Apogee Enterprises: The Story of America's Glass Giant

Introduction: The Hidden Infrastructure of the American Skyline

Stand in any major American city—Minneapolis, New York, Chicago, Dallas—and look up. The skyline is basically a monument to glass. And there’s a decent chance the glass wrapping those towers, hospitals, stadiums, and headquarters traces back to a company most people have never heard of: Apogee Enterprises.

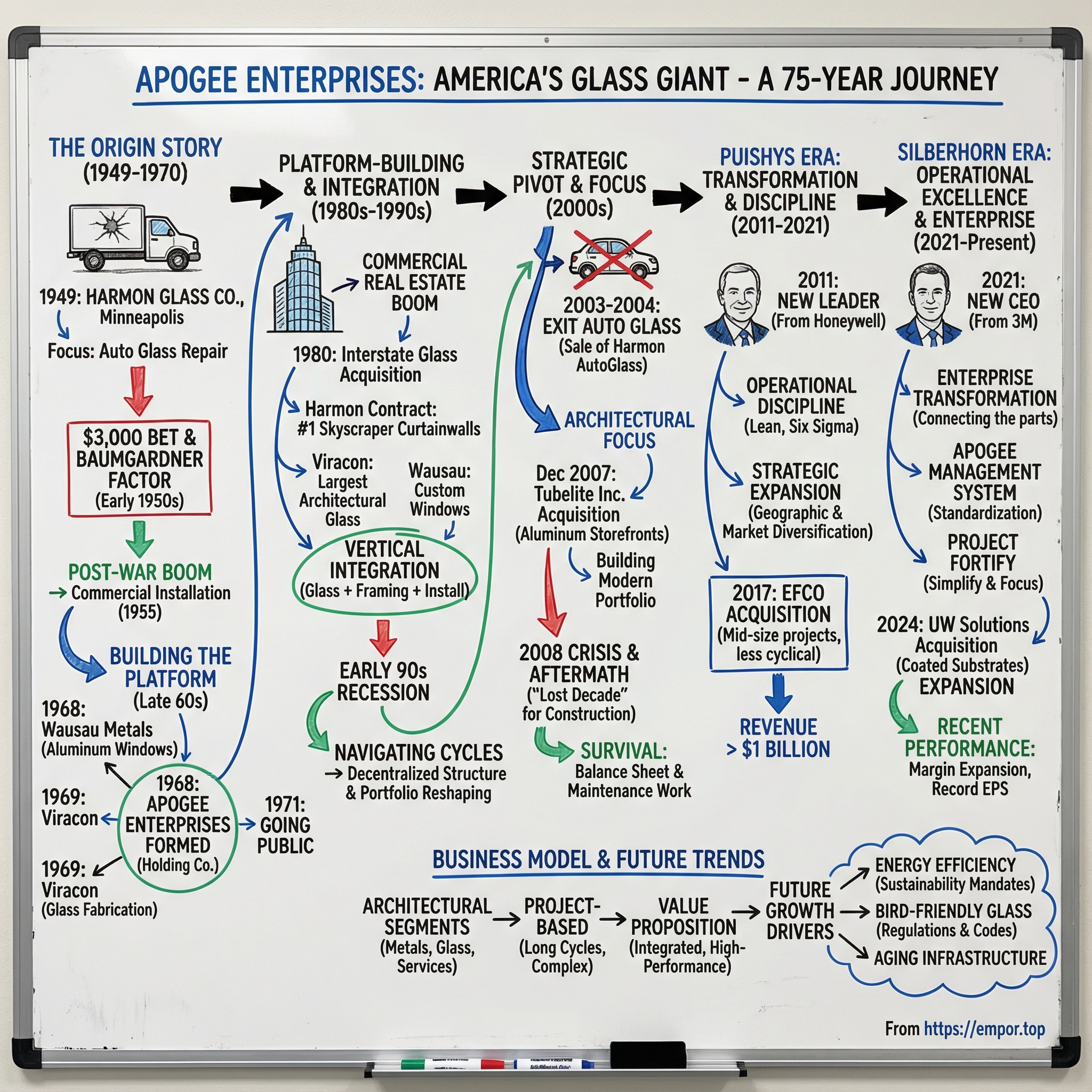

In 2024, Apogee marked its 75th anniversary. The story begins in July 1949 in Minneapolis, when Harmon Glass Company opened as a small operation focused on auto glass—repairing and replacing windshields. From that unglamorous starting point, it steadily evolved into one of the country’s most important players in architectural glass and aluminum systems.

Today, Apogee is a roughly $1.4 billion revenue business. But the real headline isn’t the size—it’s the staying power. This is a company that made it through seven-plus decades of booms and busts in a brutal industry: cyclical demand, fixed costs, job-site risk, and commodity inputs that can swing fast. Many competitors didn’t survive those cycles. Apogee did, and in the process quietly built a national platform.

So how did a 1949 Minneapolis glass shop become a company associated with projects as visible as U.S. Bank Stadium and One World Trade Center? The answer is a long, very American arc: surviving downturns, reinventing the portfolio at the right moments, and getting obsessively good at the unsexy work of executing complex projects.

Because Apogee’s story is, in a lot of ways, the story of American commercial real estate itself—from the post-war building boom, to the skyscraper era, to the Great Recession’s construction cliff, to today’s world where energy efficiency standards, new materials, and even bird-friendly glass can shape what gets built.

And it reinforces a simple truth about durable businesses: sometimes the most powerful competitive advantage isn’t disruption. It’s endurance—staying alive longer than everyone else, learning the hard lessons, and compounding operational expertise cycle after cycle.

The Origin Story: A Truck Driver's Observation (1949-1970)

The $3,000 Bet

Apogee’s story starts small—July 1949, Minneapolis—with a hunch and a pooled stake of $3,000.

A truck driver who delivered windshields and did glass installation on the side, Harold Burrows, kept noticing the same thing on his route: the shops he supplied were so swamped they couldn’t even answer the phone. That wasn’t a data set. It was a gut-level signal that demand was outrunning supply. So Burrows convinced another installer and a used car salesman to start their own service business: Harmon Glass Company.

He was right about the opening in the market. Harmon stayed busy during the day replacing windshields for used car dealers. At night, the team squeezed in another niche: installing protective screens—implosion plates—for television sets, using the same auto glass they already had access to through wholesalers. In year one, the business did $50,000 in sales—modest, but proof that the bet wasn’t crazy.

They rented space in an old tire store at 1112 Harmon Place. It was a scrappy operation in the most literal sense: installers even used motorcycles to pick up customer cars.

Even then, you can see a pattern that shows up throughout Apogee’s history: find the bottleneck, pick a niche, stretch every asset, and keep moving.

The Baumgardner Factor

The company’s next turning point arrived almost immediately—and it wasn’t optional.

Early in 1950, the founders needed cash. They went to the St. Paul lawyer who had incorporated the business, and his partner, Russ Baumgardner. Baumgardner described himself as a young, struggling lawyer, but he had the $10,000 the company needed. More than money, he brought something Harmon lacked: sound financial instincts and a real interest in building a business. He got pulled in fast and joined the payroll for a token $20 a week.

Then came the gut punch. One of the original partners—the former used car salesman—was embezzling. Nearly $7,000 was gone. There was essentially no equity left in the company. Baumgardner and the other two partners injected $5,000 in emergency cash, forced the salesman out, and kept the business alive.

It was a near-death experience in the first year. And it planted a lesson that never really leaves cyclical, project-based businesses: if you don’t control the money, the money will control you.

The Post-War Construction Boom

Harmon’s timing also mattered. Post-war America was entering a massive building era—new homes, new roads, new commercial development as the economy shifted into peacetime expansion.

Harmon started in auto glass, but it didn’t stay there. In 1955, the company began offering contract glass installation for buildings. Six years after launch, they were already moving toward the built environment—the much larger, longer-cycle opportunity that would eventually define Apogee.

Building the Platform Through Acquisitions

By the mid-1960s, the company had grown quickly—and growth started to create its own problems. Baumgardner’s philosophy was to give people responsibility, let them learn, avoid meddling, and expect good results over time. But as the business expanded into more services, the organization began to strain.

Baumgardner’s response was telling: he didn’t clamp down—he redesigned the machine. He looked at Minnesota’s biggest and most dynamic public company, 3M, and used it as a model. By October 1967, he had instituted a divisional structure with distinct profit centers, pushing decision-making down to the people closest to customers and markets.

Then, in the winter of 1968, a holding company was created to sit over those growing profit centers. That holding company was Apogee—named after an investment club Baumgardner once belonged to. He paid $1 for the right to use the name.

Apogee Enterprises, Inc. was founded in 1968 as that holding company—essentially the umbrella that allowed the business to keep expanding without collapsing under its own complexity.

And the expansion wasn’t theoretical. It came with two moves that set the integrated pattern Apogee would lean on for decades.

In 1968, for $2 million, Harmon acquired Wausau Metals Corporation—roughly as large as Harmon itself. Wausau Metals produced aluminum windows, pulling the company deeper into commercial window wall systems. When Wausau’s founder and manager, Glen Straub, announced he was moving to Las Vegas after the sale, Baumgardner’s partner, Larry Niederhofer, offered to move to Wausau for six months to run the operation and steady the transition.

Then in 1969, another foundational piece clicked into place. A young windshield manufacturer salesman, Jim Martineau, worked with Baumgardner on a plan to launch a glass fabrication business. On September 22, the Apogee board approved it, and Viracon was born—one of the nation’s first regional glass fabricators.

Put those together and you can see the blueprint forming: not just installation, but manufacturing; not just glass, but the aluminum framing systems that make modern facades possible. Apogee was quietly building an integrated platform long before “vertical integration” became a buzzword.

Going Public

By 1971, Apogee was ready for the next step. On June 30, the company and certain shareholders sold 250,000 shares, and Apogee became a public company, listing on the over-the-counter exchange.

That public listing gave Apogee more than capital. It gave it credibility with bigger customers, a currency for future deals, and a new operating reality: the discipline and pressure of public markets. For a business tied to construction cycles, that scrutiny would become both a forcing function and a recurring test.

This early stretch—1949 through the early ’70s—matters because it hardwired the company’s DNA: opportunism grounded in real-world observation, financial discipline forged in crisis, a structure designed to scale without smothering operators, and an early commitment to building capability across the glass-and-aluminum value chain.

The Platform-Building Era: Vertical Integration Takes Shape (1980s-1990s)

The Commercial Real Estate Boom

By the early 1980s, Apogee was no longer mostly an auto glass business. Auto glass had shrunk to a little over ten percent of revenue, and the center of gravity had moved decisively to commercial building. Window fabrication, riding a booming office construction market, became the company’s clearest engine—delivering roughly half of corporate earnings on only about a quarter of sales. Right alongside it, Apogee’s Commercial Construction work kept climbing.

One deal in particular helped kick that momentum into a higher gear. In 1980, Apogee acquired Interstate Glass of South Bend, Indiana, for $3.6 million. Interstate did about $7 million in sales and operated as a multiservice provider. But the real strategic value was geography: it put Apogee close to Chicago, and it accelerated Harmon Contract’s evolution from a strong regional operator into a national curtainwall contender.

Zoom out, and the 1980s read like an inflection point the company had been quietly preparing for. The Reagan-era commercial construction boom, plus a wave of architecture that leaned hard into big glass facades, created demand for exactly what Apogee was building: systems, not just panes. They weren’t simply lucky. They had spent the prior decade assembling the capabilities to take advantage of the moment.

By this time, Apogee was operating at two very different layers of the market. On one hand, it still had a massive retail footprint: 237 Harmon Glass stores across 35 states, making its Installation division the nation’s second-largest retail chain for automotive glass service. On the other hand, its commercial businesses were becoming what the industry knew it for. The Commercial Construction Division posted $248 million of revenue in 1993, and since 1987 Harmon Contract had ranked as the number one domestic designer and installer of skyscraper curtain walls. Viracon had grown into the nation’s largest manufacturer of architectural glass. And Wausau Metals had become a key provider of custom windows to commercial and institutional customers.

The Logic of Vertical Integration

The strategy underneath all of this was straightforward—and powerful: control more of the value chain. Make the glass. Build the framing. Install the system. And as projects got larger and more complex, offer customers fewer handoffs and fewer excuses.

A developer putting up a tower could turn to Apogee for Viracon’s glass, Wausau’s aluminum framing, and Harmon Contract’s installation. That wasn’t just “one-stop-shop” marketing. It meant tighter coordination, fewer disputes over who caused what problem, and deeper relationships with the architects and general contractors who decided who got the next job.

Viracon, launched in 1969, was an early proof point of what that integration could unlock—especially as it pushed into high-performance coated glass and helped set new standards for what “good” looked like in the category. Harmon, meanwhile, wasn’t just installing glass; it was building a reputation for curtainwall design and execution at the skyscraper level, and by the late 1980s it was leading the market.

As curtainwall demand surged, Apogee kept building capacity to match it. In 1983, the company formed the Wausau Curtainwall Systems Group, and that September it opened a new 60,000-square-foot facility in Wausau.

Navigating Cycles

Then came the leadership handoff. Russ Baumgardner retired in 1988, and Donald Goldfus, a seasoned internal leader, became chairperson and CEO. Goldfus pushed for greater international presence, even as the cycle turned.

Because the early 1990s were rough. The recession hit commercial building, and Apogee felt it—earnings contracted significantly. But the company held its ground. The decentralized structure—multiple profit centers serving different end markets—helped cushion the impact. Apogee didn’t emerge untouched; it emerged intact, with its core capabilities and market positions preserved.

And, true to form, it used the period to reshape the portfolio. In the Wausau Division, Apogee reorganized: it sold the coverings division, then split the remaining operation into two focused businesses—Wausau Metals for fabrication and Linetec for finishing. In 1998, Wausau Metals was renamed Wausau Window and Wall to reflect its broader scope.

By the end of the 1990s, the pattern was becoming unmistakable. Apogee expanded aggressively when demand surged, restructured when the cycle broke, and protected the capabilities that mattered most. In a business this cyclical, the goal was never to dodge downturns. It was to come out the other side with more of the industry’s hard-won expertise—and fewer scars—than the competition.

The Strategic Pivot: From Auto Glass to Architectural Focus (2000s)

Exiting the Automotive Business

The biggest strategic break in Apogee’s modern history came in 2003 and 2004, when the company chose to walk away from the business that started it all: retail auto glass.

Apogee completed the sale of Harmon AutoGlass—its auto replacement chain—to Glass Doctor, a subsidiary of The Dwyer Group. Financial terms weren’t disclosed. The rationale was clear and blunt: this was part of a long-term realignment toward architectural glass products and services, plus its picture framing glass business.

Management didn’t pretend it was an easy call. Harmon AutoGlass had real strengths. It was steady and less tied to commercial construction cycles. It had consumer brand recognition. And it was emotionally loaded—Apogee’s roots ran straight through those windshield bays.

But leadership’s view was that the market had changed, and the fit had changed with it. As the company put it at the time, Harmon AutoGlass had “made significant contributions” over the years, but was “no longer a strategic fit” given market conditions. In their view, the auto glass business would compete better under an owner fully dedicated to that industry.

In other words: focus wins. Trying to be meaningful in both auto glass and architectural systems meant battling specialists in each lane—without the scale or attention to dominate either. Selling the auto unit freed Apogee to concentrate on the segments where it believed it could build a stronger, more defensible platform: architectural glass and framing systems, architectural services for glass-heavy commercial buildings, and glass for fine-art and custom framing.

Building the Modern Portfolio

With the automotive distraction gone, Apogee leaned harder into architecture—and started filling in gaps.

In December 2007, Apogee bought Tubelite Inc., a Michigan-based fabricator of aluminum storefront, entrance, and curtainwall products, for about $44 million. Tubelite was doing roughly $60 million in annual revenue at the time, and it brought Apogee something it didn’t fully have: a strong product line in the parts of the building envelope that show up on virtually every commercial job. Apogee described the storefront and entrance market as over $1 billion—big, consistent, and adjacent to what it already did.

This was the playbook in its cleanest form: buy a well-run operator in an adjacent category, pay a reasonable price, and expand the menu of what Apogee could deliver to architects and contractors. Not a turnaround story. A capability story.

The 2008 Crisis and Its Aftermath

And then, almost immediately, the world changed.

The 2008 financial crisis didn’t just cool off commercial construction. It yanked the rug out from under it. Financing evaporated, vacancy rates jumped, and projects that were supposed to define the next decade were delayed, downsized, cancelled, or pushed into limbo.

For Apogee—now deliberately more concentrated in architecture—that was a direct hit. The company acknowledged in its annual reporting that its Architectural Glass, Architectural Framing Systems, and Architectural Services segments were tied to global economic conditions and the cyclical nature of North American commercial construction.

There were a few things keeping the lights on. Revenue held up better than you might expect, helped in part by Harmon’s maintenance and service work—activity that can persist even when new towers aren’t starting. But the environment was still brutal, and the drag from low construction activity showed up clearly in performance.

The harder truth is that 2008 through 2014 became, in many ways, a “lost decade” for commercial construction. The rebound was slow. New office starts didn’t snap back. And plenty of competitors simply didn’t survive long enough to see the next cycle.

Apogee did. And it did it the way survivors usually do: by entering the downturn with a cleaner balance sheet, managing costs with discipline, leaning on maintenance and renovation work when new construction stalled, and keeping enough financial strength to preserve the capabilities it would need later. The company didn’t fire-sale itself. It didn’t panic-strip the very muscles it would need when demand returned.

The investor lesson here is straightforward: in cyclical businesses, the balance sheet isn’t a detail—it’s the difference between endurance and extinction. The companies that went into 2008 with too much debt and too little margin often didn’t make it to 2015. Apogee did, and that set the stage for the next act.

The Puishys Era: Transformation Through Discipline (2011-2021)

A New Leader from Honeywell

By 2011, Apogee had survived the financial crisis—but survival wasn’t the same thing as momentum. Commercial construction was still sluggish, and the company was operating in one of the toughest environments its core markets had seen in decades. That’s when Apogee went outside the glass world and hired a manufacturing operator.

In August 2011, Joe Puishys was named CEO, president, and a member of Apogee’s board. He came with more than 35 years of experience in manufacturing leadership, most recently from Honeywell, where he spent three years as president of the Environmental and Combustion Controls division—a roughly $3 billion unit selling building-related controls for things like heating, cooling, lighting, and combustion systems.

Puishys had ended up in Minneapolis in the first place because Honeywell CEO David Cote tapped him to run that business. Apogee recruited him from there—and Puishys decided to take the leap. As he later put it, “It was time for Joe to make a bet on Joe.”

From his perspective, the setup was almost tailor-made for an operator. Apogee had cash on the balance sheet, no debt, and a reasonable line of credit. It was also deeply cyclical and still stuck in a painful downcycle—especially in architectural glass tied to large office projects. Puishys believed he could bring what he’d learned at Allied Signal and Honeywell—disciplined processes, operating rigor, and world-class controls—without importing the bureaucracy and red tape that often comes with big-company life. He’d been shaped by leaders like Cote, Larry Bossidy, and Roger Fradin, and he brought that same Lean-and-reliability mindset with him.

The playbook was clear: apply Honeywell-style operational excellence—Lean manufacturing, disciplined cost management, and more rigorous project selection—to a company that had the capabilities, but needed tighter execution. And the timing mattered. Puishys arrived when the industry was already being forced to change, which created room to reshape Apogee’s habits without fighting yesterday’s assumptions.

Strategic Expansion and Geographic Diversification

Operational discipline was only half the story. Puishys also pushed Apogee to expand—new products, new markets, and new geographies—with ambitious goals: double-digit operating margins and $1 billion in annual sales by 2017.

When he arrived, Apogee still skewed heavily Midwest. Over time, the footprint broadened: factories in Texas, more business in places like Florida and New England, and an active push for opportunities on the West Coast.

Just as important, Puishys worked to smooth out the roller coaster. According to Andrew Adams, chief investment officer at Mairs and Power, “Joe has intentionally and successfully diversified the company away from large marquee skyscrapers (where they lead the market by far), into markets with much less cyclicability including mid- and small-building projects as well as more installation services.”

That diversification wasn’t a single move—it was a layered strategy. Spread the geography so one region can’t sink the year. Broaden the end markets so office towers don’t dominate results. And diversify project size so performance isn’t held hostage by a handful of massive, high-risk jobs.

The EFCO Acquisition

In 2017, Puishys made the biggest deal of his tenure. Apogee announced it had closed the acquisition of 100 percent of privately held EFCO Corporation for approximately $195 million. Apogee acquired EFCO from Pella Corporation.

EFCO was (and is) a leading U.S. manufacturer of architectural aluminum window, curtainwall, storefront, and entrance systems for commercial construction. It was also growing and profitable, with annual revenue of more than $250 million. The strategic fit was almost too perfect: EFCO’s sales were largely generated from mid-size and smaller commercial projects—exactly the “less cyclical” segment Apogee wanted to lean into.

Apogee expected the deal to be accretive to EBITDA and earnings per share, and it targeted $10 million to $15 million of annual synergies and operational efficiencies by fiscal 2020.

Zoom out, and EFCO captured the Puishys thesis in one transaction: buy a strong operator in a steadier slice of the market, expand the company’s reach, and then use Apogee’s improving operating system to squeeze out efficiencies without breaking what made the acquisition valuable in the first place.

The Retirement Announcement

In 2021, Apogee announced that Puishys had informed the board of his intent to retire as CEO and board member effective February 27, 2021. He had served as CEO and a director since 2011.

The board chair credited him with reshaping the company: “During his tenure, Joe guided a transformation of Apogee, building a stronger, more diversified business that achieved considerable growth and improved profitability. Most importantly, his contributions leave the company with significantly improved growth potential.”

Puishys, for his part, framed the transition as a handoff—thanking employees and pointing to a deeper leadership bench, new productivity initiatives, and the company’s ability to navigate “the economic and personal challenges of COVID” in a way he felt proud of, both in business performance and in how Apogee treated its people.

By the end of the Puishys era, Apogee looked meaningfully different than the company he inherited: more operationally disciplined, more geographically diversified, and less dependent on the boom-and-bust dynamics of a few marquee skyscraper jobs. Revenue exceeded $1 billion for the first time under his leadership—and, more importantly, the company had built the foundation for whatever came next.

The Silberhorn Era: Operational Excellence and Focus (2021-Present)

A New CEO from 3M

Apogee’s next handoff happened quickly. The board named Ty R. Silberhorn CEO and a member of the Board of Directors, effective January 4, 2021—following its earlier announcement that Joe Puishys planned to retire. With Silberhorn’s appointment, Puishys stepped down as CEO and from the board.

Silberhorn was only the fifth CEO in Apogee’s 71-year history, and he came from outside the glass world: more than two decades at 3M. Most recently, he served as Senior Vice President of Transformation, Technologies and Services, focused on business process and digital transformation to drive growth and productivity. Before that, he held global leadership roles across multiple 3M business groups—Safety & Industrial, Transportation & Electronics, and Consumer—and earlier in his career worked in sales, marketing, and operational leadership, including as a Six Sigma business group director. Outside 3M, he also had experience running his own startup eCommerce company and working at Ashland, Inc.

The hire was a signal. Puishys had brought discipline and diversification. The board wanted the next phase to look like something even more specific: an enterprise transformation—connecting the parts, standardizing how work got done, and making the whole company run like one system.

The Enterprise Transformation

Silberhorn inherited a company that, in many ways, still behaved like a collection of businesses under one roof. Different brands. Different operating rhythms. Different IT systems—even basics like HR and payroll could vary from unit to unit. Puishys had started moving Apogee toward an enterprise model, but Silberhorn pushed harder.

With support from consultants and heavy input from employees and customers, Apogee developed a three-part plan centered on economic leadership, portfolio management, and strengthening the core. In practice, that meant making choices: selling certain assets, including an architectural glass facility in Statesboro, Georgia, while also tackling duplication across HR, IT, and finance and adopting common business practices.

The restructuring began almost immediately after Silberhorn became CEO. It touched nearly everything—from the backbone systems that run the business to the way manufacturing operations worked day to day. Silberhorn said there was a clear need to align the organization around significant changes, driven by business performance.

By Apogee’s 75th anniversary in 2024, the company was notably leaner and more focused. Apogee employed about 7,200 workers in 2020 after a decade of acquisitions. By 2024, it was closer to 4,500 after facility closures and exits from business lines with profit margins that lagged the rest of the organization.

The headline wasn’t just headcount reduction. The point was to turn a portfolio into a connected enterprise—one that could operate with better margins, more consistency, and more flexibility when the cycle inevitably turned.

The Apogee Management System

A big piece of that connection was building scalable systems and processes that could support the entire business more efficiently. Apogee rolled out the Apogee Management System, a company-wide operating system grounded in Lean and continuous improvement. Alongside it, the company invested in talent development and added functional expertise aimed at enabling sustained profitable growth.

Internally, people described how different the businesses had felt before the transformation—almost standalone. Now there was far more connectivity. Doug Betti, director of operations at Apogee’s Owatonna plant and a 24-year company veteran, said the difference was participation and buy-in: “This is by far the most effective continuous improvement program. There is a lot more floor involvement.” More shop employees were more frequently involved in identifying and implementing efficiency improvements.

Beth Lilly, chief investment officer of the Pohlad Cos. and an Apogee board member since 2020, watched the shift up close. She credited Silberhorn and his team with improving margins and return on invested capital: “He’s got the entire organization reading from the same playbook.” The enterprise model also changed careers inside the company. Where cross-segment moves used to be rare, Apogee began seeing more employees promoted and moving across business units, supported by expanded leadership development programs.

Project Fortify and Strategic Streamlining

As the enterprise work progressed, Apogee pushed into another structured simplification effort: Project Fortify. The company positioned it as a way to improve cost structure, enhance organizational efficiency, and focus the business on higher-growth, higher-margin opportunities.

In Architectural Framing Systems, Project Fortify included eliminating certain lower-margin product and service offerings, which enabled consolidation of the segment into a single operating entity. Apogee also planned to transfer production from its Walker, Michigan facility to facilities in Monett, Missouri, and Wausau, Wisconsin. The company aimed to simplify the segment’s brand portfolio and commercial model to improve flexibility, better leverage its capabilities, and enhance customer service. In parallel, Apogee implemented actions to optimize processes and streamline resources in its architectural services and corporate segments.

Apogee expected Project Fortify to deliver $12 million to $14 million in annualized cost savings and reduce the workforce by about 250 employees, with roughly 60% of the savings expected in fiscal 2025 and the remainder in fiscal 2026.

The UW Solutions Acquisition

While cutting complexity in some areas, Apogee also placed a major bet on expansion in another.

Apogee announced a definitive agreement to acquire UW Interco LLC (UW Solutions) from Heartwood Partners for $240 million in cash, subject to customary closing conditions. UW Solutions is a U.S.-based, vertically integrated manufacturer of high-performance coated substrates, differentiated by proprietary formulations and coating application processes. It serves customers across end markets including building products used in distribution centers and manufacturing facilities, as well as premium products for the graphic arts market. The business includes brands such as ResinDEK, ChromaLuxe, RDC Coatings, and Unisub.

Silberhorn called it “highly strategic,” aligned with Apogee’s strategy of adding differentiated businesses with a track record of operating excellence. He said it would strengthen Large-Scale Optical—Apogee’s most profitable segment—while expanding the company’s offering of high-performance coated substrate solutions. He also framed it as a way to broaden Apogee’s exposure to non-residential construction, including manufacturing, warehousing, and distribution center projects, and to further diversify the Large-Scale Optical segment.

On November 4, 2024, Apogee completed the acquisition of UW Solutions for $242 million in cash.

Recent Financial Performance

Under Silberhorn, Apogee has repeatedly pointed to a “step change” in performance—less about top-line heroics and more about execution, cost structure, and mix.

“Fiscal 2024 was another great year for Apogee, with record adjusted EPS and cash flow, and adjusted operating margins and ROIC that exceeded the targets we set at our investor day in 2021,” Silberhorn said. He attributed the results to sustainable cost and productivity improvements, improved operational execution, and a sharper focus on differentiated products and services that deliver more value to customers.

And the performance continued. In fiscal 2025, Silberhorn said Apogee expanded adjusted operating margin for the third consecutive year, delivered another year of adjusted ROIC above its targeted level, and achieved record adjusted diluted EPS of $4.97.

That’s the signature of the Silberhorn era so far: simplify what doesn’t earn its keep, connect the parts that should behave like one company, and use operational excellence to drive profitability even when volumes aren’t doing you any favors.

The Business Model Deep Dive: How Apogee Actually Makes Money

The Current Segment Structure

At its core, Apogee sells the stuff that turns a building into a building: the glass, the metal framing, and the on-site expertise to design, manage, and install the entire exterior “skin.” Alongside that, it also makes coated glass and acrylic products designed to protect, preserve, and improve viewing—used everywhere from museums to industrial applications. The company operates across the United States, Canada, and Brazil.

Apogee reports four segments:

The Architectural Metals segment designs, engineers, fabricates, and finishes aluminum window, curtainwall, storefront, and entrance systems for non-residential construction under the Tubelite, EFCO, Linetec, and Alumicor brands.

The Architectural Glass segment cuts, treats, coats, and fabricates glass used in custom window and wall systems under the Viracon and GlassecViracon brands.

The Architectural Services segment provides the high-touch part of the business: technical services, project management, and field installation—integrating the pieces and making sure they actually work on a jobsite.

And the Performance Surfaces segment develops and manufactures coated materials used across wall décor, museums, graphic design, digital displays, architectural interiors, and industrial flooring under brands including Tru Vue, ResinDEK, RDC Coatings, ChromaLuxe, and Unisub.

In the fourth quarter of fiscal 2025, Apogee renamed two segments to better match what they actually do. Architectural Framing Systems became Architectural Metals, and Large-Scale Optical became Performance Surfaces.

Understanding the Project-Based Business Model

The three architectural segments don’t behave like a typical “make it, ship it, recognize revenue” manufacturing company. They behave like a project business.

On a commercial building, the glazing package—the glass and aluminum building envelope—is often one of the biggest specialty subcontracts on the job. And it’s slow-moving. From the moment the glass is first envisioned on an architect’s rendering to the day installers hang it on the structure, a project can take 18 to 36 months.

The flow usually looks like this: architects set the performance requirements early—energy, thermal, safety, aesthetics. Then, once the project gets funded and construction starts, the general contractor puts the glazing scope out to bid. Specialty subcontractors like Harmon compete for it. If Harmon wins, Apogee can often bring more of the system in-house—sourcing glass from Viracon and framing from its Architectural Metals businesses. That “we can make it and install it” combination is one of Apogee’s central advantages, especially on complex jobs where coordination failures get expensive fast.

That long project timeline is also why backlog matters so much in this industry. Apogee uses backlog to gauge future potential revenue: signed contracts or firm orders that are expected to convert into revenue later. But it’s not a GAAP metric, it doesn’t tell you whether the work is profitable, and it doesn’t capture everything—because plenty of smaller, shorter-lead-time jobs are booked and completed within the same reporting period and never show up in backlog at all.

Why This Is a Hard Business

This is an unforgiving way to make money.

Apogee is concentrated in the cyclical North American commercial construction market, which means demand can swing hard with financing conditions, interest rates, and office and institutional building activity. When construction slows, it doesn’t just reduce volume—it can hollow out the future pipeline.

And even when demand is strong, the mechanics are tricky. Long project cycles create mismatches between when costs hit and when revenue arrives. Fixed-price contracts can turn ugly fast if inflation spikes or schedules slip. Aluminum and glass behave like commodities, and pricing can move against you. Installation is labor-intensive, difficult to scale quickly, and exposed to the realities of jobsites—weather, sequencing delays, and coordination across multiple trades.

The flip side is that when Apogee is doing the right kind of work—custom, complicated, high-value projects, executed with discipline—there’s real money to be made. Recent results have reflected that shift. The restructuring and operating-system work of the last few years has helped keep revenue relatively resilient, with Harmon’s maintenance and service activity providing support when new construction is uneven. And despite the inflation shocks of recent years, Apogee has been producing its strongest margins—evidence that in this industry, operational execution isn’t just a “nice to have.” It’s the whole game.

Competitive Position: Porter's 5 Forces and Hamilton's 7 Powers

The Competitive Landscape

If you want to understand who Apogee is really up against, start with Oldcastle BuildingEnvelope, better known as OBE.

On paper, Apogee is a focused, publicly traded specialist in glass, framing, and facade services. OBE is the North American heavyweight in that same lane—vertically integrated across architectural glass and aluminum framing systems, with a broad product catalog and a footprint that reaches essentially every major metro in the U.S. and Canada. For customers, that combination can be compelling: fewer vendors, more capacity, and often sharper pricing because scale buys leverage.

For years, OBE also had CRH plc behind it—one of the world’s largest building materials companies. That parent-company backing created an obvious mismatch in resources and diversification. Apogee could win on engineering, execution, and the ability to deliver custom work reliably. But OBE’s scale and breadth made it the market’s reference point for “big and everywhere.”

In 2022, KPS Capital Partners acquired Oldcastle BuildingEnvelope from CRH for approximately $3.45 billion in cash. OBE is headquartered in Dallas and remains North America’s leading vertically integrated manufacturer, fabricator, and distributor of architectural hardware, glass, and glazing systems, with a significant presence across the U.S. and Canada.

Porter's 5 Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: MODERATE-LOW

This industry is not friendly to startups. Modern fabrication facilities take enormous capital, and the know-how for complex curtain wall installation is earned over years on jobsites, not learned from manuals. On top of that, architects and general contractors tend to prefer proven partners—especially on large projects where a failure becomes a headline.

That said, the market is still fragmented. Regional players can absolutely compete—and win—within local geographies and on less complex jobs.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE-HIGH

Apogee’s brands, like Viracon and Harmon, are well respected in the architectural world. But respect doesn’t always translate to leverage—especially when you don’t control the raw materials.

Aluminum is a classic commodity input, which means Apogee is largely a price-taker. On glass, supplier power is reinforced by consolidation, with major players like PPG, NSG, and Guardian holding meaningful influence. For specialty coatings and materials, the supplier set can be even narrower. Apogee’s in-house coating capabilities at Viracon help, but they don’t eliminate exposure.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-HIGH

The buyers—especially general contractors—are professional negotiators. Work is bid competitively, and price pressure is real.

But the power isn’t absolute. Once an architect has specified certain products, switching is painful and risky. And on complex projects, the qualified bidder list is shorter than people think. Over time, owners also tend to care more about quality, reliability, and warranty coverage—because facade problems don’t just cost money, they create reputational risk.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW-MODERATE

Glass still defines modern commercial architecture. Sure, you can clad a building in metal panels or precast concrete, but those are different design choices with different tradeoffs.

Energy efficiency standards and sustainability priorities also tilt the playing field toward high-performance glazing. Apogee’s architectural products and services are positioned around those demands—improving energy performance, supporting daylighting and ventilation, and using materials like aluminum and glass that are recyclable at end of life.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

Rivalry is intense because the market is both cyclical and crowded. There are many regional competitors fighting for work, which turns commodity products into price battles fast. And when construction slows, the fight gets uglier—everyone is chasing fewer projects.

Apogee also competes with much larger, well-capitalized players like Oldcastle (and other global giants), many of which have broader product lines, bigger footprints, and more flexibility to absorb volatility. In that environment, differentiation tends to come down to service, technical capability, and execution—especially on large, complex jobs where mistakes are expensive.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: MODERATE

Scale helps in manufacturing: bigger plants tend to produce at better unit economics, and purchasing leverage improves as volumes rise. But there’s a limiter here—glass is heavy, fragile, and expensive to ship. Transportation keeps this from becoming a pure “whoever is biggest wins everywhere” game. Still, a national footprint matters, especially for customers running multi-site programs.

Network Effects: NONE

No network effects. A great project doesn’t make the next one automatically easier to “share” in the way software does.

Counter-Positioning: NONE

Not a category where a new business model can easily undercut incumbents while incumbents can’t respond.

Switching Costs: MODERATE

Switching is real once products are specified or once a team is deep into a project. Warranty and service relationships add stickiness too. But the market resets on every new job—each project is a rebid opportunity, which keeps pressure on everyone.

Branding: MODERATE

Apogee’s brands carry weight where it counts: among architects, glazing contractors, and the people who live in specifications and shop drawings. Viracon for architectural glass, Harmon for installation, and Wausau for windows are recognized names in their niches.

But the building owner’s tenant doesn’t care who fabricated the glass. Branding helps you get specified and trusted; it doesn’t turn into consumer-style pricing power.

Cornered Resource: LOW-MODERATE

Proprietary coating capabilities and a skilled labor base provide advantage, but none of it is permanently exclusive. Given enough time and money, strong competitors can replicate technology and train talent.

Process Power: MODERATE-HIGH

This is where Apogee earns its edge.

Project execution in building envelopes is brutally hard: sequencing across trades, jobsite realities, change orders, quality control, and the constant risk that one mistake cascades into weeks of rework. Apogee has decades of scar tissue here—in a good way. Sophisticated project management, design-assist capabilities, disciplined bidding, and repeatable operating practices create a learning-curve advantage that’s difficult to copy quickly.

In this business, the winners aren’t the ones who can win bids. They’re the ones who can win bids and still make money when the project gets messy. That operational knowledge—the ability to price risk, manage it, and deliver—is Apogee’s most durable competitive advantage.

Energy Efficiency and Bird-Friendly Glass: The Emerging Growth Drivers

The Sustainability Opportunity

At a high level, Apogee’s value proposition is simple: help enclose commercial buildings with glass and aluminum systems that look great, perform better, and last. In practice, that means its subsidiaries engineer, fabricate, install, repair, and sometimes retrofit the glass walls, windows, and entrances that make up a building’s exterior. And increasingly, the selling point isn’t just aesthetics. It’s performance: energy efficiency, hurricane resistance, and even blast protection.

Apogee serves primarily commercial, institutional, and multi-family construction customers. Across its architectural businesses, it designs and builds custom window, curtain wall, storefront, and entrance systems. And on the glass side, its Architectural Glass segment fabricates coated glass and applies high-performance coatings to uncoated glass, creating products that can deliver energy savings while also meeting an architect’s demands for color, reflectivity, and unique design effects.

This shift toward higher-performing building envelopes has been building for years. During a keynote at the 2020 Building Envelope Contractors Conference, then-CEO Joe Puishys pointed to new requirements for more sustainable, better-performing, and more thermally efficient glass and glazing products as a major opportunity for the industry.

Bird-Friendly Glass Regulations

Then there’s a demand driver that sounds niche—until you realize it’s becoming code: bird-friendly glass.

Viracon has worked to combine bird-friendly design with high-performance coatings, aiming to reduce glare and solar transmission for better energy performance and lower emissions. The company has invested in bird-friendly solutions and participated in ongoing research on how different glass products can reduce bird strikes. Its emphasis has been on practical approaches—using conventional glass products, plus enhancements, to meaningfully reduce collisions. Over time, Viracon has collaborated with groups like the American Bird Conservancy and other organizations across the U.S. to better understand which fabrication options can actually move the needle.

Regulation is now accelerating that work from “good idea” to “required spec.” A growing list of states and provinces across North America have introduced bird-friendly building codes, including California, Illinois, Ontario, Oregon, Minnesota, Washington D.C., Virginia, Wisconsin, Alberta, British Columbia, Maryland, and Maine. These rules often require bird-safe materials—glass products or treatments that reduce dangerous reflections. And beyond the places that already have codes, many other regions are actively proposing similar legislation. At the federal level, the Federal Bird Safe Buildings Act represents a push toward broader adoption.

LEED certification has also added bird collision deterrence to its credits, and it has reported a significant increase in interest. Meanwhile, major cities have started making bird-friendly glass mandatory—places like Chicago, New York, and Washington, D.C., along with major Canadian metros like Toronto.

The strategic point is bigger than birds. This is the kind of regulation that can create a secular tailwind: as more jurisdictions mandate bird-friendly glass, building owners may be forced to upgrade or replace existing glass, which can drive demand even when new construction slows. Viracon is positioned to benefit from that shift.

Bull Case vs. Bear Case

The Bull Case

Secular Tailwinds: A bunch of forces are quietly stacking in Apogee’s favor. Energy-efficiency mandates are pushing upgrades and replacements. Bird-friendly regulations are turning “nice to have” into “must spec.” A huge portion of America’s commercial building stock is aging into renovation cycles. At the same time, reshoring is driving new manufacturing facilities, healthcare systems are still expanding, and data center construction continues to surge.

Competitive Position: Apogee’s strategy is built around selling performance, not commodity square footage. It can deliver high-performance architectural glass and complete building façade solutions, including installation. That integrated model—from fabrication to jobsite execution—lets Apogee take on complex, custom work that pure commodity suppliers struggle to handle. It’s not an unbreakable fortress, but it is a real niche.

And Apogee is one of the few players with a true national footprint. Process improvements have been expanding margins. More disciplined project selection has reduced volatility. And ongoing technology investments—especially around coatings and performance—create differentiation that matters when architects and contractors are choosing who they trust on high-stakes jobs.

Financial Profile: This is still a cyclical business, but it’s one with a strong balance sheet and flexibility in how it allocates capital. The stock has tended to trade at reasonable multiples for a cyclical. Cash flow has been relatively consistent, and backlog provides some near-term visibility, even if it doesn’t guarantee profitability.

Potential Catalysts: More infrastructure spending can translate into public building work. A sustained return-to-office trend would help the commercial real estate environment stabilize. And ESG-driven building efficiency investments can keep pushing owners toward higher-performance glazing and retrofits.

The Bear Case

Cyclicality and Macro Sensitivity: Apogee can’t escape its core reality: it lives and dies with North American non-residential construction. In the near term, the outlook is muted. Over the next year (FY26), consensus expects modest declines in both revenue and EPS, tied to softening new construction starts. One of the most sensitive swing factors is profitability in the Architectural Glass segment—small changes in margin there can have an outsized impact.

Layer on tariffs, and the near-term gets messier. The company has said it expects tariff-related impacts of $0.55, with most of the hit concentrated in the first half of fiscal 2026 before mitigation efforts fully take hold. Combined with moderating operating margins in Metals and Glass and higher interest expense, Apogee expects more significant year-over-year declines in adjusted diluted EPS in the first and second quarters of fiscal 2026.

Then there’s the broader macro backdrop: higher interest rates pressure commercial starts, office faces structural headwinds tied to remote work, and a recession would likely hit construction spending hard.

Competitive Threats: Apogee’s main competitive problem is scale. Global giants like Saint-Gobain, and massive building-products platforms like CRH’s Oldcastle BuildingEnvelope, can often buy raw materials cheaper, spend more on R&D, and absorb volatility across a wider geographic and product footprint.

In parts of the portfolio, commoditization is always lurking. Competitor consolidation can intensify pricing pressure. And international competition—from Chinese glass to European framing systems—adds another layer of threat, especially when cost becomes the deciding factor.

Limited Moat: Apogee’s advantages are real, but they’re not absolute. Its smaller scale and lack of vertical integration into raw glass manufacturing can create cost and supply disadvantages versus the largest players. And because it remains tied to a cyclical market, earnings can swing with the cycle—making it a tougher fit for investors looking for a truly durable, all-weather moat.

Key Metrics for Investors to Watch

If you’re trying to figure out whether Apogee’s transformation is real—and whether it’s sticking—there are three numbers that matter more than almost anything else.

1. Adjusted Operating Margin by Segment

This is the cleanest way to see whether the operational improvements are actually durable, and which parts of the portfolio are pulling their weight. Apogee has expanded adjusted operating margin for three consecutive years. If that continues, it’s strong evidence the “one enterprise” operating model is working, not just showing up in PowerPoint.

2. Backlog Levels and Book-to-Bill Ratios

Because this is a project business, backlog is the closest thing you get to a forward-looking demand signal. And book-to-bill gives you the direction of travel: above 1.0 means the company is signing more work than it’s burning off, which is generally what you want to see. When backlog starts shrinking, it usually isn’t subtle—less work is coming, and the slowdown tends to show up in results later.

3. Return on Invested Capital (ROIC)

Apogee has pointed out that fiscal 2024 delivered adjusted operating margins and ROIC above the targets it laid out at its 2021 investor day. ROIC matters because it forces the honest question: is management turning capital into real economic value? For a company that grows through acquisitions and invests heavily in plants, equipment, and systems, ROIC staying above the cost of capital is the difference between smart expansion and expensive churn.

Lessons for Investors and Operators

Lesson 1: Surviving Cycles Is the Game

In cyclical businesses, survival is strategy. Balance sheet strength matters more than growth when the market turns, because the downturn is when everyone else is forced to make desperate choices. Apogee’s biggest competitive advantage across 2008–2014 wasn’t some secret product. It was the ability to stay standing while others fell over—and to come out of the trough with its capabilities intact.

Lesson 2: Know Which Projects to Turn Down

In project businesses, it’s not enough to win work. You have to win the right work. Bad jobs don’t just hurt margins; they can blow up schedules, consume management attention, and damage reputations with the exact people who decide who gets the next bid. Apogee’s shift toward more disciplined project selection—especially under Puishys and then Silberhorn—helped improve profitability even when the top line wasn’t doing them favors.

Lesson 3: Vertical Integration as Competitive Advantage

Owning more of the value chain—glass fabrication, aluminum framing systems, and installation—creates real advantages: tighter coordination, fewer handoffs, and fewer “that’s not my problem” moments when something goes wrong. But integration isn’t automatically a moat. It only works if you’re operationally excellent at each step. Apogee has spent decades building the processes and experience to make that integration pay off.

Lesson 4: Relationships and Reputation Compound

Architects don’t hand you a specification because your brochure looks good. They do it because you’ve proven you can deliver. In this industry, relationships are earned through execution—one job at a time—and then they compound. Do great work on one high-visibility project, and you’re more likely to be trusted on the next. That kind of relationship capital is incredibly hard for new entrants to recreate quickly.

Lesson 5: The Power of Boring, Essential Infrastructure

This isn’t a glamorous business. But it’s essential. Buildings need envelopes, and modern buildings keep leaning toward glass. Over decades, the secular direction has been clear: more daylighting, more transparency, more high-performance glazing. The specific cycle will always change, but that underlying architectural trend has been remarkably durable.

Lesson 6: Technology as Incremental Advantage

In industrial businesses, technology usually doesn’t arrive as a single, world-changing breakthrough. It shows up as a thousand small advantages: better coatings, better automation, better digital tools, better project execution systems. Each one might be incremental. Together, they add up to higher quality, lower cost, and fewer mistakes—and over time, that’s how you pull away from less sophisticated competitors.

Lesson 7: Management Matters in Cyclical Businesses

Cyclical industries punish bad timing and reward discipline. The job is to avoid getting drunk in the boom—over-hiring, over-building, over-promising—and to protect the core when the bust arrives. Apogee’s CEO transitions reflect that reality. Different eras called for different strengths, and the company’s longevity is largely the story of leaders making the right kind of decisions for the cycle they were handed.

Final Reflections: The Beauty of Boring

There’s something quietly elegant about Apogee’s story, because it’s the opposite of the usual business-success script. No breakthrough invention. No viral adoption curve. No single moment where the world suddenly “gets it.” Just 75 years of doing something fundamental—enclosing buildings with glass and aluminum—and relentlessly getting better at it.

If you want proof, you don’t have to dig through annual reports. You can just look around.

Apogee’s work shows up in Twin Cities landmarks like U.S. Bank Stadium, the Minneapolis Central Library, and Capella Tower. Viracon glass encloses One World Trade Center—the tallest building in the U.S. And that’s the point: in almost any American city, you’re probably looking at Apogee’s impact without knowing the name behind it. Towers, hospitals, universities, corporate campuses—Apogee has become part of the invisible infrastructure of American commercial life.

The lessons here are bigger than one company:

For investors: Boring businesses can be good businesses. Process power and reputation are real advantages, even if they don’t show up cleanly in a spreadsheet. Cyclicals demand a different valuation mindset. And management quality matters—especially when the cycle turns.

For operators: Long-term thinking beats short-term optimization in cyclical industries. Operational excellence compounds, but only if you keep doing the unglamorous work: discipline, systems, execution, and learning from mistakes. Sometimes the smartest strategy is simply staying alive long enough to outlast competitors.

For founders: Not every great business needs to be a tech unicorn. There’s real value in mastering a hard, “boring” industry and becoming the trusted default. Steady execution, customer relationships, and surviving downturns can be its own kind of power.

The future will bring plenty of tests—tariffs, interest rates, office vacancy rates, and competition from bigger platforms. But Apogee has seen tougher environments than today. The company that began because a truck driver noticed glass shops couldn’t even answer their phones survived recessions, a financial crisis, waves of consolidation, and multiple reinventions of its own portfolio.

And the market is still moving in Apogee’s direction. Architecture continues evolving toward transparency. Energy efficiency is becoming non-negotiable. Smart glass and more integrated building systems could reshape what “high-performance” means. Whether Apogee stays relevant for the next 25 years will come down to the same thing that got it here: disciplined strategy paired with repeatable execution.

As CEO Ty Silberhorn said at Apogee’s 75th anniversary: “Throughout its history, our company has reinvented itself several times, by innovating our business model and offerings to adapt to the changing market. While we take great pride in our history, we’re just as excited about what the future holds for Apogee. We are strengthening our operations, improving our products and service for customers, and investing to strengthen our team and grow our business.”

That’s Apogee’s story in one line: not disruption, but adaptation. Not revolution, but evolution. Not a hockey stick, but compounding improvement over seven decades.

In a business world obsessed with the flashy and the fast, there’s something refreshing about a company that wins by simply getting better—year after year—at the work that holds modern buildings together.

Further Reading & Resources

If you want to go deeper—into Apogee specifically, or the broader world of architectural glass, building envelopes, and commercial construction—these are the sources that give you the most signal:

-

Apogee Enterprises Annual Reports (2015-2024) — The clearest primary source for how the strategy evolved under Puishys and then Silberhorn, straight from shareholder letters and segment commentary.

-

"The Tower and the Bridge: The New Art of Structural Engineering" by David Billington — A great way to understand the engineering logic behind the modern skyline, and why “just glass” is never actually just glass.

-

AIA (American Institute of Architects) Commercial Construction Outlook — One of the better windows into forward demand, since architects tend to see projects before shovels hit dirt.

-

U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC) LEED Standards Evolution — Helpful context for how sustainability requirements move from optional to expected—and eventually into code and specs.

-

Dodge Construction Network Reports — A grounding source for construction starts and momentum trends that shape backlog across the industry.

-

National Glass Association Publications — Industry-level perspective on technical innovation, manufacturing trends, and the realities of the glass supply chain.

-

Apogee investor presentations and earnings call transcripts — The quickest way to hear management explain what’s working, what’s not, and what they’re optimizing for.

-

Commercial real estate market research (CBRE, JLL reports) — The macro overlay: office, industrial, healthcare, and multi-family trends that ultimately drive how much gets built—and where.

-

Energy efficiency standards and regulations (DOE publications) — The regulatory backbone behind high-performance glazing tailwinds.

-

American Bird Conservancy Publications — A solid primer on bird-safe building standards and why bird-friendly glass is increasingly showing up in real-world specifications.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music