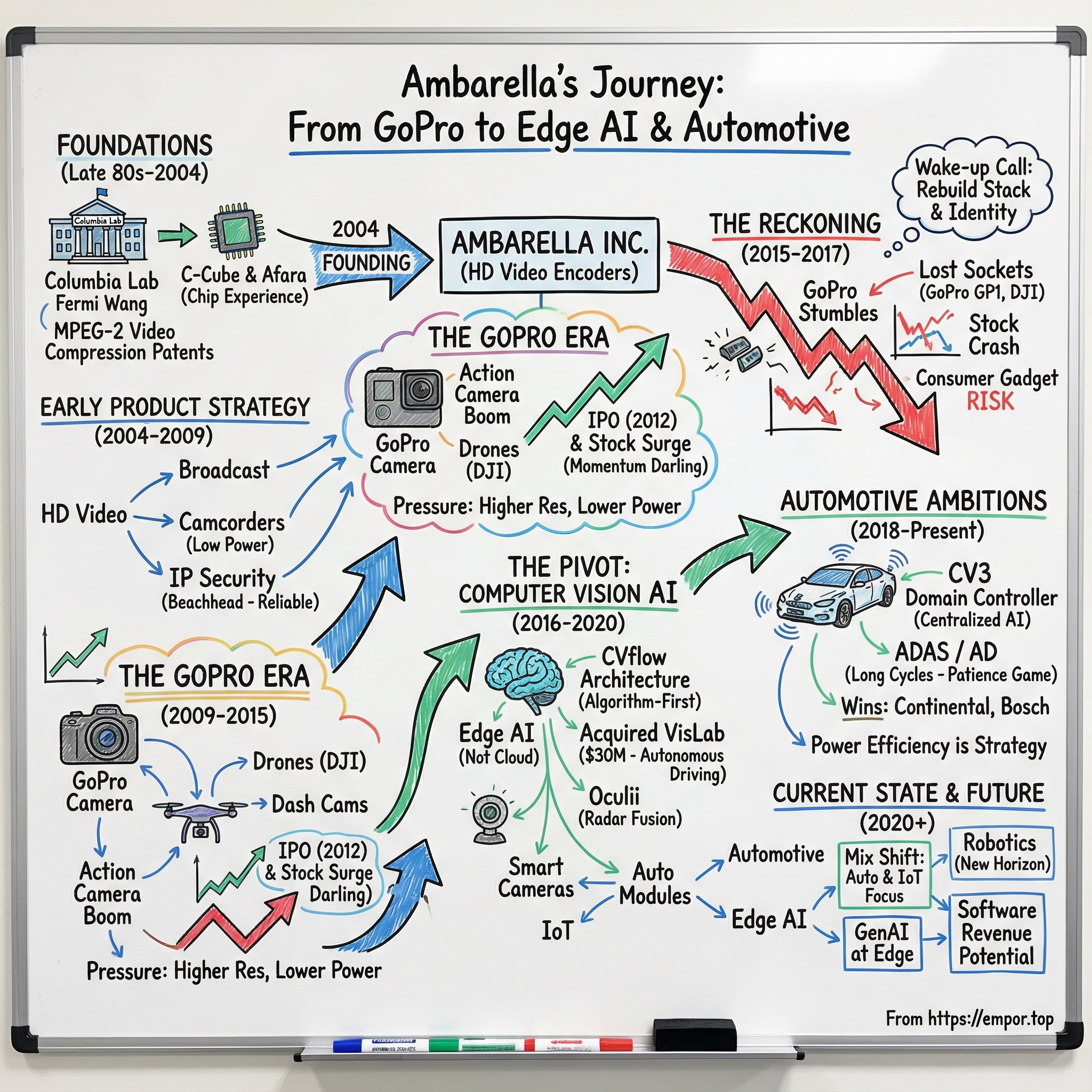

Ambarella Inc.: The Story of Silicon Valley's Computer Vision Pioneer

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture a basement lab in Columbia University’s electrical engineering department in the late 1980s. A young Taiwanese graduate student named Feng-Ming Wang—known to friends as “Fermi,” after the legendary physicist—is hunched over a terminal, working on a problem most of the world hasn’t even noticed yet: how do you compress digital video enough to store it, transmit it, and actually make it useful?

His doctoral work with Professor Dimitris Anastassiou dives into the unglamorous guts of the challenge—discrete cosine transforms, motion estimation, all the math that turns a firehose of pixels into something manageable. At the time, plenty of TV engineers still live in an analog world. But the ideas coming out of that lab would end up feeding directly into MPEG-2—the standard that later powered DVDs, digital television, and, in time, much of the streaming world.

In fact, based on the advances from Anastassiou’s and Wang’s research, Columbia became the only academic institution among nine initial patent holders deemed essential to the MPEG-2 video compression standard. And that early partnership—professor and star PhD student pushing video tech forward before the market knew it needed it—set a pattern that would define Wang’s career: spot the direction video is heading, then build for that future.

Now jump to 2025. The company Wang co-founded in 2004, Ambarella Inc., sits in the middle of a very different kind of race: giving machines the power of sight. Under Wang’s leadership, Ambarella has built a reputation in edge AI and computer vision—energy-efficient system-on-chip designs that combine high-resolution video compression with advanced image and radar processing and deep neural network capability.

Which raises the question at the heart of this story: how does a company that made its name as the chip inside GoPros, drones, and security cameras reinvent itself as an automotive and AI contender?

Ambarella’s journey is a study in pivoting under pressure. It rode the action camera boom to a NASDAQ debut, then nearly capsized when GoPro stumbled. And it survived by betting on a simple, almost inevitable idea: every camera is going to have to become intelligent.

That’s the through-line—computer vision. But getting from consumer gadgets to mission-critical automotive AI meant rebuilding the technology stack, reshaping the customer base, and rewriting the company’s identity along the way. This is the story of how Fermi Wang and his team tried to pull off that transformation—and what it reveals about survival in the brutal, unforgiving semiconductor business.

II. The Semiconductor Landscape & Founding Context (1990s–2004)

To understand why Ambarella existed at all, you have to rewind to the moment cameras stopped being chemical and started being computational.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, Canon, Sony, and the rest of the imaging giants weren’t just shipping new products—they were racing to replace film with silicon. Digital cameras went from quirky gadgets to default consumer electronics in less than a decade. And that shift created a new kind of demand: not for faster PCs, but for tiny, purpose-built chips that could capture light, clean up an image, compress a video stream, and do it all on a battery.

That’s the key point. The hard part wasn’t storing pictures. It was doing the math—fast, in real time, with almost no power.

General-purpose CPUs from Intel and AMD were great at desktop workloads, but they weren’t designed for the specific operations behind video compression and image processing. What the camera world needed were ASICs: chips designed from the ground up to do one job incredibly well.

This was exactly the world Fermi Wang had been living in. After earning his PhD, he joined C-Cube Microsystems, one of the early pioneers in video compression chips. Over the decade that followed, he moved into major leadership roles—by 1997 he was a vice president and general manager—and led efforts across DVD, digital video recorders, and digital video. He launched C-Cube’s MPEG codec business, grew it dramatically, and helped develop what the company described as the world’s first MPEG codec chip.

Wang’s path into that work had always been unusually “end-to-end.” He started at National Taiwan University with a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering, completed military service in Taiwan, then moved to New York City to join his brother and enrolled at Columbia Engineering. Encouraged to keep going, he earned a master’s degree and then a PhD in electrical engineering in 1991 under Professor Dimitris Anastassiou.

And even before the dissertation ink was dry, the work had commercial consequences. In 1990, Wang and Anastassiou filed a patent related to encoding core digital MPEG-2 video. This wasn’t theoretical prestige. MPEG-2 became foundational technology for DVDs and digital television—the kind of standard that quietly ends up everywhere.

Then Wang did something that, at first glance, looks like a detour. In 2000, he co-founded Afara Websystems, a start-up focused on throughput computing for servers. Wang served as CEO until Sun Microsystems acquired Afara in 2002. Afara’s multi-core, multi-thread CPU technology became part of Sun’s UltraSPARC roadmap.

But that exit also left a mark. Wang later described how Afara was sold before he felt ready—board dynamics, outside pressure, the classic “this isn’t the outcome I would’ve chosen on my own timeline.” The lesson he took wasn’t subtle: next time, he wanted to control his destiny.

So in 2004, he started again—this time back in his home territory: video.

In January 2004, Wang teamed up with Les Kohn, a storied chip architect whose résumé included work on Sun’s UltraSPARC, Intel’s i860, and processors at National Semiconductor. Together they founded Ambarella with an initial mission that fit the era: building high-definition H.264 video encoders for the professional broadcast market.

The early team reflected that ambition. They brought in talent like John Ju, who had pioneered MPEG video algorithm development at Sarnoff Research Lab, and Didier LeGall, an MPEG pioneer in his own right. If you were placing a bet on who could make world-class video silicon, it’s hard to assemble a more credible group.

Their thesis was simple and, on paper, obvious: the world was moving from standard definition to high definition, and somebody would need chips that could encode HD video in real time without melting the device or draining the battery. Broadcast—studios, production houses, the professional video pipeline—looked like the cleanest place to start.

Then came the financing—and an early glimpse of how strategically Wang was thinking about the business side.

When Ambarella began talking to venture capital firms, Benchmark was ready to back them, but wanted a second investor in the syndicate. Wang pushed for someone with more than just Silicon Valley credentials—someone who understood Asia deeply, because he knew the supply chain and the markets that mattered for cameras and consumer electronics ran through Taiwan, China, and the broader region.

Benchmark’s response was blunt: there was one person he needed to meet—Lip-Bu Tan.

With early backing from firms like Sequoia Capital and Walden International, Ambarella had what it needed to start building. Wang understood that in semiconductors, being brilliant at the chip is only half the job. The other half is navigating manufacturing, packaging, OEM relationships, and go-to-market realities—much of which lives in Asia.

What Wang and his co-founders couldn’t fully see in 2004 was how quickly broadcast would fade as their center of gravity—and how rapidly consumer devices would become the real prize. And, especially, how one scrappy company building rugged cameras for surfers would end up defining Ambarella’s next chapter.

III. The HD Video Revolution & Early Product Strategy (2004–2009)

Ambarella’s early mission was simple to describe and brutal to execute: HD video was about to spill out of TV studios and into handheld, battery-powered devices, and the chips of the day weren’t ready. Not at the power budgets consumers would tolerate. Not at the prices OEMs needed.

A 1080p stream is millions of pixels per frame, pushed out dozens of times a second. Turning that firehose into a file you can actually store means doing an avalanche of math—discrete cosine transforms, motion estimation, entropy encoding—in real time. And you have to do it inside a tiny thermal envelope. Miss the target and the camera doesn’t just perform poorly; it overheats, chews through the battery, or becomes too expensive to ship.

Ambarella started where it had planned to start: system-on-chip designs for HD broadcast encoders. But the pull of the consumer market came fast. The company moved from broadcast into video processing chips for digital camcorders—and Ambarella’s silicon ended up enabling the first Full HD camcorder. In that world, power wasn’t a nice-to-have. It was the product. A camcorder that captured gorgeous video but died after a few minutes wasn’t a camcorder anyone would buy.

This is where Ambarella’s “secret sauce” took shape. Instead of relying on multiple chips—one for encoding, another for image processing, another for system control—Ambarella integrated the key pieces into a single system-on-chip: video encoding, image signal processing, and the control functions that made the whole device run. That integration mattered. Multi-chip designs were bigger, hotter, and more expensive. A single chip meant less power draw, less board space, and a simpler design for the camera maker—plus a lower bill of materials.

Underneath it all was a classic Silicon Valley semiconductor play: fabless manufacturing. Ambarella would design in the Valley, then have the chips built by foundries in Asia, primarily TSMC in Taiwan. It spared the company the astronomical cost of building its own fabs, but it raised the bar on design and execution. If you don’t own the factory, your advantage has to come from what you put on the silicon.

And the first market that really took wasn’t glamorous at all.

Ambarella’s early beachhead was IP security cameras—the quiet, always-on devices watching storefronts, warehouses, and parking lots. They needed exactly what Ambarella was getting good at: high-quality video compression at low power and a reasonable cost. Even better, the security industry moved on longer product cycles than consumer gadgets, giving Ambarella room to iterate and harden its designs. Over time, security and surveillance became the core driver of the business, with customers including FLIR Systems and major surveillance equipment suppliers like Hikvision. IP security cameras would grow to represent about 45 percent of Ambarella’s business.

It was unsexy, but it was a foundation. Security camera makers weren’t chasing headlines—they wanted reliability, consistency, and parts that would still be supported years later. And because the market was fragmented, Ambarella could scale without being trapped by a single buyer.

Still, the big pop-culture moment—the one that would make Ambarella famous and dangerously dependent—was waiting a few aisles away at the Consumer Electronics Show.

In 2009, at CES, Fermi Wang met GoPro founder Nick Woodman. Wang later said that first meeting kicked off a relationship that would transform both companies—and set Ambarella up for its greatest triumph, and its most precarious risk.

IV. The GoPro Era: Riding the Action Camera Wave (2009–2015)

Nick Woodman’s idea was both ridiculous and inevitable: a camera built for people who didn’t just want to remember an experience, but to relive it from the inside. Surfers, skiers, bikers—anyone moving fast, getting wet, and occasionally crashing. The camcorder industry wasn’t made for that. It was made for birthdays and little-league games.

So GoPro went hunting for a chip that could do something the incumbents weren’t optimized for: capture great-looking video in a tiny, rugged box, on a small battery, without overheating. When Woodman met Fermi Wang at CES in 2009, the fit was immediate. This was exactly the kind of “do a ton of video math under harsh constraints” problem Ambarella had been building for.

The relationship quickly turned into a tight co-development loop. As Wang later put it to CNBC, Ambarella worked closely with GoPro across its camera lineup. GoPro would raise the bar with every product cycle, and Ambarella would have to clear it—again and again.

That’s what made the partnership so powerful, and so dangerous. GoPro’s rise wasn’t incremental; it was a rocket ship. As GoPro grew into a cultural phenomenon, Ambarella quietly became the silicon inside the phenomenon. Hero after Hero shipped with Ambarella chips, and the volumes were unlike anything Ambarella had seen in its early security-camera beachhead.

And GoPro wasn’t asking for small improvements. The spec sheet arms race became the cadence of Ambarella’s engineering roadmap: higher resolution (720p to 1080p to 4K), higher frame rates, better stabilization, lower power. To consumers, it looked like sleek new cameras. To Ambarella, it was relentless pressure to keep delivering more performance per watt, generation after generation.

The win also pulled Ambarella into a broader “camera everywhere” moment. Over those years, its chips showed up across a range of devices: GoPro cameras through the Hero5 era, Dropcam (later Nest), Garmin dash cams, and DJI’s Phantom drones—products that all lived and died on the same promise: sharp video, in real time, in compact hardware.

Wall Street noticed. Ambarella went public in October 2012 at $6 a share, raising about $36 million. The IPO was priced below the expected range—investors weren’t eager to pay up for a small fabless chip company tied to the whims of consumer electronics.

Then GoPro kept winning, and the skepticism evaporated.

By 2014 and into 2015, Ambarella’s stock climbed dramatically as investors connected the dots: Ambarella wasn’t just selling chips; it was effectively powering the action-camera category. The company became a momentum darling, with the market rewarding strong growth and high gross margins.

But the shadow was always there. Customer concentration. When a single company can represent roughly a third of your revenue at peak, you’re not just benefiting from their success—you’re exposed to their failure. Analysts hammered the point. The bear case had a familiar structure: semiconductors commoditize, GoPro is too big a piece of the pie, and the valuation is pricing perfection.

To Ambarella’s credit, management didn’t ignore it. They pushed hard to diversify—more drones, more dash cams, more sports cameras, and deeper penetration in security. The logic was straightforward: enjoy the GoPro tailwind, but build enough other engines so the company could fly without it.

The problem wasn’t the plan. It was the assumption that GoPro’s wave would fade gently.

It didn’t.

V. The Great Reckoning: When GoPro Stumbled (2015–2017)

The cracks started to show in late 2015. GoPro tried to broaden the brand beyond its core with the Session—an ice-cube-shaped camera meant to simplify everything. Instead, it muddied the product lineup and cannibalized higher-margin models. At the same time, smartphone cameras were getting so good, so fast, that more casual buyers started asking an uncomfortable question: why carry a separate camera at all?

Wall Street didn’t wait for the full story to play out. On October 8, 2015, Ambarella’s stock dropped 11% after Morgan Stanley analyst James Facuette warned that GoPro was headed for a rough holiday season. Later that month, Ambarella fell another 11% when GoPro reported weaker-than-expected third-quarter results and offered light guidance—effectively confirming the fear.

Then 2016 turned the slide into a rout. Ambarella started the year by falling hard, down about 40% from the beginning of the year before hitting a new 52-week low in February. Part of that was the broader market’s brutal start to 2016. But the bigger driver was simpler: the wearable camera market was weakening, and Ambarella was chained to it.

And then came the moment that made the risk real, not theoretical.

In September 2017, GoPro launched the Hero 6—and Ambarella’s chips weren’t inside.

GoPro, under margin pressure, wanted cheaper silicon. It also wanted a custom design that wouldn’t be readily available to competitors. So it cut Ambarella out and hired Japanese chipmaker Socionext to build a custom GP1 system-on-chip for the Hero 6.

For Ambarella, it wasn’t just losing a customer. It was losing the customer—the marquee account that had validated its technology and powered its growth. Fermi Wang told EE Times that Ambarella had already seen GoPro-based revenue decline. The year before, it was “10-plus percent,” and he expected it to drop to a “very low number” the next year.

Worse, the exits weren’t isolated. DJI also disclosed that its portable Spark drone didn’t use an Ambarella chipset. Instead, it used Intel Movidius’s Myriad 2 visual processing unit. DJI had previously paired Myriad 2 with Ambarella silicon in the Phantom 4, but in the Spark, Myriad 2 handled both computer vision and image processing.

The stock chart captured the collective mood. From a peak above $120 in July 2015, Ambarella shares sank to under $40 by early 2018. The growth narrative that had once felt inevitable suddenly looked fragile. Analysts who had celebrated Ambarella now wondered out loud whether its niche could be squeezed out by bigger players like Intel and Qualcomm—and whether customers were signaling that stand-alone vision processors and cheaper alternatives could replace Ambarella’s integrated video SoCs.

Inside the company, though, a different story was already unfolding. Management was deep into a pivot that had started before the bottom fell out. The pain didn’t create the strategy—but it forced the company to commit to it.

GoPro was our biggest customer and one day they announced they were going to start building their own chips. That's when we decided we needed to invest in AI and rethink our business.

The consumer-electronics dream was ending. But Fermi Wang and his team were betting that the next chapter of video wouldn’t be about capturing memories—it would be about teaching machines to see.

VI. The Computer Vision AI Pivot (2016–2020)

The insight that would end up rescuing Ambarella sounded almost obvious once you said it out loud: every camera was going to become an AI camera.

For most of the industry’s history, cameras were basically sophisticated recording devices. They captured light, cleaned up the signal, compressed it into video, and saved it for a human to watch later. But in the mid-to-late 2010s, deep learning flipped the job description. Neural networks were starting to recognize faces, spot objects, track motion, and make sense of a scene in real time. Cameras weren’t just capturing reality anymore. They were beginning to interpret it.

Ambarella didn’t just see the AI wave coming; it made a very specific bet about where the compute would live. Not in massive cloud data centers, but at the edge—inside the camera itself. In other words: the same chip that handled video capture and compression would also run the neural networks.

The logic was hard to argue with. Shipping raw video to the cloud to run AI created three big problems. Latency, which becomes a deal-breaker the moment you’re doing anything safety-critical. Privacy, because plenty of customers don’t want their security footage living on someone else’s servers. And bandwidth cost, because streaming HD video around the internet is expensive. If inference could happen locally, you avoided all of it.

Of course, “just run AI on the camera” is easy to say and painful to build. Ambarella’s old strength was video compression and image signal processing. Neural-network inference is a different kind of workload, and getting it to run efficiently—without sacrificing the power profile that made Ambarella attractive in the first place—meant rethinking the architecture.

That re-architecture became CVflow, Ambarella’s proprietary computer vision processing engine. The CVflow line of AI vision SoCs launched in 2017, following intense internal development—and crucially, it also benefited from computer-vision IP Ambarella had brought in through its acquisition of VisLab in 2015.

VisLab was the kind of asset you don’t stumble into by accident. Ambarella acquired VisLab S.r.l., a privately held company in Parma, Italy, for $30 million in cash. The team was founded by Professor Alberto Broggi at the University of Parma, and they’d been working on autonomous driving since the 1990s—years before “self-driving” became a Silicon Valley identity.

Their work wasn’t theoretical. VisLab built a passenger car called ARGO that could perceive the environment with micro cameras, analyze what it saw, plan a path, and drive itself on normal roads. In 1998, ARGO completed a 2000+ km tour in Italy known as Mille Miglia in Automatic, driving more than 94% of the route in automatic mode.

For Ambarella, that was the point. VisLab brought something you don’t build quickly in-house: decades of accumulated know-how in making cameras understand the world. As the thinking went, there wasn’t much overlap between the two teams’ core competencies—which was exactly why the combination worked.

Put the pieces together and you could see the new stack forming. Ambarella contributed world-class video compression and image signal processing, plus the discipline of designing within brutal power constraints. VisLab contributed computer vision algorithms and autonomous-driving expertise. Together, Ambarella could build chips that didn’t just record video—they could extract meaning from it.

That was the promise of the first CVflow generation, CV1. One of the key enablers was simply how much visual information the chip could work with: CV1 supported computer-vision processing up to 4K or 8-megapixel resolution. VisLab’s team pushed deep learning into the architecture, while Ambarella applied its hard-earned expertise in low-power HD and Ultra HD image processing to keep the whole thing efficient.

And the new target list was dramatically bigger than action cameras.

In professional security, AI meant cameras that could count people, recognize faces, and flag suspicious behavior without sending everything to the cloud. In automotive, it meant cameras that could identify pedestrians, read traffic signs, and track lane markings. In body-worn cameras, it meant features like automatically redacting bystanders. In smart doorbells, it meant the ability to tell the difference between family, a delivery worker, and a stranger.

None of this happened in a vacuum. Ambarella was walking into a heavyweight fight. NVIDIA was pushing its DRIVE platform at the high end of automotive AI. Qualcomm was extending its mobile playbook into automotive and IoT. Intel had bought Mobileye, the ADAS powerhouse, and Movidius, whose visual processing units were already popping up in drones and cameras. These companies had budgets and ecosystems Ambarella couldn’t match.

But Ambarella wasn’t trying to win on sheer scale. It had a different angle: power efficiency, and integration. Battery-powered devices don’t care how fast your chip is if it kills the battery. Cars don’t care how impressive your benchmarks are if the system can’t meet thermal limits. And Ambarella’s heritage in video compression meant it could offer a more complete vision pipeline on a single chip—capture, process, compress, and now, infer.

That philosophy showed up in the CV2 family, launched in the late 2010s. These weren’t video chips with AI taped on as an afterthought. They were designed so video processing and neural network inference could share resources efficiently—delivering strong AI capability without blowing the power budget.

By 2020, the pivot had real momentum. The consumer electronics mix that once defined Ambarella—GoPro, action cameras, drones—had shrunk from the center of the company to the margins. Security and automotive were where the growth was heading. And in Ambarella’s labs, the next platform—CV3, the foundation for the company’s automotive ambitions—was already being built.

The open question wasn’t whether automotive was big enough. It was whether Ambarella could survive long enough to get there—before the giants used their scale to squeeze the oxygen out of the market, and before Wall Street ran out of patience waiting for the design wins to turn into production revenue.

VII. Automotive Ambitions: From ADAS to Autonomous Driving (2018–Present)

Automotive is both Ambarella’s biggest shot at a second act and its most consistent source of investor whiplash. The market is massive. The technical requirements line up perfectly with what Ambarella is good at. The company has announced real design wins with real names. And yet the revenue has stayed stubbornly trapped in the future tense.

To understand why, you have to understand how different cars are from consumer electronics. When GoPro picked a chip, you might go from decision to a product on shelves in 12 to 18 months. In automotive, the clock runs on a totally different scale. Programs can take years, and the industry is allergic to surprises.

Even within automotive, the pace varies. Chinese OEMs and Tier 1 suppliers can move faster—often 18 to 24 months to introduce a product—while elsewhere it can take around 48 months. That means a “design win” you hear about today may not turn into meaningful revenue until 2027 or later. If you’re used to consumer cycles, that kind of wait feels like torture.

Then there’s the qualification gauntlet. Automotive silicon has to meet strict functional safety requirements—think ASIL-B through ASIL-D in the ISO 26262 framework. It has to survive temperature swings from -40°C to 125°C. And it has to operate reliably for 15+ years. The certification and validation process alone can take years, even before the first production vehicle ships.

But the payoff is why Ambarella keeps leaning in. Modern vehicles are increasingly camera-heavy: backup, surround view, driver monitoring, cabin monitoring, and the big one—ADAS features like automatic emergency braking and lane keeping. As vehicles move toward L2 and L2+ systems, the sensor count grows, and the compute burden explodes.

This is where Ambarella thinks it has an edge. A single CV3 can, in its configuration, support up to 12 physical or 20 virtual cameras—enough to handle an entire sensor suite. For a typical L2+ deployment, that could mean around 10 cameras, five radar modules, and numerous ultrasonic sensors feeding into one centralized brain.

The CV3 family is Ambarella’s flagship automotive bet. At CES, the company announced the CV3 AI domain controller family: a scalable, power-efficient CVflow line of SoCs aimed squarely at assisted and automated driving. Ambarella positioned CV3 as offering up to 500 eTOPS of AI processing performance—about a 42x increase over its prior automotive family—along with up to 16 Arm Cortex-A78AE CPU cores and up to a 30x boost in CPU performance versus the prior generation. The pitch was clear: centralized, single-chip processing for multi-sensor perception.

In plain English, CV3 is meant to be a generational leap. Where older automotive systems often stitched together multiple chips, CV3 aims to run a full ADAS stack—camera processing, radar fusion, and more—on one piece of silicon. That can mean lower power consumption, less system complexity, and a lower cost structure for automakers and Tier 1s.

And Ambarella has landed wins that matter. At CES 2023, Continental and Ambarella announced a strategic partnership to jointly develop scalable, end-to-end hardware and software solutions based on AI for assisted and automated driving. Around the same period, the conversation centered on CV3 ADAS design wins at Continental and Bosch—two of the top three Tier 1 suppliers of automotive camera sensing and radar sensing systems. There was no exclusivity, but the significance was the validation: CV3 could clear the bar for L2 and L2+ applications.

Continental and Bosch aren’t “nice logos.” They’re among the most influential suppliers in the world. Their adoption signals that Ambarella’s approach—performance paired with efficiency—can compete in a field where the default choices often come from much larger players. As one statement put it, “The strategic partnership between Continental and Ambarella is bringing full-stack vehicle system solutions to the road—beginning with 2027 SOPs—that combine maximum performance and industry-leading energy efficiency.”

That last phrase is the catch: 2027 SOPs. Start of production is where the money starts. Until then, it’s engineering effort, integration work, and long stretches of waiting.

Meanwhile, the competitive landscape is brutal. NVIDIA is deeply entrenched across L2 to L4 systems in Western and Chinese OEM lines, and likely holds 25–35% global share. Mobileye chips are embedded in roughly 27 OEM brands worldwide and, as a camera-centric ADAS leader, likely commands 10–15% market share.

Ambarella’s counter-positioning is simple: power efficiency. The company says its CV3-AD chip family delivers higher performance—processing sensor data faster and more comprehensively for better environmental perception—while reaching up to five times higher power efficiency than other domain controller SoCs.

That matters, especially in EVs. In an electric vehicle, every watt you spend on compute is a watt you don’t spend on range. As EV adoption grows, OEMs have become increasingly sensitive to power draw and thermal budgets. Ambarella’s message lands because it’s not just about peak capability; it’s about delivering the needed capability inside real-world constraints.

Then there’s radar—Ambarella’s other big chess move. The company completed its acquisition of Oculii Corp for $307.5 million, adding adaptive AI software algorithms designed to improve radar perception using current production radar chips. Ambarella says Oculii can enable significantly higher resolution—up to 100X—along with longer range and greater accuracy.

With Oculii, Ambarella could pitch something bigger than “we do cameras well.” It could offer a more complete perception story: camera and radar, fused on a single chip. That aligns with the growing consensus that robust assisted driving and autonomy will require multiple sensor modalities working together, not a single-sensor bet.

Finally, there’s China—an opportunity and a complication in the same breath. Chinese automotive OEMs tend to move faster than European and American counterparts, which could pull CV3 revenue forward relative to slower Western programs. But that speed comes with geopolitical exposure, and investors have become much more sensitive to that risk.

So the question that hangs over Ambarella’s automotive chapter is straightforward: when does it finally show up in the numbers? The design wins are real. The technology is being taken seriously. But turning a win into revenue requires vehicles rolling off production lines with Ambarella silicon inside—and in automotive, that’s a patience game measured in years, not quarters.

VIII. The Drone Crash & Consumer Electronics Lessons (2016–2022)

For a moment, drones looked like Ambarella’s perfect sequel to GoPro. DJI’s Phantom line—flying cameras with gimbals—helped create a whole new consumer category almost overnight. Parrot, Yuneec, and a swarm of challengers rushed in behind them. And for Ambarella, it felt like the same magic formula: high-quality video, brutal power constraints, tight thermal limits, all in a compact device.

Then the drone boom ran the GoPro playbook all the way to the ending.

DJI’s lead widened until it wasn’t really a market anymore—it was one dominant player and everyone else struggling to stay afloat. Price pressure intensified, regulations and uncertainty—especially in the United States—cooled mainstream demand, and the economics got uglier for the rest of the field. Even DJI began moving away from Ambarella in parts of its lineup, exploring alternative silicon and architectures.

The timing was telling. Around the same period that Ambarella was showing off its newly architected CV1 computer vision chip at CES—positioned less as a consumer gadget enabler and more as a foundation for highly automated vehicles—GoPro was announcing plans to exit the drone business, cut 250 jobs, and lower its fourth-quarter revenue estimate. The message was hard to miss: the consumer “camera boom” was no longer the growth engine it had been.

The broader consumer camera market was maturing in ways that punished specialized chip vendors. Smartphone cameras got so good, so quickly, that casual users stopped buying dedicated cameras at all. The remaining action-camera market consolidated around GoPro—now on custom chips—while the spec-driven upgrade cycle started to stall. The race to higher resolution and frame rates hit diminishing returns; for most people, the difference between the latest tiers of 4K and 8K wasn’t compelling enough to drive constant upgrades.

Ambarella came out of that era with a set of lessons that weren’t academic—they were survival logic. Consumer electronics are cyclical and unforgiving. Customer concentration can become an existential threat. And if your main lever is “better specs,” you’re signing up for a treadmill where the next competitor’s chip can erase your advantage in a single product cycle.

Those lessons pushed Ambarella toward markets that behaved differently: professional and enterprise security, automotive, and industrial applications—segments with longer product cycles, higher switching costs, and less commodity-like pricing. In those worlds, reliability and integration matter as much as raw performance.

Smart home and AIoT security cameras became a clear example of the new play. Ambarella built strong relationships with ODMs that customers could leverage during manufacturing, while Ambarella worked directly with customers during the design phase. Companies like Ring (acquired by Amazon), Arlo, and enterprise security vendors weren’t just looking for crisp video—they wanted on-device intelligence: face detection, package detection, and person tracking. That extra complexity tended to translate into higher selling prices and, more importantly, stickier customer relationships.

In the end, the consumer electronics chapter didn’t just fade—it reshaped how Ambarella ran the company. The takeaway was simple and non-negotiable: never again could a single customer or one volatile market segment be allowed to decide Ambarella’s fate. Diversification stopped being a goal and became the operating system.

IX. The AI Edge Computing Revolution & Current State (2020–Present)

By the early 2020s, the world finally caught up to the idea Ambarella had been building toward: cameras weren’t just going to record video. They were going to understand it. And that shift—AI moving from the cloud down into devices—landed right in Ambarella’s sweet spot.

The big push-and-pull is simple. Cloud AI is incredible, but it’s also heavy: huge models, huge compute, huge power draw, and plenty of reasons customers don’t want to stream sensitive video off-device. If you need real-time responses, strong privacy, or you’re operating where bandwidth is expensive or unreliable, you don’t get to “phone home” to a data center. The intelligence has to live at the edge—inside the camera, the robot, the vehicle.

That’s the world Ambarella built CVflow for. And it started showing up in the mix. As the company put it, led by the CV2 product family, edge AI products made up more than 45% of total revenue in fiscal 2023, and were expected to grow to around 60% in fiscal 2024.

Product-wise, the lineup now reads like a map of where edge vision is headed. CV3 is the automotive bet—the domain controller era and multi-sensor perception. CV5S targets AI security cameras and broader IoT. CV7 is aimed at the next wave, including robotics. The through-line across all of them is consistent: more neural-network performance, but without abandoning the constraint that made Ambarella relevant in the first place—power efficiency.

Financially, the last couple years have looked like a company grinding through a transition rather than coasting on a single hit product. Coming out of an inventory correction, Ambarella returned to growth. Revenue in the third quarter of fiscal 2025 was $82.7 million, up from $50.6 million a year earlier. Over the nine months ended October 31, 2024, revenue was $200.9 million, up from $174.9 million over the prior-year period.

More recent quarters showed that momentum continuing. In fiscal Q3, revenue was $108.5 million, above the high end of the company’s $100 to $108 million guidance range, up sequentially and up year over year. Management also raised fiscal year 2026 guidance, projecting growth approaching 40%.

The more important story beneath the topline is the mix shift. IoT—especially security cameras—and automotive have taken center stage. Consumer electronics is no longer the business that gets to decide Ambarella’s fate. That’s exactly what the company wanted after the GoPro era, even if the automotive portion of that mix is still, to a large extent, future tense.

Margins have held up in the way you’d expect from a differentiated, premium-positioned chip company. Non-GAAP gross margins have generally stayed in the low 60s. For the third quarter of fiscal 2026, non-GAAP gross margin was 60.9%, compared with 62.6% in the same quarter of fiscal 2025.

What hasn’t arrived—at least not consistently on a GAAP basis—is the clean profitability narrative. Ambarella continues to spend heavily on R&D, and that investment soaks up much of the gross profit. The company did return to non-GAAP profitability: non-GAAP net income in the third quarter of fiscal 2025 was $4.5 million, compared with a non-GAAP net loss of $11.2 million a year earlier. It’s meaningful progress. But the real operating leverage investors want still depends on scale—revenue growing faster than the R&D engine required to stay competitive.

And there’s another growth lane opening up that fits Ambarella’s capabilities almost too neatly: robotics and industrial automation. Warehouse robots, agricultural machines, industrial inspection systems—these products need exactly what Ambarella sells: efficient, on-device vision that can interpret the world in real time. They’re earlier-stage than automotive, but they tend to move on faster cycles, which makes them both strategically attractive and potentially nearer-term.

Through all of this, one stabilizing force has been constant: Fermi Wang. He’s been there from day one, through the GoPro highs, the concentration-risk crash, and the long pivot into AI. And he’s not a “finance CEO” narrating a roadmap from the outside. He’s an engineer with deep credibility—a PhD rooted in video compression, patents tied to MPEG-2, and decades spent building the exact kind of silicon Ambarella now bets its future on. That continuity matters in semiconductors, where credibility is earned over product generations, not press releases.

X. Technology Deep Dive: Why Ambarella's Architecture Matters

If you want to understand why Ambarella still has a seat at the table—despite going up against companies with far bigger budgets—you have to look at what’s actually inside its chips, and why customers keep picking them for cameras, cars, and edge devices that can’t afford to waste power.

At the center of that story is CVflow, Ambarella’s computer vision architecture. The company describes it as “algorithm-first,” and that’s not just marketing. Instead of starting with general-purpose compute blocks and then trying to bend them into shape for video and AI, Ambarella works in the opposite direction: start with the specific workloads—image processing, video encoding, neural-network inference—and design the silicon to run those computations as efficiently as possible.

That design philosophy is what led to the CV3 era. As Fermi Wang put it: “With our new CV3 AI domain controller family, we are now capable of running the full ADAS and AD stack with a single chip, while providing unprecedented performance and power efficiency.” CV3’s headline capability is its on-chip neural vector processor (NVP), built to accelerate neural network inference and scale up to 500 eTOPS, while staying focused on efficiency rather than brute-force compute.

The reason integration matters so much here is the vision pipeline itself. In most computer vision systems, video moves through a relay race: the sensor captures data, an image signal processor (ISP) cleans it up with steps like color correction, noise reduction, and HDR processing, the video is compressed, and only then does AI inference run. Every handoff costs something—latency, power, memory bandwidth, complexity.

Ambarella’s approach is to keep as much of that pipeline tightly coupled on the chip as possible. ISP and AI processing aren’t treated as separate worlds; they share resources and memory bandwidth so data can flow through without constant shuffling. And that’s not a minor detail—if your product is a security camera, a doorbell, a body cam, or an automotive module, those inefficiencies show up immediately as heat, battery drain, or cost.

A big part of that advantage starts at the front end: the ISP. Ambarella emphasizes low-light performance and high dynamic range processing, because the AI can only be as good as the signal it’s fed. If your camera blows out highlights, smears motion, or turns nighttime scenes into noise, your neural network doesn’t get “a hard problem.” It gets bad data. Better imaging translates directly into better perception.

From there, Ambarella leans hard on its most consistent competitive claim: AI performance per watt. The company says its CV3-AD family can deliver up to five times higher power efficiency than other domain controller SoCs, while processing sensor data fast enough to improve environmental perception and overall safety.

That efficiency matters even more in EVs, where compute power is not abstract—it comes out of the same energy budget that determines range. If an automaker can get the perception and planning capability it needs without turning the AI computer into a space heater, that’s a real product advantage.

It also explains why Ambarella’s old life in video compression still matters in its new life in AI. Video encoding is full of highly optimized math—exactly the kind of work where Ambarella learned, over decades, how to squeeze performance out of silicon without blowing the power budget. Many of the core operations in neural networks, especially in classic computer vision models, map well onto that heritage of optimized transforms and motion-related computation. The company’s claim is that the instincts and techniques built for video translated into building efficient AI vision.

This is also where Ambarella’s positioning differs from the most obvious alternatives.

Against GPU-based approaches like NVIDIA’s, the tradeoff is flexibility versus efficiency. GPUs are incredibly versatile and excel at massive parallel throughput. Ambarella’s accelerators are more specialized—less “run anything” flexibility, but dramatically better efficiency when the workload matches the design target. In edge devices and automotive modules, power and thermal limits are non-negotiable constraints, so that tradeoff can favor Ambarella.

Against Mobileye, the contrast is less about raw compute and more about philosophy. Ambarella positions itself as offering the hardware component for ADAS, giving automotive customers the freedom to source other parts—especially software—independently. For automakers that want to differentiate through proprietary software, an “open” model can be appealing. Mobileye’s more vertically integrated approach can reduce integration burden, but it can also limit how much the OEM can customize the full system.

Ambarella, notably, has also been building out software alongside the silicon. The company announced an autonomous driving software stack based primarily on deep learning AI processing, with modular components spanning environmental perception, sensor fusion, and vehicle path planning. The idea is straightforward: if the stack and the SoC are designed together, the software can run optimally on the CVflow AI engines.

The catch is that none of this is a one-and-done advantage. The moat is real, but it has to be constantly rebuilt. AI models evolve, and architectures change. Ambarella’s chips have to keep up with whatever comes next, not just what worked last generation. That’s why the company’s R&D burden stays high—and why, in this market, standing still is the fastest way to fall behind.

XI. Business Model & Unit Economics

Ambarella runs the classic fabless semiconductor playbook: stay out of the factory business, pour your energy into design, and let foundries carry the crushing capital costs of manufacturing. It’s a model built for capital efficiency—and one that works especially well when you have differentiated silicon customers are willing to pay for.

The upside is focus. Ambarella concentrates its money and talent on the part of the stack where it can actually create advantage: architecture, software, and the system-level tradeoffs that make a vision chip great. The physical manufacturing is outsourced to foundries like TSMC and Samsung, which can spread the cost of leading-edge process nodes across many customers. Ambarella’s newer SoCs have used advanced nodes—one family is fabricated on Samsung’s 5nm process and includes up to 16 Arm Cortex-A78AE CPU cores.

When things are going well, the flywheel is powerful: design a chip, tape it out, ramp it at the foundry, sell into camera OEMs, and sustain gross margins north of 60%. But fabless also comes with real dependencies. If foundry capacity tightens, product ramps can slip. Moving from one process generation to the next—7nm to 5nm to 3nm—requires deep collaboration with manufacturing partners. And margins are never guaranteed; if competitors can deliver “good enough” performance from similar foundry technology, pricing pressure shows up quickly.

Unit economics tell you why the company has been so intent on shifting where it plays. In consumer cameras, chips might sell in the $10–30 range. Automotive domain controllers can sell for $100 or more. So, yes, moving from consumer gadgets to automotive and higher-end edge AI carries the promise of meaningfully higher selling prices. The catch is that automotive makes you earn it with long design cycles and slow ramps.

Historically, Ambarella’s own average selling prices have ranged from around $10 up to roughly $50 for higher-end CV2 chips. The CV3 family is more capable and is expected to command higher prices, but the company hasn’t disclosed specific CV3 ASPs.

Then there’s the reality that defines Ambarella’s income statement: R&D. Building advanced SoCs isn’t a “set it and forget it” business. It’s continuous spending on engineering teams, EDA tools, silicon prototypes, and software. In the most recent quarter cited here, R&D expenses rose 48% year over year, SG&A climbed 21%, and total operating expenses jumped 38%, reaching 62% of revenue.

That intensity is not a management choice so much as the price of staying relevant. But it does explain why profitability is a struggle: until revenue scales, R&D absorbs most of the gross profit, leaving limited operating leverage.

The good news is that Ambarella is no longer living under the GoPro-style concentration risk. By the end of fiscal 2023, the company had cumulatively shipped more than 13 million computer vision processors to more than 325 unique customers, with mass production shipments across enterprise, public infrastructure, smart home, and both passenger and commercial vehicle markets.

That breadth matters. It’s not just a nice statistic—it’s resilience. With hundreds of customers, Ambarella is far less likely to have its future dictated by one product cycle, one OEM, or one consumer trend.

On capital allocation, the priorities have been consistent: keep funding the R&D engine and buy strategic capabilities when it accelerates the roadmap. VisLab ($30 million) brought autonomous-driving computer vision expertise. Oculii ($307.5 million) expanded the story into AI-enhanced radar perception. Ambarella has also maintained substantial cash on the balance sheet, keeping flexibility for whatever the next opportunity—or shock—might be.

XII. Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

This is a knife fight, not a cozy niche.

Ambarella is up against heavyweight rivals like NVIDIA, Mobileye (Intel), Qualcomm, and Chinese players like Horizon Robotics. Each comes with a built-in advantage. NVIDIA’s dominance in AI training spills over into edge inference—customers want a familiar ecosystem. Qualcomm brings its smartphone-era playbook into cars, with offerings that span smart cockpits, ADAS, and V2X. Mobileye has years of ADAS deployments already on the road, which matters enormously when automakers are allergic to risk. And Horizon benefits from access to China’s domestic market and the speed of local adoption.

The result is relentless pressure: constant innovation just to keep your seat at the table, and a ceiling on pricing power because customers always have another credible option.

Supplier Power: MODERATE

Like most fabless chip companies, Ambarella lives and dies by its foundry relationships—primarily TSMC and Samsung. When capacity gets tight, foundries have real leverage on pricing, priority, and timelines.

That said, Ambarella does have some flexibility. It isn’t structurally locked into one manufacturer forever, and it can shift different product generations across foundries. It’s an interdependent relationship: foundries need high-quality design customers to keep advanced nodes busy, and designers need access to those nodes to stay competitive.

Buyer Power: MODERATE-HIGH

In automotive, the buyers are huge and sophisticated. OEMs and Tier 1 suppliers negotiate hard, compare suppliers aggressively, and have long program timelines that give them plenty of time to pressure pricing.

But once a chip is designed into a vehicle platform, the power balance shifts. Switching isn’t like swapping out a part in a consumer device—it means requalification, recertification, and revalidation. That process is expensive, slow, and risky, which creates meaningful lock-in after a design win.

Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE

There are real substitutes—and some of them are already here.

Tesla has shown that an OEM can build in-house chips. In less latency-sensitive use cases, cloud processing can sometimes substitute for edge inference, although privacy and bandwidth costs put a hard limit on how far that goes. And general-purpose AI silicon from large platform companies can encroach on specialized edge chips if it’s “good enough” and easy to integrate.

Still, for applications that require real-time response and low power—especially inside a car or a battery-powered device—specialized edge architectures remain compelling. That’s the lane Ambarella is betting will keep expanding.

Barriers to Entry: HIGH

Building a competitive AI vision SoC is not something you spin up with a small team and a few million dollars. You need years of accumulated IP, deep engineering experience, automotive-grade reliability and functional safety know-how, and the capital to survive multiple chip generations before the payoff.

Ambarella’s foundation—video compression and image processing expertise, plus a significant patent footprint—gives it a real base. And its early, sustained investment in dedicated AI hardware through CVflow is an additional edge, particularly because it’s tuned for the power and latency constraints of edge deployment.

But “high barriers” doesn’t mean “no entrants.” AI is one of the most aggressively funded arenas in tech, and new well-capitalized competitors keep showing up. The wall is tall—but it’s climbable for determined challengers.

XIII. Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: LIMITED

Ambarella doesn’t get to win the way the biggest chip companies win. In memory or commodity processors, scale can be destiny—more volume means lower unit costs, more bargaining power with foundries, and more dollars to spread across R&D. Ambarella’s core markets are valuable, but they’re not built on that kind of mass volume. Its advantage has to come from what it designs, not how many units it ships.

Network Effects: WEAK

There’s no true network effect here. One customer adopting CVflow doesn’t automatically make the product better for the next customer, the way it would with a platform or a marketplace.

What Ambarella does get, over time, is a softer version: an ecosystem effect. As more developers learn the toolchain, more reference designs get reused, and more software stacks get built around its SDKs, it becomes a little easier to adopt—and a little harder to rip out.

Counter-Positioning: MODERATE

Ambarella has spent years staking out a very specific hill: edge-first, power-efficiency-first computer vision.

That’s a real counter-position to competitors that optimize for brute-force performance and broad programmability. When power is the constraint—battery cameras, thermally limited automotive modules, EVs—Ambarella’s bet looks smart. In applications where power isn’t the bottleneck, that same focus can be less compelling.

Switching Costs: STRONG in automotive, MODERATE elsewhere

In automotive, switching costs are the closest thing to a force field Ambarella has. Once a Tier 1 or OEM builds a program around a chip, changing it isn’t a “swap vendors next quarter” decision. It’s years of redesign, revalidation, and recertification. That’s why a design win matters so much—after you’re in, it’s hard to dislodge you.

Outside automotive, switching costs are lower but still real. Security camera makers and other edge customers often invest heavily in software built around Ambarella’s SDKs and pipelines. That investment creates friction, even if it doesn’t create the same multi-year lock-in you see in a vehicle platform.

Branding: MODERATE

Ambarella has a strong reputation where it counts—among OEMs, engineers, and the B2B semiconductor world. But it’s essentially invisible to consumers. There’s no “Intel Inside” effect pulling demand through the channel.

Its brand is more practical: a signal of credible performance, reliable supply, and a company that will still support the part years later—attributes that matter a lot in security and automotive procurement.

Cornered Resource: STRONG

Ambarella’s deepest asset is what it knows how to do—and how long it’s been doing it.

Columbia University became the only academic institution among nine initial patent holders deemed essential to the MPEG-2 video compression standard, rooted in research tied to Fermi Wang’s early work. That video compression DNA shaped Ambarella from the start. Over time, it compounded: VisLab added decades of autonomous-driving computer vision heritage, and Oculii added adaptive AI radar algorithms.

This isn’t just IP on paper. It’s institutional know-how—accumulated over decades—that’s brutally difficult to reproduce quickly, even with money.

Process Power: MODERATE-STRONG

CVflow didn’t appear fully formed. It’s the result of iterative refinement across generations—architecture decisions, tooling, customer feedback loops, and the hard-earned lessons that come from real deployments.

That kind of process advantage tends to strengthen with each cycle. Every new chip generation and every new customer program feeds the next one, making Ambarella better at building the exact kind of vision silicon it sells.

Power Assessment Summary: Ambarella’s primary competitive powers are Cornered Resource (accumulated video compression and computer vision expertise) and Switching Costs (especially in automotive). Process Power is strengthening as CVflow matures. What it notably lacks is Scale Economies, which leaves it exposed in a market where the biggest competitors can spend more, subsidize ecosystems, and endure longer fights.

XIV. Bull vs. Bear Case

Bull Case: The Automotive Transformation Delivers

The optimistic case for Ambarella is pretty clean: the long, slow automotive pipeline finally turns into real production revenue.

Partnerships with Continental and Bosch matter here because they’re not just logo collecting. They’re a validation that CV3 can clear the bar in a market where the default answer is often NVIDIA, Qualcomm, or Mobileye. If those design-ins roll into start-of-production on schedule, automotive stops being a promise and starts being a revenue engine. And because Chinese OEMs tend to move faster than Western counterparts, CV3 programs there could begin contributing in the 2026–2027 window.

If that happens, the mix shift becomes the story. Automotive could grow into a large chunk of total revenue over the 2027–2028 timeframe, changing both the narrative and the unit economics.

At the same time, the broader edge AI wave keeps building. Security cameras, robotics, and industrial devices increasingly want intelligence on-device, not in the cloud—driven by latency, bandwidth cost, and privacy. EVs add another tailwind: power efficiency isn’t a nice feature, it’s part of the product, and Ambarella’s architecture is explicitly optimized for that constraint. New workloads—from warehouse automation to more advanced robotics—create more places where “vision plus efficient inference” is the whole ballgame.

Ambarella also has an upside lever it largely didn’t have in the GoPro era: software.

"This process is ongoing, and we believe the product will come out in 2027," he added. "So, that's when we can start collecting our first software revenue from this collaboration."

If software licensing or subscription-style revenue takes hold—autonomous driving stacks, radar perception algorithms, developer tooling—the business starts to look less like “a chip company with cyclical ramps” and more like hardware-plus-software with recurring revenue. And that kind of model typically earns higher valuation multiples.

Finally, there’s the strategic optionality. If CV3 production ramps show real traction, Ambarella becomes an interesting acquisition target: an edge AI vision stack that could slot into a larger automotive supplier, a camera ecosystem player, or even a hyperscaler looking to push intelligence down to devices.

Bear Case: The Giants Crush the Underdog

The pessimistic case starts with a brutal truth: Ambarella is fighting companies that can simply spend more.

NVIDIA, Qualcomm, and Mobileye can invest multiples of Ambarella’s R&D budget, and in semiconductors that matters. Ecosystems matter too. NVIDIA’s gravity in AI training and developer tooling can spill into edge inference, not necessarily because it’s always the best silicon for the job, but because it’s the most familiar choice.

Then there’s the recurring fear that has haunted Ambarella for years: automotive is always “next year.”

Design wins sound great, but revenue has a way of sliding rightward. If programs slip, if production volumes come in lower than hoped, or if Tier 1s and OEMs spread volume across multiple suppliers, the bull case loses its core fuel.

And even if automotive does arrive, Ambarella may remain a smaller player in a market that increasingly rewards scale. As larger competitors crowd into the same ADAS and domain controller space, pricing pressure and ecosystem lock-in can blunt the advantage of a more efficient architecture.

China adds another layer of risk. Domestic competitors like Horizon Robotics can offer “good enough” capability at lower prices, and geopolitical tension can turn exposure into a liability just as quickly as it turns it into growth.

Vertical integration is the other structural threat. Tesla proved an OEM can build its own chips if it cares enough. If more automakers follow that path, the total addressable market for merchant silicon shrinks. And if Tesla’s camera-only philosophy becomes the prevailing paradigm, it could reduce the perceived value of multi-sensor fusion—one of the areas where Ambarella has been investing heavily.

Finally, the old consumer engines aren’t coming back to save anyone. Smartphones won the camera wars. Action cameras are a niche. Consumer drones consolidated around DJI. If automotive doesn’t deliver meaningful scale, Ambarella risks being stuck as a subscale specialist in markets where the biggest players keep getting bigger.

Key Metrics to Monitor

1. Automotive Revenue as Percentage of Total: The single most important KPI. The target is 30%+ by fiscal 2027. It’s currently estimated around 25%. Progress toward that level would be the clearest validation that the pivot is working.

2. Design Win Announcements and Production Timelines: Design wins only matter if they turn into vehicles rolling off the line. Watch for timelines holding, slipping, or getting quietly revised downward.

3. Gross Margin Trajectory: A signal of both mix shift and pricing power. Automotive should be margin-accretive if Ambarella’s differentiation holds. If margins compress, it’s a warning that competition is biting.

XV. Playbook: Lessons for Founders & Investors

Ambarella’s story isn’t just “a chip company that lost GoPro.” It’s a case study in what it takes to survive when your best tailwind turns into your biggest threat—and what separates a pivot that works from one that’s just a slide deck.

The Ambarella story offers several lessons that transcend its specific circumstances:

The Pivot Imperative: When your largest customer becomes your biggest risk, move while you still have oxygen. Ambarella started investing in computer vision and acquired VisLab before GoPro’s decline fully hit. That early commitment mattered. When the consumer electronics cycle finally snapped, the company wasn’t starting from zero—it already had a foundation to build on.

Deep Tech Moats Matter in Semiconductors: In chips, “moat” isn’t branding. It’s accumulated learning. Wang’s video compression patents, the institutional knowledge from C-Cube, Afara, and Ambarella, and VisLab’s autonomous-driving expertise added up to something competitors couldn’t copy quickly, even with money. In semiconductors, domain expertise compounds—and it compounds over decades.

Automotive Requires Extreme Patience: Cars don’t run on consumer timelines. With multi-year design cycles and qualification requirements, automotive demands a different kind of investor temperament than action cameras ever did. If you’re building for this market, you have to communicate timelines realistically—and be ready for long stretches where the work is real, the wins are real, and the revenue is still waiting at the end of the runway.

Power Efficiency as Strategy: Ambarella didn’t try to out-muscle NVIDIA at raw performance. It optimized for a different scoreboard: performance per watt. In edge devices and EVs, that’s not a nice-to-have metric—it’s the constraint that determines whether the product works at all. Sometimes “good enough, but efficient” creates the market, while “best on paper” gets stuck in the lab.

The Fabless Model's Tradeoffs: The fabless model buys you capital efficiency, but it also means you don’t control manufacturing. In shortages, and during major process transitions, foundry dependency becomes a real vulnerability—one that vertically integrated players can sometimes sidestep. Fabless works best when your design is differentiated enough to sustain pricing power and absorb the inevitable margin and supply-chain shocks.

Founder-Led Advantage: Fermi Wang’s long tenure matters because Ambarella’s journey required multiple reinventions—broadcast ambitions, then consumer electronics scale, then edge AI, then automotive. A technical founder with deep product intuition can make long-horizon bets that often look irrational in the quarter-to-quarter view. In this story, that continuity wasn’t a feel-good detail. It was part of the strategy.

XVI. Epilogue & Future Outlook

As 2025 drew to a close, Ambarella sat in a familiar place: between proof and payoff.

The consumer electronics chapter was, for all practical purposes, done. The edge AI vision chapter was real and scaling. But the automotive chapter—the one that could dwarf everything that came before—was still mostly written in program plans and SOP dates rather than in revenue.

The near-term signals, though, started to point in the right direction. Management raised full-year revenue guidance to about $390 million at the midpoint for fiscal 2026, implying roughly mid-to-high 30% growth year over year and projecting a record fiscal year. In a business that spent years being defined by what went wrong, simply hitting new highs again matters. It doesn’t “solve” automotive, but it does show the core edge AI business is alive and strengthening.

Then there’s the next potential engine: robotics.

If automotive is a long runway, robotics could be the shorter flight. Humanoid projects, warehouse automation systems, agricultural robots—these machines all have the same basic problem: they need to see, interpret, and react in real time, without burning through power or relying on a network connection that might not exist. That is Ambarella’s native terrain. And unlike automotive, many robotics programs iterate on faster cycles, which could make it a meaningful growth vector sooner if adoption breaks the right way.

Generative AI adds another layer. The next wave of vision isn’t just “detect an object,” it’s “understand a scene,” including responding to natural-language queries about what the camera is seeing. Vision-language models on edge hardware are still early, but they’re moving from science project to product possibility. Ambarella has positioned its roadmap to support these emerging architectures, which could expand the definition of what an “AI camera” even is.

All of that brings up the strategic question that never really goes away for a subscale, deeply specialized semiconductor company: does Ambarella stay independent, or does it become part of something bigger?

On paper, the acquirer list is obvious. Automotive suppliers looking to own more of the silicon stack. Cloud companies trying to push intelligence down to devices. Camera and security companies that want AI differentiation built into the silicon rather than bolted on later. Any deal would come down to timing and price—but the underlying point is that Ambarella’s technology sits in a part of the market that larger players increasingly care about.

So what would have to happen for Ambarella to become a $10B+ company? Some combination of the following: automotive scaling into hundreds of millions in annual revenue as programs finally hit production, robotics turning into a real line item rather than a narrative, and software licensing creating recurring revenue streams alongside chip sales—while maintaining roughly 60%+ gross margins at a much larger scale. None of those outcomes are guaranteed. But they’re at least coherent, and they match the direction of the industry.

And what could derail it? The list is just as clear: automotive timelines slipping or volumes coming in light, margin compression as competitors crowd the space, losing key customers, or geopolitical disruption that hits demand—especially anywhere China exposure is meaningful. This is still semiconductors. The upside can be enormous, but the failure modes are very real.

Still, zoom out and the arc is hard to ignore. Ambarella went from being GoPro’s silicon sidekick to an edge AI company trying to earn a place in autonomous driving—one of the largest technology bets of the coming decades. Whether that reinvention ultimately rewards shareholders in proportion to the risk is the central open question.

Fermi Wang’s personal trajectory mirrors the company’s: from a Columbia grad student working on video compression to a CEO building chips that help machines understand the world. Across all the pivots, the through-line hasn’t been a single product. It’s been an instinct for where video is going next—and a willingness to rebuild the company around that answer.

The story, in other words, isn’t finished. The biggest chapters—autonomous driving, robotics, and the next generation of edge AI—are still being written. Ambarella offers real exposure to those shifts, but it demands the kind of patience these markets impose. In a business as unforgiving as semiconductors, survival is never the end of the story. It’s just the right to keep playing.

What Ambarella does with that second chance will determine whether it becomes a footnote from the GoPro era—or a pillar of the edge AI era that followed.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music