Alpha & Omega Semiconductor: From Fab-Lite Innovator to Power Management Powerhouse

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture a cramped conference room in Sunnyvale, California, in the final months of 2000. The dot-com bubble has popped, the NASDAQ is sliding hard, and a lot of semiconductor startups are doing the only thing they can: hunt for an exit or quietly shut the lights off. Into that wreckage walks Dr. Mike Chang, a 26-year industry veteran who has just resigned from an executive role at Siliconix, a Vishay subsidiary, with a conviction that sounds almost backward.

This is the right time to start a power semiconductor company.

Chang pulled together a small founding team—Yueh-Se Ho, Anup Bhalla, and Sik Kwong Lui—set up in modest office space, and bet on a simple thesis: power management was overdue for disruption. Alpha and Omega Semiconductor was incorporated on September 27, 2000. From that unglamorous start, AOS grew into a real player in power semiconductors, generating roughly $690 million in trailing twelve-month revenue as of November 2025.

At its core, AOS set out to win on three things: strong design, manufacturing capability it could rely on, and a reputation for being unusually responsive to customers. Not by selling a single “miracle chip,” but by steadily building a portfolio of parts that solve very specific power problems—more efficiently, more reliably, and often faster than larger competitors.

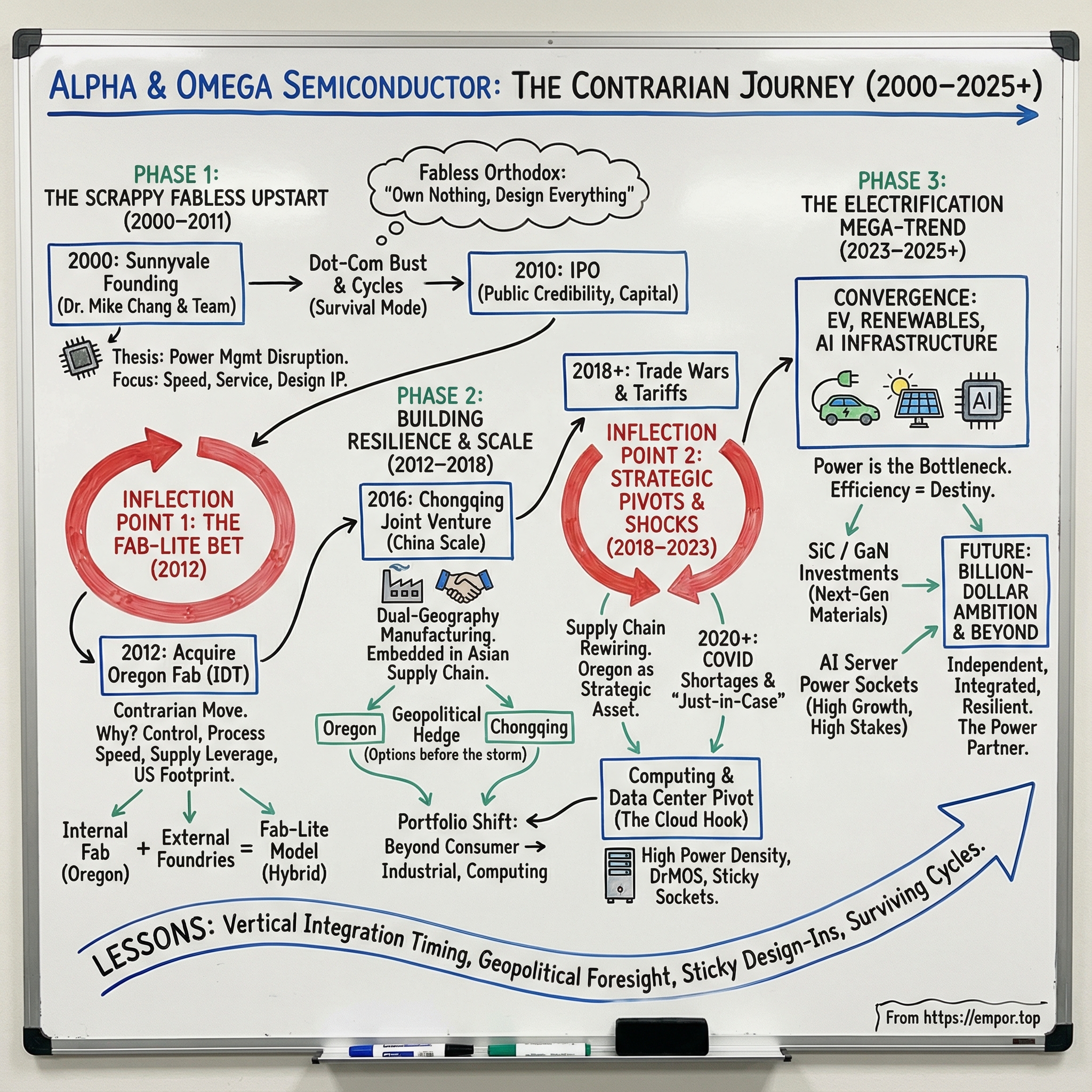

So the hook for this story is deceptively simple: how did a 2000-era fabless startup survive the consolidation wave, break with Silicon Valley orthodoxy to go fab-lite, and then carve out a durable position in an industry dominated by giants many times its size?

The answer runs through four inflection points—the moments where AOS didn’t just execute, but changed its trajectory.

The first was choosing to own manufacturing capacity when conventional wisdom said, “stay fabless.” In 2012, AOS acquired an 8-inch wafer fab in Oregon from Integrated Device Technology (IDT), a move aimed at expanding and optimizing products, pushing process innovation, and anchoring meaningful manufacturing in the United States.

The second was building scale in China—most notably through a joint venture in Chongqing—creating a dual-geography manufacturing footprint that would later look a lot like foresight when trade tensions escalated. AOS entered a definitive agreement with two strategic investment funds owned by the Municipality of Chongqing to form that joint venture, with initial capitalization of $330 million.

The third was a portfolio and go-to-market shift: moving beyond the churn of consumer electronics and leaning into computing and data centers, where power delivery was quietly becoming a limiting factor for performance and efficiency.

And the fourth is the wave the whole industry is riding right now: electrification. Electric vehicles, renewable energy, and AI infrastructure all turn power conversion into a strategic bottleneck—and that’s exactly the kind of bottleneck a power semiconductor company can monetize.

Today, AOS designs and supplies a wide range of power components: discrete power devices, power management ICs, and modules, spanning technologies like Power MOSFETs, IGBTs, and newer wide bandgap options like SiC and GaN. Underneath those product lines is what really matters in this market: accumulated process know-how, device design IP, and the ability to take a customer’s real-world constraints—space, heat, cost, efficiency targets—and turn them into parts that pass qualification and ship at scale.

That’s why this story is bigger than one company. AOS is a case study in when vertical integration actually helps, how manufacturing geography has become a competitive weapon, and how a mid-sized specialist can survive—and sometimes outmaneuver—companies with far more scale.

II. Founding Context & The Fabless Revolution

By the late 1990s, the semiconductor industry had a new gospel: go fabless. TSMC and UMC had proven that you could design chips without owning a factory, sidestep the brutal capital costs of a fab, and still scale—because the manufacturing could happen an ocean away in Taiwan. For digital logic and processors, it was a revolution. A wave of startups sprang up, armed with clever designs and someone else’s production line.

Power semiconductors, though, lived in a different universe.

Digital chips rode Moore’s Law. Power devices fought physics. They dealt with high voltage, high current, heat, reliability, and the kind of messy real-world constraints that don’t neatly improve with every node shrink. In power, progress often comes from device structures, process tweaks, packaging, and manufacturing know-how. And that’s where a pure “design-only” model can start to break down: if you don’t understand the factory, you can’t fully control the performance.

That tension is exactly why Mike Chang was the right founder for this company.

Before starting AOS, Chang was Executive Vice President at Siliconix—by then a Vishay subsidiary—from 1998 to 2000, after holding a range of management roles there from 1987 to 1998. Before Siliconix, he spent 13 years at General Electric from 1974 to 1987, focused on product research and development in management roles. In other words: he didn’t just know power semiconductors. He knew them from the inside of big, vertically integrated organizations.

And that gave him a clear view of the incumbents’ Achilles’ heel.

Companies like Fairchild Semiconductor, International Rectifier, and Vishay dominated the market, but they carried the weight of their own fabs. Those fabs were expensive to maintain, expensive to upgrade, and they shaped the whole business: long product cycles, slow decision-making, and pricing that reflected heavy fixed costs. They were strong—but not fast.

Chang’s founding insight was straightforward: take what worked about the fabless revolution—speed and capital efficiency—and apply it to power. But don’t treat manufacturing like an afterthought. Instead, build tight partnerships with foundries and push proprietary process technologies through those partners, so AOS could still differentiate at the device and process level.

Call it fabless with manufacturing intimacy.

In the beginning, that strategy pointed to the obvious beachheads: MOSFETs and IGBTs for computing and consumer electronics—PC motherboards, power supplies, and battery management. These were high-volume, price-sensitive markets where a leaner cost structure mattered, and where a nimble team could win by delivering the right part quickly, with competitive performance, at the right price.

AOS started in Sunnyvale, planted directly inside the Silicon Valley ecosystem. It was founded by a group of experienced semiconductor professionals led by Dr. Mike F. Chang, who would go on to serve as Chairman.

But “Silicon Valley startup” didn’t mean easy.

The company was born into the dot-com crash, then immediately ran into the 2001 recession—exactly the moment it needed customers to take a chance on a new supplier. The early years were pure survival mode: get qualified, win design slots, ship reliably, and build trust one customer at a time. What kept them afloat was a mix of technical depth and industry relationships—people who understood the power market and knew how to navigate it.

In 2006, AOS raised $30 million in a venture capital round led by Sequoia Capital. And in a detail that says a lot about how AOS operated, the company essentially never needed to lean on that cash. Sequoia didn’t sell shares in the IPO, either. That discipline—spend carefully, execute, avoid drama—became part of AOS’s identity.

By the mid-2000s, AOS was no longer just a scrappy upstart. It had developed proprietary device structures that delivered better performance in targeted applications. It was building momentum with major ODMs in Taiwan—the manufacturing engine of the PC industry—and stacking design wins that translated into real volume.

The fabless playbook was working.

But Chang could also see the ceiling. In power semiconductors, manufacturing isn’t just capacity—it’s capability. And as AOS grew, that question started to loom: how long could they rely on the old model before it became a constraint?

III. Early Growth & Surviving the Semiconductor Cycles

From 2000 to 2008, AOS got its first real education in what it means to build a semiconductor company the hard way. The dot-com bust hit almost immediately. Then came the 2001–2003 downturn. And through it all, the industry’s natural rhythm—booms, busts, inventory whiplash—kept testing whether AOS’s founding thesis could survive outside a slide deck.

In the beginning, revenue didn’t “ramp.” It dripped in. Power semiconductors don’t get designed in over a couple of meetings. A typical cycle ran roughly 12 to 18 months from first engagement to production, and customers were conservative by necessity. If a power device fails, it doesn’t just break a feature; it can take down the whole system. So every early design win was a slog—earned the old-fashioned way against incumbents who could point to decades of reliability data and millions of units shipped.

What kept AOS alive was discipline. Because it didn’t own a fab, it didn’t have to pour money into equipment just to stay in the game. That capital efficiency let the team focus on what actually moved the needle: R&D and being relentlessly available to customers. Over time, AOS built real technical differentiation through proprietary device structures—work in MOSFET cell design, trench architectures, and shielded-gate approaches that improved the metrics power engineers obsess over, like on-resistance (Rds(on)), switching behavior, and heat handling.

This is also where the China strategy started to form—not as a late-stage pivot, but as an early edge. While many established competitors were still anchored in manufacturing footprints across the U.S., Japan, and Europe, AOS built relationships with Chinese foundries and began working its way into Chinese OEM supply chains. That turned out to be well-timed positioning as electronics manufacturing continued shifting toward Asia.

Then came the moment that changed AOS’s posture in the market: becoming a public company. Alpha and Omega Semiconductor completed its initial public offering on April 29, 2010. By ownership, the company was held primarily by institutional shareholders, with a meaningful insider stake as well.

The IPO gave AOS two things it badly needed: a stronger capital buffer and the credibility that comes with being a listed supplier when you’re trying to win larger, more demanding accounts. But it wasn’t a clean “ring the bell and everything gets easier” story. The timing was rough, with the stock entering the public markets right as semiconductor sentiment weakened amid broader market volatility in May 2010.

Investors also struggled to categorize what AOS really was. The stock traded at a discount driven by a mix of macro fears about the semiconductor cycle, unfortunate timing around the selloff, and a lingering perception that AOS was stuck in a low-margin, commodity segment.

That perception would hang around for years, even as management argued the business was more nuanced. Yes, power is cyclical. Yes, PCs—an important early end market—were mature. But underneath that, AOS was quietly building the kind of assets that matter in this niche: differentiated device know-how and relationships that, once established, tend to stick.

The company’s model leaned toward high-mix, lower-volume specialty products rather than pure commodity discretes. It meant giving up some easy scale. But in exchange, AOS got something more valuable: pricing power where performance mattered, and customer stickiness created by long, expensive qualification processes. Once a part was designed in, switching wasn’t just a purchase order decision—it meant months of testing, risk of delays, and the uncomfortable possibility of field failures. Most customers don’t take that lightly, which is exactly why those early, hard-won design wins mattered so much.

IV. The Great Recession & Strategic Pivot: The Fab-Lite Decision

The 2008–2009 financial crisis became the first real inflection point in AOS’s strategy. On the surface, it was just another brutal semiconductor downcycle. In reality, it exposed a structural problem with the pure fabless model—and pushed Mike Chang toward a decision that would permanently change how the company competed.

Here’s what the crash made painfully clear. When demand fell off a cliff, foundries pulled back capacity. Then, when demand snapped back, those same foundries rationed supply—and the biggest customers got served first. Smaller fabless players like AOS were left scrambling for wafers, trying to explain to customers why they couldn’t ship. The whiplash of inventory corrections, sudden shortages, and priority lists reinforced what Chang had long suspected: in power semiconductors, manufacturing isn’t just a cost center. It’s leverage. And AOS didn’t have enough of it.

Then an opening appeared.

In 2011, Integrated Device Technology announced it would divest its 200mm wafer fabrication facility in Hillsboro, Oregon as it moved to a fully fabless model and transitioned its products to TSMC. Under a foundry service arrangement with IDT, AOS had the option to acquire the facility and related assets for $26 million. IDT expected that, if things stayed on track, the parties would sign an asset purchase agreement by the end of 2011 and close by the end of January 31, 2012.

For a company that had built itself on being fabless, buying a fab looked almost heretical. Even observers close to the deal framed it as unusual: a fabless company buying a fab was “a new and innovative approach,” and possibly a sign that other semiconductor companies might eventually rethink their own manufacturing posture.

But for AOS, the logic wasn’t about nostalgia for vertical integration. It was about control.

First, in-house manufacturing could speed up proprietary technology development. In power devices, performance is deeply tied to process—device structures, cell designs, and packaging. Being able to iterate without negotiating priorities and timelines across a third-party foundry could compress development cycles and get new products to market faster.

Second, it created real supply chain leverage. When demand surged, AOS could allocate wafers to itself. When a customer needed a custom process, AOS could pursue it without convincing an outside partner to make room.

And third—quietly, almost as a bonus—it gave AOS a meaningful U.S. manufacturing footprint. In 2012, that wasn’t the main point. But as U.S.–China tensions escalated later in the decade, it would prove far more valuable than most people assumed at the time.

On December 14, 2011, Alpha and Omega Semiconductor signed a definitive agreement to acquire the Oregon wafer fabrication facility and related assets from IDT for $21.3 million, and assumed specified liabilities of $0.5 million related to the purchased assets. The acquisition closed on January 31, 2012.

AOS rechristened the facility as Jireh Semiconductor, a wholly-owned subsidiary. It also meant roughly 250 jobs staying in the United States, and it planted AOS in the Pacific Northwest’s “Silicon Forest.” As the company would later describe it, Jireh’s mission was “To Bring Manufacturing Back to the United States Profitably.”

None of this was plug-and-play. A fab built around IDT’s products didn’t magically become a power semiconductor factory. Converting processes, retraining teams, and getting yields where they needed to be took time and money. And fab ownership brought fixed costs that could weigh on margins during the ramp. Chang was blunt but optimistic with investors in early 2012: “We are ramping our new fab in Oregon as planned, which I strongly believe will improve our revenue and gross margin as it helps us enhance the efficiency of R&D efforts and accelerate the time-to-market of new products.”

Out of that ramp came AOS’s signature operating posture: fab-lite.

Not fully integrated. Not purely fabless. A middle path designed for the analog realities of power semiconductors—own the critical capacity that drives differentiation and supply assurance, and outsource overflow production and certain processes to third-party foundries. It was a bet that AOS could capture the advantages of vertical integration without drowning in the capital intensity that had slowed down so many incumbents.

V. China Ascendance & The Asian Electronics Boom

From 2010 to 2016, global electronics didn’t just grow—it reorganized itself around Asia, and especially around China. Smartphones went from luxury to default. Tablets had their moment. Chinese brands like Xiaomi, Oppo, Vivo, and Huawei scaled from upstarts into global contenders. LED lighting flipped from “specialty” to standard. And behind every one of those products sat the same unglamorous truth: if you couldn’t manage power efficiently, you couldn’t compete.

AOS was ready for that shift. Years earlier, it had started building relationships inside the Chinese OEM world and the broader ODM ecosystem that fed the global brands. It wasn’t just selling parts; it was showing up with engineers, working through real constraints, and tuning power solutions to specific designs. That combination—proprietary technology, fast support, and competitive pricing—won it design slots that larger competitors often ignored as too small, too custom, or too much trouble.

But AOS didn’t want to be only close to customers. It wanted to be close to manufacturing, too.

In 2015, the company announced a major step in that direction: a joint venture in Chongqing that would expand its China footprint and push its fab-lite strategy further downstream into assembly, testing, and eventually wafer fabrication.

"We are excited to begin this partnership, which we believe will enable both AOS and Chongqing to grow and prosper," said Dr. Mike Chang. "This joint venture with Chongqing represents an important milestone in our strategic roadmap. It will help further diversify our offerings of power semiconductor products and improve our access to customers in China as we work to accelerate our long-term growth and profitability."

The structure was telling. Under the proposed agreement, the initial capitalization of the joint venture was expected to be approximately $300 million. The Chongqing authority would own 49% of the venture's equity and invest in cash. AOS would own 51% of the equity and contribute primarily its existing assembly and testing equipment as well as certain intellectual property related to the operation of the facility.

In other words: AOS kept control, but didn’t have to fund the whole buildout alone.

The joint venture was announced in 2015 and formalized in 2016, with plans for initial packaging production to commence in mid 2017. Before that, AOS intended to gradually relocate a majority of its assembly and testing equipment from its existing facility in Shanghai. Shanghai wasn’t being abandoned; it was slated to continue as a center for supply chain management, technology development, and high-value production. Over the longer term, the Joint Venture expected to construct a 12-inch wafer fabrication facility for power semiconductors.

Strategically, this move hit several targets at once. It lowered capital burden by sharing investment with government-linked partners. It pushed manufacturing into a lower-cost region. It strengthened AOS’s position with Chinese customers who were increasingly building around local supply chains. And it laid out a path—at least on paper—toward more advanced manufacturing capability that could matter for future generations of power devices.

While manufacturing capacity was being re-architected, the product portfolio was widening just as fast. AOS moved beyond discrete MOSFETs into power ICs, load switches, battery management solutions, and LED drivers. The through-line wasn’t “new markets for the sake of it.” It was leverage: reuse the company’s core strengths in power device physics and process know-how, and show up as more of a power management supplier—not just a catalog of individual components. That shift also tended to make customer relationships deeper and stickier.

Competition, of course, didn’t let up. Infineon, ON Semiconductor (now onsemi), and Nexperia were all active in adjacent territory. AOS’s edge was positioning: quicker than the giants when a customer needed customization, more proven than tiny startups when reliability mattered, and able to price aggressively because it had built manufacturing efficiency into the model. And with Oregon anchoring technology development and strategic production while China scaled cost-efficient volume manufacturing, AOS had a structural advantage that purely fabless competitors couldn’t easily replicate.

VI. Diversification & The Computing Renaissance

By 2016, the consumer-electronics flywheel that had powered AOS’s rise was starting to slow. Smartphone growth wasn’t what it used to be. Tablets had already peaked. LED lighting kept expanding, but pricing pressure was getting ugly. Mike Chang and the team could see where that road ended: more volume, less differentiation.

So they went looking for a market where power mattered more than marketing.

They found it in the cloud.

As Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud raced to build hyperscale data centers, the unit of competition shifted from devices in pockets to racks in warehouses. And in that world, power conversion isn’t a background detail—it’s a line item measured in real money. Every watt you waste turns into heat you have to remove, and electricity you have to pay for. Multiply that across thousands of servers, running 24/7, and even small efficiency gains become meaningful.

This is where AOS’s strengths lined up cleanly. The company wasn’t just selling stand-alone discrete components anymore. It was leaning into what it likes to call the integration of its discrete and IC semiconductor process technology, product design, and advanced packaging know-how—building power management solutions aimed at high-volume computing applications like PCs, graphics cards, data centers, and eventually AI servers.

But serving data centers meant leveling up.

Server power supplies demanded higher power density in smaller footprints. And on the motherboard, voltage regulator modules—the VRMs feeding CPUs and GPUs—needed to react to brutal, fast-changing loads without falling apart. That pushed demand toward DrMOS devices: integrated power stages that combine a driver and MOSFETs in a single package.

AOS positioned its DrMOS and Smart Power Stage offerings around what computing customers care about most: efficiency, robustness, and control. Smart Power Stage designs used advanced driver ICs to provide more accurate current and thermal monitoring back to the system. And AOS emphasized DrMOS robustness on the high-side MOSFET, built to handle the extreme current spikes that show up during the fast load transients typical for modern CPUs and GPUs.

DrMOS quickly became a battleground. Integrated power stages could deliver better efficiency and power density than stitching together discrete parts, and once a platform qualified, it tended to stay put. AOS put real effort into its designs here, knowing that the payoff wasn’t just a new product line—it was a new kind of customer relationship.

One example was the AOZ73004CQI, a 4-phase PWM controller that wasn’t limited to driving four DrMOS stages in a standard configuration. With AOS’s proprietary DrMOS design enabling precise turn-on timing, that controller could drive two or three DrMOS devices per PWM—letting designers scale into higher-power, cost-effective multiphase solutions with as many as 12 power stages.

The hard part was getting in. Computing customers—especially hyperscalers—were relentless about qualification. They tested components obsessively, because failures aren’t acceptable at data-center scale. But the payoff was exactly why AOS wanted this market: once qualified, switching becomes painful. Requalification costs time, money, and introduces risk. So unless a supplier stumbles badly, these sockets tend to stick.

That stickiness changed the business. Data center power solutions carried better pricing than many consumer applications. The engineering investment created real barriers to entry. And design wins offered longer, clearer visibility than the churn of consumer cycles.

The shift wasn’t a clean break—consumer and PC products still mattered—but the center of gravity moved. AOS was increasingly building for computing, and that path naturally set it up for the next wave that would define the early 2020s: AI infrastructure.

And by 2023, when Stephen Chang became CEO, the ambition was explicit: “I am excited to lead the AOS team and build on our differentiated technology and strong customer relationships to deliver sustainable growth and long-term value for our stakeholders, including realizing our one-billion-dollar annual revenue target and beyond,” he said.

VII. Geopolitical Shockwaves: Tariffs, Trade Wars, & Supply Chain Rewiring

The third major inflection point hit in 2018—and it didn’t come from a competitor or a new technology node. It came from Washington.

The Trump administration’s tariffs on Chinese goods, followed by China’s retaliation, jolted semiconductor supply chains. For AOS, the exposure was obvious: meaningful manufacturing in China, and plenty of customers elsewhere, including in the U.S. Overnight, the company had to operate in a world where the same part could be “cheap enough” or “too expensive,” depending on what side of a border it crossed.

AOS found itself in the crossfire. Products manufactured through the Chongqing joint venture and shipped to U.S. customers could pick up tariff costs that squeezed margins and weakened competitiveness. Just as importantly, customers started asking the questions that matter in semiconductors: What happens if this gets worse? Can you still ship? Where else can this be made?

Those questions turned an old decision into a new advantage.

The Oregon fab—bought years earlier, when the headline risk was mostly about yield ramps and fixed costs—suddenly looked like a strategic trump card. If you could build in Hillsboro, you could ship without tariff exposure, and you could offer U.S. customers a domestic manufacturing path when “country of origin” started showing up in procurement checklists.

AOS was explicit about what the Oregon site meant to the business. The company operates an 8-inch wafer fabrication facility in Hillsboro, Oregon—its Oregon Fab—and positioned it as critical for accelerating proprietary technology development, speeding new product introduction, and improving financial performance.

Management leaned into it. The company accelerated investment to expand capacity and capability at the Oregon fab, adding equipment and improving facilities to ramp production. In customer conversations, AOS could now offer something many mid-sized power semiconductor competitors couldn’t: a real “Made in USA” option for applications where that mattered.

AOS also framed Oregon as a platform, not a one-off. The company continued expanding the Oregon fab by investing in new equipment and expanding factory facilities, which it expected would positively impact future product development and revenue. Management said it intended to keep exploring ways to expand manufacturing capabilities—including acquiring existing facilities, forming joint ventures or partnerships, and applying for government funding or grants available in the semiconductor industry.

Then came 2020, and the world stress-tested every supply chain at once.

COVID-19 froze factories, clogged logistics, and triggered shortages that rippled across industries. Semiconductor supply became a headline problem: automakers idled lines, and electronics lead times stretched out painfully. In that environment, AOS’s “own some capacity” philosophy paid off again. With manufacturing in both Oregon and China, the company had more levers to pull than pure fabless peers who were entirely at the mercy of foundry allocation.

None of this was free. Running meaningful operations across two geographies meant real complexity: different regulatory regimes, different labor markets, different logistics realities. Currency swings, coordination costs, and day-to-day execution friction were part of the deal. And the Chongqing joint venture—valuable as it was for serving China and broader Asia—also represented a form of geopolitical exposure that wasn’t going away.

By 2025, you could see AOS starting to rebalance that risk.

Alpha and Omega Semiconductor announced it had entered into an equity transfer agreement with a strategic investor to sell approximately 20.3% of the outstanding equity interest of its joint venture in Chongqing, China (“CQJV”). Under the agreement, the investor would pay AOS total cash consideration of $150 million in four installments. AOS expected to close the proposed sale before the end of 2025. Before the sale, AOS owned approximately 39.2% of CQJV, and the transaction represented roughly half of its stake.

When AOS announced the deal in July 2025, CEO Stephen Chang framed it as a planned monetization step—not an abandonment. “Our longstanding partnership with CQJV remains strong and continues to play an important role in our supply chain. Today's sale is consistent with the monetization path we outlined years ago and demonstrates our commitment to the ongoing value creation for our shareholders. By realizing a portion of the value we have built with CQJV, we can reinvest in the people, tools, and intellectual property that expand our product portfolio, while preserving the supply partnership that underpins our growth strategy,” he said.

What came out of this period was a company that looked less like a nimble power-chip upstart and more like a manufacturer with options. Dual-geography manufacturing stopped being an operational quirk and became a competitive weapon. Oregon positioned AOS to meet growing demand for U.S.-based supply. Chongqing remained a critical pillar for Asian markets—while AOS began, deliberately, to turn part of that embedded value into fuel for whatever came next.

VIII. The Electrification Mega-Trend: EVs, Renewables, & AI Infrastructure

The fourth inflection point is really a convergence. Electric vehicles, renewable energy, and AI infrastructure look like separate worlds, but they share the same underlying constraint: they’re all power-hungry systems where efficiency is destiny. If you can’t move electricity cleanly—convert it, regulate it, and waste as little of it as possible—you can’t hit the performance, cost, or reliability targets that these markets demand.

Start with EVs. For power semiconductors, electric vehicles don’t just add demand—they create entirely new sockets. Every EV is packed with power conversion blocks: onboard chargers that turn AC from the grid into DC to charge the battery, DC-DC converters that step voltage down for the vehicle’s many subsystems, battery management systems that monitor and balance cells, and traction inverters that drive the motors. Each one is a harsh electrical environment, and each one is a chance for a supplier with the right technology to get designed in for years.

AOS has positioned itself for that reality with automotive-qualified devices, including high-voltage offerings like 1200V αSiC MOSFETs. As the company put it:

"For the continued transformation of transportation to EV technology, vehicle manufacturers making efforts to increase range and reduce the time spent charging. With our release of these automotive qualified 1200V αSiC MOSFETs, AOS can provide designers with next generation semiconductor technology to increase these efficiency targets. Our customers have selected our technology due to the combination of product performance, reliability, and volume capable supply chain."

These automotive-grade MOSFETs are aimed at the kinds of systems where EV designers feel the pain most—power delivery inside the vehicle, battery management systems, and high-performance inverters for e-mobility, including BLDC motor applications.

The catch, of course, is that automotive is the hardest room to get into. Qualification cycles are long and unforgiving—often even more demanding than data center deployments. But that’s also the payoff: once a part is qualified into a platform, it can translate into multi-year production as vehicle programs run roughly five to seven years. It’s slow to earn, and hard to dislodge.

Renewables have similar “high stakes, long runway” dynamics. Solar inverters have to convert DC from panels into AC for the grid efficiently and reliably. Energy storage systems need bidirectional conversion for charging and discharging. And grid-scale deployments push high voltage and high current, which puts brutal demands on device robustness and thermal performance.

AOS has leaned into this with its high-voltage Super Junction MOSFET lineup. In the company’s words:

Power Supply and Renewable Energy: A significant solution in AOS' growing High-Voltage Super Junction MOSFET portfolio is its industry-leading optimized αMOS5™ 600V to 700V Super Junction MOSFETs, which helps designers achieve efficiency and density goals while satisfying budget goals. Featuring fast switching, a robust UIS/body diode, and ease of use, these state-of-the-art MOSFETs meet the latest server, telecom rectifier, solar inverter, EV charger, gaming, PC, and universal charging/PD design requirements.

But the electrification wave that’s captured the most attention—especially from investors—is AI infrastructure. AI data centers are not just “more servers.” They’re power-intensive factories for computation, and the scaling curves are steep. Deloitte has estimated that power demand from AI data centers in the United States could grow more than thirtyfold by 2035, rising to 123 gigawatts from 4 gigawatts in 2024. And compared to traditional facilities, AI data centers can draw dramatically more energy per square foot.

That demand shows up as a massive semiconductor opportunity. The total semiconductor market for data centers is projected to grow from $209 billion in 2024 to $492 billion by 2030, driven by generative AI, high-performance computing, and hyperscaler expansion.

Underneath those big numbers is a very specific engineering problem: feeding power to GPUs. Every generation pushes harder—more compute, more current, tighter margins for error. NVIDIA’s systems that power training and inference need enormous, efficient power delivery, and as power consumption rises, the tolerance for wasted energy and heat only shrinks. That is exactly the kind of challenge AOS has been building toward with its power stages and controllers.

AOS has pointed to products like its AOZ73004CQI, which it described as the world’s first 4-Phase controller for Blackwell GPUs, with full OpenVReg (Open Voltage Regulator) OVR4-22 compliance. The company emphasized that AOZ73004CQI’s cycle-by-cycle current limit meets the overcurrent limit (OCL) specification, helping safely throttle GPU power to support performance.

And it’s not just controllers. The AI server DrMOS market—integrated power stages that combine MOSFETs and a driver IC to improve efficiency and power density—is expected to expand meaningfully over the rest of the decade. One forecast projects it growing from about $306 million in 2024 to $739 million by 2030, driven by the push toward higher-density server power delivery.

AOS has also talked about supporting 800-volt DC architecture for next-generation AI data centers, aiming at higher efficiency and the next system design cycles. Read that as the company trying to get ahead of where AI infrastructure is going—not just shipping into today’s racks, but positioning for the power architectures that could define the next wave of “AI factories.”

IX. The AI Boom & Data Center Power Wars

The ChatGPT moment in late 2022 didn’t just spark a new app category. It triggered an AI infrastructure arms race. Hyperscalers pulled forward data center builds. Enterprises raced to add AI capabilities. And the semiconductor supply chain—already trained by a decade of “just-in-time” thinking—had to respond to demand that ramped faster than most forecasts could keep up with.

In that scramble, power delivery stopped being background plumbing and became the constraint everyone could feel. AOS leaned into the moment with parts aimed directly at the AI server power stack. One example was the AONK40202, a 25V MOSFET introduced in DFN3.3x3.3 Source-Down packaging. The pitch was straightforward: higher power density for DC-DC applications, with packaging choices that make life easier for board designers. Source-Down increases the source contact area to the PCB for better electrical and thermal performance, and the center gate pin layout helps simplify routing and shorten the gate-driver connection.

Why does that matter? Because AI racks turned the power problem from “important” to “existential.”

NVIDIA’s GPUs now draw hundreds of watts each, and an AI server rack can pull on the order of tens of kilowatts—far above traditional enterprise racks. With NVIDIA’s Blackwell generation and the GB200NVL72 rack design in 2024, peak rack power density rose to about 132 kW. And the industry is already talking about future systems—Blackwell Ultra and Rubin-era designs—pushing into the hundreds of kilowatts per rack, with dramatically higher GPU counts by 2026–2027.

At those levels, you don’t get to be sloppy anywhere in the chain. Power supplies have to convert AC to DC with ruthless efficiency. VRMs have to deliver stable power through brutal, fast load swings. And every part has to survive punishing thermal conditions without introducing noise, instability, or failure risk.

AOS’s answer has been to show up with more of the stack—not just discrete devices. For AI server and graphics card applications built around 12V inputs, the company offers DrMOS parts like AOZ5310NQI-A, positioned for GPU power efficiency. And on designs powered by 20V inputs, controllers can pair with DrMOS power stages such as AOZ5316NQI, AOZ5317NQI, and AOZ5318NQI for laptop GPU applications. AOS has pointed to its TrenchFET-based MOSFETs inside these DrMOS devices as a way to enhance overcurrent-limit capability.

The results have started to show up in the mix. Computing became AOS’s largest segment, and in the September quarter it represented a little over half of total revenue, with segment revenue up meaningfully year over year and modestly sequentially. That’s the upside of getting pulled into AI and graphics sockets. The downside is the other side of semiconductors: the cycle. More concentration in computing means more exposure when customers pause to digest inventory or when a platform transition creates a temporary air pocket.

And that’s happening in real time. “Looking ahead to December, we expect computing segment revenue to decline nearly 20% sequentially,” management said, referring to fiscal Q2 2026—pointing to a post-holiday slowdown and ongoing digestion in AI and graphics cards.

At the same time, AOS is fighting in a crowded arena. The AI server power market has become a design-win knife fight, with Vishay, Infineon, onsemi, Renesas, Texas Instruments, and Monolithic Power Systems all competing for sockets at hyperscalers and server OEMs. Market profiles of the AI server DrMOS space regularly name a long list of contenders, from the giants to specialists, with AOS firmly in the mix.

So what’s the differentiation when everyone wants in? AOS’s pitch is a bundle: move fast, customize when the customer needs it, and back it with a supply chain that isn’t single-geography fragile. Combine that with an integrated portfolio—controllers, power stages, and discretes that can be designed together—and AOS isn’t just selling parts. It’s trying to become the power partner you don’t swap out mid-cycle.

That’s the bet. Quarterly swings are inevitable. But if AI infrastructure keeps scaling the way the industry expects, the long-term tailwind is real—and power delivery is one of the most valuable places to be standing.

X. Business Model Deep Dive & Operations

To really understand AOS, you have to look past the catalog of parts and focus on the machine that builds them. This isn’t a pure fabless design shop, and it’s not a fully integrated giant either. It’s a carefully balanced system—built to keep costs competitive, protect the process know-how that actually differentiates power devices, and give customers confidence that AOS can deliver when the cycle turns.

At the center of that system is a three-part manufacturing model.

First, AOS runs proprietary manufacturing processes across its own footprints: the Oregon Fab and the Chongqing Fab. Second, it supplements that capacity with third-party foundries that fabricate wafers. The main external partner is Shanghai Hua Hong Grace Electronic Company Limited (“HHGrace”) in Shanghai, which has manufactured wafers for AOS since 2002. HHGrace produced 3.8%, 9.6%, and 10.3% of the wafers used in AOS products in the fiscal years ended June 30, 2024, 2023, and 2022.

The Oregon fab plays a very specific role. It’s where AOS ties design and manufacturing tightly together—driving technology development, running proprietary processes, and supporting strategic production for U.S. customers. By the time Jireh passed its 10-year milestone, it wasn’t an experiment anymore. It had become a cornerstone of the company’s identity, and AOS kept investing to expand what the site could do and how much it could produce.

Chongqing, meanwhile, is the scale engine for Asia. The joint venture provides volume manufacturing capacity for Asian markets and supports packaging and testing operations, with a longer-term goal of adding 12-inch wafer fabrication capability. And when demand spikes or a legacy process is better handled elsewhere, third-party foundries cover overflow production and specific needs that don’t justify tying up AOS’s owned capacity.

That’s also why AOS has been careful to message the Chongqing stake sale. The company has emphasized that selling down part of its CQJV ownership would not change its operational relationship with the venture—and that it would continue benefiting from CQJV’s production capacity. The intent was to free up cash to fund technology investment, R&D, and potential acquisitions, while preserving the supply partnership that supports the broader strategy.

On the R&D side, AOS’s differentiation is rooted in the unglamorous parts of semiconductor progress: device physics and packaging. That means understanding how material structures, doping profiles, and geometries affect electrical performance—and then pairing that with packaging technology that increasingly determines thermal performance and power density. AOS has consistently positioned its advantage as the integration of its discrete and IC semiconductor process technology, product design, and advanced packaging know-how, all aimed at building higher-performance power management solutions.

Commercially, AOS sells the way most serious semiconductor suppliers sell: by getting designed in. Engineers work with customers early in the development cycle to nail down power requirements. A design win then turns into qualification—stress testing, reliability work, and the long checklist that customers use to avoid ugly surprises in the field. Once a device clears that bar, it tends to stay in production for the life of the customer’s platform—often three to five years or longer. That’s the “moat” in this business: not a brand, but the friction of switching.

Financially, the profile reflects both the opportunity and the grind of power semiconductors. Revenue was $161.3 million in fiscal Q4 2024, flat year over year and up 7.5% sequentially. GAAP gross margin was 25.7%, down from 27.6% a year earlier and up from 23.7% in the prior quarter. Non-GAAP gross margin was 26.4%.

Those mid-20s gross margins are a reminder of the competitive intensity in the category. AOS has to keep spending to stay differentiated, too. Operating expenses—largely R&D and sales support—run at roughly a quarter of revenue. GAAP operating expenses were expected to be $46.5 million, plus or minus $1 million, and non-GAAP operating expenses were expected to be $39.5 million, plus or minus $1 million.

As of December 2025, the company had approximately 2,430 employees.

This operating model also depends on leadership continuity, and AOS has treated succession as part of execution—not as an afterthought. In 2023, the Board approved a transition plan: Dr. Mike Chang moved from Chief Executive Officer and Chairman to Executive Chairman, while Stephen Chang—then President—became Chief Executive Officer. The transition became effective on March 1, 2023.

Stephen C. Chang has served as CEO since March 2023. Before that, he had been President since January 2021, and earlier held a series of roles spanning product line management and marketing, including Executive Vice President of Product Line Management, Senior VP of Marketing, VP of the MOSFET Product Line, and Senior Director of Product Marketing. With more than 20 years in the industry, he leads AOS’s business strategy along with product and technology development, sales and marketing, manufacturing operations, and supply chain management.

And the founder never really left the building. Dr. Mike Chang remains deeply involved as Chairman of the Board and Executive Vice President of Strategic Initiatives. He served as Executive Chairman from March 2023 to March 2025, and before that was CEO from the company’s founding until March 2023. In practice, it’s a deliberate pairing: a new CEO focused on day-to-day execution, and a founder still shaping the long arc of strategy.

XI. Competitive Landscape & Industry Structure

Zoom out, and you can see why AOS has been able to find oxygen. Power semiconductors aren’t a niche anymore. The market is expected to reach $56.87 billion in 2025 and grow to $74.36 billion by 2030. Different research firms will argue over the exact figures, but they all agree on the direction: electrification, AI infrastructure, and relentless energy-efficiency requirements are turning power chips into a long-duration growth category.

The interesting part is that this isn’t a clean “new replaces old” story. Silicon still generated 78.1% of revenue in 2024. Even with real physical limits, silicon keeps winning in huge swaths of the market because the ecosystem is mature, the supply chain is deep, and innovation hasn’t stopped—superjunction MOSFET improvements keep silicon highly competitive, especially at 650V and below. Meanwhile, wide bandgap is carving out the high-growth edge. GaN is smaller today, but it’s growing fast—around a 9.17% CAGR—finding traction in places like mobile fast chargers, 5G base stations, and residential solar micro-inverters.

That sets the stage for a competitive landscape with brutal range.

At the top sit the giants: Infineon, ON Semiconductor, STMicroelectronics, and Texas Instruments, with massive R&D budgets, broad portfolios, and the kind of manufacturing scale that lets them lean on efficiency, long-standing customer relationships, and brand credibility. They can be slow, but they’re hard to outspend and hard to outlast.

Then there’s the long list of serious players that fill out the rest of the battlefield: Infineon Technologies, Innocone, Microchip Technology, MINEBAE MITSUMI Inc., Mitsubishi Electric, Navitas Semiconductor, Nexperia, Onsemi, Power Integrations, Renesas Electronics, ROHM, STMicroelectronics, Texas Instruments, Toshiba Electronic Devices, Transphorm, Vishay Intertechnology, and Wolfspeed. In that context, AOS shows up in the Americas region—smaller than the giants, but very much in the conversation.

AOS lives in the mid-market tier, alongside specialists like Power Integrations, Monolithic Power Systems, and Diodes Incorporated. In competitive sets around AOS, you’ll also see names like Taiwan Semiconductor, Microchip Technology, MagnaChip Semiconductor, and Diodes—companies that pick their spots and try to win with focus rather than sheer scale.

So what’s AOS’s edge when it can’t win an arms race?

First, the fab-lite model. Owning meaningful capacity gives AOS a level of control and flexibility that pure fabless rivals don’t have—especially when supply gets tight or when a customer needs something slightly off the standard menu.

Second, manufacturing geography. In a world where procurement teams increasingly ask “Where is it made?” AOS can answer with more than one option. Oregon plus China isn’t just an operational detail; it’s a sales tool and a risk hedge.

Third, the company’s push toward integrated solutions. AOS doesn’t want to be swapped out part-by-part. The more it can offer controllers plus power stages plus discrete components that work together, the more it can create system-level value—and the harder it becomes for a customer to replace it with a single competitor’s catalog equivalent.

Fourth, speed and customization. Big competitors can be formidable, but they can also be slow to react or unwilling to bend for smaller, specialized design requirements. AOS has repeatedly positioned itself as the supplier that will engage, iterate, and support the customer through qualification.

But the vulnerabilities are just as real.

Scale still matters in semiconductors. AOS doesn’t have the R&D budgets or manufacturing scale of competitors with ten times the revenue, and that can show up in everything from pricing pressure to how fast you can move into the next technology wave.

And that next wave is the biggest strategic risk: wide bandgap. Silicon carbide and gallium nitride threaten chunks of the silicon profit pool, especially in high-performance EV and energy applications. The SiC market, in particular, is concentrated—Infineon, STMicroelectronics, Wolfspeed, Onsemi, and ROHM control more than 90% of global revenue. That kind of dominance is what concentrated capital spending and deep process IP looks like in practice. AOS is developing SiC and GaN capabilities, but it’s still playing from behind.

China is another pressure point. Domestic competitors like BYD Semiconductor are gaining strength with cost advantages at home, government-supported capex, and, in some cases, captive demand from booming EV ecosystems. As these companies scale, they’re not just competing inside China—they’re increasingly showing up in export markets too.

And finally, there’s consolidation. M&A has repeatedly reshaped the playing field—ON Semiconductor’s acquisition of Fairchild, Infineon’s deal activity, and the broader trend toward fewer, larger competitors. AOS has stayed independent, which preserves strategic flexibility, but also means it can’t rely on acquisitions to rapidly buy scale the way others do.

XII. Playbook: Business & Strategic Lessons

Alpha and Omega Semiconductor’s 25-year journey offers lessons that travel well beyond one company—or even one corner of the chip industry.

Vertical integration timing matters enormously. In 2012, AOS bought the Oregon fab at a moment when others were doing the opposite—selling factories, going lighter, getting “asset efficient.” On paper, it looked like self-inflicted pain: a fabless company taking on the fixed costs and operational burden of a fab. In practice, it became one of AOS’s most durable advantages. The fab helped the company move faster on process and product development, gave it more control when supply tightened, and later turned into a real strategic asset as “where it’s made” started to matter. The lesson isn’t “always integrate.” It’s that integration should be a strategy decision, not a religion.

Geopolitical resilience requires advance preparation. AOS didn’t need a crystal ball to benefit from its dual-geography footprint. It just needed options. When tariffs hit and supply chains started to fragment, AOS could offer customers alternatives that single-country supply chains couldn’t. Building that kind of resilience costs money and adds complexity, and the payoff often looks invisible—right up until the day it isn’t.

Market timing pivots require pattern recognition. The move from consumer electronics into computing and data centers, and then into EV and AI infrastructure, wasn’t random diversification. It tracked where the value in power management was moving. Each shift demanded new products, new packaging, and new customer relationships—earned through long design-in cycles, not marketing. The lesson is that in semiconductors, standing still is a strategy too—and usually a bad one. The winners keep re-placing their bets as end markets evolve.

Founder-led longevity creates institutional memory. Dr. Mike Chang’s long run—from founding through IPO, multiple pivots, and succession—created continuity that’s rare in semiconductors. That matters because the best strategic moves in this industry often look wrong in the moment and only make sense over a full cycle. The CEO transition to Stephen Chang preserved that long-term orientation while adding a fresh operator’s lens.

Analog moats differ from digital moats. Power semiconductors don’t win by riding Moore’s Law. They win through device physics, process tuning, packaging, and reliability—the hard-earned, often unsexy craftsmanship of making power run cooler, faster, and longer. That shifts the competitive game: progress is more incremental, manufacturing know-how matters more, and real advantages can last longer than investors trained on digital scaling dynamics might assume.

Customer stickiness from design wins creates visibility. In power, getting designed in isn’t a nice-to-have—it’s the whole business model. Qualification takes time, switching is painful, and once a part is inside a platform, it tends to stay there. That creates a kind of embedded optionality: future revenue that isn’t obvious from today’s numbers, but becomes predictable once a design win ramps.

Semiconductor cycles are brutal but survivable. AOS lived through the downturns—early-2000s weakness, the financial crisis, and the 2022–2023 inventory correction—and came out the other side intact. The common thread wasn’t luck. It was financial flexibility, restraint on leverage, and a willingness to protect core capabilities during the trough so the company could actually participate in the next upturn. In this industry, plenty of companies win the boom and lose the bust. Surviving to fight the next round is its own edge.

XIII. Porter's Five Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

If you want to pressure-test AOS’s strategy, it helps to run the company through two lenses that force clarity: Porter’s Five Forces (what the industry does to you) and Hamilton’s 7 Powers (what you can uniquely do back).

Threat of New Entrants: MODERATE-LOW

Power semiconductors are not an easy market to casually enter. You need serious capital, specialized equipment, and—more importantly—process knowledge that only accumulates through years of iteration. Even if a newcomer can build or access manufacturing, they still run into the slow grind of qualification. Customers don’t swap power devices lightly, and design-in cycles can stretch for years.

That said, the barrier isn’t airtight. Chinese competitors with government backing can compress the normal constraints, especially in domestic markets. So the moat is real, but it’s not a castle wall.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

The upstream supply chain has leverage. Silicon wafers are concentrated among suppliers like Shin-Etsu and SUMCO. And the equipment layer—Applied Materials, Lam Research, ASML—has plenty of power because fabs can’t run without their tools and service ecosystems.

AOS isn’t uniquely vulnerable here, though. Its dual-fab footprint and mix of internal and external manufacturing relationships give it at least some flexibility. It can’t escape supplier power, but it isn’t boxed into a single choke point either.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-HIGH

AOS sells into customers that know how to negotiate: hyperscalers, automotive OEMs, and large consumer electronics brands. In high-volume programs, pricing pressure is a permanent feature, not a temporary phase.

But buyer power isn’t absolute, because qualification changes the rules. Once a part is designed in and proven reliable, switching costs rise sharply. And when AOS is delivering a custom solution rather than a catalog commodity, it can hold better pricing. So buyer power is high at the start of a relationship—and often lower once the part is embedded in a platform.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW-MODERATE

The big substitution story in power is silicon versus wide bandgap. Silicon MOSFETs are gradually being displaced by silicon carbide in higher-voltage use cases and by gallium nitride in higher-frequency applications. Those technologies win where performance demands justify higher cost, and that’s why they’re gaining traction in EVs and high-performance power supplies.

AOS is developing SiC and GaN capabilities, but it trails the leaders. For most applications, silicon is still the price-performance default. The threat is real, but it’s uneven—and it plays out over time rather than overnight.

Industry Rivalry: HIGH

This is the force you feel every day in power semiconductors. The market is fragmented, with giants and specialists constantly colliding in overlapping segments. Differentiation tends to be temporary because competitors work quickly to match features, packaging, or performance. Consolidation has created bigger, better-capitalized rivals, and global competition only increases the intensity.

Rivalry is high, and it’s not easing.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Assessment:

Scale Economies: MODERATE. Scale helps—better fab utilization, more leverage on R&D, and more ability to spread fixed costs. But power semis aren’t winner-take-all. Multiple players can survive at different sizes. AOS gets some benefits from its scale in selected segments, but it can’t match the absolute scale advantages of the giants.

Network Effects: NONE. This is classic B2B semiconductors. One customer using AOS doesn’t inherently make AOS more valuable to the next customer.

Counter-Positioning: WEAK-MODERATE. The fab-lite approach was a meaningful stance against both pure fabless players and fully integrated incumbents—especially early on. Over time, pieces of that posture have been copied. The dual-geography manufacturing footprint increasingly looks like a form of counter-positioning in a geopolitically fractured world, but it’s still replicable for competitors willing to spend and execute.

Switching Costs: STRONG. This is the center of gravity for AOS’s moat. Qualification is slow, expensive, and risk-heavy. Once a part is proven in the field—especially in computing and automotive—customers face meaningful cost and reliability risk if they switch. That stickiness supports multi-year revenue and reduces churn.

Branding: WEAK. Customers don’t buy AOS because the logo carries prestige. They buy because the part meets spec, ships reliably, and is priced right. Reputation matters, but it doesn’t create the kind of pricing umbrella you see in consumer brands.

Cornered Resource: WEAK-MODERATE. AOS has real proprietary process and device IP, and engineering talent that can’t be cloned instantly. The Oregon fab is also a distinctive asset for U.S.-based supply. But none of these are permanently cornered in the sense that competitors can never replicate them.

Process Power: MODERATE. AOS’s ability to execute in a fab-lite model—moving quickly, customizing for customers, and translating engineering into shippable product—is a real advantage built through repetition. It’s not invincible, but it’s not trivial to match either.

Summary: AOS’s most durable advantage is Switching Costs—earned through long design-in and qualification cycles—reinforced by Process Power in speed and customization. Its manufacturing footprint contributes a form of emerging Counter-Positioning as supply-chain geography matters more. What AOS does not have is the brute-force advantage of massive Scale Economies, or the structural lift of branding or network effects. It’s defensible where it’s chosen to compete, but it isn’t dominant by default.

XIV. Bull vs. Bear Case

The Bull Case:

The optimistic read on AOS starts with the simplest argument in semiconductors: the demand backdrop is getting bigger, not smaller. EV adoption is still early globally, with EV penetration projected to reach more than half of new car sales by 2035. And every EV pulls far more power semiconductor content than an internal combustion vehicle ever did. At the same time, AI infrastructure buildouts continue to accelerate as hyperscalers pour capital into new capacity. In 2024, the total semiconductor market for data centers reached $209 billion across compute, memory, networking, and power, and projections take it to nearly $500 billion by 2030. Layer in renewables and grid modernization—both of which are basically power-electronics spending programs—and you get a set of tailwinds that can carry a mid-sized power specialist a long way.

AOS’s setup is also easy to miss if your mental model of “semiconductors” is leading-edge logic and memory. Silicon still generated 78.1% of revenue in 2024, and silicon MOSFETs remain the workhorse for most power applications. That’s AOS’s home turf. The shift to wide bandgap materials doesn’t have to be a cliff; it can be a runway, buying time for AOS’s silicon franchise while the company builds out SiC and GaN capability where it matters.

Then there’s the part of the story that has become newly valuable: geography. AOS is one of the few mid-sized power semiconductor companies with meaningful U.S. manufacturing. As reshoring accelerates and more customers want a domestic supply-chain option, the Oregon fab becomes more than a nice-to-have. It’s a sales advantage. In the right programs, it can support better pricing and share gains versus competitors whose manufacturing footprint is concentrated in Asia.

On top of that, design wins create the kind of visibility investors always want but rarely get in semiconductors. Automotive and data center sockets don’t show up overnight—the qualification cycles are long—but once you’re qualified, you’re hard to dislodge. If AOS keeps stacking wins, today’s R&D and product investments can turn into multi-year revenue streams that are difficult for competitors to unwind.

The CQJV stake sale helps tell a cleaner capital story, too. In July 2025, AOS announced a $150 million sale of roughly half its stake, showing it could monetize value it had built while preserving the operational partnership. Management has said the proceeds will support technology investments, R&D, and potential acquisitions—capital to reinvest without issuing new shares.

Put it together and you get the valuation argument: AOS appears to trade at a discount to power semiconductor peers despite a differentiated manufacturing footprint and exposure to big, durable demand waves. If execution stays solid and the secular tailwinds keep blowing, multiple expansion could layer on top of earnings growth.

And finally, there’s continuity. AOS blends founder-era strategic memory with a CEO focused on execution. Dr. Mike Chang’s continued involvement alongside Stephen Chang’s operating leadership gives the company a stability many tech businesses don’t manage—especially across cycles.

The Bear Case:

The bearish read starts with the oldest rule in this industry: semiconductors are cyclical, no matter how good the story sounds. Even in the middle of the AI buildout, AOS has had to flag near-term air pockets. “Looking ahead to December, we expect computing segment revenue to decline nearly 20% sequentially,” management said, pointing to the volatility that comes with inventory digestion, platform transitions, and customer budget pacing. Secular growth doesn’t prevent ugly quarters.

Then there’s technology risk. Silicon carbide and gallium nitride are taking share in the highest-value applications, and the market structure is unforgiving. The silicon carbide power semiconductor market is concentrated, with the five largest suppliers holding over 90% of revenue in 2024. Between fab capex, crystal growth expertise, and deep patent portfolios, the barriers are real. AOS is developing wide bandgap products, but it trails established leaders like Wolfspeed, Infineon, and onsemi. If adoption accelerates faster than expected, silicon-heavy suppliers can see margins compress and sockets migrate.

China is another double-edged sword. Even after the CQJV stake sale, AOS still has meaningful revenue exposure and manufacturing capacity tied to China. A worsening U.S.–China relationship could bring fresh tariffs, export-control complexity, or simple customer pressure to shift sourcing away from Chinese manufacturing. The Oregon fab helps for U.S. programs, but the reverse can also be true: Asian customers may increasingly favor Chinese suppliers.

Scale also matters more than investors sometimes admit. Giants like Infineon, ON Semiconductor, and STMicro can spend multiples of AOS’s R&D budget, and in a technology transition, resources buy speed. When pricing gets competitive—especially in more standardized, high-volume segments—smaller players can get squeezed harder.

Customer concentration adds another layer of volatility. A handful of large customers can represent a meaningful portion of revenue, and hyperscalers are famous for demanding pricing concessions and insisting on second sources. Lose a socket, or see a customer pause orders, and the impact can be immediate.

Margins are not guaranteed to improve, either. Mid-20s gross margins reflect a competitive category. As data center and automotive volumes scale, customers often push for price reductions. Operating leverage can help at higher revenue, but there’s no law that says a power semiconductor supplier gets to 30%+ gross margin.

The fab-lite model is also capital-hungry by design. AOS can’t operate like a pure fabless company that simply rides foundry capacity and returns more cash to shareholders. It has to keep investing in manufacturing capability and equipment, which raises the fixed-cost burden and limits flexibility.

Finally, Chinese competitors are getting stronger. Companies like BYD Semiconductor can lean on domestic cost advantages, government-supported capex, and captive EV demand. That combination can win share inside China and then export pressure outward through aggressive pricing.

Key Metrics to Watch:

For investors monitoring AOS’s trajectory, three KPIs matter most:

-

Computing segment revenue growth and mix: Computing is now over half of revenue. If that segment keeps growing—especially in AI- and graphics-related applications—it can pull the whole company forward. If it slows, it can signal demand weakness, inventory digestion, or competitive losses.

-

Non-GAAP gross margin trends: Gross margin is the scoreboard for pricing power, manufacturing efficiency, and mix. A move toward 30%+ would suggest AOS is winning higher-value sockets and holding pricing. A slide toward 20% would imply commoditization and intensifying competition.

-

Oregon fab utilization and capacity investment: Oregon is the strategic asset—both for U.S. supply-chain positioning and for process technology development. Utilization, expansion investment, and new process introductions from the facility will signal how effectively AOS is turning that footprint into durable advantage.

XV. Epilogue & The Road Ahead

As 2025 drew to a close, Alpha and Omega Semiconductor stood at a familiar kind of turning point: not a single “make-or-break” moment, but a stack of small indicators that the strategy was holding up.

The company reported results for the fiscal fourth quarter and year ended June 30, 2025 with Q4 revenue of $176.5 million and gross margin of 23.4%. For the full fiscal year, revenue came in at approximately $696 million, up from $657 million in fiscal 2024—modest growth, but meaningful in context. After the inventory correction that weighed on the industry in calendar 2023, “stabilization” is what progress looks like before the next leg up.

Then came a concrete reminder that AOS had built real, monetizable value in its China footprint. In fiscal Q1 2026, the company received the first $94 million payment from the $150 million sale of a 20.3% equity interest in its China joint venture, bringing cash to $223.5 million at the end of the quarter. More than the headline number, it gave AOS something every semiconductor company wants heading into an uncertain cycle: options. Technology investment. Potential acquisitions. Or, if the setup is right, opportunistic share repurchases.

At the product level, the company kept aligning itself with where the puck is going, not where it’s been. AOS described itself as supporting 800 VDC power architecture for next-generation AI factories with innovative SiC and GaN, power MOSFET, and power IC solutions—an explicit bet that the data center buildout won’t just scale in size, but evolve in how power is delivered and managed.

That tees up the real question hanging over the next chapter: can AOS break into the next tier? Management has talked about a billion-dollar annual revenue target and beyond. To get from “almost $700 million” to “$1 billion-plus,” and then to something like a $2 billion company, the formula likely isn’t one magic design win. It’s a combination of riding the secular tailwinds, expanding credibly into wide bandgap materials, and potentially using acquisitions to speed up capability-building or market access.

Which raises the menu of strategic paths in front of them.

Staying independent and compounding the current playbook offers control and continuity, but it can also cap how fast the company can scale. Being acquired by a larger player could unlock bigger capital and faster investment—at the cost of independence. Or AOS could become the buyer: acquisitions in SiC/GaN technologies or adjacent product lines could accelerate the roadmap, though integration risk is real in any semiconductor deal.

Step back far enough, and the thesis is simple. Power semiconductors are infrastructure for the electrification of everything. Electric vehicles, data centers, solar installations, and grid-scale storage all run through the same choke point: efficient power conversion and delivery. As the world decarbonizes and digitizes, demand for power management doesn’t just grow—it compounds. AOS has positioned itself as a leveraged bet on electrification and AI, two secular waves that are reshaping the entire industry.

The most interesting surprises in this story weren’t about a single breakthrough product. They were strategic. The value of geopolitical foresight—making manufacturing investments before tensions became obvious—created options that later became selling points. The timing of vertical integration—buying capacity when industry orthodoxy preached fabless—was contrarian, and it worked. And the stickiness of design-ins—multi-year visibility earned through qualification—remains a form of business quality that’s easy to miss if you’re only watching quarterly swings.

In the end, Alpha and Omega Semiconductor is a story of strategic adaptability: fabless to fab-lite, consumer to computing to EV and AI, China-heavy manufacturing to a dual-geography footprint. In semiconductors—an industry where consolidation has erased countless companies and giants dominate mindshare—survival is already an achievement. Thriving takes reinvention, again and again.

Dr. Mike Chang founded AOS 25 years ago with a conviction that power semiconductors would matter, and that customers would reward a supplier that could move fast and deliver reliably. The company he built has navigated crashes, recessions, trade wars, pandemics, and relentless competition—and arrived at what may be the most consequential decade yet for power management. Whether that positioning translates into shareholder returns will come down to execution, but the strategic foundation looks real.

For anyone watching the quiet bottlenecks that make electrification and AI possible, AOS is worth paying attention to. Not because it’s the biggest player or the most dominant. But because it represents an alternative path: mid-scale, strategically positioned, geographically diversified, and stubbornly independent in an industry that usually rewards consolidation.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music