had become a symbol of everything that went wrong in Barrick’s lost decade: a project whose costs spiraled to above $8 billion from earlier projections, and whose fate was ultimately decided not in a boardroom, but on the ground—by regulators, local communities, and the limits of what could be built responsibly in a sensitive place.

The write-downs came in waves. Barrick recorded massive impairment charges, including billions tied to Pascua-Lama. In one quarter alone, the company took an $8.7 billion hit, posting a loss of $8.6 billion, and cut its quarterly dividend to five cents per share. The write-offs weren’t just accounting—each one was an admission that years of capital, time, and executive certainty had produced nothing you could run.

Pascua-Lama became one of the most expensive mining failures of its era not because the deposit was fake, but because Barrick’s old instincts—financial engineering, scale, momentum—didn’t translate to the messy realities of permitting, environment, and trust. In mining, you can’t hedge your way around the community. You can’t out-leverage gravity. You have to earn the right to operate, and then you have to execute.

By 2014, the founder himself was stepping back. Peter Munk announced he would retire as Chairman and leave the board at the company’s 2014 annual meeting. John L. Thornton, appointed co-chairman in 2012, would take over as Chairman.

Munk had built Barrick from a small player into the global leader. But the empire he left behind was weighed down by debt, controversy, and a crisis of credibility. Barrick needed transformation. What almost no one saw coming was just how radical it would be—or who would end up delivering it.

V. The African Lion: Mark Bristow and Randgold

While Barrick was burning cash in the Americas and watching Pascua-Lama implode, a very different kind of miner was thriving in one of the hardest places on Earth to do business: West Africa.

Mark Bristow was born in Estcourt, South Africa. He went to Estcourt High School, then earned BSc and PhD degrees in geology from the University of Natal. In the 1970s, he served as an officer in the South African Army and saw active service against guerrillas in Swaziland and Angola.

Bristow was, in almost every way, the mirror opposite of Peter Munk. Munk had built Barrick by turning mining into a finance problem. Bristow built Randgold by treating mining as what it actually is: a geology-and-execution problem. Where Munk worked the phones and the capital markets, Bristow showed up. He became known for traveling to sites himself—often by motorcycle—rather than running everything from a distance. Where Barrick’s world revolved around Toronto boardrooms and investment banks, Bristow built teams of local managers and leaned on African geologists. And while Barrick projected scale and polish, Randgold was run from a seven-person headquarters on Jersey, chosen as much for efficiency and tax advantages as for any corporate symbolism.

His career path reflected that operator’s mindset. Bristow joined Rand Mines in 1981, then became head of exploration at Randgold & Exploration. In 1995, he created Randgold Resources, and in 1997 he listed it on the London Stock Exchange.

The defining bet came next: Bristow pushed out of South Africa and into French-speaking West Africa—territory many anglophone mining companies had largely ignored through the Cold War. While majors chased “safe” jurisdictions, he went where others didn’t want to go: Mali, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Ivory Coast.

Randgold became, above all, a West African gold company. Headquartered in Jersey, it traded on both London and NASDAQ until it merged with Barrick in December 2018. It was established in 1995, first listed in 1997, commissioned the Morila mine in 2000, and then commissioned the Loulo mine in 2005.

But the real differentiator wasn’t the map. It was the discipline.

Randgold’s approach was widely described as science and geology over what one analyst praised as “Goldman Sachs-style corporate capitalism.” Bristow set a rule that was almost offensively strict for a cyclical, ego-driven industry: every project had to clear a 20% internal rate of return assuming $1,000 gold. If it couldn’t, they didn’t build it. Not “maybe, if prices rise.” Not “we’ll fix it with synergies.” Just no.

The result was a company that built fewer mines than many peers, but built mines that worked—profitable from the start, and designed to stay that way.

By 2018, Randgold had become one of the U.K.’s standout corporate success stories: a roughly 4,000 percent return since the end of 1999, the best-performing stock in the FTSE 100 Index by that measure. It had never reported a quarterly loss and never taken a write-down—an almost absurd record in an industry where write-downs are practically a rite of passage.

Bristow didn’t hide his view of the competition. “The industry blows its brains out every time. The reason we’re still in the industry is because the competition isn’t that sharp,” he said in 2014.

And he had no patience for the idea that you could buy your way out of bad geology. “If you mix cow shit and ice cream, you never improve the taste of the cow shit,” he told journalists. “The principle behind that is stick to ice cream.” Crude, but precise: don’t try to rescue weak assets through mergers. Own great rocks, run them well, and let the ore body do what it’s supposed to do.

By 2018, Randgold had grown into a mid-tier producer with a market capitalization of about $6 billion, having scaled from exploration into multi-mine operations producing more than 1 million ounces a year.

Operating in places like Mali and the DRC wasn’t just a technical challenge—it was a political one. Bristow navigated shifting mining codes and rising resource nationalism with a partnership posture: invest in communities, keep lines open with governments, and stay on the right side of compliance so the business can keep running.

Because Bristow understood something Barrick had learned the hard way at Pascua-Lama: in modern mining, “social license” isn’t a slogan. It’s an asset. A world-class deposit is still worth zero if the host government turns against you, or if local communities decide they’re done.

By the late 2010s, the contrast was almost too clean. Barrick was huge—and wounded. Randgold was smaller—and sharp.

And that set the stage for one of the most unusual corporate transactions the mining industry had ever seen.

VI. The Deal of the Century

On September 24, 2018, the mining world did a double take. Barrick and Randgold—two companies that represented almost opposite philosophies—announced a blockbuster combination that would reshape the industry.

Structurally, Barrick agreed to buy Randgold in an all-stock deal valued at about $6.5 billion, part of a broader transaction framed as an $18 billion-plus share-for-share merger. On paper, it looked like the standard script: Canada’s biggest gold miner absorbing a mid-sized African specialist.

In reality, it was closer to a reverse takeover.

Barrick’s executive chairman John Thornton had been trying to overhaul Barrick’s culture and operating model. The merger terms were, in effect, a way to recruit the one leader in the sector with a proven alternative playbook: Randgold’s Mark Bristow, along with CFO Graham Shuttleworth. Bristow—who’d spent years openly criticizing the industry’s bad habits, Barrick included—was now set to run the combined company as President and CEO.

“We have no intention of changing the way we run the company at Randgold,” Bristow said. And, he added, that was exactly what he and Thornton agreed on.

The message to investors was simple: stop judging us by how many ounces we produce. Judge us by the returns we generate.

That’s where “Tier One” moved from buzzword to organizing principle. Barrick defined a Tier One Gold Asset as one that could make money at $1,400 gold, run for at least a decade, produce at least 500,000 ounces a year, and sit in the lower half of the industry cost curve.

In the merger announcement, five mines were held up as the core of this new Barrick: Cortez and Goldstrike in Nevada, Pueblo Viejo in the Dominican Republic, Kibali in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Loulo-Gounkoto in Mali. Randgold shareholders would end up with 33% of the combined company, and the transaction closed in December 2018.

Then Bristow did what Bristow does: he immediately went on offense.

Within weeks, he launched what looked like a hostile takeover bid for Newmont, Barrick’s largest rival. In February 2019, Barrick announced a hostile $19 billion offer. The pitch was synergy: the companies argued a deal could unlock billions in operational value.

The industry was stunned. But the more you looked at it, the more it seemed like the bid wasn’t really about buying Newmont.

It was about Nevada.

Barrick and Newmont had spent decades as neighbors—and enemies—in the same goldfields, operating right on top of one another across the same geological trends. Two sets of processing plants. Two sets of haul roads. Two sets of teams. And, most absurdly, property lines that cut through ore bodies. They were competing against each other while the rocks quietly begged to be mined as one system.

Newmont rejected the takeover bid and countered with something more logical: merge the Nevada operations instead.

That idea became Nevada Gold Mines. Barrick and Newmont signed an agreement to combine their Nevada mining operations, assets, reserves, and teams into a single joint venture. It officially formed on July 1, 2019, with Barrick owning 61.5% and operating the business, and Newmont owning 38.5%.

The scale was extraordinary: a network of underground and surface mines plus an industrial maze of processing infrastructure—autoclaves, roasters, oxide mills, a flotation plant, and heap leach facilities. In 2018, the combined Nevada assets produced 4.1 million ounces of gold—roughly double the next-largest gold mine.

And the economics were the point. The JV was expected to capture around $500 million in average annual pre-tax synergies in its first five full years, projected to translate into roughly $5 billion of pre-tax net present value over 20 years.

Bristow called it the end of a fight that had dragged on for more than two decades. “We are finally taking down the fences to operate Nevada as a single entity,” he said.

Those “fence wars” were real. Barrick and Newmont had chased ore bodies right up to their boundary lines and then stopped—sometimes even when the same deposit clearly continued on the other side. Haul trucks would pass each other on the same roads headed to different plants. Duplicate infrastructure sat in the same desert. The result was predictable: higher costs, lower recoveries, and stranded value.

In other words: the easiest kind of value to unlock—the kind that was already there, just blocked by corporate pride.

In barely half a year, Bristow had changed Barrick’s trajectory. First, he merged with Randgold to import an operating culture built on discipline. Then, by forcing the conversation with Newmont, he helped create Nevada Gold Mines—the world’s largest gold-mining complex. The hostile bid that wasn’t became a masterclass in corporate chess.

VII. The Modern Playbook: Copper, Reko Diq, and Sustainability

With the Randgold integration largely bedded down and Nevada Gold Mines up and running, Bristow turned to the next strategic obsession: copper.

The rationale was straightforward. Gold would remain Barrick’s anchor, but copper offered something gold never could—structural demand growth. Electrification takes metal. Electric vehicles, solar, wind, grids: they all require far more copper than the fossil-fuel world they’re replacing. In Barrick’s framing, gold is the store of value; copper is the wiring of the future. If you wanted to build a mining company that could thrive beyond the next gold cycle, you needed both.

That shift became explicit in May 2025, when Barrick Gold Corporation formally changed its name to Barrick Mining Corporation. The rebrand was meant to signal a broader identity: not just a gold company, but a diversified miner with a growing copper pipeline. Barrick said its ambition was to become “the world’s most valued gold and copper exploration, development and mining company.”

The company also changed its NYSE ticker from GOLD to B, while the TSX symbol ABX stayed the same.

The flagship of the copper push was Reko Diq in Pakistan—one of the largest undeveloped copper-gold deposits on Earth.

Reko Diq sits in the Chagai district of Balochistan, Pakistan’s largest district by area, close to the borders with Afghanistan and Iran. Ownership is split 50% Barrick, 25% among three federal state-owned enterprises, and 25% held by the Government of Balochistan—15% on a fully funded basis and 10% free carried.

It’s a planned mine, but the size is the point: an estimated 5.9 billion tonnes of ore, grading around 0.41% copper, plus gold reserves of about 41.5 million ounces, with a mine life of at least 40 years.

Getting there, though, was anything but smooth.

The project effectively froze in 2011 after the mining lease application was rejected. Pakistani officials later said the lease had been secured in a non-transparent manner and was terminated. That decision triggered years of high-stakes international arbitration, including proceedings at ICSID, after the project company, TCC, sought $8.5 billion in damages when Balochistan’s mining authority rejected the lease application.

Barrick re-entered the picture in 2022, after the long-running legal dispute was settled. Suddenly, what had been a cautionary tale became something Pakistan wanted to showcase: a marquee investment as the country tried to attract serious capital into its minerals sector.

In December 2022, Barrick said the “reconstitution” of Reko Diq was completed—clearing a major hurdle toward turning it into the kind of long-life, globally significant copper-gold mine that would reshape Barrick’s copper portfolio and, in the company’s telling, deliver benefits to Pakistani stakeholders for generations.

The project is expected to cost about $7 billion and is targeted to begin production by the end of 2028. Barrick reported that Reko Diq added 13 million ounces to its gold reserves in 2024. The company has also said the mine is expected to produce around 200,000 metric tons of copper per year in its first phase, with output set to double after an expansion, and projected free cash flow of more than $70 billion over 37 years.

And then there was Tanzania—where the “new Barrick” playbook wasn’t about geology at all. It was about legitimacy.

When Bristow took over in 2019, Barrick’s Tanzanian situation was an existential mess inherited through its subsidiary, Acacia. The dispute had started in 2017, when Tanzania hit Acacia with a $190 billion U.S. tax bill, accused it of tax evasion, banned concentrate exports, and effectively choked off operations.

Old Barrick would have treated this like a legal problem to be managed at arm’s length. Bristow treated it like a relationship that had broken—and needed to be rebuilt in person. He flew to Dar es Salaam himself.

Barrick and the Government of Tanzania reached a settlement designed to reset the entire operating model. The deal included a $300 million payment to settle outstanding tax and other disputes, the lifting of the concentrate export ban, and an agreement to share future economic benefits from the mines on a 50/50 basis. It also established an Africa-focused international dispute resolution framework.

To operationalize the new partnership, Barrick formed Twiga Minerals Corporation to manage the Bulyanhulu, North Mara, and Buzwagi mines. Under the agreement, Tanzania would acquire a 16% stake in each mine and receive its half of the economic benefits through taxes, royalties, clearing fees, and participation in cash distributions made by the mines and Twiga.

“Rebuilding these operations after three years of value destruction will require a lot of work, but the progress we’ve already made will be greatly accelerated by this agreement,” Bristow said. “Twiga, which will give the government full visibility of and participation in operating decisions made for and by the mines, represents our new partnership not only in spirit but also in practice.”

This became the Bristow template: don’t try to out-lawyer host governments. Make them true economic partners. In an industry that had long relied on contracts, courts, and distance—especially in developing countries—Bristow was betting on something more operational, more political, and more durable: shared ownership of outcomes.

VIII. Playbook: Lessons for Builders and Investors

Barrick’s story isn’t just a mining story. It’s a case study in how strategy, incentives, and leadership collide—especially in industries where the real world has more veto power than the spreadsheet.

Geology Is Destiny

Peter Munk built Barrick by treating mining like a financial problem. For a long time, that looked like genius. Hedging created stability and extra profit in an unstable business—until the cycle flipped and the same hedge book became a trap.

And Pascua-Lama is the brutal counterexample to financial confidence: incredible ore, and conditions that made execution—and permission—nearly impossible. In resource extraction, the rock doesn’t care what your model says. The quality, accessibility, and consistency of the ore body set the boundaries of what’s possible.

Bristow gets that at a cellular level because he’s a geologist. “Tier One” isn’t just a tagline; it’s an attempt to bake that reality into the company’s decision-making. If the geology isn’t strong enough to support long life, high throughput, and low costs, it doesn’t belong at the center of Barrick’s strategy.

Social License Is an Asset—Perhaps the Most Important One

Pascua-Lama had billions in capital sunk into it and a deposit any miner would envy. It still ended up worth effectively nothing—because the surrounding communities, regulators, and courts withdrew their consent.

That’s what “social license” really means: the unwritten permit underneath all the written ones.

Now compare that with Tanzania. Bristow didn’t treat the dispute as something to win from a distance. He treated it as a broken relationship that had to be repaired, face to face, with real economic alignment. The 50/50 framework and the creation of Twiga gave the government participation, visibility, and a share of the upside. It’s more expensive in the near term, but it changes the durability of the whole operation.

The Right Leader at the Right Time

Munk was exactly the leader Barrick needed in its ascent: financially sophisticated, aggressive, and willing to use structure and leverage to build scale quickly. That playbook created an empire.

But when the problems became operational—execution risk, cost blowouts, community opposition—the skills that built Barrick weren’t the ones that could save it.

Bristow was built for the turnaround. He understood mines as physical systems, not just assets on a slide deck. He pushed discipline, returns, and credibility with host countries. And in a business where one bad project can erase a decade of value, that mindset isn’t a nice-to-have. It’s survival.

Mergers of Equals Can Work—If Culture Aligns

Most “mergers of equals” fail because they’re theater. One side wins, the other side resents it, and the best people quietly leave.

Barrick-Randgold worked because, culturally, it wasn’t a merger of equals at all. Barrick bought Randgold on paper, but Randgold’s operating culture took over in practice. Bristow and his team set the tone, and the legacy Barrick organization adapted around it. In an industry where integration is usually where value goes to die, that was the difference.

Coopetition Is the New Normal

The Nevada Gold Mines joint venture is the cleanest example of modern mining logic: compete where you must, cooperate where it’s obviously irrational not to.

Barrick and Newmont remained global rivals, but in Nevada they stopped the fence wars and ran the ore body like the single system it always was. One operator, integrated infrastructure, fewer duplicated costs—and more gold recovered from the same ground.

In other words, they didn’t “discover” value. They stopped destroying it.

IX. Analysis: Powers and Forces

To understand Barrick’s competitive position, you have to look past the quarter-to-quarter noise and into the structure of the business. Gold mining is a brutal industry. Most of what matters is decided by forces you don’t control: geology, governments, capital cycles, and operating discipline. Barrick’s edge—or lack of it—shows up when you map those forces out.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Framework

Cornered Resource (Strong): Barrick’s Nevada footprint sits on the Carlin Trend—arguably the most prolific gold-bearing geological system in the Western Hemisphere. It’s a northwest-southeast belt, about 8 kilometers wide and 65 kilometers long, and it has produced more gold than any other mining district in the United States. This is the kind of advantage you can’t buy or copy. You either have it, or you don’t.

Process Power (Medium): The Randgold operating system—tight investment discipline, empowered local teams, and real community partnership—can be described on a slide, but it’s hard to reproduce in real life. Bristow built it over decades. Getting that culture to stick inside a much larger organization required repetition, enforcement, and time.

Scale Economies (Strong in Nevada): Nevada Gold Mines is scale economies made physical. When you operate a dense cluster of mines and processing plants as one system, you get a kind of efficiency no standalone competitor can match. A big portion of the value comes from integrated mine planning, better sequencing between pits and underground operations, and routing ore to the right processing facility. And it’s also about eliminating pure duplication—like combining adjacent assets such as Turquoise Ridge and Twin Creeks and running them as a single mine.

Porter's Five Forces

Supplier Power (High): Suppliers have leverage everywhere you look. Heavy equipment is effectively an oligopoly—think Caterpillar and Komatsu. Labor can be unionized. And the biggest supplier of all is the host government, because it controls the permit that matters most: the right to operate. Barrick’s experience in Tanzania made that painfully clear—political friction can erase years of value far faster than operational excellence can create it.

Buyer Power (Minimal): Gold is a global commodity with transparent pricing and deep liquidity. Barrick can’t negotiate with “customers” the way most companies can. It sells into a market and takes what the market gives.

Threat of Substitutes (Complex): Gold’s role is part industrial metal, part financial asset, part cultural object. Bitcoin and other digital assets are a real competing narrative for gold-as-money, though still unproven as a full substitute. On the copper side, substitution is more practical than ideological—aluminum can replace copper in some uses, but not universally.

Industry Rivalry (Shifting): Mining has historically been cutthroat, and in places like Nevada that rivalry turned into absurd “fence wars.” The Nevada JV signaled something new: sometimes the smartest move is to compete globally but cooperate locally, especially when the geology is shared. With reserves declining across the industry, the pressure for consolidation and collaboration only rises.

Threat of New Entrants (Low): New entrants face the worst combination of obstacles: massive capital requirements, long development timelines, regulatory and permitting complexity, and the simple reality that the best ore bodies are finite and largely already spoken for.

The Key KPIs for Tracking Barrick

If you want to track whether Barrick is winning the long game, two metrics tell you more than most headlines:

-

All-In Sustaining Costs (AISC) per ounce: AISC tries to capture what it really costs to keep the business running—not just digging and processing, but sustaining capital, exploration, and corporate overhead. Barrick’s 2024 AISC of $1,484 per ounce only means something in context: how much margin does that leave at prevailing gold prices, and how resilient is that margin if prices fall?

-

Reserve Replacement Ratio: A miner is always running down an inventory it can’t manufacture. Every ounce produced has to be replaced through exploration, expansion, or acquisition—or the company slowly shrinks. Barrick reported continuing reserve additions, growing attributable proven and probable gold mineral reserves by 17.4 million ounces (23%) before accounting for 2024 depletion. That replenishment is the difference between a company that compounds and a company that eventually runs out of runway.

X. The Bull and Bear Cases

The Bull Case

The macro setup for gold has rarely looked better. Inflation has stayed stickier than central banks expected. Fiscal deficits in developed economies keep widening. And central banks have been buying gold aggressively as more countries look to diversify away from dollar reserves. In that kind of world, Barrick offers something investors often want but rarely get in one package: scale and leverage to the gold price—backed by a reserve base of 89 million ounces of gold and 18 million tonnes of copper.

Bristow’s era also changed Barrick’s financial posture. After a decade defined by debt and overreach, the company emerged with a cleaner balance sheet, a more focused portfolio, and a clearer operating philosophy. During his tenure, Barrick integrated Randgold, optimized its asset base, and reduced net debt by about $4 billion.

Operating performance followed. In 2024, Barrick reported net earnings of $2.14 billion, up 69%. Adjusted net earnings rose 51% to $2.21 billion. Attributable EBITDA climbed 30% to $5.19 billion—its strongest in more than a decade.

And then there’s copper. Barrick’s exposure through projects like Reko Diq and Lumwana is a direct bet on electrification and long-term industrial demand. In 2024, attributable copper mineral reserves jumped sharply year over year—up 224% to 18 million tonnes at a higher grade of 0.45%, from 5.6 million tonnes at 0.39% in 2023. The story Barrick wants the market to believe is simple: this is no longer just a gold miner riding a single cycle. It’s becoming a gold-and-copper platform.

The Bear Case

The biggest risk isn’t geological. It’s jurisdictional.

A meaningful share of Barrick’s most important assets sit in countries where political instability, resource nationalism, and regulatory shifts aren’t tail risks—they’re part of the operating environment. And in 2025, that risk stopped being theoretical.

Barrick’s mine in Mali, one of its largest gold assets in Africa, was taken over by the country’s military government over alleged non-payment of taxes. Barrick took a $1 billion write-off tied to the dispute. The episode was a reminder of mining’s hardest truth: even when you believe you’re acting as a partner, the other side can still change the rules. Bristow said the company remained open to constructive engagement with Mali’s government, and he acknowledged the overhang on the stock: “While ongoing issues in Mali remain an investor concern, which have overly weighed on the share price, Barrick's fundamental value proposition has never been stronger.”

Then there’s Reko Diq, which comes with its own kind of risk. Building a roughly $7 billion mine in remote, insurgency-affected Balochistan is the definition of execution complexity. Delays, cost inflation, security issues, or a shift in political will in Pakistan could materially alter the economics.

Those concerns have started to show up in the valuation debate. Reuters reported this month that some board members and shareholders worry the company’s exposure to Pakistan and Africa may be weighing on Barrick’s multiple versus peers with more of their production in North America. Barrick’s board has considered more dramatic options—splitting the portfolio, and even the possibility of selling Reko Diq and its African holdings outright.

That pressure crystallized on December 1, 2025. Barrick announced that its board had authorized management to evaluate an initial public offering of a new subsidiary to hold its premier North American gold assets. The proposed “NewCo” would include Barrick’s interests in Nevada Gold Mines, the Pueblo Viejo mine in the Dominican Republic, and its wholly owned Fourmile discovery in Nevada. Barrick said it would offer only a minority stake and retain control. The timing mattered: record gold prices, and a market hungry to separate “safe-jurisdiction” cash flow from higher-risk optionality in Africa and Pakistan.

Finally, there’s leadership. On September 29, 2025, Bristow unexpectedly resigned as CEO. Barrick appointed long-time executive Mark Hill as Group Chief Operating Officer and Interim President & CEO, while launching a global search for a permanent successor.

Bristow was the architect of the modern Barrick—operational discipline, portfolio focus, and a partnership posture with host governments, alongside that ~$4 billion net-debt reduction. His sudden departure created a new kind of uncertainty: not whether Barrick has great assets, but whether it can keep behaving like the company Bristow built. The next CEO will determine whether Barrick stays operations-first—or drifts back toward the old instinct to solve hard problems with financial structure.

Regulatory and Accounting Considerations

Investors should also keep a few practical overhangs in mind:

- Mali operations: Currently suspended, with a $1 billion write-down already taken. The timeline for resolution remains uncertain.

- Reko Diq execution: A roughly $7 billion build with production targeted for 2028 means years of major capital deployment and execution risk.

- Reserve accounting: Mineral reserves are estimates based on geological modeling and commodity price assumptions, and they can change materially with new information or price moves.

Conclusion: The Search for Tier One Continues

Is Barrick a technology company? Obviously not. But at its best, it may be the most sophisticated dirt-moving operation on Earth—one that tries to fuse world-class geology with operational discipline, financial strength, and the ability to navigate geopolitics without losing the plot.

That’s the throughline of the whole saga. Peter Munk proved that financial sophistication could build an empire. The lost decade proved that financial engineering alone can’t sustain one. And Mark Bristow’s tenure proved that returning to the fundamentals—good rocks, tough capital discipline, and real partnership with host communities and governments—can pull a company back from the edge.

Today, Barrick is a leading global mining, exploration, and development company. It holds one of the industry’s largest portfolios of long-life gold and copper assets, including six Tier One gold mines. Its operations and projects span 18 countries and five continents, and it’s also the largest gold producer in the United States.

But the ending isn’t written, because the next phase is a set of choices. Who leads after Bristow? Does Barrick separate its North American crown jewels from the higher-risk parts of the portfolio? Can Reko Diq be built on time and on budget? Can Mali be resolved? The answers will decide whether the turnaround becomes an enduring operating model—or just a chapter between crises.

For investors, the proposition is straightforward: exposure to gold and copper through top-tier assets run with discipline, paired with jurisdictional risk that has to be respected. “Tier One” is a useful filter, but geology is only half the equation. The other half is execution—and in mining, execution is never guaranteed.

From a Hungarian refugee fleeing the Nazis, to the mountains of Nevada, to the deserts of Pakistan, Barrick’s journey captures the central truth of the industry: moving rock is a business that demands financial acumen, geological insight, operational excellence, and human judgment all at once. Companies that can hold all four together create extraordinary value. Companies that drop even one learn the lesson the hard way.

The search for Tier One continues.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music