Axis Capital Holdings: The Story of a Bermuda-Born Insurance Disruptor

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

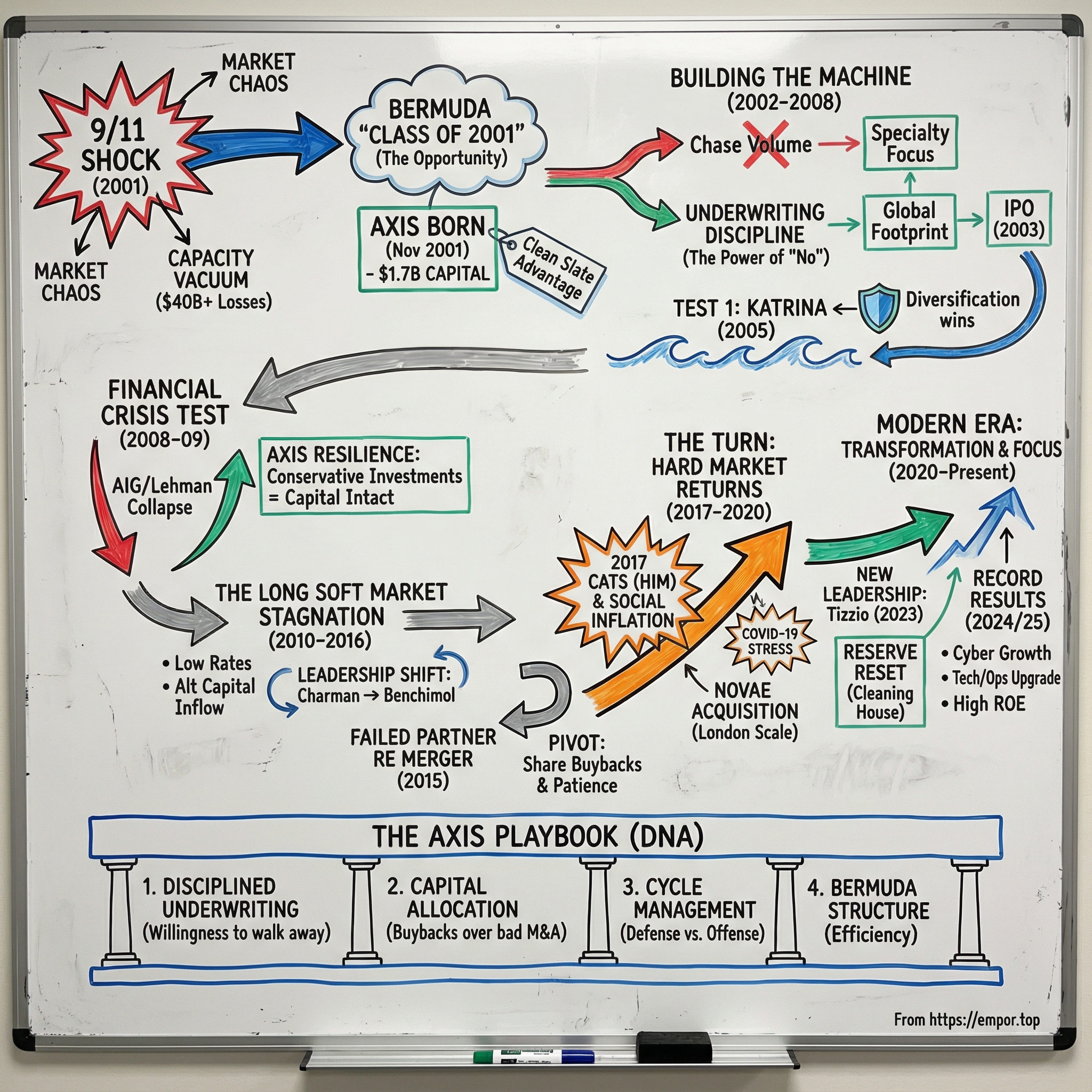

Picture the morning of September 11, 2001. Lower Manhattan’s skyline collapses—and, in a quieter way, so does the insurance industry’s sense of certainty. In a matter of hours, what would become the largest insured loss in history, with estimates topping $40 billion, punches a hole through balance sheets across the world. While first responders ran toward the towers, a different kind of emergency meeting was already starting elsewhere: executives, underwriters, and investors doing the grim math and realizing that an awful vacuum had just opened up. Capacity would disappear. Prices would jump. And in insurance, those conditions don’t just create problems—they create openings.

Axis Capital was born in that opening. Founded in November 2001, with insurance capacity suddenly scarce, the company began operations as AXIS Specialty Limited with $1.7 billion in capital. It formally incorporated on December 9, 2002, putting it among the earliest and fastest-moving entrants in what became known as the “Class of 2001”—the group of Bermuda-based startups that rushed in after 9/11 and went on to reshape global insurance and reinsurance.

Fast forward to today, and Axis is what happens when extraordinary timing meets years of discipline. The company has delivered standout results in recent years, including third-quarter 2025 net income available to common shareholders of $294 million, or $3.74 per diluted common share—an annualized return on average common equity of 20.6%. For 2024, it reported an operating return on equity of 18.6% and record operating earnings per share of $11.18, nearly doubling the prior year.

This is the story of how a crisis-born startup grew into a specialty insurance powerhouse—through brutal market cycles, a global financial crisis, catastrophe years that rewrote the loss models, and the constant pressure of an industry where competitors can undercut you in a single renewal season. Along the way, Axis becomes a lens for the business of insurance itself: how insurers really make money, why timing matters here more than almost anywhere, and why survival often comes down to the courage to say “no” when everyone else is chasing premium.

And, just as importantly, it’s a story about the craft behind the numbers: capital allocation, leadership transitions, and the delicate balance between growth and underwriting discipline that every specialty insurer eventually gets tested on.

II. The Insurance Industry Context & Market Structures

To really understand Axis, you first have to understand the strange little machine that is insurance. It looks simple from the outside—sell policies, pay claims—but the economics run backward compared to most businesses.

Insurance is, at its core, a promise made today about an uncertain tomorrow. An insurer collects premiums upfront, then holds that money until claims come due. That in-between pool is the “float.” If you underwrite well, float can behave like remarkably cheap capital: money you get to invest while you wait. Warren Buffett has long called this one of insurance’s superpowers—when, and only when, the underwriting itself isn’t bleeding.

Axis plays in two related arenas: primary insurance and reinsurance. Primary insurance is what most people think of—coverage sold directly to businesses, from property to professional liability to marine cargo. Reinsurance is one step up the chain: insurance for insurers. When a carrier writes a big policy, or finds itself too exposed to one type of risk, it buys reinsurance to offload part of that exposure to someone else. The result is a layered system—risk passing from policyholders to insurers to reinsurers—that quietly ties together everything from small companies to global conglomerates, and in the modern era, even capital markets investors.

Underwriting performance is often summarized by one brutally honest statistic: the combined ratio. It’s the loss ratio (claims as a percentage of premiums) plus the expense ratio (the cost of running the business). Below 100% means you made money on underwriting—you collected more than you spent on claims and operating costs. Above 100% means you lost money on the insurance product itself, and you’re relying on investment returns from the float to bail you out. That can work for a while. It can also end badly.

The other defining feature of this industry is that it swings. Insurance pricing moves in cycles. In a “hard market,” capital is scarce—usually because losses have punched holes in balance sheets—so capacity shrinks, rates rise, and underwriters get picky. In a “soft market,” capital sloshes around looking for a home. Competition ramps up, prices fall, and risks that should be refused suddenly find willing takers. These cycles are often triggered by catastrophic events or changes in the investment environment, and they can drag on for years.

This is where Bermuda enters the story. Bermuda started emerging as an insurance hub in the early 1990s, but after 2001 it became the industry’s launchpad. It offered a rare mix that mattered intensely to founders and investors: English common law that felt familiar to Lloyd’s of London veterans, a regulatory regime built for sophisticated (re)insurance, no corporate income tax, and a dense ecosystem of underwriters, actuaries, brokers, and service firms. For a new company like Axis, being domiciled in Bermuda wasn’t trivia—it was a strategic choice that enabled efficient capital deployment, operational flexibility, and global competitiveness.

Then, in the background, the competitive landscape got even more complicated. Alternative capital—pension funds, hedge funds, and large institutions hunting returns that don’t move with stocks and bonds—began flowing into risk through catastrophe bonds and insurance-linked securities. That money often competes directly with traditional reinsurance, changing pricing dynamics and compressing margins in ways that legacy players didn’t grow up with.

Put all of this together, and you can see why insurance company valuations can whip around, why “steady” carriers sometimes post shocking losses, and why management quality matters so much. In this business, the edge isn’t just being smart. It’s being disciplined—especially being willing to say “no” when the market is begging you to say “yes.”

III. The Perfect Storm: 9/11 and the Birth of Axis (2001-2002)

September 11, 2001 was a human tragedy first. But for insurance, it was also an extinction-level stress test.

Within hours, carriers and reinsurers were staring at losses coming from every direction at once: property damage, business interruption, workers’ compensation, aviation liability, and terrorism coverage. The industry’s exposure wasn’t just large—it was uncomfortably concentrated in places no model had treated as a single point of failure. Balance sheets that had looked rock-solid the day before suddenly raised solvency questions.

And then something very “insurance” happened: the market didn’t just absorb the shock. It repriced the entire world.

In the roughly three months after the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, more than $11 billion of new insurance capital poured into Bermuda. A dozen or so new companies sprang up to refill the sudden hole in capacity. This burst of formation became legendary as the “Class of 2001.”

Looking back, it’s easy to tell the story like it was inevitable. It wasn’t. Even among the stand-alone survivors—Axis Capital, Arch Capital, Allied World, Endurance Specialty, and Montpelier Re—there was nothing guaranteed about those early days. These companies were being built in real time, in a market moving at high speed, with underwriting decisions that would determine whether they became institutions or footnotes.

As Caroline Foulger, insurance leader and partner at PricewaterhouseCoopers in Bermuda, put it: “This was the largest of the Bermuda waves in terms of both capital dollars and number of new starts and catapulted Bermuda into the group of top three reinsurance jurisdictions and the cat risk capital of the world.”

Axis’s founding team brought credibility the market could recognize immediately. John Charman was a founding partner and served as Chief Executive Officer and President of Axis Capital Holdings Limited from its inception in 2001 until he retired in mid-2012. In industry circles, he was an imposing figure—nicknamed the “King of the London Insurance Market,” and described by the Financial Times as “famously strong-willed and opinionated.”

Charman came to Axis after about three decades at Lloyd’s of London, where he earned a reputation for stepping into hard-to-place risks—including providing war risk coverage during the first Gulf War. That experience—making decisions fast, in a crisis, when everyone else was backing away—translated almost perfectly to the post-9/11 insurance landscape.

Alongside him was Michael Butt, who would become Chairman of the Board. Butt was already a recognized industry leader and played an important role in building Bermuda into a global re/insurance hub. He was also inducted into the Insurance Hall of Fame. His background was unusually broad for an insurance founder: an MA in History from Magdalen College, Oxford, and an MBA from INSEAD in Fontainebleau.

Axis was capitalized with approximately $1.7 billion in November 2001, specifically to meet the market’s sudden need for quality capacity in specialty insurance and global reinsurance after September 11. The investors backing the company understood what they were buying: a timing bet. But it wasn’t a “quick flip” bet—it demanded real capital, and the patience to let underwriting discipline compound.

That original concept also expanded quickly. In the days after 9/11, Bob Newhouse met with Marsh and John Charman with what he later described as a simple idea: it was a unique opportunity to write both insurance and reinsurance. “So we broadened the concept of AXIS to be a specialty insurance and reinsurance company.” Plenty of smart people were moving in the same direction at the same time—but Axis got to market first.

Less than two years later, Axis took a major step toward financial flexibility. In July 2003, it became a publicly listed company on the New York Stock Exchange, going public on July 1 at an offer price of $22.00 per share.

Underneath all of this was a founding thesis that was almost unfair in its simplicity: start clean. A new company didn’t carry the baggage that haunted older carriers—legacy claims, or long-tail exposures like asbestos and environmental liabilities. It could attack a hardening market with fresh capital while incumbents were still triaging their post-9/11 wounds. As one framing put it: “Unlike the global multiline reinsurers, which saw significant reserve deterioration earlier in the last decade, the Class of 2001 reinsurers began operations with a clean slate.”

That clean-slate advantage showed up in results. Over the following decade, the Class of 2001 companies outperformed the global multiline reinsurers, with nine-year and five-year average ROEs of 14.2 percent and 17.7 percent, versus 8.9 percent and 10.7 percent for the multiline group.

The point isn’t that they were magically better. It’s that they were born at the exact moment the market started paying a premium for discipline—and they didn’t have yesterday’s mistakes weighing down tomorrow’s underwriting.

IV. Building the Machine: Strategy & Differentiation (2002-2008)

With $1.7 billion in fresh capital and a hard market opening up in front of them, Axis’s founders faced a choice that defines insurance companies early: chase volume to grab market share, or protect the book and grow only when the price is right. They chose discipline.

John Charman set the tone. At Axis, risk selection came first, even when brokers were pushing hard for more capacity and competitors were happy to undercut. That posture showed up in the company’s early returns: by the first quarter of 2008, Axis reported a 20 percent return on equity, and Charman said it had averaged 18 percent over the company’s nearly seven-year history.

The strategy wasn’t “be everywhere.” It was to be very good in the places where expertise actually matters. Axis centered the business on specialty lines—risks that are complicated, volatile, and hard to price, where underwriting judgment can create a real edge. Instead of fighting commodity battles where price is basically the only differentiator, Axis leaned into professional liability, catastrophe reinsurance, marine, aviation, and credit insurance—businesses built on technical skill and broker relationships.

By 2004, Axis had planted meaningful flags in Bermuda, Europe, and the United States, establishing itself as both a specialty insurer and a global reinsurer. That footprint wasn’t about geography for geography’s sake. It was about distribution. In specialty insurance, the global broker community controls the flow of business, and Axis wanted to be in the rooms where those placements happen.

The expansion continued. Axis pushed into Canada and Europe, and opened a branch in Singapore for what Charman called “highly specialized” business—another signal that the company wasn’t trying to be a mass-market carrier. It was building a global platform for niche risk.

They also started investing early in something insurance companies often talk about, but rarely do well: operational leverage through technology. “You do need efficient technology to be able to process that business,” Charman said. Axis spent the time and money to automate as much as possible, deliberately avoiding the model of piling on headcount to administer small premiums. “We do not want to overwhelm ourselves by having thousands and thousands of people administering small premiums.”

Then came the first real test of that discipline. By the middle of the decade, the market began to soften—capital returned, competition intensified, and prices started sliding. This is the moment when insurers quietly decide who they are. As rates declined and rivals reached for growth, Axis walked away from business it believed wasn’t priced to pay for the risk. As one industry snapshot put it, even as many public companies increased net written premiums in 2008, Bermuda carriers were “living up to their promise to walk away from business that they consider inadequately priced.”

And just as pricing pressure was building, nature delivered a reminder of what this industry is really insuring. Hurricane Katrina hit in August 2005, killing 1,392 people and causing damage estimated at $125 billion. The insured losses were staggering—about $47 billion—and it stressed reserves, catastrophe models, and risk appetites across the market. Axis came through relatively intact, helped by conservative positioning and diversification that some peers didn’t have.

By 2008, the next storm was forming—this time in the financial system. Charman saw the setup clearly, and described it in Reuters with the bluntness you’d want from an insurance CEO: “You could make the case that this is the perfect storm—where you have minimal prices in the insurance industry, and at the same time extraordinary volatility in your investment portfolio.”

Axis didn’t reach for yield to make the numbers look better. “Apart from small allocations to some hedge funds moving into distressed parts of the market, Axis is steering clear,” Charman said. “I am still not sure that the volatility justifies the risk/reward. We may miss a bit of yield, and we can be criticized for that if things go well, but the risk is too great at the moment.”

In an industry where investment income can mask underwriting sins—until it can’t—that kind of restraint would matter a lot in what came next.

V. The Financial Crisis Test (2008-2009)

When Lehman Brothers collapsed on September 15, 2008, the insurance business got hit from two directions at once. The obvious one was the investment side: portfolios that were supposed to be “safe” suddenly weren’t. The less obvious one was underwriting: any book with credit exposure, financial guaranty, or trade credit could blow up precisely when capital was hardest to replace. And AIG’s near-failure—avoided only through a massive government rescue—made the point brutally clear: insurers weren’t spectators to systemic risk. They were participants.

This is where Axis’s earlier restraint stopped looking conservative and started looking prescient. While many carriers took deep mark-to-market hits on mortgage-backed securities and other credit-heavy positions, Axis’s portfolio—managed the way Charman had described months earlier—came through with less severe damage. They hadn’t chased yield. They’d kept the investment playbook boring, and in 2008, boring was a competitive advantage.

AIG’s collapse also reshaped the market in real time. It removed a giant competitor and exposed the danger of mixing insurance operations with financial engineering. But it also spooked customers, regulators, and counterparties, raising questions about the stability of the entire sector. In a business built on trust and long-dated promises, that uncertainty tightened capacity—and for companies that could credibly say, “we’re fine,” it created real pricing opportunity.

For Bermuda’s post-9/11 startups, the crisis became a referendum on what they actually were. The firms that had drifted into complex credit products or levered investment strategies found out how quickly “smart” can turn into fragile. The ones that stuck to the basics—underwrite carefully, invest conservatively—had a much easier time staying on their feet. As one observer put it, “Everything is relative, and seeing one's net worth fall by 'only' 11 percent in 2008 would have warmed many hearts. That the Bermuda companies are increasingly good stewards of the capital with which they are entrusted is plain.”

The deeper lesson was about correlation—one of those concepts that looks tidy in a spreadsheet until the world catches fire. Insurers tend to assume their underwriting risks and investment risks live in separate rooms. A hurricane in Florida shouldn’t have anything to do with bond prices. In 2008, those walls came down. Under stress, correlations rose, liquidity vanished, and risks that looked independent suddenly moved together because the entire financial system was the connecting tissue.

Axis came out of the crisis with its capital base largely intact and its reputation strengthened. The same discipline that shaped its underwriting had carried over into investment management, and that combination became a blueprint for how the company would try to navigate future shocks.

But the crisis also planted the seed for the next era. As central banks intervened and rates fell, capital flooded the system looking for returns. And sooner or later, some of that money was going to find its way into insurance—setting up the long, grinding soft market that followed.

VI. The Long Soft Market & Strategic Pivots (2010-2016)

The crisis passed, but it left the industry with a different kind of problem: too much capital chasing too little return. Central banks pushed rates down and kept them there. For insurers, that meant the “easy” part of the model—earning solid investment income on the float—stopped being easy. Even a well-underwritten book could struggle to produce attractive overall returns when yields were pinned to the floor.

At the same time, a new competitor showed up with a very different set of incentives. Alternative capital—pension funds and hedge funds looking for returns that didn’t move with stock markets—poured into reinsurance through catastrophe bonds and insurance-linked securities. This money often behaved differently than traditional reinsurance capital: it could be less emotional, more systematic, and willing to sit in the market even when pricing got thin. The result was years of persistent pressure on margins, with no obvious “reset” in sight.

Inside Axis, this stretch also brought a major leadership transition. AXIS Capital announced that John R. Charman would retire as Chief Executive Officer and President effective May 3, 2012, the date of the Company’s 2012 Annual General Meeting of Shareholders. He would be succeeded by Albert Benchimol.

Benchimol had joined Axis in January 2011 as Executive Vice President and Chief Financial Officer. Before that, he spent a decade at PartnerRe, serving as Executive Vice President and Chief Financial Officer from April 2000 through September 2010, and also leading PartnerRe’s Capital Markets Group business unit as Chief Executive Officer from June 2007 through September 2010. Earlier in his career, he was Senior Vice President and Treasurer at Reliance Group Holdings, Inc. for 11 years. In other words: a finance-and-capital-markets operator stepping into the top job right as the industry’s economics were being reshaped by capital markets.

The transition, though, didn’t happen quietly. Charman stepped down as CEO in May 2012, and Axis initially appointed him executive chairman. Within weeks, the board removed him as chairman after differences “over his understanding of the role and responsibilities of the chairman position.” Axis’s termination of Charman’s contract ultimately cost the company around $36 million—an unusually public, unusually expensive reminder that governance matters just as much as underwriting when the stakes are high.

With Benchimol in charge, Axis leaned into selective platform-building rather than sprawling expansion. The company received approval from Lloyd’s for the establishment of AXIS Syndicate 1686 for the 2014 underwriting year—an important move, because Lloyd’s is still one of the world’s most influential marketplaces for specialty risk.

But the defining corporate saga of the period wasn’t Lloyd’s. It was PartnerRe.

On January 25, 2015, AXIS Capital and PartnerRe announced a definitive amalgamation agreement that would have created a combined specialty insurance and reinsurance heavyweight—more scale, more capital, and a bigger footprint in a world where size can help, especially when markets get tough.

The deal didn’t get to glide through. By June 2015, AXIS and PartnerRe were publicly campaigning to win shareholder support for the merger, even as a competing bid emerged from Exor SpA.

Ultimately, the merger collapsed. PartnerRe paid Axis a $315 million fee to immediately terminate the amalgamation agreement, and Axis cancelled its shareholder meeting that had been scheduled for August 7, 2015.

Axis didn’t treat the failure as a cue to lunge for the next “big thing.” Instead, it snapped back to a familiar playbook: capital discipline first. Alongside the termination announcement, the company reinstated its share repurchase program, which had $749 million remaining under the Board’s authorization. Benchimol framed the moment plainly: “We are prepared to move ahead with our fiscally disciplined growth strategy and a commitment to return excess capital to shareholders in the form of dividends and stock repurchases. Since becoming a public company, we have repurchased approximately 92.8 million shares of AXIS Capital stock for a total of $3.3 billion.”

The subtext was even clearer than the quote: in a soft market, you don’t have to prove your ambition by buying something expensive. Sometimes the most aggressive move is to stay patient, protect the book, and give capital back until the market finally gives you a reason to lean in again.

VII. The Accident Year & Hard Market Return (2017-2020)

By 2017, the industry had started to believe its own myth: that catastrophe risk could be modeled, diversified, and smoothed into something manageable. Then the Atlantic hurricane season reminded everyone what “tail risk” actually looks like.

Harvey, Irma, and Maria hit in rapid succession, driving insured losses above $100 billion and ripping through an industry that had spent years competing on price. Axis felt it, too. Management summed up the year plainly: “We closed 2017 with a diluted book value per share of $53.88, a decrease of 7.5% from December 31, 2016, which is not unreasonable when compared to the scale of market losses observed during the period.”

But in insurance, pain is often the precursor to profit—if you’re still standing when the repricing starts. The 2017 losses finally cracked the long soft market and set off a broad reset in rates that accelerated over the next few years. At the same time, other pressures were building that couldn’t be solved by catastrophe models alone. Social inflation—rising jury awards and litigation costs—pushed casualty pricing higher. And California’s wildfires forced the industry to confront a risk it had historically underpriced, especially where urban development pressed up against fire-prone terrain.

Axis wasn’t just waiting for the cycle to turn. It was building into it. As the company put it: “Notwithstanding the industry backdrop, it was a very successful quarter and year from an organizational development perspective, as we closed on the acquisition of Novae and made further progress on strategic initiatives, all of which have contributed to the delivery of a much stronger platform with differentiated positioning and leadership positions in key markets.”

Novae mattered because it wasn’t “growth for growth’s sake.” It was a scale-and-distribution play in the heart of specialty insurance. The deal created a $2 billion insurer in London and a top ten (re)insurer at Lloyds, bringing total global gross written premiums to $6 billion based on 2016 actual results. In other words: Axis was buying a bigger seat at one of the world’s most important specialty tables, in lines where relationships and reputation determine who gets shown the best risks.

The acquisition price—$611.5 million in cash—also showed up quickly in the financials. Axis said its first-quarter 2018 net income and premium volume jumped meaningfully year over year, driven largely by the Novae deal. Net premiums written rose 25 percent in Q1 versus the prior year.

Then, just as the market was hardening, the world threw a different kind of catastrophe at the industry. COVID-19 didn’t flatten buildings; it attacked contracts. Business interruption claims, event cancellation losses, and the legal uncertainty around pandemic exclusions created a fog-of-war moment for insurers everywhere. Axis moved carefully through it, leaning on its specialty focus and careful policy wording as the broader industry wrestled with fundamental questions about what coverage obligations really meant in a global shutdown.

Amid that upheaval, one of the company’s founders stepped away. Michael Butt, co-founder and Chairman of the Board of Directors, retired effective September 16, 2020. Butt had been Chairman since September 2002 and helped steer Axis from a post-9/11 startup into a global (re)insurance player. In 2011, he was named an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) for his contributions to building Bermuda’s reinsurance industry.

By the end of 2020, the story of the cycle had flipped. The catastrophes of 2017—and the uncertainty and loss experience that followed—had restored pricing power. In specialty lines, rate increases of 10–20% or more became common, creating the kind of environment Axis had been waiting for: one where disciplined underwriters could finally grow, and get paid appropriately for the risks they were taking.

VIII. Modern Era: Digital Transformation & Strategic Focus (2020-Present)

The years since 2020 have been Axis’s shift from a crisis-born survivor into something more durable: a modern, institutionally run specialty platform. Not a reinvention for the sake of reinvention—but a tightening of the machine. New leadership. Sharper strategy. Better operating cadence.

That leadership change became official in 2023. AXIS announced that Albert A. Benchimol would step down on May 4, 2023, timed to the company’s Annual General Meeting, and would retire at the end of 2023. His successor was Vincent C. Tizzio, who at the time served as CEO, Specialty Insurance and Reinsurance, overseeing all business lines and front-end operations for AXIS.

Tizzio arrived with a resume built for this exact moment. Before joining AXIS in 2022, he was EVP and Head of Global Specialty at The Hartford, running a multi-billion dollar business selling specialty products through wholesale and retail channels. Before that, he spent seven years as President and CEO of Navigators Management Company, leading it until The Hartford acquired it in 2019. And earlier still, he held senior leadership roles at Zurich Financial Services and AIG.

But the bigger story wasn’t his background. It was his posture on day one.

Tizzio treated the transition as an inflection point—and started by confronting what hadn’t worked. He framed it as a set of uncomfortable questions the company needed to answer: “How did we create the inability to manage volatility risks in our portfolio? How did we lose the ability to gain market share in previously announced chosen market spaces? And how did we think about performance management in our company?”

Then he moved quickly on the messiest kind of legacy issue in insurance: reserves.

In the fourth quarter of 2023, Axis strengthened its prior year reserves by $425 million pre-tax ($361 million post-tax), tied to both its insurance and reinsurance segments in liability and professional lines, predominantly related to 2019 and older accident years. Axis said this amounted to 4.5% of net loss reserves at September 30, 2023.

Axis explained that 90%, or $354 million, of the charge was attributed to 2019 and earlier in liability reinsurance, following an internal review of trend assumptions, development patterns, and open claims. The company’s own conclusion was blunt: the review “reflects the reality that our U.S. casualty and professional lines have shown sustained adverse development, driven largely by economic and social inflation.”

What’s striking is how the market took it. Despite the $425 million announcement, Axis shares rose about 7%—a signal that investors saw the move not as a stumble, but as a credible reset under new leadership.

From there, Tizzio pushed a broader repositioning. Axis described his tenure as a strategic overhaul that drove record financial performance and total shareholder returns that grew more than 100% over a two-year period. Under his leadership, AXIS expanded product capabilities, repositioned AXIS Re as a specialist reinsurer, and rolled out its “How We Work” program to upgrade operations across the organization.

And through it all, Axis kept returning to its origin story—because it still explains the company’s DNA. As Tizzio put it: “AXIS is a 24-year-old public company. It was formed in the aftermath of the first attack here in New York City, by an entrepreneur, with the aim of bringing what is called terrorism and catastrophe property insurance to the world.”

In the modern specialty market, one of the clearest growth arenas has been cyber—and Axis invested accordingly. In June 2024, AXIS launched AXIS Cyber Incident Commander, a service for U.S.-based, direct primary cyber insurance customers designed around speed of response. The idea was simple: when a cyber event hits, the policyholder gets a single point of contact and immediate guidance from experienced cyber experts.

The financial results began reflecting the tighter operating model. Full-year 2024 net income reached $1.05 billion, alongside a 98% increase in operating EPS. Axis also launched new initiatives tied to energy transition and expanded cyber capabilities—signals that the company wasn’t just riding a hard market, but trying to build products and services that could outlast it.

IX. Acquisitions & Capital Allocation Philosophy

Axis’s capital allocation tells you almost everything about how it thinks—and why it has avoided the “roll-up” trap that’s tempted so many insurance companies when growth gets hard.

The company has been selective with M&A, treating acquisitions as a tool, not a personality. Novae in 2017 was the biggest deal in Axis’s history, but it wasn’t about getting bigger for the sake of it. It was about getting better positioned in the world’s most important specialty marketplace. As Axis put it at the time: “This is a significant acquisition and an important milestone for AXIS. Acquiring Novae greatly adds to the scale and breadth of our international business and also underscores our commitment to London and to Lloyd's, which continues to be the pre-eminent market for specialty risks.”

If Novae shows what Axis will buy, the failed PartnerRe merger shows what it won’t: a “transformational” transaction at any price. Axis ultimately walked away, collected a $315 million breakup fee, and pivoted back to what it could control—reinvesting in the business and returning capital to shareholders.

Buybacks, in particular, have been a recurring theme since the IPO. Over time, Axis has repurchased billions of dollars of stock, a signal that management has been willing to treat its own shares as an investment when they believed the market price didn’t reflect intrinsic value. And it’s not just history: from a position of improved financial strength, the company leaned on repurchases again, using its program in the order of magnitude of $200 million over the course of 2024.

That discipline shows up in how leadership talks about deals today. Tizzio has left the door open to acquisitions if they genuinely add capabilities—but he’s been clear that the center of gravity is internal. “I think there's plenty of reason to use our capital inside the house of Axis to continue to bring teams of people.”

All of this is reinforced by the company’s Bermuda structure, which gives it real capital-efficiency advantages: a regulatory environment designed for sophisticated (re)insurance and no corporate income tax, which leaves more cash flow available for investment and shareholder returns. That advantage compounds over time—even as it periodically draws political scrutiny in the United States.

And then there’s the quieter part of the story: dividends. Axis has maintained a consistent dividend policy, using it as a steady baseline return while preserving flexibility for buybacks and reinvestment. The balance between dividends, repurchases, and retained earnings has been less about rigid formulas and more about stewardship—an attempt to do what insurance cycles demand most: stay liquid, stay disciplined, and be ready when the market finally offers truly attractive risk-adjusted returns.

X. The Axis Playbook: What Makes Them Different

After more than two decades, Axis has settled into a style that’s easy to describe and hard to execute: it tries to behave like a specialist underwriting shop that happens to be well-capitalized, globally connected, and structurally set up to play the cycle. That combination is what separates it from the giant generalists on one side and the niche boutiques on the other.

Everything starts with underwriting discipline. In a business where the easiest way to grow is to say “yes” and let tomorrow worry about today’s price, Axis has tried to make “no” a core competency. As Tizzio put it, “The first was to restore the underwriting culture that formed the very beginning of what AXIS was—we were an underwriting company, led by a strong underwriting orthodoxy.” That’s not just rhetoric. It’s a willingness to walk away when brokers are pushing for capacity and competitors are handing out terms. The trade is straightforward: less premium in the short run, fewer unpleasant surprises later.

Then there’s specialization over scale. Axis isn’t trying to be a little bit of everything. It’s trying to be best-in-class in specific places where expertise actually changes outcomes. Tizzio has been explicit that the goal is to be a specialist (re)insurer, not a bloated conglomerate. The business is split roughly a quarter reinsurance and three quarters insurance, with a concentration in North America and the London Market—less “sprawl,” more deliberate capital placement.

Technology and data are the modern amplifier. Specialty insurance still runs on judgment, but judgment gets sharper with better inputs. Axis has been putting real money into the plumbing of the business. “We’re investing heavily in our how we work programs which require technology dollars, data and analytic dollars, people, investments,” Tizzio said. The point isn’t flashy InsurTech theater. It’s the unglamorous ability to price risk more accurately, operate more consistently, and learn faster than the market.

Cycle management is the other pillar. This industry punishes companies that can’t change their behavior when the environment changes. In soft markets, the job is defense: protect the book, don’t chase premium, don’t pretend investment returns will make up the difference. In hard markets, the job flips to offense: deploy capital into opportunities that finally pay for the risk. Getting that timing right—year after year, renewal after renewal—is one of the clearest separators between long-term compounders and the companies that look great right before they blow up.

The Bermuda advantage still matters, even if it’s no longer exclusive. In 2001, being Bermuda-domiciled was a differentiator. Today, it’s table stakes for many global (re)insurers. But the core benefits remain: capital efficiency, regulatory flexibility, and a deep ecosystem of insurance talent that makes the whole machine run smoother than it would in a less purpose-built jurisdiction.

Distribution is another quiet edge—and a quiet vulnerability. Specialty insurance is still relationship-driven, and Axis lives inside the broker ecosystem. That gives it access to sophisticated placements and a steady pipeline of risks. But it also concentrates leverage with a few gatekeepers: Marsh, Aon, and Willis. When a small number of intermediaries control the flow, they can push on pricing and terms. Axis’s job is to keep those relationships strong without letting the market talk it into bad business.

Finally, there’s investment conservatism—the boring discipline that keeps you alive. Insurance history is a graveyard of companies that underpriced risk and tried to make it up by reaching for yield. Axis has generally resisted that temptation, and it’s not separate from the underwriting culture—it’s part of the same worldview. If you want to be around for the next cycle, you don’t build a business model that depends on everything going right in the capital markets.

XI. Porter's Five Forces Analysis

If you run Axis through Michael Porter’s Five Forces, you get a clear picture of what it’s up against—and why “good management” matters so much more here than some built-in structural advantage.

Threat of New Entrants: Medium-High

Starting a specialty insurer takes real capital, but it’s not out of reach—especially when the market hardens and investors suddenly remember that insurance can be a great business at the right price. Over the last few decades, there have been several moments when a soft market snapped into a hard one—1985, 1992, 2001, 2005, and 2020—and each time, new companies rushed in to sell scarce capacity.

There are real barriers, though. Licenses don’t magically appear. Getting approved by Lloyd’s, Bermuda’s regulator, and U.S. state insurance departments takes time, expertise, and credibility. And in specialty insurance and reinsurance, credibility is the product: cedents want counterparties they believe will still be standing when claims come due. That creates a time-based moat—one new entrants can’t buy instantly, no matter how much capital they raise.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Low-Medium

In this business, “suppliers” are mainly two groups: the reinsurers that primary insurers rely on for protection, and the capital providers who fund the whole machine. In recent years, the flood of alternative capital has dulled traditional reinsurers’ pricing power, because buyers have more places to go.

Axis has also built a partial release valve here. Its ILS business helps it access capital markets and manage retrocession costs more directly, reducing dependence on any single source of reinsurance capacity.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: Medium-High

Large commercial customers push hard on price and terms, and they usually do it through brokers—who control distribution and run competitive processes. That model is invaluable for getting business in the door, but it also means negotiations often start with someone whose job is to squeeze the market on the buyer’s behalf.

But buyer power isn’t constant. It drops fast when the risk is unusual, complex, or simply hard to place. In those moments—when coverage is scarce and expertise matters—underwriters regain leverage. Axis’s posture fits that reality: “Our appetite has been described as selective, opportunistic, and that we're not trying to be all things through all people.”

Threat of Substitutes: Medium

Big companies can and do keep risk for themselves through self-insurance and captives. Capital markets can also step in, especially in catastrophe, through cat bonds and broader ILS structures that compete directly with traditional reinsurance.

And sometimes the substitute is the government. Terrorism and flood already have backstops, and after COVID, the idea of public-private solutions for pandemic risk isn’t going away.

Still, substitutes hit a wall when risks get messy. The lines Axis leans into—professional liability, cyber, specialty property—often require real underwriting judgment, claims expertise, and bespoke terms. You can’t “index fund” your way through every loss scenario.

Industry Rivalry: High

Rivalry is the constant drumbeat. Specialty insurance is crowded: Lloyd’s syndicates, global carriers, and sharp regional players all competing for the same renewals. In soft markets, that rivalry turns brutal, because the fastest way to grow is to cut price—and someone always will.

True specialty lines are less commoditized than standard business, but they’re not immune. The pressure is always there, and it never really ends.

Taken together, the Five Forces point to a sector with only moderate structural profitability. The winners aren’t protected by an unbreakable moat. They win by operating better—selecting risk more intelligently, managing cycles more ruthlessly, and staying disciplined when the market tries to seduce them into writing bad business.

XII. Hamilton's 7 Powers Framework Analysis

Hamilton Helmer’s framework asks a simple question: what, if anything, gives a company an advantage that actually lasts? For Axis, the answer depends on which “power” you’re looking at. Some are structural. Some are historical. And one, in particular, is the reason Axis has been able to keep showing up at the right moments without blowing itself up.

Scale Economies: Moderate

Scale helps, but it doesn’t settle the game. If you can spread underwriting expertise, systems, and data investments across a larger premium base, your unit economics improve. But insurance isn’t software—nobody wins just by being biggest. In fact, too much scale can become its own risk: more complexity, slower decisions, and a higher chance you’ve accidentally concentrated exposure. Write too much in one geography or one line, and a single event can do real damage.

Network Effects: Weak

There aren’t classic network effects in insurance. One customer buying a policy doesn’t inherently make the product better for the next customer.

That said, there are faint, insurance-shaped versions of them. Broker relationships can create a flywheel: if Axis becomes a preferred market for major brokers, it tends to see a better flow of submissions. And there’s a growing data effect too. More policies mean more loss experience, which can improve pricing models over time. It’s not a social network, but the feedback loop is real.

Counter-Positioning: Moderate-Strong (Historical)

Axis’s original counter-positioning was very real. In 2001, the Bermuda model let it start fresh—unburdened by old reserves and legacy structures—right as legacy carriers were dealing with the aftermath of 9/11 and the baggage of prior cycles.

But that advantage faded as others copied the playbook. Today, the counter-positioning is more subtle: Axis’s specialty-first mindset still stands apart from diversified giants trying to be all things to all buyers. It’s not as novel as it once was, but it still shapes how Axis competes.

Switching Costs: Moderate

On paper, switching should be easy. Most policies renew annually, and that creates a built-in moment for buyers and brokers to shop around.

In practice, specialty insurance is relationship-driven, and relationships create friction. Cedents and insureds value consistency, and they don’t love the cost of bringing a new underwriter up the learning curve on a complex risk. In pockets like program business and multi-year deals, switching costs can be higher still.

Branding: Moderate

This isn’t consumer branding. In commercial insurance, the “brand” that really matters is trust—and the shorthand for trust is ratings.

Financial strength ratings from A.M. Best and S&P act as the industry’s permission slip. Without them, you can’t access certain brokers, buyers, and programs. Axis highlights that its operating subsidiaries have been assigned a financial strength rating of “A+” (“Strong”) by Standard & Poor’s and “A” (“Excellent”) by A.M. Best.

Cornered Resource: Weak-Moderate

Underwriting talent is scarce, and it matters. Axis has historically been able to attract strong teams, which is a real advantage—but it’s not exclusive, and it can walk out the door.

Proprietary data and models are an emerging resource as well, though not a fully “cornered” one. And the Bermuda domicile—once a genuine differentiator—has largely become table stakes as the market matured and the model spread.

Process Power: Strong and Growing

This is the one that looks like a moat.

Axis’s advantage lives in process: underwriting discipline, risk selection, and a culture that’s comfortable saying “no” when others say “yes.” Add in improving analytics and operating rigor, and you get something that compounds—not because it’s impossible to copy, but because it’s hard to replicate consistently, year after year, through cycles.

Tizzio has been explicit about making this central again: “The first was to restore the underwriting culture that formed the very beginning of what AXIS was—we were an underwriting company, led by a strong underwriting orthodoxy.”

XIII. Bear vs. Bull Case

The Bull Case

The bullish case for Axis is basically a story about timing, cleanup, and execution.

First, the turnaround is showing up where it matters: in shareholder returns and in operating performance. Under Tizzio, total shareholder returns have risen more than 100% over a two-year stretch, and the company posted record operating earnings per share of $11.18 in 2024—up 98% from the prior year. In insurance, you can’t fake that for long. It usually means the portfolio is better positioned, pricing is stronger, and the organization is running with more discipline.

Second, Axis is pointed at the parts of the market that are actually growing. Specialty insurance is where new risks show up first—and where expertise still gets paid. Cyber is the clearest example. Industry forecasts expect cyber insurance to expand dramatically over the next decade, and Axis has been investing in product and services to be a meaningful player as that market matures. Climate-related risks and emerging technology exposures are similar: complicated, fast-changing, and not easily commoditized.

Third, the cycle has finally been cooperative. Even as the hard market has started to moderate in some areas, pricing power has remained real across many specialty lines. Axis’s results have reflected that: “In a high catastrophe quarter for the industry, AXIS produced consistent, profitable results. In the quarter, we generated an annualized operating ROE of 17.3% and a group combined ratio of 93.1%.”

Finally, there’s a structural tailwind that’s easy to overlook: Bermuda’s capital efficiency. Over long periods, that advantage compounds. And the ugly reserve strengthening in late 2023, while painful, also reset expectations and left Axis starting from a cleaner base for forward profitability.

The Bear Case

The bearish case is the reminder that insurance is still insurance—an industry where gravity always returns.

Start with commoditization. Over long time horizons, insurance pricing tends to get competed away. Specialty lines can resist that longer than standard lines, but they’re not immune. If capital stays abundant and competitors get aggressive, the same risks that look attractively priced today can become a margin trap at the next renewal.

Then there’s climate. Catastrophe pricing depends on models, and models depend on history. If climate volatility keeps shifting the underlying loss distribution faster than the industry can reprice, yesterday’s “disciplined” book can become tomorrow’s surprise.

Casualty is the other slow-burn problem. Social inflation and nuclear verdicts have a way of showing up years later, after the premium is already earned and spent. Axis’s 2023 reserve charge was proof that even careful underwriters can get caught when litigation trends move against them.

And alternative capital isn’t going away. Insurance-linked securities and cat bonds have permanently changed the supply side of reinsurance, often pushing down returns and making it harder to earn strong margins through the cycle.

Which leads to the simplest bear point of all: eventually, the market will soften again. When it does, Axis will get tested on the one thing that ultimately decides whether a specialty insurer compounds or disappoints—its willingness to protect the book when “growth” is the easiest story to sell.

Key Metrics to Watch

If you want to track whether the bull case is staying intact—or the bear case is starting to bite—two metrics tell you most of what you need to know:

-

Combined Ratio (target: <95%): This is underwriting truth serum. Sustained drift toward, or above, 100% usually means pricing is slipping, losses are deteriorating, or discipline is weakening.

-

Return on Equity (target: 12-18%): This captures the full machine—underwriting plus investments. Consistent double-digit ROE through different market conditions is one of the clearest signals that management is allocating capital well and managing volatility, not just benefiting from a single good year.

XIV. Recent Developments & Future Outlook

The most recent results have largely reinforced the direction Axis has been trying to take the company: steadier execution, cleaner risk selection, and a platform that can keep compounding even as the market cools.

For full-year 2024, AXIS reported revenue of $5.96 billion, up 5.6% from the prior year. Management framed it as a turning point: “We believe that 2024 was a pivotal year in the Axis journey where the company delivered on its promises, enhanced its value proposition, continued to generate consistent, profitable results and achieved new recognition in the marketplace as a competitive force in the specialty arena.”

By the third quarter of 2025, the momentum was still visible. AXIS reported EPS of $3.25 and revenue of $1.67 billion, which came in above expectations and helped drive a 5.81% increase in the stock price. Gross premiums written rose 9.7% to $2.1 billion, the combined ratio came in at 89.4%, and annualized operating ROE was 17.8%. Book value per diluted common share increased 14.2% year over year to $73.82.

Underneath the quarterly beats, the forward plan is about building leverage into the operating model. The company has said it’s investing in AI and modernizing its underwriting platform, while targeting mid to high single-digit insurance growth in 2026 and potential double-digit growth with RAC Re. As CEO Vincent Tizzio put it, “We are building on our momentum,” adding, “The best is yet ahead for AXIS.”

Looking ahead, a few priorities will shape what Axis becomes from here:

Technology and AI Integration: Specialty insurance is still a human-judgment business—but the winners increasingly pair judgment with better data, better workflow, and better decision support. Axis’s investments here are aimed at doing the unsexy things well: faster underwriting, sharper pricing, and fewer mistakes that only show up years later.

Climate Risk Management: Climate volatility raises the stakes for catastrophe modeling and portfolio construction. The carriers that can price the risk, limit their accumulations, and stay disciplined when the market gets excited will be the ones that can keep writing the business when others have to pull back.

Cyber Insurance Evolution: Cyber is moving from a “Wild West” period toward something more standardized and technically priced. That transition tends to reward specialists—carriers that can pair underwriting with response capabilities and claims expertise—and Axis has been positioning itself to be one of them.

Capital Deployment Discipline: The hard market doesn’t last forever. The real test for Axis will come when competition increases, pricing softens, and “growth” becomes the easiest story to tell. If the company keeps the same posture it’s been advertising—protecting margins, returning capital when it can’t find good risk, and leaning in only when paid—it has a shot at making the recent performance durable, not just cyclical.

XV. Epilogue & Final Reflections

Axis Capital’s story is a reminder that in financial services, the product is trust—and the raw material is discipline. You can get the timing right once. You can even get lucky for a year or two. But to endure, you have to build a machine that keeps making good decisions when the easy ones are right there on the table.

What Makes Insurance Companies Great

Great insurers look almost boring from the outside. They’re patient. They’re consistent. They’re willing to leave business on the table when the price isn’t there.

Most insurers fail some version of that test. They chase premium when the market softens. They get “creative” with reserving to make earnings look smoother. Or they reach for investment yield when rates fall, trying to fix underwriting problems with the capital markets. The ones that survive over decades tend to share a common trait: they refuse to build a business model that depends on everything going right.

Axis has spent much of its life trying to be in that second category.

The Founder's Advantage and When It Fades

John Charman helped set Axis’s early identity: aggressive where it mattered, conservative where it counted, and deeply focused on underwriting judgment. That founder edge can be a real weapon in the first chapter of a company’s life—especially in insurance, where clarity of risk appetite is everything.

But insurance is also a long-duration business. The liabilities outlive the headlines, and the mistakes show up years later. Over time, the question shifts from “Can the founder will this company into existence?” to “Can the organization institutionalize what made it good?”

Axis’s messy 2012 transition—and the leadership evolution from Charman to Benchimol to Tizzio—made that lesson unavoidable. The company’s long-term viability depended on turning founder instinct into repeatable process.

Why Timing Matters

Axis is, in many ways, a timing company.

Starting in 2001—right after 9/11 destroyed capital, shocked the models, and forced the market to reprice—was an unusually fertile moment to launch a well-capitalized specialist. The Class of 2001 also had a structural gift that older carriers didn’t: a clean slate, without decades of legacy liabilities.

Move that founding date to 2011, in the depths of a soft market and near-zero rates, and the same team could have looked mediocre. Move it to 2021, with alternative capital more entrenched and competition more sophisticated, and the playbook would have been harder to run. In insurance, “when” is often as important as “what.”

The Paradox of Insurance

In most businesses, saying “yes” to revenue is the default. In insurance, saying “yes” too often is how you die.

Disciplined underwriting means walking away from risks that aren’t priced for reality—especially when everyone else is telling you the market is “different this time.” Axis’s willingness to pass on inadequately priced business, even when it made growth look slower in the moment, has been central to both its survival and its credibility.

The business you don’t write can matter more than the business you do.

Lessons for Founders

In financial services, culture really does eat strategy—because culture is what determines decisions under pressure.

Underwriting discipline can’t live in a slide deck. It has to show up in who you hire, how you promote, what you reward, and what you tolerate. It means paying for long-term performance, not short-term volume. It means protecting standards in soft markets, when the industry is begging you to loosen them. In the end, that’s the difference between a franchise that compounds and one that simply survives until the next accident year exposes it.

Lessons for Investors

Insurance rewards investors who look past surface-level earnings and focus on the underlying engine.

The combined ratio is the clearest window into underwriting truth. ROE across cycles tells you whether management can run the whole machine, not just benefit from a favorable year. And reserve development is the quiet signal of how conservative—or how aggressive—a company has been about its past decisions.

The biggest edge isn’t predicting next quarter’s catastrophe losses. It’s identifying insurers with the discipline to stay rational when the market gets irrational.

The Bigger Picture

Insurance is societal infrastructure. It’s how unpredictable losses become manageable costs—how businesses keep operating after disasters, how projects get financed, how economies take risks without collapsing under them.

When insurers fail, the damage doesn’t stop at shareholders. It spreads to policyholders, counterparties, and entire markets that suddenly discover “capacity” was never guaranteed. The companies that build durable franchises—by pricing risk honestly and managing capital conservatively—end up doing something broader than earning a profit. They help keep the system stable.

"Fundamentally, we're a specialist underwriter. We cover unique exposures in a customized way that is fit for the risks of individual companies."

Axis went from a crisis-born startup to a global specialty insurer with nearly $6 billion in annual revenue and record profitability. But the real story isn’t just what it built—it’s how. Over and over, through cycles and shocks, it tried to choose discipline over applause.

The next chapter will be the same test in new forms: climate volatility, cyber complexity, and the inevitable return of competitive pressure. The question isn’t whether Axis will face those forces. It’s whether the culture and capabilities it has spent two decades rebuilding can keep making the hard choices when the market makes the easy ones tempting.

XVI. Further Reading & Resources

Books: 1. Against the Gods: The Remarkable Story of Risk – Peter Bernstein 2. The Outsiders – William Thorndike (a great lens on capital allocation) 3. Buffett's Letters to Shareholders (especially the sections on insurance and float)

Long-Form Articles & Papers: 4. Axis Capital Holdings 10-K filings (2002, 2008, 2017, 2023) – SEC.gov 5. “The Class of 2001: Bermuda Reinsurers Twenty Years Later” – Insurance Journal 6. A.M. Best special reports on the Bermuda market 7. McKinsey Insurance Practice: “The Hard Market Returns” reports 8. Geneva Association research on social inflation in casualty insurance

Investor Resources: 9. Axis Capital investor presentations and earnings calls (last 5 years) – AxisCapital.com 10. Keefe, Bruyette & Woods (KBW) insurance sector research

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music