Arvinas: The Protein Degradation Revolution

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

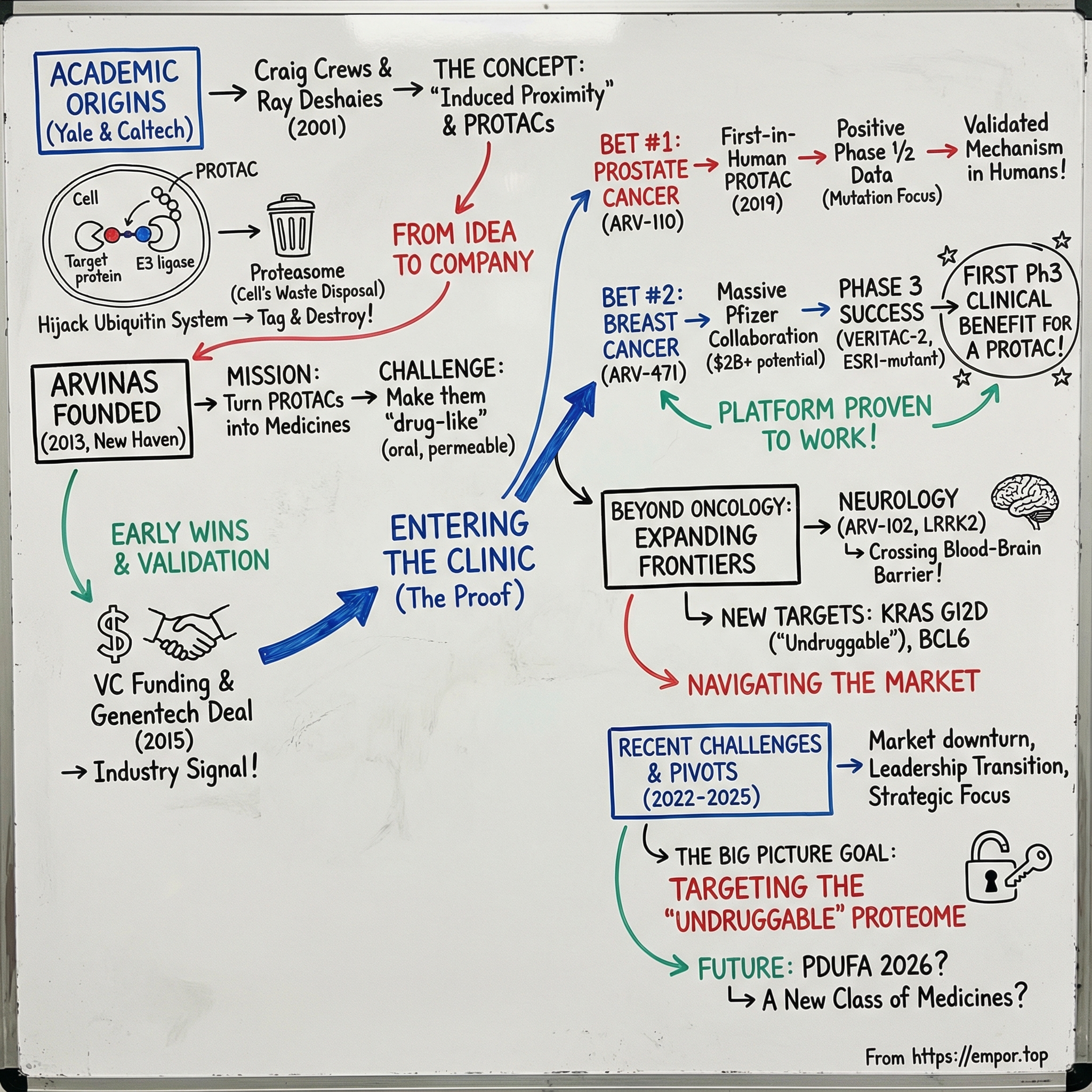

Picture a drug that doesn’t just block a disease-causing protein, but makes it vanish. Not by smashing it, but by tagging it—then handing it off to the cell’s own waste-disposal machinery to be shredded and recycled. That’s the provocative idea behind Arvinas and its PROTAC technology: a way to turn the cell’s existing cleanup system into a programmable medicine.

At the center of that story is Craig M. Crews, a Yale scientist born June 1, 1964. Over decades in chemical biology, Crews became known for a deceptively simple move: induced proximity. Instead of trying to “hit” a protein head-on, you bring two proteins together inside a living cell and let biology do the rest. That line of thinking led to heterobifunctional molecules designed to hijack cellular processes—and it helped spark an entirely new therapeutic modality. The company built to commercialize it, Arvinas, sits in New Haven, Connecticut, close to where the core science first took shape.

Arvinas was founded in 2013 by Crews. Its mission was straightforward to say and brutally hard to execute: turn PROTAC-based protein degradation into real medicines. Over time, the company evolved from a radical academic concept into a clinical-stage biotech with major pharmaceutical partnerships, late-stage clinical programs, and the claim that matters most in platform biotech: early clinical proof-of-concept for the PROTAC modality.

So here’s the central question: how did two academic scientists—one at Yale, one at Caltech—turn an insight about the cell’s garbage disposal system into what could become the next major drug class after antibodies and traditional small molecules? And now that targeted protein degradation has become a crowded, competitive race, can the pioneer stay out in front?

The stakes are enormous. Roughly 80% of the proteome has been considered “undruggable” with traditional approaches—and the promise of PROTACs is that much of that territory might finally be reachable. If Arvinas is right, this isn’t just a company story. It’s a story about expanding the entire map of what medicine can go after.

II. The Scientific Foundation: Why Proteins Matter & The Limits of Traditional Drugs

To see what makes Arvinas different, you first have to sit with the problem it’s trying to solve—and why, for decades, drug discovery kept running into the same wall.

Proteins are the cell’s doers. They speed up chemistry as enzymes, carry signals as hormones and receptors, provide structure, and—when it comes to antibodies—help defend you from the outside world. When the wrong proteins show up, show up in the wrong shape, or show up in the wrong amount, biology goes sideways. Tumors grow because growth signals won’t turn off. Neurodegenerative diseases worsen as misfolded proteins pile up. Chronic inflammation persists when signaling pathways won’t quiet down.

Historically, the pharmaceutical playbook has been straightforward: find the misbehaving protein and block it. Design a small molecule that binds to it and keeps it from doing its job—more like putting a boot on a car than removing the car from the road. This “occupancy-driven” approach has powered much of modern medicine, from aspirin’s effects on cyclooxygenase to targeted cancer drugs like Gleevec, which inhibits BCR-ABL in leukemia.

But inhibition comes with a built-in constraint: it only works while the drug is sitting on the protein. When the molecule falls off—or your body clears it—the protein can snap right back to work. And even worse, many of the proteins you’d most like to control don’t offer the kind of neat, pocket-like binding site that classic small molecules need. Transcription factors, scaffolding proteins, and big flat interaction surfaces can be essential to disease, yet effectively out of reach—part of what’s often described as the “undruggable” proteome.

Meanwhile, cells already have a far more decisive strategy for dealing with unwanted proteins: they don’t block them. They delete them.

The key mechanism is the ubiquitin-proteasome system, discovered in the late 1970s and early 1980s. It’s a selective tagging-and-disposal process: a small protein called ubiquitin is attached as a label to proteins the cell wants gone, and those tagged proteins are fed into the proteasome—often described as the cell’s “waste disposer”—where they’re broken down and recycled. The importance of this system was cemented when Aaron Ciechanover, Avram Hershko, and Irwin Rose received the 2004 Nobel Prize in Chemistry “for the discovery of ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation.”

What makes the system so powerful is that it isn’t random. It’s targeted. A typical mammalian cell has one or a few E1 enzymes, some tens of E2 enzymes, and several hundred different E3 enzymes—and it’s the E3 ligases that provide the specificity. They’re the matchmakers and the judges: they help determine which proteins get tagged for destruction.

Once you understand that, the next question almost asks itself: what if you could steer this machinery? What if you could point the cell at a disease-causing protein and say, “That one. Remove it.”

That’s the conceptual leap that becomes PROTAC technology. Instead of designing a molecule that only blocks a protein’s activity, you design a bifunctional molecule. One end binds the target protein. The other end recruits an E3 ligase. Bring the two into proximity, and you can “trick” the cell into tagging the target with ubiquitin—sending it to the proteasome for disposal.

And that leads to the distinction investors and scientists care about most: inhibition is occupancy-driven, but degradation is event-driven. A PROTAC doesn’t have to sit on the protein forever. It just has to bring the right two players together long enough for the cell to do the tagging. In principle, that means a single PROTAC molecule can act catalytically—helping eliminate one copy of the target protein, then moving on to the next because the PROTAC itself isn’t consumed in the process.

III. The Founding Insight: From Academic Discovery to Company Formation

Arvinas starts the way a lot of biotech revolutions start: not in a boardroom, but in two academic labs, with two scientists stubborn enough to keep pulling on an idea that didn’t fit the prevailing playbook.

Craig Crews had been on Yale’s faculty since 1995, building a reputation for using chemistry to manipulate biology inside living cells. By 2000, his lab had homed in on a deceptively ambitious goal: controlled proteostasis—methods for dialing protein levels up or down on command. Instead of merely slowing a protein’s activity, what if you could remove the protein from the system entirely?

The leap from “what if” to “we can” happened in 2001, when Crews teamed up with Raymond Joseph Deshaies (born September 25, 1961), then a professor at Caltech and an investigator at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Together, they introduced the core PROTAC idea: a single heterobifunctional molecule that can bind a target protein on one end and recruit a ubiquitin ligase on the other—setting up the target for proteasome-dependent destruction.

In other words, they weren’t trying to outcompete biology. They were trying to redirect it.

But proving a concept in a paper and building a drug are two very different jobs. The earliest PROTACs were peptide-based: big, awkward molecules that struggled to get into cells and weren’t practical as oral medicines. They showed the mechanism could work, while also making the technology feel, to many observers, like a clever academic trick rather than a viable therapeutic platform.

At the same time, the commercial environment wasn’t exactly inviting. This was the early 2000s, just after the post-genomic bubble had deflated, and investors had little appetite for unproven modalities—especially ones that, at the time, didn’t look “drug-like.”

Crews did have one critical advantage that many academic founders don’t: he’d already been through the company-building cycle once. In 2003, Deshaies co-founded Proteolix with Crews, Susan Molineaux, and Phil Whitcome, based on technology developed in the Crews and Deshaies labs. Proteolix advanced carfilzomib (Kyprolis) through mid-phase 2 clinical trials before Onyx acquired the company in 2009. Kyprolis, a proteasome inhibitor—different from targeted degradation, but still rooted in the protein homeostasis world—was later approved by the FDA in 2012 for multiple myeloma. That success didn’t solve the PROTAC problem, but it did establish that Crews could translate serious biology into real-world drug development.

For PROTACs themselves, the real unlock came years later. In the mid-2010s, researchers identified small-molecule binders for key E3 ligases—especially cereblon and VHL. Those ligase handles made it possible to build PROTACs that were far closer to what medicine demands: cell-permeable, orally feasible, and with pharmacokinetic properties that didn’t immediately disqualify them.

With that foundation finally firming up, Crews founded Arvinas in 2013 in New Haven, Connecticut, to turn PROTAC technology into drugs for cancer, neurodegeneration, and other diseases. The company spun out of his Yale lab with a small team—around 20 people at the start—and over time grew to roughly 450.

The early company architecture mattered as much as the science. Yale University licensed the PROTAC technology to Arvinas in 2013–14, granting an exclusive license to the foundational intellectual property. That IP position would become one of Arvinas’ most important long-term advantages: not just a scientific head start, but a defensible claim on the earliest, most enabling pieces of the platform.

To fund the leap from lab to clinic, the founding team brought in venture backing led by Canaan Partners and other investors who saw the bigger picture. This wasn’t a single drug story. If degradation worked the way Crews and Deshaies believed it could, it could be a platform—one capable of generating an entire pipeline, across multiple targets and therapeutic areas.

IV. Building the Platform: Technology Deep Dive & Early Validation

To appreciate why PROTACs matter, you have to understand what they actually do—and why that produces a kind of pharmacology traditional drugs can’t easily replicate.

“Think of the PROTAC molecule as a dumbbell with two large ends and a connector between them,” Crews explained. “One end binds to a part of the intracellular machinery responsible for degrading and eliminating proteins, the other end binds to whatever target protein is causing the disease you want to eliminate. So you are literally dragging this target protein to the quality control machinery and feeding it into the buzz saw.”

That “dumbbell” only works if all three parts work together: a binder for the target protein, a binder for an E3 ligase, and the linker that holds them at just the right distance and orientation. Change the linker length or chemistry and the whole geometry shifts. Pick a different E3 ligase binder and you’re recruiting a different piece of the cell’s destruction apparatus. And crucially, the target binder doesn’t need to shut the protein off the way an inhibitor does. It just needs to hold on long enough for the ligase to tag the target with ubiquitin.

Once that tag is in place, the cell takes over. The proteasome does the shredding, and the PROTAC itself isn’t consumed in the process. In principle, it can go back out and do it again—an iterative, “catalytic” loop where one molecule can trigger the degradation of multiple copies of the target protein.

That’s the big conceptual payoff: inhibitors have to sit on their target to keep working. PROTACs just have to create the event—bring the right proteins together, trigger tagging, and then move on. If the biology cooperates, that can mean lower doses, longer-lasting effects, and potentially a better therapeutic window.

But there was a brutal practical problem hanging over the whole modality: could you ever make these molecules into real drugs?

PROTACs are big by small-molecule standards—often in the 700 to 1,000 dalton range—and that puts them well outside the boundaries suggested by Lipinski’s “Rule of 5,” the decades-old rulebook for what tends to be orally bioavailable. For a long time, the knock against PROTACs was simple: even if the mechanism is beautiful, the molecules might never behave like medicines.

Arvinas pushed directly into that constraint. The company argued that you could develop a different set of design principles—its own internal “rules”—to build PROTACs that were not only potent and selective, but could actually be taken by mouth, and in some cases could even be engineered to cross the blood-brain barrier. Over time, Arvinas’ clinical-stage PROTACs did demonstrate oral dosing, clearing one of the most important hurdles the field had been staring at since the concept was born.

The earliest outside validation didn’t come from a flashy clinical result. It came from a deal.

In October 2015, Arvinas entered into a multi-year strategic license agreement with Genentech, a member of the Roche Group, to develop new therapeutics using Arvinas’ PROTAC technology across multiple disease targets. Arvinas received an undisclosed upfront payment and became eligible for development and commercialization milestone payments in excess of $300 million.

For Arvinas, this mattered far beyond the dollars. Genentech has a reputation for scientific rigor and a low tolerance for hype. If they were willing to put a collaboration behind protein degradation, that was a signal to the rest of the industry that PROTACs were moving from academic curiosity toward industrial-grade drug discovery. As James Sabry, M.D., Ph.D., Genentech’s Senior Vice President and Global Head of Partnering, put it: “Genentech is very interested in protein degradation as a therapeutic approach to address difficult disease targets. Arvinas's PROTAC technology offers an exciting opportunity to harness the body's own system to degrade pathogenic proteins.”

Two years later, in November 2017, the relationship deepened. Arvinas expanded its ongoing agreement with Genentech to encompass additional disease targets. Under the revised terms, Arvinas became eligible for development and commercialization milestone payments in excess of $650 million.

It wasn’t just a renewal. It was a vote of confidence—evidence that, inside the collaboration, the technology was doing what it was supposed to do. And for a young platform company, that kind of signal can be as valuable as any lab result: it tells the market that one of the toughest judges in biotech liked what it saw and wanted more.

V. Going Public & Choosing the Path Forward

By 2018, Arvinas had something most early biotechs would kill for: external validation from top-tier pharma. What it didn’t have yet was the one thing that changes everything—human data. No patients had taken an Arvinas drug. And getting from a promising platform to clinical proof takes an uncomfortable amount of cash.

That put the company at a fork in the road. Stay private and keep raising venture rounds? Or tap the public markets and build a balance sheet big enough to run multiple clinical programs at once?

Arvinas chose the public route. The New Haven-based company filed confidentially on June 22, 2018, and set out to list on Nasdaq under the ticker ARVN. At the time, it had recorded $12 million in revenue for the 12 months ended June 30, 2018—money largely tied to partnerships, not product sales.

On September 26, 2018, Arvinas priced its initial public offering: 7,500,000 shares at $16.00 per share, for gross proceeds of about $120 million before fees and expenses. The offering closed on October 1, 2018.

Pricing at the high end of the range mattered. This was still a preclinical story in the public market sense—no drugs in human testing yet—so investors weren’t underwriting results. They were underwriting a bet: that targeted protein degradation could become a repeatable engine for making medicines, not a one-off science project.

Ahead of that leap, Arvinas had also made a key leadership move. On September 20, 2017, the company appointed John Houston, Ph.D., as president and chief executive officer, with a seat on the board. He had joined earlier that year, in January 2017, as president of research and development and chief scientific officer.

Houston brought the kind of operating credibility that platform biotechs often need before the public markets will trust them with hundreds of millions of dollars. He had more than 28 years in the pharmaceutical industry, including 18 at Bristol-Myers Squibb in roles of increasing responsibility, and he’d been part of executive decision-making on major programs including Daklinza, Farxiga, Eliquis, Yervoy, Opdivo, and others.

That background shaped Arvinas’ strategy as it stepped onto Nasdaq: don’t choose between being a platform company and being a drug company. Be both. Build wholly owned programs—especially in oncology and neurology—while continuing to partner the PROTAC technology with large pharma for additional targets and non-dilutive capital. The logic was simple: spread the risk, let partners help fund the machine, and keep enough upside in-house that a single clinical win could transform the company.

VI. The Androgen Receptor Bet: ARV-110 & The Prostate Cancer Program

With capital secured, Arvinas now had to answer the only question that really counts in biotech: does this work in humans? To get that first proof, the company made a very deliberate choice for its lead target: the androgen receptor, or AR, in prostate cancer.

AR isn’t some speculative biology. It’s the engine that drives most prostate cancers. The standard drugs in advanced disease either lower androgen levels, like abiraterone, or block androgens from binding to AR, like enzalutamide. But a meaningful fraction of patients—roughly 15% to 25%—never respond to abiraterone or enzalutamide at all, due to intrinsic resistance. And even among responders, resistance frequently develops.

That’s what made AR such an attractive first bet. It was already validated by blockbuster medicines, yet it still left plenty of patients behind. Arvinas’ thesis was simple: if inhibition eventually fails, maybe degradation can change the game. If a PROTAC could remove the receptor itself, it might overcome some of the ways tumors adapt to AR blockers.

The program’s lead candidate was ARV-110, also known as bavdegalutamide. It became the first PROTAC protein degrader to enter human clinical trials, in a Phase 1/2 study for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. In 2019, PROTACs officially entered the clinic.

For the field, this was a landmark. Nearly two decades after Crews and Deshaies first laid out the concept on paper, a PROTAC was finally being tested in patients.

As the Phase 1/2 dose-escalation study progressed, Arvinas reported evidence of anti-tumor activity and patient benefit. In a molecularly defined patient population, the trial showed a prostate-specific antigen reduction of more than 50% (a PSA50 response) in 40% of patients.

But the signal wasn’t evenly spread across everyone in the trial. The activity clustered in patients whose tumors carried specific AR mutations. That finding reshaped the program’s strategy. Instead of aiming for a broad, one-size-fits-all label, Arvinas leaned into a precision-medicine approach: match the drug to the patients most likely to respond. The company planned to initiate a pivotal trial by the end of 2022 evaluating bavdegalutamide in patients with mCRPC who had progressed on or after novel hormonal agents and whose tumors harbored AR T878X/H875Y mutations.

In parallel, Arvinas advanced a second-generation AR degrader, ARV-766, designed to show broader activity across mutation types. Then, in May 2024, Arvinas out-licensed ARV-766 and sold its preclinical AR-V7 program to Novartis AG. Arvinas received a one-time upfront payment of $150 million and became eligible for up to an additional $1.01 billion in contingent development, regulatory, and commercial milestones.

The Novartis deal did two things at once. It validated the value of Arvinas’ AR work in the eyes of a major pharma buyer—and it gave Arvinas more flexibility to concentrate its time, capital, and attention on the programs it believed could define the company.

VII. Expanding the Pipeline: ARV-471 & The Breast Cancer Opportunity

If the prostate cancer program was the scientific spearhead—the first PROTAC to prove the concept in humans—Arvinas’ biggest commercial swing pointed at a different hormone receptor altogether: estrogen receptor (ER) in breast cancer.

About 80 percent of new breast cancer cases are positive for estrogen receptor alpha (ERα), a driver that helps tumors grow and survive. And the market is enormous. ER-positive disease is the most common breast cancer subtype, and combinations like endocrine therapy plus CDK4/6 inhibitors have become the backbone of treatment. The problem is familiar: over time, resistance shows up, and patients run out of good options.

That set the stage for ARV-471, later named vepdegestrant: an investigational, oral PROTAC estrogen receptor degrader being developed for ER+ locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer. In preclinical work, the drug showed potent ER degradation (DC50 = 1.8 nM).

Then came the moment that turned ARV-471 from “promising program” into “industry-wide validation.”

In July 2021, Arvinas and Pfizer announced a global collaboration to develop and commercialize ARV-471. Pfizer agreed to pay Arvinas $650 million upfront and, separately, to make a $350 million equity investment. The companies planned to equally share worldwide development costs, commercialization expenses, and profits. On top of that, Arvinas became eligible for up to $400 million in regulatory approval milestones and up to $1 billion in commercial milestones—pushing the headline potential value of the deal beyond $2 billion.

It was a clear signal: Pfizer—one of the biggest players in oncology, with deep experience in breast cancer through Ibrance—thought this degrader could matter.

With Pfizer beside them, the clinical plan got big fast. Vepdegestrant moved into Phase 3 as both a monotherapy and a combo backbone: as monotherapy in the second-line setting in the ongoing Phase 3 VERITAC-2 trial, and in the first-line setting combined with palbociclib in the ongoing study lead-in cohort of the Phase 3 VERITAC-3 trial.

In March 2025, VERITAC-2 delivered what the entire field had been waiting for. The trial achieved its primary endpoint in the estrogen receptor 1-mutant population, showing a statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in progression-free survival. At ASCO, the pivotal Phase 3 results showed a 2.9-month improvement in median progression-free survival versus fulvestrant in second line-plus patients with an ESR1 mutation. Vepdegestrant became the first PROTAC degrader to show Phase 3 clinical benefit.

But it wasn’t a clean, universal win. VERITAC-2 significantly improved progression-free survival compared to fulvestrant in patients with ESR1-mutant advanced or metastatic breast cancer, yet it did not reach statistical significance in the overall intent-to-treat population.

That split outcome mattered. It suggested vepdegestrant’s most likely path forward was a narrower label—aimed at patients whose tumors carry ESR1 mutations—rather than the broader ER+ population many had hoped for. Still, it was a meaningful commercial opportunity, and more importantly for Arvinas’ platform thesis, it was proof that PROTAC-driven degradation could translate into Phase 3 benefit.

Then the strategy shifted again. In September 2025, Arvinas and Pfizer jointly agreed to out-license the commercialization rights to vepdegestrant to a third party.

The move reflected a hard biotech truth: a narrower-than-hoped label can change the economics and enthusiasm for a massive commercial launch. For Arvinas, out-licensing also meant something else—more flexibility to redirect time, focus, and capital toward earlier-stage programs that could ultimately carry broader potential.

VIII. The Partnership Playbook: Building the Protein Degradation Ecosystem

From the start, Arvinas treated partnerships as more than fundraising. They were the company’s way of turning a bold platform claim into something the industry would actually believe—while also sharing the cost and risk of building drugs from scratch.

Genentech was the first major proof point. The relationship began in October 2015, when Genentech, a member of the Roche Group, signed on to develop new therapeutics using Arvinas’ PROTAC Discovery Engine. Then, in November 2017, the companies expanded the multi-year strategic license agreement to include additional disease targets. With that expansion, Arvinas became eligible for more than $650 million in development and commercialization milestones, plus tiered royalties if products made it to market.

The signal wasn’t subtle: one of the most scientifically demanding organizations in pharma wanted broader access to the platform.

Pfizer became the next marquee partner. In January 2018, Arvinas announced a research collaboration and license agreement with Pfizer Inc. The partnership also reflected Arvinas’ preferred structure when it wanted to keep meaningful upside: Arvinas and Pfizer would equally share worldwide development costs, commercialization expenses, and profits.

And Arvinas didn’t limit the idea of “protein degradation” to medicine. In 2019, Arvinas and Bayer formed Oerth Bio, a joint venture aimed at applying PROTAC-style technology to agriculture—weed, pest, and disease control. It was an unusually creative bet: if induced proximity can steer biology in human cells, why not try to steer it in plants too?

Over time, the partner list grew to include Pfizer Inc., Genentech, Inc., F. Hoffman-La Roche Ltd., Carrick Therapeutics Limited, and Bayer AG.

Stepping back, the partnership model served four jobs at once:

- Validation: if sophisticated pharma companies licensed the technology, the platform looked less like theory and more like reality

- Capital: upfront payments and milestones helped fund internal R&D without relying entirely on equity markets

- Risk distribution: partners absorbed much of the cost for the targets they chose to pursue

- Capability access: partners brought development and commercial scale Arvinas couldn’t easily build on its own

Put together, the disclosed deal values added up to more than $3 billion in potential milestones, plus royalties. For a modality that hadn’t existed as an actual drug not that long before, that was the industry placing a very large wager on the idea that making proteins disappear could become a repeatable way to make medicines.

IX. The Competitive Response & Platform Expansion

By 2020, Arvinas’ progress had helped turn targeted protein degradation from a niche scientific curiosity into one of the most crowded corners of biotech. Once the first clinical data started to land, the message to the market was simple: this might be real. And when something might be real in drug discovery, everyone shows up.

A wave of companies jumped into the race. Kymera was one of several biotechs pursuing protein-degrading medicines, alongside Arvinas, C4 Therapeutics, Nurix Therapeutics, Monte Rosa Therapeutics, and Lycia Therapeutics. And it wasn’t just startups. Large pharma began pushing their own programs forward too.

The modern era of rationally designed targeted protein degraders in humans effectively began in 2019, when two heterobifunctional degraders entered first-in-human trials: Arvinas’ ARV-110 (targeting the androgen receptor) and ARV-471 (targeting the estrogen receptor). From there, the field rapidly broadened. Degraders from Bristol Myers Squibb, Nurix Therapeutics, Kymera Therapeutics, Dialectic Therapeutics, Foghorn Therapeutics, and others followed into the clinic.

Before long, the list of meaningful players in targeted protein degradation read like a cross-section of global pharma and the biotech upstarts trying to become them: Bristol Myers Squibb, Arvinas, BeiGene, Nurix, Kymera, C4 Therapeutics, Stemline Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Bayer (Vividion), Captor Therapeutics, Ranok Therapeutics, Pfizer, Novartis, and Foghorn Therapeutics.

At the same time, “protein degradation” stopped meaning only PROTACs. The field expanded into molecular glues—a related strategy that traces back to the unexpected biology of thalidomide derivatives—and other degradation mechanisms that didn’t require the classic two-headed PROTAC architecture.

In a world where everyone is chasing the same promise, Arvinas’ defensive moat came down to a few core advantages. It was the pioneer, built on Yale-originated technology, and the first to bring a PROTAC degrader into the clinic. It had spent years turning the ubiquitin-proteasome system into a proprietary platform for selectively removing disease-causing proteins. And it had a pipeline that, for a time, defined the category: ARV-110 and ARV-471, aimed at the androgen and estrogen receptors in prostate and breast cancer.

But Arvinas also tried to widen the aperture beyond oncology. The company expanded into neurology, where one property matters almost more than anything else: the ability to cross the blood-brain barrier. That’s an area where small molecules can have a structural advantage over larger biologics, and Arvinas pointed to early clinical studies in neurodegenerative disease targets where its PROTACs demonstrated blood-brain barrier penetration—an essential prerequisite for any drug that hopes to treat the brain.

X. Recent Challenges & Strategic Pivots

The stretch from 2022 through 2024 tested Arvinas in the way biotech companies usually get tested: the market turned, expectations tightened, and the distance between “promising platform” and “reliable product engine” suddenly mattered a lot more.

Arvinas’ stock told that story in fast-forward. ARVN hit an all-time high of 108.47 on July 29, 2021. It later fell as low as 5.90 on May 15, 2025. That collapse—from triple digits to single digits—reflected the brutal biotech bear market, but also something more specific: investors had wanted vepdegestrant to be a broad winner, and the data ultimately pointed to a more targeted opportunity.

Even with the Phase 3 signal in the ESR1-mutant population, VERITAC-2 did not deliver the across-the-board outcome the market had been pricing in. And as the development plan for vepdegestrant evolved and Arvinas shifted its attention back toward earlier programs, the company moved to reshape its cost base to match the new reality.

Arvinas said it would take additional steps to streamline operations and optimize its organizational and cost structures. That included further limiting incremental spending on the vepdegestrant program and reducing its workforce by an additional 15%, with the largest cuts in roles tied to vepdegestrant commercialization.

Leadership was also in transition. New Haven-based Arvinas began a search for a new CEO after John Houston’s decision to retire as president and chief executive officer, which the company announced on July 9. Houston was set to remain chair of the board after his successor was appointed.

Through all of it, Arvinas held onto the one asset that buys time in biotech: cash. Under its operating plan, the company believed its cash, cash equivalents, and marketable securities as of December 31, 2024, would be sufficient to fund planned operating expenses and capital expenditures into 2027. As of that date, Arvinas reported $1,039.4 million in cash, cash equivalents, and marketable securities.

In a capital-scarce biotech market, that kind of runway isn’t just comfort. It’s leverage—the ability to keep running experiments, keep taking shots, and keep the platform thesis alive long enough to earn its next proof point.

XI. The Science Evolves: Next-Generation Degraders & Future Directions

While vepdegestrant moved through its next steps, Arvinas kept doing what a platform company has to do to stay credible: prove the modality can travel. Not just from one target to the next, but from one kind of biology to an entirely different one. And the most unforgiving proving ground for small molecules isn’t another tumor type. It’s the brain.

That’s where ARV-102 comes in. It’s an oral, brain-penetrant investigational PROTAC designed to degrade LRRK2—a large, multidomain scaffolding kinase. Increased activity, scaffolding, and expression of LRRK2 have been implicated in the pathogenesis of neurological diseases. LRRK2 mutations are a frequent familial cause of Parkinson’s disease, and common LRRK2 variants have also been linked with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease and progressive supranuclear palsy.

Arvinas presented data from two studies: ARV-102-101, a first-in-human trial in healthy volunteers, and ARV-102-103, a trial in patients with Parkinson’s disease. The topline story was encouraging on the three things you want to see early.

Safety: ARV-102 was generally well tolerated at single doses up to 200 mg and multiple daily doses up to 80 mg, with no discontinuations due to adverse events and no serious adverse events observed.

Pharmacokinetics: ARV-102 exposure increased in a dose-dependent manner in plasma and in CSF—an important signal that the drug was reaching the central nervous system.

Pharmacodynamics: Repeated daily doses of at least 20 mg produced deep target engagement, with more than 90% reductions of LRRK2 protein in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and more than 50% reductions in CSF.

That brain and CSF signal matters because it expands the addressable map for the entire modality. If PROTACs can reliably reach the central nervous system, the platform isn’t confined to oncology and peripheral targets—it can start to play in neurodegeneration, one of the largest and hardest categories in all of drug development.

Arvinas also shared data from preclinical combination studies of ARV-393, its investigational PROTAC B-cell lymphoma 6 protein (BCL6) degrader. BCL6 is a transcriptional repressor protein and a known driver of B-cell lymphomas. In high grade B-cell lymphoma and aggressive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma models, the company reported synergistic anti-tumor activity—including complete regressions—when ARV-393 was combined with standard of care chemotherapy, SOC biologics, and investigational oral small molecule inhibitors.

ARV-393 is being evaluated in a Phase 1 clinical trial in patients with relapsed/refractory non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and Arvinas said it planned to share clinical data from that trial at a medical congress in 2026. The company also planned to add a glofitamab combination cohort for patients with DLBCL to the ongoing Phase 1 trial in 2026.

Stepping back, this is what Arvinas looked like in its next chapter: not a one-asset story, but a portfolio of degraders advancing in parallel. The company was progressing multiple investigational drugs through clinical development, including vepdegestrant for locally advanced or metastatic ER+/HER2- breast cancer; ARV-393 for relapsed/refractory non-Hodgkin lymphoma; ARV-102 for neurodegenerative disorders; and ARV-806, targeting Kirsten rat sarcoma (KRAS) G12D in cancers harboring this mutation, including pancreatic and colorectal cancers.

And that KRAS effort landed like a statement of intent. KRAS has been considered “undruggable” for decades—the poster child for targets traditional drugs couldn’t hit. If Arvinas can make a degrader work against KRAS G12D, it wouldn’t just be another pipeline addition. It would be a direct demonstration of why protein degradation was worth building a company around in the first place.

XII. Business Model & Unit Economics

To make sense of Arvinas as a business, you have to accept the strange economics of biotech. This isn’t software. You don’t ship an MVP, iterate, and compound. You place a few expensive, high-conviction bets, and the outcomes can be brutally binary.

Drug development demands huge up-front spend—years of research, manufacturing work, and clinical trials—with no guarantee of success. A program can absorb hundreds of millions of dollars and still fail late, erasing years of progress. But if a drug works and reaches the market, it can generate billions and completely reset a company’s trajectory.

Arvinas has tried to navigate that reality with a hybrid strategy: keep building wholly owned degraders internally, while also partnering select programs with large pharma.

That model comes with real upside:

- Partner upfront payments and milestones can help fund internal R&D

- Partners can shoulder much of the development cost for the assets they take on

- Risk gets spread across more targets and therapeutic areas

- Big-name partnerships serve as external validation of the platform

But there are trade-offs too:

- Partnered programs usually cap upside—royalties and milestones aren’t the same as full ownership

- Your timeline can become dependent on a partner’s priorities

- Execution risk doesn’t disappear; it just shifts partly onto someone else

At the time of these figures, the market data looked roughly like this: market cap around $786 million, about 64 million shares outstanding, and average daily trading volume a bit over one million shares. Financially, Arvinas still wasn’t profitable—exactly what you’d expect for a clinical-stage biotech. Most revenue came from collaboration agreements, not product sales.

The key strategic asset was still the balance sheet. Based on its operating plan, Arvinas expected its cash runway to extend into 2027 and potentially beyond, giving it time to keep advancing its clinical programs and to pursue the next set of value-creating readouts and milestones.

XIII. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Porter's Five Forces:

Threat of New Entrants: MODERATE-HIGH

Protein degradation demands real scientific depth, but that hasn’t stopped a crowd from forming. Over the past two decades, roughly two dozen biotechs have launched to build PROTACs, molecular glues, and other degrader approaches—and Big Pharma has been building in-house teams right alongside them. The counterweight is that Arvinas has a decade-plus head start, a meaningful patent estate, and one of the earliest clinical data packages in the category, which raises the bar for anyone trying to break in and catch up.

Supplier Power: LOW-MODERATE

Like most clinical-stage biotechs, Arvinas depends on CROs and CMOs to run studies and make drug supply. Those services are specialized, but they’re not controlled by a single gatekeeper. There are alternatives, and while switching can be painful, suppliers generally don’t hold all the leverage.

Buyer Power: HIGH

In biotech, “buyers” aren’t just future patients. They’re also pharmaceutical partners deciding whether to license, collaborate, or wait—and payers deciding what they’ll reimburse once a product exists. Both groups have leverage. Partners can shop deals across multiple degrader companies, and payers can insist on clear evidence that a PROTAC is better than what’s already on the market, not just different.

Threat of Substitutes: HIGH

PROTACs don’t compete in a vacuum. They’re up against traditional small molecules and biologics aimed at the same diseases. And for targets like ER and AR, the standard of care is already crowded. That means degraders have to win on real-world performance—efficacy, durability, safety, convenience—not on mechanism alone.

Competitive Rivalry: INTENSIFYING

Arvinas has held a leading position in targeted protein degradation, but the gap has narrowed as more companies generate clinical data. Competitors such as Kymera Therapeutics and C4 Therapeutics are part of a broader group pushing the field forward. As datasets mature, the fight shifts from “can this work?” to “whose molecules work best, in which patients, and at what cost?”

Hamilton's Seven Powers:

1. Scale Economies: LIMITED

In R&D-heavy biotech, scale doesn’t help much until you’re manufacturing at volume and selling a product. If Arvinas reaches commercialization, scale could matter more in manufacturing and go-to-market execution—but in the discovery and clinical phases, the benefits are modest.

2. Network Economies: MINIMAL

Drug development doesn’t compound through classic network effects. Each program largely stands on its own.

3. Counter-Positioning: STRONG

This is the heart of the Arvinas thesis. Degradation versus inhibition is a different paradigm, and incumbents were slow to fully embrace it. The PROTAC platform aims to use the cell’s ubiquitin-proteasome machinery to remove disease-causing proteins, rather than simply blocking them. In theory, by eliminating the target protein, PROTACs can offer advantages over traditional small-molecule inhibitors—especially when inhibition isn’t enough or resistance emerges.

4. Switching Costs: MODERATE

Once a patient is doing well on a therapy, physicians hesitate to switch. That stickiness can be real—but it only becomes relevant after approvals and real-world adoption.

5. Branding: DEVELOPING

Arvinas benefits from being widely seen as the PROTAC pioneer, especially among scientists, investors, and potential partners. That reputation can help in partnering conversations, hiring, and credibility when the modality is under scrutiny.

6. Cornered Resource: STRONG

As targeted protein degradation has matured, Arvinas has stood out through early clinical progress, strategic alliances, and accumulated expertise in rational degrader design. The founding scientists, the patent estate, and years of hard-won know-how are assets competitors can’t quickly recreate.

7. Process Power: BUILDING

Arvinas has argued that its advantage isn’t just the concept—it’s the repeated process of making degraders that actually work. The company points to linkers built from years of learning, plus trimer structure-based computational modeling and design algorithms, as tools that can yield potency and selectivity earlier in a program. This power is still forming, and the catch is that competitors are investing heavily to build similar capabilities.

Netting it out, the most durable powers for Arvinas appear to be Counter-Positioning—degradation as a fundamentally different way to make drugs—and Cornered Resource—the founders, IP, and first-mover clinical credibility. Process Power is moving in the right direction, but it’s also the area where the field is catching up fastest.

XIV. Bull vs. Bear Case

Bull Case:

Platform Paradigm Shift: If targeted protein degradation really does open up the large portion of the proteome that traditional drugs struggle to touch, Arvinas isn’t just selling a couple of assets—it’s sitting on a repeatable machine. In the best version of this story, that machine keeps producing new candidates across oncology, neurology, immunology, and beyond.

First-Mover Advantage: Arvinas got to humans first, and it’s still the only company that has shown positive Phase 3 clinical benefit with a PROTAC. That matters. Clinical reps are a form of compounding: every dose, every biomarker readout, every safety signal feeds back into how you design the next molecule and the next trial.

Partnership Validation: Pfizer, Genentech/Roche, Novartis, and Bayer didn’t sign up on vibes. When that caliber of partner puts meaningful capital and milestone potential behind a platform, it’s a strong signal that the diligence was real—and that the underlying science cleared a high bar.

Multiple Shots on Goal: Arvinas isn’t betting the company on a single mechanism in a single disease. The pipeline spans ER in breast cancer, AR in prostate cancer, BCL6 in lymphoma, LRRK2 in Parkinson’s disease, and KRAS G12D in cancers like pancreatic and colorectal. If even one of these turns into a durable, differentiated drug, it can change what the whole company is worth.

Acquisition Potential: If you’re a large pharma company that wants a credible foothold in protein degradation, buying a pioneer with platform know-how, IP, and clinical assets is an obvious shortcut. Arvinas has long sat on the shortlist of “could be bought” names for exactly that reason.

Vepdegestrant Path Forward: Even if vepdegestrant’s best path is a narrower ESR1-mutant label, approval could still mean real revenue—and something equally valuable: the first commercial proof that a PROTAC can become an actual product, not just a scientific promise.

Bear Case:

Clinical Data Hasn’t Been Broadly Convincing: VERITAC-2 delivered a meaningful win in ESR1-mutant disease, but not in the overall intent-to-treat population. If the platform’s benefits routinely concentrate in smaller, molecularly defined subgroups, the commercial ceiling shrinks—and the “platform premium” investors assign can compress fast.

PROTACs May Have Inherent Limitations: These molecules are large, and size brings baggage: challenges with oral bioavailability, tissue distribution, and manufacturing complexity. Some targets may simply be poor fits for the modality, no matter how good the biology looks on paper.

Competition Intensifying: Protein degradation isn’t a quiet corner of biotech anymore. Big Pharma has built internal teams, and competitors are pushing their own candidates into the clinic. In that world, Arvinas’ early lead matters less each year unless it keeps producing best-in-class molecules.

Capital Intensive with Binary Outcomes: Even with a strong cash position, biotech timelines have a way of stretching—especially when you’re running multiple clinical programs. If key studies disappoint or take longer than planned, Arvinas could be forced back to the market for capital, potentially at unfavorable valuations.

Traditional Drugs May Be “Good Enough”: For many targets, inhibitors already work. To win, degraders have to prove they’re not just different—they’re better in outcomes patients and payers care about. That’s a high bar in crowded categories like hormone-driven cancers.

Partner Dependency: Partnerships can accelerate programs, but they also add another set of incentives and decision-makers. The vepdegestrant collaboration has already gone through strategic pivots, and partner choices can materially change timelines, investment levels, and economics.

Key Metrics to Watch:

For long-term investors tracking Arvinas, three KPIs matter most:

-

Clinical Success Rate: How often do Arvinas programs produce clear, actionable clinical signals as they move through development? In drug development, failure is the default, and consistency is rare.

-

Partner Milestone Achievement: Do collaborations translate into real milestone payments tied to program advancement? That’s both validation and a funding source.

-

Cash Burn Rate: How quickly is Arvinas spending its cash relative to meaningful progress and upcoming data catalysts? Runway only matters in context: what you can reach before you have to raise again.

XV. The Bigger Picture: What This Means for Drug Discovery

Zoom out far enough from Arvinas, and protein degradation stops looking like a quirky new mechanism and starts looking like a fork in the road for drug discovery itself.

The big question isn’t whether PROTACs work on any one target. It’s whether targeted protein degradation becomes a true platform—something like monoclonal antibodies, where entire companies and pipelines are built around it—or whether it ends up as a feature that every drugmaker eventually folds into the standard toolkit. Kinase inhibitors are the obvious precedent: once revolutionary, now routine. Degradation could follow the same arc—today’s headline, tomorrow’s default.

Ray Deshaies captured that inflection point in the mid-2010s. After the 2015 wave of small-molecule PROTACs, he wrote an opinion piece arguing that PROTACs could become a major new class of drugs—possibly even surpassing two of the most celebrated categories in modern pharma: protein kinase inhibitors and monoclonal antibodies. “The gold rush is on!” he wrote.

And you can see why. The ultimate prize is still the same one drug developers have chased for decades: the so-called “undruggable” proteome—the large share of proteins that traditional small molecules can’t effectively target. Transcription factors. Scaffolding proteins. The flat, slippery surfaces where proteins interact with other proteins. These are the kinds of targets that sit at the center of disease biology and, for years, have sat just outside the reach of classic inhibition. If degraders can consistently reach into that territory, the impact won’t be confined to Arvinas, or even to oncology. It changes what we can plausibly try to treat.

Arvinas also reflects something broader about how modern drug revolutions happen. The academic-industrial pipeline that made the company possible—Yale generating foundational science, Caltech contributing complementary expertise, venture capital funding the leap, and Big Pharma validating and scaling the effort—has become a repeatable pattern in biotech. Crews’ path from academic investigator to founder to chairman isn’t an outlier anymore. It’s increasingly the job description when the science is big enough.

XVI. Epilogue & Recent Developments

By late December 2025, Arvinas sat right where biotech stories tend to get most dramatic: at the edge of a yes-or-no moment.

Vepdegestrant had been granted Fast Track designation by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, and it had a Prescription Drug User Fee Act (PDUFA) action date of June 5, 2026.

That decision is the company’s biggest near-term catalyst. If vepdegestrant is approved, it won’t just be another product launch. It would be the first PROTAC therapy approved anywhere in the world—a milestone for Arvinas and a referendum on the entire targeted degradation idea, regardless of how narrow the first indication turns out to be.

Behind that headline, the rest of the platform is still moving. Arvinas said it would present multiple-dose patient data for ARV-102 in 2026 and, depending on those results and IND clearance, planned to initiate a Phase 1b trial in progressive supranuclear palsy in the first half of 2026. ARV-102’s earlier work supporting brain penetration and LRRK2 degradation matters for a simple reason: it’s the proof that degradation can play beyond oncology, in the most demanding terrain of all—neurology.

ARV-393 also remained in the clinic, in a Phase 1 trial for patients with relapsed/refractory non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Arvinas planned to share clinical data from that study at a medical congress in 2026.

All of this unfolds amid leadership transition and shifting partnership dynamics. The company John Houston built over eight years was preparing for its next act under new leadership, with clinical readouts and strategic decisions poised to define what comes next.

As of December 19, 2025, Arvinas had 430 employees.

From about twenty people in 2013 to more than four hundred, from a contrarian concept in Craig Crews’ Yale lab to Phase 3 clinical success, Arvinas has shown that targeted protein degradation can work in human patients. Whether it can turn that scientific breakthrough into a durable, profitable business is still the question that matters most.

XVII. Outro & Key Takeaways

The Arvinas story is the essential drama of modern biotech: a bold scientific idea colliding with the messy, expensive reality of turning molecules into medicines—while the rest of the industry races to catch up.

What makes Arvinas emblematic:

The Long Arc of Innovation: The core PROTAC concept appeared in 2001. The first Phase 3 clinical benefit for a PROTAC didn’t arrive until 2025. That gap isn’t a detour—it’s the job. Biology moves at its own pace, and drug development tests patience, conviction, and memory.

Science Risk vs. Execution Risk: Arvinas helped answer the scientific question: yes, targeted degradation can work in human patients. The harder question is the business of it—choosing the right targets, designing the right molecules, running the right trials, and earning approvals in indications where “different” isn’t enough. You have to be better.

Platform vs. Product: Arvinas tried to do both—license the engine to partners and build its own drugs. That structure can diversify risk and bring in capital, but it also adds complexity: shared incentives, shifting priorities, and constant decisions about what to keep, what to partner, and what to walk away from.

The Importance of Capital: This was never going to be a cheap revolution. Arvinas needed real funding—equity, partnerships, and milestones—to survive the long stretch between “mechanism proved” and “medicine approved.” Without patient capital, protein degradation could have stayed a beautiful academic idea.

Counter-Positioning as Competitive Advantage: Arvinas didn’t win by making a slightly better inhibitor. It pushed a different paradigm—degradation instead of inhibition—and built early credibility, IP, and know-how around that bet. The catch is that once the world believes, the world shows up. First-mover advantage only lasts if the molecules keep winning.

For founders and investors, Arvinas is a reminder that transformative biotech is never just about being right scientifically. It’s about enduring long enough—and executing well enough—for the science to matter in the clinic.

The next chapter won’t be written in press releases. It’ll be written in trial readouts, regulatory decisions, and, if the promise holds, in the lives of patients who finally get options for targets medicine used to call “undruggable.” That’s the prize Arvinas—and the entire targeted protein degradation field—is still chasing.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music