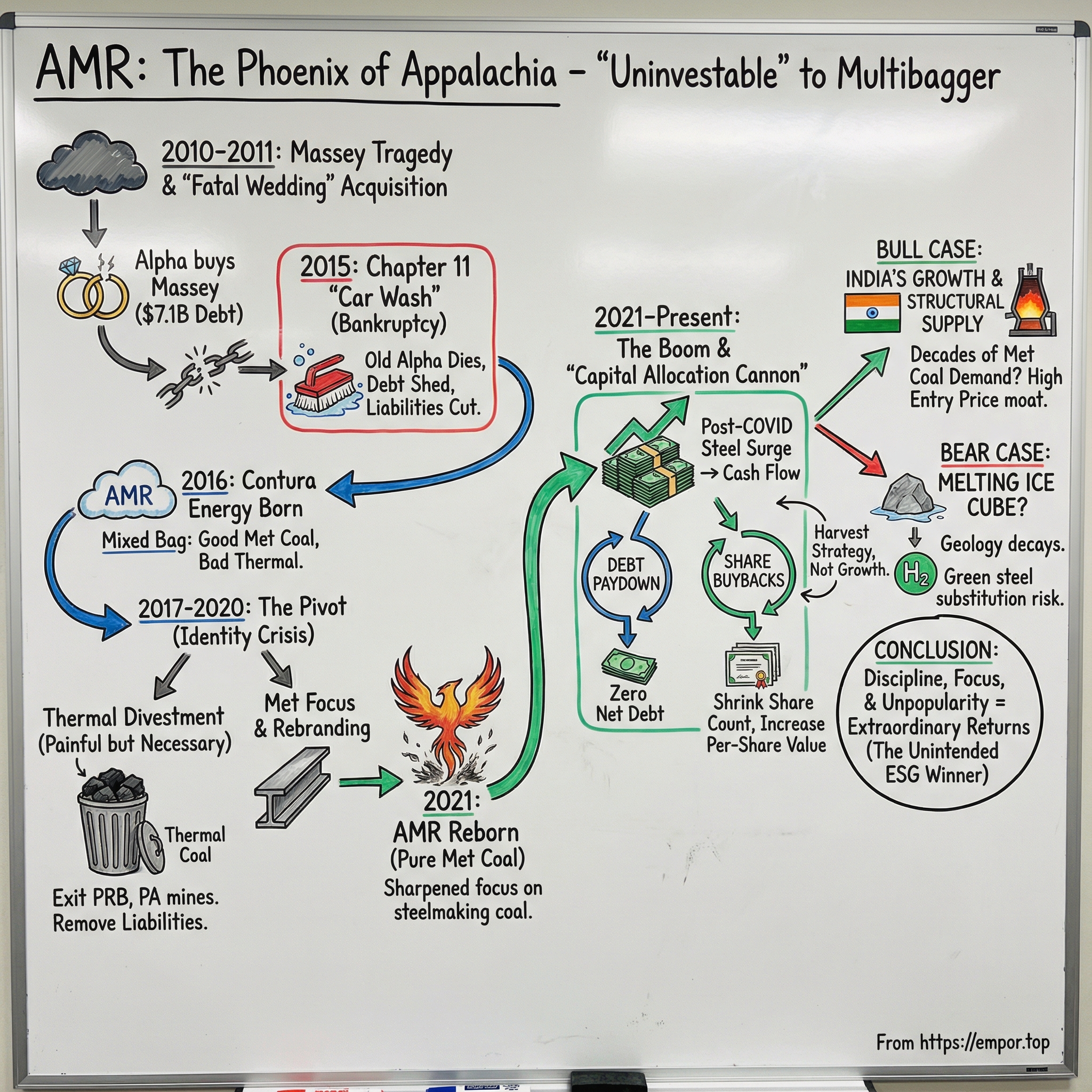

Alpha Metallurgical Resources: The Phoenix of Appalachia

I. Introduction: The "Uninvestable" Multibagger

In the bleak early months of 2021, as markets obsessed over meme stocks, SPACs, and the next software unicorn, an entirely different kind of breakout was quietly getting started in one of the most hated zip codes in American finance.

A coal company—yes, a coal company—was about to put up one of the most shocking stock runs of the decade.

AMR returned roughly 437% in 2021. It followed that with about 150% in 2022. At points in the early 2020s, this supposedly “uninvestable” name managed to beat the S&P 500, the Nasdaq, and even Nvidia. Over a short, surreal stretch, it was up about 2,679%.

This is the story of Alpha Metallurgical Resources: a company that came out of what was then the largest bankruptcy in coal-sector history and turned into a case study in capital allocation discipline, terminal value investing, and the unintended financial consequences of ESG divestment.

But to understand how any of this makes sense, you have to get one thing straight from the start. This isn’t a story about the kind of coal that keeps the lights on. Alpha Metallurgical Resources is a Tennessee-based miner that produces and sells metallurgical coal for steelmaking—alongside a much smaller amount of thermal coal—through underground and surface operations in Central Appalachia. The key product here is metallurgical coal, or “met” coal: the ingredient that helps make steel possible at scale. No steel, no bridges. No skyscrapers. No wind turbines. No electric vehicle chassis. The irony is hard to miss: a huge chunk of the physical “green” future still depends on the very material the green movement most wants to erase.

As one of the largest U.S. producers of met coal, AMR sits in a crucial link of the global steel supply chain. Metallurgical coal is turned into coke and used in blast furnaces—the route that still produces roughly 70% of the world’s steel. It acts as both the chemical reductant and the carbon source that transforms iron ore into steel. However much the world wants to change that someday, this is how steel gets made today.

The investing thesis that emerges is almost embarrassingly simple: when new supply becomes impossible—blocked by regulation, starved of capital, or choked by stigma—the companies already standing become disproportionately powerful. AMR became, in effect, a cash machine in an industry nobody wanted to touch.

And what follows is the path that got them there: from a disastrous acquisition and the shadow of a mining tragedy, through a Chapter 11 “car wash,” and into a modern-era masterclass in buybacks and balance-sheet discipline. It’s a story of specialization beating diversification, of discipline beating growth—and of how being hated by Wall Street can sometimes turn into the greatest competitive advantage of all.

II. Context: The King of Coal & The Massey Shadow

The Appalachian Mountains—running from northern Alabama all the way up toward southern New York—hold one of the great geological endowments in American history. Coal seams that helped power the Industrial Revolution. Coal that fed the country’s factories, railroads, and cities for generations.

But within that vast spine of rock, one pocket matters more than almost any other for this story: Central Appalachia. West Virginia, eastern Kentucky, and southwestern Virginia. Steep ridges. Narrow hollows. And coal with chemistry that steelmakers care about.

This is not the “burn it to make electricity” kind of coal people picture when they hear the word. Central Appalachian metallurgical coal is prized because it’s high-quality bituminous coal with low sulfur and the right coking characteristics—meaning it can be turned into coke and used in blast furnaces. In other words, it behaves less like a generic commodity and more like a specialty input: the carbon content, ash levels, and other properties have to be right, or the steel process breaks down.

That uniqueness is why Central Appalachia has long punched above its weight in U.S. met coal. You can mine coal in plenty of places. You can’t easily replace this particular stuff.

And if you want to understand how Alpha Metallurgical Resources came to exist, you have to understand the ghost that still hangs over these mountains: Massey Energy—and its polarizing leader, Don Blankenship.

Blankenship was coal country’s defiance personified. He rose out of poverty in the West Virginia coalfields and climbed all the way to chairman and CEO of Massey Energy. By the late 2000s, Massey was one of the biggest coal producers in the country. It was also notorious for constant warfare with safety regulators—and a safety record that drew intense scrutiny.

Then came April 5, 2010.

At 3:27 p.m. local time, an explosion tore through the Upper Big Branch South Mine near Montcoal, about 30 miles south of Charleston. The mine was operated by Performance Coal Company, a Massey subsidiary. Twenty-nine miners were killed. It was the worst U.S. mining disaster since 1970.

Investigations that followed were brutal. Federal regulators later concluded that the explosion was tied to methane and coal dust, and that failures in ventilation and other safety systems played a central role. The Mine Safety and Health Administration issued hundreds of citations and assessed major penalties. The disaster wasn’t just a tragedy—it became a public indictment of how Massey ran its operations.

Blankenship resigned in December 2010. Years later, in 2015, he was convicted of a misdemeanor for conspiring to willfully violate safety standards and served a one-year prison sentence. He was found not guilty of securities fraud and making false statements.

But here’s what made the next act possible: even after Upper Big Branch, Massey still sat on enormous reserves of exactly the kind of high-quality coal the world wanted—especially the met coal that goes into steel.

And in 2010, the coal industry was still riding what felt like a permanent boom. A supercycle. China’s growth was insatiable, steel demand looked unstoppable, and prices were ripping. Against that backdrop, Massey became a takeover target: wounded and controversial, yes—but asset-rich.

That combination set the stage for what would become one of the most ill-timed acquisitions in modern American industry.

In June 2011, Alpha Natural Resources—based nearby in Virginia—bought Massey.

III. The Fatal Wedding: Alpha Buys Massey (2011)

In January 2011—still under the shadow of Upper Big Branch—Alpha Natural Resources made its move. It agreed to buy Massey Energy in a deal valued at $7.1 billion. The transaction closed in June, and overnight the combined company became one of the biggest coal miners in the country by market value.

The pitch was scale. The merged company would be a leading U.S. producer of metallurgical coal and would control massive coal reserves—about 5.1 billion tons. Alpha lined up $3.3 billion of financing for the takeover from Citigroup and JPMorgan Chase. Management framed it as a global move, too: a way to become the world’s number-three producer of metallurgical coal, behind BHP and Teck.

On paper, it was easy to see the appeal. Massey, battered by the tragedy and the headlines, looked like distressed inventory. Alpha could buy the assets, fold them into its footprint, and take costs out. The company estimated that integrating operations would cut about $150 million in operating costs. And it wasn’t small. After the merger, Alpha controlled roughly 150 mines and 40 preparation plants—up dramatically from the 65 mines it had at the end of 2007.

But the deal didn’t just come with reserves and rail links. It came with baggage.

That same year, Alpha settled Upper Big Branch-related liabilities with the U.S. Attorney for $209 million, including $41.5 million for survivors and families. Separately, the Mine Safety and Health Administration assessed a $10.8 million fine tied to 369 citations and orders—the largest fine for a mine accident in U.S. history.

And the environmental tab wasn’t theoretical, either. In 2014, Alpha settled Clean Water Act violations with the EPA and state agencies. The agreement included a $27.5 million civil penalty—split across federal, West Virginia, and Kentucky authorities—and roughly $200 million in infrastructure upgrades aimed at reducing toxic discharges into Appalachian waterways.

Then came the part nobody underwrote into the model.

While Alpha was stitching together its new coal empire, the shale gas revolution went from “interesting” to existential. Fracking unlocked enormous supplies, natural gas prices fell, and power generators began switching away from thermal coal. The market Alpha had built its scale around started shrinking.

Alpha’s financial results deteriorated fast. It posted four straight years of losses, laid off thousands of workers, and shut down mine after mine, leaving only about 50 operating. In September 2012, it announced plans to idle eight mines and lay off 800 employees. By July 2015, its stock price was so low it was delisted from the NYSE. And on August 3, 2015—carrying roughly $3 billion of debt, much of it tied to the Massey acquisition—it filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy.

In hindsight, the Massey deal reads like a clean example of the winner’s curse: the buyer who wins because they’re the most optimistic… and therefore pays as if the good times will last forever. Alpha bought at the top of the cycle, financed it with debt, and then watched the economics shift under its feet.

The lesson was brutal. Size and scale don’t save you when the ground truth changes. Alpha built a colossus—and within four years, it was in bankruptcy court.

IV. The Great Reset: Bankruptcy & The Birth of Contura (2015–2016)

The Chapter 11 filing in August 2015 wasn’t a turnaround. It was an ending. “Old Alpha” died in bankruptcy court—and what came next would eventually create enormous value, just not for the shareholders who still owned the stock when the music stopped.

Bankruptcy did what it always does at its most brutal and most effective: it rewrote the company’s obligations. Debt got cut down. Legacy liabilities got renegotiated. The footprint got reshaped. It was less a rescue than a forced reset.

Restructuring people have a cynical nickname for this: the “car wash.” You drive in with years of grime—bad deals, bad timing, and obligations you can’t carry—and you come out the other side cleaner, leaner, and under new ownership.

One example captured the dynamic perfectly. Alpha had relied on more than $1 billion of “self-bonding” to promise it could fund mine reclamation obligations under the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977. In plain English: rather than posting surety bonds, it vouched for itself. But once Alpha was in bankruptcy, that promise wasn’t worth what it used to be. The Wyoming Department of Environmental Quality agreed to accept $61 million instead of the company’s $411 million self-bonding liability to the state. The balance sheet didn’t just get lighter—it got dramatically lighter.

The equity, meanwhile, went to zero. That’s the rule in Chapter 11: shareholders are last in line, and there wasn’t enough left to reach them.

The people who did get something were the creditors—the hedge funds and distressed investors who had been buying Alpha’s bonds for pennies on the dollar. These negotiations were complicated by large funds like Highbridge Capital Management and Davidson Kempner Capital Management, which held pieces of the capital structure and, in some cases, liens on Alpha’s operating cash. They weren’t cheering from the stands. They were playing quarterback.

On July 26, 2016, Alpha emerged from bankruptcy as a privately held company. And out of the wreckage came a new entity: Contura Energy.

Contura began operations that same day, created through the purchase of Alpha assets by a consortium of lenders. The initial package included nine underground mines and four surface mines spread across Virginia, West Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Wyoming’s Powder River Basin. It also came with massive reserves—about 1.4 billion tons—but the mix mattered: roughly 80% of those reserves were thermal coal.

The bankruptcy also reworked the labor side of the business. In March 2016, Alpha petitioned the court to reject collective bargaining agreements with the United Mine Workers of America, seeking to reduce retiree health benefits and modify terms affecting about 610 active miners and roughly 4,800 retirees and dependents. The court approved the rejection, and the parties moved toward negotiated modifications under Section 1113 of the Bankruptcy Code—preserving some benefits, but with concessions designed to make the reorganized business viable. Contura’s workforce, in any case, skewed largely non-union.

Here’s what the new owners believed. Buried inside this messy portfolio were genuinely great assets: high-quality metallurgical coal operations in Central Appalachia. Those mines had always been valuable. What had made them unlivable was everything layered on top—too much debt, too many legacy obligations, and a business mix weighed down by lower-margin thermal coal.

So the lenders took the keys thinking they were buying the good stuff and leaving the bad behind.

But the transformation wasn’t complete—not even close. Contura still owned meaningful thermal coal operations, including in the Powder River Basin out West. And the world was turning against thermal coal with increasing ferocity. ESG screens were spreading. Pension funds were divesting. Banks were refusing to lend.

So even after the “car wash,” Contura faced the question that would define the next chapter:

What kind of coal company could still exist in public markets—and be allowed to win?

V. The Identity Crisis & The Pivot (2017–2020)

The team that took over after bankruptcy quickly realized they had a problem that had nothing to do with geology and everything to do with identity.

Contura was stuck in the middle. Part of the company was exactly what the world still needed: metallurgical coal feeding the steel supply chain. The other part was thermal coal—tied to power generation at the precise moment investors, regulators, and banks were starting to treat “thermal” as a four-letter word.

If Contura wanted to survive in public markets, it had to pick a lane.

That meant a painful divestiture. In December 2017, Contura sold its Powder River Basin operations in Wyoming—the Eagle Butte and Belle Ayr mines—to a little-known buyer, Blackjewel L.L.C. Those two mines had shipped 24.5 million tons through the first three quarters of 2017, and Contura subsidiaries controlled roughly 600 million tons of proven and probable reserves in the PRB.

And yet the economics of the deal told you everything you needed to know about where thermal coal was headed. Contura didn’t walk away with a big check. Instead, it would receive up to $50 million over time through various royalty payments. The real “consideration” was that Blackjewel agreed to assume the permit and reclamation obligations tied to the mines—eliminating about $200 million in undiscounted reclamation liabilities for Contura.

In other words: the reserves weren’t the prize anymore. The escape hatch from long-dated cleanup costs was.

But this move came with a sting in the tail. The company still held the permits to the mines even after selling them, which meant it could still end up exposed if things went wrong. And in 2019, things did go wrong: Blackjewel filed for bankruptcy. The Wyoming mines fell into limbo, and Contura was left navigating a messy legal situation as a prior owner that hadn’t operated the mines since the 2017 sale—but still had its name attached to the permits.

Contura kept going anyway, pushing toward the only version of itself that could plausibly be “investable” again: a met-focused steel supplier.

That’s why, in November 2018, Contura merged with Alpha Natural Resources—reuniting with what remained of “old Alpha”—in a deal expected to make the combined company the largest metallurgical coal supplier in the U.S. Management pitched the logic plainly: more scale in met coal, a stronger balance sheet, greater capabilities, and a longer reserve life.

The last step was to finish the separation from thermal coal. In December 2020, the company sold its thermal operations in Pennsylvania, a deal that largely marked the exit from the thermal coal business. It was a quiet but profound admission: in this environment, some assets were worth more gone than kept—especially once you factored in the value of removing future environmental liabilities and the ability to recognize losses for tax purposes.

Then came the public declaration of what Contura had become.

In early 2021, Contura announced it would change its name—effective February 1—to Alpha Metallurgical Resources, Inc. The reason wasn’t subtle. The new name was meant to reflect the company’s strategic focus on metallurgical coal as a critical feedstock for steel production, and to signal to external stakeholders that the pivot was real.

CEO David Stetson framed it as the culmination of a plan: “Over a year ago, we outlined our vision to make Contura a premier metallurgical coal producer… Bringing back the Alpha name is not only meaningful to us and our history, but it also serves as an outward display to external stakeholders of the sharpened focus we have on metallurgical coal.”

After years of being neither fish nor fowl, the company finally answered the question that had haunted it since bankruptcy.

It wasn’t going to be a fuel supplier to power plants.

It was going to be a pure-play metallurgical coal producer—wired directly into global steel demand. And that distinction would soon matter far more than anyone expected.

VI. The Capital Allocation Cannon (2021–Present)

Then came the boom.

COVID-19 crushed industrial demand at first. But the rebound that followed—helped along by massive stimulus, infrastructure spending, and supply-chain chaos—created exactly the kind of environment met coal producers wait years for. Steel prices surged. Metallurgical coal tightened. And AMR, now leaner, simpler, and far less levered than “Old Alpha” ever was, suddenly started throwing off real cash.

By early 2024, that cash generation was still showing up in the results. In the first quarter alone, AMR reported $868.6 million in revenue and $148.3 million in net income—numbers that would’ve sounded impossible back in the bankruptcy years.

The peak, though, was the 2021–2022 window. Those were the “name your price” years across a lot of the seaborne met market. AMR’s profitability was extraordinary in that period, and while results cooled afterward—as you’d expect in a commodity business—management’s takeaway wasn’t “let’s expand.” It was the opposite: don’t repeat the industry’s oldest mistake.

Because the classic trap for resource companies is to take peak-cycle cash and build peak-cycle projects. New mines, new equipment, new fixed costs—just in time for prices to roll over. Shareholders get diluted by capex. The cycle turns. And suddenly a company that should’ve been harvesting ends up fighting to survive.

AMR chose harvesting.

On March 7, 2022, the company launched a $150 million share repurchase program. Two months later, on May 5, the board increased the authorization by another $450 million, taking the total to $600 million. After that, the pattern became familiar: raise the authorization, keep buying, shrink the float. The authorization reached $1 billion later in 2022, then $1.2 billion in February 2023. Later, AMR announced another $300 million increase, bringing total authorization to $1.5 billion.

The result wasn’t subtle. Since the buyback program began, AMR has returned nearly $940 million to shareholders. By late July, it had repurchased about 5.7 million shares for roughly $850 million—around 27% of its common shares over that span. In one recent quarter alone, it bought back just over one million shares, cutting the share count by 6.7%.

This wasn’t just “returning capital.” It was a deliberate strategy: commit to returning 100% of free cash flow to shareholders, primarily through repurchases, and let the shrinking share count do the compounding.

And buybacks in a small, hated, cyclical company have a special kind of force. Every repurchased share increases the ownership stake of whoever remains. As the float tightens, borrowing shares gets harder and more expensive for shorts. And when earnings come in, they land on fewer shares—pushing up earnings per share and reinforcing the valuation. It’s a feedback loop that can turn a cyclical cash surge into something that looks, from the outside, like a financial magic trick.

Just as important: AMR used the boom to remove the thing that kills commodity companies in downturns—debt.

By 2022, AMR had reduced its term loan by $450 million, with the remaining balance (under $100 million as of May 5, 2022) expected to be eliminated by the end of June 2022. In more recent reporting, the balance sheet still looked unusually conservative for the sector: $268.2 million in cash at the end of the last quarter, and only $10.4 million of debt outstanding.

That’s the holy grail in a cyclical business: entering the next downcycle with virtually no net debt. No interest burden. No covenant tripwires. No desperate refinancing when prices fall. You can just… wait.

This capital-allocation pivot didn’t stay unnoticed. High-profile value investors started paying attention. Mohnish Pabrai, for example, bought AMR and also bought CONSOL Energy (CEIX), while selling 100% of his other U.S.-reported positions in Micron Technology, Brookfield Corp, and Seritage Growth Properties. Whatever else you think of coal, it was a striking signal: the only U.S. holdings he found compelling were two coal producers.

Pabrai’s framing fit cleanly with his “uber cannibal” idea—companies trading at low valuations while aggressively repurchasing stock can create enormous per-share value simply by shrinking the denominator. In AMR’s case, the story was reinforced by management’s posture: no big mine expansions planned, a business meaningfully exposed to exports (nearly 70% of revenue), and buybacks that, across 2022 and 2023, totaled more than $1.06 billion. In 2024, repurchases slowed to $38 million amid softened coal prices and macro caution—but the discipline stayed intact, supported by a meaningful cash buffer.

The company also tightened its leadership structure as it moved from turnaround to “run the machine.” David J. Stetson served as chairman beginning January 2024, after serving as executive chairman since January 2023. He had been CEO and a board member since July 2019, and previously served on Contura Energy’s board from November 2018 through April 2019. His background spanned management, finance, M&A, governance, restructuring, law, and reclamation—basically, a résumé built for making hard calls in hard industries.

Then, in December 2024, Stetson announced his retirement from the board effective December 13. The company stated the departure was not due to any disagreement, and it came after a period in which AMR paid off long-term debt and generated record revenues. During his tenure, he also helped establish the Metallurgical Coal Producers Association, an advocacy organization focused on metallurgical coal and its role in steelmaking.

If you’re tracking AMR from here, the scoreboard is refreshingly simple. Watch realized met coal prices per ton. Watch cost of coal sales per ton. And watch how much cash makes it out the door to shareholders as a percentage of free cash flow. Because for modern AMR, that’s not just a policy.

It’s the product.

VII. The Playbook: Lessons for Builders & Investors

The Alpha Metallurgical story is intensely specific to coal, to Appalachia, and to a particular moment in markets. But the playbook underneath it travels surprisingly well.

The ESG Paradox

Start with the most uncomfortable lesson: when capital leaves an industry all at once, the surviving companies often get stronger.

As banks back away, institutions divest, and lenders decide they don’t want the headline risk, the normal commodity script breaks. The money that usually floods in to build new supply never shows up. Competitors can’t expand. New entrants can’t get funded. And regulators aren’t exactly eager to approve new coal mines anyway.

So the paradox is this: ESG pressure helped cap supply growth and cut competition, which strengthened the strategic position of the incumbents who were already standing. For AMR, it also meant something more mechanical and more powerful—its stock could stay cheap for longer, giving management the chance to retire shares at prices that didn’t reflect the cash the business was generating.

No bank will fund a new coal mine in America. No government will permit it. The result is a de facto moratorium on new supply. For companies with existing permits, established operations, and proven reserves, that starts to look less like “an industry in decline” and more like a cornered resource.

The Singular Focus Strategy

The second lesson is about identity—and the courage to simplify it.

Contura’s decision to divest thermal coal, even when it meant walking away from assets that once would’ve been considered valuable, ended up being the move that unlocked everything that came later. It wasn’t just portfolio cleanup. It was choosing the business the world still had to buy—met coal for steel—and cutting loose the part that the world was actively trying to outlaw, defund, and shame.

Becoming a pure-play metallurgical coal producer made the company easier to understand, easier to underwrite, and easier to run. Management attention narrowed to the highest-return operations. The investor base shifted. And the name change wasn’t marketing—it was a line in the sand. This company wasn’t going to argue about “coal” in the abstract. It was going to sell a critical input to steel.

It also put the scale of the transformation into perspective. The former Alpha Natural Resources had been built through big mergers—Foundation Coal in July 2009, then Massey in January 2011 after Upper Big Branch—and at its peak owned or operated well over a hundred mines. Compare that with about 20 in production today and you can see the strategy clearly: this wasn’t growth. It was deliberate shrinkage into the best part of the business.

Capital Allocation as Product

Which leads to the third lesson: for modern AMR, capital allocation became the product.

Instead of taking peak-cycle cash and pouring it into new projects, the company adopted a harvest strategy—run the existing asset base, generate cash, and return it to owners. Shrink rather than sprawl. It’s the opposite of what mining companies are famous for: levering up in the good years, overbuilding into the peak, and then spending the downcycle cleaning up the mess.

AMR’s approach was simpler and, in a cyclical business, often more rational: don’t chase volume. Chase per-share value.

The Power of Entry Price

Finally, the most timeless lesson in the whole story: entry price is destiny.

The distressed investors who bought Alpha’s debt during bankruptcy didn’t need the coal market to be perfect forever. They just needed it to be survivable—and they needed to buy the claims cheap enough that “survivable” would still produce extraordinary returns. They bought dollar-denominated obligations for pennies, ended up owning the reorganized company, and then watched it generate massive free cash flow in the next upcycle.

The original equity holders got wiped out. The new owners made fortunes. Same assets, same mountains—different line in the capital structure, different price paid. In cyclicals, that’s often the whole game.

VIII. Framework Analysis: Power & Forces

Hamilton's 7 Powers

If you run AMR through Hamilton Helmer’s lens, two advantages jump out. They’re not flashy. They’re structural. And they’re the kind that get stronger when the industry gets less fashionable.

Cornered Resource: Central Appalachia isn’t just “a coal region.” It’s a specific pocket of geology that produces high-quality, low-sulfur metallurgical coal with the right carbon content, ash levels, and coking properties. That chemistry matters. Certain grades of steel require it, and you can’t simply swap it out for generic tons from somewhere else.

The region got hit hard as thermal coal demand collapsed and weaker operators were forced out. But that shakeout also reinforced the point: when supply gets destroyed in a place that holds uniquely useful material, the remaining permitted, operating producers inherit something close to a cornered resource.

Process Power: AMR’s moat isn’t only in the ground—it’s also on the way to the water.

A key piece is Dominion Terminal Associates (DTA) in Newport News, Virginia, a coal shipping and ground storage operation on the U.S. East Coast. DTA is owned by Alpha Metallurgical Resources and Arch Resources. It has annual throughput capacity of 22 million tons and can handle everything from barges up to large ships of 178,000 dwt. Just as importantly, it pairs that scale with high-speed handling plus sophisticated sampling and blending systems—exactly the kind of unglamorous infrastructure that makes a commodity business reliably serve global customers.

As Contura’s CEO Kevin Crutchfield put it at the time, the blending capabilities and transportation flexibility provided by DTA were “a strategic cornerstone” of the company’s Trading & Logistics business—supporting its focus on delivering quality coal products with the service international customers expect. In a market where reliability is currency, that kind of integrated logistics becomes real process power.

Porter's 5 Forces

Threat of New Entrants (Very Low): In the U.S., building a new coal mine is about as close to “not happening” as an industrial project can get. Permitting is punishing, capital is scarce, and the social license is gone. Even if the economics look tempting in a spike year, the practical barriers are enormous.

Threat of Substitutes (Medium to High, Long-Term): The clearest path away from coal-based steel is hydrogen-based direct-reduced ironmaking (DRI) paired with electric arc furnaces (EAF). It’s real, it’s advancing, and steel decarbonization matters for any credible energy transition.

But timelines matter. The shift is measured in decades, not years, because new processes have to solve the steel industry’s core constraints while reaching cost parity with today’s routes. IDTechEx expects hydrogen-based green steel production to reach 46 million tonnes by 2035—meaningful, but still not enough to displace blast furnaces as the dominant production method for the foreseeable future. For AMR, that’s the key tension: long-term substitution risk is genuine, but it’s not an overnight cliff.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: The buyers are steel producers, and while they’re large and sophisticated, their alternatives for high-quality met coal are limited. When the product is specific and the supply is geographically constrained, buyer power has natural limits.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: The big inputs are labor and heavy equipment—think Caterpillar and Komatsu. Those markets can be tight, and mining is never a low-maintenance business. But AMR’s scale helps in procurement and in managing its operating base.

Industry Rivalry: AMR competes with other U.S. met producers like Warrior Met Coal and CONSOL Energy. But rivalry in Appalachia is shaped by the terrain and the geology: mining in the mountains is expensive, and as reserves deplete, production often moves toward thinner seams and tougher conditions. That cost reality makes realized met prices a critical driver of profitability for Appalachian producers—and it’s why AMR’s “harvest and return” strategy matters so much. In a hard-cost region, you don’t win by chasing volume. You win by getting paid for quality and keeping the cash.

IX. Bear vs. Bull: The Future of AMR

The Bear Case: The Melting Ice Cube

The bearish thesis is simple: AMR is a “melting ice cube,” and the buybacks are just the company liquidating itself before the market disappears. In that framing, every repurchased share is less “smart capital allocation” and more “we don’t believe there’s a long future here.”

There’s a real, physical version of that argument, too. Eastern Kentucky is a mature coal region. The easy seams have been mined. Remaining resources are estimated at about 5.5 billion tons, or roughly 48% of original resources. But what’s left is increasingly thin: most of the remaining coal is in seams 28 to 42 inches thick, with only a smaller portion above 42 inches. That matters because thinner seams often mean you have to cut more rock along with the coal—more waste, more processing, higher costs.

This is the unsexy truth of mining: geology deteriorates. Seams thin. Conditions get harder. Costs rise. And at some point, even great prices can’t brute-force bad rock.

Then there’s the demand question. The green steel transition is still years away, but it’s no longer hypothetical. BloombergNEF’s net-zero outlook has most primary steel production by 2050 shifting toward hydrogen-based DRI-EAF, with another meaningful portion using DRI-EAF with carbon capture. The IEA’s revised net-zero roadmap likewise envisions a large share of iron production coming from hydrogen-based processes by 2050. If those scenarios play out, blast furnaces—and the met coal they consume—don’t disappear overnight, but they do shrink over time.

Even the “India will save the day” argument has a ceiling in some forecasts. BloombergNEF expects India’s steel production growth to peak in the 2030s and 2040s, implying the demand acceleration isn’t infinite.

And finally, there’s the skepticism that comes with scars. Not everyone buys AMR’s financial story at face value. Spruce Point, after a forensic financial and accounting review, argued that AMR is masking financial stress in its core mining operations and has used aggressive tax refunds to boost cash flow.

Put all of that together and the bear case reads like this: tougher geology, a long-term technology substitution threat, and a market that could eventually decide steel doesn’t need this input as much as it used to.

The Bull Case: India and the Decades Ahead

The bullish counter-argument centers on one word: India.

India has become the largest buyer of seaborne coking coal, pushed by expanding steel capacity and consumption. The country has set a goal of raising steel capacity to 300 million metric tons per year by 2030, a large jump from 2023 levels.

That growth is especially relevant for AMR because India, unlike China, is still building out basic oxygen furnace capacity—the blast-furnace route that needs metallurgical coal. Provisional data compiled by SteelMint shows India’s met coal consumption rising year over year in 2023, with further increases projected into 2024.

On imports, the forecasts are even louder. An EY Parthenon report produced with the Indian Steel Association projects a sharp rise in coking coal imports by the end of the decade as India targets that 300 million-ton capacity level by 2030, driven by infrastructure, construction, and automotive demand.

The bull case isn’t that the West won’t decarbonize steel. It’s that even if the West does, India is still in its buildout era—roads, bridges, cities—using traditional blast furnace technology. In that world, metallurgical coal demand doesn’t vanish; it persists long enough to matter.

And with supply constrained, that persistence can have outsized effects on price. The optimistic view is basically a structural setup for met coal: limited new mines coming online to replace depletion, continued Asian steel growth, high development costs that require higher prices to justify new projects, and industry rationalization among major producers.

The Valuation Gap

After the stock cooled off over the past year, AMR still trades around a 15% free cash flow yield without assuming unusually high met coal prices. This is also a company with negative net debt and a stated policy of distributing 100% of free cash flow to shareholders.

That low multiple is the market’s way of saying: we don’t trust the duration. Is it a fair discount for a business facing long-term substitution risk and geological degradation? Or is it an opportunity created by a timeline mismatch—where the market is pricing a 2050 problem into a company that may have years of cash generation left?

That’s the bet. And it all comes down to how fast you think steelmaking changes, and how long India’s industrialization wave lasts.

X. Epilogue & Conclusion

From the ashes of Massey and the old Alpha, a leaner, more disciplined, cash-generating machine emerged. The arc—from a $7.1 billion acquisition that nearly broke the company, through Chapter 11, a balance-sheet reset, and finally a hard pivot toward metallurgical coal—reads less like a normal turnaround and more like a corporate reincarnation.

The scoreboard is hard to argue with. Over the run that followed, AMR posted a 2,535.76% total gain and a 92.4% CAGR, massively outpacing peers like ARCH, NRP, and ARLP even after the stock cooled off. In a sector where “value creation” is often just a nice phrase investors use before the next downcycle arrives, AMR made it literal—by shrinking the share count, getting rid of debt, and refusing to light peak-cycle cash on fire.

And the story leaves you with an irony that’s impossible to unsee. The green transition is built out of steel: wind turbines, electric vehicles, solar panel frames, transmission towers, factories, ships. Steel, in today’s world, still mostly comes from blast furnaces. And blast furnaces still need metallurgical coal. The very future meant to move beyond fossil fuels still depends on an input the market has tried to banish.

AMR sits inside that constraint. Its mines and export network feed steelmakers across Europe and Asia, helping keep a critical industrial supply chain functioning for everything from infrastructure and autos—including EVs—to defense applications that require high-strength steel.

More than anything, Alpha’s modern version is a company that recognized what game it was actually playing. It didn’t chase growth at the top of the cycle. It chose discipline. It didn’t try to be everything. It specialized. It didn’t borrow for “optionality.” It paid down debt. It didn’t build for the next boom. It bought back stock and returned capital.

The future is still the future: prices will swing, geology will get tougher, and steelmaking will change over time. But for this chapter of the story, Alpha Metallurgical Resources has been something rare—a champion in a hated industry that quietly generated extraordinary returns while much of the market refused to look.

In the end, it’s a story of discipline beating growth, focus beating diversification, and the strange way being unpopular can become its own kind of moat.

XI. Sources

Key Sources: Mohnish Pabrai’s AMR thesis and 13F filings; Alpha Metallurgical Resources 10-Ks and investor presentations (2016–2024); SEC filings and bankruptcy court documents; International Energy Agency coal market reports; World Steel Association steel demand forecasts; USGS coal resource assessments; and historical reporting from Coal Age, S&P Global Market Intelligence, and other industry publications.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music