AXT Inc.: The Substrate Story - Building the Foundation of Modern Technology

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture this: it’s 2019, and you’re scrolling on your iPhone. You tap Face ID. An infrared system projects and reads a pattern on your face, and at the heart of that stack is a tiny laser built from gallium arsenide. But that chip doesn’t start as a chip. It starts as a substrate: a nearly perfect crystal wafer, sliced impossibly thin, that everything else gets grown on top of.

That wafer likely came from a company you’ve almost certainly never heard of: AXT Inc., tucked into an unremarkable office park in Fremont, California.

Here’s the trick of modern hardware: the most important companies are often the ones you never see. What do 5G networks, facial recognition, and LED lighting have in common? They all depend on compound semiconductor substrates, the crystalline foundations that make high-performance chips possible when plain silicon can’t keep up.

That’s AXT’s world. It develops and manufactures semiconductor substrate wafers made from indium phosphide (InP), gallium arsenide (GaAs), and germanium (Ge). These materials show up wherever performance matters: 5G infrastructure, data center connectivity, passive optical networks, LED lighting, lasers, sensors, power amplifiers for wireless devices, and even the solar cells on satellites.

And that brings us to the question at the center of AXT’s four-decade journey: how does a small Silicon Valley materials company survive and compete in an industry increasingly dominated by Asian giants with massive scale—and, often, state-backed capital?

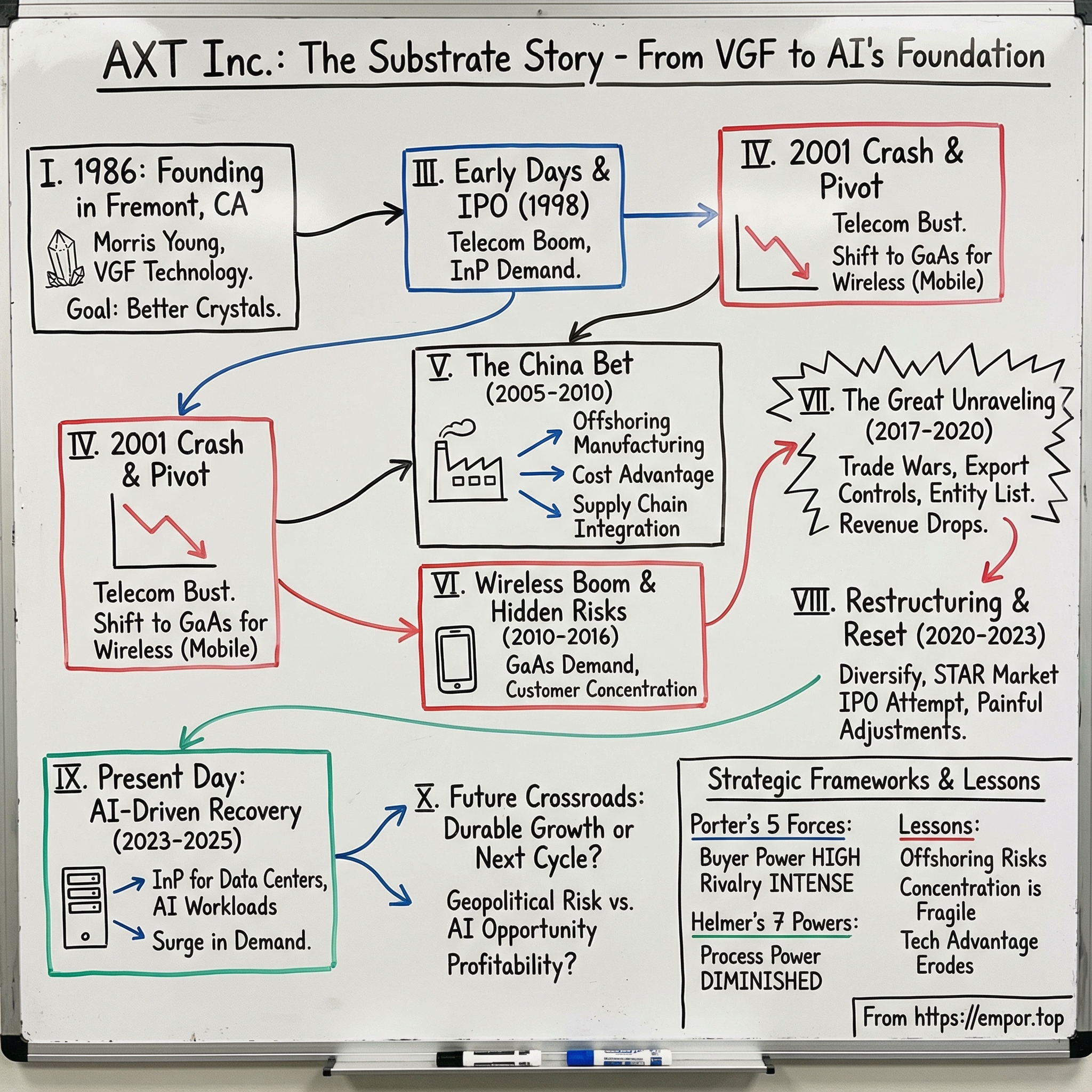

The answer isn’t a straight line. It’s a sequence of big bets and brutal lessons: early technical innovation, near-death moments when markets collapsed, and a controversial China manufacturing strategy that became both the company’s lifeline and, later, its biggest vulnerability. Now, with artificial intelligence reshaping demand across the semiconductor stack, AXT finds itself at another crossroads.

In its fiscal year 2024 results, CEO Morris Young called it “a year of improvement for AXT in several key areas,” pointing to a 31 percent increase in revenue, a 21 percent improvement in non-GAAP gross profit, and a 40 percent improvement in non-GAAP net loss. But that progress came off a deeply depressed base. AXT is still unprofitable, still fighting structural disadvantages, and still searching for a durable edge.

If this sounds familiar, it should. It’s the classic globalization arc in manufacturing: innovate early, offshore to win on cost and proximity, enjoy the gains—and then realize, years later, that the decisions that were smart in 2005 can become liabilities by 2019.

AXT’s story is a cautionary tale about customer concentration, the double-edged sword of operating in China, and what happens when competitive advantages erode faster than new ones can be built.

So let’s start where every substrate story starts: with the physics—what makes these materials special, why they matter, and why anyone would choose to compete in a business this technical, cyclical, and now geopolitically fraught.

II. What Are Compound Semiconductors & Why They Matter

Inside semiconductor fabs around the world, engineers keep running into the same fork in the road: do we stick with silicon, or do we reach for something else?

Most of the time, silicon is the obvious answer. It’s abundant. It’s predictable. And it rides on decades of relentless manufacturing refinement. That’s why it dominates the processors in your laptop, the memory in your phone, and the chips buried all over your car.

But silicon has hard limits. It’s not a great light emitter. It’s not happy at the highest radio frequencies. And in certain high-power scenarios, it simply can’t take the heat. When performance pushes past what silicon can do, the industry turns to compound semiconductors: materials built by combining elements from different groups of the periodic table to get very different physics.

Gallium arsenide—GaAs—is one of the workhorses. It has electron mobility roughly five times greater than silicon, which is a big deal for radio-frequency performance. In plain English: GaAs is why your smartphone can reliably push a tiny, weak signal out to a cell tower. Those GaAs-based power amplifiers sit in the RF front-end, quietly doing the heavy lifting. GaAs is also excellent at turning electricity into light, which is why it shows up in LEDs and in the VCSELs, the vertical-cavity surface-emitting lasers that power systems like Face ID.

Then there’s indium phosphide, or InP, which lives even further out on the “only if you really need it” end of the performance spectrum. InP substrates underpin the lasers that move data through fiber optic cables at staggering speeds—the backbone of the internet, cloud computing, streaming, and video calls. And lately, InP has been getting a fresh tailwind: AI workloads are driving demand for higher-data-rate optical links, which pushes harder on laser performance and, potentially, accelerates the industry’s shift toward larger wafers, including 6-inch InP.

Here’s the twist: as essential as these materials are, the economics are nothing like silicon. The compound semiconductor substrate market is projected to reach about US$3.3 billion by 2029, growing quickly from 2023 to 2029—but it’s still tiny next to the silicon wafer market, which is measured in the tens of billions every year. That’s the first constraint any compound semiconductor supplier lives with: even if you’re great at what you do, the market isn’t infinitely large.

It’s also a concentrated world. AXT, Sumitomo Electric, Freiberger, and SICC are among the leading suppliers across GaAs and InP (and related substrate categories), and the growth playbook often looks the same: expand beyond a single material and chase adjacent applications where the same customer base and manufacturing know-how can carry over. That’s why you’ll see talk about “synergies” between GaAs and InP for RF, photonics, and even emerging areas like µLEDs.

Structurally, substrate makers sit at the bottom of a long, unforgiving value chain. Their job is to grow single crystals, slice them into wafers, and polish them to near-atomic perfection. Those wafers go to epitaxial wafer producers, who deposit thin layers of additional materials. Then device manufacturers turn those stacks into the lasers, amplifiers, and sensors the world actually buys. If anything goes wrong early—crystal defects, impurities, poor uniformity—everyone upstream pays for it.

In InP specifically, the mainstream wafer size has historically been 3 inches. The next step up—6 inches—is a huge deal because bigger wafers mean more devices per run and lower costs per chip. Market leaders such as Sumitomo Electric and AXT have shown they can produce good-quality 6-inch InP and have been shipping meaningful volumes for R&D, which is where these transitions start before they become production realities.

None of this is easy. Growing defect-free GaAs or InP crystals requires extreme purity, tight process control, and yields that have to make economic sense, not just scientific sense. And even clever workarounds can be brutal: integrating InP-based technologies onto GaAs substrates runs straight into lattice mismatch—nearly a 4 percent difference in atomic spacing—which makes high-quality epitaxial growth inherently difficult.

For a long time, those technical hurdles were the moat. But the modern reality is messier. With enough investment—and, in some cases, government support—new entrants have proven the barriers aren’t insurmountable. Which sets up the uncomfortable question that hangs over AXT’s entire story: are the remaining advantages in compound semiconductor substrates durable enough to protect pricing and margins, or is this market drifting toward the same commoditization that’s swallowed so many other layers of the semiconductor supply chain?

This physics and these economics are the stage. AXT was founded because someone believed the hardest technical problems would create lasting competitive advantage. Whether that bet paid off—across booms, busts, offshoring, and geopolitics—is what we’re about to find out.

III. Founding Story & Early Silicon Valley Days (1986-1999)

In 1986, in a small Fremont, California office, a physicist named Morris Young made a very specific kind of bet: that the way you grow a crystal could decide who wins an entire slice of the semiconductor industry.

AXT was founded that year to commercialize a technique for growing gallium arsenide and indium phosphide crystals called vertical gradient freeze, or VGF. Before starting the company, Young worked as a physicist at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. His background was deeply materials-driven: a bachelor’s degree in metallurgical engineering from Chengkung University in Taiwan, a master’s in metallurgy from Syracuse University, and a PhD in metallurgy from Polytechnic University.

The insight behind AXT was simple to explain and hard to execute. The incumbent methods for growing compound semiconductor crystals came with painful trade-offs: too many defects that dragged down chip yields, crystals that were brittle enough to crack during processing, and built-in stress that made downstream manufacturing harder. If you could produce cleaner, stronger wafers, customers wouldn’t just prefer you—they’d build their processes around you.

AXT’s answer was VGF. The company pioneered its commercialization for compound semiconductor substrates, touting advantages like lower etch pit density compared to conventional methods, lower stress, and higher mechanical strength. In practice, that meant fewer broken wafers on customer lines and better yields—exactly the kind of unglamorous advantage that wins orders in a manufacturing supply chain.

Young co-founded AXT in 1986 and went on to serve as President, CEO, and Chairman from 1989 to 2004. The early years were about turning a lab-worthy process into a reliable commercial one—and doing it at scale. AXT built its primary production facility in Fremont, a very Silicon Valley decision for the era, back when a meaningful share of semiconductor manufacturing was still done in the U.S.

The company’s original name was American Xtal Technology, Inc. (it wouldn’t rebrand to AXT, Inc. until July 2000). But the bigger milestone came earlier: the IPO. AXT went public in 1998, right as the dot-com era hit full stride and telecom infrastructure spending was surging.

And that timing mattered. The late-1990s fiber optics boom drove intense demand for InP substrates—the foundation for the lasers that push data through optical networks. Under Young’s stewardship, AXT expanded rapidly, riding a market that felt, at the time, like it could only go one direction. VGF, meanwhile, was proving itself not just as a clever approach, but as a scalable one—eventually becoming the most widely used method for producing low-defect III-V substrates on a volume basis.

By the turn of the century, AXT was already thinking in “build-out” mode. In 2001, it announced plans to roughly triple gallium arsenide substrate production capacity by the end of the third quarter. Most of that expansion was expected to happen in Beijing, where AXT already operated a 62,000-square-foot GaAs production facility and had purchased an additional 36,000-square-foot building next door—setting the stage for a much larger footprint.

Young framed the move in the language of demand and momentum: customers were increasing orders, wireless handsets were growing fast, and larger—six-inch—GaAs substrates were becoming more popular.

Looking back, it’s hard not to see the plot points lining up. VGF gave AXT real differentiation. An early manufacturing presence in China hinted at a cost and scale advantage that would later become central to the company’s strategy. But the end markets AXT was tied to—telecom infrastructure and the broader communications build-out—were also famously cyclical.

As Chairman Jesse Chen would later put it, Young was “a visionary technologist, a pioneer of the gallium arsenide industry and the person most responsible for the early growth and success of AXT.” The problem with riding a boom is that it convinces you the demand is permanent. The next chapter would test that assumption—brutally.

IV. The Post-Bubble Crash & Strategic Pivot (2000-2004)

The morning of March 10, 2000 marked the peak of the NASDAQ, a moment of maximum euphoria that would come to define an era. For AXT, those years had meant explosive growth as fiber optic networks consumed InP substrates at a furious pace. But by the end of that same year, the mood had flipped. Fast.

What followed was the telecom crash of 2001, the industry’s version of a hangover after a decade-long party. Through the 1990s, telecom companies had borrowed heavily to build networks for a future that, in hindsight, arrived far more slowly than anyone modeled. Investors had poured billions into the sector on optimistic assumptions about bandwidth demand and profitability. When the dot-com bubble burst and the broader U.S. economy softened, the entire premise collapsed at once.

The scale of the unraveling was brutal. Hundreds of thousands of people lost their jobs. Telecom-related stock indexes fell by amounts more commonly associated with historic crashes. Trillions of dollars in market value evaporated, and a huge chunk of that destruction landed squarely in telecom.

For AXT, selling into this carnage, the impact wasn’t abstract. It was immediate and operational. The fiber optic build-out that had been eating InP wafers simply stopped. Orders that had felt “booked” disappeared. Customers who had been calling for more capacity went quiet. And AXT had just been leaning into expansion.

The timing couldn’t have been worse. AXT suddenly found itself with expanded manufacturing capacity in both Fremont and Beijing just as demand collapsed. Add in the disorientation of the post-bubble era—and a brief, aborted move into optoelectronic device manufacturing—and the company began piling up substantial losses.

This is the part of the story where a lot of suppliers don’t make it. Many of AXT’s customers and ecosystem partners didn’t. AXT survived, but not by drifting. It had to make hard choices: slash costs, tighten operations, and triage everything that wasn’t essential.

The crucial decision was what not to cut. Even as it reduced its cost structure, AXT worked to preserve the capabilities that actually mattered: its core manufacturing know-how, its R&D expertise, and the VGF process that had differentiated it in the first place. In a downturn, that’s a counterintuitive move—because it keeps your burn higher—but it also keeps you alive as a real company when demand returns.

Just as importantly, AXT pivoted its market focus. If InP for fiber optics had been the boom, GaAs for wireless was the lifeline. Mobile phones were proliferating fast, and each handset needed RF power amplifiers—exactly the kind of component where GaAs substrates shine. It was still a cyclical market, but it wasn’t tied to the same one-time infrastructure binge that had just imploded.

By 2003 and 2004, the slow recovery began, and leadership began to shift. Morris Young—co-founder and the company’s President, CEO, and Chairman from 1989 to 2004—started transitioning out of the top role. From 2004 to 2006, he served as CEO of AXT China Operations and Chief Technology Officer.

The near-death experience left AXT with a new operating philosophy. It reinforced, painfully, that cyclicality wasn’t a theoretical risk—it was existential. It also made two ideas feel like facts: that diversification away from a single end market wasn’t optional, and that China operations could be a powerful lever for cost control in a downturn.

Those were the lessons AXT carried into the next phase. The question was whether they were the right ones—and whether the survival playbook of 2001 would quietly become the strategic doctrine that defined the company for the next decade.

V. The China Bet: Offshoring Manufacturing (2005-2010)

Standing in Fremont in the late 1990s, Morris Young faced a decision that would define AXT for decades. The telecom boom was roaring, demand was surging, and AXT needed more capacity fast. The question wasn’t whether to grow—it was where. And whatever answer AXT chose would quietly rewire its cost structure, its supply chain, and its risk profile.

In 1998, AXT began exploring business in China. Over time, it shifted more and more of its manufacturing—and eventually its R&D—there, establishing Beijing Tongmei. For a Silicon Valley materials company, this wasn’t a small tweak. It was a strategic relocation built on a simple logic: far lower labor costs, closer proximity to a growing base of Asian customers, better access to raw materials, and the ability to scale without the same capital and operating constraints as U.S. production.

Young didn’t downplay how central the move was.

"Expansion in China is a key component of our plans to strengthen our position as the world's leading provider of compound substrates," he said. "We consider our China operation to be the cornerstone of our growth strategy. Our presence in China brings us closer to many of our customers and sources of raw materials, and improves our efficiency, competitiveness, and control over production costs."

AXT didn’t stop at moving factories. It started pulling the supply chain upstream.

It announced that it had become a 51 percent owner of Beijing Ji-Ya Semiconductor Material Company, Ltd., a gallium extraction facility in Shan Xi, China. The facility began production in late 2001 and was capable of producing around 20 tons of gallium per year—enough to cover most of AXT’s needs during peak periods. AXT and its partners had developed the proprietary extraction process over the prior eighteen months, pulling gallium from aluminum ore. And that mattered because gallium was the largest single raw material cost in a gallium arsenide substrate.

Young framed the investment as insurance.

"Our investment in Beijing Ji-Ya Semiconductor Material Company provides us with a secure source of gallium," he explained. "During early 2001, our production was nearly affected by a lack of this critical raw material and we were forced to pay high prices for some of the gallium we purchased. With our new investment, the likelihood of future supply problems is significantly reduced and we are better protected from price fluctuations."

By 2010, the transformation was largely complete. AXT had gradually transferred its production and R&D fully to China. It shut down U.S. production and maintained overseas sales, purchasing, and partial application R&D. The China-side operating company sold products to AXT on a cost-plus basis; AXT then earned returns from selling to overseas customers, and those returns funded normal operations and application R&D.

In other words: the center of gravity moved. The U.S. became the commercial and technical interface with global customers. China became the manufacturing engine.

And AXT didn’t just build one site. It established its Asia headquarters in Beijing and ran manufacturing facilities across three separate locations in China. As part of its supply-chain strategy, it also took partial ownership in ten Chinese companies producing raw materials used in its manufacturing processes.

On paper, the benefits were obvious. The China footprint helped AXT compete on price against Asian rivals while preserving gross margins that would have been far harder to sustain with U.S.-based manufacturing. And as more customers shifted their own operations into Asia, having a nearby substrate supplier wasn’t just cheaper—it was operationally convenient.

But the same decision that strengthened AXT’s competitiveness also embedded a new kind of risk—one that didn’t show up in cost models.

AXT built extensive ties to China beyond its factories. The company owned an 85 percent stake in a Chinese subsidiary that produced semiconductor materials and counted, among its major customers, a large state-owned defense firm. A division of that defense firm was later among the Chinese companies the Biden administration blacklisted for providing "support" to the People's Liberation Army's aerospace programs; at least 20 of its subsidiaries and divisions had been added to the entity list since 2018.

In the mid-2000s, those dangers didn’t feel real. U.S.-China relations were relatively stable. Globalization was still treated as an unambiguous good. The idea that semiconductor materials could become leverage in great-power competition would have sounded dramatic, even paranoid. Even hiring choices that fit local industry norms—like AXT’s Beijing Tongmei technical director, who had spent 15 years at a major Chinese state-owned defense contractor before joining AXT in 2005—would later look very different through a 2020s geopolitical lens.

Young’s call—that China would be “the cornerstone” of AXT’s growth—played out exactly as he hoped. The problem was that the world around that cornerstone was about to shift.

VI. The Wireless Boom Era (2010-2016)

The 2010s opened with a new boom already sitting in people’s pockets. The iPhone had kicked off the smartphone era, Android was spreading globally, and the shift from 3G to 4G LTE was turning mobile connectivity from a convenience into a baseline expectation.

For AXT, that translated into one very concrete thing: surging demand for gallium arsenide substrates.

Inside every smartphone are multiple RF components—especially power amplifiers—that rely on GaAs. Their job is simple to describe and hard to do well: take a weak signal and push it out reliably to a cell tower without draining the battery or cooking the phone. As networks got faster and more complex, phones needed more RF bands, more filtering, and more sophisticated front-ends. And that meant more GaAs-based devices, which meant more demand at the very bottom of the stack: the substrate wafer.

This was the era when RF chipmakers like Skyworks Solutions and Qorvo became household names in the investing world. When they grew, their upstream ecosystem grew with them—and AXT was positioned to be one of the quiet enablers.

In AXT’s own framing, what was driving the RF wave wasn’t just phones. It was the broader spread of cellular and WiFi-connected devices—tablets, connected cars, connected homes, and the early build-out of the Internet of Things. Every one of those endpoints needed a “bevy” of RF semiconductors, from switches to power amplifiers, all ultimately grown on wafers—substrates—like the ones AXT specialized in.

This is also where the China bet showed its upside. AXT’s manufacturing footprint and supply-chain investments in China weren’t just about labor costs. The company had manufacturing facilities in China, plus stakes in ten subsidiaries and joint ventures that produced raw materials used in its processes. That vertical integration helped AXT compete aggressively on price while protecting margins that would have been far harder to sustain if production had remained in the U.S.

What’s interesting is that, on the surface, the customer risk didn’t look alarming. In 2016, no single customer accounted for more than 10% of revenue. Key customers likely included major RF players like Skyworks Solutions and Qorvo, given their roles in the market. And the highest-volume opportunity in substrates remained GaAs, fueled by smartphones and other fast-growing connected categories—augmented and virtual reality devices, gaming, and facial recognition security applications among them.

Meanwhile, the diversification strategy AXT had leaned into after the 2001 crash kept expanding. InP substrates served fiber optic networks, passive optical networks, and data center connectivity. Germanium substrates supported satellite solar cells, optical sensors, and infrared detectors. But the center of gravity was clear: GaAs for wireless drove the volume.

AXT also continued to lean on what had made it credible in the first place: process and material quality. The VGF crystal growth expertise Morris Young had commercialized decades earlier still mattered, especially for customers pushing into more demanding applications. The company emphasized its ability to deliver extremely low defect densities in InP and GaAs substrates—exactly the kind of capability that determines whether downstream customers get high yields or expensive headaches.

And yet, even in the good years, the cracks were visible if you knew where to look.

Customer concentration was still a structural issue—just hidden one layer up the chain. Even if no single customer crossed 10% in a given year, the end markets were concentrated. Smartphones were dominated by a handful of OEMs, and RF components by an even smaller circle of suppliers. If any of those major players stumbled, AXT would feel it.

At the same time, Chinese domestic competitors started showing up with improving quality and, often, the ability to win business at the lower end of the market. In a strange twist, the same China manufacturing strategy that gave AXT a cost advantage also helped normalize the playbook that others could follow—especially companies selling into a vast, fast-growing domestic market.

And then there was the background hum AXT couldn’t ignore forever: geopolitics. In 2015 and 2016, it was easy to treat U.S.-China tension as noise. The smartphone boom was still running, 5G was on the horizon, and AXT’s China footprint still looked like a masterstroke.

The problem was that the world was changing around that footprint—and the bill for those risks was getting closer.

VII. The Great Unraveling: Trade Wars & Customer Concentration (2017-2020)

By 2018, AXT looked like it had done the hard part. It had survived the telecom crash, found its footing in wireless, and built a cost structure that let it compete in a tough market.

Then the ground shifted under it.

The U.S.-China trade war escalated quickly in 2018. Tariffs grabbed headlines, but for AXT, tariffs weren’t the real threat. Export controls were.

In this new era of technology conflict, the most consequential policy tool was the Commerce Department’s entity list: a designation that can effectively wall off a company from U.S.-connected suppliers and technology. Once major Chinese tech firms started landing on that list, the shock didn’t stop with them. It rippled through the entire supply chain—component makers, module makers, and all the way down to substrate wafers.

AXT sat in an especially awkward place. Its manufacturing was overwhelmingly in China. Many of its customers, and many of their end markets, were global—and therefore exposed to U.S. policy. When customers got hit, demand didn’t just soften. In some cases, it vanished because purchasing became legally or operationally impossible.

Morris Young captured the tone when discussing 2019 results: "Q4 capped off a challenging year in which we weathered one of the most difficult demand environments in recent memory. Overall, this had a negative impact on key applications and certain customers within AXT's gallium arsenide and germanium businesses, making up the majority of our year-over-year revenue decline."

The numbers told the same story. Fourth-quarter 2019 revenue fell to $18.4 million, down from $22.2 million a year earlier. Gross margin slid too, to 21.0 percent from 26.3 percent.

And this is where the risk that had been easy to ignore in the boom years finally showed itself: concentration.

Not necessarily in any one customer at any one moment, but in the reality that AXT’s customer set clustered around the same few end markets and supply chains. When those channels got disrupted—by entity list rules, shifting sourcing decisions, or sudden demand freezes—the impact was multiplied. Diversification across products didn’t fully protect you if your customers were all downstream of the same geopolitical fault line.

Then came COVID-19 in early 2020, and whatever “stability” remained was gone. The pandemic disrupted operations in China, tangled logistics, and made forecasting demand feel like guessing the weather during a hurricane. For AXT, it was crisis on top of crisis.

On earnings calls in the years that followed, the company would repeatedly return to the same theme: geopolitics and trade restrictions were no longer background noise. They were an operating condition.

In hindsight, 2017 to 2020 exposed the fragility of AXT’s position. The China strategy that had powered its competitiveness in the 2000s and early 2010s now came with a price tag. Manufacturing in China meant living under Chinese policy. Selling into global markets meant living under U.S. policy. AXT ended up caught in the middle, in what many were starting to describe as a new Cold War.

Revenue fell hard. The stock followed. And the question that had once sounded academic suddenly became unavoidable: was the China bet a mistake?

The honest answer is complicated. Those China operations delivered years of real advantage, and they likely kept AXT viable when U.S.-based manufacturing would have been too costly. But concentrating so much of the company’s production in one country—especially one moving into open strategic competition with the United States—created a risk that didn’t show up on the spreadsheets when the decision was made.

VIII. Restructuring & Search for New Markets (2020-2023)

From 2020 through 2023, AXT entered what amounted to a strategic reset: painful adjustments, an urgent push to diversify beyond wireless, and a high-stakes financial maneuver in China that, as of late 2025, still wasn’t finished.

The company came out of the trade-war shock smaller, but not resigned. Management’s playbook ran on three parallel tracks: cut costs, broaden the business away from its most fragile demand pockets, and try something unusual for a U.S.-listed semiconductor supplier—take its China subsidiary public on Shanghai’s STAR Market.

On January 10, 2022, AXT announced that Beijing Tongmei Xtal Technology Co., Ltd., its Beijing-based subsidiary, had submitted an application to list shares in an IPO on the Shanghai Stock Exchange’s Sci-Tech Innovation Board, better known as the STAR Market. CEO Morris Young put a narrative frame around it: “We founded Tongmei back in 1998. Since then, it has grown into a company that is engaged in the research, development, production and sale of InP substrates, GaAs substrates, germanium substrates, PBN and other high-purity materials, which we believe makes it an attractive offering on the STAR Market.”

The logic was compelling. On July 12, 2022, the Shanghai Stock Exchange approved Tongmei’s proposed STAR Market listing. On August 1, 2022, the China Securities Regulatory Commission accepted Tongmei’s IPO application for review. If AXT could get it over the finish line, it could potentially unlock expansion capital inside China without diluting AXT’s U.S. shareholders—and, just as importantly, signal that Tongmei had real standalone value.

But the process didn’t move on Silicon Valley timelines. Even AXT cautioned that a STAR Market listing involves multiple rounds of review and can take a long time. As of late 2025, the IPO still remained subject to review and approval by the CSRC and other authorities. The status of AXT as a U.S. public company wouldn’t change—but the uncertainty dragged on.

While that chess match played out, the operating business was taking punches. In the second quarter of 2023, AXT reported revenue of $18.6 million, down sharply from $39.5 million a year earlier. Indium phosphide fell especially hard, with revenue of $4.6 million versus $15.7 million a year earlier, as markets softened—particularly data center, consumer, and telecom infrastructure.

The first quarter of 2023 told the same story: revenue of $19.4 million, down 51.1% from $39.7 million a year earlier. Young described the mechanism in real-world terms: “Revenue took a step back in Q1 as the inventory correction that we began to see in gallium late last summer accelerated in phosphide applications. Indium phosphide held fairly firm through January and then experienced a meaningful decline in February and March, most notably in the data-center and consumer applications.”

The pivot to new applications showed flickers of progress, but not enough to change the trajectory. “The demand environment in Q3 2023 remained stable, and we were pleased to see some encouraging early signs of improvement in the data center market, resulting in modestly higher indium phosphide revenue quarter over quarter,” Young said. He also warned the digestion wasn’t done: “While inventory rationalisation may persist into the new year, we believe that the trends that have driven our revenue and customer expansion remain very much intact.”

Then, in mid-2023, another variable entered the equation: China’s export controls. On July 3, 2023, China announced new export control regulations on gallium and germanium materials, with implementation beginning August 1. In September, Tongmei received initial export licenses and resumed shipping gallium arsenide and germanium substrates to certain customers. But the message was clear: even when demand did return, the rules of the game could change overnight.

By the end of 2023, the revenue line made the reset undeniable. AXT fell from $141 million in 2022 to $75.8 million in 2023—nearly a 50% drop. The stabilization management wanted was still out of reach.

And yet, buried inside the downturn was the outline of a possible next act. Data center demand—especially demand tied to AI—started to show early signs of life. And AXT’s indium phosphide substrates sit right where that wave hits the supply chain: inside the high-speed optical links that connect AI servers. The business was shrinking, but the market it was trying to pivot toward was becoming one of the biggest growth engines in all of technology.

IX. Present Day & Future Crossroads (2023-2025)

As December 2025 drew to a close, AXT sat at a peculiar crossroads—pushed around by geopolitical forces it couldn’t control, while also finding itself suddenly relevant to one of the biggest technology build-outs in decades.

The stock chart reflected that whiplash. Over the 12 months ending December 2025, AXTI returned about 92.2%, far outpacing the S&P 500’s 15.6% gain. That surge came from a very specific mix: demand snapping back for indium phosphide substrates as AI and data centers upgraded their optical plumbing, a visible improvement in revenue and margins in 2025, and renewed investor confidence after export-permit approvals allowed more international shipments to move again.

The clearest inflection showed up in the third quarter of 2025. “This has been a highly active time for our business with the strong uptick in indium phosphide demand from data-center applications globally,” CEO Morris Young said.

For Q3 2025, AXT reported revenue of $28 million—up 56% from $18 million the prior quarter and up 18% from $23.6 million a year earlier. It also blew past the company’s own guidance of $19 million to $21 million.

Young explained what changed: “In Q3, our indium phosphide revenues grew more than 250 percent sequentially and reached a three-year high as we obtained export permits for a number of significant indium phosphide orders throughout the quarter. In addition, we continue to build healthy backlog for both indium phosphide and gallium arsenide materials as our industry and our customers adapt to a new normal within a rapidly changing environment.”

In other words, the AI opportunity that had been a “maybe someday” story line turned into booked orders. Q3 2025 revenue was $28.0 million, including $13.1 million from indium phosphide, driven primarily by data center and passive optical network applications. Profitability still wasn’t there, but the economics looked less dire: non-GAAP gross margin jumped to 22.4% from 8.2% the quarter before, largely on the back of that InP mix shift and volume recovery.

But AXT’s new momentum came with an asterisk: permits.

China imposed export controls on gallium arsenide in August 2023 and on indium phosphide in February 2025, aiming to restrict exports of materials associated with military applications. The practical result was blunt: an export permit now had to be secured for every customer order. Young said customers were adapting to longer lead times for permit processing—about 60 business days—and that once permits were in hand, AXT could plan manufacturing and shipping more efficiently. Still, it turned a core part of AXT’s revenue engine into a queue.

The other tradeoff was concentration. As the AI-driven recovery took hold, more of AXT’s revenue came from fewer customers. In Q3 2025, the top five customers represented 45.2% of revenue, up from 29.4% a year earlier and 30.9% the prior quarter. Two customers were now above 10%. That’s traditionally a red flag—but it also reflects the reality of AI infrastructure: a small number of hyperscalers and their supply chains drive a disproportionate share of global build-out.

Management guided to continued strength in Q4 2025, forecasting revenue between $27 million and $30 million—essentially betting that InP demand would remain strong. But the company also made the real gating factor obvious: the timing of export permits could decide whether results landed at the low end or the high end.

Even with the rebound, profitability remained just out of reach. GAAP net loss, after minority interests, was $1.9 million in Q3 2025, or $0.04 per share, compared with a net loss of $7.0 million, or $0.16 per share, in Q2 2025. The direction was encouraging. The company also had a net-cash balance sheet. But the risks were still loud: ongoing operating losses, the constant uncertainty of permit timing, and a market valuation that increasingly assumed the recovery would stick.

And hanging over everything was the unresolved Shanghai STAR Market listing for Tongmei—still in regulatory limbo, still framed as a potential catalyst, still “months away” for what felt like years. Meanwhile, U.S. industrial policy—CHIPS Act incentives and broader supply-chain realignment—created both potential upside and real danger. In a world that’s friend-shoring semiconductors, AXT’s deep China footprint can look like either a strategic advantage or a structural liability, depending on which way policy winds blow next.

Management’s posture, though, was consistent: keep pushing technical leadership in high-quality substrates, lean into the AI-driven demand for indium phosphide, and treat export controls as the environment, not an exception. The open question was the same one AXT had been trying to answer for years—just with higher stakes now: could this new wave finally translate into durable profitability, or was it simply the next cycle in a business that never stops testing its weakest links?

X. Strategic Frameworks Analysis

Porter's Five Forces

Supplier Power: MODERATE

AXT has worked to blunt supplier power by pulling parts of its supply chain in-house, including partial ownership in ten China-based companies that produce raw materials used in its manufacturing processes. But this is still a business built on specialized, high-purity inputs—especially gallium—where disruptions and pricing spikes are very real. AXT learned that the hard way in 2001, when a lack of gallium nearly affected production and it had to pay up for supply, before it established its own gallium extraction capability.

Buyer Power: HIGH

This is the force that bites the hardest. By Q3 2025, AXT’s top five customers represented 45.2% of revenue, with two customers above 10%. And these aren’t casual buyers. AXT sells to sophisticated semiconductor manufacturers who have the technical depth to qualify alternatives and the leverage to push on price, terms, and delivery. In RF especially, the fabless/foundry ecosystem concentrates purchasing power in a small group of highly capable customers who are almost always running multi-source strategies.

Competitive Rivalry: INTENSE

AXT competes in a tight field that includes major suppliers like Sumitomo Electric, Freiberger, and SICC across GaAs, InP, and semi-insulating SiC substrates. Everyone wants growth, and in a market this specialized, growth often means pushing into adjacent materials and applications—so the competitive lines keep shifting. On top of that, Chinese domestic suppliers, often supported by government policy, have come up the curve and compete aggressively on price. And from above, larger, more integrated companies like Coherent add pressure by spanning more of the value chain, from substrates into devices.

Threat of Substitutes: MEDIUM-HIGH

Substitution risk is real, even if it plays out over years rather than quarters. Silicon photonics can reduce demand for InP substrates in certain optical applications. In RF, gallium nitride is taking share from GaAs in some segments. These transitions move slowly because qualification cycles are long and reliability requirements are unforgiving—but when they move, they can permanently reshape where demand sits.

Barriers to Entry: MODERATE

Crystal growth is still hard. Producing consistent, high-quality GaAs and InP wafers takes deep process know-how and tight control. AXT built its early reputation by pioneering the commercialization of VGF technology, which it said produced substrates with lower etch pit density, lower stress, and higher mechanical strength than conventional methods. The catch is that “hard” doesn’t mean “unreachable.” China has shown that with enough investment—and enough time—new entrants can close the gap. And as competitors developed comparable capabilities, the edge AXT once enjoyed from VGF steadily narrowed.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers

Scale Economies: WEAK

AXT doesn’t have the scale of the largest competitors, and in industries like materials manufacturing, scale is a weapon: it drives lower unit costs and provides more room to invest through downturns. The compound substrate market is also not big enough to let many players reach truly optimal scale, which makes the fight for cost position even harsher.

Network Effects: NONE

Substrates don’t get more valuable as more people use them. There’s no flywheel here—just manufacturing, quality, and commercial relationships.

Counter-Positioning: HISTORICALLY PRESENT, NOW GONE

VGF was once real counter-positioning: a better approach that incumbents couldn’t easily adopt without upending their existing processes. But many of the patented technologies that underpinned that advantage were invented early—largely before 2010—and are no longer the company’s core patents and technologies today. Over time, what was differentiating became normalized.

Switching Costs: LOW TO MODERATE

Qualification creates friction. Customers don’t switch a substrate supplier on a whim, because doing so can disrupt yields and reliability. But most serious buyers qualify multiple suppliers anyway. And for less demanding applications, switching is easier still. So there’s stickiness—but not lock-in.

Branding: WEAK

AXT doesn’t sell to consumers, and its “brand” is mostly a technical reputation with engineers and supply chain managers. That matters, but it’s not a durable moat in a market where performance can be matched and price always speaks.

Cornered Resource: WEAK

AXT doesn’t control a unique input that others can’t access. Its vertical integration in China helps, but it’s not exclusive—and competitors have pursued similar strategies.

Process Power: HISTORICALLY MODERATE, NOW DIMINISHED

For years, process know-how in crystal growth was a meaningful advantage. Today, that advantage is harder to defend as competitors—especially in China—have improved quality and consistency. AXT still points to differentiated capability in achieving extremely low defect densities in InP and GaAs, a requirement for the highest-performance applications like high-speed optical interconnects for AI data centers and wireless HPTs. That differentiation remains valuable—but the distance between AXT and the pack is smaller than it used to be.

Overall Strategic Assessment

AXT used to have two real sources of power: counter-positioning through VGF and process power through manufacturing expertise. Over four decades, those advantages eroded as the industry matured and competitors—especially Chinese ones—caught up.

Today, AXT competes on a mix of customer relationships, R&D responsiveness, and technical quality in the highest-performance segments. That’s meaningful, but it’s not the same as a moat.

In its current configuration, AXT doesn’t have a durable competitive advantage that guarantees pricing power or long-term margin protection. Its path forward likely depends on one of two outcomes: finding new applications where it can rebuild technical leadership, or industry consolidation where AXT becomes part of a larger player that already has the scale to compete.

The AI-driven surge in InP demand is a window—maybe the best one AXT has had in years—to reestablish relevance in a fast-growing part of the stack. The open question is whether AXT can turn that window into a lasting position before competitors replicate the gains and the cycle turns again.

XI. Bull vs. Bear Case & Investment Thesis

The Bull Case

The bull thesis starts with a simple idea: AXT is suddenly sitting underneath two of the biggest forces in the industry—AI-driven data center build-outs, and a geopolitical reshuffling of supply chains.

On the demand side, the story in 2025 was indium phosphide. In Q3 2025, AXT’s revenue rebounded to $28.0 million, up 56% from the prior quarter. The headline driver was InP: sales into data-center customers surged more than 250% sequentially. That’s not a gentle recovery. That’s what it looks like when orders come back in size.

Bulls argue this is exactly where AXT’s strengths still matter. In the highest-performance applications, substrate quality isn’t a “nice to have.” AXT has emphasized differentiated capability in achieving extremely low defect densities in InP and GaAs substrates, which is critical for demanding uses like high-speed optical interconnects in AI data centers and wireless HPTs. As data rates climb and margins for error shrink, customers may lean harder into suppliers that can deliver consistency, not just volume.

Geopolitics also cuts both ways. In Q3 2025, export approvals enabled international InP shipments, which unlocked larger non-China markets and helped broaden the revenue base. The quarter also showed how quickly profitability can improve when volume and mix cooperate: non-GAAP gross margin rose to 22.4%. Bulls take that as evidence the model can produce competitive margins if demand holds and shipments flow.

Then there’s the market setup. The valuation bakes in plenty of doubt. AXT’s net cash position gives it breathing room—less immediate refinancing risk, more flexibility to invest—and the EV/Sales multiple of 3.34× versus a market average of 4.45× suggests there’s room for upside if growth and profitability become more consistent.

Finally, there are two potential “event” catalysts that bulls keep circling. One is the long-running Tongmei STAR Market IPO, which could unlock capital and highlight standalone value. The other is strategic optionality: AXT could be attractive as an acquisition target for a larger semiconductor materials company that wants exposure to compound substrates.

The Bear Case

The bear thesis is equally straightforward: AXT’s recent momentum may be real, but the structural problems haven’t gone away—and a few quarters of better demand can’t erase them.

Start with the gating factor that now sits in the middle of the income statement: export permits. Ongoing export-permit requirements for GaAs and InP substrates create a built-in risk of shipment delays and revenue volatility, as Q2 2025 showed. In a business where utilization and mix drive margins, delays don’t just push revenue out; they can kneecap profitability.

Bears also point to the underlying financial reality. Despite the rebound, AXT has continued to run losses, with negative operating margins and cash burn. If that persists, the company may eventually need to raise capital—diluting shareholders—especially if another demand air pocket shows up before the recovery becomes self-sustaining.

And then there’s China, the strategy that both saved the company and trapped it. With manufacturing in China, AXT is exposed to Chinese export controls, which have already disrupted operations, and potentially to future U.S. restrictions on Chinese-manufactured semiconductor materials. The same footprint that makes AXT cost-competitive also concentrates geopolitical risk in a single place.

Customer concentration adds another layer of fragility. In Q3 2025, the top five customers represented 45.2% of revenue. AI infrastructure spending is powerful, but it’s also lumpy, and it’s driven by a small number of major buyers. If that build-out pauses, or if a key customer qualifies alternative suppliers, AXT can feel the impact immediately.

Competition doesn’t make any of this easier. Larger, more integrated rivals can undercut pricing, outspend AXT in R&D, or expand capacity faster—limiting how much of the upswing AXT can keep.

Finally, the technology backdrop is not static. Silicon photonics could reduce demand for InP substrates in some applications, and GaN continues to take share from GaAs in certain RF segments. Over time, bears worry the compound substrate market could face the same commoditization pressure seen in other materials categories.

And the “catalyst” bulls cite—Tongmei’s STAR Market IPO—cuts the other way too. It has been pending for years. If it doesn’t close, or closes at a disappointing valuation, the anticipated capital and validation simply won’t show up.

Key Metrics to Watch

For investors tracking AXT’s evolution, three KPIs matter most:

1. Gross Margin Trend

This is the clearest proxy for competitive position, mix, and execution. In Q3 2025, non-GAAP gross margin improved to 22.4%. Management has indicated a mid-30% range is achievable in a healthy demand environment. If margins keep moving toward that level, it suggests the recovery is becoming real. If they stall or slide back, it’s usually a sign of weaker demand, permit-related disruption, pricing pressure, or operational problems.

2. InP Revenue as Percentage of Total

The AI data-center thesis runs through indium phosphide. InP revenue was $13.1 million in Q3 2025, primarily from data center and PON applications. Watching how much of the business InP represents helps answer two questions at once: is the AI-driven pivot working, and is AXT reducing reliance on its more traditional wireless-driven demand?

3. Customer Concentration Trends

Top five customer concentration rose to 45.2% in Q3 2025. Some concentration may be unavoidable in an AI-led build-out, but too much concentration turns growth into a single point of failure. The key is whether AXT can capture the AI wave without becoming dangerously dependent on a handful of accounts.

XII. Lessons & Playbook

AXT’s four-decade journey leaves behind a set of lessons that travel well beyond compound semiconductors.

The Double-Edged Sword of Offshoring

The China strategy delivered exactly what it promised: lower costs, proximity to Asian customers, access to raw materials, and a more competitive cost structure. For roughly fifteen years, it worked. The catch was concentration. By moving essentially all manufacturing into one country—rather than keeping meaningful U.S. capability—AXT traded flexibility for efficiency. When geopolitics shifted, that dependency stopped being a footnote and started being a constraint. The lesson isn’t “offshoring is bad.” It’s that putting any critical function in a single geography creates tail risks that don’t show up when everything is calm.

Customer Concentration Is a Ticking Time Bomb

In good times, concentration looks like focus: fewer accounts to manage, deeper relationships, cleaner forecasting. In bad times, it can become an existential threat. When a major customer stumbles, changes suppliers, or gets caught in a trade restriction, the hit isn’t linear—it’s sudden. AXT’s 2018–2020 experience showed how quickly an “efficient” customer base can turn into a single point of failure.

Technology Leadership Is Perishable

The VGF approach that gave AXT a real edge in 1986 eventually became the industry’s baseline. Many of the patented technologies that underpinned that advantage were invented early—largely before 2010—and are no longer the company’s core patents and technologies today. That’s what happens in manufacturing: even real differentiation expires unless you keep reinvesting in the next one. Competitors catch up. Processes diffuse. And what used to be special becomes table stakes.

Geopolitics Now Matters for Business Strategy

Supply chain decisions aren’t just economic optimization problems anymore. The old assumption—that trade relationships would stay stable—has proven fragile. If you have meaningful China exposure, whether through factories, suppliers, or customers, you now have to model geopolitical scenarios as seriously as you model demand. In AXT’s world, policy can be as decisive as product quality.

Cyclicality Plus Concentration Equals Potential Catastrophe

Semiconductors are cyclical by nature. Compound semiconductors can be even more so, because they’re tied to telecom infrastructure waves and consumer electronics cycles. Combine that cyclicality with customer concentration and geographic concentration, and the downside isn’t just a bad year—it can be a cliff.

Small Companies in Capital-Intensive Industries Face Structural Challenges

AXT’s competitive position would almost certainly be stronger if it were several times larger, with more manufacturing scale, a bigger R&D budget, and a broader customer base. But getting to that size in a cyclical, capital-intensive industry is brutally hard—especially as a small public company without the luxury of truly patient capital.

The China Playbook That Aged Poorly

What looked like a smart, even necessary, move in 2005—shifting manufacturing to China to win on costs—looked very different by 2019. The strategy didn’t “fail” so much as the environment changed around it. The bigger point is uncomfortable: strategies optimized for today’s conditions can become dangerous when the assumptions underneath them flip. The job of planning is to stress-test decisions against scenarios that feel unlikely, because the unlikely eventually shows up.

For Investors: Spotting the Slow Erosion of Advantage

AXT’s advantages didn’t vanish overnight—they wore down over years. But the stock price didn’t re-rate gradually. It moved violently when the accumulated disadvantages finally overwhelmed the business. The practical takeaway is that moat erosion tends to be slow in operations and fast in markets.

For Founders: Building Defensibility in Commoditizing Markets

AXT began with real innovation, and that innovation mattered. But in markets that commoditize, technical leadership alone rarely lasts. Durable advantage usually comes from some combination of continuous innovation that stays ahead, scale that changes unit economics, or switching costs that keep customers anchored. AXT struggled to build enough of any one of those before the world around it caught up.

XIII. Epilogue: What Happens Next

As 2025 closed, AXT was back in a place it knew a little too well: staring at an inflection point that could define the next decade. The last time the stakes felt this high was the telecom crash, when demand evaporated and survival became the only product that mattered.

This time, the catalyst is real. The AI data-center buildout is pulling hard on the optical stack, and that pulls on indium phosphide. CEO Morris Young described the shift plainly: "This has been a highly active time for our business with the strong uptick in indium phosphide demand from data-center applications globally. In Q3, our indium phosphide revenues grew more than 250 percent sequentially and reached a three-year high." The open question is whether that’s the start of a new baseline—or just the next sharp upswing in a business defined by cycles.

From here, three paths stand out.

Scenario 1: Muddle Through

AXT stays independent and does what it has done for years: manage through volatility. It rides AI-driven InP demand where it can, absorbs the friction of export controls, and fights constant pricing and quality pressure from larger and often better-capitalized competitors. Results swing with the cycle, profitability remains thin, and the stock continues to trade like what it is: a levered bet on a few end markets and a shifting regulatory environment. The STAR Market IPO either eventually closes—or quietly gets shelved. In the near term, this is the most likely outcome.

Scenario 2: Acquisition

A bigger semiconductor materials company decides it wants compound-substrate exposure—either to participate in AI-driven optics demand, or to add capacity, customers, and process know-how. Alternatively, a Chinese acquirer could view AXT as a way to buy validated Western technology and customer relationships. This outcome gets more plausible if AXT can show sustainable profitability, or if the STAR Market process finally crystallizes Tongmei’s valuation.

Scenario 3: Strategic Pivot or Restructuring

If the AI tailwind doesn’t translate into durable profits, the company may be forced into harder moves: exiting certain product lines, merging with a competitor, or attempting to rework its manufacturing footprint. This becomes more likely if export-control disruption persists or if Chinese competitors take share faster than AXT can defend it.

Any of these scenarios could be reshaped by broader industry currents. Silicon photonics is still a potential disruptor, especially if investments by Intel and others in silicon-based optical interconnects succeed. Quantum computing substrates are a more speculative “maybe”—a plausible long-term opportunity for compound semiconductor manufacturers, but still years away from meaningful revenue.

Policy is the other wild card. U.S. efforts to harden the semiconductor supply chain, including the CHIPS Act and related initiatives, could create opportunities to onshore more manufacturing. But AXT’s manufacturing base sits in China. Capturing those incentives would likely require major capital investment and a strategic reorientation that’s easier to describe than to execute.

And that leads to the uncomfortable truth: sometimes being a good company isn’t enough. AXT has survived for nearly four decades through genuine technical innovation and repeated reinvention. But the forces pushing on it—scale disadvantages, geopolitics, customer concentration, and commoditization pressure—can be stronger than even the best execution.

For investors, that makes AXT a high-risk, potentially high-reward bet on AI infrastructure demand, export-permit throughput, and the company’s ability to turn today’s momentum into a position it can defend. The ride, by definition, won’t be smooth: AXTI has a 60-day beta of 2.56 and volatility of 122%, compared with 26% for the market.

What we can say with confidence is simpler. AXT’s story will keep surfacing the realities that matter in modern hardware: how value accrues in supply chains, how geopolitics can rewrite business models, and why small companies in capital-intensive industries live closer to the edge than their customers ever see.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music