Ardelyx Inc.: The Story of a Hyperphosphatemia Pioneer

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

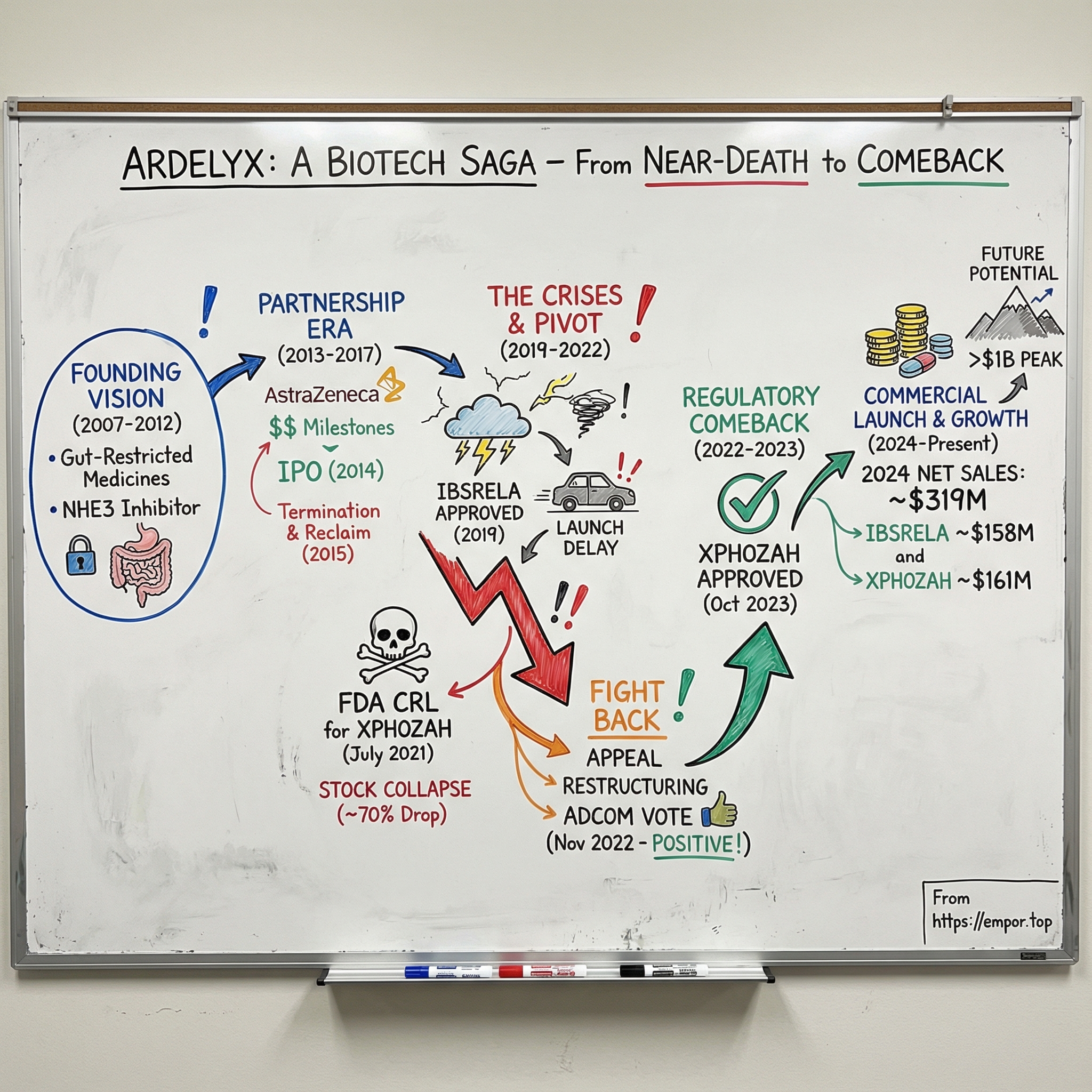

Picture this: July 2021. In the executive offices of a small biotech in Fremont, California, the phones won’t stop ringing. Ardelyx’s stock is collapsing—down roughly two-thirds in premarket trading. The trigger is a brutal message from the FDA: the agency is signaling that approval of Ardelyx’s lead drug for dialysis patients is highly unlikely.

That’s not just a bad day. It’s an existential one.

By this point, Ardelyx has been at this for more than a decade. The company has run three successful Phase 3 trials in over a thousand patients. It’s been deep in what looked like constructive, endgame labeling talks with regulators. And now, in one letter, the FDA is effectively saying: not good enough.

For a lot of biotechs, this is where the story ends—management looks for a fire sale, or quietly winds the company down. Ardelyx didn’t do that. They fought back.

This is the story of how Ardelyx—a specialized biopharmaceutical company focused on first-in-class medicines in cardiorenal disease—went from the edge of extinction to commercial success. It’s a tale of persistence with regulators, painful strategic pivots, partnership trade-offs, and the unforgiving economics of small biopharma.

And the comeback is real. In 2024, Ardelyx reported about $319 million in total U.S. net product sales. IBSRELA, its IBS-C drug, brought in roughly $158 million. XPHOZAH, its kidney-focused product, added about $161 million. The company also pointed to peak U.S. sales potential of over $1 billion and $750 million for its lead products.

So that’s the question we’re going to answer: how does a company go from two consecutive FDA rejections to commercial liftoff? And what can Ardelyx teach us about surviving in biotech—where the science is only the beginning, the regulator can rewrite your fate, and “approved” still doesn’t mean “successful”?

II. The Founding Vision & Early Scientific Bet (2007–2012)

In 2007, the world was lurching toward the subprime mortgage crisis. The iPhone had just arrived. And in Fremont, California, a small team started building a biotech around an idea that ran against the grain of how most drugs are made.

Ardelyx was founded that year, with early leaders including Dominique Charmot, Peter Schultz, and Jean-Frederic Viret—drawing on experience from Symyx Technologies and the Scripps Research Institute. The company originally went by Nteryx, Inc., then renamed itself Ardelyx, Inc. in June 2008. It was incorporated in 2007, started out in Fremont, and later moved its headquarters to Waltham, Massachusetts.

The founding bet was simple to say and hard to execute: make drugs that do their work in the gastrointestinal tract, and don’t meaningfully enter the bloodstream.

That “gut-restricted” thesis mattered because it flipped the usual trade-off in medicine. Most drugs get absorbed and circulate throughout the body—often delivering the benefit, but also dragging along side effects and drug-drug interactions. Ardelyx wanted the opposite: keep the action local, get the therapeutic effect, and minimize collateral damage.

Investors were willing to fund the experiment. In 2008, the company raised a $25 million Series A led by Domain Associates and New Enterprise Associates (NEA). By that point, Ardelyx had raised $56 million in venture and angel funding since its 2007 founding.

Scientifically, the early platform focused on small-molecule inhibitors aimed at ion transporters in the gut. The lead target was NHE3, the sodium-hydrogen exchanger 3—a protein that helps regulate sodium absorption in the intestinal tract. Ardelyx’s lead program, RDX5791, was a minimally absorbed, oral NHE3 inhibitor being developed for constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-C) and for preventing excess dietary sodium absorption.

The strategy wasn’t just about scientific novelty. It was also about where the biggest medical and commercial pain lived. Ardelyx set its sights on cardiorenal and gastrointestinal disease—areas where patients often juggle chronic conditions and treatments that can be blunt instruments. Chronic kidney disease alone affects millions of people, many of whom deal with metabolic complications that existing therapies only partly manage.

So in those early years, the pitch had a clean logic: a new mechanism, a potentially cleaner safety profile, and huge markets with real unmet need. But it also came with the kind of risk that defines biotech—because if “gut-restricted” didn’t translate from elegant theory to real-world outcomes, there was nowhere to hide.

III. Building the Pipeline: Tenapanor's Origins (2012–2016)

By 2012, Ardelyx had made the leap every young biotech dreams about: it was no longer just a platform and a pitch deck. It had a lead drug candidate with real clinical momentum. That molecule was tenapanor, a small-molecule inhibitor of NHE3 that would soon become the center of gravity for the whole company—its biggest opportunities, and later, its biggest scares.

Tenapanor was designed to act where Ardelyx always believed the magic would happen: in the gut, with minimal systemic exposure. In human and animal studies, it showed it could reduce absorption of dietary sodium and phosphorus—two levers that matter enormously in kidney disease.

To understand why phosphorus became such a big deal, you have to follow the biology. When you eat, phosphate from food gets absorbed through the intestinal wall into the bloodstream. If your kidneys work, they act like a regulator—filtering and excreting the extra. But for patients with chronic kidney disease on dialysis, that system breaks. Phosphate accumulates, and over time it contributes to serious downstream problems, including vascular calcification, bone disease, and higher cardiovascular mortality.

The standard of care was a workaround: phosphate binders. These drugs don’t fix the underlying absorption problem; they try to trap phosphate in the gut so it never gets into the bloodstream. In practice, that’s messy. Binders can also bind to other minerals like calcium and iron, creating supplementation headaches. And the pill burden is brutal—patients with hyperphosphatemia take, on average, around 19 pills a day—often with significant GI side effects. Adherence becomes a daily battle.

Tenapanor promised a different approach. Instead of binding phosphate, it aimed to reduce phosphate absorption by changing how the gut transports it. As a first-in-class phosphate absorption inhibitor, tenapanor acted locally by inhibiting NHE3 and reducing phosphate absorption via the paracellular pathway, the primary route for phosphate absorption.

But tenapanor’s story wasn’t just a kidney story. The same mechanism that altered absorption also pulled more fluid into the gut—an effect that, in another context, looked like a feature, not a bug. That opened the door to constipation-related disorders, including IBS-C. In October 2014, Ardelyx reported positive results from a Phase 2b randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled 12-week trial in 371 IBS-C patients. The study met its primary endpoint: patients on tenapanor 50 mg twice daily had a higher rate of complete spontaneous bowel movement responders compared to placebo.

That potential to play in two worlds was strategically powerful. If IBS-C worked, Ardelyx could validate the mechanism in a large market with a clearer regulatory path—and potentially generate revenue to help fund the harder, higher-stakes kidney indication. If hyperphosphatemia worked, Ardelyx would have a differentiated option in a space where physicians and patients both knew the existing tools were far from ideal.

Clinically, the early dataset was encouraging. Ardelyx and AstraZeneca evaluated tenapanor across eight human trials in more than 750 individuals. In Phase 1 and Phase 2 studies, the drug was generally well-tolerated and showed it could divert sodium into the stool in both healthy volunteers and patients with ESRD on hemodialysis. In Phase 1 trials in healthy adults, tenapanor also inhibited dietary phosphorus absorption, including with 15 mg taken orally twice daily.

This was the bet Ardelyx made in these years: pursue multiple indications in parallel, even though it would be expensive and complicated. For a small company with a novel mechanism, it was also a form of insurance. If one path ran into a wall, another might still get through.

IV. The Partnership Era & Global Expansion (2013–2017)

Every small biotech runs into the same trade-off: clinical trials are expensive, but selling stock to pay for them dilutes everyone you’ve already convinced to believe. The classic escape hatch is a partnership—swap some future upside for cash today, plus a bigger partner’s experience.

Ardelyx leaned hard into that playbook.

In October 2012, it entered a collaboration with AstraZeneca to develop and commercialize tenapanor. The structure followed the familiar script: AstraZeneca paid $35 million up front, with the potential for hundreds of millions more in development and commercialization milestones.

Those milestones started arriving quickly. In January 2014, Ardelyx announced it had received $15 million from AstraZeneca tied to a development milestone. Then in May 2014, it received another $25 million for the initiation of a Phase 2b study evaluating tenapanor in hyperphosphatemia. By that point, Ardelyx had collected $75 million in up-front and milestone payments from AstraZeneca.

For a small clinical-stage company, that kind of deal is rocket fuel. It’s cash. It’s validation. It’s a signal to the market that a global pharma player has done the diligence and likes what it sees. But it also comes with the catch that defines every partnership: you’re no longer the only one steering.

Around the same time, Ardelyx went public. On June 18, 2014, the company priced its IPO at $14 per share for 4,286,000 shares, and began trading on NASDAQ on June 19. The IPO gave Ardelyx another financing lever—one that didn’t require handing over more control of its lead asset.

And that control was about to matter.

In May 2015, tenapanor missed its primary endpoint in a Phase IIa trial in patients with Stage 3 chronic kidney disease with type 2 diabetes and albuminuria. The setback wasn’t just a clinical disappointment. It also complicated the partnership dynamics. When a program stumbles, priorities shift—and small companies can find themselves waiting while a giant partner decides what it wants to do next.

Ardelyx chose not to wait.

On June 3, 2015, Ardelyx announced it had entered into a termination agreement with AstraZeneca. All rights to the NHE3 portfolio—including tenapanor—came back to Ardelyx. But taking back the keys wasn’t free. Ardelyx agreed to pay AstraZeneca $15 million up front, plus additional future contingent payments, and it also paid an additional $10 million in R&D costs at the time.

All-in, the termination terms could add up to as much as $110 million, including up to $90 million comprised of the $15 million fee, royalties equal to 10% of net sales of tenapanor sold by Ardelyx or a licensee, and 20% of non-royalty payments Ardelyx might receive if it later licensed tenapanor to another partner.

So why pay to reclaim your own drug?

Ardelyx’s rationale was speed—and focus. By ending the AstraZeneca partnership, the company said it could move faster on tenapanor in IBS-C, and it planned to launch a Phase III program in the fourth quarter of 2015.

It was a classic biotech gamble: high risk, high reward. Full control meant Ardelyx could set the clinical strategy and move on its own timeline. It also meant the company now carried the full weight of development costs and execution risk.

At the same time, Ardelyx didn’t abandon partnerships altogether. It shifted to a more targeted strategy: license specific geographies while keeping U.S. control.

In November 2017, Ardelyx and Kyowa Hakko Kirin announced a license agreement granting Kyowa Hakko Kirin exclusive rights to develop and commercialize tenapanor for cardiorenal diseases, including hyperphosphatemia, in Japan. Ardelyx received a $30 million upfront payment, became eligible for up to $130 million in additional development and commercialization milestones, and would receive high-teen royalties.

That territorial approach—partner where it made sense, keep the U.S. upside—would later look prescient. When the U.S. regulatory picture for kidney disease started to darken, Japan would become an important proof point that tenapanor could still win somewhere.

V. The IBS-C Journey: FDA Approval & Commercial Reality (2017–2020)

On September 12, 2019, Ardelyx finally got the moment every biotech is built to chase: the FDA approved IBSRELA (tenapanor), a 50 mg pill taken twice a day, for irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (IBS-C) in adults.

Mechanistically, it was pure Ardelyx. IBSRELA is a minimally absorbed small molecule that works locally in the GI tract. By inhibiting NHE3, it increases bowel movements and reduces abdominal pain—two of the outcomes IBS-C patients care about most.

It was also a genuine milestone for the company: Ardelyx’s first FDA approval, and a first-in-class approval at that. IBSRELA became the first and only FDA-approved NHE3 inhibitor for IBS-C.

The Phase 3 package did what it needed to do. In both pivotal IBS-C trials, IBSRELA beat placebo on the primary endpoint (Trial 1: 37% versus 24% IBSRELA versus placebo; Trial 2: 27% versus 19% IBSRELA versus placebo). Across both trials, more patients responded on IBSRELA than on placebo.

But here’s the part that surprises people outside biotech: getting approved isn’t the same thing as getting adopted.

Even after the September 2019 approval, Ardelyx ran into an awkward commercial reality—it didn’t have a U.S. commercial partner ready to take IBSRELA to market. And that gap dragged on. The company struggled to secure the kind of launch support it needed, a problem that may have been compounded by the broader uncertainty hanging over tenapanor’s other, higher-stakes program in hyperphosphatemia.

So IBSRELA sat in a strange limbo: approved, but not meaningfully selling. It wasn’t until April 2022 that Ardelyx launched IBSRELA in the U.S.

That delay is one of biotech’s most punishing, least talked-about costs. Every month between approval and launch is a month with no product revenue—just cash burn, more dilution risk, and momentum handed to incumbents.

And when IBSRELA did reach the market, it walked into a knife fight. IBS-C was already crowded, with entrenched competitors like Ironwood Pharma’s Linzess holding years of physician familiarity and payer coverage. Early on, IBSRELA’s sales reflected that reality, with quarterly revenue around $5 million.

It’s a lesson that shows up again and again: FDA approval is necessary, but it’s not sufficient. Commercial execution—educating physicians, winning formulary placement, and grinding through payer negotiations—requires a totally different muscle than clinical development. Being first-in-class doesn’t automatically translate into being first-choice.

Then COVID hit in early 2020, and the timing got even worse. GI prescriptions were pressured as patients avoided in-person visits and elective healthcare dropped sharply—exactly the kind of environment where a new branded GI drug struggles to break through.

VI. The Hyperphosphatemia Catastrophe (2019–2021)

If the IBS-C story was frustrating, the hyperphosphatemia story was an extinction-level event.

Ardelyx had spent years building what looked like a clean, compelling regulatory case for tenapanor in dialysis patients with elevated serum phosphorus. The NDA rested on a broad clinical program: more than 1,200 patients across three Phase 3 trials—PHREEDOM, BLOCK, and AMPLIFY. All three hit their primary endpoints, along with key secondary endpoints. The company had even moved into labeling discussions with the FDA, the kind of late-stage detail work that usually means you’re arguing over wording, not whether the drug works.

So when the FDA response arrived, it didn’t land like a setback. It landed like a trap door.

In July 2021, after the agency extended the review period by three months, the FDA issued a Complete Response Letter. The core problem wasn’t that tenapanor failed to lower serum phosphorus. The CRL explicitly said the submitted data provided substantial evidence that it did. The problem was the FDA’s interpretation of how much it mattered: the agency described the effect as “small and of unclear clinical significance,” and told Ardelyx it would need to run another adequate and well-controlled trial to confirm a clinically relevant treatment effect.

Wall Street heard that as “not happening.” Ardelyx’s stock collapsed—down roughly 70% to 74% in a day, with shares falling to about $2.

The whiplash didn’t stop at investors. The decision surprised many in the nephrology community, too. One nephrologist said they had followed the extensive development program closely, seen benefits in patients first-hand, and were stunned the FDA wouldn’t approve a novel mechanism drug despite what they viewed as strong safety and efficacy data.

Analysts were equally blunt. A Piper Sandler team said it was “flummoxed” by what they viewed as conflicting FDA messaging—especially given the prior move into labeling talks—and they described the decision as capricious and even “nonsensical,” warning it could deepen mistrust in the agency.

Inside Ardelyx, the CRL forced immediate triage. The company went into survival mode and announced a restructuring that cut 33% of its workforce—about 83 people—with the goal of saving roughly $17 million per year. CEO Mike Raab called the changes “unfortunate, but necessary” to extend the company’s cash runway.

The context made the stakes impossible to ignore. At the end of 2020, Ardelyx had 129 full-time employees and an accumulated deficit of $588 million. By the end of the first quarter of 2021, it reported $178 million in cash, cash equivalents, and short-term investments. Its stock had traded as high as $9.23 in the prior year. After the rejection, it drifted as low as about $1.61.

Then came the real decision: fold, or fight.

Ardelyx chose to fight. Raab said the company decided to pursue an appeal after it and the FDA couldn’t resolve their disagreement during an End of Review meeting. The appeal process, he explained, would allow Ardelyx to elevate its scientific disagreement above the division level. “We believe that this represents the best approach to obtaining approval of tenapanor.”

It wasn’t just stubbornness. It was the cold arithmetic of biotech. Ardelyx had poured years and enormous capital into tenapanor. The clinical package was large. The mechanism was differentiated. Walking away wouldn’t just end a program—it would force the company to write off the bet that had defined it.

VII. The Strategic Pivot & The Fight Back (2020–2022)

The eighteen months after that first CRL ran on two tracks at once: keep the company alive, and keep the FDA conversation alive.

In April 2022, Ardelyx got a sliver of daylight. The FDA’s Office of New Drugs (OND) sent an interim response to Ardelyx’s second-level appeal of the Complete Response Letter for XPHOZAH. The message wasn’t “yes,” but it also wasn’t “go away.” OND said it would be valuable to get additional input from the Cardiovascular and Renal Drug Advisory Committee—specifically from expert clinicians—on whether the phosphate-lowering effect was clinically meaningful.

For Ardelyx, that advisory committee meeting became the Hail Mary. If an independent panel of experts could look at the same dataset and say, on balance, this drug should be available to dialysis patients, it could change the tone—and the trajectory—of the whole case.

On November 16, 2022, that’s exactly what happened. Ardelyx announced the results of the FDA’s Cardiovascular and Renal Drugs Advisory Committee (CRDAC) vote for XPHOZAH. The panel voted nine to four that the benefits of XPHOZAH outweigh its risks for controlling serum phosphorus in adults with CKD on dialysis when used as monotherapy. Then it voted ten to two, with one abstention, that the benefits outweigh the risks when XPHOZAH is used in combination with phosphate binders.

The market reacted instantly. Ardelyx shares jumped about 59% after the committee recommended approval.

And the subtext mattered as much as the vote. Analysts pointed out that it was unusual for the FDA to convene an advisory committee after already rejecting a drug—and even more unusual for the advisers to come out against the FDA’s earlier stance. In a story that had felt like a dead end, this was the first real sign that the scientific argument might actually land.

Then, on December 29, 2022, Ardelyx announced another milestone: the OND, within the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, granted the company’s appeal of the CRL for the XPHOZAH NDA.

That’s a sentence you almost never get to write in biotech. Complete Response Letters are usually the stop sign. Appeals rarely succeed. Ardelyx had forced the process back open.

While all of that was happening, the company was also just trying to survive the math. After the share-price collapse, Ardelyx leaned on an at-the-market (ATM) facility to sell stock incrementally. Since the initial CRL, it raised $79.0 million in gross proceeds under the ATM, but issued 68.8 million shares as of September 30, 2022—roughly 50% dilution. It also put a debt facility in place in February 2022 that provided another $27.5 million.

One thing kept the team from feeling like they were arguing with reality: Japan.

In December 2021, partner Kyowa Kirin announced that a Phase 3 study of tenapanor in Japan met its primary endpoint. The trial was double-blind and placebo-controlled, enrolling 164 adult hyperphosphatemia patients with chronic kidney disease on hemodialysis. The tenapanor group saw a statistically significant decrease in serum phosphorus levels compared to placebo.

That result didn’t solve the U.S. problem—but it did validate the underlying science at the exact moment Ardelyx needed something to point to besides hope.

VIII. The Regulatory Comeback: FDA Approval (2022–2023)

After the advisory committee surprise and the FDA’s decision to reopen the case, Ardelyx had a narrow window to do the one thing that mattered: put a clean, persuasive application back on the agency’s desk.

On April 18, 2023, Ardelyx announced it had resubmitted its New Drug Application to the FDA seeking approval of XPHOZAH (tenapanor) to control serum phosphate in adults with chronic kidney disease on dialysis who had an inadequate response to, or couldn’t tolerate, phosphate binder therapy. The company said it expected an FDA Acknowledgment of Receipt letter by mid-May.

The FDA accepted the resubmission and classified it as a Class 2 review—meaning a six-month review clock from the resubmission date. The agency set a user fee goal date of October 17, 2023.

Then, on October 17, 2023, Ardelyx got the call it had been trying to earn back for two years: the FDA approved XPHOZAH (tenapanor), the first and only phosphate absorption inhibitor. The indication was to reduce serum phosphorus in adults with chronic kidney disease on dialysis, as add-on therapy for patients who have an inadequate response to phosphate binders or who are intolerant of any dose of phosphate binder therapy.

In biotech, a Complete Response Letter is usually the end of the story. For Ardelyx, it became the middle. Just over two years after the July 2021 rejection, the company had managed the rarest move in the business: it turned “no” into “yes.” “It’s been a long, sometimes arduous path to this day,” said Chief Development Officer David Rosenbaum, who had worked on XPHOZAH for the past 13 years.

The FDA’s approval leaned on what Ardelyx had argued all along: this wasn’t a single-trial fluke. It was a full development package, with more than 1,000 patients across three Phase 3 trials evaluating XPHOZAH as monotherapy and in combination with phosphate binders—each meeting primary and key secondary endpoints. Across those studies, XPHOZAH significantly reduced elevated serum phosphorus in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. The key tolerability issue was diarrhea, reported in 43% to 53% of patients; it was the only adverse reaction seen in at least 5% of treated patients. Most events were mild to moderate and tended to resolve over time or with dose reduction.

The label, though, came with a reminder of how hard-fought this win was. XPHOZAH wasn’t approved as broad, first-line monotherapy—it landed as add-on therapy. Still, after everything Ardelyx had endured, approval wasn’t just a milestone. It was proof the company could survive the FDA gauntlet and come out the other side with a commercial product.

Ardelyx moved quickly to make sure it could actually launch. It secured additional debt financing from SLR Capital Partners, providing access to an initial $50 million, with the potential for another $50 million later. The stock rose around 15% on the news. And heading into the approval stretch, the company reported about $128 million in cash and short-term investments at the end of June 2023.

IX. Commercial Launch & Current State (2024–Present)

Once XPHOZAH was approved, the story stopped being about regulatory survival and became about something just as unforgiving: execution. Ardelyx now had to prove it could turn two products into a real business.

In 2024, it did. Ardelyx delivered approximately $319 million in U.S. net product sales—an unmistakable signal that this wasn’t just an “approved-but-stalled” biotech anymore. The company reaffirmed its view of the long-term upside, pointing to peak U.S. net sales potential of greater than $1 billion for IBSRELA and $750 million for XPHOZAH. It also ended 2024 with approximately $250 million in cash, cash equivalents, and investments—important breathing room in a sector where cash is oxygen.

IBSRELA was the steadier engine. U.S. net product sales for IBSRELA in 2024 were $158.3 million, including $53.8 million in the fourth quarter—about 32% growth compared to the prior year. Ardelyx said it expects IBSRELA to surpass ten percent market share at peak and generate more than $1.0 billion in annual U.S. net product sales revenue before patent term expiration.

XPHOZAH, meanwhile, came out of the gate fast. It posted approximately $161 million in U.S. net product sales in 2024—its first full year on the market—what the company characterized as an exceptional launch.

Financially, the company’s losses narrowed as revenue scaled. Net loss for the year ended December 31, 2024, was $39.1 million, or $(0.17) per share, compared to a net loss of $66.1 million, or $(0.30) per share, for the year ended December 31, 2023. The 2024 net loss included $37.4 million in share-based compensation expense.

Looking ahead, Ardelyx guided that full-year 2025 U.S. net product sales revenue for IBSRELA would be between $240.0 and $250.0 million.

“Ardelyx enters 2025 in a position of strength, evidenced by significant year-over-year revenue growth for IBSRELA in 2024 and a strong first full year of XPHOZAH commercialization, driven by consistently high levels of commercial excellence, meaningful long-term potential for our existing commercial products and a strong cash position to support future growth opportunities.”

International expansion continued through partnerships. By this point, Ardelyx had two commercial products approved in the United States—IBSRELA and XPHOZAH—plus early-stage pipeline candidates, and a growing web of ex-U.S. agreements for tenapanor. Kyowa Kirin commercialized PHOZEVEL (tenapanor) for hyperphosphatemia in Japan. In China, Fosun Pharma had submitted a New Drug Application for tenapanor for hyperphosphatemia. And in Canada, Knight Therapeutics commercialized IBSRELA.

The pipeline kept moving, too. Ardelyx advanced RDX013, a Phase 2 potassium-lowering compound being developed for elevated serum potassium, or hyperkalemia, a problem among certain patients with kidney and/or heart disease. It also maintained an early-stage program in metabolic acidosis, a serious electrolyte disorder in patients with CKD.

And there was one more signal of how broadly Ardelyx wanted to push XPHOZAH’s reach: in November 2023, XPHOZAH was granted Orphan Drug Designation by the U.S. FDA for the treatment of pediatric hyperphosphatemia.

X. The Business Model & Economics of Rare Disease Biopharma

Ardelyx is a specific kind of biotech: a specialty pharma company built to win in narrow, high-need populations with a novel mechanism, then do the unglamorous work of getting that medicine paid for, prescribed, and used. When it works, the model can look incredibly efficient. When it doesn’t, the limitations show up fast—because small companies don’t get many second chances.

The market incentives are real. Hyperphosphatemia is a serious complication of kidney failure, and it’s estimated to affect the vast majority of roughly 550,000 people in the United States on maintenance dialysis. Globally, the hyperphosphatemia treatment market was valued at about $1.49 billion in 2024 and projected to grow over time.

But “big market” doesn’t mean “easy market.” Kidney medicine is full of incumbents, and the standard of care is deeply entrenched. In hyperkalemia, for example, AstraZeneca’s LOKELMA (sodium zirconium cyclosilicate), approved by the FDA in November 2018, carved out its place by competing with older options like sodium polystyrene sulfonate (Kayexalate) and newer agents like patiromer (Veltassa). That dynamic—multiple available therapies, each with trade-offs—gives physicians options and gives payers leverage.

Still, the upside can be massive if you can change practice. The hyperkalemia drug market has been predicted to grow dramatically to more than $2 billion, largely if drugmakers can persuade physicians to keep chronic kidney disease patients on renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors—and then manage chronic hyperkalemia rather than abandoning those therapies.

Ardelyx’s leadership is unusually well-matched to this exact battlefield. Mike Raab has served as Ardelyx’s President and CEO since March 2009. Before Ardelyx, he was a partner at New Enterprise Associates focused on healthcare investing, and before that he spent 15 years in commercial and operating leadership roles across biotech and pharma. Notably, he was senior vice president, therapeutics and general manager of the renal division at Genzyme, where he launched and oversaw the growth of sevelamer, a leading phosphate binder that reached more than $1.0 billion in worldwide sales in 2013.

That experience isn’t just “good resume” material—it’s directly relevant to Ardelyx’s core challenge. Raab has lived the product positioning, reimbursement grind, and competitive knife fights of renal medicine. He’s competed in the same category Ardelyx is now trying to reshape.

And Ardelyx’s R&D story captures both the beauty and the brutality of this business model. On the one hand, tenapanor became a rare example of platform efficiency: the same molecule ultimately produced three approvals—two in the U.S. and one in Japan—across two indications. On the other hand, it took nearly 15 years from founding to reach true commercial scale, and the road there ran through multiple near-fatal setbacks. In biopharma, that’s the trade: incredible operating leverage if you succeed, and a long, expensive walk to get there.

XI. Porter's 5 Forces Analysis

Competitive Rivalry (Medium-High): This is not a greenfield market. Phosphate management in dialysis has entrenched habits, entrenched products, and physicians who already have routines that “work well enough.” In practice, many nephrologists treat Lokelma and Veltassa as options for the same types of patients, which is a tell: when two brands feel interchangeable at the point of prescribing, competition turns into a grind. XPHOZAH does have a clean narrative advantage—an absorption inhibitor rather than another binder—but differentiation on a slide deck isn’t the same as changing behavior in clinics. That takes time, data, and sustained commercial pressure.

Threat of New Entrants (Medium): The bar to enter is high—trials, regulators, specialized prescribers—but the prize keeps pulling new players in. In June 2024, Alebund Pharmaceuticals received Breakthrough Therapy Designation from China’s NMPA for AP306, an investigational therapy in development for hyperphosphatemia in CKD. And zooming out, big pharma continues to pour capital into cardiorenal disease. If a new entrant shows meaningfully better efficacy or tolerability, incumbents can lose ground quickly.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers (Low): Ardelyx isn’t gated by some rare manufacturing ingredient or a single specialized supplier. These are standard pharmaceutical inputs with plenty of contract manufacturing options, which keeps supplier leverage modest.

Bargaining Power of Buyers (High): In kidney disease, “the buyer” is really the payer and the formulary committee. They decide what gets covered, on what tier, and with which restrictions—and that largely decides what gets prescribed. North America led the global hyperphosphatemia treatment market with a 43.09% share in 2022, driven by a large dialysis population and strong healthcare infrastructure. But that scale comes with strings: many dialysis patients are covered by Medicare and Medicaid, which adds pricing pressure and makes access negotiations a central part of the business.

Threat of Substitutes (Medium-High): The biggest substitute isn’t a flashy new drug—it’s the status quo: dietary management and cheaper, generic phosphate binders. And patient behavior matters here more than most markets. A major constraint on treatment is compliance, because binders come with a heavy pill burden and GI side effects. Nearly 80% of patients take four or more phosphate-binder pills daily, which can be hard to sustain. That pain creates an opening for better options—but it also means “do nothing different” remains a real competitor, every single day.

XII. Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economics (Weak): In specialty pharma, manufacturing isn’t where the advantage lives. The real scale benefit is commercial—more reps spread across more prescribers, more leverage with payers, more dollars to keep the message in the market. Ardelyx can get more efficient as volume grows, but it doesn’t have anything like the scale of a major pharmaceutical company.

Network Economics (None): Drugs don’t get more valuable because more people take them. One patient’s prescription doesn’t make the next patient’s prescription easier, cheaper, or better.

Counter-Positioning (Weak-Medium): XPHOZAH’s phosphate absorption inhibitor approach is meaningfully different from phosphate binders, and that difference gives Ardelyx a real story to tell. But it’s not a position competitors can’t chase. If incumbents decide the category is big enough, they can fund their own next-generation mechanisms.

Switching Costs (Medium): After its 2023 approval, tenapanor was adopted by roughly 15% of eligible U.S. dialysis patients in its first year. That kind of early traction builds familiarity, and familiarity creates inertia—doctors tend to keep prescribing what they know works. Still, these aren’t hard switching costs. If another product shows clearly better efficacy or tolerability, the market can move.

Branding (Weak-Medium): This isn’t a consumer brand business. For physicians, the “brand” is the data, the label, and their experience using the drug in real patients. Ardelyx can build credibility with nephrologists, but it’s not the kind of brand moat that keeps competitors out.

Cornered Resource (Weak): Patents buy time, not permanence. Talent and experience matter, but they’re not exclusive. Ardelyx doesn’t control a scarce input that others can’t access.

Process Power (Weak-Medium): Ardelyx earned something valuable by surviving the CRL and winning an appeal: deep regulatory scar tissue, and the practical know-how to navigate a fight most companies never win. But it’s more accumulated learning than a repeatable, defensible process that compounds into a long-term advantage.

Overall Assessment: Ardelyx’s moats are weak to moderate. Its best edges are being early with a differentiated mechanism, building hard-won regulatory fluency through adversity, and having leadership with relevant renal commercial experience. But it’s operating in markets where well-resourced competitors can apply pressure for years—with bigger sales forces, deeper payer relationships, and far more room to spend.

XIII. The Bull vs. Bear Case

Bull Case

The optimistic thesis rests on a few big pillars. First is simple: management believes IBSRELA can become a blockbuster, projecting peak annual U.S. net sales of more than $1 billion. Second, XPHOZAH has started to look like a real wedge into a market that has long frustrated both patients and clinicians. Hyperphosphatemia on dialysis still carries major unmet need, and Ardelyx has said it sees peak annual U.S. net sales potential of $750 million for XPHOZAH.

Then there are the tailwinds. Kidney disease is growing into a global-scale health burden. A Nature Reviews Nephrology article published in April 2024 estimated that around 850 million people worldwide are living with kidney disease. And chronic kidney disease is projected to become the fifth leading cause of years of life lost by 2040. In other words, the addressable need isn’t shrinking.

The pipeline adds optionality. Ardelyx is advancing RDX013 for hyperkalemia, maintaining programs in metabolic acidosis, and has potential label expansion paths. Even the smaller signals matter here: the FDA’s Orphan Drug Designation for pediatric hyperphosphatemia gives the company another potential lane to pursue.

Finally, there’s the takeout angle. A company with two approved first-in-class products, a growing commercial footprint, and hard-earned nephrology expertise could be a logical bolt-on for a larger pharma player trying to deepen a cardiorenal franchise.

Bear Case

The cautious thesis starts with the most obvious mismatch: who Ardelyx is up against. Lokelma was originally developed by ZS Pharma, which AstraZeneca acquired in 2015 for approximately $2.7 billion. Competing in a chronic-care market against AstraZeneca’s sales force, payer leverage, and marketing budget is a grind—and it’s a grind where smaller companies can get worn down.

Execution risk is also real, and Ardelyx has lived it. IBSRELA was approved in 2019 but didn’t launch in the U.S. until 2022. XPHOZAH launched faster, but sustaining momentum and taking share from entrenched prescribing habits usually requires years of consistent investment, not quarters.

Profitability is another pressure point. Even with $319 million in 2024 revenue, Ardelyx still reported a net loss. That doesn’t mean the model can’t work—but it does mean cash burn and the possibility of future dilution remain part of the story.

Reimbursement is the other knife fight. Dialysis care is heavily shaped by government coverage, which creates persistent pricing pressure and makes formulary access a gating factor, not a footnote.

And the moat question doesn’t go away. Tenapanor’s early adoption—about 15% of eligible patients in its first year—is a strong start. But it also implies the harder part is still ahead: convincing the other 85% to change therapy in a market where “good enough” incumbents and established routines have decades of inertia.

XIV. Lessons for Founders & Investors

Ardelyx isn’t just a biotech comeback story. It’s a case study in what it takes to survive in capital-intensive, heavily regulated industries—where “being right” scientifically doesn’t guarantee you’ll be rewarded commercially, or even allowed to compete.

Persistence Through Failure: Two FDA rejections in a row would have ended most companies. Ardelyx treated the first “no” as the start of a process, not the end of one. It appealed, pushed the dispute up the chain, got the question put in front of outside experts, and ultimately changed the outcome. The initial rejection of XPHOZAH was a gut punch. The approval in 2023 reshaped the company’s future.

Partnership Trade-offs: The AstraZeneca chapter shows the double-edged sword of partnering. Ardelyx got early cash and validation, but it also gave up control. When priorities diverged, Ardelyx decided speed and focus were worth the price—and it paid to reclaim its own drug. The takeaway is blunt: partnerships are financial and strategic instruments, not fairy tales. Structure them like it.

Capital Allocation Discipline: After the rejection, Ardelyx did what survival demanded: it cut about a third of its workforce, raised money through at-the-market equity sales, and added debt financing. None of that was fun. All of it bought time. In biotech, time is everything, because time is what lets you stay alive long enough for the next data readout, the next meeting, the next decision. Cash is oxygen.

Regulatory Strategy Matters: The win wasn’t just “keep knocking until someone opens the door.” Ardelyx navigated the FDA’s internal pathways, elevated the disagreement to the right level, and helped frame the question in a way that could be debated by clinical experts. In other words, regulatory competence became a core capability—not an afterthought to the science.

Market Size vs. Competitive Position: Big markets can be mirages. IBSRELA went after a massive IBS-C opportunity, but adoption was hard in a crowded category with entrenched incumbents. What matters isn’t just how many patients exist. It’s whether you can actually win mindshare, access, and shelf space.

Science Alone Isn’t Enough: Even three successful Phase 3 trials didn’t guarantee an initial approval. Strong data is table stakes. The harder work is aligning to regulators’ expectations, telling a coherent clinical story, and navigating the bureaucracy that ultimately decides what “clinically meaningful” means.

XV. Epilogue: What's Next for Ardelyx?

As 2025 unfolds, Ardelyx is staring down the challenge that hits every biotech that survives long enough to “make it”: graduating from comeback story to durable company.

“In 2025, we will be focused on our strategic priorities: Maintaining our growth momentum, building a pipeline and delivering a strong financial performance.”

Translated into day-to-day reality, the priorities are straightforward and unforgiving. Keep pushing IBSRELA toward the blockbuster ambition the company has laid out. Keep scaling XPHOZAH’s launch from “strong first year” into sustained, repeatable prescribing. Keep moving pipeline candidates forward, so the company isn’t living or dying on two products. And keep tightening the financial model until “growing revenue” turns into “generating profit.”

Internationally, the playbook remains partnership-led. The tenapanor New Drug Application filing in China through Fosun Pharma is the kind of milestone that can quietly matter a lot—because if it converts into approval, it opens a large market without Ardelyx having to build a full commercial organization there.

And then there’s the question that always hangs over a successful small biopharma: does it stay independent, or does it get bought? With two approved products, growing sales, and a now-proven ability to navigate—and even reverse—regulatory outcomes, Ardelyx is the kind of asset larger companies look at when they want to deepen a cardiorenal franchise. Whether Ardelyx sees its future as a standalone specialty pharma company, or remains open to strategic alternatives, will shape what this story becomes next.

What keeps management up at night is the same list that keeps every small specialty pharma team up at night: competitors with deeper pockets, payers with leverage, the inevitability of patent cliffs, and the constant pressure to build enough pipeline depth before the current products mature.

Zooming out, the macro backdrop is only getting louder. Cardiorenal disease is becoming one of the defining opportunity sets in pharma. With around 850 million people globally living with kidney disease, and chronic kidney disease projected to become the fifth leading cause of years of life lost by 2040, the need for better therapies isn’t going away.

Which is what makes Ardelyx’s arc feel so resonant. It’s inspiring because persistence, scientific conviction, and strategic pivots can turn even an FDA “no” into a commercial “yes.” It’s also a cautionary tale, because approval is only the right to compete—and in specialty pharma, the competition never lets up.

XVI. Key Metrics to Track

If you’re following Ardelyx as an investment, the story has moved past “will they survive?” and into a much more practical question: can they keep building a durable, profitable specialty pharma business? Three metrics tend to tell you that answer before the headlines do:

-

Quarterly Revenue Growth Rate (XPHOZAH and IBSRELA): These are still early in their commercial lives, so the slope matters more than the snapshot. Steady quarter-over-quarter growth is a sign the products are earning real prescribing habits and access. A meaningful slowdown is often the first hint of tougher competition, payer friction, or a launch that’s starting to run out of easy wins.

-

Gross-to-Net Discount Trends: What Ardelyx lists on paper and what it actually collects after rebates and discounts are two different numbers. The gap between them is a live read on payer leverage, formulary placement, and how much pricing power the company really has. If gross-to-net keeps widening, it can foreshadow margin pressure even if top-line sales look healthy.

-

Cash Burn and Runway: Ardelyx has come a long way, but until profitability is consistently in the rearview mirror, cash is still the ultimate constraint. Track quarterly cash usage relative to what the company guides, and pay close attention to financing choices—especially equity raises that could dilute shareholders.

And that’s where we leave it, for now. Ardelyx started in 2007 as a contrarian scientific idea: keep the drug in the gut, and keep systemic side effects out of the equation. Since then, it’s been through partnership whiplash, an FDA saga that nearly ended the company, and a hard-earned commercial comeback. The next chapter—whether it’s scaling as an independent, getting acquired into a larger cardiorenal franchise, or fighting off new competitive pressure—will be written in these numbers.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music