Appian Corporation: The Low-Code Revolution

I. Introduction and Episode Roadmap

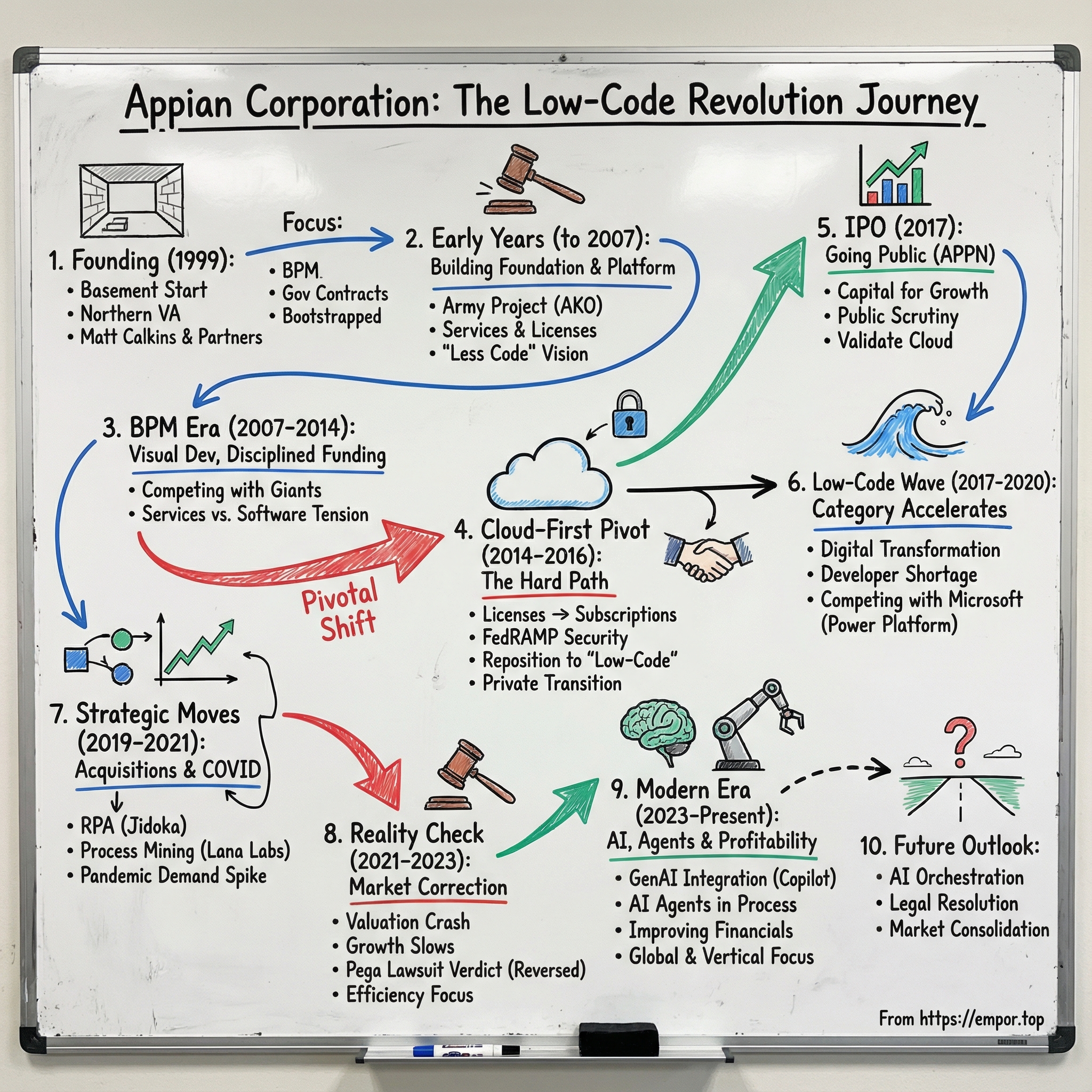

Picture a basement in Northern Virginia in the summer of 1999. Four young men—all fresh from MicroStrategy, an enterprise analytics company that had turned early employees into millionaires—huddle around a makeshift office and a blank sheet of paper, sketching a plan that would take more than two decades to fully become what they imagined.

Matt Calkins was 26. He left MicroStrategy and co-founded Appian with three partners. The Y2K clock was ticking. The dot-com bubble was swelling. And in tech, the mood was unmistakable: this wasn’t just another cycle. It was a permanent reset.

Appian didn’t start out sounding like a revolution. In the early days, it looked like the kind of company you’d expect to find in Northern Virginia at the turn of the millennium: consulting work, government contracts, and early business process software. But from that basement, Calkins scaled Appian into the most successful software IPO of 2017—while raising just $10 million of outside capital. In a world where enterprise software companies routinely burn hundreds of millions before they ever see a public market, that kind of capital efficiency is almost an anomaly.

Fast forward to today: Appian is headquartered in McLean, Virginia, and sells a cloud platform for building enterprise applications. It competes in low-code development and process automation categories—business process management and case management, and more recently, process mining. In 2024, the company generated $368.0 million in cloud subscription revenue, up 21% year over year. Total revenue reached $617.0 million, up 13% versus 2023.

So here’s the deceptively simple question at the center of this story: how did a government- and services-oriented firm transform into a pure-play platform company—and end up positioning itself at the intersection of the low-code wave and the emerging world of AI agents? The answer runs through strategic pivots that brought real existential risk, a lawsuit that produced the largest verdict in Virginia court history, and a founder-CEO who thinks about competition with the precision of a world-class board game designer.

Along the way, Appian becomes a case study in the hardest parts of enterprise software: making the brutal shift from services and licenses to subscriptions, catching the right technology wave without getting pulled under, competing against distribution giants like Microsoft and Salesforce, and grappling with the uncomfortable possibility that automation platforms might be either a durable category—or a stepping stone to something AI eventually subsumes.

If you’re watching Appian as a business, three metrics matter most. First: cloud subscription revenue growth, the clearest signal of whether the platform is still winning in a crowded market. Second: cloud subscription revenue retention, a measure of how sticky Appian is once it lands inside a big enterprise. And third: the path to sustained profitability—because for most of its modern history, Appian has prioritized building the platform over optimizing for margins.

II. Founding Context and Early Years (1999-2007)

Matt Calkins grew up in Mill Valley, California. He graduated from Dartmouth in 1994 with a degree in economics—and he didn’t just graduate, he finished at the very top of his class in the major.

But the most revealing line on his résumé isn’t “economics.” It’s “board game designer.”

Calkins has written several award-winning games, won a “Wargame of the Year” honor, and later finished third at the 2012 World Boardgaming Championships. It sounds like trivia until you realize what board games actually reward: building systems, stress-testing rules, anticipating how competitors will react three moves ahead, and finding the non-obvious path through a constrained map. That’s also a pretty good description of trying to win in enterprise software—especially when your competitors are bigger, better funded, and already inside your customer’s stack.

After Dartmouth, Calkins joined MicroStrategy. He rose to become director of the Enterprise Product Group, working there from 1994 to 1999, and later serving on the company’s board from 2005 to 2014. In the mid-’90s, MicroStrategy was a rocket ship riding the early business intelligence wave, culminating in a spectacular IPO that minted fortunes for early employees. Then came the other side of that lesson: an accounting scandal and a stock collapse in 2000. For Calkins, it was a front-row seat to both the upside of enterprise software and the consequences of getting ahead of reality.

In 1999, he and three colleagues—Michael Beckley, Robert Kramer, and Marc Wilson—decided to start something of their own. Appian Corporation was founded on August 17, 1999, in McLean, Virginia. Early on, they built software tools and did real work for real customers, including an intranet portal for the U.S. Army. From the start, Appian positioned itself around business process management, or BPM: the idea that the bottleneck in big organizations wasn’t a lack of software, it was the chaos of how work moved—or didn’t move—between people and systems.

They named the company “Appian” for the Appian Way, the Roman road built in 312 BC. That wasn’t just a clever historical reference. It was a statement of intent. Roads are infrastructure: they connect things, they standardize movement, and they enable commerce at scale. The founders weren’t trying to ship one killer app. They wanted to build the path other work would travel on.

And 1999 was the most paradoxical moment possible to attempt it.

It was the best time because enterprises were in a spending frenzy. Y2K deadlines were forcing modernization. Optimism was everywhere. Capital was cheap. Buyers were eager to believe that software could finally make their organizations run cleanly.

It was also the worst time because the dot-com bubble was distorting expectations. Every company was supposed to grow impossibly fast, and business models didn’t have to make sense—until they suddenly did, and the market punished anyone who’d built their plan on fantasy.

Appian, in its earliest years, took a different path. The founders largely bootstrapped the company, investing their own capital and earning their way forward. That grounded the business in something that mattered more than hype: customer demand.

By 2001, Appian landed one of the most credibility-building projects a young enterprise company could get. It developed Army Knowledge Online, described at the time as “the world’s largest intranet.” That work did more than bring in revenue. It pulled Appian deep into the government ecosystem—an environment where security, compliance, and reliability aren’t features, they’re table stakes. It also trained the company to live in the land of complex workflows, where “edge cases” are the actual case.

There’s another thread from this period that’s easy to overlook, but it shaped everything that came later: geography.

Calkins came to Northern Virginia right out of college, and Appian never left. The headquarters stayed in the same tight orbit. All of the company’s code was developed there. The board members came from the region. Even the funding came from that region. That’s not how most tech stories go. Most companies that want to be “the next big thing” eventually migrate to Silicon Valley.

Appian didn’t. And in hindsight, that stubbornness was part of the strategy. Northern Virginia meant proximity to the federal government—a massive, consistent customer base. It meant a cost structure far below the Bay Area. And culturally, it meant pragmatism. This wasn’t a move-fast-and-break-things company. It was a build-it-right-and-make-it-work company.

The early business model reflected that reality. Appian sold software licenses and delivered a lot of services alongside them—the classic “pizza box” enterprise model. Customers paid big upfront fees for perpetual licenses, then paid more for implementation, customization, and maintenance. This created real revenue and could be profitable, but it came with a hard ceiling: to grow, you had to hire. Every new deal demanded more people, and every deployment had a new set of bespoke requirements.

At the same time, the product itself was steadily becoming something more interesting than BPM as it was traditionally sold. Appian spent the early 2000s building what would become the Appian Platform: visual development, faster deployment, and “less code” long before “low-code” became a category. By the mid-2000s, the platform could model, deploy, and manage complex workflows without requiring armies of programmers for every change.

If you want the key takeaway from this era, it’s this: Appian was quietly compounding advantages.

Government work gave it credibility in high-stakes environments. Consulting embedded the team in the messy reality of how enterprises actually function. And the platform work built durable intellectual property. Appian didn’t look like a breakout software company yet—but it was laying the foundation for one.

III. The BPM Era and Building the Foundation (2007-2014)

Business Process Management software solved a very real problem. Big organizations don’t run on apps; they run on processes—claims, compliance, onboarding, employee requests, procurement. And in most enterprises, those processes were a messy relay race: five different systems, a few spreadsheets, a pile of PDFs, and an approval chain nobody fully understood. BPM’s promise was straightforward: map the work visually, automate the repeatable parts, and shine a light on where everything got stuck.

It was also a knife fight of a market. Pega had been around since the early ’80s and had deep enterprise roots. IBM, Oracle, Software AG, and Tibco all had their own BPM suites, each with a different angle—rules engines, integration, analytics—but all aiming at the same budgets and the same senior buyers.

Appian’s wedge was speed. While many competitors expected months of implementation led by specialized consultants, Appian sold a different idea: weeks, not quarters. And instead of requiring deep technical expertise for every change, Appian leaned into visual development so business analysts could participate without constantly queueing behind IT. The industry didn’t call it “low-code” yet, but the instinct was already there: make building enterprise software feel more like assembling than coding.

Appian’s funding story during this period also revealed how unusually disciplined the company was. In 2008, it raised $8 million. Then, in 2014, it raised $36 million in a deal led by New Enterprise Associates. But the most important detail is what that money was—and wasn’t. From 1999 until 2008, Appian ran for nearly a decade without significant outside investment. And even after 2008, most of the capital didn’t go into the company’s bank account. In total, Appian raised more than $47 million dating back to 2008, but only about $10 million of that was primary capital for the business. NEA’s roughly $37.5 million investment in 2014 was a secondary transaction, meaning they bought shares from employees.

That’s a very different kind of venture deal. Primary funding usually comes with an implicit mandate: hire fast, spend fast, grow fast. A secondary transaction does something else—it gives liquidity to the people who already built the thing, without forcing the company to radically change its burn rate or strategy. Appian’s employees got paid. Appian didn’t have to turn into a money furnace.

Operationally, the platform was gaining momentum. In 2014, total software license bookings for Appian’s BPM-based Application Platform increased by 63 percent over the prior year, including a 111 percent increase in subscription-based software license bookings. Appian signed 41 new-name customers that year, including multi-million dollar deals in financial services, telecommunications, and healthcare, plus significant deals across insurance, pharmaceuticals, retail, education, and government. The takeaway wasn’t just growth—it was range. Appian wasn’t a one-industry tool. It could attach to complex workflow pain almost anywhere, and it was expanding inside existing accounts as it proved value.

But the business still carried the classic enterprise tension: services helped you win, and services helped customers succeed—but services didn’t scale the way software did. Appian’s professional services margins were healthy by industry standards, and the work created an invaluable feedback loop: consultants saw the real-world mess, then the product got better. Still, anyone looking at the model could see the eventual crossroads. If Appian wanted to become a true platform company, it would have to keep shifting the mix toward subscription revenue and away from people-intensive delivery.

Through all of this, Calkins was unusually explicit about what he was trying to build. “We’ve been building Appian for 22 years,” he reflected later. “No plan survives 22 years, but from the beginning, I wanted to build an organization that contributed both financially and culturally. It was very important to me that we’d be a member of the community and a good part of the lives of those who came into contact with us.”

He also pushed a particular operating philosophy: “I still try to encourage Appian to have an open culture where anybody can share their thoughts and disagree with anybody else. I think a company’s DNA is determined by the first 1,000 or so people it hires.” For a long time, he treated hiring as a core part of the CEO job, doing hundreds of interviews a year.

That founder involvement mattered because enterprise software has gravity. Left unchecked, it tends to drift toward an aggressive, quarter-to-quarter sales culture. Appian developed differently—more engineering-led, more customer-obsessed, and more oriented toward long-term relationships than short-term deal mechanics.

And then there was the government thread, quietly getting stronger. In 2010, Appian Cloud was accredited with Federal Information Security Management Act (FISMA) low-level security by the U.S. Education Department. In 2013, it received FISMA Moderate Authorization and Accreditation from the General Services Administration. These certifications weren’t flashy, but they were consequential: they validated Appian’s security posture and positioned the company for deeper federal adoption—an advantage that would compound over time.

IV. The Inflection Point: Cloud-First Pivot (2014-2016)

Between 2014 and 2016, Appian hit the kind of fork in the road that can end an enterprise software company—or remake it. The industry was in the middle of a full-scale delivery-model shift. Salesforce had already shown that cloud software could run mission-critical workloads. Workday was taking on Oracle and SAP in the heart of the back office. ServiceNow was turning IT service management into a cloud-first category. The direction of travel was unmistakable: subscriptions were becoming the default.

For Appian, saying yes to that future meant saying no to what had kept the business healthy for years. Perpetual licenses brought in big upfront checks and immediate revenue recognition. Subscriptions spread that same customer value over time, which makes your near-term financials look like they’re shrinking even when demand is growing. Services were profitable and familiar. Building and operating cloud infrastructure would drag margins down before it ever lifted them. The math was unforgiving: do the right strategic thing, and the company would look worse on paper for a while.

Plenty of Appian’s peers tried to split the difference—keep the license engine running, dabble in cloud, protect the old P&L. And a lot of them got stranded: neither fully cloud-native nor able to stop the bleeding as buyers shifted their expectations. Appian, with Calkins at the wheel, chose the hard path: commit.

That commitment showed up in the trajectory. Appian’s subscription software license revenue had been growing rapidly, compounding at 66 percent annually since 2012. And in 2015, total company revenue grew 22 percent year over year. The message wasn’t that the transition was painless—it wasn’t—but that Appian was building real momentum in the direction it wanted to go.

It also started building the global footprint and infrastructure to match. In 2015, Appian expanded its direct presence with new offices in Switzerland and Italy, adding to offices in London, France, Germany, The Netherlands, Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane. Behind the scenes, it expanded its data center network in partnership with Amazon Web Services. By the end of 2015, Appian was operating across multiple regions in the U.S. and internationally, including Brazil, Ireland, Germany, Singapore, and Australia.

Then came a credential that mattered enormously—especially given Appian’s government roots. In 2015, Appian Cloud received FedRAMP compliance authorization. FedRAMP isn’t a badge you slap on a website; it’s a long, grueling process built around documentation, third-party assessment, and continuous monitoring. But once you have it, it changes what’s possible. For Appian, it opened the door to federal cloud deployments at a moment when agencies were starting to move serious workloads out of on-prem environments.

The product itself had to change, too. Moving to cloud wasn’t a simple hosting decision—it meant reworking large parts of the platform. Multi-tenancy, where multiple customers run on shared infrastructure, forces different architectural tradeoffs than single-tenant deployments. Security and isolation have to be designed in from the start. Scalability becomes a daily requirement, not a theoretical one. Upgrades stop being a once-a-year event and become something the vendor must manage continuously.

That shift also reframed the value proposition. Cloud BPM promised strategic process improvement, lower technology costs, and tighter alignment between IT and business goals. Appian leaned into that story publicly, including at its 2014 Appian World user conference, where Amazon Web Services highlighted cloud solutions for business process excellence. The platform wasn’t just automating workflows anymore; it was positioning itself as the faster path to modernizing how enterprises actually operate.

The commercial model changed along with the technology. Appian moved to subscription-based pricing with all capabilities included, priced per user per month, with tiers based on usage levels. It simplified the buying conversation—no more negotiating a maze of modules—but it also forced Appian to price around platform-wide value rather than feature-by-feature checklists.

And critically, Appian made this pivot while still private. Public markets demand smooth quarters and punish any hint of deceleration. A company switching from licenses to subscriptions almost inevitably shows a period of apparent weakness while the new engine ramps. Private, Appian could absorb that dip in reported metrics in exchange for long-term positioning. Public, the pressure might have pushed the company into a slower, half-measure transition—the kind that looks safer until it quietly becomes fatal.

Finally, there was a narrative shift that mattered more than it might sound. Appian began repositioning from “BPM” to “low-code application platform.” BPM was a mature category with entrenched competitors and preconceived buyer expectations. “Low-code” described something broader: not just automating processes, but building applications quickly across many use cases. That repositioning wasn’t only marketing—it was a way to compete on a different map, outside the shadow of legacy BPM giants, and claim leadership in an emerging category before the category fully formed.

V. The IPO and Going Public (2017)

By 2017, Appian had done the hardest part of its transformation in private: it had bet the company on subscriptions and cloud delivery, and it had lived through the awkward financial optics that come with that shift. Now came the next inflection point—one that would put Appian’s strategy, numbers, and narrative under a bright, unforgiving spotlight.

In May 2017, Appian priced its initial public offering: 6,250,000 shares of Class A common stock at $12.00 per share. The stock began trading on the NASDAQ Global Market on May 25 under the ticker “APPN,” and the offering closed on May 31. The deal raised $75 million for the company, right in the middle of the proposed $11 to $13 range.

The bankers were as blue-chip as it gets—Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs & Co. LLC, and Barclays as book-running managers. That lineup conveyed credibility. The size of the raise conveyed something else: Appian wasn’t going public because it was running out of money. It was going public because it wanted more fuel—and a larger stage.

Investors responded immediately. On its first day of trading, Appian’s stock jumped, closing at $15.01 after pricing at $12. That first-day pop signaled demand. It also hinted the IPO may have been set a little conservatively—an old, familiar dance between companies that want a clean debut and buyers who want upside on day one.

What Appian was selling on the roadshow wasn’t just “BPM, but better.” It was a broader ambition: a low-code platform that could sit in the same conversations as the giants. Appian was candid about the competitive set it was running into—Salesforce and ServiceNow at the top of the list, with IBM and Oracle in adjacent territory. That comparison was both accurate and bold. Those companies were enormous, deeply entrenched, and already living inside the very enterprises Appian needed to win.

The growth story was real, if not hypergrowth. Appian generated $132.9 million in revenue in 2016, up from $111.2 million in 2015 and $89 million in 2014. It was steady, healthy momentum—enough to support the case that the cloud transition wasn’t theoretical anymore.

But the public market lens was sharper than the private one. Appian had reportedly been valued above $1 billion in the prior year, earning the “unicorn” label. The IPO valuation landed closer to $700 million. That gap wasn’t a fluke—it reflected skepticism about how fast Appian could grow, and how defensible that growth would be in a world where competitors could bundle, cross-sell, and outspend almost indefinitely.

Wall Street’s reaction was cautiously optimistic. Analysts liked the shift toward recurring revenue, but they worried about the services component. Professional services can be necessary to get enterprise platforms deployed, but it’s a tougher mix for software-style margins—and it scales with headcount. There were also questions about customer concentration, with meaningful exposure to government and financial services bringing both strength and risk.

Still, the timing was logical. The software market was in good shape. Appian’s cloud transition was far enough along to be legible to investors. And the company wanted capital to press the advantage: build sales capacity, invest in R&D, and raise its profile in a category that was about to get very crowded.

VI. The Low-Code Wave Builds (2017-2020)

Calkins had a clean way to explain what Appian was really selling. “Low-code means drawing an application like a flowchart instead of coding it line by line,” he said. In other words: stop treating software like artisan craft, and start treating it like system design. If you can model the work visually, you can change it visually. And that, in his telling, made organizations dramatically faster—sometimes an order of magnitude faster—at defining and refining how they operate.

The timing was perfect, because a few big forces were crashing together.

First came the digital transformation mandate. Every enterprise suddenly had the same problem statement: we need to become a technology company. The catch was that most of them didn’t have the engineering bench to do it.

Second was the developer shortage, which was less a headline than a lived reality. Skilled programmers were expensive, scarce, and already booked. Even companies willing to spend couldn’t always hire their way out of the backlog.

Third was the speed of the world itself. Markets shifted faster. Regulations changed more often. Customers expected new experiences continuously. The old enterprise rhythm—spec a project, build for a year, launch, then patch—couldn’t keep up.

That’s where the “citizen developer” idea took off. The pitch was seductive: let business analysts, operations teams, and power users build the simpler apps themselves, so professional developers can focus on the hard, high-risk work. Low-code platforms weren’t just tools; they were an attempt to expand the labor pool for software creation.

Legacy modernization was the other huge tailwind. Most big companies still ran on decades of accumulated systems: mainframes, client-server apps, and custom code that nobody wanted to touch. Rewriting all of it from scratch was usually too expensive, too risky, and too politically painful. Low-code offered a more incremental path: build modern workflows and interfaces on top of legacy systems, and migrate functionality over time without blowing up the core.

The result was a category that started to feel inevitable. Forecasts began projecting the low-code and no-code market growing rapidly, with some pointing to a $101.7 billion market by 2030.

Appian used this moment to keep widening what the platform could do. It added AI and machine learning features aimed at things like intelligent document processing, prediction, and optimization. It pushed deeper into automation through RPA integrations, so customers could automate tasks that still required interaction with older systems. It leaned into mobile-first development, making sure apps worked cleanly on phones and tablets. And it packaged more industry-specific solutions—templates and accelerators for financial services, government, healthcare, and insurance—so customers could get to value faster.

But the deeper Appian pushed into “platform,” the more it ran into a fundamental tension of the category. In process-heavy enterprise work, Appian and Pega were both strong, especially for automation and orchestration. Appian could deliver a compelling no-code experience, but it wasn’t always as immediately approachable as simpler tools like Microsoft Power Apps. That tradeoff—power versus ease—kept showing up in product decisions and in competitive bake-offs.

And the competition wasn’t letting up. OutSystems built a reputation for complex, enterprise-grade low-code applications. Mendix differentiated with collaborative development and customization, and it was later recognized as a leader in Gartner’s Magic Quadrant for Enterprise Low-Code Application Platforms in 2024. Meanwhile Microsoft Power Apps came with the most dangerous advantage of all: distribution. For many companies, it wasn’t just a product evaluation—it was already sitting inside the Microsoft ecosystem they’d standardized on.

That Microsoft threat deserved its own paragraph because it changed the economics of the fight. Power Apps was often more affordable for smaller and mid-scale use cases, and Microsoft could effectively make low-code feel “free” by bundling the Power Platform alongside Office 365. For Appian, that wasn’t just a competitor with good features. It was a competitor that could change the buyer’s default option before Appian even got in the room.

So Appian leaned into a go-to-market strategy that matched its strengths: enterprise sales, not self-serve. Instead of trying to spread virally from a single department, it targeted senior executives and enterprise-wide programs. That meant longer sales cycles, but it also meant bigger deployments, deeper embedding in critical processes, and relationships that could compound over time.

The recurring challenge through this whole period stayed the same: build something simple enough for citizen developers to use, but powerful enough for enterprise architects to trust with mission-critical work. If low-code was going to become the new way enterprises built software, it had to be easy when the problem was easy—and still formidable when the problem wasn’t.

VII. Key Strategic Moves and Inflection Points (2019-2021)

The RPA Integration Bet

By 2019, Appian had a clear strength: orchestrating work. It could route tasks, manage approvals, handle exceptions, and keep humans and systems moving in sync. But there was still a stubborn gap in the real world. Lots of enterprise software—especially the older stuff—didn’t have clean APIs to connect to. The work still happened through screens, copy-paste, and “don’t touch that system, it’s fragile.”

That’s exactly what Robotic Process Automation was built for. RPA didn’t modernize old systems; it worked around them, using software “robots” to click buttons and move data the way a human would. So the combined thesis was simple and powerful: low-code plus RPA gets you much closer to true end-to-end automation than either one can on its own.

On January 7, 2020, Appian put that thesis into action by acquiring Novayre Solutions SL, the company behind the Jidoka RPA platform. Jidoka had earned top marks on Gartner Peer Insights, with more than 50 reviews, and Appian now had the option to make RPA a native part of its platform story, not just an integration checkbox.

Calkins framed it as a way to push Appian’s lead in low-code automation: “Appian is extending our lead in low-code automation by adding RPA. Together, the products enable end-to-end process orchestration where humans, software robots, and AI all work together in a coordinated way.”

Strategically, this was a real fork in the road: partner or own. Appian could have leaned on the major RPA specialists—UiPath, Automation Anywhere, Blue Prism—and stayed focused on orchestration. Instead, it chose to own the capability. That promised tighter integration and a simpler buying experience, but it also signed Appian up for the ongoing grind of keeping an RPA product competitive while the market raced ahead. And it was a market with real momentum—Forrester expected RPA to reach $12 billion by 2023.

COVID-19 Acceleration

A few months later, the world hit fast-forward.

COVID-19 forced organizations—especially government agencies—to rethink how work got done. Plans that used to be three-year roadmaps became three-week emergencies. And the companies that were still dependent on paper, in-person approvals, and manual handoffs suddenly discovered that “business as usual” had disappeared overnight.

In March 2020, Appian responded by releasing a free COVID-19 Response Management application for enterprises and government agencies. It was classic Appian positioning: speed as the product. The app could be configured and adopted within two hours, serving as a central command center to help safeguard employee health and safety by tracking health status, location, travel history, and incident details.

The broader point was bigger than one app. Stay-at-home orders pushed massive parts of the workforce remote with little notice, and the weakest link wasn’t infrastructure—it was process. Organizations that relied on manual, paper-based workflows were hit hardest, and the pandemic turned automation from a nice-to-have into a requirement.

Appian’s numbers showed the shift in urgency. Cloud subscription revenue growth accelerated from the high-20% range to more than 40% year over year. Investors noticed too: Appian’s stock climbed to an all-time high closing price of $235.24 on January 27, 2021.

Process Mining Acquisition

Then, in August 2021, Appian made another move that fit a pattern: fill in the missing pieces around orchestration.

It acquired the process mining company Lana Labs. If RPA helped Appian automate work inside legacy systems, process mining helped it answer a different question: what work is actually happening in the first place?

Process mining analyzes system logs to reconstruct the real flow of a process—the actions people take, the sequences they follow, and where things slow down, break, or get rerouted. It’s the difference between the process you think you run and the process your data proves you run.

Calkins pointed out the limitation of many process mining tools: they could surface insights, but they couldn’t act on them. Appian’s bet was that the combination mattered. Discover what’s happening, then use workflow and automation to change it.

With Lana Labs, Appian could now tell a more complete “discover-design-automate” story. Process mining identifies bottlenecks and inefficiencies. The low-code platform designs the fix. And automation—now including RPA—executes it. In a market increasingly crowded with point solutions, Appian was trying to be the integrated system that connected the whole loop.

VIII. The Reality Check and Market Correction (2021-2023)

The Valuation Crash

The euphoria didn’t last.

Starting in late 2021 and accelerating through 2022, the market flipped on growth software. Rising interest rates, inflation fears, and the unwind of pandemic-era “digital transformation at any cost” crushed valuation multiples across cloud.

Appian felt that whiplash in public. The stock’s all-time high closing price was $235.24 on January 27, 2021. It later hit a 52-week low of $24.00. Peak to trough, that was roughly a 90% drawdown—painful, but very much in line with what happened to a whole generation of high-multiple software companies.

And while the multiple compression was an industry-wide event, Appian also had its own questions to answer. Growth slowed—cloud subscription revenue decelerated from the pandemic highs above 40% year over year down into the mid-20% range. That brought the inevitable follow-ups: was low-code demand normalizing, were deal cycles stretching, was Microsoft’s bundling starting to bite, and could Appian get to durable profitability without losing its product edge? Customer acquisition costs stayed elevated. The path to sustained profitability still looked like work in progress.

The Pega Lawsuit Verdict—and Its Reversal

In Appian’s world, there’s always been one rival that matters a little more than the rest: Pegasystems. They’ve been competing for years as two of the most visible names in high-end process automation.

Then the rivalry spilled into court.

On May 9, 2022, a unanimous jury found that Pega violated the Virginia Computer Crimes Act by infiltrating Appian. A unanimous jury also found that Pega misappropriated Appian trade secrets. The jury and judge described Pega’s conduct as “willful and malicious,” and the jury awarded Appian $2.036 billion—an amount Appian believes is the largest damages award in Virginia state court history.

At the center of the case was a contractor who, internally at Pega, was referred to as a “spy.” According to the case, the contractor helped Pega produce dozens of video recordings of Appian’s development environment. Those recordings and related documents were then used to create competitive materials and to train Pega’s sales force to compete more effectively. Inside Pega, the effort was later labeled “Project Crush.” At one point, a Pega employee reviewing the materials wrote: “we should never lose to Appian again!”

Calkins has said he learned the extent of Project Crush in spring 2020—nearly a decade after the spying began—after a former employee tipped him off. “I was amazed not only by the audacity of it, but by how long it had been running,” he said.

But the verdict didn’t settle the matter. Pega argued the trial was error-filled and that it was improperly limited in how it could defend itself. The Court of Appeals of Virginia agreed, and on July 30, 2024, it reversed the jury’s 2022 trade secrets verdict and ordered a new trial.

The case then moved to Virginia’s highest court. On March 7, 2025, the Supreme Court of Virginia granted Appian’s request to hear its appeal of the Court of Appeals decision that threw out the verdict and ordered a new trial. The Supreme Court of Virginia also agreed to hear Pega’s arguments for why the case should be dismissed entirely.

So the litigation remains live—and it hangs over both companies. For Appian shareholders, the range of outcomes runs from “billions in damages” if the verdict is reinstated to “nothing” if the case is dismissed. That kind of binary, high-stakes uncertainty has likely been one more ingredient in the stock’s volatility.

Strategic Responses

As growth slowed and the market demanded profits instead of promises, Appian’s posture shifted. Management leaned harder into operational efficiency—without abandoning product investment.

The financial results show that turn. GAAP operating loss improved from $(108.0) million in 2023 to $(60.9) million in 2024. On a non-GAAP basis, Appian reported operating income of $10.2 million for full year 2024, compared to a non-GAAP operating loss of $(54.3) million the year before.

The playbook was what you’d expect from an enterprise platform trying to mature. Some of it was cost discipline. Some of it was revenue quality: improving sales and marketing efficiency by focusing more on expanding within existing customers rather than chasing new logos at any price. And while R&D spending continued, the emphasis increasingly tilted toward AI-related capabilities—features that, in theory, could justify premium pricing and keep Appian differentiated in a category where “good enough” was getting more crowded by the quarter.

IX. Modern Era: AI, Agents, and the Next Platform Shift (2023-Present)

Generative AI Integration

By 2023, the low-code category had a new accelerant: generative AI. And Appian moved quickly to make it feel native to the way people actually build on the platform.

In the 23.3 release in August 2023, Appian launched AI Copilot—a design assistant embedded directly inside Appian’s low-code development console. The promise was straightforward: use generative AI to speed up the tedious parts of building applications so teams can deliver new solutions faster.

Appian framed AI Copilot as part of the Appian AI Process Platform, positioned around an “enterprise-ready” architecture and a private AI strategy. In the initial release, the most tangible capability was also one of the most practical: AI Copilot could convert PDFs and other structured forms into clean, digital interfaces—turning a document you used to manually re-create into something you could actually deploy.

“Appian believes low-code and AI are a perfect match,” said Michael Beckley, CTO and Founder. “Appian’s AI Copilot demonstrates the natural advantages of this union by making its suggestions inside low-code design tools. Low-code is the perfect medium for AI to express application designs while ensuring humans can easily understand and refine AI creations through an intuitive and visual design environment.”

The Agentic Pivot

But Appian’s bigger point wasn’t “AI helps you build faster.” It was “AI helps you run better”—as long as you put it inside a governed business process.

That’s where the agent idea comes in. AI agents are autonomous systems designed to take on specific tasks inside a workflow. Appian’s approach shows up in Appian AI Skills, which let users design and deploy LLM prompts into their processes using low-code—turning AI into something orchestrated, monitored, and repeatable, rather than a standalone chatbot sitting off to the side.

Appian rolled out a slate of new AI capabilities aimed at practical enterprise use, including 11 new generative AI skills designed to function as AI agents in mission-critical processes, plus Enterprise Copilot, which it positioned as a way for users to get instant answers to questions.

In Appian’s product lineup, the pieces fit together like this. AI Copilot is the natural-language assistant inside applications: it can find information buried in documents, answer questions in context, summarize results, generate insights, and suggest actions. Composer is the app generation tool, designed to let business users create fully functional apps from natural language prompts and requirement documents. DocCenter focuses on intelligent document processing, using generative AI to extract data from documents accurately, securely, and at scale.

“In 2024, Appian demonstrated its ability to grow with increasing efficiency. We specialize in creating value with AI, by deploying it in a process. While others bring work to AI, we bring AI to work,” said Matt Calkins, CEO & Founder.

Recent Financial Performance

By late 2025, the numbers were telling a story that fit the strategy: steady cloud growth, improving efficiency, and real progress on profitability.

In the third quarter of 2025, cloud subscriptions revenue increased 21% year over year to $113.6 million, and total subscriptions revenue increased 20% to $147.2 million. Professional services revenue came in at $39.8 million, up 29% versus the third quarter of 2024. Total revenue was $187.0 million, up 21% year over year. Cloud subscriptions revenue retention was 111% as of September 30, 2025.

The quarter also marked a sharp swing in profitability. Appian reported GAAP operating income of $13.1 million, compared to an operating loss of $7.2 million in the same quarter the year before. Cash flow flipped, too: net cash provided by operating activities was $18.7 million, versus $8.2 million used in operations in the third quarter of 2024.

Looking ahead, for full-year 2025, Appian anticipated total revenue between $711.0 million and $715.0 million. Cloud subscriptions revenue was expected between $435.0 million and $437.0 million, representing year-over-year growth of 18% to 19%.

The customer base kept maturing in the direction Appian has always aimed for: large enterprises. As of December 31, 2024, Appian had more than 1,000 customers, focusing on organizations with over 2,000 employees and $2 billion in annual revenue. And its biggest customers were getting bigger: the number paying more than $1 million of annual recurring revenue increased from 110 in 2023 to 126 in 2024.

Partnership Ecosystem

Appian’s footprint was increasingly global. In 2024, 36.6% of total revenue came from customers outside the United States. The company operated in 16 countries, reflecting an international presence that had been building since the cloud pivot years.

The industry mix also showed where Appian’s platform resonated most: complex, regulated, process-heavy environments. Appian served financial services, government, life sciences, insurance, manufacturing, energy, healthcare, telecommunications, and transportation. In 2024, more than 77% of subscriptions revenue came from its key verticals—financial services, government, life sciences, and insurance.

X. Playbook: Business and Strategic Lessons

The Platform Pivot Playbook

Appian’s shift from a services-heavy BPM business into a cloud-first low-code platform is a useful template for anyone staring down the same kind of pivot—and wondering if they’ll survive it.

First, timing matters, but not in the simplistic “be first” way. Appian began its cloud transition around 2014–2015: late enough that Salesforce had already proven enterprises would trust mission-critical workloads to the cloud, but early enough that the low-code land grab hadn’t yet turned into a knife fight with every big platform company on earth. Move too early, and you spend years explaining the category. Move too late, and you’re trying to unseat incumbents who already have distribution on lock.

Second, staying private gave Appian room to do the economically painful thing. The move from licenses to subscriptions changes the shape of revenue recognition, and it almost always makes a business look worse before it looks better. In public markets, that “dip” is where strategies go to die—crushed under quarterly expectations and short-term sentiment. Private, Appian could absorb the headwinds without triggering a crisis of confidence every 90 days.

Third, the pivot required an actual decision, not a compromise. A lot of enterprise vendors tried to straddle both worlds: keep the perpetual license machine running while also “doing cloud.” In practice, that usually creates internal civil war. Sales teams gravitate toward whatever pays them faster. Engineering gets pulled in two directions. And the organization ends up maintaining the past while underinvesting in the future. Appian avoided the half-measure trap by committing.

Category Creation Versus Category Riding

Appian didn’t invent low-code. Visual development tools have been around for decades. What Appian did was recognize that separate forces were about to converge—cloud delivery becoming mainstream, the developer bottleneck becoming chronic, and “digital transformation” becoming a CEO mandate—and that the intersection of those trends would create real demand for rapid application platforms.

You can see that in the way Appian kept renaming the thing it sold. “Business Process Management” was accurate, but narrow and already crowded with legacy expectations. “Low-code” widened the aperture beyond process automation and put Appian in a faster-growing conversation. “Intelligent automation” and “AI process platform” are the next step—positioning the company for a world where workflows aren’t just automated, they’re augmented by models and agents.

The lesson for founders isn’t “create a category at all costs.” It’s that category leadership is often more valuable than category invention. If you can spot an emerging category with real tailwinds and credibly become one of the leaders, you get the upside without carrying the entire burden of market education.

Capital Allocation Discipline

Appian has made a total of 3 acquisitions. Peak acquisition years were 2020 with 2 acquisitions, and 2021 with 1 acquisition. Acquisition activity has occurred in 2 countries: Spain and Germany.

That restraint is unusual in enterprise software, where companies often try to buy their way into being a “platform,” stitching together dozens of point solutions and then spending years wrestling with integration. Appian’s pattern was different: build most things organically, and use M&A sparingly to fill specific gaps. The upside is coherence—one platform story instead of a portfolio of loosely connected products—and fewer distractions when the competitive landscape is already intense.

But discipline doesn’t eliminate the treadmill. Appian still has to keep investing just to remain competitive, especially when many rivals have far larger R&D budgets. In enterprise software, innovation isn’t a one-time breakthrough; it’s a permanent obligation.

Competing Against Hyperscalers

Microsoft’s Power Platform is the competitive threat that changes the rules of the game. Power Apps offers a standard plan where users pay $20 per user per month. This plan enables building and deploying an unlimited number of applications. Microsoft also offers a pay-as-you-go plan that allows paying per app.

But the real advantage isn’t the pricing menu—it’s the default distribution. Many enterprises already have Microsoft agreements that include Power Platform capabilities with little or no perceived incremental cost. So Appian isn’t just competing on features; it’s competing against the procurement logic of “why pay extra when we already have something bundled?”

Appian’s answer has been to aim where “good enough” breaks. Microsoft Power Apps can be excellent for simpler, departmental apps built quickly by citizen developers. Appian targets the places where enterprises get conservative: mission-critical processes, regulated environments, heavy governance requirements, security and compliance constraints, and complex orchestration across many systems.

And then there’s the “Switzerland” stance. Appian positions itself as a platform-agnostic automation layer that can integrate across AWS, Azure, and Google Cloud. For enterprises that don’t want their process layer tied to a single ecosystem, that neutrality becomes a real differentiator—especially as multi-cloud strategies become less theory and more operational reality.

XI. Porter's Five Forces and Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis

Porter's Five Forces

Threat of New Entrants: Medium-High

At the surface level, low-code looks easy to copy. Basic builders can be assembled quickly, plenty of startups have tried, and open-source alternatives keep showing up. Cloud infrastructure is cheaper and more accessible than ever, which lowers the upfront barrier to taking a swing.

But “basic” isn’t what enterprises buy. Enterprise-grade low-code means security certifications, real governance, reliability at scale, and the ability to survive audits. FedRAMP authorization, for example, isn’t a feature you ship—it’s years of investment and an ongoing compliance grind. And once Appian is embedded in production workflows, switching becomes painful enough that new entrants can’t just win on novelty.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Low

For most of Appian’s stack, suppliers don’t have much leverage. AWS, Azure, and Google Cloud are competing hard for enterprise workloads, and infrastructure has become effectively commoditized. Appian also controls its core IP, so it isn’t hostage to a single critical vendor for the platform’s differentiated value.

The one area to watch is AI. If the value in “AI features” accrues mostly to model providers like OpenAI or Anthropic, platform vendors risk becoming thin wrappers. So far, Appian has worked with AWS for model access, which helps it avoid getting locked into a single provider and preserves some negotiating flexibility.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: Medium-High

Appian sells to the toughest customers in software: large enterprises. They buy in big contracts, they negotiate hard, and they run structured procurement processes designed to force competition and drive down price. Alternatives are credible, and in a tighter macro environment, ROI scrutiny gets brutal.

But buyer power changes once Appian is entrenched. Replacing it can mean rebuilding applications, redoing integrations, retraining users, and risking disruption to mission-critical operations. Those switching costs don’t eliminate negotiation, but they do shift leverage toward the vendor over time—especially in expansions and renewals.

Threat of Substitutes: High

Appian isn’t just competing against other low-code platforms. It’s competing against the entire menu of “ways enterprises get software built.”

Traditional custom development is still the default if you have the talent and patience. Other low-code platforms offer similar promises. Hyperscalers can bundle adjacent functionality with broader cloud commitments. And in many situations, a vertical SaaS product that solves one problem well can look “good enough” versus committing to a platform.

Then there’s the emerging wildcard: AI coding assistants like GitHub Copilot and Cursor. If they keep shrinking the effort required to build and maintain conventional software, they can narrow low-code’s speed advantage—especially for teams that already have developers.

Industry Rivalry: High

This is a crowded, aggressive market with few easy wins. Competition shows up everywhere: feature velocity, pricing pressure, partner ecosystems, and the ability to get into accounts through distribution. Microsoft and Salesforce can bundle and cross-sell into customers they already own, which changes the economics of the fight before a competitive bake-off even starts.

Meanwhile, the AI arms race is consuming R&D budgets across the category. As capabilities converge, it gets harder to differentiate on features alone—and when differentiation weakens, pricing and distribution matter even more.

Hamilton's Seven Powers

Scale Economies: Limited

Appian benefits from software gross margins, but it doesn’t enjoy the kind of overwhelming scale advantage that makes competitors irrelevant. Hosting costs don’t collapse as customer count rises; multi-tenancy helps, but it’s not magic. And the services component is inherently less scalable, since services revenue still requires people to deliver it.

Network Effects: Moderate and Growing

Appian’s AppMarket, where developers share components and templates, creates some network effects: more builders lead to more reusable parts, which can make adoption easier for the next customer. The community is growing, and that ecosystem does matter.

But it isn’t a true, dominating network effect like a marketplace or social platform. One customer doesn’t automatically become more valuable because another customer joined yesterday.

Counter-Positioning: Historical Yes, Fading

For a time, Appian’s cloud-first, low-code approach was a strong counter-position against legacy BPM vendors like IBM and Oracle. Those incumbents were tied to perpetual licenses and on-prem deployments, and responding aggressively would have meant cannibalizing their own profit pools. That hesitation gave Appian room to run.

Today, the counter-positioning pressure points in the other direction. Microsoft and Salesforce can offer low-code capabilities bundled into software enterprises already buy, sometimes at little perceived incremental cost. Appian’s response—leaning into governance, security, and compliance in regulated, mission-critical use cases—is effective, but it’s more defensive than the earlier era’s offensive disruption.

Switching Costs: Moderate-High (Strongest Power)

This is Appian’s real moat. Once an organization builds core workflows on Appian, leaving means more than swapping tools. It can mean rewriting applications, rebuilding integrations, retraining users, and risking downtime or operational disruption. Process knowledge becomes encoded in the platform, and extracting it is expensive.

The limitation is obvious: switching costs protect you after you’ve won. They don’t help you win the next logo. Appian still has to land early and embed deeply before competitors do.

Branding: Weak-to-Moderate

Appian isn’t a consumer brand, and enterprise buyers don’t purchase low-code platforms for emotional resonance. Still, being seen as a “low-code leader” helps, and analyst recognition in Gartner and Forrester research can provide credibility in executive-level buying conversations. Calkins’s public thought leadership and Appian’s reputation in government and financial services also carry weight where trust and risk management matter.

But branding isn’t the engine of power here. Execution and outcomes are.

Cornered Resource: Weak

Appian doesn’t control a uniquely scarce input that competitors can’t access—no proprietary data asset that others can’t replicate, no exclusive distribution channel, no irreplaceable dependency. Talent is competitive but available.

The closest thing to a cornered resource is the founder himself: Calkins’s long-term orientation and strategic clarity are real advantages, but they aren’t an asset you can trademark or defend.

Process Power: Moderate

Appian has years of accumulated learning in how enterprises actually implement low-code: what fails, what scales, how governance breaks, and what reliability looks like at the sharp end. That operational knowledge is a genuine advantage.

But process power erodes in fast markets. Competitors learn. Best practices spread. And Microsoft and Salesforce, in particular, have deeper enterprise operating machinery overall.

Overall Assessment

Appian’s strongest power is switching costs: win the account, get embedded, and you become hard to dislodge. Behind that, it has meaningful process power and a counter-positioning story that used to be stronger than it is today.

The vulnerability is what Appian doesn’t have: overwhelming scale economies or deep network effects. That makes it harder to create separation in a market where giants can bundle and smaller players can undercut.

And looming over all of it is the AI-and-agents shift. If AI changes how applications get built and how processes get automated, the competitive map can reset. Powers that mattered in the low-code era may weaken, and new ones—around data, distribution, governance, and trustworthy automation—may decide the next decade.

XII. Bull vs. Bear Case

Bull Case

Low-code and automation still look like they’re in the early innings. “Digital transformation” may be an overused phrase, but the underlying reality hasn’t changed: most large organizations still run on processes that are only partially automated—or automated badly. As more teams prove that workflow, automation, and orchestration can move real metrics, the addressable market keeps expanding.

AI could make low-code more relevant, not less. The endgame is obvious: describe what you need in plain language, and the system generates the application, the workflow, and the automation around it. Appian has been building toward that future with AI Copilot and its agent-style capabilities, positioning the platform as a place where AI can operate inside governed processes instead of living as a standalone experiment.

Appian also benefits from deep enterprise relationships and real switching costs. A cloud subscription revenue retention rate of 116% as of December 31, 2024 suggests customers are expanding usage over time, not quietly drifting away. And Appian’s vertical strength—especially in financial services and government—creates defensible pockets where compliance, auditability, and security aren’t negotiable, and where “we already have something bundled” is less persuasive than “we can trust this in production.”

That’s the core of the “hyperscalers won’t win everything” argument. Microsoft Power Apps can be great for quick, departmental use cases. But when a process is mission-critical, cross-system, and heavily regulated, enterprises often want more control, more governance, and more orchestration than a lightweight tool provides.

There’s also a credible margin expansion story if the mix keeps moving toward cloud subscriptions. In 2024, gross profit was $466.8 million, a gross margin of 75.6%. If services continue shrinking as a percentage of revenue over time, the business should naturally start to look more like a pure software model.

Finally, Appian has something rare: a founder-CEO with true strategic continuity. Matt Calkins has led the company since co-founding it in 1999. That kind of tenure can be a competitive advantage in enterprise software, where long product cycles and multi-year customer relationships reward patience—and where many companies get whipsawed by leadership changes.

Put all that together, and you get the “re-rating” argument: if growth re-accelerates, Appian’s valuation could look reasonable relative to other SaaS businesses—especially since the stock remains far below its 2021 highs even as revenue has continued to grow and profitability metrics have improved.

Bear Case

The bear case starts with a single, brutal word: Microsoft.

Power Platform is not just a competitor; it’s a distribution machine. For enterprises already standardized on Microsoft, Power Apps and Power Automate can feel effectively free because they’re included with broader Office 365 enterprise agreements. That changes the buying conversation from “is Appian better?” to “is Appian so much better that we should pay extra?”—a much harder hurdle, especially when budgets tighten.

Then there’s the AI wildcard. If AI coding assistants like GitHub Copilot and Cursor keep improving, traditional software development could become fast enough that low-code’s signature advantage—speed—shrinks. In that world, low-code platforms risk getting squeezed between “just build it” at the top and “good enough and bundled” at the bottom.

Appian also has to contend with the reality that growth slowed after the pandemic pull-forward. Even with continued investment in sales and marketing, sustaining the earlier acceleration proved difficult—raising the question of whether the category is normalizing, competition is biting, or deal cycles are simply getting longer.

The services mix remains another constraint. Professional services revenue was $126.5 million in 2024, down from $133.0 million in 2023. Services are declining as a share of the business, but they’re still meaningful—and they don’t scale like software, which can pressure margins and complicate the path to sustained profitability.

Customer concentration and end-market exposure add more risk. A business with meaningful government and large-enterprise exposure is inherently sensitive to federal budget dynamics and enterprise spending cycles. When procurement freezes hit, the deals you count on can slip by quarters.

And while profitability has improved, it hasn’t fully settled the debate. In 2024, Appian generated $617.0 million in total revenue, but still posted a GAAP operating loss of $(60.9) million. The question isn’t whether Appian can get more efficient—it already has—but whether it can do so while also out-innovating and out-selling competitors with bigger distribution and bigger budgets.

Finally, there’s the platform-versus-product tension. For many use cases, vertical-specific SaaS products may be “enough,” and enterprises often prefer purpose-built solutions over platforms that require customization and ongoing governance.

Key Metrics to Watch

For investors tracking Appian’s trajectory, three indicators matter most:

Cloud Subscription Revenue Growth Rate: The cleanest read on whether Appian’s platform is gaining momentum again. Acceleration would suggest the AI and automation roadmap is translating into demand; continued deceleration would point to tougher competition or a maturing market.

Cloud Subscription Revenue Retention Rate: A direct measure of how sticky Appian is once it lands. The cloud subscription revenue retention rate was 116% as of December 31, 2024—meaning customers, on average, expanded. If that number starts to fall, it’s an early warning sign that expansion is weakening or competitive displacement is creeping in.

Adjusted EBITDA Trajectory: A practical measure of whether Appian is building durable operating leverage. Adjusted EBITDA was $20.3 million in 2024, compared to an adjusted EBITDA loss of $(44.8) million in 2023. Continued improvement would validate the path toward sustainable profitability; stagnation would suggest the growth-versus-margin trade-off is still unresolved.

XIII. Epilogue and Future Outlook

Where does Appian go from here?

In a way, Appian is back at a familiar place: another bend in the road where the next platform shift could either deepen its moat—or make the old map irrelevant. The AI transformation sweeping enterprise software is both an opening and a threat. If Appian can become the orchestration layer for AI agents—the governed infrastructure that determines how autonomous systems interact with real business processes—it can make itself even more central to how large organizations operate. But if generative AI keeps pushing application creation toward “describe it and it appears,” low-code’s core pitch—speed and simplicity—could get compressed.

And hovering in the background is the unresolved legal saga with Pegasystems, which still has meaningful upside and downside attached to it. On October 28, 2025, the Supreme Court of Virginia heard oral arguments from both Pega and Appian. A decision will follow, but the timing is ultimately at the Court’s discretion. Whether the outcome ends up being reinstated damages, a new trial, or dismissal, the resolution will matter—not just for Appian’s financial position, but for how investors and customers perceive the company’s competitive posture.

Zoom out, and the low-code market itself is starting to look like it’s heading toward consolidation. There are simply too many vendors chasing the same finite pool of enterprise budget. Hyperscalers will keep bundling “good enough” tooling into broader contracts, forcing pure-play platforms to justify why they’re worth buying separately. In that environment, vertical depth may win over horizontal breadth: not just “a platform for everyone,” but a platform that can reliably run the most regulated, most audited, most mission-critical workflows in specific industries.

That reality also makes acquisition interest feel less like a wild card and more like an eventuality. Private equity, strategic buyers, or both could see Appian’s mix—enterprise customers, a mature platform, and a clear automation narrative—as attractive. Whether Matt Calkins and the board would ever sell, and what price would make it rational, is still speculation.

What’s not speculative is what founders and investors can learn from this story. Timing platform shifts is everything, but timing alone isn’t enough—you need the willingness to commit. The services-to-product transition is possible, but it’s painful, and it demands the conviction to accept short-term ugliness for long-term positioning. Enterprise software, more than almost any other category, rewards patience: long sales cycles, multi-year relationships, and advantages that compound slowly.

And competing against Microsoft requires a very specific kind of discipline. You don’t win by matching breadth. You win by drawing a line around the situations where “bundled and good enough” stops being good enough—governance, compliance, auditability, complex orchestration—and then being unmistakably better there.

Appian’s story, at its core, is a story of pivots that actually stuck. From BPM to low-code to AI process automation, it has repeatedly repositioned itself toward the next wave without abandoning the enterprise realities that made it credible in the first place. The jury—both the literal one in Virginia and the market’s ongoing verdict—still hasn’t delivered a final answer on whether Appian will lead through the AI era. But the arc so far, from a Northern Virginia basement to a NASDAQ-listed platform company generating more than $600 million in annual revenue, is already a case study in what happens when technical excellence meets strategic vision—and then gets the rarest ingredient of all: the time to compound.

XIV. Further Reading and Resources

Primary Sources:

-

Appian S-1 IPO Filing (2017) – SEC.gov – The cleanest snapshot of how Appian described its business ahead of going public: the model, the competitive landscape, and the risks management felt were most real at the time.

-

Appian Annual Reports and 10-K Filings – SEC.gov – The authoritative record for performance, segment detail, and management’s own explanation of what changed quarter to quarter and year to year.

-

Matt Calkins Earnings Call Transcripts – Seeking Alpha, Investor Relations – A recurring window into how the founder-CEO frames strategy, competition, and the long arc of the platform.

-

Gartner Magic Quadrant for Enterprise Low-Code Application Platforms – Gartner – The annual “scoreboard” many enterprise buyers still use to orient themselves in the market.

-

Forrester Wave for Digital Process Automation – Forrester – A complementary analyst view on the category and vendor capabilities, often with different emphasis than Gartner.

-

Appian vs. Pegasystems Court Documents – Virginia Court System – The primary record for the trade secret litigation, including the claims, evidence, and decisions that shaped the case.

-

Microsoft Power Platform Documentation – Microsoft – If you want to understand Appian’s most important competitive threat, start with what Microsoft actually ships and how it positions the Power Platform.

-

Low-Code Market Research Reports – Research and Markets, Grand View Research – Useful for market sizing and growth projections that frame the opportunity Appian is chasing.

-

Appian World Conference Keynotes – YouTube and Appian’s website – The company’s public “north star” each year: product launches, positioning, and where leadership says the platform is heading.

-

Hamilton Helmer’s "7 Powers" – The strategic framework used in the analysis, and a foundational read on what creates durable advantage in technology businesses.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music