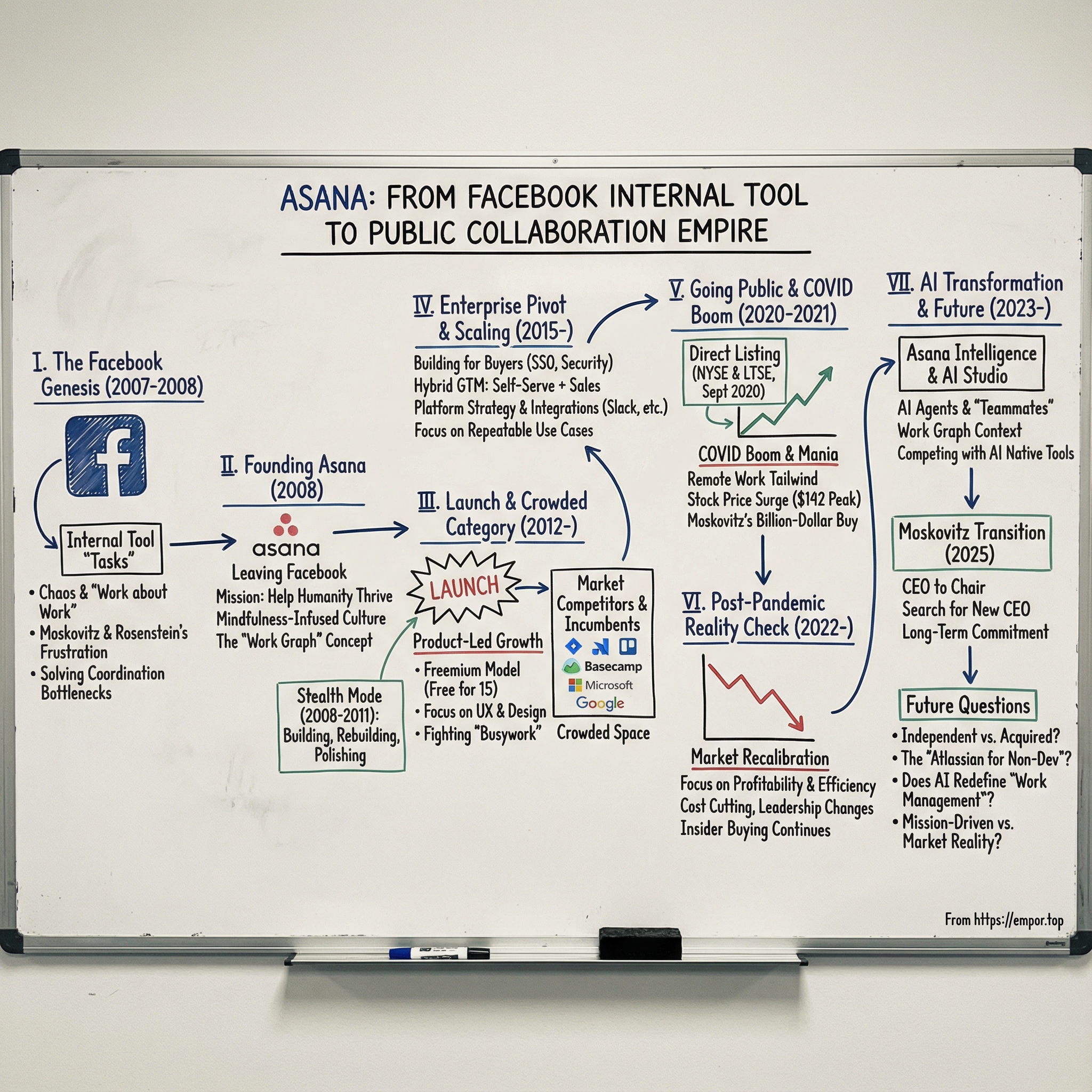

Asana: From Facebook's Internal Tool to Public Collaboration Empire

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Asana’s headquarters sits on a quiet block in San Francisco’s South of Market—sleek, airy, and deliberately calm. The name itself comes from Sanskrit, a word associated with the seated posture of meditation. But the thing Asana is trying to fix is anything but serene.

For nearly two decades, the company has been fighting a very modern kind of chaos: “work about work.” The status meetings that exist only to plan the next meeting. The endless email threads where decisions go to die. The spreadsheets, slide decks, and check-ins that consume entire days while the real work waits on the sidelines.

Today, Asana is an enterprise work management platform used by over 150,000 customers, with millions of users across nearly 200 countries. It brings in more than $700 million in annual revenue, and the company says more than 85% of the Fortune 500 trusts Asana in some capacity. That’s the outcome. The journey to get here was messy, nonlinear, and far from inevitable.

Because the real question in Asana’s story isn’t “how do you build another SaaS product?” It’s: how do you build a company around something as squishy—and as universal—as making work feel less broken? How do you win when the category barely exists at the start, then fills up with copycats, incumbents, and bundled “free” alternatives by the time you’re big enough to matter? And maybe the hardest one: can a mindfulness-infused, mission-driven culture hold together once Wall Street is grading you every quarter?

By the fiscal year ending January 31, 2025, Asana generated $723.88 million in revenue, growing about 11% year over year. That’s a far cry from the early days when growth could feel exponential—but it’s also a sign of something else: the operational discipline investors spent years demanding. Asana also trades on both the New York Stock Exchange and the Long-Term Stock Exchange, a dual listing that signals what the founders have always wanted—room to play the long game.

What follows is the story of how two Facebook engineers walked away from one of the fastest-growing companies in history to solve a problem they believed mattered even more than social networking. It’s a story about product idealism colliding with commercial reality, about culture as a competitive strategy, and about whether the category Asana helped define can support independent giants—or whether, eventually, it gets swallowed by the platforms that can bundle it for free.

II. The Facebook Genesis: Building the Tool That Built Facebook

Picture Facebook in 2007: a company rocketing from a few hundred employees toward a thousand, hiring so fast that org charts became outdated the moment they were printed. The early startup superpower—everyone in one room, decisions made in seconds—was gone. In its place: missed handoffs, duplicated efforts, and a calendar full of meetings whose main output was… more meetings.

Dustin Moskovitz was right in the middle of it. As Facebook’s early CTO and then VP of Engineering, he wasn’t just scaling infrastructure—he was watching coordination itself become the bottleneck. Moskovitz, born in 1984 in Gainesville, Florida and raised in Ocala, had met Mark Zuckerberg at Harvard, where they were roommates. In February 2004, Facebook was born in a dorm room. Within months, Moskovitz joined Zuckerberg and Chris Hughes in taking time off school to move to Palo Alto and turn the project into a real company.

By the time Facebook hit hypergrowth, Moskovitz’s day-to-day had shifted away from consumer features and toward an internal crisis: the company couldn’t keep track of its own work. As he later put it, “for the last year and half I was at Facebook, I was working basically 100 percent of my time on internal communication tools.” The precursor to Asana, he said, was “a task manager that I built for Facebook that gained ubiquitous adoption there, and is still the thing that basically runs the company today.”

Then there was Justin Rosenstein. A Stanford computer science grad, Rosenstein came to Facebook after Google, where he’d worked on products including Google Pages and Gmail Chat. At Facebook, he helped create one of the internet’s most famous bits of UI: the Like button. But just like Moskovitz, Rosenstein’s attention kept getting pulled away from shiny product work and toward a more mundane, more painful reality—teams couldn’t coordinate.

When they started working together, they saw the same pattern everywhere. As the company grew, people were spending more and more time hunting for information, answering emails, and syncing in meetings, and less and less time actually building. Small details—who owns this, what’s blocked, what changed—were consuming enormous energy. And the work that mattered was slipping.

So they built an internal tool. It was called Tasks, and it was deliberately simple: a shared place where work could be captured, assigned, tracked, and discussed without getting lost in inboxes or hallway conversations. It started as an engineering solution, but it didn’t stay there. It spread through Facebook the way the best internal tools always do—team by team, person by person—because it made life easier. Soon, it was being used for everything, including meeting notes and agendas that could be instantly converted into action items. Even the creators were surprised by how broadly it fit.

Watching Tasks take over inside Facebook produced the real breakthrough: the problem wasn’t Facebook. Facebook was just an extreme case of something universal.

Rosenstein later described asking people how much time they spent not doing their actual jobs—time spent on “work-about-work,” phone calls, and emails—and hearing numbers like 60% or even 90%. If software could drive that closer to zero, he argued, it could “potentially double the effectiveness of humanity.”

That was the a-ha moment. The tools everyone relied on—email, spreadsheets, old-school project management software—were designed for a different era: hierarchical companies, linear plans, top-down direction. But modern work wasn’t like that. It was cross-functional, fast-moving, collaborative, and increasingly distributed. The work itself had changed, and the tooling hadn’t.

For Asana, this origin story isn’t just a fun Facebook anecdote. It explains the company’s DNA. Asana didn’t start because two founders spotted a hot market and rushed in. It started because two engineers inside one of the fastest-growing companies on earth couldn’t stand how broken coordination felt—and became convinced it was one of the biggest unsolved problems in modern work.

III. The Founding Decision: Leaving Facebook to Start Asana

On October 3, 2008, Dustin Moskovitz announced he was leaving Facebook. He and Justin Rosenstein—then an engineering manager at the company—were forming something new: Asana.

The timing was almost absurd. Facebook was still years away from an IPO, but even in 2008 Moskovitz’s stake was already worth hundreds of millions of dollars, with an obvious path to “billions” written all over it. In March 2011, Forbes would name him the youngest self-made billionaire, citing his 2.34% ownership in Facebook. Walking away from that kind of trajectory doesn’t happen accidentally. It takes an unusual mix of conviction and idealism.

Moskovitz has always pushed back on the idea that he left because of drama, burnout, or some founder falling-out. “Every time somebody asks me, ‘Why did you leave Facebook?’ they often have these ideas built up in their head… The only one that I ever give, and the only one I think is true is that I left Facebook to start Asana. That’s what I’m still doing.”

Even with that clarity, the exit wasn’t easy. Moskovitz later said telling Mark Zuckerberg was “one of the hardest things he’s ever done.” No theatrics—just a one-on-one on the calendar, a plan for what to say, and then the conversation you can’t rehearse enough.

What they were leaving for, at least on paper, was straightforward: a tool to help office workers manage and track projects and tasks. But the way they talked about it made it clear they thought they’d found something much bigger than a nicer to-do list. Asana’s mission became: “Help humanity thrive by enabling the world’s teams to work together effortlessly.” It wasn’t empty ambition so much as a diagnosis—coordination was broken, and it was quietly draining human potential at scale.

Rosenstein brought a second ingredient that would become inseparable from Asana’s identity: a philosophical, mindfulness-first lens on building a company. “Our thinking at Asana has been influenced by a wide range of wisdom traditions, in addition to Buddhism,” he said. And he was explicit that it wasn’t just a quirky tool for squeezing more output from people: “For the record, our study of wisdom traditions is not merely instrumental in service of capitalist ends; rather, they influence an overall approach to life, of which building a mission-driven company is just one part.”

In interviews, Rosenstein also described mindfulness as survival gear for entrepreneurship. “Certainly, I’ve found equanimity to be essential,” he said. “In some ways I’m impressed with successful entrepreneurs who don’t have a mindfulness practice, from the perspective of ‘damn, it’s hard enough WITH a mindfulness practice…’”

It sounds paradoxical—founders of a productivity company warning against an obsession with productivity. But that tension became part of the brand. For them, mindfulness meant learning to “embrace the inhale and the exhale of the workday,” rather than turning work into an endless optimization problem.

Internally, even leadership was fluid. “We started Asana with Justin as the CEO, and then sort of switched by necessity at some point, so that was path dependent,” Moskovitz explained in a 2025 interview—an early sign that they were willing to evolve structure based on what the company needed, not what looked clean on a pitch deck.

And then there was the advantage almost no startup gets: patience, funded by Moskovitz himself. Years later, Moskovitz would describe Asana as a company that “didn’t need to raise money,” a reality that shaped everything from pace to priorities.

Asana did bring in outside capital—early financing led by Founders Fund, Benchmark Capital, and Andreessen Horowitz, totaling $38.5 million. But those checks weren’t oxygen. They were optional leverage. The founders could afford to move deliberately, betting that product quality and long-term adoption mattered more than quick monetization.

That cushion became both a superpower and, eventually, a critique: it gave Asana the freedom to build the product they wanted, and it also postponed the kind of operational urgency that public markets would later demand.

IV. Building in Stealth: Product Philosophy & Early Years

Asana was officially founded on December 16, 2008. Then… it basically disappeared. For nearly three years, Moskovitz and Rosenstein kept the company in stealth, building, rebuilding, and polishing before most people ever saw a login screen.

That choice wasn’t subtle. In one interview, Moskovitz was teased for it: “You guys took a very long time launching Asana… You wrote a lot of back end stuff to run it. You took a lot longer than it needed to.” But from the founders’ point of view, that was the whole point. They weren’t trying to ship a slightly better project tracker. They were trying to build new infrastructure for how teams coordinate work.

It started with a belief that would shape everything that followed. “User experience is the raison d’etre of this company,” Moskovitz said. At the time, that was an almost contrarian stance in enterprise software, where usability was a nice-to-have and buying decisions were often made by IT, not the people who would live in the product every day. Asana pushed the opposite direction: design was the product. They hired accordingly, and in early profiles the obsession came through—engineers were asked design questions in interviews.

Underneath the clean interface was an equally opinionated model of how work should be represented. The company’s core concept became what it would later call the Work Graph: a way to capture the relationship between the work itself, the information around it, and the people responsible for it—the what, why, and who of getting things done.

Rosenstein explained it by contrasting Asana’s worldview with the one that made Facebook so powerful. “Our personal and professional lives, even if they overlap, have two distinct goals—and they require different ‘graphs.’ For our personal lives, the goal is love (authentic interpersonal connection), and that requires a social graph with people at the center. For our work lives, the goal is creation (working together to realize our collective potential), and that requires a work graph, with the work at the center. Human connection is valuable within a business. But it should be in service to the organizational function of getting work done, and doesn’t need to be the center of the graph.”

That philosophy showed up in a key product decision: Asana made the task—not the project, not the calendar—the atomic unit. A task was the smallest meaningful piece of work someone could complete. From there, everything could connect outward: tasks could live in multiple projects, move across teams, be reassigned, ladder into bigger goals, and carry their full context along the way.

That underlying data model mattered because it enabled what the founders thought modern work demanded: cross-functional collaboration where responsibilities don’t stay neatly inside one project plan. The Work Graph provided, as Asana described it, “a flexible way to organize work,” where “any piece of work can have a one-to-many relationship.” In practice, that meant fewer dead ends—less “where did this live?” and more “here’s how it connects.”

They were also deliberate about where to start. Most work still happened in a browser, so they made the asana.com web experience “first-class,” then built iOS and Android apps. The goal wasn’t just functional. The product had to be “faster, efficient, and beautiful”—something people would actually choose to use.

Culture was treated the same way: intentionally designed. From the beginning, the founders wrote down company values alongside the code, embedding a product-building mindset that emphasized great user interfaces and powerful actions with simple interfaces. They wanted Asana to feel so intuitive that anyone in any company would want it—not because they were forced, but because it made their day better.

Even distribution was designed. They borrowed from Gmail’s early playbook: invitation-only access, which created a little scarcity and helped ensure the product landed with people who were genuinely excited to try it. Just as important, they obsessed over making early adopters successful. The bet was that the strongest growth engine wouldn’t be ads or sales scripts—it would be stories. Teams would hear how Asana helped another team move faster toward its mission, and they’d want that for themselves.

And in hindsight, that stealth period set patterns that never really left Asana: an almost obsessive focus on product quality, a willingness to invest heavily before monetizing, and a mission-driven culture that inspires true believers—even if it can read as impractical to anyone focused purely on near-term numbers.

V. Launch & The Crowded Category Problem

Asana launched commercially in April 2012. And the moment it stepped out of stealth, it ran straight into a problem that had nothing to do with product quality: it was entering a market that was already filling up.

Basecamp had carved out a loyal following as the scrappy, opinionated tool for small teams. Jira was entrenched with developers. Trello’s kanban boards were winning over anyone who thought in cards and columns. And behind them was a long tail of smaller startups, each taking their own swing at the same core pain: how to organize projects without losing your mind.

Then there were the giants. Microsoft and Google didn’t have to “win” work management as a standalone category—they could simply absorb it. Microsoft had Office. Google had what would become G Suite. And history wasn’t kind to independent software companies when the platform owners decided a feature should be “free” and bundled.

So Asana came out with a clear enemy—busywork. The founders framed the company as “on a crusade to rid the world of busywork,” especially the kind that shows up as endless status updates and time-sucking reports. But turning that mission into a crisp category definition was harder. Was Asana project management? Task management? Team collaboration? Work management? For years, the answer depended on who you asked—and that confusion became part of the challenge of selling it.

Their go-to-market leaned into product-led growth. The pricing was intentionally generous: Asana was free for unlimited teams of up to 15 people inside an organization, and then $10 per user per month above that. The strategy was simple: let teams adopt it on their own, prove value first, and only then trigger a purchasing decision.

Early on, Asana didn’t share much in the way of revenue or user counts. But it did offer one tell that mattered: usage. The founders said users had created about 45 million tasks, and completed about 22 million of them. People weren’t just signing up. They were building habits.

The startup also had instant credibility in Silicon Valley. It was “born out of one problem: how do you make people more effective at their jobs?”—built by a Facebook co-founder and a former product manager from Google and Facebook who had “struck out on their own in 2009” after realizing the internal tool mindset could apply far beyond Facebook.

Benchmark partner Matt Cohler, an early backer, put it plainly: “They’re both extraordinary—and exactly the type of the entrepreneurs I want to back. They only left Facebook because they were so passionate about this project. They were thinking about this in their sleep. I talked to them about it all the way back then.”

The first wave of adopters tended to look alike: tech-forward cultures, distributed or remote workforces, and teams doing creative or knowledge-intensive work where coordination overhead was silently brutal. Uber, Airbnb, and other fast-moving startups became early reference customers—proof that Asana could keep up when the pace was high and the stakes were real.

Cohler’s broader thesis was that “there’s so much room for technology to dramatically improve the ability of people to work together.” The open question was whether Asana could claim that space before the category got swallowed by competitors—or flattened by bundles.

As the years went on, fundraising became a proxy for momentum. In January 2018, Asana raised a $75 million Series D at an $825 million pre-money valuation. In November 2018, it raised a $50 million Series E at a $1.5 billion pre-money valuation. Coverage at the time pointed to the same underlying driver: revenue growth was accelerating.

By February 2019, Asana said it had logged “eight consecutive quarters of revenue growth acceleration, measured on a percentage basis.” The flywheel was spinning. The question was whether it could spin fast enough in a market where the gravitational pull of incumbents never really goes away.

VI. Scaling Challenges & The Enterprise Pivot

By 2015 and 2016, Asana ran into a problem that every product-led company eventually has to face: love doesn’t automatically turn into revenue.

Teams were adopting Asana everywhere. The company had crossed 100,000 organizations. But too many of those users stayed on the free tier, and even the paying customers often looked like small teams with small budgets. The enterprise market—the place where deals get bigger, renewals get stickier, and expansion is the whole game—was still frustratingly hard to crack.

So Asana did what it had tried to avoid for years: it started building for the buyer, not just the user.

That meant the unglamorous checklist of enterprise readiness. Single sign-on. Security and admin controls. Compliance. Integrations that made Asana fit into the messy reality of corporate tech stacks instead of asking companies to change their habits.

To lead that shift, Asana leaned on Chris Farinacci, who had joined and served as COO since 2015. He wasn’t a “move fast and ship” founder-type. His background was the opposite: scaling enterprise go-to-market inside institutions like Oracle, and then helping grow Google for Work and Google for Education into multi-billion-dollar businesses. In other words, he knew how to take software that users like and turn it into something companies actually standardize on.

Inside Asana, Farinacci’s job was to professionalize what had previously been almost entirely bottoms-up. He oversaw sales, marketing, business development, and customer operations, and pushed the company toward a more deliberate commercial engine—one that still started with the product, but didn’t end there.

What emerged was a hybrid go-to-market strategy. Asana kept the self-serve funnel: free usage and trials that let teams adopt without permission. But once a team proved value, the company increasingly relied on a direct sales motion to expand that beachhead into a department, then an org, then ideally an enterprise-wide standard. Over time, the free tier became less of a business model and more of a lead engine. Asana even doubled its sales team in 2019 to better convert those internal pockets of adoption into larger contracts.

Farinacci also pushed geographic expansion. “Last year was the year of launching heavily in Europe, while this year is the year of launching heavily into Asia,” he said in an interview. And he pointed to increasingly recognizable customers—names like Sony and Disney—as proof that Asana was finally showing up in “real” enterprises, across industries.

He also framed the category as still early. Work management, he argued, was at less than 3% penetration. That wasn’t just optimism—it was the rationale for why Asana could justify investing heavily: if the market was still mostly untouched, the prize for becoming the default system of record for work would be enormous.

At the same time, Asana doubled down on a platform strategy. It built integrations into the tools large companies already lived in—Google Drive, Jira, OneDrive, Dropbox, Slack—because the goal wasn’t to replace everything. It was to become the layer that connected everything. The more Asana plugged into existing workflows, the more it could sit at the center of them.

By the time the company went public, it could point to global customers using Asana to run serious, high-stakes work—Amazon, Japan Airlines, Sky, and Under Armour among them—and it had grown to more than 107,000 paying customers, alongside millions of free organizations across 190 countries.

Just as importantly, Asana’s ideal customer profile started to sharpen. Marketing teams coordinating campaigns. Operations teams running cross-functional initiatives. PMOs standardizing project execution across an organization. Not flashy, not viral—but repeatable. And in enterprise software, repeatable is what scales.

This era cemented the blueprint that would define Asana’s public-company story: product-led acquisition feeding enterprise expansion. It worked. But it also came with a tradeoff. Running two engines at once—self-serve growth and enterprise sales—was powerful, and expensive. And once Wall Street entered the picture, that expense would stop being an internal choice and start being a quarterly debate.

VII. The Direct Listing Decision & Going Public

By 2020, Asana had reached the point where going public wasn’t just possible—it made strategic sense. Founded back in 2008, the San Francisco company had grown to $181 million in sales for the 12 months ended July 31, 2020. The question wasn’t whether it could access the public markets. It was how.

Asana chose the path that fit its personality: the direct listing. It filed confidentially for one in January 2020. Unlike a traditional IPO, a direct listing doesn’t create new shares or raise fresh capital. Existing shareholders simply begin selling on the public market, without the usual underwriter-led roadshow and pricing machinery. At the time, only a handful of notable companies had taken this route—Spotify, Slack, and Palantir among them.

Moskovitz’s reasoning was blunt and very Asana: they didn’t need the money. He said the company was drawn to the “efficient pricing” of a direct listing and framed it as a fairness issue, too—“a more fair, democratic process for employees and shareholders to have the opportunity for liquidity at the same time.”

The setup made that decision credible. By the time Asana listed, it had raised more than $450 million from investors including G Squared, Founders Fund, and 8VC. And Moskovitz’s personal fortune provided a cushion most companies can’t dream of. This wasn’t a company going public to survive. It was a company going public to graduate.

The New York Stock Exchange set a $21 reference price, and Asana prepared to trade under the symbol ASAN. On September 30, 2020, trading began: the stock opened at $27 and closed at $28.8. By the end of the debut, Asana was valued at about $5.5 billion.

In its disclosures, Asana showed the kind of fundamentals investors like to see in SaaS, even if profitability was still out of reach. About 40% of revenue came from outside the U.S., with the product used across 190 countries. Gross margins were high—87% in the first half of the year, roughly in line with the prior fiscal year’s 86%. The engine was efficient. The question was how much the company would spend to keep it growing.

And the timing couldn’t have been more on-the-nose. Asana hit the public markets right as remote work turned from perk to default, and “coordination” became a board-level problem overnight. Markets had rebounded from the pandemic panic, and September 2020 marked a broader resurgence in tech listings. Collaboration and project management tools were suddenly must-haves, not nice-to-haves.

Over the following year, that narrative powered a rocket ship. The stock debuted at $27 and later climbed as high as $142, with the company at one point valued around $30 billion.

In August 2021, Asana made another values-coded move: it dual listed on the Long-Term Stock Exchange, built explicitly for companies that want to signal long-term orientation to shareholders.

And Moskovitz reinforced yet another piece of Asana’s identity: it wasn’t looking to buy its way into the future. He noted Asana hadn’t done any acquisitions and didn’t expect that to change—sticking with a purist preference for organic product development over bolt-on growth.

VIII. The COVID Boom & Post-Pandemic Reality Check

The pandemic years were both Asana’s biggest tailwind and the start of its reckoning. As remote work became default, the need for coordination software stopped being a “nice-to-have” and became survival gear. Asana’s revenue climbed quickly—up from $378.44 million in fiscal 2022 to $547.21 million in fiscal 2023, then to $652.5 million in fiscal 2024. Growth was still strong, but you could already see the slope beginning to flatten.

On the public markets, the story turned into a full-blown mania. Asana’s all-time high closing price came on November 9, 2021, at $142.68. After breaking out of its post-listing range, the stock ran hard—rallying to over $100 in a matter of months, and reaching an intraday high of $145 on November 15, powered by strong quarterly results and peak optimism about “work from home” staying permanent.

On the business side, the numbers seemed to validate the hype. By December 2021, Asana said it had grown to 114,000 customers, with two million paid seats globally. And critically, 739 of those customers were spending $50,000 or more on an annualized basis. The enterprise motion wasn’t theoretical anymore—it was showing up in the mix.

But underneath the celebration was the tension that would define the next phase: growth that was expensive. In Q3 fiscal 2022, Asana posted year-over-year revenue growth of 70% to $100 million. At the same time, losses widened compared to where the company had been in calendar year 2020.

Cash flow told the same story. One quarter captured it cleanly: free cash flow was negative $29.5 million versus negative $19.5 million a year earlier. Even as Omicron reinforced the idea that digital coordination tools were here to stay, the market’s mood was changing. Investors were starting to punish richly valued growth stocks—especially the ones still burning a lot of cash.

Then came the crash. Asana’s shares fell hard alongside tech and growth stocks more broadly, as the market recalibrated for a post-pandemic world and higher interest rates. Commentary at the time noted the stock had dropped more than 70% from its late-2021 high. Later takes framed it even more starkly—down close to 90% from the peak—despite continued belief that the product itself was solid and the market opportunity was real.

Asana was hardly alone in losing money, and investors generally understood that high-growth software companies burn cash. What spooked people was the scale. One snapshot from this period: in the fourth quarter, net loss was $90.0 million and cash from operations was a negative $39.3 million. Management also guided for fiscal 2023 revenue of $527 million to $531 million, alongside a non-GAAP operating margin around -45%, implying substantial operating losses at the midpoint.

The narrative flipped from “growth at any cost” to “show us profitability.” Asana’s response was to start tightening. It cut costs by reducing sales and marketing spending from US$435.0 million in 2023 to US$392.0 million in 2024, and general and administrative expenses from US$166.3 million to US$141.3 million.

Around the same time, Asana also made a key operating transition at the top. In September 2021, the company announced Anne Raimondi as its new Chief Operating Officer, succeeding Chris Farinacci, who had served since 2015. Asana said Raimondi would lead and scale growth and global business operations and go-to-market teams—including sales, marketing, customer success and support, and business development—reporting directly to Dustin Moskovitz.

Raimondi arrived with a résumé built for exactly this moment: more than 20 years in product and business leadership across fast-growing SaaS companies. Before Asana, she’d been Chief Customer Officer at Guru, SVP of Operations at Zendesk, Chief Revenue Officer at TaskRabbit, and held senior roles at SurveyMonkey and eBay. She’d also joined Asana’s board in 2019 as its first independent director—so she wasn’t walking in cold.

And if Wall Street wanted a signal of conviction, Moskovitz provided one in the loudest way possible: he bought more than $1 billion of Asana shares at prices higher than where they later traded. In an era when many founders were quietly de-risking, Asana’s founder was doing the opposite—turning the post-hype collapse into one of the most unusual insider-buying stories in public SaaS.

IX. The AI Transformation & Current Strategy

After the post-pandemic whiplash, Asana needed more than cost cuts and a tighter sales motion. It needed a new story—one that wasn’t just “project management, but nicer,” and wasn’t easily bundled away by Microsoft or Google.

That’s where “Asana Intelligence” came in. Starting in 2023, Asana began rolling out AI features across the platform, pitching a familiar promise with a very Asana spin: digital assistants that could automate tasks, surface insights, and generate content—less busywork, more real progress.

But the real question wasn’t whether Asana could add AI. Everyone could. The question was whether AI would become a true differentiator that justified premium pricing—or just another checkbox feature competitors would match within a quarter or two.

Asana’s big swing was Asana AI Studio, a no-code tool for building AI agents directly inside the workflows teams already run in Asana. The company positioned it as more than a summary engine. The pitch was “teammates,” not “chatbots”: agents that work alongside a team, take on coordination and intake, and help orchestrate work from planning through execution and reporting.

Moskovitz framed it as a step-function in accessibility: customers could design workflows and configure agents simply by giving instructions in plain language. The goal, he said, was to make it dramatically easier for companies to improve the quality of work while moving faster.

Asana pointed to its own research as proof the market still hurt. In its 2024 State of Work Innovation report, the company said employees spent 53% of their time on low-value busywork, and only 21% believed teams across their organization collaborated effectively. Same diagnosis as 2008—just at global scale—and now AI was the new tool to attack it.

Under the hood, Asana argued it had an advantage many AI add-ons didn’t: context. Leaders tied AI Studio back to the Work Graph, Asana’s system of record for who’s doing what by when. The claim was straightforward: AI gets more useful when it’s grounded in real, structured work data—not just scattered documents and chat logs. That context awareness, they said, is what makes AI Studio valuable when rolled out across an organization.

Early beta signals sounded encouraging. Morningstar, for example, said that building smart intake workflows with AI Studio helped reduce timelines by an average of two weeks per completed workflow, cutting down the time it took to review requests and gather needed information.

Asana also made it clear it wasn’t betting on a single model provider. Users could choose among multiple language models to power agents, including Anthropic’s Claude 3.5 Sonnet and Claude 3 Haiku, and OpenAI’s GPT-4o and GPT-4o mini.

While the product narrative shifted toward AI, Asana also worked to prove it could operate like a grown-up public company. In fiscal 2026, it announced it had achieved its first positive non-GAAP operating margin in company history—a milestone investors had been waiting years to see. In Q3 fiscal 2026, Asana said it exceeded the high end of guidance, raised the high end of its full-year revenue and non-GAAP operating income guidance ranges, and announced “AI Teammates,” collaborative agents designed to understand the context of work across an organization and deliver business outcomes.

Third-party validation followed. Asana said it was recognized as a Leader in the 2024 Gartner Magic Quadrant for Collaborative Work Management. And it highlighted a new integration with AWS’ Q Business announced in the main product keynote at AWS re:Invent 2024, positioning it as a way for employees to find information across third-party applications without leaving Asana.

Then, in March 2025, came the leadership news that reshaped everything. Asana announced that Dustin Moskovitz had informed the board of his intention to transition from CEO to Chair once a new CEO begins. The board retained an executive search firm, and Moskovitz said he would remain CEO until the successor starts. He also said he intended to maintain his Asana shareholdings, reflecting his view that the company was positioned for long-term growth.

The market didn’t take it calmly. The retirement plan was announced alongside the company’s fourth-quarter earnings report, and Asana’s stock dropped more than 25% in after-hours trading.

For Moskovitz, the message was part gratitude, part handoff. He reflected on nearly 17 years building Asana into a platform he said was trusted by over 85% of the Fortune 500. And he explained what the next chapter would look like: as Chair, he would focus on product vision, strategic guidance, and navigating the AI landscape—while stepping away from day-to-day operational demands. He also said he felt called to dedicate more energy to global challenges through Good Ventures and Open Philanthropy.

Around that time, Moskovitz held a 53% stake in the company. And in the weeks following the announcement, he added to it—buying roughly 3.375 million shares for about $49 million. Those purchases, made at prices between $12.91 and $15.64, stood in sharp contrast to Justin Rosenstein’s actions in the same period: Rosenstein sold about 1.15 million shares between January and March 2025 for roughly $23.8 million.

Asana’s next phase was suddenly defined by two transitions at once: from “work management” to AI-driven work orchestration—and from founder-led certainty to the uncertainty of a CEO search, playing out in real time under public-market scrutiny.

X. Business Model & Unit Economics Deep Dive

Asana’s business model is a pretty clean example of the freemium SaaS playbook. But when you look under the hood, the unit economics show both why it works—and why it’s been hard to turn into effortless profitability.

At the center is Asana’s Work Graph, which “combines tasks, projects, portfolios, goals, and the relations among those.” Commercially, Asana runs a subscription model: a free basic plan at the top of the funnel, and paid tiers beneath it. In practice, that free plan doesn’t just drive self-serve conversions. It also feeds leads into a direct sales motion that can turn pockets of usage into enterprise accounts.

Asana describes it simply: “Asana follows a subscription-based model with three premium tiers and a free basic plan.” And while the product can start with a single team, the revenue mix leans heavily toward the bigger, more feature-rich plans. As the company notes, Enterprise and Business subscriptions contribute significantly to revenue, and larger accounts represent a substantial portion of what Asana brings in.

The funnel usually looks like this: a team discovers Asana through word of mouth, or through a champion who used it at a previous company. They start on the free tier for a specific use case—campaign planning, an operational process, a product launch. Then the expansion happens the way product-led companies dream it will: more teammates get invited, the workflow becomes the team’s default, and Asana quietly turns into infrastructure. Eventually, the team hits a wall—team size, admin controls, security requirements, or just the need for more power—and that’s when the free usage turns into a paid decision.

By recent disclosures, the enterprise end of that funnel has continued to grow. Asana reported that customers spending $5,000 or more on an annualized basis reached 24,297 in Q1, up 10% year over year. In another snapshot, it said the number of core customers spending at least $5,000 annually rose to 21,646—an 11% increase since 2023—while customers spending $100,000 or more annually grew 20% to 607. The direction is right: more large customers, more meaningful contracts.

But retention and expansion—the thing that makes SaaS compounding feel magical—has been more mixed.

Net dollar retention measures whether existing customers are spending more over time, and in Q1 Asana said its overall dollar-based net retention rate was 95%, with Core customers at 96%. Those numbers are down from the company’s peak years, when it talked about net dollar retention in the 107% to 115% range. That doesn’t mean customers are fleeing; it means expansion has slowed. And in modern SaaS, slower expansion is often what turns “great product adoption” into “why aren’t the margins improving faster?”

You can see how this has fluctuated across quarters. In an earlier period, Asana reported overall dollar-based net retention of 100%, Core customers at 102%, and customers spending $100,000 or more at 108%. By Q2 fiscal 2025, it reported overall net retention of 98%, Core customers at 99%, and $100,000-plus customers at 103%. The takeaway: the biggest customers still expand, but not with the same force they did in the boom years.

On the cost side, Asana has been spending on the three big buckets you’d expect: keeping the platform running, heavy R&D to push the product forward, and sales and marketing to convert and expand accounts—plus customer success to keep those expansions from churning back out.

The margin profile explains why Wall Street has been so intense about discipline. Asana’s gross margins have been strong—around the high-80s, about 87%—but operating results long reflected how aggressively the company invested in both product and go-to-market. Recently, that began to change. In the first quarter of fiscal 2026, Asana reported non-GAAP operating income of $8.1 million, or 4% of revenue, compared with a non-GAAP operating loss of $15.8 million, or 9% of revenue, in the first quarter of fiscal 2025. That’s a real swing—less a single-quarter blip and more a signal that the cost structure was finally bending.

The same story showed up later as well: in Q4 fiscal 2025, Asana said GAAP operating margin improved 590 basis points year over year, and non-GAAP operating margin improved 820 basis points.

Through all of this, the strategy underneath hasn’t changed. Asana still believes land-and-expand is the winning approach: start with a team, prove value, and then standardize across the organization. Or as the company put it, “Software purchasing is becoming increasingly democratized and complex,” and it pushes back on the idea that you have to pick just one go-to-market model. Asana has chosen both—self-serve to start the relationship, and sales-led expansion to scale it.

XI. Playbook: What Makes Asana Different?

Asana’s strategy can look, from the outside, like a familiar SaaS playbook: freemium at the top, enterprise contracts at the bottom, a steady march upmarket. But there are a few ingredients that have consistently made the company feel… different. Sometimes that difference has been a competitive edge. Sometimes it’s been a self-imposed constraint. Either way, it’s central to understanding why Asana became Asana.

Several distinctive elements have defined Asana's approach to company-building:

Mission-Driven Culture: Rosenstein has been unusually explicit about culture as a first-class business input, not an HR afterthought. “Asana receives a lot of recognition for its business success, culture, and employee engagement. As the company enters a phase of intense growth, I've been considering what will be required to continue this success.” His principles—“Remember why your work matters, to the world and to you, every day. If it doesn't matter to the world or to you, change your role, or your mind, until it does”—aren’t just inspirational quotes. They’re meant to be an operating system for how people choose what to do, and what not to do.

And it shows up in how Asana talks about execution itself:

"Speed means nothing; velocity means success. Mindful is smooth; smooth is fast. Mindfulness self-corrects, so it's always going the right way."

Design-First in Enterprise Software: Asana bet early that usability wasn’t decoration—it was distribution. While competitors raced to pile on features, Asana kept coming back to the same belief: “The success of Asana relies on its simplicity.” When Asana launched, “consumer-grade” design in enterprise software was still rare. As the category matured, everyone got better at UI. But Asana kept treating design as a core product decision, not something you do after the roadmap is set.

Product-Led Growth Meets Enterprise Sales: The company never fully abandoned its original idea that the best sales pitch is a teammate inviting you into a project. But it also accepted a hard truth: enterprises don’t standardize on a tool without a real go-to-market machine behind it. That hybrid is why Raimondi made sense as COO. As Asana described her: “She is a seasoned, customer-centric operator with over 20 years of experience leading product and business teams at fast-growing companies like Guru, Zendesk, TaskRabbit, and SurveyMonkey. A longtime Asana customer, Anne joined our board of directors in 2019 as its first independent member.” The point wasn’t just experience—it was someone who could connect the elegance of product-led adoption to the rigor of enterprise expansion.

Founder-CEO Dynamics: There’s “founder-led,” and then there’s Moskovitz’s version of it. As one account put it: “The CEO of American software firm Asana has hoovered up shares worth a lot more: USD 166m, last year alone. Once you factor in prior years, his insider buys amount to well over USD 1bn—most likely the largest ever stretch of purchases made by a corporate insider.” Whatever you think of the financial wisdom of that move, the signaling is unambiguous: he saw Asana as a long-duration bet, and he was willing to back that belief with his own capital.

Lessons from Facebook: Asana imported Facebook’s strengths—fast iteration, shipping, product intuition grounded in real usage—but rejected the core metaphor that powered Facebook itself. “But Asana isn't a social network. Why? Because, as Justin outlines, the social graph doesn't target the problem of work.” Facebook put people at the center. Asana put the work at the center. That difference sounds semantic until you build a product around it. Then it becomes the whole thing.

The Platform vs. Point Solution Tradeoff: Asana has spent years widening its scope beyond “project management” without tipping into the bloat that makes users churn. As one line captured it: “Asana, and work management more broadly, will help navigate all that. It goes beyond having project management, project portfolio management, or a PMO.” That’s the platform ambition—be the place where work connects across teams, tools, and goals. The risk, of course, is becoming too generic, or too heavy, or too expensive to justify when alternatives are one click away.

And for all the volatility of the last few years, some observers still framed Asana as a long-term category fixture: "The kind of software that Asana is offering should stay in a secular growth trend, with Asana bound to remain in the top five of companies globally who offer this kind of service. Moskovitz has vowed to not take the company private, and he would be unlikely to sell even if there was an offer on the table."

XII. Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Competitive Rivalry (HIGH): Asana operates in a knife fight. The work management market is packed with credible options, and as one observer noted, many vendors have been forced to aim higher because the easy parts of the market are getting too crowded. Smartsheet, for example, rolled out more scalable enterprise offerings and shipped its own generative AI capabilities. Other familiar names in the ring include Wrike, Trello, and Monday.com.

That crowding has pushed everyone toward the same battleground: the enterprise. “With the lower end of the market beginning to look saturated and the middle more competitive, the focus from Asana and its core competition has had to shift to the enterprise.”

And when everyone is chasing the same customers, feature parity becomes the default. Most major platforms can now do the basics. Differentiation lives in the edges: user experience, integrations, admin control, security, and the credibility to be rolled out at scale without breaking.

Threat of New Entrants (MEDIUM): On the surface, the barriers to entry look low. A small, competent team can ship a task tool. The hard part is everything that comes after: trust, reliability, compliance, distribution, and the slow grind of becoming a system an organization standardizes on.

Competitors have shown how quickly the category can expand, too. As one quote described Monday.com’s arc: it started as project management software, then kept adding tools until it could credibly market itself as an “all-in-one” platform. That pattern matters because it’s not just new companies that can enter—the companies already here can also expand sideways into Asana’s territory.

AI cuts both ways. It lowers the cost for startups to build impressive products quickly, but it also gives incumbents a new set of building blocks they can bolt onto existing distribution.

Buyer Power (HIGH): Buyers have leverage because they have choices—and switching, while annoying, isn’t impossible. Moving off Asana means re-creating workflows, migrating historical project context, and changing habits. That’s real friction. But it’s still far easier than ripping out a core system like an ERP or CRM. And because there are so many alternatives at different price points, price sensitivity shows up fast.

Supplier Power (LOW): Asana doesn’t depend on a single choke-point supplier. Cloud infrastructure is a commodity, with AWS, Google Cloud, and Azure all competing aggressively. Hiring top talent is always competitive, but Asana has historically leaned on its mission-driven reputation as part of the recruiting pitch.

Threat of Substitutes (HIGH): The most dangerous substitutes aren’t always the obvious competitors. They’re the platforms that can bundle “good enough” workflow tools into software companies already pay for. Microsoft 365 includes Planner, Lists, and task functionality inside Teams. Google Workspace offers its own task capabilities. For a price-sensitive buyer, “free” is a brutal competitor.

Then there are the everyday tools people never quite abandon: email, Slack, and spreadsheets. They’re messy, but they’re universal—and many organizations keep managing work inside them rather than committing to a purpose-built system.

Finally, there’s the emerging wildcard: AI assistants. If agents can actually take on coordination and execution autonomously, the need for explicit work management systems could shrink—or at least change shape.

XIII. Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies (DEVELOPING): Shipping software scales beautifully. Selling and supporting it doesn’t. Asana gets real leverage on the R&D side—build a feature once, roll it out everywhere—but the expensive parts of the machine (sales, customer success, support) still scale closer to headcount. And compared to true giants like Salesforce or Microsoft, Asana’s scale advantage is still emerging, not entrenched.

Network Effects (WEAK): Asana isn’t a social network where every new user strengthens the product for everyone else. It’s largely single-tenant: your company using Asana doesn’t make Asana inherently better for mine. The best “network-ish” effect here comes from integrations—the more tools Asana connects to, the more useful it becomes. But that’s a light, ecosystem-style pull, not a hard multi-sided marketplace flywheel.

Counter-Positioning (HISTORICAL): Early on, Asana won mindshare by being the anti-enterprise enterprise tool: clean, simple, and actually pleasant to use. That was a real wedge when most incumbents looked and felt like legacy software. Over time, that gap narrowed. Monday.com’s bright UI, Notion’s minimalism, and widespread UX improvements across the category have all chipped away at what used to be Asana’s sharpest contrast.

Switching Costs (MODERATE): The longer a team runs on Asana, the more it becomes part of their operating system—templates, workflows, approvals, habits, and the shared memory of how work gets done. That creates real friction. But it’s not the kind of lock-in you see with databases or deeply embedded infrastructure. Data can be exported; the heavier lift is people: changing routines, retraining teams, and re-building trust in a new system.

Branding (MODERATE): Asana has a strong brand with tech-forward teams and knowledge workers who care about design and clarity. Its mindfulness-infused identity also resonates with a certain kind of buyer and builder. The downside is reach: in more traditional enterprise environments, Asana’s brand doesn’t carry the automatic weight of the biggest incumbents.

Cornered Resource (WEAK-MODERATE): Moskovitz’s majority stake—around 53%—has effectively given Asana a form of patient capital most competitors can’t replicate, especially in public markets. The Facebook origin story and network helped early adoption and recruiting, too. But there’s no singular protected asset—no must-have patent portfolio or proprietary IP—that creates a hard barrier around the business.

Process Power (DEVELOPING): Asana’s internal way of building—design-first, heavy dogfooding, values-driven product decisions—has become real institutional muscle memory. Its product-led growth engine has also generated years of usage data that informs what gets built and what gets cut. Still, compared with the most battle-tested enterprise software companies, Asana’s enterprise sales and expansion playbook has been a work in progress.

Overall Assessment: Asana has real strength across several of the Seven Powers, but none that fully “locks” the market in its favor. Its outcome hinges on execution—especially whether AI becomes a durable advantage, not just a temporary feature race.

XIV. Bull vs. Bear Case

The Bull Case:

AI actually changes what Asana is. Management’s argument is that this isn’t just “we added a chatbot.” It’s that Asana’s architecture—especially the Work Graph—gives it an edge in making AI useful in the real world of work. As the company put it: "We also feel like we are so uniquely positioned to be able to use AI to augment our customers' experiences. That really is through our systems architecture, through the Work Graph, which you've heard us talk about for many years. It's this system of record where at any given time, you know who is doing what by when."

Profitability stops being a promise and becomes a pattern. When Asana "Achieved first positive non-GAAP operating margin in company history," it wasn’t just a headline—it was proof that the business can bend toward discipline. If revenue growth stabilizes and the company keeps finding operating efficiencies, the bull case says margins keep expanding from here.

The enterprise motion finally hits escape velocity. Asana has long claimed a foothold—"Trusted by over 85% of Fortune 500 companies"—but the real upside comes if those footholds turn into standards. Bigger deal sizes, wider rollouts, and stronger expansion would turn Asana from “a tool some teams use” into “how work runs here.”

Founder alignment stays unusually strong. Moskovitz stepping back from the CEO role could be read as risk. The bull case reads it as a handoff, not an exit—especially because he has said he intends to maintain his Asana shareholdings. The broader context matters too: "Moskovitz said in his Monday retirement statement that he plans to focus more on his philanthropic endeavors, such as Good Ventures and Open Philanthropy... In 2010, Moskovitz signed the Giving Pledge. Good Ventures, which was co-founded by Moskovitz and his wife Cari Tuna, donated $30 million to ChatGPT maker OpenAI over a three-year period in 2017." In other words: he has other things he could do, yet he’s still heavily invested in Asana’s long-term outcome.

And the market itself may still be early. Farinacci once estimated "less than 3% penetration." If that’s even directionally right, the category has decades of runway—assuming Asana can keep its place near the front of the pack.

The Bear Case:

Commoditization keeps grinding everything down. As the category matures, the basics become interchangeable. If core functionality becomes table stakes, differentiation gets harder, pricing power weakens, and switching becomes less scary.

Microsoft and Google make “good enough” inevitable. Bundling is a ruthless form of competition: as productivity suites add more sophisticated work management features, standalone tools have to justify why they’re worth paying for at all—especially during budget scrutiny.

Public-market fragility becomes self-fulfilling. One recent snapshot captured the tension: "Asana reported breakeven results in its most recent quarter, with revenue increasing by 10% to $188.33 million. Despite this, the stock faced challenges due to the CEO's retirement announcement and intensifying competition in the work management software market." Even when operating results improve, sentiment can overwhelm fundamentals.

Competition keeps coming from every direction. Notion isn’t just a niche wiki anymore—it has "becoming the darling of designers, entrepreneurs and agile managers. In 2024, the platform claims over 30 million users worldwide." Monday.com’s market cap advantage reinforces the idea that Asana isn’t the default winner. And ClickUp and others keep pressuring from below with aggressive pricing and broad feature sets.

Skepticism about spending doesn’t disappear overnight. As one critical take put it: "It's actually a great product. The company was founded in 2008 and works well. However it has been a poorly managed public company. Asana has been spending a tremendous on Sales & Marketing and Stock-based compensation." Even if the company tightens the model, these narratives can linger—and they matter when you’re being repriced every day.

AI could also be the destroyer, not the savior. If AI agents truly handle coordination end-to-end, the need for structured work management tools could shrink—or at least shift away from the interface Asana sells today.

And, finally, volatility itself is part of the bear case. "The Asana 52-week high stock price is 24.50, which is 70.4% above the current share price. The Asana 52-week low stock price is 11.58." Big swings signal a market that still can’t decide what Asana is worth—or what it becomes next.

KPIs to Watch:

The two metrics that matter most for tracking Asana’s trajectory:

-

Net Dollar Retention Rate (especially for customers spending $100K+): This tells you whether Asana is becoming more valuable inside existing customers over time. Great SaaS companies often hold 110%+ net retention. Asana’s more recent results around the high-90s to low-100s suggest expansion has cooled—and re-accelerating it is crucial.

-

Number of Customers Spending $100K+ Annually: This is the cleanest read on whether the enterprise pivot is working. Growth in these accounts validates the strategy, increases revenue durability, and creates the potential for meaningful multi-year expansion.

XV. Epilogue: The Future of Work Management

As this story reaches late December 2025, Asana is sitting on a familiar kind of edge—the kind it’s been approaching, one way or another, since the day it left Facebook. The founder who took a coordination hack from a fast-growing startup and turned it into a public company with more than $700 million in annual revenue has announced he’s stepping back from the CEO role. The category Asana helped define has moved from wide-open frontier to crowded battlefield. And AI isn’t just adding features—it’s threatening to change what “managing work” even means.

"The vision that Asana's founders set out from the beginning is a multi-year, decades-long journey because we are solving a big, difficult problem. Ultimately, we want Asana to be mission control for enterprises of every size."

The first big question is the simplest one: does Asana stay independent? Everything the company has signaled says yes. "Moskovitz has vowed to not take the company private, and he would be unlikely to sell even if there was an offer on the table." With majority ownership, he has the control to block a deal. With patience—both personal and philosophical—he has the willingness to keep playing the long game.

And yet, the strategic logic for an acquisition will always hover. Potential acquirers like Salesforce, Adobe, ServiceNow, and Oracle each have a plausible reason to want Asana. Salesforce could pull work management closer to the system where revenue teams already live. Adobe could connect creative production to campaign execution. ServiceNow could extend its enterprise workflow footprint into the day-to-day coordination layer. Oracle could bundle it into a broader enterprise suite. Still, none of those endings seem imminent given the founder’s stated intent.

The second question is the outcome Asana has been implicitly chasing for years: can it become the Atlassian for non-dev teams? Atlassian built a multi-billion-dollar enterprise standard by owning how software teams plan and ship work through Jira and Confluence. Asana’s analog would be marketing, operations, and cross-functional execution—work that touches everyone, but has historically been managed in spreadsheets, inboxes, and meetings. As one critique-compliment put it: "It's generally nicer than Jira in just about every way you can imagine. However, it'll never take over Jira in most shops because it doesn't have all the integrations Jira has." In other words: Asana doesn’t need to beat Jira at Jira. It needs to win everywhere Jira never tried to be.

The third question is the one that could upend all of it: is “work about work” even the right framing in an AI world? Asana keeps citing the same diagnosis it was built on—"Employees currently spend 53% of their time on low-value busywork, and only 21% of people believe teams across their organization collaborate effectively." But if AI agents can take on coordination directly—routing requests, generating plans, updating stakeholders, enforcing process—then the center of gravity may shift from managing tasks to managing outcomes. Work management might become less about telling humans what to do, and more about supervising systems that do it with them.

That shift is why Asana has been so emphatic about enterprise-grade AI, not just novelty features:

"I sort of stole the promise of this question on the fly, but I did have written down here along the same lines, 'You focused a lot on the importance of security and governance, can the Dustin Moskovitz of 2008 imagine caring so much about these enterprise realities?' Well, I hope so. I think the risk is that customers YOLO it because that's what they think they need to do to succeed, but not all of them will be like that. But yeah, that's the pitch we make is this is an enterprise-grade AI platform."

And then there’s the human question—arguably Asana’s most distinctive one. Can a mission-driven company, built on mindfulness principles and long-duration thinking, win in a market that increasingly rewards ruthless efficiency and relentless competition?

For now, Moskovitz’s own posture is a bridge between the old Asana and whatever comes next:

"Moskovitz will remain CEO until a successor begins and intends to maintain his shareholdings in Asana, reflective of his view that the company is positioned for long-term growth. 'As I reflect on my journey since co-founding Asana nearly 17 years ago, I'm filled with immense gratitude.'"

The story that began in a Facebook conference room in 2007—when two engineers realized coordination was quietly crushing human potential—keeps going. Whether Asana becomes “mission control” for modern enterprises, or a cautionary tale about idealism colliding with commoditization, will be written the same way the market writes all verdicts: in the quarters and years ahead.

XVI. Outro & Further Reading

Top 10 Long-Form Resources:

- "The Work Graph" - Dustin Moskovitz (Asana Blog) - The clearest statement of Asana’s core product thesis, straight from the source

- "Conscious Leadership at Asana" - Wavelength Blog - A deeper look at the mindfulness-infused culture that shaped how Asana builds and operates

- S-1 Filing & Annual Reports (SEC.gov) - The primary documents for Asana’s financials, strategy, and risk factors—dense, but definitive

- "The Making of Asana" - First Round Review - One of the best early narratives on the founding story and product decisions

- "How Asana Built a Company on Mindfulness" - Forbes - Profiles that connect the company’s culture, leadership, and business ambition

- Dustin Moskovitz interviews on Stratechery - Long-form conversations on product philosophy, AI strategy, and competitive reality

- Gartner Magic Quadrant for Collaborative Work Management - A third-party view of the category, the contenders, and how analysts frame the market

- "The SaaS Metrics That Matter" - Bessemer Venture Partners - A useful framework for making sense of unit economics and SaaS performance

- "Seven Powers" - Hamilton Helmer - The competitive strategy lens used in the analysis

- "Crossing the Chasm" - Geoffrey Moore - Essential for understanding how bottoms-up adoption can (or can’t) turn into enterprise standardization

Key Books Referenced:

- Seven Powers - Hamilton Helmer

- The Innovator's Dilemma - Clayton Christensen

- Good Strategy Bad Strategy - Richard Rumelt

- Crossing the Chasm - Geoffrey Moore

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music