AZZ Inc.: From Galvanizing Steel to Industrial Infrastructure Giant

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture a 60,000-pound steel coil, freshly rolled and gleaming, about to disappear into a bath of molten zinc, heated past 800 degrees Fahrenheit. In that instant—when raw steel meets old-world metallurgy—something simple happens with enormous consequences: the metal gets a protective skin that can outlast decades of weather, salt, and abuse. More often than you’d think, the company doing that work is AZZ Inc.

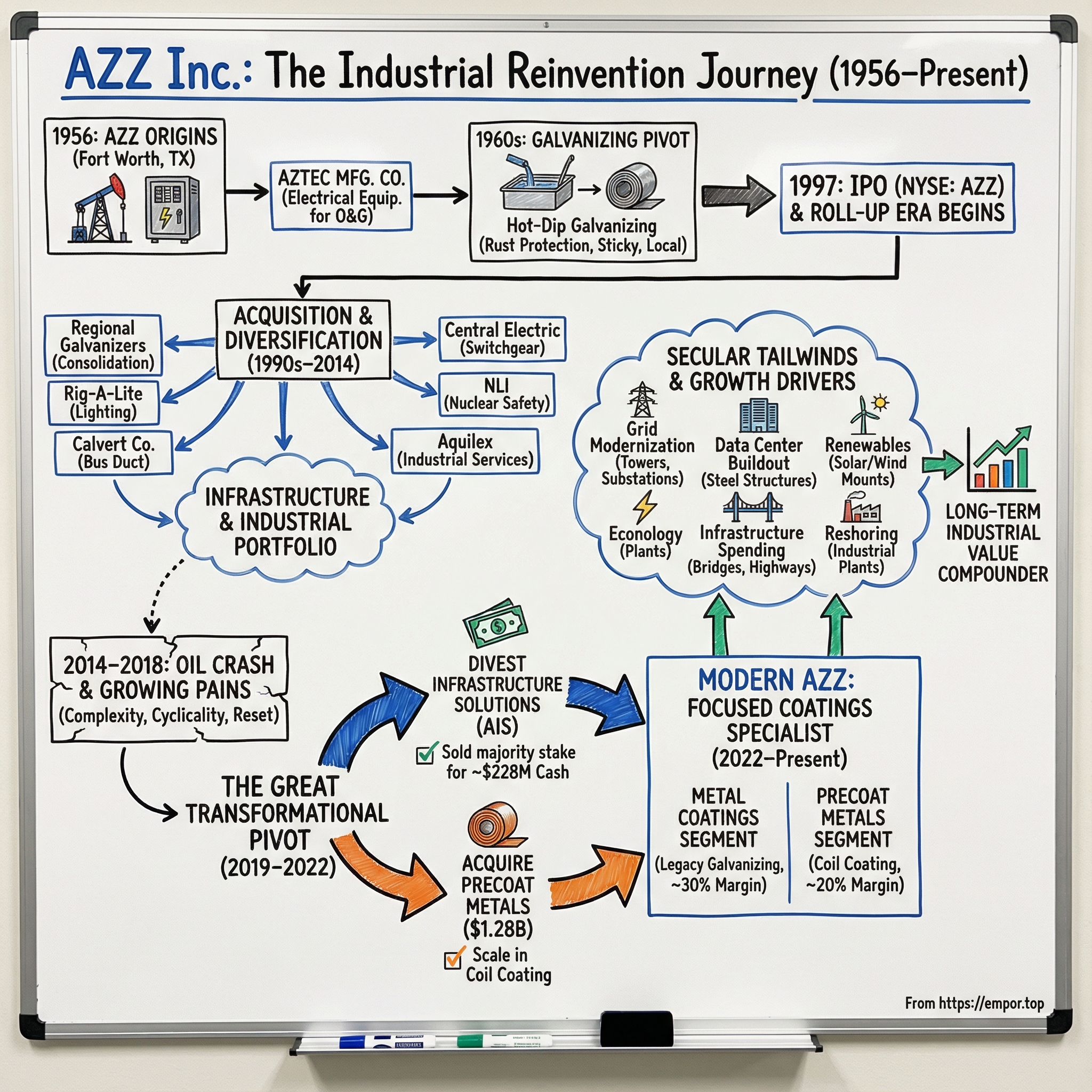

This is the story of a Texas company founded in 1956 that spent decades in the decidedly unglamorous business of fighting rust—and then used that foundation to reinvent itself again and again. AZZ grew into North America’s largest hot-dip galvanizer and a major player in coil coating solutions. It’s a name most people have never heard, but its work is everywhere: in highway guardrails, transmission towers, refinery pipe racks, industrial plants, commercial buildings—anywhere steel is expected to survive in the real world.

The idea at the heart of this episode is straightforward: some of the best business stories live far from the spotlight. Industrial B2B companies like AZZ don’t win mindshare on social media, but they quietly win the contracts that keep modern infrastructure standing and the grid running. And AZZ, in particular, is a masterclass in strategic evolution—knowing when to scale a core business, when to pivot into adjacent markets, and when to make the hardest call of all: walking away from what made you successful in the first place.

By fiscal 2024, AZZ had reached record consolidated sales of $1.32 billion. That didn’t happen because of a single breakthrough product or a viral moment. It happened through a long chain of moves: roll-up acquisitions, big bets into electrical and industrial infrastructure, painful integration lessons, and then a portfolio reshaping that changed what AZZ fundamentally was.

Here’s how we’re going to tell it. We’ll start with galvanizing—what it is, why it’s such a sticky, local business, and why it was perfect for consolidation. Then we’ll follow AZZ through its acquisition-heavy roll-up era, into its push toward electrical infrastructure, through the growing pains of the mid-2010s, and into the transformation that redefined the company in the early 2020s. Along the way, we’ll pressure-test the strategy with frameworks like Porter’s Five Forces and Hamilton’s Seven Powers, lay out the bull and bear cases, and pull out the lessons that apply well beyond steel and zinc.

The themes are clear: the art—and risk—of the roll-up, the courage it takes to reinvent a legacy business, and the advantage of positioning yourself behind secular infrastructure tailwinds that don’t show up overnight, but can last for decades.

Let’s begin.

II. The Galvanizing Business & AZZ's Origins (1956–1990s)

To understand AZZ, you first have to understand galvanizing—and why it can produce one of the stickiest business models in industrial services.

Hot-dip galvanizing is beautifully simple: take fabricated steel and dip it into molten zinc, typically around 840°F. The zinc bonds to the steel and forms a protective layer that can fend off corrosion for decades—often 50 years or more. The process dates back to 1836, when a French chemist named Stanislas Sorel helped pioneer the technique. Nearly two centuries later, the fundamentals are basically the same. What’s changed is the scale. And scale is where the business starts to compound.

Corrosion is a slow, relentless tax on the economy. The Federal Highway Administration has estimated the annual U.S. cost in the hundreds of billions of dollars. Bridges, guardrails, transmission towers, industrial facilities—left unprotected, steel doesn’t just age. It fails. Galvanizing is one of the simplest, most proven ways to push that failure far into the future, and that reliability creates unusually attractive economics.

Here’s why: galvanizing is local by nature. Steel fabricators typically can’t justify shipping bulky, awkward steel components hundreds of miles just to get coated; freight costs and logistics friction erase the savings. So demand tends to cluster around plants, and plants tend to dominate their radius. If you’re the only galvanizer within a practical distance, you don’t need fancy contracts to keep customers. The switching cost is physics.

AZZ’s story starts in Fort Worth in 1956, right in the middle of the post-war industrial boom. R. G. Anderson founded Aztec Manufacturing Co. as an electrical equipment manufacturer serving the oil and gas industry. In 1950s Texas, that was plenty of opportunity: the Permian Basin was surging, pipelines were expanding, and refineries along the Gulf Coast needed the electrical guts that kept operations running—switchgear, enclosures, control panels. It was real work, for real customers, in a growing market.

But the move that shaped the next several decades came in the 1960s, when Aztec diversified into hot-dip galvanizing. Electrical equipment manufacturing could be project-based and uneven. Galvanizing, by contrast, had a steadier rhythm: as long as people kept building with steel outdoors, they’d need protection from rust. The company began building galvanizing plants across the Southwest, and each new facility wasn’t just capacity—it was a local fortress.

Through the 1970s and 1980s, that footprint expanded with new facilities in Jackson, Mississippi (1970), Houston, Texas (1975), Waskom, Texas (1982), and Moss Point, Mississippi (1985). The pattern was consistent: follow infrastructure growth across the Gulf States and put plants where regional demand would naturally concentrate. Every site widened the network, letting the company serve more fabricators without losing the core advantage of proximity.

In 1973, the company changed its name to AZZ Incorporated. It wasn’t just a rebrand. It signaled that AZZ was becoming something broader than a small manufacturing outfit—more like a platform, built around industrial services with long staying power.

Then came the financing catalyst. On March 20, 1997, AZZ went public on the NYSE. The IPO mattered because it gave AZZ access to public capital at exactly the right time. Galvanizing was fragmented, capital-intensive, and protected by permitting and environmental complexity—an industry where consolidation could work. AZZ now had a currency and a balance sheet to start buying, building, and stitching together a bigger footprint.

And that sets up the key takeaway from this era: galvanizing is a great business precisely because it’s not flashy. The underlying technology is stable. Substitutes are limited. The work is mission-critical. And local scale can look an awful lot like a moat. This “boring” foundation is what would later bankroll AZZ’s much bigger reinvention.

III. The Roll-Up Era: Building an Empire Through Acquisition (1990s–2000s)

In the 1990s, galvanizing looked like a consolidation dream. The industry was huge in aggregate, but broken into pieces: dozens of regional operators, most with just one or two plants. They were often solid, cash-generating businesses—but too small to build national reach or meaningfully lower costs through scale.

AZZ’s leadership saw what would later become a familiar private equity idea: build a platform. Buy a cluster of similar businesses, keep what makes them work locally, centralize what doesn’t need to be local, and let the combined company become more valuable than the parts ever could on their own.

Galvanizing was unusually well-suited to that playbook.

It was capital-intensive—expensive to build a plant, but once it’s running, it can throw off steady cash for years. It was heavily regulated, with environmental compliance creating real friction for new entrants. And it was relationship-driven: fabricators didn’t like switching galvanizers unless they had to, because quality, turnaround time, and trust matter when the steel you’re coating is headed for critical infrastructure.

By this point, AZZ already had a meaningful base—eight galvanizing operations—and it was public, listed on the NYSE under “AZZ.” That mattered. The IPO didn’t just raise money; it gave AZZ a currency and a balance sheet to accelerate acquisitions.

Then came the kind of deal that turns a regional leader into a national one. AZZ acquired North American Galvanizing Company, which operated 11 facilities across eight states. In one move, AZZ massively widened its footprint, pushing its galvanizing locations to 36 and cementing its position as the largest galvanizer in North America. The logic was classic roll-up math: add geographic density, reduce duplicated overhead, and buy zinc and other inputs with far more leverage.

From there, the approach became a repeatable machine. AZZ targeted family-owned and sponsor-backed galvanizers, bought them at reasonable prices, kept local teams close to customers, and pulled administrative functions into a larger operating platform. Every acquisition made the network more valuable—especially for customers who wanted consistent service and quality across multiple regions.

But AZZ wasn’t trying to become only a bigger galvanizer. It also started reaching into adjacent industrial categories that sold into the same kinds of customers.

It acquired Rig-A-Lite Inc., a manufacturer of industrial lighting designed for oil, gas, and other hazardous environments. It acquired The Calvert Company, bringing in electrical bus duct system design and installation. Then it combined Atkinson, Calvert, and Rig-A-Lite into what it called the Electrical Products Group—a clear signal that a second business line was becoming real. Over time, AZZ added fabricated enclosure systems, acquired a CGIT business to participate in long-distance power transmission, and, with the acquisition of Central Electric Manufacturing, expanded into metal-clad switchgear.

The picture by the early 2000s was very different from the company that started with molten zinc baths and regional plants. AZZ still had a core metal coatings franchise, competing with both national-scale providers and smaller local operators—names like Valmont Industries and Voestalpine show up in the competitive set. The broader galvanizing market remained fragmented, but AZZ had become the consolidator-in-chief, with an estimated 25–30% share and a footprint stretching coast to coast.

And crucially, it had done something else: it had built a second engine. Galvanizing was the foundation—local, sticky, and cash-generative. The Electrical Products Group was the new frontier—more technical, more project-driven, and potentially much larger.

The big takeaway from this era is that roll-ups can be incredibly powerful in the right conditions: fragmented ownership, local market dynamics, and limited technology disruption. But they come with a hidden requirement that only gets harder as you scale—disciplined integration. Buy too fast and you lose control. Buy well, integrate smart, and the advantages compound.

IV. The Pivot: Electrical & Industrial Segment Emerges (2000s–2010)

The 2000s were when AZZ started to look less like “a galvanizer that also happens to sell electrical gear,” and more like a company deliberately assembling an infrastructure toolkit.

The strategic logic was simple and, in hindsight, obvious: America’s electrical system was getting old. Much of the grid had been built in the mid-20th century. Years of underinvestment meant utilities were staring at a growing list of upgrades—substations, transmission capacity, distribution modernization. Whoever could supply the equipment behind those projects would have a seat at the table for decades.

AZZ leaned into that opportunity by expanding what its electrical portfolio could actually do. A key step was the acquisition of Central Electric Manufacturing in Fulton, Missouri—founded, fittingly, in 1956, the same year AZZ began. Central Electric brought metal-clad switchgear and power distribution centers into the lineup. This isn’t “nice-to-have” hardware. Switchgear is the protective gatekeeper of power distribution; when it fails, facilities go dark.

By this point, AZZ’s electrical and industrial offering had become broad and practical: custom switchgear, electrical enclosures, medium- and high-voltage bus duct, explosion-proof and hazardous-duty lighting, tubular products, and engineering support for large, multi-national customers. In plain terms, AZZ was building the ability to show up across the power generation and distribution value chain—substations, industrial plants, hazardous environments, control systems—wherever electricity needed to be moved safely and reliably.

What changed wasn’t just the product catalog. It was the business model.

Galvanizing was a service business with a steady rhythm: customers brought in fabricated steel, AZZ coated it, and shipped it back out. Electrical manufacturing was different. It meant designing, engineering, and fabricating custom solutions, often tied to longer projects and longer sales cycles. The margin profile was different. The rhythm was different. But the customers—utilities, industrial operators, energy companies—overlapped more than you’d expect. AZZ was learning how to sell deeper into the same ecosystem.

This era also solidified the structure that would define AZZ for the next decade: Metal Coatings on one side, and Electrical and Industrial Products on the other. Management’s bet was that the combination was worth more than two separate businesses—shared relationships, complementary market cycles, and a more diversified revenue base.

Of course, the integration wasn’t frictionless. Galvanizing plants were decentralized by nature—local management, local culture, fast turnaround. Electrical equipment manufacturing demanded centralized engineering, tighter project management, and patience through longer lead times. Folding those worlds into one company tested AZZ’s organizational muscle in a way simple plant roll-ups hadn’t.

But by the end of the 2000s, the direction was clear. AZZ had placed itself at the crossroads of infrastructure renewal and energy-sector growth—and it was setting up for a much bigger leap.

V. The Inflection Point: Doubling Down on Infrastructure (2011–2014)

The early 2010s were AZZ at its most aggressive—and most ambitious. Management wasn’t just adding bolt-on acquisitions anymore. It was making a concentrated bet that America’s infrastructure backlog, especially in power generation and the grid, would translate into decades of demand.

One move in particular signaled how serious that bet was: nuclear.

In June 2012, AZZ agreed to acquire substantially all of the assets of Nuclear Logistics, Inc. (NLI), a Fort Worth-based provider of electrical and mechanical equipment and services designed to enhance the safety of nuclear facilities. AZZ described NLI as the largest third-party supplier in its niche—work that sits in a rare category where “good enough” doesn’t exist. The value comes from regulatory know-how, certifications, and hard-earned credibility inside an industry built on redundancy and risk management.

The context mattered. After the Fukushima disaster in 2011, the nuclear industry faced a new wave of scrutiny, and with it, a renewed urgency around safety upgrades. AZZ was buying into a market where the barriers to entry are not just capital and expertise, but trust.

The terms reflected the size of the swing: $80 million in cash, the assumption of current liabilities, and $4.8 million of notes payable, plus a potential additional payment of up to $20 million tied to future performance. For the first full year under AZZ, NLI revenues were expected to land in the $70–$80 million range, and the acquired backlog was approximately $75 million.

Then AZZ doubled down again—this time with an even bigger deal, and with a broader definition of “infrastructure.”

In 2013, AZZ acquired Aquilex SRO for $250 million in cash, its largest acquisition to date. Aquilex had been founded in 1978 to provide machine welding services for nuclear units and nuclear plant maintenance, but over time it had expanded into a portfolio of “life extension” services across industries that run on uptime: nuclear, fossil and waste-to-energy, refining, chemical processing, pulp and paper, and general industrial.

Embedded inside Aquilex was Welding Services Inc. (WSI), a specialty welding contractor focused on critical component assets. WSI’s work wasn’t commodity welding—it was automated welding solutions, structural weld overlay, and weld cladding for planned outages and emergency responses, the kind of capability customers call when failure is expensive and time is unforgiving.

The mix of Aquilex’s business underscored why it fit the moment: roughly a third of its revenue came from nuclear, a third from fossil and waste-to-energy, and a third from refining, petrochemical, and general industrial markets. For its first full year under AZZ, Aquilex revenues were expected to be in the $225–$250 million range.

Put the nuclear foothold (NLI) together with the industrial services expansion (Aquilex and WSI), and the strategy snaps into focus. AZZ was trying to become more than a manufacturer or a coatings provider. It was positioning itself as a partner that could help keep the country’s hardest-working infrastructure operating safely, reliably, and longer than originally planned.

And even while AZZ pushed into these higher-complexity, project-driven businesses, it didn’t stop feeding the original engine. The galvanizing business kept throwing off cash—and AZZ kept expanding the network. During this period, AZZ acquired six galvanizing locations of U.S. Galvanizing LLC from Trinity Industries, plus one location from Olsen Industries, reinforcing the local footprint that had always made the coatings side so sticky.

By fiscal 2014, AZZ was a meaningfully larger—and far more complicated—company than it had been just five years earlier. The Electrical and Industrial Products segment now rivaled Metal Coatings in scale. The company had a real presence across nuclear, fossil, refining, petrochemical, and general industrial markets. It was the most diversified AZZ had ever been.

But that diversification came with a price: more moving parts, harder integration, and greater exposure to cyclical end markets—right before those markets were about to face a historic shock.

VI. Growing Pains & Strategic Reset (2014–2018)

Then the floor fell out.

Starting in mid-2014, oil prices began a collapse that would reshape the industrial economy. Over roughly eighteen months, crude went from well over $100 a barrel to the low $30s—one of the steepest, longest drops the market had seen since World War II. Analysts pointed to a familiar culprit: a surge in supply, powered in large part by the U.S. shale boom.

For AZZ, the timing was brutal.

The company had just spent the prior few years buying its way deeper into energy-adjacent services—welding, outage work, refinery and petrochemical maintenance, and specialized capabilities that thrive when customers are investing. But when oil crashes, the first reflex across the patch is the same: freeze spending. Capital budgets get cut. Projects get pushed. Orders vanish. And the ripple effects don’t stay neatly contained in “oil and gas.” Refining and petrochemical customers—meaningful end markets for AZZ’s welding services—tightened budgets too.

The pain didn’t hit just one corner of the portfolio. Nuclear services ran into headwinds as low natural gas prices made new nuclear projects harder to justify. The broader industrial segment had to fight a two-front war at once: weakening demand, and the execution complexity that comes with large, project-driven work. What looked like diversification on a slide deck started to feel, in practice, like a set of correlated cyclical bets.

And inside the company, the strain showed.

AZZ had grown quickly, acquired heavily, and ended up operating a more complex set of businesses than its systems and processes were ready to handle. When revenue softens, complexity gets expensive fast. Fixed costs don’t come out overnight. Margins compress. Integration work that felt “good enough” in a rising market suddenly becomes the difference between stability and a spiral.

One thing did hold: the legacy coatings engine.

Even through the turbulence, AZZ’s galvanizing business stayed comparatively solid. Construction and infrastructure demand didn’t swing with oil prices in the same way, and the coatings segment continued to provide reliable cash flow. AZZ had been profitable for decades, and this period reinforced a hard truth: the coatings side was still doing what it had always done. The electrical and industrial side was where the instability lived.

A leadership transition helped force the reset. Tom E. Ferguson became President and CEO, bringing a different orientation to the job—more operational discipline, more cultural alignment, and a sharper focus on what, exactly, AZZ should be great at. He talked openly about building leaders and accountability, arguing that results follow from people, direction, and execution—not from obsessing over the scoreboard.

That philosophy mattered because the next step wasn’t “buy more.” It was simplify.

AZZ began divesting non-core assets and narrowing its focus to businesses where it believed it had real competitive advantage. One clear example came later, as the company continued that strategic review: AZZ entered into an agreement to divest its Nuclear Logistics LLC operating business unit to Paragon Energy Solutions. The company framed it plainly—NLI’s performance had improved, but capital would be better redeployed into the metal coatings segment, where AZZ saw stronger growth opportunities.

That divestiture, announced in 2020, became a public marker of where the reset was heading. As Ferguson put it, it aligned with AZZ’s desire to focus on its core businesses and markets, while staying active in pursuing coatings acquisitions and investing in the foundation.

The lesson from 2014 to 2018 was expensive but clarifying. Diversification doesn’t automatically reduce risk if your end markets move together. Integration discipline matters more than acquisition volume. And sometimes the most strategic thing you can do—especially after a bout of overreach—is to simplify, refocus, and rebuild from the parts of the business that still behave the way you thought they would.

VII. The Great Transformation: Portfolio Reshaping (2019–2022)

From 2019 to 2022, AZZ made the most dramatic strategic pivot in its history: it didn’t just tweak the portfolio around the edges. It rewrote the company’s identity.

COVID threw industrial markets into a blender. Supply chains broke. Projects slipped. Lead times stretched. And in that kind of uncertainty, strategy stops being theoretical. You either decide what you are, or the market decides for you.

For AZZ, the pandemic collided with a broader strategic review that had been building since the mid-2010s reset. Management concluded that the two sides of the house—Metal Coatings and what it called Infrastructure Solutions—weren’t complementary anymore. They behaved differently. They needed different kinds of capital. They had different growth and margin profiles. And trying to optimize both under one roof was, in their view, holding each back.

So AZZ chose a direction: double down on coatings.

AZZ Inc. and Sequa Corporation jointly announced that they had entered into a definitive agreement for AZZ to acquire Sequa’s Precoat Metals business division for approximately $1.28 billion. When adjusted for the net present value of approximately $150 million of expected net tax benefits, the net purchase price was approximately $1.13 billion, representing approximately 8.2x Precoat’s adjusted EBITDA for the twelve months ended December 31, 2021.

On March 7, 2022, AZZ announced it had completed that transformative acquisition—by far the largest deal in the company’s history. Precoat specializes in applying protective and decorative coatings, plus related value-added services, for steel and aluminum coil that ends up in construction, appliances, HVAC, containers, transportation, and other end markets. It brought roughly 1,100 employees, and a network of 13 manufacturing facilities with 15 coating lines and 17 value-added processing lines. For the twelve months ended December 31, 2021, Precoat generated approximately $700 million of revenue and approximately $137 million of adjusted EBITDA.

Tom Ferguson, Chief Executive Officer of AZZ, said, "Today we welcome the 1,100 employees of Precoat to the AZZ family and begin the work of swiftly integrating Precoat into AZZ while leveraging the opportunities this acquisition creates. As I have previously stated, this acquisition significantly broadens our metal coatings offering, creating unrivaled scale and breadth of solutions in both the prepainted and post-fabrication coatings markets. We believe the coil coating market will provide sustainable future growth for AZZ, and we are excited to add a talented leadership team that shares similar values as well as employee and customer focus as we do at AZZ. This acquisition is consistent with our previously communicated strategy prioritizing North American coatings targets with strong strategic fit that are accretive within the first year of operation."

In other words: AZZ wasn’t trying to be a diversified industrial holding company anymore. It wanted to be the coatings leader—at scale, across multiple coating categories.

But the Precoat acquisition was only half the story. To pay for that focus, AZZ also had to simplify the other side of the portfolio.

At the same time, AZZ moved to divest its Infrastructure Solutions segment.

AZZ Inc. and Fernweh Group LLC jointly announced that, as of Friday evening, September 30, 2022, they completed the previously announced transaction in which AZZ contributed its AZZ Infrastructure Solutions Segment to AIS Investment Holdings LLC and sold a 60% interest in the AIS JV to Fernweh at an implied enterprise value of $300 million. AZZ anticipated approximately $228 million of cash proceeds, subject to customary purchase price adjustments, and stated it would use $210 million to pay down its Term Loan B and the balance to pay on its Revolving Credit Facility.

AIS was described as a leading provider of specialized products and solutions for industrial and electrical applications—custom switchgear, electrical enclosures, medium- and high-voltage bus duct, and explosion-proof and hazardous-duty lighting. It also focused on life-cycle extension for power generation, refining, and industrial infrastructure through automated weld overlay solutions designed to mitigate corrosion and erosion. The business had approximately 1,323 employees, operated through 20 facilities globally, and for fiscal year 2022, ended February 28, 2022, generated approximately $375 million of sales.

Put together, these moves amounted to a portfolio flip. AZZ spent $1.28 billion to buy Precoat and took in approximately $228 million in cash proceeds from selling a controlling stake in Infrastructure Solutions. The net investment was substantial, but the point wasn’t the arithmetic. The point was what AZZ would be when the dust settled.

Tom Ferguson, Chief Executive Officer of AZZ, commented, "The agreement to divest a controlling stake in AIS to Fernweh represents the continued transition of AZZ into a focused industry leading provider of metal coating and galvanizing solutions."

This is what strategic courage looks like in industrial America: selling a business line that had become central to the “new” AZZ in the 2000s and 2010s, and concentrating the company around coatings.

And none of it happens without financing.

In connection with entry into the Securities Purchase Agreement, on March 7, 2022, the Company also entered into a commitment letter with Citigroup Global Markets Inc. and Wells Fargo Securities, LLC. Under the Debt Commitment Letter, the Lenders committed to provide the Company with $1,825,000,000 of debt financing, consisting of a senior secured term loan credit facility of $1,525,000,000 and a Revolving Facility of $300,000,000.

It was an aggressive capital structure—real debt to fund a real bet—with the implied promise that the new AZZ would generate enough cash flow to bring leverage back down.

By October 2022, the transformation was effectively complete. AZZ emerged as a pure-play metal coatings company: North America’s largest hot-dip galvanizer, and a leading independent coil coater. After decades of building outward—into electrical products, then into industrial services, then into infrastructure solutions—the company had chosen focus over breadth, and returned to a thesis built around coating steel for the long haul.

VIII. Modern Era: Focused Strategy & Growth Drivers (2022–Present)

With the portfolio flip complete, AZZ entered the modern era as a much more focused company: a coatings specialist at industrial scale.

That focus shows up clearly in the company’s more recent results. In its Fiscal Year 2025 Annual Report on Form 10-K (for the year ended February 28, 2025), AZZ framed the year as a continuation of the post-transformation momentum. CEO Tom Ferguson said fiscal 2025 delivered record full-year results, with sales growth despite significant weather impacts late in the year. He highlighted record performance in both segments, with the Metal Coatings business producing high EBITDA margins and Precoat Metals delivering strong profitability at scale.

Today’s AZZ operates through two segments, both built around the same core idea: protect metal, extend its life, and make it perform better in the real world.

AZZ describes itself as the leading independent provider of hot-dip galvanizing and coil coating solutions across construction, industrial, transportation, consumer, and electrical markets. It’s not a flashy mission, but it’s foundational: the company’s coatings help buildings last longer, infrastructure resist corrosion, and metal products hold up under years of exposure and wear.

The Metal Coatings segment is the heritage engine—the hot-dip galvanizing network AZZ spent decades building and consolidating. With more than 60 locations across the U.S. and Canada, it’s the largest after-fabrication galvanizer in North America. This is the part of AZZ that “protects the backbone”: transmission towers, highway and bridge components, industrial structures—anything steel that has to live outside and survive. It’s also the segment that has historically produced the most attractive economics for the company, with EBITDA margins around 30% and resilient demand.

The Precoat Metals segment is the newer pillar—pre-painted coil coating at national scale. Instead of coating finished fabricated parts, Precoat applies protective and decorative coatings to steel and aluminum coil before fabrication. Headquartered in St. Louis, Missouri, Precoat serves end markets like construction, appliances, HVAC, containers, and transportation. It’s a different workflow, different customers, and different operating cadence than batch galvanizing—but it fits the same thesis: coatings as a critical, value-added layer in the supply chain. AZZ has pointed to EBITDA margins approaching 20% for this business.

Financially, the post-transformation story has been about stronger earnings, cash generation, and a steady push to de-risk the balance sheet. AZZ reported adjusted EBITDA of $333.6 million in fiscal 2025, cash from operations of $244.5 million, and meaningful debt reduction over the year, bringing net leverage down to under 3x. A year earlier, the company described fiscal 2024 as pivotal—its first full fiscal year with Precoat—highlighting record sales in both segments and the company’s 37th consecutive year of profitability from continuing operations.

But the numbers are only half the point. The more important question is: what’s driving demand for a focused coatings company like this?

The tailwinds are big, and they’re long-duration.

Grid modernization is a generational upgrade cycle. The U.S. electrical grid was largely built in the mid-20th century, and it’s being asked to do far more than it was designed for—renewables integration, rising electrification, and expanded transmission and distribution. Galvanized steel sits underneath that work in transmission towers, substation structures, and other outdoor electrical infrastructure.

Data center construction is another accelerant. As AI and cloud computing expand, the physical footprint of computing expands with them—more buildings, more electrical infrastructure, more steel that has to be protected for the long run. A 2024 Electric Power Research Institute report noted that Arizona data centers could more than double their energy usage by 2030, potentially reaching a meaningful share of the state’s total electricity consumption. Arizona is a vivid example, but the buildout is national—and corrosion protection rides along with it.

Renewable energy deployment pulls demand forward too. Wind and solar aren’t just generation assets; they’re steel-heavy projects with foundations, mounting structures, and the transmission buildout required to connect generation to load centers.

Infrastructure spending adds another layer. Federal funding under the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act has helped unlock bridge, highway, and public works projects—exactly the kind of non-building construction that consumes large volumes of galvanized steel.

And reshoring and manufacturing growth create steady demand for industrial facilities and equipment—more plants, more structures, more coated steel moving through the system.

AZZ has been explicit that it believes it’s well positioned for a rebound in end markets and for the secular tailwinds in infrastructure, renewables, reshoring, and the shift toward more environmentally friendly pre-painted steel and aluminum. The company has pointed to increased volumes in metal coatings supported by infrastructure spending across construction, bridge and highway work, transmission and distribution, and renewables.

That operating momentum has translated into cash—and cash is what makes the strategy sustainable. AZZ reported generating significant operating cash in fiscal 2025 through improved earnings and disciplined working capital management. It used that cash the way you’d expect from a company still digesting a major acquisition: pay down debt, keep returning capital to shareholders through dividends, and reinvest in organic growth. Capital spending included investment in a greenfield facility in Washington, Missouri.

That’s the modern AZZ playbook: delever, invest, expand selectively. Not the old roll-up machine across unrelated industrial categories—just a focused push to deepen leadership in metal coatings.

For investors, that raises the only question that matters now: with the transformation done and the tailwinds strengthening, does AZZ’s competitive position and growth runway justify what the market is pricing in today?

IX. Playbook: Business & Strategic Lessons

AZZ’s seven-decade run is a reminder that the most durable businesses don’t always come from flashy innovation. They come from picking the right market structure, compounding operational know-how, and having the nerve to change course when the old map stops matching the terrain.

The Roll-Up Playbook: When It Works, When It Doesn't

AZZ’s galvanizing roll-up worked because galvanizing is almost engineered for consolidation: it’s fragmented, local by necessity, hard to greenfield, and relatively stable technologically. If you can buy well-run plants, keep the local relationships intact, and layer in smarter purchasing and shared overhead, you can create real value—not just bigger revenue.

Where AZZ ran into trouble was assuming the same playbook would translate cleanly into electrical and industrial services. Those businesses can be more project-driven, more execution-sensitive, and tougher to integrate. The risk isn’t that the assets are bad. It’s that the complexity arrives faster than the organization’s ability to absorb it.

The key insight: roll-ups win when geography and structure do a lot of the heavy lifting, and when integration makes the combined company meaningfully better than the standalones. They break when acquisition pace substitutes for operational control, or when integration demands outstrip what management systems can handle.

Strategic Pivots: Knowing When to Walk Away

AZZ’s choice to divest its Infrastructure Solutions segment meant walking away from a major part of what “modern AZZ” had become in the 2000s and 2010s—and from businesses tied to its roots. That’s not just a portfolio decision. That’s an identity decision.

Those operations had strong customer relationships, talented teams, and real scale. But management concluded that trying to be great at two fundamentally different models at once was diluting focus and returns.

The lesson: sunk costs don’t get a vote. Strategy isn’t about protecting the past; it’s about putting capital and attention where they can earn the best returns from here.

Mission-Critical Positioning

What AZZ sells today isn’t optional. It sits in the category of “you don’t notice it until it fails.” When corrosion protection is done wrong, bridges and infrastructure can become unsafe. When coatings fail in building and industrial systems, the consequences can be costly, disruptive, and sometimes dangerous.

That mission-critical role changes the conversation with customers. It can create stickiness and pricing power that commodity suppliers struggle to match, because the buying decision isn’t just about cost. It’s about reliability, qualification, quality consistency, and confidence earned over time.

For investors, the signals are straightforward: failure carries real consequences; switching involves more than signing a new contract; and purchasing includes technical scrutiny, not just low-bid selection.

Riding Macro Waves

AZZ didn’t invent the forces reshaping demand—grid upgrades, data center buildouts, renewables, infrastructure spending, and reshoring. But it did make a series of decisions that determined whether those waves would lift the company or pass it by.

The lesson: execution matters, but positioning matters too. A company that’s merely good, aligned with powerful long-duration tailwinds, can outperform a company that’s excellent—but pointed at shrinking demand.

Operational Excellence in Industrial Businesses

In businesses like these, competitive advantage often looks like competence, repeated at scale: tight plant operations, consistent quality, reliable turnaround times, and the quiet discipline of doing what you said you’d do.

AZZ’s story is a case study in that kind of compounding. No glamour. No viral product moments. Just the steady accumulation of process, trust, and execution that customers come to depend on—and competitors have a hard time replicating.

X. Analysis: Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Competitive Rivalry: Moderate

Metal coatings is competitive, but it’s not a winner-take-all knife fight. In AZZ’s world, rivalry looks less like a national brand war and more like a map—who has a plant close enough to matter, who can turn jobs around quickly, and who has earned the trust of local fabricators.

In hot-dip galvanizing, AZZ competes with a mix of large, scaled players and plenty of smaller regional operators. Names like Valmont Industries (VMI) and Voestalpine show up in the competitive set, but the market is still fragmented. AZZ’s estimated 25–30% share matters because scale helps—purchasing leverage, shared overhead, best practices—but the real battleground stays local.

That local dynamic tempers pure price competition. Switching isn’t frictionless, because quality consistency, turnaround time, and relationships matter when the steel is headed for bridges, transmission towers, and industrial facilities. In a business where the customer is shipping heavy, awkward steel, proximity and reliability often beat a slightly lower quote.

Threat of New Entrants: Low

Starting a new galvanizing operation from scratch is hard in all the ways that count. It takes meaningful capital to build the plant, and environmental permitting adds time, cost, and uncertainty. The broader trend toward stricter environmental compliance raises the bar further—an advantage for incumbents that already have facilities, systems, and experience operating within regulatory constraints.

Then there’s the customer side. Relationships and qualification matter, and they’re slow to build. New entrants have to prove they can hit quality standards consistently and integrate smoothly into customers’ production and logistics routines. Taken together—capital intensity, regulation, and relationship-based selling—the threat of new entrants stays low.

Supplier Power: Moderate

The key input in galvanizing is zinc, and zinc prices move. That creates real exposure to commodity volatility, which can squeeze margins if costs spike faster than pricing can adjust.

AZZ’s scale helps here. Bigger operators typically have more negotiating leverage, and they’re better positioned to manage purchasing and pass through some commodity cost changes to customers. Supplier power is meaningful, but it’s generally manageable—more of a variable to be managed than an existential threat.

Buyer Power: Moderate

AZZ sells to large steel fabricators, construction firms, and industrial manufacturers—buyers that are experienced, price-aware, and capable of putting work out to bid. On paper, that should translate into strong buyer power.

In practice, it’s moderated by how the business works. Galvanizing is local. The job is mission-critical. And switching isn’t free—there are qualification expectations, scheduling realities, and the risk that a new supplier misses turnaround or quality targets. Long-standing relationships and service consistency create stickiness that limits how far buyers can push purely on price.

Threat of Substitutes: Low

There are alternatives—paint systems, powder coating, different alloys—but for many structural applications, hot-dip galvanizing remains the workhorse. It’s durable, cost-effective over the lifecycle, and proven in the field.

There’s a reason the process has endured for nearly two centuries: for the core use case of protecting steel outdoors, substitutes often lose on longevity, reliability, or economics. So the substitute threat stays low.

Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: Moderate

AZZ’s scale shows up in purchasing, shared services, and the ability to move best practices across a large network. But the scale advantage isn’t purely national. A dominant footprint in one region doesn’t automatically create operational advantage in another; galvanizing remains a regional game.

So the scale economies are real, but they compound most where AZZ has density.

Network Effects: Weak

This isn’t a network effects business. A galvanizing plant doesn’t become more valuable because more people use it, the way a marketplace or software platform does. The value comes from execution, location, and reliability—not user-to-user reinforcement.

Counter-Positioning: Historically Strong

AZZ’s portfolio reshaping—buying Precoat and divesting a controlling stake in Infrastructure Solutions—was a clear act of counter-positioning. The company chose focus: become a coatings specialist at scale, rather than remain a diversified industrial player.

Whether that proves to be the “right” position will depend on how returns and growth in coatings play out over time versus the infrastructure businesses it stepped away from. But as a strategic move, it was distinct and difficult for more diversified competitors to mirror quickly without disrupting their own portfolios.

Switching Costs: Strong

Switching costs are one of the quiet sources of durability here. For galvanizing, changing providers can mean re-qualification, potential re-certification depending on the end application, and disruption to logistics and scheduling. For coil coating, switching can involve custom formulations, color matching, and application-specific quality requirements that customers don’t want to rework unless they have to.

When failure or inconsistency is expensive, customers tend to stay with suppliers that have proven they can deliver.

Branding: Moderate

AZZ doesn’t have consumer brand power, but it does have reputation inside its niches. That brand functions more like a trust mark than a marketing lever—helping with customer confidence and, to some extent, attracting and retaining talent. It matters, but it’s not the kind of brand that automatically commands a premium on its own.

Cornered Resource: Moderate

AZZ’s network of facilities is a cornered resource in the practical sense: it took decades, significant capital, and sustained execution to assemble. A competitor can’t replicate that footprint overnight—especially with permitting and siting hurdles.

There’s also a capability angle. Technical know-how around coating performance, complex fabrication geometries, and other specialized requirements is learned over time, not bought in a catalog.

Process Power: Strong

In industrial services, “how you do the work” becomes the moat. AZZ has had decades to refine throughput, quality control, safety, scheduling, and customer service. Those improvements are rarely visible from the outside, but they show up in consistency and turnaround—two things customers will pay for, and competitors struggle to copy quickly.

Overall Assessment: AZZ’s moat is moderate, and in the areas that matter—switching costs, process power, and facility positioning—it can be quite durable. It’s strongest where AZZ has regional density and in applications where reliability and qualification requirements make customers reluctant to experiment.

XI. Bull vs. Bear Case

Bull Case

AZZ now sits in a pretty enviable place: right where several long-duration infrastructure waves overlap. The U.S. grid is aging and getting upgraded. Data centers—pushed by AI and cloud—are driving a new cycle of industrial construction and electrical buildout. Renewables continue to add steel-heavy projects that have to survive decades outdoors. None of these are one-year fads. They’re multi-decade demand drivers, and coatings show up in the physical backbone of all of them.

Industry forecasts point to steady growth in hot-dip galvanizing over the next decade, with a mid-single-digit growth rate baked into many projections. The important takeaway isn’t the exact market sizing—it’s that the category tends to grow with infrastructure, is hard to replace with substitutes at scale, and benefits from the same “build it once, maintain it forever” dynamic that defines roads, bridges, and transmission.

On top of that, AZZ has already proven it can make hard strategic moves and execute them. Management divested businesses that weren’t fitting, bought Precoat to expand coil coating at scale, and has talked consistently about a clear capital allocation stack: integrate well, generate cash, pay down debt, reinvest in the network, and only then look for selective acquisitions or increased shareholder returns.

The result is the cleanest, most focused AZZ has been in decades—two coatings platforms with real scale. Profitability has held up at levels that look strong for industrial businesses, and the balance sheet has been moving in the right direction as leverage comes down.

From an equity story standpoint, there’s also a simple “under-the-radar” angle. AZZ isn’t a household name, and it doesn’t sit in a high-glamour sector. If the company keeps delivering steady execution while infrastructure spending and industrial build cycles remain supportive, it’s the kind of business that can earn more attention over time—and sometimes, higher valuation multiples come with that attention.

Bear Case

For all the durability in coatings, AZZ is not immune to cycles. Construction slows in recessions. Industrial capital spending can freeze quickly. If volumes soften, operating leverage can work in reverse and pressure margins faster than many investors expect.

There’s also commodity exposure you can’t engineer away. Zinc and energy inputs like natural gas matter. When those costs swing, they can create earnings volatility even if underlying demand is fine—especially if price increases lag cost increases.

Competition is another real risk. AZZ faces both scaled and regional competitors, including players like Valmont Industries and Voestalpine. And while galvanizing and coating have meaningful barriers—capital, permitting, customer qualification—large industrial and steel-adjacent companies can still decide a market is attractive and push harder into it, whether organically or by acquiring smaller operators.

Then there’s the reality of infrastructure spending: it’s often slower than the headlines suggest. Federal funding can take time to reach projects, and permitting can stretch timelines. Even if the long-term demand is there, the near-term cadence can disappoint.

AZZ also doesn’t have a single runaway “power law” asset. It’s well-positioned across multiple end markets, but it isn’t dependent on one category exploding upward. That diversification can stabilize results—but it can also cap upside in any one boom scenario.

Finally, integration and complexity risk never fully disappears. If AZZ returns to aggressive M&A, the company’s own history is the cautionary tale: it’s easy to buy faster than you can digest.

And on the market mechanics side, smaller-cap liquidity can amplify volatility. In periods of stress—or even around earnings—stocks like this can move sharply for reasons that have little to do with long-term fundamentals.

Key Performance Indicators to Track

Three KPIs matter most for monitoring AZZ’s execution and strategic progress:

1. Segment EBITDA Margins

Metal Coatings segment margins around 30% and Precoat Metals margins around 20% are the current benchmarks. Holding those levels suggests strong execution and pricing discipline. Sustained improvement would be a sign of operating leverage and process gains. Sustained deterioration would be an early warning—either competitive pressure, cost pass-through issues, or operational slippage.

2. Net Leverage Ratio

AZZ used meaningful debt to fund the Precoat acquisition, so deleveraging is central to the story. The current trajectory—below 2.5x—signals healthy cash generation and declining financial risk. A path toward 2.0x or lower increases flexibility for reinvestment, shareholder returns, or selective M&A. If leverage stalls or starts rising again, the risk profile changes quickly.

3. Organic Revenue Growth

With the portfolio transformation largely complete, organic growth becomes the cleanest read on whether AZZ is winning in its markets. Consistent growth above broader economic growth supports the “infrastructure tailwinds + strong positioning” thesis. Persistent underperformance can indicate share loss, weaker end markets, or a cycle turning faster than expected.

XII. Epilogue & Final Reflections

The transformation is complete. AZZ Inc.—the company R.G. Anderson founded as Aztec Manufacturing in 1956 to build electrical equipment for Texas oil fields—reached 2025 as North America’s largest hot-dip galvanizer and a leading independent coil coater. That arc took nearly seventy years and ran through just about every kind of business weather: acquisition sprees and divestitures, oil price collapses and COVID-era chaos, and the kind of strategic decisions that force a company to choose what it wants to be for the next decade, not what it used to be.

AZZ now describes itself plainly: North America’s leading independent provider of hot-dip galvanizing and coil coating services. Its job is simple to explain and hard to do at scale—apply metal coatings that make buildings, products, and infrastructure last longer and look better, while working to reduce its carbon footprint. It’s not a consumer brand. It’s an industrial utility: the company you depend on without realizing you’re depending on it.

So what comes next? The playbook from here is less dramatic, but no less important: keep growing organically, squeeze more operating leverage out of the footprint as volumes rise, and pursue selective tuck-in acquisitions that expand geography or add capability. If the big infrastructure themes of the next decade play out the way policymakers and utilities say they will—grid upgrades, data center construction, renewables buildout, reshoring and industrial expansion—coatings will be everywhere in the physical backbone of that investment.

But the bigger lesson of AZZ isn’t about a specific end market or a particular deal. It’s about where great business stories actually live. Sometimes they’re not in the companies that “change the world” with a new app. They’re in the industrial B2B businesses hiding in plain sight—companies that make the roads safer, the power grid sturdier, and the structures around us more durable, by doing one unglamorous thing extremely well.

AZZ didn’t disrupt anything. It didn’t invent a category or build a breakthrough technology platform. What it did was, in its own way, harder: it compounded operational excellence in a sector where execution is the product, rode out cycles that punished overextension, and made the kind of portfolio decisions that reshape a company’s identity.

For founders and investors, the AZZ story leaves a few durable takeaways:

Heritage doesn’t determine destiny. AZZ began in electrical equipment, became dominant in galvanizing, expanded into infrastructure solutions, and then refocused on coatings. Each time, it chose forward motion over nostalgia.

Strategic courage means knowing what to give up. The 2022 transformation only worked because AZZ was willing to sell majority control of Infrastructure Solutions—real businesses with real history—to concentrate capital and attention on a clearer coatings thesis.

Boring can be beautiful. There’s no hype cycle in galvanizing. Just a proven metallurgical process, executed consistently across a large network, producing cash flows that can compound for decades.

Positioning matters more than perfect timing. AZZ didn’t need to forecast exactly when infrastructure spending would accelerate. By building scale in galvanizing and buying into coil coating, it positioned itself to benefit whenever the spending showed up.

The final surprise is the simplest one: sometimes the best growth stories are in the boring industries. The companies that protect critical infrastructure create enormous value precisely because their work lasts. In a world obsessed with novelty, there’s something quietly powerful about a business that’s been keeping steel from rusting since Eisenhower was president.

AZZ Inc. won’t dominate headlines. But it represents the quiet backbone of industrial America—essential work, real economics, and a strategy built to endure. One galvanized beam at a time.

XIII. Further Reading & Resources

Top 10 Long-Form Resources

- AZZ Inc. Annual Reports (2012, 2017, 2022, 2024) - The clearest way to track AZZ’s evolution in its own words, especially the 2022 materials that document the portfolio transformation

- "The Outsiders" by William Thorndike - A useful lens for understanding AZZ’s capital allocation across acquisition waves, then the pivot toward simplification and focus

- American Galvanizers Association Resources - Solid technical grounding on galvanizing, plus market context and the Excellence Awards program that highlights new applications and best practices

- Industry Reports: U.S. Hot-Dip Galvanizing Market - Market sizing, growth drivers, and competitive landscape work from sources like IBISWorld, Fortune Business Insights, and Market Research Future

- "The Grid: The Fraying Wires Between Americans and Our Energy Future" by Gretchen Bakke - A readable, systems-level look at why grid modernization is slow, essential, and inevitable

- SEC Filings: 10-K, Proxy Statements, 8-Ks (2019–2024) - The primary-source trail behind the Precoat acquisition and the Infrastructure Solutions divestiture

- Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act: Analysis & Implications - Frameworks and timelines from McKinsey and BCG on how federal infrastructure funding translates into real projects

- Conference Call Transcripts (2020–2024) - Where strategy turns into plain language: what management prioritized, what they worried about, and how integration progressed

- "Built to Last" by Jim Collins - A classic reference for thinking about durability, culture, and long-term compounding in industrial companies

- Data Center Market Reports - Background on the AI- and cloud-driven data center buildout and the knock-on demand it creates for steel-heavy infrastructure

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music