Adtalem Global Education: From DeVry's Rise to Healthcare Education Powerhouse

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

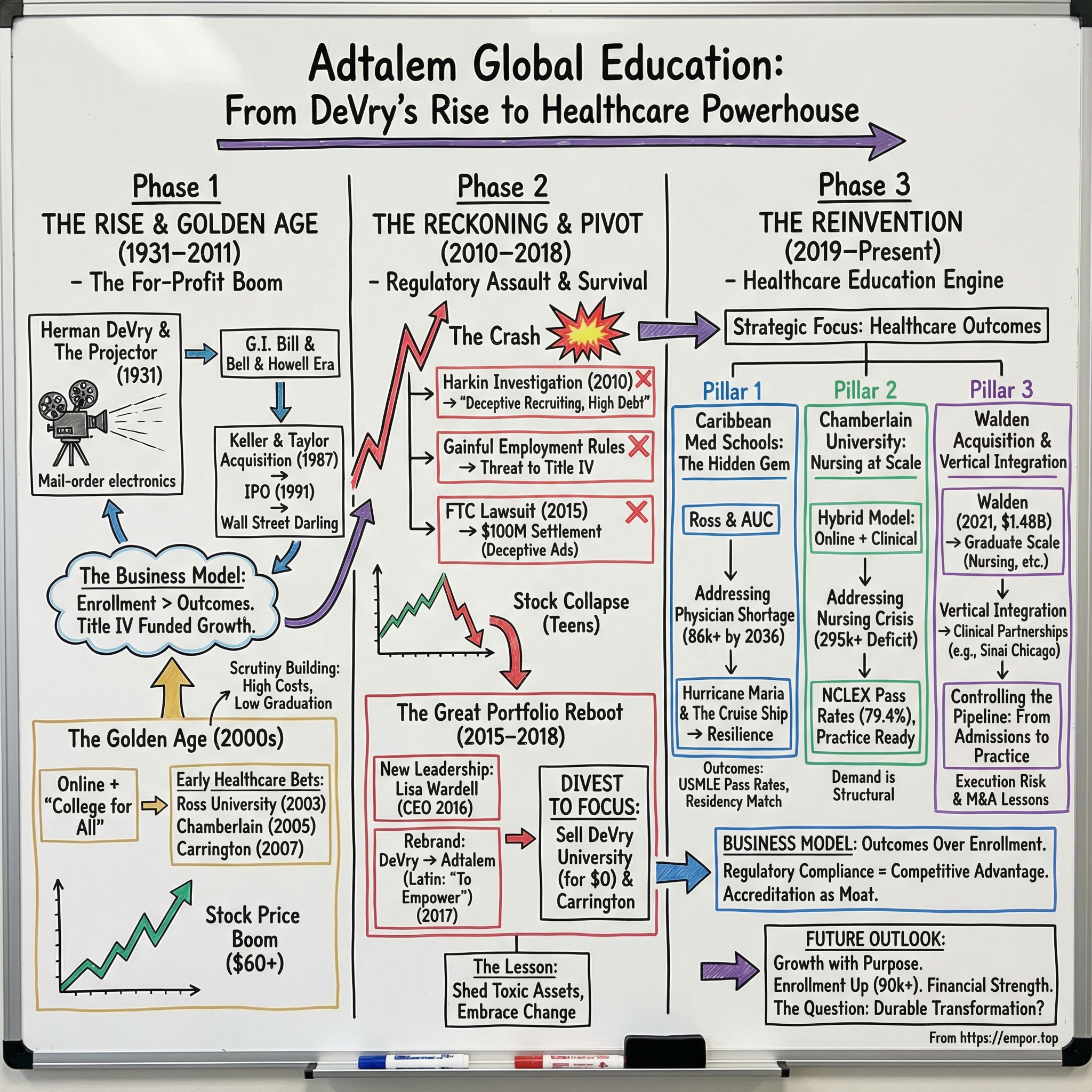

On a muggy Chicago evening in May 2017, Lisa Wardell stepped onto a stage at the company’s co-located Chamberlain and DeVry campus on North Campbell Avenue—ground that once belonged to Riverview Park—and did something that felt both ceremonial and surgical. She announced that DeVry Education Group would be known, from that moment on, as Adtalem Global Education.

Adtalem comes from Latin, meaning “to empower.” The name was picked from more than 5,000 submissions from employees around the world. But the point wasn’t the word. The point was the reset. This wasn’t a new logo slapped onto an old story. It was an attempt to cut loose from a brand that had become synonymous with everything people feared about for-profit education—and to convince students, regulators, and investors that the company had changed in substance, not just in spelling.

Here’s the twist: most people still haven’t heard of Adtalem. Yet in fiscal year 2024, it brought in $1,584.7 million in revenue, up 9.2% from the year before. In the most recent quarter, total enrollment reached 90,140 students, an 11.2% increase year over year. The stock has clawed its way back from the years when regulation and scandal nearly broke the business. And the company’s big bet—that healthcare education is a rare, durable growth opportunity—has looked smarter with each passing year.

So that’s our hook: how did a scandal-plagued for-profit college turn itself into a healthcare education operator that now trains nurses and doctors?

The answer runs through an era of political and regulatory punishment that nearly wiped DeVry off the map, a painful decision to sell the company’s namesake university, and a strategic pivot that required leadership to give up easy growth in exchange for something far harder to win: credibility.

This story matters because it sits right at the fault lines of American capitalism: the uneasy ethics of for-profit education, the way regulation can swing from tolerance to existential threat, and the question of whether a company can actually earn a second act. We’ll follow DeVry from its golden age as a Wall Street darling, through an extended reckoning, and into its reinvention as Adtalem—a company now staking its future on a healthcare system that can’t hire fast enough.

Along the way, there are lessons for everyone watching from the sidelines. When your core business becomes politically toxic, what do you do? When regulators come for your business model, how do you survive while peers collapse? And once you make it through, how do you prove—to skeptics who have every reason to doubt you—that the change is real?

II. The For-Profit Education Gold Rush (1931–2000s)

Herman Adolf DeVry was born in Mecklenburg-Schwerin, Germany, in 1876. When he was still a kid, his father, Wilhelm Heinrich DeVry, moved the family to the United States in 1886. They landed in New York City in that in-between moment of American history—before Ellis Island, right as the Statue of Liberty was about to go up—alongside countless other immigrant families trying to start over fast and blend in faster.

Herman grew up with the kind of restless, tinkerer’s ambition that doesn’t stay contained for long. In 1912, he built what was essentially a breakthrough in portability: a “Theater in a Suitcase,” the Model E projector. A year later he founded the DeVry Corporation, and the product took off. Thousands upon thousands of projectors ended up in schools across the country, making DeVry a quiet force in early education technology. And in 1921, that same portable projector even powered the first in-flight movie.

But Herman wasn’t content being a hardware guy. In 1931, in Chicago, he helped launch what would become DeVry—then called the De Forest Training School, named after his friend Lee de Forest, the vacuum tube pioneer. It started as a mail-order program teaching electronics repair. Over time it expanded into other practical, job-tied disciplines, including computers and accounting. The timing mattered. In the depths of the Great Depression, “learn a skill that gets you hired” wasn’t a slogan—it was survival.

After World War II, the flywheel spun faster. During the war, the school trained Army Air Corps instructors on electronic devices. Soon after, it became one of the first schools approved under the G.I. Bill. And that’s the early glimpse of the dynamic that would define for-profit education for decades: government funding flowing through students to schools, at massive scale, with enormous economic consequences.

Then came corporate ownership—and real expansion. In 1967, Bell & Howell acquired DeVry Technical Institute. Bell & Howell was famous for film and camera technology, but it saw DeVry as something else: a scalable education platform. Through the 1970s, it pushed a standardized, technology-focused curriculum aimed at the growing engineering and computer job market. By the early 1980s, DeVry had become national, enrolling tens of thousands of students.

The next big leap didn’t come from a conglomerate. It came from inside the classroom.

Two DeVry teachers, Dennis Keller and Ronald Taylor, understood the business from the ground level and saw a gap: graduate business education for working adults. In 1973, they founded the Keller Graduate School of Management, financed with $150,000 in loans from friends and family. It started as a daytime certificate program. By 1976, it had evolved into an evening MBA program built for people who already had jobs and responsibilities—and needed school to fit around their lives, not the other way around.

Accreditation followed, and it mattered. Keller was accredited by the North Central Association of Colleges and Schools in 1977, becoming the first for-profit school to win that recognition from the body. DeVry received full accreditation in 1981.

Then, in 1987, the tables turned. Keller acquired DeVry from Bell & Howell in a leveraged buyout worth $147.4 million. The combined company became DeVry Inc., with Keller as chairman and CEO and Taylor as president and COO.

And in 1991, DeVry went public. It wasn’t just a corporate milestone—it was a signal flare. For-profit education wasn’t merely a collection of trade schools anymore. It was now an investable category.

Underneath all of this was a business model that, in hindsight, feels almost inevitable. Recruit working adults who want better jobs. Offer flexible schedules and career-oriented curricula. And fund it all through federal student aid. Title IV—Pell Grants and student loans—didn’t just help students pay. It reshaped demand. Students could borrow even if they didn’t have cash, schools got paid upfront, and the repayment risk lived largely with the student and the government.

The incentives were powerful and obvious: enroll more students, collect more tuition, scale faster.

To investors, it looked like a dream: cohort-based revenue that could be forecast, relatively light infrastructure compared to traditional universities, and a massive federal subsidy pipeline pushing demand forward. Wrapped in the language of access and opportunity, the sector started to look less like education and more like a new kind of financial engine.

Wall Street took notice.

III. The Golden Age: Building the DeVry Empire (2000–2011)

If the 1990s made for-profit education investable, the 2000s made it explosive.

Three forces hit at once. Online delivery knocked down geography. The “college for all” narrative became cultural common sense. And federal student aid kept flowing with relatively light oversight. DeVry didn’t just benefit from that environment—it leaned into it.

The first big move of the era came in 2003, when DeVry acquired Ross University, a medical and veterinary school in the Caribbean, for a price reported between $310 million and $329 million. At the time, it looked like a bold adjacency: a technical-and-business education company buying a medical school. In hindsight, it was the opening bet on the one category that would eventually save the whole enterprise.

Ross also introduced DeVry to a distinctly Caribbean medical school model. Ross was founded in 1978 by Robert Ross to serve students—primarily from the U.S. and Canada—who couldn’t secure a spot at a domestic medical school. Students would complete coursework at Caribbean campuses, then return to the United States for clinical rotations and, if all went well, residency. It existed because the U.S. didn’t have enough medical school capacity for the people who wanted to become doctors—and that capacity constraint created demand that schools like Ross could tap.

Two years later, DeVry pushed deeper into healthcare—this time with nursing. In March 2005, it acquired Deaconess College of Nursing in St. Louis for about $5.3 million. Deaconess, founded back in 1889, was later renamed Chamberlain College of Nursing. The price tag was small, but the strategic significance wasn’t: nursing is a licensed profession with clear outcomes, steady demand, and employer pull. DeVry was starting to build a healthcare platform almost by accident.

In 2007, it broadened that platform again with the acquisition of Carrington College and Carrington College California, which offered certificates and degrees in a range of allied health fields. Then in 2011, DeVry added another medical school to the portfolio with the acquisition of the American University of the Caribbean School of Medicine.

Put together, these deals began to reshape what DeVry was. The company still relied heavily on DeVry University’s technology and business degrees, but healthcare was becoming an increasingly meaningful second engine—one with programs that were easier to defend on outcomes, and often carried better economics.

By the late 2000s, the market loved the story. DeVry’s growth—and its stock—reflected real investor enthusiasm. A big part of the pitch was simple and powerful: get a DeVry credential, and you can land the job you’re training for. Combine that promise with flexible schedules and payment plans, and steady enrollment growth didn’t look surprising. It looked inevitable.

But the scrutiny was building in the background.

DeVry had detractors inside education who questioned instructor quality and academic rigor. Critics pointed out that many instructors did not hold PhDs in their fields compared with traditional universities, and that instructors were often hired part-time—both to control costs and because many had jobs outside teaching. The tradeoff, critics argued, was less access to faculty and fewer opportunities for one-on-one support.

And underneath all the debate about faculty credentials was the larger issue that would define the next chapter: the tension inside the business model itself. When growth is powered by enrollment, when recruiting is rewarded more than completion, and when federal aid functions like a vast pool of prepaid tuition, the pressure to optimize for starts over outcomes is constant.

The warning lights were there. In the middle of a boom, though, few people were incentivized to stare at the dashboard.

IV. The Reckoning: Obama Era & Regulatory Assault (2010–2016)

The first tremors didn’t come from competitors. They came from Capitol Hill.

In 2010, Senator Tom Harkin of Iowa, the chair of the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee, launched a sweeping investigation into the for-profit college industry. When the committee’s findings landed, they weren’t subtle—and DeVry was right in the blast radius.

Harkin’s report painted a picture of an industry that charged far more than public alternatives while delivering shaky outcomes. In DeVry’s case, the report highlighted tuition for an associate’s degree that it said was many times higher than community colleges, and dropout rates it said were roughly half of students overall—higher for online students—often within just a few months. The report also pointed to relatively low spending per student on instruction, high executive compensation, and evidence the committee described as deceptive recruiting.

The committee’s numbers were stark: it found that more than half of DeVry students who enrolled in the 2008–2009 period had withdrawn by mid-2010. And by 2015, DeVry was reported to be spending more on marketing than on instruction. That contrast—pitch versus product—became a recurring theme of the era.

At the same time, the Obama administration’s Department of Education was building a policy weapon specifically aimed at the industry’s core incentive structure: the “Gainful Employment” rules. The idea was simple and brutal. If a program routinely left graduates with debt they couldn’t reasonably repay, that program shouldn’t be eligible for federal student aid. For schools whose revenue engine was Title IV, this wasn’t a compliance annoyance. It was a direct threat to the business model.

Then came the investigation that made the crisis concrete for everyday consumers: the FTC.

In January 2015, the Federal Trade Commission sued DeVry in federal court in Los Angeles, alleging deceptive advertising on two headline claims. The first was DeVry’s assertion that 90% of graduates who were actively seeking employment got jobs in their field within six months of graduation. The second was that DeVry graduates earned 15% more, one year after graduation on average, than graduates of all other colleges or universities.

The FTC alleged those claims were misleading in part because DeVry counted a significant number of graduates who already had jobs before enrolling.

In December 2016, DeVry University and its parent agreed to a $100 million settlement. The settlement required $49.4 million in cash to be distributed to qualifying students, plus $50.6 million in debt relief. That debt relief included the full balance on private student loans DeVry had issued to undergraduates between September 2008 and September 2015, along with additional student debts for items such as tuition, books, and lab fees. It was one of the largest FTC settlements ever in a false advertising case—and it landed as a public verdict on the company’s most important promise.

Wall Street reacted accordingly. DeVry’s stock, once above $60, fell into the teens. The company that helped make for-profit education a public-market growth story was suddenly trading like a business with an expiration date.

And it wasn’t alone. Across the industry, big names were collapsing under investigations and regulatory pressure. Corinthian Colleges imploded. ITT Technical Institute shut down. “For-profit” stopped being a business category and became a political slur—shorthand for predatory lending, deceptive marketing, and students left holding the bag.

DeVry also faced heat from the states. By 2013, it was under investigation by the attorneys general of Illinois and Massachusetts, and lawsuits alleged deceptive recruiting practices.

By the end of 2016, the question wasn’t whether DeVry could keep growing.

It was whether DeVry could survive at all—and what it would have to become in order to do it.

V. The Great Portfolio Reboot (2015–2018)

DeVry’s response to the crisis came in two moves that were easy to see from the outside—a new name and a new CEO—but those were really just the packaging for something much more drastic.

The real plan was a new thesis. And it came with a price: the company would have to be willing to sacrifice the institution that made it famous.

In early 2017, DeVry Education Group told shareholders, via an SEC filing, that it wanted to change the corporate name to Adtalem Global Education Inc., with a vote scheduled ahead of a May 22 shareholder meeting at its headquarters. The filing framed the change as a reflection of a company that had evolved—and as a way to create a more flexible platform as it diversified.

The name was described as Latin for “to empower.” It was also, famously, controversial. BuzzFeed News ran the name past two Harvard Latin professors, and the verdict was not flattering. One said it read like something close to gibberish. But the linguistic debate missed what the company was actually trying to do. This wasn’t about perfect Latin. It was about distance—conceptual and reputational—from the DeVry name, which by then had become a shorthand for the for-profit sector’s worst headlines.

The leadership shift mattered just as much. Lisa Wardell had become president and CEO in 2016, after years on the board. Her résumé didn’t look like the typical education executive’s. She had worked in private equity and venture investing, and she’d been an attorney in the commercial wireless division of the Federal Communications Commission. In other words, she understood capital allocation, operating turnarounds, and regulation—the three things DeVry needed most.

Wardell later became chairman of the board in 2019, and by that point she was also a notable outlier in corporate America: the only African American woman serving as both chairman and CEO in the S&P 400 Index.

But titles and rebrands don’t fix a business model. The portfolio had to change.

The clearest signal arrived in December 2017: Adtalem agreed to transfer DeVry University, along with Keller Graduate School of Management, to Cogswell Education LLC. DeVry and Keller together enrolled nearly 30,000 students at the time. Cogswell, by contrast, owned a much smaller California-based for-profit institution—Cogswell College—with about 600 students.

And here’s the part that tells you how far the pendulum had swung: no money changed hands at closing. The deal structure allowed Cogswell to potentially pay up to $20 million, but the headline was unmistakable. DeVry—the asset that built the company—had become so radioactive, and so operationally challenged, that getting it off the balance sheet mattered more than getting paid for it.

Industry watchers weren’t shocked. Tyton Partners managing director Trace Urdan, a longtime analyst of the sector, called it a break-even, declining asset and said selling for zero wasn’t surprising. BMO Capital Markets analyst Jeff Silber put it even more bluntly: DeVry and Keller were “a distressed asset,” while much of the rest of the portfolio was performing well.

Wardell’s public rationale was focus. With DeVry gone, she said, Adtalem would have more ability to concentrate on its remaining institutions across three verticals: medical and health care, technology and business, and professional education.

The divestitures kept coming. In 2018, Adtalem sold Carrington College to San Joaquin Valley College. In 2019, Kaplan, Inc. acquired Becker’s healthcare test preparation assets.

The strategy was finally snapping into focus: exit the businesses that carried the most scrutiny and the least defensible outcomes, and concentrate on healthcare education—where results could be measured, argued, and ultimately trusted.

VI. Caribbean Medical Schools: The Hidden Gem

To understand Adtalem’s transformation, you have to understand a weird, almost counterintuitive feature of American medical education: even as the country worries about not having enough doctors, it still tightly constrains the number of medical school seats.

The Association of American Medical Colleges put real stakes behind that in its March 2024 projection: by 2036, the U.S. could be short as many as 86,000 physicians. The same report makes the underlying point even clearer—demand is expected to keep outpacing supply in the most likely scenarios.

And it’s not an abstract future problem. The federal government already labels thousands of places as Health Professional Shortage Areas for primary care—communities where tens of millions of people live with limited access to basic, non-specialty care. The AAMC has also argued that if underserved populations used healthcare at the same rate as people with fewer barriers, the U.S. would need hundreds of thousands more physicians just to meet today’s demand.

That mismatch creates a bottleneck—and Adtalem sits right at it.

Every year, roughly 20,000 prospective medical students don’t get accepted. Not because they don’t want it badly enough, but because there simply aren’t enough MD seats. In 2020, nearly 1,000 graduates of Adtalem’s medical schools entered residencies in the U.S. healthcare system. That’s the company’s core value proposition in one sentence: it helps move students through a constricted pipeline into the American physician workforce.

This is the opening Caribbean medical schools have exploited for decades. The model is simple: students who can handle the coursework, and often have decent MCAT scores, but can’t win a domestic acceptance, go offshore for the pre-clinical portion of their training—then come back to the U.S. for clinical rotations and, if they clear all the hurdles, the residency match.

Adtalem’s two flagship assets here are Ross University School of Medicine and the American University of the Caribbean School of Medicine. Ross, specifically, is a private, for-profit medical school owned by Adtalem. Today its main campus is in Barbados, with administrative offices in Miramar, Florida. Until 2019, its main campus was in Portsmouth, Dominica.

The economics are as straightforward as the debate is heated: tuition can be high, admissions standards are generally lower than U.S. medical schools, and the prize is real—a shot at becoming a practicing physician. Critics argue the model can turn into a debt trap for students who don’t make it through. Defenders point to the thousands of doctors who did.

Then, in September 2017, the entire model got stress-tested by something no regulator, investor, or brochure ever prepares you for: Hurricane Maria.

Maria hit Dominica as a Category 5 storm and tore through the island’s infrastructure. Communications went down. Ross was effectively cut off. Students and faculty were evacuated to the U.S. mainland.

For the people on the ground, it was terrifyingly personal. Medical student Nick Cooper, a 26-year-old from Atlanta, described sheltering behind a single bathroom door as the storm raged: “We knew this bathroom would either be our savior, or become our tomb.”

And then came one of the stranger pivots you’ll ever hear in higher education: Adtalem turned to a cruise ship. Classes resumed on what was described as a “uniquely fitted cruise liner” docked near St. Kitts, where about 1,050 Ross students temporarily lived and studied.

But the cruise ship wasn’t the end of the story. Ross had operated in Dominica since 1978 and had become a major part of the island’s economy—reported at one point as producing around 30% of Dominica’s gross domestic product. Still, the damage and disruption were so severe that the school ultimately decided to leave. In 2018, Ross announced it would relocate operations to Barbados, a move widely seen as a major blow to Dominica’s “Nature Island.”

By August 2018, Ross University School of Medicine was operating in Bridgetown, Barbados. The school’s administrative footprint also included bases in Iselin, New Jersey and Miramar, Florida.

From a business perspective, Hurricane Maria was an operational nightmare: evacuate more than a thousand students from an island in crisis, keep instruction going—on a ship, of all places—and then relocate an entire medical campus to a new country. That Adtalem pulled it off while maintaining accreditation and continuity isn’t just a dramatic anecdote. It’s a glimpse of the underlying capability that would become critical in the company’s second act.

VII. Chamberlain University: Nursing at Scale

If the Caribbean medical schools are Adtalem’s hidden gem, Chamberlain is its scale engine. And the demand it’s built for isn’t hypothetical. The nursing shortage in America is already here, and the forces driving it have been building for years.

Start with the simplest constraint: there aren’t enough seats to train the nurses the system needs. The American Association of Colleges of Nursing says U.S. nursing schools turned away more than 65,000 qualified applicants in 2023. The reasons weren’t a lack of interest or ability—it was capacity, including a shortage of faculty. That same year, the AACN pointed to nearly 2,000 full-time nursing faculty vacancies.

Then stack on demographics. A meaningful share of the nursing workforce is nearing retirement, and the American Nurses Association projects that more than 500,000 experienced RNs will retire by the end of 2025. Replacing that kind of institutional knowledge and sheer headcount isn’t something you fix with a single graduating class.

And the numbers have been pointing in the same direction across the board. McKinsey projected in 2022 that the U.S. could be short hundreds of thousands of registered nurses for direct patient care by 2025. The Department of Health and Human Services later captured the same story in a different way: between 2022 and 2025, RN supply rose about 1% while demand rose about 3%, leaving an estimated nationwide deficit of roughly 295,800 nurses.

This is the backdrop for why Chamberlain matters so much to Adtalem’s strategy. Chamberlain is designed to absorb demand at scale, without pretending nursing can be taught entirely through a screen. The model blends online flexibility with in-person clinical training—the hybrid approach that lets the school reach more students while still meeting the hands-on requirements nursing licensure demands.

Adtalem has kept expanding the footprint to chase that demand. It announced plans to enter the Kansas City market with a 24th Chamberlain location designed to accommodate around 550 students—positioned explicitly as a response to provider shortages.

Outcomes are the currency in nursing, and Chamberlain leans into that. In 2024, the school reported a 79.40% national average first-time pass rate on the NCLEX for its BSN program. That same year, Chamberlain reported an 88% first-time pass rate on the PMHNP certification exam—above the national averages reported by ANCC and AANPCB.

Chamberlain also pitches breadth alongside scale. Its BSN curriculum includes a Global Health Education Program, giving students opportunities to serve communities in places such as Brazil, India, and Kenya. And at the campus level, the throughput is real: Chamberlain’s Atlanta campus graduates about 275 BSN students each year.

The company has also pushed to make its training feel closer to the realities of the job on day one. Chamberlain expanded its Practice Ready. Specialty Focused.™ model through a partnership with the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses, adding an offering built around caring for acutely and critically ill patients and their families. It sits alongside other PRSF specializations, including emergency nursing, nephrology, home healthcare, and perioperative nursing.

For investors—and for regulators still skeptical from the DeVry era—nursing has a fundamentally different profile than generic undergraduate education. The outcomes are measurable. The job is licensed. Employment is clearly “in-field.” And the demand curve is structural. When critics attacked for-profit education’s value proposition, they were often pointing at business or technology programs where the credential didn’t reliably translate into economic mobility. Nursing is different. The credential is the job.

VIII. The Walden Acquisition & Divestiture (2021–2024)

By 2020, Adtalem had done the hard part of its reboot: cut away the DeVry legacy and bet the company on healthcare. Now it faced a different temptation—the classic post-turnaround question: how do you grow without drifting back into the old playbook?

In September 2020, Adtalem announced its biggest acquisition ever: a definitive agreement to buy Walden University from Laureate Education for $1.48 billion in cash. Walden was one of the largest online universities in the country by enrollment, and unlike DeVry’s old bread-and-butter undergraduate mix, most of Walden’s students were in graduate programs. Only about 7,000 were undergrads. Roughly a third were in nursing, with big clusters in education, management, and social work.

Management sold the deal as an extension of the healthcare thesis—more scale, more programs, more reach. In Adtalem’s announcement, the company pointed to projected shortages of registered nurses and physicians in the coming decade as the backdrop. Lisa Wardell called it “a pivotal step,” framing Adtalem not just as an education company, but as a “workforce solutions provider” with a bigger platform to meet healthcare demand.

The acquisition closed in August 2021 after the required regulatory approvals came through. Around the same time, the company also prepared a leadership handoff. Adtalem announced that Stephen Beard, then chief operating officer, would succeed Wardell as CEO and join the board effective September 8. Wardell, who had been both chairman and CEO, would move into the role of executive chairman for a one-year term. Beard had joined Adtalem in 2018 as senior vice president, general counsel, and corporate secretary, then moved into roles with broader operating scope, including COO in 2019. He was later named CEO in 2021 and elected chairman in 2024.

On paper, the sequence made sense: new CEO, new asset, a fresh chapter. In practice, Walden was harder than the press release.

Integrating a massive online university isn’t like tucking in a small campus. After Adtalem bought Walden, student headcount fell sharply. Enrollment declined year over year, quarter after quarter, following the 2021 purchase. The message from leadership was that turning that trajectory required both investment and restraint. As Beard put it on an analyst call, “To invest at scale in new innovative student learning tools, expand existing programs and create new programs for in-demand professions requires disciplined cost management.”

More recently, Walden showed signs of stabilization. Total student enrollment increased 12.2% compared with the prior year, driven by growth in healthcare and non-healthcare programs. Still, whether Walden ultimately justified its $1.48 billion price tag remained an open question for investors.

What Walden really did, though, was teach a brutally clear lesson: in a regulated industry like education, M&A risk isn’t just about systems and org charts. It’s approvals, accreditation, faculty alignment, and student retention—variables that compound each other and can turn “strategic fit” into a multi-year operational grind. Even for an operator that had already survived a near-death regulatory experience, this was a reminder: scale doesn’t automatically mean strength.

IX. Medical School Expansion & Vertical Integration (2020–Present)

By the early 2020s, Adtalem’s strategy started to stretch beyond “own a couple of Caribbean med schools” and “scale nursing.” Management began describing something more ambitious: a vertically integrated healthcare workforce company—one that doesn’t just teach, but helps shepherd students from admission all the way through the clinical experiences that determine whether they actually become clinicians.

On Adtalem’s October 2024 earnings call, CEO Stephen Beard pointed to a medical residency partnership with Sinai Chicago, a safety-net health system. He said that more than 1,000 students from Ross and AUC had participated in clinical rotations or residency programs through that relationship—experience that, in his framing, strengthens their readiness and their commitment to addressing healthcare inequities.

Beard also argued that Adtalem’s decision to lean into healthcare education—made before COVID—looked even clearer on the other side of the pandemic. “The pandemic really laid bare the fragility of our health care system,” he said. Adtalem, he added, is “animated with the idea of changing health care by producing clinicians at scale that are day-one ready.”

That mission has shown up in the company’s growth metrics. By the end of September 2024, total enrollment was up about 11% year over year to roughly 90,000 students—continuing a run of quarterly growth after the COVID-era declines. The student mix reflects the portfolio Adtalem has chosen to keep and build: medical students at Ross University School of Medicine and the American University of the Caribbean School of Medicine; nursing and behavioral health students at Chamberlain University and the largely online Walden University; and veterinary students at Ross University School of Veterinary Medicine.

The company has also been pushing its footprint and partnerships in the places where it operates. In Barbados, Adtalem signed a Memorandum of Understanding that would allow 30 registered Barbadian nurses the opportunity to pursue Chamberlain’s Nurse Practitioner program.

The vertical integration thesis is easy to understand in plain terms: in healthcare education, the bottleneck isn’t only classroom instruction. It’s clinical placement and real-world training capacity. If Adtalem can help control that pipeline—by partnering with health systems that can offer rotations, residencies, and jobs—it can optimize for outcomes, not just enrollment. And it creates a tighter alignment: healthcare systems need a steady talent pipeline, and Adtalem needs clinical sites. Done well, each side becomes more committed to the other—and the whole machine gets harder for competitors to replicate.

X. Business Model Deep Dive & Unit Economics

Adtalem’s business, at its core, is still tuition. The difference is what sits underneath that tuition now.

For U.S. students, most of the money ultimately flows through the federal Title IV system—Pell Grants and student loans—just as it did in the DeVry era. For international students, especially in the Caribbean medical programs, tuition is more often paid directly or financed through private lending. Same broad mechanism as before: students pay tuition, the company delivers education. But the product mix has changed, and so has the level of scrutiny attached to whether that education actually leads somewhere real.

By fiscal year 2024, Adtalem generated $1,584.7 million in revenue, up 9.2% from the year before. Profitability improved too: operating income rose to $217.1 million from $168.2 million, and adjusted operating income increased to $308.8 million from $287.6 million. Net income came in at $136.8 million versus $93.4 million the prior year, with adjusted net income of $201.8 million. Adjusted EBITDA was $377.5 million, up from $343.4 million, with an adjusted EBITDA margin of 23.8%.

Management’s tone also shifted from survival to confidence. Adtalem raised its guidance for fiscal year 2025, projecting revenue between $1,690 million and $1,730 million—about 6.5% to 9.0% growth year over year—and adjusted earnings per share of $5.75 to $5.95, which it framed as roughly 14.5% to 18.5% growth.

Operationally, the company reports three segments now: Chamberlain, Walden, and Medical and Veterinary. That structure tells you what Adtalem believes it is: a nursing scale engine, a big online graduate platform, and a set of medical and veterinary schools that feed directly into licensed professions.

Capital allocation has been about tightening the ship while returning cash to shareholders. The company emphasized debt reduction and share repurchases, including completing a $300 million share repurchase program that had been authorized in February 2022. It also repaid $50 million of its Term Loan B and repriced the remaining balance, reducing the interest rate by 50 basis points. During fiscal year 2024, it repurchased 5.446 million shares for approximately $261 million. In May 2025, that repurchase effort was completed, and a new buyback program of up to $150 million through May 2028 was launched.

But the more important shift isn’t a line item. It’s what the company’s incentives point to.

What separates Adtalem’s model from legacy DeVry is that the outcomes are harder to fake and easier to verify. In nursing and medicine, licensure exam performance—NCLEX for nurses, USMLE for physicians—functions as both marketing proof and a gatekeeper for accreditation and employability. If students don’t pass, the institution doesn’t just look bad. It loses credibility with regulators, clinical partners, and the employers who ultimately decide whether graduates get hired.

That pressure creates a very different kind of for-profit education business: one where long-term performance can matter as much as short-term enrollment, because the product has an external scoreboard—and the company can’t afford to ignore it.

XI. Regulatory Landscape & ESG Positioning

For-profit education is still politically radioactive. The Biden administration revived Gainful Employment rules, and borrower defense claims continued to hang over the sector—especially for companies with any historical baggage. Adtalem’s answer has been to pitch itself as the “good for-profit”: a company that absorbed the lessons of the last decade, tightened up its practices, and can point to outcomes that are harder to argue with.

The company’s own framing is that scale plus mission is the point. With more than 80,000 students and 300,000 alumni, Adtalem argues it can help relieve critical healthcare provider shortages—and that its enterprise-wide emphasis on advancing health equity matters more now than ever.

That positioning didn’t start with the Adtalem name. Even before the rebrand, the company looked for ways to separate itself from the broader for-profit category as scrutiny intensified and headlines got uglier. One example: Adtalem announced self-imposed reforms, including voluntarily limiting how much of its revenue could come from federal student aid—an explicit attempt to show regulators and the public that it wasn’t trying to max out the old incentives.

Wardell also reshaped the company’s leadership image in ways that were both substantive and symbolic. Under her leadership, Adtalem increased diversity in the boardroom and executive ranks: the board reached 67 percent diversity across gender and ethnicity combined, and the leadership team reached 80 percent by the same measure. Over her tenure, Adtalem’s stock rose by roughly 250 percent.

And then there’s the quiet superpower behind all of this: accreditation. It’s the closest thing education has to a moat. Keller was accredited by the North Central Association of Colleges and Schools in 1977, becoming the first for-profit school to receive that recognition from the body. That kind of regional accreditation isn’t just a seal on a website. It’s what preserves access to Title IV funds—the financial oxygen for most U.S. higher-ed models—and it’s a multi-year barrier that keeps would-be entrants from spinning up credible competitors overnight.

XII. Competitive Landscape & Market Positioning

Adtalem fights on a crowded battlefield. It’s up against traditional universities that have gotten serious about online and hybrid programs. It competes with other for-profit healthcare educators, including Grand Canyon University. And it runs into a different kind of rival entirely: hospital-based nursing programs that train their own talent in-house, often tied directly to employment.

What makes that competition tricky is that Adtalem isn’t a single school with a single identity. It’s a portfolio. Across its institutions, it operates 26 campuses in 15 states and four countries, with about 6,100 faculty members and more than 90,000 students. About 34% of those students are Black.

That last detail matters because it cuts both ways. In the post-DeVry world, when a company serves a large share of underrepresented students, accusations of exploitation carry more political force. But the counter-argument does, too: Adtalem can credibly say it’s expanding access in a system where traditional universities have limited capacity, limited flexibility, and plenty of their own barriers to entry.

Zoom in by segment and the rival set changes. In Caribbean medical education, Adtalem’s schools go head-to-head with institutions like American University of Antigua and St. George’s University. In nursing, the competitive set is even broader: state universities, private nonprofits, community college pipelines, and other for-profit operators all chasing the same applicants and the same clinical placements.

That fragmentation is also the opportunity. In markets where no single player dominates, advantage tends to accrue to the operator that can prove outcomes, build durable clinical networks, and reliably move students from enrollment to licensure to employment.

And the macro backdrop keeps reinforcing why this fight is worth having. The Association of American Medical Colleges has pushed for a multipronged response to the physician shortage: more federal support for residency training, smarter care delivery through technology, and better utilization of the full care team.

But even with those levers, the demand driver looks structural, not cyclical. The U.S. population aged 65 and older is projected to grow sharply, which pulls more demand into high-need physician specialties. At the same time, a large share of practicing physicians is nearing traditional retirement age—making it likely that more than a third of today’s physician workforce will retire within the next decade.

XIII. Strategy & Playbook: The Transformation Lessons

Adtalem’s turnaround is a clean case study in what it takes to survive when regulation stops being background noise and starts threatening your right to exist. The company didn’t escape by arguing harder. It escaped by changing the shape of the business. The playbook had a few distinct moves.

Divest to Focus: Selling DeVry—the namesake business—was both symbolic and strategic. It cut away the asset drawing the most scrutiny, freed up management bandwidth, and made the transformation legible to outsiders. Whatever Adtalem was going to become, it couldn’t be tethered to the thing that had become toxic.

Rebrand Without Losing Capability: The Adtalem name created distance from DeVry without throwing away what still mattered: operational muscle, hard-earned systems, and, crucially, accreditation. In regulated industries, you don’t get to reboot from zero. You have to rebuild while keeping the parts that still keep you alive.

Outcomes Over Growth: The biggest shift wasn’t the name, it was the scoreboard. Moving from enrollment-first incentives to outcomes-first metrics changes everything. When NCLEX pass rates and medical training results matter more than raw starts, the organization starts behaving differently—because failure becomes visible, measurable, and expensive.

Regulatory Compliance as Competitive Advantage: In a sector where multiple competitors collapsed under investigations and new rules, simply making it through became a form of differentiation. Adtalem leaned into reforms instead of treating them as temporary friction, and positioned itself as the “good actor” inside an industry that had become politically radioactive.

Wardell understood that the credibility question wouldn’t be won with mission statements. It would be won the old-fashioned way: performance. “I’m going to do the same thing that all of my white male peers who are CEOs of public companies are going to do; I’m going to make the numbers,” she recalled telling people. “I’m going to make earnings. I’m going to make operating income. I’m going to make EPS, and I’m going to be able to talk to the shareholders about how I am driving value.”

And once the turnaround was real—and repeatable—she stepped back. “What I did was I stepped aside to make way for somebody… because it was the right thing to do, and it was the right time for me. I had done everything that I needed to do to turn Adtalem around.”

XIV. Porter's 5 Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: MODERATE-LOW

In healthcare education, you can’t just spin up a new competitor with a slick website and a big marketing budget. Accreditation takes time. Building clinical rotation networks takes even longer, because it’s built on trust and track record. And scaling nursing and medical programs usually means real capital—campuses, labs, simulation equipment, and the infrastructure to run them. The pressure point is that traditional universities keep moving online, and that chips away at the old “we’re the flexible option” advantage.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW-MODERATE

The key suppliers here are people: qualified faculty, especially nurses and physicians who can teach what licensure requires. That labor market is competitive, and it’s not always easy to convince clinicians to trade higher-paying practice roles for the classroom. Still, it’s a broad, fragmented pool—there’s no single faculty “supplier” that can dictate terms across the industry.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-HIGH

Students have gotten more discerning. They can compare programs, price shop, and look up outcomes in ways that were much harder in the DeVry era. And Adtalem has a second class of buyer now: employers. Hospital systems don’t just hire graduates—they can also control access to clinical sites and partnerships. That gives them real leverage, because they sit on the choke point between education and employment.

Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE

There are plenty of alternatives trying to siphon demand: short-form credentials, apprenticeship-style pathways, and hospital-run programs that train talent internally. But medicine and nursing have a built-in defense mechanism: you don’t get to skip the credentialing gate. NCLEX and USMLE aren’t optional. Licensure and program requirements act like guardrails that keep “lighter weight” substitutes from replacing a real nursing or medical pathway.

Competitive Rivalry: MODERATE

This is still a crowded, fragmented market, which means it’s possible to stand out—but you have to earn it. Outcomes, specialty focus, and a broad footprint matter. Traditional universities carry brand advantages, but they’re often slower to change and harder to scale operationally. Meanwhile, every for-profit operator fights through the same reputational haze. Even when the product is strong, the stigma of the sector can drag on the customer decision—and that keeps rivalry intense.

XV. Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: MODERATE

There are real scale benefits here. Build a curriculum once and spread the cost across larger cohorts. Invest in learning platforms and simulation tools, and each additional student makes the unit economics better. The same is true for clinical networks: more students can mean more leverage with partners and a bigger footprint of rotation sites. But healthcare education has a hard ceiling that pure online programs don’t—if you scale too aggressively, quality slips, outcomes fall, and regulators and clinical partners notice fast.

Network Effects: WEAK-MODERATE

This isn’t a social network, but there are some flywheels. Alumni can help with referrals and hiring, especially in tight professional communities like nursing and medicine. And employer partnerships can compound over time: once a health system has worked with your students, hosted rotations, and hired grads, it’s easier to keep doing business together. Still, it’s not a true network-effects business where value explodes with each new user.

Counter-Positioning: WEAK

There’s no structural reason traditional universities can’t compete here. If they choose to build more flexible programs, invest in student support, and operate with the same performance discipline, they can replicate much of the model. Adtalem’s bet on outcomes-driven healthcare education is smart—but it’s not inherently protected from copycats.

Switching Costs: MODERATE-HIGH

Once students are in, switching is painful. Credits don’t always transfer cleanly, progression is often lockstep, and clinical placements are tied to specific program requirements. That creates real friction for students who want to leave midstream. On the employer side, partnerships also have some stickiness—if a hospital has built a dependable talent pipeline with an institution, changing it isn’t free or instant.

Branding: MODERATE (rebuilding)

Brand is complicated here. The DeVry name still carries baggage in some circles, and that shadow doesn’t disappear overnight. But Chamberlain and Ross have built recognizable equity where it matters: among students aiming for licensure-based careers and among employers who care about readiness. Meanwhile, the Adtalem corporate name is still more of a holding-company label than a consumer brand—which is both a limitation and, frankly, sometimes a feature.

Cornered Resource: MODERATE

Accreditation is the big one: slow to earn, easy to lose, and essential for Title IV eligibility. It’s a real barrier that keeps new entrants from popping up overnight. Clinical rotation partnerships are the next layer—less formal than accreditation, but still hard-won relationships that take time and trust to build. And the Caribbean footprint for Ross and AUC provides a distinctive geographic position that, while not impossible to copy, isn’t trivial to recreate at scale.

Process Power: MODERATE-STRONG

This is where Adtalem has earned an edge. Running regulated, outcomes-sensitive education over decades builds operational muscle that newcomers don’t have: compliance systems, student support infrastructure, and the playbooks for improving retention and exam performance. In medicine and nursing, execution is the product. And Adtalem’s experience operating under scrutiny has become a differentiator, not just a scar.

Overall Assessment: Adtalem’s strongest power is Process Power—the operational discipline to deliver education in heavily regulated, outcomes-judged programs—paired with Cornered Resource in the form of accreditation and clinical networks. The company’s remaining strategic work is to keep rebuilding Brand through the only thing that ultimately counts here: results.

XVI. Bull vs. Bear Case

Bull Case:

The healthcare workforce shortage isn’t a passing cycle—it’s a multi-decade supply problem. The U.S. could be short as many as 86,000 physicians by 2036, and recent projections point to a nationwide nursing deficit of roughly 295,800. If Adtalem is going to be in any part of education, this is the part where demand doesn’t politely go away.

The turnaround also looks more like a real identity change than a rebrand. Adtalem sold DeVry, settled major regulatory actions, and rebuilt its portfolio around programs where outcomes are visible and auditable. It’s harder to hide in nursing and medicine. You either produce graduates who pass the exams and get placed, or you don’t.

And that’s where the moat starts to form. Accreditation is slow, expensive, and fragile. Clinical partnerships take years of trust-building and operational consistency. A new entrant can buy ads tomorrow. It can’t manufacture decades of clinical site relationships next quarter.

The enrollment trend supports that story. Total student enrollment reached 90,140, up 11.2% year over year. Management’s framing was that the “reimagined education model” is meeting students where they are—and that the momentum was strong enough to justify raising expectations for fiscal year 2025.

Finally, there’s capital allocation. After the near-death experience of the DeVry era, Adtalem has behaved like a company that remembers what leverage and overreach feel like: paying down debt, buying back stock, and keeping investment centered on the core.

Bear Case:

The stigma of for-profit education doesn’t fully burn off. Political winds can change quickly, and a future administration or regulator could decide the sector is back in the crosshairs. Title IV dependence means regulatory risk is never theoretical.

The broader student debt crisis is another headwind. Income-driven repayment, debt forgiveness debates, and growing skepticism about borrowing for school can dampen demand across tuition-funded education—especially when consumers become more price-sensitive and more outcome-obsessed.

Competition keeps tightening. Traditional universities are pushing harder into online and hybrid healthcare programs, and hospital systems are increasingly experimenting with internal training pipelines that shortcut the need for external providers.

Macro conditions matter, too. In a recession, some working adults go back to school—but others pull back, delay, or choose cheaper alternatives. Education is often countercyclical, until it isn’t.

Execution risk remains real. Walden is the reminder that even a battle-tested operator can misjudge integration complexity and enrollment dynamics after a big acquisition.

And the valuation question cuts both ways. If the market is pricing Adtalem at a discount, it may not be irrational—it may be the market refusing to forget the regulatory history and waiting to see whether growth and outcomes can stay durable.

Key Metrics to Track:

Two KPIs matter most for tracking whether the second act is holding: (1) total enrollment growth by segment—especially the mix of healthcare versus non-healthcare programs—and (2) licensure exam pass rates, including NCLEX at Chamberlain and USMLE performance in the medical schools. Together, they show the two pillars that matter here: demand and outcomes.

XVII. Recent Developments & Future Outlook

By fiscal 2024—and into early fiscal 2025—the story shifted from “rebuild” to “run the playbook.” Adtalem wasn’t just surviving anymore. It was executing.

In its fourth quarter and full-year fiscal 2024 results, the company highlighted a familiar trio: enrollment growth, strong earnings, and plenty of cash generation. Management framed the year as a milestone in its post-DeVry evolution, arguing that its “Growth with Purpose” strategy was widening Adtalem’s footprint in healthcare education—and pointing to 10% enrollment growth in the fourth quarter as proof that momentum was real.

Leadership also tightened its grip on the next phase. The company announced that Steve Beard, its president and CEO, was unanimously elected by the board to also serve as chairman, effective immediately. He succeeded Michael W. Malafronte, who moved from chairman to lead independent director.

Beard had been appointed president and CEO, and joined the board, in September 2021—right as the Walden acquisition closed and the integration work began. Adtalem credited him with being central to that process and to the company’s continuing shift into a healthcare-focused educator at national scale.

His message has been consistent: outcomes first, scale with intent. “At Adtalem, we are training day-one, practice-ready professionals and empowering our more than 90,000 current students and over 350,000 alumni to reach their full potential,” Beard said. “Together—and in partnership with our board—we will continue our mission to scale Adtalem as a force for good, championing access to high-quality education and preparing the clinicians of tomorrow who will transform the landscape of health care.”

The longer-term ambition is clear: become essential infrastructure for healthcare workforce development—less “college operator,” more “talent pipeline” that hospital systems and clinics can’t function without. Whether Adtalem can fully earn that role will hinge on the basics it learned the hard way: consistent execution, a steady regulatory environment, and healthcare labor shortages that keep demand structurally high.

XVIII. Epilogue & Reflections

The Adtalem story has an arc you almost never see in corporate America: from a Depression-era electronics training school, to a for-profit education pioneer, to a regulatory punching bag, to a healthcare education specialist. Each phase demanded adaptation. The rare part is that the company actually made the hard cuts when the easy path was no longer available.

Stephen Beard, the CEO now steering the second act, has a line that captures the posture required for that kind of turnaround: “I always kind of snuck up on people.” He’s talked about being underestimated, and how he learned to use that as fuel. He’s also been direct about why conversations about race and racism still matter—pushing for constructive dialogue, acknowledging what prior generations endured, and describing a personal responsibility to show what’s possible when opportunity is real and expectations are equal.

The broader lessons travel well beyond higher education.

When your core business becomes politically toxic—or regulators decide they’ve seen enough—there’s no amount of messaging that substitutes for structural change. Sometimes that means radical honesty about incentives. Sometimes it means accepting that your namesake brand is no longer an asset. And sometimes it means selling the thing that made you famous, because keeping it would eventually sink everything else.

Adtalem also illustrates a simpler truth: growth for growth’s sake is only celebrated until it isn’t. In regulated industries, misalignment has a timer on it. If outcomes don’t match the marketing, scrutiny isn’t a risk—it’s a certainty.

Zoom out, and this story plugs into the bigger American argument about education itself. Can a for-profit model genuinely serve students, or do the incentives inevitably pull toward exploitation? Is credential inflation reversible, or are we stuck in a world where more schooling is the default answer to every labor-market problem? And as healthcare workforce shortages deepen, can any institution—public, nonprofit, or for-profit—scale fast enough without cutting corners?

Adtalem’s bet is that healthcare education is the rare category where the incentives can line up. The outcomes are measurable. The jobs are licensed. Employers feel the pain in real time. And that makes it harder to survive on hype alone.

The most counterintuitive piece of that bet is the Caribbean medical school portfolio. For years, skeptics dismissed schools like Ross and AUC as degree mills. Yet they’ve produced thousands of practicing physicians—many of whom would not have become doctors through the traditional U.S. bottleneck. When the domestic system constrains supply while demand keeps rising, alternative pathways don’t just appear; they become inevitable. The question isn’t whether the pathway exists. It’s whether it’s run ethically and effectively—whether students are supported, outcomes are real, and the promise matches the probability.

None of this guarantees the ending. Adtalem’s future still depends on forces it can’t fully control: regulation, competition, and how long the healthcare labor shortage stays structurally tight. But the company’s journey from DeVry to Adtalem is proof that second acts in American business can happen—even with reputational baggage so heavy it nearly becomes terminal. If the redemption holds, it won’t be because the public forgot. It’ll be because the company changed what it was, then proved it with results.

For investors, that’s the real question: is this transformation durable, or is it reversible?

The evidence points to something more than a rebrand—divesting the most problematic assets, rebuilding around outcomes, and concentrating on programs where the credential maps directly to a licensed job. But skepticism, once earned, doesn’t evaporate on a quarterly earnings call. The for-profit label may never fully lose its edge.

And the final surprise remains the same: Caribbean medical schools, in the right hands, can be defensible, valuable businesses serving a real need. In a system where the door is intentionally narrow, they offer a side entrance. Whether that side entrance is exploitative or value-creating comes down to execution. By the scoreboard that matters most—graduates entering the healthcare system—Ross and AUC have made their case.

XIX. Further Reading

If you want to go deeper—past the headlines and into the primary sources—these are the documents and books that best explain both Adtalem’s transformation and the larger boom-and-backlash cycle of for-profit education:

- Senate HELP Committee Report (2012) - "For Profit Higher Education: The Failure to Safeguard the Federal Investment and Ensure Student Success"

- Adtalem 10-K Filings (2016, 2020, 2024) - the company telling its own story, year by year, in the language that actually matters: risk factors, strategy shifts, and results

- "Lower Ed" by Tressie McMillan Cottom - a sharp, essential critique of how the for-profit model intersects with inequality, aspiration, and debt in America

- FTC Consent Decree (2016) - the settlement documents that put the DeVry advertising claims—and the consequences—on the record

- AAMC Reports on Physician Shortage - the clearest framing of the supply-demand imbalance that makes medical education, including Caribbean pathways, such a durable market

- Chronicle of Higher Education Archives - contemporaneous reporting that captures the regulatory temperature and the industry’s reputation shift in real time

- Adtalem Investor Presentations (2018-2024) - management’s evolving narrative about outcomes, focus, and why healthcare education is the core thesis

- "Gainful Employment Rule" Federal Register Notices - the policy backbone of the crackdown, and a reminder that in this industry, regulation isn’t background noise; it’s the terrain

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music