Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals: From the RNA Revolution to the Precision Medicine Era

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

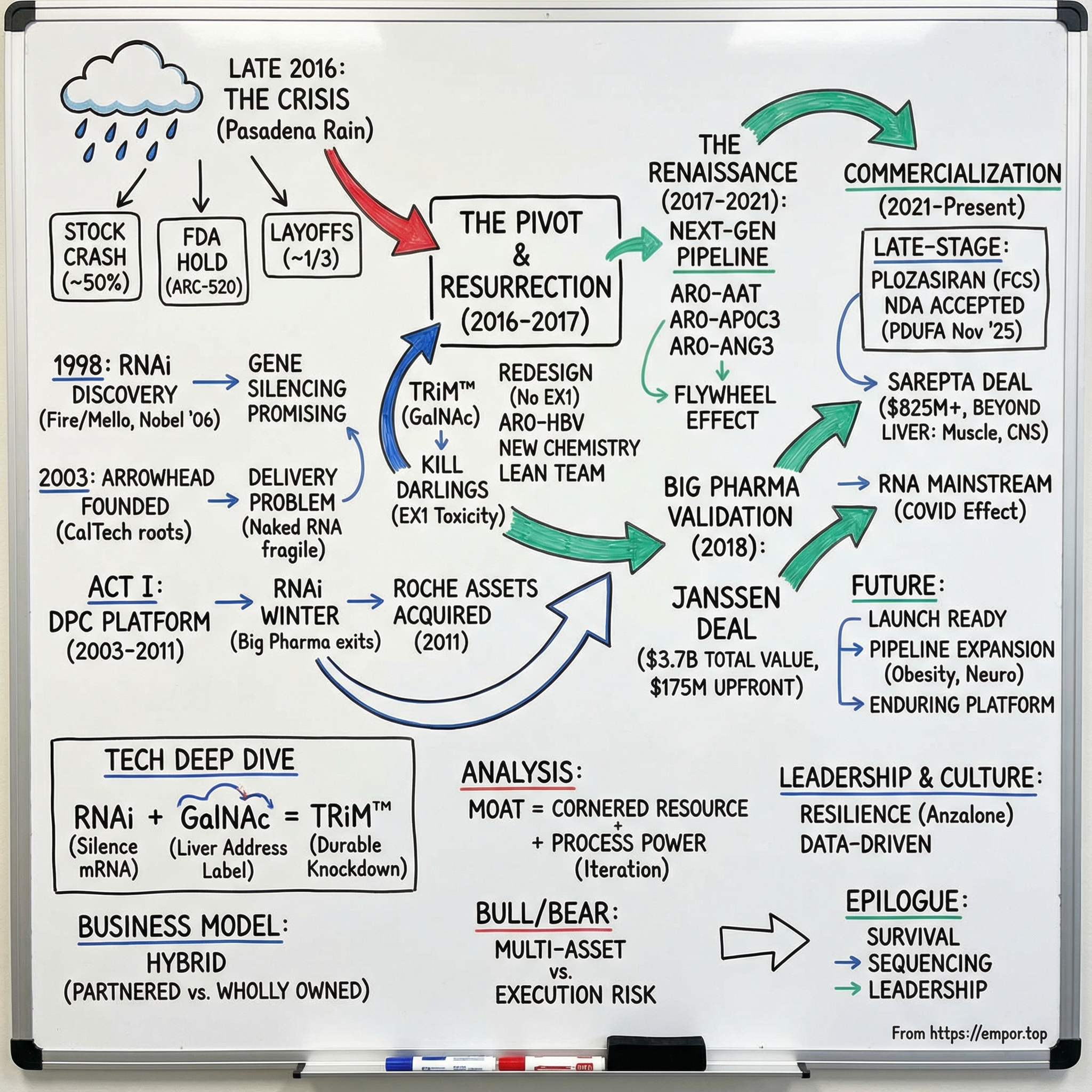

Picture a rain-lashed conference room in Pasadena in late 2016. Arrowhead’s stock has just been cut nearly in half. A toxicology study in non-human primates has gone horribly wrong. The FDA has stepped in with a clinical hold on the company’s lead program. Layoffs are imminent—almost a third of the team. The market is treating Arrowhead like it might not make it.

Fast-forward eight years and the plot flips. That same company is gearing up for its first commercial launch, stacking up partnerships measured in billions, and—most importantly—proving that the comeback story in biotech isn’t always a myth.

Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals, Inc. is a publicly traded biopharmaceutical company based in Pasadena, California. Its pipeline is built on RNA interference, or RNAi: medicines designed to turn down the production of specific proteins by silencing the genetic messages that create them. In practice, that focus has centered on hepatitis B, liver disease tied to alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency, and cardiovascular disease.

So the hook is straightforward: how did a small biotech born out of CalTech science survive multiple near-death experiences—and come out the other side as a credible leader in genetic medicines? This isn’t an overnight success story. It’s a grinding, iterative one, defined by scientific pivots, strategic reinvention, and the willingness to abandon years of work when the data demands it.

As of December 2025, Arrowhead trades with a market cap of $9.25 billion, an enterprise value of $8.70 billion, and roughly $829 million in trailing twelve-month revenue. The stock has been on a tear—up more than 200% over the past year—as investors start to price in a shift from development-stage biotech to a commercial enterprise.

And the bigger reason this matters is the RNA revolution itself. RNAi isn’t just another drug category. It changes the basic playbook. Instead of trying to block a problematic protein with a small molecule, or replace it with a biologic, RNAi aims one step earlier—silencing the gene’s output so the harmful protein never gets made in the first place. That’s precision medicine in its most direct form.

For investors, Arrowhead is also a case study in the platform model in biotech: build a core technology that can generate many drugs, not just one—and let each program make the next one faster, cheaper, and better. The promise is massive. The risk is existential. Arrowhead’s journey shows both.

II. The RNA Interference Revolution & Founding Context (2001-2003)

In early 1998, two American scientists, Andrew Fire and Craig Mello, published a Nature paper that quietly detonated a long-held assumption in biology: that genes were destiny unless you could somehow edit the DNA itself.

They showed something far more practical. If a cell encounters RNA in a double-stranded form, it treats it like a threat. That double-stranded RNA triggers a cellular cleanup crew that hunts down and destroys matching messenger RNA, the mRNA instructions a gene uses to make a protein. Remove the instructions, and the protein never gets built. In other words: you can silence a gene without changing the gene.

That mechanism became known as RNA interference, or RNAi. And it didn’t take the scientific world long to realize what it meant. Just eight years later, Fire and Mello received the 2006 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for the discovery—an unusually fast timeline in Nobel terms, and a signal that this wasn’t just another incremental advance.

RNAi was especially intoxicating to drug developers because it hinted at something close to universal reach. In principle, if you could design the right sequence, you could “turn down” almost any gene you wanted. Not just the small subset of targets that traditional small molecules can hit, and not only what antibodies can reach. The implication was enormous: diseases driven by proteins that were previously “undruggable” might suddenly be on the table.

So the gold rush began. In the early 2000s, startups formed to chase RNAi as a new therapeutic class—Alnylam in 2002, Sirna close behind—while big pharma wrote huge checks to buy its way into the future. Merck acquired Sirna for $1.1 billion in 2006. Roche built an internal RNAi effort valued at more than $1 billion. For a moment, it looked like the next great platform technology in medicine had arrived fully formed.

But there was a catch. A brutal one.

RNAi worked beautifully in controlled lab settings. Getting it to work inside the human body was a completely different game. “Naked” RNA is fragile; it gets chewed up quickly in the bloodstream. It doesn’t naturally slip into cells. And even when it does, it can trigger immune reactions that are anything but subtle. Delivery wasn’t a footnote. Delivery was the whole problem.

That’s where the company that would become Arrowhead enters the story.

Arrowhead’s corporate roots actually go back to 1989, when it was founded as Insert Therapeutics, Inc., focused on nanotechnology-based drug delivery systems. Long before RNAi became a buzzword, the company was already thinking about a question that would later define the entire field: how do you get a therapeutic payload to the right place, safely?

When RNAi exploded onto the scene, Arrowhead’s Pasadena orbit—connected to CalTech science through its subsidiary Calando Pharmaceuticals—was already working on delivery technologies aimed at making RNA-based medicines viable. Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals, Inc. was founded in 2003 and headquartered in Pasadena, California, with a thesis that was simple to say and brutally hard to execute: build delivery good enough that RNAi could actually work in humans.

The science wasn’t the debate. The biology had spoken. The open question—the one that would nearly wipe out the entire RNAi sector—was whether anyone could turn that elegant mechanism into a safe, repeatable drug. Arrowhead was betting its future that the answer was yes.

III. The First Act: DPC Platform & Early Struggles (2003-2011)

In the summer of 2007, Chris Anzalone got a call from Arrowhead Research Company. At the time, he was running the Bennet Group, a Washington, D.C.-based private equity firm that built nanobiotechnology companies out of university science. The conversation started like a deal discussion. Then Arrowhead changed the subject: they were looking for a new CEO. Would he consider it?

Anzalone didn’t sugarcoat what he saw. A couple of things stood out, he later recalled: the company was broken, and the business model was broken too. What it did have—what was actually interesting—was Calando Pharmaceuticals, a majority-owned subsidiary that was early to RNA interference.

With a Ph.D. in biology, Anzalone understood what RNAi could be if someone could make delivery work. So he laid out his terms: if he took the job, he wanted to sell off essentially everything else, keep Calando, and rebuild Arrowhead as a real biotech company around RNAi. Arrowhead agreed. He became CEO in December 2007.

The timing was brutal. Arrowhead was already public, and Anzalone felt he needed about a year of a healthy market to simplify the story and raise the right kind of capital. Instead, he got a quarter. By March 2008, the financial crisis hit, and capital-intensive companies with complicated narratives were exactly what investors wanted to avoid.

Arrowhead tried to find its footing anyway. In 2009, the company went public through a reverse merger, pushing forward in a world where biotech financing had tightened dramatically. The scientific bet in this era was the Dynamic PolyConjugates (DPC) platform—delivery technology meant to solve RNAi’s make-or-break problem. DPC used specialized peptides designed to escort RNA molecules into liver cells. In theory, that was the unlock: get the RNA where it needed to go, and gene silencing could finally become a drug.

In practice, the whole field was learning the hard way that “in theory” doesn’t get you through the FDA.

What followed became known as the RNAi winter. One by one, the giants that had piled into the space backed out. Roche shut down its roughly $1 billion RNAi effort. Novartis wound down. Pfizer, Merck, and others either exited entirely or cut their ambitions down to size.

It wasn’t just one problem. Delivery was still maddening. Early human programs raised safety concerns. Regulators got cautious. And the grand promise—drugging what had always been undruggable—turned out to be far harder than the early hype suggested.

Arrowhead’s own numbers told the story. When Anzalone first spoke with the company in 2007, the stock traded above $70 a share. By 2011, the market cap had fallen below $50 million.

This was the danger zone: dwindling cash, shaken confidence, and an industry graveyard forming all around them. Most observers would have bet Arrowhead would become another casualty.

Anzalone saw something else: opportunity in the wreckage. In 2011, as Roche looked to get out of the very business Arrowhead was trying to build, Big Pharma had a pile of RNAi assets—valued at around $1 billion—that it wanted off its hands. Arrowhead wasn’t the only bidder, and it was almost certainly the smallest and poorest.

But the logic was simple. Arrowhead still had Calando’s RNAi technology, yet Anzalone believed Roche’s assets were better. So he went after them.

That move—born out of a moment when Arrowhead could barely keep the lights on—set up the company’s next reinvention. But it also forced a painful reality: to survive, Arrowhead would have to question whether the very technology it was built on was the right foundation at all.

IV. The Great Pivot: Enter Targeted RNAi Molecule (TRiM™) Platform (2011-2013)

The Roche assets Arrowhead picked up in 2011 weren’t just a lifeline. They were a clue. But following that clue meant doing the thing most companies avoid until it’s too late: admitting the platform you’ve spent years building has hard limits.

That realization crystallized as more clinical data rolled in. Dynamic PolyConjugates were clever—but operationally clunky and increasingly risky. The approach relied on intravenous administration, which immediately narrowed the real-world usefulness of any future drug. Worse, there were growing concerns around immunogenicity and other safety issues tied to the delivery system itself.

The escape hatch came from a simpler idea that the field was starting to rally around: GalNAc conjugates. Arrowhead’s next-generation delivery platform—Targeted RNAi Molecule, or TRiM—moved away from the older chemistry that depended on an active endosomal escape agent (PBAVE, melittin). Instead, TRiM leaned into direct conjugation: attach a GalNAc targeting domain right onto the siRNA.

The science was almost annoyingly elegant. N-acetylgalactosamine, GalNAc, is a sugar that binds tightly to a receptor called ASGPR that’s found in abundance on liver cells. As the commonly cited explanation goes: “The well-known method of targeting the liver is by using a synthetic triantennary N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) ligand. The GalNAc is designed to bind with high affinity and specificity to the asialoglycoprotein receptor (ASGPR) found in the liver. In short, the GalNAc ligand has become a very effective tool in delivering an RNAi trigger sequence to the liver.”

In plain English: GalNAc is like a liver address label. Put it on the RNA, and the drug naturally homes to hepatocytes. No complex delivery vehicle. No IV drip. Potentially, just a subcutaneous shot.

Arrowhead didn’t hedge. Facing the constraints of its earlier delivery technology, the company made a decisive shift to TRiM™ and rebranded as Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals. It was a strategic refocus that concentrated the entire organization around what looked like a cleaner, more scalable path forward—even though it required stopping prior programs that had consumed years of effort.

This was the “kill your darlings” moment. DPC wasn’t just a project. It was the identity of the company through the RNAi winter. Walking away meant writing off programs already in motion—and accepting that the sunk costs were sunk.

TRiM, by contrast, was built to be a platform you could iterate. It was designed for precise delivery of siRNA to specific tissues, with chemistry choices aimed at improving stability, reducing off-target effects, and driving more durable knockdown. Crucially, it was modular: different components could be swapped in and optimized depending on the target and the disease.

The reset was total. Arrowhead pivoted hard toward liver diseases and cardiometabolic targets—where GalNAc delivery had its strongest fit—and started the slow work of rebuilding credibility with both investors and the broader scientific community.

And while Arrowhead was reinventing itself, the rest of the RNAi world was moving too. Alnylam, the category leader and Arrowhead’s most important comparator, was also advancing GalNAc-based delivery. After years of false starts, that progress mattered. It suggested RNAi wasn’t broken; delivery had been.

The rivalry that followed wasn’t about whether GalNAc worked. It was about how well it could be engineered—and how each company chose to turn a delivery trick into a repeatable drug-making machine.

V. Building the Platform Company (2013-2016)

The TRiM pivot wasn’t just a new chemistry set. It was Arrowhead deciding what kind of company it wanted to be. The strategy became explicit: stop trying to win on a single shot on goal, and start building a platform.

That distinction is everything in biotech. A one-drug company is a high-wire act—one clinical failure and the story can end. A platform company is trying to build a flywheel: multiple programs in motion at once, and every improvement in delivery, safety, and potency gets reused and compounded across the entire pipeline.

With that mindset, Arrowhead’s target selection snapped into focus. Don’t start with the most speculative biology. Go where the causal link is clean, the genetics are understood, and silencing one specific gene has a real chance of translating into a meaningful clinical benefit.

The early flagship was ARC-520 for chronic hepatitis B virus, or HBV. Hepatitis B is a huge global burden, affecting more than 250 million people worldwide. Existing therapies can suppress the virus, but they generally don’t cure it. Arrowhead’s thesis for ARC-520 was simple and ambitious: knock down the viral signals—especially hepatitis B surface antigen—and you might give the immune system a chance to regain control.

Early clinical readouts gave Arrowhead something it badly needed: momentum that looked like biology working in people. As Bruce Given, M.D., Arrowhead’s chief operating officer and head of R&D, put it at the time: “Arrowhead’s ARC-520 and ARC-521 clinical studies have generated important data. We saw reductions in hepatitis B surface antigen, or HBsAg, of up to 3 logs following multiple doses with ARC-520 in combination with a NUC.”

At the same time, Arrowhead started laying the other foundation a platform company needs: partners. The reality was unavoidable. Moving from intriguing clinical data to a real commercial enterprise requires capital, regulatory experience, development muscle, and global reach—things a company of Arrowhead’s size couldn’t conjure overnight. Big Pharma validation wasn’t just about money. It was about legitimacy.

That validation arrived in September 2016, when Arrowhead signed two collaboration and licensing agreements with Amgen. Amgen received a worldwide exclusive license to Arrowhead’s ARO-LPA RNAi program, and an option to a worldwide exclusive license for ARO-AMG1—both aimed at cardiovascular disease.

Internally, the company was staffing up to match its ambition, recruiting experienced talent from places like Gilead, Amgen, and academia—people who had lived through what it takes to push programs from concept toward approval.

For a moment, the pieces looked like they were finally clicking into place.

And then—right as Arrowhead seemed to be finding its stride—disaster hit.

VI. Crisis and Resurrection: The ARC-520 Setback (2016-2017)

On November 8, 2016—the same day America went to the polls in one of the most consequential elections in modern history—Arrowhead dropped news that, for the company, was just as seismic.

The FDA placed a hold on Heparc-2004, Arrowhead’s Phase 2 trial of ARC-520 in chronic hepatitis B. The reason wasn’t a subtle signal in human data. It was far worse: deaths in non-human primates at the highest dose in an ongoing toxicology study tied to EX1, an intravenously administered delivery vehicle used across multiple Arrowhead programs—ARC-520, ARC-521, and ARC-AAT.

In biotech, this is the nightmare scenario. ARC-520 wasn’t just a lead program. It was the spearhead of the strategy Arrowhead had been selling to investors and partners. And EX1 wasn’t some minor component. It was the delivery system underpinning much of the company’s work at the time. Once the hold hit, the implications were immediate: programs built around EX1 were effectively on death watch.

The market reacted accordingly. The company’s valuation collapsed, and Arrowhead moved into survival mode. To extend its cash runway into 2019, management cut roughly 30% of the workforce—including clinical and R&D roles—exactly the people you need if you’re trying to fight your way out of a clinical crisis.

And the existential questions came roaring back. Was the platform flawed? Was RNAi still too dangerous or too unpredictable to be a real drug modality? Had Arrowhead spent years building on a foundation that couldn’t support a commercial company?

Arrowhead’s internal response became a forensic investigation. The painful irony was that the biology had looked real: ARC-520 had shown dramatic target impact, with biomarkers reduced by more than 99% in HBV patients after a single dose. But the primate toxicity results forced a hard stop anyway. One monkey death in long-term toxicity evaluation was enough to end the program. Two other DPC2.0-based siRNA therapies were discontinued as well. Arrowhead didn’t just pause; it amputated.

What mattered next was isolating the failure. If the problem was RNAi itself, the story was over. If it was a specific delivery component, the company might still have a path.

Arrowhead’s conclusion was that the likely culprit wasn’t the underlying RNAi mechanism, but the EX1 delivery component—the melittin-like peptide intended to help the siRNA escape cellular compartments. That distinction didn’t save ARC-520, ARC-521, or ARC-AAT as they existed. But it did something more important: it kept alive the idea that a redesigned approach—without EX1—could work.

On November 29, 2016, Arrowhead made it official: ARC-520 and ARC-521 were discontinued. But in the same breath, the company pointed to the escape route. It would continue developing ARO-HBV, a follow-on investigational RNAi therapeutic for chronic HBV using Arrowhead’s next-generation, proprietary subcutaneously administered delivery vehicle—TRiM.

The comeback plan was simple to describe and brutal to execute: redesign the molecules with next-generation chemistry, strip out the problematic components, restart the clinical engine, and rebuild trust with regulators, investors, and partners—all while running lean enough to survive.

Anzalone later pointed to a cultural tell that mattered in the darkest moments: when Arrowhead stabilized, it was able to hire back roughly 90% of the people it had laid off. “This was a real testament to those that stayed, and their being aligned on the mission,” he said.

He also set expectations with unusual bluntness. “We told the markets they weren't going to hear from us for about a year because we needed to focus and work as quickly as we could. Because if this ended up bleeding into two years, I was sure the company would die.”

Arrowhead didn’t die. By the end of 2017, the stock was beginning to recover. It closed 2018 at $12.42 per share, and by 2020, it was back in the $60s.

None of that was inevitable. Plenty of biotechs hit a clinical hold, lose their lead asset, slash headcount, and simply fade out. What separated Arrowhead was a rare combination: leadership willing to be direct about what had happened, a team that could diagnose the failure without hand-waving, and enough cash runway to actually execute a rebuild.

VII. The Renaissance: Next-Generation Pipeline Emerges (2017-2019)

Out of the wreckage of ARC-520 came something Arrowhead desperately needed: a next-generation hepatitis B program built on the cleaner, subcutaneous TRiM approach. That candidate was ARO-HBV, and it was designed with the lessons of the collapse baked in. “Building off of their prior RNAi clinical experience, ARO-HBV targets both the X gene and the S gene. Importantly, the X gene targeting sequence is present on all integrated forms of HBV, whereas the ARC-520 siRNAs did not. Using multiple sequence targets present on both cccDNA and integrated HBV, ARO-HBV reduces the opportunity for HBV to develop resistance.”

But the more important story wasn’t just that Arrowhead had a replacement for ARC-520. It was what happened next.

Once the company had a more reliable chemistry and a repeatable delivery playbook, the platform started doing what platforms are supposed to do: spin up new shots on goal, fast. ARO-AAT moved forward for alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. ARO-APOC3 targeted severe hypertriglyceridemia. ARO-ANG3 took aim at familial hypercholesterolemia.

You could see the flywheel turning. Same core idea—deliver siRNA into liver cells and silence the gene—applied again and again to new diseases. And every tweak that improved potency, durability, or safety in one program could be carried into the others.

The target selection wasn’t random, either. Arrowhead leaned into diseases where the biology was unusually direct—serious conditions where turning down one specific gene had a clear path to a meaningful benefit. Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency is a clean example: mutations can lead to misfolded protein piling up in the liver. Silence the defective gene, and you should reduce that toxic buildup. It’s a simple hypothesis, and it’s exactly the kind you want when you’re rebuilding credibility.

Then the data started arriving, and for the first time in years, Arrowhead wasn’t trying to convince the world with slides—it had proof points. Across multiple programs, the company showed deep, durable target knockdown with safety that looked workable. In a field that had spent a decade being told “delivery is impossible,” that mattered.

And the validation wasn’t just scientific. It was commercial.

“The collaboration agreement with Janssen for ARO-HBV marked a major inflection point. It provided substantial non-dilutive capital, offered external validation of the TRiM™ platform's potential from a major pharmaceutical player, and significantly de-risked the development pathway for a key asset.”

On Oct. 31, 2018, Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals Inc. closed on a $3.7 billion license and collaboration agreement with Janssen to develop and commercialize ARO-HBV.

This was when the narrative truly flipped. Arrowhead stopped looking like a wounded biotech that had survived a hold by sheer luck. It started looking like what it had been trying to become all along: a platform company with a technology that worked—and a Big Pharma partner willing to bet on it.

VIII. The Big Pharma Partnership Era (2018-2021)

The Janssen deal was transformational not just for its size, but for what it broadcast to the market: a major pharmaceutical company had done the diligence and decided Arrowhead’s platform was real.

“The transactions have a combined potential value of over $3.7 billion for Arrowhead. Under the terms of the agreement, Arrowhead will receive $175 million as an upfront payment.”

Arrowhead received that $175 million upfront, plus a $75 million equity investment from Janssen. The agreement also laid out a long runway of potential milestone payments, tiered royalties on commercial sales, and a key platform kicker: Janssen could opt in to developing up to three additional candidates built using Arrowhead’s Targeted RNAi Molecule (TRiM) platform, with additional milestones attached.

Just as important as the money was the division of labor. Beyond AROHBV1001—Arrowhead’s ongoing Phase 1/2 study of ARO-HBV—Janssen would take over full responsibility for clinical development and commercialization. And if Janssen chose new targets, Arrowhead would do what it did best: use TRiM to develop the clinical candidates that could become the next wave of partnered programs.

Arrowhead’s partnership philosophy during this era started to take a clear shape. This wasn’t “partner everything because we have to.” It was a portfolio strategy: keep some programs wholly owned where Arrowhead believed it could create outsized value, and partner the ones where the scale of development and commercialization would overwhelm a company of its size.

“The Janssen deal—and to a lesser extent a deal agreed with Amgen in 2016, to develop the RNAi therapy olpasiran, which involved a $35m upfront payment and a $21.5m equity investment, plus potential milestone payments of up to $400m—provided Arrowhead with the cash it needed not just to survive, but to flourish.”

By this point, Arrowhead wasn’t a single-asset comeback story anymore. “Today, the company is working on a pipeline of 15 assets,” largely focused on liver diseases—an unusually accessible organ for RNA delivery thanks to N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) siRNA conjugates—and also pushing into the lungs.

Then 2020 arrived, and with it, COVID-19—and an unexpected accelerant for the entire RNA therapeutics world. The rapid development of mRNA vaccines, a different technology but part of the same broader RNA revolution, put RNA-based medicine on the front page. Almost overnight, the idea that genetic information could be therapeutic stopped sounding like science fiction.

The distinction matters. mRNA vaccines tell cells to make a protein (like the spike protein) to train the immune system. RNAi does the opposite: it silences genetic messages so a harmful protein doesn’t get made. Different tools, different jobs—and ultimately more complementary than competitive.

But in markets, perception counts. The sector was re-rated. In investor minds, Arrowhead began shifting from “speculative biotech” to “credible platform company.” And with partnerships and capital behind it, the company had the funding—and the legitimacy—to push multiple programs forward at once.

IX. Road to Commercialization: Late-Stage Pipeline (2021-Present)

If the RNAi winter was Arrowhead’s test of survival, this next phase was its test of adulthood.

Going from “promising clinical-stage platform” to “commercial company” is one of the most dangerous crossings in biotech. It’s where great science gets humbled by manufacturing reality, regulatory nuance, commercial execution, and the unforgiving mechanics of reimbursement. Plenty of companies make it to late-stage data and still fail the landing.

Arrowhead’s first real shot at sticking that landing was plozasiran, formerly known as ARO-APOC3.

“Plozasiran, previously called ARO-APOC3, is a first-in-class investigational RNA interference (RNAi) therapeutic designed to reduce production of Apolipoprotein C-III (APOC3) which is a component of triglyceride rich lipoproteins (TRLs) and a key regulator of triglyceride metabolism. APOC3 increases triglyceride levels in the blood by inhibiting breakdown of TRLs by lipoprotein lipase and uptake of TRL remnants by hepatic receptors in the liver. The goal of treatment with plozasiran is to reduce the level of APOC3, thereby reducing triglycerides and restoring lipids to more normal levels.”

In other words: instead of trying to mop up triglycerides after the fact, plozasiran aims upstream—dialing down a key regulator that keeps triglycerides elevated.

The company built a full Phase 3 program around it. “The PALISADE study is a Phase 3 placebo controlled study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of plozasiran in adults with genetically confirmed or clinically diagnosed FCS. The primary endpoint of the study is percent change from baseline in fasting TG versus placebo at Month 10. A total of 75 subjects distributed across 39 different sites in 18 countries were randomized to receive 25 mg plozasiran, 50 mg plozasiran, or matching placebo once every three months.”

Then came the moment that separates “late-stage” from “real”: the FDA accepted the New Drug Application.

“Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals, Inc. today announced that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has accepted the New Drug Application (NDA) for investigational plozasiran for the treatment of familial chylomicronemia syndrome (FCS), a severe and rare genetic disease. The FDA provided a Prescription Drug User Fee Act (PDUFA) action date of November 18, 2025, and indicated it is not currently planning to hold an advisory committee meeting.”

And the regulatory momentum didn’t stop there.

“Plozasiran in the treatment of patients with FCS has been granted Breakthrough Therapy Designation, Orphan Drug Designation, and Fast Track Designation by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and Orphan Drug Designation by the European Medicines Agency.”

The clinical results also got a marquee stage—presented at major cardiology meetings and published in top-tier journals.

“The efficacy and safety results from the PALISADE study were presented at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions 2024 (AHA24) and simultaneously published in Circulation and presented at the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Congress 2024 and simultaneously published in The New England Journal of Medicine.”

But what made this feel like more than a one-product story was what sat behind it. Arrowhead wasn’t betting the company on a single molecule anymore; it was trying to prove a repeatable machine.

The company put it plainly: “Zodasiran is the fourth investigational RNAi-based candidate developed by Arrowhead to reach late-stage pivotal studies, after investigational drugs plozasiran, fazirsiran (licensed to Takeda) and olpasiran (licensed to Amgen).”

And then, in late 2024, Arrowhead announced a partnership that signaled something bigger than another licensing deal. It was a vote of confidence in the platform as a generator of multiple drugs across multiple tissues.

“Upon closing, Arrowhead will receive $825 million, consisting of $500 million cash and $325 million as an equity investment priced at a 35% premium.”

The scope was ambitious.

“Sarepta have entered into a discovery partnership pursuant to which Sarepta will nominate, and Arrowhead will deliver, IND-ready constructs for six targets across skeletal muscle, cardiac, and CNS.”

And the economics were designed to fund the next chapter—not just extend the current one.

“Arrowhead also receives $250 million to be paid in equal installments over five years and is eligible to receive an additional $300 million in near-term payments, which Arrowhead is on track to achieve during the next 12 months. Additionally, Arrowhead is eligible to receive royalties on commercial sales and up to approximately $10 billion in future potential milestone payments.”

Management tied it back to the core strategic goal: get to launch, and get there with enough capital to do it right.

“We estimate that this transaction extends Arrowhead's cash runway into 2028 and potentially through multiple new drug launches, including wholly owned and partnered programs. We now turn our focus as a company to launching investigational plozasiran for the treatment of familial chylomicronemia syndrome potentially in 2025, pending FDA review and approval, which would be our first commercial product.”

Underneath all of this is the broader evolution Arrowhead has been chasing for years: proving RNAi isn’t a liver-only trick, and proving the company can keep expanding what the platform can do.

“Unlike other RNAi companies, we are agnostic to the target tissue and are successfully advancing important medicines across a broad range of disease areas including of cardiometabolic, pulmonary, liver, and other diseases.”

X. The Science Deep Dive: How Arrowhead's Technology Actually Works

To understand why Arrowhead exists at all, you have to go back to the basic flow of biology. The so-called central dogma is the cell’s assembly line: DNA holds the blueprint, RNA carries the instructions, and proteins are the finished products. RNA interference plugs into that middle step. It’s a native cellular mechanism—one that likely evolved as a defense against viruses—that can selectively destroy a specific messenger RNA before it ever becomes protein.

That’s the core of what Arrowhead is trying to harness.

"Arrowhead therapies trigger the RNA interference mechanism to induce rapid, deep and durable suppression of target genes. RNAi is a mechanism present in living cells that inhibits the expression of a specific gene, thereby affecting the production of a specific protein. Arrowhead's RNAi-based therapeutics leverage this natural pathway of gene silencing."

The elegance of RNAi is also what makes it so unforgiving: if you can’t deliver the payload to the right cells, you don’t have a drug. “Naked” siRNA doesn’t survive long in the bloodstream. It can be degraded by enzymes, it doesn’t easily cross cell membranes, and if it ends up in the wrong places it can provoke immune responses. For most of the industry’s first decade, delivery wasn’t a technical detail—it was the whole game.

This is where GalNAc shows up as the field’s breakthrough. It’s a liver-targeting ligand that acts like an address label for hepatocytes, binding to the asialoglycoprotein receptor (ASGPR) found in abundance on liver cells.

"The well-known method of targeting the liver is by using a synthetic triantennary N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) ligand. The GalNAc is designed to bind with high affinity and specificity to the asialoglycoprotein receptor (ASGPR) found in the liver. In short, the GalNAc ligand has become a very effective tool in delivering an RNAi trigger sequence to the liver."

Once you can reliably get siRNA into the liver, you get a rare combination in drug development: long durability with short systemic exposure.

"The process is quick and efficient and has shown to provide incredible results, as once the trigger sequence is delivered to the liver, its biological effects of knocking down specific genes can last for over 3 months, but its plasma half-life is such that the drug gets eliminated from the bloodstream within approximately 24 hours. This is a big win for the present state of RNAi platforms with regards to safety, as most safety issues arise while the drug remains in the bloodstream."

Arrowhead’s TRiM platform is built around that idea: keep the construct structurally simple, use ligand-mediated delivery for tissue targeting, and keep iterating until the effect is both potent and predictable—with an eye toward expanding beyond the liver over time.

"Arrowhead's TRiM platform is focused on ligand mediated delivery, tissue specific targeting, and structural simplicity, plus the ability to reach beyond the liver and therefore target a wider range of diseases. Many observers believe TRiM is the best RNA platform available for drug developers, despite the long wait for a first commercialized asset—and in fairness to Arrowhead, attracting the likes of GSK, Janssen, Amgen, Horizon and Takeda suggests that the pharmaceutical world shares that sentiment."

One of the easiest ways to feel what “durable” means is to look at downstream clinical readouts, where a short dosing schedule can still translate into sustained biological impact.

"Mean reductions from baseline in triglycerides of up to -73% in patients from MUIR and -86% in patients from SHASTA-2 with favorable reductions in remnant cholesterol and non-HDL-cholesterol were observed through 15 months follow up in the open-label extension."

Of course, there’s a catch—at least for now. GalNAc is an elite solution for liver delivery. It doesn’t automatically solve delivery everywhere else.

"The GalNAc is currently actively being used by a number of RNAi companies, including competing RNAi drugs that are designed to treat HBV and Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. Identifying extrahepatic targeting ligands to target other tissues outside of the liver is the next big challenge RNAi companies are facing."

Arrowhead has made it clear it’s aiming to push past that boundary.

"Arrowhead's TRiMTM platform, by contrast, is designed to transcend organ-specific constraints."

And then there’s the unglamorous part that decides whether a great drug can actually become a great business: manufacturing. One of the underappreciated advantages of the GalNAc-siRNA approach is that these molecules can be made through chemical synthesis rather than grown in living cells like many biologics. That tends to mean more predictable production, clearer scalability, and potentially lower cost of goods—exactly the kind of operational leverage you want if you’re trying to go from a handful of clinical programs to multiple commercial launches.

XI. The Competitive Landscape & Market Dynamics

If Arrowhead is the comeback story, Alnylam Pharmaceuticals is the incumbent. It’s the 800-pound gorilla of RNAi—founded in 2002, based in Cambridge, and years ahead on the hardest thing in biotech: actually getting drugs approved and adopted.

Alnylam’s edge has been execution plus platform: its enhanced stabilization chemistry (ESC) approach uses chemical modifications to make siRNA molecules more stable and less prone to degradation in the body, paired with conjugate delivery to get those molecules into the right cells. And by 2025, the financial results reflected what “first to market” can look like at scale. Revenue jumped sharply year-over-year, and the company was operating from a position Arrowhead was still working toward: multiple commercial products, a trained sales force, and deep relationships with prescribers.

Regulatory wins reinforced that lead. In March 2025, the FDA approved Alnylam’s vutrisiran for transthyretin amyloidosis with cardiomyopathy, a high-profile decision that strengthened Alnylam’s position as one of the most valuable players in the sector. Management also projected Amvuttra and Onpattro would generate roughly $1.6 billion to $1.7 billion in combined annual revenue, up from a little over $1.2 billion the prior year.

So where does Arrowhead fit when the category leader is already this far down the road?

Arrowhead’s differentiation starts with its own chemistry and design philosophy. As the company has noted, “While the exact nature of the TRiM siRNAs has not been made public, Arrowhead reports that numerous tailor design chemistries have been incorporated to generate highly robust RNAi triggers.” The point isn’t that Arrowhead “does RNAi too.” It’s that Arrowhead believes it can produce highly potent, durable molecules through a modular platform—then apply those learnings across a pipeline instead of betting everything on one product.

The competitive dynamics in RNAi are also more “multiple winners” than winner-take-all. There’s room for different companies to win in different diseases, because the market is segmented by target biology, delivery fit, and clinical endpoints. But first-mover advantage still matters—a lot—especially in rare diseases where the patient populations are small and trust with physicians and treatment centers can become a moat.

And Arrowhead isn’t only competing with Alnylam. Dicerna Pharmaceuticals, founded in 2006, was acquired and is now a subsidiary of Novo Nordisk. Dicerna built its own GalNAc-conjugate approach, GalXC, designed to deliver RNAi triggers to the liver. Other players include Silence Therapeutics, plus various programs inside large pharmaceutical companies. Then there’s Ionis Pharmaceuticals, which is adjacent but different—focused on antisense technology rather than RNAi.

On pricing and market dynamics, RNAi has a structural advantage: these drugs often go after serious conditions with limited alternatives, and that can support premium pricing. One example cited in the market is pricing around $476,000 annually for cardiomyopathy, with growing use as a first-line therapy.

The looming threat—and the perpetual “what if?”—is gene editing, particularly CRISPR, which aims to make permanent changes instead of temporarily dialing gene expression up or down. That permanence can be compelling, but it cuts both ways. RNAi’s big counterargument is reversibility: if something unexpected happens, you can stop dosing and, over time, the effect fades. For many diseases, that flexibility is a feature, not a bug—and it’s part of why RNAi remains a distinct and durable competitor in the broader genetic medicines revolution.

XII. Business Model & Unit Economics

Arrowhead runs a hybrid model: keep the programs it believes it can build into meaningful standalone products, and partner the rest to bring in non-dilutive capital—upfront payments, milestones, and royalties—while Big Pharma carries much of the late-stage and commercial load.

"For fiscal year 2024, Arrowhead reported total revenues of approximately $232.5 million, derived almost entirely from these collaborations. The company focuses heavily on R&D, incurring expenses of around $411.9 million in FY2024, while often outsourcing manufacturing aspects, particularly for later-stage clinical supply and commercial scale-up."

Then fiscal 2025 changed the optics fast. "Revenue surged to $829.4 million from just $3.6 million in fiscal 2024, largely driven by milestone payments and deal-related income, plus the early transition to commercial operations. Operating income swung from a $601 million loss to a $98 million profit. Net loss attributable to Arrowhead shareholders narrowed to roughly $1.6 million, essentially breakeven on a GAAP basis, versus a $599 million loss a year earlier."

And it wasn’t just the income statement. "Total cash and investments (cash, equivalents and marketable securities) climbed to around $782 million, giving the company a healthy war chest heading into 2026."

But there’s an important nuance here: partnership revenue is real, but it’s not smooth. It comes in bursts when milestones hit, not as steady, predictable cash flow. That’s why plozasiran matters so much. If it converts from “late-stage asset” into “product,” Arrowhead’s business starts to shift from milestone-driven volatility toward recurring commercial revenue.

"Arrowhead is eligible to receive development milestone payments of between $700 million per program. Arrowhead is also eligible to receive tiered royalties on commercial sales up to the low double digits."

This is also where Arrowhead’s rare-disease strategy earns its keep. The company is leaning into the classic orphan-drug playbook: small patient populations, high unmet need, and regulatory advantages like orphan designation. Familial chylomicronemia syndrome affects only a few thousand patients in the U.S., but rare-disease pricing can still translate into meaningful revenue if a drug becomes standard of care.

Over time, the durable profitability story is meant to come from multiple lanes at once: product revenue from wholly owned drugs like plozasiran, milestone payments as partnered programs move through the clinic, manufacturing services revenue from supplying partners, and royalties if partnered drugs reach the market and scale.

XIII. Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: Moderate-High

The barriers here are real—but they’re not walls. Building an RNAi platform takes deep scientific talent, hard-won expertise in delivery chemistry, and the kind of capital that can carry multiple clinical programs at once. Just as importantly, it takes regulatory scar tissue: you learn what the FDA wants by living through what it doesn’t.

But the field isn’t closed. Academic labs keep producing new delivery ideas, and well-funded startups can often license core IP and recruit experienced teams. And after COVID made “RNA as medicine” feel mainstream, more capital and talent flowed into the broader RNA therapeutics universe—meaning the next challenger could come from anywhere.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Low-Medium

siRNA manufacturing is specialized, but it’s no longer exotic. The CDMO market has matured, giving companies more choices and reducing the odds that any single vendor can dictate terms. Arrowhead has also been building internal manufacturing capability while keeping outside partners in the mix—essentially buying flexibility and leverage at the same time.

Inputs like GalNAc ligands and siRNA synthesis reagents still require expertise, but they’re available from multiple sources. The more Arrowhead brings in-house, the less any supplier can squeeze it.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: Low-Medium

In rare disease, buyers have less leverage than people assume. If you’re treating a condition like FCS and there are few real alternatives, payers face both medical and reputational pressure to cover an effective therapy. Physicians, meanwhile, mostly follow the data—especially when the patient populations are small and the disease burden is severe.

That dynamic changes as you move into big, competitive categories like cardiovascular disease. There, payer negotiation matters, and reimbursement starts to hinge on outcomes evidence in the real world. For broad populations, “it works” isn’t enough—you have to prove it’s worth it.

Threat of Substitutes: Medium-High

RNAi doesn’t compete in a vacuum. Gene editing approaches like CRISPR promise permanence. Small molecules and biologics keep getting better. And in cardiometabolic disease, standard-of-care therapies—from statins to newer agents like PCSK9 inhibitors—already have entrenched mindshare.

Still, RNAi occupies a distinctive slot: precise gene silencing that’s durable for months, yet reversible. For some patients, that’s a compelling trade—less frequent dosing than daily pills, without committing to a permanent genetic change.

Industry Rivalry: High

This is a knife fight. Companies compete for targets, talent, trial sites, and partnerships—and the leader, Alnylam, has the advantage that matters most in biotech: approved products and commercial infrastructure already in the field. Others are pushing fast in overlapping indications, trying to arrive first or at least not arrive late.

Then there’s the legal layer. IP disputes and freedom-to-operate questions are part of the terrain here; the Arrowhead-Ionis litigation is a reminder that RNA isn’t just a scientific race, it’s a patent race too.

Even so, the prize is big enough that it doesn’t have to be winner-take-all. Different companies can win in different organs, targets, and patient segments—especially as delivery expands beyond the liver and the map of “druggable” genes keeps growing.

XIV. Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: Moderate

Arrowhead gets real scale benefits from being a platform: the expensive work—chemistry, delivery optimization, toxicology playbooks, regulatory learning—can be reused across many programs. Manufacturing scale should also improve as the company moves from clinical batches toward commercial supply. But this isn’t traditional pharma scale, where a massive sales force and global distribution network create towering, self-reinforcing advantages.

Network Economics: Low

This isn’t a network business in the classic sense; one more “user” doesn’t make the product inherently more valuable. Still, there’s a soft, indirect flywheel through partnerships: strong data and credible execution attract partners, partners bring capital and validation, and that makes it easier to recruit talent and fund the next wave of programs.

Counter-Positioning: Moderate-High

Arrowhead committed to RNAi through periods when big pharma was skeptical—or actively retreating. That matters because large organizations can’t simply flip a switch and rebuild what they dismantled. Once teams disperse and institutional knowledge evaporates, restarting is slow, expensive, and culturally hard to sustain.

Now, many of those same large companies are coming back via partnerships. In effect, they’re conceding that nimble biotechs can build platform capabilities that are difficult to recreate inside a legacy organization.

Switching Costs: High (once approved)

Once a patient is stable on an effective therapy, switching is unattractive—especially in chronic conditions. Physicians also develop habits: dosing cadence, monitoring routines, side-effect expectations, and the practicalities of patient support programs. Layer in prior authorization and reimbursement pathways, and the friction compounds. After approval, incumbency is a real advantage.

Branding: Low-Moderate

Arrowhead isn’t consumer-facing, so brand doesn’t work here the way it does for a household-name drug company. But reputation still matters—hugely—with physicians, payers, regulators, and especially partners. In this world, “brand” is shorthand for credibility: does the company’s science hold up, and does it execute?

Cornered Resource: High

Arrowhead’s biggest “owned” asset is its proprietary TRiM™ platform and the know-how around how to design, build, and deliver RNAi therapeutics. The company positions TRiM as a foundation for targeted delivery beyond the liver, including tissues like the lungs, muscle, and tumors, with the goal of improving stability and reducing off-target effects.

Layer on patents, trade secrets, and the hard-earned institutional knowledge accumulated over decades, and you get something that can’t be copied quickly. Add in first-mover advantages in specific targets, and the cornered resource case strengthens.

Process Power: High

If cornered resource is what Arrowhead owns, process power is what Arrowhead has learned. Years of iteration—improving delivery, managing immunogenicity risk, tightening clinical development strategy, and learning the regulatory path—create compounding benefits. Every program feeds the next with better design instincts and cleaner execution.

This may be the most durable advantage of all, because it’s not something a competitor can buy off the shelf. It shows up in the day-to-day realities that decide outcomes: smarter candidates, fewer surprises, and a tighter loop from data to next-generation design.

Overall Assessment: Arrowhead’s moat is primarily Cornered Resource (platform IP and accumulated know-how) plus Process Power (years of iterative learning). Counter-Positioning—built by staying committed when big pharma stepped back—adds another layer. And as clinical validation grows and the company moves closer to commercialization, these advantages have the chance to harden from “promising” into “proven.”

XV. Bull vs. Bear Case

Bull Case:

The bull thesis starts with a simple claim: Arrowhead isn’t a one-asset story anymore. The platform has produced multiple clinical programs, across multiple diseases, with partners who’ve had every incentive to diligence it hard before writing checks. As CEO Christopher Anzalone put it: “‘During the recent period, Arrowhead signed and closed a potentially transformational licensing and collaboration agreement with Sarepta Therapeutics and submitted our first NDA for investigational plozasiran, which was subsequently accepted for filing by the U.S. FDA. The company is now well positioned for growth with plans for an independent commercial launch in 2025 and the potential for multiple partner launches over the coming few years.’”

That matters because a deep pipeline gives you what biotech rarely offers: more than one way to win. Any single program can still disappoint, but the company doesn’t live or die on one binary outcome the way it once did. And the partnership model helps smooth the journey—non-dilutive capital comes in while Arrowhead keeps meaningful upside in the programs it chooses to own.

The near-term bull catalyst is clear: plozasiran is approaching the market, and it already carries Breakthrough Therapy Designation—exactly the kind of regulatory signal that can compress timelines and increase confidence.

In other recent news, Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals has launched Redemplo for Familial Chylomicronemia Syndrome (FCS), with projections from Piper Sandler estimating U.S. sales to reach at least $625,000 in the fourth quarter of 2025 and $12.3 million in 2026. Piper Sandler has also raised its price target for Arrowhead to $100, citing the drug's superior attributes compared to existing treatments.

For investors and observers tracking Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals stock, several catalysts and milestones are likely to drive sentiment over the next 12–24 months: early launch metrics for REDEMPLO in FCS—patient uptake, payer coverage, persistence, and real‑world pancreatitis outcomes; Phase 3 readouts for plozasiran in SHTG (SHASTA‑3/4) and any regulatory interactions enabled by Breakthrough Therapy status.

Step back, and the broader tailwind is the category itself. RNAi keeps moving from “novel” to “normal,” and as the market expands, it doesn’t have to be winner-take-all for Arrowhead to build a meaningful business. Layer in a management team that has already navigated multiple crises, plus a balance sheet strengthened by partnerships, and the bull view is that Arrowhead now has both the technology and the time to convert late-stage assets into durable product revenue.

Bear Case:

The bear thesis begins with the most obvious counterweight: Alnylam is still the incumbent, with multiple approved products and real commercial infrastructure—teams, relationships, and muscle memory that Arrowhead hasn’t yet proven it can build. As one snapshot puts it: “Alnylam dominates RNAi therapeutics with GalNAc-based liver-targeted therapies, generating $469M revenue in Q1 2025 via TTR franchise and AMVUTTRA® launch.”

Then there’s the evergreen risk in biotech: clinical programs can fail at any stage, including Phase 3. Even if the platform is sound, individual molecules can surprise you, and the market punishes surprises.

Commercial execution is its own separate cliff. Arrowhead has never had to run the full launch playbook—manufacturing readiness, payer contracting, patient services, field reimbursement support, and physician education—at real scale. In rare disease, one misstep can slow adoption quickly. In cardiometabolic disease, the bar is even higher, with entrenched competition from GLP-1 agonists, PCSK9 inhibitors, and other established therapies.

Pricing and reimbursement are another pressure point. High-cost rare disease drugs can face payer friction, and the evidence burden often shifts from “does it work?” to “does it prevent costly events in the real world?”

Legal uncertainty is also part of the backdrop. “Progress in the Ionis litigation and clarity on the FCS/SHTG intellectual‑property landscape.” IP overhangs don’t just add headline risk—they can complicate partnering, raise costs, and create timing uncertainty.

And while Arrowhead is trying to expand beyond the liver, the bear argument is that the platform remains most proven in hepatocytes, which constrains the addressable market until extrahepatic delivery is truly validated. One take captures the tension: “Arrowhead's TRiMTM platform offers broader tissue targeting (including lungs) but faces Q3 2025 net loss ($1.26/share) and revenue shortfalls despite long-term partnership-driven strategy.”

Finally, there’s macro risk. Biotech funding cycles can turn fast, and regulators continue to refine expectations for RNA-based medicines as safety databases grow. Even a strong company can get caught in the undertow of sector volatility.

XVI. Leadership & Culture

Christopher Anzalone has been Arrowhead’s president, CEO, and chairman for a long stretch of the company’s modern life. “Christopher Anzalone is the President, Chief Executive Officer, and Chairman of the Board of Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals. He attended the University of California.”

Before Arrowhead, he built his career at the intersection of science and capital—exactly the kind of background you want when you’re trying to turn difficult lab work into an investable, scalable business. “Prior to Benet, Dr. Anzalone was a partner at the Washington DC-based private equity firm Galway Partners, LLC. There, he was in charge of sourcing, structuring, and building new business ventures and was founding CEO of NanoInk, Inc., a leading nanolithography company. Dr. Anzalone holds a Ph.D. and M.A. in Biology from UCLA and a B.A. in Government from Lawrence University.”

That blend—deep technical training plus dealmaking instincts—helps explain how Arrowhead kept finding a way forward through repeated resets. When Arrowhead recruited him, it wasn’t subtle about the mandate.

“Arrowhead Research Corporation announced today the appointment of Dr. Christopher Anzalone as its new President and Chief Executive Officer effective December 1, 2007. Dr. Anzalone was also appointed to Arrowhead's Board of Directors on the same date. Concurrently, Arrowhead is beginning the process to acquire Benet Group LLC, a private equity firm founded and led by Dr. Anzalone as a vehicle to build new nanobiotechnology companies.”

From there, his tenure became defined by exactly the decisions that separate companies that survive from companies that vanish: killing programs that aren’t working, cutting headcount when the runway is at risk, pivoting platforms when the data demands it, and holding the team together long enough to rebuild. Arrowhead has had to do all of those—more than once.

As Arrowhead moved from survival to commercialization, it also started adding leadership experience that looks like the next phase of the journey: launches, scaling, and building a durable business. One clear signal was bringing in a proven operator from a company that has already run that playbook.

“Doug Ingram, president and CEO of Sarepta, will be appointed to the Arrowhead Board of Directors. He is an experienced biotech and pharma executive and has led Sarepta as they advanced multiple investigational medicines through the clinical and regulatory process, built a commercial organization from the ground up, launched multiple drugs, and moved the company toward profitability.”

On the scientific side, Arrowhead’s leadership bench has been shaped by the same logic as the platform itself: recruit experienced drug developers, keep the culture grounded in data, and treat failure as something to learn from quickly—not something to deny.

The company frames that culture explicitly in its own language: “As we look to the future, we continue to rely on the 10 fundamental Arrowhead Values that are the bedrock of our success, and we've embraced the bold goal of having 20 individual drugs, either partnered or wholly owned, in a clinical trial or on the market in 2025.”

XVII. What Comes Next: The Future of Arrowhead

From here, Arrowhead’s story is less about survival and more about sequencing—getting the next few moves right, in the right order, without stumbling on execution.

The near-term catalyst list is long, and it starts with the program that’s meant to turn Arrowhead into a real commercial company. As the company has said, “Phase 3 studies of plozasiran in severe hypertriglyceridemia are on pace to be fully enrolled in 2025 with potential study completion in 2026.” If plozasiran becomes a product and not just a clinical asset, Arrowhead’s business model shifts from milestone-driven bursts toward something steadier.

Behind that, the pipeline continues to widen in both ambition and tissue reach. The company has pointed investors toward “initial human data from ARO‑MAPT in Alzheimer’s disease, expected in the second half of 2026,” alongside “zodasiran’s YOSEMITE Phase 3 program in HoFH” and potential updates on “the dual-target ARO‑DIMER‑PA program.” The subtext is obvious: Arrowhead wants to prove it can keep generating late-stage candidates, not just shepherd one drug to the finish line.

But getting to that finish line comes with a new kind of risk. Building commercial infrastructure is a different sport than running clinical trials. Arrowhead has never launched a product before. Even in rare disease—where patient populations are small—the sales model is demanding: specialized physicians, concentrated treatment centers, and reimbursement that can make or break uptake. The science can be excellent, and the launch can still go sideways.

Then there’s the next frontier: pushing RNAi beyond the liver. Arrowhead has been explicit about wanting to expand into new tissues and new categories, and it’s already leaning into one of the most competitive spaces in all of pharma.

“A month after axing a Phase II cardiovascular candidate, Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals has placed a bullseye target on the obesity treatment space after it announced the advancement of two RNAi-based candidates to clinic. The US biotech said it plans to submit clinical trial regulatory applications for the two assets – named ARO-INHBE and ARO-ALK7 – by the end of this year, with the programmes slated to commence in early 2025.”

And the pitch is differentiation—not just joining the crowd.

“Arrowhead says preclinical trials have shown the two obesity candidates-in-waiting can reduce body weight and fat mass using a unique mechanism of action that may keep more lean muscle mass compared to currently approved obesity therapies.”

On the neuro side, Arrowhead has also started putting real stakes in the ground.

“Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals recently dosed the first subjects in a Phase 1/2a trial of ARO-MAPT, an RNAi therapy targeting tauopathies such as Alzheimer’s disease.”

All of that raises the obvious strategic question: does Arrowhead remain independent, or does it eventually get folded into a bigger platform? M&A possibilities exist in both directions. Arrowhead could be a compelling acquisition target for a large pharma company that wants RNA therapeutics capability with real clinical momentum. Or Arrowhead could decide to buy its way into complementary technology—either to accelerate extra-hepatic delivery or to broaden the set of diseases the platform can address.

However the chessboard shakes out, the long-term vision is consistent with the company’s trajectory since TRiM: become a sustained platform company with multiple marketed products across therapeutic areas—recurring revenue from products on one side, and a steady engine of new candidates on the other.

XVIII. Epilogue & Reflections

Arrowhead’s journey is a reminder that platform businesses in biotech demand an unusual mix of patience, capital, and resilience—enough to outlast the long stretch between “this works in a lab” and “this is a real product.” That is the desert in drug development, and most companies don’t make it across.

What separated Arrowhead wasn’t one magic breakthrough. It was a pattern of decisions and capabilities that showed up again and again. Leadership was willing to look at ugly data, say the quiet part out loud, and act on it—even when acting meant scrapping years of work. The scientific team could diagnose failures quickly and rebuild under extreme time pressure. Investors stayed in the story through multiple resets. And, crucially, Arrowhead’s platform thesis gave the company room to pivot without having to start from zero each time.

That last point is easy to underestimate until you’ve watched it happen. RNAi is unforgiving: chemistry, biology, manufacturing, and clinical development all have sharp edges, and you only learn how to handle them by getting cut. Arrowhead’s institutional knowledge—built over years, and protected through crisis—became one of its most valuable assets. The team didn’t just keep the lights on; it kept the learning intact.

And that learning compounded. Each clinical program fed data back into the next candidate. Each FDA interaction built a clearer playbook for what “good” looks like. Each manufacturing run improved the process. In a platform company, progress isn’t linear—it stacks.

The most striking part of Arrowhead’s story is how close it came to disappearing. The 2016 crisis put the company within sight of the cliff. That it survived and then regained momentum speaks to execution, timing, and yes, a meaningful dose of luck.

Why does any of this matter beyond Arrowhead? Because the pattern repeats across biotech. New modality. Early hype. Hard reality. A near-death moment. The pivot that either saves the company or finishes it. Then, if things go right, validation and growth. Arrowhead is a clean case study in how a platform biotech can navigate that arc and still emerge intact.

The RNA revolution is still unfolding. Arrowhead represents one model: a platform designed to generate multiple drug candidates off a shared technological foundation, financed in part by partnerships. Alnylam represents another: the pioneer that spent decades building a category and getting to multiple approvals first. Both paths can work. Neither is easy.

For long-term fundamental investors, the forward-looking scoreboard is simple:

-

Commercial execution on plozasiran: patient uptake, payer coverage, and real-world outcomes. This is the proof point that Arrowhead can transition from development-stage excellence to commercial execution.

-

Pipeline advancement: Phase 3 readouts in SHTG, progress in partnered programs, and the cadence of new IND filings. The platform thesis only holds if the engine keeps producing.

-

Partnership economics: milestone delivery and eventual royalty streams. These are the clearest signals that the platform has value beyond Arrowhead’s wholly owned launches.

Arrowhead’s story isn’t over. The hardest parts of “being a real company”—launch execution, competing with larger rivals, expanding beyond liver targeting—are still in front of it. But the story so far makes one thing hard to dismiss: with the right science, the right team, and the willingness to survive the parts that break most organizations, a small biotech can climb out of the crater and build something that looks like industry leadership.

XIX. Further Learning & Resources

Top Resources for Deeper Research:

-

Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals Investor Presentations & SEC Filings — Start here. The latest 10-Ks, 10-Qs, and corporate decks are where the company lays out its pipeline, partnerships, risks, and the financial plumbing that makes the whole strategy work.

-

Fire and Mello's original RNAi papers (Nature, 1998) — The origin story. If you want to understand why RNAi triggered a gold rush, read the paper that proved gene silencing could be programmable.

-

Clinical trial data on ClinicalTrials.gov — For the unfiltered source material: study designs, endpoints, inclusion criteria, and updates for programs like PALISADE, SHASTA, and MUIR.

-

Janssen (2018), Takeda (2020), Sarepta (2024) partnership agreements — Press releases and investor calls are the fastest way to understand how Arrowhead structures deals, what it keeps versus what it gives up, and why each partner signed on.

-

"The Gene: An Intimate History" by Siddhartha Mukherjee — Zoom out. It’s not about Arrowhead, but it’s one of the best frameworks for understanding how genetic medicine got here—and where it’s likely going.

-

FDA guidance documents on oligonucleotide therapeutics — Dry but important. These documents explain how regulators think about safety, manufacturing, and clinical evidence for RNA-based drugs.

-

Alnylam's journey and RNAi industry history — The competitive baseline. Arrowhead’s story makes more sense when you see how the category leader navigated delivery, approvals, and commercialization.

-

Biotech analyst reports from Jefferies, RBC Capital, Piper Sandler — Useful for triangulating market expectations, competitive positioning, and how Wall Street is modeling Arrowhead’s launch and pipeline.

-

Interviews with Christopher Anzalone — Podcasts and conference appearances offer the closest thing to a running commentary on Arrowhead’s strategy, pivots, and risk posture.

-

"The Billion Dollar Molecule" by Barry Werth — Not Arrowhead-specific, but a classic for understanding how biotech companies actually get built: long timelines, fragile narratives, and the constant tension between science and capital.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music