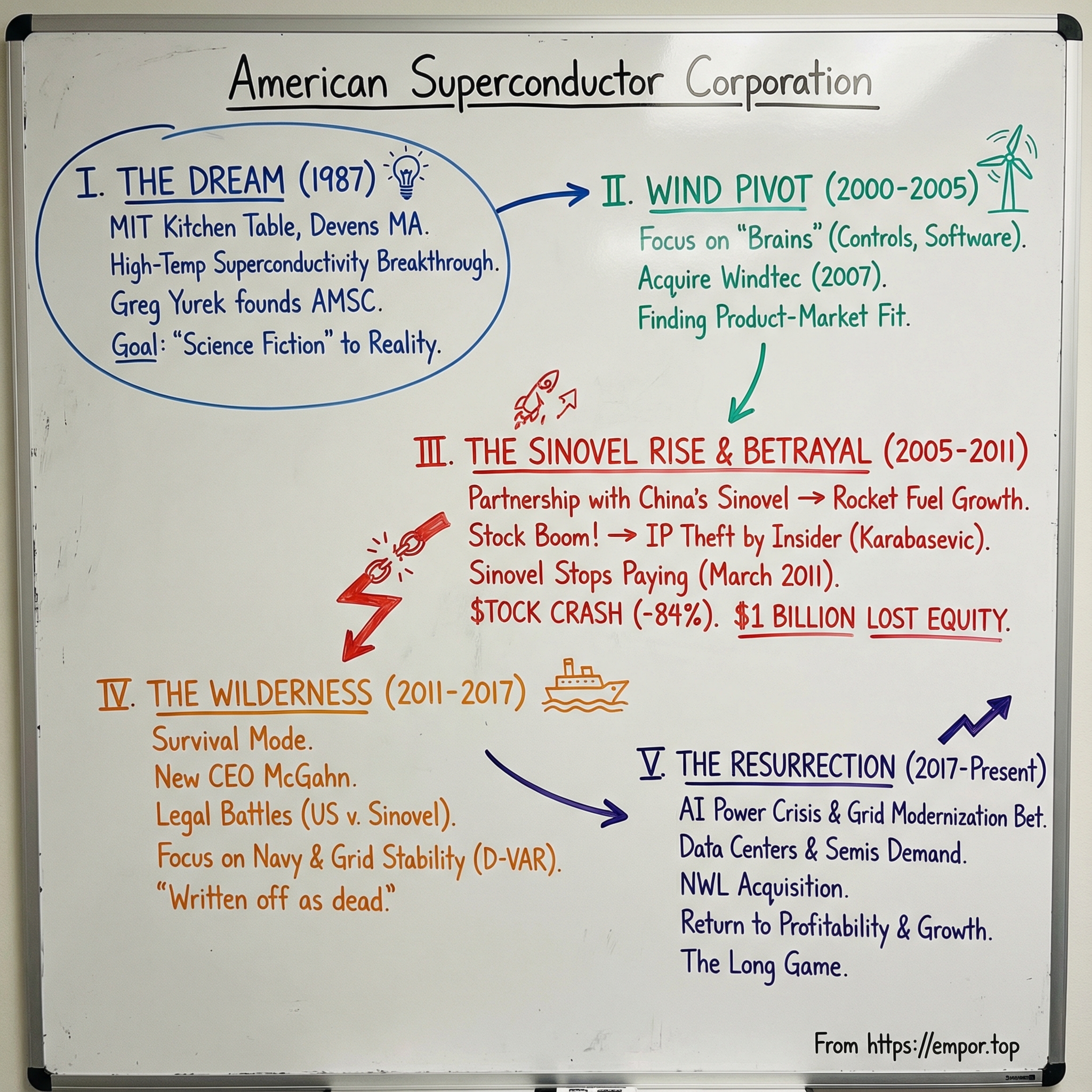

American Superconductor Corp: From High-Temperature Dreams to the Wind Power Betrayal

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture a kitchen table in Devens, Massachusetts, in the spring of 1987. Four MIT professors lean in over coffee, papers spread out, equations and sketches piling up. They’re not talking about a “startup” the way we mean it today. They’re chasing a physics miracle with real-world stakes: superconductivity at temperatures that might actually be usable outside a lab.

American Superconductor was born right there. On April 9, 1987, MIT professor and materials scientist Gregory J. Yurek founded the company in his kitchen.

What followed over the next few decades reads less like a clean business case and more like a thriller: big scientific ambition, a hard pivot into wind energy that suddenly worked, a partnership in China that became the company’s oxygen supply—and then a betrayal that nearly flatlined the whole enterprise.

In early 2011, a Serbian employee at AMSC sold the company’s proprietary wind turbine control software to its biggest customer, China-based Sinovel. Sinovel then stopped paying AMSC. The market reacted instantly. AMSC lost 84% of its market cap.

That’s the hook, and it’s why AMSC is worth studying: how did a company built on a moonshot technology get betrayed by the customer it depended on, lose more than $1 billion in shareholder equity almost overnight, and still survive long enough to matter again?

Because AMSC didn’t just survive. It reoriented around a slower, more grinding opportunity: grid modernization. The thesis that carried them through the wilderness—that the aging electrical grid would eventually need major investment in power quality and resilience—has since become urgent. AI data centers are pushing electricity demand into uncomfortable territory, and AMSC’s grid solutions business has started to accelerate, including 86% year-over-year growth in grid solutions revenue in Q1. The company Wall Street wrote off after the Sinovel disaster has been putting up some of its strongest results in years, helped along by tailwinds from data centers, semiconductor fabs, and defense spending.

So this story is about deep tech dreams colliding with the real world. It’s about what happens when you bet the company on one customer, in a place where IP protection can be more theory than reality. And it’s about the stubborn, unglamorous persistence it takes to keep a subscale infrastructure company alive long enough for the world to finally catch up.

II. The Superconductor Revolution & Founding Vision (1987–2000)

You can’t understand why AMSC existed at all without rewinding to a scientific jolt that hit the world in the mid-1980s.

Superconductivity had been known since 1911, and it was mesmerizing in theory: cool a material below a critical temperature and electrical current can flow with no resistance. In practice, that “critical temperature” was so close to absolute zero that superconductors lived in the realm of expensive cryogenics and academic demos, not power lines and factories.

Then, in 1986, IBM researchers J. Georg Bednorz and K. Alex Müller found superconductivity in a copper-oxide ceramic at dramatically higher temperatures than anyone thought possible. It didn’t just move the goalposts—it redrew the whole field. Their work set off a frenzy of replication and improvement, including later advances that pushed critical temperatures high enough to make a crucial coolant practical: liquid nitrogen. Compared to liquid helium, nitrogen was abundant, cheap, and far easier to handle.

The excitement was so intense that the Nobel committee effectively sprinted. Bednorz and Müller received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1987—one of the shortest gaps ever between discovery and Stockholm. The message to the world was clear: this wasn’t a niche curiosity anymore. This was a potential platform technology.

Gregory J. Yurek was in exactly the right place at exactly the right time. A materials scientist on the MIT faculty, he’d been working on metals and ceramics processing—work that helped lead to methods for manufacturing high-temperature superconductor (HTS) wire. On April 9, 1987, he founded American Superconductor in Devens, Massachusetts, along with fellow MIT professors including Yet-Ming Chiang and David A. Rudman. Chiang would later go on to found multiple standout materials companies, but in 1987 he was right there with Yurek, making the same bet: if superconductors could be made manufacturable, they could change the world.

And the pitch basically sold itself. Lossless power transmission—electricity moving from generator to city with dramatically reduced losses. Compact, ultra-powerful motors and generators. Next-level magnets for MRI machines and particle accelerators. Even magnetic levitation for trains. Venture capital was captivated by the idea that physics had just handed industry a cheat code.

AMSC moved quickly. The company went public in 1991, and over time it raised more than $600 million across venture capital, corporate partnerships, government contracts, and public markets to fund a very specific kind of grind: turning lab-grade materials into something you could manufacture, ship, and maintain.

That grind proved brutal.

Making superconducting wire that performs reliably is hard. Making it at commercial scale—consistently, affordably, and with yields that don’t destroy your gross margins—is the kind of problem that eats decades. Through the 1990s, AMSC built patents, prototypes, and early HTS power-device efforts, but broad commercial adoption stayed out of reach. The cryogenics were still non-trivial, the materials were finicky, and utilities don’t exactly rush to adopt exotic new infrastructure.

So AMSC leaned into the classic deep-tech survival strategy: keep the dream alive with credibility and cash from the U.S. government while you fight the manufacturing battle. Department of Defense work helped do both.

At the same time, the company looked for real-world deployments that proved HTS could do something useful on an actual grid. In July 2000, AMSC activated six Distributed Superconducting Magnetic Energy Storage (D-SMES) units on the Wisconsin Public Service transmission grid, designed to mitigate instability and increase power transfer capability across a 200 MW-rated system. Around that period, the message became: this isn’t just science fair stuff—it runs.

But even with working deployments, the “lab to market” chasm remained. Costs stayed high. The market was theoretically enormous, but painfully slow to adopt. AMSC could see the promised land, but it couldn’t yet build a profitable highway to get there.

By the turn of the millennium, the company needed a bridge—a nearer-term business where its power expertise could translate into revenue while the pure superconductor vision matured. That bridge would turn out to be wind energy, and once AMSC stepped onto it, the journey ahead would be far more dramatic than anyone at that kitchen table in 1987 could have imagined.

III. The Wind Power Pivot: Finding Product-Market Fit (2000–2005)

By the early 2000s, AMSC’s leadership was staring at an uncomfortable truth. The superconductor wire business was real science, real engineering—and still not a real engine for a public company. High-temperature superconductors might change the world someday. But AMSC needed something that could pay the bills before “someday” arrived.

Wind power fit the bill.

Not because wind was simple, but because it was complicated in exactly the right way. A modern wind turbine doesn’t just spin and spit out electricity. Wind speed changes constantly, which means the turbine’s output is messy—variable frequency, variable voltage. To turn that into clean, grid-ready power, you need sophisticated power electronics and tight control software. That was AMSC’s home turf.

AMSC had already been selling electrical systems and key components like its PowerModule power converters into wind for years. One customer, Windtec in Austria, was integrating AMSC’s technology into the turbines it designed. Meanwhile, the broader environment was finally tilting in wind’s favor. U.S. states were adopting Renewable Portfolio Standards that forced more renewables into utility portfolios. Europe was further ahead, with policies like Germany’s feed-in tariffs fueling a surge in projects. The industry was expanding—and the part of the turbine stack that mattered most for grid compatibility was exactly where AMSC could differentiate.

Alongside wind, AMSC was also building relationships that reinforced its credibility in grid-adjacent hardware. Partners included Southern California Edison, Siemens, Nexans, and Los Alamos National Laboratory, working toward mitigating fault currents in high-voltage systems to prevent equipment damage during surges. It wasn’t the same as shipping superconducting wire at scale—but it was real work with real customers, and it kept AMSC anchored in the power world.

Out of this period came a strategic reframing that would define the company’s next act: the turbine’s “brains” are more valuable than its “bones.” Blades, towers, and gearboxes are heavy manufacturing. Controls and power conversion are where the intellectual property lives—and where performance and reliability get won or lost. AMSC leaned hard into that layer.

That’s also when the company began developing D-VAR (Dynamic VAR) systems for grid stabilization. These systems detect voltage disturbances and respond instantly by dynamically injecting leading or lagging reactive power into the grid—technology that mattered both for connecting wind farms and for improving broader grid reliability.

But the move that truly set AMSC up for its next phase didn’t land until later. In 2007, after seeing orders from Windtec licensees begin to rise, AMSC acquired Windtec and renamed it AMSC Windtec GmbH, according to Jason Fredette, the company’s director of investor and media relations.

The purchase price was 1.3 million shares of AMSC common stock, valued for accounting purposes at approximately $13.1 million, based on a five-day average stock price of $10.08 per share at the time AMSC signed definitive documents on November 28, 2006.

Windtec, based in Klagenfurt, Austria, brought something AMSC urgently needed: full wind turbine design capability. Windtec designed turbine systems from the ground up and licensed those designs to third parties for an upfront fee plus royalties on each installation of a Windtec-designed turbine.

“This acquisition opens an important chapter in American Superconductor’s history, positioning our company for strong additional sales in one of the most exciting growth sectors in energy today,” said Greg Yurek, AMSC’s CEO and founder.

Windtec’s founder, Gerald Hehenberger—a 20-year wind industry veteran—stayed on as Vice President and Managing Director. The deal also included earn-out provisions tied to revenue growth targets through fiscal year 2011. At the time, that sounded like a prudent incentive structure. In hindsight, it reads like dramatic irony.

With Windtec in the fold, AMSC could offer something much closer to a turnkey package for would-be turbine makers: licensed turbine designs, electrical control systems, power electronics, and engineering services. And instead of trying to outmuscle incumbents like Vestas or GE, AMSC could become the arms dealer for new entrants—especially in markets where local manufacturing was politically and economically desirable.

One market, more than any other, fit that description.

China.

IV. The Sinovel Partnership: Spectacular Rise (2005–2011)

The partnership that would define—and nearly destroy—American Superconductor began in 2005, not long after Sinovel itself was founded. AMSC Windtec and Sinovel teamed up that year, and AMSC began supplying core electrical components for Sinovel’s 1.5 MW turbines. As Sinovel pushed into bigger machines, AMSC’s role expanded too, providing engineering support and power electronics for the 3 MW and 5 MW turbines the two companies co-developed.

To see why this relationship got so big, so fast, you have to understand Sinovel—and the man behind it. Sinovel was founded by Han Junliang, who would later become China’s first wind power billionaire after Sinovel’s IPO in 2011. At the start, the company was backed with 100 million yuan in initial capital provided by Dalian Heavy Mechanical & Electrical Equipment Engineering, a Chinese state-owned company.

Han had the instincts—and the political read—to catch China’s clean-energy wave early. In 2004, he saw where policy and money were headed and launched Sinovel on a playbook that had already worked for other Chinese industrial champions: adopt foreign-developed technology, scale manufacturing aggressively, and ride domestic demand. He also made a crucial strategic call ahead of rivals, moving straight into building larger 1.5 MW turbines years before key competitors were forced to follow.

And demand did what Han hoped it would do: it exploded.

By 2009, China had become the world’s largest wind market. A third of global wind additions were happening there. The country more than doubled its wind generation capacity from 2008 to 2009, rising from 12.1 GW to 25.1 GW, according to the Global Wind Energy Council. Industry researcher MAKE Consulting expected China to reach roughly 130,000 MW of grid-connected wind power by the end of 2015.

Sinovel wasn’t trying to be a strong domestic player. It was trying to be the global leader. By 2010 it ranked third among wind turbine manufacturers worldwide. The company benefited from its partial state ownership, access to major government contracts, and Han’s connections—all as China pushed to reduce air pollution and ease its dependence on coal-fired power.

For AMSC, this was rocket fuel. The Sinovel relationship reshaped the company’s trajectory: AMSC built a factory in China, established a design center in Europe, and added hundreds of jobs both in China and in the United States.

Sinovel made no secret of the ambition. “Since its founding in 2004, Sinovel has proven to be China’s dominant wind turbine manufacturer while also quickly rising in the global rankings,” Han said. “Our next objective is to become the largest wind turbine manufacturer in the world.”

In May 2010, at the American Wind Energy Association conference, the partnership widened again. Sinovel and AMSC’s wholly owned AMSC Windtec subsidiary agreed to design and jointly develop a lineup of advanced, multi-megawatt-scale turbines that Sinovel planned to market worldwide. Sinovel expected volume production by the end of 2012—and as part of the deal, it would continue buying core electrical components from AMSC for these new machines.

The stock market loved the story. AMSC’s shares ran from single digits to over $40 by 2010, briefly touching $60 in early 2011. It looked like a clean, modern version of globalization: American IP and engineering paired with Chinese scale, together accelerating the energy transition.

But the trap was already closing.

In retrospect, the warning signs weren’t subtle. Customer concentration became extreme. Sinovel represented more than 70% of AMSC’s revenue—over 75% by some accounts. This wasn’t a “big customer” risk. It was a single point of failure, tied to a partner operating in a jurisdiction where IP protection could be uncertain at best.

That vulnerability was compounded by the structure of doing business in China. Foreign companies faced restrictions that could leave them exposed to technology transfer. In AMSC’s case, 70% of every Chinese wind turbine had to be manufactured on Chinese soil—one reason AMSC opened a factory in China and hitched itself so tightly to Sinovel. McGahn says American Superconductor understood the risk.

And the relationship had a fundamental asymmetry that would matter when things turned: AMSC needed Sinovel to survive its wind pivot. Sinovel, led by Han, was already thinking about a future where it didn’t need AMSC at all.

V. The Betrayal: March 2011 & The Espionage Scheme

In March 2011, the Sinovel machine suddenly went from rocket fuel to wrecking ball. McGahn says Sinovel already owed AMSC roughly $70 million for a shipment it had received. Then it refused to pay. Worse, it refused a second shipment that was ready to leave.

The market understood what that meant before AMSC did. AMSC’s stock was cut in half almost overnight, vaporizing nearly a billion dollars in shareholder equity.

The date employees still point to is March 31, 2011—the day the company’s world changed. Sinovel abruptly stopped accepting major shipments, blowing up multiple contracts in one move.

At first, AMSC’s leadership didn’t have a clean explanation. Sinovel told the market it was simply trying to reduce inventory. Investors didn’t buy it. Shares plunged about 45% after AMSC warned results would be lower than expected because its largest customer—China’s biggest wind turbine manufacturer—was refusing shipments. The overreliance everyone had hand-waved during the boom was now the whole story.

Then the real story surfaced.

In June 2011, AMSC discovered that Sinovel had gained access to, and was actively using, stolen AMSC trade secrets and intellectual property. The source was an insider: Dejan Karabasevic, an AMSC employee. Karabasevic later confessed and was imprisoned in Austria.

Karabasevic was a Serbian engineer working at AMSC Windtec in Klagenfurt, Austria. He was seen as an up-and-comer, and he spent about 70% of his time in China, out on wind turbines, living and working alongside Sinovel employees.

Then he hit a career snag. After being demoted into customer service, his ego took the hit—and Sinovel executives noticed. Karabasevic complained openly, even to two Sinovel colleagues, Su Liying and Zhao Haichun, both senior executives. They saw an opening. If they could turn him, they could get what they really wanted: AMSC’s proprietary control software.

He fit the classic insider-threat pattern. Coworkers described him as money-hungry, angry, and narcissistic. Sinovel sold him a new narrative: that helping them wasn’t betrayal, it was opportunity—money, status, a new life in China.

The theft itself was deliberate. According to charges later filed, the defendants stole the PM3000 source code on March 7, 2011, moving it by downloading from an AMSC computer in Wisconsin to a computer in Klagenfurt.

Karabasevic pulled pieces from different places to assemble the full system. Some of the code sat on servers in Austria. Another critical portion was in Wisconsin. He downloaded both, stitched them together, and delivered the complete package Sinovel needed.

Sinovel didn’t offer him a token payment. For his work, prosecutors said Sinovel and Karabasevic agreed to a six-year, $1.7 million contract starting in May 2011, along with a Beijing apartment and funds sent to Karabasevic’s girlfriend.

And the mindset behind it was blunt. Han reportedly told an AMSC executive that software was “like cabbage”—basically worthless, so why not just take it? That belief—that software IP wasn’t “real” property in the way physical equipment was—ran through the entire scheme.

The timeline is telling. In early March 2011, Sinovel stopped accepting AMSC products. On March 10, 2011, Karabasevic submitted his resignation. AMSC accepted it on March 11.

AMSC’s engineers didn’t have to look long to find proof of what was happening. In June 2011, while servicing turbines in China, they discovered Sinovel was running a version of AMSC’s LVRT software that AMSC had never sold or licensed to Sinovel.

AMSC had anticipated the risk. It built protections into the product: encryption to prevent unauthorized use, and a separate code that allowed only a two-week trial before the LVRT software stopped functioning.

“We then found a version of the software in Sinovel’s installations in China in June that we had never sold to the firm,” a Windtec programmer said, according to a court transcript.

Once AMSC understood what it was looking at, the investigation moved fast. In the following weeks, AMSC investigated Karabasevic’s activity—at times using a private investigative firm—and uncovered extensive email and Skype communications with Sinovel employees. The messages laid out the arrangement: Karabasevic would download the software, deliver it, and, when necessary, modify or repair it so it would keep working inside Sinovel’s turbines.

Austrian authorities moved quickly too. Karabasevic was convicted on September 23 for fraudulent data handling and distribution of trade secrets. He received a 12-month jail sentence, two years of probation, and was fined 200,000 euros in damages.

And the alleged motive was as enormous as the betrayal. Sinovel had been buying equipment and software from AMSC for turbines it manufactured, sold, and serviced. According to the indictment, by March 2011 Sinovel owed AMSC more than $100 million for products and services already delivered, and it had contracts to purchase more than $700 million more in the future. The government alleged that Sinovel’s goal in stealing AMSC’s copyrighted information and trade secrets was to keep building and retrofitting turbines with LVRT capability without paying AMSC—cheating AMSC out of more than $800 million.

“Wall Street had written us off as dead,” McGahn says.

VI. The Wilderness Years: Survival & Reinvention (2011–2017)

The collapse wasn’t a bad quarter. It was an amputation.

Evidence later presented at trial captured the scale of the damage: after the theft and Sinovel’s refusal to pay, AMSC lost more than $1 billion in shareholder equity and nearly 700 jobs—more than half of its global workforce.

And then, right as the crisis snapped into focus, the company changed captains.

Daniel McGahn was promoted to CEO effective June 1, 2011, succeeding founder Gregory J. Yurek, who retired after more than two decades running the company. It was a brutal handoff: McGahn didn’t inherit a growth story. He inherited an emergency.

His résumé made the irony almost too perfect. McGahn had joined AMSC in 2006 in strategic planning and corporate development, then rose to become Senior Vice President of Asian Operations, where he helped establish AMSC’s operations in China, Korea, and India. Now the executive who’d helped build AMSC’s Asia footprint had to navigate the catastrophic failure of the company’s biggest China relationship—and rebuild AMSC so it could never happen again.

The fight with Sinovel turned into a multi-front, years-long slog. In September 2011, AMSC filed four legal actions in China accusing Sinovel of illegally using AMSC’s intellectual property and seeking more than $1 billion in deliveries and damages. AMSC also asked Chinese police to pursue criminal action against Sinovel and certain employees. But as AMSC would later note, nearly two years after those filings, Chinese police had not undertaken an investigation and China’s civil courts had not begun substantive hearings.

In the U.S., the machinery moved faster. On June 27, 2013, a grand jury in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Wisconsin charged Sinovel, two of its senior executives—Su Liying and Zhao Haichun—and former AMSC engineer Dejan Karabasevic. The allegations weren’t ambiguous: conspiracy to steal and theft of trade secrets, criminal copyright infringement, wire fraud.

The FBI even went looking for the stolen software where it was being used: inside Sinovel turbines. Based on the investigation, agents obtained a warrant to search wind turbines Sinovel had installed in Massachusetts. In searches conducted in March 2012, May 2012, and December 2012, the FBI found AMSC’s pirated software inside Sinovel-manufactured turbines.

But lawsuits don’t make payroll. While the legal process ground forward, McGahn had to keep the company alive in the present tense. The playbook was simple and punishing: cut costs hard, preserve cash, diversify away from China and any single customer, and lean into the parts of AMSC that could still win—Grid products and U.S. defense work.

The Navy relationships became oxygen. AMSC won a contract worth up to $8.4 million from the Naval Surface Warfare Center for engineering and technical services, support it said would help the Navy insert AMSC’s HTS technology into ship protection systems and further develop HTS-based power delivery systems.

One of those systems was degaussing: reducing a ship’s magnetic signature so undersea mines are less likely to detect it. AMSC said its ship protection system could reduce the weight of the degaussing system by 90% and cut energy consumption by roughly half versus legacy systems—exactly the kind of performance claim that matters when you’re trying to earn the right to exist inside a Navy platform.

On the grid side, AMSC’s D-VAR voltage regulation business wasn’t flashy, but it was real. The company pointed to D-VAR and Static VAR Compensator (SVC) systems helping utilities deal with stability and reliability issues on transmission networks, and said it had emerged as the world’s leading provider of STATCOM devices.

It took years, but the criminal case finally reached a turning point. In early 2018, the United States v. Sinovel case went to trial in Madison, Wisconsin. On January 24, 2018, a jury returned a guilty verdict on all counts after an 11-day trial and about three hours of deliberation, convicting Sinovel of conspiracy to commit trade secret theft, theft of trade secrets, and wire fraud.

“Sinovel nearly destroyed an American company by stealing its intellectual property,” said Acting Assistant Attorney General Cronan.

At sentencing, Judge Peterson found that AMSC’s losses from the theft exceeded $550 million. He imposed the maximum statutory fine of $1.5 million on Sinovel and sentenced the company to a year of probation. During that probation, Sinovel was required to pay the unpaid balance it had agreed to pay AMSC under a settlement agreement.

That settlement totaled $57.5 million. By July 6, 2018, Sinovel had paid $32.5 million, with one year to pay the remaining $25 million.

“We’re happy to close this chapter,” McGahn said.

It was vindication, but not restoration. The conviction mattered symbolically, yet the dollars were a fraction of what AMSC had lost, and the executives who allegedly orchestrated the theft remained outside U.S. reach. Justice arrived years late, and it didn’t come close to making AMSC whole.

What it did do was buy something else: an ending. AMSC could stop living inside the Sinovel story and start writing a new one.

And crucially, the company was still standing. McGahn’s thesis through the darkest stretch—that the U.S. grid would eventually have to be modernized, and that AMSC’s power-quality and resilience technologies would find their moment—wasn’t wrong. It was just early.

That moment was getting closer.

VII. The Grid Modernization Bet (2017–2021)

After Sinovel, AMSC’s worldview narrowed and hardened. No more living or dying on one customer. No more betting the company on a market where contracts might not mean much. The next chapter was built around a quieter conviction: the U.S. electric grid was aging, overloaded, and headed for a reckoning.

The logic was straightforward. As wind and solar scaled, the grid would have to deal with power that didn’t behave like a traditional coal or gas plant—more variable, more intermittent, and harder to manage in real time. As extreme weather events became more frequent and more damaging, utilities would have to spend on resilience, not just capacity. And as transportation and buildings began electrifying, demand would climb, pushing already-stressed networks closer to their limits.

At the same time, Distributed Energy Resources—especially solar PV—started showing up everywhere: rooftop systems, commercial installations, and smaller utility-scale projects scattered across distribution networks that were never designed for two-way power flow. Renewables are dynamic by nature, which meant distribution grids now had to get smarter fast—able to absorb and balance these new resources while still delivering reliable, high-quality power to customers.

This was the environment AMSC had been waiting for. It leaned into the unglamorous but essential world of power quality and control, positioning its products as the tools utilities would need to integrate more renewables without breaking the grid. At DistribuTECH, the industry’s big North American transmission and distribution event, AMSC announced a new solution for utility customers: D-VAR VVO, designed to mitigate power quality issues on the distribution grid as solar penetration rises, and to support conservation voltage reduction management.

Meanwhile, the Navy business kept doing what it had done in the wilderness years: provide steadier ground. AMSC announced a delivery contract with Huntington Ingalls Industries, through its Ingalls Shipbuilding division, for a high temperature superconductor-based ship protection system to be deployed on LPD-32, a San Antonio-class amphibious transport dock ship. It was the fifth ship protection system AMSC had secured for the San Antonio-class platform—slow, methodical validation that this technology belonged on real ships, not just in presentations.

And yet, for all the progress, AMSC still couldn’t escape the reality of its scale. Revenue stayed stuck in roughly the same band year after year, and profitability remained frustratingly out of reach. The grid modernization thesis looked right—but markets don’t pay you for being right early. They pay you when urgency shows up, and that urgency still hadn’t arrived at full force.

Inside the company, the story they told themselves was still the long arc: taking something that used to live in science fiction and turning it into commercial infrastructure.

“We are taking a technology that, for decades, was from the pages of science fiction, and developing, and launching, commercial products, creating a marketplace, securing new customers, and growing a business. If you read any science fiction story about space travel, the propulsion systems of that ship is a superconductor, which is what we make.”

Then COVID hit in 2020. Supply chains snarled, projects slipped, timelines got pushed. But the underlying bet didn’t change. If anything, the pandemic poured fuel on digitalization—and digitalization ultimately means more electricity demand. The pause also gave AMSC time to keep strengthening its portfolio and deepening customer relationships.

What nobody saw coming was how quickly a completely different force—artificial intelligence—was about to turn “eventually” into “right now.”

VIII. The AI Power Crisis & Resurrection (2021–Present)

Then the urgency finally showed up—and it came from a place almost nobody associated with an old superconductors-and-wind company.

The AI boom turned electricity into a front-page constraint. Training large language models, running hyperscale data centers, and expanding semiconductor manufacturing all require enormous, highly reliable power. Suddenly, the grid wasn’t just “aging.” It was in the critical path of the modern economy.

By 2025, that shift was visible in AMSC’s own momentum. Its shares were up more than 120% year-to-date, not on a single narrative spike, but on a clearer story: the clean energy transition is stressing the grid, AI is pouring gasoline on demand, and utilities, chip fabs, and defense customers are spending to keep power stable.

AMSC’s strategy in this period was straightforward: take the power electronics, controls, and grid-integration expertise it had spent decades accumulating and aim it at faster-growing, more diversified markets—data centers, semiconductor plants, and expanded defense power systems.

In August 2024, AMSC made a deal that fit that plan. The company acquired NWL, Inc., a privately held New Jersey company that supplies power systems to industrial and military customers. At closing, AMSC paid $25 million in cash and issued 1,297,600 restricted shares of AMSC common stock valued at approximately $31.4 million, and it also agreed to an additional $5 million cash payment subject to various adjustments. AMSC positioned the acquisition as a way to accelerate profitable growth, broaden its product offerings, and expand its reach.

NWL brought profitable scale. The business had a three-year average of about $55 million in annual revenue, with operating margins approaching the teens, selling power supplies and power controls into industrial and military applications.

Defense, meanwhile, kept expanding—this time beyond the U.S. Navy. AMSC announced a multi-year, multi-unit delivery contract valued at approximately $75 million with Irving Shipbuilding in Halifax for Ship Protection Systems hardware, plus engineering support for the Royal Canadian Navy. The scope was also expected to include integration and commissioning.

The financials started to reflect a company that wasn’t just surviving anymore.

For fiscal 2024, AMSC reported revenue up 53% to $222.8 million, including Q4 revenue of $66.7 million, up 60% year-over-year. It also posted net income of $6.0 million for the year—an improvement of $17.1 million versus the prior year’s loss. The company highlighted $75 million in new orders and total year-end orders of nearly $320 million. Q4 operating cash flow was $6.3 million, and cash and equivalents ended the year at $85.4 million.

Fiscal 2025 began even stronger. First-quarter revenue came in at $72.4 million versus $40.3 million in the same quarter the year before, driven by both organic growth and the NWL acquisition. Net income for the quarter was $6.7 million, or $0.17 per share, compared to a net loss of $2.5 million, or $0.07 per share, in the prior-year period.

“We’ve kicked off fiscal 2025 with accelerated growth, delivering a standout first quarter marked by significant progress and exceptional execution that surpassed our expectations,” said CEO Daniel P. McGahn. “AMSC grew fiscal first quarter revenue by 80% year-over-year, generated net income of over $6 million marking our fourth consecutive quarter of profitability, and achieved expanded gross margins surpassing 30%. Strength in the semiconductor market—driven by growing demand for applications such as artificial intelligence and data centers—contributed to our momentum.”

By this point, Grid had become the center of gravity: the Grid business unit accounted for 83% of total revenue, with year-over-year growth of 86% in Q1 2025.

AMSC also changed how it sold. Instead of treating its offerings as a menu of separate products, it began packaging the full portfolio into integrated solutions—aiming for bigger orders and deeper entrenchment. Management put it bluntly: “we’re not cross-selling anymore. We’re just selling. We’re selling the whole portfolio to everybody.” That approach showed up most clearly in the semiconductor market, where customers increasingly want complete, engineered power solutions—not a pile of components.

And the market noticed. As of August 25, 2025, AMSC’s market cap was $2.24 billion. A company that traded under $3 per share after the Sinovel catastrophe was back above $30—still far below its 2011 peak above $60, but no longer defined by the wreckage of 2011.

IX. Playbook: Deep Tech, Geopolitics, & Resilience Lessons

AMSC’s story isn’t just dramatic. It’s useful. It’s a compact playbook on what it takes to drag deep tech out of the lab, what can go wrong when geopolitics enters the chat, and what “survival” actually looks like when a company gets punched in the mouth.

On Deep Tech Commercialization:

The jump from “science project” to “business” is where most deep-tech dreams go to die. AMSC’s superconductor work really was revolutionary—and just as importantly, it was brutally hard to commercialize at attractive margins. The company stayed alive by finding beachhead markets where its core strengths still mattered: wind turbine electronics, grid stabilization tools, and Navy ship protection work. Those weren’t the original moonshot. They were the bridge that kept the lights on.

"AMSC, over its history, has been a company with a lot of promise because its technology is so compelling. The challenge I inherited was to turn that compelling technology, first developed in the late 1980s, into something commercially viable."

And the infrastructure world doesn’t reward speed. It rewards stamina. Capital needs are high, sales cycles are long, and adoption is slow. AMSC has been public since 1991—decades of living in the gap between “this could change everything” and “yes, but will anyone buy it this year?”

On Geopolitical Risk:

The Sinovel betrayal became a reference case for a reason. It wasn’t just a corporate dispute—it was a vivid example of what happens when intellectual property meets a market where enforcement is uncertain and incentives to localize technology are strong. AMSC’s experience showed up in broader policy debates about IP protection and U.S.-China trade because it put a human and financial cost on what can otherwise sound abstract.

The most basic operational lesson is also the harshest: customer concentration is dangerous anywhere, and it becomes existential when that concentration sits inside a jurisdiction where you may not be able to enforce your contracts. AMSC knew the risks—McGahn says American Superconductor was aware of the risk.—but the growth was so fast, and the opportunity looked so huge, that the company rode it anyway.

The takeaway isn’t “never enter markets like that.” It’s to assume that contracts don’t matter if you can’t enforce them, and to diversify before you’re forced to. If you don’t, then survival depends on whether you can absorb the blow when industrial policy or nationalism overrides commercial agreements.

On Corporate Survival:

AMSC’s near-death stretch is a real-time lesson in crisis management: cut costs fast and deep, preserve cash, protect the core capabilities that still differentiate you, and focus only on the markets where you can win.

After the theft, the impact was staggering: more than $1 billion in shareholder equity erased, and nearly 700 jobs gone—over half the workforce. The cuts weren’t elegant. They were necessary.

The legal fight offers its own lesson. Litigation is slow, expensive, and emotionally draining—and even “winning” can feel like losing. The $57.5 million settlement was a fraction of the damage. But the conviction did something money couldn’t: it validated AMSC’s claims, put real consequences on the record, and gave employees something they hadn’t had for years—closure.

On Market Timing:

AMSC’s grid modernization thesis was right, but early—by about a decade. Renewables added complexity, but not always urgency. AI changed that. Data centers and semiconductor fabs turned electricity into a hard constraint, and suddenly the grid wasn’t a background topic; it was the bottleneck.

This isn’t just a speculative moment. It’s the collision of three forces: the clean energy transition, AI-driven demand growth, and the unavoidable need to upgrade aging infrastructure.

The companies that benefit from shocks like this are rarely the ones that show up at the last minute. They’re the ones that positioned themselves in advance—and then managed to survive the lean years without running out of cash, credibility, or willpower.

X. Analysis: Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers

Porter's 5 Forces Analysis:

Threat of New Entrants: MEDIUM-HIGH

This is not an easy business to stroll into. You need real engineering depth, credibility with utilities and defense customers, and the ability to build and support mission-critical hardware in the field. That creates real barriers.

But if this market keeps getting bigger—and if AI-driven power demand keeps turning “nice-to-have” grid upgrades into “do-it-now” spending—then the usual suspects can absolutely show up. ABB, Siemens, and GE Vernova already have the relationships, the manufacturing muscle, and the balance sheets. AMSC’s Navy certifications and long customer history offer some insulation, but not immunity.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW-MEDIUM

Most of AMSC’s components can be sourced from multiple vendors, which keeps suppliers from having too much leverage. The exception is any truly specialized material or subsystem—especially anything tied to superconducting applications—where options narrow and dependencies creep in.

AMSC has also pushed further into integration, and the NWL acquisition helped here. The more of the stack you control, the less you’re at the mercy of any one supplier.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: HIGH

This is the structural pressure point.

Utilities are disciplined buyers. They’re technical, they’re conservative, they’re price-sensitive, and they move on long planning cycles. Even when they want what you sell, they often can’t buy it quickly.

The Navy is a different flavor of the same problem: a hugely valuable customer with high switching costs, but one that can become a concentration risk if it grows too dominant in the mix.

And then there are hyperscalers. They have enormous negotiating power, and they know it. The twist, right now, is that they’re also under extreme pressure to secure power and interconnection. That urgency can temporarily shift leverage toward vendors who can deliver fast—one of the few windows where a smaller specialist like AMSC can punch above its weight.

Threat of Substitutes: MEDIUM

There are other ways to solve pieces of the grid-stability and power-quality problem. Batteries, traditional capacitor banks, and other FACTS approaches can all compete, depending on the use case. For data centers, “substitute” can even mean changing the plan: build somewhere else, bring generation on-site, or redesign the power architecture.

AMSC’s edge isn’t that it’s the only answer. It’s that, in certain scenarios, it’s the fastest answer—and speed is increasingly the product.

Competitive Rivalry: MEDIUM-HIGH

AMSC lives in a competitive neighborhood full of giants. It’s a specialist, often going up against companies with deeper benches, broader product lines, and global scale.

AMSC does have pockets of differentiation—specific configurations and applications where its know-how matters, including Navy degaussing and certain STATCOM deployments. And the market may be expanding fast enough to support multiple winners in the near term. Still, the risk is obvious: if incumbents decide this is a priority, they can invest, bundle, underprice, and squeeze.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Assessment:

-

Scale Economies: WEAK — AMSC is still subscale relative to the industrial heavyweights. NWL helps, but it doesn’t flip the fundamental dynamic.

-

Network Economics: NOT APPLICABLE — This is infrastructure hardware, not a network-effect business.

-

Counter-Positioning: MODERATE — AMSC can move faster into emerging needs, especially around data center grid solutions, while incumbents protect legacy lines. The downside: if the opportunity becomes big enough, incumbents can copy and catch up.

-

Switching Costs: MODERATE-STRONG — Once you’re installed in critical infrastructure, you’re hard to rip out. Certifications, integration work, and operational familiarity all create stickiness—especially in Navy programs and utility environments.

-

Branding: WEAK — This isn’t a consumer brand, and even in B2B, the Sinovel era left scar tissue. Credibility has been rebuilt slowly, mostly through execution and longevity, not marketing.

-

Cornered Resource: MODERATE — There’s real IP here in superconducting applications and power electronics. Patents and trade secrets matter, even if the Sinovel episode proved they’re not a force field. Separately, security clearances and long-standing Navy relationships are hard-earned assets that competitors can’t replicate overnight.

-

Process Power: MODERATE — Decades of shipping, integrating, and supporting grid-facing systems creates institutional muscle memory. It’s an advantage, but not an unassailable one if a better-capitalized competitor commits to learning the same lessons.

Overall Assessment:

AMSC’s “moat” is real, but it’s not the kind that lets you relax. It’s moderate, built from switching costs, specialized know-how, and hard-to-earn relationships—especially with the Navy.

The flip side is just as real: high buyer power and a persistent scale disadvantage. In this next chapter, AMSC’s outcome hinges on execution and timing—specifically, whether the AI-driven power crunch keeps customer urgency high enough that speed and specialization beat waiting for the incumbents.

XI. Bull vs. Bear Case

The Bull Case:

The AI data center buildout is real, urgent, and enormous—measured in the hundreds of billions. At the same time, grid infrastructure investment has rare bipartisan backing, boosted by the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. That’s the setup for AMSC’s best version of itself: a specialist with proven power-quality and grid-integration solutions that can be deployed faster than many alternatives.

The early signs are there. AMSC booked $75 million in new orders and finished the year with nearly $320 million in total orders, giving the business real forward visibility—something it often lacked in past eras.

Defense is the stabilizer. The Navy and ship protection work provides a steadier, higher-margin baseline while the company leans into faster-growing grid opportunities. And critically, it’s no longer just a U.S.-only story. “This contract award marks the first AMSC Ship Protection production systems delivery to an allied navy. This contract represents the success of the very deliberate actions we have taken to diversify our business, drive growth and expand scale both domestically and internationally.”

The other bull argument is simpler: focus. After years of fighting for survival, management is operating with clearer priorities. If revenue keeps scaling, operating leverage could finally show up in a meaningful way, and AMSC could become an attractive acquisition target for a larger industrial player that wants proven technology and customer relationships without waiting years to build them.

The Bear Case:

The scars are real. AMSC has a long history of execution issues and false starts, and it’s still small next to ABB, Siemens, and GE Vernova. If the big players decide this niche matters, they have the manufacturing scale, balance sheets, and customer access to squeeze a smaller competitor hard.

Customer concentration is also a lingering structural risk. It isn’t Sinovel anymore, but the Navy and a handful of major grid contracts can still make the revenue base feel lumpy and exposed.

Profitability, while improving, is still a relatively recent development—and this is a capital-intensive business. If growth accelerates, AMSC may need additional funding, and that could mean dilution. And there’s always the narrative risk: the “AI power crisis” could cool off, get solved in ways that bypass AMSC’s sweet spot, or simply shift budgets toward different solutions. Finally, investors have heard big promises from AMSC before. Recent execution is stronger, but history makes skepticism rational.

Key Metrics to Watch:

Three KPIs matter most for tracking AMSC’s trajectory:

-

Order Backlog and Book-to-Bill Ratio: This tells you whether AMSC is replenishing demand as it ships. A book-to-bill ratio consistently above 1.0 signals momentum; below 1.0 is a warning.

-

Gross Margin Trajectory: Gross margin reached 34% in Q1 2025, up from 30% in the prior-year quarter. If margins keep pushing toward the mid-30s to 40% range, it supports the operating leverage story. If they stall, it may point to pricing pressure or mix problems.

-

Customer Diversification: Watch revenue concentration by customer and segment. The fastest way for this story to break again is to recreate a single-customer dependency under a new name.

XII. Epilogue & Current Developments

By fiscal 2024, AMSC was putting up numbers that would’ve sounded impossible back in the post-Sinovel triage years. Revenue reached $222.8 million, up from $145.6 million in fiscal 2023. The jump came from higher D-VAR and NEPSI revenue, plus the added contribution from the NWL acquisition. The bigger headline, though, was the bottom line: AMSC reported net income of $6.0 million, or $0.16 per share, versus a net loss of $11.1 million, or $0.37 per share, the year before.

This is the part of the movie where the survivor starts to look like a growth story again—but with an asterisk. The comeback appears real, but it’s not yet proven durable. Revenue has climbed dramatically from the post-betrayal lows. Profitability, which stayed out of reach for more than a decade, has now held for multiple consecutive quarters. And the balance sheet is no longer a constant source of dread.

A key ingredient in that stability has been fresh capital. AMSC raised $124.6 million in equity, lifting cash and equivalents to $213.4 million, up from $85.4 million as of March 31, 2025.

The broader environment is helping, too. Tailwinds are turning into sustained demand: Department of Energy funding for grid modernization is moving from press release to project. State renewable mandates are forcing utilities to invest in equipment that keeps voltage and stability within spec. And outside the utility world, corporate load growth—especially from data centers and reshored manufacturing—is creating a whole new class of customers who suddenly care a lot about power quality and interconnection timelines. The competitive landscape is getting busier as the opportunity gets more obvious, which cuts both ways: more pressure from larger incumbents, but also more potential partners.

AMSC isn’t standing still on the product side either. The roadmap pushes beyond what got them here—next-generation power electronics, deeper software integration, and AI-enhanced tools to optimize how the grid behaves under stress. And the original superconductor DNA still matters. It remains particularly relevant in Navy applications, and it still holds long-term promise for future transmission and power-delivery projects as the grid’s constraints tighten.

The Counterfactual:

It’s hard not to ask the question: what if Sinovel hadn’t betrayed them?

AMSC was on a path toward more than $500 million in annual revenue, with the kind of margins you can get when your customer is scaling like crazy and you own critical IP in the stack. The early-2011 share price above $60 implied a market cap approaching $3 billion.

Maybe AMSC would have become the default supplier of wind turbine electrical systems at global scale. Maybe the China dependency would have only deepened—turning what was catastrophic in 2011 into something even worse later. Maybe a larger industrial player would have acquired the company before any of that happened.

Instead, the betrayal forced a decade of restructuring that—painfully—built a different kind of company. Today’s AMSC is less dependent on any one customer, geography, or single technology bet than the pre-2011 version. Whether the suffering was “worth it” isn’t something you can calculate. But it did produce a business that looks more resilient, and arguably better aligned with the needs of this moment.

Final Reflection:

AMSC’s story works as both a warning and a reminder of what endurance looks like in deep tech.

For founders, the lessons are blunt. Customer concentration is dangerous anywhere; it becomes existential when you can’t reliably enforce IP rights. Deep tech commercialization demands patience measured in decades, not quarters. And the gap between technological promise and commercial reality is where most ventures get buried.

For investors, AMSC is a live case study in how messy turnarounds really are. Timing matters—AMSC’s grid modernization thesis was right for years before AI, renewables mandates, and industrial load growth made it urgent. And management evaluation requires holding two truths at once: McGahn led the company through survival and into renewed growth, but he also came up inside the era that allowed China concentration to become so extreme.

"I've spent my career at AMSC trying to take dreams and turn them into reality. We are taking a technology that, for decades, was from the pages of science fiction, and developing, and launching, commercial products, creating a marketplace, securing new customers, and growing a business."

The story isn’t over. AMSC still faces real execution risk and increasingly serious competition, even as the demand environment improves. But the company that started at a kitchen table in 1987, rode the superconductor hype cycle, found product-market fit in wind, got betrayed, nearly died, and rebuilt itself—still exists. It’s still betting that its tools matter for the electrical infrastructure that powers modern life.

That original dream—superconductors and advanced power electronics reshaping how the world generates, moves, and manages electricity—hasn’t fully arrived. But it also hasn’t been abandoned. And in an era when electricity is becoming the defining constraint of growth, that dream may finally be getting its moment.

XIII. Further Reading & Resources

Key Primary Sources: - DOJ press release: US v. Sinovel (2018) — the official record of the criminal case - AMSC 10-K filings (2010, 2012, 2024) — how the story looks before the boom, during the crash, and in the comeback - FBI documentary "Made in Beijing" — first-person accounts from investigators - Earnings call transcripts (2011–present) — how management explained the pivots, the litigation, and the long grind back

Contextual Resources: - IEEE Spectrum reporting on the commercialization of superconductors - IEA World Energy Outlook — why grid investment is becoming unavoidable - Recent AMSC investor presentations — how the company frames its strategy today

Relevant Books: - "The Innovator's Dilemma" — Clayton Christensen (deep tech commercialization and why adoption is rarely linear) - "Powerhouse" — Steve LeVine (the broader fight to modernize electricity) - "AI Superpowers" — Kai-Fu Lee (China’s tech strategy and the geopolitical layer underneath stories like Sinovel)

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music