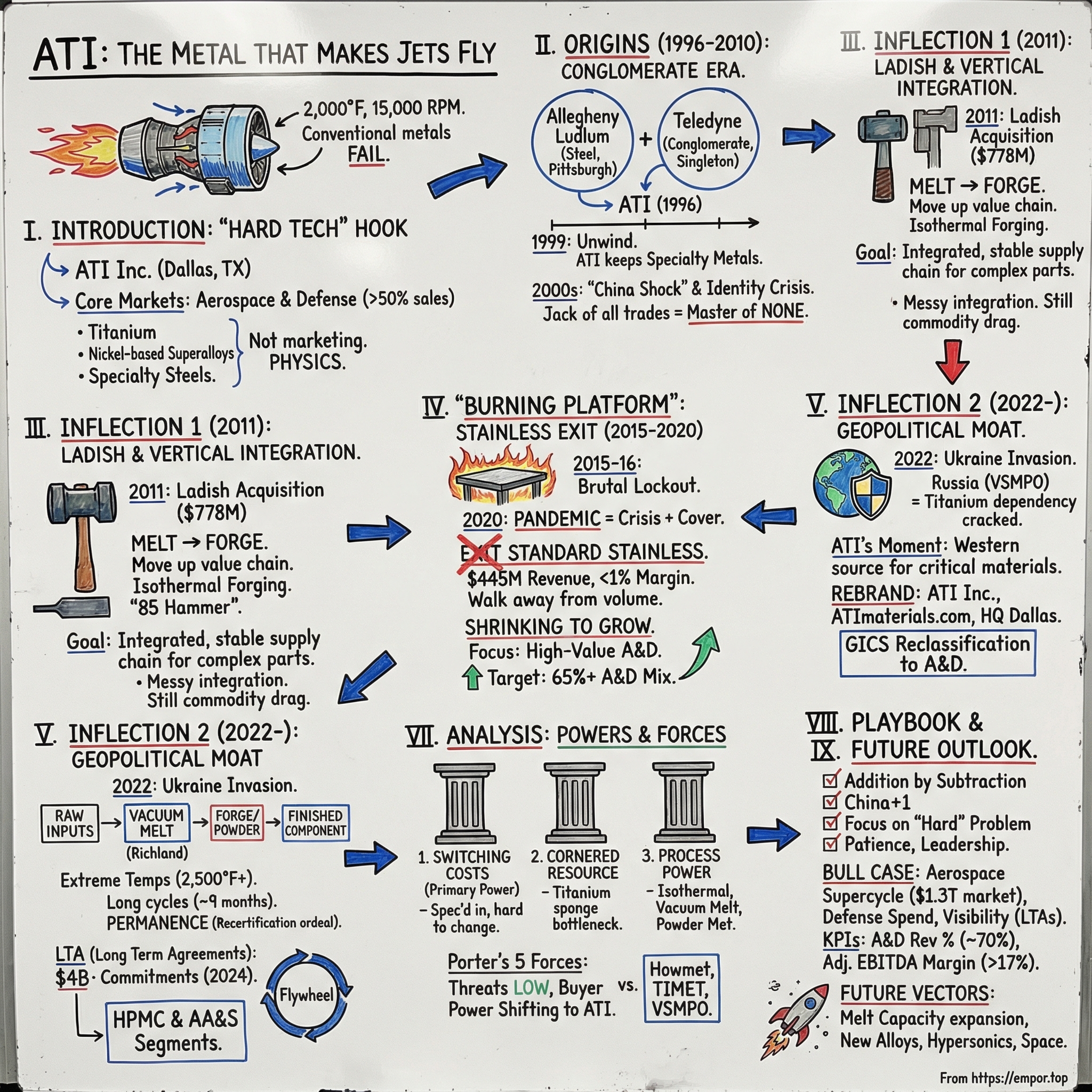

ATI: The Metal That Makes Jets Fly

I. Introduction & The "Hard Tech" Hook

Inside a jet engine burning at roughly 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit, conventional metals don’t just struggle. They fail. Discs spin at 15,000 RPM. Blades take forces that would crush ordinary steel. Casings hold back pressures that, if they let go, don’t fail gracefully. Modern flight depends on a small group of companies that can make metals survive that world.

One of them operates far from the glamour of aviation, out of a nondescript corporate office in Dallas, Texas. And yet without what it makes, a huge portion of the commercial planes in the sky simply wouldn’t fly.

ATI Inc. isn’t a household name. Most people at 35,000 feet have never heard it. But ATI’s core markets are aerospace and defense, with commercial jet engines alone making up more than half of sales. And ATI’s materials and components show up across virtually every major commercial platform flying today. That isn’t marketing. It’s physics. Nickel-based superalloys in a LEAP engine. Titanium forgings in a 787 landing gear. Specialty steels in an F-35 fighter. This is the leading edge of what humans can ask metal to do.

What does ATI actually make? High-performance materials: titanium and titanium-based alloys; nickel- and cobalt-based alloys and superalloys; advanced powder alloys and other specialty materials; metallic powder alloys. It sells them in long product forms like ingot, billet, bar, rod, wire, shapes and rectangles, and seamless tubes. And it goes further, producing precision forgings, components, and machined parts. If that sounds like a chemistry set, it is—just one that runs at temperatures and pressures that would destroy ordinary materials.

Here’s the part investors tend to miss: ATI didn’t start out as an aerospace pure-play. Chief operating officer Kimberly Fields described the company’s transformation as a diamond in the rough. “What ATI achieved during the pandemic is similar to a jeweler applying a cutting tool to a diamond in the rough, honing, sharpening, gaining the edge that shows off our capabilities brilliantly.”

That’s the theme of this story: “Shrinking to Grow.” Over the last decade, ATI made a bet that looked almost self-destructive in the moment. Allegheny Technologies Incorporated announced that it was exiting standard stainless sheet products, streamlining its production footprint, and investing in enhanced capabilities to accelerate a high-value strategy focused primarily on aerospace and defense. “We are taking decisive action to become a more profitable company by further sharpening our focus on the highest-value opportunities for our business,” said Robert S. Wetherbee, ATI President and Chief Executive Officer. “By shedding a low-margin product line and optimizing our footprint, we are redeploying resources to an aerospace and defense-centered portfolio, expanding margins and driving returns to generate significant value for our shareholders.”

At the time, the decision to walk away from nearly half a billion dollars in annual revenue sounded crazy on Wall Street. In hindsight, it reads like one of the most prescient industrial pivots of the decade.

II. Origins: The Conglomerate Era (1996 – 2010)

To understand where ATI ended up, you have to start with where it began: a collision between two companies with completely different DNA.

On August 15, 1996, Southern California-based Teledyne merged with Pittsburgh-based Allegheny Ludlum Corporation. It was pitched as a merger of equals. Allegheny Ludlum was doing roughly $1.8 billion a year in revenue; Teledyne was around $1.3 billion. But culturally, they weren’t equals at all.

Allegheny Ludlum was old-school Pittsburgh steel. Incorporated in 1901 as Allegheny Steel & Iron, it helped write the early playbook for American specialty metals. It was the first to use an electric furnace to make alloys. It commercialized stainless steel in the United States and won its first patent in 1924. Its stainless ended up in places like the Chrysler Building and even in trim for the Ford Model A. This was a company built on industrial scale, union labor, and a century of steel heritage.

Teledyne came from a different universe. It was the creation of Henry Singleton—electrical engineer, business executive, rancher, and a major contributor to aircraft inertial guidance who was elected to the National Academy of Engineering. He co-founded Teledyne and ran it for three decades, turning it into one of the most celebrated conglomerates in American history.

Singleton’s reputation became legend. Warren Buffett is quoted as saying, “Henry Singleton of Teledyne has the best operating and capital deployment record in American business.” Singleton’s tenure followed a three-part rhythm: expand through acquisitions, buy back stock aggressively, then spin pieces out. Between 1960 and 1969, he acquired 130 companies across a wide range of industries, sticking to a disciplined rule of buying profitable businesses at no more than 12 times earnings. Then he executed one of the most extreme buyback programs corporate America had ever seen—repurchasing about 90% of Teledyne’s shares over 12 years and driving earnings per share up dramatically in the process.

By 1996, though, Teledyne was vulnerable. The company successfully fought off a challenge, but one thing stood out: Teledyne’s pension fund had a surplus of $928 million, and that attracted attention. To head off further hostile interest, Allegheny Ludlum stepped in as a white knight.

The merger produced something that looked coherent on a press release and messy in real life. The combined company became Allegheny Teledyne, Inc. (ATI), headquartered in Pittsburgh. After reorganizing, it operated in three segments: Aerospace and Electronics, Specialty Metals, and Consumer Products.

It didn’t take long for management to realize the contradictions were structural, not cosmetic. ATI eventually chose to unwind the mash-up. On November 29, 1999, three separate companies were formed: Teledyne Technologies Incorporated, Allegheny Technologies Incorporated, and Water Pik Technologies, Inc. Allegheny Technologies kept the specialty metals heritage—both the commodity stainless business and the high-tech alloys that had come along with Teledyne.

And that’s how ATI entered the 2000s with an identity crisis baked in. In the same corporate family, you could find products that belonged in a kitchen drawer and products that belonged inside a jet engine.

One of the reasons the jet-engine side existed at all traces back to James Nisbet, founder of Allvac Metals Company, which came into ATI through the 1996 Teledyne merger. Nisbet had been a GE metallurgist, experimenting in the 1940s and 1950s with vacuum melting of nickel and other alloys for high-temperature aircraft and jet engines. He became convinced vacuum melting could become a commercial breakthrough for producing high-performance superalloys. In 1957, he founded Allvac to pursue that mission. It worked: Allvac grew into a world leader in superalloys for jet engines, gas turbines, and other extreme-temperature applications—exactly the kind of capability that would later define ATI’s future.

But the 2000s didn’t reward that nuance. The decade brought the “China Shock” to American metals. Chinese steel capacity surged and cheap commodity product poured into global markets. For ATI—still meaningfully exposed to standard stainless steel—the pressure showed up where it always does: margins. The stock traded like a proxy for nickel prices and steel demand, not like a company building world-class aerospace alloys.

The lesson of this era was brutal but simple: being a jack of all trades in metals meant being a master of none. ATI had priceless capabilities inside its walls—but from the outside, it looked like a commodity producer. And Wall Street valued it that way.

III. Inflection Point 1: The Ladish Acquisition & Vertical Integration (2011)

In the aerospace supply chain, there’s a crucial difference between companies that melt metal and companies that forge it into parts. Melting is where the metallurgy gets locked in: vacuum processes, tight chemistry control, and long, unforgiving production cycles that turn raw inputs into aerospace-grade titanium and superalloy. But forging is where the value concentrates. That’s the step where a generic-looking ingot becomes a disc, a ring, or a structural component that can actually go onto an aircraft.

ATI decided it didn’t want to stop at “we make great metal.” It wanted to be the company that delivered flight-critical parts.

So in 2010, ATI agreed to acquire Ladish for $778 million. The deal closed in 2011, and with it ATI bought its way into the forge.

ATI was explicit about the strategy: “ATI Ladish adds to our capability to produce highly engineered and technically complex parts. We offer customers, particularly in the aerospace market, an integrated, stable, and sustainable supply chain, which now includes advanced forging, casting, and machining assets for titanium alloys, nickel-based superalloys and specialty alloys.”

Ladish wasn’t a random bolt-on. It had been around since 1905, based in Cudahy, Wisconsin, and it had earned a reputation the old-fashioned way: by forging hard things well, and doing it reliably. It started with forged camshafts and heavy-duty components for automotive, farming, and construction equipment. Then aerospace arrived and changed the job description. Ladish moved from propeller forgings to high-temperature jet engine parts, and eventually into demanding applications like spacecraft components and deep-sea submersibles.

The crown jewel was isothermal forging. ATI Ladish became a leader in the technology and operated the industry’s largest isothermal forging press. In isothermal forging, the dies and the workpiece are kept at the same temperature, so the metal can be formed without cooling mid-process. That matters because the alloys you want in jet engines—high-strength, heat-resistant, often lightweight—don’t like being bullied. Isothermal forging lets you shape them precisely while preserving the properties that make them valuable in the first place.

And then there’s the kind of machinery that sounds like it belongs in a myth. The Cudahy plant houses the “85 Hammer,” a counterblow hammer installed in 1959. It weighs over a million pounds and sits like an iceberg—five stories above ground and five stories below. When it’s running, it can shape titanium and superalloys at temperatures above 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit into the rotating components that keep jet engines alive.

With Ladish, ATI added isothermal and closed-die forging for discs, rings, and structural parts—exactly the categories that increase content on next-generation engines and airframes. It expanded ring-rolling and forging throughput, opening the door to larger discs and hubs and pushing further into advanced alloy processes, including powder metallurgy approaches designed to cut lead times and reduce material waste.

On paper, the strategic logic was clean: move up the value chain. Don’t just sell metal by the pound—sell precision components that customers qualify, depend on, and keep buying for decades.

In practice, it was messy. ATI was trying to integrate a capital-intensive, high-spec forging operation while still dragging around a commodity stainless business that was bleeding cash. The company was serving two very different worlds at the same time, with two very different economics—and the tension showed.

Still, Ladish was a tell. It foreshadowed what ATI would eventually become: not just a supplier of specialty metals, but a critical, integrated partner to the aerospace primes and engine OEMs. Getting there, though, would require something far more dramatic than buying a forge. It would require ATI to shed the parts of itself that kept pulling it back into commodity gravity.

IV. The "Burning Platform": The Stainless Exit (2015 – 2020)

The mid-2010s were brutal for ATI. Global steel overcapacity squeezed margins across the industry, and the squeeze hit hardest where ATI was most exposed: commodity stainless. Worse, the company had poured billions into a state-of-the-art Hot Rolling and Processing Facility (HRPF) at Brackenridge, Pennsylvania. It was built to win on scale. In a world of collapsing stainless prices, it started to look less like a crown jewel and more like an anchor.

Then came the breaking point. In August 2015, ATI and the United Steelworkers collided in a labor lockout that didn’t just disrupt production—it hardened attitudes on both sides and changed the company’s trajectory.

ATI locked out about 2,200 workers on August 15, just ahead of a vote on what the company called its “last, best and final” offer. The lockout spread across ATI’s Flat-Rolled Products operations—12 locations across Massachusetts, Connecticut, New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Oregon—plants that made steel used in aerospace and defense, oil and gas, chemical processing, and power generation.

The union said the company came in swinging. In its telling, ATI ran “a well-prepared, well-funded campaign of intimidation and manipulation,” and put forward “a jaw-dropping list” of concessions—145 of them—demanding permanent changes that would raise retiree health care costs and create a two-tier system for benefits.

ATI, for its part, argued it was responding to real economic pressure. USW international vice president Tom Conway, the union’s lead negotiator, said management justified concessions by pointing to the steel downturn—prices in a sustained slump, with Chinese exports accused in multiple trade complaints of being sold below cost. Conway’s rebuttal cut to the heart of the dispute: the market might be cyclical, but ATI’s demands were permanent. “It’s undeniable there’s some pressure,” he told the Labor Press, “but the company has decided they’re going to use this as an opportunity to try and strip things out of the labor agreement that have been there for generations and that have nothing to do with the crisis.”

An ATI executive framed it even more starkly in the New York Times: “We’re faced with a once-in-a-generation opportunity to bend the cost curve on a major part of our costs. If we’re going to be competitive, we have to be in a position where we have a different benefit structure for the next generation we hire.”

Workers endured a brutal winter on picket lines. The lockout dragged on for seven months, finally ending March 14, 2016. Employees returned under a new four-year pact that the union ratified by a 5-to-1 margin. The settlement came shortly after the National Labor Relations Board said on Feb. 22 that ATI had not bargained in good faith and that the lockout was illegal.

It wasn’t the last labor rupture, either. In 2021, workers went on strike for three months. But 2015–2016 was the inflection point—the moment it became unmistakable that the old ATI, built around flat-rolled stainless and legacy cost structures, was heading for a cliff.

The strategic reset accelerated under Robert Wetherbee. He became CEO in 2018 and board chair in 2020, and under his leadership ATI pushed harder toward a simpler identity: aerospace and defense, and the high-performance materials and components those markets demand.

Then the pandemic hit—and it gave ATI both the crisis and the cover to make its most radical move.

In December 2020, with commercial aerospace reeling from the collapse in air travel, ATI announced it was exiting standard stainless sheet products, streamlining its footprint, and investing in enhanced capabilities to accelerate a high-value strategy primarily focused on aerospace and defense.

The numbers made the decision look insane at first glance, and inevitable at second. ATI said the stainless sheet line had generated $445 million of revenue in 2019—at margins of less than 1%. Nearly half a billion dollars in sales, producing almost no profit. This was the purest form of “shrinking to grow”: walking away from volume because the volume wasn’t worth having.

The exit had real-world consequences. ATI said it would close five finishing facilities in Ohio, California, Illinois, Pennsylvania, and Connecticut—two already closed, the remaining three slated to shut by the end of 2021.

And financially, the cleanup was ugly. ATI said fourth-quarter results would include about $1 billion of non-cash charges for long-lived asset impairments, predominantly tied to Brackenridge and the HRPF. The impairment didn’t affect compliance with credit covenants—but it made something clear: the company was finally admitting, on paper, what the market had been saying for years.

Wall Street didn’t know what to do with it. Cutting a major revenue stream in the middle of a pandemic sounded like desperation, not strategy. And ATI was coming off two years of annual losses, including a $1.6 billion hit in 2020.

But the logic was relentless. The revenue ATI kept was the only revenue that mattered. Aerospace and defense generated about half of ATI’s revenue in 2019, and the company set its sights on pushing that mix to 65% or more over time. That wasn’t a portfolio tweak. It was a declaration that the stainless era—the business that built the company’s name—was no longer the company’s future.

V. Inflection Point 2: The Geopolitical Moat (2022 – Present)

On February 24, 2022, Russian tanks rolled into Ukraine, and the global aerospace supply chain cracked open.

For years, the industry had built an uncomfortable dependency: Russia supplied a massive share of the titanium that ends up inside commercial aircraft. Boeing sourced roughly a third of its titanium from Russia. Airbus was closer to half. Embraer, by some estimates, relied on Russia for nearly all of it. And it wasn’t just airframes. Engine makers had exposure too—Safran around half, and Rolls-Royce about a fifth.

At the center of that web sat VSMPO-AVISMA, a state-connected Russian titan and the world’s largest titanium producer, with about a quarter of the global titanium market. More importantly, it held an outsized position in aerospace-grade structural titanium—at least half of what the global aerospace industry needed. There were only a few credible alternatives at that level: TIMET, ATI, and Howmet Aerospace in the U.S., plus a small handful of other qualified players worldwide. But in normal times, “qualified” doesn’t mean “available.” Aerospace metals capacity isn’t something you summon on demand.

Then the war made “normal times” irrelevant.

Boeing moved first, stopping purchases of Russian titanium in March 2022. Airbus followed more gradually. But the direction was obvious: the industry needed Western supply, fast.

“The situation in Ukraine has focused the industry on shifting aerospace titanium purchases to Western sources,” ATI CEO Robert Wetherbee said on an earnings call. “Customer discussions on the subject are pervasive, active and lively.” And crucially, suppliers like ATI and Howmet had room to absorb incremental demand—either by taking on new customers or by expanding share with existing ones.

This was ATI’s moment. A decade earlier, it had been fighting to escape the commodity trap. Now, it was one of the few Western companies positioned to fill a suddenly geopolitical hole in the world’s most demanding supply chain. “I think most of us who are in this position will qualify, and we will win some share,” Wetherbee said. “I do think the [aerospace] industry is repositioning itself, not 100%, but significantly.”

The realignment didn’t just benefit one company; it tilted the map. The United States—with ATI and Howmet—had strong primary and secondary titanium capabilities. Along with Japan, it was well-positioned to pick up business that could no longer comfortably sit with VSMPO.

And the pressure showed on the Russian side. Airbus was thought to have sourced around 60% of its titanium from VSMPO at one point, while Boeing’s reliance was estimated as high as 80%. Those shares were understood to have fallen after the invasion. VSMPO’s reported annual sponge production dropped from around 32,000 tonnes before the war to about 17,000 afterwards. Where exports were once believed to take the majority of output, much of it increasingly fed domestic demand.

ATI didn’t waste the moment to clarify what it had become.

In June 2022, the company made its transformation official in a way investors couldn’t miss: it dropped “Allegheny Technologies Incorporated” and became simply ATI. Its web domain shifted from ATImetals.com to ATImaterials.com—less steel mill, more materials science. And it moved its headquarters from Pittsburgh, the symbolic home of Allegheny Ludlum’s stainless legacy, to Dallas, Texas.

The rebrand was symbolism, but the market re-categorization was validation. In May 2025, ATI announced that effective May 1, 2025, its Global Industry Classification Standard (GICS) code would be reclassified to Aerospace and Defense. Previously, ATI had lived in the less flattering bucket of Metals and Mining.

That wasn’t just a new label. Aerospace and defense suppliers tend to earn higher valuations than commodity metals companies for a reason: they’re defined by specialized capability, long-term contracts, and barriers to entry that take years and billions to replicate. The reclassification effectively signaled that ATI belonged in a different conversation—and in front of a different set of investors—than the stainless producer it used to be.

VI. The Business Model: How "Melt-to-Fly" Works

Understanding ATI means understanding what a jet engine does to metal—and why so few companies can reliably make metal that survives it.

ATI puts it plainly: its materials help customers run jet engines at extreme temperatures, equip the U.S. defense industrial base, move highly corrosive liquids and exhaust streams safely, and enable advanced medical applications. But the clearest proof point is still the hot section of a turbofan.

When jet fuel ignites, the hottest parts of the engine push well beyond 2,500 degrees Fahrenheit. Turbine blades spin at thousands of revolutions per minute, and the forces on those parts are violent and constant. They have to hold their shape and strength not for minutes, but for thousands of operating hours. That’s not “good steel.” That’s materials science at the edge of what’s possible.

This is the world of ATI’s High Performance Materials & Components (HPMC) business: high-performance materials, components, and advanced metallic powders. The core ingredients are nickel-based alloys and superalloys, titanium and titanium-based alloys, and other specialty metals that exist for one reason—performance in environments where normal materials give up.

It starts with melting, and not the kind you picture from old steel documentaries. ATI runs sophisticated vacuum melting operations designed to strip out impurities and lock in chemistry with aerospace-level precision. At Richland, ATI uses an electron beam furnace to liquefy metal, then flows it into hearths where defects are removed before it’s formed into finished billets—some weighing up to 44,000 pounds. The plant also uses vacuum arc remelting, another step in producing the consistency and cleanliness aerospace customers demand.

None of this is fast. The rule of thumb in the industry is that it takes about nine months to go from raw inputs to a finished jet engine component. That long cycle ties up working capital, but it also creates something far more valuable: permanence. Once an alloy is specified into an engine program, swapping suppliers isn’t a purchasing decision—it’s a multi-year recertification ordeal.

That’s why ATI’s position can look less like a vendor relationship and more like an embedded dependency. ATI is a sole supplier for five out of seven critical alloys used in jet engine hot sections, with long-term contracts that run into the 2030s and 2040s. In this business, that kind of visibility is the prize.

The commercial mechanism that makes it all work is the Long Term Agreement, or LTA. These aren’t spot buys. They’re multi-year commitments that secure supply, lock in relationships, and effectively reserve capacity. ATI has built much of its aerospace and defense position around these long-term agreements, and that’s what gives the company the confidence to invest and plan like a partner, not a commodity producer.

In 2024, ATI signed new sales commitments totaling $4 billion, extending through 2040. A meaningful portion—about $2.2 billion—is scheduled to deliver by the end of this decade, largely tied to highly differentiated nickel alloys for jet engines.

There’s also a flywheel here. The hotter engine designers run their cores to squeeze out fuel efficiency, the more they need sophisticated superalloys—and the more they rely on the small club of suppliers that can actually make them at scale. ATI expanded its reach in that direction in 2009, when Crucible Compaction Metals and Crucible Research joined the company, bringing modern powder metal capabilities that support materials and components built to withstand even higher temperatures and stresses.

Today ATI runs two main segments: High Performance Materials & Components (HPMC) and Advanced Alloys & Solutions (AA&S). Together they serve aerospace and defense, medical, energy, and other industrial markets.

HPMC is the engine of the new ATI. In fiscal 2024, about 86% of HPMC revenue came from aerospace and defense. And within that, commercial aerospace has been the biggest driver of HPMC’s sales and EBITDA growth in recent years—one reason ATI believes it will continue to drive both HPMC’s performance and the company’s overall results going forward.

VII. Analysis: Powers & Forces

ATI is a textbook case of sustainable competitive advantage. But it’s not the kind you can understand by looking at market share charts alone. The moat is built out of qualification cycles, specialized equipment, and a supply chain that can’t be willed into existence when geopolitics shifts.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Framework:

Switching Costs (Primary Power): Once ATI’s material is “spec’d in” to a jet engine or airframe program, it’s effectively welded into the design. Aerospace materials aren’t interchangeable parts you can shop for every year. Getting an alloy approved can take years, and requalifying a new supplier can cost millions—plus risk schedule slips that ripple through the whole program. ATI has used technical depth, product innovation, and long-term supply agreements with OEMs like Boeing, Airbus, GE Aerospace, and Pratt & Whitney to embed itself where switching is painful. If a program like GE’s LEAP or Pratt & Whitney’s Geared Turbofan was qualified around a specific ATI material, changing that supplier means going back through a recertification process that no one wants unless they’re forced.

Cornered Resource: Titanium sponge and aerospace-grade melt capacity are real, physical bottlenecks. The last domestic U.S. sponge facility in Henderson, Nevada, closed in 2020. Globally, sponge production is concentrated—led by China, then Japan and Russia, with Kazakhstan and Ukraine also meaningful. Even if you had the money, you can’t just spin up new melt capacity on a short timeline; environmental permitting can take years, and the process knowledge is hard-earned.

Process Power: ATI’s advantage is also in how it makes what it makes. Isothermal forging, vacuum arc remelting, powder metallurgy—these aren’t buzzwords. They’re capabilities that take massive capital, obsessive quality systems, and decades of iteration to do reliably at aerospace standards. ATI is essentially a pure play on a “friend-shored” titanium and high-temperature alloy supply chain that feeds jets, engines, and defense. With its melting and mill capabilities—and a closed-loop scrap ecosystem—it can turn titanium into qualified billet, plate, and near-net shapes that can slot into demanding applications without customers taking on qualification risk.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis:

Threat of New Entrants: Extremely Low. The barriers are enormous: specialized facilities, deep metallurgical know-how, and certifications that take years to earn. ATI has made investments like its $325 million plant in Rowley, Utah, in 2012—and that’s the kind of spend that’s table stakes, not a finishing move.

Supplier Power: Mixed to High. The upstream is concentrated, especially in titanium sponge. That concentration creates both pricing and availability risk. ATI has tried to blunt that exposure through long-term supply agreements, including with Japanese sponge producers, and by tightening control over more of its own value chain.

Buyer Power: Shifting in ATI's Favor. Historically, the big airframers and engine makers had leverage because they were the ones placing the orders. The post-2022 titanium reshuffle changed that dynamic. When Russian supply becomes politically and operationally difficult, “just source elsewhere” stops being a simple procurement instruction. If you’re one of the few suppliers that can deliver qualified material at scale into a ramping aerospace market, buyer power shrinks.

Competitive Rivalry: This is a concentrated field with a small number of globally relevant players in aerospace titanium and high-performance alloys. VSMPO-AVISMA has been one of the dominant suppliers, alongside U.S. firms like TIMET and Howmet, plus ATI’s own position in titanium and nickel-based superalloys. Competition is real—but it’s competition among incumbents with capacity constraints, not a free-for-all.

Threat of Substitutes: Very Low. For the highest-temperature, highest-stress aerospace applications, there’s no easy materials swap. Carbon fiber can’t take hot-section temperatures. Aluminum doesn’t have the strength. Steel is too heavy. The constraints aren’t commercial—they’re physical.

Competition:

ATI’s closest peers tend to be Howmet Aerospace, TIMET (owned by Precision Castparts, a Berkshire Hathaway subsidiary), and Carpenter Technology. VSMPO has also long sat in the top tier of aerospace titanium supply, with an outsized share for a single producer.

Howmet is a useful comparison because it’s a heavyweight in aerospace components, and it benefits from the same jet-cycle tailwinds. As of May 9, 2025, Howmet Aerospace had a market capitalization of $63.5 billion. Its trailing 12-month revenue was $7.5 billion, with a 16.6% net profit margin, and its most recent year-over-year quarterly sales growth was 6.5%.

But the two companies aren’t the same animal. Howmet is larger and more diversified, with meaningful fastener and wheel businesses. ATI is narrower—and that’s the point. Its exposure is more concentrated in the materials science layer of the stack, which also gives it more direct leverage to the materials-specific opportunity created when Russian titanium becomes far harder for the West to rely on.

VIII. The Playbook: Lessons for Founders & Investors

ATI’s transformation isn’t just a metals story. It’s a playbook.

Addition by Subtraction: Sometimes the best way to create value is to fire your customers. ATI’s decision to exit standard stainless steel—walking away from $445 million in revenue at less than 1% margins—didn’t just shrink the top line. It freed capital and management attention for the part of the portfolio that could actually compound: high-margin aerospace materials and components. By pivoting away from commodity stainless toward HPMC, ATI reduced exposure to whiplash stainless pricing and built a business with far more stable earnings power.

The "China Plus One" Strategy: ATI is a case study in deglobalization. After the invasion of Ukraine exposed just how dependent Western OEMs were on Russian titanium, the priority shifted from “cheapest” to “secure and qualified.” Since 2022, the supply picture has stayed volatile as OEMs worked to reduce exposure to Russian sources and diversify toward U.S. and allied suppliers. In that environment, expanding a domestic-friendly titanium LTA isn’t just a procurement win—it reduces pricing and schedule risk for machining centers and fabricators that live downstream of programs tied to Boeing.

Focus on the "Hard" Problem: ATI stopped doing what was easy—rolling commodity steel—and doubled down on what was hard: materials science at the edge of physics. Add in quieter tailwinds like inventory restocking, additive manufacturing, and frontier tech, and ATI looks leveraged to both volume and value. It’s an advantaged node in a narrow supply chain, with operational know-how that’s hard to copy and switching costs that rise every time another part gets approved.

Patience in Capital Allocation: The bets ATI made in 2010–2011—like the Ladish forge and powder metallurgy capabilities—took a decade to fully show their value. And the company kept spending to widen that lead. In 2024, ATI invested $239 million in capital expenditures to grow capacity and capabilities. It has continued investing in facilities like the new Pageland, South Carolina titanium sheet plant, with payoffs expected in the 2025–2030 timeframe.

Leadership Matters: None of this happens without someone willing to make painful calls in a crisis. The Wetherbee transformation hinged on taking radical action when the pandemic created both a shock and an opening. “Bob truly transformed ATI, turning the challenge of a pandemic into an opportunity to create our purpose-built portfolio, accelerating our strategy of high performance and differentiation.”

The transition to new CEO Kimberly Fields signaled continuity, not a handbrake turn. Fields joined ATI in 2019 as executive vice president of the Flat Rolled Products group, and in 2020 she took on leadership of both business segments. Before ATI, she was group president for industrial and energy at IDEX Corporation, where she improved profitability and accelerated growth across the portfolio. Earlier roles spanned commercial, manufacturing, and strategic leadership positions at EVRAZ and GE, where she grew GE’s penetration in metals, petrochemicals, and mining. Fields earned a BS in Ceramic Engineering from the University of Illinois at Champaign-Urbana and an MBA from the Kellogg Graduate School of Management at Northwestern University.

“With Kim as CEO, ATI has grown as an aerospace and defense powerhouse,” Wetherbee said. “More than 70% of the company’s revenues now come from these core markets.”

IX. Bear vs. Bull & Future Outlook

The Bull Case:

Aerospace looks like it has entered a supercycle. The commercial market is expected to be worth about $1.3 trillion over the next decade, and Boeing and Airbus are sitting on backlogs that now top 10,000 aircraft. Fulfilling that queue isn’t just an assembly-line problem. It’s a materials problem—one that translates into enormous, steady demand for engine and airframe inputs for years.

Layer on defense. U.S. and allied budgets are expected to keep rising in the low single digits annually, with spending aimed at exactly the kinds of programs that chew through advanced alloys: hypersonics, fighters, and next-generation satellites.

ATI’s results have started to look like what you’d expect from a company on the right side of those trends. In the fourth quarter of 2024, ATI reported $1.17 billion in sales and $137.1 million in net income attributable to ATI (or $0.94 per share). For the full year, free cash flow was $248 million, up 50% versus the prior year. Adjusted EBITDA for 2024 was $729 million, up 15% from 2023—performance ATI expected to carry into 2025.

By the third quarter of 2025, the narrative had shifted from “turnaround” to “operating leverage.” ATI reported revenue up 7% year over year to more than $1.1 billion. Adjusted EPS came in at $0.85, beating the high end of ATI’s projected range by $0.10. Adjusted EBITDA was $225 million, with margin above 20%—nearly double what it was in 2019. HPMC ran at margins above 24%, and AA&S exceeded 17%.

Defense is adding real fuel. Defense revenue was up 51% year over year and 36% sequentially, reinforcing the idea that ATI isn’t just riding commercial aviation’s recovery.

Then there’s the real advantage: visibility. Long-term agreements are the mechanism that turns demand into durable planning. Management’s targets reflect that confidence: revenue above $5 billion and adjusted EBITDA of $1 billion by 2027, driven by more than $1 billion of organic growth and a roughly 60% increase in adjusted earnings from 2023 to 2027.

Recent wins back up the positioning. ATI extended and expanded its long-term titanium products agreement with Boeing, supporting Boeing’s full suite of commercial programs, with room to grow and the ability to serve Boeing’s third-party subsidiaries under the agreement. ATI also secured a multi-year agreement with Airbus to supply titanium plate, sheet, and billet—more than doubling ATI’s previous support level to Airbus.

The Bear Case:

Execution Risk: The opportunity is there, but ATI still has to deliver. Can it ramp production fast enough without creating bottlenecks or quality issues? Capacity constraints are real, and ATI’s 2025 capital spending guidance of $260–280 million is aimed at expanding production—but delays or missteps could crimp margins.

Supply Chain Dependencies: Titanium sponge remains a concentrated upstream market. U.S. producers source much of their sponge from Japan—principally Toho Titanium and Osaka Titanium Technologies. If Russian and Ukrainian supplies stay constrained and China isn’t a viable alternative, the question becomes whether the remaining suppliers can scale to meet incremental demand.

Customer Concentration: ATI is meaningfully tied to Boeing’s build rates. ATI’s 2025 guidance assumes no work stoppages, but ongoing union contract negotiations introduce risk. Any disruption to 737 MAX or 787 production flows straight through to ATI volumes.

Tariff Exposure: In its presentation, ATI flagged that 2025 tariffs could represent about $50 million per year of exposure before offsets. The company expected limited impact to full-year earnings guidance due to mitigations—but it’s still a variable to watch.

Labor Relations: Labor is never just “a line item” at ATI. The company has a history of contentious negotiations. ATI said employees ratified a new six-year labor agreement with the United Steelworkers, which reduces near-term risk—but the relationship carries historical baggage.

Key KPIs to Track:

For long-term investors watching whether the transformation keeps compounding, two metrics matter most:

-

Aerospace & Defense Revenue Percentage: This is the scoreboard for ATI’s strategy. It’s currently about 66–70% of total revenue, with a push toward 75%+ concentration in higher-margin A&D markets.

-

Adjusted EBITDA Margin: ATI is now running above 17% overall, with HPMC above 24%. Continued margin expansion is the clearest signal that the portfolio shift is still paying off, and management’s 2027 targets imply more improvement as scale builds.

Future Growth Vectors:

ATI is still investing to widen the gap. By late fiscal 2025, at full production, total titanium melt capacity is expected to be 80% greater than its fiscal-year baseline. The company continues developing new alloys for aerospace and defense, and several of its alloys have taken meaningful share in current and next-generation jet engines. Metallic powders are another lever, enabling alloy compositions and microstructures that improve performance, extend useful life in high-temperature environments, and support more efficient engines.

And beyond today’s jet cycle, the frontier markets line up neatly with ATI’s core competency. Hypersonics, space exploration programs like SpaceX and Blue Origin, and next-generation nuclear applications all demand high-temperature, high-strength materials. A company that can make metal survive the hot section of a modern engine is naturally positioned for the even harsher environments coming next.

X. Conclusion

From the smoky steel mills of Pittsburgh in 1901 to a corporate headquarters in Dallas, ATI’s story traces a very American arc: reinvention under pressure. What began as a company making basic metal products became a stainless steel pioneer, merged with a legendary conglomerate, and then spent years as a confusing hybrid—part kitchen-sink stainless, part jet-engine superalloys. It endured brutal labor conflict, commodity cycles, and the slow realization that you can’t build a great business by straddling two fundamentally different economics.

Then it chose. It walked away from volume that didn’t make money, doubled down on what it could do that almost no one else could, and emerged as a precision supplier to the most demanding supply chain on Earth: aerospace and defense.

Yes, the numbers reflect that shift. ATI reported full-year 2024 sales of $4.4 billion, its highest since 2012. But what matters more than the size is the substance. This revenue came from a fundamentally different ATI than the one that existed a decade earlier—one built around differentiated materials, long qualification cycles, and customer relationships measured in decades, not quarters.

“ATI is executing on a clear strategy and accelerating our leadership in aerospace and defense. By delivering the differentiated materials that enable our customers’ extraordinary performance, we’re driving sustainable growth and creating long-term value for our shareholders.”

In a world captivated by software and artificial intelligence, ATI is a reminder that progress still has a physical backbone. Code doesn’t fly. Metal does. When a Boeing 787 climbs to cruising altitude, when an F-35 goes supersonic, when a spacecraft survives re-entry, it’s not an app that makes it possible. It’s alloys that don’t crack, creep, or fail when everything is trying to tear them apart.

ATI’s transformation—from rusted steel giant to polished titanium jewel—took decades and demanded decisions most management teams would never make, especially in the middle of a crisis. The payoff is a company sitting in the rarest place in industry: where irreplaceable capability meets structural demand, and where “shrinking to grow” can turn into long-term compounding.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music