Avista Corporation: Power, Persistence, and the Future of Regional Energy

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

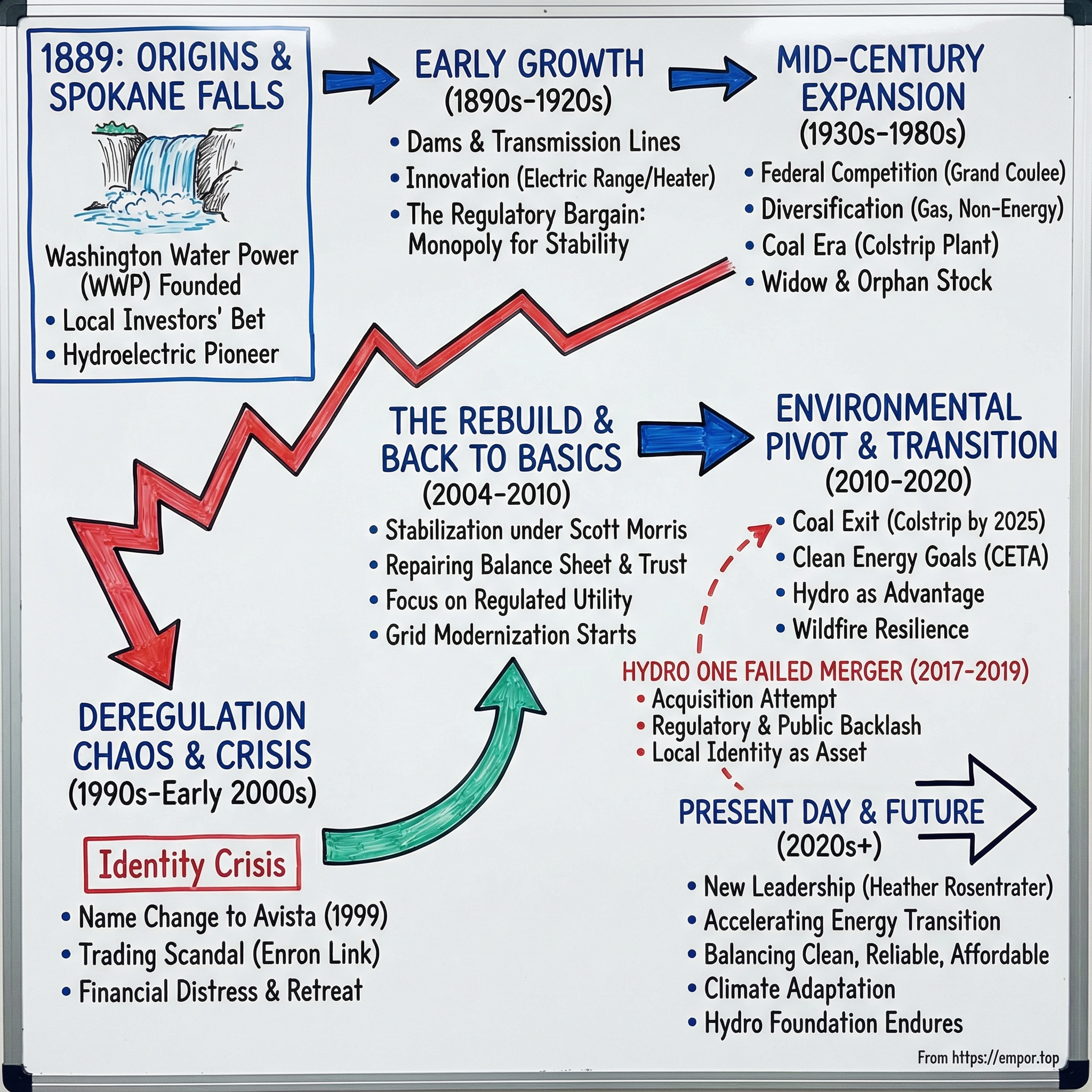

Picture Spokane in 1889. The falls on the Spokane River are thundering through what’s still Washington Territory, just months from becoming a state. And down at the water’s edge, a small group of local businessmen is making a bet that people back East don’t take seriously.

New York financiers had looked at their plan to turn the Lower Falls into electricity and basically shrugged: not worth the trouble. But ten investors who actually lived there could see what outsiders couldn’t. This river didn’t just look powerful. It was power. So they formed Washington Water Power and set out to do something that, at the time, still felt like science fiction: turn falling water into a modern economy.

That one decision—part necessity, part stubborn independence—set in motion the creation of one of the oldest continuously operating utilities in America.

Fast-forward 136 years. The company is now Avista Corporation, and it’s facing a question the original founders couldn’t have even phrased, let alone answered: how does a 19th-century hydro pioneer survive—and thrive—through a 21st-century energy transition? That question is bigger than Avista. It’s really a lens on American infrastructure, the strange and fascinating economics of regulated monopolies, and the collision between climate goals and the unforgiving requirement that the lights stay on.

Avista Utilities is the operating division today. It supplies electricity to nearly 418,000 customers and natural gas to about 382,000 across roughly 30,000 square miles in four Northwestern states. Which sounds simple—until you think about what it really means. This is a business where the product is invisible until it’s gone, the expectations are absolute, and the most valuable assets might be ones you can’t build anymore. Like hydro.

And that brings us to the three threads running through this story.

First is geography—how the Inland Northwest, with its rivers, forests, and climate, didn’t just influence Avista’s path, but practically wrote it.

Second is regulation. Avista gets the extraordinary stability of being a regulated monopoly, but the trade is that nearly every meaningful decision is made in public, in front of regulators, advocates, politicians, and customers who all have different definitions of “fair.”

Third is the central tension of modern energy: the push to get cleaner, faster—without breaking reliability in a region where winters are real and heating isn’t optional.

Avista has said it expects long-term earnings growth in the 4–6 percent range off its forecast 2025 base year. In utility land, that’s the point. It’s steady, not flashy. But delivering that kind of predictability takes enormous capital, careful regulatory navigation, and a constant balancing act between affordability, resilience, and decarbonization.

So let’s rewind to the falls in Spokane—and trace how Avista became what it is today, why it nearly didn’t survive, and what its next chapter might look like.

II. The Gilded Age Origins: Spokane Falls & Power (1889–1920s)

In the 1880s, Spokane didn’t grow. It surged.

What had been a frontier outpost started turning into the commercial center of eastern Washington and northern Idaho—an entrepôt for the region’s agriculture, cattle, lumber, and mining economies. The catalyst was steel and schedules: Spokane (then commonly called Spokane Falls) incorporated in 1881, and that same year the Northern Pacific Railway arrived. Suddenly the city wasn’t isolated. People, equipment, and money could move in—and goods could move out. A boomtown needs power, and Spokane was becoming one fast.

The city’s existing electricity provider, Edison Electric Illuminating Company, could see the problem coming. Demand was rising, but capacity wasn’t. So in 1889, the trustees went to Edison Electric’s financial backers—a group of businessmen in New York—with a proposal: build a hydroelectric station on the Spokane River. Make the river do the work. Scale electricity with the city.

The answer from the East Coast was, effectively, no.

And that rejection planted a seed that would echo through Avista’s entire history: the people closest to the asset tend to understand its value first. The Spokane River wasn’t an abstract line item to local business owners. It was right there, roaring through the center of town, throwing off power every minute of every day.

So the idea didn’t die. Ten Edison Electric shareholders pooled their own money, incorporated a new company in 1889, and formed Washington Water Power.

Then Spokane’s growth story turned into a survival story. Just four months after Washington Water Power was founded, the Great Fire of Spokane tore through downtown in August 1889, destroying more than 30 city blocks. It was catastrophe—and it was also a defining moment. With much of the distribution system burned out, employees improvised: barbed wire, baling wire, anything that could carry current. They strung lines from the corners of buildings and trees, rebuilding a skeleton grid in real time. As night fell, the company made it clear it wasn’t going anywhere: it was still open for business.

That urgency carried into the build. One of the company’s first engineers, Henry Herrick, pushed ahead on the Monroe Street power station, and on November 12, 1890, the project came online—the day Washington Water Power became operational.

Over the next couple decades, the pace didn’t slow. The company built six hydroelectric projects. It became an early leader in long-distance transmission, constructing one of the two longest and heaviest transmission lines in the world at the time. It also completed a major hydroelectric project that, in its era, was among the world’s standouts—featuring a 170-foot spillway and the largest turbines then in operation. The early utility business rewarded whoever could build big and build early. The economics were brutal and simple: once the infrastructure existed, spreading fixed costs across more customers created enormous advantages. The first builder didn’t just win customers—it built the moat.

But this wasn’t only a story of bigger dams and longer wires. There was also a very practical culture taking shape inside the company—innovation aimed at making electricity genuinely useful in daily life. In 1917, meter tester Lloyd Copeman designed the first automatic control for an electric range. Another employee, Guy Arthur, developed the automatic electric water heater. These weren’t moonshots. They were the kinds of inventions that turned electricity from a novelty into a necessity.

As the technology matured, so did the rules of the game. In this period, the basic regulatory framework for utilities began to take its modern shape: private utilities accepted an obligation to serve everyone at fair rates, and in return they got protection from competition and the opportunity to earn regulated returns on invested capital. That bargain transformed electricity from a risky, speculative business into the kind of steady enterprise that investors would later call “widow and orphan” stock.

And for Washington Water Power, geography sweetened the deal. Once you built the dam, the fuel was the river—and it didn’t send invoices. Hydroelectric power gave the company a structural cost advantage that regulation couldn’t wish away, and it turned those roaring falls into something even more valuable than spectacle: a foundation for a regional economy.

III. Mid-Century Expansion: Dams, Coal, and the Postwar Boom (1930s–1980s)

The 1930s brought a new kind of threat—one that wasn’t about technology or demand, but politics.

The New Deal didn’t just reshape the economy. It reshaped electricity. With public power expanding fast, the federal government started building generation at a scale that private utilities couldn’t match. The Bonneville Power Administration, paired with the Grand Coulee Dam (completed in 1942), poured huge volumes of low-cost, publicly owned electricity into the Northwest. And in Washington, public utility districts were empowered to do something that made every investor-owned utility sit up straight: condemn private utility assets and take them over at regulated prices.

For Washington Water Power, this era forced a hard question: could a private utility keep its franchise in a region where the government was now a competitor?

WWP survived where many didn’t, partly because it already had deep roots with customers—and partly because its territory wasn’t the kind of clean, simple service map where public power thrived. The Inland Northwest is a messy blend of city load, suburban growth, and mountainous terrain. Running it efficiently rewarded experience, coordination, and a single operator who knew the system. And, crucially, WWP already controlled many of the best hydro sites on the Spokane and Clark Fork rivers. The company had built early, and that head start mattered.

As the region grew, the company broadened what it sold and how it served. In 1958, it moved into natural gas in the most straightforward way possible: buying Spokane Natural Gas Company. And it wasn’t shy about owning things beyond wires and pipes. Its acquisition of the Spokane Street Railway Co. and development of Natatorium Park—moves that began back in the late 19th century—were early examples of a pattern: WWP was willing to collect a portfolio of non-energy businesses that generated real revenue alongside the utility.

Then came the postwar boom. The Inland Northwest expanded, and WWP expanded with it. But by the 1960s, the easy hydro era was ending. The rivers had powered the region’s rise, yet most of the practical hydro buildout was largely done. If the company wanted more electricity, it needed new generation—and like many Western utilities, it turned to coal.

That’s where Colstrip enters the story. The Colstrip power plant in eastern Montana—large, coal-fired, and jointly owned by multiple utilities—was the classic promise of thermal generation. It delivered steady baseload power whether the snowpack was thin or the rainfall missed. But it also tethered the company to a fuel that, over the following decades, would become harder to defend economically and environmentally.

At the time, though, it fit the era’s playbook: build for reliability, lock in supply, keep the system stable.

The diversification impulse didn’t stop. In 1960, the utility acquired the Spokane Industrial Park, becoming landlord to a site that housed dozens of businesses. In 1977, it formed Itron, a technology company focused on meter-reading equipment. The subtext of both moves was the same: a belief that a regional utility might need to become more than a utility to keep growing and stay relevant. That instinct would prove consequential later—because it didn’t always lead to safe places.

But if you were a utility investor in the 1980s, this was as good as it got. Regulation looked stable, customer counts grew with the region, and allowed returns on equity were regularly north of 12%. Utilities could pay dependable dividends, fund big capital projects through rate cases, and deliver slow, steady stock appreciation. The term “widow and orphan” stock wasn’t just a cliché—it was a business model.

For Washington Water Power, this period wasn’t about drama. It was about building, expanding, and compounding under a regulatory compact that seemed, at the time, like it would last forever.

IV. Deregulation Chaos & Identity Crisis (1990s–Early 2000s)

In the 1990s, electricity deregulation rolled across the U.S. with the kind of confidence that only big, elegant theories can generate. The pitch was simple and intoxicating: break up the old monopoly model, separate generation from the wires, let customers choose their supplier, and trust competition to deliver lower prices and more innovation.

For Washington Water Power, that wasn’t an abstract policy debate. It was an identity crisis. In a deregulated world, generation might stop being a protected, rate-based asset and start living on the open market. That could mean the company’s hydro system became either a gold mine of “merchant” power… or a stranded relic in a commodity business. Leadership had a decision to make: stay a conservative, regulated utility, or lean into the new world of wholesale markets and trading.

They didn’t just choose a strategy. They changed the company’s name to match it.

Founded in 1889 as Washington Water Power Company, the board approved a name change to Avista Corporation, effective January 1, 1999. The company began trading under the Avista name on Monday, January 4. Around the same time, it bought naming rights for Spokane’s minor league baseball park, Avista Stadium. The new name was meant to signal forward-looking ambition—Avista, derived from the Latin “vista,” a company with vision beyond its traditional boundaries.

But that reach nearly got the company killed.

Avista’s push into wholesale markets ran straight into the most infamous trading era in energy history. The California energy crisis of 2000–2001 showed what deregulated power could become at its worst: a system vulnerable to manipulation, volatility, and political blowback. Avista’s unregulated trading arm, Avista Energy, ended up caught in the fallout.

Federal investigators later examined a series of trades involving Avista Energy, Enron Power Marketing Inc., and Portland General Electric Co. Avista officials said they were unwittingly pulled into Enron “sleeve” trades—transactions that helped Enron route power to its affiliate, Portland General Electric, in a way that avoided rules against direct affiliated trading. Avista’s role, they contended, netted just $2,500 in fees.

The situation still dragged the company into years of scrutiny and legal exposure. Avista Energy received $15 million through a settlement with California utilities that accused it of manipulating spot energy prices during the 2000–2001 crisis. FERC investigators eventually cleared Avista Energy, saying it didn’t manipulate the market or knowingly assist others in trades that artificially inflated prices.

The legal hangover didn’t stop there. On September 27, 2002, Avista was sued for issuing false and misleading statements about its business and financial condition, including allegations that it failed to disclose highly risky energy trading activities involving Enron and Portland General Electric. On December 20, 2007, Avista agreed to a $9.5 million settlement.

By then, the lesson was unavoidable. Energy trading looked, from a distance, like a natural extension of owning generation. In reality, it demanded a different culture: different risk tolerance, different controls, different instincts. The same volatility that could produce trading profits in good markets could also turn into an existential threat when things broke.

So Avista backed out. In 2007, it sold its energy trading business to Coral Energy, a Royal Dutch Shell subsidiary. Avista Energy remained in name only while litigation continued.

This retreat—selling the trading arm and recommitting to the core regulated utility—was a key inflection point in Avista’s modern history. It was an admission that the diversification experiment hadn’t just underperformed. It had nearly sunk the company. And it set up the next chapter: the slow, disciplined work of rebuilding trust, repairing the balance sheet, and returning to what the company had always been best at—keeping the lights on.

V. Back to Basics: The Post-Crisis Rebuild (2004–2010)

After the trading-era scare, Avista’s comeback wasn’t powered by some flashy new strategy. It was powered by something much harder: restraint.

Under Scott Morris’s leadership, the company absorbed the aftershocks of the 2000–2001 crisis and started earning its way back to credibility. From the depths of late 2001, Avista’s total shareholder return rose sharply in the years that followed—up nearly 124 percent since December 2001, according to the company—beating regional utility peers and the S&P 400 MidCap Utility Index over that stretch. The dividend, which had become a symbol of stability again, was increased multiple times in the late 2000s.

But the numbers were the output, not the work.

The work was unglamorous and relentless. The balance sheet—stretched by trading losses, legal exposure, and the simple fact that utilities never stop needing capital—had to be repaired. Relationships with regulators, strained by controversy and mistrust, had to be rebuilt one rate case and one public meeting at a time. And maybe most importantly, Avista had to prove it could do the basics exceptionally well again: run a safe system, restore power quickly when storms hit, and invest in infrastructure without overreaching.

It helped that even before the crisis, the underlying regulated utility had been quietly changing in ways that mattered. One of the most important shifts was natural gas. What looked like a side business when Spokane Natural Gas was acquired in 1958 became a real growth engine as customers moved toward cleaner-burning heating. In the early 1990s, the number of natural gas customers grew rapidly—rising from about 85,000 to roughly 230,000 between 1989 and 1995.

And as Avista stabilized, it started looking for growth again—but only growth that fit inside the lines.

That’s why, years later, the company’s move into Alaska reads like a direct reaction to the trading debacle. In 2014, Avista acquired Alaska Electric Light & Power, the electric utility serving Juneau, through an all-stock deal valued at $170 million. The target wasn’t a speculative business. It was a regulated utility with a defined service territory—exactly the kind of operation Avista understood. Alaska Electric Light & Power traced its roots back to 1893, when Willis Thorpe founded it, and it was known as Alaska’s oldest electrical utility and oldest continuously operating corporation.

Structurally, the transaction was built to avoid reopening old wounds. The seller was Alaska Energy and Resources Company (AERC), which became a wholly owned subsidiary of Avista, and AEL&P became AERC’s primary subsidiary. Avista issued about 4.5 million new shares at $32.46 per share, reflecting the $170 million purchase price, net of debt and closing adjustments. The all-stock structure mattered: it preserved Avista’s balance sheet while adding a hydro-heavy utility—another system where water, not fuel invoices, did the heavy lifting.

Back at home, Avista also began laying the technical foundation for its next era. This was the early phase of grid modernization: smart meters, distribution automation, and behind-the-scenes technology upgrades that most customers never notice—until the day the grid has to do something it was never designed for, like integrate distributed energy resources at scale.

In other words, the post-crisis rebuild wasn’t just about getting back to “safe.” It was about getting back to “ready.”

VI. The Environmental Pivot: Coal Exit & Clean Energy Transition (2010–2020)

By the 2010s, the Colstrip bet started to look less like “reliable baseload” and more like a liability with a countdown timer.

Avista—one of six owners of the Colstrip coal plant in eastern Montana—reached a settlement with Washington state utility regulators that set the company on a much faster path out. Instead of exiting units 3 and 4 in the mid-2030s, as it had once targeted, Avista committed to stop investing in Colstrip after 2025.

It was the most consequential strategic shift Avista had made since its post-Enron retreat back to the regulated core. And it didn’t happen because of one single policy change or one single bad quarter. It happened because several forces stacked up at once: Washington’s tightening climate agenda, the way cheap natural gas reshaped the economics of power, and the growing realization that coal plants weren’t just dirty—they were increasingly at risk of becoming stranded assets.

Jason Thackston, Avista’s senior vice president and chief strategy and clean energy officer, put it plainly: the company had already concluded it wasn’t economically feasible to keep its Colstrip ownership beyond 2025, even if Washington law hadn’t required a coal exit. “Yes, it complies with the legislation,” he said, “but it was also the right decision to make from our perspective regardless of that legislation.”

The mechanics mattered. Under the agreement, Avista would transfer its 15% ownership share of Colstrip units 3 and 4 to NorthWestern Energy, a South Dakota-based utility that still saw value in coal generation for its Montana customers. Colstrip’s older units 1 and 2 had already shut down in 2020. Units 3 and 4—placed into service in 1984 and 1986—were the newer ones, and together they supplied Avista with 222 megawatts, around 8% of what it needed to serve customer load.

The transfer was set to begin on Dec. 31. After that, Avista would no longer own any coal-fired generation—bringing it into compliance with Washington’s requirement that electric utilities stop using coal-fired resources. Avista’s own analysis also pointed to the same conclusion from a customer-cost perspective: after 2025, Colstrip wouldn’t pencil out for customers in Washington and Idaho.

Of course, exiting Colstrip wasn’t just a spreadsheet decision. It was a multi-state political problem. Montana’s leadership, tied closely to coal mining and the plant’s role in rural economies, resisted early closure. Washington’s climate advocates pushed hard for a faster timeline. And NorthWestern—operating in a very different regulatory and political environment—became the practical solution: the buyer willing to take the asset that Avista needed to put down.

But here’s the part that made the deal more than an exit. Avista kept its rights to the Colstrip transmission system. The company could walk away from the coal plant while still holding onto the high-voltage highways that connect Montana’s generation to the broader region. As Thackston described it, the transaction was “the result of several years of work and discussions among all owners of Colstrip,” aimed at finding a commercial solution that let Avista exit by the end of 2025 while still meeting the needs of other owners and stakeholders, including NorthWestern and the state of Montana.

That transmission retention is the quiet masterstroke. The same lines that once carried coal-fired electrons can carry renewable power next. Montana’s wind resources—among the best in North America—can now reach Avista’s customers through infrastructure that was built for the old era, repurposed for the new one. The past becomes the pathway to the future.

This shift also fit neatly into Washington’s policy framework. In 2019, the state passed the Clean Energy Transformation Act (CETA), requiring electric supply to be greenhouse-gas neutral by 2030 and 100% renewable or generated from zero-carbon resources by 2045. Avista’s Clean Energy Implementation Plan (CEIP) became the company’s road map—specific actions over the next four years, from 2022 to 2025, designed to show measurable progress toward those targets.

And suddenly, Avista’s oldest advantage became one of its most modern ones. What once looked like historical luck—so much hydro in the portfolio—started to look like strategic positioning. Avista’s plan laid out its path toward a carbon-neutral electricity supply by 2030 and a 100% renewable or non-emitting supply by 2045. Already, more than half of its generating potential came from hydropower, biomass, wind, and solar. The CEIP was about building on that base, using energy efficiency and demand response to stretch clean supply further—and proving, year by year, that the company could decarbonize without losing the one thing a utility can’t trade away: reliability.

VII. The Takeover Drama: Hydro One Acquisition Attempt (2017–2019)

By the late 2010s, Avista had done the hard work of stabilizing after the trading era and starting its clean-energy pivot. Then, in July 2017, it dropped a different kind of bombshell: it had agreed to sell itself.

The buyer was Hydro One, Ontario’s biggest transmission and distribution utility. The headline number was $5.3 billion. The pitch was scale: a larger combined company, headquartered in Spokane, with a much bigger asset base and more than 2 million end customers. Avista—one of the smaller regulated utilities in North America—would become a wholly owned subsidiary inside a much larger organization.

On the surface, the deal looked like the standard utility M&A playbook: bigger balance sheet, shared expertise, potential cost savings, and a premium for shareholders. And shareholders loved it. Avista’s investors approved the sale by an overwhelming margin—98 percent in favor.

But utilities don’t ultimately belong to shareholders. They belong to regulators and the communities they serve.

When the deal hit public hearings, that reality came into focus fast. At the first major public hearing in Spokane Valley in April 2018, customers raised a concern that wasn’t about synergies or price. It was about control. Hydro One was 47% owned by the province of Ontario, and people didn’t like the idea of their local utility being tethered—directly or indirectly—to another government’s politics.

Then Ontario’s politics detonated the timeline.

In July 2018, newly elected Premier Doug Ford forced out Hydro One’s CEO and board in a very public political shakeup. Overnight, what had looked like a conventional cross-border utility deal turned into a live demonstration of the exact risk opponents had been warning about: if politics could reach into Hydro One that easily in Ontario, how insulated would Avista really be in Spokane?

Washington regulators didn’t buy the argument that Ontario was merely a “passive investor.” After the leadership purge, that claim sounded less like reassurance and more like wishful thinking. The Washington Utilities and Transportation Commission ultimately concluded the deal wouldn’t adequately protect Avista or its customers from political and financial risk—an unusually blunt stance in a sector where mergers are often approved with conditions.

Public sentiment wasn’t subtle, either. The UTC held four public comment hearings and received 471 comments. The vast majority opposed the merger, with only a small number in favor and the rest undecided. In its order, the UTC wrote that it was evident decisions affecting Hydro One and Avista could be subject to political considerations, and that future provincial leaders might take actions that harm the companies, shareholders, or customers. Regulators also pointed to a structural problem: there was nothing preventing Ontario from passing legislation that could undercut the protective commitments Hydro One had made to Avista ratepayers.

Idaho’s rejection came from a different angle, and it was even more definitive. Idaho regulators pointed to a narrow anti-public power statute that prohibits public takeovers of investor-owned utilities. Because Ontario’s direct and indirect control made Hydro One effectively a publicly owned utility under Idaho’s interpretation, Idaho concluded it simply couldn’t buy an investor-owned utility’s assets in the state.

With denials in both Washington and Idaho, the deal was dead. Hydro One and Avista’s boards each decided it wasn’t realistic to reverse the orders in time, and they terminated the merger. Under the agreement, Hydro One paid Avista a $103 million termination fee.

Avista CEO Scott L. Morris struck the tone you’d expect from a utility leader trying to close a bruising chapter without rattling confidence: disappointed, grateful to the teams involved, and emphatic about what came next—Avista would remain “a strong, vibrant, and independent utility,” focused on customers, employees, communities, and shareholders.

And that’s the real takeaway from the whole episode. The failed merger exposed something you don’t see in discounted cash flow models: in the utility business, local identity is an asset. Regulatory relationships are an asset. And when a community has depended on the same company for more than a century, “keep it local” stops being a slogan and starts functioning like a moat.

VIII. Present Day: Energy Transition Accelerates (2020–Present)

After the Hydro One deal fell apart, Avista didn’t get the luxury of a long exhale. The 2020s arrived with a new mandate: modernize the system, decarbonize the supply, and do it all while customers are more cost-sensitive than ever.

By the end of 2024, the company was framing the year as proof it could execute through pressure. Avista reported improved consolidated earnings even as power supply and operating costs rose. President and CEO Heather Rosentrater said she was proud of the performance and pointed to what mattered most in a utility: the infrastructure. In 2024, Avista made record levels of capital investment aimed at serving customers better, and Rosentrater signaled what the next phase would look like—pursuing transmission projects and bringing on additional large-load customers, but only where they fit the company’s strategic priorities.

Financially, Avista reported consolidated earnings per diluted share of $2.29 for 2024 and initiated 2025 guidance of $2.52 to $2.72 per share. Within that outlook, Avista Utilities’ midpoint assumed a $0.12 negative impact from the Energy Recovery Mechanism (ERM), under the 90% customer and 10% company sharing band. Alaska Electric Light & Power, the Juneau utility Avista acquired through AERC, was expected to contribute about $0.09 to $0.11 per share in 2025.

But the bigger story in the present day isn’t a quarterly print. It’s leadership—and continuity.

Rosentrater’s move into the CEO seat marked a generational shift. In August 2024, Avista announced that the former barista and Pizza Hut employee would become the first woman CEO in the company’s 135-year history. She’s a Spokane native, raised in Millwood, and she started at Avista in 1996 as an engineering technician at Avista Labs while still an undergraduate at Gonzaga University.

And for a company whose “local” identity became a moat during the Hydro One fight, her roots aren’t a footnote—they’re part of the brand. Rosentrater’s great-great-grandfather homesteaded near Hillyard. Her grandmother, Bessie, still lives in Spokane Valley and still gets her monthly Avista bill—just like the hundreds of thousands of other electricity and natural gas customers Avista serves across four states. Just over a year after becoming Avista’s first female president in October 2023, she became its first female CEO.

Then nature reminded everyone what the stakes really are.

In late June 2021, the Pacific Northwest heat dome pushed the grid—and the region—into unfamiliar territory. It became Washington state’s deadliest recorded weather event, lasting roughly from June 25 to July 2, with temperatures reaching as high as 120°F in parts of the state and staying dangerously hot overnight. Researchers described it as the kind of event that would have been extraordinarily rare in the late 19th century, but with about 2°C of global warming—levels predicted by mid-century—an event of similar magnitude could happen every 5 to 15 years. The heatwave’s impacts were brutal: hundreds of deaths, marine life die-offs, increased wildfires, crop losses, and even river flooding.

For utilities across the West, climate risk isn’t theoretical anymore—it’s operational. And wildfire has emerged as the existential threat, made stark by PG&E’s bankruptcy and ongoing liability exposure.

Avista’s response has been to treat wildfire like a core system design constraint. The company developed an enhanced 10-year Wildfire Resiliency Plan focused on preventing ignition and reducing damage in fire-prone areas. It was built through internal workshops, industry research, and collaboration with state and local fire and land management agencies. The plan emphasizes hardening infrastructure—replacing or strengthening equipment where the risk is highest—to reduce the chance that the grid itself becomes a spark source.

Some of this is also about operating differently. Avista has used an approach known as Fire Safety Mode for more than two decades: during high-risk weather, lines can be kept de-energized until crews confirm it’s safe to restore power. It’s a trade-off no one loves, but it’s rooted in the modern reality of Western utilities—sometimes the safest power is the power you don’t deliver until conditions improve. Alongside that, Avista has invested in grid-hardening projects like replacing wooden poles with steel, adding fire-retardant materials, and undergrounding lines in certain locations.

Policy started moving, too. In April 2025, bills passed in both Washington and Idaho that provided for approval of wildfire mitigation plans, and in Washington, created an opportunity to securitize certain costs associated with disasters such as wildfire. In plain terms: legislatures were acknowledging what utilities and firefighters already knew—wildfire is now a critical, system-level issue, and the financial tools have to catch up.

Meanwhile, the clean-energy transition kept accelerating. Avista proposed increasing the amount of clean energy delivered to Washington customers from 66% in 2026 to 76.5% by 2029.

And the company’s plan for getting there isn’t only about building new generation. It’s also about shaping demand. Between 2026 and 2029, Avista planned to launch new demand response programs that could reduce electricity usage by up to 55 megawatts during peak periods—those hottest summer afternoons and coldest winter mornings when the system is strained. The toolbox includes things like smart thermostats, battery storage, and other programs designed to help customers shift or lower their usage when demand is highest.

IX. The Utility Business Model Deep Dive

To understand Avista, you have to understand the strange little economic machine that is a regulated utility. It’s a model that was mostly locked in a century ago, and yet it still runs the modern grid.

Everything starts with rate base—also called the regulated asset base. When Avista builds a substation, upgrades a transmission line, replaces poles, or rolls out smart meters, those projects don’t just improve the system. They become assets regulators recognize as “used and useful” to serve customers. Those approved investments go into rate base.

Then comes the bargain. Regulators set the prices customers pay so that Avista can recover its operating costs and depreciation, and earn a return on the capital it invested. In practice, that means Avista’s earnings aren’t driven by winning customers or jacking up prices. They’re driven by building infrastructure, running it safely and reliably, and then making the case—over and over in public proceedings—that those investments were necessary and should be paid for over time.

That’s why the monopoly part matters. Avista Utilities has an exclusive franchise in its service territories in eastern Washington, northern Idaho, and parts of Oregon. No one is building a second set of power lines down the same streets to compete. The “competition” is really the regulatory process, where consumer advocates, large industrial customers, and commissions act as stand-ins for the public and scrutinize everything from spending plans to executive decisions.

If Avista executes well and keeps regulators onside, it gets a relatively predictable earnings stream. In current regulatory proceedings, allowed returns on equity have generally landed in the ballpark of 9% to 10.5%. That doesn’t mean the business is risk-free—far from it. But it does mean the rules of the game are more knowable than in almost any other industry.

The flip side is capital intensity. Utilities are, by design, perpetual builders. Avista expects about $3 billion of total capital expenditures over the five-year period ending in 2029, translating into roughly mid-single-digit annual growth. And even that projection doesn’t include what could come on top—additional generation from its all-source request for proposal, major transmission projects, or the infrastructure needed to serve new large-load customers.

So the loop looks like this: invest in rate base, earn the allowed return, fund the next round of investment, and—if all goes to plan—raise the dividend along the way. Because this machine needs constant fuel, it regularly taps capital markets. In 2025, Avista expected to issue $120 million of long-term debt and up to $80 million of common stock, including $16 million issued in the first quarter.

One more concept matters here, because it changes the incentives. Revenue decoupling—used in many progressive jurisdictions—loosens the link between how much electricity customers use and how much revenue the utility is allowed to collect. The point is simple: utilities shouldn’t be financially punished when customers conserve energy or when weather swings load up and down. Decoupling helps stabilize fixed-cost recovery and removes the built-in bias against energy efficiency.

And finally, there’s the shareholder promise that’s made utilities famous: the dividend. As of the figures cited here, Avista’s annual dividend was $1.96 per share, paid quarterly, with a yield around 4.7% and a payout ratio in the low-80% range. The company had grown its dividend for 22 consecutive years, with recent annual growth running in the low single digits.

That track record is why utilities attract income investors in the first place: not because they’re exciting, but because they’re engineered for steadiness. The catch is that steadiness isn’t free. It’s built—pole by pole, transformer by transformer—and then negotiated, rate case by rate case.

X. Strategic Frameworks: Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers

If you zoom out, Avista’s world looks almost unfairly stable. But it’s stable for specific reasons. Two frameworks help make that legible: Michael Porter’s Five Forces, which explains how competition shows up (or doesn’t) in an industry, and Hamilton Helmer’s Seven Powers, which pinpoints where durable advantage actually comes from.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: Very Low. It’s hard to overstate how closed this market is. To “compete” with Avista, a newcomer would need to build an entire parallel grid—generation, transmission, distribution—across mountains and cities, then spend years getting regulatory permission to operate it. Franchise territories are legally protected. In American business, this is about as close as you get to a sanctioned monopoly.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Moderate. Utilities buy a lot of inputs, and not all of them are commodities. Natural gas suppliers have leverage, but fuel costs are often passed through to customers under regulatory mechanisms. On the equipment side, manufacturers of transformers, turbines, and cable have consolidated, which can push prices up and stretch lead times. Avista’s advantage here is structural: its hydro fleet means less exposure to fuel markets than peers that lean heavily on thermal generation.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: Low to Moderate. Customers can’t simply pick another provider. That’s the monopoly. But the public still has leverage, because regulators act as the customer’s proxy, and they have real power over rates, investment approvals, and allowed returns. Large industrial customers can also carry outsized influence in rate cases. And over time, distributed generation—rooftop solar, batteries, and other behind-the-meter options—creates a limited form of “exit,” even if most customers won’t go fully off-grid.

Threat of Substitutes: Low but Growing. For most of modern history, grid electricity had no real substitute. That’s changing at the edges. Solar-plus-storage is getting more capable, and for certain customers it can shave peak demand or provide backup power. Fully off-grid living is still impractical for most people because of cost and reliability, but the direction is clear: distributed resources are the most credible long-term substitute to the traditional utility model. On the natural gas side, substitution pressure is more immediate as heat pumps and induction cooking become more common.

Competitive Rivalry: Very Low. Avista doesn’t fight another utility for residential customers on the same street. Rivalry shows up elsewhere: in rate cases, in the competition for capital, and increasingly in whether large, sophisticated customers decide to self-supply part of their energy needs. There’s also an indirect kind of rivalry, where commissions benchmark utilities against peers when setting allowed returns and evaluating performance.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: Strong. Utilities are built on fixed costs. The larger the customer base, the more you can spread the expense of systems, crews, control rooms, and maintenance. Generation also tends to reward scale, and the wires business is a natural monopoly by design. Avista sits in a sweet spot: big enough to run modern, sophisticated operations, but not so large that bureaucracy becomes its own drag.

Network Economics: Moderate. This isn’t a social network; Avista doesn’t get stronger because more people “join.” But the grid does become more valuable as it becomes more interconnected and more flexible, especially for reliability. And looking forward, aggregation—virtual power plants, coordinated batteries, and managed demand response—could make “network-like” advantages more meaningful.

Counter-Positioning: Not Applicable. The regulated utility model isn’t just Avista’s preference; it’s the structure of the game. New entrants like solar installers or aggregators can take slices of value, but they can’t replicate the core function of being the obligated, regulated provider of last resort.

Switching Costs: Maximum. In most of Avista’s territory, switching isn’t hard—it’s impossible. Even where large customers can sometimes arrange alternatives, it’s complex and rare. The grid is sunk infrastructure, and the monopoly is legally enforced. This is one of the strongest forms of switching costs you’ll ever see.

Branding: Weak to Moderate. Nobody wears an Avista hat. Most customers think about their utility when the bill arrives or the power goes out. But reputation matters intensely in the places that count: regulator trust, community goodwill, and credibility during crises. The Hydro One episode proved “local” can be a real asset, not just a slogan.

Cornered Resource: Strong. This is the crown jewel. Avista’s hydro system is low-cost and non-emitting, and it was largely built in an era when building dams was still possible. Today, it effectively isn’t. Environmental regulation, permitting complexity, and public opposition make new large hydro projects extraordinarily difficult. So those old water rights, permits, and sites function like a locked-up resource. The 19th-century decision to build hydro became a 21st-century competitive advantage.

Process Power: Moderate. Running a utility well is a craft: safety culture, storm response, grid operations, regulatory navigation, long-range planning. That institutional knowledge compounds over decades, and it’s hard to copy quickly. It’s not invincible, but it’s real—and in this industry, mistakes can be catastrophic.

Overall Assessment: Avista’s advantage comes from three core realities: a legally protected monopoly (switching costs), irreplaceable hydro assets (cornered resource), and the scale economics baked into utility operations. The failed Hydro One deal added another layer you can’t easily model: local identity and regulatory relationships can protect independence. And as the energy transition accelerates, Avista’s hydro-heavy foundation may become more valuable, not less.

XI. Bull vs. Bear Case

The Bull Case

A clean-energy tailwind sets Avista up well for the next few decades. The company’s hydro-heavy portfolio—once just the byproduct of being founded next to a powerful river—now reads like a durable edge. Avista has described itself as “one of the cleanest utilities when it comes to greenhouse gases,” and it has pointed to comparatively low prices versus other investor-owned utilities. In the most recent data, nearly 60% of its generation mix came from renewables, including about 48% from hydro.

Avista also sells something the modern economy can’t function without: essential infrastructure. Electrification is the demand story of this era. Every EV that plugs in, every heat pump that replaces a furnace, every large customer that needs reliable, cleaner power adds load. And in the regulated model, load growth is the most straightforward kind of growth there is.

Put those together with Avista’s own long-term target—4% to 6% earnings growth from its forecast 2025 base year—and the appeal becomes clear. Pair mid-single-digit earnings growth with a dividend yield north of 4%, and you can see a path to high single-digit total returns without needing heroic assumptions.

Regulation is another part of the bull case. Avista operates in Washington, Idaho, and Oregon—states that may be demanding, but generally understand the basic trade-off: if you want reliability and investment, the utility has to remain financially healthy. That’s not guaranteed everywhere, and it matters.

And compared with the nightmare scenarios elsewhere, Avista’s operating footprint looks relatively manageable. California has shown what catastrophic wildfire liability can do to a utility. Texas has shown what market design failure can do to reliability. The Inland Northwest has real risks—wildfire, heat, drought that can affect hydro output—but they’re risks the company has historically been able to plan for and operate through.

Finally, there’s the post-Hydro One reset. Avista proved it could keep moving forward as a standalone regional utility, and the $103 million termination fee helped offset the very real costs of a deal that made it far down the track before regulators shut it down.

The Bear Case

The first bear argument is the one that hits the entire sector: interest rates. When rates rise, utility dividends look less special compared to bonds, valuations tend to compress, and the cost of capital for all that required infrastructure spending goes up. If “higher for longer” persists, that pressure can linger.

Then there’s regulatory risk—the permanent shadow over every regulated utility. Rate cases can go sideways. Costs can be disallowed. Allowed returns can land below what investors expect. And even when outcomes look “fine” on paper, the timing can hurt: spending often happens now, recovery happens later, and that lag can quietly grind down realized returns.

Natural gas adds another layer of uncertainty. Today, the gas distribution business can be stable and profitable. But the long arc of decarbonization and building electrification raises an uncomfortable question: what happens to long-lived gas infrastructure if policy, technology, and customer behavior keep shifting away from it?

Wildfire risk is the existential one. Avista is not PG&E. But the underlying climate trend doesn’t care. Fire seasons are getting longer and more intense, and even strong prevention programs can’t eliminate the possibility of a single extreme event creating massive liability. Insurance availability and pricing are part of that same problem set.

And while it’s not an immediate threat, technology could still chip away at the classic utility model. Distributed solar plus batteries gives some customers more options over time. If enough load starts self-supplying, utilities can end up with a harder-to-serve residual customer base and a tougher politics of cost recovery.

Finally, growth is not explosive. Avista has projected customer energy demand growth of about 0.9% per year and winter peak demand growth of about 1.14% per year. That’s real growth, but it’s not the Sun Belt. Compared with faster-growing regions, it can make Avista look less exciting on the margin.

Key Metrics to Watch

Two things tell you most of what you need to know as this story keeps unfolding.

First: rate case outcomes and the direction of allowed returns on equity. The spread between what regulators allow and what capital actually costs is the difference between compounding steadily and treading water. Watch not just the headline ROE, but the full revenue requirement decisions and whether the outcomes support timely cost recovery.

Second: capital spending relative to rate base growth—and the lag in between. The utility “machine” only works if investments make it into rate base and start earning returns on a reasonable timeline. When spending gets ahead of recovery, realized returns can slip even if the allowed returns look healthy. Track the relationship between capex plans, rate base growth, and what regulators ultimately approve.

XII. Epilogue: The Next Chapter

There’s a paradox baked into Avista as it heads toward its 136th year. This is, in theory, one of the most boring businesses in America: keep the lights on, keep the heat running, and do it so consistently that customers barely notice you exist.

And yet almost everything around that simple mission is changing at once.

The energy transition is both the threat and the opportunity. Avista’s hydroelectric foundation—built when electricity itself still felt like a novelty—now looks like a head start in a carbon-constrained world. Founded on clean hydropower on the Spokane River, Avista has long leaned on renewable generation, and its portfolio is already more than half renewable. The work now is to keep pushing: adding new renewable resources, getting more efficient with how electricity and natural gas are used, and modernizing the technology that makes the grid flexible enough for what comes next.

The uncomfortable truth is that the next era doesn’t come with clean answers. Will distributed energy resources—rooftop solar, batteries, demand response—chip away at the centralized utility model, or will utilities absorb them into something stronger and more resilient? Can affordability survive decarbonization, or do climate-driven investments eventually push rates into political backlash? And as extreme weather becomes less “edge case” and more “operating reality,” who actually pays for resilience?

Avista is trying to thread all of those needles at the same time. It’s preparing to meet state requirements, including the mandate to stop using coal by the end of 2025. It’s hardening the system against expanding wildfire danger. And it’s doing all of that in a world where the company faces the same inflationary pressures as everyone else—except its shopping list includes transformers, poles, wire, and specialized equipment with long lead times.

“And I think this is the challenge for Heather and the team going forward. We are trying to meet our climate, our carbon reduction goals, but yet we need to be mindful of affordability and what the impacts are for our customers.”

For investors, this is a very different Avista than the one that nearly blew itself up chasing energy trading profits two decades ago. Today’s company is clearer about what it is: a regional utility serving the Inland Northwest and Alaska, powered in large part by irreplaceable hydro assets, delivering natural gas through regulated pipes, and focused on the slow, disciplined work of infrastructure investment and operational execution.

The Hydro One saga made the point in a way no strategy deck ever could: independence has value, and local matters. In a world of roll-ups and scale-for-scale’s-sake consolidation, Avista’s identity—its roots, its relationships, its credibility in the communities it serves—proved to be a real asset.

“My family’s history in the area extends back to the founding of Avista, what was then called Washington Water Power, and the Spokane Falls has been the backdrop of my career,” said Rosentrater. “Having grown up in the area, including attending Gonzaga University, I am extremely honored to help continue Avista’s long-standing legacy of supporting community vitality through energy. It’s an incredible time to be in the energy industry. We have important work ahead of us to achieve our clean energy goals safely, responsibly, and affordably while remaining focused on our financial results.”

Sometimes the best strategy really is knowing what you’re good at—and staying in your lane. For Avista, that lane runs through Spokane and out across mountains, forests, and small towns, past dams that still turn the same falling water into power. The water still falls. The power still flows. And the company still serves.

XIII. Further Resources

Top 10 Long-Form References:

- Avista Corporation Annual Reports & Investor Presentations (2015-present) - The best primary sources for how Avista explains its strategy, capital plans, and performance in its own words

- Washington UTC Dockets - The detailed paper trail behind rate cases and the Hydro One acquisition proceedings

- "The Power Makers: The History of American Electric Utilities" by Richard Hirsh - A clear history of how the U.S. utility model formed and why it still looks the way it does

- "Powering the Dream: The History of Green Technology" by Alexis Madrigal - Useful context for how “clean” became a central organizing principle for modern energy

- "Energy and Civilization: A History" by Vaclav Smil - The long-view lens on how energy systems evolve, and why transitions are slower and messier than we expect

- S&P Global Market Intelligence Utility Reports - Sector-level comparisons and benchmarking across regulated utilities

- Regional economic studies from the Spokane Journal of Business - Local reporting that helps connect Avista’s decisions to the communities and economies it serves

- Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) filings - The deeper mechanics of transmission, markets, and how regional power flows actually get governed

- Academic papers on utility business models and energy transition (MIT, Stanford, Berkeley energy institutes) - Research on regulation, decarbonization pathways, and the future of the grid

- "The Grid: The Fraying Wires Between Americans and Our Energy Future" by Gretchen Bakke - A readable tour of the hidden complexity—and fragility—of the infrastructure we all depend on

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music