Axalta Coating Systems: The Science of Surfaces

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture a Saturday afternoon at a collision repair shop in suburban America. A customer paces the waiting area while a technician walks up to the car with a handheld spectrophotometer. It’s basically a scanner for paint. One quick read of that pearlescent white Honda Accord, and the device pulls up the closest match from a database built on years of real-world variations—then spits out a formula: which pigments, which metallic flake, which tints, and in what proportions, to make the repair disappear.

When the new paint finally hits the fender, it’ll wear familiar names inside the industry—Cromax, Standox, Spies Hecker. And it’ll come from a company most drivers have never heard of, even though it quietly touches an enormous share of the vehicles on the road.

That company is Axalta Coating Systems. It operates in roughly 130 countries, employs nearly 13,000 people, and serves more than 100,000 customers. With projected 2025 revenue in the mid-$5 billions, Axalta is one of the world’s major coatings specialists: the global leader in automotive refinish, and a top-tier supplier to vehicle manufacturers.

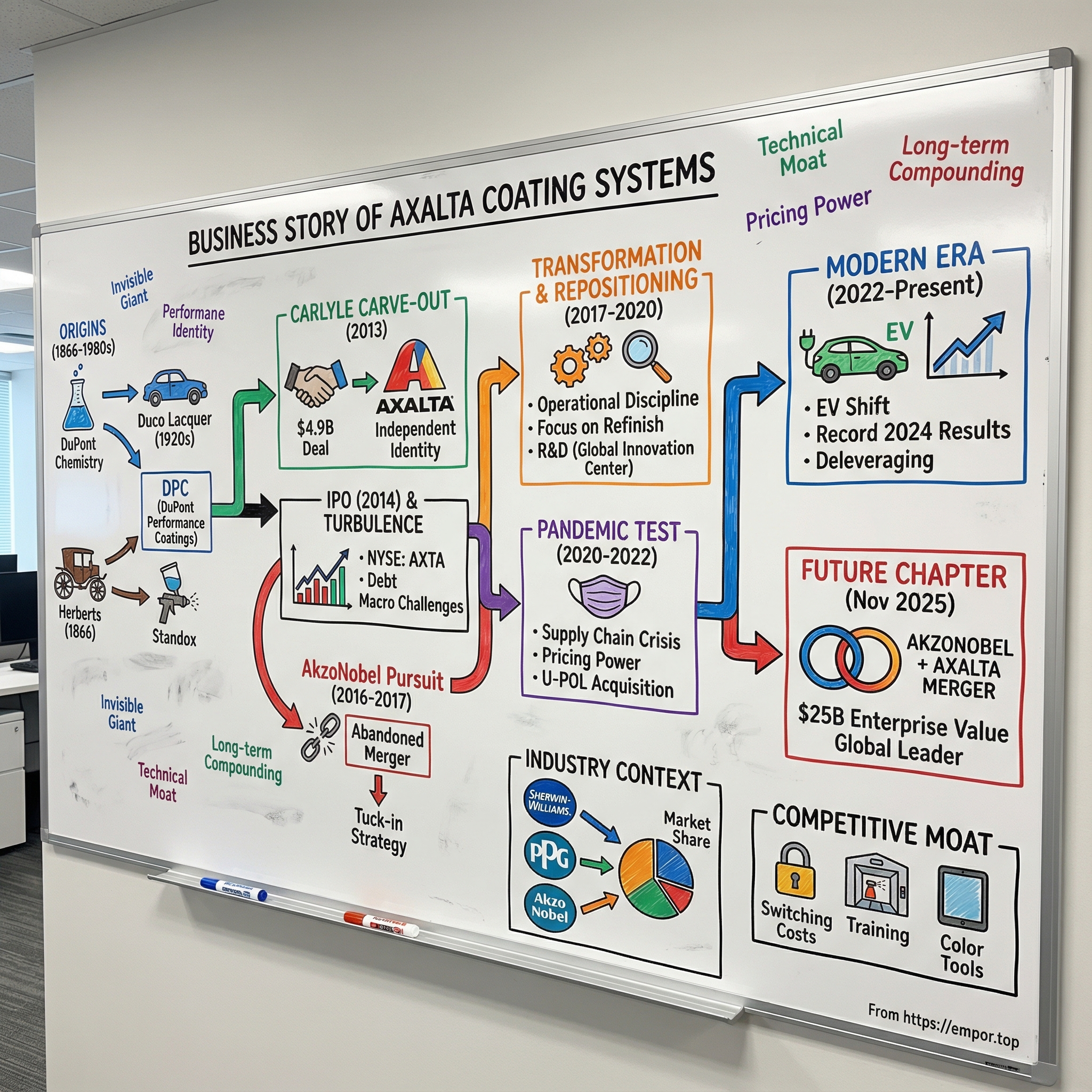

The question is: how did a coatings business that spent generations inside DuPont—one of the great American chemistry empires—turn into a financial engineering ping-pong ball, bouncing through private equity and public markets, only to re-emerge as a focused, independent industrial contender? The Axalta story is a case study in carve-outs, in what a technical moat really looks like, and in why some of the best businesses are the ones hiding in plain sight.

To see why coatings matter, zoom in on what “paint” actually means. A modern vehicle doesn’t get one coat—it gets a system. There are layers designed to bond to metal, layers built to prevent corrosion, layers for color, and layers for gloss and durability. And then there’s the aftermarket: every collision repair needs a match that blends so perfectly the human eye can’t tell where old ends and new begins.

It’s the same story outside cars. Commercial trucks, farm equipment, pipelines, appliances, electrical motors—anything exposed to weather, chemicals, heat, friction, or time needs a coating engineered for that environment. These are not simple commodities. They’re chemistry, process, and trust. Once a factory line or a body shop is calibrated around a product system—and trained on how to apply it—switching gets expensive and risky.

That brings us to the roadmap. We’ll start with Axalta’s roots deep inside DuPont, where industrial chemistry and automotive growth created a century of know-how. Then we’ll follow the big break: the carve-out, the IPO, and the era where the company’s identity got shaped as much by capital markets as by chemistry. From there we’ll track the strategic swings—especially the moment Axalta tried to bet big on consolidation—before settling into the operational playbook that defines the modern company.

Along the way, keep an eye on the recurring themes: how scale gets built in industrial markets, what private equity can unlock (and what it can distort), and why, in a business that looks “boring” from the outside, the real advantage often comes from switching costs, technical service, and relationships that compound quietly over decades.

II. Origins: DuPont's Chemistry Empire & Early Coatings (1866–1980s)

Axalta’s roots don’t start with a modern auto plant. They start with horse-drawn carriages.

In 1866, in Germany, a company called Herberts GmbH began making coatings designed to do a very specific job: protect carriage finishes from weather and from the constant sandblasting of gravel roads. This was the pre-automotive era, and the chemistry was still relatively basic—natural resins, oils, pigments—but the real magic was in the craft. Getting a finish to go on smoothly, look good, and hold up in the real world was hard-earned know-how. That German expertise would eventually become one of the foundational pillars of what turned into a global coatings business.

Across the Atlantic, DuPont had an entirely different origin story. Founded in 1802 by Éleuthère Irénée du Pont as a black powder manufacturer, DuPont spent more than a century as America’s premier explosives company. Then World War I ended, and DuPont was left with enormous nitrocellulose capacity—chemistry that had been built for munitions, but could be repurposed for a fast-growing set of civilian applications, including the motion picture film business.

At the same time, Detroit had a problem. Up through the early 1920s, the only durable, inexpensive automotive finish that could survive mass production was Henry Ford’s famous high-temperature baked black enamel on the Model T. Wealthier cars might come in hand-painted colors, but those finishes scratched easily and didn’t age well. And even Ford’s black created a bottleneck: traditional paints and varnishes took so long to dry that they clogged the back end of the assembly line. Cars would pile up, waiting for paint to cure.

That constraint—paint, not engines or chassis—was slowing down the manufacturing miracle of the early auto industry. And it created the opening for DuPont’s chemists.

The breakthrough that became Duco began on July 4, 1920, while DuPont engineers were working on motion picture film. A drum of thick nitrocellulose compound was left standing over the holiday weekend. When the team returned, they found it had turned into a liquid lacquer—something that could potentially carry pigment and form a hard coating.

It was a classic industrial moment: an accident, recognized by people who knew exactly what they were looking at.

DuPont didn’t develop automotive coatings in a vacuum. It had deep ties to General Motors—DuPont had acquired a 23% stake in GM between 1917 and 1919—and that ownership relationship helped create a steady channel for collaboration. By early 1922, the companies were adapting Viscolac, a DuPont nitrocellulose lacquer previously used to paint pencils, into something new: Duco, a finish suitable for cars.

GM first used Duco in 1923. And it wasn’t just “new paint.” It changed the economics of building cars. Duco cut the finishing process from roughly two weeks down to about two days. Instead of brushing on varnish in layer after layer—waiting, sanding, waiting again—manufacturers could spray on a quick-drying lacquer that reduced steps, slashed labor, and freed up factory space. It held up better, too: traditional varnishes chipped, cracked, crazed, and faded; Duco was dramatically more durable.

GM’s leadership understood the strategic implication immediately. Alfred P. Sloan, who became GM president in May 1923, believed that even buyers of lower-priced cars would respond to choice and style—especially if those looks lasted. The Oakland Motor Car Company proved the point by painting its 1924 touring cars with Duco in multiple two-tone combinations, with contrasting accent stripes. After a couple years of testing, GM rolled Duco across almost its entire lineup in 1924.

That was more than a manufacturing upgrade. It turned color into a marketing weapon. It helped make the annual model change era possible. Ford could famously offer “any color as long as it’s black.” GM could offer the rainbow, reliably, at scale.

From there, DuPont’s coatings capabilities grew right alongside the auto industry through the 1930s, 1940s, and beyond. And the technology kept marching: alkyd enamels in the 1930s, acrylic lacquers in the 1950s, and later generations that improved durability and productivity while meeting tightening environmental requirements.

Meanwhile, the German thread kept strengthening. Under Kurt Herberts, Herberts GmbH expanded and, in 1955, introduced Standox—an automotive finish brand that became a European staple. Over time, those European brands and DuPont’s American portfolio began to orbit the same global customers.

Eventually they combined. In 1999, Herberts merged with DuPont Automotive Finishes—technology that traced back to DuPont’s early-1920s work in Wilmington, Delaware—to form DPC: DuPont Performance Coatings. The result was a coatings division with worldwide reach, iconic brands, and serious technical depth.

But inside the sprawling DuPont empire, DPC also increasingly looked like something else: a mature, capital-intensive business delivering solid but not spectacular returns, at a time when DuPont’s center of gravity was shifting toward biotech and advanced materials.

The irony is that the very things that made DPC “mature”—its formulation expertise, color science, application know-how, and customer relationships built over decades—were exactly what made it valuable. Unlocking that value, though, would eventually require a break from the DuPont mothership.

III. The Carlyle Carve-Out: Birth of Axalta (2013)

By 2012, DuPont was at a strategic crossroads. Under CEO Ellen Kullman, the company was reorienting toward higher-growth, higher-margin businesses in agriculture, nutrition, and advanced materials. Performance Coatings was profitable, but it didn’t fit the new story. Its end markets were mature, its growth slower, and it demanded real capital.

So when DuPont announced it was exploring strategic alternatives for the division, the usual suspects showed up—private equity firms looking for a carve-out where focus and incentives could unlock value. At the front of that pack was The Carlyle Group, a buyout firm with deep experience in complex industrial separations.

In early 2013, DuPont sold the business to Carlyle Investment Management for $4.9 billion. At the time, it was described as the largest-ever carve-out of a chemical business from a diversified chemical conglomerate—and it still ranks among the biggest deals of its kind.

This was textbook private equity logic: buy an underappreciated asset from a seller with other priorities, strip away the corporate overhead, tighten operations, and then exit at a higher valuation. Carlyle funded the deal primarily with equity from Carlyle Partners V and Carlyle Europe Partners III.

But making that playbook work required more than spreadsheets. A carved-out division needs an identity, a management team, and a way of operating that doesn’t depend on the parent company. Carlyle’s choice to lead that transition was Charlie Shaver.

Shaver worked with Carlyle on its bid and was appointed chairman and CEO when the deal closed. A veteran of both commodity- and specialty-chemical private-equity deals, Axalta marked the fourth time he’d guided a chemical business from private-equity ownership to life as a public company. (He later announced he would step down as CEO in September 2018.)

Then came the clean break: the name. “Axalta” wasn’t a legacy word pulled from DuPont history. It was invented—built to stand on its own while leaving the real heritage where it mattered: in the product brands body shops and OEMs already trusted, like Cromax, Standox, Spies Hecker, and Imron.

“We’re working with an outside firm on this process,” said Mike Bennett, head of marketing for Axalta’s North America business. “We’re going back to square one to understand that now that we’re no longer part of corporate DuPont, we have an opportunity to identify and focus on our core business. It’s an opportunity to start fresh with a new name and identity.”

What did Carlyle actually buy? Not just paint, and not just a set of factories. Axalta—now a standalone company—was built on decades of technical know-how and relationships, serving more than 120,000 customers across 130 countries with a full range of coating systems.

The footprint was serious: 35 plants and seven technology centers around the world. And just as important, Axalta already had something many industrial businesses would kill for: a global training and service machine. It operated 42 training centers worldwide, where customers could get hands-on instruction in how to use Axalta products and application tools.

That training infrastructure wasn’t just “support.” It was lock-in. Every technician trained on Axalta systems built muscle memory with Axalta products. Every body shop workflow wired itself into Axalta tools and color data. Switching suppliers wasn’t a simple procurement decision—it meant retraining, revalidating processes, and risking quality problems until the new system settled in.

Operationally, Axalta developed, manufactured, and sold coatings and application tools to automobile repair body shops and original equipment manufacturers in the automotive and heavy-duty truck markets. And it did it behind brands that carried real weight in the trade: Standox®, Spies Hecker®, Cromax®, and Imron®.

Those names weren’t interchangeable. Standox traced back to Germany in 1955. Spies Hecker brought its own German heritage. Cromax stood for premium waterborne technology. Imron was synonymous with commercial truck and fleet coatings. Together, they were a portfolio built over generations—each brand aimed at a different customer set, price point, and performance need.

Carlyle moved fast. The first step was cost optimization: removing DuPont corporate overhead, rationalizing the footprint, tightening procurement. But the bigger prize was operational discipline—better working capital management, more structured pricing, and sharper commercial execution.

There was a cultural shift, too. A division inside DuPont could afford to move at big-company speed. A standalone company owned by private equity couldn’t. Axalta needed a new level of accountability, faster decision-making, and a more explicit obsession with the customer. “In addition to driving performance and excellence, one of our greatest strengths is the systems-based approach we take with our customers,” said John G. McCool, President of Axalta Coating Systems. “Along with coatings, we provide customers a full spectrum of tools and services to help them use our products effectively.”

From day one, though, the destination was obvious. Private equity doesn’t buy companies to hold them forever. It buys them to transform them—and then sell. For Axalta, that meant proving it could stand alone, polishing the story, and getting ready for the public markets.

IV. Going Public: The 2014 IPO & Post-IPO Turbulence (2014–2016)

Barely twenty months after buying the business from DuPont, Carlyle was ready to see what public markets would pay for the newly christened Axalta. In November 2014, it launched an IPO that became one of the year’s biggest private equity exits.

Axalta raised $975 million by selling 50 million shares at $19.50 each—right in the middle of the proposed range. The deal was also upsized from the original plan to sell 45 million shares, a sign that investor demand was there. Axalta began trading on November 12, 2014 on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker “AXTA.”

But the structure told you exactly whose moment this was. Axalta itself didn’t take in the proceeds. This was a secondary offering: existing shareholders sold shares, and the cash went to them—primarily Carlyle—while the company got the benefits of being public: liquidity, visibility, and a paved road for future exits. The underwriting roster was the full Wall Street A-list: Citi, Goldman Sachs, Deutsche Bank, J.P. Morgan, BofA Merrill Lynch, Barclays, Credit Suisse, and Morgan Stanley.

On paper, the pitch was clean. Axalta was a global coatings leader, with about 90% of revenue coming from markets where it held the #1 or #2 position. Its crown jewel was automotive refinish, where it held the #1 global spot with roughly a quarter of the market. That kind of share doesn’t happen by accident in a technical business with high switching costs.

The moat story had receipts, too. As of June 30, 2014, Axalta held more than 1,300 issued patents and over 500 pending patent applications, plus more than 250 trademarks. And beyond what could be filed and counted, it had what coatings companies really run on: proprietary formulation know-how and process expertise built up over decades.

Then you flipped to the balance sheet and saw the catch. As of June 30, 2014, Axalta had $350 million in cash—and $3.901 billion of debt. With roughly $800 million of annual EBITDA, leverage was close to five turns. That’s normal in LBO land. It’s a lot less comfortable when you’re a newly public company trying to convince long-only investors that you’re a steady compounder, not a leveraged bet on the auto cycle.

Axalta’s public debut did what it was supposed to do for Carlyle. The firm sold down and fully exited its remaining stake in 2015. And the broader scoreboard was hard to argue with: critics had said Carlyle overpaid in 2013; within three years, it had turned the deal into one of its most profitable wins.

For public shareholders, though, the experience was more complicated. The 2015–2016 China slowdown hit emerging market demand. Auto production volatility made results feel less predictable. And a strong U.S. dollar turned international revenue into a headwind when translated back home. Investors started asking an uncomfortable question: was Axalta a differentiated coatings leader—or just a mature industrial wrapped in a lot of debt?

In April 2015, Berkshire Hathaway invested $560 million in Axalta, a high-profile vote of confidence that briefly lifted sentiment. But even Buffett’s backing couldn’t fully shield the stock from macro worries about automotive exposure and emerging markets.

Through it all, the company kept running the playbook. Pricing discipline stayed intact. Cost initiatives kept delivering. Working capital improved. Carlyle’s operating mindset—tighter execution, fewer excuses—carried over into Axalta’s first chapters as a public company.

V. The AkzoNobel Pursuit: Axalta's Big Bet That Wasn't (2016–2017)

By the mid-2010s, coatings looked like one of those industries practically begging to be consolidated. A handful of global players sat on top, but beneath them were hundreds—maybe thousands—of regional specialists. If you could combine two giants, the promise was obvious: squeeze out costs, spread R&D across a bigger base, and walk into negotiations with suppliers and big customers from a position of even greater strength.

Axalta stepped into that chess match just as it was getting loud.

The headline drama came from PPG, which went after AkzoNobel with an unsolicited bid in 2017. AkzoNobel’s board resisted, Dutch stakeholders raised alarms about jobs and national interests, and regulators circled. After three attempts, PPG walked away.

Once that door shut, the spotlight swung to other pairings. Axalta and AkzoNobel confirmed they were in discussions about a potential combination—talk that, if it worked, would have created a coatings company of enormous scale. On October 30, AkzoNobel released a short statement acknowledging the conversations.

On paper, the fit seemed clean. Axalta was strongest in automotive refinish and mobility coatings. AkzoNobel brought leadership in decorative paints and a broad performance coatings franchise spanning marine, protective, and industrial markets. Together, they’d be more diversified, less dependent on any one customer set, and broader geographically.

Charlie Shaver framed the industry structure in a way that made the consolidation thesis feel inevitable: "Coatings is a $130 billion marketplace. There are only ten players of any size, and still hundreds if not thousands of coating players in each subsector. The reality is that only a few segments are actually consolidated, such as aerospace and OEM coatings, the ones where you deal with very large global customers with global requirements."

He also made it clear that nobody was sitting still. "Everybody is playing the chess board. My view is there will be one or two large consolidation steps in the next two years, but I can't tell you which they will be."

But “inevitable” doesn’t mean “easy.” The negotiations ran into the classic deal-killers: different cultures, mismatched views of valuation, governance questions, and the ever-present shadow of regulatory uncertainty. Eventually, Axalta said the talks were over. The company confirmed it had ended discussions around what it described as a merger-of-equals-style transaction with AkzoNobel’s Paints and Coatings business because the two sides couldn’t reach mutually acceptable terms. Axalta added it would continue pursuing other value-creating alternatives.

Shaver put a fine point on it: "After pursuing a potential combination of Axalta and Akzo, we concluded we could not negotiate a transaction on terms that meet our criteria."

That wasn’t Axalta’s only near-miss over the years—it also found itself in discussions with other would-be partners, including Nippon Paint. But the AkzoNobel episode became a turning point in what Axalta would do next.

Instead of swinging for a transformative merger, Axalta leaned back into what it could control: tightening execution, protecting its leadership in refinish, and expanding through smaller, lower-risk acquisitions. Shaver pushed an aggressive tuck-in program in industrial coatings, growing that segment to around $1 billion in annual sales.

He described the hunting ground like a dealmaker who finally liked the odds: "There our pipeline is full, and we have more opportunity than we have capital. In the 15 acquisitions we've done so far, we haven't paid a double-digit multiple yet, and on top of that, we typically find we can substantially increase their margins through sourcing and operations improvements."

It was a quieter strategy than a mega-merger. But it fit Axalta better: smaller deals that added products, customers, and capabilities—without the integration risk, political blowback, and valuation baggage that came with trying to swallow another giant.

VI. Transformation & Repositioning (2017–2020)

After the AkzoNobel swing-and-miss, Axalta’s next chapter wasn’t defined by a blockbuster deal. It was defined by leadership—and by a decision to win the unglamorous way: tighter execution.

In late 2018, the company turned to a familiar operator. Axalta announced that its board had named Robert Bryant Chief Executive Officer on a permanent basis, effective immediately. He had been serving as interim CEO since October 2018.

Bryant was continuity with a clear tilt toward financial discipline. He’d been Axalta’s CFO since 2013—there from the carve-out through the IPO and the post-IPO turbulence—before stepping into the top job. His background blended Wall Street training with the day-to-day mechanics of running a global industrial business. “Axalta's tremendous progress in recent years has enabled the company to review a range of strategic alternatives from a position of strength,” Bryant said, “which I strongly believe is the best course of action for Axalta and its shareholders, customers and employees.”

In practice, that meant a strategic reset: less emphasis on M&A as a headline strategy, and more emphasis on operational excellence and focus. Portfolio optimization moved to the center—put more resources behind the businesses with the best returns, and divest or de-emphasize what didn’t fit. And within that, refinish got the attention it deserved. It wasn’t just Axalta’s largest franchise; it was the most defensible one, anchored by training, tools, and relationships that competitors couldn’t easily pry loose.

Axalta also worked to address a worry that had followed it since the IPO: exposure to China and the volatility that came with it. The company stayed committed to the world’s largest auto market, but it pushed harder to diversify growth initiatives toward the Americas and Europe—regions where currency swings and competitive dynamics felt more manageable.

At the same time, Axalta doubled down on the part of coatings that never shows up in a headline but decides who wins over time: technology. Investment accelerated in waterborne coatings, faster-curing systems, and digital tools. As environmental regulations tightened restrictions on volatile organic compounds (VOCs), the industry faced a forcing function. Companies that could deliver high performance with lower emissions didn’t just comply—they gained an edge.

That push showed up in bricks and mortar, too. On November 7, 2018, Axalta held the grand opening of a new research and development center at the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard: the Global Innovation Center. Axalta described it as the largest coatings research and development center in the world.

The underlying opportunity in refinish remained especially attractive. Vehicle fleets were aging, which meant more cars staying on the road long enough to need collision repair. And repair economics increasingly favored restoring vehicles rather than replacing them—exactly the scenario where high-quality refinish coatings matter. Meanwhile, consolidation among body shop operators created bigger, more sophisticated customers who valued what Axalta was built to provide: training, technical support, and industry-leading color-matching capabilities.

So Axalta leaned into customer intimacy. It expanded training, enhanced technical support, and built deeper body shop partnership programs. And with every additional touchpoint, the switching costs got stronger. A technician trained on Standox, using Axalta color tools, and integrated into Axalta’s ordering and supply systems wasn’t just buying paint. They were buying a workflow—and walking away from that workflow would create real friction.

Underneath it all was a simple mandate: clean up the capital structure and make the model sturdier. Deleveraging became a priority, steadily reducing the debt load inherited from the LBO era. Margin initiatives targeted both gross margin gains—through pricing discipline and better mix—and operating leverage through cost control. As cash generation improved, Axalta regained something it hadn’t always had since becoming independent: real flexibility in how it could invest, compete, and allocate capital.

VII. The Pandemic Test & Supply Chain Crisis (2020–2022)

The COVID-19 pandemic hit in early 2020 like a stress test no boardroom would ever volunteer for. Auto plants went dark. Miles driven fell off a cliff as cities locked down. And the global supply chain did that surreal thing where it broke, restarted, broke again, and then restarted at twice the cost.

For Axalta, the immediate impact was blunt. In 2020, net sales fell to $3,737.6 million, down 16.6% year over year, including a 0.8% hit from currency. On a constant-currency organic basis, sales declined 15.2%, driven almost entirely by lower volume—about 15%—with price and mix essentially flat.

And yet, the headline decline didn’t capture what was happening inside the company. Axalta moved quickly to protect margins and cash: tightening costs, adjusting operations, and leaning into the parts of the portfolio that recovered faster. CEO Robert Bryant pointed to “rapidly improving demand across many industrial coatings segments” and the benefits of the cost actions taken during 2020 to blunt the volume shock. In the fourth quarter alone, he said Axalta delivered about $50 million of cost savings, including $25 million of temporary savings, and that the benefits were coming through ahead of expectations.

The subtext was important: this wasn’t just survival. It was proof the business could bend without breaking. As Bryant put it, 2020 brought “staggering challenges,” but Axalta “demonstrated the resilience of [its] business model” through coordinated execution across its global team.

The crisis also clarified something investors sometimes forget until the world goes sideways: refinish behaves differently than OEM production. When factories shut, OEM volumes evaporate. But the aftermarket doesn’t disappear; it wobbles and then returns. People still need to get to work, errands still happen, accidents still happen, and body shops still need paint. And the installed base—the roughly 1.4 billion vehicles already on the road globally—doesn’t go away just because new-car builds slow down.

By 2021, demand was coming back, but it came back messy. Supply chains stayed constrained, and raw material inflation became its own second wave of disruption. Mobility Coatings, in particular, got squeezed by “unprecedented customer production impacts,” largely from semiconductor shortages that choked OEM output and dragged on through the year.

Even in that environment, Axalta’s mix showed why it had invested so heavily in refinish and service-driven businesses. Volumes were positive in Refinish, Industrial, and Commercial Vehicle, and price and mix improved across all four end-markets. Management also highlighted something that matters a lot in coatings: price capture. This inflation cycle, Axalta moved faster than it had in the 2017–2018 run-up, and the company expected to be fully offsetting cost inflation by early 2022 on a run-rate basis.

That ability to push pricing through—while customers were dealing with their own chaos—was a real competitive tell. Through 2021 and 2022, key inputs like titanium dioxide, resins, and solvents surged. In many industries, that kind of spike turns into margin compression and finger-pointing. In coatings, it becomes a referendum on switching costs and trust. If a body shop or a factory line is calibrated around your system, “cheaper” isn’t cheaper if it risks quality problems, rework, or downtime. Axalta’s pass-through success validated that its differentiation wasn’t a marketing line; it was embedded in customer workflows.

The demand picture underneath remained strange but supportive. Retail auto demand was solid—often strong when adjusted for thin dealer inventory—but that strength didn’t translate into higher Light Vehicle volumes for Axalta because OEM production was still constrained by chips and other bottlenecks. Commercial Vehicle demand, especially in North America trucks and recreational vehicles, held up better and continued to support production rates.

Even in the middle of this turbulence, Axalta kept playing offense with the kind of deal that fit its post-Akzo strategy: a tuck-in that deepened the core. The company completed its acquisition of U-POL Holdings Limited, a UK-based supplier of paint, protective coatings, and accessories for the automotive aftermarket. Axalta agreed to buy U-POL from Graphite Capital Management LLP and other holders for £428 million (about $590 million).

U-POL, founded in 1948 and based in the United Kingdom, brought a portfolio that sat adjacent to Axalta’s refinish strengths: fillers, coatings, aerosols, adhesives, and other repair and paint-related products, plus aftermarket protective coatings. The logic was straightforward. It strengthened Axalta’s global refinish leadership, expanded its reach into mainstream and economy refinish segments, and gave U-POL a bigger runway by plugging it into Axalta’s sales and distribution channels.

Meanwhile, ESG evolved from something the industry had to manage into something it could compete with. Low-VOC and waterborne technologies weren’t just regulatory checkboxes; they increasingly matched what customers wanted and what OEMs demanded from their supply chains. In a world where sustainability requirements were tightening, coatings companies with credible technology and track records didn’t just stay compliant—they gained an advantage.

VIII. Modern Era: Electrification, Sustainability & the Next Chapter (2022–Present)

The electric vehicle revolution poses an existential-sounding question for automotive coatings suppliers: what happens to paint demand when the internal combustion engine disappears?

For Axalta, the answer is calmer than the question. EVs still need coatings—sometimes even more demanding ones, given premium finishes, tighter tolerances, and new design cues. And the company’s biggest franchise, refinish, doesn’t care what’s under the hood. If a Tesla, Toyota, or Rivian gets clipped in a parking lot, it still needs a color match that disappears under daylight.

The shift does change the technical problem set. New substrate materials, new manufacturing processes, and evolving factory requirements force constant iteration in formulation and application. But none of it removes the underlying need for coatings that protect, perform, and look perfect.

By 2024, Axalta’s recent operating playbook was showing up clearly in results. “Axalta's 2024 financial results were exceptional. We delivered record net sales and Adjusted EBITDA for the fourth quarter and full year in a challenging macro environment,” said Chris Villavarayan, Axalta's CEO and President.

The company reported record net income of $391 million, up 45% year over year, with net income margin rising to 7.4%. Full-year Adjusted EBITDA reached a record $1,116 million, translating to an Adjusted EBITDA margin of 21.2%. Full-year net revenue also hit a record $5.3 billion, helping drive those record profits.

Villavarayan credited the core franchises and execution: “Consistent outperformance in Refinish and Light Vehicle and excellent execution across the company, resulted in an Adjusted EBITDA margin of over 21% as we continue down the path to delivering against our commitments outlined in the 2026 A Plan.”

Just as important as the income statement was the balance sheet. Years of deliberate deleveraging had brought Axalta’s net leverage down to 2.5x at quarter-end, versus 2.9x at the end of 2023. Put differently: from close to five turns of leverage around the time of the IPO to 2.5x a decade later, Axalta had materially strengthened its financial footing.

Then, in November 2025, Axalta made a move that would have seemed like science fiction back when the AkzoNobel talks collapsed in 2017.

Akzo Nobel N.V. and Axalta Coating Systems Ltd. announced they've entered into a definitive agreement to combine in an all-stock merger of equals, creating a premier global coatings company with an enterprise value of approximately $25 billion. The combination brings together two coatings industry leaders with complementary portfolios of highly regarded brands to better serve customers across key end markets and enhance value for shareholders, employees and other stakeholders. Anchored in both companies' proud histories and broad expertise, the combined business will have a highly attractive financial profile, industry-leading innovation capabilities and a balanced global footprint spanning over 160 countries.

The context for just how big this would be showed up in the industry league tables. In PCI's 2025 Global Top 10 Rankings, AkzoNobel finished at #3 with $11.6 billion in coatings sales and Axalta came in at #6 with $5.3 billion.

Together, the companies projected a combined $17 billion revenue business, with an enterprise value of about $25 billion. The deal also carried a classic consolidation promise: approximately $600 million in cost synergies, meant to support strategic priorities and capital allocation.

Leadership, too, reflected the “equals” framing. Current AkzoNobel CEO Greg Poux-Guillaume was slated to become CEO of the combined company; current Axalta CEO Chris Villavarayan would serve as Deputy CEO; and Axalta’s SVP and CFO Carl Anderson would become CFO of the combined company.

“This is a combination that we've looked at multiple times in the past, but this is also a combination that the markets have been asking for for a long time,” Poux-Guillaume said.

If it closes as planned, the merger would mark a true step-change for Axalta: from a focused specialist with a crown-jewel refinish franchise into a broader, more diversified coatings heavyweight—one that would reshape the competitive picture at the top of the industry.

The companies said they expected the transaction to close in late 2026 to early 2027, subject to approval by shareholders of both AkzoNobel and Axalta, receipt of required regulatory approvals, and authorization for the combined company's shares to be listed on NYSE.

IX. The Coatings Industry Deep Dive

To understand Axalta’s competitive position, you have to understand the market it competes in. From the outside, “paint” feels like a commodity—something you grab off a shelf. Up close, coatings is a layered, technical industry with very different business models hiding under the same umbrella.

At the top of the global leaderboard sits Sherwin-Williams. In 2024, it posted $18.4 billion in revenue and has long held the strongest position in North America, where it reached about 28.5% share in 2019.

Right behind it is PPG Industries, another American heavyweight, with roughly $18.2 billion in 2024 revenue.

Then there’s AkzoNobel, headquartered in the Netherlands. It ranked third globally by revenue, held about 6.9% global market share in 2020, and led Europe with more than 16% share.

But those headlines can mislead, because “coatings” isn’t one market. It’s several markets stitched together, each with its own economics, customer relationships, and competitive rules:

Decorative/Architectural Coatings: Consumer-facing paint for homes and buildings. It’s highly competitive, with meaningful DIY demand. Sherwin-Williams and PPG dominate in North America, while AkzoNobel’s Dulux brand leads in many international markets.

Industrial Coatings: Protective coatings for equipment, infrastructure, and manufactured goods. Requirements vary wildly by application, which is why this area tends to be more fragmented, with many specialists.

Automotive OEM Coatings: Coating systems sold directly to vehicle manufacturers. The customer base is concentrated, and those customers have real leverage. It also requires major capital investment, often tied closely to auto assembly plants and their processes.

Automotive Refinish Coatings: The collision repair and restoration market. This is Axalta’s core franchise, with a fragmented customer base of body shops—and, crucially, high switching costs driven by tools, training, and workflow integration.

Refinish is where you can see why coatings can be a “good” business. A body shop doesn’t just buy paint the way it buys paper towels. Over time, it builds an operating system around a supplier:

- Spray booths and mixing equipment are set up and calibrated around specific product lines

- Technicians train and get certified on a particular system

- Color-matching databases and tools get embedded into daily workflow

- Ordering ties into inventory habits and delivery routines

- Technical support relationships form after years of solving problems together

So when a competitor shows up offering a lower price, the shop has to weigh that against the risk and disruption of ripping out the system it already knows works. Switching isn’t just a procurement event. It’s retraining, recalibration, and a period where quality can slip—exactly what a body shop can’t afford when its reputation depends on the paint being invisible.

That dynamic shapes the competitive set in refinish. The major players include PPG Industries, Axalta Coating Systems, Sherwin-Williams, and AkzoNobel—each with established product lines and technical capabilities, and each fighting for loyalty in a business where relationships and workflow matter as much as the coating itself.

Then there’s the other piece people underestimate: raw materials. Titanium dioxide (TiO2) drives opacity and whiteness and is typically the single largest cost input in many coatings. Resins provide the binding chemistry. Solvents make application possible. Specialty additives deliver everything from corrosion resistance to scratch performance to the “feel” of a finish.

When those inputs spike or get scarce—as they did during the supply-chain chaos of the early 2020s—the winners aren’t just the companies that source well. They’re the companies that can keep product flowing, maintain quality, and still push pricing through. In coatings, supply-chain management and pricing power aren’t back-office details. They’re competitive weapons.

X. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

Step back from the chemistry, the mergers, and the macro swings, and Axalta starts to look like a clean case study in how industrial value actually gets created. A few lessons jump out:

The Private Equity Transformation: When Carlyle bought the business from DuPont for $4.9 billion in 2013, plenty of people said it overpaid. Three years later, Carlyle had turned it into its second-biggest profit ever. Not because coatings suddenly became sexy—but because the playbook was executed well: take a carved-out asset, strip out conglomerate overhead, sharpen operating discipline, align incentives, and sell into a market willing to pay up for focus.

From Corporate Division to Independent Company: The real work in a carve-out isn’t the deal; it’s the week after. Leaders who used to run a division become true owners of outcomes. Shared services vanish, forcing decisions about what to build internally and what to outsource. Governance changes, too—from being one unit inside DuPont to a public-company board with independent fiduciary responsibilities. If you get that transition right, you don’t just survive the separation—you come out with a tighter, faster, more accountable business.

The Power of Focus: Axalta’s biggest strategic unlock wasn’t a mega-merger. It was deciding to stop chasing one and win where it already had an edge. As the company put it: "We're 152 years old this year, but as Axalta, we're only in our fifth year, and we're still at an early stage of our journey. The first three years were consumed with the separation, the IPO, and Carlyle's exit. We're really only in the last two-and-a-half years starting on the journey to implementing our growth strategies." In other words: once the financial and organizational turbulence settled, the company could finally do the blocking-and-tackling that compounds.

Technical Expertise as Moat: Formulation chemistry isn’t glamorous, but it’s real defense. Patents help, but the deeper moat is what can’t be neatly written down: proprietary know-how, process expertise, and teams that have solved the same customer problems a thousand different ways. You can’t lever that up in a spreadsheet.

Customer Intimacy in B2B: Training programs, technical support, and color-matching systems aren’t “nice-to-haves.” They’re how switching costs get built. Every technician trained on your system, every shop that standardizes its workflow around your tools, every problem solved together in the field makes the relationship stickier—and makes a competitor’s lower price less persuasive.

Navigating Cyclicality: Axalta’s portfolio mix matters. OEM automotive is cyclical and concentrated. Aftermarket refinish is steadier and more fragmented. That balance acts like a hedge, and the pandemic era made the point: when new-car production gets hit, the installed base of vehicles still needs repairs.

Pricing Power in "Commoditized" Markets: From far away, coatings look like commodities—just chemicals in cans. Up close, Axalta’s ability to push through raw material inflation showed the truth: performance requirements, service, and workflow lock-in create pricing power, even in an industry that looks mature on paper.

XI. Analysis: Porter's Five Forces & Hamilton's Seven Powers

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Competitive Rivalry (Moderate-High): Coatings is an oligopoly at the top—and a street fight underneath. Sherwin-Williams, PPG, AkzoNobel, BASF, and Nippon Paint battle globally, while regional specialists scrap for local share. In the more price-sensitive corners of the market, competition gets brutal. Where performance, certifications, and application support matter, the rivalry shifts from pure price to service, reliability, and technical differentiation.

Threat of New Entrants (Low): This is a hard industry to “just enter.” The chemistry is learnable, but the know-how that matters is accumulated—years of formulation tweaks, field failures, and customer-specific requirements. Automotive coatings also come with long qualification cycles and heavy regulatory and customer testing. And then there’s the relationship layer: training, technical support, and workflow integration take years to build. Even with capital, a new entrant faces a long, expensive climb before it can compete credibly.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers (Moderate): Key inputs like titanium dioxide are concentrated among a handful of producers, which gives suppliers leverage—especially during shortages. But coatings formulators aren’t helpless. They can adjust formulations, qualify alternates over time, and, critically, pass through inflation when customer relationships and switching costs support it. Supplier power is real, but it’s not absolute.

Bargaining Power of Buyers (Segment-Dependent): Buyer power depends on who the buyer is. Automotive OEMs are large, sophisticated, and concentrated; they can negotiate hard and multi-source. Body shops are fragmented and individually small, but they’re not powerless—if a supplier underperforms, they can switch. The catch is that switching is painful once a shop is trained on a system and tied into tools and color data. In refinish, the relationship and workflow integration often matter as much as the invoice price, which meaningfully tempers buyer power.

Threat of Substitutes (Low-Moderate): There’s no world where cars and equipment simply stop needing surface protection and aesthetics. What does change is how coatings get applied and what they’re made of—powder coatings, UV-cured systems, and waterborne formulations can shift share within the category. The disruption risk is real at the technology level, but it doesn’t eliminate the underlying demand for coatings.

Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis

1. Scale Economies (Present but Not Overwhelming): Scale helps in manufacturing efficiency, spreading R&D, and running global distribution—but coatings isn’t software. It doesn’t naturally collapse into one winner. Plenty of smaller specialists survive by serving niches, geographies, or specific performance needs.

2. Network Effects (Weak): The closest thing to network effects shows up in color-matching ecosystems: more real-world readings and formulas can improve the database. But it’s modest—helpful, not decisive in the way a true network business can be.

3. Counter-Positioning (Limited): The big players broadly know the playbook: technical service, training, product systems, and distribution. Axalta’s approach is strong, but it isn’t structurally impossible for competitors to pursue similar strategies.

4. Switching Costs (STRONG—Axalta's Key Power): This is the heart of Axalta’s advantage. In refinish, customers don’t just buy a can of paint—they adopt a system. Shops invest in equipment calibration, technician training and certification, color tools and databases, and supplier support relationships. Switching means disruption, relearning, and risk of quality issues. That friction is exactly what makes refinish such an attractive business when you’re the incumbent.

5. Branding (Moderate-Strong in Refinish): In body shops, brands like Cromax, Standox, and Spies Hecker carry real credibility with professionals. In OEM, branding matters less than meeting specs, passing tests, and executing reliably at scale.

6. Cornered Resource (Moderate): Patents and formulation IP help, but the bigger “resource” is harder to count: proprietary know-how, accumulated color data, and long-built customer relationships. These aren’t monopolies, but they are assets that take a long time to replicate.

7. Process Power (Moderate): Application expertise and technical service aren’t just add-ons; they’re capabilities built through repetition and field experience. Over time, that operational muscle can become a differentiator that’s difficult for rivals to match quickly.

The Verdict

Axalta’s primary moat is switching costs in automotive refinish. Supporting advantages include branding in the trade, scale benefits in production and R&D, and cornered resources like accumulated color data and customer relationships. The company looks strongest where workflows and relationships drive stickiness—refinish—solid in mobility OEM, and more mixed in industrial, where fragmentation and application-specific competition are higher.

The weak points are the ones you’d expect: exposure to raw material volatility, the need to keep up with evolving coating technologies, and concentration risk in OEM-heavy segments. A potential combination with AkzoNobel would likely improve diversification and scale, but it would also introduce the classic integration challenge: making the deal work in the messy reality of plants, people, customers, and product systems.

XII. Bear vs. Bull Case

Bull Case

Refinish Market Stability: The world’s vehicle fleet keeps getting older, and older vehicles get repaired. That’s good for collision shops, and it’s great for the coatings supplier sitting inside their workflow. In the U.S., the average car is now more than 12 years old—meaning more dents, more fender benders, and more repaint work, regardless of whether the next car someone buys is gas or electric.

Pricing Power Demonstrated: The inflation shock of 2021–2022 was a real-world test of the “switching costs” thesis. Axalta proved it could push through higher raw material costs instead of simply eating them. That’s not just good execution—it’s evidence the relationship-and-system moat in refinish is real.

Margin Expansion Runway: Axalta has already climbed from the post-LBO era into the low-20s in Adjusted EBITDA margins, and that didn’t happen by accident. With continued cost discipline and a mix shift toward higher-margin products and services, there’s a credible path to further improvement—especially if the company keeps tightening operations instead of chasing splashy distractions.

Sustainability Tailwinds: Regulations aren’t getting looser, and customers aren’t getting less demanding. Low-VOC, waterborne, and more sustainable formulations increasingly move from “nice-to-have” to “required.” Axalta’s investment in R&D and next-generation systems positions it to benefit as environmental standards tighten.

Geographic Growth: In emerging markets—India, Southeast Asia, and Latin America—the long-term arc is more vehicles on the road and a more developed repair ecosystem. As collision repair infrastructure professionalizes, suppliers with training, tools, and trusted systems can take share.

Free Cash Flow Generation: As the business has stabilized and delevered, the model has become more cash generative. Strong free cash flow gives Axalta options: reinvest in innovation, pursue tuck-ins, or return capital to shareholders—without needing perfect macro conditions.

Merger Value Creation: If the AkzoNobel combination closes and is executed well, it could reshape Axalta’s scale, diversification, and cost structure. The synergy opportunity is meaningful—but only if the integration is handled with discipline.

Bear Case

Automotive Cyclicality: OEM exposure is the obvious fault line. When global vehicle production slows—because of recession, supply-chain problems, or demand shocks—earnings volatility follows. Refinish helps stabilize the ride, but it doesn’t eliminate the cycle.

EV Uncertainty: Today, EVs don’t look like a demand killer—paint is still paint, and accidents are still accidents. But over the long run, EV-driven changes in materials, manufacturing processes, and design could create technical curveballs that are harder to predict than the industry wants to admit.

Raw Material Volatility: Coatings are only as profitable as your ability to manage inputs. If titanium dioxide, resins, or solvents spike again—and price increases lag—margins can compress fast. Supplier concentration in TiO2 keeps this risk permanently on the dashboard.

Technological Disruption: The barriers to entry are high, but they’re not magical. New chemistries, new application methods, or shifts like powder and UV-cure could change the competitive map. Disruption here is more likely to be “slowly, then suddenly” than a clean, gradual transition.

Competitive Pressure: PPG and Sherwin-Williams are large, well-capitalized, and aggressive. In contested segments, they can spend, discount, or bundle across portfolios in ways that make it harder to defend share and margins.

Limited Growth: Even with strong execution, parts of this business will look like mature-industry growth: steady, but not explosive. If investor expectations drift toward “this should be a high-growth story,” the stock can suffer even if operations remain solid.

Integration Risk: A merger with AkzoNobel could be strategically powerful—and operationally brutal. Synergies are easy to announce and hard to realize, especially when you’re combining global footprints, cultures, and customer-facing systems where disruption can cost you share.

Key KPIs to Watch

1. Refinish Volume Growth and Market Share: This is the crown jewel. Watch whether Axalta is winning and keeping body shops, how volumes trend relative to collision repair activity, and whether share is holding or slipping in key regions.

2. Adjusted EBITDA Margin: Margins are the scoreboard for pricing power, mix, and cost discipline. Expansion signals execution and competitive strength; compression usually means either cost pressure, competitive intensity, or both.

3. Net Leverage Ratio: Leverage determines how much room management has when the cycle turns—or when a big strategic move appears. Continued deleveraging adds resilience and flexibility; rising leverage is a warning sign that the risk profile is changing.

XIII. Epilogue & Reflections

The Axalta story stretches across more than 150 years: from German carriage finishes in 1866, to DuPont’s chemistry-driven color revolution in the early auto era, to a private-equity carve-out that turned a “mature division” into an independent competitor—and now to a merger that, if it closes as planned, will reshape the top tier of global coatings.

In fact, the Akzo Nobel–Axalta tie-up represents one of the most consequential shifts in the industry in years—on the scale of the big combinations that periodically redraw the coatings map, like when Sherwin-Williams bought Valspar.

And it’s worth stepping back and asking: why does any of this matter?

Because coatings are invisible infrastructure. Every vehicle you pass on the highway. Every commercial truck delivering goods. Every piece of industrial equipment on a factory floor. Every pipeline carrying energy. Coatings protect them from corrosion, chemicals, weather, abrasion, and time—and they do it while meeting the human requirement that everything also has to look right. You don’t notice coatings when they work. You only notice them when they fail.

That’s why the coatings industry is such a clean microcosm of industrial competition. Consolidation rewards scale, but it doesn’t erase the need for specialization. Technical moats don’t come from slogans; they come from formulation know-how, field experience, and the ability to hit performance specs reliably, year after year. And value creation often looks boring from the outside—just patient compounding, built on relationships and execution.

Axalta’s journey also contains a few surprises that are easy to miss if you only look at “chemicals” as a commodity category. Pricing power can be very real when switching costs are high and performance is non-negotiable. The refinish aftermarket can be far more resilient than OEM production when the world gets choppy. And a carve-out can unlock focus and accountability that a century inside a conglomerate can unintentionally blur.

For founders building technical businesses, the lesson is straightforward: durable advantage often comes from expertise plus integration. Train customers on your system. Fit into their workflow. Solve problems in the field. Over time, those choices turn products into relationships—and relationships into switching costs that compound.

For investors, Axalta is a reminder that “hidden champions” don’t always come with explosive growth curves. Some of the best businesses are the ones that look ordinary until you understand what customers are actually buying: not a bucket of paint, but a validated process they can trust.

The future will bring plenty to debate—electrification, sustainability requirements, competitive intensity, and the real-world difficulty of integrating a merger at global scale. But the core need that underpins the entire industry isn’t going anywhere. Surfaces will still need protection. They’ll still need durability. And they’ll still need to look perfect.

Sometimes the best businesses are the ones you never think about.

XIV. Further Reading & Resources

Top 10 Long-Form Links & References

-

Axalta Investor Relations (ir.axalta.com) — Annual reports, investor presentations, earnings transcripts, and SEC filings—the best place to follow the company in its own words and numbers.

-

"The DuPont Dynasty" by Gerard Colby — Deep background on DuPont’s empire, and the culture and incentives that shaped Performance Coatings long before it became Axalta.

-

Carlyle Group Case Studies — Useful for understanding the private equity carve-out playbook: how value gets created (and what tradeoffs often come with it).

-

Chemical & Engineering News Archives — A long-running industry lens on coatings technology, major corporate moves, and the broader chemicals landscape.

-

Automotive Aftermarket Reports — Research on the collision repair ecosystem and aftermarket economics from sources like The Hedges Company, AAIA, and Morgan Stanley.

-

PPG, Sherwin-Williams, AkzoNobel Annual Reports — The cleanest way to benchmark the competitive set: portfolio choices, end-market exposure, and how each player talks about pricing, service, and innovation.

-

"Hamilton's 7 Powers" by Hamilton Helmer — A practical framework for competitive advantage—especially helpful for putting language around switching costs, scale, and process power in businesses like coatings.

-

"Understanding Michael Porter" by Joan Magretta — A clear guide to applying Five Forces without turning it into a box-checking exercise.

-

Bloomberg/Reuters Coverage of the 2016–2017 AkzoNobel Takeover Battle — The clearest narrative record of the consolidation frenzy, the stakeholder pushback, and why big deals in coatings are never “just synergies.”

-

Coatings World Magazine — A consistently strong trade source for market trends, new chemistries, and where the industry is heading next.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music